Abstract

Human two-pore channels (TPCs) are endolysosomal cation channels and play an important role in NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release and endomembrane dynamics. We found that YM201636, a PIKfyve inhibitor, potently inhibits PI(3,5)P2-activated human TPC2 with an IC50 of 0.16 μM. YM201636 also effectively inhibits NAADP-activated TPC2 and a constitutively-open TPC2 L690A/L694A mutant channel; whereas it exerts little effect when applied in the channel’s closed state. PI-103, a YM201636 analog and an inhibitor of PI3K and mTOR, also inhibits human TPC2 with an IC50 of 0.64 μM. With mutational, virtual docking, and molecular dynamic simulation analyses, we found that YM201636 and PI-103 directly block the TPC2’s open-state channel pore at the bundle-cross pore-gate region where a nearby H699 residue is a key determinant for channel’s sensitivity to the inhibitors. H699 likely interacts with the blockers around the pore entrance and facilitates their access to the pore. Substitution of a Phe for H699 largely accounts for the TPC1 channel’s insensitivity to YM201636. These findings identify two potent TPC2 channel blockers, reveal a channel pore entrance blockade mechanism, and provide an ion channel target in interpreting the pharmacological effects of two commonly used phosphoinositide kinase inhibitors.

Subject terms: Ligand-gated ion channels, Pharmacology

YM201636 and PI-103 are potent inhibitors of human two-pore channel 2 that act through a channel pore entrance blockade mechanism.

Introduction

Two-pore channels (TPCs) are mainly found in acidic organelles of endolysosomes in animals and also vacuoles in plants. Humans and mice have two functional TPC isoforms: TPC1, which is broadly expressed in different stages of endosomes and lysosomes, and TPC2, which is expressed mainly in late-stage endosomes and lysosomes1,2. TPCs are homodimeric cation channels. Each subunit contains two transmembrane domains of the basic structural unit (six transmembrane segments and a pore loop) of a voltage-gated ion channel. TPCs are potently activated by phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate (PI(3,5)P2)3–6, inhibited by ATP via mTORC17, and slightly blockaded by cytoplasmic and luminal Mg2+ 5. Human TPC1 is voltage-gated and regulated by cytoplasmic and luminal Ca2+ 8, whereas human TPC2 is not sensitive to voltage or Ca2+ 5. The recently reported cryo-electron microscopic (Cryo-EM) structures of mouse TPC19 and human TPC210 have provided a structural basis for understanding TPC function.

The endolysosomal TPCs regulate the function of the endolysosomal system, including endomembrane dynamics and Ca2+ homeostasis of the acidic stores3,11. Accumulating evidence supports that TPCs are critical to NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release from acidic stores1,12–18. TPCs are involved in many cellular processes, including autophagy19, migration and proliferation of cancer cells20,21, muscle cell differentiation22 and contraction16, and fertilization23, and they are implicated in pigmentation24–26, Parkinson’s disease27, and fatty liver disease28,29. TPCs are also important to infection mechanisms of viruses, such as Ebola30, MERS31, and SARS-COV-232.

Potent and/or selective modulators are important pharmacological tools in understanding molecular mechanisms and physiological and pathological function of an ion channel. Currently, the availability of potent and/or selective antagonists of TPCs remains limited. Ned-19 (trans-Ned 19) is a commonly used as an NAADP signaling antagonist33, albeit it also blocked PI(3,5)P2-induced TPC current30 and formed complex with plant TPC1 in solved X-ray structure34. The potency of Ned-19 in TPC inhibition remains unclear as only a high concentration (200 µM) of Ned-19 was reported to be associated with a significant inhibition (~75%) lysosomal TPC2 activity30. Naringenin, a modulator of multiple ion channels, can inhibit TPCs when applied at high concentrations (an IC50 of ~200 µM)35, likely via the blockade of the channel pore. Tetrandrine, a voltage-gated Ca2+ (CaV) channel blocker, was reported to inhibit Ebola virus entry into host cells presumably via inhibition of TPCs30. However, tetrandrine is hardly an optimal TPC antagonist because of its issue in specificity and currently the lack of reported full inhibition of lysosomal TPC2 currents, e.g., 50–60% inhibition by 0.5 µM30 and 10 µM tetrandrine21, in spite of its potent effect on virus entry (IC50 of 55 nM)30. SG-094, a chemical derivative of tetrandrine, was recently developed to have some improved inhibitory effect (~75% by 10 µM) on TPC221. MT-8, a flavonoid compound isolated from plant extracts, was recently identified to inhibit lysosomal TPC2 effectively with an IC50 of 2.6 µM36. Some other CaV and NaV channel antagonists, such as nifedipine and lidocaine, were also found to inhibit NAADP-evoked Ca2+ elevation in cells and had been proposed to act as antagonists of TPCs37. But, electrophysiological evidence for TPC inhibition by these CaV and NaV antagonists is lacking.

We considered two candidates. YM201636 is a potent and selective inhibitor (an IC50 of ~30 nM) of PIKfyve, the principal phosphoinositide kinase that produces PI(3,5)P2 via PtdIns3Pphosphorylation38,39. Given that PI(3,5)P2 is a key component and regulator of the endolysosomal system, YM201636 is widely used in research studies to disrupt endomembrane transport, e.g., to prevent infection by Zaire ebolavirus and SARS-COV-232,40 or to inhibit retroviral release from infected cells41. Similarly, PI-103 is a potent multi-target inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K), mammalian target of rapamycin complex (mTOR), and DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK)42. PI-103 has nearly the same chemical structure as YM201636 but without YM201636’s 6-amino-nicotinamide group. In this study, we identified YM201636 and PI-103 as potent inhibitors of human TPC2 channels, and we further investigated and identified the mechanisms underlying their inhibitory effects on TPCs.

Results

YM201636 suppressed NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release and TPC2 activation

TPC channel activities are dually modulated by two endogenous signaling molecules: NAADP and PI(3,5)P2. We tested whether suppression of PI(3,5)P2 production by application of a PIKfyve inhibitor, YM201636, can affect NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release. We observed that direct microinjection of YM201636 (1 µM) together with NAADP led to a great reduction of the NAADP-evoked Ca2+ elevation by 80% in HEK293 cells (Fig. 1a, b). However, the cells’ response to NAADP was largely unaffected upon microinjection of apilimod, another potent PIKfyve inhibitor (Fig. 1a, b). Taking advantage of our recently reported method of measuring NAADP-evoked TPC2 activation18 using the plasma membrane–targeted TPC2 L11A/L12A mutant (TPC2PM) channels9,10, we examined the inhibitory effect of YM201636 on NAADP-induced TPC2PM currents in whole cell recording. We recorded the NAADP microinjection-induced TPC2PM currents as we recently reported18. The presence of 1 µM YM201636 in the bath solution caused 78% inhibition of the NAADP-induced TPC2PM currents (Fig. 1c, d). Apilimod at 1 µM exerted little effect on NAADP (microinjection)-induced TPC2PM activation (Fig. 1c, d). These results indicate that YM201636 inhibits NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release and TPC2 activation in a manner unrelated to PIKfyve because of the lack of effect from apilimod.

Fig. 1. YM201636 inhibits NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release and TPC2 activation.

a Time course of NAADP (microinjection)-induced change in fluorescence of Ca2+ indicator in TPC2-expressing HEK293 cells. NAADP (100 nM), YM201636 (1 µM), and apilimod (1 µM) were included in the injection pipette solution and applied inside cells via microinjection. b Averaged NAADP-induced changes in Ca2+ indicator fluorescence in TPC2-expressing HEK293 cells. c Averaged traces of NAADP (1 μM in pipette solution) microinjection-induced whole cell currents in HEK293 cells transfected with TPC2PM mutant construct. YM201636 (1 µM) and apilimod (1 µM) were incubated with cells in bath solution for ~ 10 min before recording. d Averaged current density of NAADP microinjection-induced whole cell TPC2PM currents at −120 mV. The averaged data are presented as mean value ± SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) was used to calculate p values. ****, *, and ns are for p values ≤ 0.0001, 0.05, and > 0.05, respectively.

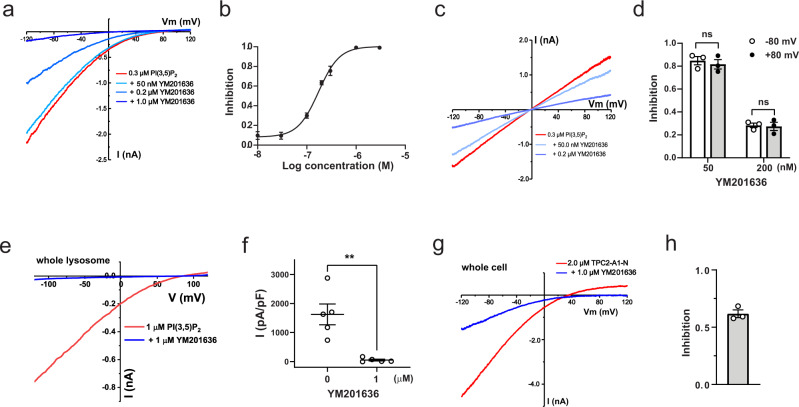

YM201636 directly inhibits TPC2 channels

We performed inside-out patch-clamp recording of the TPC2PM currents to determine whether YM201636 can directly act on the channel. We observed that YM201636 application from the cytosolic side at sub-micromolar concentrations directly inhibited PI(3,5)P2-induced human TPC2 channel Na+ currents (Fig. 2a). YM201636 potently inhibited TPC2 channels in an antagonist concentration-dependent manner with a low IC50 of 0.16 μM (Fig. 2b). YM201636’s inhibition of the human TPC2 channel was voltage-independent, as shown by the similar levels of inhibition of outward and inward Na+ currents elicited by PI(3,5)P2 at negative and positive voltages (Fig. 2c, d). To confirm that YM201636 also inhibits the wild type TPC2 expressed on lysosomes, we performed patch clamp recording of whole lysosome (enlarged by vacuolin-1 treatment). As expected, 1 µM YM201636 when applied from the cytosolic side fully abolished the PI(3,5)P2-induced lysosomal TPC2 currents (Fig. 2e, f).

Fig. 2. YM201636 directly inhibits human TPC2 channels.

a, b Representative current traces (a) and plot of the averaged dose response (b) of the inhibitory effect of YM201636 on the TPC2PM Na+ currents elicited by 0.3 μM PI(3,5)P2. Path-clamp recording was done in inside-out configuration using asymmetric Na+ (outside)/K+ (inside) recording solutions. The data (n = 6–8 for each data point) in (b) were fit by a Hill equation. c Representative current traces of the TPC2PM Na+ currents recorded in inside-out configuration using symmetric Na+ recording solutions in the absence and presence of 50 nM or 0.2 µM YM201636. d Averaged inhibitory effects of YM201636 on the outward and inward TPC2PM currents recorded at +80 and −80 mV as shown in (c). e, f Representative current traces (e) and averaged plot (f) of the effects of 1 µM YM201636 on 1 µM PI(3,5)P2-induced TPC2 Na+ currents in whole lysosome patch-clamp recording using asymmetric K+ (cytosolic)/Na+ (lumenal) recording solutions. g, h Representative current traces (g) and averaged plot at −120 mV (h) of the effect of 1 µM YM201636 perfused on the extracellular side on TPC2PM channel currents elicited by extracellularly applied TPC2-A1-N in whole cell patch-clamp recording using asymmetric Na+ (outside)/K+ (inside) recording solutions. The averaged data are presented as mean value ± SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) was used to calculate p values. ** and ns are for p values ≤ 0.01 and > 0.05, respectively.

Given the lipophilic property of YM201636, we expected it can also inhibit TPC2PM when applied from extracellular side. To test this, we performed whole-cell recording and applied the inhibitor from the extracellular side, which is analogous to the lumenal side of the lysosome. In this experiment, we activated the TPC currents by perfusion of a membrane permeable activator TPC2-A1-N43 on the extracellular side because of the difficulty in manipulation of intracellular application of PI(3,5)P2 in whole cell recording. TPC2-A1-N was considered to be more like NAADP than PI(3,5)P2 in TPC2 activation43. We observed that YM201636 at 1 µM caused significant (62 ± 3%, n = 3) inhibition of the TPC2-A1-N-induced TPC2PM currents when it was perfused together with the activator from the extracellular side (Fig. 2g, h). The observed reduced inhibition under this condition as compared to when it was applied on the cytosolic side in inside-out configuration likely suggests favorable accessibility of the inhibitory site from the cytosolic side. The concentration of the inhibitor could be lower inside cells than the outside solution, caused by insufficient equilibration of the chemical across membrane during perfusion and also dilution by the pipette solution once the inhibitor is inside the cell.

The open state-dependence of YM201636’s inhibition on TPC2

PI(3,5)P2, when applied from the cytosolic side, activated human TPC2 channels with an observed activation rate of a τon of 9.0 ± 0.5 s (n = 8), and the effect could be washed off within 1–2 min with a deactivation rate of a τoff of 20.8 ± 0.9 s (n = 7) (Fig. 3a, d). The time constant τ is equal to the time taken for a change by a factor of 1- 1/e or ~0.632. We found YM201636 inhibited the human TPC2 channel quickly with a τon of 3.4 ± 0.9 s (n = 5) when the channels were pre-activated by PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 3b, d). The wash-off of YM201636 in the presence of PI(3,5)P2, i.e., in the open state, was slow at a τoff rate of 58.5 ± 3.8 s (n = 5) (Fig. 3b, d). To determine the state dependence of inhibitor’s action on the channel, we applied YM201636 when the channels were in the closed state, i.e., in the absence of PI(3,5)P2 for 2 min, followed by activating the channels by PI(3,5)P2 in the absence of YM201636 (Fig. 3c). We found that the rising rate of TPC2 currents activated by PI(3,5)P2 in the presence YM201636 pre-application remained fast (τon = 12.0 ± 1.0 s; n = 5) (Fig. 3c, d), which is comparable to that (τ = 9.0 s) in the absence of YM201636 pre-application (Fig. 3a, d) but much faster than the wash-off rate (τ = 58.5 s) of YM201636 (Fig. 3b, d). This suggests that YM201636 barely binds to TPC2 for channel inhibition in the closed state. To determine the state-dependence of YM201636’s dissociation from the channel, we evaluated the wash-off rate of YM201636 in the channel’s closed state, i.e., in the absence of activator. After the channels were inhibited by YM201636 in the presence of PI(3,5)P2, we washed the excised patches (inside-out) with the bath solution alone (no PI(3,5)P2 and YM201636) on the intracellular side for different time lengths and then applied PI(3,5)P2 to check the residual inhibitory effect of YM201636 on the rate of channel activation by PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 3e–g). The observed activation rates were τ (sec) = 34.1 ± 1.7 (n = 7), 19.4 ± 1.9 (n = 5), and 11.3 ± 0.6 (n = 6) after a 40, 80 and 120 s wash with the bath solution, respectively ((Fig. 3e–h). The time course of the wash time dependent increase in the channel activation rate can be fitted with a τ of 52 s (Fig. 3h), which is close to the wash-off rate (τ = 59 s) of YM201636 in the presence of PI(3,5)P2 (Fig. 2b, d). Therefore, YM201636 mainly binds to and inhibit the channels when the channels are activated, whereas its dissociation is largely independent of the presence or absence of PI(3,5)P2 or the channel’s activation status.

Fig. 3. The state dependence of human TPC2 inhibition by YM201636.

a Representative TPC2PM currents upon activation by 1.0 μM PI(3,5)P2 and deactivation by wash-off of the ligand. b The inhibition and restoration of TPC2PM currents (pre-activated by PI(3,5)P2) upon wash-on and wash-off of 1.0 μM YM201636. c The PI(3,5)P2 (1.0 μM)-induced TPC2PM currents after 2-min treatment of the closed channels (in the absence of an activator) with 1.0 μM YM201636. d Averaged kinetics (Tau) of TPC2PM currents in the absence and presence of YM201636 and/or PI(3,5)P2 as shown in (a–c) (n = 5–8). e–g The time-dependence of YM201636 wash-off in the absence of an activator. The PI(3,5)P2-actatived TPC2PM was first inhibited by YM201636 and then washed with the bath solution (no activator) for 40 s (e) 80 s (f) 120 s (g). The residual inhibitory effect of YM201636 was assayed by the slowed kinetics of PI(3,5)P2-induced TPC2PM activation. h The averaged kinetics (Tau) of PI(3,5)P2- induced restoration of TPC2PM currents (pre-inhibited by YM201636) after wash-off of the inhibitor by bath solution for different times as shown in (e–g) (n = 5–8). The 0 s data was taken from (b). All currents were acquired at −120 mV in inside-out configuration using asymmetric Na+ (outside)/K+ (inside) recording solutions. The traces were fitted exponentially to obtain the Tau values. The averaged data are presented as mean value ± SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) was used to calculate p values. ****, ***, * are for p values ≤ 0.0001, ≤0.001, and ≤ 0.05, respectively.

The ligand-independence of YM201636’s inhibition of TPC2

To determine whether the inhibition of TPC2 by YM201636 is specific to any ligand activation pathway, we managed to generate a constitutively open TPC2PM mutant channel. We performed Ala-substitution mutations in the T308, Y312, L690, and L694 residues (Fig. 4a), which have been predicted from human TPC2 structures to form a bundle-crossing activation gate on the cytosolic side of the channel pore10. We were unable to obtain functional channels from the single mutation of L690A or L694A. However, the double mutant channel L690A/L694A produced Na+ currents in the absence of any agonist, and application of PI(3,5)P2 did not increase the currents (Fig. 4b), indicating that the channels are already constitutively fully open. This result provides functional evidence that these two residues are indeed involved in the formation of the activation gate. The T308A and Y312A mutant channels remained closed in the absence of an agonist and were sensitive to PI(3,5)P2 for channel activation, suggesting that these two residues are less important in activation pore-gate formation. With the L690A/L694A mutant channel in the absence of an agonist, we observed that YM201636 could still reduce the channel’s constitutively open currents in a concentration-dependent manner, with an IC50 of 0.54 μM (Fig. 4c, d). Together with the above observed the YM201636’s inhibition of TPC2 activated by PI(3,5)P2, NAADP, or TPC2-A1-N, this result clearly indicates that the YM201636’s inhibition of TPC2 is independent of activation pathways. This inhibitory property of YM201636 agrees with a channel pore blocker. The more than 3-fold increase of YM201636’s IC50 by the L690A/L694A double mutation also suggests a role of the pore structure in TPC2 inhibition by this inhibitor. Therefore, we consider YM201636 most likely a TPC2 open-channel pore blocker.

Fig. 4. The effects of YM201636 on human TPC2 pore region mutants.

a Pore region structures of the PI(3,5)P2-bound open-state (colored) (PDB ID: 6NQ0) and apo/closed-state (gray) (PDB ID: 6QN1) human TPC2 channels showing the positions of the mutated residues in this study. b The constitutively-open TPC2PM currents induced by the L690A/L694A double mutation in the absence and presence of PI(3,5)P2. c The inhibition of the constitutively-open TPC2PM/L690A/L694A channel currents by YM201636. d The dose-response of YM201636’s inhibition on the constitutively-open TPC2PM/L690A/L694A channel currents (n = 4–6) as compared to that of the WT channels. e The averaged inhibitory effects of 1.0 μM YM201636 on TPC2PM pore-region mutant channels. The channels were activated by 0.3 μM PI(3,5)P2. f–h The inhibitory effects of YM201636 on human TPC2PM mutants Y312A (f), H699A (g), and Y312A/H699A (h). i Dose-responses (n = 4–6 for each data point) of the YM201636’s inhibitory effect on TPC2PM mutants Y312A, H699A, Y312A/H699A as compared to that of the WT channels. All recordings were done in inside-out configuration using asymmetric Na+ (inside)/K+ (outside) (b–c) or Na+ (outside)/K+ (inside) (e–h) recording solutions. The averaged data are presented as mean value ± SEM. Unpaired Student’s t-test (two tailed) was used to calculate p values. ****, ***, ** are for p values ≤ 0.0001, ≤0.001, and ≤0.01, respectively.

TPC2 inhibition by YM201636 is sensitive to mutations at and near the cytosolic side pore entrance

To identify the YM201636 binding sites along the channel pore, we performed an Ala scanning analysis among the channel pore residues (Fig. 4a). Given its large size, the YM201636 molecule may interact with residues inside the pore and also those near the pore entrance. Therefore, we also examined the mutational effect of His699 residue, which is located immediately at the pore entrance on the cytosolic side (Fig. 4a). Compared to the L690A/L694A double mutation, the Ala-substitution of residues inside the channel pore by mutations N305A, T308A, S682A, V686A, and N687A showed less effects on TPC2 inhibition by 1 µM YM201636 (Fig. 4e). Major reductions in sensitivity to YM201636 were observed with mutations of the Y312 and H699 residues (Fig. 4e–i). Y312 is located immediately below the L690/L694 pore-gate while H699 is positioned near the cytosolic side of the pore entrance (Fig. 4a). The Y312A mutation significantly increased the IC50 for TPC2 inhibition by YM201636, by more than 4-fold (IC50 = 0.67 µM) (Fig. 4f, i). The H699A mutation drastically reduced the channel’s sensitivity to YM201636, as indicated by a more than 20-fold increase in the IC50 (IC50 = 4.33 µM) compared to that of the wild-type channel (Fig. 4g, i). The double mutation Y312A/H699A resulted in a much greater loss of the channel’s sensitivity to YM201636, with an IC50 beyond the highest tested concentration (21 µM) (Fig. 4h, i), i.e., the mutation resulted in an increase of IC50 by more than 100-fold compared to that of the wild-type channel. These results indicate that the cytosolic-side pore-gate forming residues L690, L694, and Y312, together with the H699 residue located immediately outside of the pore, determines YM201636’s inhibitory effect on TPC2, likely by forming the inhibitor’s binding sites.

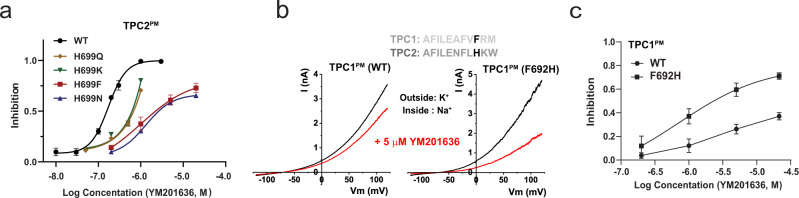

His699 underlies much greater sensitivity to YM201636 in TPC2 than TPC1

To further analyze the impact of the mutations of H699 on TPC2’s sensitivity to YM201636, we generated more mutations at this site. Similar to the effects of the H699A mutation, the H699F and H699N mutations greatly reduced inhibition of the channel by YM201636 with estimated IC50 values of ~2.2 and ~2.68 µM, respectively (Fig. 5a). The H699Q and H699K mutations also reduced TPC2’s sensitivity to YM201636 but to a much lesser extent (IC50 values of ~0.7 µM and ~0.6 µM, respectively) than H699A, H699F, and H699N mutations did (Fig. 5a). These suggest that substitution of histidine by a larger polar (Gln as compared to Asn) or positively charged residue at this position helps alleviate the loss in the channel’s sensitivity to YM201636.

Fig. 5. The residue H699 underlies the increased sensitivity of TPC2 to YM201636 than TPC1.

a The effect of mutations at H699 on the dose-responses (n = 5–7 for each data point) of the YM201636’s inhibition of the TPC2PM channel. b The effect of YM201636 on WT and mutant H692F of human TPC1PM channel. The sequence alignment of human TPC1 and TPC2 at the mutated region was showed on top. Phe692 in TPC1 and His699 in TPC2 channel were indicated in black. c Dose-responses (n = 3–8 for each data point) of YM201636’s inhibitory effect on WT and H692F mutant channels of human TPC1PM. All recordings were done in inside-out configuration using asymmetric Na+ (outside)/K+ (inside) (a) or Na+ (inside)/K+ (outside) (b, c) recording solutions. The averaged data are presented as mean value ± SEM.

Interestingly, the TPC1 channel harbors a Phe (F692) at the equivalent TPC2-H699 position (Fig. 5b). By patch-clamp recording of the plasma membrane-targeted TPC1 L11A/I12A mutant (TPC1PM) channel9,18, we observed that TPC1, as compared to TPC2, was much less sensitive to YM201636 (IC50 > 20 µM) (Fig. 5b, c). Upon substitution with a histidine at this position by the F692H mutation, the TPC1 channel’s sensitivity to YM201636 was greatly enhanced with a resulting IC50 of ~2.3 µM (Fig. 5b, c). Therefore, H699 is a key determinant for TPC2 channel’s inhibition by YM201636, whose substitution with a Phe in the TPC1 channel partially accounts for the vastly decreased sensitivity to YM201636.

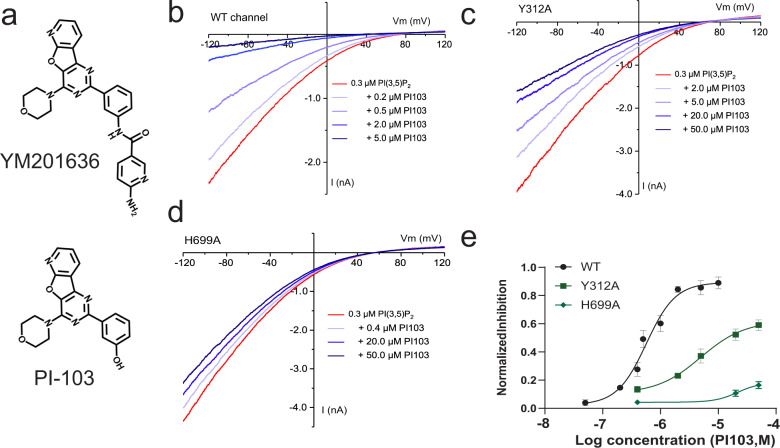

PI-103, a YM201636 analog, also acts as a TPC2 pore blocker

PI-103, a known PI3K and mTOR inhibitor, has nearly the same chemical structure as YM201636 but without a 6-amino-nicotinamide group (Fig. 6a). We observed that PI-103 also directly inhibited the PI(3,5)P2-induced TPC2 channel Na+ current (Fig. 6b) in a concentration-dependent manner with an IC50 of 0.64 μM (Fig. 6e), which is 4-fold higher than that of YM201636, suggesting that the 6-amino-nicotinamide group has a role in enhancing the potency of YM201636’s TPC2 blockade effect. Similar to that observed with YM201636, the Y312A mutation in TPC2 also resulted in reduced inhibition of the channel by PI-103 with an elevated IC50 of 13.9 µM (Fig. 6c, e). The H699A mutation largely abolished the channel’s blockade by PI-103 (Fig. 6d, e). Therefore, PI-103 acts similarly to YM201636 by functioning as a potent TPC2 channel blocker.

Fig. 6. Inhibition of the human TPC2 channel by PI-103.

a The chemical structures of YM201636 and PI-103. b–d The effect of PI-103 on WT (b) and Y312A (c) and H699A (d) mutants of the human TPC2PM channel. The channel was activated by 0.3 μM PI(3,5)P2. e Dose-responses (n = 5–7 for each data point) of the PI-103’s inhibitory effect on WT and Y312A and H699A mutants of the human TPC2 channel, as shown in (b–d). All recordings were done in inside-out configuration using asymmetric Na+ (outside)/K+ (inside) recording solutions. The averaged data are presented as mean value ± SEM.

Molecular docking and dynamic simulation analyses of YM201636’s bindings along the channel pore

We initially performed a virtual molecular docking analysis via the AutoDock Vina program44 using the reported human TPC2 Cryo-EM structures10 directly. With the whole proteins included in the grid space for docking and a cut-off affinity of −8.5 kcal/mol, YM201636 molecule docked inside the channel pore was observed in 13 out of 34 poses for the PI(3,5)P2-bound open-state structure (PBD ID:6NQ0), 3 out of 22 poses for the PI(3,5)P2-bound closed-state structure (PBD ID:6NQ2), and none out of 7 for apo/closed-state structure (PBD ID:6NQ1). This result is consistent with our finding of the requirement of the channel’s open-state for channel inhibition by YM201636. Thus, we focused on docking analysis of YM201636’s bindings on the PI(3,5)P2-bound open-state structure.

Most molecular docking programs including AutoDock Vina treat the receptor proteins as rigid bodies to be computation efficient but at a cost of limitation in accuracy because of the dynamic nature of protein-ligand binding involving the protein’s local conformational changes in binding. To better identify the inhibitors’ binding sites in the TPC2 open structure, we first performed a molecular dynamic simulation of the PI(3,5)P2-bound human TPC2 open-state structure (PDB: 6NQ0)10. After simulation for 200 ns, we clustered the trajectory structural frames from the last 50 ns of the simulation and generated 76 representative snapshots of the simulated dynamic structures. With them, we performed virtual molecular docking analyses individually via the AutoDock Vina program and allowed the output of the top 20 poses based on calculated affinity. Among the ~1500 generated poses, we chose the 30 poses with the highest affinity for visual examination and further analysis. If the whole region of the channel pore was included in the grid space for docking, the top 30 poses had an average affinity of −11.05 kcal/mol, and all YM201636 molecules were docked at the bundle-crossing pore-gate region flanked by the Y312, R316, L690, L694, and E695 residues from the two identical subunits (Fig. 7a). No preference in the orientation of the YM201636 molecule was observed, as the 6-amino-nicotinamide group pointed in and out of the pore in about equally often. PI-103 was similarly docked at a similar region, at which the top 30 poses had an average affinity of −10.11 kcal/mol, which was slightly lower in affinity than that of YM201636 and consistent with the increased IC50 of PI-103 compared to that of YM201636. However, the interactions of YM201636 and PI-103 with H699 were very limited or absent in their top 30 energetically favorable poses as the inhibitors were well-docked inside the pore whereas H699 is located outside of the pore.

Fig. 7. Molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation analyses of the YM201636’s bindings in human TPC2.

a, b The top 30 poses of YM201636 docked in the whole channel pore region (a) or the pore entrance region (b) of the PI(3,5)P2-bound open-state channels. The YM201636’s carbon atom in (a) is shown in green and yellow, respectively, for the poses with their 6-amino-nicotinamide group pointed in and out of the pore. c The bottom views of the four representative poses (upper panels) and the side-views of the superimposed YM201636’s conformations (50 frames; 2 ns/frame) during the 100 ns simulation (bottom). For clarity, only a representative protein structure from a single frame is shown in (a–c). d Plots of the mean contact scores and total contact times for residues interacting with YM201636. The data were obtained by analyses of their interactions in the trajectories of the four 100 ns molecular dynamic simulations with the Pycontact program. The scores and time were combined from the two identical residues of the two homodimeric subunits.

Given the importance of the H699 residue in TPCs’ sensitivity to the inhibitors, we hypothesized that H699 potentiates the channel blockade by interactions with the inhibitors around the pore entrance, allowing the inhibitor to block ion conductance directly at the pore entrance and/or alternatively the H699 to serve as initial docking sites to guide and facilitate the inhibitors to move toward the more favorable binding sites inside the pore. To identify the inhibitors’ binding poses around the pore entrance, we limited the docking grid space to the pore entrance region. With this docking space restriction, we were able to observe YM201636’s bindings at the pore entrance region below the pore-gate with a suboptimal average affinity of −9.27 kcal/mol for the top 30 poses (Fig. 7b). Among most (n = 26) of these 30 top poses, the imidazole ring of H699 interacted closely (within 4 Å excluding hydrogen atoms) with YM201636. The interactions with H699 appeared flexible, involving nearly all the different parts of YM201636 in different poses, suggesting that these interactions are likely dynamic. Similarly, PI-103 was also observed to bind at the pore entrance, although the averaged affinity for the top 30 poses was reduced to −8.19 kcal/mol.

We selected 4 representative poses of YM201636 in complex with TPC2 (Fig. 7c) for further analysis by molecular dynamic simulations for 100 ns. For the first three simulations, the initial poses appeared to be only relative stable for only a short period, e.g., ~20 ns, and then became more mobile and adopted binding modes different from the initial one. However, no full escape from the pore entrance was observed during these 100 ns simulations. For the fourth simulation, the YM201636’s interactions with the channel pore became enhanced in that the inhibitor moved slightly inward the pore and kept the pore entrance blocked during the 100 ns simulation as indicated by some interactions with the pore gate region residues L694 and A309 (Fig. 7c). With the PyContact program45, we performed a systematic analysis of the interactions between YM201636 and protein residues in the four 100 ns simulation trajectories and found that YM201636 remained strongly interacting with H699 most time (Fig. 7d), including H-bond interaction (20% in average). According to the mean contact score and total contact time, YM201636 interacted predominantly with R316, H699, and E695, secondarily with L698 and M320, and marginally with Y312, S313, and N696 (Fig. 7d). The results of molecular dynamic simulation on YM201636’s bindings at and near the pore entrance indicate that the inhibitor dynamically interacts with the residues around the pore entrance and can move inside the pore for more sustained channel blockade. Similar to H699, we expect that R316 and E695 also play an important role in TPC2 inhibition by YM201636. The equivalent residues of R316 and E695 in X. tropicalis TPC3 were found to be important for the channel gating via electrostatic interactions and their mutations could result in non-functional channels46. Because both R316A and E695A mutations in human TPC2 produced non-functional channels, we pursued no further mutational analysis on them.

Discussion

In this study, we identified YM201636 and its analog PI-103 to be potent human TPC2 channel blockers. YM201636 and PI-103 act similarly on TPC2 as their inhibitory effects on the channels are similarly affected by pore mutations. Importantly, as pore blockers, YM201636 and PI-103 can block the channels in an agonist-independent manner as YM201636 inhibited NAADP-evoked Ca2+ elevation, and both NAADP and PI(3,5)P2-activated TPC2 currents, and mutation-induced constitutively open TPC2 channels. Because of their submicromolar IC50 values, we considered YM201636 and PI-103 the most potent TPC2-selective antagonists identified thus far. YM201636 and PI-103 are TPC2 selective, as they are much less effective on TPC1 largely because of the His ↔ Phe switch near the cytosolic-side pore entrance (H699 on TPC2 vs. F692 on TPC1). The His ↔ Phe switch between TPC2 and TPC1 is a conserved feature in most animals except in some species, such as D. rerio and S. purpuratus whose TPC2 has a Tyr and Thr at this position, respectively.

We explored the mechanism of TPC2 inhibition by YM201636 and PI-103. First, we found YM201636 acts only when the channel is in an open state, i.e., pretreatment in the closed state has no effect. However, its inhibitory effect is independent of the mechanisms of channel activation, consistent with the property of an open-channel pore blocker. Our mutational analyses showed the importance of the L690, L694, Y312, and H699 residues located at or near the cytosolic end of the channel pore on TPC2 inhibition by YM201636 and PI-103. The role of Y312 can be easily understood as it sits at the very cytosolic end of the channel pore and its side-chain forms the port to the channel pore. Similarly, the L690A/L694A double mutation, which caused the channel to constitutively open, alters the channel pore structure and thus affects the inhibitors’ potency. However, structural perturbation of the H699 residue, which sits immediately outside of the pore, produced the largest impact on the TPC inhibition by YM201636 and PI-103. Its substitution with a Phe in human TPC1 also largely accounts for the greatly reduced sensitivity to the inhibitor. The role of H699 in TPC2 inhibition by YM201636 appears to be indispensable as mutations to other amino acids, regardless of size, polarity, or charge, all resulted in a loss of the channel’s sensitivity to the inhibitor to some extent. The histidine residue plays a unique role in protein structure and function. Its imidazole side chain gives rise to its unique aromaticity and acid/base properties at a physiologic pH. YM201636 and PI-103 are chemicals of multiple rings with both aromatic and some polar properties. H699 could interact with YM201636 and PI-103 via both Van der Waals and hydrogen bond interactions including the π-π stacking, cation-π (if histidine is protonated), and hydrogen-π interactions47. Our molecular dynamic simulation analysis suggests that H699 can interact with YM201636 and PI-103 and contribute to the inhibitors’ initial docking around the pore entrance. Overall, our data favor the possibility that YM201636 binding and blockade mainly occur at the cytosolic end of the pore as mutations deep in the pore had much less effect, and the H699 residue, which is immediately outside the pore, plays a key role in inhibition by interactions with the inhibitors around the pore entrance, allowing the inhibitor to block ion conductance directly at the pore entrance and/or alternatively serve as initial docking sites to facilitate the inhibitors to bind inside the pore. The slower process of YM201636’s wash-off than its wash-on agrees with the notion that the inhibitor initially binds and blocks the channel at or near the pore entrance and then moves more inside the pore for more sustained channel blockade.

Both YM201636 and PI-103 have been widely used in research to target other proteins. Our studies thus identify an important protein target of these two drugs. This also raises caution in interpretation of the potential mechanisms underlying the pharmacological effects of these two drugs, as the blockade of TPC2 could result in a broad range of cellular, physiological, and pathological effects as well. For example, PI-103 has some anti-tumor activity48,49, and TPC2 is also considered to be implicated in cancer20. YM201636 has anti-viral activity32,40, and TPC2 also matters for virus entry30,32. YM201636 is mainly used in research to target PIKfyve and block PI(3,5)P2 production. Although TPC2 is an effector of PI(3,5)P2 signaling, it can also be activated by other mechanisms, e.g., by NAADP via Lsm12 for TPC-mediated Ca2+ mobilization18. Therefore, direct blockade of TPC2 by YM201636 can have a more profound effect than that caused by a reduction in PI(3,5)P2 synthesis via inhibition of PIKfyve activity. YM201636 and its derivative-based therapeutics could be an effective strategy to simultaneously target two virus entry-related proteins, PIKfyve and TPC2.

Given their broad physiological and pathological roles, TPCs are emerging as important therapeutic targets for many diseases including COVID-19. Currently, there is an unmet need to develop specific and potent antagonists targeting TPCs. Our identification of YM201636 and PI-103 as potent TPC2-selective (over TPC1) blockers and revelation of the underlying mechanism provide effective pharmacological tools to inhibit TPC2 currents and offers templates for rational design of specific and potent inhibitors of TPC2.

Methods

Cell culture, plasmids, and transfection

HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin, and streptomycin in a 5% CO2 incubator. Similar to our recent report18, recombinant cDNA constructs of human TPC1 (GenBank: AY083666.1) and human TPC2 (GenBank: BC063008.1) with FLAG and V5 epitopes on their C-termini were constructed with pCDNA6 vector (Invitrogen). To facilitate identification of transfected cells, an IRES-containing bicistronic vector, pCDNA6-TPC2-V5-IRES-AcGFP18, was used in the electrophysiological experiments. Mutations were made with QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies). Cells were transiently transfected with plasmids with transfection reagent of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) or polyethylenimine “Max” (PEI Max from Polysciences) and subjected to experiments within 16–48 h after transfection. For the cell health of the mutant L690A/L694A after transfection, 2.0 µM YM201636 was added into the complete serum medium to block TPC2. For human TPC1 channels, pEGFP-C1 was cotransfected at the same time to identify transfected cells for patch clamp recording. Cells were treated with 1% trypsin 4–6 h after transfection and seeded on polylysine-treated glass coverslips soaked in an incubator until recording.

Imaging analysis of NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release

Ca2+ imaging analysis of NAADP-evoked Ca2+ elevation was performed as we recently described18. Briefly, cells were co-transfected with cDNA constructs of human TPC2 and the Ca2+ reporter GCaMP6f, and the transfected cells were identified by GCaMP6f fluorescence. Fluorescence was monitored with an Axio Observer A1 microscope equipped with an AxioCam MRm digital camera and ZEN Blue 2 software containing a physiology module (Carl Zeiss) at a sampling frequency of 2 Hz. Cell injection was performed with a FemtoJet microinjector (Eppendorf). The pipette solution contained 110 mM KCl, 10 mM NaCl, and 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.2) supplemented with Dextran (10,000 MW)-Texas Red (0.3 mg/ml) and NAADP (100 nM) or vehicle. When needed, 10 µM YM201626 or apilimod at was added to the pipette solution. The bath was Hank’s balanced salt solution, which contained 137 mM NaCl, 5.4 mM KCl, 0.25 mM Na2HPO4, 0.44 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM MgSO4, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM glucose, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4). To minimize interference by contaminated Ca2+, the pipette solution was always treated with Chelex 100 resin (#C709, Sigma-Aldrich) immediately before use. Microinjection (0.5 s at 150 hPa) was made ~30 s after pipette tip insertion into cells. Only cells that showed no response to mechanical puncture, i.e., no change in GCaMP6f fluorescence for ~30 s, were chosen for pipette solution injection. Successful injection was verified by fluorescence of the co-injected Texas Red. Elevation in intracellular Ca2+ concentration was reported by a change in fluorescence intensity measured as ΔF/F0, calculated from NAADP microinjection-induced maximal changes in fluorescence (ΔF at the peak) divided by the fluorescence immediately before microinjection (F0).

Electrophysiology

For inside-out and whole cell patch-clamp recording, HEK293 cells were transiently transfected with plasma membrane–targeted TPC2L11A/L12A (TPC2PM) or TPC1L11A/I12A (TPC1PM) mutant channels using the transfection reagent of PEI MAX as we did before18. After 24 h of transfection, human TPC1PM or TPC2PM channel currents were acquired at room temperature using an EPC-10 amplifier and PatchMaster software (HEKA) or a MultiClamp 700B amplifier and pCLAMP software (Axon Instruments). For most inside-out recording of excised plasma membrane patches, the bath solution contained 145 mM KMeSO3, 5 mM NaCl, and 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.35), and the pipette solution contained 145 mM NaMeSO3, 5 mM NaCl, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.35). For the constitutively open L690A/L694A mutant TPC2 or human TPC1 channel, the solutions were switched, i.e., the K+-based solution was used as the pipette solution, and the Na+-based solution was used in the bath instead. To measure the voltage dependence of TPC2 inhibition by YM201636, the same Na+-based solution was used on both sides (pipette and bath). Patch pipettes were polished with a resistance of 2–3 MΩ for recording. Similarly, for whole-cell recording to allow inhibitor application on the extracellular side, the K+-based solution was used as the pipette solution, and the Na+-based solution was used in the bath. The TPC2 and TPC1 channel currents were elicited by perfusion of PtdIns(3,5)P2 diC8 (#P-3058, Echelon) on the intracellular side in inside-out recording or by perfusion of TPC2-A1-N (MedChemExpress) on the extracellular side in whole-cell recording with a voltage ramp protocol of −120 mV to +120 mV over 200 ms for every 2 s. YM201636 was applied together with the activator by perfusion.

Whole cell patch-clamp recording of the NAADP (microinjection)-induced TPC2PM currents was performed as we reported18. Bath solution contained 145 mM NaMeSO3, 5 mM NaCl, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). Pipette electrodes (3–5 MΩ) were filled with 145 mM KMeSO3, 5 mM KCl, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2). The cells were visualized under an infrared differential interference contrast optics microscope (Zeiss). Currents were recorded by voltage ramps from −120 to +120 mV over 400 ms for every 2 s with a holding potential of 0 mV. After a whole cell recording configuration was achieved, an injection pipette was inserted into the cell and the baseline of the whole cell current was recorded. Microinjection of NAADP was performed as above in imaging analysis of NAADP-evoked Ca2+ release. The NAADP-induced currents were obtained by subtraction of the baseline from NAADP injection-induced currents. YM201636 and apilimod at 1 µM were added in the bath solution for ~10 min before recording.

Whole lysosome patch-clamp recording of PI(3,5)P2-activated TPC2 activation was performed as previously reported by others43,50 and us18. Cells were treated with vacuolin-1 (1 µM) overnight to enlarge endolysosomes. Patch pipettes for recording were polished and had a resistance of 5–8 MΩ. The cytoplasmic solution contained 145 mM KMeSO3, 4 mM NaCl 4, 0.39 mM CaCl2, 1 mM EGTA, and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) (pH was adjusted with KOH). The luminal solution contained 140 mM NaMeSO3, 5 mM KMeSO3, 2 mM Ca(MeSO3)2, 1 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES and 10 mM MES (pH 4.6) (pH was adjusted with methanesulfonic (MeSO3) acid). YM201636 was applied together with PI(3,5)P2 on the cytosolic side by perfusion.

All reagents were purchased commercially: PI-103 (#1728; Biovision), YM201636 (#sc-204193; Santa Cruz Biotechnology), apilimod (#sc-480051; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Dose curves were fitted by the Hill logistic equation. τon and τoff were acquired from singe exponential fitting.

Molecular docking analysis and molecular dynamic simulation

Molecular docking analyses of the bindings of the inhibitor YM201636 on TPC2 channel structures were performed using AutoDock Vina program44 according to the developers’ instructions with Cryo-EM structures (PDB IDs: 6NQ0, 6NQ2, and 6NQ1) of human TPC210 either directly or after molecular dynamic simulation in the closed state in the presence of and the absence of PI(3,5)P2 (PDB ID: 6NQ2 and 6NQ1)10. For molecular dynamic simulation, the Cryo-EM structure of human TPC2 in the open state in complex with PI(3,5)P2 (PDB ID: 6NQ0) was used. The missed flexible C-terminus (residues 702-752) in the original structure was added by modeling with the GalaxyFill algorithm51 integrated in the CHARMM-GUI webserver52. The protein/lipid/solvent systems and input files for molecular dynamic simulation were generated with the CHARMM-GUI webserver52. The structural model was embedded in a lipid bilayer of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC) within a water box containing 0.15 M KCl in which the protein charges were neutralized with K+ or Cl− ions. The molecular dynamic simulation was carried out with Gromacs 2021 (10.5281/zenodo.5053220)53 and the CHARMM36m force-field54 with the WYF parameter for cation-pi interactions55. The system was energy-minimized and then equilibrated in 6 steps using default input scripts for Gromacs generated by the CHARMM-GUI webserver. After the equilibration, the systems were simulated for 200 ns with a 2 fs time step. The Nose-Hoover thermostat and a Parrinello-Rahman semi-isotropic pressure control were used to keep the temperature at 303.15 K and the pressure at 1 bar, respectively. A 12-Å cut-off was used to calculate the short-range electrostatic interactions, and the Particle Mesh Ewald summation method was employed to account for the long-range electrostatic interactions.

Statistics and reproducibility

The data were processed and plotted with Igor Pro (v5), GraphPad Prism (v9), or OriginLab (v2015 or 2017). All statistical values are performed as means ± standard errors of the mean of n repeats of the experiments. Unpaired Student’s t-test (two-tailed) was used to calculate p values. Unless indicated, all measurements or repeats were taken with distinct samples or cells. Independent experiments with similar results related to representative results were done ≥3 times.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We thank Ashli R. Villarreal and Sarah Bronson at Research Medical Library of MD Anderson Cancer Center for editing this article. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants GM130814 (J.Y.).

Author contributions

C.D. performed most electrophysiological experiments. X.G. performed calcium imaging experiment and patch-clamp recording of whole lysosomal and whole cell (NAADP-induced) TPC currents. J.Y. performed molecular docking and molecular dynamic simulation analyses. C.D., X.G., and J.Y. designed experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Biology thanks Antony Galione, Huaiyu Yang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editor: Gene Chong. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

All relevant data are contained within this article. Source data are found in Supplementary Data. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42003-022-03701-5.

References

- 1.Calcraft PJ, et al. NAADP mobilizes calcium from acidic organelles through two-pore channels. Nature. 2009;459:596–600. doi: 10.1038/nature08030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zong X, et al. The two-pore channel TPCN2 mediates NAADP-dependent Ca2+-release from lysosomal stores. Pflug. Arch. 2009;458:891–899. doi: 10.1007/s00424-009-0690-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang X, et al. TPC proteins are phosphoinositide- activated sodium-selective ion channels in endosomes and lysosomes. Cell. 2012;151:372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo J, Zeng W, Jiang Y. Tuning the ion selectivity of two-pore channels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:1009–1014. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1616191114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jha A, Ahuja M, Patel S, Brailoiu E, Muallem S. Convergent regulation of the lysosomal two-pore channel-2 by Mg2+, NAADP, PI(3,5)P2 and multiple protein kinases. EMBO J. 2014;33:501–511. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boccaccio A, et al. The phosphoinositide PI(3,5)P2 mediates activation of mammalian but not plant TPC proteins: functional expression of endolysosomal channels in yeast and plant cells. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2014;71:4275–4283. doi: 10.1007/s00018-014-1623-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cang C, et al. mTOR regulates lysosomal ATP-sensitive two-pore Na+ channels to adapt to metabolic state. Cell. 2013;152:778–790. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lagostena L, Festa M, Pusch M, Carpaneto A. The human two-pore channel 1 is modulated by cytosolic and luminal calcium. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43900. doi: 10.1038/srep43900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.She J, et al. Structural insights into the voltage and phospholipid activation of the mammalian TPC1 channel. Nature. 2018;556:130–134. doi: 10.1038/nature26139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.She, J. et al. Structural mechanisms of phospholipid activation of the human TPC2 channel. Elife8, 10.7554/eLife.45222 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Ruas M, et al. Purified TPC isoforms form NAADP receptors with distinct roles for Ca2+ signaling and endolysosomal trafficking. Curr. Biol. 2010;20:703–709. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brailoiu E, et al. Essential requirement for two-pore channel 1 in NAADP-mediated calcium signaling. J. Cell Biol. 2009;186:201–209. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200904073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brailoiu E, et al. An NAADP-gated two-pore channel targeted to the plasma membrane uncouples triggering from amplifying Ca2+ signals. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:38511–38516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi S, et al. Transient receptor potential mucolipin 1 (TRPML1) and two-pore channels are functionally independent organellar ion channels. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:22934–22942. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.210930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira GJ, et al. Nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP) regulates autophagy in cultured astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:27875–27881. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C110.216580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tugba Durlu-Kandilci N, et al. TPC2 proteins mediate nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NAADP)- and agonist-evoked contractions of smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:24925–24932. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.129833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruas M, et al. Expression of Ca2+-permeable two-pore channels rescues NAADP signalling in TPC-deficient cells. EMBO J. 2015;34:1743–1758. doi: 10.15252/embj.201490009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J, Guan X, Shah K, Yan J. Lsm12 is an NAADP receptor and a two-pore channel regulatory protein required for calcium mobilization from acidic organelles. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4739. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24735-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Garcia-Rua V, et al. Endolysosomal two-pore channels regulate autophagy in cardiomyocytes. J. Physiol. 2016;594:3061–3077. doi: 10.1113/JP271332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen ON, et al. Two-Pore Channel Function Is Crucial for the Migration of Invasive Cancer Cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77:1427–1438. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muller, M. et al. Gene editing and synthetically accessible inhibitors reveal role for TPC2 in HCC cell proliferation and tumor growth. Cell Chem. Biol.10.1016/j.chembiol.2021.01.023 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Webb, S. E., Kelu, J. J. & Miller, A. L. Role of two-pore channels in embryonic development and cellular differentiation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect Biol.12, 10.1101/cshperspect.a035170 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Arndt L, et al. NAADP and the two-pore channel protein 1 participate in the acrosome reaction in mammalian spermatozoa. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2014;25:948–964. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e13-09-0523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin-Moshier Y, et al. The Two-pore channel (TPC) interactome unmasks isoform-specific roles for TPCs in endolysosomal morphology and cell pigmentation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:13087–13092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407004111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao YK, et al. TPC2 polymorphisms associated with a hair pigmentation phenotype in humans result in gain of channel function by independent mechanisms. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:E8595–E8602. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705739114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ambrosio AL, Boyle JA, Aradi AE, Christian KA, Di Pietro SM. TPC2 controls pigmentation by regulating melanosome pH and size. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:5622–5627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1600108113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rivero-Rios P, Fernandez B, Madero-Perez J, Lozano MR, Hilfiker S. Two-pore channels and parkinson’s disease: where’s the link? Messenger (Los Angel) 2016;5:67–75. doi: 10.1166/msr.2016.1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruas M, Galione A, Parrington J. Two-pore channels: lessons from mutant mouse models. Messenger (Los Angel) 2015;4:4–22. doi: 10.1166/msr.2015.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel S. Function and dysfunction of two-pore channels. Sci. Signal. 2015;8:re7. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.aab3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sakurai Y, et al. Ebola virus. Two-pore channels control Ebola virus host cell entry and are drug targets for disease treatment. Science. 2015;347:995–998. doi: 10.1126/science.1258758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunaratne GS, Yang Y, Li F, Walseth TF, Marchant JS. NAADP-dependent Ca2+ signaling regulates Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus pseudovirus translocation through the endolysosomal system. Cell Calcium. 2018;75:30–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2018.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ou X, et al. Characterization of spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 on virus entry and its immune cross-reactivity with SARS-CoV. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:1620. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-15562-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naylor E, et al. Identification of a chemical probe for NAADP by virtual screening. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009;5:220–226. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kintzer AF, Stroud RM. Structure, inhibition and regulation of two-pore channel TPC1 from Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature. 2016;531:258–262. doi: 10.1038/nature17194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pafumi I, et al. Naringenin impairs two-pore channel 2 activity and inhibits VEGF-induced angiogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:5121. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04974-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Netcharoensirisuk P, et al. Flavonoids increase melanin production and reduce proliferation, migration and invasion of melanoma cells by blocking endolysosomal/melanosomal TPC2. Sci. Rep. 2021;11:8515. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88196-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rahman T, et al. Two-pore channels provide insight into the evolution of voltage-gated Ca2+ and Na+ channels. Sci. Signal. 2014;7:ra109. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sbrissa D, et al. Core protein machinery for mammalian phosphatidylinositol 3,5-bisphosphate synthesis and turnover that regulates the progression of endosomal transport. Novel Sac phosphatase joins the ArPIKfyve-PIKfyve complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:23878–23891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lees JA, Li P, Kumar N, Weisman LS, Reinisch KM. Insights into Lysosomal PI(3,5)P2 Homeostasis from a Structural-Biochemical Analysis of the PIKfyve Lipid Kinase Complex. Mol. Cell. 2020;80:736–743. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kang YL, et al. Inhibition of PIKfyve kinase prevents infection by Zaire ebolavirus and SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:20803–20813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2007837117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sbrissa D, Ikonomov OC, Filios C, Delvecchio K, Shisheva A. Functional dissociation between PIKfyve-synthesized PtdIns5P and PtdIns(3,5)P2 by means of the PIKfyve inhibitor YM201636. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2012;303:C436–C446. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00105.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Raynaud FI, et al. Pharmacologic characterization of a potent inhibitor of class I phosphatidylinositide 3-kinases. Cancer Res. 2007;67:5840–5850. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerndt, S. et al. Agonist-mediated switching of ion selectivity in TPC2 differentially promotes lysosomal function. Elife9, 10.7554/eLife.54712 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 44.Trott O, Olson AJ. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput Chem. 2010;31:455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Scheurer M, et al. PyContact: rapid, customizable, and visual analysis of noncovalent interactions in MD simulations. Biophys. J. 2018;114:577–583. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimomura T, Kubo Y. Phosphoinositides modulate the voltage dependence of two-pore channel 3. J. Gen. Physiol. 2019;151:986–1006. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201812285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liao SM, Du QS, Meng JZ, Pang ZW, Huang RB. The multiple roles of histidine in protein interactions. Chem. Cent. J. 2013;7:44. doi: 10.1186/1752-153X-7-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gedaly R, et al. PI-103 and sorafenib inhibit hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by blocking Ras/Raf/MAPK and PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathways. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4951–4958. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Donev IS, et al. Transient PI3K inhibition induces apoptosis and overcomes HGF-mediated resistance to EGFR-TKIs in EGFR mutant lung cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011;17:2260–2269. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ogunbayo, O. A. et al. mTORC1 controls lysosomal Ca2+ release through the two-pore channel TPC2. Sci. Signal11, 10.1126/scisignal.aao5775 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Coutsias EA, Seok C, Jacobson MP, Dill KA. A kinematic view of loop closure. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:510–528. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu EL, et al. CHARMM-GUI Membrane Builder toward realistic biological membrane simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2014;35:1997–2004. doi: 10.1002/jcc.23702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Van Der Spoel D, et al. GROMACS: fast, flexible, and free. J. Comput. Chem. 2005;26:1701–1718. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lee J, et al. CHARMM-GUI input Generator for NAMD, GROMACS, AMBER, OpenMM, and CHARMM/OpenMM simulations using the CHARMM36 additive force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2016;12:405–413. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Khan HM, MacKerell AD, Jr, Reuter N. Cation-pi interactions between methylated ammonium groups and tryptophan in the CHARMM36 additive force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2019;15:7–12. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.8b00839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are contained within this article. Source data are found in Supplementary Data. All other data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.