Abstract

Repeat associated non-AUG (RAN) translation of CGG repeats in the 5′UTR of FMR1 produces toxic proteins that contribute to fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) pathogenesis. The most abundant RAN product, FMRpolyG, initiates predominantly at an ACG upstream of the repeat. Accurate FMRpolyG measurements in FXTAS patients are lacking. We used data-dependent acquisition and parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) mass spectrometry coupled with stable isotope labeled standard peptides to identify signature FMRpolyG fragments in patient samples. Following immunoprecipitation, PRM detected FMRpolyG signature peptides in transfected cells, and FXTAS tissues and cells, but not in controls. We identified two amino-terminal peptides: an ACG-initiated Ac-MEAPLPGGVR and a GUG-initiated Ac-TEAPLPGGVR, as well as evidence for RAN translation initiation within the CGG repeat itself in two reading frames. Initiation at all sites increased following cellular stress, decreased following eIF1 overexpression and was eIF4A and M7G cap-dependent. These data demonstrate that FMRpolyG is quantifiable in human samples and FMR1 RAN translation initiates via similar mechanisms for near-cognate codons and within the repeat through processes dependent on available initiation factors and cellular environment.

Introduction

Fragile X associated tremor ataxia syndrome (FXTAS) is an inherited late-onset neurodegenerative disorder caused by a CGG repeat expansion within the 5′UTR of FMR1. One of the pathological hallmarks of this disease is the presence of ubiquitinated neuronal inclusions in patient brain tissue (1,2). These inclusions are thought to occur as a result of an aberrant form of translation, termed repeat associated non-AUG (RAN) translation (3–5). RAN translation on FMR1 transcripts is enhanced by CGG repeat expansions that form strong secondary structures in the RNA (6–9). These repeats are thought to stall scanning ribosomes, allowing initiation just upstream of, or within the repeat itself in the absence of an AUG start codon (6). RAN translation at CGG repeats (CGG RAN) can occur in all three reading frames, producing three distinct toxic homopolymeric peptides, the most abundant of which is a polyglycine product, FMRpolyG (4,6,10,11). Overexpression of CGG repeats that support FMRpolyG expression, as well as overexpression of FMRpolyG absent a CGG repeat, promotes neurodegeneration in various model systems (4,11–16) and FMRpolyG is detected in human FXTAS brain tissue where it localizes to ubiquitin and P62+ inclusions (17–19). FMRpolyG has recently been detected via mass spectrometry (MS) in transfected cells as well as in patient tissue (16,20); however, reliable detection of CGG RAN peptides and the ability to accurately quantify them is lacking.

In reporter assays, RAN translation of FMRpolyG predominantly initiates at two near-cognate codons: an ACG, located 36 nts upstream of the repeat and a GUG located 12 nts from the repeat (6,16). Exactly how this initiation occurs and what factors are required is not fully understood. Recently, our lab and others uncovered a role for the integrated stress response (ISR) in upregulating RAN translation at CGG repeats and at the C9orf72 ALS-causing G4C2 repeat (10,21–23). Under normal conditions, eIF2 binds GTP and Met-tRNAiMet to form the ternary complex (TC) that then binds the 40S ribosome and a host of other translation initiation factors that facilitate cap binding and scanning, to form the 43S preinitiation complex (PIC). The PIC then scans along the mRNA, 5′-3′, until it encounters the AUG start codon and initiation occurs (12,24–28). However, when any one of four ISR kinases (PERK, GCN2, HRI and PKR) is activated, canonical translation initiation factor eIF2α is phosphorylated, thereby inhibiting eIF2β from exchanging GDP for GTP, and preventing a new round of TC assembly. This inhibits translation by reducing the rate at which new TCs are loaded onto 40S ribosomes to promote initiation (26,28).

Some genes remain translationally active after ISR activation. This often occurs through re-initiation events triggered by upstream open reading frames, initiation at codons other than AUG, or through use of internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) (10,29–35). The likelihood that initiation will occur at a near-cognate codon during cellular stress is dependent on a number of factors including efficiency of TC recruitment to the 40S docked on an initiation codon, strength of that codon and its surrounding Kozak sequence and availability of specific initiation factors (36–39). In particular, the eIF2 alternative factor, eIF2A, can facilitate near-cognate codon and IRES mediated initiation and, unlike eIF2, is GTP-independent and upregulated during cellular stress (22,35,40–43). Consistent with this, eIF2A has also been implicated in RAN translation of G4C2 repeats that initiate at a CUG codon (22,44).

While eIF2A is capable of promoting non-AUG initiation, the canonical initiation factor eIF1 has an opposing role of ensuring AUG start-codon fidelity. eIF1 does this by keeping the 43S PIC in an open conformation to allow for TC binding and scanning and by impeding eIF5 GTPase activity, which slows down the conversion of eIF2-GTP to eIF2-GDP-Pi and inhibits Pi release. When the PIC recognizes an AUG initiation codon, eIF1 dissociates from the ribosome and allows eIF5 activation and large ribosomal subunit recruitment (45–48). In vitro experiments have shown that in the absence of eIF1, ribosomes readily initiate at near-cognate codons, and when eIF1 is overexpressed, use of near-cognate codons is inhibited, specifically when the near-cognate codon differs at position 1 (38,49–51). eIF1 overexpression was recently shown to dramatically inhibit CGG RAN translation (11). How eI2A and eIF1 might interact to dictate start codon selection and whether or how they contribute to CGG RAN remain unknown.

Here, using parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) MS coupled with stable isotope-labeled standard peptides (SIS), we both detected and quantified FMRpolyG peptides in overexpression systems and in FXTAS patient cells and tissue. This sensitive technique allowed us to identify an additional initiation codon, GUG, immediately 5′ of the ACG, that is preferentially used in response to cellular stress. Initiation at this codon is selectively inhibited in the absence of eIF2 alternative factor, eIF2A, and during overexpression of canonical translation initiation factor, eIF1. We also found evidence for RAN initiation within the repeat itself and show that it similarly responds to cellular stress and eIF1 availability, despite the lack of near-cognate codons within the repeat. Importantly, FMRpolyG derived from initiation at near-cognate codons above the repeat and from initiation within the repeat itself are all dependent on the scanning helicase eIF4A and all are largely dependent on the presence of an M7G cap on the mRNA. Taken together, PRM-SIS MS is a promising method for quantifying low abundant RAN peptides with potential future applications in FXTAS biomarker development. Using this tool, we provide evidence for mechanistic convergence of near-cognate and non-cognate repeat associated translational initiation in a neurodegenerative disease.

Results

Development of PRM-SIS for FMRpolyG quantification

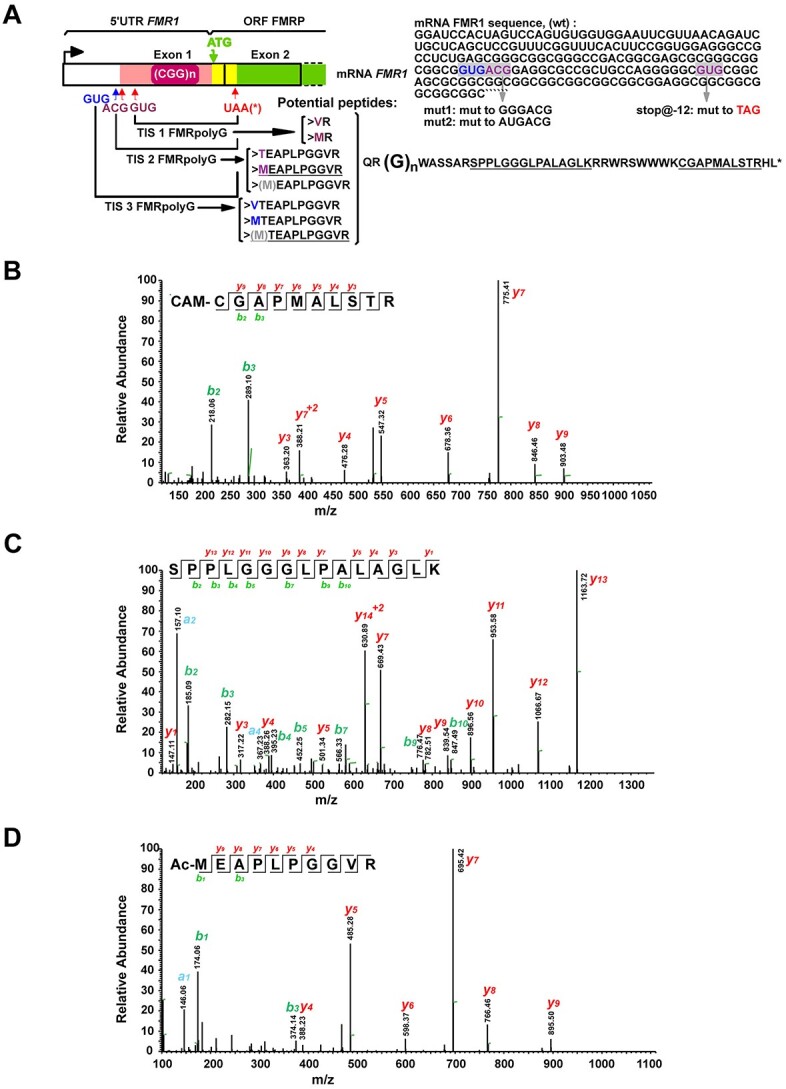

RAN translation of FMRpolyG primarily initiates at two near-cognate codons, ACG and GUG, located in the FMR1 5′ UTR, upstream of the CGG repeat (6), however, while initiation at the ACG with a methionine has been previously reported in transfected samples and recently found at extremely low levels endogenously, whether other species exist, and whether they can be detected at quantifiable levels has not been determined (16,20). In order to detect and quantify endogenous FMRpolyG, we first identified potential FMRpolyG signature peptides. We predicted four different FMRpolyG sequences based on known initiation start sites for FMRpolyG: two longer isoforms beginning at ACG and initiating with either a methionine or a threonine, and two shorter isoforms beginning at GUG and initiating with either a methionine or a valine (Fig. 1A). From these sequences, we identified four potential FMRpolyG signature peptides (two N-terminal and two C-terminal) to use for quantification (Fig. 1A underlined sequences). We then applied data-dependent acquisition (DDA) MS to identify these signature peptides in an FMRpolyG overexpression system. After comparing with the latest SwissProt human protein database (42 054 sequences) (https://www.uniprot.org/statistics/Swiss-Prot), we found three of the four signature FMRpolyG peptides produced in HEK293Ts expressing exogenous FMRpolyG: the two C-terminal fragments—a carbamidomethyl modified peptide, CAM-CGAPMALSTR, and an unmodified peptide, SPPLGGGLPALAGLK—and an acetyl-modified methionine-initiated N-terminal fragment, Ac-MEAPLPGGVR (Fig. 1B–D). This N-terminal fragment and the SPPLGGGLPALAGLK fragment have previously been identified using similar methods (16,20).

Figure 1.

Predicted peptide sequences and monitored signature peptides for RAN translated product, FMRpolyG. (A) Schematic of FMRpolyG peptides produced via alternative translation initiation on FMR1. (top) FMR1 schematic showing location of the FMRpolyG uORF (pink), FMRP ORF (green) and sequence corresponding to overlap of these two ORFs (yellow). The mRNA sequence 5′ to the CGG repeat is shown on the right. Three potential FMRpolyG translation initiation sites (TIS) on FMR1 are indicated: two previously identified (purple) and one novel initiation site (blue). Grey highlights indicate position of each codon relative to the CGG repeat. Grey arrows point to specific mutant reporters used later in this study. (bottom) Predicted trypsin-digested signature peptides for FMRpolyG. Underlined sequences are those identified in this study. The grey M in brackets indicates a potential product of iMet excision. (B–D) Liquid chromatography MS (LC–MS/MS) spectra of FMRpolyG signature peptides, CAM-CGAPMALSTRHL (B), SPPLGGGLPALAGLK (C) and Ac-MEAPLPGGVR (D) from HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag. Observed b- and y-ions are indicated.

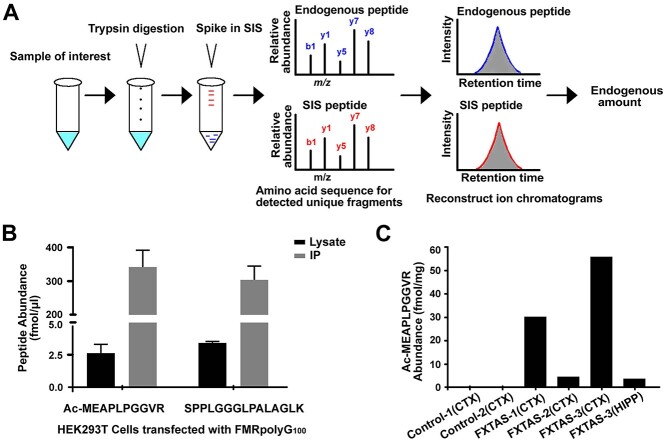

The carbamidomethyl modification on an NH2-terminal cysteine can cause the peptide to spontaneously undergo cyclization during MS sample preparation in a pH- and time-dependent manner, making CAM-CGAPMALSTR a poor peptide for quantification (52). Thus, we chose Ac-MEAPLPGGVR and SPPLGGGLPALAGLK as signature peptides for FMRpolyG quantification by PRM combined with stable isotope-labeled signature peptides (PRM-SIS). PRM-SIS is one of the most accurate approaches for directly quantifying the absolute abundance of known target proteins in a complex mixture (53). By monitoring the response and determining the area under the curve of specific fragment ions of both endogenous and SIS peptides (spiked in at known concentrations during sample preparation), we can calculate the absolute abundance of our protein in a given sample (Fig. 2A). Light and heavy peptides for Ac-MEAPLPGGVR and SPPLGGGLPALAGLK were synthesized and used to determine the limit of detection and limit of quantification in the background of fragile X syndrome patient derived fibroblasts which do not produce any FMR1 mRNA, as well as in control CSF (Supplementary Material, Table S1 and Supplementary Material, Fig. S1). Both conditions had values in the sub-nanomolar range (data not shown).

Figure 2.

PRM-based quantification of FMRpolyG. Schematic for PRM-SIS quantification. Samples were digested with trypsin and then spiked with known concentrations of a signature SIS peptide. The amino acid sequence for our signature peptide of interest was detected by MS, and the endogenous peptide concentration was quantified relative to the SIS peptide. (B) Quantification of FMRpolyG signature peptides, Ac-MEAPLPGGVR and SPPLGGGLPALAGLK, in HEK293T cell lysates transfected with untagged FMRpolyG100 for 24 h and either processed directly or following IP with NTF1 antibody. Bars represent mean ± SD. N = 2. (C) Quantification of the absolute abundance of endogenous FMRpolyG peptide Ac-MEAPLPGGVR from human FXTAS and control brains by PRM-SIS.

Optimizing FMRpolyG detection in transfected HEK293Ts by PRM-SIS

We next quantified FMRpolyG abundance in HEK293Ts transfected with or without untagged FMRpolyG100. Despite being able to detect FMRpolyG in overexpression systems quite readily by western blot (WB) (4,6,10), measurement of the two signature peptides Ac-MEAPLPGGVR and SPPLGGGLPALAGLK in cell lysate by PRM-SIS were near the limit of quantification even with overexpression (Fig. 2B and Supplementary Material, Table S1). This discrepancy was not due to FMRpolyG aggregation, as FMRpolyG was primarily in the soluble fraction following ultracentrifugation, with only a small fraction found in the urea soluble pellet (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2A and B). Furthermore, FMRpolyG was efficiently digested by trypsin (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2C), suggesting that the low quantification observed was not due to insufficient digestion of FMRpolyG but due to low abundance. Consistent with these observations, digesting lysates with the pentaglycine endopeptidase, lysostaphin (LS), which cleaves the polyglycine stretch in FMRpolyG (4), had no effect on the levels of Ac-MEAPLPGGVR, and only modestly enhanced detection of SPPLGGGLPALAGLK (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2D and E). To overcome this low level of detection, we enriched for FMRpolyG through immunoprecipitation (IP) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2F). Following IP of FMRpolyG using a specific FMRpolyG N-terminal antibody (NTF1) (19), FMRpolyG was detected >100-fold more than in whole cell lysate (Fig. 2B). This fold increase correlated with amounts of starting material (50 μg/cell lysate versus 4 mg/IP) and was maintained when normalized to spiked-in SIS Ac-MEAPLPGGVR and SPPLGGGLPALAGLK.

Detection and quantification of endogenous FMRpolyG in FXTAS patient derived samples

We next sought to detect FMRpolyG in IPed human derived samples using PRM-SIS. Only one of the monitored FMRpolyG peptides, Ac-MEAPLPGGVR, was detectable and quantifiable in a CGG premutation iPSC line (FX 11-9 U) and an un-methylated full mutation line (55) but not in a control iPSC line with 23 repeats (2E) (Table 1 and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2G). In contrast, FMRpolyG was not detected by PRM-SIS in patient derived CSF or from lysates of patient derived fibroblasts or lymphoblasts (Table 1). As FMR1 is highly expressed in the brain and most FMRpolyG pathology reported to date is seen in neurons and glia (1,4,54,56), we reasoned that FMRpolyG might be more abundant in human FXTAS derived autopsy samples. Using PRM-SIS, we detected Ac-MEAPLPGGVR in FXTAS cortex samples from 3 separate cases and 1 FXTAS hippocampus sample, but not in 2 age-matched control cortices (Fig. 2C and Supplementary Material, Fig. S2H). The absolute abundance for Ac-MEAPLPGGVR ranged widely from 4.5 to 55.99 fmol/mg and did not correlate with repeat length (Fig. 2C, and Table 1). We observed more FMRpolyG in cortex versus hippocampus for FXTAS-3, which may reflect the increased diffuse staining (rather than accumulation in ubiquitinated inclusions) observed for cortical FMRpolyG by immunohistochemical techniques (19). Altogether, these data confirm that FMRpolyG is detectable and quantifiable in human samples and iPSC derived cells with expanded repeats. However, the overall abundance of FMRpolyG as measured by PRM-SIS is low.

Table 1.

Characteristics and quantification from all human derived samples

| Sample | Diagnosis | Age (y) |

Sex | CGG repeats | Source | Sample amount used (total protein/volume) | Quantification of Ac-MEAPLPGGVR by PRM-SIS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2E | Control | - | - | 23 | iPSC line | 1.5 mg | ND |

| FX 11-9 U | FXTAS | 7 | M | 114 | iPSC line | 1.5 mg | 4.7 fmol |

| TC43 | Unmethylated Full Mutation | - | - | 272 | NPC | 7.5 mg | 20.0 fmol |

| Control-1 | Control | 81 | M | - | Cortex | 5.2 mg | ND |

| Control-2 | Control | 72 | M | - | Cortex | 5.4 mg | ND |

| FXTAS-1 | FXTAS | 74 | M | 102 | Cortex | 5.0 mg | 151.21 fmol |

| FXTAS-2 | FXTAS | 78 | M | 90 | Cortex | 3.0 mg | 13.53 fmol |

| FXTAS-3 | FXTAS | 80 | M | 90 | Cortex | 3.0 mg | 167.60 fmol |

| Hippocampus | 4.1 mg | 14.93 fmol | |||||

| Lym-1 | FXTAS | 60 | M | 114 | Lymphocytes | 3.5 mg | ND |

| Fibro-1 | FXTAS | 60 | M | 97 | Fibroblasts | 3.5 mg | ND |

| CSF1 | Control | - | - | - | CSF | 5 mL | ND |

| CSF2 | FXTAS | - | - | - | CSF | 5 ml | ND |

| CSF3 | FXTAS | - | - | - | CSF | 5 ml | ND |

ND: not detectable.

Discovery of an additional RAN initiation codon

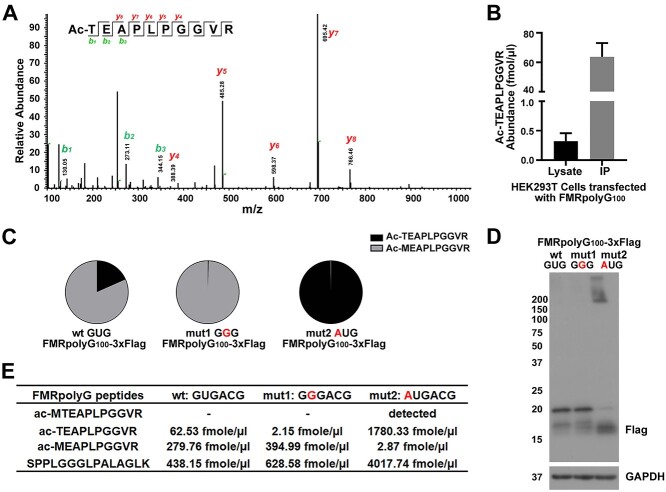

DDA MS only detected one N-terminal fragment, Ac-MEAPLPGGVR. However, using the more sensitive PRM method, we identified a second N-terminal peptide—Ac-TEAPLPGGVR (Fig. 3A). To measure this peptide, we synthesized light and heavy SIS for Ac-TEAPLPGGVR and determined the LOD (0.9766 fmol/μl) and LOQ (2.9298 fmol/μl) in fragile-X syndrome fibroblasts to be in the sub-nanomolar range similar to that of Ac-MEAPLPGGVR (Supplementary Material, Table S1 and Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A and B). When we quantified Ac-TEAPLPGGVR from HEK293Ts transfected with untagged FMRpolyG, we found that the abundance for the new Ac-TEAPLPGGVR fragment of FMRpolyG was lower than the Ac-MEAPLPGGVR fragment (Fig. 3B, see Fig. 2B) but still made up a significant proportion (15.69%) of detected FMRpolyG initiation peptides. We saw a similar pattern in HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100-3xFlag, using lysates directly (17.42%) and following IP (18.37%) (Fig. 3C, left).

Figure 3.

CGG RAN translation initiation can occur at a 5′ GUG codon. (A) Representative LC–MS/MS chromatogram of FMRpolyG peptide, Ac-TEAPLPGGVR from NTF1 immunoprecipitated HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100. (B) Quantification of Ac-TEAPLPGGVR absolute abundance in HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100. Bars represent mean ± SD. N = 2. (C) The proportion of two different initiation fragments quantified via PRM-SIS from IPed lysates of HEK293Ts transfected with the indicated reporters. (D) WB of FMRpolyG from HEK293Ts transfected with the indicated reporters. GAPDH serves as a loading control. (E) Quantification of signature peptide absolute abundance in IPed lysates of HEK293Ts transfected with the indicated reporters. ‘Detected’ indicates observed, but not quantified (See Supplementary Material, Fig. S3C).

As Ac-TEAPLPGGVR is acetylated (a common posttranslational modification of N-terminal amino acids) and the codon 5′ to the ACG is a GUG, coding for valine, we can conclude that this is an N-terminal initiation fragment and not a trypsin cleavage product of a spurious upstream initiation event (57,59). It is possible that Ac-TEAPLPGGVR is derived from the same near-cognate codon ACG, which is supported by a similar observation in another gene, CLK2 (60). However, Ac-TEAPLPGGVR could also arise from Met initiation at the GUG followed by N-terminal Met (iMet) excision, an event that is particularly common when Thr is the second amino acid (61–63). To determine if Ac-TEAPLPGGVR was due to initiation at the 5′ GUG with Met-tRNAiMet followed by iMet excision, we designed two new reporters. In the first, we mutated the GUG upstream of the ACG to GGG. Importantly, this mutation did not alter the strength of the Kozak sequence for the ACG codon. In the second, we mutated the GUG upstream of the ACG to an AUG (see Fig. 1A, right). We hypothesized that if Ac-TEAPLPGGVR was derived from the ACG, the GGG mutation (mut1) would have no effect on Ac-TEAPLPGGVR abundance, while the AUG mutation (mut2) would eliminate Ac-TEAPLPGGVR. Conversely, if Ac-TEAPLPGGVR was derived from initiation at the GUG upstream of the ACG, the GGG mutation would eliminate Ac-TEAPLPGGVR, while the AUG mutation would enhance Ac-TEAPLPGGVR. We observed almost complete loss of Ac-TEAPLPGGVR from our mut1 GGGACG reporter and a significant increase in Ac-TEAPLPGGVR from our mut2 AUGACG reporter (Fig. 3C–E). We also detected Ac-MTEAPLPGGVR from mut2 (AUGACG) at levels below our threshold for accurate quantification (Fig. 3E, Supplementary Material, Fig. S3C), suggesting that this product is short-lived in cells. These results strongly suggest that Ac-TEAPLPGGVR is generated by GUG mediated Met-tRNAiMet initiation followed by iMet excision and identifies a previously overlooked near-cognate codon utilized for FMRpolyG synthesis.

Impact of ISR activation on initiation codon usage for FMRpolyG

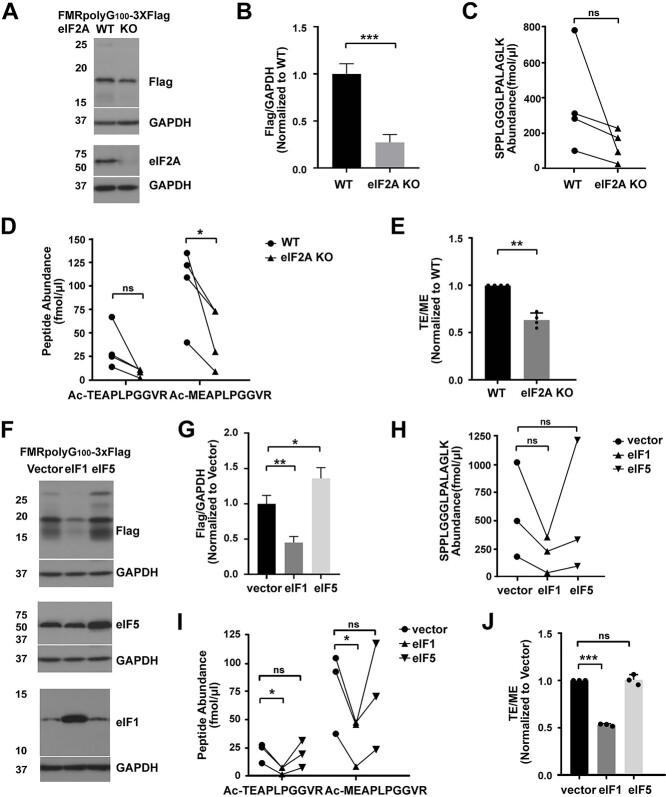

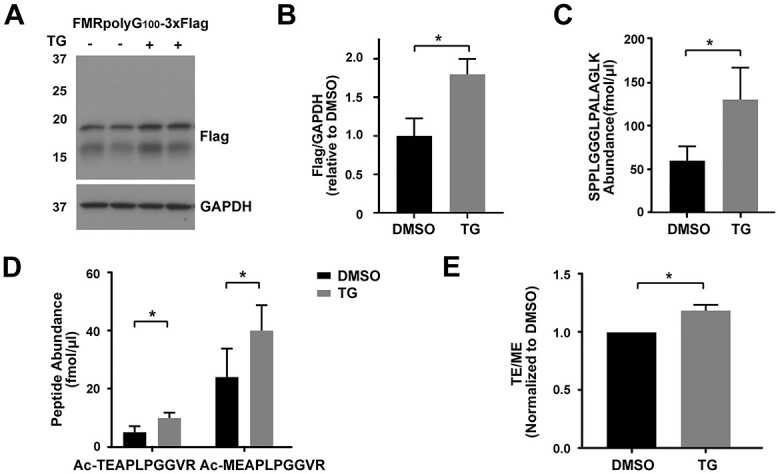

CGG RAN translation is selectively enhanced by the ISR in a near-cognate codon-specific manner (10). As our data support the role for two different initiation codons, GUG and ACG, we explored whether the ISR was preferentially promoting initiation at one or both of these codons. Similar to what we see with RAN translation-specific nanoluciferase reporters, we observed an ~2-fold increase in all three FMRpolyG-3xFlag peptides upon treatment with the ER stress inducer, thapsigargin (TG) [(10), Fig. 4A and B]. Using PRM-SIS quantification, both GUG- and ACG-mediated RAN translational initiations, as well as the C-terminal control peptide, were significantly enhanced by TG (Fig. 4C and D). However, the relative ratio of Ac-TEAPLPGGVR to Ac-MEAPLPGGVR was enhanced by Thapsigargin (Fig. 4E). This suggests that GUG-mediated initiation in particular may occur independent of the eIF2 TC.

Figure 4.

GUG initiation is preferentially utilized in response to cellular stress. (A) Representative WB of FMRpolyG from HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag followed by DMSO or TG treatment. GAPDH serves as a loading control. N = 3. (B) Quantification of FMRpolyG from the WB in (A). Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Unpaired t test, *P < 0.05. (C) The absolute abundance of SPPLGGGLPALAGLK by PRM-SIS in lysates of above samples. Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Paired t test, *P < 0.05. (D) Quantification of the absolute abundance of Ac-TEAPLPGGVR and Ac-MEAPLPGGVR by PRM-SIS in lysates of samples in (A). Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Paired t test, *P < 0.05. (E) Ratios of the two N-terminal peptides in TG versus DMSO-treated HEK293Ts. Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Paired t test, *P < 0.05.

FMRpolyG synthesis via GUG initiation is partially dependent on eIF2A and inhibited by eIF1 overexpression

During ISR activation, functional eIF2 is depleted, suggesting that initiation at these near-cognate codons likely requires an eIF2 alternative factor. One particular factor, eIF2A, is known to be upregulated during cellular stress (35,40,64) and was recently suggested to play a role in RAN translational initiation at G4C2 repeats in C9orf72 (22). Thus, we investigated whether eIF2A was required for ACG- or GUG-initiated RAN translation. We performed PRM-SIS on WT and eIF2A CRISPR-edited KO HAP1 cell lines (65) transfected with FMRpolyG100-3xFlag. We found that the loss of the alternative eIF2 factor, eIF2A, reduced total FMRpolyG but significantly suppressed GUG initiation by ~40%, relative to ACG mediated initiation (Fig. 5A–E). This suggests that GUG initiation is at least partially mediated by eIF2A.

Figure 5.

FMRpolyG initiation codon choice is influenced by eIF1 and eIF2A availability. (A) Representative WB of FMRpolyG from HAP1 WT and eIF2A KO cells transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag. GAPDH serves as a loading control. N = 4. (B) Quantification of FMRpolyG from the WB in (A). Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 4. Unpaired t test, ***P < 0.001. (C) Quantification of SPPLGGGLPALAGLK absolute abundance by PRM-SIS in Flag-IPed lysates of HAP1 cells transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag. N = 4. Paired t test, ns: not significant. (D) Quantification of Ac-TEAPLPGGVR and Ac-MEAPLPGGVR absolute abundance by PRM-SIS in Flag-IPed lysates of HAP1 cells transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag. N = 4. Paired t test, *P < 0.05, ns: not significant. (E) Ratio of the two N-terminal peptides in HAP1 WT and eIF2A KO cells transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag. Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 4. Paired t test, **P < 0.01. (F) Representative WB of FMRpolyG (top), eIF5 (middle) and eIF1 (bottom), from HEK293Ts co-transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag and control, eIF1 or eIF5 vectors. GAPDH serves as a loading control N = 3. (G) Quantification of FMRpolyG from the WB in (F). Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Unpaired t test, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. (H and I) Quantification of SPPLGGGLPALAGLK (H) and Ac-TEAPLPGGVR and Ac-MEAPLPGGVR (I) absolute abundance by PRM-SIS in Flag-IPed lysates of HEK293Ts co-transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag and control, eIF1 or eIF5 vectors. N = 3. Paired t test,*P < 0.05, ns: not significant. (J) Ratio of the two N-terminal peptides in HEK293Ts co-transfected with FMRpolyG100-3XFlag and control, eIF1 or eIF5 vectors. Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Paired t test, ***P < 0.001.

Non-canonical translation initiation can also be facilitated by altered levels of canonical translation initiation factors (66,67). Our lab has previously shown that CGG RAN translation decreases with eIF1 overexpression and increases with eIF5 overexpression (11). To determine whether eIF1 and/or eIF5 differentially affect ACG or GUG initiation, we co-expressed FMRpolyG100-3xFlag with either empty eIF1 or eIF5 expression vectors and performed PRM-SIS. While we did not observe an effect on total FMRpolyG or either N-terminal peptides with eIF5 overexpression, we found overexpression of eIF1 modestly decreased SPPLGGGLPALAGLK abundance and significantly decreased both Ac-MEAPLPGGVR or Ac-TEAPLPGGVR product abundance, with the impact being greater on Ac-TEAPLPGGVR product abundance, decreasing ~50% relative to Ac-MEAPLPGGVR (Fig. 5F–J). These data are consistent with eIF1 having a preferential effect on GUG initiation.

CGG RAN translation can initiate within the repeat in multiple reading frames

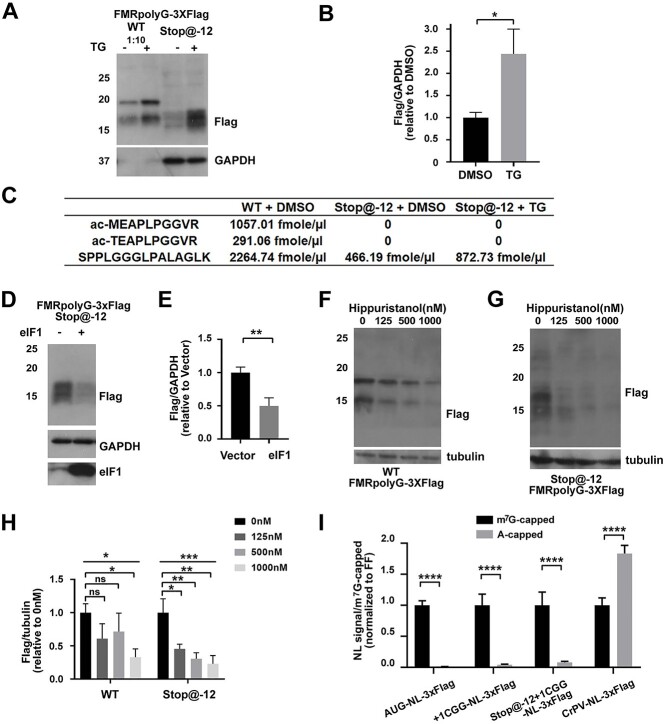

While CGG RAN initiation at near-cognate codons has been well established (4,6,10), it is not clear if initiation can also occur within the CGG repeat itself. Using a reporter in which a stop codon was placed 12 nucleotides 5′ of the CGG repeat (stop@-12) [(4), Supplementary Material, Table S2], we were able to observe a series of faint bands via WB that corresponded in size to the lower band typically seen for FMRpolyG (Fig. 6A and B and Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Using PRM-MS, we did not detect any of the N-terminal peptides in the stop@-12 transfected cell lysates but did observed a 4.9-fold decrease in the C-terminal peptide for the stop@-12 transfected lysates compared with those transfected with the WT FMRpolyG reporter (Fig. 6C). Similar to prior observations of RAN translation at near-cognate codons, we observed a ~2-fold increase in abundance from the stop@-12 reporter following TG treatment [(10), Fig. 6A–C].

Figure 6.

CGG RAN translation can initiate within the repeat. (A) Representative WB of FMRpolyG from HEK293Ts transfected with the indicated reporters followed by DMSO or TG treatment. GAPDH serves as a loading control. Lysates from WT FMRpolyG transfected cells were diluted 1:10 to account for signaling differences between WT FMRpolyG and stop@-12 reporters. See Supplementary Material, Figure S4A for an undiluted version. (B) Quantification of stop@-12 from the WB in (A). Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Unpaired t test, *P < 0.05. (C) Absolute amounts of FMRpolyG signature peptides by PRM-SIS from IPed lysates of HEK293Ts transfected with the indicated reporters and treatment from (A). (D and E) Representative WB and quantification of FMRpolyG from HEK293Ts co-transfected with the stop@-12 reporter and control or eIF1 vector. GAPDH serves as a loading control. Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 3. Unpaired t test, **P < 0.01. (F and G) WB of FMRpolyG-Flag from HEK293Ts transfected with FMrpolyG-3xF (F) or stop@-12 contructs (G) and treated with hippuristanol for 10 h. Tubulin serves as a loading control. N = 3. (H) Quantification of FMRpolyG-Flag from the WBs in (F) and (G). Bars represent mean ± SD. N = 3. One-way ANOVA and unpaired t test. ns: not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (I) Quantification of nanoluciferase signal from HEK293Ts transfected with indicated reporters. Bars represent mean ± SD, N = 9. Multiple T-test comparison. ****P < 0.0001.

We next determined whether initiation within the repeat was influenced by the availability of canonical translation initiation factors. When we overexpressed eIF1, we saw a ~40% reduction in FMRpolyG-3xF in our stop@-12 reporter, similar to what we observed for our reporters that can initiate at near-cognate codons above the repeat (Fig. 6D and E compared with Fig. 5F and I). Previously, we showed that RAN translation of FMRpolyG from upstream codons was primarily scanning-dependent (6). To determine if FMRpolyG initiation within the repeat was also scanning dependent, we treated cells transfected with our WT and stop@-12 reporters with the eIF4A helicase inhibitor, hippuristanol. Hippuristanol reduced translation in a canonical AUG-driven reporter in a dose-dependent manner and also caused a similar decrease in FMRpolyG, particularly at higher concentrations (Fig. 6F and H and Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B–D). In our stop@-12 reporter, we observed a similar inhibition by hippuristanol, suggesting that initiation within the repeat also requires eIF4A (Fig. 6G and H). We have also previously shown that translation of FMRpolyG is cap-dependent (6). To determine whether initiation within the repeat is also cap-dependent, we transfected cells with either m7G-capped or non-functional A-capped +1CGG100-NL-3xF and stop@-12-CGG100-NL-3xF mRNA reporters. Consistent with previously published work, our canonically translated AUG-NL-3xF and + 1CGG100-NL-3xF reporters were almost entirely cap-dependent, while a CrPV IRES reporter was not (6,10). The stop@-12-CGG100-NL-3xF reporter was also significantly cap-dependent, as we observed >90% decrease in signal in our A-capped versus m7G-capped transfected cells (Fig. 6I).

These data are largely consistent with our previously published data on initiation in the +2 CGG RAN reading frame which produces a polyalanine containing protein (FMRpolyA) that accumulates at low levels in FXTAS patient brains (19). The +2 CGG reading frame has no near-cognate codons upstream of the repeat but is similarly affected by ISR activation, eIF1 availability and cap-dependency (6,10,11). To evaluate whether we could directly observe initiation products within the repeat, we performed DDA MS on Flag-IPed lysates from cells transfected with RAN-initiated and AUG-initiated FMRpolyA-FLAG reporters. The AUG-driven reporter has an additional 21 nt insertion downstream of the repeat, allowing us to distinguish products made from this specific reporter (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). Following Glu-C digestion, we observed the same C-terminal control fragment from both reporters and the expected N-terminal fragment for the AUG-driven reporter that would be produced following iMet excision (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). Consistent with prior results of polyalanine initiation within CAG repeats (79), we observed peptide fragments that started with alanine with no preceding initiation codon or cleavage site starting ~70–80 GCG codons into the repeat. These products were detectable even when an AUG start codon was placed upstream of the repeat in the same reading frame (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). Taken in the context of our prior work (6), these data suggest that RAN translation at near-cognate codons just upstream of the repeat and within multiple reading frames of the CGG repeat itself shares similar base requirements for initiation.

Discussion

RAN translated proteins have emerged as important participants in the pathogenesis of multiple neurodegenerative disorders. Accurate quantification of these proteins and a deep understanding of the mechanisms underlying their production are both key steps in biomarker and therapy development for these currently untreatable diseases. Here, using a highly sensitive MS method, PRM-SIS, we identified N-terminal and C-terminal peptides of FMRpolyG in transfected samples and in patient cells and tissues. By comparing endogenous values to their respective SIS, we quantified the absolute amount of FMRpolyG in patient brain tissue, uncovering a range of FMRpolyG abundance in patients. This MS-based methodology also allowed us to identify a novel GUG initiation site for FMRpolyG production and provide evidence for RAN translational initiation of FMRpolyG from within the CGG repeat itself. We find that initiation at both near-cognate codons and within the repeat itself was similarly affected by conditions of stress and perturbations in initiation factor abundance. Altogether, these data provide new insights into both RAN translation at CGG repeats and the pathogenesis of FXTAS and related repeat expansion disorders.

An important open question in the field is whether there is one or multiple mechanisms for non–AUG-mediated translational initiation at expanded repeats (68,69). Understanding how RAN translation works mechanistically is critical if we are to successfully target this process therapeutically. Both IRES and ribosomal scanning-dependent initiation mechanisms have been suggested for RAN translation at different repeat expansions (5,6,10,16,21,22,70,71). Our data suggest that, at least for CGG repeats derived from a linear mRNA, key mechanistic features are shared for both initiation at a near-cognate codon upstream of the repeat and initiation at non-cognate sites within the repeat. Specifically, in both cases and in multiple reading frames, initiation within the CGG repeat is strongly impacted by cellular stress, availability of the start codon stringency factor eIF1, activity of the critical RNA helicase eIF4A and the presence of a 5′ cap.

A limitation of our study is that we are only detecting products generated in a single reading frame. This means that the residual signal we observe in our stop@-12 reporter may be detecting initiation occurring within the repeat by a cap-dependent, non–IRES-mediated pathway (e.g. 40 s queuing behind a paused 80 s or the residual signal may be in part the result of stop codon read through or frameshifting from another reading frame. While additional studies needed to delineate these possibilities are ongoing, the data here are largely consistent with initiation within the repeat itself and this supposition is supported by our previous work on RAN translation the +2 (GCG, alanine) reading frame of this same repeat (4,6). In those studies, synthesis of the polyalanine product (FMRpolyA) was cap-dependent, upregulated following stress and downregulated following eIF1 overexpression or eIF4A inhibition (6,10,11), just as we observe here for synthesis of FMRpolyG. For FMRpolyA, we directly observed products generated by initiation within the repeat by MS even when an AUG codon is placed upstream of the repeat (Supplementary Material, Fig. S5). This finding is consistent with published data on alanine frame RAN translation from CAG repeats associated with spinocerebellar Ataxia Type 8 (5). Interestingly, while initiation at non-cognate codons is extremely rare, a number of genes beginning with polyalanine stretches can initiate at GCG codons, and there is at least one example of a GGC codon being utilized (60). Taken together, these data suggest mechanistic convergence for +1 and +2 CGG RAN translation initiation events and suggest that factors that mediate near-cognate codon initiation can play a prominent role even when codons are dramatically different from a canonical AUG.

We and others previously defined contributions from near-cognate codons 5′ to the repeat in FMR1 by mutational analysis, which identified 2 key codons as likely drivers of FMRpolyG production (4,6,16). Here, we identify a third near-cognate codon as a meaningful contributor to FMRpolyG production. How initiation site choice is made at these near-cognate codons on FMR1 is not fully understood, but our data provide some insight. We observe that loss of eIF2A reduces RAN translation from both ACG and GUG initiation, with the effect being particularly dramatic for GUG initiation, reducing it 2-fold relative to ACG initiation (Fig. 5E). eIF2A has been implicated in CUG-initiated RAN translation of G4C2 repeats in C9orf72 (22) and in RAN translation from CCUG repeats in myotonic dystrophy type II (44), suggesting a common RAN translation initiation mechanism utilized across various repeat expansion disorders. Furthermore, eIF2A has also been implicated in Met-tRNAiMet-mediated initiation at CUG and UUG codons (35,43,72), which share more similarity to GUG than ACG, and could explain the preferential decrease in GUG initiation in our case.

We also observe that GUG initiation is enhanced more so than ACG initiation upon activation of the ISR. There are two likely reasons for this. First, eIF2A expression increases in response to cellular stress and likely contributes more to GUG CGG RAN initiation than and ACG CGG RAN initiation during stress (35,40,73). Alternatively, this differential stress response may reflect differential TC recruitment following 40S ribosomal scanning. ACG has the second lowest free energy of any near-cognate codon (after CUG) and is more efficient at initiating under non-stressed conditions (38). However, TC binding to a ribosome already sitting on an initiation codon is much stronger and more efficient when the ribosome is on a GUG versus an ACG (37). Therefore, under non-stressed conditions, when the TC is bound to the PIC, ACG is the more favorable codon; however, under stress, when TC recruitment occurs following PIC loading and scanning, GUG initiation becomes more favorable. Similarly, reduced GUG initiation in the setting of eIF1 overexpression is consistent with previous in vitro work showing eIF1 primarily acts by discriminating codons based on the first position (38). In this system, eIF1 overexpression strongly represses translation from GUG but not ACG codons (11,74,75).

A current paradox in the field is the ability to readily detect FMRpolyG by IHC in FXTAS cases and model systems while observing comparably low levels by MS (4,6,16,17,19,20). Our PRM-SIS methodology exhibited excellent quantification characteristics in both CSF and cell lysates, with limits of detection for specific FMRpolyG peptides in the sub-nanomolar range. Moreover, IP led to enrichment of FMRpolyG peptides in a linear fashion from transfected cells (Figs 2B and3B), suggesting that the biochemistry of the peptides is not altered at higher concentrations. This strategy led to reliable detection and quantification of FMRpolyG in both FXTAS patient brains and cells, confirming the presence of FMRpolyG in FXTAS patient tissue and demonstrating definitively that initiation at near-cognate codons above the repeat contributes to its production in people. However, despite its sensitivity, we were not able to measure FMRpolyG using this methodology in CSF and its total abundance in FXTAS patients remained quite low. Additionally, we did not observe a correlation between repeat length and FMRpolyG abundance (6), although this study lacks sufficient statistical power to draw a firm conclusion on this relationship.

The reasons for the low FMRpolyG signal and variation between patients are unclear. Our IP strategy likely failed to capture all of the endogenous FMRpolyG protein, given that our N-terminal antibody would not capture products generated from initiation within the repeat or from near-cognate codons closer to the repeat. To date, C-terminally targeted antibodies to FMRpolyG have not been sufficiently robust to allow for effective IP of this endogenous protein from brain tissue [(4,16,19), and data not shown]. This observation is consistent with our PRM-SIS analysis that failed to reliably detect the C-terminal peptide in patient tissue and previously published studies in human FXTAS brain samples, where the C-terminal peptide was only detected at very low levels (20). While we cannot be sure why this peptide was not readily detected, one possibility is that the C-terminus is cleaved from aggregated FMRpolyG proteins. It is also possible that translation which initiates 5′ to the repeat may terminate during translation through the repeat sequence to create a product that would not be captured by our PRM-SIS analysis. Given the multiple initiation sites, including within the repeat, and the insolubility of the protein, fully sorting out these relationships is challenging. Regardless, while our data demonstrate that PRM-MS is capable of reliably quantifying FMRpolyG at high abundance, the low level of detection in endogenous samples indicates that alternative approaches will be needed if this protein is to serve as a viable biomarker in FXTAS.

In sum, we describe a new tool for quantifying the non–AUG-initiated CGG repeat product, FMRpolyG, and provide mechanistic insights into CGG RAN translation, including evidence of initiation within the repeat in both the +1 and +2 reading frames and a specific role for a previously overlooked initiation codon. Despite the complexities intrinsic to the study of RAN translation, where initiation can occur in multiple frames and produce a myriad of potential products, our study suggests that mechanistic features shared across initiation events may provide common therapeutic targets for future development. Further work into these mechanistic targets is warranted, as are efforts to measure RAN translation products as a biomarker in FXTAS and related repeat disorders.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and culture

HEK293Ts were obtained from ATCC and grown in high-glucose DMEM with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S). WT and eIF2A KO Hap1 cells were obtained from Horizon Discovery (Cat #HZGHC002650c001) (65) and grown in IMDM with 10% FBS, 1% P/S. All cell lines were maintained in 10 cm dishes at 37°C.

Reporters

FMRpolyG100-3XFlag and FMRpolyG100 RAN translation reporters were made by cloning in their respective sequences into pcDNA3.1+ between BamHI and PspOMI. stop@-12, mut1 (GGGACG) and mut2 (AUGACG) were made using Q5 site-directed mutagenesis of the FMRpolyG100-3XFlag plasmid (Supplementary Material, Table S2). ATG-NL-3xFlag, +1CGG-NL-3xFlag, +2CGG-NL-3xF, AUG +2CGG-NL-3xF, stop-12-NL-3xFlag, eIF1 and eIF5 expression vectors are previously published (6,10,11,75).

Transfection and treatment

HEK293Ts were seeded at 4.0 × 106 cells/10 cm dish and transfected at ~60–70% confluency for 24 h with 10 μg of indicated plasmid and 3:1 Fugene HD to DNA. For stress-induced experiments, the cells were transfected as above for 19 h followed by 5 h with specified drugs (Tg, DMSO). For eIF1 and eIF5 experiments, HEK293Ts were seeded as above and cotransfected for 24 h with 2.5 μg reporter plasmids and 25 μg of either pcDNA3.1+ vector, eIF1 or eIF5 and 3:1 Fugene HD to DNA.

Hap1 WT and eIF2A KO cells were seeded at 7.0 × 106 cells/10 cm dish and transfected at ~60–70% confluency for 24 h with 10 μg of FMRpolyG100-3XFlag and 3:1 Genjet to DNA.

For hippuristanol experiments, HEK293Ts were seeded at 2.5 × 105 cells/ml and transfected 24 h later with AUG-NanoLuc-3xFlag, FMRpolyG100-3XFlag or stop@-12. Cells were lysed for WB 48 h post-tranfection, 10 h after treatment with hippuristanol at indicate concentrations (76).

Cap-dependent experiments have been previously described (6). In brief, in vitro RNA was synthesized using the HiScribe T7 High Yield RNA Synthesis Kit (E2040S, NEB, Rowley, MA, USA) according to manufacturer protocol. HEK293Ts were seeded at 2 × 104 cells per well on a 96-well plate; 24 h after seeding, cells were co-transfected with 50 μg in vitro transcribed nanoluciferase RNA and 50 μg firefly RNA using Mirus Bio TransIT-mRNA Transfection Kit (MIR-2225, Thermo Fisher, Sci, Waltham, MA, USA); 24 h after transfection, firefly and nanoluciferase levels were measured as previously described (6).

Clinical specimens

FXS iPSCs were obtained from Wicell (77). Control 2E iPSC line was obtained from the Parent lab at the University of Michigan and has been previously published (15). FXTAS peripheral lymphocytes (LCL1) were kindly gifted to us by Stephanie Sherman, and FXTAS skin fibroblasts (F3) and FXS skin fibroblasts (4026) were kindly gifted by Paul Hagerman. All have been previously reported (78,79). The 3 FXTAS patient frozen brain tissues (FXTAS1-1906, FXTAS2-345 and FXTAS3-1558) and 2 control frozen brain tissues (control1-382 and control2-8662) were obtained from the University of Michigan Brain Bank. FXTAS patient CSF samples were obtained from Rush University Children’s Hospital, and control CSF pool was purchased from Biochemed Services (3057BF). The information for these human derived samples is presented in Supplementary Material, Table S2.

Lymphocyte cells were grown in 1640 RPMI containing 10% FBS and 1% P/S. Skin fibroblasts were grown in high-glucose DMEM with 10% FBS, 1% non-essential amino acid (NEAA) and 1% P/S. The CSF and brain tissues were kept in frozen in −80°C until use.

IP and silver staining gel

Samples were immunoprecipitated according to manufacturer’s protocol (LSKMAGAG02, Millipore, Danvers, MA, USA). In brief, cells were washed with 1XPBS 2× then lysed with RIPA buffer (PI89900, Thermo Fisher, Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) with Complete™, Mini Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (11836153001, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). Protein concentration for each sample was determined by Pierce™ BCA protein assay kit (23 225, Thermo Scientific™); 1.5–4.0 mg of lysate from FMRpolyG100 transfected cells or 1.5–5 mg of human-derived samples were incubated with NTF1 antibody overnight at 4°C followed by adding PureProteome protein A/G mix magnetic beads for another 2 h; 1.5–4.0 mg of lysate from FMRpolyG100-3XFlag, or + 2CGG-NL-3XFlag, or 5.6 mg of lysate from stop@-12 transfected cells were incubated with anti-flag M2 magnetic beads (M8823, Sigma, MA, USA) overnight at 4°C. Beads were washed 3× with 1XTBS for 5 min at 4°C. IPed proteins were isolated by directly digesting on the beads themselves for MS.

Ultracentrifugation

Samples were centrifuged at 70 000 g for 1 h. The pellet was resuspended in 8 M urea, and both the supernatant and the pellet were run on a 15% SDS-PAGE and blotted with the indicated antibodies.

Enzymatic digests

For trypsin experiments, lysates from HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100 or FMRpolyG100-3XFlag (dilute to 1 μg/μl) were digested with indicated amounts of trypsin (1 μg/μl) at 37°C for 1 h. For lysostaphin (LS) experiments, lysates from HEK293Ts transfected with FMRpolyG100 were digested with indicated amounts of LS at room temperature for 1 h. For Glu-C experiments, Flag-IPed lysates from HEK293Ts transfected with +2CGG-NL-3xFlag or AUG +2-NL-3xFlag reporters were denatured in 8 M urea followed by digested with 1 μg/μl Pierce Glu-C Protease prior to DDA-MS.

Western blot

WBs were performed according to standard protocol (19). The following antibodies were used for WBs where indicated: NTF1 [1:1000, rabbit (35)], Flag M2 (1:1000, mouse, F1804, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA), eIF2A (1:8000, rabbit, 11 233–1-AP, ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL, USA), eIF1 (1:1000, rabbit, 12496S, CST, Beverly, MA, USA), eIF5 (1:1000, rabbit, 13894S, CST), tubulin-β (mouse, 1:1000, E7, DSHB, Iowa City, IA, USA) and GAPDH (mouse, 1:2000, sc-32 233, SCBT, Dallas, TX, USA) in 5% milk. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies, goat anti-mouse HRP (111-035-146, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) and goat anti-rabbit HRP (111-035-144, Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) were used at 1:5000 in 5% milk.

Sample digestion for MS

The silver stained gel slice was destained according to the manufacturer’s protocol (PROTSIL2-1KT, Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). The digestion for gel slice, whole lysates and IPed beads were done according to previously published protocols (80).

Liquid chromatography MS

A hybrid quadrupole-orbitrap mass spectrometer (MS, Q Exactive HF, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) coupled to nano-Ultra High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (UHPLC, Ultimate 3000 RSLC Nano, Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for acquiring all MS data. For UHPLC, the procedures were according to protocol (81).

Resolved peptides were directly sprayed onto the MS operating in either DDA or PRM (targeted) mode.

For DDA mode, the MS was set to collect one high-resolution MS1 scan (60 000 FWHM @200 m/z; scan range 400–1500 m/z) followed by data-dependent High-energy C-trap Dissociation MS/MS (HCD) spectra on the 20 most abundant ions observed in MS1. Other MS parameters were as previously published (80).

For PRM mode: Synthetic peptides with heavy isotope labeled arginine or lysine at the C-termini were obtained from ThermoScientific (AQUA Ultimate grade, 99% pure, ±5% quantitation precision). The digested samples [50 μg of whole cell lysate or IPed peptides (from 1.5 to 4 mg of whole cell lysate) on beads] were spiked with 25 fmol/μl of heavy synthetic peptides prior to UHPLC separation. In PRM mode, the quadrupole was set to isolate only the desired precursor ions (see Supplementary Material, Table S1) followed by HCD-MS/MS on the isolated ions.

Protein identification

Proteome Discoverer (v2.1; Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) was used for data analysis. MS2 spectra were searched against latest SwissProt human protein database (42 054 sequences) using the following search parameters: MS1 and MS2 tolerance were set to 10 ppm and 0.1 Da, respectively; carbamidomethylation of cysteines (57.02146 Da) was considered a static modification; acetylation of protein N-terminus, oxidation of methionine (15.9949 Da) and deamidation of asparagine and glutamine (0.98401 Da) were considered as variable modifications. Percolator algorithm (PD2.1) was used to determine the false discovery rate (FDR) and proteins/peptides with ≤1% FDR were retained for further analysis. MS/MS spectra assigned to the peptides of interest were manually examined.

Protein quantification by PRM

The raw data were processed using Skyline 4.1.0.18169. A spectral library was created in Skyline for some of the target peptides using several DDA of FMRpolyG samples as well as blanks spiked with AQUA Ultimate endogenous (light) and isotopically labeled (heavy) peptides obtained from ThermoFisher Scientific (Supplementary Material, Table S1). Product ions (minimum of 3) as determined by DDA analysis or Skyline prediction were monitored for each peptide (see the Condensed Transition List.xlsx attachment). Samples analyzed by PRM were spiked with 25 fmol/μl of heavy peptides and the concentration of the endogenous peptide was determined by comparison of the area ratios.

Statistical analysis

Blots were quantified by Image J software from National Institutes of Health. Data plots and statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism 7. The error bars represent standard deviation (SD) of the mean. Unpaired t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for WB blots intensity. Paired t-test was applied for all PRM-SIS quantification value analysis. We set P < 0.05 as the cutoff for significance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Michigan Brain Bank, for access to tissues. We thank the University of Michigan Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics Resource Facility for their assistance and use of equipment. We thank Katelyn Green for providing eIF2A KO HAP1 cells, sharing unpublished data and intellectual input.

Conflict of Interest statement. The authors declare that they have no relevant financial conflicts of interest related to the work presented in this manuscript. Specifically, there have been no involvements by any of the authors that might raise the question of bias in the work reported or in the conclusions, implications or opinions stated.

Contributor Information

Yuan Zhang, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Department of Respiratory Medicine, Xiangya Hospital, Central South University, Changsha 410008, China.

M Rebecca Glineburg, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Venkatesha Basrur, Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Kevin Conlon, Department of Pathology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Shannon E Wright, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Amy Krans, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Deborah A Hall, Department of Neurological Sciences, Rush University, Chicago, IL, USA.

Peter K Todd, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA; Ann Arbor Veterans Administration Healthcare, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Funding

National Institutes of Health (P50HD104463, R01NS099280, R01NS086810 to P.K.T., F31NS113513 to S.E.W., T32NS00722237 to M.R.G.); Veterans Affairs (BLRD BX004842 to P.K.T.). D.A.H. and P.K.T. also received additional private philanthropic support.

References

- 1. Greco, C.M., Berman, R.F., Martin, R.M., Tassone, F., Schwartz, P.H., Chang, A., Trapp, B.D., Iwahashi, C., Brunberg, J., Grigsby, J.et al. (2006) Neuropathology of fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome (FXTAS). Brain, 129, 243–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Greco, C.M., Hagerman, R.J., Tassone, F., Chudley, A.E., Del Bigio, M.R., Jacquemont, S., Leehey, M. and Hagerman, P.J. (2002) Neuronal intranuclear inclusions in a new cerebellar tremor/ataxia syndrome among fragile X carriers. Brain, 125, 1760–1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glineburg, M.R., Todd, P.K., Charlet-Berguerand, N. and Sellier, C. (2018) Repeat-associated non-AUG (RAN) translation and other molecular mechanisms in Fragile X Tremor Ataxia Syndrome. Brain Res., 1693, 43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Todd, P.K., Oh, S.Y., Krans, A., He, F., Sellier, C., Frazer, M., Renoux, A.J., Chen, K.C., Scaglione, K.M., Basrur, V.et al. (2013) CGG repeat-associated translation mediates neurodegeneration in fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. Neuron, 78, 440–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zu, T., Gibbens, B., Doty, N.S., Gomes-Pereira, M., Huguet, A., Stone, M.D., Margolis, J., Peterson, M., Markowski, T.W., Ingram, M.A.et al. (2011) Non-ATG-initiated translation directed by microsatellite expansions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 108, 260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kearse, M.G., Green, K.M., Krans, A., Rodriguez, C.M., Linsalata, A.E., Goldstrohm, A.C. and Todd, P.K. (2016) CGG Repeat-Associated Non-AUG Translation Utilizes a Cap-Dependent Scanning Mechanism of Initiation to Produce Toxic Proteins. Mol. Cell, 62, 314–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Krzyzosiak, W.J., Sobczak, K., Wojciechowska, M., Fiszer, A., Mykowska, A. and Kozlowski, P. (2012) Triplet repeat RNA structure and its role as pathogenic agent and therapeutic target. Nucleic Acids Res., 40, 11–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Verma, A.K., Khan, E., Mishra, S.K., Mishra, A., Charlet-Berguerand, N. and Kumar, A. (2020) Curcumin Regulates the r(CGG)(exp) RNA Hairpin Structure and Ameliorate Defects in Fragile X-Associated Tremor Ataxia Syndrome. Front. Neurosci., 14, 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zumwalt, M., Ludwig, A., Hagerman, P.J. and Dieckmann, T. (2007) Secondary structure and dynamics of the r(CGG) repeat in the mRNA of the fragile X mental retardation 1 (FMR1) gene. RNA Biol., 4, 93–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green, K.M., Glineburg, M.R., Kearse, M.G., Flores, B.N., Linsalata, A.E., Fedak, S.J., Goldstrohm, A.C., Barmada, S.J. and Todd, P.K. (2017) RAN translation at C9orf72-associated repeat expansions is selectively enhanced by the integrated stress response. Nat. Commun., 8, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Linsalata, A.E., He, F., Malik, A.M., Glineburg, M.R., Green, K.M., Natla, S., Flores, B.N., Krans, A., Archbold, H.C., Fedak, S.J.et al. (2019) DDX3X and specific initiation factors modulate FMR1 repeat-associated non-AUG-initiated translation. EMBO Rep., 20, e47498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoem, G., Bowitz Larsen, K., Overvatn, A., Brech, A., Lamark, T., Sjottem, E. and Johansen, T. (2019) The FMRpolyGlycine Protein Mediates Aggregate Formation and Toxicity Independent of the CGG mRNA Hairpin in a Cellular Model for FXTAS. Front. Genet., 10, 249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hukema, R.K., Buijsen, R.A., Schonewille, M., Raske, C., Severijnen, L.A., Nieuwenhuizen-Bakker, I., Verhagen, R.F., vanDessel, L., Maas, A., Charlet-Berguerand, N., De Zeeuw, C.I.et al. (2015) Reversibility of neuropathology and motor deficits in an inducible mouse model for FXTAS. Hum. Mol. Genet., 24, 4948–4957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Oh, S.Y., He, F., Krans, A., Frazer, M., Taylor, J.P., Paulson, H.L. and Todd, P.K. (2015) RAN translation at CGG repeats induces ubiquitin proteasome system impairment in models of fragile X-associated tremor ataxia syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet., 24, 4317–4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rodriguez, C.M., Wright, S.E., Kearse, M.G., Haenfler, J.M., Flores, B.N., Liu, Y., Ifrim, M.F., Glineburg, M.R., Krans, A., Jafar-Nejad, P.et al. (2020) A native function for RAN translation and CGG repeats in regulating fragile X protein synthesis. Nat. Neurosci., 23, 386–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sellier, C., Buijsen, R.A.M., He, F., Natla, S., Jung, L., Tropel, P., Gaucherot, A., Jacobs, H., Meziane, H., Vincent, A.et al. (2017) Translation of Expanded CGG Repeats into FMRpolyG Is Pathogenic and May Contribute to Fragile X Tremor Ataxia Syndrome. Neuron, 93, 331–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Buijsen, R.A., Sellier, C., Severijnen, L.A., Oulad-Abdelghani, M., Verhagen, R.F., Berman, R.F., Charlet-Berguerand, N., Willemsen, R. and Hukema, R.K. (2014) FMRpolyG-positive inclusions in CNS and non-CNS organs of a fragile X premutation carrier with fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Acta. Neuropathol. Commun., 2, 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Buijsen, R.A., Visser, J.A., Kramer, P., Severijnen, E.A., Gearing, M., Charlet-Berguerand, N., Sherman, S.L., Berman, R.F., Willemsen, R. and Hukema, R.K. (2016) Presence of inclusions positive for polyglycine containing protein, FMRpolyG, indicates that repeat-associated non-AUG translation plays a role in fragile X-associated primary ovarian insufficiency. Hum. Reprod., 31, 158–168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Krans, A., Skariah, G., Zhang, Y., Bayly, B. and Todd, P.K. (2019) Neuropathology of RAN translation proteins in fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Acta. Neuropathol. Commun., 7, 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ma, L., Herren, A.W., Espinal, G., Randol, J., McLaughlin, B., Martinez-Cerdeno, V., Pessah, I.N., Hagerman, R.J. and Hagerman, P.J. (2019) Composition of the Intranuclear Inclusions of Fragile X-associated Tremor/Ataxia Syndrome. Acta. Neuropathol. Commun., 7, 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cheng, W., Wang, S., Mestre, A.A., Fu, C., Makarem, A., Xian, F., Hayes, L.R., Lopez-Gonzalez, R., Drenner, K., Jiang, J.et al. (2018) C9ORF72 GGGGCC repeat-associated non-AUG translation is upregulated by stress through eIF2alpha phosphorylation. Nat. Commun., 9, 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sonobe, Y., Ghadge, G., Masaki, K., Sendoel, A., Fuchs, E. and Roos, R.P. (2018) Translation of dipeptide repeat proteins from the C9ORF72 expanded repeat is associated with cellular stress. Neurobiol. Dis., 116, 155–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Westergard, T., McAvoy, K., Russell, K., Wen, X., Pang, Y., Morris, B., Pasinelli, P., Trotti, D. and Haeusler, A. (2019) Repeat-associated non-AUG translation in C9orf72-ALS/FTD is driven by neuronal excitation and stress. EMBO Mol. Med., 11, e9423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hershey, J.W.B. and Merrick, W.C. (2000) Translational Control of Gene Expression. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Long Island, NY, pp. 33–88. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hinnebusch, A.G. (2011) Molecular mechanism of scanning and start codon selection in eukaryotes, Microbiol Mol. Biol. Rev., 75, 434–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jackson, R.J., Hellen, C.U. and Pestova, T.V. (2010) The mechanism of eukaryotic translation initiation and principles of its regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 11, 113–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sonenberg, N. and Hinnebusch, A.G. (2009) Regulation of translation initiation in eukaryotes: mechanisms and biological targets. Cell, 136, 731–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Walter, P. and Ron, D. (2011) The unfolded protein response: from stress pathway to homeostatic regulation. Science, 334, 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hinnebusch, A.G., Ivanov, I.P. and Sonenberg, N. (2016) Translational control by 5-untranslated regions of eukaryotic mRNAs. Science, 352, 1413–1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Imataka, H., Olsen, H.S. and Sonenberg, N. (1997) A new translational regulator with homology to eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4G. EMBO J., 16, 817–825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ingolia, N.T., Ghaemmaghami, S., Newman, J.R. and Weissman, J.S. (2009) Genome-wide analysis in vivo of translation with nucleotide resolution using ribosome profiling. Science, 324, 218–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ingolia, N.T., Lareau, L.F. and Weissman, J.S. (2011) Ribosome profiling of mouse embryonic stem cells reveals the complexity and dynamics of mammalian proteomes. Cell, 147, 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kearse, M.G., Goldman, D.H., Choi, J., Nwaezeapu, C., Liang, D., Green, K.M., Goldstrohm, A.C., Todd, P.K., Green, R. and Wilusz, J.E. (2019) Ribosome queuing enables non-AUG translation to be resistant to multiple protein synthesis inhibitors. Genes Dev., 33, 871–885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwab, S.R., Shugart, J.A., Horng, T., Malarkannan, S. and Shastri, N. (2004) Unanticipated antigens: translation initiation at CUG with leucine. PLoS Biol., 2, e366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Starck, S.R., Tsai, J.C., Chen, K., Shodiya, M., Wang, L., Yahiro, K., Martins-Green, M., Shastri, N. and Walter, P. (2016) Translation from the 5 untranslated region shapes the integrated stress response. Science, 351, aad3867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kearse, M.G. and Wilusz, J.E. (2017) Non-AUG translation: a new start for protein synthesis in eukaryotes. Genes Dev., 31, 1717–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kolitz, S.E., Takacs, J.E. and Lorsch, J.R. (2009) Kinetic and thermodynamic analysis of the role of start codon/anticodon base pairing during eukaryotic translation initiation. RNA, 15, 138–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lind, C. and Aqvist, J. (2016) Principles of start codon recognition in eukaryotic translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res., 44, 8425–8432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Tang, L., Morris, J., Wan, J., Moore, C., Fujita, Y., Gillaspie, S., Aube, E., Nanda, J., Marques, M., Jangal, M.et al. (2017) Competition between translation initiation factor eIF5 and its mimic protein 5MP determines non-AUG initiation rate genome-wide. Nucleic Acids Res., 45, 11941–11953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kim, E., Kim, J.H., Seo, K., Hong, K.Y., An, S.W.A., Kwon, J., Lee, S.V. and Jang, S.K. (2018) eIF2A, an initiator tRNA carrier refractory to eIF2alpha kinases, functions synergistically with eIF5B. Cell. Mol. Life Sci., 75, 4287–4300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kim, J.H., Park, S.M., Park, J.H., Keum, S.J. and Jang, S.K. (2011) eIF2A mediates translation of hepatitis C viral mRNA under stress conditions. EMBO J., 30, 2454–2464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Komar, A.A., Gross, S.R., Barth-Baus, D., Strachan, R., Hensold, J.O., Goss Kinzy, T. and Merrick, W.C. (2005) Novel characteristics of the biological properties of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae eukaryotic initiation factor 2A. J. Biol. Chem., 280, 15601–15611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Starck, S.R., Jiang, V., Pavon-Eternod, M., Prasad, S., McCarthy, B., Pan, T. and Shastri, N. (2012) Leucine-tRNA initiates at CUG start codons for protein synthesis and presentation by MHC class I. Science, 336, 1719–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tusi, S.K., Nguyen, L., Thangaraju, K., Li, J., Cleary, J.D., Zu, T. and Ranum, L.P.W. (2021) The alternative initiation factor eIF2A plays key role in RAN translation of myotonic dystrophy type 2 CCUG*CAGG repeats. Hum. Mol. Genet., 30, 1020–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Algire, M.A., Maag, D. and Lorsch, J.R. (2005) Pi release from eIF2, not GTP hydrolysis, is the step controlled by start-site selection during eukaryotic translation initiation. Mol. Cell, 20, 251–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Maag, D., Fekete, C.A., Gryczynski, Z. and Lorsch, J.R. (2005) A conformational change in the eukaryotic translation preinitiation complex and release of eIF1 signal recognition of the start codon. Mol. Cell, 17, 265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Passmore, L.A., Schmeing, T.M., Maag, D., Applefield, D.J., Acker, M.G., Algire, M.A., Lorsch, J.R. and Ramakrishnan, V. (2007) The eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF1 and eIF1A induce an open conformation of the 40S ribosome. Mol. Cell, 26, 41–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Unbehaun, A., Borukhov, S.I., Hellen, C.U. and Pestova, T.V. (2004) Release of initiation factors from 48S complexes during ribosomal subunit joining and the link between establishment of codon-anticodon base-pairing and hydrolysis of eIF2-bound GTP. Genes Dev., 18, 3078–3093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Fekete, C.A., Mitchell, S.F., Cherkasova, V.A., Applefield, D., Algire, M.A., Maag, D., Saini, A.K., Lorsch, J.R. and Hinnebusch, A.G. (2007) N- and C-terminal residues of eIF1A have opposing effects on the fidelity of start codon selection. EMBO J., 26, 1602–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pestova, T.V. and Kolupaeva, V.G. (2002) The roles of individual eukaryotic translation initiation factors in ribosomal scanning and initiation codon selection. Genes Dev., 16, 2906–2922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Valasek, L., Nielsen, K.H., Zhang, F., Fekete, C.A. and Hinnebusch, A.G. (2004) Interactions of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 3 (eIF3) subunit NIP1/c with eIF1 and eIF5 promote preinitiation complex assembly and regulate start codon selection. Mol. Cell. Biol., 24, 9437–9455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Geoghegan, K.F., Hoth, L.R., Tan, D.H., Borzilleri, K.A., Withka, J.M. and Boyd, J.G. (2002) Cyclization of N-terminal S-carbamoylmethylcysteine causing loss of 17 Da from peptides and extra peaks in peptide maps. J. Proteome Res., 1, 181–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Peterson, A.C., Russell, J.D., Bailey, D.J., Westphall, M.S. and Coon, J.J. (2012) Parallel reaction monitoring for high resolution and high mass accuracy quantitative, targeted proteomics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics, 11, 1475–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hagerman, R.J., Coffey, S.M., Maselli, R., Soontarapornchai, K., Brunberg, J.A., Leehey, M.A., Zhang, L., Gane, L.W., Fenton-Farrell, G., Tassone, F. and Hagerman, P.J. (2007) Neuropathy as a presenting feature in fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A, 143A, 2256–2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Iwahashi, C.K., Yasui, D.H., An, H.J., Greco, C.M., Tassone, F., Nannen, K., Babineau, B., Lebrilla, C.B., Hagerman, R.J. and Hagerman, P.J. (2006) Protein composition of the intranuclear inclusions of FXTAS. Brain, 129, 256–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tassone, F., Hagerman, R.J., Garcia-Arocena, D., Khandjian, E.W., Greco, C.M. and Hagerman, P.J. (2004) Intranuclear inclusions in neural cells with premutation alleles in fragile X associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. J. Med. Genet., 41, e43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lange, P.F., Huesgen, P.F., Nguyen, K. and Overall, C.M. (2014) Annotating N termini for the human proteome project: N termini and Nalpha-acetylation status differentiate stable cleaved protein species from degradation remnants in the human erythrocyte proteome. J. Proteome Res., 13, 2028–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ree, R., Varland, S. and Arnesen, T. (2018) Spotlight on protein N-terminal acetylation. Exp. Mol. Med., 50, 1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Verkerk, A.J., deGraaff, E., De Boulle, K., Eichler, E.E., Konecki, D.S., Reyniers, E., Manca, A., Poustka, A., Willems, P.J., Nelson, D.L.et al. (1993) Alternative splicing in the fragile X gene FMR1. Hum. Mol. Genet., 2, 1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Na, C.H., Barbhuiya, M.A., Kim, M.S., Verbruggen, S., Eacker, S.M., Pletnikova, O., Troncoso, J.C., Halushka, M.K., Menschaert, G., Overall, C.M. and Pandey, A. (2018) Discovery of noncanonical translation initiation sites through mass spectrometric analysis of protein N termini. Genome Res., 28, 25–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Martinez, A., Traverso, J.A., Valot, B., Ferro, M., Espagne, C., Ephritikhine, G., Zivy, M., Giglione, C. and Meinnel, T. (2008) Extent of N-terminal modifications in cytosolic proteins from eukaryotes. Proteomics, 8, 2809–2831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Meinnel, T., Peynot, P. and Giglione, C. (2005) Processed N-termini of mature proteins in higher eukaryotes and their major contribution to dynamic proteomics. Biochimie, 87, 701–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Varland, S., Osberg, C. and Arnesen, T. (2015) N-terminal modifications of cellular proteins: The enzymes involved, their substrate specificities and biological effects. Proteomics, 15, 2385–2401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ventoso, I., Sanz, M.A., Molina, S., Berlanga, J.J., Carrasco, L. and Esteban, M. (2006) Translational resistance of late alphavirus mRNA to eIF2alpha phosphorylation: a strategy to overcome the antiviral effect of protein kinase PKR. Genes Dev., 20, 87–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sanz, M.A., Gonzalez A1 ela, E. and Carrasco, L. (2017) Translation of Sindbis Subgenomic mRNA is independent of EIF2, eIF2A and eIF2D. Sci. Rep., 7, 43876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Luna, R.E., Arthanari, H., Hiraishi, H., Nanda, J., Martin-Marcos, P., Markus, M.A., Akabayov, B., Milbradt, A.G., Luna, L.E., Seo, H.C.et al. (2012) The C-terminal domain of eukaryotic initiation factor 5 promotes start codon recognition by its dynamic interplay with eIF1 and eIF2beta. Cell Rep., 1, 689–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pisarev, A.V., Kolupaeva, V.G., Pisareva, V.P., Merrick, W.C., Hellen, C.U. and Pestova, T.V. (2006) Specific functional interactions of nucleotides at key −3 and +4 positions flanking the 65. initiation codon with components of the mammalian 48S translation initiation complex. Genes Dev., 20, 624–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Gao, F.B., Richter, J.D. and Cleveland, D.W. (2017) Rethinking Unconventional Translation in Neurodegeneration. Cell, 171, 994–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Malik, I., Kelley, C.P., Wang, E.T. and Todd, P.K. (2021) Molecular mechanisms underlying nucleotide repeat expansion disorders. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol., 22, 589–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tabet, R., Schaeffer, L., Freyermuth, F., Jambeau, M., Workman, M., Lee, C.Z., Lin, C.C., Jiang, J., Jansen-West, K., Abou-Hamdan, H.et al. (2018) CUG initiation and frameshifting enable production of dipeptide repeat proteins from ALS/FTD C9ORF72 transcripts. Nat. Commun., 9, 152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Zu, T., Guo, S., Bardhi, O., Ryskamp, D.A., Li, J., Khoramian Tusi, S., Engelbrecht, A., Klippel, K., Chakrabarty, P., Nguyen, L., Golde, T.E.et al. (2020) Metformin inhibits RAN translation through PKR pathway and mitigates disease in C9orf72 ALS/FTD mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 117, 18591–18599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Liang, H., He, S., Yang, J., Jia, X., Wang, P., Chen, X., Zhang, Z., Zou, X., McNutt, M.A., Shen, W.H. and Yin, Y. (2014) PTENalpha, a PTEN isoform translated through alternative initiation, regulates mitochondrial function and energy metabolism. Cell Metab., 19, 836–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Reid, D.W., Chen, Q., Tay, A.S., Shenolikar, S. and Nicchitta, C.V. (2014) The unfolded protein response triggers selective mRNA release from the endoplasmic reticulum. Cell, 158, 1362–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ivanov, I.P., Loughran, G., Sachs, M.S. and Atkins, J.F. (2010) Initiation context modulates autoregulation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 1 (eIF1). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 107, 18056–18060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Stewart, J.D., Cowan, J.L., Perry, L.S., Coldwell, M.J. and Proud, C.G. (2015) ABC50 mutants modify translation start codon selection. Biochem. J., 467, 217–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Bordeleau, M.E., Mori, A., Oberer, M., Lindqvist, L., Chard, L.S., Higa, T., Belsham, G.J., Wagner, G., Tanaka, J. and Pelletier, J. (2006) Functional characterization of IRESes by an inhibitor of the RNA helicase eIF4A. Nat. Chem. Biol., 2, 213–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Doers, M.E., Musser, M.T., Nichol, R., Berndt, E.R., Baker, M., Gomez, T.M., Zhang, S.C., Abbeduto, L. and Bhattacharyya, A. (2014) iPSC-derived forebrain neurons from FXS individuals show defects in initial neurite outgrowth. Stem Cells Dev., 23, 1777–1787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Garcia-Arocena, D., Yang, J.E., Brouwer, J.R., Tassone, F., Iwahashi, C., Berry-Kravis, E.M., Goetz, C.G., Sumis, A.M., Zhou, L., Nguyen, D.V.et al. (2010) Fibroblast phenotype in male carriers of FMR1 premutation alleles. Hum. Mol. Genet., 19, 299–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Todd, P.K., Oh, S.Y., Krans, A., Pandey, U.B., Di Prospero, N.A., Min, K.T., Taylor, J.P. and Paulson, H.L. (2010) Histone deacetylases suppress CGG repeat-induced neurodegeneration via transcriptional silencing in models of fragile X tremor ataxia syndrome. PLoS Genet., 6, e1001240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Singh, A.K., Khare, P., Obaid, A., Conlon, K.P., Basrur, V., DePinho, R.A. and Venuprasad, K. (2018) SUMOylation of ROR-gammat inhibits IL-17 expression and inflammation via HDAC2. Nat. Commun., 9, 4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Casado, M., Sierra, C., Batllori, M., Artuch, R. and Ormazabal, A. (2018) A targeted metabolomic procedure for amino acid analysis in different biological specimens by ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Metabolomics, 14, 76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.