Abstract

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a dysregulated immune disorder in children, associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection or malignancies. In severe forms, HLH presents with signs and symptoms of hyperinflammation that progress to life-threatening multiorgan failure. Intervention with an extracorporeal immunomodulatory treatment utilizing a selective cytopheretic device (SCD) could be beneficial. The SCD with regional citrate anticoagulation selectively binds the most highly activated circulating neutrophils and monocytes and deactivates them before release to the systemic circulation. Multiple clinical studies, including a multicenter study in children, demonstrate SCD therapy attenuates hyperinflammation, resolves ongoing tissue injury and allows progression to functional organ recovery. We report the first case of SCD therapy in a patient with HLH and multi-organ failure.

Case diagnosis/treatment

A previously healthy 22-month-old toddler presented with fever, abdominal distension, organomegaly, pancytopenia, and signs of hyperinflammation. EBV PCR returned at > 25 million copies. The clinical and laboratory pictures were consistent with systemic EBV-positive T-cell lymphoma with symptoms secondary to HLH. The patient met inclusion criteria for an ongoing study of integration of the SCD with a continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT) as part of standard of care. The patient received CKRT-SCD for 4 days with normalization of serum markers of sepsis and inflammation. The patient underwent hematopoietic stem cell transplantation 52 days after presentation and has engrafted with normal kidney function 8 months later.

Conclusions

SCD treatment resulted in improvement of poor tissue perfusion reflected by rapid decline in serum lactate levels, lessened systemic capillary leak with discontinuation of vasoactive agents, and repair and recovery of lung and kidney function with extubation and removal of hemodialysis support.

Keywords: Extracorporeal Immunomodulation, Child, Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis, Case Report

Introduction

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a dysregulated immune disorder [1]. It most often occurs in infants and children associated with Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) infection or malignancies [2, 3]. In its most severe form, HLH presents with signs and symptoms of hyperinflammation that progress to multiorgan failure with life-threatening consequences. The excessive inflammatory condition arises from dysregulation of critical pathways important in the resolution of the immunologic response to infection. In normal individuals, the response to infection promotes antigen-specific cytotoxic lymphocytes (CTL) to undergo clonal expansion to identify and undertake cell-mediated cytolysis of infected cells, including monocytes and histiocytes (macrophages and dendritic cells). Following pathogen clearance, this immune response is self-limiting and resolves in well-orchestrated pathways. Patients with impaired perforin and granzyme-dependent cytotoxic/apoptotic processes develop HLH due to inability to destroy infected and activated mononuclear phagocytic cells [1, 4]. This inability to control CTL and histiocyte activation often promotes an excessive and unrelenting inflammatory response cascading to a cytokine storm and multiorgan dysfunction. In severe cases, urgent use of proapoptotic chemotherapy (etoposide) and immunosuppressive drugs (corticosteroids) to reduce CTL and histiocyte activation have been found to be effective [1–3]. For unremitting cases, immunosuppressive therapy with emapalumab (anti-interferon ℽ antibody) or anakinra (interleukin-1 receptor inhibitor) is used [5, 6]. At times, however, the excessive systemic inflammatory process has progressed to such severe multiorgan injury that current approaches are too late to be effective.

In this regard, intervention with a developing extracorporeal immunomodulatory treatment utilizing a selective cytopheretic device (SCD) could be considered. This approach has recently been shown to improve clinical outcomes in adult patients experiencing COVID-19-related cytokine storm [7]. The SCD with regional citrate anticoagulation has been shown to selectively bind the most highly activated circulating neutrophils and monocytes in blood and deactivate them before release back to systemic circulation [8]. This catch, deactivation, and release of these circulating cells of the innate immunologic system attenuates the final common pathway of excessive systemic inflammation resulting in multiorgan injury. Multiple clinical studies have demonstrated that this intervention results in attenuation of the hyperinflammation, resolution of ongoing tissue injury and progression to functional organ recovery [9, 10], including a recently published multi-center study in children [11]. The present case report describes the first use of the SCD to treat a child with EBV-related HLH with rapid resolution of cytokine storm and recovery from multiorgan failure.

Case synopsis

The patient was a previously healthy 14.1 kg child who presented with a week of fever, abdominal distension, organomegaly, pancytopenia, and signs of hyperinflammation. EBV PCR returned at > 25 million copies, cell separation and individual EBV PCR quantification revealed the disease burden was predominantly affecting T cells. The clinical and laboratory picture was consistent with systemic EBV-positive T cell lymphoma of childhood with symptoms secondary to HLH.

Emergency department (ED) course

On arrival to the ED, the patient was ill-appearing, grunting, with distended and tender abdomen, delayed capillary refill, and slightly jaundiced. Venous blood gas resulted with pH 7.30, pC02 28.3 mmHg, and pO2 34 mmHg. Initial kidney function panel resulted with a serum sodium 127 meq/L, potassium 4.3 meq/L, chloride 98 meq/L, total CO2 16 meq/L, blood urea nitrogen 25 mg/dL, and creatinine 0.63 mg/dL. Complete blood count revealed a hemoglobin of 8.7 g/dL, white blood cell count 3.3 × 103/microliter, absolute neutrophil count 890 cells/microliter and platelet count 26 × 103/microliter. Additional abnormal labs of interest at the time included serum uric acid 9.1 mg/dL, lactic acid 8.5 mmol/L, lactate dehydrogenase 1,783 units, total/direct bilirubin 4.0/2.7 mg/dL, D-dimer > 47,000, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 24 s, C-reactive protein 19 mg/dL, ferritin 18,000 ng/mL, and procalcitonin 43 ng/mL.

The patient received 60 mL/kg of lactated Ringer’s solution and intravenous cefepime and metronidazole. Computed tomography scan revealed hepatosplenomegaly, ascites, and pleural effusions. The patient was admitted to the pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) for further management with decreased heart rate, blood pressure of 75/32, and improved capillary refill.

PICU course

The patient received invasive mechanical ventilation on PICU Day 1 for persistent metabolic acidosis without sufficient respiratory compensation. The patient started dexamethasone for presumed HLH on Day 1 and emapalumab-Izsg (anti- interferon ℽ antibody) on Day 2. Bone marrow biopsy on Day 2 showed hemophagocytosis, and the patient received one dose of anakinra (anti-interleukin-1 receptor antagonist). The patient received two doses of eculizumab for an initial sc5b-9 level of 1,208 ng/mL (normal < 244 ng/mL in our clinical laboratory) due to concerns for thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA). Flow cytometry and bone marrow biopsy were consistent with a T cell clonal expansion. The patient was given a final diagnosis of EBV-mediated T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder of childhood, with symptoms of secondary HLH and questionable TMA.

The patient developed Stage 3 acute kidney injury (AKI) with a peak serum creatinine level of 1.81 mg/dL on Day 2. Serum lactic acid level increased from 6.8 mmol/L to 18.2 mmol/L on Day 2. The patient was initiated on continuous kidney replacement therapy (CKRT) with a Prismaflex™ HF20™ filter (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) for the indication of severe AKI and lactic acidosis refractory to medical management. The patient met inclusion criteria for an ongoing multicenter interventional single-arm study of SCD therapy in critically ill children weighing 10–20 kg, with AKI, more than one organ failure and receiving CKRT as part of the standard of clinical care (CCHMC IRB#2021–0170, NCT04869787). The patient’s parental guardians provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. The consent form stipulates that data collected as part of this study may be used for peer-reviewed publication.

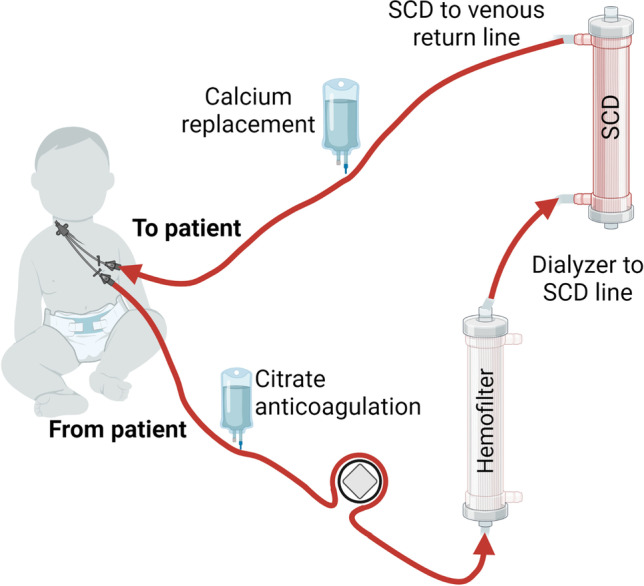

The CKRT-SCD configuration is depicted in Fig. 1. The relevant clinical course after CKRT-SCD therapy initiation is depicted in Table 1. The patient received only four total days of CKRT-SCD therapy (a maximum of 10 are allowed per study protocol), as the patient was extubated, off all vasoactive medications on Day 3 of CKRT therapy and had CKRT discontinued after Day 4. The circuit ionized calcium was within target range (< 0.4 mmol/L) 98.9% percent of the time (81.9/82.8 h on SCD). The patient received a 2-h intermittent hemodialysis treatment 2 days after CKRT-SCD discontinuation for a serum potassium of 5.1 meq/L. The patient has had normal kidney function since that single intermittent hemodialysis treatment. The patient underwent successful matched unrelated donor stem cell transplantation six weeks after presentation, demonstrated engraftment on Day 52 and has had multiple follow-up assessments showing 100% donor engraftment and normal kidney function (serum creatinine 0.25 mg/dL, cystatin C 0.824 mg/L (estimated cystatin C GFR 107 ml/min) eight months after presentation.

Fig. 1.

SCD CRRT circuit diagram (Created with BioRender.com)

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory value course

| PICU Admission | Day 0a | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day 3 | Day 4 | 120 Hour Post-SCD & PICU DC | Follow-up Day 60 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute complete blood counts | ||||||||

| WBC (103/mcL) | 3.27 | 13.03 | 14.50 | 6.37 | 1350 | 0.44 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Neutrophil (cells/mcL) | 890 | 810 | 10,850 | 5,660 | 1,150 | 250 | 0 | 0 |

| Monocyte (cells/mcL) | 30 | 230 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 0 |

| Lymphocyte (cells/mcL) | 2,180 | 4,460 | 2,900 | 540 | 190 | 170 | 280 | 50 |

| Microangiopathy markers | ||||||||

| Platelet count (103/mcL) | 26 | 86 | 65 | 36 | 17 | 6 | 19 | 38 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 163 | 92 | 128 | 75 | 114 | 99 | 161 | NA |

| LDH (units/L) | 1,783 | 11,209 | 13,490 | 7,750 | 4,377 | 2,226 | 1,058 | 301 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 18,218 | 68,241 | 92,228 | 82,397 | 42,230 | 24,095 | 3,010 | NA |

| Liver function tests | ||||||||

| AST (units/L) | 303 | 2,556 | 2,429 | 1,854 | 991 | 490 | 135 | 27 |

| ALT (units/L) | 174 | 460 | 449 | 430 | 272 | 216 | 157 | 14 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 3.1 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 3.4 | 3.9 | 5.4 | 1.9 | 0.3 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.4 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 3.0 |

| Acute kidney injury-related parameters | ||||||||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.65 | 0.88 | 0.62 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.52 | 1.81 | 0.21 |

| Urine NGAL (ng/mL) | 143 | 14,441 | 2,866 | 14,187 | 13,475 | 8,173 | 73 | NA |

| Body weight (kg) | 14.1 | 16.9 | 17.2 | 17.1 | 15.7 | 15.0 | 15.1 | 15.0 |

| Cystatin C GFR (mL/min) | 71 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 128 |

| Acidemia tests | ||||||||

| Serum CO2 (mmol/L) | 10 | 15 | 19 | 23 | 25 | 24 | 26 | 18 |

| Serum lactate (mmol/L) | 8.6 | 24.1 | 16.8 | 11.7 | 3.61 | 2.21 | 1.3 | NA |

| Immunologic Markers (pg/mL) | ||||||||

| IL-6 (normal 0–16) | NA | 65 | NA | 172 | NA | < 10 | < 10 | NA |

| IL-8 (normal 24–39) | NA | 587 | NA | 221 | NA | 241 | 151 | NA |

| IL-10 (normal 8–16) | NA | 3855 | NA | 2681 | NA | 144 | 7 | NA |

| TNFa(normal 0–16) | NA | 10.5 | NA | 2.8 | NA | 2.1 | < 1.5 | NA |

| MCP-1(normal 20–80) | NA | 966 | NA | 807 | NA | 772 | 344 | NA |

| Neutrophil Granule Type/Constituent | ||||||||

| Primary | Elastase | NA | > 1000 | NA | 835.4 | NA | 51.1 | 11.7 | NA |

| Secondary | Lactoferrin | NA | 147 | NA | 235 | NA | < 24 | < 24 | NA |

| Tertiary | MMP9 | NA | 178 | NA | 52 | NA | < 23.4 | < 23.4 | NA |

NA, Not Available; IL, Interleukin; TNF, Tumor Necrosis Factor; MCP, Monocyte Chemoattractant Protein; MMP, Matrix Metalloproteinase

a. These samples were obtained immediately before CKRT-SCD initiation

As displayed in Table 1, SCD treatment resulted with a progressive decline in plasma cytokine levels and in neutrophil activation markers, demonstrating resolution of cytokine storm and systemic neutrophil activation.

Discussion

This patient presented with clinical criteria for HLH disease, including fever, splenomegaly, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, elevated serum ferritin levels and bone marrow evidence of hemophagocytosis [1]. The patient was rapidly deteriorating with 5 acute organ failures despite aggressive therapy with multiple immunosuppressant agents. The patient’s clinical picture was consistent with severe hyperinflammation with cytokine storm. This was confirmed with elevated plasma levels of multiple cytokines and neutrophil granule constituents (Table 1). Activation of neutrophils and organ microvasculature results in capillary sludging and tissue hypoxia. Migration of leukocytes into tissue and release of degradation enzymes promote toxic tissue injury. The concomitant hypoxic and toxic tissue injury leads to solid organ dysfunction and failure [12]. With this perspective, SCD treatment was undertaken to mitigate the excessive activation of the effector cells of the innate immunologic pathway. In the low ionized calcium (iCa) environment promoted with regional citrate anticoagulation and the low shear force approximating capillary shear, the SCD membranes selectively bind the most activated neutrophils and monocytes due to the calcium dependency of binding reactions of cell surface integrins on the leukocyte [13, 14]. Upon binding the neutrophils degranulate and in the low iCa are promoted to their apoptotic program [15]. After deactivation, they are released back into the systemic circulation and are phagocytosed and degraded by the reticuloendothelial system. Similarly, the most proinflammatory monocytes are bound, deactivated in the low iCa environment, and released back to the circulation. This process results in a shift of the circulating pool of monocytes to a less inflammatory phenotype [16]. In this manner, the SCD is a continuous autologous leukocyte processing system which immunomodulates a systemic hyperinflammatory state without immunosuppression [9].

This patient received several immune modulating medications in addition to high-dose steroids and the SCD filter. The first was emapalumab-lzsg, an antibody that binds both soluble and receptor bound IFNγ thereby neutralizing its biologic activity [17]. The reported median time to response to emapalumab-lzsg in children with HLH, which at minimum was defined as a change of greater than 50% from baseline in at least three clinical and laboratory abnormalities associated with HLH, was 8 days (95% CI 5–10 days) [17]. Anakinra, a recombinant humanized interleukin-1 receptor blocker, was also used. While response to anakinra is described as rapid in the literature, it is used off-label, so there is no published trial to clearly define dosages, administration routes, and outcome terminology [5]. One patient with malignancy-associated HLH and treated with subcutaneous anakinra appeared to have an inflection point in multiple markers of disease severity on day 5 of therapy [18]. Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds Complement Protein 5, has been shown to be beneficial in managing HLH patients with concomitant thrombotic microangiopathy; however, time to treatment response is unclear [19].

Importantly, SCD treatment in this patient resulted in rapid improvement of poor tissue perfusion as reflected by the rapid decline in serum lactate levels, lessened systemic capillary leak with discontinuation of vasoactive agents, and repair and recovery of lung and kidney function with extubation and removal of hemodialysis support. SCD treatment in this case had no device-related adverse events with progressive reversal of his thrombocytopenia. Once the patient stabilized and recovered, a bone marrow stem cell transplant was successful as the definitive therapy for his T cell lymphoma.

The key point in this case is the recognition that the final common pathway of systemic hyperinflammation resulting in multiorgan failure is the effector cells of the innate immunologic system. The activation of neutrophils and monocytes is the key driver of the developing hypoxic and toxic tissue damage of solid organs. The immunomodulation of these cellular elements rather than soluble biomarkers of inflammation is the critical target for effective therapy.

Disclosures

SLG consults for SeaStar Medical, Inc. HDH and AW report a financial interest in SeaStar Medical, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Risma K, Jordan MB. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: updates and evolving concepts. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2012;24:9–15. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834ec9c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marsh RA. Epstein-Barr Virus and Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1902. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim WY, Montes-Mojarro IA, Fend F, Quintanilla-Martinez L. Epstein-Barr Virus-Associated T and NK-Cell Lymphoproliferative Diseases. Front Pediatr. 2019;7:71. doi: 10.3389/fped.2019.00071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.de Saint BG, Menasche G, Fischer A. Molecular mechanisms of biogenesis and exocytosis of cytotoxic granules. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:568–579. doi: 10.1038/nri2803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bami S, Vagrecha A, Soberman D, Badawi M, Cannone D, Lipton JM, Cron RQ, Levy CF. The use of anakinra in the treatment of secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28581. doi: 10.1002/pbc.28581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lounder DT, Bin Q, de Min C, Jordan MB. Treatment of refractory hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with emapalumab despite severe concurrent infections. Blood Adv. 2019;3:47–50. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018025858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yessayan L, Szamosfalvi B, Napolitano L, Singer B, Kurabayashi K, Song Y, Westover A, Humes HD. Treatment of Cytokine Storm in COVID-19 Patients With Immunomodulatory Therapy. ASAIO J. 2020;66:1079–1083. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000001239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ding F, Song JH, Jung JY, Lou L, Wang M, Charles L, Westover A, Smith PL, Pino CJ, Buffington DA, Humes HD (2011) A biomimetic membrane device that modulates the excessive inflammatory response to sepsis. PLoS One 6:e18584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Pino CJ, Westover AJ, Johnston KA, Buffington DA, Humes HD. Regenerative Medicine and Immunomodulatory Therapy: Insights From the Kidney, Heart, Brain, and Lung. Kidney Int Rep. 2018;3:771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yessayan LT, Neyra JA, Westover AJ, Szamosfalvi B, Humes HD. Extracorporeal Immunomodulation Treatment and Clinical Outcomes in ICU COVID-19 Patients. Crit Care Explor. 2022;4:e0694. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldstein SL, Askenazi DJ, Basu RK, Selewski DT, Paden ML, Krallman KA, Kirby CL, Mottes TA, Terrell T, Humes HD. Use of the Selective Cytopheretic Device in Critically Ill Children. Kidney Int Rep. 2021;6:775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2020.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown KA, Brain SD, Pearson JD, Edgeworth JD, Lewis SM, Treacher DF. Neutrophils in development of multiple organ failure in sepsis. Lancet. 2006;368:157–169. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ivetic A. Signals regulating L-selectin-dependent leucocyte adhesion and transmigration. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2013;45:550–555. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2012.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li R, Haruta I, Rieu P, Sugimori T, Xiong JP, Arnaout MA. Characterization of a conformationally sensitive murine monoclonal antibody directed to the metal ion-dependent adhesion site face of integrin CD11b. J Immunol. 2002;168:1219–1225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.3.1219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Whyte MK, Hardwick SJ, Meagher LC, Savill JS, Haslett C. Transient elevations of cytosolic free calcium retard subsequent apoptosis in neutrophils in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:446–455. doi: 10.1172/JCI116587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szamosfalvi B, Westover A, Buffington D, Yevzlin A, Humes HD. Immunomodulatory Device Promotes a Shift of Circulating Monocytes to a Less Inflammatory Phenotype in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients. ASAIO J. 2016;62:623–630. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locatelli F, Jordan MB, Allen C, Cesaro S, Rizzari C, Rao A, Degar B, Garrington TP, Sevilla J, Putti MC, Fagioli F, Ahlmann M, Dapena Diaz JL, Henry M, De Benedetti F, Grom A, Lapeyre G, Jacqmin P, Ballabio M, de Min C. Emapalumab in Children with Primary Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1811–1822. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta P, Cron RQ, Hartwell J, Manson JJ, Tattersall RS. Silencing the cytokine storm: the use of intravenous anakinra in haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis or macrophage activation syndrome. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020;2:e358–e367. doi: 10.1016/S2665-9913(20)30096-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gloude NJ, Dandoy CE, Davies SM, Myers KC, Jordan MB, Marsh RA, Kumar A, Bleesing J, Teusink-Cross A, Jodele S. Thinking Beyond HLH: Clinical Features of Patients with Concurrent Presentation of Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis and Thrombotic Microangiopathy. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40:699–707. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00789-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]