Abstract

Background

Schizophrenia is a disabling psychotic disorder characterised by positive symptoms of delusions, hallucinations, disorganised speech and behaviour; and negative symptoms such as affective flattening and lack of motivation. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a psychological intervention that aims to change the way in which a person interprets and evaluates their experiences, helping them to identify and link feelings and patterns of thinking that underpin distress. CBT models targeting symptoms of psychosis (CBTp) have been developed for many mental health conditions including schizophrenia. CBTp has been suggested as a useful add‐on therapy to medication for people with schizophrenia. While CBT for people with schizophrenia was mainly developed as an individual treatment, it is expensive and a group approach may be more cost‐effective. Group CBTp can be defined as a group intervention targeting psychotic symptoms, based on the cognitive behavioural model. In group CBTp, people work collaboratively on coping with distressing hallucinations, analysing evidence for their delusions, and developing problem‐solving and social skills. However, the evidence for effectiveness is far from conclusive.

Objectives

To investigate efficacy and acceptability of group CBT applied to psychosis compared with standard care or other psychosocial interventions, for people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Search methods

On 10 February 2021, we searched the Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials, which is based on CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, four other databases and two trials registries. We handsearched the reference lists of relevant papers and previous systematic reviews and contacted experts in the field for supplemental data.

Selection criteria

We selected randomised controlled trials allocating adults with schizophrenia to receive either group CBT for schizophrenia, compared with standard care, or any other psychosocial intervention (group or individual).

Data collection and analysis

We complied with Cochrane recommended standard of conduct for data screening and collection. Where possible, we calculated risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) for binary data and mean difference (MD) and 95% CI for continuous data. We used a random‐effects model for analyses. We assessed risk of bias for included studies and created a summary of findings table using GRADE.

Main results

The review includes 24 studies (1900 participants). All studies compared group CBTp with treatments that a person with schizophrenia would normally receive in a standard mental health service (standard care) or any other psychosocial intervention (group or individual). None of the studies compared group CBTp with individual CBTp. Overall risk of bias within the trials was moderate to low.

We found no studies reporting data for our primary outcome of clinically important change. With regard to numbers of participants leaving the study early, group CBTp has little or no effect compared to standard care or other psychosocial interventions (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.59; studies = 13, participants = 1267; I2 = 9%; low‐certainty evidence). Group CBTp may have some advantage over standard care or other psychosocial interventions for overall mental state at the end of treatment for endpoint scores on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) total (MD –3.73, 95% CI –4.63 to –2.83; studies = 12, participants = 1036; I2 = 5%; low‐certainty evidence). Group CBTp seems to have little or no effect on PANSS positive symptoms (MD –0.45, 95% CI –1.30 to 0.40; studies =8, participants = 539; I2 = 0%) and on PANSS negative symptoms scores at the end of treatment (MD –0.73, 95% CI –1.68 to 0.21; studies = 9, participants = 768; I2 = 65%). Group CBTp seems to have an advantage over standard care or other psychosocial interventions on global functioning measured by Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF; MD –3.61, 95% CI –6.37 to –0.84; studies = 5, participants = 254; I2 = 0%; moderate‐certainty evidence), Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP; MD 3.30, 95% CI 2.00 to 4.60; studies = 1, participants = 100), and Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS; MD –1.27, 95% CI –2.46 to –0.08; studies = 1, participants = 116). Service use data were equivocal with no real differences between treatment groups for number of participants hospitalised (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.38 to 1.60; studies = 3, participants = 235; I2 = 34%). There was no clear difference between group CBTp and standard care or other psychosocial interventions endpoint scores on depression and quality of life outcomes, except for quality of life measured by World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (WHOQOL‐BREF) Psychological domain subscale (MD –4.64, 95% CI –9.04 to –0.24; studies = 2, participants = 132; I2 = 77%). The studies did not report relapse or adverse effects.

Authors' conclusions

Group CBTp appears to be no better or worse than standard care or other psychosocial interventions for people with schizophrenia in terms of leaving the study early, service use and general quality of life. Group CBTp seems to be more effective than standard care or other psychosocial interventions on overall mental state and global functioning scores. These results may not be widely applicable as each study had a low sample size. Therefore, no firm conclusions concerning the efficacy of group CBTp for people with schizophrenia can currently be made. More high‐quality research, reporting useable and relevant data is needed.

Keywords: Adult, Humans, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy/methods, Hallucinations, Hallucinations/etiology, Hallucinations/therapy, Psychotic Disorders, Psychotic Disorders/therapy, Quality of Life, Schizophrenia, Schizophrenia/drug therapy

Plain language summary

Group cognitive behavioural therapy for schizophrenia

Review question

Is group cognitive behavioural therapy (talking therapy) that targets psychoses (CBTp) more effective than standard care (the care a person would normally receive) or other forms of talking therapies (for example, counselling, supportive therapy; either group or individual) for people with schizophrenia?

What is schizophrenia?

Schizophrenia is a disabling serious mental illness. It is characterised by delusions (bizarre beliefs), hallucinations (seeing or hearing things that are not there), negative symptoms (social withdrawal, apathy) and disorganised behaviour. Medications known as antipsychotics are the main treatment but are not always very effective at helping with the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. CBTp has been suggested as a useful add‐on treatment to medication for people with mental illness, but evidence for its effectiveness for people with schizophrenia is uncertain. CBTp is usually an individual therapy but can also be delivered to a group of people, which may be more cost‐effective. It is important to find out if group CBTp for people with schizophrenia is effective and acceptable.

What did we do?

The Information Specialist of Cochrane Schizophrenia ran an electronic search of their specialised register up to 10 February 2021 for clinical trials that randomised group CBTp versus standard care or other psychosocial therapies (either group or individual) in people with schizophrenia.

What did we find?

We found 24 studies involving 1900 participants that met the review requirements and provided usable data. All studies compared group CBTp with standard care. Our evidence suggests there is no substantial difference between group CBTp and standard care or other psychosocial interventions in terms of numbers of participants leaving the study early. Group CBTp may be better than standard care or other psychosocial interventions for overall mental state for total symptoms of schizophrenia. Group CBTp seems to show no difference on positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia compared to standard care or other psychosocial interventions. Group CBTp seems to be better than standard care or other psychosocial interventions on global functioning. There were no real differences between treatment groups for number of participants hospitalised for group CBTp compared to standard care or other psychosocial interventions.

Conclusions

Group CBTp seems to be better than standard care or other psychosocial interventions on total symptoms of schizophrenia and global functioning.

What are the limitations of the evidence?

Studies with larger sample sizes and low risk of bias should be conducted. Longer‐term outcomes need to be addressed to establish whether any effect is transient or long‐lasting. Trials should improve their quality of data reporting.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis compared to standard care for schizophrenia.

| Group cognitive behavioural therapy compared to standard care and other psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia | ||||||

| Patient or population: people with schizophrenia Setting: inpatient and outpatient Intervention: group cognitive behavioural therapy Comparison: standard care | ||||||

| Outcomes | Anticipated absolute effects* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | № of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Risk with standard care | Risk with group cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis | |||||

| Clinically important change, shown as improved – as defined by individual studies | No data available | — | — | — | — | |

| Relapse | No data available | — | — | — | — | |

| Leaving the study early: for any reason – end of treatment | Study population | RR 1.22 (0.94 to 1.59) | 1267 (13 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,b | — | |

| 155 per 1000 | 195 per 1000 (144 to 259) | |||||

| Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS total) | The mean mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS total) was 0 | MD 3.73 lower (4.63 lower to 2.83 lower) | — | 1036 (12 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ Lowa,c | — |

| Days in hospital | No data available | — | — | — | — | |

| Quality of life: clinically important change – as defined by individual studies. | No data available | — | — | — | — | |

| Functioning: overall: global assessment of functioning – average endpoint score – end of treatment (GAF) | The mean functioning: overall: global assessment of functioning – average endpoint score – end of treatment (GAF) was 0 | MD 3.61 lower (6.37 lower to 0.84 lower) | — | 254 (5 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ Moderatea | — |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; GAF: Global Assessment of Functioning; MD: mean difference; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; RCT: randomised controlled trial; RR: risk ratio. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to high risk of performance bias for all studies and unclear selection bias for most studies. bDowngraded one level due to imprecision: confidence interval ranged from no difference to appreciable benefit with standard care. cDowngraded publication bias domain one level as the funnel plot on PANSS total outcome (Figure 1) was asymmetrical, increasing the risk for publication bias.

Background

Description of the condition

Schizophrenia is a disabling psychotic disorder with a point prevalence of between 2.8 and 4.5 per 1000 population (Charlson 2018; Tandon 2008), and an annual incidence of 15 per 100,000 (Jauhar 2022; Tandon 2008). It is characterised by delusions, hallucinations, negative symptoms and disorganised behaviour (APA 2013). Although prognosis can be debilitating for some people with a reduction in life expectancy (McCutcheon 2020), it is possible to achieve recovery (van Os 2009). Medication remains the mainstay of treatment (McCutcheon 2020; van Os 2009). However, not all patients respond well to medication and a significant number remain symptomatic (McCutcheon 2020; Mueser 2004). Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has been suggested as a useful add‐on to medication, particularly for those who show active symptoms (Bighelli 2018; Laws 2018; Turkington 2006). However, the evidence is far from conclusive (Jones 2004; Laws 2018). The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the UK has nevertheless recommended that CBT should be offered to all people with schizophrenia (NICE 2014).

Description of the intervention

CBT is a short‐term, problem‐focused, psychological intervention (Williams 2002), based on the cognitive model. This model was created by Aaron Beck, and was originally developed for depression (Beck 1979). It is based on the principle that psychological symptoms are linked to maladaptive patterns of thinking which, in turn, influence behaviours and emotions (Beck 1979). CBT is a structured, problem‐oriented approach (Kingdon 1998; Stuart 1998), and is based on collaborative empiricism, which is a goal‐driven process that is discussed and agreed by the clinician and the patient (Beck 1979). Several studies have shown that CBT is one of the most effective forms of treatment for mental health problems (Fordham 2021; Otto 2004). CBT has been suggested as a highly effective method of treatment for a variety of mental health disorders (Butler 2006; Fordham 2021).

The CBT model targeting symptoms of psychosis (CBTp) was developed in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Kingdon 1998). Individual studies have shown that cognitive‐based therapies can be used to manage schizophrenia (Gledhill 1998; Wykes 1999), although meta‐analyses show that the evidence is far from conclusive (Jones 2004; Jones 2018). Jones 2018 suggests that CBT for schizophrenia did not reduce relapse and readmission to hospital compared with standard care. However, it did reduce risk of staying in hospital (Jones 2018). It may be less effective than other forms of interventions such as mindfulness‐based psychoeducation (Mc Glanaghy 2021). Moreover, it appears that CBT for schizophrenia may be more useful in the short‐term, but less so in the medium‐ to long‐term (Jones 2004; Laws 2018). One recent meta‐analysis has shown that the effectiveness CBTp has improved for delusion over time (Sitko 2020).

While CBT for schizophrenia was mainly developed as an individual treatment (Lawrence 2006; Lecomte 2016), there has been some understanding of how a group approach may be more cost‐effective (Lawrence 2006). Group delivery of CBTp is an adaptation to the current method of individual CBTp, to allow groups of people to receive this treatment as a cohort. This model of delivery has the advantage of allowing a greater number of individuals to be treated by a single therapist, which has the potential of reducing costs while maintaining efficacy and allowing greater access to treatment (Lawrence 2006; Lecomte 2016). Other studies suggest that group CBTp has a positive impact on people with schizophrenia (Wykes 1999). In contrast, Barraclough 2006 concluded that group CBTp is effective for reducing hallucinations and delusions, but not as effective for reducing the negative thoughts and feelings the person with schizophrenia may have.

How the intervention might work

CBT for psychosis could work by giving people with schizophrenia skills and tools to help them cope with their psychotic symptoms (Morrison 2010; Spencer 2020). Moreover, it can help patients identify key cognitions, behaviours, emotions and images that are fundamental to their symptoms (Morrison 2010; Spencer 2020). By identifying maladaptive thoughts, emotions and behaviours, the person with schizophrenia is, potentially, in a better position to change them. It is also possible that working on a CBTp model can help instil hope in recovery, reduce distress and improve quality of life (Morrison 2010). The converse could also be true. Greater understanding of maladaptive patterns of thinking could equally instil feelings of helplessness, loss, grief and distress with subsequent repercussions on quality of life (Hesdon 2004).

More specifically, CBT delivered by group for people with schizophrenia could have the additional effect of being applied in a group setting, thus indirectly improving social competence in a population who traditionally have been socially isolated and excluded (Lawrence 2006; Lecomte 2016). Also, shared experience of tackling symptoms can be very powerful in a group setting. There can also be an opportunity of modelling positive behaviours and coping strategies, and also enhance motivation by observational learning (Lecomte 2016).

Why it is important to do this review

Group CBT for psychosis could be both effective and cost‐effective and a possible alternative to individual CBT. The UK National Health Service (NHS) has suggested that people with schizophrenia should receive individual therapy sessions (Bechdolf 2004). Due to the lack of resource this is unlikely to happen – and, perhaps less so as more evidence emerges as to the little or no benefits – and even drawbacks – of CBT for people with schizophrenia when compared with other psychological therapies (Jones 2010). However, the group experience may have benefits that individual therapy simply cannot provide and therefore, a review of best evidence is indicated. Group CBTp can be an important part of a stepped care model for the treatment of schizophrenia spectrum disorder (Kopelovich 2019).

This review is part of a series of Cochrane Reviews aiming to provide a comprehensive overview of the evidence for the effectiveness of CBT for people with schizophrenia. The protocol of this review was published in 2012 (Guaiana 2012).

Objectives

To investigate efficacy and acceptability of group CBT applied to psychosis compared with standard care or other psychosocial interventions, for people with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All relevant randomised controlled trials (RCT). If a trial was described as 'double blind' but implied randomisation, we included the trial in a sensitivity analysis (see Sensitivity analysis). We excluded quasi‐randomised studies, such as those allocating by alternate days of the week. Where people were given additional treatments within group CBT, we included the data if the adjunct treatment was evenly distributed between groups and it was only the group CBT that was randomised.

Types of participants

Adults aged 16 years and over, with schizophrenia or related disorders, including schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder and delusional disorder by any means of diagnosis. We did not exclude trials that included participants who had a concurrent secondary diagnosis of another psychiatric disorder but we excluded trials that included participants who had a concomitant medical illness. We only included studies where at least 80% of participants had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.

We were interested in ensuring that information was relevant to the current care of people with schizophrenia so proposed to clearly highlight the current clinical state (acute, early postacute, partial remission, remission) and stage (prodromal, first episode, early illness, persistent), and whether the studies primarily focused on people with particular problems (e.g. negative symptoms, treatment‐resistant illnesses).

Types of interventions

1. Group cognitive behavioural therapy for schizophrenia (CBTp)

Defined as a structured psychotherapeutic intervention, carried out in any group setting, and based on the CBT model applied to psychosis (Beck 1979). The key components are:

a structured approach to each session;

homework assignments on monitoring thoughts and target symptoms;

examination of evidence for and against a distressing thought;

encouragement in developing alternatives in thinking about a belief;

exploration of the relationship between thoughts, emotions and behaviours;

teaching techniques to cope with target symptoms, such as delusions, hallucinations and negative symptoms (Kingdon 2005).

Despite the above criteria, it is often difficult to define CBTp precisely. CBTp interventions that do not meet the key component criteria listed above were considered 'less defined CBTp', while CBTp interventions that met the same criteria were defined as CBTp. We aimed to perform a sensitivity analysis excluding studies where less‐defined criteria were applied to investigate whether the definition resulted in a difference in outcomes.

CBT for schizophrenia could be applied as a stand‐alone intervention or in combination with medication.

2. Standard care

We included interventions described as 'treatment as usual' and wait‐list control interventions as standard care. This is the care participants would normally receive in a standard mental health service and could consist of antipsychotic medication treatment alone or a combination of medication and additional psychosocial interventions of any type (other than group CBTp).

3. Other interventions

As a comparator we also considered other psychosocial interventions of any type.

Types of outcome measures

We aimed to divide all outcomes into short‐term (less than six months), medium‐term (seven to 12 months) and long‐term (over one year).

Primary outcomes

1. Global state

1.1 Clinically important change, shown as improved – as defined by individual studies.

Secondary outcomes

1. Global state

1.1 Any change – as defined by individual studies. 1.2 Relapse. 1.3 Average endpoint or change score on global state scale.

2. Leaving the study early

2.1 For any reason. 2.2 For specific reason.

3. Mental state

3.1 Overall

3.1.1 Clinically important change overall mental state – as defined by individual studies. 3.1.2 Any change in overall mental state – as defined by individual studies. 3.1.3 Average endpoint or change score on mental state scale.

3.2 Specific

3.2.1 Clinically important change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive or negative) – as defined by individual studies. 3.2.2 Any change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive or negative). 3.2.3 Depression. 3.2.4 Average endpoint or change scores on positive or negative symptom scales.

4. Compliance

4.1 Taking drug treatment. 4.2 Adherence to non‐drug treatments.

5. Adverse effects/events

5.1 At least one adverse effect/event. 5.2 Incidence of specific adverse effects. 5.3 Average endpoint or change scores on adverse effect scales. 5.4 Dependency. 5.5 Death: suicide or natural causes.

6. Service utilisation outcomes

6.1 Hospital admission. 6.2 Days in hospital.

7. Quality of life

7.1 Clinically important change – as defined by individual studies. 7.2 Any change – as defined by individual studies. 7.3 General impression of carer/rater or family member. 7.4 Average endpoint/change score on quality of life scales.

8. Functioning – social and living skills

8.1 Clinically important change in functioning – as defined by individual studies. 8.2 Any change in functioning – as defined by individual studies. 8.3 Average endpoint/change score, on social skills/functioning scales. 8.4 Occupational status.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

Cochrane Schizophrenia Group's Study‐Based Register of Trials

On 8 January 2018, 28 January 2019, 7 May 2020 and 10 February 2021, the information specialist searched the register using the following search strategy:

*Cogniti* in Intervention Field of STUDY

In such a study‐based register, searching the major concept retrieves all the synonyms and relevant studies because all the studies have already been organised based on their interventions and linked to the relevant topics (Roberts 2021; Shokraneh 2017; Shokraneh 2021). This allows rapid and accurate searches that reduce waste in the next steps of systematic reviewing (Shokraneh 2019).

Following the methods from Cochrane (Lefebvre 2019), this register is compiled by systematic searches of major resources (CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, ClinicalTrials.Gov, ISRCTN, PsycINFO, PubMed, World Health Organization (WHO) ICTRP) and their monthly updates, ProQuest Dissertations and Theses A&I and its quarterly update, handsearches, grey literature and conference proceedings (Shokraneh 2020; see Schizophrenia Group's website at schizophrenia.cochrane.org/register-trials). There is no language, date, document type or publication status limitations for inclusion of records into the register.

Searching other resources

1. Personal communication

We contacted experts in the field by email or mail to find potential suitable studies for the review, or to find out whether there are studies in progress.

See Table 2 for details of how authors of the studies awaiting classification were contacted.

1. Contact of authors of studies awaiting classification.

| Study name | Contacted | Replied | Provided data | Notes |

| Brenner 1987 | No | No | No | Could not find author's contact details |

| Chung 2001 | Yes | No | No | — |

| Classen 1993 | No | No | No | — |

| Klingberg 2001 | Yes | No | No | — |

| Kraemer 1987 | No | No | No | Could not find author's contact details |

| McLeod 2007 | Yes | No | No | — |

| Shafiei 2011 | No | No | No | — |

2. Reference checking

Finally, we checked the reference lists of the included studies, previous systematic reviews written in English, Italian, French, German, Spanish, Chinese for published reports and citations of unpublished research. We checked the references of all included studies via Science Citation Index for articles which have cited the included study.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Five review authors (MA, FT, IE, CZ, WL) independently inspected citations from the searches and identified relevant abstracts. Where disputes arose, we acquired the full report for more detailed scrutiny. We then obtained full reports of the abstracts meeting the review criteria and the same five review authors inspected them. Where it was not possible to resolve disagreement by discussion, we attempted to contact the study authors for clarification.

Data extraction and management

1. Extraction

Teams of two review authors (from MA, FT, GG, IE, CZ, WL) independently extracted data from all included studies. We discussed any disagreements, documented decisions and, if necessary, contacted study authors for clarification. With any remaining problems, another member of the review group (AP) helped clarify issues and we documented the final decisions. Whenever possible, we extracted data presented only in graphs and figures but we only included the data if two review authors independently had the same result. We attempted to contact authors through an open‐ended request to obtain missing information or for clarification whenever necessary. If studies were multicentre, where possible, we extracted data relevant to each component centre separately.

2. Management

2.1 Forms

We used Covidence to select and extract data from the studies.

2.2 Scale‐derived data

We included continuous data from rating scales only if:

the psychometric properties of the measuring instrument had been described in a peer‐reviewed journal (Marshall 2000); and

the measuring instrument had not been written or modified by one of the trialists for that particular trial.

Ideally, the measuring instrument should have either been a self‐report or completed by an independent rater or relative (not the therapist). We realise that this is not often reported clearly, but we noted if this was the case or not.

2.3 Endpoint versus change data

There are advantages of both endpoint and change data. Change data can remove a component of between‐person variability from the analysis. However, calculation of change needs two assessments (baseline and endpoint), which can be difficult in unstable and difficult‐to‐measure conditions such as schizophrenia. We decided primarily to use endpoint data, and only use change data if the former were not available. We combined endpoint and change data in the analysis as we used mean differences (MD) rather than standardised mean differences (SMD) throughout (Higgins 2022).

2.4 Skewed data

Continuous data on clinical and social outcomes are often not normally distributed. To avoid the problem of applying parametric tests to non‐parametric data, we aimed to apply the following standards to all data before inclusion:

standard deviations (SDs) and means were reported in the paper or obtainable from the authors;

when a scale started from the finite number zero, the SD, when multiplied by two, is less than the mean (as otherwise the mean is unlikely to be an appropriate measure of the centre of the distribution) (Altman 1996);

if a scale started from a positive value (such as the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) which can have values from 30 to 210), we modified the calculation described above to take the scale starting point into account. In these cases, skew was present if 2 SD > (S – Smin), where S is the mean score and Smin is the minimum score. Endpoint scores on scales often have a finite start and endpoint and these rules can be applied. When continuous data are presented on a scale that includes a possibility of negative values (such as change data), it is difficult to determine whether data are skewed or not. We entered skewed data from studies of fewer than 200 participants into additional tables rather than into an analysis. Skewed data pose less of a problem when using means if the sample size is large, and therefore, we entered such data into the analyses.

2.5 Common measure

To facilitate comparison between trials, we intended to convert variables that could be reported in different metrics, such as days in hospital (mean days per year, per week or per month) to a common metric (e.g. mean days per month).

2.6 Conversion of continuous to binary

Where possible, we attempted to convert outcome measures to dichotomous data. This could be done by identifying cut‐off points on rating scales and dividing participants accordingly into 'clinically improved' or 'not clinically improved'. It is generally assumed that if there is a 50% reduction in a scale‐derived score such as the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS; Overall 1962) or the PANSS (Kay 1986), this could be considered as a clinically significant response (Leucht 2005a; Leucht 2005b). If data based on these thresholds were not available, we used the primary cut‐off presented by the original authors.

2.7 Direction of graphs

Where possible, we entered data such that the area to the left of the line of no effect indicated a favourable outcome for group CBT. Where keeping to this made it impossible to avoid outcome titles with clumsy double‐negatives (e.g. 'not improved'), we reported data where the left of the line indicated an unfavourable outcome. We noted this in the relevant graphs.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Teams of two review authors (from MA, FT, GG, IE, CZ, WL) independently assessed risk of bias using criteria described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions to assess trial quality (Higgins 2022). This set of criteria is based on evidence of associations between overestimates of effect and high risk of bias of the article such as sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data and selective reporting.

If the raters disagreed, we made the final rating by consensus, with the involvement of another member of the review group (AP). Where there were inadequate details of randomisation and other characteristics of trials provided, we contacted the study authors to request further information. We reported non‐concurrence in quality assessment, but if disputes arose as to which category a trial was to be allocated, we resolved this by discussion.

We noted the level of risk of bias in both the text of the review and in the risk of bias summary and risk of bias graph (Figure 2; Figure 3).

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Measures of treatment effect

1. Binary data

For binary outcomes, we calculated a standard estimation of the risk ratio (RR) and its 95% confidence interval (CI). It has been shown that RR is more intuitive than odds ratios (Boissel 1999), and that odds ratios tend to be interpreted as RR by clinicians (Deeks 2000).

2. Continuous data

For continuous outcomes, we estimated MD between groups with 95% CIs. We preferred not to calculate effect size measures (SMD). However, if studies used scales of very considerable similarity, we presumed there was a small difference in measurement, and we calculated effect size and transformed the effect back to the units of one or more of the specific instruments.

Unit of analysis issues

1. Cluster trials

Studies increasingly employ 'cluster randomisation' (such as randomisation by clinician or practice) but analysis and pooling of clustered data poses problems. First, authors often fail to account for intraclass correlation in clustered studies, leading to a 'unit of analysis' error (Divine 1992), whereby P values are spuriously low, CIs unduly narrow and statistical significance overestimated. This causes type I errors (Bland 1997; Gulliford 1999).

Where primary studies did not account for clustering, we presented data in a table, with a * symbol to indicate the presence of a probable unit of analysis error. We sought to contact first authors of studies to obtain intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) for their clustered data and to adjust for this by using accepted methods (Gulliford 1999). Where clustering was incorporated into the analysis of primary studies, we presented these data as if from a non‐cluster randomised study, but adjust for the clustering effect.

We sought statistical advice and have been advised that the binary data as presented in a report should be divided by a 'design effect'. This is calculated using the mean number of participants per cluster (m) and the ICC (design effect = 1 + (m – 1) × ICC) (Donner 2002). If the ICC was not reported, we assumed it to be 0.1 (Ukoumunne 1999).

If cluster studies had been appropriately analysed taking into account ICCs and relevant data documented in the report, synthesis with other studies would be possible using the generic inverse variance technique.

2. Cross‐over trials

A major concern of cross‐over trials is the carry‐over effect. It occurs if an effect (e.g. pharmacological, physiological or psychological) of the treatment in the first phase is carried over to the second phase. As a consequence, on entry to the second phase the participants can differ systematically from their initial state despite a wash‐out phase. For the same reason, cross‐over trials are not appropriate if the condition of interest is unstable (Elbourne 2002). As both effects are very likely in severe mental illness, we only used data from the first phase of cross‐over studies.

3. Studies with multiple treatment groups

Where a study involved more than two treatment arms, if relevant, we presented the additional treatment arms in comparisons. If data were binary, we simply added and combined them in the two‐by‐two table. If data were continuous, we combined data following the formula in Section 7.7.3.8 (Combining groups) of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022). Where the additional treatment arms were not relevant, we did not reproduce the data but listed them in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Dealing with missing data

1. Overall loss of credibility

At some degree of loss of follow‐up, data must lose credibility (Xia 2009). We chose that, for any particular outcome, should more than 50% of data be unaccounted for, we did not reproduce these data or use them within analyses, except for the outcome leaving the study early. However, if more than 50% of those in one arm of a study were lost, but the total loss was less than 50%, we marked such data with (*) to indicate that such a result may well be prone to bias.

2. Binary

In the case where attrition for a binary outcome was between 0% and 50% and where these data were not clearly described, we presented the data on a 'once‐randomised‐always‐analyse' basis (an intention‐to‐treat analysis). Those leaving the study early were all assumed to have the same rates of negative outcome as those who completed, with the exception of the outcome of death and adverse effects. For these outcomes, we used the rate of those who stayed in the study – in that particular arm of the trial – for those who did not. We aimed to undertake a sensitivity analysis to test how prone the primary outcomes were to change when comparing 'completer' data only with the intention‐to‐treat analysis using the above assumptions.

3. Continuous

3.1 Attrition

In the case where attrition for a continuous outcome was between 0% and 50% and completer‐only data are reported, we reproduced these.

3.2 Standard deviations

If SDs were not reported, we first tried to obtain the missing values from the study authors. If not available, where there were missing measures of variance for continuous data, but an exact standard error (SE) and CIs were available for group means, and either a P value or a t value were available for differences in mean, we calculated them according to the rules described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022): when only the SE was reported, we calculated SDs using the formula SD = SE × square root (n). Sections 7.7.3 and 16.1.3 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions present detailed formulae for estimating SDs from P values, t or F values, CIs, ranges or other statistics (Higgins 2022). If these formulae did not apply, we calculated the SDs according to a validated imputation method which is based on the SDs of the other included studies (Furukawa 2006). Although some of these imputation strategies could introduce error, the alternative would be to exclude a given study’s outcome and thus to lose information. Nevertheless, we examined the validity of the imputations in a sensitivity analysis excluding imputed values.

3.3 Last observation carried forward

We anticipated that some studies would use the method of last observation carried forward (LOCF) within the study report. As with all methods of imputation to deal with missing data, LOCF introduces uncertainty about the reliability of the results (Leucht 2007). Therefore, where LOCF data had been used in the trial, if less than 50% of the data have been assumed, we reproduced these data and indicated that they were the product of LOCF assumptions.

Assessment of heterogeneity

1. Clinical heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge clinical heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying people or situations that we had not predicted. When such situations or participant groups arose, we discussed them fully in the text.

2. Methodological heterogeneity

We considered all included studies initially, without seeing comparison data, to judge methodological heterogeneity. We simply inspected all studies for clearly outlying methods that we had not predicted. When such methodological outliers arose, we discussed them fully in the text.

3. Statistical heterogeneity

3.1 Visual inspection

We visually inspected graphs to investigate the possibility of statistical heterogeneity.

3.2 Employing the I2 statistic

We investigated heterogeneity between studies by considering the I2 statistic alongside the Chi2 P value. The I2 statistic provides an estimate of the percentage of inconsistency thought to be due to chance (Higgins 2003). The importance of the observed value of I2 statistic depends on magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from Chi2 test, or a CI for I2 statistic). We interpreted an I2 statistic estimate of 50% or greater accompanied by a statistically significant Chi2 statistic as evidence of substantial levels of heterogeneity (Higgins 2022). When there were substantial levels of heterogeneity in the primary outcome, we explored reasons for it (Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity).

Assessment of reporting biases

Reporting biases arise when the dissemination of research findings is influenced by the nature and direction of results (Egger 1997). These are described in Chapter 10 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022). We are aware that funnel plots may be useful in investigating reporting biases but are of limited power to detect small‐study effects. We did not use funnel plots for outcomes where there were 10 or fewer studies, or where all studies were of similar sizes. In other cases, where funnel plots were possible, we aimed to seek statistical advice in their interpretation.

Data synthesis

We understand that there is no closed argument for preference for use of fixed‐effect or random‐effects models. The random‐effects method incorporates an assumption that the different studies are estimating different, yet related, intervention effects. This often seems to be true to us and the random‐effects model takes into account differences between studies even if there is no statistically significant heterogeneity. However, there is a disadvantage to the random‐effects model. It puts added weight onto small studies, which often are the most biased ones. Depending on the direction of effect these studies can either inflate or deflate the effect size. We used the random‐effects model for all analyses. However, readers are able to choose to inspect the data using the fixed‐effect model.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

1. Subgroup analyses – primary outcomes

We note that subgroup analyses are often exploratory in nature and should be interpreted with caution. First, because it often involves multiple analyses, this can lead to false positive results. Second, these analyses lack power and would more likely result in false‐positive results. Keeping in mind the above reservations, we aimed to perform the following subgroup analyses solely for the primary outcome.

Number of sessions offered (six sessions or fewer, seven to 12 sessions, more than 12 sessions).

People at their first episode of schizophrenia versus those with previous episodes of schizophrenia.

Efficacy in the short‐term (six months or less) versus efficacy in the long‐term (over six months).

1.2 Clinical state, stage or problem

We proposed to undertake this review and provide an overview of the effects of group CBT for people with schizophrenia in general. In addition, we tried to report data on subgroups of people in the same clinical state, stage and with similar problems.

2. Investigation of heterogeneity

If inconsistency was high, we reported this. First, we investigated whether data had been entered correctly. Second, if data were correct, we visually inspected the graph and remove outlying studies to see if homogeneity was restored. Where unanticipated clinical or methodological heterogeneity were obvious, we simply stated hypotheses regarding these for future reviews or versions of this review. We did not anticipate undertaking analyses relating to these.

Sensitivity analysis

We planned the sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome only.

1. Implication of randomisation

We aim to include trials in a sensitivity analysis if they were described in some way as to imply randomisation. For the primary outcomes, we aimed to include these studies and if there was no substantive difference when the implied randomised studies are added to those with better descriptions of randomisation, then we used all data from these studies.

2. Assumptions for lost binary data

Where assumptions had to be made regarding people lost to follow‐up (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings of the primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discuss them but continued to employ our assumption.

Where assumptions had to be made regarding missing SDs data (see Dealing with missing data), we compared the findings on primary outcomes when we used our assumption compared with completer data only. We aimed to undertake a sensitivity analysis to test how prone results were to change when comparing 'completer' data only with the imputed data using the above assumption. If there was a substantial difference, we reported results and discussed them but continued to employ our assumption.

3. Risk of bias

We analysed the effects of excluding trials that were at high risk of bias across one or more of the domains of randomisation (implied as randomised with no further details available) allocation concealment, blinding and outcome reporting for the meta‐analysis of the primary outcome. If the exclusion of trials at high risk of bias did not substantially alter the direction of effect or the precision of the effect estimates, then we included the data from these trials in the analysis.

4. Imputed values

We undertook a sensitivity analysis to assess the effects of including data from trials where we used imputed values for ICC in calculating the design effect in cluster randomised trials.

If there were substantial differences in the direction or precision of effect estimates in any of the sensitivity analyses listed above, we did not pool data from the excluded trials with the other trials contributing to the outcome, but presented them separately

5. Fixed‐effect and random‐effects models

We synthesised all data using a random‐effects model; however, we planned to use a fixed‐effect model to evaluate whether the greater weights assigned to larger trials with greater event rates altered the significance of the results compared with the more evenly distributed weights in the random‐effects model (see Differences between protocol and review).

6. Dropout rates

We excluded studies with dropout rates of more than 50%.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We used the GRADE approach to interpret findings (Schünemann 2021) and use the GRADE profiler (GRADE Profiler) to import data from Review Manager 5 (Review Manager 2014) to prepare the summary of findings table (Table 1).

The summary of findings table provides outcome‐specific information concerning the overall certainty of the evidence from each included study in the comparison, the magnitude of effect of the interventions examined and the sum of available data on all outcomes we considered important to patient‐care and decision‐making.

In the protocol, we planned to use the following outcome measures for the summary of findings table.

Global state – clinically significant improvement in global state – as defined by each of the studies.

Leaving the study early.

-

Mental state.

Clinically significant response in mental state – as defined by each of the studies.

Relapse.

-

Service utilisation outcomes.

Hospital admission.

Days in hospital.

Quality of life.

Significant change in quality of life – as defined by each of the studies.

However, we selected the following main outcomes for inclusion in the summary of findings table (see Differences between protocol and review for reasons):

Clinically important change, shown as improved – as defined by individual studies.

Relapse.

Leaving the study early: for any reason.

Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS total).

Days in hospital.

Quality of life: clinically important change – as defined by individual studies.

Functioning: overall: global assessment of functioning – average endpoint score – end of treatment (Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF)).

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies; Characteristics of studies awaiting classification; Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

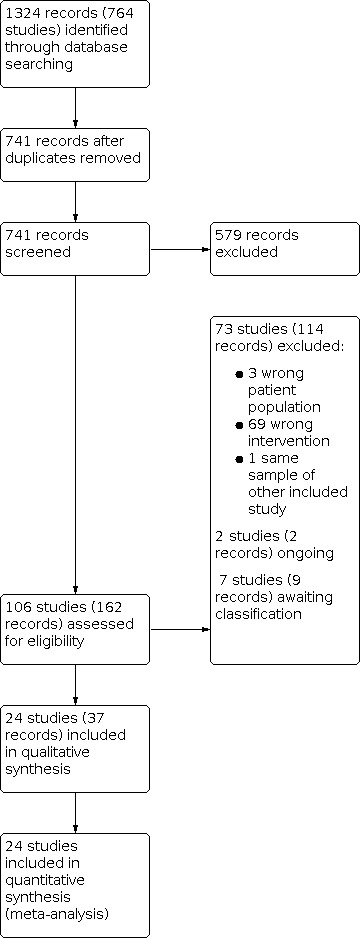

Initially, we identified 1324 references (764 studies) through database searching. After removing duplicates, we screened titles and abstracts of 741 records and excluded 579 records that were obviously irrelevant. We retrieved full‐text copies of the remaining 162 records (106 studies). We excluded 114 records (73 studies) overall. We excluded the studies for a variety of reasons (see Figure 4 for more information). In particular, we excluded 69 studies because the intervention was not group CBTp. We included 37 references referring to 24 studies in the qualitative and quantitative synthesis. We classified seven studies as awaiting classification since we could not obtain useful data for the analysis (see Table 2 for more information). Two studies are ongoing. The literature search was last updated in February 2021. See Figure 4 for PRISMA flow diagram.

4.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 24 studies in this systematic review. All the studies were published trials except for Jones 2014 (a PhD thesis dissertation).

1. Design and duration

Most RCTs had two arms except for Granholm 2020 and Mortan Sevi 2020, which included three arms. However, we just included two arms for those studies, as the third arm was not relevant to the outcomes.

2. Participants

All studies included participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder, or both.

All studies randomised participants aged at least 16 years or older, but the age ranges of participants varied: two studies recruited older participants (over 42 years) (Granholm 2007; Granholm 2013); the remaining studies recruited people between the ages of 16 and 65 years.

3. Size

Overall, the studies included 1900 participants in active treatment arms. Of these, 949 were randomised to various forms of group CBTp. Of the remaining 951 participants, 495 were randomised to standard care, 228 to medication alone, 147 to supportive therapy, 48 to a psychoeducational group, 17 to mobile device control and 16 to wait‐list control. The mean sample size for both arms was about 40 participants (range six to 73).

4. Setting

Five studies recruited participants from multiple centres (Barrowclough 2006; Chadwick 2016; Granholm 2013; Penn 2009; Wykes 2005). The remaining studies recruited participants from one centre only. All studies were conducted in a single nation: the USA (Daniels 1998; Granholm 2007; Granholm 2013; Granholm 2014; Granholm 2020; Penn 2009), China (Deng 2014; Guan 2016; Li 2013a; Li 2013b; Qi 2012; Qu 2016; Shen 2007; Shi 2015; Song 2012; Song 2014; Tao 2015; Zhou 2015), the UK (Barrowclough 2006; Chadwick 2016; Wykes 2005), Turkey (Mortan Sevi 2020), and Germany (Bechdolf 2004).

Three studies enrolled both inpatients and outpatients (Granholm 2013; Song 2014; Wykes 2005). Eleven studies recruited inpatients only (Barrowclough 2006; Bechdolf 2004; Deng 2014; Guan 2016; Li 2013a; Li 2013b; Qi 2012; Qu 2016; Shi 2015; Song 2012; Zhou 2015). Nine studies recruited outpatients only (Chadwick 2016; Daniels 1998; Granholm 2007; Granholm 2020; Jones 2014; Mortan Sevi 2020; Penn 2009; Shen 2007; Tao 2015).

5. Interventions and comparators

For this review, we defined group CBTp as a group intervention targeting psychotic symptoms, based on the cognitive model. In group CBTp, people work collaboratively on coping with distressing hallucinations, analysing evidence for their delusions, problem‐solving skills and social skills. As for concomitant medication, three studies did not report whether participants received any medication (Daniels 1998; Granholm 2020; Song 2012), while in the remaining 15 studies, all or most of the participants received concomitant medication.

The comparator interventions (control psychological therapies and medications) described in the studies can be considered the treatment that a person with schizophrenia would usually receive in a standard mental health service. For this reason, we grouped the comparator interventions together, and we considered them as "standard care" for analyses.

One study compared group CBTp to a control psychoeducational group (Bechdolf 2004). Twelve studies compared group CBTp to standard care (Barrowclough 2006; Chadwick 2016; Deng 2014; Granholm 2007; Li 2013a; Mortan Sevi 2020; Qu 2016; Song 2012; Song 2014; Tao 2015; Wykes 2005; Zhou 2015). Two studies compared group CBTp with a wait‐list control (Daniels 1998; Jones 2014). Three studies compared group CBTp to a form of supportive therapy (Granholm 2013; Granholm 2014; Penn 2009). Five studies compared group CBTp to medication alone (Guan 2016; Li 2013b; Qi 2012; Shen 2007; Shi 2015).

Two studies were three‐arm trials. Mortan Sevi 2020 compared group CBTp with standard care and a modified CBT called COPE‐CBT, while Granholm 2020 compared group CBTp with a mobile‐assisted group CBTp and an electronic device control. However, we excluded the third arms (COPE‐CBT for Mortan Sevi 2020 and electronic device control for Granholm 2020) from the analysis as we deemed them as not part of a CBTp treatment.

6. Outcomes

6.1 General

All studies provided efficacy data (either as dichotomous or as continuous outcome) that could be entered into a meta‐analysis.

The studies used a variety of scales to assess clinical response, functioning and quality of life.

Thirteen studies also reported the number of participants leaving the study early, due to any reason, while the remaining studies did not report this outcome (Barrowclough 2006; Bechdolf 2004; Chadwick 2016; Deng 2014; Granholm 2007; Granholm 2013; Granholm 2014; Li 2013a; Mortan Sevi 2020; Penn 2009; Shi 2015; Tao 2015; Wykes 2005).

6.2 Outcome scales providing useable data

6.2.1 Mental state

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay 1987)

The PANSS was developed from the BPRS and the Psychopathology Rating Scale. It is used to evaluate the positive, negative and general symptoms in schizophrenia. The scale has 30 items, and each item is rated on a 7‐point scoring system varying from 'absent' (1) to 'extreme' (7). Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Overall 1962)

The BPRS is a scale used to measure the severity of psychiatric symptoms, including psychotic symptoms. The scale usually has 18 items (depending on the version the number of items varies from 16 to 24), and each item is rated on a 7‐point scoring system varying from 'not present' (1) to 'extremely severe' (7). Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS) (Haddock 1999)

The PSYRATS is a medical scale used to measure symptom severity in schizophrenia. It consists of two scales rating auditory hallucinations and delusions. It has 11 items related to auditory hallucinations (frequency, duration, location, loudness, beliefs regarding origin of voices, amount of negative content of voices, degree of negative content of voices, amount of distress, intensity of distress, disruption to life caused by voices and controllability of voices) and six items related to delusions (amount of preoccupation with delusions, duration of preoccupation with delusions, conviction, amount of distress, intensity of distress and disruption to life caused by beliefs). Each symptom is rated on a scale from 0 to 4. Minimum score for PSYRATS is 0 and maximum score is 68. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Symptom Checklist‐90‐Revised (SCL‐90‐R) (Derogatis 1992)

This scale is used to evaluate a broad range of psychological problems and symptoms of psychopathology. It consists of 90 items and yielding nine scores along primary symptom dimensions and three scores among global distress indices. The primary symptom dimensions are: somatisation, obsessive‐compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism and a category of "additional items". The three indices are global wellness index, hardiness and symptom free. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS) (Andreasen 1991)

The SAPS is used to measure the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. It consists of four subscales that evaluate four different aspects of positive symptoms: hallucinations, delusions, bizarre behaviour and positive formal thought disorder. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS) (Andreasen 1991)

The SANS is used to measure the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. It consists of five subscales that evaluate five different aspects of negative symptoms: alogia, affective blunting, avolition‐apathy, anhedonia‐asociality and attentional impairment. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Auditory Hallucinations Rating Scale (AHRS) (Hoffman 2003)

The AHRS is an English‐language structured tool developed to measure the effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in hallucinating people with schizophrenia. It has seven items. It aims at assessing hallucination frequency, number of distinct speaking voices, perceived loudness, vividness, attentional salience (the degree to which hallucinations captured the attention of the patient), length of hallucinations (single words, phrases, sentences, or extended discourse) and degree of distress. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond 1983)

The HADS is used to detect states of depression and anxiety in the setting of a hospital medical outpatient clinic. The anxiety and depressive subscales are also measures of severity of the emotional disorder. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAMD) (Hamilton 1967)

The HAMD is 17‐item scale used to assess the severity of depression. Each item is rated on 3‐ or 5‐point scale. Higher score indicates severe depression. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS) (Hamilton 1959)

The HARs is 14‐item scale used to assess the severity of anxiety. Each item was rated on 5‐point scale. Higher score indicates severe anxiety. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Beck Depression Inventory‐II (BDI‐II) (Beck 1996)

The BDI‐II scale is a 21‐item, self‐report questionnaire which measures the severity of depressive symptoms. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Montgomery‐Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery 1979)

The MADRS is a 10‐item, self‐report questionnaire that measures the severity of depressive symptoms. It is designed to be sensitive to change resulting from antidepressant therapy. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1990)

The BAI is a 21‐item self‐report questionnaire that measures the intensity of depressive symptoms. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SAD) (Watson 1969)

The SAD is a 280‐item true/false scale that measures aspects of social anxiety including distress, discomfort, fear and avoidance. Higher scores indicate more pronounced symptomatology.

6.2.2. Quality of life

Modular System for Quality of Life (MSQoL) (Pukrop 2000)

The MSQoL is an integrative questionnaire that consists of one "G‐factor" (life in general) and six specific dimensions (physical health, vitality, psychosocial relationships, material resources, affect, leisure time). This basic structure represents a core module measured by 47 items. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

Quality of Life Scale (QLS) (Heinrichs 1984)

The QLS is a 21‐item scale based on a semi‐structured interview designed to assess deficit symptoms in interpersonal relations, instrumental role, intrapsychic foundations, common object and activities. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

WHOQOL‐BREF (WHOQOL Group 1996)

The WHOQOL‐BREF is an abbreviated version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment Instrument (WHOQOL‐100; WHOQOL Group 1994). It is a 26‐item quality of life assessment consisting of four domains: Physical, Psychological, Social relationships and Environment. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

General Quality of Life Inventory‐74 (GQOLI‐74) (Lu 2009)

The GQOLI‐74 was developed based on the WHOQOL‐100 and was modified for use in a Chinese population. The inventory comprises 74 items that can be grouped into 20 facets and covers the following four domains: Physical well‐being (sleep and energy, pain and physical discomfort, eating function, sexual function, daily living capability); Psychological well‐being (psychological distress, negative feelings, positive feelings, cognitive function, body image); Social well‐being (social support, interpersonal relationships, work and study capacity, recreational and leisure activities, marriage and family); and Material well‐being (housing situation, community services, living environment, financial situation). Patients’ responses are converted to scores on a 0 to 100 scale for each domain and each facet. Higher scores indicate better quality of life.

6.2.3 Social functioning

Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (APA 2000)

GAF rates the social, occupational and psychological functioning on a hypothetical continuum of mental health illness. The lowest scores are 1 to 10 corresponding to 'Persistent danger of severely hurting self or others OR persistent inability to maintain minimal personal hygiene OR serious suicidal act with clear expectation of death' and the highest scores are 91 to 100 corresponding to 'No symptoms, life's problems never seem to get out of hand, is sought out by others because of his or her many positive qualities'. Higher scores indicate better social functioning.

Social Behaviour Schedule (SBS) (Wykes 1986)

The SBS is a 30‐item scale which measures 21 different social behaviours and nine activities. Higher scores indicate worse social functioning.

Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (Birchwood 1990)

The SFS measures social role and behavioural functioning across seven basic areas of community functioning: social engagement, interpersonal behaviour, prosocial activities, recreation, independence and employment. Higher scores indicate better social functioning.

Independent Living Skills Survey (ILSS) (Wallace 2000)

The ILSS is a comprehensive, objective, performance‐focused measure of the basic functional living skills of individuals with severe and persistent mental illness to obtain a view of their community adjustment. Higher scores indicate better social functioning.

Personal and Social Performance Scale (PSP) (Morosini 2000)

This scale assesses functioning across four dimensions (socially useful activities, personal and social relationships, self‐care, disturbing and aggressive behaviours) rather than one global score. It is a revision of is a revision of the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS; APA 1994). Higher scores indicate better social functioning.

Inpatient Psychiatric Rehabilitation Outcome Scale (IPROS) (Li 1994)

The IPROS aims at objectively evaluating inpatient rehabilitation programmes. It has five subscales: performance in occupational therapy, daily activities, socialisation, personal hygiene and level of interest in external events. Evaluators (physicians or nurses) observe patients for one week before coding items on a 5‐point scale. Higher scores indicate worse social functioning.

Social Disability Screening Schedule (SDSS) (Liu 2005)

The SDSS scale is composed of 10 items, which is used to assess social function. Each item is scored from 0 = healthy or very minor defects to 2 = severe defect. Higher scores indicate worse social functioning.

Excluded studies

Overall, we excluded 73 studies from the systematic review (see Figure 4 and Characteristics of excluded studies table for more information).

Awaiting classification

We identified five studies awaiting classification (Brenner 1987; Chung 2001; Klingberg 2001; Kraemer 1987; McLeod 2007; see Studies awaiting classification table for details), as it was not possible to obtain data based on the title, abstract, full‐text or a combination of these. We tried to contact the authors of most of those studies to request data, but were unsuccessful. See Table 2 for details on the way we contacted authors.

Ongoing studies

The search of the Cochrane Schizophrenia Trial registry found two ongoing studies (IRCT 20180817040818N; NCT04144075; see Characteristics of ongoing studies table for more information).

Risk of bias in included studies

See Characteristics of included studies table, Figure 2, and Figure 3.

The overall methodological quality of the studies was medium to low; every study was judged as having high or unclear risk of bias in at least one domain (see Figure 2 and Figure 3 for summary graphs).

Allocation

We judged five studies that reported details of the randomisation procedure at low risk of bias (Bechdolf 2004; Guan 2016; Penn 2009; Song 2014; Zhou 2015). The remaining studies did not report details about the randomisation procedure, and so we judged them as having unclear risk of bias.

Barrowclough 2006, Granholm 2014, Penn 2009, and Wykes 2005 described measures to prevent participants or trial personnel from knowing the forthcoming allocation, and we judged them at low risk of bias. The remaining studies report no details on allocation concealment, and we judged them at unclear risk of bias.

Blinding

Given the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and personnel was not attainable. Therefore, we considered all studies at high risk of bias for the blinding of participants and personnel risk of bias.

Concerning detection bias, 10 studies specified that raters were blind to treatment allocation, and were at low risk of bias (Barrowclough 2006; Bechdolf 2004; Chadwick 2016; Daniels 1998; Granholm 2007; Granholm 2013; Granholm 2014; Granholm 2020; Penn 2009; Wykes 2005). Thirteen studies provided no information on blinding of raters, and were at unclear risk of bias (Deng 2014; Guan 2016; Li 2013a; Li 2013b; Mortan Sevi 2020; Qi 2012; Qu 2016; Shen 2007; Shi 2015; Song 2012; Song 2014; Tao 2015; Zhou 2015). One study clearly specified that it was not possible for the experimenter to be blind to the treatment allocation (Jones 2014). This could have created bias in assessment. Therefore, we judged it at high risk of bias.

Incomplete outcome data

Overall rate of participants leaving the study early was with group CBTp and standard care. All studies except for one (Daniels 1998) did not seem to have differences in attrition between the groups, and were at low risk of bias. Daniels 1998 showed contradictory information on the number of participants, mentioning 40 in the "Subjects" section and 20 on the "Treatment" section. We judged this study at high risk of bias.

Selective reporting

None of the studies had published protocols. Three studies did not report all the data, and were at high risk of bias (Daniels 1998; Granholm 2007; Granholm 2013). Daniels 1998 mentioned using PANSS as a screening tool for positive symptoms, but the author did not report the scores. Granholm 2007 reported some outcomes in unusable diagrams. Granholm 2013 did not report data on PANSS negative outcome result. The remaining studies showed no evidence of selective outcome reporting. We judged them at low risk of bias.

Other potential sources of bias

We found no evidence of other potential source of bias for all the included studies.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Primary outcome

1. Global state

1.1 Clinically important change, shown as improved

No studies reported global state: clinically important change – as defined by individual studies.

Secondary outcomes

1. Global state

1.1 Any change

No studies reported global state: any change – as defined by individual studies.

1.2 Relapse – end of treatment

No studies reported global change: relapse.

1.3 Average endpoint or change score on global state scale

No studies reported global change: average endpoint or change score on global state scale.

2. Leaving the study early

2.1 Leaving the study early: for any reason – end of treatment

There was no clear difference between CBTp and standard care and other psychosocial interventions for numbers of participants leaving the study early (RR 1.22, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.59; studies = 13, participants = 1267; I2 = 9%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.1).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 1: Leaving the study early: for any reason – end of treatment

The funnel plot based on this outcome was symmetrical, making the risk of publication bias low (Figure 5).

5.

Leaving the study early: for any reason – end of treatment.

2.2 Leaving the study early: for specific reason – end of treatment

No studies reported leaving the study early: for specific reason.

3. Mental state

3.1 Mental state: overall

3.1.1 Mental state: overall: clinically important change overall mental state – as defined by individual studies – end of treatment

No studies reported mental state: overall: clinically important change overall mental state – as defined by individual studies – end of treatment.

3.1.2 Mental state: overall: any change in overall mental state – as defined by individual studies

No studies reported mental state: overall: any change in overall mental state – as defined by individual studies.

3.1.3a Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS total, high = poor)

Results from PANSS total final score favoured group CBTp over standard care and other psychosocial interventions at the end of treatment (MD –3.73, 95% CI –4.63 to –2.83; studies = 12, participants = 1036; I2 = 5%; low‐certainty evidence; Analysis 1.2).

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 2: Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS total, high = poor)

The funnel plot based on this outcome was asymmetrical, increasing the risk for publication bias (Figure 1).

1.

Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS total, high = poor).

3.1.3b Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (BPRS total, high = poor)

Results from BPRS total final score favoured group CBTp over standard care and other psychosocial interventions at the end of treatment (MD –4.26, 95% CI –7.50 to –1.02; studies = 3, participants = 180; I2 = 65%; Analysis 1.3). Heterogeneity was high.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 3: Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (BPRS total, high = poor)

3.1.3c Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PSYRATS total, high = poor)

There was no clear difference between group CBTp and standard care and other psychosocial interventions on PSYRATS total scores at the end of treatment (MD –0.45, 95% CI –3.23 to 2.33; studies = 2, participants = 166; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 4: Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (PSYRATS total, high = poor)

3.1.3d Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (SCL‐90‐R, high = poor)

Results from SCL‐90‐R total final score favoured group CBTp over standard care and other psychosocial interventions at the end of treatment (MD –33.26, 95% CI –51.26 to –15.26; studies = 1, participants = 82; Analysis 1.5).

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 5: Mental state: overall: average endpoint score – end of treatment (SCL‐90‐R, high = poor)

3.2 Mental state: specific

3.2.1 Clinically important change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive or negative) – as defined by individual studies

No studies reported clinically important change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive or negative) – as defined by individual studies.

3.2.2 Any change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive or negative)

No studies reported any change in specific symptoms (e.g. positive or negative).

3.2.3a Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (BDI‐II, high = poor)

There was no clear difference between group CBTp and standard care and other psychosocial interventions on BDI‐II scores at the end of treatment (MD –0.46, 95% CI –3.29 to 2.37; studies = 5, participants = 229; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.14).

1.14. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 14: Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (BDI‐II, high = poor)

3.2.3b Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (HAMD, high = poor)

There was no clear difference between group CBTp and standard care and other psychosocial interventions on HAMD scores at the end of treatment (MD 0.80, 95% CI –2.26 to 3.86; studies = 1, participants = 65; Analysis 1.15).

1.15. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 15: Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (HAMD, high = poor)

3.2.3c Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (MADRS, high = poor)

Results from MADRS total final score favoured group CBTp over standard care and other psychosocial interventions at the end of treatment (MD –2.18, 95% CI –3.80 to –0.56; studies = 1, participants = 56; Analysis 1.16).

1.16. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 16: Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (MADRS, high = poor)

3.2.3d Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (HADS depression, high = poor)

There was no clear difference between group CBTp and standard care and other psychosocial interventions on HADS depression subscores at the end of treatment (MD –1.75, 95% CI –3.59 to 0.09; studies = 1, participants = 93; Analysis 1.17).

1.17. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 17: Mental state: specific: depression – average endpoint score – end of treatment (HADS depression, high = poor)

3.2.4a Mental state: specific: positive symptoms – average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS positive, high = poor)

Six studies included PANSS positive symptoms average endpoint scores (Bechdolf 2004; Li 2013b; Qi 2012; Shen 2007; Shi 2015; Tao 2015). However, they showed skewness and, therefore, were removed from the analysis (see Table 3 for more information). The analysis with the remaining studies showed that there was no clear difference between group CBTp and standard care and other psychosocial interventions (MD –0.45, 95% CI –1.30 to 0.40; studies = 8, participants = 539; I2 = 0%; Analysis 1.6).

2. Mental state: specific: positive symptoms – average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS positive, high = poor): studies with skewed data.

| Study ID | Intervention | Mean | SD | n |

| Bechdolf 2004 | CBTp group | 11.3 | 4.2 | 31 |

| Standard care | 11.4 | 4.5 | 40 | |

| Li 2013b | CBTp group | 10.1 | 3.9 | 60 |

| Standard care | 11.2 | 3.8 | 60 | |

| Qi 2012 | CBTp group | 11.62 | 5.27 | 30 |

| Standard care | 11.94 | 5.46 | 40 | |

| Shen 2007 | CBTp group | 7.36 | 0.621 | 28 |

| Standard care | 8.75 | 2.351 | 28 | |

| Shi 2015 | CBTp group | 7.96 | 3.12 | 56 |

| Standard care | 9.69 | 3.37 | 58 | |

| Tao 2015 | CBTp group | 8.44 | 1.95 | 59 |

| Standard care | 9.31 | 2.9 | 57 |

CBTp: cognitive behavioural therapy model targeting symptoms of psychosis; n: number of participants; PANSS: Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; SD: standard deviation.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Group cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) versus standard care, Outcome 6: Mental state: specific: positive symptoms – average endpoint score – end of treatment (PANSS positive, high = poor)

3.2.4b Mental state: specific: positive symptoms – average endpoint score – end of treatment (SAPS, high = poor)