Abstract

Introduction

Treatment advances for metastatic breast cancer (mBC) have improved overall survival (OS) in some mBC subtypes; however, there remains no cure for mBC. Considering the use of progression-free survival (PFS) and other surrogate endpoints in clinical trials, we must understand patient perspectives on measures used to assess treatment efficacy.

Objective

To explore global patient perceptions of the concept of PFS and its potential relation to quality of life (QoL).

Materials and methods

Virtual roundtables in Europe and the United States and interviews in Japan with breast cancer patients, patient advocates, and thought leaders. Discussions were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed thematically.

Results

Lengthened OS combined with no worsening or improvement in QoL remain the most important endpoints for mBC patients. Time when the disease is not progressing is meaningful to patients when coupled with improvements in QoL and no added treatment toxicity. Clinical terminology such as “PFS” is not well understood, and participants underscored the need for patient-friendly terminology to better illustrate the concept. Facets of care that patients with mBC value and that may be related to PFS include relief from cancer-related symptoms and treatment-related toxicities as well as the ability to pursue personal goals. Improved communication between patients and providers on managing treatment-related toxicities and addressing psychosocial challenges to maintain desired QoL is needed.

Conclusion

While OS and QoL are considered the most relevant endpoints, patients also value periods of time without disease progression. Incorporation of these considerations into the design and conduct of future clinical trials in mBC, as well as HTA and reimbursement decision-making, is needed to better capture the potential value of a therapeutic innovation.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Metastatic, Quality of life, Progression-free survival, Patient-centered, Qualitative research

Highlights

-

•

Overall survival benefit combined with good QoL are the most important endpoints for mBC patients.

-

•

Time without disease progression is meaningful to patients when coupled with no worsening in or improvements in QoL.

-

•

Quality of life is highly individual and evolves throughout the treatment journey.

-

•

Surrogate endpoints are confusing; more patient-centered language is needed.

-

•

Healthcare professionals should account for disease and psychological well-being.

1. Introduction

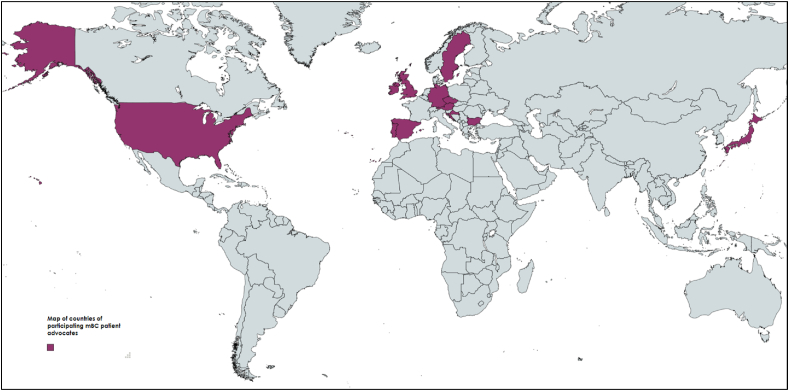

Breast cancer is the most common cancer diagnosed worldwide, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases in 2020 alone [1,2]. Incidence rates have historically been elevated in higher human development index (HDI) countries in North America and Western Europe, reflecting a longstanding prevalence of reproductive, hormonal, and lifestyle risk factors in these regions [3]. However, breast cancer incidence has been rising in high-income Asian countries like Japan, where rates have historically been low [2] (see Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Stakeholder countries represented.

Metastatic cancers, including distant metastases found at diagnosis (de novo) and those occurring later in the disease course (recurrent), are incurable, albeit treatable, and constitute the most advanced forms of the disease [4]. Since the 1990s, there have been several advancements in the management of metastatic breast cancer (mBC), but few have led to substantial increases in survival. Median overall survival (OS) in mBC is about 3 years, with variation by breast cancer subtype, patient characteristics, and access to treatment [[5], [6], [7]]. Between 1990 and 2010 alone, median OS among mBC patients increased from 21 months to 38 months [8]. However, recently reported data have demonstrated a trend of lengthened OS in specific types of mBC with certain therapies; for example the MONALEESA-2 (ML-2) phase III trial reported a statistically significant median OS of 63.9 months in HR+/HER2-negative mBC patients treated with front-line endocrine therapy (ET) ± ribociclib (RIB) [9].

While most stakeholders agree that OS is the gold standard in establishing the efficacy of oncology therapies, surrogate endpoints such as PFS have been consistently utilized as primary trial endpoints and OS as a secondary endpoint due to the longer time duration needed to reach OS results. In mBC trials conducted from 2000 to 2012, 60% of trials designated PFS as the primary endpoint, compared to 24% that used OS [10].

Due to the ubiquity of its use as a surrogate endpoint, it is useful to investigate the relationship of surrogate metrics such as PFS with other measures of treatment efficacy, including quality of life (QoL) and symptom burden; and understand the value of these endpoints, if any, to patients living with mBC in their day-to-day lives. Previous work has begun to shed light on the relationship between PFS and treatment efficacy. In a discrete choice experiment survey study of mBC patients and providers who treat such individuals, MacEwan et al. reported that patients preferred treatments that conferred contiguous periods of PFS, although more research was warranted to understand the reasons for PFS having a positive value [11]. Another study examining patient preferences for chemotherapy in mBC found that patient's age, relationship status and travel time to treatment was significantly associated with preferences for PFS. Yet, in a rapidly evolving treatment landscape, more work is needed [12].

Navigating cancer treatment remains daunting for patients and its impact on QoL is well-documented [13]. Specifically, a review of the trends in QoL for mBC indicates that there has not been a significant improvement in patient QoL since 2004 [6]. Patients with mBC may also have different treatment and survival priorities than patients living with earlier stage disease [14]. Furthermore, disease progression, recurrence, and death remain the greatest fear among patients with mBC [15].

Facing treatment-related decisions in addition to facing an incurable illness that requires continuous treatment can introduce great psychosocial distress for both the patient and their loved ones [[16], [17]]. Yet, in clinical trials for patients with mBC, patient experience and quality of life may be overlooked, despite evidence that treatment confers impact. For example, a 2016 review of the use of patient-reported outcomes (PROs) in mBC clinical trials found that 39% of publications reported deterioration in PRO outcomes from baseline [18]. Another review conducted by the Setting International Standards in Analyzing Patient Reported Outcomes and Quality of Life Endpoint Data for Cancer Clinical Trials (SISAQOL) Consortium found that just 12% of breast cancer trials that assessed PRO data included a specific PRO research hypothesis [19]. A more comprehensive understanding on QoL impacts in specific mBC populations, such as elderly individuals, whose treatments are often modified from guidelines established for younger patients, are critically needed. For example, prior research has also demonstrated that in older adults living with breast cancer, chemotherapy has both a clinically and statistically significant negative impact across several QoL domains [20]. Yet, well-recognized and critically needed population specific considerations, such as those recently updated in guidance by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) and European Society of Breast Cancer Specialists (EUSOMA), are often unaccounted for in the conduct of clinical trials [21]. Such considerations for older adults with breast cancer include geriatric assessments, competing risks of mortality due to comorbidities, and patient preferences. [21].

In this study, we sought to explore global patient perceptions of and experiences with the concept of PFS, including its consideration in treatment decision-making and its impact on patients’ daily lives. We convened roundtables and conducted interviews with mBC patients and patient advocates representing key advocacy organizations in Europe, Japan, and the United States, and performed qualitative data analysis to identify and synthesize key themes across the discussions.

This article provides a collective summary of participant perspectives on the value of PFS in relation to QoL and activities of daily living in mBC.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Study design and data collection

In preparation for the roundtables and interviews, we conducted a targeted review of the literature. We included studies published between 2010 and 2020 describing mBC patient preferences for surrogate survival endpoints and treatment as related to QoL, productivity impacts, and caregiver burden.

We collaborated with the European Cancer Patient Coalition (ECPC) for participant recruitment in Europe, and the Metastatic Breast Cancer Network (MBCN) and SHARE Cancer Support for recruitment in the United States. In both Europe and the United States, ECPC and MBCN and SHARE identified and issued e-mail invitations to English language proficient members of their constituencies to assess interest in participation. Interested participants were directed to a designated contact at the participating partner organization to coordinate availability for the scheduled roundtables that were being conducted in English. In Japan, we approached three prominent patient advocacy organizations (Cancer Survivors Recruiting Project, Cancer Solutions, and Japan Association of Medical Translation for Cancer) and invited their participation in individual in-depth interviews to capture Japanese patient perspectives. In advance of the roundtables and interviews, all participants were provided a pre-read packet with background on the literature review conducted and roundtable or interview discussion questions.

Roundtable and interview discussion topics were divided into segments and all questions were posed to patients, patient advocates, and healthcare professionals. Discussion questions (Table 1) were developed based on concepts identified in the published literature, identified gaps, and in consultation with representatives from the ABC Global Alliance, ECPC, MBCN and SHARE. In this paper, we predominantly report findings from the Treatment-related quality of life and Perspectives on PFS terminology domains, although also report limited findings from the other domains as relate to both.

Table 1.

Discussion questions.

| Domain | Questions |

|---|---|

| Treatment decision-making and preferences |

|

| Treatment-related quality of life |

|

| Perspectives on PFS terminology |

|

| Productivity impacts and financial toxicity |

|

| Caregiver burden |

|

We convened virtual roundtables in Europe (October 2020) and the United States (January 2021) and virtual in-depth interviews in Japan (February 2021). Interviews were conducted as an alternative to roundtables in Japan due to differences in communication styles in East Asia, particularly around potentially sensitive subjects such as cancer. Discussants and interviewees included mBC patients, mBC patient advocates, and/or healthcare professionals. Roundtables and interviews were moderated by study team members with graduate training in qualitative data collection. Discussions were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, supplemented with observational field notes recorded by study team members. The roundtables in Europe and the United States were conducted in English and interviews in Japan were conducted in both Japanese and English, with an interpreter present for live translation.

2.2. Data analysis

Transcripts and chatlogs were imported into Dedoose, a qualitative data analysis software program (Version 8.0.35), to facilitate analysis. We developed a codebook based on discussion guide topics and a review of the transcripts. Codes were further refined by the team into descriptive categories, resulting in a dictionary of eighteen thematic codes based on discussion topics and inductive generation. Data were analyzed individually by five members of the study team with graduate training in qualitative data analysis (SGM, KT, KB, MR, SM). We analyzed similarities and differences in participant discussions of their perspectives on and experiences with treatment decision making, tradeoffs and quality of life impacts, using the constant comparative method [22,23]. For the purposes of this paper, we focus our analyses on discussions related to the concept of PFS and its relationship to QoL for patients with mBC.

3. Results

Thirty individuals participated in the virtual roundtables and interviews, representing twenty-six breast cancer advocacy organizations from across thirteen countries. Participants included metastatic breast cancer patients (n = 16), breast cancer patient advocates (n = 12), and breast cancer oncologists (n = 2) who represented a wide range of experiences in mBC.

3.1. Overall survival benefit combined with good QoL remain the most important endpoints for patients with mBC

Consistent with the peer-reviewed literature, participants noted that the single most important endpoint for patients living with mBC is simply living longer. Among our participants, there can be no dispute that patients living with mBC desire to live as long as possible with a good QoL. Although OS is utilized as a clinically meaningful endpoint to gauge the overall efficacy of a given treatment, patients have a much more holistic view of its impact. For patients living with an incurable disease, gains in OS (and to a lesser extent PFS) provide an opportunity to access new and better treatments, particularly when treatment regimens stop being effective. Thus, the gold standard of endpoints for patients is OS because it gives patients more time to live, and potentially more time to live with a good QoL.

3.2. What quality of life means to a patient with mBC

Moderators directly queried participants about what QoL means to patients with mBC and asked them to share their experiences and perspectives around treatment-related QoL. Participants indicated that they valued treatment that could help with maintaining as “normal” a life as possible and the ability to retain independence and overall functioning. Participants from all regions generally agreed that symptom burden associated with breast cancer and its treatment can significantly impact QoL. In the metastatic setting, maintaining, and improving QoL was particularly important due to the incurable nature of the disease and the long-term nature of treatment. Participants described QoL as being able to function as close to a pre-diagnosis normal as possible, including working, spending time with family and friends, and maintaining daily activities with minimal disruption. Treatments that contribute to minimizing disruption – such as oral treatments versus painful intramuscular or time-consuming intravenous treatment that require travel to and time at clinics – are preferred. Multiple participants also agreed that pain and fatigue often led to the most detrimental impacts to QoL. Select narrative quotes that illustrate patient perspectives on QoL are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Exemplar narratives from participants on quality of life.

| Topic | Exemplar Narrative |

|---|---|

| What quality of life (QoL) means for patients with mBC | “So quality of life is very important. In particular, as for metastatic breast cancer patients, there's no cure. So the focus becomes how long they extend their life, what kind of treatment is available to extend their life. So when you think about that, getting a very strong treatment, but when you -- can't get out of bed, is that a good quality of life? No. It's, rather, what they think is, by continuing the treatment, but they want to live the way they have lived, and they want to have a future, think about the future as well.“- Japanese Interview Participant |

| “I think quality of life is very important, and quality of life, certainly, isn't always the same for all patients. I think it means not having too many side effects or at least a good management of side effects and, also, how I can manage my daily life. Can I take care of my children? Can I still go to work or work and fulfill my daily tasks at home? Things like that. I think these two parts are very, very important.” – ECPC Participant | |

| Aspects of treatment that strongly impact QoL for patients with mBC |

“So many people with mBC that I work with have ongoing, untreated pain, and it impacts their day-to-day life significantly. It impacts them physically, mentally, emotionally.” – MBCN/SHARE Participant “And if you lose hair, you can use a wig, for instance, and other things can be dealt with somehow. But according to the patients that I've seen also, to them, when they are fatigued and feel lethargic, that's a very major issue for their life.” – Japan Interview Participant “If you want to keep up your daily life and you cannot move, it's not easy to wash yourself, to do your daily things, to get out … it's really hard to … tackle it because, very often, it doesn't go away. They can't think anymore. They can't do things anymore because they're just [in] pain.” – ECPC Participant |

| QoL is individualized and dynamic | “With mBC there is a certain “toll” that I think most patients recognize they will pay – [be] it neuropathy, fatigue, etc. Maintaining a base QOL is very important, yet the level of QOL will be very individualistic.” – MBCN/SHARE Participant |

| “I'd like to say that quality of life is very age specific. My breast cancer was not the same as my mother's breast cancer primarily because I was originally diagnosed with the early stage at age 31 and then with metastatic at age 44. At 31, I was trying to maintain a career. I was single. I was still dating. At age 44, I had a two-year-old at home. I was midcareer. I was looking at a promotion to director. My mother, who almost had the same trajectory but was 20 years older, had a completely different set of priorities. Going to the opera was important to her, but she didn't have a full schedule. She didn't have a toddler at home.” - MBCN/SHARE Participant | |

| Mode of treatment administration | “So many patients appreciate oral medication … IV treatment takes time and is very time consuming, and yet time has to be given for that treatment. You have to give up time for the treatment.” – Japan Interview Participant |

| Educating providers on QoL | “I remember when I was being treated and I saw five different consultants. Not one of them ever asked me what I did for my job. Not one of them had any interest in my life outside of the immediate hospital or clinic where I was being seen.” –ECPC Participant |

| “I also think it's important to bring in quality of life concerns in the treatment presentation and options because I have run into many patients where they have decided to just forgo [i.e. stop] treatment altogether because of those quality-of-life concerns and thinking it's just gonna be too disruptive to my life, I'd rather not even take it on.” – MBCN/SHARE Participant |

Participants noted that QoL can vary by life circumstances, situations (e.g., career focus, parenthood, retirement), and types of desired activities (e.g., exercise, travel). They described that even within the same patient, QoL is a dynamic construct that is constantly changing throughout the treatment journey, and that priorities and tolerance for disruption to their daily lives can change over time. Therefore, it is important that the impact of the disease and treatment on QoL is discussed regularly during visits with healthcare professionals. Participants highlighted the need to educate providers on viewing patients holistically, taking the time to understand individual patient needs and preferences and considering a treatment's potential impact on QoL when making treatment recommendations. They also stressed that these issues should be assessed on an ongoing basis, as what matters to patients can change based on their life situation.

3.3. The concept of “progression-free survival” for patients with mBC

Living longer is the priority for patients with mBC, and the time when disease is not progressing is meaningful when coupled with improvements in QoL and no added treatment toxicity. Participants were first asked to review clinical definitions for “PFS” and “stable” disease and asked to discuss their perspectives around patient understanding of these terms. Participants noted that the term “PFS” was a confusing mixture of words, and that patients would only hear the “survival” component. They suggested the term be replaced with a more patient-friendly, patient-centered term that meaningfully conveys the concept of PFS, or periods of time where the disease is not growing or spreading (e.g., “time without disease progression”). Even breast cancer patient advocates, who are often more familiar with clinical terminology than the average patient, expressed confusion around the term.

Participants agreed that oncologists seldom ask patients about their primary concerns, and do not adequately explain the disease or full scope of treatment options and considerations specific to their case. Rather than quoting clinical data, providers should ask patients about their primary concerns and explain the full disease scope as well as available treatment options.

Ultimately, while participants felt that PFS and/or periods of time where the disease is not growing or spreading could be important to patients, they noted that gains in PFS should not be at the expense of worsened QoL and/or should relieve cancer-related symptoms. It is within this context that PFS can be valued, putting the concept into perspective with other clinical endpoints such as OS and QoL while explaining the benefits and risks of treatment options.

Lastly, participants emphasized the need to deliver messaging around PFS at the appropriate time in the treatment journey. Participants across all regions noted that discussion of clinical endpoints such as PFS at diagnosis of metastatic disease or immediately following diagnosis is overwhelming for even the most educated patients. Patients are still processing the diagnosis and its impact and disruption to their lives and cannot think about endpoints such as PFS.

3.4. The value of progression-free survival for mBC patients and their caregivers

Participants were also asked to describe how patients with mBC view PFS and the time periods when the disease is not spreading or growing, and in what manner these periods may contribute to improved QoL. Despite the confusing nature of these terms, patients intuitively connected PFS and times when the disease is not spreading or growing to gains in QoL. As shown in the narrative excerpts in Table 3, participants noted that patients do not view these time periods as defined clinically, but rather about how these periods shape their ability to carry out daily activities, accomplish goals and deepen their personal relationships. This can include traveling, spending time with friends and family, and becoming more active in their communities.

Table 3.

Exemplar Narratives from Participants on the Value of PFS Associated with Good QoL for mBC Patients and their Families.

| Topic | Exemplar Narrative |

|---|---|

| Importance of progression-free periods for patients with mBC | “That time is extremely important for patients. The mind and the body are connected. So when you're feeling good about your body, your body feels good. You'll have higher motivation, and you want to do more. And the progression-free time period, there are people who create lists of things that they want to do … And that progression-free time period is extremely important for them. It's a very concentrated time, the time period they want to utilize to the maximum.” - Japan Interview Participant |

| “Me, as a patient, I'm not thinking in terms of is the tumor shrinking from this size to another or is it stable and not growing? As long as it doesn't impact my daily life, my family life, I would prefer to have it stable instead of shrinking.” – ECPC Participant | |

| Maintain some sense of normalcy, including working |

“The grief people experience from losing their jobs and careers is immense. People with metastatic breast cancer want to contribute to the world and they can contribute to the world, but most people do not understand this because they don't understand metastatic cancer.” – MBCN/SHARE “Prior to me being a cancer patient, I always saw on the news and read that, ‘Oh, 1 in 12 cancer patients is filin’ for bankruptcy. There's a lot of financial toxicity.’ Insurance is everything. My insurance is through my employer and also covers my husband's care, who is two-time cancer survivor and my kids. I just thought that it was really important for me to try to stay working as long as possible.” - MBCN/SHARE Participant “I think one of the things in the Black community is that we don't always talk about our diseases with our families. We often hide it. A lot of moms will hide it from their families because they're the breadwinner. I think [NAME] mentioned the fact earlier, 77.3[%] of Black moms are single moms. If you add any disease to that, it's a very difficult situation. I think that caregiving is a whole ‘nother conversation, I think, in the Black household where the mom is the sole breadwinner and has young kids and has to take care of them ‘cause she really has no one.” – MBCN/SHARE Participant |

| Impact of disease and treatment on caregivers | “I think that's an enormous area where people need support, particularly the case for parents with young children where they need to be in hospital all the time. I think carers, particularly at work, have an issue. I'll say the second point is about their own physical and mental health, very often, is something that is put to one's side. If carers don't look after themselves, they can't look after the person they're supposed to be caring for properly.” – ECPC Participant |

| “I don't know if it's Japanese culture, but many people feel very resistant to let the others know what's going on inside the house, inside the family. So, for that reason, they do not want to bring in outsiders into their home environment. Therefore, there are quite a few people who do not want to have professional caregivers to come in and help in the home setting. That means that the family members, the limited number of family members, will have to carry more burden.” – Japan Interview Participant |

Participants described how such periods of time – when associated with no worsening in or improved QoL – allow patients to resume or maintain some sense of normalcy and independence, including continuing to work. For many patients, employment is often tied to health insurance coverage [in the US] and/or to salary for out-of-pocket expenses, creating a necessity for patients with mBC to be able to work for as long as possible.

Finally, the value of these periods of time when the disease is not growing or spreading and associated with no worsening in or improved QoL extends beyond patients and can provide benefit for caregivers and a reprieve from the potential burden of caregiving for a cancer patient. More generally, participants noted the need to develop resources to support caregivers and identified this as an important and critical unmet need. In Japan in particular, a cancer diagnosis can be stigmatizing, leaving family members to bear the burden of caregiving alone without external support.

4. Discussion

This study sought to better understand mBC patient perceptions of and experiences with the concept of PFS and periods of time where a cancer is not growing or spreading, including its consideration in treatment decision-making and impact on QoL. Consistent with the published literature, participants agreed that improved or maintained QoL is an important endpoint [24,25], although how a patient defines good QoL can vary by age, time since diagnosis, type of treatments received, and life circumstances. Even within an individual patient, QoL is a dynamic construct that evolves throughout the treatment journey [26].

Notwithstanding the above, participants emphasized that OS remains the most important outcome for the mBC patient, closely followed by QoL. To be meaningful for patients, improvements in PFS and time periods without tumor growth or spread must be accompanied by no worsening in or improved QoL and symptom control, and/or decreased treatment toxicity.

This study also identified gaps in communication about PFS between mBC patients and their care team. For most patients, PFS is unfamiliar as a term and a difficult concept to grasp. If even discussed, it is often not properly explained or contextualized for patients with participants noting that patient-physician dialogue surrounding PFS, QoL, and other endpoints merit substantial improvement. Put simply, few patients understand the concept of “progression-free survival”; the term elicits confusion, with many patients focusing exclusively on the word “survival” and conflating it with “overall survival”. Thus, more patient-friendly terminology is needed. Previous research has also shown that clinical trial language is oftentimes not comprehensible to patients [27]. This situation is further compounded by an abundance of literature documenting the negative impacts of poor patient and provider communication in oncology care delivery, although recent studies suggest that when providers focus on patient priorities, communication and patient outcomes can significantly improve [[28], [29], [30], [31], [32], [33], [34]].

Towards that end, many studies have documented the misaligned considerations of oncologists and patients, with providers often focused on tumor response and managing side effects while potentially ignoring important concerns for patients such as treatment-related financial toxicity, personal goals, and family dynamics [[35], [36], [37], [38], [39]]. We also found that patients would prefer their physician to take a more holistic approach to care by considering individual circumstances and QoL impact when discussing treatment options. While survival and treatment efficacy remain key considerations, participants shared that over the course of their treatment journey, patients increasingly valued freedom from pain, the ability to engage in daily activities without fatigue, and absence of financial stressors. Downstream effects of treatment such as late emerging and chronic side effects can also confer significant impacts on long-term QoL [40].

These discussions underscore the importance of consistently incorporating comprehensive QoL measures as an endpoint in breast cancer clinical trials and developing novel PRO instruments specifically for mBC. Findings from our study – whereby participants placed great emphasis on maintaining good QoL during their mBC treatment journey further support this critical unmet need. Particularly in the mBC setting, there is a need for increased emphasis on QoL in the evaluation of cancer therapies - with a treatment's potential efficacy and survival benefit carefully considered alongside its toxicities and impact on QoL. Although investigating quality of life may not be the primary goal of a clinical trial, the integration of QoL metrics as (co)-primary endpoints, rather than as a secondary endpoint as is often the case, is needed order to assess the benefits and risks of new cancer agents more holistically.

Lastly, participants believed emphatically that any treatment offering PFS gains should not worsen QoL, and it was noted that periods of time where disease is not growing or spreading may be able to provide some QoL benefits such as symptom relief, prolonged ability to work (which may ameliorate financial concerns), and the pursuit of personal goals such as traveling or participating in meaningful family events. This is consistent with a new concept of treatment-related time toxicity recently posited by Gupta et al. whereby patients may value treatments differently if they knew precisely how much time they would need to spend pursuing cancer-directed therapy that would disrupt normal activities of daily living and negatively impact QoL relative to gains in survival or day-to-day functioning [41].

These findings emphasize the complexities of treatment decision-making and highlight how the value of all endpoints needs to be communicated in relatable and tangible terms to patients. Further, while perspectives on QoL were generally consistent across regions, some region-specific considerations in treatment decision-making were noted. In the US and Europe, patients have more autonomy in treatment decision-making. However, countries like Japan still operate under a more paternalistic health care system whereby patient autonomy is considered within the context of the triadic relationship of patient, family, and physician [[42], [43], [44]]. Women, in particular, have limited autonomy in decision-making, combined with a culture that prioritizes deference to doctors and to the male head of household. However, Japanese participants noted that with the younger generation, the landscape is evolving.

This study has several limitations. First is a sample size of 30 participants; while by established qualitative research guidelines [45] this is deemed sufficient to provide the necessary diversity of opinion and experiences and to confirm and validate shared views, we acknowledge that these findings may not be generalizable to the broader mBC patient population. In addition, although we were able to capture diverse perspectives across different regions, we recognize that this does not fully capture the heterogeneity of the mBC patient population. Specifically, patient perspectives on various themes that emerged during the discussion may differ by demographic characteristics, including those related to social determinants of health, which we were not able to address given the smaller sample size. Lastly, as this study was focused on capturing the perspectives and opinions of patients themselves, we did not include the perspectives of oncology care nurses. We note the large body of published evidence highlighting the role of oncology nurses in patient care, and in particular their sensitivity to the impact of disease and treatment on patient health and well-being. Future work exploring this subject would benefit from inclusion of oncology nurse perspectives [[46], [47], [48]].

Although mBC remains an incurable disease, the changing treatment landscape has led to slow but consistent improved outcomes for many patients, especially for HER2+ and ER + subtypes. Patients desire treatments that help them to live longer with good QoL. In the absence of a cure for mBC, our work further highlights the need for better communication between patients and healthcare professionals on treatment decision-making to manage toxicities and maintain/improve QoL. Further research is needed to better understand how mBC patients make treatment decisions over time, such as avoiding treatment toxicities and valuing periods of time that cancer is not spreading relative to other treatment attributes.

5. Conclusion

While overall survival is considered the most important endpoint, patients also value periods of time without disease progression, as long as quality of life during this time period is not adversely impacted. There remains an unmet need for more patient-centered clinical terminology for PFS (such as time without disease progression), more holistic care throughout the treatment journey, and a greater focus on the dynamic construct of QoL. Incorporation of these considerations into the design and conduct of future clinical trials in mBC, as well as HTA and reimbursement decision-making, is needed to better capture the potential value of a therapeutic innovation beyond clinical endpoints, as such endpoints must also be meaningful from the patient's perspective.

Funding disclosure

This manuscript was sponsored by Sanofi, United States. The roundtables and interviews which inspired the development of this article were also funded by Sanofi, United States. None of the authors received honoraria to write this article.

Author disclosure

Shirley Mertz, Christine Benjamin, Charis Girvalaki, Antonella Cardone, and Paulina Gono report no conflict of interest. Suepattra G. May, Kyi-Sin Than, Kelly Birch, Meaghan Roach, and Sky Myers are or were employees of PRECISIONheor, a consulting firm that received funding from Sanofi in relation to this project. Suepattra G. May owns equity interest in PRECISIONheor's parent company, Precision Medicine Group.

Medha Sasane, Liat Lavi, Erin Comerford and Anna Cameron are employees of Sanofi and may hold Sanofi stock.

Fatima Cardoso has personal financial interest in form of consultancy role for: Amgen, Astellas/Medivation, AstraZeneca, Celgene, Daiichi-Sankyo, Eisai, GE Oncology, Genentech, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, IQVIA, Macrogenics, Medscape, Merck-Sharp, Merus BV, Mylan, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre-Fabre, prIME Oncology, Roche, Sanofi, Samsung Bioepis, Seagen, Teva, Touchime.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the roundtables and interviews for their time and thoughtful insights, and the many women living with mBC who contributed significantly to this research through their direct participation in this study and in studies that this work references.

References

- 1.Cancer facts & figures 2021. American Cancer Society; Atlanta: 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3) doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bray F., McCaron P., Parkin D.M. The changing global patterns of female breast cancer incidence and mortality. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(229) doi: 10.1186/bcr932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariotto A.B., Etzioni R., Hurlbert M., Penberthy L., Mayer M. Estimation of the number of women living with metastatic breast cancer in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2017;(6):26. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sundquist M., Brudin L., Tejler G. Improved survival in metastatic breast cancer 1985-2016. Breast. 2017;31:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2016.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cardoso F, Spence D, Mertz S, et al. Global analysis of advanced/metastatic breast cancer: decade report (2005–2015). Breast 2018;39:131–138. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Kobayashi K., Ito Y., Matsuura M., et al. Impact of immunohistological subtypes on the long-term prognosis of patients with metastatic breast cancer. Surgery today. 2016;46(7):821–826. doi: 10.1007/s00595-015-1252-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caswell-Jin J.L., Plevritis S.K., Tian L., et al. Change in survival in metastatic breast cancer with treatment advances: meta-analysis and systematic review. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2018;(4):2. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pky062. pky062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hortobagyi G.N., Stemmer S.M., Burris H.A., et al. LBA17 Overall survival (OS) results from the phase III MONALEESA-2 (ML-2) trial of postmenopausal patients (pts) with hormone receptor positive/human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 negative (HR+/HER2−) advanced breast cancer (ABC) treated with endocrine therapy (ET) ± ribociclib (RIB) Ann Oncol. 2021;32:S1290–S1291. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaklamai V. Clinical implications of the progression-free survival endpoint forTreatment of hormone receptor-positive advanced breast cancer. Oncol. 2016;21:922–930. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacEwan J.P., Doctor J., Mulligan K., et al. The value of progression-free survival in metastatic breast cancer: results from a survey of patients and providers. MDM Policy Pract. 2019;4(1) doi: 10.1177/2381468319855386. 2381468319855386–2381468319855386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Spaich S., Kinder J., Hetjens S., Fuxius S., Gerhardt A., Sütterlin M. Patient preferences regarding chemotherapy in metastatic breast cancer—a conjoint analysis for common taxanes. Front Oncol. 2018:8. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mokhtari-Hessari P., Montazeri A. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients: review of reviews from 2008 to 2018. Health Qual Life Outcome. 2020;18(1):338. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Current approaches and unmet needs in the treatment of metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. AJMC. 2021;27(5 Suppl):S87–S96. doi: 10.37765/ajmc.2021.88626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cancer support community. 2020. Patient insights: 2020 cancer experience registry report. Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaufman P, al. e Patient-reported outcomes (PRO) in patients with metastatic breast cancer (MBC) from the VIRGO observational cohort study (OCS) J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(27):111. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reed E., Simmonds P., Haviland J., Corner J. Quality of life and experience of care in women with metastatic breast cancer: a cross-sectional survey. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2012;43(4):747–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner-Bowker D.M., Hao Y., Foley C., et al. The use of patient-reported outcomes in advanced breast cancer clinical trials: a review of the published literature. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016;32(10):1709–1717. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2016.1205005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pe M., Dorme L., Coens C., et al. Statistical analysis of patient-reported outcome data in randomised controlled trials of locally advanced and metastatic breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(9):e459–e469. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30418-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Battisti N.M.L., Reed M.W.R., Herbert E., et al. Bridging the Age Gap in breast cancer: impact of chemotherapy on quality of life in older women with early breast cancer. European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 2021;144:269–280. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2020.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biganzoli L., Wildiers H., Oakman C., et al. Management of elderly patients with breast cancer: updated recommendations of the international society of geriatric oncology (SIOG) and European society of breast cancer Specialists (EUSOMA) Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(4):e148–e160. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70383-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glaser B.G., Strauss A.L. Transaction Publishers; 2009. The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gubrium J.F., Holstein J.A. Sage; 2002. Handbook of interview research: context and method. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MSv Itzstein, Railey E., Smith M.L., et al. Patient familiarity with, understanding of, and preferences for clinical trial endpoints and terminology. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 2020;126(8):1605–1613. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen J.T., Anderson J.E., Neumann P.J. Three sets of case studies suggest logic and consistency challenges with value frameworks. Value Health : the journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research. 2017;20(2):193–199. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mortesen G.L., Madsen I., Krogsgaard R., Ejlertsen B. Quality of life and care needs in women with estrogen positive metastatic breast cancer: a qualitative study. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(1):146–151. doi: 10.1080/0284186X.2017.1406141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mv Itzstein, ailey E., Smith M., et al. Patient familiarity with, understanding of, and preferences for clinical trial endpoints and terminology. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1605–1613. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thorne S., Hislop T.G., Kim-Sing C., Oglov V., Oliffe J.L., Stajduhar K.I. Changing communication needs and preferences across the cancer care trajectory: insights from the patient perspective. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(4):1009–1015. doi: 10.1007/s00520-013-2056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorne S.E., Stajduhar K.I. Patient perceptions of communications on the threshold of cancer survivorship: implications for provider responses. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(2):229–237. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0216-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeuner R., Frosch D.L., Kuzemchak M.D., Politi M.C. Physicians' perceptions of shared decision-making behaviours: a qualitative study demonstrating the continued chasm between aspirations and clinical practice. Health Expect : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy. 2015;18(6):2465–2476. doi: 10.1111/hex.12216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arora N.K. Interacting with cancer patients: the significance of physicians' communication behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(5):791–806. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00449-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCormack L.A., Treiman K., Rupert D., et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(7):1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohile S.G., Epstein R.M., Hurria A., et al. Improving communication with older patients with cancer using geriatric assessment (GA): a University of Rochester NCI Community Oncology Research Program (NCORP) cluster randomized controlled trial (CRCT) J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(18_suppl) LBA10003-LBA10003. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shih Y.-C.T., Chien C.-R. A review of cost communication in oncology: patient attitude, provider acceptance, and outcome assessment. Cancer. 2017;123(6):928–939. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rocque G., Rasool A., Williams B, al. e What is important when making treatment decisions in metastatic breast cancer? A qualitative analysis of decision-making in patients and oncologists. Oncol. 2019;24(10):1313–1321. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fallowfield L.J. Treatment decision-making in breast cancer: the patient–doctor relationship. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;112(1):5–13. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lux M.P., Bayer C.M., Loehberg C.R., et al. Shared decision-making in metastatic breast cancer: discrepancy between the expected prolongation of life and treatment efficacy between patients and physicians, and influencing factors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139(2):429–440. doi: 10.1007/s10549-013-2557-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thiel F.C., Schrauder M.G., Fasching P.A., et al. Shared decision-making in breast cancer: discrepancy between the treatment efficacy required by patients and by physicians. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;135(3):811–820. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2218-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brom L., Snoo-Trimp J.C.D., Onwuteaka-Philipsen B.D., Widdershoven G.A.M., Stiggelbout A.M., Pasman H.R.W. Challenges in shared decision making in advanced cancer care: a qualitative longitudinal observational and interview study. Health Expect. 2017;20(1):69–84. doi: 10.1111/hex.12434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yousuf Zafar S. Financial toxicity of cancer care: it's time to intervene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2016;108(5) doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gupta A., Eisenhauer E.A., Booth C.M. The time toxicity of cancer treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(15):1611–1615. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.02810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishikawa H., Yamazaki Y. How applicable are western models of patient-physician relationship in Asia?: changing patient-physician relationship in contemporary Japan. Int J Jpn Sociol. 2005;14(1):84–93. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pun J.K.H., Chan E.A., Wang S., Slade D. Health professional-patient communication practices in East Asia: an integrative review of an emerging field of research and practice in Hong Kong, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Mainland China. Patient Educ Counsel. 2018;101(7):1193–1206. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Matusitz J., Spear J. Doctor-patient communication styles: a comparison between the United States and three asian countries. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2015;25(8):871–884. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vasileiou K., Barnett J., Thorpe S., Young T. Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(148) doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Granek L., Nakash O., Ariad S., Shapira S., Ben-David M.A. Oncology health care professionals' perspectives on the causes of mental health distress in cancer patients. Psycho Oncol. 2019;28(8):1695–1701. doi: 10.1002/pon.5144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.H SC. Pai M.S., Fernandes D.J. Oncology nurse navigator programme - a narrative review. Journal of Health and Allied Sciences NU. 2015;5(1):103–107. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu F.X., Witt E.A., Ebbinghaus S., DiBonaventura Beyer G., Basurto E., Joseph R.W. Patient and oncology nurse preferences for the treatment options in advanced melanoma: a discrete choice experiment. Cancer Nurs. 2019;42(1) doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]