Abstract

Suppression subtractive hybridization, a cost-effective approach for targeting unique DNA, was used to identify a 41.7-kb Yersinia pestis-specific region. One primer pair designed from this region amplified PCR products from natural isolates of Y. pestis and produced no false positives for near neighbors, an important criterion for unambiguous bacterial identification.

In an infectious disease outbreak, rapid and highly specific identification of putative pathogens is necessary to eliminate confusion with nonpathogenic but closely related organisms. Rapid diagnostic protocols have been developed previously based on real-time PCR amplification of nucleotide sequences unique to various organisms (3). This approach requires development of highly specific oligonucleotide primers for bacteria such as Yersinia pestis, the causative agent of bubonic plague. Strains of Y. pestis have been classified into three biovars, Y. pestis bv. antiqua, Y. pestis bv. mediaevalis, and Y. pestis bv. orientalis, based on biochemical tests. Y. pestis is considered a recently emerged clone that arose from Yersinia pseudotuberculosis 1,500 to 20,000 years ago (1); Y. pestis bv. orientalis is considered the most recently emerged biovar (5), and it includes all of the strains isolated so far in the United States. Y. pseudotuberculosis, an enteric pathogen, exhibits more than 90% DNA-DNA homology with Y. pestis and is commonly found in environmental samples (4). Therefore, large stretches of nucleotide similarity make many candidate sequences unsuitable for Y. pestis identification, as they create false-positive amplification products with Y. pseudotuberculosis.

Genomic plasticity in many bacteria (including Y. pestis) results from large genomic differences, which are assumed to have arisen from the lateral gene transfer events that commonly originate from mobile genetic elements, such as transposons or insertion elements, or bacteriophage integration (13, 15; L. Radnedge, unpublished data). Suppression subtractive hybridization (SSH) identifies regions of DNA present in one species, designated the tester (e.g., Y. pestis), but absent in another species, designated the driver (e.g., Y. pseudotuberculosis) (6). SSH has the advantage of requiring only small amounts of genomic DNA, is applicable to any genome (even an uncharacterized genome), and identifies the large genomic differences typically found between bacterial genomes.

Here we describe identification of seven difference products specific to Y. pestis, four of which map to a 41.7-kb region that is flanked by two 31-bp direct repeats. Four primer pairs were designed from this region, and one of these primer pairs amplified a PCR product from all of the Y. pestis DNAs tested. All four primer pairs were absent from Y. pseudotuberculosis, failed to cross-react with a collection of DNAs from bacterial, viral, and mammalian sources, and thus are highly specific for the target organism, Y. pestis.

Isolation of nucleotide sequences specific to Y. pestis

DNA sequences unique to Y. pestis were identified by SSH by using Y. pestis as the tester and Y. pseudotuberculosis ATCC 29833 as the driver (Table 1). DNAs from clones containing putative tester-specific difference products were purified (16) and sequenced, and the resulting data were analyzed by using ABI Sequencing Analysis software (version 3.2) and then assembled and edited by using Phred, Phrap, and Consed 7.0 (7, 8). Oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) were designed by using the putative tester-specific sequences and had melting temperatures of more than 60°C. To determine whether a primer pair was tester specific, 75 pg of the tester DNA (Y. pestis DNA) and 75 pg of the driver DNA (Y. pseudotuberculosis DNA) were used as templates in PCRs (94°C for 15 s, 65°C for 15 s, and 72°C for 30 s for 27 cycles). If a PCR product was amplified from the tester DNA and not from the driver DNA, the sequence was designated tester specific. A positive control experiment to test the integrity of the genomic DNA template was performed by using primers specific for a region of the 23S rRNA gene.

TABLE 1.

Y. pestis-specific difference products

| Difference product | Difference product size (bp) | Testera | Tester biovarb | Forward primerc | Reverse primerc | Size of PCR product (bp)d | CO92 left coordinatee | CO92 right coordinatee | GenBank accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,006 | KIM D27 | M | GGCTGACCCATCCGCAGTCC | CTGAGTAACTGCGTCACCCCATC | 531 | 412,192 | 413,196 | AF350073 |

| 2 | 941 | CO92 | O | TTCAAGTGCTCAAAGCACTGCG | TGGGAAATAGCCCGCGTAAATG | 300 | 1,899,755 | 1,900,695 | AF350074 |

| 3a | 882 | KIM D46 | M | TGTAGCCGCTAAGCACTACCATCC | GGCAACAGCTCAACACCTTTGG | 276 | 2,366,982 | 2,367,863 | AF350075 |

| 3b | 837 | KIM D46 | M | GCATGACCGAAACGTCATCCTG | GGATACTTCGCGCATATCTTGCC | 332 | 2,375,224 | 2,376,080 | AF350076 |

| 3c | 517 | D15 | A | GGATAACGTTGCAGCAGCTTCG | CCTTCGCCACCTTCACCTGC | 250 | 2,380,322 | 2,380,838 | AF350077 |

| 3d | 1,109 | KIM D46 | M | TCCAAAATCGGAGAATTACTATGGGC | CGTTGTTGATGCCGTCACTTTG | 226 | 2,384,570 | 2,385,677 | AF350078 |

| 4 | 1,123 | KIM D27 | M | GCCACTGTAGTAGTCGATGCGATG | TTGGCAAACGGAATATCGCAG | 268 | 3,841,793 | 3,842,915 | AF350079 |

The tester DNAs were prepared from Y. pestis KIM D27, KIM D46, D15 Yokohama, and CO92.

M, Y. pestis bv. mediaevalis; O, Y. pestis bv. orientalis; A, Y. pestis bv. antiqua.

Primers specific for difference products.

Predicted sizes of the PCR products.

Locations on the Y. pestis CO92 genome, given as the coordinates of the sequence available at http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/Y_pestis.

An initial BLAST sequence analysis (2) demonstrated that 35 of 81 of the difference products exhibited similarity to plasmids unique to Y. pestis (11) (data not shown). These sequences were discarded since ideal diagnostic oligonucleotide primers should anneal to chromosomal DNA sequences, thus circumventing the variability in plasmid profiles among strains of Y. pestis (10). Of the remaining 46 chromosomal difference products, 39 were not tester specific and were discarded. Seven chromosomal difference products were found to be tester specific and were mapped to the genome sequence of Y. pestis CO92 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/Y_pestis) (Table 1). Four of the seven tester-specific difference products mapped to a single large difference region within 19 kb of each other on the Y. pestis CO92 genome.

Characterization of the large difference region.

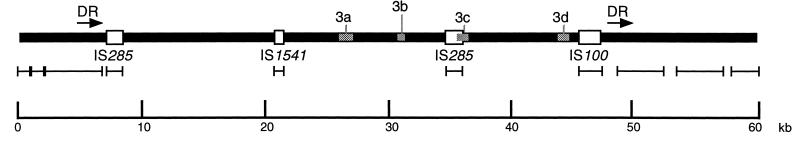

In order to determine the boundaries of the large difference region present in Y. pestis, the sequence of this region was compared to preliminary genome sequence data for Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 (http://bbrp.llnl.gov/bbrp/bin/y.pseudotuberculosis _blast). A 60-kb nucleotide region from Y. pestis CO92 containing the four difference products was searched against the IP32953 database, and regions of significant similarity are shown in Fig. 1. BLAST analysis of this region revealed localized sequence similarity to two copies of IS285, one copy of IS1541, and one copy of IS100, insertion elements commonly found in Yersinia species (9, 14). The remaining nucleotide similarities between the two species were limited to sequences flanking the 41.7-kb region absent from Y. pseudotuberculosis IP32953 that contains the four difference products (Fig. 1). The presence of two 31-bp direct repeats in Y. pestis CO92 was also noted and appeared to correlate with the discontinuation of sequence similarity in the two species; this 31 bp region occurs only once in the Y. pseudotuberculosis genome. Two oligonucleotide primers designed to span the putative junction of the deletion generated the 223-bp amplification product from all Y. pseudotuberculosis DNAs tested that would be predicted if a single direct repeat were present (Table 2; Fig. 2). It is possible that the 41.7-kb region was inserted into the Y. pseudotuberculosis genome by integration of a prophage sequence containing a copy of the 31-bp sequence and that this occurred early in the evolution of Y. pestis from Y. pseudotuberculosis.

FIG. 1.

Graphic representation of the 41.7-kb difference region. Four insertion sequences (open boxes) and four difference products (gray boxes) are distributed along the Y. pestis CO92 sequence (thick black line). The sequence similarity regions of Y. pseudotuberculosis (thin black lines) occur outside the 41.7-kb region, except for localized regions of identity to the insertion sequences. Two 31-bp direct repeats (DR) (arrows) are located at the proposed boundaries of the difference region.

TABLE 2.

Amplification of PCR products with different primers

| Strain | Biotypea | Amplification with:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23S rRNA primersb | 3a primers | 3b primers | 3c primers | 3d primers | JS primersc | ||

| ATCC 29833 | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| ATCC 6902 | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| B16 | 1 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| ATCC 29910 | 2 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| ATCC 6904 | 2 | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| A16 | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| D15 Yokohama | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| D94 Kuma | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Yeo154 Yokohama | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Angola | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Pestoides F | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Pestoides E | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Pestoides G | A | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Pestoides A | M | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pestoides B | M | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pestoides C | M | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Pestoides D | M | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Harbin 35 | M | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Nicholisk 41 | M | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 366 Yemen | M | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| D1 Iran | M | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| KIM D27 | M | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 15–19 Russia | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 195P | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 770 CO3311 | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 90A 0414 | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| CO92 | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| D20 Dodson | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| H3 | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| D14 Salazar | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 586 Exu#9 | O | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| 316 | ? | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Pestoides J | ? | + | + | + | + | + | − |

DNAs from a collection of natural isolates of Y. pestis representing all three biovars (A, Y. pestis bv. antiqua; M, Y. pestis bv. mediaevalis; O, Y. pestis bv. orientalis) and two undescribed biovars (?) and DNAs from Y. pseudotuberculosis serogroup 1 and 2 strains were used as templates.

The 23S rRNA primers (forward primer 5′CTACCTTAGGACCGTTATAGTTAC3′ and reverse primer 5′GAAGGAACTAGGCAAAATGGT3′) were used as positive controls.

The JS primers (forward primer 5′GCAGCTTAGGCTGTCATCG3′ and reverse primer 5′CTATCGCCTGATTGGAGAGG3′) spanned the junction of the deleted 41.7-kb region.

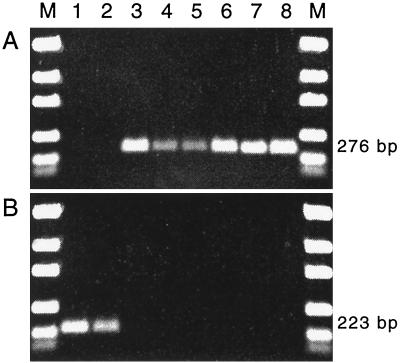

FIG. 2.

PCR products amplified by using template DNAs from representative isolates of Y. pestis representing all three biovars and Y. pseudotuberculosis. (A) Lane M contained a DNA size marker (1,200, 800, 400, 200, and 100 bp). A 276-bp product was amplified from the following templates by using primer pair 3a: Y. pseudotuberculosis ATCC 29833 (type strain, group I) (lane 1), Y. pseudotuberculosis ATCC 6904 (group II) (lane 2), Y. pestis bv. antiqua D15 Yokohama (lane 3), Y. pestis bv. antiqua Angola (lane 4), Y. pestis bv. mediaevalis KIM D27 (lane 5), Y. pestis bv. mediaevalis Pestoides A (lane 6), Y. pestis bv. orientalis D14 Salazar (lane 7), and Y. pestis bv. orientalis CO92 (lane 8). (B) PCR products amplified by using the same templates as those used for panel A, but a 223-bp product was amplified by using the JS primers.

Open reading frame (ORF) analysis of the large difference region revealed 34 putative ORFs, which were searched against the nonredundant GenBank database by using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html). Similarities to four insertion elements, nine novel ORFs, and 28 putative ORFs that appeared to be of phage origin were noted (http://bbrp.llnl.gov/html/YPspc.html). Even within this region there is evidence of previous DNA insertions; two ORFs interrupt the bglH homolog, and IS285 interrupts the terminase of phage BP-933W. Many homologs of genes in the cryptic prophages of Escherichia coli O157:H7 were noted (15). The G+C content of the large difference region (47.2%) was not significantly different from that of Y. pestis CO92 (47.6%).

The three remaining difference products map to different locations on the Y. pestis CO92 genome. BLAST analysis of difference product 1 revealed no similarity to previously characterized sequences, while difference product 2 exhibited weak similarity to a family of probable translation inhibitors. BLASTX analysis of difference product 4 against the nonredundant database revealed 80% identity to intB prophage P4 integrase, which has been implicated in the mobility of restriction-modification systems of the Enterobacteriaceae (12).

Design and validation of species-specific oligonucleotide probes.

Unambiguous pathogen identification requires diagnostic primers that are extremely specific and do not cross-react with close relatives or DNAs that might be present in environmental samples. In order to determine the suitability of the four primer pairs from the large difference region as diagnostic probes, they were validated in PCRs by using DNAs from a wide collection of bacterial, viral, and mammalian sources. The collection included bacteria and viruses whose disease manifestations are similar to the disease manifestations of bubonic plague or that represent potential contamination of reservoirs of the disease. The DNA collection tested comprised Y. pseudotuberculosis, Yersinia enterocolitica, Bacillus cereus, Bacillus subtilis, Bacillus thuringiensis, Staphylococcus aureus, Listeria monocytogenes, Haemophilus influenzae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Borrelia burgdorferi, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Escherichia coli, influenza A virus (H3, H7), influenza B virus, respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, poliovirus, Drosophila, cow, rat, dog, rabbit, pig, chicken, and human DNAs. Each primer set produced a single amplification product when Y. pestis DNA was used as the template, and no products were amplified with any other nucleic acid (data not shown). No primers matched nonspecific target sites when the sequences were checked against the GenBank nonredundant DNA database.

The presence of each difference product was visualized on a 1% agarose gel (Fig. 2) and was verified with a collection of natural isolates of Y. pestis representing all three biovars (Table 2). All four primer pairs amplified products from all of the Y. pestis bv. orientalis strains tested, and one primer pair (primer pair 3a) amplified products from all of the strains tested. The four strains that did not yield a PCR product with all four primers (strains Pestoides A to Pestoides D) (Table 2) are strains that apparently are more closely related to Y. pseudotuberculosis (Radnedge, unpublished data). It is likely that localized sequence differences prevented primer annealing, resulting in PCR failure. It is also feasible that the sizes of the difference region are different in these strains. However, no PCR product was obtained with the oligonucleotide primers designed to span the putative deletion point (JS primers), indicating that an insertion of sufficient size to prevent amplification was present (Table 2). The size and organization of the large difference region in strains Pestoides A to Pestoides D remain to be determined. Future work will determine the role of this 41.7-kb difference region in the pathogenicity and survival of Y. pestis.

Summary.

We identified a 41.7-kb region of the Y. pestis genome that is absent in Y. pseudotuberculosis. This region exhibits similarity to putative phage genes, many of which are found in E. coli O157:H7. Primer pairs designed by using this region are highly specific for Y. pestis, and primer pair 3a amplifies PCR products from all biovars. None of the primers produced false positives for near neighbors, an important criterion for unambiguous identification. Our experiments show that SSH is a cost-effective approach for targeting unique DNA that can be used for highly specific bacterial identification.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The nucleotide sequences of the seven tester-specific difference products have been deposited in the GenBank database under accession no. AF350073 to AF350079.

Acknowledgments

This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by the University of California Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory under contract W-7405-Eng-48 and was funded by the Department of Energy NN-20 Chemical and Biological Non-Proliferation Program.

We appreciate the technical assistance of Julie Avila, Aubree Hubbell, Madison Macht, and Jessica Wollard. We gratefully acknowledge the provision of Y. pestis strains by R. R. Brubaker.

REFERENCES

- 1.Achtman M, Zurth K, Morelli G, Torrea G, Guiyoule A, Carniel E. Yersinia pestis, the cause of plague, is a recently emerged clone of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14043–14048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.24.14043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschul S F, Madden T L, Schäffer A A, Zhang J, Zhang Z, Miller W, Lipman D J. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belgrader P, Benett W, Hadley D, Richards J, Stratton P, Mariella R, Jr, Milanovich F. PCR detection of bacteria in seven minutes. Science. 1999;284:449–450. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bercovier H, Mollaret H H, Alonso J M, Brault J, Fanning G R, Steigerwalt A G, Brenner D J. Intra- and interspecies relatedness of Yersinia pestis by DNA hybridization and its relationship to Y. pseudotuberculosis. Curr Microbiol. 1980;4:225–229. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buchrieser C, Rusniok C, Frangeul L, Couve E, Billault A, Kunst F, Carniel E, Glaser P. The 102-kilobase pgm locus of Yersinia pestis: sequence analysis and comparison of selected regions among different Yersinia pestis and Yersinia pseudotuberculosis strains. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4851–4861. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4851-4861.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diatchenko L, Lau Y F, Campbell A P, Chenchik A, Moqadam F, Huang B, Lukyanov S, Lukyanov K, Gurskaya N, Sverdlov E D, Siebert P D. Suppression subtractive hybridization: a method for generating differentially regulated or tissue-specific cDNA probes and libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6025–6030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.6025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ewing B, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ewing B, Hillier L, Wendl M C, Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. I. Accuracy assessment. Genome Res. 1998;8:175–185. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.3.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filippov A A, Oleinikov P V, Motin V L, Protsenko O A, Smirnov G B. Sequencing of two Yersinia pestis IS elements, IS285 and IS100. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1995;13:306–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Filippov A A, Solodovnikov N S, Kookleva L M, Protsenko O A. Plasmid content in Yersinia pestis strains of different origin. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;55:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(90)90165-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu P, Elliott J, McCready P, Skowronski E, Garnes J, Kobayashi A, Brubaker R R, Garcia E. Structural organization of virulence-associated plasmids of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:5192–5202. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.19.5192-5202.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee K F, Shaw P C, Picone S J, Wilson G G, Lunnen K D. Sequence comparison of the EcoHK31I and EaeI restriction-modification systems suggests an intergenic transfer of genetic material. Biol Chem. 1998;379:437–441. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.4-5.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ochman H, Lawrence J G, Groisman E A. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation. Nature. 2000;405:299–304. doi: 10.1038/35012500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Odaert M, Devalckenaere A, Trieu-Cuot P, Simonet M. Molecular characterization of IS1541 insertions in the genome of Yersinia pestis. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:178–181. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.1.178-181.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perna N T, Plunkett G, Burland V, Mau R, Glasner J D, Rose D J, Mayhew G F, Evans P S, Gregor J, Kirkpatrick H A, Pósfai G, Hackett J, Klink S, Boutin A, Shao Y, Milller L, Grotbeck E J, Davis N W, Lim A, Dimalanta E T, Potamousis K D, Apodaca J, Anantharaman T S, Lin J, Yen G, Schwartz D C, Welch R A, Blattner F R. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature. 2001;409:529–533. doi: 10.1038/35054089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skowronski E W, Armstrong N, Andersen G, Macht M, McCready P M. Magnetic microplate-format plasmid isolation protocol for high-yield, sequencing grade DNA. BioTechniques. 2000;29:786–790. doi: 10.2144/00294st05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]