Abstract

Purpose:

To report on the safety of the first five cohorts of a gene therapy trial using recombinant equine infectious anemia virus expressing ABCA4 (EIAV-ABCA4) in adults with Stargardt Dystrophy (SD) due to mutations in ABCA4.

Design:

Nonrandomized multicenter phase I/IIa clinical trial.

Methods:

Patients received a subretinal injection of EIAVABCA4 in the worse-seeing eye at three dose levels and were followed for three years after treatment.

Main Outcome Measures:

The primary end point was ocular and systemic adverse events. The secondary endpoints were best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA), static perimetry (SP), kinetic perimetry (KP), total field hill of vision (VTOT), full field electroretinogram (ffERG), multifocal ERG (mfERG), color fundus photography (CFP), short-wavelength fundus autofluorescence (FAF), and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT).

Results:

The subretinal injections were well-tolerated by all 22 patients across three dose levels. There was one case of a treatment-related ophthalmic serious adverse event in the form of chronic ocular hypertension. The most common adverse events were associated with the surgical procedure. In one patient treated with the highest dose, there was a significant decline in the number of macular flecks as compared to the untreated eye. However, in six patients hypoautofluorescent changes were worse in the treated eye than the untreated eye. Of these, one patient had retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) atrophy that was characteristic of tissue damage likely associated with bleb induction. No patients had any clinically significant changes in BCVA, SP, KP, VTOT, ffERG, or mfERG attributable to the treatment.

Conclusions:

Subretinal treatment with EIAV-ABCA4 was well tolerated with only one case of ocular hypertension. No clinically significant changes in visual function tests were found to be attributable to the treatment. However, 27% of treated eyes showed exacerbation of RPE atrophy on FAF. There was significant reduction in macular flecks in one treated eye from the highest dose cohort. Additional follow-up and continued investigation in more patients will be required to fully characterize the safety and efficacy of EIAV-ABCA4.

Table of Content:

The purpose of the study was to investigate safety of the first gene therapy (EIAV-ABCA4) in patients with ABCA4-associated Stargardt disease. This study shows subretinal treatment with EIAV -ABCA4 was well tolerated. No clinically significant changes in visual function tests were found to be attributable to the treatment. About 1/3 of participants showed exacerbation of RPE atrophy in treated eyes. Continued investigation in more patients is required to fully characterize safety and efficacy.

Introduction

ABCA4-related retinopathy (OMIM #248200), results from biallelic mutations in ABCA4 and causes a spectrum of retinal phenotypes including, fundus flavimaculatus, juvenile onset macular dystrophy, cone-rod dystrophy with or without foveal sparing, and in the most severe cases, generalized rod-cone dystrophy1,2. The juvenile form of the disease as well as its variants are often referred to collectively as Stargardt disease (SD). ABCA4-related retinopathy is an autosomal recessive disease, although cases of pseudodominance have been reported, and additionally, several genes can cause a dominant Stargardt-like phenotype3,4. Although a rare disease, SD is one of the most common inherited retinal dystrophies, affecting approximately one in 8,000 to 10,000 persons worldwide3.

The disease affects both sexes and presents with a tri-modal distribution of onset peaking at 7, 23, and 55 years of age5,6. Juvenile cases present with rapid, progressive loss of central visual acuity, but the rate of disease progression and clinical severity are related to the age of disease onset and specific mutations5-10. Consequent to the central vision loss, most participants also have impaired color vision and may experience photophobia11,12. In some SD patients, a delay in dark adaptation may also be detected6,7. Ophthalmic exam in patients with SD typically reveals atrophic macular lesions with or without the presence of pisciform yellow flecks at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). In histopathologic examinations of SD patients’ eyes, the fleck lesions have been correlated with RPE cells densely packed with lipofuscin13. Classically, fluorescein angiography, if performed, demonstrates a “dark choroid,” as where choroidal fluorescence is blocked by the accumulation of lipofuscin. In most cases, peripheral vision is unaffected but can be impaired in the later stages of the disease.

The ABCA4 gene contains 50 exons and encodes ATP- ATP-binding cassette, sub-family A (ABC1), member 4, a ~250 kDa single chain glycoprotein, which is localized on the disk margins of the vertebrate photoreceptor (PR) outer segments, and belongs to the ABC transporter superfamily14. It has been proposed that ABCA4 participates in the clearance of all-transretinal and its Schiff-base conjugate, N-retinylidene phosphatidylethanolamine (N-retinylidene-PE), intermediates in the formation of A2E from the PRs8. Although many published biochemical and animal model studies suggest that the natural substrate of ABCA4 protein is N-retinylidene-PE, which spontaneously forms as an all-transretinol adduct following the process of light absorption by rhodopsin16, the exact mechanism of ABCA4 function is not fully understood15. Reported mutations range from single missense changes, which are by far the most common, to more complex gene rearrangements14. In terms of ABCA4 protein function, the effects of these mutations range from a total loss of function due to the absence of the protein to production of protein with functionally impaired transporter activity.

There are currently no approved therapies for SD. The characterization of the molecular basis of SD has opened the door to a therapeutic approach based on gene augmentation. The eye is ideally suited as a target organ for this type of therapy, as it is anatomically separated from the rest of the body, is easy to access, and allows noninvasive diagnostic follow-up of the therapeutic effects in vivo. Moreover, the eye is immune privileged, which is an active process of immune deviation in specific anatomical compartments such as the anterior chamber and subretinal space17. These properties along with the relatively low vector dosage requirement within the small compartmentalized space of the subretinal bleb are advantages for limiting immune reactions to gene therapy.

The viral vector used in this investigational product EIAV-ABCA4 (SAR422459) is a non-replicating, integrating, recombinant lentiviral vector based on the equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV), which is nonpathogenic to humans and has been developed as a vector for therapeutic gene delivery18. Subretinal delivery of the investigational product aims to introduce a copy of the normal coding sequence of the human ABCA4 cDNA into the host genome using the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promotor to drive expression of normal ABCA4 protein10-14. The EIAV lentiviral vector was pseudotyped with VSV-G envelope protein to allow efficient transduction of the PRs. Reporter gene studies in mice using EIAV based vectors have demonstrated that expression of the gene product persists for at least 16 months in the mouse eye and greater than four years in humans after a single administration19-20. Following subretinal injection of EIAV-ABCA4, cellular transduction is limited to the RPE cells and PR and to a lesser extent other cells of the inner neural retina19.

The preclinical safety evaluation program of the EIAV vector assessed the pharmacological, pharmacokinetic, and toxicological profiles in mice, rabbits and non-human primates (NHPs)19,21,22. In these studies, EIAV-ABCA4 or homologous lentiviral vectors expressing reporter proteins were given by subretinal administration. Despite prior evidence of low lentiviral transduction efficiency of PRs, both of the preclinical studies for this clinical trial showed that EIAV-ABCA4 had good potential19,21. Subretinal delivery of EIAV-ABCA4 in neonatal (P4-5) Abca4−/− mice resulted in expression of the ABCA4 protein from two weeks after treatment and maintained until the end of the study at two months, which correlated with a reduction in A2E accumulation (the levels at 12 months were similar to wildtype)19.. Thus, this study demonstrated that EIAV-ABCA4 was capable of transducing photoreceptor neonatal progenitor cells in a meaningful and sustainable manner. Furthermore, reporter gene expression using EIAV-GFP was detected in NHP PRs and RPE, however this was performed at 1-2 log units higher concentration and absolute dose than the EIAV-ABCA4 dose used in the preclinical studies21. The maximum concentration and dose levels for EIAV-ABCA4 in this clinical trial were comparable and established empirically from EIAV-ABCA4 used in NHPs on the basis of the scale of the eye and the historical experience of introducing suspensions into the eye21. No agent-related toxicity was noted in any of these preclinical studies.

The current study reports available three-year results of cohorts 1-5 of an open label phase I/IIa dose escalation safety study of subretinally injected EIAV-ABCA in participants with SD (www.clinicaltrials.gov, NCT01367444). Data from additional confirmatory cohorts 6-7 are not included in this manuscript due to incomplete follow-up period and will be the subject of a subsequent publication.

Materials and Methods

Twenty-two participants were recruited from two sites (Oregon Health & Science University, Casey Eye Institute, Portland, Oregon, USA and Centre Hospitalier National d’Ophtalmologie des Quinze-Vingts, Paris, France). The trial conformed to the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants and was approved by the Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Comité de Protection des Personnes Paris Ile de France V, and Regulatory Agencies (FDA and ANSM/HCB). Informed written consent was obtained from all of the participants in the study prior to the conduct of any study procedures. Summary of the enrolled participants, genetic mutation, and pre-treatment mean BCVA is shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Study Design

In the multicenter study TDU13583 (ClinicalTrial.gov identifier: NCT01367444), three doses of EIAV-ABCA4 were evaluated over seven cohorts, followed for 48 weeks, and then enrolled into the long-term study, LTS13588 (NCT01736592), which follows participants for 15 years. A minimum follow-up period of three years was required for inclusion in this interim report, which is comprised of patients from the first five cohorts. Cohorts one to four represent the dose escalation phase of the study and consisted of four participants each. Cohort five consisted of six participants, who were treated with the maximum tolerated dose. The main inclusion criteria for all participants enrolled in this study were: age equal to or greater than 18 and moderate to severe SD with biallelic pathogenic mutations in ABCA4 confirmed by direct sequencing and co-segregation analysis. Additional inclusion criteria for cohorts 1-5 were classified according to Lois et al23 (Table 1):

Table 1.

Dose escalation by cohort. TU, transduction units.

| Cohort | Group | No. Of Pts. | Dose Level | Dose by target strength (TU/eye) |

Volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | 4 | 1:10 | 1.8 x 105 TU | 300uL |

| 2 | B | 4 | 1:10 | 1.8 x 105 TU | 300uL |

| 3 | B | 4 | 1:3 | 6 x 105 TU | 300uL |

| 4 | B | 4 | undiluted | 1.8 x 106 TU | 300uL |

| 5 | C | 6 | undiluted | 1.8 x 106 TU | 300uL |

Group A: BCVA ≤ 20/200 in the worst eye and severe cone-rod dysfunction with no detectable or severely abnormal full field ERG responses.

Group B: BCVA ≤ 20/200 in the worst eye with abnormal full field ERG responses.

Group C: BCVA ≤ 20/100 in the worst eye with abnormal full field ERG responses.

Key exclusion criteria were media haze, aphakia or prior vitrectomy, other diseases affecting visual function (e.g., glaucoma, optic neuropathy, active uveitis, retinopathy and maculopathy other than ABCA4-related retinopathy), myopia greater than eight diopters spherical equivalent, history of ocular surgery within 6 months, and concomitant systemic disease in which the disease itself, or the treatment for the disease, could alter ocular function. Data Safety Monitoring Board evaluation occurred between cohorts.

Vector and IMP

Drug SAR422459 (EIAV-ABCA) is a lentiviral vector system based on the equine infectious anemia virus (EIAV) that was developed and produced for this study by Oxford Biomedica21. SAR422459 is a novel, self-inactivating EIAV vector (EIAV-ABCA4) that encodes the ABCA4 gene, driven by the cytomegalovirus (CMV) constitutive promoter. It is pseudotyped with the Vesicular Stomatitis Virus G protein.

Surgical Procedure and Post-operative Treatment:

One study eye was selected. If both eyes were eligible for the study, the worse-seeing eye, as per investigator’s judgment, was selected to be the study eye. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia or local anesthesia with intravenous sedation according to participant, surgeon, and anesthesiologist preferences. A standard three port vitrectomy was first performed and EIAV-ABCA was administered as a subretinal injection of approximately 300 microliters through a hydraulically created retinotomy. EIAV-ABCA was prepared in sterile conditions with or without dilution as needed for target dose. A retinotomy was recommended to be performed temporal to the optic nerve and anterior to the major superior vascular arcade. Retinal function and structure based on BCVA, perimetry, and imaging were used in the planning of the desired bleb location. Final retinotomy and bleb locations were determined by the surgeon based on operative conditions, and, for some patients, after discussion with the PI at the other site and the reading center. The surgeon was allowed to repeat the retinotomy if subretinal injection did not succeed at the initial site or if the bleb was spreading in an undesired direction. Tamponade was also allowed at the discretion of the surgeon, and air-fluid exchange was performed in five cases.

Peri-Operative regimen

Investigators were permitted made treatment decisions guided by postoperative findings. A combination of topical, peribulbar, or systemic administration of corticosteroids was suggested but left at the discretion of surgeons and investigators. As such, all patients received topical corticosteroids for 2 to 6 weeks. In addition, on the day of surgery, 4 patients received 10 mg of intravenous dexamethasone, 4 patients were given a 10 mg injection of periocular dexamethasone, and 1 patient received both intravenous and periocular corticosteroids (Supplementary Table 2).

Surgery video-recording and intra-operative OCT

Bleb position was recorded by video or intraoperative OCT of the surgical procedure for all participants when possible. The approximate location of the bleb was drawn for all the participants using the surgical video or Retcam images. If the surgical videos or Retcam images were not available, approximate bleb location was identified based on surgical notes.

Laboratory Parameters and Immunological Studies:

Laboratory testing to assess safety, vector biodistribution and any immune responses were performed by collecting blood and urine samples before and after treatment. Standard safety hematology and biochemistry tests as well as urinalysis were done throughout the study and the follow-up period. EIAV-ABCA distribution in the blood (plasma and buffy coat) and urine assessed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Blood was collected and sera were analyzed for EIAV-ABCA -associated antibodies. Presence of antibodies against any putative antigenic component of the EIAV based vector were tested, including: VSV-G2 envelope protein, neomycin phosphotransferase, ABCA4 protein, and p26 protein (EIAV native capsid protein).

Clinical assessments and study endpoints:

Participants were evaluated at screening, baseline, postop Day 1, and postop week 1, 2, 4, 12, 24, 36, 48, year 2, and year 3. Safety and efficacy were assessed for best corrected visual acuity (BCVA), ophthalmic examination, multimodal imaging, full field perimetry, and electroretinography (ERG).

Visual acuity

BCVA was measured using the Early Treatment of Diabetic Retinopathy (ETDRS) chart on the Electronic Visual Acuity Tester (EVA) at a distance of 3 meters and recorded as the number of letters read24. The right eye was tested prior to the left eye. For participants with poor central vision, participants were instructed to fixate eccentrically or turn their head in any manner that improved BCVA. If the participant employed these maneuvers, the technician ensured that the fellow eye remained covered. Participants were also instructed not to lean forward.

Kinetic and Static Perimetry

Static and kinetic perimetry were performed using the Octopus 900 Pro (Haag-Streit International, Koeniz, Switzerland) with EyeSuite software V.2.2.0 and V 2.3.0. Static Perimetry (SP) was performed using the German Adaptive Thresholding Estimation (GATE) algorithm applied to a custom Octopus 900 grid, the ‘STGD 185pt GATE V’, extending from 56° nasally to 80° temporally, with the stimulus size V. The background illumination was 10 cd/m2 (31.4 apostilbs). Volumetric estimate of retinal sensitivity using HOV was calculated using Visual Field Modeling and Analysis (VFMA) software previously reported by Weleber et. al.25_Kinetic Perimetry (KP) was collected using the V4e, III4e, and I4e test targets. Test vectors were presented to the participants approximately every 15°, at an angular velocity of 4°/second, and originating approximately 10° outside the age-correlated normal isopter. Any scotomas (non-seeing areas within seeing areas) were mapped using an angular velocity of 2°/second, using all three targets where possible. There were cases where the blindspot was not possible to map due to large central scotoma/s. The total seeing area is reported in our results and was calculated for each isopter (seeing area minus any defined scotoma/s if any).

Spectral Domain Optical Coherence Tomography (SD-OCT).

Images were obtained of both eyes with the Heidelberg Spectralis SD-OCT system (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany). High speed 97 horizontal line volume scans centered on the fovea were performed at screening and baseline visits within a two to three week interval. High resolution horizontal and vertical line scans were acquired at 30 degree magnification and centered on the fovea. Manual segmentation, based on previously published algorithms, was performed to correct automated segmentation errors for boundaries of the Internal Limiting Membrane (ILM) and Bruch’s Membrane (BM)26,27. For this analysis, the mean central thickness measurements and macular volume were calculated in the macula by using the central 1 mm circular ETDRS grid.

Fundus photography (FP) and autofluorescence (FAF)

In addition to color FP, FAF images were obtained with the Heidelberg Spectralis HRA (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) using the widefield lens to image the retina at 55°, centered and focused on the macular region at a 488 nm excitation wavelength. Some participants had images taken at 30°. FAF images were taken at different settings, which may have resulted in variable image illumination.

Electroretinography

Retinal function was assessed with full field ERG (ffERG) and multifocal ERG (mfERG). Electroretinographic responses were recorded according to the standard ISCEV standards28-33. ERG was performed at both sites; one used Burian-Allen electrodes (11 participants) and the other used DTL electrodes (11 participants). Only data acquired using the Burian-Allen electrodes was used for analysis.

Certification, Training, Quality Control, and Centralized Data Analysis

For a subset of functional and structural assessments, the Casey Reading Center performed certification of both site staff and equipment. Quality control and analysis was performed by the Casey Reading Center to ensure consistency in testing and data extraction. The tests that received this workflow are as follows: SP and KP, ffERG, SD-OCT, FP, and FAF.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis:

The statistical significance of change from the corresponding baseline average was assessed based on previously published test-retest analysis34 of the entire EIAV-ABCA participants in cohorts 1 through 5. That study established the threshold values for statistically significant changes, referred to as reliability coefficient (RC), for various parameters to be: BCVA letter score (8 letters), KVF isopters I4e, III4e, and V4e (3479; 2488 and 2622 deg2, respectively), SVF full volume HOV (VTOT, 14.6 dBsr), full field ERG 30 Hz flicker amplitude (ffERG, 28.53 mV), central macular thickness, and macular volume (4.43 μm and 0.12 mm3, respectively). For central macular thickness and macular volume, RC measurements were taken from seven participants that used follow up mode, specifically, 4-1115, 4-0513, 4-0912, 5-1211, 5-1310, 5-1409, 5-2107 OU. 5-0106 had scan errors in Screening OD (treated eye) so that one data point was omitted, but the participant was used in the analysis. For 30 Hz flicker amplitude, only participants tested with Burian Allen electrodes were used for the RC calculation. The RCs are summarized in Supplementary Table 3. Longitudinal plots of changes with statistically significant threshold values were used for presentation. The R statistical language was used to perform all statistical analyses (http://www.r-project.org). All zero values were regarded as no data. As such, when pretreatment values were zero or unmeasured, change from baseline was not calculated. Statistical significance was defined as a change that exceeded the reliability coefficient values.

Clinical significance was determined on a case-by-case basis as a durable change exceeding the RC values, considering the clinical context such as correlation among different modalities and in comparison to the contralateral eye. For 5-0106, two experienced masked graders used ImageJ (National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland) to count the number of flecks for each OCT b-scan from the macular 97-line volume scans at baseline, year one, and year three for both eyes. Flecks were defined as a subretinal hyper-reflective deposit with associated EZ disruption. Graders were also masked to each other’s results. To determine intergrader agreement, intraclass correlation coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. In the same subject, area of RPE and EZ loss was quantified using the en face OCT slab projection and manual segmentation methods as described in prior publications35,36.

Results

Safety assessments included ophthalmic examination, laboratory assessments, immunology testing, and reporting of ocular and non-ocular adverse events. A screening visit preceded the baseline visit by a maximum of 28 days. These results have been combined as Pretreatment for the analysis.

Adverse Events

There were 183 adverse events (AEs) reported in the TDU13583 and LTS13588 studies in the period of 3 years after EIAV-ABCA treatment. All 22 patients experienced at least 1 AE. Most of the AEs (163 events or 89%) were mild in intensity, 16 events (9%) were moderate, and four were reported as severe (2%). Eighteen of the events were reported as related to the investigational product, 12 of which were considered also related to the surgical procedure. Additional 74 AE were reported as related to the surgical procedure only and not related to the product. Ophthalmic AEs related to the Investigational Medicinal Product (IMP) or to surgery are summarized in Table 3. The three most common related AEs were conjunctival hemorrhage in 11 participants, intraocular pressure increase in five participants, and ocular pain in six participants. Other AEs reported related to IMP or surgery are presented in Supplemental Table 4. A total of five Serious Adverse (SAEs) events were reported (Table 2). Of these, one ocular SAE was reported as surgery-related in cohort 1. Patient 1-0425 had increased intraocular pressure (IOP) (increased to 35 from 16 mmHg at baseline).This was thought to be related to the surgical procedure, as it was first reported 1 day after subretinal injection in the study eye (OD). Although IOP elevation initially resolved by week 36 with pressure-lowering eye drops, this was categorized as an SAE, as increased IOP recurred at week 43 (31 mmHg) and became chronic, requiring long-term control with topical treatment. One non-ocular SAE was reported to be IMP-related as a miscarriage in a participant in Cohort 5 (5-2107), which occurred 2 years after the study treatment at an estimated 2 weeks of gestation. However, a second pregnancy resulted in a full-term delivery with no reported abnormalities. It is possible that consanquinity may have contributed to the risk of miscarriage. It is unknown if the incidence of miscarriage in our cohort was due to sampling artifact (small n size), or related to the investigational treatment and hence could not be completely ruled out as IMP-related. It should be noted that all patients consented to and practiced contraception for 3 months after the treatment according to protocol. Although none of the reported pregnancies occurred due to lack of compliance, they were reported as adverse events of special interest per study protocol in order to facilitate monitoring.

Table 3.

Ophthalmic Adverse Events (AE) reported to be related to investigational medicinal product (IMP) and or surgical procedure (3-year period since treatment).

| AE Preferred Term | No. of patients | % |

|---|---|---|

| Conjunctival haemorrhage | 11 | 50 |

| Intraocular pressure increased | 9 | 32 |

| Eye pain | 6 | 27 |

| Eye pruritus | 5 | 23 |

| Subretinal fluida | 5 | 23 |

| Intraocular pressure decreased (b) | 4 | 18 |

| Vitreous floaters | 4 | 18 |

| Eye irritation | 3 | 14 |

| Retinal haemorrhage | 3 | 14 |

| Anterior chamber cellc | 2 | 9 |

| Cataractd | 2 | 9 |

| Macular cyste | 2 | 9 |

| Macular oedema | 2 | 9 |

| Vitreous detachment | 2 | 9 |

| Anterior chamber inflammationf | 1 | 5 |

| Choroidal effusiong | 1 | 5 |

| Corneal abrasion | 1 | 5 |

| Corneal disorderh | 1 | 5 |

| Dyschromatopsiai | 1 | 5 |

| Eye discharge | 1 | 5 |

| Eye inflammationj | 1 | 5 |

| Eyelid irritation | 1 | 5 |

| Fundus imaging abnormalk | 1 | 5 |

| Keratic precipitatesl | 1 | 5 |

| Macular fibrosism | 1 | 5 |

| Ocular hyperaemia | 1 | 5 |

| Photopsia | 1 | 5 |

| Retinal disordern | 1 | 5 |

| Serous retinal detachment ° | 1 | 5 |

| Visual field defectp | 1 | 5 |

| Vitreous haemorrhage | 1 | 5 |

| Xanthopsiar | 1 | 5 |

As detailed below, the following patients had multiple AE's of potential relevant to ocular inflammation, however there were no consistent pattern: 2-0722, 4-0114, 4-1115, 4-0513, 5-1211 and 5-1310. All AE's resolved unless specified otherwise below.

there was inconsistent reporting of injection-related subretinal fluid due to the absence of protocol waiver; there were no reports of retinal detachments; all bleb-related subretinal fluid events resolved within 14 days except 1 patient with reported resolution 1 month after injection.

all reported as mild and with onset 1 day after surgery: resolved in 13 days in pt. 2-0722 who also had subretinal haemorrhage; resolved in 6 days in pt. 4-1115 with also reported AC cells; resolved in 6 days in same pt. no. 5-1211 who had also developed macular edema and macular fibrosis; resolved in 8 days in pt. 5-1310 who also has macular edema reported.

reported terms: "Grade 0.5 AC cell, OD" (onset 6 days after surgery, resolved in 7 days) , same patient had vitreous haemorrhage (pt. no. 4-1115)// "Trace anterior chamber cells (1-5 cells), OS" (onset 1 day after surgery, resolved in 11 days); same patient had antidrug antibodies positive at Week 24, confirmed by Western blot (HEKAg - pt.no.2-0623).

one case reported ongoing at 3 years.

reported terms: "Parafoveal cyst OD" (onset - 4 months after surgery, ongoing at 3 years) / "Intraretinal cyst in the foveal region of the left eye", (onset – 1 year 11 months after surgery, resolved in 11 months).

reported term "Mild inflammation of the anterior chamber OD" (onset 3 weeks after surgery, reported resolved in 7 months), deemed related to early discontinuation of tobradex (due to IOP increase), treated with rimexolone dose increase. Subretinal haemorrhage also was reported in the same patient (no.4-0114)

reported as mild, onset 1 day after surgery, resolved in 6 days

reported 1 day after surgery as: "Corneal folds, OD", concomitant to low IOP (5 mm Hg), resolved within 6 days with IOP increase.

reported term: "Decreased central color vision OD" (onset 1 day after surgery, ongoing).

reported term: "Subconjuctival inflammation OD" (onset 1 day after surgery, resolved in 13 days).

reported as related to IMP and surgery: "area of loss of FAF in superotemporal" (onset 4,5 months after surgery, ongoing at 3 years; pt no. 5-2107 discussed in the FAF section).

reported as related to IMP and surgery: "OS RETRO-CORNEAL PRECIPITATE", onset 2 weeks after surgery, resolved in 15 days without treatment; the same patient had also macular cyst intraretinal cyst in the foveal region° (pt. no. 4--0513).

reported term: "Slight wrinkling of Inner Limiting Membrane OS" (onset 11 days after surgery, resolution in 17 days).

reported term "Retinal tuft OS" (onset 1 day after surgery, resolved in 1 day)

reported as mild, onset 1 day after surgery, resolved in 6 days; same patient had antidrug antibodies positive on Week 24, confirmed by Western blot (VSV-G)

reported term: "dimmer peripheral vision 360 OS"; subjective complaint (onset 6 days after surgery, resolved in 10 days).

reported term: "yellowed vision (tint) OS" (8 days after surgery, resolved in 44 days).

OD, oculus dexter; OS, oculus sinister; AC, anterior chamber; IOP, intraocular pressure; FAF, fundus autofluorescence; VSV-G, vesicular stomatitis virus-G; HEKAg, human embryonic cell–associated antigen.

Table 2.

Severe adverse events (SAE) reported during 3-year period since treatment.

| Coho rt - Pt. ID |

AE Description |

SAE onset from surgery |

Outcome | Duration (Days) |

Severity | Related to IMP |

Related to Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-0425 | Elevated IOP, OD | 8 mo | Resolved | 1479 | Mild | Unrelated | Related |

| 2-0623 | Uterine polyps | 2 yr and 10 mo | Resolved | 4 | Severe | Unrelated | Unrelated |

| 2-0623 | Aortic aneurysm | 2 yr and 10 mo | Resolved | 102 | Severe | Unrelated | Unrelated |

| 2-0722 | Dyspnoea | 2 yr and 1 mo | Resolved | 35 | Mild | Unrelated | Unrelated |

| 5-2107 | miscarriage | 2 yr | Resolved | 1 | Mild | Related | Unrelated |

IMP, investigational medicinal product; IOP, intraocular pressure; OD, oculus dexter.

Three of the SAEs were reported as not related either to the IMP or the surgery. One patient in cohort 2 (2-0623) had uterine polyps and abdominal aortic aneurysm reported at 2 years and 10 months after the study treatment. The participant recovered after surgical treatment for both SAEs, and no polyp-related malignancy was detected histologically. Another participant in Cohort 2 (2-0722) experienced dyspnea and was found to have pleural thickening of unknown etiology on CT and MRI, which rapidly resolved with dexamethasone treatment for 1 month.

Laboratory Parameters and Immunological Studies

All laboratory abnormalities were evaluated by investigator for clinical significance. All significant abnormalities were reported as an AE as per usual practice. Observed hematology, blood chemistry, and urinalysis laboratory abnormalities corresponded to reported adverse events and did not suggest any trends or safety signals in relation to SAR422459 administration.

Vector biodistribution, persistence and/or shedding was investigated in blood and urine using real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis to detect and quantify vector packaging signal sequences that are unique to SAR422459, and not found in the host tissues. Specifically, vector distribution was assessed in white buffy coat using a real-time PCR assay to analyze for the presence of SAR422459 packaging signal DNA sequences, whilst persistence in plasma and shedding in urine were measured using a reverse-transcriptase real-time PCR assay to analyze for the presence of SAR422459 packaging signal RNA sequences. For all participants, vector packaging signal sequences in the blood and urine samples were either “not-detectable” or “not-quantifiable” by PCR assay suggesting the absence of any vector biodistribution, persistence or shedding.

Blood serum was analyzed for EIAV-ABCA -associated antibodies. Presence of antibodies against any putative antigenic component of the EIAV based vector were tested and included the following: VSV-G2 envelope protein, neomycin phosphotransferase, ABCA4 protein, and p26 protein (EIAV native capsid protein). All participants except for three, had negative results for presence of antibodies to EIAV-ABCA confirmed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Of the participants who showed presence of antibodies to EIAV-ABCA by ELISA, two were from cohort 3 (3-2116 and 3-1018) and demonstrated antibodies at week 24. Patient 2-1018 had no relevant inflammatory AE’s in the study eye, while patient 3-2116 had serous retinal detachment on day 1 after surgery and resolved on day 6. For these participants, the Western blot antibody tests demonstrated that the responses were directed against the VSV-G2 envelope protein, and were negative prior to treatment and at week 4, and became positive at week 24, confirming the induction of a response. The third participant with presence of antibodies was from cohort 2 (2-0623), and demonstrated levels of antibodies against EIAV-ABCA, above that of the negative control in the ELISA, at all-time points studied. This patient had trace anterior chamber cells (1-5 cells/high power field) on the day after surgery and resolved in 11 days. The Western blot assay showed that there were no antibody responses against the VSV-G2, p26, ABCA4 or neomycin phosphotransferase components, and that the positive response by ELISA was directed towards a packaging cell protein; however, as this response was detected prior to treatment, as well as in week 4 and week 24, it was not considered to be induced by the treatment. Overall, there was no correlation between inflammatory AE’s and the presence of detectable antibodies against the EIAV capsid protein. Moreover, all inflammatory AE’s resolved as detailed in Table 3.

Subretinal Delivery of the Gene Product

Subretinal gene therapy was delivered both to the subfoveal retina as well as the extra-foveal retina. The location of the bleb was confirmed by schematics drawn by the surgeon and/or by review of surgery photos and video recordings by a central reviewer. Twelve patients had subfoveal spread of the bleb: 1-0201, 1-0124, 2-0722, 3-1517, 3-2116, 4-0114, 4-0513, 4-0912, 5-1211, 5-1310, 5-1409, and 5-2107. The bleb location in the other ten participants was extra-foveal. Among these 22 patients, the central reviewer did not have sufficient information to determine the exact location of the bleb in 8 patients beyond written descriptions of “subfoveal” (1-0124, 2-0722, 3-1517, 3-2116, 4-0513), “extrafoveal” (2-0521), or “peripheral” (1-0425, 2-0920). Additional written description was available for two patients. For 1-0425, the retinotomy was superior and the bleb extended from the superior major arcade to the ora serrata and centered on the 12 o’clock meridian. For 2-0722, retinotomy was outside the superotemporal arcade, and the bleb extended into the macula.

Visual Acuity (BCVA)

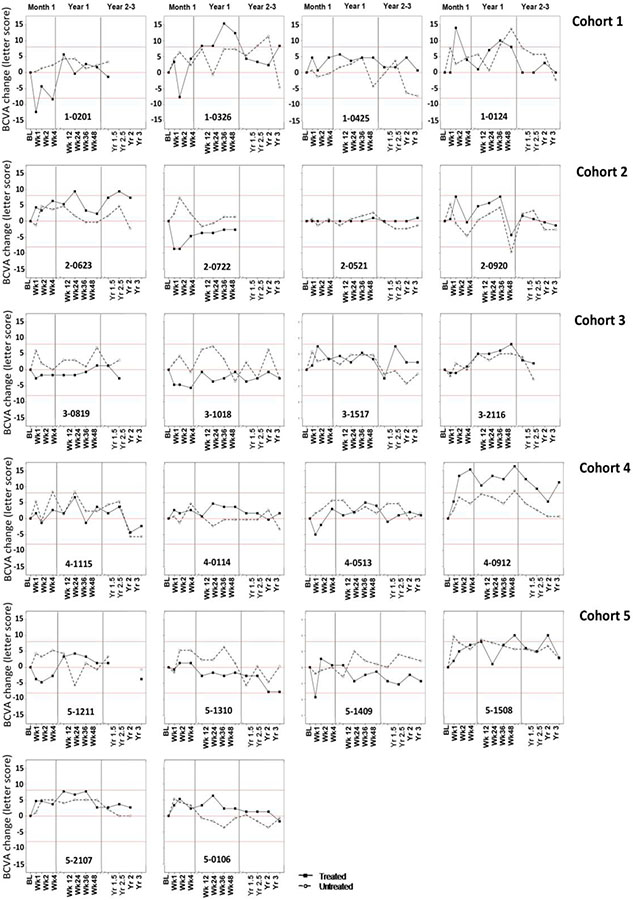

In all of the cohorts, the range of BCVA measured in the treated and the untreated eye is compared to the RC in this participant group (+/−8 ETDRS letters – shown as red lines), predicted based on previous evaluation of this group34. All participants from each cohort are shown in Figure 1. All of the BCVA participant data are listed as raw (Supplementary Figure 1). Visual acuity dropped immediately following the injection for the majority of the participants but returned to the baseline level by week 12 or earlier (Figure 1). Four participants had statistically significant intermittent increases in BCVA following the treatment, 1-0326, 2-0623, 4-0912 and 5-1508 in the treated eye (Figure 1), but none were clinically significant. Participant 4-0912 appeared to exhibit a durable increase in BCVA only in the treated eye starting at week 2 that was maintained up to year 3 (Figure 1). However, given the lack of correlation with other visual function tests or imaging modalities, it was determined that 4-0912’s improvement was not clinically significant. Moreover, except for baseline and week 1, the EDTRS scores were similar between the two eyes (Supp Figure 1), which suggests that there may have been an unconscious bias to underperform at baseline. None of the subjects showed statistically significant decreases in BCVA after recovering from surgery.

Figure 1.

Best corrected visual acuity (BCVA) change (letter score) from pretreatment for all participants.

Static Perimetry (SP)

Throughout the three-year follow up period, VTOT for the treated and untreated eyes for most participants remained within the confines of the RC limits (+/−14.62 dB-sr) calculated for this participant group34. Most participants showed no significant changes within the limits of reliability; the findings for the five cohorts are shown with all participants from each cohort in Figure 2. One participant (3-0819) had statistically significant increases in VTOT (Figure 2) at visits week 36 and 48 only. Intermittent statistically significant decreases in VTOT were observed in the untreated eye of 4-0114, the treated eye of 5-1211, and both eyes of 4-1115. All of the VTOT participant data is listed as raw (Supplementary Figure 2). Overall, given the lack of a durable effect and/or correlation with other visual function tests in the treated eye relative to the untreated eye, we concluded that there were no clinically significant changes in SP.

Figure 2.

Hill of vision, total volume (VTOT HOV) change (dB-sr) from pretreatment for all participants

Kinetic Perimetry (KP)

The total seeing area was measured by KP for test targets V4e, III4e and I4e. RC limits from Parker et al34 were applied to determine significant change as follows; I4e (+/− 3478.85 deg2), III4e (+/− 2488.02 deg2), and V4e (+/− 2622.46 deg2). In summary, similarly to the static perimetry, most participants showed no significant changes within the limits of reliability. A change from pretreatment data for all participants from each cohort are shown in Supplementary Figures 3,4 and5 for isopter I4e, III4e and V4e respectively. KP data is listed as raw data for all participants in Supplementary Figures 6,7 and8 for isopters I4e, III4e and V4e respectively. In cases where the patient could not see the test target, the associated isopters could not be recorded and thus not available for analysis. A few participants showed statistically significant changes with isopter III4e (supplementary figure 4) and isopter V4e (Supplementary figure 5). One participant (3-0819) had statistically significant increases in isopters III4e and V4e that correlated with the change in the SP VTOT at weeks 36 and 48. However, the SP reliability factor (RF) indicated that the results were not reliable and thus not clinically significant. The SP and KP reports are shown in Supplementary Figure 9. Similar to SP, there were no clinically significant changes in KP.

Multimodal Imaging

All participants from each cohort are shown in Figure 3 for treated and untreated eyes. In most participants, CFP and FAF revealed a small iatrogenic area of RPE attenuation at the site of the retinotomy seen as decreased autofluorescence (Figure 3, white arrows). Most participants from the earlier cohorts with more advanced disease (cohorts 1-3) showed no changes in FAF or CFP in either eye beyond the expected progression for Stargardt disease, but it is important to note that these participants previously had diffuse, severe retinal and RPE atrophy and hypoautofluorescence at baseline. One patient from cohort 5 (5-1508) showed a post-treatment decline in hyperautofluorescent flecks in the treated eye compared to the untreated eye that could not be accounted for by diffuse severe worsening of RPE atrophy alone (Figure 3, yellow asterisks). Additional analysis of the flecks in correlation with b-scans on SD-OCT showed a relative reduction in subretinal flecks without diffuse worsening of RPE atrophy (Figure 4 A). This reduction in flecks was confirmed by two independent graders, who were masked to the treatment conditions. This decline in the total number of macular flecks in the treated eye diverged significantly from the untreated eye at week 48 (p =0.05), and was sustained to year 3 (p =0.02; Figure 4 B). The intraclass correlation coefficient of the two graders was 0.78 (95% CI: 0.75-0.81), indicating good reliability. Quantification of RPE atrophy and EZ loss within the OCT volume scan in subject 5-1508 showed a similar progression from baseline to year three of RPE atrophy for the treated (33%) and non-treated (31%) eyes and similar degree of EZ loss treated (26%) and non-treated (25%) eyes (Supplementary Figure 10). These observations were not associated with any significant functional changes in this patient.

Figure 3.

Representative color fundus photography (CFP) and fundus autofluorescence (FAF) in all participants for treated and untreated eye at baseline and year 3 visits or the last available visit. The bleb locations were outlined with white and red dashed lines on the CFP and FAF images respectively. Cases where the exact bleb location was not discernable are labeled as “subfoveal”, “extrafoveal”, or “peripheral” according to the surgical records. Peripheral refers to bleb locations beyond the arcades, and extrafoveal indicates that the fovea was not detached. Areas of increased hypoautofluorescence that appeared to be worse in the treated eye relative to the untreated eye are marked with a yellow arrow head.

Figure 4.

Participant 5-1508. A) fundus autofluorescence (FAF) and spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) show a gradual decline in the flecks in the treated eye compared to the untreated eye. B) Masked grading of the number of flecks within a macular SD-OCT volume scan declined significantly by week 48 and was sustained to year 3. Asterisk, p ≤0.05.

Six participants, with the majority in cohort 5 (2-0623, 4-1115, 5-1310, 5-1409, 5-2107, and 5-0106), developed additional hypoautofluorescent areas or enlargements of existing hypoautofluorescent lesions that appeared to be greater in the treated eye compared with the non-treated eye (Figure 3, yellow arrowheads). No significant functional changes were observed in these participants; however, the most severely affected patient (5-2107) showed a trend towards an enlarged scotoma on static perimetry that correlated with the area of expanding hypoautofluorescence (Figure 5). Scrutiny of the FAF at week 4 showed demarcation lines (blue arrows) in the temporal raphe followed by development of a clear area of hypoautofluorescence by week 24 and 48 (Figure 5 C, D), which was correlated with hyperpigmentation on CFP (Figure 5 G, H). The boundaries of this area of hypoautofluorescence did not correspond exactly with the extent of the bleb, which encompassed a larger area (white dashed line on CF and red dashed line on FAF). Although a trend in worsening of the central scotoma towards the inferonasal periphery was noted (Figure 5 I-L), BCVA was not significantly affected. There was RPE thinning observed on SD-OCT at week 48 visit corresponding to the hypoautofluorescent area (Figure 5, M and O, yellow arrows).

Figure 5.

FAF Images of the autofluorescent retina (A, B, C and D), fundus color images (E, F, G and H), Hill of vision (HOV) (I, J, K and L), spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) line scans (M and O) and volume maps (N and P) at the baseline (A, E, I, M and N), week 4 (B, F and J), week 24 (C, G, K) and week 48 (D, H, L, O and P) visits for left eye of participant 5-2107. The demarcation lines (pointed to by blue arrows) in the temporal raphe were observed on the FAF images at week 4 (B) followed by development of hypoautofluorescence noted in week 24 (Figure C, D). Hyperpigmentation was noted on the fundus images corresponding the areas of hypoautofluorescence on FAF images at weeks 24 and 48 (G and H).

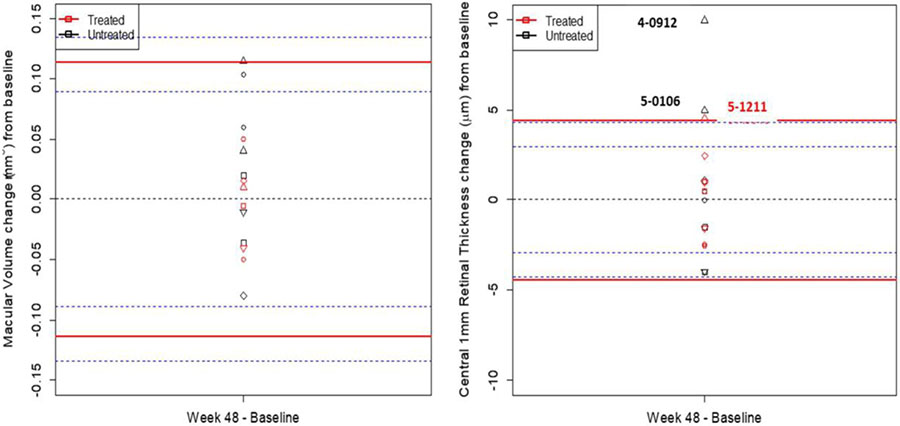

The macular thickness (SD-OCT MT) and macular volume (SD-OCT MV) of the central 1 mm was quantified with SD-OCT (Figure 6). The RC values from SD-OCT MT were measured as +/− 4.43 (μm) and SD-OCT MV as +/− 0.12 (mm3). The untreated eyes of participants 4-0912 and 5-0106 demonstrated a statistically significant increase in SD-OCT MT. These changes were likely due to non-clinically significant fluctuations of subretinal deposits for 5-0106 (5 μm) and pupil entry position changes in the reflectivity of structures for participant 4-0912 (10 μm)37. All other participants were within the limits of reliability for both SD-OCT MT and SD-OCT MV at week 48 (Figure 6). OCT cross-sectional b-scans were show for all participants from each cohort in Supplementary figure 11. If the OCT data was not acquired in the follow-up mode (subjects 1-0201; 2-0623, 2-0521 and 3-0819) the appropriate b-scan section was chosen closest to baseline. Overall, majorly of subjects showed severe RPE and outer retinal atrophy typical for patients with advanced stage Stargardt disease. No significant differences were observed between visits.

Figure 6.

Central Retinal Thickness (CRT) and Macula Volume (MV) change from Pretreatment.

Electroretinography

Although ERG was performed at both sites, one used Burian-Allen electrodes and the other used DTL electrodes. The DTL data was markedly noisier and therefore not comparable to the Burian-Allen electrode data. As a result, only ERGs performed with Burian Allen electrodes were analyzed38. Multifocal ERG recordings were severely attenuated in most participants with a poor signal-to-noise ratio and high variability and were therefore not analyzed further. There was also significant variability and low signal-to-noise ratio for the ffERG responses, and only the 30 Hz waveforms were considered to be of sufficient and consistent quality for analysis. The RC values from the ffERG 30Hz flicker amplitudes and implicit time were measured as +/− 28.53 (μV) and +/− 2.8 (ms), respectively, and were used to determine a statistically significant change (Supplementary Table 2). Five participants showed statistically significant changes but they were not clinically significant (Supplementary Figure 12-15). For example, two participants (5-1310 and 5-1409) had a statistically significant decline in 30 Hz flicker amplitude (μV) starting at year 2 and week 48, respectively. However, given the change was similar in severity and timing in both the treated and untreated eye, it was thought to be secondary to underlying disease progression and not clinically significant for treatment effect.

Discussion

We report the 3-year data from the first open label dose-escalation phase I/IIa gene therapy clinical trial of a subretinally injected lentiviral vector for SD due to mutations in ABCA4. The treatment was generally well-tolerated and safe. The majority of the AEs were routine side-effects associated with the surgical procedure that did not require treatment and resolved with time. The only ocular SAE was chronic ocular hypertension. Although we cannot conclude definitively that it occurred due to peri-operative corticosteroid exposure, gene therapy may be less likely given that this SAE occurred at a lower vector dose and was not observed at higher doses. Spontaneous pregnancy loss in a participant was another reported SAE, but the participant later conceived and delivered a child without complications. Therefore, we cannot rule out the contribution of consanguinity in this case or the possibility of coincidence, especially given the prevalence of pregnancy loss in the general population39. Similarly, laboratory assessments gave no indication of any systemic effect that would warrant concern with the use of this agent in upcoming trials. There were no SAEs reported related to laboratory parameters or immunological studies.

Subretinal delivery of gene therapy results in mechanical disruption of the photoreceptor RPE interface within the bleb area, resulting in a temporary worsening of visual function19-21. In our study, most participants had a decline in BCVA immediately following the injection, but visual function returned to baseline values within 12 weeks. These findings are consistent with other subretinal gene therapy studies 40-51. Overall, there were no clinically significant changes in BCVA attributable to the gene therapy. Although, subject 4-0912 demonstrated a statistically significant and durable improvement gain in BCVA from 18 to 32 letters in only the treated eye starting at week 2, it was not considered to be clinically significant. We do not know if this was a treatment related effect due to the following: 1) the improvement occurred very early during the recovery phase, 2) there was no clinical correlation with improvements in other measures of visual function, and 3) no other patients showed a response in BCVA so a dose-response could not be established. In addition, because this is an open label study, subconscious bias may have led to underperformance at screening/baseline. Potential learning effect is another explanation and has previously been shown in SD natural history studies52. In addition, we did not observe a deviation between the treated and fellow eye with regard to change in BCVA over time. However, the RC value was +/− 8 EDTRS letters change in our study, whereas prior natural history studies reported a slow decline of 0.65 letters per year53. Thus our follow-up period of 3 years would be insufficient to detect any benefit in any treatment-related stabilization of BCVA.

The results showed no clinically significant changes in perimetry and electrophysiology, which underscore the overall safety of EIAV-ABCA4. However, the RC values were indicative of inherently high variability in the SP and KP data sets, which are likely a product of poor fixation and visual function in our cohort of SD patients with advanced disease. These observations show that the utility of perimetry may be limited in patients with poor vision, but it will be more useful in later cohorts of SD patients with better visual acuity and fixation.

Multimodal imaging showed significant and durable resolution of flecks in the treated eye in one patient, 5-1508, from cohort 5 (Figure 4) that was significantly greater than the untreated eye. The gradual improvement in the treated eye was evident on FAF and SD-OCT starting at 3 months, and the fleck count within the macula declined dramatically by 48 weeks. In comparison, the untreated eye maintained high numbers of flecks through year 3. Quantification of RPE and EZ loss show a similar rate of progression in both treated and untreated eyes, which suggests that the contribution of tissue loss towards the disappearance of flecks was equal between the two eyes (Supplemental Figure 10). Nevertheless, the rate of fleck loss was greater in the treated eye. (Figure 4B) Thus, these observations may represent the first signs of biological activity of the gene therapy in this early phase study. However, these structural changes were not correlated with any improvements in visual function, and no other patients had the same response. In addition, these findings are also tempered by the potentially traumatic nature of subretinal injection in other subjects.

Due to the severity of macular atrophy in these early cohorts, EZ-band analysis from SD-OCT line or volume scans was limited due to extension of EZ loss beyond the limits of the b-scan in most patients and/or heterogenous EZ changes that were difficult to quantify. However, FAF and SD-OCT showed progression of RPE changes in six patients appeared to be greater in the treated than the untreated eye (Figure 3). Five patients were from the highest dose cohorts (1.8 x106 TU in cohort 4 and 5), and of these, four were from the group C (cohort 5) patients with better BCVA (≤20/100). These trends suggest that the etiology may be dose-related and/or a mechanical issue that is more evident or prone to occur in patients with better BCVA and milder disease with more intact RPE. We cannot rule out that “off-target” transduction of ABCA4 to the RPE layer beyond a certain threshold may be harmful. While it remains controversial, recent studies showed that the RPE cells may also natively express the ABCA4 protein54 and may benefit from gene therapy (Mitra Farnoodian-Tedrick, ARVO abstract, Loss of ABCA4 Function And Altered Lipidomic of Retinal Pigment Epithelium: A New Link To Stargardt Pathogenesis, 2021). It is also possible that this exacerbation of RPE atrophy may be due to a dose-related immune reaction to the EIAV viral capsid and/or CpG motifs, which is known to play a role in gene therapy with adeno-associated viruses55.

While it can be difficult to stratify the contribution of multiple factors in each case, the discrete continuous character of the area of RPE atrophy in patient 5-2107 likely represents RPE damage from retinal detachment during bleb formation. In this case, subtle hyperautofluorescent RPE demarcation lines within the bleb area were observed as early as week 4 and could be an initial sign of mechanical disturbance. Furthermore, the boundary of the RPE atrophy do not exactly match the area of the bleb, which is highly suggestive of damage during creation of the bleb rather than drug-induced toxicity or disease exacerbation. Similar observations of tissue damage following subretinal injections have been described in other studies56-58. It has been proposed that subretinal fluid dissection can lead to hydraulic damage to the apical surface of the RPE58. Thus, the use of automated injectors that ensure continuous low hydraulic pressure during bleb formation will be useful in future gene therapy clinical trials to reduce the risk of mechanical damage. Lastly, most patients in groups A-B (cohorts 1-4) already had severe and diffuse outer retinal and RPE atrophy at baseline, which may have confounded our ability to observe this phenomenon in the low dose cohorts.

One major disadvantage of this study, designed for safety purposes, was that participants, especially in the early cohorts, had advanced disease and poor visual acuity/fixation, which contributed to decreased reliability of the functional tests and made imaging more challenging. In addition, patients with severe retinal degeneration likely benefit less from gene therapy due to lower levels of viable tissue for transduction. However, this was an early phase clinical trial, and safety was the primary endpoint. Another weakness of our study is the lack of fixation data. SD patients with central scotoma develop eccentric fixation that can change over time, which influences the results of visual fields59. In future trials, it would be useful to quantify changes in fixation, eccentricity, and locations of the preferred retinal locus in order to improve the utility of perimetry as an endpoint in SD. Finally, this study was also nonrandomized and limited by small patient numbers, but SD is a rare disease and thus the size of the cohorts and open label study design were commensurate with an early phase clinical trial.

Similar to a previous study utilizing the same vector60 this study has demonstrated that lentiviral vectors may be a potential platform for delivery of large genes that are beyond the capacity of AAV vectors. We show that the subretinal injection of EIAV in SD is generally safe, and continued development of EIAV and dedicated subretinal injection tools will likely improve the safety of these procedures. Further studies in patients with milder disease and more viable retinal tissue will be needed to fully determine the safety and efficacy profile of this treatment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thank the following people:

Coordinators at Oregon Health & Science University, Casey Eye Institute, Portland, Oregon, USA: Catie Schlechter, Catie Beattie, Maureen McBride, Chris Whitebirch, Rachael Putnam, Kimberly Voelker, Connor Benson, Paula Rauch, Joycelyn Niimi, Mihir Wanchoo, Hardew Mahto, Deanna Ternes, Beverly Thean, Annelise Haft, Halie Sklanka, Jennifer Blackerby, Tamila Williams.

Coordinators at Centre Hospitalier National d’Ophtalmologie des Quinze-Vingts, Paris, France: Dorothée Dagostinoz, Céline Devisme, Serge Sancho, Céline Chaumette, Juliette Amaudruz, Caroline Ivars-Roux Christina Zeitz, Claire-Marie Dhaenens, Marie-Hélène Errera, Neila Seidira, Emmanuel Héron, Caroline Laurent-Coriat, Mathias Chapon, Victoria Ganem, Jeanne Haidar, patients and families

Sanofi: Yves Archimbaud, Ronald Buggage, Caroline Cohen, Jennifer Kelley, Jian Li, Noelle Pouget, Annie Purvis.

CRC Staff not listed as authors: Mitra Adeli, Edye Parker, Shobana Aravind, Albert Romo, Audra Miller, Edeleidys Sanchez Saucedo, William Stanford.

Oxford Biomedica: Michelle Kelleher, Yatish Lad, Kyriacos Mitrophanous, Julie Loader, Daniel Blount

All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Funding from the Paul H. Casey Ophthalmic Genetics Division

Funding

Unrestricted Grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York and P30 EY010572.

Foundation Fighting Blindness (Columbia, MD): CD-NMT-0714-0648-OHSU (PY), CD-NMT-0914-0659-OHSU (MEP), C-CL-0711-0534-OHSU01 (Unrestricted, CEI)

Foundation Fighting Blindness Center Grant (Paris) [C-CMM-0907-0428-INSERM04]

Research to Prevent Blindness (New York, NY): Career Development Award (MEP), Unrestricted Grant from RPB (CEI), P30EY010572 (CEI)

National Institutes of Health (Bethesda, MD): 1K08 EY0231186 (MEP), 1K08 EY026650 (PY), 1R01 EY029985 (RMD, CWM)

LABEX LIFESENSES (ANR-10-LABX-65)

IHU FOReSIGHT (ANR-18-IAHU-01)

Inserm-DGOS funding to CIC 1423

Rare Disease Reference Center Grant

Oxford Biomedica was sponsor of SAR422459 clinical studies on 2011-2014

Sanofi is sponsor of SAR422459 clinical studies since 2014.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Allikmets R, Singh Sun H et al. A photoreceptor cell-specific ATP-binding transporter gene (ABCR) is mutated in recessive Stargardt macular dystrophy. Nat Genet. 1997;15(3):236–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dean M, Hamon Y, Chimini G. The human ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter superfamily. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(7):1007–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molday R, Zhang K. Defective lipid transport and biosynthesis in recessive and dominant Stargardt macular degeneration. Prog Lipid Res. 2010;49(4):476–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang K, Kniazeva M, Hutchinson A et al. The ABCR gene in recessive and dominant Stargardt diseases: a genetic pathway in macular degeneration. Genomics. 1999; 60(2):234–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saksens NT, Fleckenstein M, Schmitz-Valckenberg S et al. Macular dystrophies mimicking age-related macular degeneration. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2014;39: 23–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walia S, Fishman GA. Natural history of phenotypic changes in Stargardt’s macular dystrophy. Ophthalmic Genet. 2009;30(2):63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gemenetzi M, Lotery AJ. Phenotype/genotype correlation in a case series of Stargardt's patients identifies novel mutations in the ABCA4 gene. Eye (Lond). 2013;27(11):1316–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westeneng-van Haaften SC, Boon CJ, Cremers FP et al. Clinical and genetic characteristics of late-onset Stargardt's disease. Ophthalmology. 2012. Jun;119(6):1199–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong X, Fujinami K, Strauss RW et al. Visual Acuity Change Over 24 Months and Its Association With Foveal Phenotype and Genotype in Individuals With Stargardt Disease: ProgStar Study Report No. 10. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(8):920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nassisi M, Mohand-Saïd S, Dhaenens CM et al. Expanding the Mutation Spectrum in ABCA4: Sixty Novel Disease Causing Variants and Their Associated Phenotype in a Large French Stargardt Cohort. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishman GA, Farbman JS, Alexander KR Delayed rod dark adaptation in patients with Stargardt's disease. Ophthalmology. 1991;98(6):957–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantyjarvi M,Tuppurainen K Color vision in Stargardt's disease. Int Ophthalmol. 1992;16:423–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y, Ratnam K, Sanna M et al. Cone photoreceptor abnormalities correlate with vision loss in patients with Stargardt disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sc. 2011;52:3281–3292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zernant J, Schubert A, Im K et al. Analysis of the ABCA4 gene by next-generation sequencing. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(11):8479–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quazi F, Molday RS. ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA4 and chemical isomerization protect photoreceptor cells from the toxic accumulation of excess 11 -cis-retinal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(13):5024–5029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsybovsky Y, Molday RS, Palczewski K. The ATP-binding cassette transporter ABCA4: structural and functional properties and role in retinal disease. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2010;703:105–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamiri Parisa, Sugita Sunao, Streilein J. Wayne. Immunosuppressive Properties of the Pigmented Epithelial Cells and the Subretinal Space. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2007. 92:86–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mitrophanous K, Yoon S, Rohll J et al. Stable gene transfer to the nervous system using a non-primate lentiviral vector. Gene Ther.1999;6:1808–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kong J, Kim A, Binley K et al. Correction of the disease phenotype in the mouse model of Stargardt disease by lentiviral gene therapy. Gene Ther. 2008;15(19):1311–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campochiaro PA, Lauer A, Sohn E et al. Lentiviral vector gene transfer of endostatin/angiostatin for macular degeneration (GEM) study. Hum Gene Ther. 2017;28(1):99–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Binley K, Widdowson P, Loader J et al. Transduction of photoreceptors with equine infectious anemia virus lentiviral vectors: safety and biodistribution of StarGen for Stargardt disease. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(6):4061–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Binley K, Widdowson PS, Kelleher M et al. Safety and biodistribution of an equine infectious anemia virus-based gene therapy, RetinoStat((R)), for age-related macular degeneration. Hum Gene Ther. 2012;23(9):980–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lois N, Holder GE, Bunce C, Fitzke FW, Bird AC. Phenotypic subtypes of Stargardt macular dystrophy-fundus flavimaculatus. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(3):359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study design and baseline patient characteristics. ETDRS report number 7. Ophthalmology.1991;98(5):741–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weleber RG, Smith TB, Peters D, et al. VFMA: topographic analysis of sensitivity data ffull-field static perimetry. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2015;4:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krebs I, Smretschining E, Moussa S, et al. Quality and reproducibility of retinal thickness measurements in two spectral-domain optical coherence tomography machines. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):6925–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strauss RW, Muñoz B, Wolfson Y, et al. Assessment of estimated retinal atrophy progression in Stargardt macular dystrophy using spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;0:1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constable PA, Back A, Frishman LJ et al. Erratum to: ISCEV Standard for clinical electro-oculography (2017 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2017;134:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Constable PA, Bach M, Frishman LJ et al. ISCEV Standard for clinical electro-oculography (2017 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2017;134(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Holder GE, Brigell MG, Hawlina M,. et al. ISCEV standard for clinical pattern electroretinography--2007 update. Doc Ophthalmol. 2007;114(3):111–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hood DC, Bach M, Brigell M, et al. ISCEV standard for clinical multifocal electroretinography (mfERG) (2011 edition). Doc Ophthalmol. 2012. Feb;124(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marmor MF, Fulton AB, Holder GE, et al. ISCEV Standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2008 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2009. Feb;118(1):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCulloch DL, Marmor MF, Brigell MG et al. Erratum to: ISCEV Standard for full-field clinical electroretinography (2015 update). Doc Ophthalmol. 2015;130(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker M, Choi D, Erker LR, et al. Test-retest variability of functional and structural parameters in patients with Stargardt disease participating in the SAR422459 gene therapy trial. TVST.2016;5,10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alabduljalil T, Patel RC, Alqahtani AA et al. Correlation of Outer Retinal Degeneration and Choriocapillaris Loss in Stargardt disease using en face OCT and OCT Angiography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2019. Jun;202:79–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Smith T, Parker M, Steinkamp P et al. Reliability of Spectral-Domain OCT Ellipsoid Zone Area and Shape Measurements in Retinitis Pigmentosa. TVST. 2019; 8(3):37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrasco-Zevallos O, Nankivil D, Keller B, et al. Pupil tracking optical coherence tomography for precise control of pupil entry position. Biomed Opt Express. 2015;6(9):3405–3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton R, Al Abdlseaed A, Healey J, et al. Multi center variability of ISCEV standard ERGs in two normal adults. Doc Ophthalmol. 2015;130(2):83–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Evaluation and treatment of recurrent pregnancy loss: a committee opinion. The Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril. 2012;98(5):1103–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miraldi UV, Coussa RG, Antaki F, Traboulsi EI. Gene therapy for RPE65-related retinal disease. Ophthalmic Genet. 2018;39(6):671–677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kumaran N, Moore AT, Weleber RG, Michaelides M. Leber congenital amaurosis/early-onset severe retinal dystrophy: clinical features, molecular genetics, and therapeutic interventions. Br J Ophthalmol. 2017;101(9):1147–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bennett J, Wellman J, Marshall KA, et al. Safety and durability of effect of contralateral-eye administration of AAV2 gene therapy in patients with childhood-onset blindness caused by RPE65 mutations: a follow-on phase I trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10045):661–672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weleber RG, Pennesi ME, Wilson DJ, et al. Results at 2 years after gene therapy for RPE65-deficient Lbere congenital amaurosis and severe early-childhood onset retinal dystrophy. Ophthalmology. 2016;123(7):1606–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis. New Neg J Med. 2008;358(21):2231–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le Meur G, Lebranchu P, Billaud F, et al. Safety and long-term efficacy of aav4 gene therapy in patients with rpe65 Lebere congenital amaurosis. Molecular Therapy. 2018;26(1):256–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spark Therapeutics Inc. LUXTURNA (voretigene neparvovec-rzyl) [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Spark Therapeutics, Inc; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mitsio A, Dubis AM, Moosajee M. Choroideremia: from genetic and clinical phenotyping to gene therapy and future treatments. Ther Adv Ophthalmol 2018;10:2515841418817490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MI Patricio, Barnard AR, Xue K, et al. Choroideremia: molecular mechanisms and development of AAV gene therapy. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2018;18(7):807–820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xue K, MacLaren RE. Ocular gene therapy for choroideremia: clinical trials and future perspectives. Exp Rev Ophthalmol.2018;13(3):129–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Beltran WA, Cideciyan AV, Aquirre GD, et al. Optimization of retinal gene therapy for x-linked retinitis pigmentosa due to RPGR mutations. Mol Ther. 2017;25(8):1866–1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martinez-Fernandez De La Camara C, Nanda A, MacLaren RE, et al. Gene therapy for the treatment of X-linked retinitis pigmentosa. Expert Opin Orphan Drugs. 2018;6(3):167–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kong X, Strauss RW, Cideciyan AV, et al. Visual Acuity Change over 12 Months in the Prospective Progression of Atrophy Secondary to Stargardt Disease (ProgStar) Study: ProgStar Report Number 6. Ophthalmology. 2017;124(11):1640–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kong Xiangrong, Fujinami Kaoru, Strauss Rupert W., et al. Visual Acuity Change Over 24 Months and Its Association With Foveal Phenotype and Genotype in Individuals With Stargardt Disease. ProgStar Study Report No. 10. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018. Aug;136(8):920–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lenis TL, Hu J, Ng SY et al. Expression of ABCA4 in the retinal pigment epithelium and its implications for Stargardt macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(47):E11120–E11127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiang Z, Kurupati R, Li Y, et al. The Effect of CpG Sequences on Capsid-Specific CD8 + T Cell Responses to AAV Vector Gene Transfer. Mol Ther. 2020;28(3):771–783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Nina Buus Sørensen. Subretinal surgery: functional and histological consequences of entry into the subretinal space. Acta Ophthalmol. 2019;97 Suppl A114:1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maia M, Penha F, Rodrigues E, et al. Effects of Subretinal Injection of Patent Blue and Trypan Blue in Rabbits. Curr Eye Res. 2007;32(4):309–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takahashi K, Morizane Y, Hisatomi T, et al. The influence of subretinal injection pressure on the microstructure of the monkey retina. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0209996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andre Messias; Jens Reinhard; Antonio Augusto et al. Eccentric Fixation in Stargardt’s Disease Assessed by Tübingen Perimetry. IOVS. 2007; 48: 5815–5822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lenis T, Hu J, Ng SY et al. Expression of ABCA4 in the retinal pigment epithelium and its implications for Stargardt macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2018;115(47):E11120–E11127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.