Abstract

Many issues have emerged more clearly than before in multi-storey residential buildings during quarantine and lockdown caused by the global pandemic COVID-19. Among these problems is the deterioration in people’s mental and physical health inside the home caused by quarantine and closure. This deterioration is due to inadequate passive ventilation, natural lighting, and the lack of green open spaces in and around traditional multi-storey residential buildings. Also, one of the most severe problems is the airborne infection transmission from a positive covid-19 person to others due to the lack of control in the entrance of buildings against an infected person. In this paper, we modified the shape of a traditional multi-storey residential building. Using Design-Builder and Autodesk CFD software, we create a simulation to compare the amount of natural ventilation and lighting before and after modifying the building’s shape. This work aims to increase the passive ventilation and daylight inside the building. Also, to achieve the biophilic concept to provide open spaces for each apartment to improve the mental and physical health of the residents. In addition, it protects the building users from infection with the virus. Through this study, we found that passive ventilation and daylight achieved more efficiency in the building that we have modified in its shape, which led to a 38% reduction in energy consumption. In summary, these findings suggest that by modifying the mass of the traditional multi-storey residential building with open green spaces provided for each apartment, the natural connection with the inhabitants of the building was sufficiently provided. Moreover, all this will significantly help improve residents’ mental and physical state, and it will also help prevent the spread of various diseases inside the homes.

Keywords: Quarantine, Lockdown, Pandemic, Design-Builder, Computational fluid dynamics (CFD), Biophilic

Nomenclature

Abbreviation

- CFD

Computational fluid dynamics

- UGS

Urban green spaces

- IAQ

Indoor air quality

- IEQ

Indoor Environmental Quality

- DV

Dilution ventilation

- UVGI

Ultraviolet germicidal irradiation

- ACPH

Air changes per hour

- E

East

- W

West

Symbol

- mm

Millimeter

- m

Meter

- m2

Square meter

- km

Kilometer

- m/s

Meter per second

- °C

Celsius for temperature measurement

- kWh

kilowatt hour

- W/m2

Watt per square meter

1. Introduction

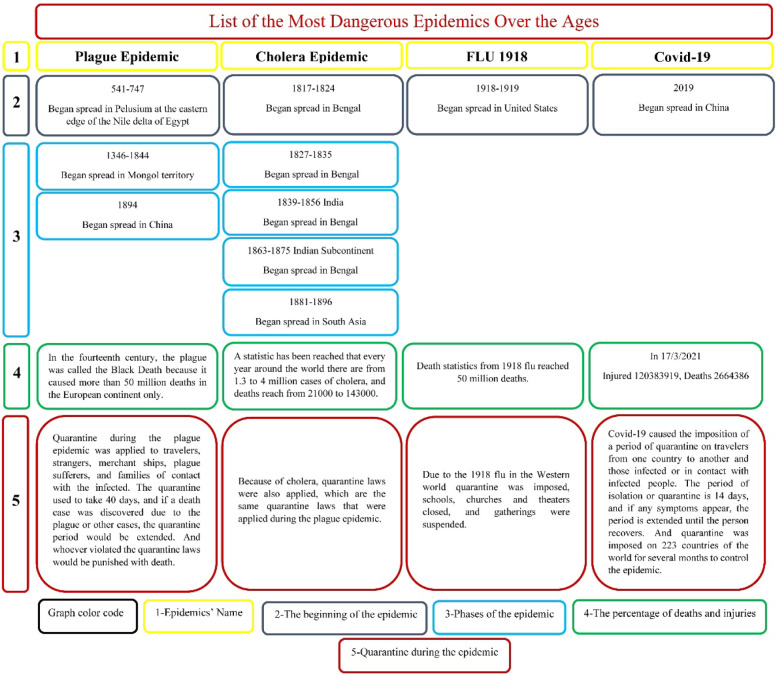

Throughout the ages, many epidemics have passed on humanity. Their number reaches 50 epidemics, but there are still four viruses that are the most famous and deadly of all (Fig. 1). Among them is the 1918 flu, which infected a third of the world’s population and killed 50 million people. These statistics at that time made this virus the most dangerous epidemic [1], [2], [3].

Fig. 1.

List of the most dangerous epidemics over the ages and their descriptions [1], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9].

The spread of infectious diseases and epidemics throughout the ages encouraged architects to invent new construction methods and planning to achieve a healthy environment in living spaces [10]. During the plague epidemic, the architectural design of the quarantine places considers that these places are well ventilated and have natural light, and are surrounded by green open areas to allow isolated people to practice sports [11]. The architect Christopher Wren believed that the cause of the plague spread and the burning of 1666 in London was the crowded and narrow streets; therefore, Wren resorted to re-planning the city in a healthy manner and with more wide streets. His trend has begun to design more healthy buildings with adequate ventilation and lighting [10], [11]. The architect Alvar Aalto was affected by the tuberculosis epidemic; for this reason, Aalto designed a tuberculosis sanatorium (Paimio Sanatorium) from 1928 to 1933 in Finland based on the entry of natural lightning and sufficient natural ventilation for all spaces [10], [12]. The epidemic also affected the thinking of the great Swiss-French architect Charles-Édouard Jeanneret (Le Corbusier) in terms of building design; consequently, Le Corbusier re-planned the center of Paris and called this futuristic city (La Ville Radieuse). One of the goals of La Ville Radieuse was to have better access to sunlight to all parts of the city and provide an immense amount of green spaces. The residential buildings in this city consist of duplex apartments, and each apartment contains its garden [10], [13]. Also, with the same concept, the design of the Pearl River tower came with four holes containing wind turbines to generate clean energy, which led to reduced the building energy consumption to 58%–60% [14], [15].

In this research, we tried to apply Le Corbusier’s concepts in designing the case study. So, our work began to search how to solve the problems that appeared due to Covid-19 by increasing natural ventilation, daylight inside buildings and integrating the house with nature.

Most of the quarantine and lockdown mentioned in Fig. 1 did not occur in the whole world, but it happened in certain cities, specific countries, or certain people. Across the ages, people subjected to quarantine described it as isolation and boredom, and suicides were reported [9]. In 2020, the Covid-19 epidemic caused the whole world to commit to quarantine simultaneously [16].

There are studies conducted in different countries to determine the effect of quarantine and lockdown on people’s mental and physical state. Through the spread of the global epidemic Covid-19 and resorting to quarantine, a questionnaire was conducted in Tehran to assess some mental and physical health indicators affected by quarantine. The quarantine also led to violence, abuse, and suicide inside the home. Homes that are small in area and do not have open spaces cause additional stress on people. The result is that open or semi-open space, natural ventilation, and lighting are essential for a person’s mental health [17], [18], [19], [20]. The quarantine and closure caused the World Health Organization, other entities, and studies to worry about people’s mental and psychological health and how to treat and take care of it. Also, quarantine caused people to stop exercising in clubs, which is one of the causes of depression [21], [22]. There are cases of depression that have led to suicide during quarantine and lockdown due to restriction of movement in limited areas inside homes that do not help carry out activities, playing, or freedom of movement [23]. Also, lockdown discerned the extent importance of the spaces inside apartments in meeting the population’s needs. The home has become the only place where a person practices all his social activities, even work. Another survey conducted on students at a university institute in Milan showed that poor housing was associated with an increased risk of developing depression during quarantine and closure. Cases of depression during quarantine led to suicide attempts. Poor housing is housing whose area is less than 60 m2, with no landscapes inside it. The housing design should be larger areas with green areas inside them [24], [25]. The Covid-19 pandemic and quarantine have caused architects to reconsider the planning and constructing of residential buildings in terms of area and design of spaces inside the future home. Also, to become sustainable residential buildings that depend on natural ventilation, good natural lighting, and open green spaces [17], [26]. some studies have shown how mental and physical health is related to green open spaces and how important they are. A survey in Mexico proved that during the Covid-19 pandemic, when people stopped going to urban green spaces (UGS) due to the closure, this negatively affected people’s well-being and mental and physical health [27], [28]. The importance of green spaces and gardens and the significance of integrating biophilia into daily life at home and work also emerged. Biophilia prevents life of isolation from nature that causes mental and physical illnesses. After Covid-19, architects are interested in achieving the biophilic concept in residential buildings [29]. Biophilic principles attempts to connect humans with nature, and implementing that concept helps alleviate physical and mental ailments. There are many features and elements of biophilic design; each element contains contents and other aspects [30]. A maximum of 50 m2 of space should be allocated to one person inside the house; For each extra person inside the house, the area should be 10 m2 larger [31]. For this reason, most of the inhabitants of Poland have migrated from one town to another to obtain housing that meets their needs as it accommodates the whole family with a small garden. This case shows how uncomfortable people are in the traditional multi-storey buildings with small areas and have no connection with nature [32]. Also, in Egypt, a study was conducted regarding the planning of paths and corridors between residential buildings is integrated with the natural green elements [33].

Covid-19 remains in the form of droplets on surfaces for hours, causing the spread of the infection to people. Also, there are some possibilities that humans inhaling airborne droplets of the virus is another route of infection with Covid-19 [34]. Therefore, all kinds of buildings, especially hospitals, work to renew the indoor air and constantly replace it with fresh air to eliminate pollutants and unwanted harmful things such as infection. Natural ventilation is important inside public buildings and hospitals to avoid the spread of infection; it is also essential for the health of the injured inside isolation [35], [36]. Some studies say that several people may become infected with the virus while sitting in their homes due to insufficient ventilation systems by inhaling the air laden with droplets of infection [37]. So, the virus transmission became more in winter due to the closure of all-natural ventilation sources inside the places. Therefore, it is recommended to open all ventilation sources such as louvers, doors, and windows to reduce the virus spread or any infectious disease inside the buildings. It has also been proven that sunlight disrupts other strains of Covid-19 [38]. That is why the places of isolation and quarantine should have excellent natural ventilation and lighting and are surrounded by the landscape.

A strategy must be developed to reduce the risk of infection inside the building. This strategy is for the building to have practical, natural, and adequate ventilation, to constantly purify and renew the air inside the building. Also, avoid recirculating the air inside the closed spaces [34]. The world has turned towards improving the building’s natural ventilation to prevent the transmission and spread of COVID-19 inside the building. However, in the Middle East countries, excessive air conditioners are carried out due to the harsh weather conditions. This mechanical ventilation is a potential factor for the spread and transmission of Covid-19 inside the building [34], [39], [40]. On the other hand, recent studies have emerged pointing to a dilution ventilation (DV) system and the ultraviolet germicidal irradiation (UVGI) designed to dilute pollutants and mitigate the risks of airborne transmission of COVID-19 [41], [42]. However, these technologies still are not used on a large scale. People spend 90% of their lives inside the traditional closed buildings, whether they are homes, workplaces, or schools. The traditional multi-storey buildings (sick building syndrome) cause many diseases to their users, such as asthma, heart diseases, and other diseases; this is due to insufficient natural ventilation inside the building [43], [44], [45], [46], [47], [48], [49]. Many environmental pollutants are generated inside homes, which cause many diseases, including asthma, lung cancer, and other diseases. Therefore, indoor air quality (IAQ) is essential for maintaining the health of the population [50]. It has been shown that the Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) directly affects the well-being and comfort of the building users. The IEQ should ideally be provided inside buildings to protect the general health of building users [51].

Some studies talked about infectious diseases and epidemics that spread in slums for many reasons, including the lack of planning, the absence of green open spaces, which caused the insufficient natural ventilation and natural lighting due to the proximity of the houses to each other [52], [53], [54]. Slums are not only buildings in poor condition, but on the contrary, are good buildings from the structural point of view. However, due to the network of narrow streets in random planning, the building becomes unsatisfactory from the design perspective with only one façade. Therefore, it does not contain adequate natural ventilation and natural lighting [55]. In Egypt, a large percentage of the rural population migrates to the cities, especially the capital. Due to their poverty, they cannot afford to buy good homes in good places; therefore, they buy houses in slums. The percentage of slum dwellers in Cairo began to increase after the 2011 revolution. Many studies show the danger of slum areas to the health of their residents and how to develop them [56], [57]. However, in 2020, the Egyptian government began to replace slums with new planned and sustainable cities that meet healthy and correct design standards. For all these reasons, our study focused on designing a residential building that may address these problems.

2. Methodology

In this paper, we improved the shape and composition of a traditional multi-storey residential building (sick building syndrome) to become a safe and healthy place. After modification, we compare it with a traditional one to study the natural ventilation (wind movement), the amount of energy required for cooling, and the intensity of natural lighting on both buildings using Design-Builder (licenced version) and Autodesk CFD (student version) programs. Using Autodesk CFD for wind movement study instead of the CFD module of Design-builder software returns to its accuracy and ease of use. Also, Autodesk CFD can precisely access the required level of detail in simulating wind movement [58]. We also studied the building entrance and redesigned it to make the building safer against the virus. Fig. 2 shows the methodology that we followed in the research.

Fig. 2.

Explanation of the research methodology.

2.1. Study area

We chose the study area in Egypt, precisely in Aswan Governorate (Fig. 3). The location is vacant land with no buildings located in the coordinates (23°5812.0N 32°4648.0E). This site is bordered by the Sahari region and the High Dam in the east, Krkr valley in the west, and Aswan-Abu Simbel Road in the north. The location is 6.41 km from the Sahari region, 9.22 km from the High Dam, 2.56 km from Krkr valley, and 0.49 km from Aswan-Abu Simbel Road, as shown in Fig. 4. The wind speed of Aswan is shown in Figs. 5, and 6 is the latest temperatures data of the months in Aswan from the NASA platform. Fig. 6 shows that the climate in Aswan city is harsh and hot, especially in the summer season, so it is not comfortable to rely only on natural ventilation inside the buildings without the use of mechanical ventilation.

Fig. 3.

The case study location [59].

Fig. 4.

Focus frame on the case study location in detail within the Aswan Governorate [59].

Fig. 5.

Wind speed in Aswan, (a) wind frequency rose; (b) wind speed rose; (c) wind speed [60].

Fig. 6.

Monitoring temperatures in Aswan Governorate during the months of 2019 [61].

2.2. Buildings description (case study)

We designed two buildings in the chosen location to study and compare them. Building (A) in Fig. 7 is a traditional multi-storey residential building, consists of six floors, the height of each floor is 4 m, with a total height of 24 m. The total built-up area is 6816 m2 with a footprint of 1136 m2, without any landscape area inside that building, as shown in Table 1. Building (B) in Fig. 8 is a multi-storey residential building, but we modified it. Building (B) has hollow parts, and it has become like blocks installed on top of each other, and there are spaces between them that are used as green areas. We also made green-faced and green roofs, as shown in Fig. 8. Each apartment in building (B) has become a duplex with an area of 364 m2, and each duplex apartment has its small garden of different sizes between 64 m2 and 110 m2, as shown in Fig. 9. In building (B), the number of floors, floor height, and the total height of the building is the same as the first model (building (A)) with a total built-up area is 6256 m2, footprint of 880 m2, with 3120 m2 landscape areas, as shown in Table 1. Building (B) breaks the rule of the traditional residential building by having a different design. Each apartment in this building is a duplex with large areas and has a small garden and green-faced and roofs. As mentioned in the literature part, we tried to apply Le Corbusier’s rules in designing the case study.

Fig. 7.

Building (A) shape in perspective view.

Table 1.

Height and area details of buildings (A) & (B).

| Data | Buildings (A) | Buildings (B) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Floors | 6 floors | 6 floors |

| Floor Height | 4 m | 4 m |

| Building Height | 24 m | 24 m |

| Total Built-up Area | 6816 m2 | 6256 m2 |

| Footprint | 1136 m2 | 880 m2 |

| Landscape | 0 m2 | 3120 m2 |

Fig. 8.

Building (B) shape in perspective view.

Fig. 9.

Focus frame on the apartment’s garden of the building (B).

2.3. Simulation software in this study

In this article, we chose Autodesk CFD and Design-Builder to simulate the case study. Autodesk CFD program can illustrate the movement of wind around the building with graphics and arrows. The Design-Builder program is one of the distinguished simulation programs that produce results that show the amount of energy consumed by the building and the intensity of natural lighting inside the building. The input parameters in Design-Builder for the selected location from energy plus to determine the weather, Materials used in buildings are (plaster (0.05 m) - brick _ burned (0.25 m) – plaster (0.05 m), green roof in building (B) only). Glazing types of windows are (external glazing 3 mm – internal glazing 3 mm – wooden frame). Lighting Power Densities is 5 W/m2. We used a cooling system (Fan coil unit (4 pipes) - air cooled chiller) and natural ventilation by scheduling each zone at a rate of 3 ACPH.

3. Results and discussion

The first stage is to simulate both buildings (A) and (B) in the Autodesk CFD program to show the movement of winds around each of them. This simulation ran in a normal situation without considering the sandstorm. In the next stage, we simulate the case study buildings on the Design-Builder program to know the amount of energy used for cooling in the hot months and the intensity of natural lighting inside each of them. We also proposed a design for the entrance to ensure the pass ban of any infected person to the building. Fig. 10, Fig. 11 show the diagrams of the two buildings to illustrate the sections that we used in the simulation.

Fig. 10.

A diagram for the location of the sections in building (A) that will be used to illustrate the simulation.

Fig. 11.

A diagram for the location of the sections in building (B) that will be used to illustrate the simulation.

3.1. Natural ventilation (wind movement)

From the simulation in Autodesk CFD, we found that building (A) works as a barrier in front of wind flow, as the building prevents the free movement of wind around it and prevents the wind from regularly entering inside the building shown in Fig. 12. Also, when the wind is converted into arrows, we saw clearly that the arrows are heading towards the building (Fig. 13). When it finds an obstacle (building (A)), it begins to rotate behind the building and head next to the building without entering it.

Fig. 12.

Illustration of wind movement in building (A), (A-1) plan, (A-2) east section, (A-3) north section.

Fig. 13.

Illustration of wind movement in building (A), (A-4) east elevation.

On the other hand, the wind movement in building (B) is smooth and dynamic, as the openings between the building parts allow the wind to penetrate and pass between them, as shown in Figs. 14, and 15. Also, when the wind is converted into arrows, we observe that the arrows are heading towards the building (Fig. 16); when they find spaces between the building parts, they begin to penetrate the voids comfortably, enter between them without obstacles, thus enter the whole building. From this simulation, it is essential to note that spaces between building (B) parts are vital and effective to allow wind to penetrate and enter all building parts. Spaces between the mass of building (B) achieved sufficient distribution for natural ventilation inside it. Adequate natural ventilation leads to constantly renewing the air inside the building, which prevents the spread of diseases inside it. In this comparison, it is better to generalize building (B) design in residential communities because it achieved sufficient natural ventilation in the different spaces of the building, which helps improve the residents’ mental and physical health.

Fig. 14.

Illustration of wind movement in building (B), (B-1) Plan of first, third and fifth typical floor, (B-2) plan of second, fourth and sixth typical floor.

Fig. 15.

Illustration of wind movement in building (B), (B-3) east section, (B-4) east section, (B-5) north section.

Fig. 16.

Illustration of wind movement in building (B), (B-6) east elevation.

3.2. Cooling system

We simulated the buildings in the Design-Builder program to determine the amount of energy used in cooling and compare the data of the hottest months in Aswan according to Fig. 6, which are from April to September. From the simulation, we found that the cooling system used in building (A) in April, May, June, July, August, and September: 62527.30, 79674.20, 76367.63, 96581.30, 87361.63, 78926.06 kWh, respectively. On the other hand, the cooling system used in building (B) in the same months: 43878.67, 57750.69, 56026.18, 71434.17, 63929.54, 56401.81 kWh, respectively. The comparison between simulation results in Fig. 17 clearly shows that the energy use rate in the cooling of building (B) is lower than in building (A). In this comparison, it turned out that building (B) achieved saving energy consumption, which reduces the pollution that may be one of the diseases spreading causes.

Fig. 17.

A comparison of energy consumption for the cooling system between buildings (A)&(B).

3.3. Natural lighting

To visualize daylight access to the different spaces in the case study, we collected the results data from Design-Builder software to determine the intensity and adequacy of natural lighting inside them (Figs. 18, 19). From this simulation, we found that the intensity of natural lighting in building (B) is more significant than building (A). Spaces between the building (B) parts are essential and effective to allow sunlight to penetrate the entire building. As per the studies, Adequate sunlight eliminates viruses and microbes and prevents the spread of diseases. In this comparison, building (B) achieved better efficiency in receiving a higher percentage of sunlight.

Fig. 18.

Illustration of natural lighting in building (A), (A-1) plan.

Fig. 19.

Illustration of natural lighting in building (B), (B-1) plan of first, third and fifth typical floor.

3.4. Main entrance

After the Covid-19 epidemic, the redesign of building entrances must be considered again to add a layer of protection for the building residents. So, we divided the entrance of building (B) into three zones, as shown in Fig. 20. The first one is sterilization, and the second zone contains sensors, warning technologies, and self-cleaning materials [62]. These materials find out the injured person. Once this person enters this zone, the system begins to warn and not allow the infected person to enter the building. The third zone is a safe entry place for the building without any infected person. At the entrance, a robot can be used that measures the temperature of people before entering the building and knows if they are injured or not. The robot will also disinfect and sterilize the entrance surfaces and people before entering the building [63], [64].

Fig. 20.

Redesign the Plan of entrance inside the building (B).

4. Conclusion

Getting the best design for the multi-storey residential building is our goal in this study to become a healthy, sustainable, and suitable place to live. The criterion of healthy housing is to achieve adequate natural ventilation and lighting for all parts of the housing, which prevents diseases and viruses, achieves thermal comfort, and the presence of green parts to improve the psychological state of the population.

As the results showed, the traditional multi-storey residential building (A) prevents wind movement inside it, which reduces the rate of renewal and change of air inside it. Also, it prevents sunlight from entering all its parts, does not enjoy thermal comfort, consumes much energy, and does not have any green elements. All these issues in building (A) lead to the spread of diseases, infections, and deterioration of humans’ psychological state. On the other hand, building (B), which we modified its design, has become a building that is close to ideal. The openings between its parts allow the passage of wind and the renewal of air. Building (B) turns into a healthy place in which adequate natural ventilation and lighting, the air rate constantly changed and renewed, and the green elements have been achieved. All these advantages in building (B) prevent the spread of diseases and improve the psychological and mental state of the population. Moreover, from the perspective of energy consumption, there is a 38% decrease compared to building (A). Also, when the entrance contains sterilization zones, self-cleaning materials, and sensors, which warn against any virus, the building users in a large percentage are safe from epidemics. Adequate natural ventilation and lighting and achieving a biophilic concept are essential principles that must be in the design of residential buildings to avoid the suicides and the spread of COVID-19 that happened recently.

The whole world is trying to find solutions for traditional multi-storey residential buildings to become healthy, sustainable, suitable for living, and linked to the green elements. If the principles of a healthy multi-storey residential building are achieved, it will prevent the spread of infectious diseases inside it and achieve psychological comfort for the residents. We tried to achieve all of this in building (B) to become closer to the ideal multi-storey residential building image. Through this research, it is necessary to note that if there is an area all multi-storey residential buildings designed with the same concept as building (B), the passage of air and wind will become very dynamic between all the buildings in that urban context. Therefore, this area will become environmentally sustainable because it does not need to consume much energy and the existence of adequate natural ventilation and lighting in it.

5. Future work

In future articles, different ideas should be devised for the isolation area inside the home to protect family members from transmitting the infection between them. It is also necessary to study design solutions for planning the urban fabric to prevent the spread of diseases through buildings similar to building (B) that allow the continuity of renewed natural ventilation and lighting within the region or the city. It is also recommended to study building (B) design in other countries to show the extent of adaptation of this building to other regions around the world.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Hays JN. 2005. Epidemics and pandemics: their impacts on human history: ABC-CLIO. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taubenberger JK., Morens DM. 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Rev Biomed. 2006;17(1):69–79. doi: 10.3201/eid1201.050979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleczkowski A., Hoyle A., McMenemy P. One model to rule them all? Modelling approaches across OneHealth for human, animal and plant epidemics. Phil Trans R Soc B. 2019;374(1775) doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Plague 2017 [Available from]: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/plague.

- 5.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) 2020 [Available from]: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/question-and-answers-hub/q-a-detail/coronavirus-disease-covid-19.

- 6.World Health Organization. Cholera 2021 [Available from]: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cholera.

- 7.Tognotti E. Lessons from the history of quarantine, from plague to influenza A. Emerg Infect Diseases. 2013;19(2):254. doi: 10.3201/eid1902.120312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conti AA. Quarantine through history. Int Encyclopedia Public Health. 2008:454. doi: 10.1016/B978-012373960-5.00380-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Newman KL. Shutt up: bubonic plague and quarantine in early modern England. J Soc Hist. 2012;45(3):809–834. doi: 10.1093/jsh/shr114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.J. Xu, The impact of epidemics on future residential buildings in china, Rochester Institute of Technology, 2020.

- 11.Hebbert M. The long after-life of Christopher Wren’s short-lived London plan of 1666. Plann. Perspect. 2018 doi: 10.1080/02665433.2018.1552837. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heikinheimo M., editor. Arts. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute; 2018. Paimio sanatorium under construction. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. Montavon, K. Steemers, V. Cheng, R. Compagnon, La Ville Radieuse by Le Corbusier, once again a case study, in: The 23rd conference on passive and low energy architecture, Geneva, Swizerland, 2006.

- 14.Frechette III R.E., Gilchrist R. Seeking zero energy. Civ Eng Mag Archive. 2009;79(1):38–47. doi: 10.1061/ciegag.0000208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mirniazmandan S., Rahimianzarif E. Biomimicry, an approach toward sustainability of high-rise buildings. Iran J Sci Technol Trans A Sci. 2018;42(4):1837–1846. doi: 10.1007/s40995-017-0397-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee K., Chauhan V. Epidemics, quarantine and mental health. Med J Armed Forces India. 2020;76(2):125. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2020.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tokazhanov G., Tleuken A., Guney M., Turkyilmaz A., Karaca F. How is COVID-19 experience transforming sustainability requirements of residential buildings? A review. Sustainability. 2020;12(20):8732. doi: 10.3390/su12208732. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazza M., Marano G., Lai C., Janiri L., Sani G. Danger in danger: Interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res. 2020;289 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsamakis K., Tsiptsios D., Ouranidis A., Mueller C., Schizas D., Terniotis C., et al. COVID-19 and its consequences on mental health. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(3):1. doi: 10.3892/etm.2021.9675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarrabi M., Yazdanfar S-A., Hosseini S-B. COVID-19 and healthy home preferences: The case of apartment residents in Tehran. J Build Eng. 2021;35 doi: 10.1016/j.jobe.2020.102021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavin B., Lyne J., McNicholas F. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Psychol Med. 2020;37(3):156–158. doi: 10.1017/ipm.2020.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antunes R., Frontini R. Physical activity and mental health in Covid-19 times: an editorial. Sleep Med. 2021;77:295. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2020.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Soetikno N., editor. The 2nd tarumanagara international conference on the applications of social sciences and humanities. Atlantis Press; 2020. Descriptive study of adolescent depression in covid-19 pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corpuz J.C.G. COVID-19 and mental health. J Psychosoc Nurs Mental Health Serv. 2020;58(10):4. doi: 10.3928/02793695-20200916-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amerio A., Brambilla A., Morganti A., Aguglia A., Bianchi D., Santi F., et al. COVID-19 lockdown: housing built environment’s effects on mental health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5973. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzalez J., Krarti M. Reflecting on impacts of COVID19 on sustainable buildings and cities. ASME J Eng Sustain Build Cities. 2021:1–8. doi: 10.1115/1.4050374. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bereitschaft B., Scheller D. How might the COVID-19 pandemic affect 21st century urban design, planning, and development? Urban Sci. 2020;4(4):56. doi: 10.3390/urbansci4040056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mayen Huerta C., Cafagna G. Snapshot of the use of urban green spaces in mexico city during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4304. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18084304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Willoughby M. Shared trauma, shared resilience during a pandemic. Springer; 2021. The natural world: the role of ecosocial work during the COVID-19 pandemic; pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kellert SR., Heerwagen J., Mador M. Biophilic design: the theory, science and practice of bringing buildings to life. John Wiley & Sons; New Jersey, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neufert E., Neufert P. 4th ed. Wiley-Blackwell; London, UK: 2012. Architects’ data. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gyurkovich J, editor. IOP conference series: materials science and engineering. IOP Publishing; 2019. Living space in a city-selected problems of shaping modern housing complexes in cracow-a multiple case studies: part 2–the case study of high density forms of multi-family residential buildings. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Imam KZEA. Role of urban greenway systems in planning residential communities: a case study from Egypt. Landsc Urban Plan. 2006;76(1–4):192–209. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2004.09.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morawska L., Tang JW., Bahnfleth W., Bluyssen PM., Boerstra A., Buonanno G., et al. How can airborne transmission of COVID-19 indoors be minimised? Environ Int. 2020;142 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhagat RK., Linden P. Displacement ventilation: a viable ventilation strategy for makeshift hospitals and public buildings to contain COVID-19 and other airborne diseases. R Soc Open Sci. 2020;7(9) doi: 10.1098/rsos.200680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen C., Zhao B. Makeshift hospitals for COVID-19 patients: where health-care workers and patients need sufficient ventilation for more protection. J Hosp Infect. 2020;105(1):98. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hwang SE., Chang JH., Oh B., Heo J. Possible aerosol transmission of COVID-19 associated with an outbreak in an apartment in Seoul, South Korea, 2020. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;104:73–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Burridge HC., Bhagat RK., Stettler ME., Kumar P., De Mel I, Demis P., et al. The ventilation of buildings and other mitigating measures for COVID-19: a focus on wintertime. Proc R Soc Lond Ser A Math Phys Eng Sci. 2021;477(2247) doi: 10.1098/rspa.2020.0855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amoatey P., Omidvarborna H., Baawain MS., Al-Mamun A. Impact of building ventilation systems and habitual indoor incense burning on SARS-CoV-2 virus transmissions in Middle Eastern countries. Sci Total Environ. 2020;733 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bhagat RK., Wykes MD., Dalziel SB., Linden P. Effects of ventilation on the indoor spread of COVID-19. J Fluid Mech. 2020:903. doi: 10.1017/jfm.2020.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sha H., Zhang X., Qi D. Optimal control of high-rise building mechanical ventilation system for achieving low risk of COVID-19 transmission and ventilative cooling. Sustainable Cities Soc. 2021;74 doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2021.103256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo M., Xu P., Xiao T., He R., Dai M., Miller SL. Review and comparison of HVAC operation guidelines in different countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Build Environ. 2021;187 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wargocki P., Sundell J., Bischof W., Brundrett G., Fanger PO., Gyntelberg F., et al. Ventilation and health in non-industrial indoor environments: report from a European multidisciplinary scientific consensus meeting (EUROVEN) Indoor Air. 2002;12(2):113–128. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0668.2002.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Srinivasan S., O’fallon LR., Dearry A. Creating healthy communities, healthy homes, healthy people: initiating a research agenda on the built environment and public health. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1446–1450. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sundell J., Levin H., Novosel D. National Center for Energy Management and Building Technologies; Alexandria, USA: 2006. Ventilation rates and health: report of an interdisciplinary review of the scientific literature. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krieger J., Jacobs DE. Making healthy places. Springer; 2011. Healthy homes; pp. 170–187. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flexible housing, a healthy housing: a brief discussion about the merits of flexibility in designing healthy accommodation, IM. Rian, M. Sassone (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on’inhabiting the future’, Napoli, Italy, 2012, 10.13140/2.1.3045.4722. [DOI]

- 48.Wargocki P. The effects of ventilation in homes on health. Int J Vent. 2013;12(2):101–118. doi: 10.1080/14733315.2013.11684005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ventilation and health-a review, S. Urlaub, G. Grün, P. Foldbjerg, K. Sedlbauer (Eds.), Proc AVIC conf, Madrid, Spain, 2015.

- 50.Cincinelli A., Martellini T. Indoor air quality and health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017 doi: 10.3390/ijerph14111286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Awada M., Becerik-Gerber B., Hoque S., O’Neill Z., Pedrielli G., Wen J., et al. Ten questions concerning occupant health in buildings during normal operations and extreme events including the COVID-19 pandemic. Build Environ. 2021;188 doi: 10.1016/j.buildenv.2020.107480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.El Menshawy A., Aly SS., Salman AM. Sustainable upgrading of informal settlements in the developing world, case study: Ezzbet Abd El Meniem Riyadh, Alexandria, Egypt. Procedia Eng. 2011;21:168–177. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2011.11.2001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oppong JR., Mayer J., Oren E. The global health threat of African urban slums: the example of urban tuberculosis. Afr Geograph Rev. 2015;34(2):182–195. doi: 10.1080/19376812.2014.910815. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.ElFouly HA., El Aziz NA. Physical quality of life benchmark for unsafe slums in egypt. Sustain Environ. 2017;2(2):258. doi: 10.22158/se.v2n2p258. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Elewa AKA., El-Garhy WAT. Urban environment. Springer; 2013. The roles of the urban spatial structure of the main cities slums in Egypt and the environmental pollution; pp. 179–191. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ayyad KM., Gabr M. The role of environmentally conscious architecture and planning as components of future national development plans in Egypt. Buildings. 2013;3(4):713–727. doi: 10.3390/buildings3040713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ragheb G., El-Shimy H., Ragheb A. Land for poor: towards sustainable master plan for sensitive redevelopment of slums. Procedia-Soc Behav Sci. 2016;216:417–427. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.12.056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Broekhuizen I. 2016. Integrating outdoor wind simulation in urban design: a comparative study of simulation tools and their benefits for the design of the LTU campus in luleå. [Google Scholar]

- 59.. Google Earth, Aswan location 2021 [Available from]: https://earth.google.com/web/search/egypt/Aswan/.

- 60.The global wind atlas. Wind speed in aswan 2021 [Available from]: https://globalwindatlas.info/.

- 61.The prediction of worldwide energy resources (POWER) project. Temperature in Aswan 2019 [Available from]: https://power.larc.nasa.gov/data-access-viewer/.

- 62.Meguid S., Elzaabalawy A. Potential of combating transmission of COVID-19 using novel self-cleaning superhydrophobic surfaces: part I—protection strategies against fomites. Int J Mech Mater Des. 2020;16(3):423–431. doi: 10.1007/s10999-020-09513-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang G-Z., Nelson BJ., Murphy RR., Choset H., Christensen H., Collins SH., et al. Combating COVID-19—The role of robotics in managing public health and infectious diseases. Science Robotics. 2020 doi: 10.1126/scirobotics.abb5589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Javaid M., Haleem A., Vaishya R., Bahl S., Suman R., Vaish A. Industry 4.0 technologies and their applications in fighting COVID-19 pandemic. Diabetes Metab Syndr: Clin Res Rev. 2020;14(4):419–422. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.