Abstract

Symptoms of long coronavirus disease (COVID) were found in 38% of 170 patients followed for a median of 22.6 months. The most prevalent symptoms were fatigue, affected taste and smell, and difficulties remembering and concentrating. Predictors for long COVID were older age and number of symptoms in the acute phase. Long COVID may take many months, maybe years, to resolve.

Keywords: COVID-19, long-COVID, persistent symptoms, longitudinal study, Faroe Islands

Two years into the pandemic, there have been >400 million confirmed cases of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) worldwide and a suspected high number of undetected cases. Meanwhile, several studies have documented long-term effects of COVID-19, or long COVID [1], implying a considerable public health concern and potential health care burden worldwide. The duration of long COVID is still uncertain as, in most studies, patients still have attributable signs and symptoms at last assessment up to 12 months after infection [2–7]. To our knowledge, symptom persistence beyond 1 year of follow-up has not been evaluated. We have previously described the prevalence of symptoms 4 months after severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in a prospective cohort of 180 mainly nonhospitalized cases where more than half of the participants reported persistent symptoms [8]. In this prospective study, we present long-term symptoms in the same cohort 23 months after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

METHODS

Data Collection

All patients with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection from March 2020 to April 2020 in the Faroe Islands were invited to participate. Recruitment has been described elsewhere [8]. Participants (n = 180) were interviewed by phone, and symptoms were assessed using a standardized questionnaire [8]. The last follow-up was conducted 19–23 months after disease onset, between November 2021 and January 2022. Questions regarding recovery, memory, and concentration were only asked at last follow-up as the long-term neurological complications of COVID-19 were not known at the beginning of the pandemic. Patients were also asked to report problems of memory and concentration before COVID-19 infection.

Patient Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Faroese Research Ethics Committee and Data Protection Agency approved the study.

Statistical Analyses

We defined long COVID as a condition occurring after SARS-CoV-2, with symptoms present at least 3 months after infection and symptoms lasting at least 2 months [9]. Logistic regression was used to investigate potential predictors of long COVID including sex, age group/age, smoking (ever/never), body mass index (BMI), medication use (yes/no), chronic diseases (yes/no), and number of symptoms in the acute phase. Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS, version 25.

RESULTS

Of the 180 participants at baseline, 170 participated in the last follow-up; 1 had withdrawn from the study, 1 was an initial false-positive case and did not receive a follow-up call, and 8 were lost to follow-up, resulting in a 94% participation rate (170/180). Participation characteristics are displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants at 23-Month Follow-up—Overall and Stratified Based on Reporting Symptoms

| Alla | Persistent Symptomsb | No Symptomsc | P Valued | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 170 | n = 65 | n = 105 | ||

| Sex, women, No. (%) | 93 (54.7) | 38 (58.5) | 55 (52.4) | .4 |

| Age at symptom onset, mean (SD), y | 40.0 (19.4) | 45.1 (18.5) | 36.9 (19.3) | .03 |

| No. of symptoms during acute phase, mean (SD) | 7.6 (3.6) | 8.8 (3.7) | 6.8 (3.2) | .001 |

| Body mass indexe, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 25.7 (5.3) | 26.7 (5.6) | 25.0 (4.9) | .2 |

| Ever smoker, No. (%)f | 74 (44.8) | 34 (53.1) | 40 (39.6) | .4 |

| Hospitalized, No. (%) | 4 (2.4) | 4 (100.0) | 0 | N/A |

| Chronic disease, No. (%) | 54 (31.8) | 24 (36.9) | 30 (28.6) | .7 |

| Daily medication use, No. (%) | 59 (34.7) | 24 (36.9) | 35 (33.3) | .2 |

| Age groups, No. (%) | .1 | |||

| 0–17 y | 21 (12.4) | 4 (6.2) | 17 (16.2) | |

| 18–34 y | 50 (29.4) | 16 (24.6) | 34 (32.4) | |

| 35–49 y | 39 (22.9) | 17 (26.2) | 22 (21.0) | |

| 50–67 y | 43 (25.3) | 18 (27.7) | 25 (23.8) | |

| 67+ y | 17 (10.0) | 10 (15.4) | 7 (6.7) |

Follow-up, median (range), months: 21.6 (19.3–22.9).

Follow-up, median (range), months: 20.2 (19.3–22.9).

Follow-up, median (range), months: 21.7 (19.4–22.9).

Logistic regression.

Data missing for 37 participants.

Data missing for 5 participants.

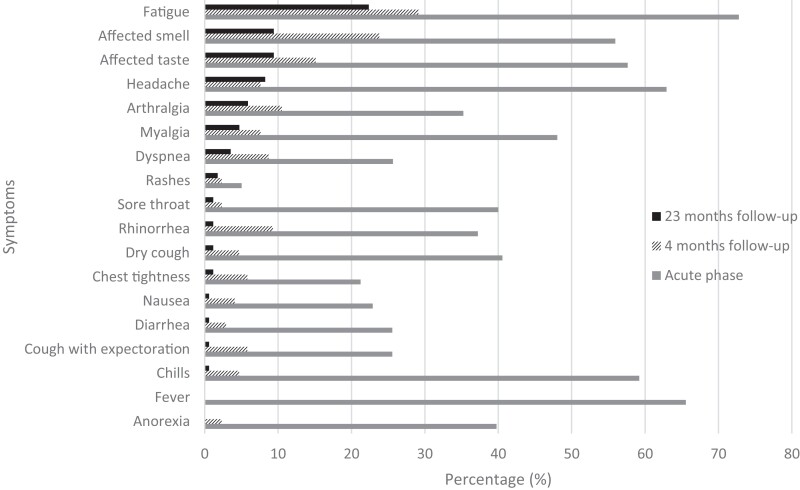

At follow-up, a median (range) of 22.6 (19.3–22.92) months after disease onset, 65 (38%) individuals, 38 women and 27 men, reported at least 1 symptom. The majority (n = 52) only reported 1 or 2 symptoms, while 13 reported 3 or more symptoms. Six individuals reported 1–3 symptoms as severe at the last follow-up (Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1). The most persistent symptoms were fatigue (22%, 38/170), affected smell (9%, 16/170), and affected taste (9%, 16/170) (Figure 1); 15% (24/160) reported difficulties remembering, and 11% (17/161) reported deterioration of ability to concentrate (Supplementary Table 2). However, 76% (129/170) reported feeling fully recovered, including 24 who reported at least 1 symptom. Among those who reported symptoms at 23-month follow-up, all but 2 reported symptoms at baseline and 15 did not report symptoms at 4-month follow-up.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of self-reported symptoms (percentages) at 23-month follow-up (black bars) compared with the acute phase (gray bar) [8] and 4-month follow-up (patterned bar) [8].

Long COVID, assessed at a median of 23 months after onset, was associated with increasing age (P = .03) and number of symptoms in the acute phase (P = .001) (Table 1; Supplementary Figure 2). These results remained the same in univariable comparisons and when including all potential predictors in a multivariable logistic regression model. Although not statistically significantly so, smokers and individuals with higher BMI were more likely to have symptoms at follow-up (P = .4 and P = .2, respectively).

Four children, all girls aged 1–16 years at baseline, reported 1 or 2 persistent symptoms at follow-up. Three reported headache, and the other symptoms were fatigue and chronic cough.

DISCUSSION

More than one-third of individuals who had COVID-19 during spring 2020 reported still experiencing symptoms almost 2 years after acute infection. On the other hand, 76% reported that they had fully recovered, including some who reported at least 1 symptom at follow-up. Thus, some with persistent symptoms felt fully recovered, while 22% did not feel completely recovered and 2% did not feel that they had recovered at all.

As in the acute phase and at 4-month follow-up [8], the most prevalent persistent symptoms were fatigue, affected smell and taste. Difficulties remembering and concentrating, which we only asked about at the last follow-up, were also prevalent symptoms. This is in line with other studies that have found some of the same prevalent symptoms [2–4]. Most of the participants reported mild and few symptoms, but 7% reported 3 or more symptoms and 4% still experienced symptoms that they rated as severe and affecting them in their daily life. This was especially pronounced for fatigue and memory issues. Persistent symptoms appear to be rarer in children than in adults, with headache being the most common symptom among children in our study; however, none reported affected smell or taste, as has been seen in most studies in children and young people [10, 11].

To our knowledge, no other study has reported symptoms beyond 12 months after COVID-19 infection. Our prevalence estimate of long COVID is somewhat lower but still in line with the few studies assessing long COVID 1 year after infection. A German study (n = 96) including both hospitalized and nonhospitalized patients reported that only 23% of patients were completely free of symptoms 12 months after COVID-19 [3], while 45% of the participants in a Chinese study (n = 2433) reported at least 1 symptom 1 year after discharge from the hospital [6]. In an online Korean survey, this number was 53% (n = 241) [5]. Three Italian studies (n = 304 [2], nonhospitalized subjects; n = 254 [4] and n = 200 [7], hospitalized subjects) reported persistence of at least 1 symptom at 12-month follow-up in 53%, 41%, and 40% of participants. All these studies show that symptoms persist but not to the same degree. The difference observed between studies may be caused by methodological issues, but may also be caused by symptoms being, by definition, subjective and influenced by psychological and cultural factors.

Predictors of long COVID include age [2, 4–6], female sex [2, 4–6], symptoms in the acute phase [2], disease severity [5, 6], and BMI [2]. Thus, our data are in line with the current literature, showing that age and number of symptoms in the acute phase were predictors of long COVID, while a trend was seen with smoking and higher BMI. We did not, however, find any association with sex. The association between the number of symptoms in the acute phase and the risk of long COVID shows that even with a relatively mild disease course as in our study of mainly nonhospitalized participants, the acute phase was predictive of the long-term effects of COVID-19.

The strengths of our study include inclusion shortly after the acute phase and long-term longitudinal follow-up of persistent symptoms, a high participation rate, and a population-based design with broad representation in all age groups, reducing selection and recall bias. One particular limitation is the lack of a control group. People not infected by SARS-CoV-2 have also experienced fatigue and psychological issues during the pandemic [12, 13]. However, most of these symptoms can be expected to decrease as any remaining restrictions are lifted [13], and we therefore believe that our results represent the long-term effects of COVID-19. A further limitation is that we only included cognitive symptoms such as concentration and memory difficulties at follow-up. However, we asked about symptoms before COVID and at follow-up to gauge if the problems were present before COVID. Finally, we present data from the original strain of SARS-CoV-2 in unvaccinated individuals, and thus the results might not generalize to either infection by other COVID-19 variants, or infection in vaccinated individuals.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our findings pinpoint a considerable clinical and public health concern with up to one-third of mainly nonhospitalized COVID-19 patients reporting persistent symptoms almost 2 years after acute infection, despite a relatively mild disease course at the initial stage. Future research is needed to examine both the long-term effects of infection with newer variants and the possible protective effect of vaccines against long COVID.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all the participants in the study.

Financial support. This work was supported by the Cooperation’s p/f Krúnborg and Borgartún.

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Author contributions. Conceptualization: P.W., M.S.P.; investigation: K.D.H., M.E.D., B.M.F., G.H.; formal analysis: M.S.P.; writing first draft: G.H., M.S.P.; review & editing: all authors; funding acquisition: P.W., M.S.P.

Contributor Information

Gunnhild Helmsdal, Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, The Faroese Hospital System, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Katrin Dahl Hanusson, Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, The Faroese Hospital System, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Marnar Fríðheim Kristiansen, Centre of Health Sciences, University of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands; Medical Department, National Hospital of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Billa Mouritsardóttir Foldbo, Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, The Faroese Hospital System, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Marjun Eivindardóttir Danielsen, Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, The Faroese Hospital System, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Bjarni á Steig, Medical Department, National Hospital of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Shahin Gaini, Medical Department, National Hospital of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands; Department of Infectious Diseases, Odense University Hospital, Odense, Denmark; Department of Clinical Research, University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark.

Marin Strøm, Centre of Health Sciences, University of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands; Department of Epidemiology Research, Statens Serum Institut, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Pál Weihe, Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, The Faroese Hospital System, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands; Centre of Health Sciences, University of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Maria Skaalum Petersen, Department of Occupational Medicine and Public Health, The Faroese Hospital System, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands; Centre of Health Sciences, University of the Faroe Islands, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Castanares D, Kohn L, Dauvrin M, et al. Long COVID: Pathophysiology – Epidemiology and Patient Needs. KCE Reports 344. Health Services Research (HSR) Brussels: Belgian Health Care Knowledge Centre (KCE); 2021.

- 2. Boscolo-Rizzo P, Guida F, Polesel J, et al. Sequelae in adults at 12 months after mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 2021; 11:1685–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seeßle J, Waterboer T, Hippchen T, et al. Persistent symptoms in adult patients one year after COVID-19: a prospective cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 74:1191–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fumagalli C, Zocchi C, Tassetti L, et al. Factors associated with persistence of symptoms 1 year after COVID-19: a longitudinal, prospective phone-based interview follow-up cohort study. Eur J Intern Med 2022; 97:36–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kim Y, Bitna H, Kim S-W, et al. Post-acute COVID-19 syndrome in patients after 12 months from COVID-19 infection in Korea. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhang X, Wang F, Shen Y, et al. Symptoms and health outcomes among survivors of COVID-19 infection 1 year after discharge from hospitals in Wuhan, China. JAMA Netw Open 2021; 4:e2127403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bellan M, Baricich A, Patrucco F, et al. Long-term sequelae are highly prevalent one year after hospitalization for severe COVID-19. Sci Rep 2021; 11:22666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Petersen MS, Kristiansen MF, Hanusson KD, et al. Long COVID in the Faroe Islands – a longitudinal study among non-hospitalized patients. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e4058–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Soriano JB, Murthy S, Marshall JC, Relan P, Diaz JV; WHO Clinical Case Definition Working Group on Post-COVID-19 Condition . A clinical case definition of post-COVID-19 condition by a Delphi consensus. Lancet Infect Dis 2022; 22:e102–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Behnood SA, Shafran R, Bennett SD, et al. Persistent symptoms following SARS-CoV-2 infection amongst children and young people: a meta-analysis of controlled and uncontrolled studies. J Infect 2022; 84:158–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Blomberg B, Mohn KG-I, Brokstad KA, et al. Long COVID in a prospective cohort of home-isolated patients. Nat Med 2021; 27:1607–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Davidsen AH, Petersen MS. The impact of COVID-19 restrictions on mental well-being and working life among Faroese employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18:4775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jiang D, Chen J, Liu Y, et al. Patterns of mental health problems before and after easing COVID-19 restrictions: evidence from a 105248-subject survey in general population in China. PloS One 2021; 16:e0255251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.