Introduction

Leukemia is a hematologic malignancy with common cutaneous manifestations, including nonspecific and specific skin changes.1 Nonspecific skin changes are inflammatory or related to bone marrow failure, whereas specific skin changes are direct extension of leukemia into the skin, termed leukemia cutis (LC).1 Nonspecific changes are common, occurring in 30% to 40% of patients, whereas LC occurs in 4% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia, and less frequently in chronic myeloid leukemia.1 LC is rare in chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML), a myeloid neoplasm with characteristics of both myelodysplastic syndrome and myeloproliferative neoplasm.2,3

Erythroderma, or generalized exfoliative dermatitis, is characterized by erythema and scale involving greater than 90% of the body surface area.4 Common causes include underlying dermatoses, drug reactions, or malignancy.4 Rapid identification and treatment, including addressing the underlying cause, are critical as associated metabolic abnormalities can be fatal. Here we present a case of erythroderma in a patient with CMML consistent with LC. Informed consent was obtained.

Case report

An 88-year-old patient with a past medical history of CMML, chronic kidney disease, and type 2 diabetes mellitus presented to dermatology with an acutely worsening rash on the trunk and bilateral extremities of 1-week duration. The rash was associated with diffuse scale, pruritus, and chills. The patient had no new or changed medications or recent illnesses but had persistent worsening monocytosis for 3 months consistent with hematologic CMML progression. The patient had originally presented to dermatology 2.5 years ago with reddish-purple papules and nodules on the trunk and extremities (Fig 1); skin biopsy at that time revealed an atypical pan-dermal infiltrate composed of CD4+, CD43+, and CD56+ lymphoid cells, CD163+ monocytes, and absent myeloperoxidase (MPO) expression (Fig 2). Concurrently, a bone marrow biopsy was hypercellular with an increase in large mononuclear CD4+ and CD43+ cells with irregular nuclear borders, mild myeloid hyperplasia with monocytosis, increased CD68+ and CD163+ monocytes, and trilineage dyspoiesis. Taken together with the patient's peripheral blood monocytosis, the skin rash at that time was diagnosed as LC from the underlying CMML. This episode of LC resolved with topical steroids, topical petrolatum, and oral hydroxyurea 500 mg 3 times weekly.

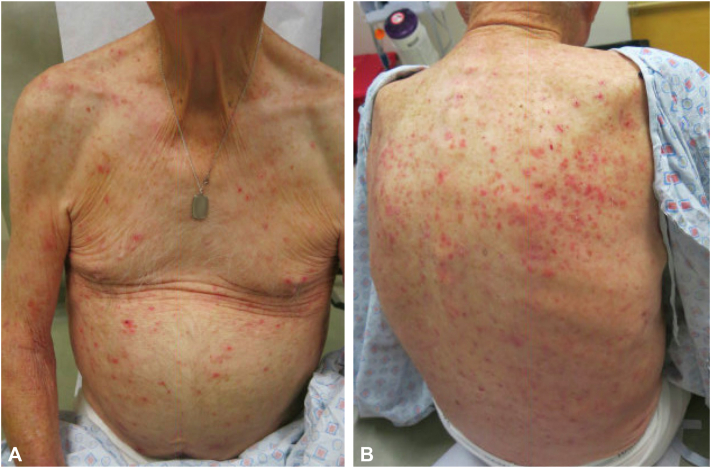

Fig 1.

Initial presentation of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia with biopsy-proven leukemia cutis. Nonscaly erythematous papules and nodules scattered on the chest, abdomen, and right upper extremity (A) and back (B).

Fig 2.

Punch biopsy, left thigh, H&E stain, scanning (A) and high power (B), showing an atypical pan-dermal lymphoid infiltrate. H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin.

Physical examination upon this subsequent presentation to dermatology was notable for confluent erythematous plaques with diffuse scale on the trunk and extremities with body surface area greater than 90%, consistent with erythroderma (Fig 3). A punch biopsy of the left chest revealed an atypical CD4+ and CD43+ lymphoid infiltrate with absent MPO expression. The patient was admitted for intravenous fluids and management of erythroderma. Labs revealed no eosinophilia and unremarkable renal and liver function tests. Flow cytometry, routine blood counts, and peripheral smear were consistent with the patient's known CMML with no disease transformation. During this admission, hydroxyurea was increased to 500 mg twice daily, and the erythroderma was treated with triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily under occlusion and liberal emollients.

Fig 3.

Erythroderma in a patient with chronic myelomonocytic leukemia. Confluent erythema coalescing into plaques with diffuse scale on the chest, abdomen, (A) and back (B).

The patient re-presented to dermatology 2 weeks after discharge with no improvement of rash. A repeat biopsy of the left abdomen was similar to the biopsy 2 weeks prior, with a non-epidermotropic lichenoid infiltrate composed of atypical hyperchromatic cells staining CD4+ and CD43+ (Fig 4). The patient's clinical course was complicated by impetigo on the bilateral lower extremities, which resolved with doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for 1 week. Due to minimal improvement of erythroderma with triamcinolone, the patient was prescribed halobetasol 0.05% ointment twice daily, which provided partial improvement. Additionally, the patient's hydroxyurea was discontinued, and the patient was started on a cycle of azacitidine 100 mg subcutaneously on day 1-4 and 7-9, repeat every 28 days, with resolution of the erythroderma. Hydroxyurea was resumed at a dose of 500 mg every other day at the beginning of the second cycle.

Fig 4.

Punch biopsy, left abdomen, H&E stain, scanning (A) and high power (B), showing a non-epidermotropic lichenoid infiltrate composed of atypical hyperchromatic cells. H&E, Hematoxylin and eosin.

Discussion

Herein, we present a case consistent with erythrodermic LC from CMML. In the setting of hematologic CMML progression, the patient's clinical presentation supports this diagnosis given the similarities between the infiltrates in the erythrodermic skin biopsies and prior bone marrow and skin biopsies as well as the rapid resolution of the patient's erythroderma with CMML treatment. A prior study examining immunohistochemical characteristics in myeloid LC found 97% of cases were CD43+, and among the 58% that were MPO negative, all were also CD43+ and CD68+. This is similar to our case, where atypical cells on bone marrow and skin biopsies were CD43+, and bone marrow biopsy revealed increased CD68+ monocytes.5 Additionally, CD4+ and CD56+ staining have also been reported in subsets of CMML LC.3 Blastic plasmacytoid dendritic cell neoplasm also frequently has CD4+/CD56+ infiltrates associated with cutaneous findings,3 but was ruled out via negative CD123 staining on bone marrow biopsy. A limitation of this report is that we cannot entirely exclude a paraneoplastic manifestation of worsening CMML as a cause of the patient's erythrodermic eruption. Lack of new or changed medications and lack of eosinophilia made a drug eruption less likely.

Clinical characteristics of LC in CMML vary with heterogeneous histopathologic features, typically manifesting as cutaneous papules or nodules composed of blast cells with either monocytic or granulocytic differentiation.3 LC in patients with CMML is considered a prognosticator of disease progression to acute leukemia. Thus, patients with CMML and LC often receive more aggressive treatment.2,3 In this case, flow cytometry, routine blood counts, and peripheral blood smear evaluation ruled out disease transformation. Strazzula et al reported a case of LC in a patient with CMML precipitating CMML crisis complicated by tumor lysis syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and death, highlighting the importance of monitoring these patients for signs of leukemic transformation or crises.2 Fortunately, our patient has not experienced such complications.

Few cases of erythrodermic LC have been reported in the literature (Table I). Clinicians should be aware of LC as a rare cause of erythroderma and order histopathologic evaluation in suspected cases. Clinicians should also note that erythroderma due to LC can be recurrent and can occur before (aleukemic LC), at, or after diagnosis (Table I). Of the cases reported in the literature, 4 of 10 cases were fatal (40%); erythrodermic LC should therefore prompt close oncology follow-up and treatment.

Table I.

Reported cases of erythroderma secondary to leukemia cutis

| Report | Age, sex | Leukemia subtype | Chronology of erythroderma | Recurrent erythroderma | Treatment | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Su et al,6 1984 | NR, 2 cases | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| De Coninck et al,7 1986 | 57, M | Acute myelomonocytic leukemia | 1st: Aleukemic LC, 2nd: concomitant | Yes | 2nd: Vincristine, adriamycin, prednisone, and cytosine arabinoside | 1st: Spontaneous regression. 2nd: Regression 1 wk, death 1 mo |

| Sigurdsson et al,8 1996 | NR | Chronic lymphocytic leukemia | NR | NR | NR | Death |

| Jeong et al,9 2009 | 82, M | T-cell prolymphocytic leukemia | Concomitant | NR | Fludarabine and prednisone | Death, 2 wk |

| Raj et al,10 2011 | 75, M | Chronic myeloid leukemia | Concomitant | Yes | Imatinib | Resolution, 3 mo |

| Novoa et al,11 2015 | 65, F | Pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia | After diagnosis | NR | Hospice | Death |

| Coen and Serratrice,12 2016 | 74, M | Atypical chronic lymphocytic leukemia | Concomitant | No | Conservative management | Asymptomatic for 2 years then lost to f/u |

| Donaldson et al,13 2019 | 50, F | Acute myeloid leukemia | After diagnosis | No | Reinduction therapy with high-dose cytarabine | Resolution, 2 wk |

| Current case, 2022 | 88, M | Chronic myelomonocytic leukemia | After diagnosis | No | Topical steroids, azacitidine | Resolution, 4 mo |

F, Female; f/u, follow-up; LC, leukemia cutis; M, male; NR, not reported.

Conflicts of interest

None disclosed.

Footnotes

Funding sources: Dr Hartman is supported by the Melanoma Research Foundation and a VISN-1 Career Development Award. Author Trepanowski is supported by the Melanoma Research Foundation.

IRB approval status: Not applicable.

Patient consent: Consent for the publication of all patient photographs and medical information was provided by the authors at the time of article submission to the journal stating that all patients gave consent for their photographs and medical information to be published in print and online and with the understanding that this information may be publicly available.

References

- 1.Osmola M., Gierej B., Kłosowicz A., et al. Leukaemia cutis for clinicians, a literature review. Adv Dermatol Allergol. 2021;38(3):359–365. doi: 10.5114/ada.2021.107923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leukemia cutis in the setting of CMML: a predictor for leukemic transformation. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70(5):AB117. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.01.485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qiao Y., Jian J., Deng L., Tian H., Liu B. Leukaemia cutis as a specific skin involvement in chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia and review of the literature. Transl Cancer Res. 2020;9(8):4988–4998. doi: 10.21037/tcr-19-2882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okoduwa C., Lambert W.C., Schwartz R.A., et al. Erythroderma: review of a potentially life-threatening dermatosis. Indian J Dermatol. 2009;54(1):1–6. doi: 10.4103/0019-5154.48976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cronin D.M.P., George T.I., Sundram U.N. An updated approach to the diagnosis of myeloid leukemia cutis. Am J Clin Pathol. 2009;132(1):101–110. doi: 10.1309/AJCP6GR8BDEXPKHR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Su W.P., Buechner S.A., Li C.Y. Clinicopathologic correlations in leukemia cutis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1984;11(1):121–128. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(84)70145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Coninck A., De Hou M.F., Peters O., Van Camp B., Roseeuw D.I. Aleukemic leukemia cutis. Dermatology. 1986;172(5):272–275. doi: 10.1159/000249354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sigurdsson V., Toonstra J., Hezemans-Boer M., van Vloten W.A. Erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(1):53–57. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(96)90496-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jeong K., Lew B., Sim W. Generalized leukaemia cutis from a small cell variant of T-cell prolymphocytic leukaemia presenting with exfoliative dermatitis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89(5):509–512. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raj A., Rai R., Rangarajan B. Exfoliative dermatitis with leukemia cutis in a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia: a rare association. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77(2):208. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.77471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Novoa R.A., Wanat K.A., Rosenbach M., Frey N., Frank D.M., Elenitsas R. Erythrodermic leukemia cutis in a patient with pre-B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37(8):650–652. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coen M., Serratrice J. Leukemia cutis: an atypical case. Am J Med. 2016;129(12):e341–e342. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2016.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donaldson M., Ebia M.I., Owen J.L., Choi J.N. Rare case of leukemia cutis presenting as erythroderma in a patient with acute myeloid leukemia. JAAD Case Rep. 2019;5(2):121–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2018.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]