Abstract

Background and objective:

Systematically supporting caregiver-assisted medication management through IT interventions is a critical area of need toward improving outcomes for people living with ADRD and their caregivers, but a significant gap exists in the evidence base from which IT interventions to support caregivers’ medication tasks can be built. User-centered design can address the user needs evidence gap and provide a scientific mechanism for developing IT interventions that meet caregivers’ needs. The present study employs the three phases of user-centered design to address the first two stages of the NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development.

Methods:

We will conduct a three-phase study employing user-centered design techniques across three aims: Aim 1) assess the needs of ADRD caregivers who manage medications for people with ADRD (Stage 0); Aim 2) co-design a prototype IT intervention to support caregiver-assisted medication management collaboratively with ADRD caregivers (Stage IA); and Aim 3) feasibility test the prototype IT intervention with ADRD caregivers (Stage IB).

Discussion:

Our user-centered design protocol provides a template for integrating the three phases of user-centered design to address the first two stages of the NIH Stage Model that can be used broadly by researchers who are developing IT interventions for ADRD caregivers.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, Mobile app, mHealth, Caregivers, Dementia caregiving, Medication management, User-centered design, Human-centered design

1. Introduction

A majority of the nearly 6 million people living with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) in the US rely upon informal (family and friend) caregivers to help manage their medications.1–3 Caregiver-assisted medication management has been associated with the potential to improve medication management outcomes for people with ADRD.3 However, people with ADRD often require the management of multiple simultaneous medications and complex medication regimens.4,5

Caregivers are often untrained, under-resourced, and unsupported6–8 to perform the medication tasks people living with ADRD rely upon. Studies have reported that caregiver-assisted medication management is burdensome and stressful for caregivers;9–12 can be too complex, given caregivers’ lack of information on medication management13; may produce conflict between the caregiver and person with ADRD14; and results in errors,15 nonadherence,3 and potentially inappropriate medication use in one-third of people living with ADRD.2

Systematically supporting caregiver-assisted medication management through IT interventions is a critical area of need toward improving outcomes for people living with ADRD and demonstrating the real-world utility of IT interventions to support caregiving. Devices and tools are available to support medication management such as sensors for pill bottles, pill organizers, and in-home dispensers; but caregivers report a lack of medication adherence tools designed to meet their needs.16 Although data are limited and study quality is variable, packing intervention systems including prefilled blister packs and electronic medication packaging are generally effective for improving patient adherence.17,18 Further, mobile apps designed to support medication adherence are also available, but app designs are focused on patients rather than caregivers as the end users.19 Although IT interventions are needed, a significant gap exists in the evidence base on which IT interventions to support caregivers’ medication tasks can be built.14,20–23

According to the NIH Stage Model for Behavioral Intervention Development, behavioral interventions including IT solutions must be built upon a solid empirical record.24 Although self-report studies produced evidence that caregiver-assisted medication management can be problematic for ADRD caregivers,20–23 there is insufficient evidence of the specific “user needs” that IT interventions addressing caregivers’ medication tasks should address.14,23,25,26 This precludes evidence-based interventions and risks interventions that are not user-centered, resulting in caregiver non-adoption, non-acceptance, and non-use of even the most technically advanced IT.27–29

User-centered design – “an approach to interactive systems development that aims to make systems useable and useful by focusing on the users, their needs and requirements, and by applying human factors/ergonomics, usability knowledge, and techniques”69 – is perfectly poised to address the user needs evidence gap and provide a scientific process for developing IT interventions that meet caregivers’ needs.30 Importantly, user-centered design is recognized as an approach that “enhances effectiveness and efficiency, improves human well-being, user satisfaction, accessibility and sustainability, and counteracts possible adverse effects of use on human health, safety and performance”.69

Therefore, the present study employs the three phases of user-centered design to address the first two stages of the NIH Stage Model: user needs assessment (Stage 0); participatory co-design (Stage IA); and user testing (Stage IB).

2. Methods

2.1. Conceptual framework

The study is guided by Smith et al.’s taxonomy of caregivers’ medication tasks31: 1) maintaining medication supplies (e.g., purchasing prescriptions); 2) assisting with administration (e.g., reminding to take); 3) making clinical judgements (e.g., in response to side-effects); and 4) communicating about medication tasks (e.g., to the person with ADRD and health professionals).

Specific Aim 1 (Needs Assessment): Assess the needs of ADRD caregivers who manage medications for people with ADRD.

2.2. Design

The first phase of the study is user needs assessment (NIH Stage 0), conducted for the purpose of determining the needs of caregivers who manage medications for people with ADRD. To perform the user needs assessment, we will use our virtual contextual inquiry method with N = 24 caregivers performing medication tasks for people with ADRD. User needs will be analyzed on two axes: the caregiver user “persona”32 and the caregiver “journey,”33 which will depict user need variability across user types and over time, to guide future design decisions for the IT intervention. Contextual inquiry will allow us to collect rich longitudinal observation and interview data as caregivers perform medication tasks. Contextual inquiry is a method for design researchers to observe people in their natural ‘work environment’ while they perform tasks as they normally do, coupled with interview probes unobtrusively inserted prior, during, and after observation.34,35 The purpose of contextual inquiry is to understand the details implicit in what people do, including their approaches and strategies, and where they experience challenges. The observer takes the role of apprentice, letting the observed “expert’s” behavior guide data collection. Contextual inquiry has been used previously in healthcare to develop and/or implement IT.36,37 For example, we used contextual inquiry to design a decision aid to improve older adult medication safety,38,39 design a mobile app to support families providing enteral care in the home,40 and create recommendations for IT to support dementia caregivers’ health information management.41 Over the past decade, we have adapted and refined contextual inquiry for research in patient homes, and have developed a virtual contextual inquiry protocol, which we will use in the study.38–40

2.3. Setting and sample

We will recruit N = 24 caregivers via a research registry of well-characterized subjects across all ADRD stages and their care partners. A sample size of 15–20 is considered adequate for contextual inquiry because it identifies the vast majority of user needs.34 Eligibility will be established by phone screening for: a) self-identified primary caregiver status for someone with ADRD; b) living with or near the person with ADRD; c) currently managing medications for the person with ADRD; d) able to speak and read English. Purposive sampling will be used to ensure caregivers of patients characterized as mild (N = 8), moderate (N = 8), and severe (N = 8) ADRD are enrolled, and to attempt to caregivers with diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. We will over-sample to recruit at least 1/3 participants from historically marginalized groups. We will also actively attempt to enroll at least 1/3 male participants, which we have been successful in recruiting for our preliminary work using the registry.

2.4. Procedure

Our contextual inquiry protocol has three stages: 1) enrollment interview, 2) virtual observation over a one-week period in which participants will send multiple “posts” (e.g., video clips, photographs, audio clips) each day via text message to the study team member of their medication management-related activities, and 3) post-observation interview. One team member will facilitate the three stages of the virtual contextual inquiry. Stage one and three will take place in a 1-h visit over video conferencing software. Sessions will be audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. At the end of the session, we will collect a structured demographic questionnaire assessing caregiver age, gender, race/ ethnicity, education, income, living situation, marital status, relationship to the person with ADRD, and self-reported technology ownership and use. To ensure we capture the broad range of caregivers’ medication tasks, we will use our conceptual framework of caregiver medication tasks to guide development of the semi-structured interview guide and observation probes.

2.4.1. Enrollment interview

At the enrollment visit, we will obtain consent, administer a demographic survey, provide details of the study process, set up the secure messaging uplink to the research account, and walk through the process for directly and securely uploading images or video clips. Enrollment visits will occur virtually using video conferencing software. The follow-up interview visit will then be scheduled for approximately 7 days after enrollment. We will also ask caregivers to describe their experiences performing medication tasks. Using a macro-to-micro structure we will ask caregivers to describe a typical month of medication tasks (macro-level); then a typical day of medication tasks (meso-level); finally, the specific medication tasks (micro-level). This ensures broad coverage of tasks to be studied during observations.

2.4.2. Virtual contextual inquiry

In the period between enrollment and follow-up, the participant will be instructed to create at least two multimedia “posts” per day about medication management-related activities they performed that day. This could include images, video, text, and/or audio symbolically representing an activity such as a photo of the computer used to search the internet with a typed caption (Table 1, Example 1), a direct depiction of a performed activity such as a before-after photo or video of a pill organizer being filled (Table 1, Example 2), or a narrative description of an activity such as a brief “talking head” video or voiceover documenting a trip to the doctor (Table 1, Example 3).

Table 1.

Examples of multimedia posts.

|

|

Content type

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Content modality | Symbolic representation | Direct depiction | Narrative description |

|

| |||

| Text | Example 1 | ||

| Still photo | Example 2 | ||

| Video | Example 3 | ||

| Audio | |||

The participant will be enrolled in the study at day 0 and will be prompted daily to upload self-observation content for approximately 7 days, and usually no more than 10 days. Each day of participation, the participant will receive a secure message prompt on their phone from the study team at the start and end of the day (times determined mutually between participant and research team member).

2.4.3. Post-observation interview

Follow-up interview visits will occur either in person at the participant’s home or virtually using video conferencing software. During the interview visit, the research team member will present a subset of the shared self-observation content to the participant and ask the participant to further describe through the activity that was captured, probing for detail. This session will be audio recorded for subsequent transcription.

2.5. Data analysis

To analyze data so that they will aid future design work (e.g., in Aim 2), we will employ two of the most used user-centered design methods: persona development and journey mapping. Simply put, personas depict who the users are, and journey maps shows what they do. Both analyses uncover user needs.

2.5.1. Persona development

We will apply our published persona development method32 to the data to depict distinct caregiver “types.” Personas are an archetype of a user group that is given an identity. Each persona is a composite of co-occurring factors along dimensions of interest, such as decision-making style, how much they trust clinicians, what digital tools they use, and more. Importantly, unlike marketing personas based on demographic factors (e.g., “Young Working Mother”) our personas will attempt to depict caregiver types based on their medication task needs (e.g., “Safety First,” “Needs More Info”). The goal is to identify a manageable number of personas that will guide future intervention design in a way that the variety of users’ needs are met.42 Personas will be developed through a team-based data analysis process that will iteratively narrow the data into a few distinct caregiver types. We will use affinity diagramming, which is the arrangement of sticky notes based on similarity and dissimilarity34 to create meaningful clusters.32 Each data point from our transcripts, observation notes, photographs, and demographic details will be printed onto sticky notes, and the research team will create initial groupings based on similarities and dissimilarities.43 These groupings will provide the initial persona attributes and will be iteratively refined using team-based discussion with consensus. We will use both confirming and disconfirming findings to refine personas. For each final persona we will create a profile that “gives life” to the persona and makes it easy to tell whether their needs are met or not met by given various designs (e.g., trustworthy medication safety facts for the “Safety First” persona).

2.5.2. Journey mapping

We will apply the journey mapping method to the data to depict how caregivers experience medication management over time, with whom they interact, and where breakdowns occur. A journey map is defined as “a visualization of the process that a person goes through in order to accomplish a goal,” which captures the person’s behavior, motivations, and attitudes at each stage of the journey.44 Journey mapping has been applied to several instances in healthcare,33,44 where it provides a graphic representation of the stages of a health service and its procedures, and facilitates the ability for the designer to gain deep insights into the stages of the journey (see Table 2 for common insights gained from journey maps).33 Journey maps will be developed through a team-based data analysis process. Our conceptual model of medication tasks will be used to initially frame the journey, while allowing the data to adapt the initial framing. Before beginning the journey mapping analysis, sticky notes from persona development in the previous step will be marked using a distinct color to represent each persona. This will allow us to determine when certain personas have similar or divergent journeys. Mapping will be guided by our conceptual framework of caregiver medication tasks, while also allowing for stages of the journey to be inductively identified based on caregivers’ experiences. The research team will conduct a mapping session after the first three contextual inquiry sessions in which we will create journey map sketches based on interviews and observation notes. We will elaborate upon the preliminary journey maps after each subsequent contextual inquiry session. Journey maps will be brought to subsequent contextual inquiry sessions for validation through member checking and to refine journey maps through follow-up questions. Through this process, we will attempt to iteratively depict a small number of similar journeys, balancing the expected differences between individuals with the commonalities needed to produce a single IT intervention.

Table 2.

Common insights gained from journey maps.

| Example of insights gained from journey maps | How many steps are involved? |

| What are the steps involved? | |

| Who does what steps? | |

| What are their motivations? | |

| What are their information needs? | |

| Where are they experiencing | |

| frustration? | |

| Where do errors occur? |

2.6. Rigor/trustworthiness

We will use Patton’s checklist45 for ensuring and evaluating qualitative research rigor to guide our selection and implementation of various strategies to ensure trustworthiness of qualitative analyses46: credibility (triangulation of methods and investigators; looking for negative cases), transferability (detailed description of the context), dependability (audit trail for all data collection and analyses), and confirmability (member checking with caregivers).

Specific Aim 2 (Participatory Co-design): Co-design a prototype IT intervention to support caregiver-assisted medication management collaboratively with ADRD caregivers.

2.7. Design

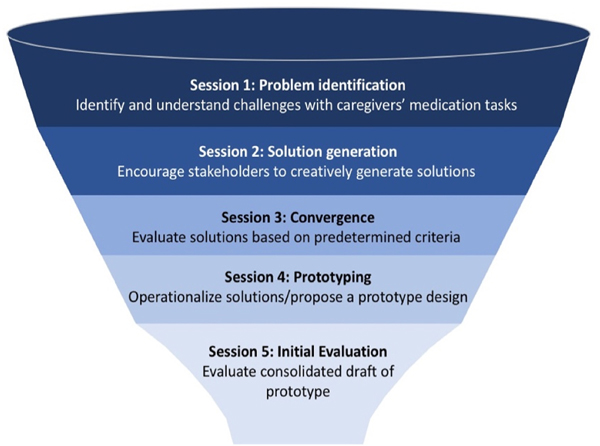

The second phase of the study is to co-design a prototype IT-based intervention to meet the needs of ADRD caregivers who manage medications for people with ADRD (NIH Stage IA). We will use our team’s published participatory design protocol to empower caregivers as equal partners in designing and evaluating IT meant for them or others like them (Fig. 1).47 We will form two researcher-facilitated design teams comprised of about 5 individuals each. During parallel co-design sessions guided by our five-stage participatory design process,47 the teams will create and critique each other’s prototype IT interventions. Design experts will then create a single consensus interactive prototype for testing in Aim 3.

Fig. 1.

5 stages of participatory design and associated session goals.

2.8. Setting and sample

We will convene two groups of co-designers, each with N = 5 individuals, which is within the standard range of participants used in participatory design research.48 The odd number of participants allows for a tie-breaking perspective in the groups. The small number of participants in two groups (i.e., rather than 10 in one group) reduces the potential for group think (i.e., by having products from one group evaluated by the other) and ensures that all participants have ample time to provide their perspective. Participants will be recruited via community partners and health systems local to the research team. Due to the small sample size and the time commitment of co-design, we will use convenience sampling but will strive for diversity of gender, race, ethnicity, and caregiving situation. Eligibility will be verified by phone for the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Aim 1, but also including former caregivers of deceased patients, to ensure co-designers have adequate experience with caregiving and medication tasks.

2.9. Procedure

The two design teams will in parallel complete a series of 5 co-design sessions across 4 months, with up to 4 weeks between each design session. We will employ our published participatory design process to collaboratively design, develop, and test the prototype IT intervention.47 The design process can be conceptualized as a funnel49 (Fig. 1) in which we start with myriad divergent ideas and then begin to work toward convergence through the sessions. Similarly, the prototype is created throughout the sessions starting with low-fidelity sketches made using paper and pencil, and progressively becomes more high-fidelity and interactive using prototyping software. We will present the teams with our conceptual framework of caregiver medication tasks to ensure the broad range of medication task types are considered. A facilitator experienced in participatory co-design will lead discussion, interpretation, and respectful debate among design team members. The facilitator will ensure progress from session to session, as well as opportunities to make continual adjustments to the design. The two design teams will conduct sessions at their respective sites, but in between sessions will swap designs and provide feedback, which will be summarized and presented by the facilitator. In session 5, the teams will evaluate their counterparts’ full-draft prototypes on a heuristic evaluation rubric47 and on the Simplified System Usability Scale (SUS).50,51 Heuristic evaluation is a standardized assessment of usability based on established design principles.52 The Simplified SUS is a validated scale modified for older and cognitively impaired adults.53 It contains 10 statements (e.g., “Learning to use the IT intervention was quick for me”) and a 5-point response scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree). Each session will last up to 90 min. Sessions will be audio recorded for subsequent analysis.

2.10. Data analysis

Analysis of formative design outputs such as sketches, use case scenarios, ratings, storyboards generated by caregivers, research team observation notes, and participant notes will occur both within and between sessions. Within sessions, the facilitator will guide participants in generating, grouping, and converging upon design solutions. Within the two-to-four week-periods between sessions, the research team will review the audio recording of the session and use the Rapid Identification of Themes from Audio-recordings (RITA) method54 to identify design specifications from the sessions. The team will combine the themes from the RITA with an analysis of any outputs from the session (e.g., sketches, ratings, etc.) and provide the results to participants at the following design session. Analysis of summative data from the heuristic evaluation and SUS in session 5 will be summarized by the research team using descriptive statistics. Results will identify specific aspects of the intervention that require design changes to improve usability that the research team will use to refine intervention design prior to Aim 3 feasibility testing.

Specific Aim 3 (User Testing): Feasibility test the prototype IT intervention with ADRD caregivers.

2.11. Design

The third phase of the study is to study intervention feasibility by testing the IT intervention prototype for usability and acceptability with 12 caregivers using the prototype in-home for 14 days (NIH Editing for consistency Stage IB). We will assess usability51,55 and acceptability via survey instruments we have modified for IT-based caregiver interventions. We will also conduct post-use interviews with caregivers to identify barriers and facilitators to usability, acceptability, and future larger-scale implementation.56–58

2.12. Setting and sample

We will recruit N = 12 caregivers who did not participate in Aims 1 or 2. A sample size of 12 is considered adequate for intervention feasibility studies.59 We will purposively sample to ensure diverse representation of gender, race and ethnicity, and stage of ADRD. Eligibility will be established by phone screening for the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as used in Aim 1.

2.13. Procedure

Once enrolled, a research team member will go to the participant’s home to obtain consent and introduce participants to the prototype IT intervention. We will also collect a structured demographic questionnaire (same measure as used in Aim 1). Participants will use the prototype in their homes for 14 days. Caregivers will be able to use their own smartphone device to use the prototype (iPhones will be provided if they need or prefer them). At the end of 14 days of use, we will assess usability and acceptability using structured, validated questionnaires as described below. We will also conduct post-use interviews with caregivers focused on identifying barriers and facilitators to usability and acceptability.56–58 Interviews will be guided by our conceptual framework of caregiver medication tasks to determine specific features of the intervention that were barriers or facilitators to ease of use or usefulness across all medication tasks. We will assess usability using our simplified, validated SUS50 (described above in Aim 2). We will assess acceptability as the mean score on a Behavioral Intention scale (e.g., “If it were up to you, to what extent would you want to use the IT intervention?”). The 4-item scale uses a 7-point response scale from 0 (not at all) to 6 (a great deal).60,61 Behavioral intention is the canonical assessment for user acceptance of technology.62 SUS and Behavioral Intention questionnaires will be researcher-administered in structured face-to-face interviews with caregivers. Responses will be entered directly into custom-built REDCap surveys on a mobile device (tablet), with paper forms available for backup.

2.14. Data analysis

2.14.1. Quantitative analysis of survey measures

We will calculate means, standard deviations, and 90% confidence intervals for the SUS and Behavioral Intention scores. We hypothesize a mean SUS score of ≥75 (out of 100, a “Good” score) and a Behavioral Intention mean score of ≥4 (out of 6).

2.14.2. Qualitative analysis of post-use interviews

Qualitative analysis of post-use interviews will complement quantitative findings by providing additional insight based on caregiver experience. We will use an inductive and deductive content analysis approach guided by usability and acceptability frameworks and allowing key constructs to emerge from the data.63 The research team will come to consensus on emergent codes and their definitions. Transcripts will then be dual coded, and agreement calculated. Qualitative analysis will be ongoing, and findings after 5 interviews will be brought to consecutive participants for member checking. Qualitative findings will be triangulated with findings from IT intervention use data and above quantitative measures.

3. Discussion

User-centered design methods have been recognized as an important approach to IT design by the US National Academies, World Health Organization,64 National Institute of Standards and Technology,65–67 and International Standards Organization (ISO).68,69 These methods represent the epitome of patient-centered methodologies70 and are foundational to designing IT-based interventions that meet people’s needs.71,72 Best practices for how to implement user-centered design within the NIH Stage Model are critical for developing IT interventions that are highly useable, useful, accessible, and acceptable. Our user-centered design protocol provides a template for integrating the three phases of user-centered design to address the first two stages of the NIH Stage Model that can be used broadly by researchers who are developing IT interventions for ADRD caregivers.

Further, our planned methods provide innovative applications of user-centered design methods. Our participatory co-design approach is likely to lead to an IT-based intervention that is uniquely responsive to caregivers’ needs by engaging caregivers as designers.73,74 In so doing, participatory co-design reaches beyond the status quo of deficit-based analyses by using a strengths-based approach where caregivers contribute to the design.48 That is, rather than being the focus of a study on what is wrong, caregivers actively contribute to design, and are therefore more likely to produce IT that is useable, useful, relevant, acceptable, and adaptable to current routines.75 In addition, by recruiting aspects of image and story-based qualitative methods such as photovoice used in social pharmacy research,76 our adapted virtual contextual inquiry approach seeks to solve a common user-centered design challenge when developing IT interventions for ADRD caregivers – gaining a deep understanding of caregivers’ activities and context while not adding burden or invading privacy. Finally, we include usability testing in our protocol, which is a critical user-centered method. To quote one researcher-regulator consensus statement on consumer health IT, “The way to ensure the truly meaningful adoption and use of [consumer health] IT is to define objective usability standards and adhere to them through established test methods.”77 Yet, usability is a neglected component of typical evaluation scorecards for consumer health IT.78 Our Aim 3 testing is therefore innovative in the present context, albeit more standard in the context of clinical IT and FDA regulated devices.79

Supporting the medication management activities performed by caregivers of people living with ADRD through IT interventions is critical to improving outcomes for both caregivers and people living with ADRD. However, the literature lacks formal, systematic analyses of the needs and current practices of caregivers managing medications for people with ADRD from which IT interventions can be built.

If successful, completion of the aims will lead to a feasible Helping the Helpers IT intervention ready for a Stage 3 hybrid efficacy/effectiveness randomized clinical trial of the intervention, powered to test changes in medication adherence and safety, with secondary outcomes of neuropsychiatric symptoms, acute care utilization, and caregiver burden. Moreover, findings from the study may be transferable to others seeking to develop interventions to support caregiver-assisted medication management. Ultimately, if successful, our IT intervention should be useable and acceptable to a range of users across the US who could benefit immediately from IT without directly or indirectly incurring the costs associated with clinician-intensive treatments.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging grant 1R21AG072418. The University of Wisconsin Institutional Review Board has approved this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of competing interest

RJH provides paid scientific advising to Cook Medical, LLC. The proposed technology will not be developed or owned by Cook or their subsidiaries.

References

- 1.Fiss T, Thyrian JR, Fendrich K, Berg N, Hoffmann W. Cognitive impairment in primary ambulatory health care: pharmacotherapy and the use of potentially inappropriate medicine. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2013;28(2):173–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thorpe JM, Thorpe CT, Kennelty KA, Gellad WF, Schulz R. The impact of family caregivers on potentially inappropriate medication use in noninstitutionalized older adults with dementia. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(4):230–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cotrell V, Wild K, Bader T. Medication management and adherence among cognitively impaired older adults. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2006;47(3–4):31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clague F, Mercer SW, McLean G, Reynish E, Guthrie B. Comorbidity and polypharmacy in people with dementia: insights from a large, population-based cross-sectional analysis of primary care data. Age Ageing. 2017;46(1):33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mueller C, Molokhia M, Perera G, et al. Polypharmacy in people with dementia: associations with adverse health outcomes. Exp Gerontol. 2018;106:240–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gaugler JE, Anderson KA, Leach CR, Smith CD, Schmitt FA, Mendiondo M. The emotional ramifications of unmet need in dementia caregiving. Am J Alzheimer’s Dis Other Dementias. 2004;19(6):369–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitlatch CJ, Orsulic-Jeras S. Meeting the informational, educational, and psychosocial support needs of persons living with dementia and their family caregivers. Gerontol. 2018;58(1):S58–S73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maust D, Leggett A, Kales HC. Predictors of unmet need among caregivers of persons with dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2017;25(3):S133–S134. [Google Scholar]

- 9.While C, Duane F, Beanland C, Koch S. Medication management: the perspectives of people with dementia and family carers. Dementia. 2013;12(6):734–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maidment ID, Aston L, Moutela T, Fox CG, Hilton A. A qualitative study exploring medication management in people with dementia living in the community and the potential role of the community pharmacist. Health Expect. 2017;20(5):929–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Travis SS, McAuley WJ, Dmochowski J, Bernard MA, Kao H-FS, Greene R. Factors associated with medication hassles experienced by family caregivers of older adults. Patient Educ Counsel. 2007;66(1):51–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maidment I, Lawson S, Wong G, et al. Towards an understanding of the burdens of medication management affecting older people: the MEMORABLE realist synthesis. BMC Geriatr. 2020;20(1):1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillespie RJ, Harrison L, Mullan J. Medication management concerns of ethnic minority family caregivers of people living with dementia. Dementia. 2015;14(1): 47–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gillespie R, Mullan J, Harrison L. Managing medications: the role of informal caregivers of older adults and people living with dementia. A review of the literature. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23(23–24):3296–3308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Medication adherence in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann Pharmacother. 2001;35(5):539–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Saifi N, Moyle W, Jones C. Family caregivers’ perspectives on medication adherence challenges in older people with dementia: a qualitative study. Aging Ment Health. 2019;23(10):1333–1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Checchi KD, Huybrechts KF, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. Electronic medication packaging devices and medication adherence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312 (12):1237–1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Conn VS, Ruppar TM, Chan KC, Dunbar-Jacob J, Pepper GA, De Geest S. Packaging interventions to increase medication adherence: systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(1):145–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Armitage LC, Kassavou A, Sutton S. Do mobile device apps designed to support medication adherence demonstrate efficacy? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials, with meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1), e032045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gilhooly K, Gilhooly M, Sullivan M, et al. A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, Birks Y, Barnes C, Adamson J. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laver K, Milte R, Dyer S, Crotty M. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing carer focused and dyadic multicomponent interventions for carers of people with dementia. J Aging Health. 2017;29(8):1308–1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell NL, Boustani MA, Skopelja EN, Gao S, Unverzagt FW, Murray MD. Medication adherence in older adults with cognitive impairment: a systematic evidence-based review. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2012;10(3):165–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Onken LS, Carroll KM, Shoham V, Cuthbert BN, Riddle M. Reenvisioning clinical science: unifying the discipline to improve the public health. Clin Psychol Sci. 2014;2 (1):22–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aston L, Hilton A, Moutela T, Shaw R, Maidment I. Exploring the evidence base for how people with dementia and their informal carers manage their medication in the community: a mixed studies review. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Arlt S, Lindner R, Rosler A, von Renteln-Kruse W. Adherence to medication in¨ patients with dementia. Drugs Aging. 2008;25(12):1033–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walker JM, Carayon P. From tasks to processes: the case for changing health information technology to improve health care. Health Aff. Mar-Apr 2009;28(2): 467–477. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson JR, Corlett N, Wilson J, Haines H, Morris W. Participatory Ergonomics. Evaluation of Human Work. third ed. CRC Press; 2005:933–962. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eysenbach G.The law of attrition. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7(1):e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holden RJ, Abebe E, Russ-Jara AL, Chui MA. Human factors and ergonomics methods for pharmacy research and clinical practice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17 (12):2019–2027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith F, Francis SA, Gray N, Denham M, Graffy J. A multi-centre survey among informal carers who manage medication for older care recipients: problems experienced and development of services. Health Soc Care Community. 2003;11(2): 138–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Holden RJ, Daley CN, Mickelson RS, et al. Patient decision-making personas: an application of a patient-centered cognitive task analysis (P-CTA). Appl Ergon. 2020; 87:103107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Simonse L, Albayrak A, Starre S. Patient journey method for integrated service design. Design for Health. 2019;3(1):82–97. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beyer H, Holtzblatt K. Contextual Design: Defining Customer-Centered Systems. Elsevier; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beyer H, Holtzblatt K. Contextual design. Interactions. 1999;6(1):32–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ho J, Aridor O, Parwani A. Use of contextual inquiry to understand anatomic pathology workflow: implications for digital pathology adoption. Research Article. January 1, 2012 J Pathol Inf. 2012;3(1). 10.4103/2153-3539.101794, 35–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Viitanen J.Contextual inquiry method for user-centred clinical IT system design. In: Moen A, et al. , eds. User Centred Networked Health Care. IOS Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Holden RJ, Campbell NL, Abebe E, et al. Usability and feasibility of consumer-facing technology to reduce unsafe medication use by older adults. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(1):54–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holden RJ, Srinivas P, Campbell NL, et al. Understanding older adults’ medication decision making and behavior: a study on over-the-counter (OTC) anticholinergic medications. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019;15(1):53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cheng CF, Werner NE, Barton H, Doutcheva N, Coller RJ. Co-design and usability of a mobile application to support family-delivered enteral tube care. Hosp Pediatr. In-press;. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Holden RJ, Karanam YLP, Cavalcanti LH, et al. Health information management practices in informal caregiving: an artifacts analysis and implications for IT design. Int J Med Inf. Dec 2018;120:31–41. 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Personas Friess E. and Decision Making in the Design Process: An Ethnographic Case Study. 2012:1209–1218. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pruitt J, Adlin T. The Persona Lifecycle: Keeping People in Mind throughout Product Design. Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 44.McCarthy S, O’Raghallaigh P, Woodworth S, Lim YL, Kenny LC, Adam F. An integrated patient journey mapping tool for embedding quality in healthcare service reform. J Decis Syst. 2016;25(1):354–368. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation checklist. Evaluation Checklists Project. 2003;21: 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Devers KJ. How will we know “good” qualitative research when we see it? Beginning the dialogue in health services research. Health Serv Res. Dec 1999;34(5): 1153–1188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reddy A, Lester CA, Stone JA, Holden RJ, Phelan CH, Chui MA. Applying participatory design to a pharmacy system intervention. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2019; 15(11):1358–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Routledge International Handbook of Participatory Design . first ed. Routledge; 2013: 300. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buxton B.Sketching User Experiences: Getting the Design Right and the Right Design. Morgan kaufmann; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Srinivas P, Cornet V, Holden R. Human factors analysis, design, and evaluation of Engage, a consumer health IT application for geriatric heart failure self-care. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2016. (just-accepted). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cornet VP, Daley CN, Srinivas P, Holden RJ. User-Centered Evaluations with Older Adults: Testing the Usability of a Mobile Health System for Heart Failure Self-Management. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications Sage CA; 2017:6–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nielsen J.Usability Engineering. Morgan Kaufmann; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Holden RJ. A Simplified System Usability Scale (SUS) for Cognitively Impaired and Older Adults. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care. 2020. forthcoming. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neal JW, Neal ZP, VanDyke E, Kornbluh M. Expediting the analysis of qualitative data in evaluation: a procedure for the rapid identification of themes from audio recordings (RITA). Am J Eval. 2015;36(1):118–132. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Srinivas P, Cornet V, Holden RJ. Human factors analysis, design, and testing of Engage, a consumer health IT application for geriatric heart failure self-care. Int J Hum Comput Interact. 2017;33(4):298–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Holden RJ, Asan O, Wozniak EM, Flynn KE, Scanlon MC. Nurses’ perceptions, acceptance, and use of a novel in-room pediatric ICU technology: testing an expanded technology acceptance model. BMC Med Inf Decis Making. 2016;16(1):145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holden RJ, Brown RL, Scanlon MC, Karsh B. Pharmacy employees’ perceptions and acceptance of bar-coded medication technology in a pediatric hospital. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2012;8:509–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Holden RJ, Brown RL, Scanlon MC, Karsh B. Modeling nurses’ acceptance of bar coded medication administration technology at a pediatric hospital. J Am Med Inf Assoc. 2012;19:1050–1058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Julious SA. Sample size of 12 per group rule of thumb for a pilot study. Pharmaceut Stat: J Appl Statist Pharm Ind. 2005;4(4):287–291. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Holden RJ, Brown RL, Scanlon MC, Karsh B-T. Pharmacy workers’ perceptions and acceptance of bar-coded medication technology in a pediatric hospital. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2012;8(6):509–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Asan O, Holden RJ, Flynn KE, Murkowski K, Scanlon MC. Providers’ assessment of a novel interactive health information technology in a pediatric intensive care unit. JAMIA open. 2018;1(1):32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Holden RJ, Karsh B-T. A theoretical model of health information technology usage behaviour with implications for patient safety. Behav Inf Technol. 2009;28(1):21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.MHealth W.New Horizons for Health through Mobile Technologies; Global Observatory for eHealth. 3. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lowry SZ, Abbott P, Gibbons MC, et al. Technical Evaluation, Testing, and Validatiaon of the Usability of Electronic Health Records. US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schumacher RM, Lowry SZ, Schumacher RM. NIST Guide to the Processes Approach for Improving the Usability of Electronic Health Records. US Department of Commerce, National Institute of Standards and Technology; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiklund ME, Kendler J, Hochberg L, Weinger MB. Technical Basis for User Interface Design of Health IT. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Standardization IOf. ISO/TR 16982: Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction-Usability Methods Supporting Human-Centred Design [electronic Resource]. ISO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Standardization IOf. ISO 9241–210 Ergonomics of HumanSystem Interaction Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. 2010. Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Coulter A, Ellins J. Patient-focused Interventions: A Review of the Evidence. 1. Health Foundation London; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kushniruk A, Nøhr C. Participatory design, user involvement and health IT evaluation. Stud Health Technol Inf. 2016;222:139–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Abras C, Maloney-Krichmar D, Preece J. Bainbridge, W Encyclopedia of Human-Computer Interaction Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. User-centered Design. 37. 2004:445–456, 4. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Evenson S, Muller M, Roth EM. Capturing the context of use to inform system design, 2020/07/01 J Cognitive Eng Dec Mak. 2008;2(3):181–203. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mackrill J, Marshall P, Payne SR, Dimitrokali E, Cain R. Using a bespoke situated digital kiosk to encourage user participation in healthcare environment design, 2017/03/01 Appl Ergon. 2017;59:342–356. 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bratteteig T, Wagner I. Disentangling Participation: Power and Decision-Making in Participatory Design. Springer; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cantarero-Arevalo L, Werremeyer A. Community involvement and awareness raising for better development, access and use of medicines: the transformative potential of photovoice. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2021;17(12):2062–2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goldberg L, Lide B, Lowry S, et al. Usability and accessibility in consumer health informatics: current trends and future challenges. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40(5): S187–S197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mathews SC, McShea MJ, Hanley CL, Ravitz A, Labrique AB, Cohen AB. Digital health: a path to validation. NPJ Digital Med. 2019;2(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Weinger MB, Wiklund ME, Gardner-Bonneau DJ. Handbook of Human Factors in Medical Device Design. CRC Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]