Abstract

The recent study was designed to explore Dodonaea viscosa, Juniperus excelsa, Helianthemum lippii, and Euryops pinifolius using methanolic (MeOH) extract. Their subfractions were examined against urease, carbonic anhydrase II (CA-II), α-glucosidase enzymes, and free radicals scavenging significance based on local practices via standard methods. Significance potential against the urease enzyme was presented by ethyl acetate fraction (EtOAc) of D. viscosa with (IC50 = 125 ± 1.75 μg/mL), whereas the H. lippii (IC50 = 146 ± 1.39 μg/mL) in the EtOAc was found efficient to scavenge the free radicals. Besides, that appreciable capacity was observed by the J. excelsa, D. viscosa, J. excelsa, and E. pinifolius as compared to the standard acarbose (IC50 = 377.24 ± 1.14 μg/mL). Maximum significance was noticed in methanolic (MeOH) extract of J. excelsa and presented carbonic anhydrase CA-II (IC50 = 5.1 ± 0.20 μg/mL) inhibition as compared to the standard (acetazolamide). We are reporting, for the first time, the CA-II inhibition of all the selected medicinal plants and α-glucosidase, urease, and antioxidant activities of the E. pinifolius. Thus, further screening is needed to isolate the promising bioactive ingredients which act as an alternative remedy to scavenge the free radicals, antiulcer, and act as a potential source to develop new antidiabetic drugs for controlling postprandial blood sugar as well as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors.

1. Introduction

Phytomedicines are made up of medicinal plants and their chemical ingredients and have a key therapeutic role in various health-related complications, for instance, gastrointestinal infections, free radicals scavenging, and antidiabetic properties [1]. In this context, plant extracts are made up of a variety of chemical elements and are well-known for their wide range of clinical applications. They are derived from plants using both traditional and other modern approaches [2].

Urease enzymes play a leading role to catalyze the hydrolysis of urea, thus gaining substantial attention regarding human health and their life qualities [3–5]. It maintains optimum pH and treats the NH3 to balance its medium level due to which they own an incredible medical position [6, 7]. It is the main public health matter related to the bacterium H. pylori, which can endure in an acidic environment of the stomach having pH 2 range [6, 8]. The high prevalence of H. pylori in the human population indicates that such microbes have developed mechanisms for resistance against host defenses [8]. Marketed available urease drugs (phosphorodiamidate, hydroxamic acid derivatives, and imidazoles) are much more toxic with less efficacy rate and thus influenced by their limited clinical use [9, 10]. Thus, the quest for innovative urease inhibitors with enhanced stability and minimal toxicity is needed to improve the life quality of human beings and animals. Therefore, plant-based drugs are the alternative basis for having the ability to overcome the mentioned complications.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a common metabolic illness that has become a serious worldwide health issue. When DM is left untreated, it can harm the nerves, eyes, kidneys, and other organs. Increased urination, impaired vision, weariness, hunger, and thirst are among the symptoms of T2DM [11]. Controlling postprandial hyperglycemia by delaying carbohydrate digestion and absorption is one of the therapy options for T2DM. α-Glucosidase (EC 3.2.1.20) is an enzyme found on the small intestine's brush edge. Inhibition of the α-glucosidase can limit the digestion of carbohydrates resulting in declined postprandial blood sugar levels [12]. As a result, α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGIs) can be used as first-line therapy for T2DM [13–15].

Natural antioxidants can improve food quality including color, taste, flavor, and stability and also act as standardized nutrients (nutraceuticals) to end up the attack of free radicals in biological systems [16, 17], that might deliver additional health benefits to consumers [18, 19] and reduce the risk of disorders caused by free radicals [20]. Recently, considerable attention focused on the use of natural antioxidants to defend the human body against brain tissues and neurological disorders associated with free radical damage [20, 21]. This research is focused on searching for new sources of natural antioxidants and urease inhibitors that can be used directly or in combination with other official drugs as a lead compound for drug discovery.

Carbonic anhydrase (CA) is a metalloenzyme that contains zinc and is mainly used to catalyze CO2 hydration into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions [22]. The CA inhibitors control the enzymatic actions and prevent bicarbonate reabsorption which leads to numerous adverse effects such as potassium and bicarbonate retention in the human urine and decreased sodium absorption as a diuretic [23]. The intake of synthetic drugs for longer use to release this complication might be harmful. Therefore, searching for plant-based alternative remedies can be useful to cope with these disorders [24].

Juniperus excelsa M. Bieb (JE, Cupressaceae) is used mainly for lowering blood pressure [25], jaundice, bronchitis, tuberculosis, common cold [26], diabetes, stomachache, grazing, and wood harvesting [27]. Literature surveys documented its positive effects in treating colds, cough, dysmenorrheal, persuading menses, and expelling fetuses [28, 29]. Dodonaea viscosa Linn (DV, Sapindaceae) was reported to possess antiviral, anti-inflammatory, laxative, spasmolytic, antimicrobial, hypotensive agents [30], smooth muscle relaxant, anesthetic, throat infection, malaria, and antiulcerogenic [31, 32]. Traditionally, it is used to treat many illnesses like malaria, cold, aches, fever, toothaches, rheumatism, headaches, ulcers, diarrhea, dysmenorrhea, irregular menstruation, and constipation [33].

Helianthemum lippii (HL) belongs to the genus Helianthemum, which is a widely distributed and most taxonomically complex genus of the Family Cistaceae. Alsabri et al. [34] reported anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of H. lippii against carrageenan-induced paw edema and hotplate-induced pain in rats. Previous studies showed that the plant is a rich source of polyphenols and flavonoids [35, 36] with antioxidant, antiulcer, and antimicrobial [37], as well as cytotoxic [38]. Euryops pinifolius A. Rich belongs to the genus Euryops (family: Asteraceae) [39], mostly cultivated in southern Africa, with a few species in other parts of Africa and on the Arabian Peninsula [28]. The local uses of E. pinifolius are least known, however, in some places of the Arabian Peninsula (Yemen, Oman, and Saudi Arabia), are used to wound healing [40].

To devise innovative plant-derived drugs, four important medicinal plants were collected from Al Jabal Al Akhdar (Northern Oman) and evaluated for antioxidant and enzyme inhibition activities. To the best knowledge, this is the first report on the enzyme inhibition study of these plants. In addition, we are also reporting the antioxidant activity of H. lippii and E. pinifolius for the first time.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Collection and Identification of the Medicinal Plants

Aerial parts of the plant species ,viz., J. excelsa (3.5 Kg), H. lippii (3.5 Kg), E. pinifolius (4.0 Kg), and D. viscose (5.5 Kg), were collected from Al Jabal Al Akhdar, Oman, identified by a plant taxonomist (Dr. Syed Abdullah Gillani) at the Department of Biological Sciences and Chemistry, University of Nizwa, Oman. After documentation, voucher specimens (HL-01/2012, EP-02/2012, DV-03/2012, and JE-04/2012) were kept at the herbarium of Natural and Medical Sciences Research Center, University of Nizwa, Oman, for further processing.

2.2. Extraction and Fractionation

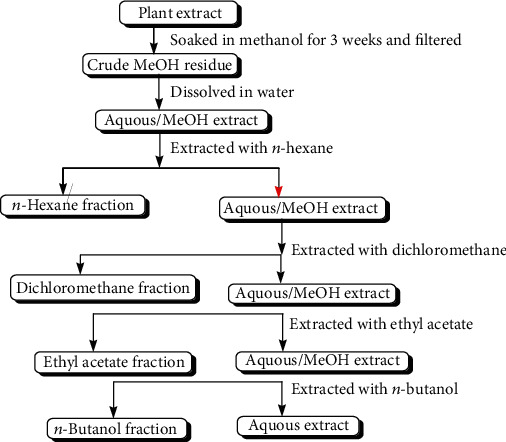

The whole aerial parts of the Dodonaea viscosa were dried, chopped, and soaked in methanol at room temperature for 15 days three times as reported earlier by Shah et al. [16]. Evaporation of the MeOH in vacuo at 45°C yielded a crude methanol extract, which after suspension in water was successively fractionated into n-hexane, dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), ethyl acetate (EtOAc), butanol (n-BuOH), and aqueous (H2O) (Figure 1). The same procedure was used for the extraction and fractionation of other medicinal plants. The details of quantity of crude extracts and the different fractions of the selected plants are given in Table 1. The crude extracts and their fractions were subjected to biological screening to determine their potential effect.

Figure 1.

General fractionation scheme for the solvent-solvent extraction of medicinal plants.

Table 1.

Crude extracts and fractions of the selected medicinal plants.

| Plant's name | Crude (g) | Fractions (g) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MeOH | n-hexane | CH2Cl2 | EtOAc | n-BuOH | H2O | |

| D. viscosa | 135 | 16 | 45 | 28 | 14 | 28 |

| J. excelsa | 115 | 11 | 23 | 20 | 24 | 35 |

| H. lippii | 95 | 12 | 18 | 25 | 12 | 28 |

| E. pinifolius | 90 | 13 | 19 | 21 | 18 | 17 |

2.3. Antioxidant Activity

The antioxidant bioassay of the crude extracts and subfractions of the selected plants was evaluated using α, α-diphenyl-β-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) assay [41]. About 100 μL of methanol was mixed with 150 μL of DPPH solution as a negative control. For the sample, about 150 μL of DPPH was added with 100 μL of three concentrations of extract (100, 500, and 1000 μg/mL). The absorbance was taken at 517 nm by spectrophotometer. All the results were compared to a control containing 50 μL of methanol. The positive control used was ascorbic acid (Table 1). Each test was repeated three times, and % inhibition was calculated as:

| (1) |

2.4. Urease Enzyme Inhibition

Urease enzyme inhibition assay was performed using available literature [42, 43]. About 25 μL solution of Jack bean urease was mixed with 50 μL urea dissolved in phosphate buffer (pH 8.20) with 20 μL of three concentrations (100, 500, and 1000 μg/mL) of different extract fractions and then incubated at 37°C for 15 min. Then, 50 μL of solution B (phenol reagent (1% w/w phenol) own expect 3 mg in 30 mL + 0.005% w/v sodium nitroprusside) and 70 μL of solution A (alkali reagent (0.5% w/v NaOH +1% active chloride NaOCl)) were added and then incubated again for 15 min. Thiourea was used as a positive (standard) control, while methanol was used as a negative control (Table 2). The absorbance was recorded at 630 nm with a total volume of 215 μL.

| (2) |

Table 2.

Antioxidant activity (%) of four Omani medicinal plants.

| Plant Species | Fractions | Antioxidant activity IC50 ± S.E.M (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|

| J. excelsa | n-Hexane | Nd |

| DCM | Nd | |

| EtOAc | 402 ± 2.15 | |

| n-BuOH | 428 ± 1.54 | |

| MeOH | Nd | |

| Aqueous | Nd | |

| E. pinifolius | n-Hexane | Nd |

| DCM | Nd | |

| EtOAc | 378 ± 1.56 | |

| n-BuOH | 904 ± 2.68 | |

| MeOH | Nd | |

| Aqueous | Nd | |

| H. lippii | n-Hexane | 788 ± 2.68 |

| DCM | 658 ± 1.54 | |

| EtOAc | 146 ± 1.39 | |

| n-BuOH | 561 ± 1.34 | |

| MeOH | 368 ± 2.18 | |

| Aqueous | 460 ± 1.21 | |

| D. viscosa | n-Hexane | Nd |

| DCM | Nd | |

| EtOAc | 386 ± 1.65 | |

| n-BuOH | 467 ± 1.84 | |

| MeOH | 914.±2.61 | |

| Aqueous | Nd | |

| Ascorbic acid | 6.25 ± 0.56 |

Ascorbic acid∗= μM; DCM: dichloromethane; EtOAc: ethyl acetate; BuOH: n-butanol; MeOH: methanol; SEM: standard error mean; Nd: not determined (Conc. = 1 mg/mL).

2.5. α-Glucosidase Assay

All the twenty-four samples of crude extract and subfractions were evaluated in vitro against α-glucosidase enzyme (E.C.3.2.1.20) as described earlier by Shah et al. [11], by using (50 mM) phosphate buffer of pH (6.8). The enzyme was properly dissolved in the phosphate buffer; 1 U/2 mL, 20 μL/well of the enzyme, and 135 μL/well phosphate buffer was used as reaction buffer, 20 μL/well of the tested samples were solubilized in DMSO (0.5 μg/mL), in 96-wells plates incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. After the incubation period, the substrate para nitro phenyl-D-glucopyranoside was added at a concentration of 0.7 mM, and the change in absorbance was measured at 400 nm for 30 minutes. The positive control used was acarbose, and DMSO was used as negative control.

| (3) |

2.6. Carbonic Anhydrase II Inhibition Assay

The total reaction mixture comprised 20 μL (0.5 mmol/well) of test compounds (10% DMSO in total), and then add HEPES–Tris buffer 140 μL (20 mmol, pH =7.4), 20 μL of purified bovine erythrocyte CA-II (1 mg/mL, 0.1 units/well) prepared in buffer, and finally substrate 4-nitrophenyl acetate (4-NPA, 0.7 mmol) 20 μL to attain final volume 200 μL/well [44, 45]. An enzyme (EC 4.2.1.1, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) along with the tested compounds was incubated for 15 min in a 96-well plate. Then, the reaction was started with the addition of 20 μL of the substrate (4-nitrophenyl acetate) and continuously monitored the rate (velocities) of product formation for 30 min with the intervals of 1 min, at 25°C by using a microplate reader (Bio-Rad, Molecular Devices, CA, USA). Acetazolamide and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively.

| (4) |

2.7. Statistical Analysis

The SoftMax Pro package and Excel were utilized.

The given formula below was used to calculate percent inhibition.

| (5) |

EZ-FIT (Perrella Scientific, Inc., USA) was used for IC50 calculations of all tested samples. To overcome on the expected errors, all experiments were performed in triplicate, and variations in the results are reported in standard error of mean values (SEM).

| (6) |

3. Result and Discussion

Herbs have been used as a source of medicine since the dawn of human civilization, and they continue to play an important role in clinical use and quality control for a variety of health issues [46].

3.1. Antioxidant Capability

The antioxidant significance of the selected plants is determined to evaluate the free radical scavenger capacities of the selected plant species utilizing ascorbic acid as a standard inhibitor as presented in Table 2. In recent years, increasing attention has been paid to antioxidant compounds (flavones, anthocyanin, flavonoids, catechin, isoflavones, and other phenolics) derived from plants due to their valuable role in reducing various disorders such as immune system, brain dysfunction, heart disease, decline, cardiovascular disease, aging, and cancer [47]. The free radicals produced due to human metabolism affect the cellular membrane to overcome these complications [47]. The investigation reveals that among the screened four plant species, H. lippii fractions offered a significant ability to scavenge the free radicals and act as an antioxidant agent. The EtOAc fraction of H. lippii exhibited the highest potential to act as an antioxidant agent with IC50 of 146 ± 1.39 μg/mL followed by the MeOH (IC50 = 368 ± 2.18 μg/mL) and aqueous extract (460 ± 1.21 μg/mL), respectively. This significance is attributed due to the presence of an affluent basis of polyphenolic constituents as documented by Benabdelaziz et al. [48]. Alali et al. [49] investigated H. lippii from Jordan and reported methanol (IC50 = 176.1 μmol TE g−1dry weight) and aqueous (IC50 = 176.1 and 274.2 μmol TE g−1dry weight) extracts in comparison to the standard via ABTS assay. However, in the current study, the geographical location, collection, habitat, harvesting season, screening approach, and standard used are different from earlier studies. Therefore, our finding reveals that the H. lippii has a significant ability to neutralize the free radicals. Belyagoubi et al. [36] collected H. lippii from Algeria as a plant habitat influenced the quality and quantity of bioactive compounds responsible for promising pharmacological potentials [50]. However, moderate capability was observed in the n-hexane and CH2Cl2 fractions (Table 2). In the case of E. pinifolius, the EtOAc fraction displayed significance inhibition (IC50 = 378 ± 1.56 μg/mL) followed by the n-BuOH fraction (IC50 = 904 ± 2.64 μg/mL). Moreover, the EtOAc fraction of D. viscosa also produced promising findings with (IC50 = 386 ± 1.65 μg/mL) ensued by the n-BuOH (IC50 = 467 ± 1.84 μg/mL), while normal activity was examined by the MeOH extract (Table 2). The current findings consented to the data stated for some Yemeni traditional medicinal plants by Mothana et al. [51] that D. viscosa was one of the most active plants that showed promising antioxidant activity. In addition to that, the current outcome also supports the results reported by Singh et al. [52] for Rhus aucheri as the understudy plant was collected from Oman. Recently, Muhammad et al. [53] isolated some flavonoids from the EtOAc fraction of D. viscosa showed higher antioxidant activity further stringent our findings. It was also observed that the free radicals scavenging significance of some medicinal plants from Iran was dissimilar from our recorded data as described by Boroomand et al. [54] due to the variation of their habitat, climatic, topographic, and edaphic factors influenced the content and quality of the metabolites accountable to act as an antioxidant agent. The data obtained from these in vitro models demonstrated the strong antioxidant potential of EtOAc and n-BuOH fractions of the selected medicinal plants, which might be a concern with its high medicinal and pharmaceutical use as a functional food in the treatment of different diseases.

3.2. Antiulcer Potential

The urease enzyme inhibitory activity of crude extracts/fractions of the plants was determined using a concentration of 1.0 mg/mL. Ethyl acetate fraction of D. viscosa exhibited significantly promising urease inhibition (IC50 = 125 ± 1.75 μg/mL), followed by n-hexane (IC50 = 142 ± 2.00 μ/mL) and n-BuOH (IC50 = 410 ± 2.50 μg/mL) fractions. The data of crude extract and fractions of J. excelsa revealed that only the EtOAc fraction exhibited significant inhibition (IC50 = 173 ± 2.50 μg/mL) as compared to other fractions. In the case of H. lippii, the EtOAc fraction showed significantly strong inhibition (IC50 = 257 ± 1.25 μg/mL), followed by n-BuOH (IC50 = 435 ± 2.75 μg/mL), while MeOH and aqueous fractions of the same plant did not show activity (Table 3). The EtOAc fraction of E. pinifolius attributed promising inhibition (IC50 = 390 ± 2.50 μg/mL), followed by the n-BuOH (IC50 = 430 ± 2.25 μg/mL), while other fractions did not show urease inhibition (Table 3).

Table 3.

α-Glucosidase CA-II and urease activities of the selected medicinal plants.

| Sample code | Fractions |

α-Glucosidase IC50 ± SEM (μg/mL) |

Urease IC50 ± SEM (μg/mL) |

CA-II IC50 ± SEM (μg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D. viscosa | EtOAc | 5.99 ± 0.20 | 125 ± 1.75 | 27.5 ± 3.12 |

| DCM | 10.86 ± 0.17 | 416 ± 1.50 | NA | |

| Aqueous | 5.34 ± 0.14 | NA | NA | |

| MeOH | 3.18 ± 0.10 | NA | 50.4 ± 2.03 | |

| n-Hexane | 2.04 ± 0.06 | 142 ± 2.00 | NA | |

| n-BuOH | 1.30 ± 0.05 | 410 ± 2.50 | NA | |

| J. excelsa | EtOAc | 1.31 ± 0.02 | 173 ± 2.50 | 38.4 ± 2.52 |

| DCM | 3.65 ± 0.12 | NA | 46.3 ± 1.95 | |

| Aqueous | 2.48 ± 0.13 | NA | 51.3 ± 1.35 | |

| MeOH | 3.11 ± 0.14 | NA | 5.1 ± 0.20 | |

| n-Hexane | 2.78 ± 0.11 | NA | NA | |

| n-BuOH | 2.05 ± 0.08 | NA | 66.8 ± 3.19 | |

| E. pinifolius | EtOAc | 7.85 ± 0.16 | 390 ± 2.50 | 47.0 ± 3.99 |

| DCM | 16.72 ± 0.15 | NA | 45.4 ± 2.08 | |

| Aqueous | N/A | NA | 98.2 ± 4.84 | |

| MeOH | 2.86 ± 0.03 | NA | NA | |

| n-Hexane | N/A | NA | NA | |

| n-BuOH | 22.12 ± 0.15 | 430 ± 2.25 | 41.5 ± 0.82 | |

| H. lippii | EtOAc | 5.12 ± 0.18 | 257 ± 1.25 | 35.6 ± 1.32 |

| DCM | 5.73 ± 0.21 | NA | NA | |

| Aqueous | 5.47 ± 0.13 | NA | 9.9 ± 0.35 | |

| MeOH | 10.48 ± 0.26 | NA | NA | |

| n-Hexane | 5.73 ± 0.21 | NA | 18.8 ± 3.13 | |

| n-BuOH | 6.45 ± 0.11 | 435 ± 2.75 | 59.4 ± 2.33 | |

| Acarbose | 608.21 ± 1.74 | |||

| Thiourea | 1.58 ± 0.95 | |||

| Acetazolamide | 4.04 ± 1.63 |

DCM: dichloromethane; EtOAc: ethyl acetate; BuOH: butanol; MeOH: methanol; N/A (nonactive); concentration =0.5 mg/mL; SEM: standard error mean; ND: not determined.

These findings provide crucial information about the biologically active constituents present in medicinal plants truly responsible for the inhibition of the urease enzyme. Thus, our finding matched with the data reported by Rauf et al. [55] for Diospyros lotus roots and in favor of the outcomes presented by Maherina et al. [56] as the use of the same approach to determine the urease significance in the medicinal plants. Moreover, our current findings do not agree with the data reported by Tahseen et al. [57] due to their variability in their habitat. In the future, bioassay-guided isolation of these secondary metabolites might be exciting and interesting to know the chemical constituents responsible for inhibition and to understand their basic mechanism against these enzymes.

3.3. Antidiabetic Significance

Crude extract and subfractions of the four plant species (D. viscosa, J. excelsa, H. lippii, and E. pinifolius) were tested to analyze their antidiabetic potential by targeting the key carbohydrate digestive enzyme α-glucosidase. Furthermore, the aqueous and n-hexane fractions of J. excelsa showed below 50% inhibitory activity and were found to be inactive. While other samples displayed several folds of potent inhibitory potential in the range of 1.30-20.75 μg/mL, compared with acarbose (IC50 = 377.24 ± 1.14 μg/mL). Moreover, the n-BuOH and n-hexane fractions of D. viscosa exhibited significant inhibitory activity with IC50 (1.30 ± 0.05 and 2.04 ± 0.06 μg/mL), respectively. Thus, our data is supported by the literature explained by Assefa et al. [58] and VVM et al. [59]. It might be due to the presence of active chemical ingredients having the ability to cure diabetes. On the other hand, the EtOAc, DCM, aqueous, MeOH, n-hexane, and n-BuOH fractions of J. excelsa exhibited potent α-glucosidase inhibitory potential with IC50 (1.31 ± 0.02, 3.65 ± 0.12, 2.48 ± 0.13, 3.11 ± 0.14, 2.78 ± 0.11, and 2.05 ± 0.08 μg/mL), respectively. Thus, our current screening consented to the findings of Bhatia et al. [60], which depicted a little variation in outcomes reported by Sancheti et al. [61] and Gok et al. [62]. Due to differences in the chemical ingredients influenced by environmental factors and the solvents and methods used in our studies. in addition to that, the E. pinifolius offered variations in the anti-α-glucosidase potential. For instance, the MeOH extract was found to be the most potent and displayed IC50 = 2.86 ± 0.03 μg/mL. A slight decrease in the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was observed in the other fraction samples, such as EtOAc having IC50 = 7.85 ± 0.16 μg/mL. Likewise, a slightly further decline in the antidiabetic capability was observed, in the DCM and n-BuOH fractions depicted (IC50 = 16.72 ± 0.15 μg/mL and 22.12 ± 0.15 μg/mL), respectively. So, these outcomes also reflect that our data agrees with the findings of Khatib et al. [63].

Furthermore, our investigation exhibited a little variation as compared to the data stated by Ibrahim et al. [64] as mentioned previously that the habitat variation can also be led to variability among the chemical ingredients among the different and same plant species. Interestingly all the fractions of H. lippii displayed several fold potent inhibitory activities with almost the same potency comprises of EtOAc, DCM, aqueous, n-hexane, and BuOH with IC50 of 5.12 ± 0.18, 5.73 ± 0.21, 5.47 ± 0.13, 5.73 ± 0.21, and 6.45 ± 0.11 μg/mL, respectively, as compared to MeOH extract (IC50 = 10.48 ± 0.26 μg/mL). Our current study consented to the literature described by Zarei et al. [65]. However, our current result does not agree with the findings of Rungprom et al. [66]. The similarity of the antidiabetic significance presented by the medicinal plants might be due to the presence of the phenols and flavonoids. As we know in the current era plant extractions are becoming increasingly popular in medicinal therapies, and they are an alternative and valuable herbal medicinal medicine because of their broad usage and lower adverse effects, the current results insight into the crucial therapeutic importance of the D. viscosa, J. excelsa, H. lippii, and E. pinifolius in their crude and subfractions. Hence, these promising findings might be used as a therapeutic approach for the management of type 2 diabetes (T2DM) displayed in Table 3.

3.4. Carbonic Anhydrase II Significance

The selected plants are profiled for their carbonic anhydrase activity as shown in Table 3. Among the subfractions, EtOAc fraction of the D. viscosa presented significanse activity with IC50 of 27.5 ± 3.12 ± µg/mL trail by the MeOH extract IC50 = 50.4 ± 2.03 µg/mL, while other subfractions were found inactive. The D. viscosa contains phenols and polyphenols having the capability to act as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors; thus, our findings agree with the data stated by Karioti et al. [67]. The current finding presented that our data do not match with the data recorded by Rudenko et al. [68] because environmental stress influences the quality and quantity of bioactive ingredients responsible for numerous biological activities. Furthermore, the MeOH extract of J. excelsa followed by the EtOAc fraction of J. excelsa displayed significant potential an IC50 = 5.1 ± 0.20 and IC50 = 38.4 ± 2.52 μg/mL significance in comparison to other tested fractions. The n-BuOH fraction of E. pinifolius presented appreciable significance having IC50 = 41.5 ± 0.82 μg/mL, followed by the DCM fraction with IC50 = 45.4 ± 2.08, and the EtOAc fraction exhibited an IC50 = 47.0 ± 3.99 μg/mL potential, whereas the MeOH and n-hexane extract were found inactive for carbonic anhydrase activity. The H. lippii fractions also displayed appreciable potential except for the DCM and MeOH extracts, while aqueous extract was most potent presented IC50 = 9.9 ± 0.35 μg/mL, proceeded by the n-hexane with IC50 = 18.8 ± 3.13 μg/mL and IC50 = 35.6 ± 1.32 μg/mL in comparison to the standard acetazolamide having an IC50 = 4.04 ± 1.63 μg/mL. The current results also match up with the outcomes of Aydin et al. [69] for Satureja cuneifolia and dodoneine by Carreyre et al. [70] which was found effective for the carbonic anhydrase activity. However, the study reported for the bioactive ingredient dodoneine by Carreyre et al. [70] was significant as compared to our current findings because might be bioactive compounds are responsible compounds as compared to our selected plants and tested fractions

4. Conclusion

In conclusion, the selected medicinal plants (D. viscosa, J. excelsa, H. lippii, and E. pinifolius) possess significance anti-ulcer, antioxidant, antidiabetic and carbonic anhydrase-II inhibition and can be considered as essential source of bioactive ingredients. Additionally, up to now, no such scientific data were reported for the enzyme inhibition potential, whereas the two plant species were reported for the first time in a recent study. Therefore, it could be contended that the medicinal plants have significant potential to serve as an antioxidant and own enzyme inhibitory attributes. However, further investigations are considered necessary for the isolation and identification of the chemical ingredients accountable for the antioxidant and enzymatic significance of the selected plants.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the University of Nizwa, Oman, for the generous support of this work. The authors are also grateful to the Oman Research Council (TRC) through the research grant program (BFP/RGP/CBS/21/002).

Data Availability

All datasets on which the conclusion of the manuscript relies are presented in the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding this manuscript.

References

- 1.Mosquera O. M., Correra Y. M., Niño J. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts from Colombian flora. Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia . 2009;19(2a):382–387. doi: 10.1590/S0102-695X2009000300008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goyal A., Sharma A., Kaur J., et al. Bioactive-based cosmeceuticals: An update on emerging trends. Molecules . 2022;27(3):p. 828. doi: 10.3390/molecules27030828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai S., Bharti P., Seasotiya L., Malik A., Dalal S. In vitro screening and evaluation of some Indian medicinal plants for their potential to inhibit Jack bean and bacterial ureases causing urinary infections. Pharmaceutical Biology . 2015;53(3):326–333. doi: 10.3109/13880209.2014.918158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krajewska B., Ureases I. Ureases I. Functional, catalytic and kinetic properties: A review. Journal of Molecular Catalysis B: Enzymatic . 2009;59(1-3):9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.molcatb.2009.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yathindra N. Structure of an enzyme revealed 80 years after it was crystallized–differential functional behaviour of plant and microbial ureases uncovered. Current Science . 2010;99(5):566–568. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maroney M. J., Ciurli S. Nonredox nickel enzymes. Chemical Reviews . 2014;114(8):4206–4228. doi: 10.1021/cr4004488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boer J. L., Mulrooney S. B., Hausinger R. P. Nickel-dependent metalloenzymes. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics . 2014;544:142–152. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2013.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Algood H. M. S., Cover T. L. Helicobacter pylori persistence: an overview of interactions between H. pylori and host immune defenses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews . 2006;19(4):597–613. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00006-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Azizian H., Nabati F., Sharifi A., Siavoshi F., Mahdavi M., Amanlou M. Large-scale virtual screening for the identification of new Helicobacter pylori urease inhibitor scaffolds. Journal of Molecular Modeling . 2012;18(7):2917–2927. doi: 10.1007/s00894-011-1310-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ibrar A., Khan I., Abbas N. Structurally diversified heterocycles and related privileged scaffolds as potential urease inhibitors: a brief overview. Archiv der Pharmazie . 2013;346(6):423–446. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201300041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shah M., Murad W., Ur Rehman N., et al. GC-MS analysis and biomedical therapy of oil from n-hexane fraction of Scutellaria edelbergii Rech. f.: in vitro, in vivo, and in silico approach. Molecules . 2021;26(24):p. 7676. doi: 10.3390/molecules26247676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shah M., Rahman H., Khan A., et al. Identification of α-glucosidase inhibitors from Scutellaria edelbergii: ESI-LC-MS and computational approach. Molecules . 2022;27(4):p. 1322. doi: 10.3390/molecules27041322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wali S., Ullah S., Khan M. A., Hussain S., Shaikh M., Choudhary M. I. Synthesis of new clioquinol derivatives as potent α-glucosidase inhibitors; molecular docking, kinetic and structure-activity relationship studies. Bioorganic Chemistry . 2022;119:p. 105506. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2021.105506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ullah S., Mirza S., Salar U., et al. 2-Mercapto benzothiazole derivatives: As potential leads for the diabetic management. Medicinal Chemistry . 2020;16(6):826–840. doi: 10.2174/1573406415666190612153150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaffery S. M. F., Khan M. A., Ullah S., Choudhary M. I., Basha F. Z. Synthesis of new valinol-derived sultam triazoles as α-glucosidase inhibitors. ChemistrySelect . 2021;6(37):9780–9786. doi: 10.1002/slct.202102119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah M., Murad W., Rehman N. U., et al. Biomedical applications of Scutellaria edelbergii Rech. f.: in vitro and in vivo approach. Molecules . 2021;26(12):p. 3740. doi: 10.3390/molecules26123740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Akhtar M. F., Saleem A., Hamid I., et al. Contemporary uses of old folks: the immunomodulatory and toxic potential of fenbufen. Cellular and Molecular Biology . 2022;67(5):27–37. doi: 10.14715/cmb/2021.67.5.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bariş Ö., Güllüce M., Şahin F., et al. Biological activities of the essential oil and methanol extract of Achillea biebersteinii Afan (Asteraceae) Turkish Journal of Biology . 2006;30(2):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saleem A., Ahotupa M., Pihlaja K. Total phenolics concentration and antioxidant potential of extracts of medicinal plants of Pakistan. Zeitschrift für Naturforschung. Section C . 2001;56(11-12):973–978. doi: 10.1515/znc-2001-11-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kabir M. T., Rahman M. H., Shah M., et al. Therapeutic promise of carotenoids as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents in neurodegenerative disorders. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy . 2022;146:p. 112610. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2021.112610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meena H., Pandey H. K., Pandey P., Arya M. C., Ahmed Z. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of two important memory enhancing medicinal plants Baccopa monnieri and Centella asiatica. Indian Journal of Pharmacology . 2012;44(1):114–117. doi: 10.4103/0253-7613.91880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whittington D. A., Grubb J. H., Waheed A., Shah G. N., Sly W. S., Christianson D. W. Expression, Assay, and Structure of the Extracellular Domain of Murine Carbonic Anhydrase XIV. The Journal of Biological Chemistry . 2004;279(8):7223–7228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310809200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulcin I., Beydemir S. Phenolic compounds as antioxidants: carbonic anhydrase isoenzymes inhibitors. Mini Reviews in Medicinal Chemistry . 2013;13(3):408–430. doi: 10.2174/138955713804999874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tiwari A., Kumar P., Singh S., Ansari S. Carbonic anhydrase in relation to higher plants. Photosynthetica . 2005;43(1):1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11099-005-1011-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almaarri K., Alamir L., Junaid Y., Xie D.-Y. Volatile compounds from leaf extracts of Juniperus excelsa growing in Syria via gas chromatography mass spectrometry. Analytical Methods . 2010;2(6):673–677. doi: 10.1039/b9ay00256a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weli A. M., Al-Hinai S. R., Hossain M. M., Al-Sabahi J. N. Composition of essential oil of Omani Juniperus excelsa fruit and antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Journal of Taibah University for Science . 2014;8(3):225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jtusci.2014.04.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schlecht E., Dickhoefer U., Gumpertsberger E., Buerkert A. Grazing itineraries and forage selection of goats in the Al Jabal al Akhdar mountain range of northern Oman. Journal of Arid Environments . 2009;73(3):355–363. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hussain J., Rehman N. U., Al-Harrasi A., Ali L., Khan A. L., Albroumi M. A. Essential oil composition and nutrient analysis of selected medicinal plants in Sultanate of Oman. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Disease . 2013;3(6):421–428. doi: 10.1016/S2222-1808(13)60095-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan M., Khan A. U., Rehman N. U., Zafar M. A., Hazrat A., Gilani A. H. Cardiovascular effects of Juniperus excelsa are mediated through multiple pathways. Clinical and Experimental Hypertension . 2012;34(3):209–216. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2011.631651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan A. Z., Mohammad A., Iqbal Z., et al. Molecular docking of viscosine as a new lipoxygenase inhibitor isolated from Dodonaea viscosa. Bangladesh Journal of Pharmacology . 2012;8(1):36–39. doi: 10.3329/bjp.v8i1.13088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muhammad A., Anis I., Khan A., Marasini B. P., Choudhary M. I., Shah M. R. Biologically active C-alkylated flavonoids from Dodonaea viscosa. Archives of Pharmacal Research . 2012;35(3):431–436. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0305-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rani M. S., Pippalla R. S., Mohan K. Dodonaea viscosa Linn.-an overview. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research and Health Care . 2009;1(1):97–112. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lawal D., Yunusa I. Dodonea Viscosa Linn: its medicinal, pharmacological and phytochemical properties. International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies . 2013;2(4):476–482. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alsabri S. G., Zetrini A., Fitouri S., Hermann A. Screening of analgesic and anti-inflammatory activities for two Libyan medicinal plants: Helianthemum lippii and Launaea residifolia. Journal of Chemical and Pharmaceutical Research . 2012;4(9):4201–4205. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Atef C., Anouar F., El-Hadda A., Azzedine C. Phytochemicals study, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Helianthemum lippii (L.) pers. in different stages of growth (somatic, flowering and fruiting) World Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2015;4(11):338–349. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Belyagoubi-Benhammou N., Belyagoubi L., Bekkara F. A. Phenolic contents and antioxidant activities in vitro of some selected Algerian plants. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research: Planta Medica . 2014;8(40):1198–1207. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Alsabri S. G., Rmeli N. B., Zetrini A. A., et al. Phytochemical, anti-oxidant, anti-microbial, anti-inflammatory and anti-ulcer properties of Helianthemum lippii. Journal of Pharmacognosy and Phytochemistry . 2013;2(2) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bensaber S. M., Mrema I. A., Jaeda M. I., Gbaj A. M. Cytotoxic activity of Helianthemum lippii. Libyan Journal of Medicine Research . 2014;8:92–94. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nordenstam B., Clark V., Devos N., Barker N. Two new species of _Euryops_ (Asteraceae: Senecioneae) from the Sneeuberg, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Botany . 2009;75(1):145–152. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2008.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller A. G., Morris M. Ethnoflora of the Soqotra Archipelago . Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hussain J., Rehman N. U., Khan A. L., et al. Phytochemical and biological assessment of medicinally important plant Ochradenus arabicus. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2014;46(6):2027–2034. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rehman N. U., Mabood F., Khan A. L., et al. Evaluation of biological potential and physicochemical properties of Acridocarpus orientalis (Malpighiaceae) Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2019;51(3):1099–1106. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rehman N. U., Khan A., Al-Harrasi A., et al. Natural urease inhibitors from Aloe vera resin and Lycium shawii and their structural-activity relationship and molecular docking study. Bioorganic Chemistry . 2019;88:p. 102955. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2019.102955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rafiq K., Khan M., Muhammed N., et al. New amino acid clubbed Schiff bases inhibit carbonic anhydrase II, α-glucosidase, and urease enzymes: in silico and in vitro. Medicinal Chemistry Research . 2021;30(3):712–728. doi: 10.1007/s00044-020-02696-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Avula S. K., Rehman N. U., Khan M., et al. New synthetic 1H-1, 2, 3-triazole derivatives of 3-O-acetyl-β-boswellic acid and 3-O-acetyl-11-keto-β-boswellic acid from Boswellia sacra inhibit carbonic anhydrase II in vitro. Medicinal Chemistry Research . 2021;30(6):1185–1198. doi: 10.1007/s00044-021-02723-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chamkhi I., Hnini M., Aurag J. Conventional medicinal uses, phytoconstituents, and biological activities of Euphorbia officinarum L.: a systematic review. Advances in Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences . 2022;2022:9. doi: 10.1155/2022/9971085.9971085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haddad M. A., al-Dalain S. Y., al-Tabbal J. A., et al. In vitro antioxidant activity, macronutrients and heavy metals analysis of maize (zea mays l.) leaves grown at different levels of cattle manure amended soil in Jordan valley. Pakistan Journal of Botany . 2019;51(3):933–940. doi: 10.30848/PJB2019-3(12). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benabdelaziz I., Marcourt L., Benkhaled M., Wolfender J. L., Haba H. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities and polyphenolic constituents of Helianthemum sessiliflorum Pers. Natural Product Research . 2017;31(6):686–690. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1209669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alali F. Q., Tawaha K., El-Elimat T., et al. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of aqueous and methanolic extracts of Jordanian plants: an ICBG project. Natural Product Research . 2007;21(12):1121–1131. doi: 10.1080/14786410701590285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li Y., Kong D., Fu Y., Sussman M. R., Wu H. The effect of developmental and environmental factors on secondary metabolites in medicinal plants. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry . 2020;148:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2020.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mothana R. A., Abdo S. A., Hasson S., Althawab F., Alaghbari S. A., Lindequist U. Antimicrobial, antioxidant and cytotoxic activities and phytochemical screening of some Yemeni medicinal plants. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2010;7:330. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Singh V., Al-Malki F., Ali M. S., et al. Rhus aucheri Boiss, an Omani herbal medicine: identification and in-vitro antioxidant and antibacterial potentials of its leaves' extracts. Beni-Suef University Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences . 2016;5(4):334–339. doi: 10.1016/j.bjbas.2016.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muhammad A., Tel-Cayan G., Öztürk M., et al. Biologically active flavonoids from Dodonaea viscosa and their structure–activity relationships. Industrial Crops and Products . 2015;78:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boroomand N., Sadat-Hosseini M., Moghbeli M., Farajpour M. Phytochemical components, total phenol and mineral contents and antioxidant activity of six major medicinal plants from Rayen, Iran. Natural Product Research . 2018;32(5):564–567. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1315579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rauf A., Uddin G., Siddiqui B. S., et al. Bioassay-guided isolation of novel and selective urease inhibitors from Diospyros lotus. Chinese Journal of Natural Medicines . 2017;15(11):865–870. doi: 10.1016/S1875-5364(18)30021-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mahernia S., Bagherzadeh K., Mojab F., Amanlou M. Urease inhibitory activities of some commonly consumed herbal medicines. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research . 2015;14(3):943–947. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tahseen G., Kalsoom A., Faiz-ul-Hassan N., Choudhry M. Screening of selected medicinal plants for urease inhibitory activity. Biologie et Médecine . 2010;2:64–69. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Assefa S. T., Yang E. Y., Chae S. Y., et al. Alpha glucosidase inhibitory activities of plants with focus on common vegetables. Plants . 2020;9(1):2–17. doi: 10.3390/plants9010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Vvm A. P., Kranthi K., Punnagai K., David D. C. Evaluation of Alpha-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of Vinca rosea. Biomedical and Pharmacology Journal . 2019;12(2):783–786. doi: 10.13005/bpj/1700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bhatia A., Singh B., Arora R., Arora S. In vitro evaluation of the α-glucosidase inhibitory potential of methanolic extracts of traditionally used antidiabetic plants. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2019;19(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2482-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sancheti S., Sancheti S., Lee S.-H., Lee J. E., Seo S. Y. Screening of Korean medicinal plant extracts for α-glucosidase inhibitory activities. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research . 2011;10(2):261–264. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gök H. N., Orhan N., Özüpek B., Pekacar S., Selvi S. N., Orhan D. D. Standardization of Juniperus macrocarpa Sibt. & Sm. and Juniperus excelsa M. Bieb. extracts with carbohydrate digestive enzyme inhibitory and antioxidant activities. Iranian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research . 2021;20(3):441–455. doi: 10.22037/ijpr.2021.114838.15055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khatib A., Khozirah S., Hamid A., Hamid M., Wa W. N. Evaluation of the α-glucosidase inhibitory and free radical scavenging activities of selected traditional medicine plant species used in treating diabetes. International Food Research Journal . 2019;26(1):75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ibrahim M. A., Habila J. D., Koorbanally N. A., Islam M. S. A-Glucosidase and α-amylase inhibitory compounds from three African medicinal plants: an enzyme inhibition kinetics approach. Natural Product Communications . 2017;12(7):1125–1128. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zarei M. A., Tahazadeh H. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitory activity in methanol extract of some plants from Kurdistan province. Journal of Medicinal Plant Research: Planta Medica . 2020;4(72):227–235. doi: 10.29252/jmp.4.72.S12.227. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rungprom W. Inhibitory effect on α-glucosidase by traditional Thai medicinal plants. Current Applied Science and Technology . 2014;14(2):87–91. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karioti A., Carta F., Supuran C. T. Phenols and polyphenols as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Molecules . 2016;21(12):p. 1649. doi: 10.3390/molecules21121649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rudenko N. N., Borisova-Mubarakshina M. M., Ignatova L. K., Fedorchuk T. P., Nadeeva-Zhurikova E. M., Ivanov B. N. Role of plant carbonic anhydrases under stress conditions. Plant Stress Physiology . 2021;4(1):301–325. doi: 10.5772/intechopen.91971. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aydin F. G., Türkoğlu E. A., Müslüm K., Taşkin T. In vitro carbonic anhydrase inhibitory effects of the extracts of Satureja cuneifolia. Türk Tarım ve Doğa Bilimleri Dergisi . 2021;8:1146–1150. doi: 10.30910/turkjans.980819. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Carreyre H., Carré G., Ouedraogo M., et al. Bioactive natural product and superacid chemistry for lead compound identification: a case study of selective hCA III and L-Type Ca2+ current inhibitors for hypotensive agent discovery. Molecules . 2017;22(6):p. 915. doi: 10.3390/molecules22060915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets on which the conclusion of the manuscript relies are presented in the paper.