Abstract

Background:

Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and their food sources have garnered interest as a potential nutrient with wide-range health benefits including fertility.

Objective:

To investigate the association of women’s and men’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich-foods with semen quality and outcomes of infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technologies (ART).

Study Design:

Couples presenting to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) were invited to enroll in a prospective cohort-study (2007–2020). Male and female diet was assessed using a validated 131-item food-frequency questionnaire. Primary outcomes were implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth probabilities. Secondary outcomes included total and clinical pregnancy loss, and conventional semen parameters, for males only. We estimated the relationship of intakes of omega-3 fatty acids, nuts, and fish intake with the probability (95%CI) of study outcomes using Generalized Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) to account for repeated treatment cycles per participant, while simultaneously adjusting for age, BMI, smoking status, education, dietary patterns, total energy intake, and male partner diet.

Results:

A total of 229 couples and 410 ART cycles were analyzed for primary and secondary outcomes; 343 men contributing 896 semen samples were included in analyses for semen quality measures. Women’s DHA+EPA intake was positively associated with live birth. The multivariable-adjusted probabilities of live birth (95% CI) for women in the bottom and top quartiles of EPA+DHA intake were 0.36 (0.26–0.48) and 0.54 (0.42–0.66) (P-trend=0.02). EPA+DHA intake was inversely related to the risk of pregnancy loss, which was of 0.53 among women in the lowest quartile of EPA+DHA intake and 0.05 among women in the highest quartile (P-trend=0.01). Men’s intake of total omega-3 fatty acids was positively related to sperm count, concentration, and motility, but unrelated to any ART outcomes. Similar associations were observed when evaluating intake of primary food sources of these fatty acids.

Conclusions:

Women’s consumption of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich-foods may improve the probability of conception by decreasing the risk of pregnancy loss. In addition, men’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids may influence semen quality.

Keywords: Male diet, female diet, omega-3, nuts, fish, semen parameters, assisted reproductive technologies, infertility

Condensation:

Women’s consumption of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich-foods may improve the probability of live birth in ART by decreasing the risk of pregnancy loss.

INTRODUCTION

Omega-3 fatty acids, and their food sources such as nuts and fish, have garnered interest for their potential influence on fertility.1–3 Previous studies suggest that women’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids may be beneficial for fertility among couples without a history of infertility.4 We have also reported that women’s serum omega-3 fatty acids5 and fish consumption6 are positively associated with live birth during infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Previous work also suggests that men’s dietary omega-3, as well as fish consumption or fish oil supplement use, is positively associated with semen quality.7–10 Moreover, data from randomized clinical trials (RCT) also shows positive effects of nuts consumption and semen quality among men in the general population.11,12 However, we have previously reported no association between men’s fish intake and outcomes of infertility treatment with ART.13

Despite evidence suggesting that men’s and women’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich foods may positively influence couples’ fertility, studies simultaneously considering intakes of both prospective parents are scant. This raises questions about the extent to which associations with women’s intake may partly reflect associations with their partner’s intake given the degree of concordance in intake of food sources of omega-3 fatty acids within couples. To our knowledge this question has only been addressed by one previous study among pregnancy planners, which found that both male and female partner intake of seafood was related to a shorter time to pregnancy.14 No previous study has addressed this issue in couples undergoing infertility treatment. Thus, the objectives of the present study were to investigate the association of women’s and men’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich foods (nuts and fish) with ART outcomes among couples undergoing assisted reproduction, as well as men’s intake with semen quality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

Between 2004–2020, couples presenting to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Fertility Center for evaluation and treatment of infertility were invited to participate in the EARTH Study, a prospective cohort study aimed at identifying environmental and nutritional determinants of fertility.15 Couples were eligible to participate if they were within the target age range (18–55 years for men; 18–45 years for women) and were planning to use their own gametes for infertility treatment. Diet assessments were introduced in 2007. The study was approved by the institutional review boards of MGH, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. All participants provided informed consent for participation.

For this analysis, we selected all couples where both partners completed a diet assessment before treatment, and the female partner completed at least one ART cycle. From the 462 couples who joined the study since 2007, 104 were excluded because the male partner did not complete a diet assessment. For evaluation of semen quality, 15 men were excluded because of azoospermia, leaving 896 semen samples from 343 men available for analysis. For ART outcomes evaluation, we excluded 113 couples because they were treated with Intrauterine Insemination (IUI) and 16 couples whose treatment had started before diet assessment. The remaining 229 couples, who underwent 410 ART cycles, were included in the analysis (Supplemental Figure 1). In these couples, 9 women had incomplete diet data, which was imputed using the median values in the overall study population in order to maximize statistical power.

Diet assessment

Diet was assessed using a validated 131-item, food frequency questionnaire (FFQ).16–18 Participants were asked to report how often they consumed listed foods and beverages during the previous year. Nutrient content of each item evaluated was calculated with the nutrient database of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.19 We considered intakes of 1) long-chain omega-3 (LCN-3) (defined as the sum of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), total omega-3 fatty acids (defined as the sum of LCN-3 and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA)); and 2) of foods rich in omega-3 fatty acids (nuts and fish). Total nut consumption was defined as the sum of peanuts, walnuts, and other nuts (e.g., almonds, hazelnuts). Total fish consumption was defined as the sum of dark, white and shellfish. In validation studies, the correlation (95% CI) between intake of omega-3 fatty acids estimated by FFQ and plasma levels spaced ~6 months apart was 0.62 (0.56–0.68), which is superior to the correlations comparing plasma levels against multiple 24-hour recalls, and comparable to using 14 days of weighted diet records.18 The Prudent and the Western dietary patterns were identified using principal component analysis as described elsewhere.20 Higher scores indicated higher adherence to the respective pattern.

Clinical management and outcomes assessment

At enrollment, weight and height were measured. Participants completed a detailed questionnaire with information on family, medical and reproductive, and occupational history, and lifestyle factors.

Women underwent one of three stimulation protocols as clinically indicated: antagonist, flare or luteal phase agonist. Primary outcomes of this study were implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth. Clinicians evaluated fertilization status on day 1 after fertilization based on the presence of two pronuclei (2PN). Embryo transfer was performed following stimulation and retrieval or following thawing of cryopreserved embryos.15 Implantation was assessed 14–15 days after embryo transfer and defined as a serum β-hCG >6 mIU/mL. Clinical pregnancy was defined as the presence of an intrauterine gestational sac confirmed by ultrasound at ~6 weeks of gestation. Live birth was defined as the birth of a neonate at or after 24 weeks of gestation. Secondary outcomes included total pregnancy loss, defined as a positive β-hCG that did not result in live birth, and clinical pregnancy, defined as a clinical pregnancy that did not result in live birth. For men, secondary outcomes also included conventional semen parameters: ejaculate volume, sperm count and concentration, total and progressive motility, and morphology. Semen was collected by masturbation following a recommended 48-h period of sexual abstinence. Some men provided multiple semen samples. Semen parameters were assessed based on 2010 WHO manual guideline after 30-min liquefaction by computer-assisted semen analysis (CASA) system (HTM-IVOS, USA).21–23

Statistical analyses

Participants were categorized into quartiles of total omega-3, total nuts and total fish intake. Baseline participant’s characteristics were presented as median (interquartile range) or n (%) and differences were compared across quartiles of total omega-3 intake using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Chi-square or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Spearman correlations were used to describe within-couple similarities in intakes of omega-3 fatty acids, nuts, and fish. For primary study outcomes (implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth), all women who started a cycle were included in the analysis. For secondary outcomes, total pregnancy loss and clinical pregnancy loss, only women who achieved either a biochemical or clinical pregnancy, respectively, were included in the analysis. We estimated the probability and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) for ART outcomes by fitting multivariable generalized linear mixed models with binomial (implantation, clinical pregnancy, live birth, and total and clinical pregnancy loss) distribution and random intercepts to account for repeated cycles. We estimated the marginal means (95% CI) for semen parameters by fitting multivariable linear mixed models (GLMM) with repeated intercepts to account for repeated semen samples. Tests for linear trend were performed by modeling intake as a continuous variable where each man/woman was assigned the median intake of each category.

Our primary analysis focused on absolute intakes using the standard multivariable method to adjust for total energy intake.24 To evaluate the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitivity analyses using the nutrient residual method and the multivariable energy density method to adjust for total energy intake.24 Confounding factors were evaluated using previous knowledge on biological relevance and descriptive statistics from our cohort (Table 1). Fully adjusted models for men’s omega-3 associations included terms for male age (years), BMI (kg/m2), energy intake (kcal/d), education (high school or less, college or higher), Prudent and Western patterns and female omega-3 intake. Fully adjusted models for women’s omega-3 associations included terms for female age, BMI, energy intake, smoking status (never or ever), education, Prudent and Western patterns and male omega-3 intake. Fully adjusted models for men’s nuts and fish associations included terms for male age and BMI, male energy intake, male education, male Prudent and Western patterns, female total fish intake (for nuts models) or female total nuts intake (for fish models). Fully adjusted models for women’s nuts and fish associations included terms for female age and BMI, female energy intake, female smoking status, female education, female Prudent and Western patterns, male total fish intake (for nuts models) or male total nuts intake (for fish models). The final adjusted multivariable models for semen quality parameters included age and BMI, energy intake, physical activity (min/week), race (white or other), smoking status, and sexual abstinence time (days). Of note, we adjusted for physical activity in models for semen quality but not in models for ART outcomes because we have previously reported that men’s physical activity is related to semen quality in this and other cohorts25–27, but men’s and women’s physical activity are unrelated to ART outcomes in this cohort.25,28 To test the robustness of our findings to missing data assumptions of GLMM models and imputation of missing diet data, we repeated our analyses using cluster-weighed generalized estimating equation (CW-GEE) models and excluding women with incomplete diet data. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, USA).

Table 1.

Baseline demographic, nutritional and reproductive characteristics of study participants, overall and in lowest and highest quartiles of men’s and women’s total omega-3 intake.

| Overall | Men’s total omega-3 intake (g/day) | P-value | Women’s total omega-3 intake (g/day) | P-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (1.06–3.12) | Q4 (4.77–9.49) | Q1 (1.27–2.64) | Q4 (4.45–8.23) | ||||

| n | 229 | 57 | 57 | 57 | 57 | ||

| Male demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (y) | 36.0 (33.6, 39.3) | 36.0 (33.6, 38.8) | 37.2 (34.4, 40.5) | 0.39 | 36.0 (32.9, 38.5) | 36.6 (33.7, 40.4) | 0.40 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.0 (24.3, 28.9) | 27.8 (25.4, 29.7) | 27.8 (25.7, 29.5) | 0.03 | 27.0 (24.3, 29.1) | 27.0 (24.1, 29.3) | 0.89 |

| Race, white | 211 (92) | 51 (22) | 54 (24) | 0.76 | 51 (22) | 53 (23) | 0.82 |

| Smoking status, ever smoker | 44 (19) | 12 (5) | 13 (6) | 0.76 | 7 (3) | 12 (5) | 0.43 |

| Education, college or higher | 199 (87) | 48 (21) | 47 (21) | 0.34 | 52 (23) | 49 (21) | 0.73 |

| Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (min/week) | 180.0 (60.0, 390.0) | 161.5 (44.0, 329.5) | 296.0 (118.5, 390.0) | 0.28 | 150.0 (41.5, 341.0) | 239.0 (112.5, 390.0) | 0.34 |

| Sexual abstinence (days) | 2.4 (2.4, 2.5) | 2.4 (1.8, 3.4) | 2.5 (2.0, 3.4) | 0.77 | 2.4 (2.4, 2.5) | 2.4 (2.4, 2.6) | 0.55 |

| Male dietary parameters | |||||||

| Energy intake (kcal/day) | 1937 (1592, 2414) | 1402 (1152, 1664) | 2623 (2165, 2991) | <0.001 | 1741 (1468, 2191) | 2144 (1731, 2534) | <0.001 |

| Prudent pattern score | −0.1 (−0.6, 0.6) | −0.6 (−1.0, −0.3) | 0.7 (−0.1, 1.8) | <0.001 | −0.5 (−0.8, 0.5) | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.9) | 0.04 |

| Western pattern score | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.5) | −0.7 (−1.1, −0.4) | 0.7 (−0.3, 1.2) | <0.001 | −0.6 (−1.1, 0.0) | 0.1 (−0.5, 1.0) | <0.001 |

| Total omega-3 | 3.8 (3.2, 4.8) | 2.7 (2.2, 2.9) | 5.6 (5.2, 6.8) | <0.001 | 2.9 (2.3, 3.7) | 4.0 (3.5, 4.8) | <0.001 |

| Female demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Age (y) | 35.0 (32.0, 38.0) | 35.0 (31.0, 38.0) | 35.0 (33.0, 38.0) | 0.74 | 35.0 (32.0, 37.0) | 35.0 (32.0, 37.0) | 0.28 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.0 (21.0, 25.7) | 23.5 (20.8, 25.7) | 22.7 (20.9, 25.0) | 0.39 | 22.6 (20.8, 24.2) | 23.8 (21.6, 27.9) | 0.28 |

| Race, white | 194 (85) | 45 (20) | 47 (21) | 0.37 | 46 (20) | 49 (21) | 0.81 |

| Smoking status, ever smoker | 59 (26) | 11 (5) | 19 (8) | 0.15 | 12 (5) | 14 (6) | 0.57 |

| Education, college or higher | 214 (94) | 54 (24) | 53 (23) | 0.84 | 52 (23) | 55 (24) | 0.47 |

| Moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (min/week) | 149.0 (29.5, 298.5) | 114.0 (12.0, 210.0) | 150.0 (29.5, 332.5) | 0.03 | 113.5 (12.0, 210.0) | 191.5 (60.0, 392.5) | 0.02 |

| Female dietary parameters | |||||||

| Energy intake (kcal/day) | 1675 (1319, 2004) | 1492 (1148, 1694) | 1796 (1683, 2142) | <0.001 | 1148 (994, 1369) | 2158 (1841, 2514) | <0.001 |

| Prudent pattern score | −0.3 (−0.7, 0.3) | −0.4 (−0.8, 0.2) | 0.0 (−0.5, 0.4) | 0.02 | −0.7 (−1.0, −0.4) | 0.4 (−0.1, 0.8) | <0.001 |

| Western pattern score | −0.2 (−0.7, 0.5) | −0.4 (−0.9, 0.0) | 0.2 (−0.4, 1.0) | <0.001 | −0.8 (−1.0, −0.6) | 0.3 (−0.2, 1.1) | <0.001 |

| Total omega-3 | 3.5 (2.7, 4.4) | 3.5 (2.7, 3.8) | 4.5 (3.8, 5.9) | <0.001 | 2.1 (1.7, 2.4) | 5.0 (4.8, 5.8) | <0.001 |

| Baseline cycle characteristics | |||||||

| Infertility diagnosis | 0.29 | 0.91 | |||||

| Female factor | 79 (35) | 21 (9) | 17 (7) | 18 (8) | 18 (8) | ||

| Male factor | 87 (38) | 25 (11) | 18 (8) | 23 (10) | 21 (9) | ||

| Unexplained | 63 (28) | 11 (5) | 22 (10) | 16 (7) | 18 (8) | ||

| Treatment protocol | 0.62 | 0.96 | |||||

| Antagonist | 32 (14) | 10 (4) | 7 (3) | 10 (4) | 8 (4) | ||

| Flare | 19 (8) | 7 (3) | 4 (2) | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | ||

| Luteal phase agonist | 160 (70) | 37 (16) | 41 (18) | 37 (16) | 41 (18) | ||

| Egg donor or cryo cycle | 18 (8) | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 4 (2) | ||

| Embryo transfer day | 0.22 | 0.21 | |||||

| Day 2 | 10 (5) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | ||

| Day 3 | 80 (42) | 22 (12) | 19 (10) | 12 (6) | 28 (15) | ||

| Day 5 | 101 (53) | 26 (14) | 23 (12) | 29 (15) | 22 (12) | ||

| Number of embryos transferred | 0.40 | 0.75 | |||||

| One embryo | 66 (35) | 19 (10) | 11 (6) | 16 (8) | 19 (10) | ||

| Two embryos | 97 (51) | 23 (12) | 31 (16) | 23 (12) | 22 (12) | ||

| Three or more embryos | 27 (14) | 7 (4) | 5 (3) | 5 (3) | 9 (5) | ||

Data are presented as median (interquartile range) for continuous variables or n (%) for categorical variables. Analyses were run using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and Chi-square test was used for evaluating differences across categories of primary infertility diagnosis, initial stimulation protocol, embryo transfer day and number of embryos transferred.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; n, sample size.

RESULTS

Median (interquartile range; IQR) age and BMI were 36.0 (33.6, 39.3) years and 27.0 (24.3, 28.9) kg/m2 for men; and 35.0 (32.0, 38.0) years and 23.0 (21.0, 25.7) kg/m2 for women. Total omega-3 intake was very similar in men (1.9% of energy) and women (1.8% of energy), with a median (range) intake of 3.84 g/day (1.06 to 9.49) and 3.46 g/day (1.27 to 8.23), respectively (Table 1). The median (IQR) intake of omega-3 fatty acids from supplements was 0 g/d (0, 0.2) in both men and women. The within-couple Spearman correlation for intakes of omega-3 fatty acids, nuts intake and fish intake were rho=0.39, rho=0.31 and rho=0.38, respectively. Baseline demographic, nutritional and reproductive characteristics of study participants, according to men’s and women’s total nut and total fish intake are shown in Supplemental Tables 1–4.

Women’s DHA+EPA and total fish intakes were positively associated with the probability of live birth (Table 2). The multivariable-adjusted probability (95%CI) of live birth for women in the lowest and highest quartile of DHA+EPA and total fish intake were 0.36 (0.26, 0.48) and 0.54 (0.42, 0.66); P-trend=0.02, and 0.36 (0.26, 0.48) and 0.54 (0.41, 0.66); P-trend=0.04, respectively. When specific types of fish were examined, the association was strongest for intake of shellfish (Supplemental Table 5). Women’s intake of total omega-3, ALA, total nuts (Table 2), and specific types of nuts (Supplemental Table 5), were unrelated to implantation, clinical pregnancy and live birth probabilities. Men’s intakes of total omega-3, DHA+EPA, ALA, nuts and fish (Table 3), as well as intakes of specific nuts (peanuts, walnuts, and other nuts) and fish (dark fish, white fish, and shellfish) (Supplemental Table 6), were unrelated to the probabilities of implantation, clinical pregnancy or live birth.

Table 2.

Association between women’s total omega-3, DHA+EPA, ALA, total nuts and total fish intake and probabilities of implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth following ART in couples from the EARTH study. 1

| Number of women (n=229)/cycles (n=408) | Implantation probability | Clinical pregnancy probability | Live birth probability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total omega-3 3 | Q1 | 57/99 | 0.53 (0.40, 0.67) | 0.50 (0.37, 0.64) | 0.34 (0.22, 0.48) |

| Q2 | 49/85 | 0.54 (0.41, 0.65) | 0.48 (0.36, 0.60) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.49) | |

| Q3 | 66/128 | 0.52 (0.42, 0.62) | 0.48 (0.38, 0.58) | 0.36 (0.27, 0.46) | |

| Q4 | 57/96 | 0.58 (0.43, 0.71) | 0.53 (0.39, 0.67) | 0.52 (0.37, 0.66) | |

| P-trend | 0.77 | 0.81 | 0.19 | ||

| DHA+EPA | Q1 | 56/96 | 0.58 (0.46, 0.69) | 0.54 (0.43, 0.65) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.48) |

| Q2 | 65/125 | 0.51 (0.41, 0.60) | 0.46 (0.37, 0.56) | 0.33 (0.24, 0.43) | |

| Q3 | 50/95 | 0.50 (0.39, 0.62) | 0.46 (0.35, 0.57) | 0.36 (0.25, 0.48) | |

| Q4 | 58/92 | 0.58 (0.46, 0.69) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.65) | 0.54 (0.42, 0.66) 2 | |

| P-trend | 0.88 | 0.87 | 0.02 | ||

| ALA | Q1 | 57/104 | 0.49 (0.36, 0.63) | 0.46 (0.33, 0.60) | 0.32 (0.20, 0.45) |

| Q2 | 49/68 | 0.61 (0.47, 0.73) | 0.54 (0.41, 0.67) | 0.45 (0.32, 0.58) | |

| Q3 | 66/138 | 0.48 (0.39, 0.57) | 0.44 (0.35, 0.53) | 0.30 (0.22, 0.40) | |

| Q4 | 57/98 | 0.62 (0.47, 0.75) | 0.58 (0.43, 0.71) | 0.54 (0.39, 0.69) | |

| P-trend | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.21 | ||

| Total nuts 4 | Q1 | 56/98 | 0.50 (0.38, 0.61) | 0.47 (0.36, 0.58) | 0.38 (0.27, 0.50) |

| Q2 | 67/127 | 0.57 (0.47, 0.66) | 0.52 (0.42, 0.61) | 0.39 (0.30, 0.50) | |

| Q3 | 49/82 | 0.55 (0.43, 0.67) | 0.50 (0.38, 0.62) | 0.41 (0.30, 0.54) | |

| Q4 | 57/101 | 0.53 (0.41, 0.65) | 0.49 (0.38, 0.61) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.51) | |

| P-trend | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 | ||

| Total fish 5 | Q1 | 58/99 | 0.55 (0.43, 0.66) | 0.52 (0.41, 0.63) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.48) |

| Q2 | 67/132 | 0.49 (0.39, 0.59) | 0.42 (0.33, 0.51) | 0.31 (0.23, 0.40) | |

| Q3 | 48/85 | 0.54 (0.42, 0.66) | 0.48 (0.37, 0.60) | 0.38 (0.27, 0.50) | |

| Q4 | 56/92 | 0.60 (0.48, 0.71) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.69) | 0.54 (0.41, 0.66) 2 | |

| P-trend | 0.52 | 0.48 | 0.04 |

Data are presented as predicted marginal proportions and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were run using generalized linear mixed models (proc glimmix) with random intercepts, binary distribution, and logit link.

Fully adjusted model: Female age and BMI, female energy intake, female smoking status, female education, female Prudent and Western patterns, male total omega-3 intake (for omega-3 models) male total fish intake (for nuts models) or male total nuts intake (for fish models).

P<0.05 for comparison of specific quartile versus quartile 1 (reference).

Total omega-3 included ALA, DHA and EPA.

Total nuts included peanuts, walnuts, and other nuts.

Total fish included dark fish, white fish, and shellfish.

Abbreviations: ART, assisted reproductive technologies; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EARTH, Environment and Reproductive Health; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; n, sample size; Q, quartile.

Table 3.

Association between men’s total omega-3, DHA+EPA, ALA, total nuts and total fish intake and probabilities of implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth following ART in couples from the EARTH study. 1

| Number of women (n=229)/cycles (n=410) | Implantation probability | Clinical pregnancy probability | Live birth probability | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total omega-3 c | Q1 | 57/96 | 0.47 (0.34, 0.61) | 0.47 (0.34, 0.60) | 0.36 (0.24, 0.50) |

| Q2 | 57/94 | 0.60 (0.48, 0.70) | 0.58 (0.47, 0.69) | 0.45 (0.33, 0.57) | |

| Q3 | 58/108 | 0.51 (0.40, 0.61) | 0.46 (0.35, 0.56) | 0.37 (0.27, 0.48) | |

| Q4 | 57/112 | 0.59 (0.46, 0.72) | 0.48 (0.36, 0.61) | 0.39 (0.26, 0.53) | |

| P-trend | 0.42 | 0.84 | 0.99 | ||

| DHA+EPA | Q1 | 62/111 | 0.52 (0.41, 0.62) | 0.48 (0.37, 0.59) | 0.36 (0.26, 0.48) |

| Q2 | 53/97 | 0.54 (0.43, 0.65) | 0.52 (0.41, 0.63) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.51) | |

| Q3 | 57/107 | 0.46 (0.36, 0.57) | 0.43 (0.33, 0.53) | 0.32 (0.23, 0.43) | |

| Q4 | 57/95 | 0.66 (0.54, 0.76) | 0.58 (0.46, 0.69) | 0.48 (0.36, 0.60) | |

| P-trend | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.19 | ||

| ALA | Q1 | 57/97 | 0.44 (0.31, 0.58) | 0.42 (0.30, 0.56) | 0.33 (0.22, 0.48) |

| Q2 | 57/94 | 0.58 (0.46, 0.69) | 0.56 (0.44, 0.67) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.55) | |

| Q3 | 59/111 | 0.54 (0.43, 0.64) | 0.49 (0.39, 0.59) | 0.39 (0.29, 0.50) | |

| Q4 | 56/108 | 0.61 (0.47, 0.74) | 0.52 (0.38, 0.65) | 0.41 (0.27, 0.56) | |

| P-trend | 0.22 | 0.56 | 0.61 | ||

| Total nuts d | Q1 | 60/108 | 0.45 (0.34, 0.57) | 0.43 (0.32, 0.54) | 0.34 (0.24, 0.46) |

| Q2 | 53/93 | 0.60 (0.49, 0.71) | 0.52 (0.41, 0.63) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.54) | |

| Q3 | 58/108 | 0.56 (0.45, 0.66) | 0.52 (0.41, 0.62) | 0.37 (0.27, 0.49) | |

| Q4 | 58/101 | 0.56 (0.44, 0.67) | 0.51 (0.40, 0.63) | 0.42 (0.31, 0.54) | |

| P-trend | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.57 | ||

| Total fish e | Q1 | 57/106 | 0.48 (0.37, 0.60) | 0.45 (0.34, 0.56) | 0.35 (0.25, 0.47) |

| Q2 | 62/108 | 0.58 (0.47, 0.68) | 0.53 (0.42, 0.63) | 0.40 (0.30, 0.51) | |

| Q3 | 50/88 | 0.52 (0.40, 0.63) | 0.47 (0.35, 0.59) | 0.38 (0.27, 0.51) | |

| Q4 | 60/108 | 0.58 (0.46, 0.69) | 0.53 (0.42, 0.64) | 0.39 (0.28, 0.51) | |

| P-trend | 0.37 | 0.43 | 0.67 |

Data are presented as predicted marginal proportions and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were run using generalized linear mixed models (proc glimmix) with random intercepts, binary distribution, and logit link.

Fully adjusted model: Male age and BMI, male energy intake, male education, male Prudent and Western patterns, female omega-3 intake (for omega-3 models) or female total fish intake (for nuts models) or female total nuts intake (for fish models).

P<0.05 for comparison of specific quartile versus quartile 1 (reference).

Total omega-3 included ALA, DHA and EPA.

Total nuts included peanuts, walnuts, and other nuts.

Total fish included dark fish, white fish, and shellfish.

Abbreviations: ART, assisted reproductive technologies; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EARTH, Environment and Reproductive Health; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; n, sample size; Q, quartile.

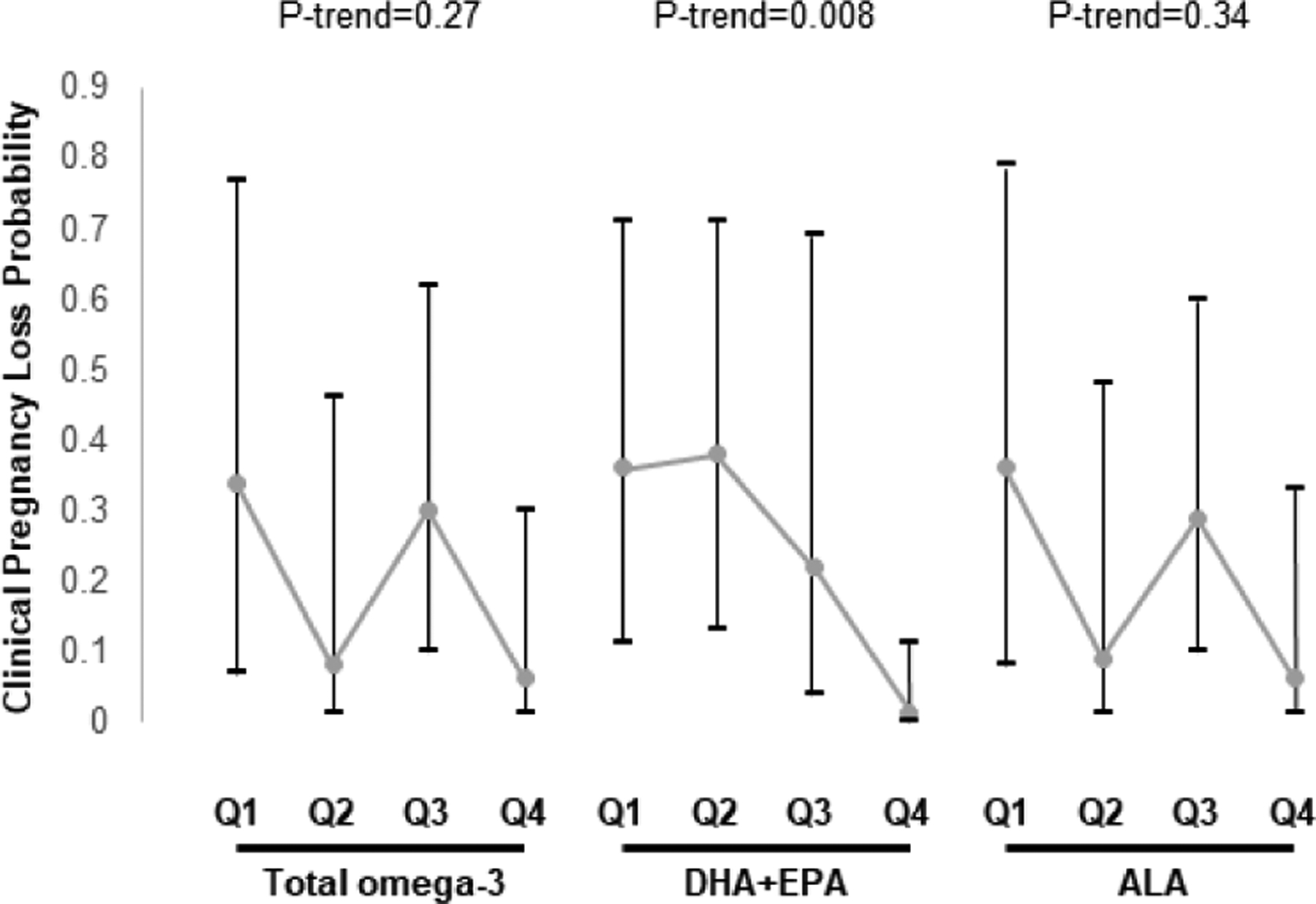

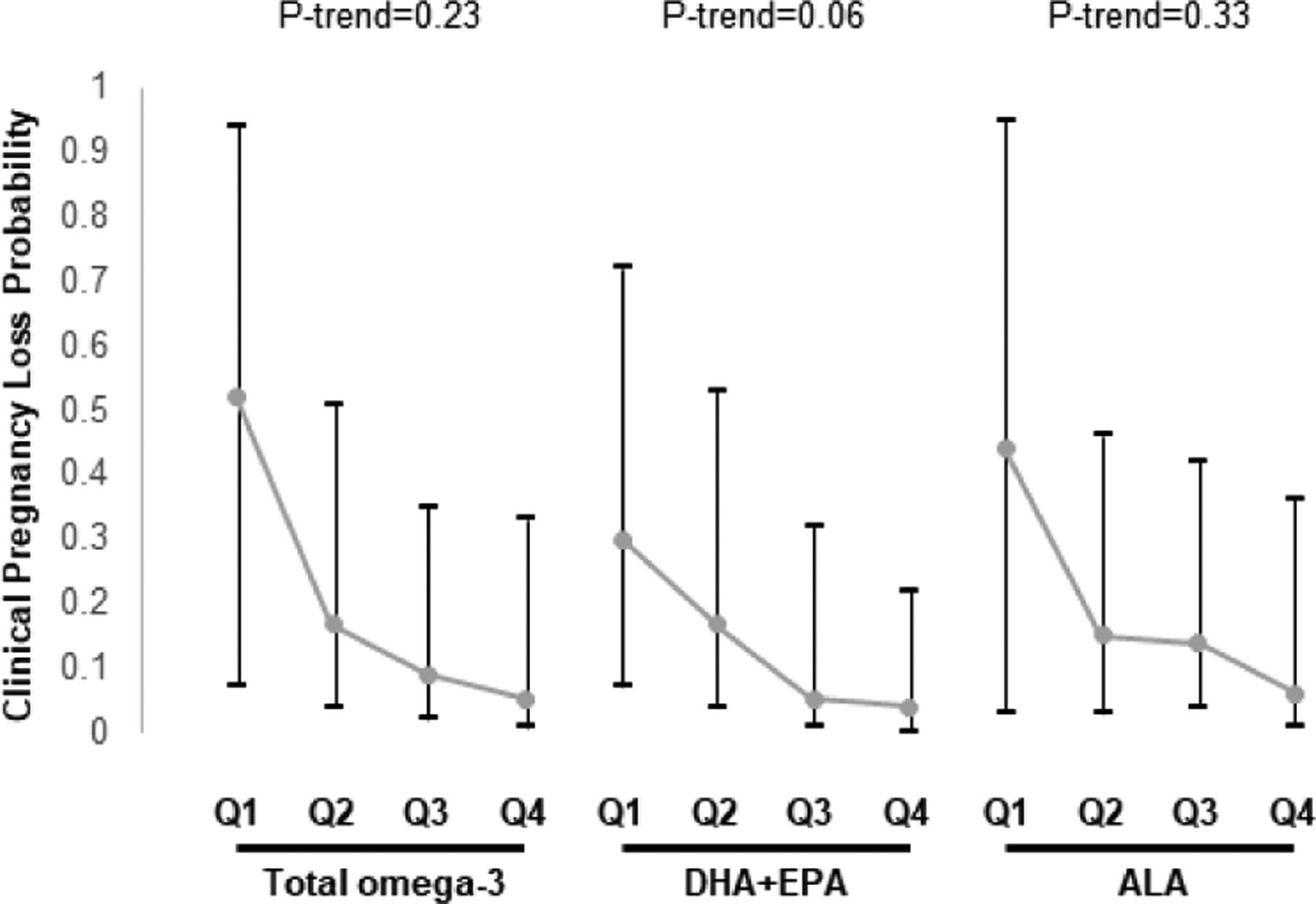

Women’s and men’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids, fish or nuts, overall and in sub-categories, was not related to total pregnancy loss (Supplemental Table 7). Nevertheless, women’s intake of EPA+DHA was inversely associated to risk of total pregnancy loss (Supplemental Table 7). When analyses were restricted to clinical pregnancies, there was a significant inverse association between women’s DHA+EPA intake and clinical pregnancy loss (Figure 1). The predicted marginal probabilities (95%CI) for clinical pregnancy loss were 0.36 (0.11, 0.71) for women in the lowest quartile of EPA+DHA intake and 0.01 (0, 0.11) for women in the highest quartile of intake (P-trend=0.008). A similar pattern was observed for men’s intake of EPA+DHA (P-trend=0.06) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Association between women’s total omega-3, DHA+EPA, and ALA intake and probability of clinical pregnancy loss following ART in couples from the EARTH study. 1

Data are presented as predicted marginal proportions and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were run using generalized linear mixed models (proc glimmix) with random intercepts, binary distribution, and logit link.

1 Fully adjusted model: Female age and BMI, female energy intake, female smoking status, female education, female Prudent and Western patterns, male total omega-3 intake.

Abbreviations: ALA, alpha linolenic acid; ART, assisted reproductive technologies; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EARTH, Environment and Reproductive Health; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; Q, quartile.

Figure 2.

Association between men’s total omega-3, DHA+EPA, and ALA intake and probability of clinical pregnancy loss following ART in couples from the EARTH study. 1

Data are presented as predicted marginal proportions and 95% confidence intervals. Analyses were run using generalized linear mixed models (proc glimmix) with random intercepts, binary distribution, and logit link.

1 Fully adjusted model: Male age and BMI, male energy intake, male education, male Prudent and Western patterns, female omega-3 intake.

Abbreviations: ALA, alpha linolenic acid; ART, assisted reproductive technologies; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; EARTH, Environment and Reproductive Health; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; Q, quartile.

The associations of women’s (Supplemental Table 8) and men’s (Supplemental Table 9) intake of omega-3, DHA+EPA and ALA with ART outcomes and pregnancy loss were nearly identical to the primary analysis when adjusting for total energy intake using the nutrient residual or the nutrient density method (Supplemental Tables 8–9). Similarly, the associations of women’s intake with live birth, total pregnancy loss and clinical pregnancy loss, were nearly identical when using CW-GEE models to account for repeated treatment cycles (Supplemental Table 10) and excluding the women with incomplete diet data (Supplemental Table 11).

Last, we evaluated the relation of omega-3 intake and omega-3 rich foods consumption with semen quality (Supplemental Figure 1). Overall, we found no associations between omega-3 rich foods consumption and semen parameters except for a positive association between greater intake of walnuts and total sperm count (Supplemental Table 12). We also found positive associations of greater intake of total omega-3 fatty acids with total sperm count, sperm concentration, total sperm motility and progressive sperm motility (Supplemental Table 12). Similarly, men’s ALA intake was positively associated with total sperm count and sperm concentration (Supplemental Table 12).

COMMENT

Principal findings

In this large prospective cohort of couples undergoing infertility treatment, we found that women’s DHA+EPA intake was related to a higher probability of achieving a live birth with ART. This association appeared to be the result of a lower probability of pregnancy loss. We also observed a suggestion of an inverse association between men’s intake of DHA+EPA with risk of clinical pregnancy loss. Moreover, we found that men’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and particularly of ALA, was positively associated with sperm count and concentration.

Results in context

The literature about the relation of women’s omega-3 intake and omega-3 rich foods consumption with fertility outcomes is scarce and contradictory (Supplemental Table 13). In agreement with our findings, we previously reported5 in a sample of 100 women from the EARTH cohort that serum omega-3, measured between Day 3 and 9 of stimulated cycles, was positively associated with the probability of achieving a live birth during the course of infertility treatment with ART. We also previously reported that pre-conception fish consumption was positively associated with the probability of live birth during ART.6 In neither of our previous reports we simultaneously accounted for intake of omega-3 PUFAs or their food sources in the male partner nor evaluated the relation of their intake with the risk of pregnancy loss. Although in our study we described that omega-3 intake is associated with higher live birth and clinical pregnancy loss rates, Stanhiset et al., recently found no associations between serum concentrations of omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids and the probability of conceiving, miscarriage, or ovarian reserve number, among couples attempting natural pregnancy.29

Multiple mechanisms may play a central role in this regard. Animal in-vivo studies suggest that lifelong consumption of a diet rich in omega-3 PUFAs prolongs murine reproductive function and improves oocyte quality.30 In this regard, our study pointed out to the long chain omega-3 PUFAs (EPA and DHA) as the major players in fertility in comparison with the short-chain omega-3 types (e.g., ALA). Recently, one interventional animal study using deficient mouse mutant lacking FADS2, an enzyme with key activity in the biosynthesis of omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, demonstrated the existence of a membrane structure-based molecular link between nutrient omega-3 and omega-6 PUFAs, gonadal membrane structures, and female and male fertility.31 Other studies described that trans fatty acids may promote greater insulin resistance, and therefore adversely affect ovulatory function.32,33 Although our study is an updated analysis from two previous papers we provide additional insights on the inverse association between DHA+EPA intake and clinical and total pregnancy loss outcomes. Our study also shows that residual confounding by men’s diet on the relation between women’s omega-3 intake and ART outcomes is not of major concern.

The present results are significant in another major respect. This study shows a possible benefit of men’s omega-3 intakes on conventional semen parameters. Although there is an overall consistency of the literature showing positive associations with seminogram, some inconsistencies across studies should be noted. While some studies showed more benefits for nuts consumption (or ALA intake) some others displayed more benefits for fish consumption (or EPA/DHA intake). These inconsistencies can be explained understanding the major pathways of PUFA metabolism reflecting different activity of the metabolic pathway because of different baseline intake of EPA/DHA across populations.5 In agreement with our findings, omega-3 intake was previously positively associated with sperm morphology7 and lower asthenozoospermia odds8 comparing infertile men vs. age-matched controls. Interestingly, our data are in agreement with two RCT assessing the effects of mixed nuts (walnuts, almonds and hazelnuts)11 or isolated walnuts12 on semen quality which described that dietary intervention with nuts improves several seminogram parameters including sperm count, vitality, motility, and morphology. Nuts are nutrient-dense foods rich in unsaturated fatty acids and, specifically, walnuts are rich in ALA34. Regarding omega-3 rich foods, contrary to our results, Afeiche et al.9 reported that consuming fish instead of meat is related to better semen quality indicators (e.g. sperm counts and morphology). Here we found instead a positive association between walnuts consumption and total sperm count. Interestingly, in a large healthy young men cohort10, Jensen et al., found positive associations between fish oils supplements and semen volume, sperm count and testicular size, and observed negative ones with FSH and LH levels. In general, the present study found no associations between men’s fish or nuts consumption and ART outcomes, in agreement with an earlier report from our group.13

Clinical implications

It is worth mentioning that the positive associations that we observed for semen quality did not translate into ART outcomes. This is not the first report suggesting these kinds of associations. In fact previous work from our group also suggested that data-derived dietary patterns (a-posteriori dietary patterns) were associated with semen quality (e.g., sperm concentration) but unrelated to the probability of successful ART outcomes.35 This previous report is in line with our results suggesting that, in infertile couples treated with ART, men’s diet although can influence sperm quality parameters, are unlikely to cause a significant impact to ART main outcomes. Another interesting point to mention is the suggestion of the inverse relation with clinical losses for men’s EPA+DHA intake. This is consistent with a previous prospective cohort study finding.14 Gaskins et al. showed that, among couples attempting natural pregnancy, higher male (but also female) total fish intake is associated with a shorter time to pregnancy14, suggesting a male association independent of female. However, additional studies with larger sample size, including randomized trials testing the effect of interventions designed based on findings from observational studies like this one, are needed to draw firm conclusions on this issue.

Strengths/limitations

Our study has some limitations. First, we only assessed diet at baseline and therefore we did not document changes in diet over the study period. Second, very few participants consumed fish or nuts more than once daily. Nevertheless, intake of these foods was comparable to that in the US general population,36,37 suggesting this limitation may not hamper generalizability. Another limitation is the observational nature of the study, which limits our ability to interpret the observed associations as causal despite statistical adjustment for a large number of known and potential confounders. Last, the study population comprised couples undergoing infertility treatment and therefore our results may not be generalizable to couples attempting conception without medical assistance. Nevertheless, the study population closely resembles the demographic characteristics of couples undergoing infertility treatment in the United States suggesting that generalizability to couples undergoing infertility treatment may be valid. The principal strength of the study is its prospective design, limiting the possibility or reserve causation, and the use of a previously validated FFQ. Additional strengths include complete follow-up of clinical ART outcomes, and a standardized assessment of a wide variety of participant personal, anthropometric, medical, and lifestyle factors.

Conclusions

Results from this observational study suggest that women’s intake of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids may improve couple’s fertility among couples attempting conception with medical assistance, providing additional evidence that diet may be an important modulator of human fertility.38,39 Moreover, these findings provide additional evidence that men’s diet may influence semen quality parameters, but that this association does not imply improved fertility in the setting of ART.

Supplementary Material

AJOG at a Glance.

A. Why was this study conducted?

Despite evidence suggesting that men’s and women’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich foods (nuts and fish) may have a positive influence couples’ fertility, studies simultaneously considering intakes of both prospective parents on fertility are scant.

B. What are the key findings?

We found that women’s consumption of omega-3 fatty acids and omega-3 rich-foods may improve the probability of live birth by decreasing the risk of pregnancy loss. In addition, men’s intake of omega-3 fatty acids may influence semen quality.

C. What does this study add to what is already known?

To our knowledge, this is the first study to date examining the association of men’s and women’s intake omega-3 fatty acids and their primary food sources with couples’ assisted reproductive technologies (ART) outcomes and men’s semen quality parameters in the same cohort of participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge all members of the EARTH study team and extend a special thanks to all the study participants.

Study funding:

The project was funded by NIH grants R01-ES009718 and P30-DK046200. Albert Salas-Huetos acknowledges support from Ministry of Science and Innovation (Spain) under de project IJC2019-039615-I. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest: The authors report no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chiu Y-H, Chavarro JE, Souter I. Diet and female fertility: doctor, what should I eat? Fertil Steril. 2018;110(4):560–569. doi: 10.1016/J.FERTNSTERT.2018.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Falsig A, Gleerup C, Knudsen U. The influence of omega-3 fatty acids on semen quality markers: a systematic PRISMA review. Andrology. 2019;7(6):794–803. doi: 10.1111/andr.12649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salas-Huetos A, Rosique-Esteban N, Becerra-Tomás N, Vizmanos B, Bulló M, Salas-Salvadó J. The Effect of Nutrients and Dietary Supplements on Sperm Quality Parameters: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Adv Nutr An Int Rev J. 2018;9(6):833–848. doi: 10.1093/advances/nmy057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wise LA, Wesselink AK, Tucker KL, et al. Dietary Fat Intake and Fecundability in 2 Preconception Cohort Studies. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(1):60–74. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiu YH, Karmon AE, Gaskins AJ, et al. Serum omega-3 fatty acids and treatment outcomes among women undergoing assisted reproduction. Hum Reprod. 2018;33(1):156–165. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dex335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nassan FL, Chiu YH, JC V, et al. Intake of protein-rich foods in relation to outcomes of infertility treatment with assisted reproductive technologies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108:1104–1112. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Attaman JA, Toth TL, Furtado J, Campos H, Hauser R, Chavarro JE. Dietary fat and semen quality among men attending a fertility clinic. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(5):1466–1474. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eslamian G, Amirjannati N, Rashidkhani B, Sadeghi MR, Baghestani AR, Hekmatdoost A. Dietary fatty acid intakes and asthenozoospermia: A case-control study. Fertil Steril. 2015;103(1):190–198. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Afeiche M, Gaskins A, Williams P, et al. Processed meat intake is unfavorably and fish intake favorably associated with semen quality indicators among men attending a Fertility Clinic. J Nutr. 2014;144(17):1091–1098. doi: 10.3945/jn.113.190173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen TK, Priskorn L, Holmboe SA, et al. Associations of Fish Oil Supplement Use With Testicular Function in Young Men. Jama Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919462. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salas-Huetos A, Moraleda R, Giardina S, et al. Effect of nut consumption on semen quality and functionality in healthy men consuming a Western-style diet: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018;108(5):953–962. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/nqy181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robbins WA, Xun L, FitzGerald LZ, Esguerra S, Henning SM, Carpenter CL. Walnuts improve semen quality in men consuming a Western-style diet: randomized control dietary intervention trial. Biol Reprod. 2012;87(4):1–8. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.112.101634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xia W, Chiu Y, Williams P, et al. Men’s meat intake and treatment outcomes among couples undergoing assisted reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2015;104(4):972–979. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.06.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaskins AJ, Sundaram R, Louis GMB, Chavarro JE. Seafood Intake, Sexual Activity, and Time to Pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(7):2680–2688. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Messerlian C, Williams PL, Ford JB, et al. The Environment and Reproductive Health (EARTH) Study: a prospective preconception cohort. Hum Reprod Open. 2018;2:hoy001. doi: 10.1093/hropen/hoy001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rimm EB, Giovannucci EL, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Litin LB, Willett WC. Reproducibility and validity of an expanded self-administered semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire among male health professionals. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(10):1114–1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, et al. Validity of a Dietary Questionnaire Assessed by Comparison With Multiple Weighed Dietary Records or 24-Hour Recalls. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;185(7):570–584. doi: 10.1093/aje/kww104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuan C, Spiegelman D, Rimm EB, et al. Relative Validity of Nutrient Intakes Assessed by Questionnaire, 24-Hour Recalls, and Diet Records as Compared with Urinary Recovery and Plasma Concentration Biomarkers: Findings for Women. Am J Epidemiol. 2018;187(5):1051–1063. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwx328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Agriculture. Nutrient Data Laboratory. USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference. USDA. Published online 2016:Release 28. Accessed July 13, 2021. http://www.ars.usda.gov/nea/bhnrc/mafcl

- 20.Gaskins AJ, Colaci DS, Mendiola J, Swan SH, Chavarro JE. Dietary patterns and semen quality in young men. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(10):2899–2907. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mínguez-Alarcón L, Williams PL, Chiu YH, et al. Secular trends in semen parameters among men attending a fertility center between 2000 and 2017: Identifying potential predictors. Environ Int. 2018;121(October):1297–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.10.052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. WHO Laboratory Manual for the Examination and Processing of Human Semen. Vol 5th ed. World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kruger TF, Acosta AA, Simmons KF, Swanson RJ, Matta JF, Oehninger S. Predictive value of abnormal sperm morphology in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1988;49(1):112–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Willett WC. Nutritional Epidemiology. 3rd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199754038.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gaskins AJ, Afeiche MC, Hauser R, et al. Paternal physical and sedentary activities in relation to semen quality and reproductive outcomes among couples from a fertility center. Hum Reprod. 2014;29(11):2575–2582. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deu212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun B, Messerlian C, Sun Z, et al. Physical activity and sedentary time in relation to semen quality in healthy men screened as potential sperm donors. Hum Reprod. 2019;34(12):2330–2339. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gaskins AJ, Mendiola J, Afeiche M, Jørgensen N, Swan SH, Chavarro JE. Physical activity and television watching in relation to semen quality in young men. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(4):265–270. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2012-091644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gaskins AJ, Williams PL, Keller MG, et al. Maternal physical and sedentary activities in relation to reproductive outcomes following IVF. Reprod Biomed Online. 2016;33(4):513–521. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2016.07.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stanhiser J, Jukic AMZ, Steiner AZ. Serum omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acid concentrations and natural fertility. Hum Reprod. 2020;35(4):950–957. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nehra D, Le HD, Fallon EM, et al. Prolonging the female reproductive lifespan and improving egg quality with dietary omega-3 fatty acids. Aging Cell. 2012;11(6):1046–1054. doi: 10.1111/acel.12006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stoffel W, Schmidt-Soltau I, Binczek E, Thomas A, Thevis M, Wegner I. Dietary ω3-and ω6-Polyunsaturated fatty acids reconstitute fertility of Juvenile and adult Fads2-Deficient mice. Mol Metab. 2020;36(March):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2020.100974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hammiche F, Vujkovic M, Wijburg W, et al. Increased preconception omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid intake improves embryo morphology. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(5):1820–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.11.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lefevre M, Lovejoy JC, Smith SR, et al. Comparison of the acute response to meals enriched with cis- or trans-fatty acids on glucose and lipids in overweight individuals with differing FABP2 genotypes. Metabolism. 2005;54(12):1652–1658. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ros E. Health benefits of nut consumption. Nutrients. 2010;2(7):652–682. doi: 10.3390/nu2070652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitsunami M, Salas-Huetos A, Minguez-Alarcon L, et al. Men’s dietary patterns in relation to infertility treatment outcomes among couples undergoing in vitro fertilization. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2021;In Press. doi: 10.1007/s10815-021-02251-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeng L, Ms MR, Liu J, et al. Trends in Processed Meat, Unprocessed Red Meat, Poultry, and Fish Consumption in the United States, 1999–2016. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(7):1085–1098.e12. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2019.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim H, Caulfield LE, Rebholz CM, Ramsing R, Id EN. Trends in types of protein in US adolescents and children: Results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2010. PLoS One. 2020;15(3):e0230686. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gaskins AJ, Chavarro JE. Diet and fertility: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;218(4):379–389. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salas-Huetos A, Bulló M, Salas-Salvadó J. Dietary patterns, foods and nutrients in male fertility parameters and fecundability: a systematic review of observational studies. Hum Reprod Update. 2017;23(4):371–389. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmx006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.