Highlights

-

•

The evidence on public health guidelines implementation is scarce.

-

•

Most implementation of public health guidelines centres on individuals’ behaviour.

-

•

Most evaluations of public health guidelines focus on barriers to implementation.

Keywords: Implementation research, Health guidelines, Evaluation

Abstract

Health guidelines are important tools to ensure that health practices are evidence-based. However, research on how these guidelines are implemented is scarce. This integrative review aimed to: identify the literature on evaluation of public health guidelines implementation to explore (a) the topics which public health guidelines being implemented and evaluated in their implementation process are targeting; (b) how public health guidelines are being translated into action and the potential barriers and facilitators to their implementation; and (c) which methods are being used to evaluate their implementation. A total of 2001 articles published since 2000 and related to both clinical and public health guidelines implementation was identified through searching four databases (PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Scopus). After screening titles and abstracts, only 10 papers related to public health guidelines implementation, and after accessing full-text, 8 were included in the narrative synthesis. Data were extracted on: topic and context, implementation process, barriers and facilitators, and evaluation methods used, and were then synthesised in a narrative form using a thematic synthesis approach. Most of these studies focussed on individual behaviours and targeted specific settings. The evaluation of implementation processes included qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods. The few articles retrieved suggest that evidence is still limited and highly context specific, and further research on translating public health guidelines into practice is needed.

1. Introduction

Over the past two decades, public health guidelines have significantly increased. For instance, the first public health guidance published by the National Institute for health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK dates back only to 2007, and today NICE has already published about 70 public health guidelines (NICE - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020). Public health guidelines or recommendations cover a wide range of topics which reflect the variety of health-related topics which public health deals with, from more traditional clinical issues such as vaccination or screening, to recommendations for healthier lifestyles and risk factors prevention. However, despite this rapid increase, there is a lack of evaluation on the extent to which guidelines are implemented and the impact which their implementation generates. Moreover, although research on knowledge translation of clinical practice guidelines has recently increased (Fischer et al., 2016, Gagliardi et al., 2011, Shiffman et al., 2005), researching the implementation of public health guidelines is still limited. This makes it difficult for public health practitioners to fully take advantage of evidence-based guidelines, given the challenges associated with its translation into practice, hence the need to review current evidence on implementation strategies for public health guidelines and their evaluation.

This review is part of a larger project, EvaluA GPS (from its Spanish acronym: Evaluate the Implementation of Health Promotion Guidelines) financed by the Carlos III Health Institute of the Ministry of Health in Spain. EvaluA GPS aims to evaluate the implementation of the first evidence based public health guideline included in the Spanish catalogue of clinical practice guidelines, the NG44 Guide «Community engagement: improving health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities» adapted to the Spanish context (Cassetti et al., 2018). This review aimed to identify the literature on public health guidelines implementation, to explore (a) the topics which public health guidelines being implemented and evaluated in their implementation process are targeting; (b) how public health guidelines are being translated into action and the potential barriers and facilitators to public health guidelines’ implementation; and (c) which study designs and methods are currently being used to evaluate public health guidelines implementation.

2. Methods

An integrative review approach was chosen to carry out the study (Noble and Smith, 2018). A systematic search strategy was developed using a combination of key terms and synonyms related to ‘implementation’, ‘guidelines’ and ‘analysis’ or ‘evaluation’. After initial iterative searches, a time limit was set as to only include papers published since the year 2000, given that public health guidelines have started being developed in recent years. Proximity operators between the word ‘implementation’ and ‘guidelines’ were adopted in some of the databases. The final search was carried out between January and March 2021 in four databases: PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science and Scopus (see Appendix 1 for an example of search strategy). Studies were included when they analysed and/or evaluated the implementation of public health guidelines.

Following this, titles and abstracts were screened to identify articles related to the implementation and/or evaluation of public health guidelines. The selected papers were then accessed full text and were finally included in the narrative synthesis. Given the variety of methodology adopted in the included studies, quality appraisal was carried out using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., 2018). Data were then extracted on topic and context, implementation process, barriers and facilitators, and evaluation methods used. The extracted information was analysed using a thematic synthesis approach and synthesised in a narrative form (Thomas and Harden, 2008). To enhance the quality of this review, the ENTREQ statement (Tong et al., 2012) was used to guide the analysis and reporting of the results.

3. Results

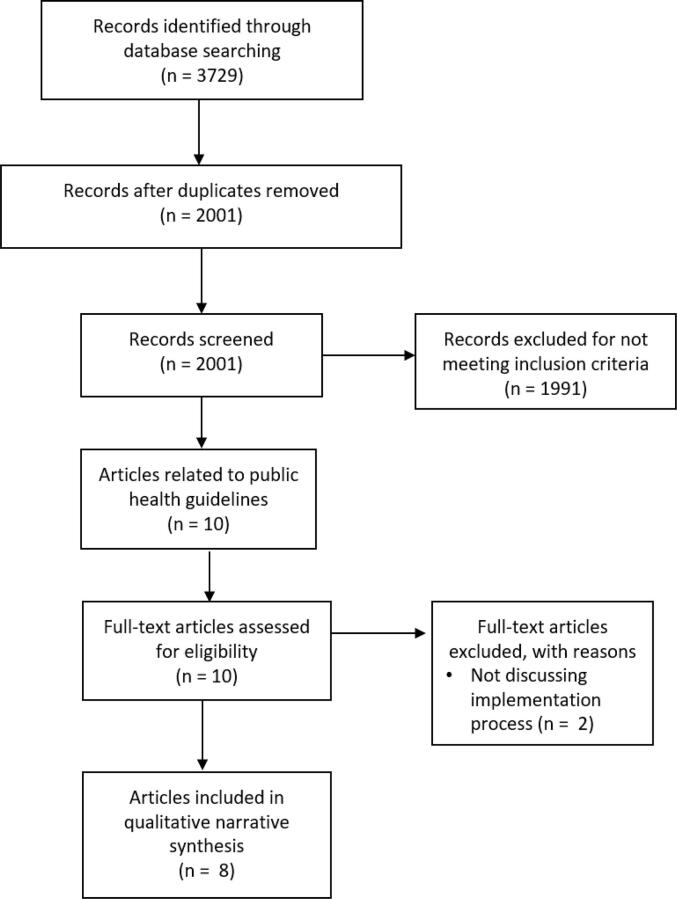

A total of 2001 articles was retrieved from the searches after removal of duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts, only 10 retrieved papers were related to public health guidelines. Of these, after accessing them full-text, 8 papers met the inclusion criteria (“implementation and/or evaluation of public health guidelines”), and were included in the narrative synthesis. The PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009) below details the selection and screening process (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (Moher et al., 2009) for the review of evaluation studies on public health guidelines implementation.

As for the topics covered, all the public health guidelines discussed in the articles were concerned with the promotion of individual health behaviours, ranging from supporting the uptake of healthy diets (Addis, 2019, Evenhuis et al., 2019, Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016, Keller et al., 2008), to promoting increased physical activity (Davis et al., 2017) or targeting the reduction of a combination of individual risk factors such as smoking or obesity (Jones et al., 2015, Nordstrand et al., 2016, Rod and Terp Høybye, 2016) (Table 1).

Table 1.

below provides an overview of the information extracted from each paper related to the evaluation of the implementation process.

| Reference | TOPIC and CONTEXT | IMPLEMENTATION PROCESS | BARRIERS and/or FACILITATORS TO IMPLEMENTATION | EVALUATION OF THE IMPLEMENTATION PROCESS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Addis (2019). Implementing minimum nutritional guidelines for school meals in secondary schools in Wales: What are the challenges?. | Implementing the “Appetite for Life policy” in 4 secondary schools in Wales, to enhance healthy eating in young people | [Although the paper does not include a specific description of the implementation process, it appears that dietary guidelines were introduced in schools in Wales and had to be followed, allowing limited flexibility to adapt menus and contents to the local settings.] | Main barriers: (1) the lack of healthy food culture among students, resulting in students buying junk food outside school and (2) the lack of flexibility in the menus included in the new policy, leaving catering staff unable to adapt menus to their context and students’ taste.. | Case-study research, with semi-structured interviews (n = 13) with different stakeholders (policy-makers, local authority and teachers and catering staff at schools) |

| Davis et al. (2017). Research to Practice: Implementing Physical Activity Recommendations. | Implementing evidence-based guidelines on physical activity in rural Hispanic and American Indian communities | Alliance between university and local stakeholders, and agreement on goals and outcomes. Six implementation strategies were chosen, and implemented according to what local partners considered as feasible. | Main facilitators: (1) engaging with local partnerships to develop a tool for the guideline implementation and (2) adapting the implementation to the local contexts | 5 years follow-up using interviews, observations and conducting content analysis of documents related to the project. |

| Evenhuis et al. (2019). Implementation of guidelines for healthier canteens in Dutch secondary schools: A process evaluation. | Implementing the “Healthy Canteen Guidelines” to enhance healthy eating in secondary school canteens in the Netherlands | Stakeholders were engaged in the development of the implementation tool. A variety of implementation tools were implemented, based on the feedback from stakeholders and on behavioural models. Tools ranged from having a banner on the school website, to having an app where canteen staff could enter the food they prepared, to receive feedback on whether it was healthy or not. | Main facilitators: (1) receiving personal advice targeted at their own school and context and (2) flexibility to choose which implementation tool could work better for them. Main barrier: competing interest with neighbourhoods’ shops selling junk food | Before/after questionnaires about perceived individual and environmental factors affecting the implementation. Measurement of process indicators such as whether the tools were delivered to stakeholders (dose delivery), whether stakeholders read, understood, and used them (dose received), and a 1–5 satisfaction question. |

| Rod and Terp Høybye (2016). A case of standardization? Implementing health promotion guidelines in Denmark. | Implementing the “Danish National Health Promotion Guidelines” focusing on individual behaviours recommendations | In 2012, Denmark published national Health Promotion guidelines, which should be implemented by local authorities in municipalities. The guidelines contain more than 300 recommendations about policy changes, health promotion education, information or screening strategies. | Main facilitators: (1) recommendations were taken as evidence-based practice which provided justification for health promotion actions; (2) using a traffic light tool allowed health promotion officers to use it as a tool for advocacy with politicians and decision-makers when planning further actions to promote health. Main barrier: recommendations were vague, generating problems in terms of how to turn these into actions. |

Two monitoring surveys have been carried out, in 2013 and 2014, to account for how local authorities were implementing the guidelines. The evaluation described in the paper was carried out through interviews to stakeholders (Health Promotion officers and politicians) and participant observation during 3–6 months, including observations of meetings. |

| Jilcott Pitts et al. (2016). Implementing healthier food service guidelines in hospital and federal worksite cafeterias: barriers, facilitators and keys to success. | Implementing the “Hospital Healthier Food Initiative” and a guideline for healthier food in federal workplace canteens and vending machines to enhance healthy diet in workplace for hospital healthcare personnel and federal staff in the US | [The paper does not include a full description of the implementation process, but it appears that both the Hospital Healthier Food Initiative and the guideline for healthier food in federal workplace canteens and vending machines shared similar recommendations, such as reducing fat consumption or eliminating it from menus options, or providing nutritional information to buyers]. | Most respondents found it quite easy to implement the guidelines, a main facilitator could be found in its flexibility, as they had to adapt recipes to meet nutrition recommendations and to meet customers desires. Main barriers: (1) Customers' dissatisfaction and (2) potential concerns about costs and legal permits to follow | Mixed methods with a small sample (n = 9) of five hospitals and four federal worksites canteens. The study used a questionnaire about barriers and facilitators and then interviews with stakeholders (cafeteria managers and serving staff) regarding how implementation was carried out |

| Jones et al. (2015) Improving the implementation of NICE public health workplace guidance: an evaluation of the effectiveness of action-planning workshops in NHS trusts in England. | Implementing the “NICE guidelines to enhance workplace health promotion” in NHS trusts in the UK | National audit to check implementation of these guidance developed in 2010, with two rounds, in 2010 and in 2013. This was accompanied by an offer of implementation workshops with follow up at 3, 6 and 12 months to 40 trusts who scored lower in the first round of questionnaire. The design of the implementation workshop was developed based on interviews with those NHS trusts which scored higher in the first round of audit. The audit team was multidisciplinary. | Main facilitator: providing implementation workshops to those NHS trust with lower audit score (workshops were developed with NHS trusts which scored highest) | 126 NHS trusts in round 1 audit questionnaire. Then, a group of NHS trusts that scored high in round 1 audit questionnaires were involved in interviews. The data collected in these interviews informed the development of implementation workshops. |

| Keller et al. (2008) Food-based dietary guidelines and implementation: lessons from four countries--Chile, Germany, New Zealand and South Africa. | Implementing the “Food Based Dietary Guidelines” in Chile, Germany, New Zealand and South Africa | Implementation was top-down, with governments or responsible institutions delivering written information about the food and dietary guidelines | The paper offers a table where some facilitators are described in each country. Overall, main facilitators: (1) health care staff is trained and supported; (2) consistency in the health messages delivered. Main barriers: (1) limited mass communication of health messages; (2) lack of funding | Interviews with one representative of 4 key sectors: ministry of health, 5-a-day programme, academics and a stakeholder from the fruit and veg production sector. Most participants preferred to respond via email, while 3 responded via telephone interview |

| Nordstrand et al. (2016) Implementation of national guidelines for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A phenomenographic analysis of public health nurses’ perceptions. | Implementing the “National guidelines for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity among children and adolescents in well-baby clinics and school health services” in Norway | [The paper does not describe the implementation process in details, but it appears that public health nurses are encouraged to ‘act’ at structural and individual level, to prevent overweight and obesity problems in primary health care patients] | Factors influencing implementation were context (in rural areas it was more difficult to have group work), need for commitment to change and for interdisciplinary work, resources and competence. | Interviews with 18 Public Health Nurses who worked in school health service facilities or well-baby clinics from various areas of Norway. Phenomenological approach was used in analysis to characterize the implementation process. |

In terms of the implementation settings, five papers discussed guidelines implemented in closed and defined settings, like schools (Addis, 2019, Evenhuis et al., 2019) or workplace (Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016, Jones et al., 2015) or were aimed at different groups and implemented within a health services (Nordstrand et al., 2016). The remaining three papers related to wider settings: Davis et al. (2017) discussed a guideline implementation which targeted specific groups within a place-based community, while Keller et al. (2008) and Rod and Terp (2016) provided an analysis of the implementation of guidelines at country level.

In terms of the focus of the papers, five papers (Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016, Jones et al., 2015, Keller et al., 2008, Nordstrand et al., 2016, Rod and Terp Høybye, 2016) focussed on how the implementation process was perceived by key stakeholders, with an analysis of its potential barriers and facilitators, while the remaining three (Addis, 2019, Davis et al., 2017, Evenhuis et al., 2019) included both a discussion regarding the implementation and the results achieved from it.

More specifically, in relation to the implementation process, two papers described the development of one or more tools to facilitate knowledge translation. In Evenhuis et al. (2019) a variety of implementation tools were developed, based on the feedback from stakeholders and on behavioural models. Tools aimed to facilitate the understanding of the recommendations, and ranged from having a banner on the school website, to having an app where canteen staff could enter the recipe they prepared and receive feedback on whether it was healthy or not. In Davis et al. (2017), through a partnership between university and local stakeholders, a booklet with six implementation strategies on physical activity was developed, and each local partner then implemented what they considered most feasible. In another study, local personnel received specific training as a way to support them to adapt their practices to reflect the guidelines (Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016). In Jones et al. (2015), specific implementation workshops were designed based on interviews with those stakeholders who scored higher in the initial audit on the guideline implementation.

Three of the papers described a participatory approach to engage stakeholders and facilitate the implementation process (Davis et al., 2017, Evenhuis et al., 2019, Jones et al., 2015). Interestingly, engaging stakeholders was one of the main facilitators identified in some of the papers, together with the flexibility in the implementation approach (Davis et al., 2017, Evenhuis et al., 2019, Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016) and the importance of working at intersectoral levels or having a multidisciplinary team to support the process (Davis et al., 2017, Nordstrand et al., 2016, Rod and Terp Høybye, 2016). Conversely, described potential barriers for the implementation process were lack of training, perceived lack of skills, or need for additional information (Evenhuis et al., 2019, Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016, Keller et al., 2008, Nordstrand et al., 2016), rigidity in the guidelines recommendations (Addis, 2019) or additional costs associated with changes in practice (Addis, 2019, Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016).

Finally, in terms of the methodologies used, most of the studies followed qualitative methods, combining interviews and observations (Addis, 2019, Davis et al., 2017, Keller et al., 2008, Nordstrand et al., 2016, Rod and Terp Høybye, 2016) while three studies took a mixed methods approach (Evenhuis et al., 2019, Jilcott Pitts et al., 2016, Jones et al., 2015).

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review to analyse the evaluation of public health guidelines’ implementation. It has found a limited number of publications on this topic, which may suggest that the evidence in this area is still scarce. Despite the small number of included papers, the findings from this review highlight some similarities across the studies which are worth discussing in more detail.

First, the majority of the studies found were focused on diet and physical activity guidelines, and adopted mainly a behavioural change approach to tackle those issues, without considering the influence of wider social determinants of health. Although obesity and overweight are indeed one of the main public health issues globally (Williams et al., 2015), it should be worth exploring potential explanations as to why no papers were found which evaluated the implementation of guidelines tackling other public health issues. This might be influenced by the predominant models of health and healthcare in Western health systems, which tend to focus on individuals’ behaviours to explain diseases (Baeta, 2015). Similarly, the limited attention to contextual factors other than individual behaviours might also be related to the traditional organisation of most Western national governments and policies, which lack intersectoral approaches to tackle different health determinants (Foot et al., 2020, Mackenbach, 2020, World Health Organization, 2019). Significantly, taking up healthy behaviours is important to improve our health, but there is a need to strengthen other factors which can be supportive of health, such as surrounding environments, health services and public policies, as suggested in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (WHO - World Health Organization, 1986).

A second point to discuss refers to the settings of guidelines implementation. The majority of the papers included in this review discussed guidelines implemented in specific settings, with pre-determined boundaries, such as schools or workplace. However, only two papers (Evenhuis et al., 2019, Jones et al., 2015) took contextual factors into account to design the implementation process, through engaging stakeholders in the identification of potential barriers and facilitators. This is important, as it reflects the ‘settings’ approach to health promotion, which acknowledges the contextual factors impacting on health and behaviours (Torp et al., 2014), even though its application is still limited (Newman et al., 2015).

A third point to discuss relates to the engagement of people and communities. There is increasingly supporting evidence of the importance of involving people in the implementation of guidelines. Evidence suggests that it can support improving the uptake of recommendations, as the needs and perspectives of end-users are taken into account. It can also promote its maintenance over time as it helps citizens feel the initiative as their own (Teunissen et al., 2017, van den Muijsenbergh et al., 2020). Significantly, the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC) recommends engaging patients and patients’ organisations in guidelines’ implementation processes as an effective strategy to limit or overcome potential implementation barriers (Cochrane, 2020). Similarly, in Spain, end users’ engagement is recommended as part of the implementation process in the Spanish National Institute of Clinical Practice Guidelines (GuiaSalud, 2020). Importantly, few of the studies included in this review have highlighted these approaches as being facilitators of the implementation process. Nonetheless, when participatory approaches were adopted, the level of participation was most often limited to consultation (Popay et al., 2007) using methods such as workshops or interviews with stakeholders. This can be partly related to the fact that some of the guidelines described in these articles included specific protocols for implementation, which can make it more difficult for stakeholders to act on the implementation process.

5. Study limitations and strengths

The main strength of this review is the focus on the analysis and/or evaluation of public health guidelines’ implementation, a topic which is still receiving limited attention, as the small number of included papers may suggest. However, although this review has tried to be as systematic and comprehensive as possible, there are a few limitations which are worth considering. First, limiting the searches to articles published after the year 2000 could have left out potential related studies. Nonetheless, considering that public health guidelines have been mostly published after this year, the time limit could still be considered appropriate. Second, the searchers were conducted on public health databases. However, given the variety of factors which can impact on the health of people and communities, it could be worth searching for other examples of evaluation of guidelines focussed on non-health determinants, which may have not been identified in this review.

6. Conclusions

This review has shown that research on implementation of public health guidelines is still very limited and highly context specific. Most of the studies described the implementation of guidelines centred on individual behaviours. None of the implementation processes in the reviewed articles referred to guidelines which included the approach of social determinants of health, and the participation of both the community and different sectors was limited. Moreover, the variety of implementation processes resulted in the adoption of various evaluation methods, qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods. Nonetheless, given the limited number of articles included in this review, the findings presented here can be considered as a starting point to discuss and encourage the evaluation of public health guidelines implementation as a growing research area. Further research should focus on the evaluation of public health guidelines, including exploring guidelines targeting other social determinants which can affect the health of people and communities. In this sense, the EvaluA GPS project (EvaluA GPS, 2021), which this review is part of, adds to this area of research as it aims to implement a complex guideline about community engagement to promote health, and it does so by engaging stakeholders in the development of an implementation tool and piloting in multiple settings to identify potential barriers and facilitators to its adoption.

Funding: This work was supported by the Carlos III Institutes of the Spanish Ministry of Health [grants number: PI19/01079; PI19/01525; PI19/00773 for the years 2020–2022].

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Viola Cassetti: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. María Victoria López-Ruiz: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Marina Pola-Garcia: Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ana M. García: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Joan Josep Paredes-Carbonell: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Luis Angel Pérula-De Torres: . Carmen Belén Benedé-Azagra: Conceptualization, Investigation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

(EvaluAGPS Research Group): Aldecoa Landesa, Susana; Aliaga Train, Pilar; Aviñó Juan-Ulpiano, Dory; Baraza Cano, Pilar; Barona Vilar, Carmen; Botello Diaz, Blanca del Rocío; Bueno, Manuel; Couso Viana, Sabela; Dominguez, Marta; Egea Ronda, Ana; Enriquez, Natalia; Gallego Dieguez, Javier; Gallego Royo, Alba; Gea Caballero, Vicente; Hernán García, Mariano; Hernández Goméz, Mercedes Adelaida; Iriarte, María Teresa; Lou Alcaine, María Luz; Martínez Pecharromán, María del Mar; Morin, Victoria; Nuñez Jiménez, Catalina; Peyman- Fard, Nima; Pla Consegra, Margarita; Romaguera Lliso, Amparo; Ruiz Azarola, Ainhoa; Sainz Ruiz, Pablo. EvaluAGPS Research Group is a multidisciplinary research group formed for the EvaluA GPS project. EvaluA GPS is a research coordinated by three institutions: IIS (Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Aragón); FISABIO (Fundación para el Fomento de la Investigación Sanitaria y Biomédica, Comunitat Valenciana) and IMIBIC-FIBICO (Maimonides Institute for Biomedical Research of Cordoba, Andalucía) and with the participation of the IAPP network, the PACAP program, the PAPPS program and the Community Health Alliance.

Appendix 1. – Example search strategies

The search strategy was run using the following terms in combination, limiting searchers to titles and abstracts and publications from the year 2000.

(recommendations OR guideline* OR guidance) AND (implementation OR implement* OR knowledge translation OR translat* OR adopt*) AND (evaluat* OR analys* OR analyz* OR assess* OR apprais*)

Examples of complete search in CINHAL, with proximity operators, run on August 11th, 2020:

Search #1: 399 results

(recommendations OR guideline* OR guidance) N1 (implementation OR implement* OR knowledge translation OR translat* OR adopt*)

AND

(evaluat* OR analys* OR analyz* OR assess* OR apprais*)

Search #2: 613 results

(recommendations OR guideline* OR guidance) N2 (implementation OR implement* OR knowledge translation OR translat* OR adopt*)

AND

(evaluat* OR analys* OR analyz* OR assess* OR apprais*)

References

- Addis S. Implementing minimum nutritional guidelines for school meals in secondary schools in Wales: What are the challenges? Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 2019;14:383–389. doi: 10.12968/bjsn.2019.14.8.383. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baeta S. Cultura y modelo biomédico: reflexiones en el proceso de salud enfermedad. Comunidad y Salud. 2015;13:82–84. [Google Scholar]

- V. Cassetti V. López-Ruiz J.J. Paredes-Carbonell Grupo de trabajo AdaptA GPS, PARTICIPACIÓN COMUNITARIA: Mejorando la salud y el bienestar y reduciendo desigualdades en salud Guía adaptada de la Guía NICE NG44: «Community engagement: improving health and wellbeing and reducing health inequalities» Guiasalus.es. 2018.

- Cochrane, Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group (EPOC) [WWW Document] http://www.epoc.cochrane.org 2020 accessed 4.20.21.

- Davis S.M., Cruz T.H., Kozoll R.L. Research to Practice: Implementing Physical Activity Recommendations. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2017;52:S300–S303. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Regional Office for Europe. Healthy, prosperous lives for all: the European Health Equity Status Report: WHO; 2019. Available at: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/health-equity-status-report-2019.

- Evenhuis I.J., Vyth E.L., Veldhuis L., Jacobs S.M., Seidell J.C., Renders C.M. Implementation of guidelines for healthier canteens in dutch secondary schools: A process evaluation. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16(22):4509. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer F., Lange K., Klose K., Greiner W., Kraemer A. Barriers and strategies in guideline implementation—a scoping review. Healthc. 2016;4:1–16. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EvaluA GPS, 2021. Cómo funciona el proyecto EvaluA GPS [WWW Document] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iMbhzIDPkuc 2021 accessed 10.29.21.

- Foot, J., Hopkins, T., Rippon, S., White, J., 2020. A Glass Half Full. Local Government Association. Ten Years on Review. Local Government Association.

- Gagliardi, A.R., Brouwers, M.C., Palda, V.A., Lemieux-charles, L., Grimshaw, J.M., 2011. How can we improve guideline use ? A conceptual framework of implementability 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- GuiaSalud, 2020. Guia Salud [WWW Document]. URL www.guiasalud.es (accessed 2.20.21).

- Hong, Q., Pluye, P., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., Rousseau, M.-C., Vedel, I., 2018. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. User guide. McGill 1–11.

- Jilcott Pitts S.B., Graham J., Mojica A., Stewart L., Walter M., Schille C., McGinty J., Pearsall M., Whitt O., Mihas P., Bradley A., Simon C. Implementing healthier foodservice guidelines in hospital and federal worksite cafeterias: barriers, facilitators and keys to success. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016;29:677–686. doi: 10.1111/jhn.12380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S., Sloan D., Evans H.E.R., Williams S. Improving the implementation of NICE public health workplace guidance: an evaluation of the effectiveness of action-planning workshops in NHS trusts in England. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2015;21:567–571. doi: 10.1111/jep.12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller I., Lang T., Keller I., Lang T. Food-based dietary guidelines and implementation: lessons from four countries–Chile, Germany, New Zealand and South Africa. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11:867–874. doi: 10.1017/s1368980007001115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenbach J.P. Re-thinking health inequalities. Eur. J. Public Health. 2020;30:2020. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckaa001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, L., Baum, F., Javanparast, S., O’Rourke, K., Carlon, L., O’Rourke, K., Carlon, L., 2015. Addressing social determinants of health inequities through settings: a rapid review. Health Promot. Int. 30, ii126–ii143. Doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav054. [DOI] [PubMed]

- NICE - National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2020. NICE Public Health Guidelines [WWW Document]. URL https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/published?type=ph.

- Noble H., Smith J. Reviewing the literature: Choosing a review design. Evid. Based. Nurs. 2018;21:39–41. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrand A., Fridlund B., Sollesnes R. Implementation of national guidelines for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: A phenomenographic analysis of public health nurses’ perceptions. Int. J. Qual. Stud. Health Well-being. 2016;11(1):31934. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.31934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popay, J., Povall, S.L., Whitehead, M., 2007. Community Engagement in Initiatives Addressing the Wider Social Determinants of Health: A Rapid Review of Evidence on Impact, Experience and Process, CE6&7 – 3 Social Determinants Effectiveness Review Executive.

- Rod M.H., Terp Høybye M. A case of standardization? Implementing health promotion guidelines in Denmark. Health Promot. Int. 2016;31:692–703. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dav026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman R.N., Dixon J., Brandt C., Essaihi A., Hsiao A., Michel G., Connell R.O. The GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA): development of an instrument to identify obstacles to guideline implementation. BMC Med. Informatics Decis. Mak. 2005;8:1–8. doi: 10.1186/1472-Received. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teunissen E., Gravenhorst K., Dowrick C., Van Weel-Baumgarten E., Van den Driessen Mareeuw F., de Brún T., Burns N., Lionis C., Mair F.S., O’Donnell C., O’Reilly-de Brún M., Papadakaki M., Saridaki A., Spiegel W., Van Weel C., Van den Muijsenbergh M., MacFarlane A. Implementing guidelines and training initiatives to improve cross-cultural communication in primary care consultations: a qualitative participatory European study. Int. J. Equity Health. 2017;16:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0525-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008;8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong A., Flemming K., McInnes E., Oliver S., Craig J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2012;12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torp S., Kokko S., Ringsberg K.C. Promoting health in everyday settings: Opportunities and challenges. Scand. J. Public Health. 2014;42:3–6. doi: 10.1177/1403494814553546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Muijsenbergh M., LeMaster J., Shahiri P., Brouwer M., Hussain M., Dowrick C., Papadakaki M., Lionis C., MacFarlane A. Participatory implementation research in the field of migrant health: Sustainable changes and ripple effects over time. Heal. Expect. 2020;23:306–317. doi: 10.1111/hex.13034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO - World Health Organization, 1986. WHO | The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. World Health Organization.

- Williams E., Mesidor M., Winters K., Dubbert P., Wyatt S. Overweight and Obesity: Prevalence, Consequences, and Causes of a Growing Public Health Problem. Curr. Obes. Rep. 2015;4:363–370. doi: 10.1007/s13679-015-0169-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]