Abstract

Background

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a gaseous signaling molecule that impacts multiple physiological processes including aging, is produced via select mammalian enzymes and enteric sulfur-reducing bacteria. H2S research is limited by the lack of an accurate internal standard-containing assay for its quantitation in biological matrices.

Methods

After synthesizing [34S]H2S and developing sample preparation protocols that avoid sulfide contamination with the addition of thiol-containing standards or reducing reagents, we developed a stable isotope-dilution high performance liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method for the simultaneous quantification of Total H2S and other abundant thiols (cysteine, homocysteine, glutathione, glutamylcysteine, cysteinylglycine) in biological matrices, conducted a 20-day analytical validation/normal range study, and then both analyzed circulating Total H2S and thiols in plasma from 400 subjects, and within 20 volunteers before and after antibiotic-induced suppression of gut microbiota.

Results

Using the new assay, all analytes showed minimal interference, no carryover, and excellent intra- and inter-day reproducibility (≤7.6%, and ≤12.7%, respectively), linearity (r2 > 0.997), recovery (90.9%–110%) and stability (90.0%–100.5%). Only circulating Total H2S levels showed significant age-associated reductions in both males and females (p < 0.001), and a marked reduction following gut microbiota suppression (mean 33.8 ± 17.7%, p < 0.001), with large variations in gut microbiota contribution among subjects (range 6.0–66.7% reduction with antibiotics).

Conclusions

A stable-isotope-dilution LC-MS/MS method is presented for the simultaneous quantification of Total H2S and multiple thiols in biological matrices. We then use this assay panel to show a striking age-related decline and gut microbiota contribution to circulating Total H2S levels in humans.

Keywords: Hydrogen sulfide, Gut microbiota, Aging, Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, Plasma thiol, Cysteine, Homocysteine, Glutathione, Cysteinylglycine, γ-glutamylcysteine, Microbiome

Highlights

-

•

We describe the first stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS assay for hydrogen sulfide.

-

•

Systemic H2S levels are reduced with aging in both men and women.

-

•

Gut microbes significantly contribute H2S levels in subjects.

-

•

There is large variation in gut microbiota contribution to H2S levels in subjects.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), a gaseous molecule with presumed links to aging, is produced by both mammalian cells and sulfur-reducing enteric commensals. Here, [34S]Na2S was synthesized as internal standard and used to develop a stable isotope-labelled liquid-chromatography-tandem-mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous quantification of Total H2S and thiols in biological matrices. Beyond normal range studies, plasma H2S and six abundant thiols were examined in a clinical cohort (n = 400), and in subjects before and after suppression of gut microbiota. Total H2S levels were significantly reduced with aging, and gut microbiota contribution to circulating Total H2S was shown to vary significantly between subjects.

Abbreviations

- H2S

Hydrogen sulfide

- [34S]H2S

heavy isotope labelled hydrogen sulfide

- EIA

ethyl iodoacetate

- DETA

2,2’-diethyl thiodiacetate

- DMTA

2,2’-dimethyl thiodiacetate

- DTA

dithiodiacetate

- TCEP

tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- DTPA

diethylenetriamine pentaacetate

- ESI

electrospray ionization

- MRM

multiple reaction monitoring

- HPLC

high-performance liquid chromatography

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry

- IS

internal standard

- CID

collision induced dissociation

- Abx

antibiotics

- QC

quality control

- RT

retention time

- SAM

standard addition method

- NO

nitric oxide

- CO

carbon monoxide

- CSE

cystathionine γ-lyase

- CBS

cystathionine β-synthase

- GSH

glutathione

- 3-MST

3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase

- SRB

sulfate-reducing bacteria

1. Introduction

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is an endogenously produced gaseous signaling molecule that plays important physiological roles in human health [1]. In mammals, three distinct enzymes are known to produce H2S: cystathionine γ-lyase (CSE), cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfur transferase (3-MST) [[2], [3], [4]]. H2S can also be produced by enteric sulfur-reducing bacteria [5]. Methods for quantifying H2S often rely on measuring H2S production following sample incubation, as opposed to the levels of H2S present at time of sample collection. Equally important, the relative contribution of host versus gut microbiota to overall systemic H2S levels in humans is unknown.

Many studies have shown that H2S possesses significant biological activities including a role in aging [[6], [7], [8], [9]]. For example, H2S reportedly protects cardiomyocytes against hypoxic injury in culture, and in animal models of cardiac and limb ischemia reperfusion injury [10,11]. Other studies have noted dramatic effects of H2S on mitochondrial respiration, tissue preservation, hibernation, circadian rhythm, metabolism, and related functions [[12], [13], [14]]. Human studies have reported clinical associations between H2S and aging [8,9], cardiovascular disease [15,16], and other degenerative diseases [17]. These studies typically measure H2S by assessing sulfide concentration without internal standards, or H2S production capacity by incubating the sample after collection [18,19].

Despite the role of H2S in numerous physiological processes and diseases, methods for measuring H2S are limited by many factors, including: difficulties in quantifying a volatile molecule, the presence of contaminating H2S in commercial thiols and reducing agents, the need for specialized equipment, and the lack of an internal standard. Tissue generation of H2S ex vivo is often quantified by reacting head space gas above tissues incubated with media with lead acetate, and following the color change observed with conversion to lead sulfide [[20], [21], [22]]. Such methods do not enable quantification of in vivo H2S levels at the time of sample collection, but instead measure subsequent synthetic enzyme capacity of the sample collected. Other methods for H2S quantification involve derivatization with monobromobimane, fluorescent probes, or alternative reagents, and detection with either fluorescence or mass spectrometry; however, these methods all rely on the use of external calibration curves [18,19,23], and lack the many potential benefits conferred by an internal standard and isotope dilution methodology [24,25]. Further, while one of the most commonly used derivatization reagents for H2S quantification (i.e. monobromobimane) was selected due to its fluorescence, it has relatively poor ionization characteristics and is light sensitive, requiring that it be stored and reactions be performed in the dark – characteristics that limit its practical use for the high throughput demands of an in vitro clinical diagnostic LC-MS/MS assay.

Here, we describe the synthesis of the heavy isotope labelled sulfide ion [34S]S2−, its characterization, and the development of a stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS method for the quantification of Total H2S in biological matrices. To increase the utility of the assay, we also incorporated stable isotope dilution quantification of a panel of additional thiols abundant in circulation, enabling their simultaneous quantification with high sensitivity and throughput. We then applied the method to study circulating Total H2S levels (and the panel of thiols) in healthy individuals for normal range studies, and in both a clinical cohort and a small cohort of volunteers treated with a cocktail of poorly absorbed oral antibiotics to enable quantitative examination of both the effect of age and the contribution of the gut microbiota to systemic levels of Total H2S and abundant thiols.

2. Results

2.1. Analytical validation

2.1.1. Internal standard synthesis and LC-MS/MS assay method development

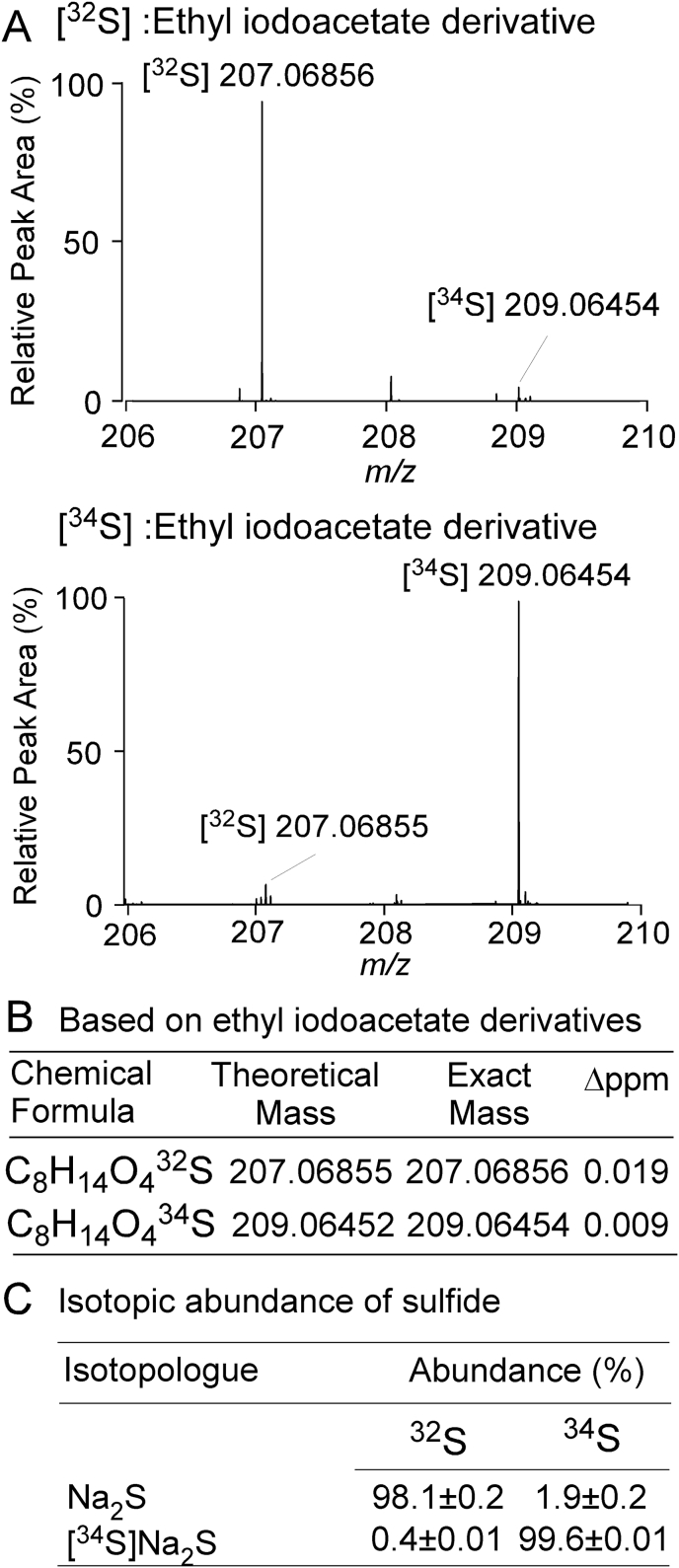

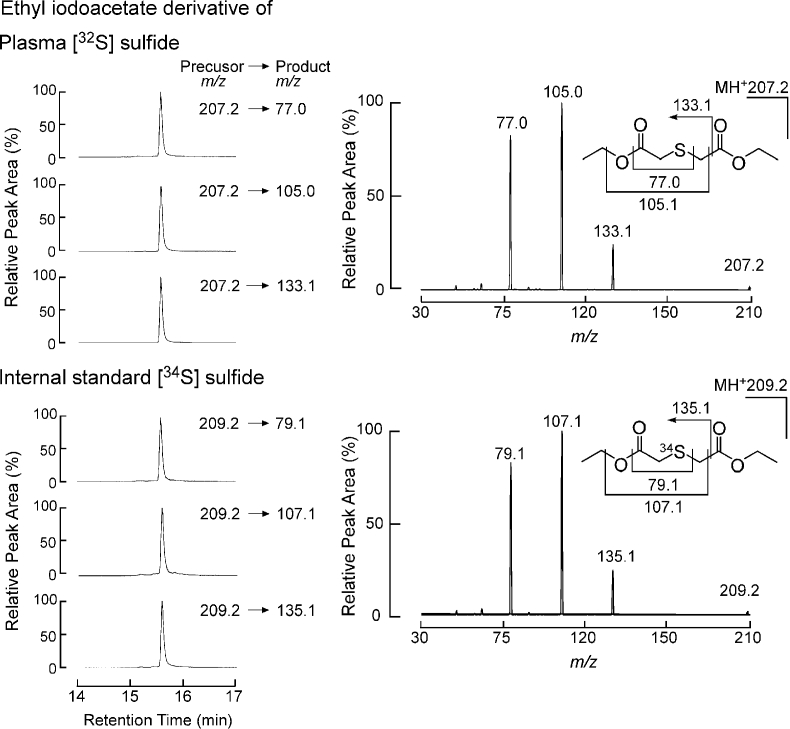

To serve as internal standard, [34S]Na2S was synthesized by reacting heavy isotope-labelled elemental sulfur [34S] with metallic sodium in tetrahydrofuran under an anhydrous nitrogen atmosphere (Methods and Supplemental Data). Optimized reaction conditions for an ethyl iodoacetate derivatization strategy were selected for analysis of sulfide (m/z 207.2), as described in Methods (Fig. 1, Supplemental Table 1). Analysis of the isotopic purity of the synthetic internal standard, [34S]Na2S (post-derivatization m/z 209.06454) showed 99.60 ± 0.01% [34S] enrichment (Methods, Fig. 1C), and its purity was confirmed by iodometric titration to be 108 ± 1.4% (Methods). The ethyl iodoacetate derivatives of sulfide and [34S]-sulfide were monitored using electrospray ionization in positive-ion mode, and three product ions for each isotopologue were selected for quantification using individual tuning (m/z 207.2 → 77.0, 207.2 → 105.0, 207.2 → 133.1 and m/z 209.2 → 79.1, 209.2 → 107.1, 209.2 → 135.1 for [32S] and [34S] derivatives, respectively). Fig. 2 shows the CID spectra (right) and co-chromatography (left) of selected multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions for the quantification of natural-abundance and heavy isotope-labelled sulfide, using reverse phase liquid chromatographic conditions developed to retain and separate the ethyl iodoacetate derivatives of sulfide and other abundant plasma thiols (cysteine, homocysteine, glutathione, glutamylcysteine, cysteinylglycine). Supplemental Figs. 1 and 2 show the CID spectra and MRM transitions selected for natural abundance and heavy isotope enriched internal standards for these thiols. For each analyte monitored, at least two distinct precursor-product ion transitions were selected, and the specificity of the mass selection and fragmentation of the plasma thiols monitored simultaneously with sulfide gave the necessary compound specificity.

Fig. 1.

Characterization and isotopic purity of commercially available Na2S and synthesized isotope labelled internal standard [34S]Na2S. (A) Electrospray ionization (ESI, positive ion mode) high resolution mass spectrum of ethyl iodoacetate derivatized H2S (top panel) and the corresponding derivative of synthesized internal standard ([34S]H2S) (bottom panel). (B) Calculation of Δ (ppm) for H2S derivatives (containing either 32S or 34S) observed in the high resolution mass spectra. (C) Isotopic abundance of 32S and 34S in synthesized heavy isotope labelled internal standard ([34S]Na2S) and commercially available sodium sulfide (Na2S).

Fig. 2.

Chromatography and collision induced dissociation spectra of the derivatives of circulating H2S and synthesized heavy isotope labelled [34S]Na2S. The chromatography (left panel) shows the retention time of 15.7 min for the derivatives of both H2S and the heavy isotope labelled internal standard. The CID mass spectrum (right top panel) of the derivative of H2S precursor ion (m/z = 207.2) yields fragments (product ions) with m/z 77.0, 105.0, and 133.1, whereas the derivative of the heavy isotope labelled internal standard (right bottom panel, m/z = 209.2) yields fragments with m/z 79.1, 107.1, and 135.1.

2.1.2. Selection of polysulfide reducing reagent and prevention of contaminant sulfide introduction during sample preparation for H2S quantification

Endogenous oxidants and post-collection oxidation processes can convert sulfide into polysulfide and mixed disulfides. To avoid H2S oxidation, as well as H2S production by iron and vitamin B6 [26], we added diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) to solutions during sample preparation. We also noticed that H2S content artificially increases when using commercially acquired reductants like β-mercaptoethanol (BME) or dithiothreitol (DTT) at levels needed to quantitatively reduce polysulfides. This was avoided (Methods), and polysulfides were shown to be quantitatively recovered as free reduced H2S using tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) as reductant (Methods, Supplemental Fig. 3). Similarly, during spike and recovery studies with thiols monitored within the panel, significant artificial elevation of H2S was observed when using commercial sources of thiols at physiological concentrations. After developing protocols to remove sulfide impurities, we confirmed the assay methods developed showed quantitative recovery of each analyte within the panel without interference or artificial H2S elevation, even when spiked with thiols at levels 10 times higher than physiological concentrations (Methods, Supplemental Fig. 4).

2.1.3. Validation of the stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS method for the quantitation of total H2S and thiols

Our H2S quantification method was validated according to Clinical Laboratory Improvements and Amendments (CLIA) standards [27,28], included stability evaluation, and evaluation of matrix effect, linearity, lower limit of quantification (LLOQ), lower limit of detection (LLOD), accuracy, inter-day and intra-day imprecision, and substance interference (Table 1, Supplemental Tables 2–9, Supplemental Figs. 5–12). Pilot studies to determine optimal storage conditions to prevent loss of the synthesized isotope-labelled internal standard (IS) (and verification at 2 months and then again after 1 year) resulted in storage of IS in airtight vials with minimal headspace and at −80 °C. Under these conditions, the IS ([34S]Na2S) showed 93.9 ± 3.9% recovery at 1 year (Supplemental Table 2). We also examined the recovery of IS for H2S and other monitored thiols in human plasma by comparing analyte peak areas in pooled human serum versus vehicle. The percentage recovery of [34S]-sodium sulfide, [3,3-D2]-cysteine, [3,3,4,4,-D4]-homocysteine and [13C2,15N]-glutathione were all >96.8% (Supplemental Table 3).

Table 1.

Determination of accuracy, precision, and recovery of the stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS method for quantification of Total H2S and thiols in plasma.

| Compound | SAM concentration (μM) | Mean concentration (μM) | Accuracy (%) | Imprecision (CV %) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-day | Inter-day | |||||

| Hydrogen Sulfide | QC1 | 9.4 | 9.0 ± 1.1 | 104.4 | 7.6 | 12.7 |

| QC2 | 19.5 | 21.8 ± 2.2 | 89.4 | 5.6 | 9.9 | |

| QC3 | 28.5 | 28.8 ± 1.6 | 98.9 | 4.0 | 5.7 | |

| Cysteine | QC1 | 69.6 | 72.6 ± 6.7 | 95.9 | 8.3 | 9.2 |

| QC2 | 267 | 254.2 ± 25.1 | 104.9 | 4.3 | 9.9 | |

| QC3 | 706 | 691.9 ± 25.6 | 102.0 | 1.3 | 3.7 | |

| Homocysteine | QC1 | 7.2 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 116.9 | 5.8 | 8.0 |

| QC2 | 11.1 | 11.2 ± 0.9 | 98.6 | 4.5 | 7.6 | |

| QC3 | 45.3 | 45.5 ± 2.1 | 99.5 | 8.1 | 4.7 | |

| Cysteinylglycine | QC1 | 6.2 | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 108.2 | 15.8 | 9.3 |

| QC2 | 10.1 | 9.9 ± 1.0 | 101.2 | 4.2 | 11.8 | |

| QC3 | 22.1 | 22.3 ± 2.6 | 99.2 | 5.7 | 12.2 | |

| Glutathione | QC1 | 3.7 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | 109.6 | 7.5 | 9.7 |

| QC2 | 9.2 | 9.5 ± 1.1 | 96.7 | 6.9 | 10.5 | |

| QC3 | 24.0 | 23.5 ± 2.9 | 101.9 | 5.2 | 11.5 | |

| Glutamylcysteine | QC1 | 0.8 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 102.1 | 2.3 | 11.5 |

| QC2 | 2.6 | 2.7 ± 0.4 | 94.4 | 5.7 | 14.4 | |

| QC3 | 6.6 | 6.7 ± 0.8 | 99.0 | 7.0 | 11.8 | |

Inter-day imprecision and accuracy were determined on three different quality control (QC) samples. The inter-day imprecision was determined by injecting 3 replicates of each QC every day for 6 different days and calculating the inter-day coefficients of variation from mean concentration: Inter-day Imprecision (CV, %) = 100 × (standard deviation/mean concentration). Intra-day accuracy was determined by the standard addition method (SAM) for the three QC levels and compared with values obtained from 3 replicates of each of the three QCs analyzed over 6 days using the methods calibration curve. Accuracy (%) = 100 × mean concentration/SAM concentration. Intra-day imprecision was determined on three different quality control (QC) samples. The intra-day imprecision was determined by injecting 6 replicates of each QC in the same day; Intraday Imprecision (CV, %) = 100 × standard deviation/mean concentration.

2.1.4. Stability

The stability of H2S and thiols in samples was determined through an accelerated stability study of pooled serum samples (Quality Control (QC) samples at 3 concentration levels) analyzed in triplicates at 60 °C for 5 days and compared with fresh matrix that was immediately processed. Sample stability was 94.4% for H2S and 90–100.5% for the thiols in the panel (Supplemental Table 4). Freeze-thaw stability after 5 freeze-thaw cycles (Methods) was 98.6% for H2S and 90.9–110% for the thiols monitored (Supplemental Table 5). Long-term stability (1 year) was excellent, showing <10% bias for all analytes in the panel monitored (Supplemental Table 6, Supplemental Fig. 5). Extract stability was also tested by reanalyzing QC extracts after ≥3 days at 10 °C (auto-sampler temperature) and quantifying against a freshly analyzed sample. The mean percent biases from the initial QC values for H2S and thiol analytes in the panel were between −3.0% and 10.0% (Supplemental Table 7).

2.1.5. Matrix effect, linearity, LLOD and LLOQ

After clearing commercial thiols of residual H2S (Supplemental Methods), we used the spike-and-recovery approach to generate calibration curves for H2S and each thiol in the LC-MS/MS panel at eight different plasma concentrations (Supplemental Fig. 6). Comparing calibration curves in multiple different matrices (Supplemental Table 8), the calibration curves for H2S and thiols in water and serum displayed minimal matrix effect across all analytes, with linear responses (r2 > 0.994) over 6 non-zero point calibration curves spanning physiological analyte concentration ranges (Supplemental Table 8 and Supplemental Fig. 6). The LLOD was determined to be the lowest concentration of analyte in the sample with a signal-to-noise ratio ≥3 (2 nM for H2S), and the LLOQ was determined to be the lowest concentration of analyte in the sample with a signal-to-noise ratio ≥10 (6 nM H2S). LLOD and LLOQ for other thiols monitored in the panel are provided in Supplemental Table 9.

2.1.6. Accuracy and intra-day/inter-day imprecision

Accuracy of the LC-MS/MS method was determined by comparing calculated versus measured analyte concentrations in 3 different serum pools spanning physiological concentrations (QC1 not spiked, QC2 and QC3 spiked with increasing amount of analyte) [27]. For H2S, accuracy ranged from 98.9 to 104.4%, and comparable accuracy was noted for each of the other thiols monitored in the panel (Table 1). Intra-day and inter-day imprecision of analyte values in serum were also evaluated at 3 QC levels (low, middle, high) [27], and are shown in Table 1.

2.1.7. Interference and selectivity

Interference studies examining the effect of bilirubin, lipids (triglycerides), and hemolysis on the quantitation of H2S and other thiols within the panel were performed on samples following procedures recommended by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute [29]. Briefly, icteric, lipemic, and hemolytic interferences were assessed using 6 concentrations of bilirubin (31.25–1000 μM), a triglyceride mix (0.375–12 mM), and hemolyzed red blood cells (0.25%–8%) spiked into three samples. Interferences with H2S quantification showed biases of <2% (Supplemental Fig. 7). Bilirubin did not show significant interference in the quantification of any of the thiols (Supplemental Figs. 8–12). However, hemolytic interference with the quantification of cysteine, homocysteine, and glutathione was more pronounced (18.5–23.5%, 22.5–26.5%, and 33-9% respectively; Supplemental Figs. 8–12). Lipemic interference was detected only in glutathione, showing a bias of 15.8–44% when the concentration was increased in a dose-dependent manner (Supplemental Figs. 8–12), which presumably occurred by the release of glutathione from hemolyzed (rich in glutathione) red blood cells.

2.1.8. Comparison of collection tube type and carryover

We also examined the impact of collection tube interference and differences in blood sample types. Blood was collected from 10 donors into each of the following tube types: EDTA plasma, lithium heparin plasma, sodium citrate, and serum separator tubes. The samples were processed by standard procedures and the resulting paired plasma and serum samples from each donor were compared for differences in overall analyte quantification. No differences among tube types for all analytes monitored in the panel were noted, with sample differences ranging from −0.1% to 1.1% (Supplemental Fig. 13). Analyte carryover, determined by injecting water immediately after the highest standard, showed no detectable carryover for H2S or any of the thiol analytes monitored.

3. Clinical validation

3.1. Establishing reference ranges for circulating Total H2S and thiols monitored in healthy volunteers

Reference ranges of Total H2S and thiols in plasma were determined using samples collected from apparently healthy subjects (n = 200) recruited from community health screenings (Methods). Subjects were considered healthy if they reported no medical history of cardiovascular disease, history or laboratory findings consistent with diabetes, cardiometabolic disorders, or cancer, no reported use of any medications, and showed normal laboratory screening results for basic metabolic and lipid panels (Supplemental Table 10A). The normal range of plasma concentrations was determined to be 4.2–62.7 μM for Total H2S, 46.1–463.8 μM for Total cysteine, 1.5–16.5 μM for Total homocysteine, 3.1–90.3 μM for Total cysteinylglycine, 0.8–16.9 μM for Total glutamylcysteine, and 0.3–12.0 μM for Total glutathione (Supplemental Table 10B).

3.2. Clinical cohort study population

Clinical characteristics of this study cohort are shown in Supplemental Table 11. Participants were stable consenting subjects undergoing general health or risk factor evaluation. The mean age in the cohort was 65.2 ± 11.0 years, 50% were men, 94.8% were Caucasian, and the mean BMI was 29.0 ± 5.6 kg/m2. Median (interquartile range) of total cholesterol was 164 (138.4–191.1) mg/dL, triglycerides was 112.0 (85.0–168.0) mg/dL, HDL cholesterol was 37.9 (30.4–48.1) mg/dL and LDL cholesterol was 95.0 (74.0–119.5) mg/dL.

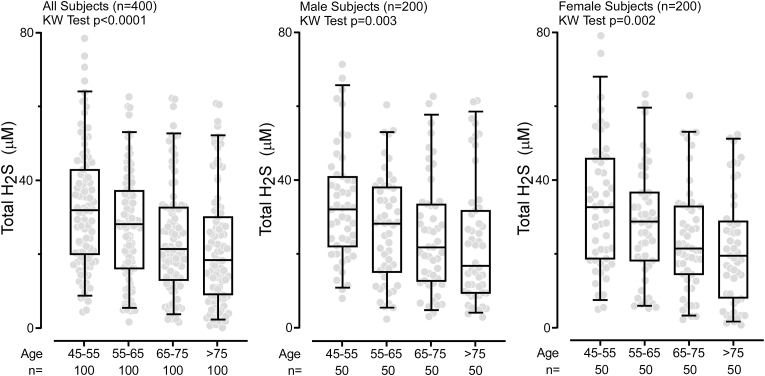

3.3. Plasma levels of total H2S decrease with age

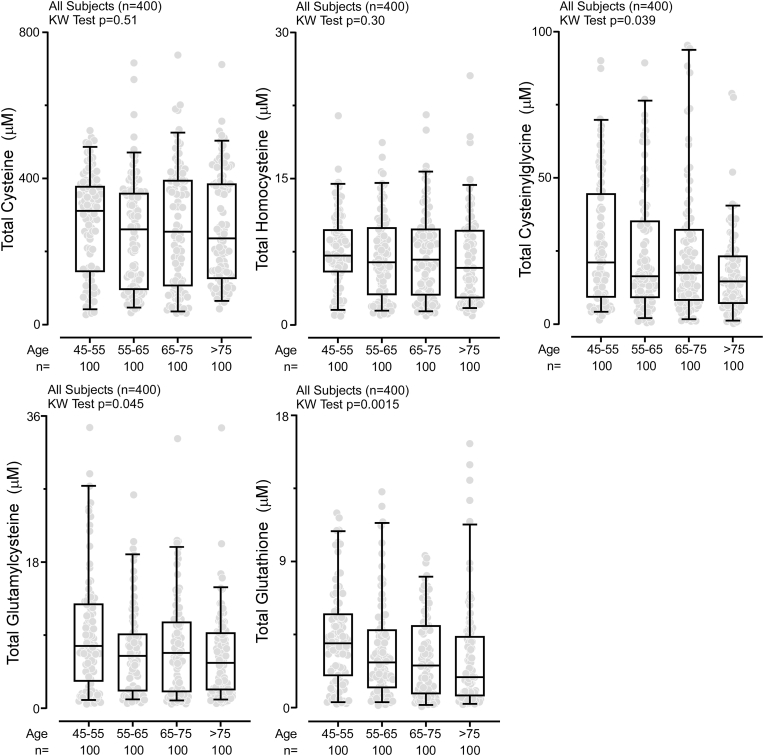

Numerous studies suggest that production of H2S and its downstream protein persulfidation diminishes with age [8,9,30]. We used our newly developed method to determine plasma levels of Total H2S and thiols in an independent clinical cohort (n = 400) to examine the association of H2S with aging. The analyses shown in Fig. 3 reveal that Total H2S levels decrease with age (p < 0.0001). This trend was observed in both males (p = 0.003) and females (p = 0.002) (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 14). We also observed age-associated reductions in plasma concentrations of Total cysteinylglycine, Total glutamylcysteine, and Total glutathione (Fig. 4) in the combined male/female cohort, but when data were separated by gender, only males had a statistically significant reduction across age categories examined in Total glutamylcysteine levels (p = 0.045). Both males and females showed significant reduction with age in Total glutathione levels (males p = 0.023, females p = 0.0005), Supplemental Fig. 15).

Fig. 3.

Circulating levels of Total H2S decrease with age. Older subjects show significantly lower levels of Total H2S in plasma than younger subjects. The age in years was stratified by four groups (≥45to<55, ≥55to<65, ≥65to<75, ≥75). The division of subjects by gender shows that reduction of Total H2S with aging is independent of gender. Boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively; the middle line is the median, and the lower and upper whiskers are the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. P-values were calculated using the Kruskal Wallis test where p < 0.05 is significant.

Fig. 4.

Changes in levels of circulating Total thiols with age. Older subjects show significantly lower levels of circulating Total thiols compared to younger subjects in each of Total cysteinylglycine, Total glutamylcysteine and Total glutathione. The downward trend is monotonic for Total cysteinylglycine, Total glutamylcysteine and Total glutathione and visible steeper for Total cysteinylglycine. Age is reported in years. Boxes indicate the 25th and 75th percentiles, respectively, the middle line is the median, and the lower and upper whiskers are the 5th and 95th percentiles, respectively. P values were calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, where p < 0.05 is significant.

3.4. Gut microbiota contribute significantly to circulating levels of total H2S in humans

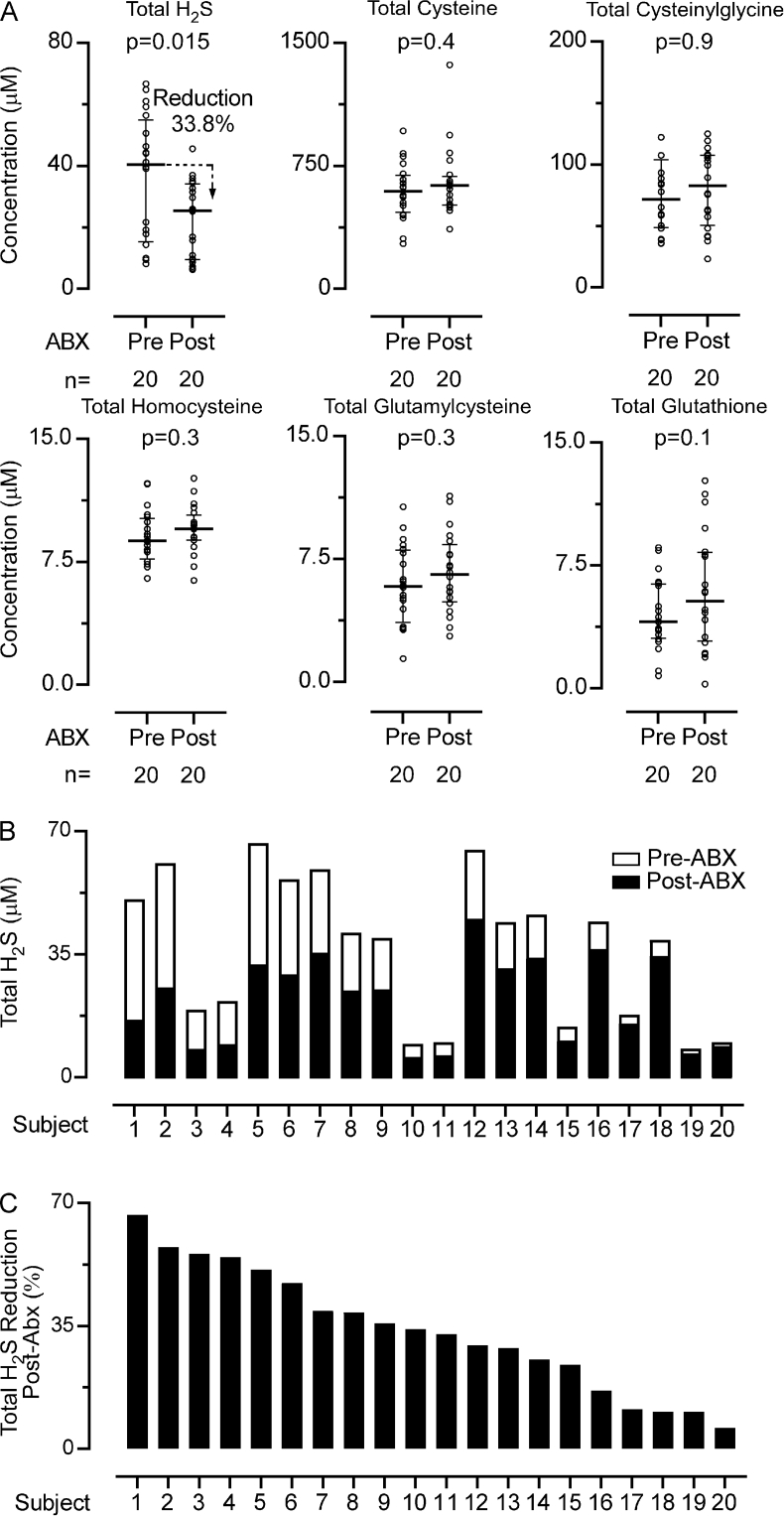

While it is widely recognized that some gut microbes can produce H2S [5], and one study reports that germ-free mice have decreased plasma H2S levels [31], the contribution of gut microbiota to systemic H2S levels in humans is unknown. We therefore quantified circulating levels of Total H2S and thiols in a cohort of 20 healthy volunteers before and after ≥5 days of an oral cocktail of poorly-absorbed broad-spectrum antibiotics previously shown to suppress gut microbiota [32,33]. On average, Total H2S concentrations were diminished by 33.8 ± 17.7% (p = 0.015, Mann-Whitney test) following suppression of gut microbiota. Post antibiotics treatment we observed a 29.2% reduction of Total H2S levels in females and 37.6% in males, however there was no significant difference in Total H2S reduction between males and females (p = 0.94, Mann-Whitney test) (Supplemental Fig. 16). In addition, none of the other thiols monitored showed reductions following gut microbiota suppression (Fig. 5A). Notably, the contributions of gut microbiota to systemic Total H2S levels varied widely across subjects (Fig. 5B), ranging from 6.0%–66.7% (Fig. 5C). For example, in 25% of the subjects (subjects 1–5, Fig. 5C), >50% reduction in circulating Total H2S was observed post-antibiotics exposure, suggesting the majority of systemic H2S originated from gut microbiota source in these subjects. In contrast, 15% of the subjects (subjects 17–20) showed <10% reduction following antibiotics.

Fig. 5.

Effect of gut microbiota suppression on circulating Total H2S levels. (A) Circulating levels of Total H2S and thiols after administration of poorly absorbed broad-spectrum antibiotics. The circulating levels of Total H2S are reduced approximately 35% after antibiotics treatment. Conversely, the circulating levels of Total cysteine, Total homocysteine, Total cysteinylglycine, Total glutamylcysteine, and Total glutathione do not change significantly following antibiotics administration. (B) Circulating levels of Total H2S for individual subjects before antibiotics treatment displayed as white bars, and after antibiotics treatment as black bars. (C) Percent reduction of the Total H2S circulating levels due to antibiotics treatment for individual subjects. The study shows that the reduction in Total H2S levels vary strongly among subjects. P values were calculated using the Mann–Whitney test where p < 0.05 is significant.

4. Discussion

Despite the growing interest in H2S as an endogenous gaseous mediator that influences human health, aging, and susceptibility to numerous diseases [8,17,34,35], research has been limited by the lack of a quantitative stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS method for the analyte. Moreover, the relative contributions of host versus enteric gut microbial sources for H2S production in humans are unknown. The stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS method described here – enabled by the synthesis of [34S]Na2S (internal standard) and the development of methodology that minimizes previously unappreciated interferences – allowed for the robust quantification of Total H2S and thiols in biological matrices. Incorporation of H2S quantification into a panel of (reduced) thiols highly abundant in the circulation further enhances the utility of the methods described. In addition, spike and recovery studies performed during assay development enabled detection of artefactual contributions of contaminant H2S in commercial sources of “pure” standard thiols and numerous reducing reagents, which would not have been easily observed without the ease and power afforded by stable isotope dilution methodology. To our knowledge, this is the first stable isotope labelled H2S based quantification method reported that incorporates all of the advantages of isotope dilution mass spectrometry methodology, i.e., the method allows the internal standard ([34S]Na2S) to react with the derivatizing reagent under the same conditions as the endogenous sulfide ions ([32S]2-) in the sample, allowing for maximum accuracy. Similarly, all of the other factors involved in the LC-MS/MS method (stability, extraction, ionization, fragmentation, matrix effect, chromatographic differences, etc.) have been optimized, and shown to result in an assay with excellent accuracy and reproducibility.

Extensive cellular, animal model, and human clinical association studies have focused on the involvement of H2S in the prevention of aging, and on its reduction as a risk factor for various age-related diseases [36,37]. Many of these studies measure enzymatic generation capacity and/or protein persulfidation in plasma, serum, or other tissues, rather than measuring endogenous levels [8,30,38,39]. In addition, provision of exogenous H2S or an H2S generating reagent has been suggested as a potential therapeutic agent to reduce ischemia reperfusion injury and promote tissue preservation [10,40]. The results of the present studies suggest that if gut microbiota-generated H2S could be manipulated for therapeutic gain, it might significantly impact systemic levels in subjects. It also raises the possibility of targeting manipulation of gut commensal H2S production as a means to potentially impact physiological processes, with use of the current methods enabling quantitative monitoring of the contribution of gut microbiota to total systemic levels for the first time.

The clinical studies presented here suggest that circulating levels of Total H2S are reduced with aging in both men and women. The origins of this reduction are unknown. Indeed, one might speculate that reduced gut commensal synthesis might contribute to this observation, or alternatively, reduction in host enzymatic machinery, or even accelerated excretion and metabolism of sulfide with aging. The present studies were not designed to explore the origins of this age-associated reduction, which might also arise in part from an accumulation of comorbidities whose prevalence increases with aging.

We note that the method developed here, while highly accurate, does not measure “free” reduced H2S present at time of sample collection. Rather, by reducing reversibly oxidized forms of sulfide prior to derivatization, the present methods measures “total” levels of H2S (and each of the other thiols monitored). Whether there is clinical significance to the measurement of “total” versus “free” H2S in subjects remains to be determined. We initially sought to quantify both “free” and “total” H2S in captured (archival) plasma or serum samples, but found that artefactual oxidation (post collection) was inexorable, even when purging headspace gas with argon before freezing and use of anti-oxidant cocktails, unless samples were derivatized immediately following sample processing and before freezing. Since this was not done with the numerous clinical archival sample sets available for study, we instead developed this “total” H2S method, which was found to be both reproducible, and as shown, stable to samples stored over time (even following multiple freeze/thaw cycles).

While our study focuses on the development of a stable isotope dilution LC-MS/MS assay for Total H2S, results from application of the panel generated for the quantification of other abundant thiols in the circulation revealed that total levels of glutathione, glutamylcysteine and cysteinylglycine, like H2S, are significantly inversely associated with advancing age (p < 0.0001, Kruskal Wallis test). But unlike H2S, none of these thiols showed evidence of having a component originating from gut microbiota. The involvement of thiols like glutathione and cysteine in regulating redox levels of both cellular and physiological processes is widely recognized [41,42]. The development of the present LC-MS/MS method will also serve as a valuable tool in the performance of research studies in these areas.

5. Materials and methods

5.1. Materials

Screwcap cryovials (1.5 mL) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Aeris 2.6 μm Peptide XB-C18 100 LC column 150 × 4.6 mm, Security guard Ultra Holder, Security guard Ultra Cartridges were purchased from Phenomenex (Torrance, CA). Chemglass Life Sciences 25 mL Tube, Storage, 14/20 Outer Joint, Airfree, Schlenk tube and 2 mL Filter Funnel, Buchner, Fine Frit were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). All reagents and mobile phases were LC-MS-grade solvents purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA) unless otherwise specified. MS grade water was produced in-house by a Millipore Milli-Q purification system with an LC-Pak Polisher filter for ultrapure water used for HPLC and LC-MS (Darmstadt, Germany). A more detailed list of reagents is in Supplemental Methods.

5.2. Research subjects

All subjects gave written informed consent, and all study protocols were approved by the institutional review board of the Cleveland Clinic and adhered to the declaration of Helsinki principles. Subject antibiotics exposure followed an approved protocol registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01731236). Samples for establishing a normal range of analytes were collected from non-fasting subjects undergoing community health screening. From these, a random subset of subjects (n = 200) were selected who met the inclusion criterion requirements of no medical history of cardiometabolic diseases or cancer, normal vital signs, and normal metabolic test values on screening studies (lipid profile, complete metabolic panel)

Blood was drawn from subjects for all studies, including those comparing the effect of vacutainer tube type on analyte levels, using a 21Gauge BD Vacutainer Safety-Lok Blood Collection Set. Plasma vacutainer tubes were placed on ice or within a refrigerator until processing, and serum tubes were maintained at room temperature for 60 min to allow for clotting to proceed before centrifugation. One hour (60 min) following blood collection, both plasma and serum vacutainer tubes were spun for 15 min at 4 °C at 1530 relative centrifugal force. Samples were aliquotted into 1.5 mL O-ring screw cap cryovials (catalogue number Z353361, Millipore Sigma, St. Louis, MO), placed immediately on dry ice, and then stored at −80 °C until analyses.

5.3. Synthesis and storage of heavy isotope labelled internal standard [34S]Na2S

We synthesized heavy isotope-labelled sodium sulfide ([34S]Na2S) using the reaction of metallic sodium and elemental sulfur 34S in the presence of naphthalene as a catalyst [43]. The reaction was performed under anaerobic conditions under dry nitrogen atmosphere in an anhydrous and degassed medium within a glovebox (MBraun Labstar Pro). All glassware were dried at 160 °C prior to use. Tetrahydrofuran was deoxygenated by sparging with dry nitrogen, and then dried via passage through activated alumina in an MBraun MB-SPS solvent purification system. Briefly, elemental sulfur (34S) and metallic sodium were mixed in a 1:2 M ratio inside the glove box in a Schlenk tube at room temperature. The Schlenk tube was sealed, and then heated in an oil bath (outside the glovebox) until color change to white (80 °C, 24 h) [44]. The Schlenk tube was then moved back into the glovebox, and the precipitate was collected on filter paper, and dried overnight under nitrogen atmosphere. The purity of the heavy isotope label sulfide ([34S]Na2S) was confirmed by iodometric titration and the isotopic enrichment for [34S] (versus other isotopologues) was quantified by high resolution mass spectrometry.

The internal standard stock solution was prepared by weighing anhydrous [34S]Na2S (in glovebox under nitrogen atmosphere) and dissolving it in ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 10). Once dissolved in aqueous solution at basic pH, the highly charged sulfide ion internal standard has low vapor pressure and is more stable (losses from outgassing are minimal). The stock solution was stored in conventional o-ring sealed cryovials (500 μL with minimal headspace gas) at −80 °C, and the concentration of this stock was confirmed by either iodometric titration (as described), or by the method of standard addition using authentic anhydrous [32S]Na2S.

5.4. Sample preparation

During methods development and throughout the derivatization reaction optimization process, samples were handled in gas tight vials with mininert caps. While the reaction was carried out, the IS mix and derivatizing reagent were injected into the tube through the septa using gas-tight Hamilton syringes.

Serum samples were blanketed with argon and stored at −80 °C. After thawing at 4 °C, samples were aliquoted (20 μL) on dry ice into screw cap O-ring tubes. The IS mixture master stock (500 μL in a 500 μL cryovial) was stored at −80 °C with minimal headspace gas. The IS mixture used in sample preparation was prepared from IS mixture master stock, and before opening vials were thawed on ice. The reducing reagent (TCEP) was added to the sample at the same time as the internal standard mix (prior to derivatization). Endogenous H2S (free and oxidized, including protein bound) and thiols, as well as their respective internal standards, were reduced by treating samples with TCEP prior to derivatization.

To derivatize samples (20 μL), ethyl iodoacetate solution (50 μL, 16 mM) and IS mixture (10 μL) were added (final concentrations in final volume (80 μL) are 6.25 mM ammonium bicarbonate (pH 10.0), 12.5 mM TCEP, 10 mM EIA, Supplemental Methods), vials sealed and vortexed for 2 min, and then left at room temperature (21 °C) for least 8 h (and no longer than 24 h) to allow the derivatization reaction to complete. Before analysis, proteins were precipitated with ice cold acetonitrile (100 μL), samples centrifuged (14,000×g, 20min, −1 °C), and supernatants transferred to HPLC vials.

5.5. LC-MS/MS run conditions

Analysis of the derivatized samples was performed on an AB SCIEX LC-MS/MS 4000 Q-Trap triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometer with an electrospray ionization (ESI) source in positive ion mode. Separation of analytes was performed on a reverse phase column (Aeris™ 2.6 μm Peptide XB-C18 100 Å, LC Column 150 × 4.6 mm, Phenomenex, Torrance, CA). Mobile phase A (5 mM ammonium formate, 0.2% formic acid in water), and mobile phase B (0.2% formic acid in 25:75 v/v methanol:acetonitrile) were used for discontinuous gradient separations (Supplemental Methods).

The concentration of each analyte was determined by the area ratio obtained from a primary MRM transition (i.e. for H2S 207.2 → 133.1 ([32S] isotopologue) to 209.2 → 135.1 ([34S] isotopologue)) and then quantification was confirmed by obtaining comparable results using the area ratio of secondary MRM transitions (207.2 → 105.0 (for [32S] isotopologue) and 209.2 → 107.1 (for [34S] isotopologue)), and a similar approach was applied for other thiols with their respective heavy isotope labelled internal standards. We could not obtain commercially available internal standards for the dipeptide analytes cysteinylglycine and glutamylcysteine. Therefore, we used [3,3,4,4,-D4]-homocysteine and [13C2,15N]-glutathione as internal standard for cysteinylglycine and glutamylcysteine, respectively (MRM transitions 225.6 → 106.1 for [3,3,4,4,-D4]-homocysteine, 265.4 → 162.1 for cysteinylglycine, 397.4 → 177.1 for [13C2,15N]-glutathione, 337.1 → 191.1 for glutamylcysteine).

5.6. Establishing reference range of analytes

Analyte normal ranges were determined based on standards defined from CLIA and the College of American Pathologists [27]. The reference range was determined to be the 95% central interval bounded between the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles and used to determine the lower and upper limit concentrations in the listed concentrations.

5.7. Determining the contribution of gut microbiota to circulating H2S

Blood was collected from 20 healthy volunteers at baseline, and again after one week of chronic exposure to a cocktail of oral, poorly-absorbed, broad-spectrum antibiotics. The mean concentration of Total H2S was calculated before and after antibiotics were administered. The difference between the mean values was calculated as percentage of pre-antibiotic levels.

5.8. Statistical analyses

The Wilcoxon rank sum test or Mann-Whitney test for continuous variables were used to examine the difference between the groups where appropriate. Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare analyte levels across age groups. All analyses were performed with RStudio-R version 4.1.2. (2021-11-01) (Vienna, Austria), or GraphPad Prism (version 9.1.2; GraphPad Software, Inc), and P-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Author contributions

Hind Malaeb performed all experiments, analyzed the data from all studies, prepared initial manuscript figures and tables, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Ibrahim Choucair and Zeneng Wang contributed to the mass spectrometry analyses. Xinmin S. Li and Lin Li assisted with statistical analyses. Christopher Boyd assisted with the synthesis of the internal standard and critical scientific input and discussions. Christopher Hine provided advice and literature suggestions. W.H. Wilson Tang provided assistance with clinical sample collections and critical scientific input and discussions. Valentin Gogonea contributed to statistical analyses and writing of the manuscript. Stanley L. Hazen conceived, designed, and supervised all studies and contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript. S.L.H. and V.G. funded the project. All authors contributed to the critical review and the editing of the manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Stanley L. Hazen and Zeneng Wang report being named as co-inventors on pending and issued patents held by the Cleveland Clinic relating to cardiovascular diagnostics and therapeutics, and being eligible to receive royalty payments for inventions or discoveries related to cardiovascular diagnostics or therapeutics from Cleveland HeartLab, a wholly owned subsidiary of Quest Diagnostics, Procter & Gamble and Zehna Therapeutics. S.L.H. reports being a paid consultant for Procter & Gamble and Zehna Therapeutics, and having received research funds from Procter & Gamble, Zehna Therapeutics and Roche Diagnostics. The other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Acknowledgments

This study and its personnel were supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health R01HL103866 and P01HL147823. S.L.H. reports partial support from the Leonard Krieger Fund and the Leducq Foundation. CH is partially supported by NIH grant R01HL148352. The Fusion Lumos instrument used for some of the mass spectrometry studies was purchased via an NIH shared instrument grant, 1S10OD023436-01.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102401.

Contributor Information

Valentin Gogonea, Email: v.gogonea@csuohio.edu.

Stanley L. Hazen, Email: Hazens@ccf.org.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Rui W. Two's company, three's a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB. 2002;16:1792–1798. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0211hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stipanuk M.H., Beck P.W. Characterization of the enzymic capacity for cysteine desulphhydration in liver and kidney of the rat. Biochem. J. 1982;206:267–277. doi: 10.1042/bj2060267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Braunstein A.E., Goryachenkova E.V., Tolosa E.A., Willhardt I.H., Yefremova L.L. Specificity and some other properties of liver serine sulphhydrase: evidence for its identity with cystathionine β-synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1971;242:247–260. doi: 10.1016/0005-2744(71)90105-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuo S.M., Lea T.C., Stipanuk M.H. Developmental pattern, tissue distribution, and subcellular distribution of cysteine: α-ketoglutarate aminotransferase and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase activities in the rat. Neonatology. 1983;43:23–32. doi: 10.1159/000241634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flannigan K.L., McCoy K.D., Wallace J.L. Eukaryotic and prokaryotic contributions to colonic hydrogen sulfide synthesis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2011;301:188–193. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00105.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilkie S.E., Borland G., Carter R.N., Morton N.M., Selman C. Hydrogen sulfide in ageing, longevity and disease. Biochem. J. 2021;478:3485–3504. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20210517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li Z., Polhemus D.J., Lefer D.J. Evolution of hydrogen sulfide therapeutics to treat cardiovascular disease. Circ. Res. 2018;123:590–600. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y., Tang Z.H., Ren Z., Qu S.L., Liu M.H., Liu L.S., et al. Hydrogen sulfide, the next potent preventive and therapeutic agent in aging and age-associated diseases. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;33:1104–1113. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01215-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perridon B.W., Leuvenink H.G., Hillebrands J.L., van Goor H., Bos E.M. The role of hydrogen sulfide in aging and age-related pathologies. Aging. 2016;8:2264. doi: 10.18632/aging.101026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rushing A.M., Donnarumma E., Polhemus D.J., Au K.R., Victoria S.E., Schumacher J.D., et al. Effects of a novel hydrogen sulfide prodrug in a porcine model of acute limb ischemia. J. Vasc. Surg. 2019;69:1924–1935. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2018.08.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xia H., Li Z., Sharp T.E., III, Polhemus D.J., Carnal J., Moles K.H., et al. Endothelial cell cystathionine γ-lyase expression level modulates exercise capacity, vascular function, and myocardial ischemia reperfusion injury. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.017544. 17544-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blackstone E., Roth M.B. Suspended animation-like state protects mice from lethal hypoxia. Shock. 2007;27:370–372. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31802e27a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnarumma E., Trivedi R.K., Lefer D.J. Protective actions of H2S in acute myocardial infarction and heart failure. Compr. Physiol. 2017:7583–7602. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dugbartey G.J., Bouma H.R., Saha M.N., Lobb I., Henning R.H., Sener A. A hibernation-like state for transplantable organs: is hydrogen sulfide therapy the future of organ preservation? Antioxidants Redox Signal. 2018;28(16):1503–1515. doi: 10.1089/ars.2017.7127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Longchamp A., MacArthur M., Trocha K., Ganahl J., Mann C.G., Kip P., Kiing W., Sharma G., Tao M., Mitchell S., Yang J. Plasma hydrogen sulfide is positively associated with post-operative survival in patients undergoing surgical revascularization. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.750926. 750926-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang L., Wang Y., Li Y., Li L., Xu S., Feng X., et al. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-releasing compounds: therapeutic potential in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01066. 1066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Disbrow E., Stokes K.Y., Ledbetter C., Patterson J., Kelley R., Pardue S., Reekes T., Larmeu L., Batra V., Yuan S., Cvek U. Plasma hydrogen sulfide: a biomarker of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. Alzheim Dement. 2021;18:1391–1402. doi: 10.1002/alz.12305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shen X., Kolluru G.K., Yuan S., Kevil C.G. Measurement of H2S in vivo and in vitro by the monobromobimane method. Methods Enzymol. 2015;554:31–45. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan B., Jin S., Sun J., Gu Z., Sun X., Zhu Y., et al. New method for quantification of gasotransmitter hydrogen sulfide in biological matrices by LC-MS/MS. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–2. doi: 10.1038/srep46278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hine C., Mitchell J.R. Endpoint or kinetic measurement of hydrogen sulfide production capacity in tissue extracts. Bio. Protoc. 2017;7:e2382–e2383. doi: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McBride R.S., Edwards J.D. The lead acetate test for hydrogen sulphide in gas. J. Franklin Inst. 1914;178:639–642. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanderson H.P., Thomas R., Katz M. Limitations of the lead acetate impregnated paper tape method for hydrogen sulfide. J. Air Pollut. Control Assoc. 1966;16:328–330. doi: 10.1080/00022470.1966.10468482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karunya R., Jayaprakash K.S., Gaikwad R., Sajeesh P., Ramshad K., Muraleedharan K.M., Dixit M., et al. Rapid measurement of hydrogen sulphide in human blood plasma using a microfluidic method. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-39389-7. 1-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.FDA F. 2001. Guidance for Industry: Bioanalytical Method Validation.http://www.fda.gov/cder/Guidance/4252fnl.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stokvis E., Rosing H., Beijnen J.H. Stable isotopically labeled internal standards in quantitative bioanalysis using liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry: necessity or not? Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2005;19:401–407. doi: 10.1002/rcm.1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang J., Minkler P., Grove D., Wang R., Willard B., Dweik R., et al. Non-enzymatic hydrogen sulfide production from cysteine in blood is catalyzed by iron and vitamin B6. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0431-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Whitmire M., Ammerman J., De Lisio P., Killmer J., Kyle D., et al. LC-MS/MS bioanalysis method development, validation, and sample analysis: points to consider when conducting nonclinical and clinical studies in accordance with current regulatory guidances. J. Anal. Bioanal. Tech. 2011;4 2-2. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Association for Clinical Chemistry. CLIA. Clin. Lab. Improv. Amendments https://www.cdc.gov/clia/law-regulations.html (Accessed January 2022).

- 29.Dimeski G. Interference testing. Clin. Biochem. Rev. 2008;29:S43–S48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zivanovic J., Kouroussis E., Kohl J.B., Adhikari B., Bursac B., Schott-Roux S., et al. Selective persulfide detection reveals evolutionarily conserved antiaging effects of S-sulfhydration. Cell Metabol. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2019.12.001. 207-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen X., Carlström M., Borniquel S., Jädert C., Kevil C.G., Lundberg J.O. Microbial regulation of host hydrogen sulfide bioavailability and metabolism. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013;60:195–200. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.02.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang W.H.W., Wang Z., Levison B.S., Koeth R.A., Britt E.B., Fu X., et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:1575–1584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Haak B.W., Lankelma J.M., Hugenholtz F., Belzer C., de Vos W.M., Wiersinga W.J. Long-term impact of oral vancomycin, ciprofloxacin and metronidazole on the gut microbiota in healthy humans. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019;74:782–786. doi: 10.1093/jac/dky471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aminzadeh M.A., Vaziri N.D. Downregulation of the renal and hepatic hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-producing enzymes and capacity in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2012;27:498–504. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfr560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang L., Wang Y., Li Y., Li L., Xu S., Feng X., et al. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S)-releasing compounds: therapeutic potential in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.01066. 1066-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Y.H., Yao W.Z., Geng B., Ding Y.L., Lu M., Zhao M.W., et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;128:3205–3211. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benedetti S., Benvenuti F., Nappi G., Fortunati N., Marino L., Aureli T., et al. Antioxidative effects of sulfurous mineral water: protection against lipid and protein oxidation. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009;63:106–112. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hine C., Harputlugil E., Zhang Y., Ruckenstuhl C., Lee B.C., Brace L., et al. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide production is essential for dietary restriction benefits. Cell. 2015;160:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Henderson Y.O., Bithi N., Link C., Yang J., Schugar R., Llarena N., et al. Late-life intermittent fasting decreases aging-related frailty and increases renal hydrogen sulfide production in a sexually dimorphic manner. Geroscience. 2021;43:1527–1554. doi: 10.1007/s11357-021-00330-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bos E.M., van Goor H., Joles J.A., Whiteman M., Leuvenink H.G. Hydrogen sulfide: physiological properties and therapeutic potential in ischaemia. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2015;172:1479–1493. doi: 10.1111/bph.12869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones D.P., Carlson J.L., Mody V.C., Jr., Cai J., Lynn M.J., Sternberg P., Jr. Redox state of glutathione in human plasma. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:625–635. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jones D.P., Mody V.C., Jr., Carlson J.L., Lynn M.J., Sternberg P., Jr. Redox analysis of human plasma allows separation of pro-oxidant events of aging from decline in antioxidant defenses. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:1290–12300.43. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01040-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.So J.H., Boudjouk P., Hong H.H., Weber W.P. Hexamethyldisilathiane. Inorgan. Synth. 1992:30–32. [Google Scholar]

- 44.El-Shinawi H., Cussen E.J., Corr S.A. Selective and facile synthesis of sodium sulfide and sodium disulfide polymorphs. Inorg. Chem. 2018;57:7499–7502. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.8b00776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.