Abstract

Symbiobacterium thermophilum is a tryptophanase-positive thermophile which shows normal growth only in coculture with its supporting bacteria. Analysis of the 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) indicated that the bacterium belongs to a novel phylogenetic branch at the outermost position of the gram-positive bacterial group without clustering to any other known genus. Here we describe the distribution and diversity of S. thermophilum and related bacteria in the environment. Thermostable tryptophanase activity and amplification of the specific 16S rDNA fragment were effectively employed to detect the presence of Symbiobacterium. Enrichment with kanamycin raised detection sensitivity. Mixed cultures of thermophiles containing Symbiobacterium species were frequently obtained from compost, soil, animal feces, and contents in the intestinal tracts, as well as feeds. Phylogenetic analysis and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of the specific 16S rDNA amplicons revealed a diversity of this group of bacteria in the environment.

Symbiobacterium thermophilum is a symbiotic bacterium isolated from compost collected at Hiroshima, Japan. This organism formed no visible colonies and was first recognized by its thermostable tryptophanase activity in a liquid culture with thermophilic Bacillus sp. strain S (16). Although S. thermophilum grows up to 8 × 108 cells per ml in the mixed culture with Bacillus strain S (8, 16), any medium supplied with various additives failed to establish a pure culture. While the precise molecular characterization of two tryptophanases and one tyrosine-phenol lyase (β-tyrosinase) of this organism was successful (2, 3, 5, 14, 15), the physiological bases underlying its symbiotic characteristics have remained unclear, since the inability to form colonies made it difficult to trace the growth of this bacterium with reliable specificity. Recent development of PCR-based procedures, however, enabled sensitive and specific detection and quantification of growth for establishing an axenic culture of S. thermophilum in a dialyzing cultivation system under a continuous supply of a dialyzable substance(s) produced by Bacillus strain S (8). The growth-supporting activity was also identified in culture filtrates of various bacteria.

Along with the unique physiological properties, the 16S RNA gene (rDNA) sequence of S. thermophilum indicated that it belongs to the gram-positive bacterial group, although it is negative by traditional Gram stain, and creates a novel phylogenetic branch at an outermost position in the group without clustering with any other bacterial genus (9). The presence of other strains belonging to the genus Symbiobacterium has been implicated not only by our preliminary screening by PCR which resulted in the isolation of a homologous 16S rDNA sequence, YK67 (9), but also by the study of Lee et al. who reported isolation of a similar organism, Symbiobacterium sp. strain SC-1 (6). This work deals with extensive screening to explore distribution and diversity of Symbiobacterium species according to the detection of tryptophanase activity in thermophilic cultures and PCR amplification of the specific 16S rDNA. All the results clearly demonstrate wide distribution and potential diversity of this phylogenetically isolated group of bacteria in natural environments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sources for screening, strains, and culture conditions.

Samples of compost and soil were collected at various regions in Japan (see Table 2). Animal feces were collected at two zoos (Ueno and Tama in Tokyo) and a cattle breeding farm (Hosono Holstein Farm, Tokyo). Most of the intestinal contents were sampled upon slaughter in the Chuou Meat Inspection Laboratory of the Gunma Prefecture, except for the direct sampling from five living goats at Nihon University (Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture) and four living cattle at the STAFF Institute (Tsukuba, Ibaragi Prefecture). Animal feeds examined were hays (prepared in an experimental farm of Nihon University), several kinds of grains, and commercial pellet-type complex nutritional feeds. Each sample (1 to 2 g) was added into 100 ml of Luria-Bertani (LB) liquid medium containing (in grams per liter) tryptone peptone (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), (1), yeast extract (DIFCO) (0.5), and NaCl (0.5), pH 7.2, in a 300-ml Erlenmeyer flask and incubated stationary at 60°C for 2 to 6 days. Tryptophanase activity in the liquid culture was checked by the colorimetric assay with Kovács reagent added to the culture broth (16). For the solid culture, a drop of Kovács reagent was directly spotted onto colonies.

TABLE 2.

Numbers of Trp+ and PCR+ cultures obtained from compost and soil

| Prefecture | No. of cultures from:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compost

|

Soil

|

|||||

| Total | Trp+ | PCR+ | Total | Trp+ | PCR+ | |

| Kanagawa | 50 | 30 | 26 | 38 | 11 | 5 |

| Fukushima | 18 | 18 | 17 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Chiba | 12 | 8 | 6 | 13 | 2 | 2 |

| Toyama | 10 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Okinawa | 8 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hokkaido | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Tokyo | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 11 | 6 |

| Ibaragi | 5 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 1 | 1 |

| Total | 107 | 72 | 56 | 93 | 25 | 14 |

Kanamycin was used for the enrichment culture based on the intrinsic resistance of S. thermophilum. LB liquid medium (100 ml) added with kanamycin (20 μg/ml; Wako Pure Chemical Industries, Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was prepared similarly as above and inoculated with 1 ml of each kanamycin-free broth cultures. Simultaneously, 1 ml of the overnight culture of Bacillus subtilis 1012 (11) harboring pTB53 (carrying the thermostable kanamycin resistance gene [4]) in LB liquid medium with kanamycin (20 μg/ml) was inoculated to support the growth of Symbiobacterium. The cultivation was conducted without shaking at 51°C to allow the growth of B. subtilis, and each culture broth was processed similarly to the kanamycin-free culture described above. A mixed culture of S. thermophilum strain T IAM14863 and Bacillus sp. strain S in LB liquid medium (8) was used for control experiments. Escherichia coli JM109 [Δ(lac-pro) thi-1 endA1 gyrA96 hsdR17 relA1 recA1/F′ traD36 proAB laclq lacZΔM15] was used as a host for the cloning of 16S rDNA.

DNA extraction.

Total chromosomal DNA of microbial cells in the culture was prepared as follows (8). Each 0.1 ml of culture broth was mixed with 1 μl of DNase I solution (10 U/ml; Boehringer Manheim, Manheim, Germany) and 9 μl of morpholine propanesulfonic acid (MOPS) buffer (20 mM MOPS and 125 mM MgSO4; pH 6.8) and subjected to successive incubation at 37°C (30 min). This procedure was done to eliminate chromosomal DNA derived from nonviable cells. Samples were successively incubated at 100°C (5 min), −20°C (60 min), and 100°C (10 min) to raise the efficiency in the following lysis procedure. Samples were then added to the lysis solution containing 2 μl of proteinase K (0.3 U/μl; Promega Co., Madison, Wis.) and 28 μl of lysis buffer (containing 0.5% Tween 20, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 0.3 mM EDTA, and 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) and incubated at 60°C for 1h. The lysates were then boiled for 10 min and centrifuged at 17,000 × g for 5 min, and each 10 μl of the resultant supernatant was used as a template for the following PCR.

PCR.

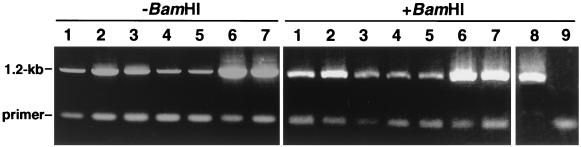

The PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. Sequences of the specific primers (Sym4 and Sym5) for amplification of S. thermophilum 16S rDNA were determined according to the multiple alignment of the prokaryotic 16S rDNA and designed to hybridize at the V2 and V8 regions to amplify approximately 1.2-kb fragments. A database search revealed no microbial nucleotide sequence with high similarity to the specific primers, except for the two sequences from unidentified rumen bacteria (accession no. AB009222 and AB009179) that contain regions 90% identical to the sequence of Sym5. Preliminary checks confirmed that the reaction with specific primers efficiently amplified the 1.2-kb fragment from total DNA of the mixed culture of S. thermophilum strain T and Bacillus strain S, whereas it generated no amplicon from the pure culture of the Bacillus (Fig. 1, lanes 8 and 9). Further, to raise the detection sensitivity, a two-step PCR procedure was employed; first, total DNA was subjected to the reaction with universal primers (B8F and B1500D) designed to amplify the 1.5-kb procaryotic 16S rRNA genes, and the resultant amplicon was purified from agarose gel by a Gene Clean Kit (Funakoshi, Tokyo, Japan) and then subjected to the second PCR with the Symbiobacterium-specific primers (Sym4 and Sym5) which amplified the 1.2-kb fragments. The first step could enable enrichment of the 16S rDNA sequences in the crude DNA preparation and thus raise the sensitivity of the detection in the second step. Culture broth that generated the Symbiobacterium-specific 1.2-kb amplicon was judged as Symbiobacterium positive. All PCR was done with Ex Taq polymerase (TaKaRa Shuzo, Kyoto, Japan) under the conditions recommended by the manufacturer and processed in a GeneAmp PCR System 9600 thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.) in the following program: denaturation at 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and a final extention at 72°C for 3 min.

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used to amplify the 16S rDNA

| Primer name | Sequence | Position (nt) |

|---|---|---|

| B8F | 5′-AGAGTTTGATC(A/C)TGGCTCAG | 8–27a |

| B1500D | 5′-TACCTTGTTACGACTTCACCCCAG | 1507–1484a |

| Sym4 | 5′-TCTGCTCTGGGATAACAGGC | 108–127b |

| Sym5 | 5′-GAACTGAGACCGCCTTTTGC | 1297–1278b |

| 341F-GC | 5′-CGCCCGCCGCGCGCGGCGGGCGG GGCGGGGGCACGGGGGGCCTACG GGAGGCAGCAG | 326–342b |

| 534R | 5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG | 519–503b |

E. coli numbering.

S. thermophilum numbering.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the Symbiobacterium-specific amplicons. Seven representative amplimers from commercial feeds (lanes 1 to 7) were electrophoresed before (−) and after (+) BamHI digestion. Lanes for the BamHI-digested PCR products from the mixed culture of S. thermophilum and Bacillus sp. strain S (lane 8, positive control) and the pure culture of Bacillus sp. strain S (lane 9, negative control) are also shown.

DGGE.

Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) was performed on a D-code apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). The Symbiobacterium-specific 1.2-kb DNA amplicons obtained as described above were extracted and purified from agarose gel by a Gene Clean Kit and used as templates for amplification with the universal DGGE primers (341F-GC and 534R [7]). The resultant 200-bp amplicon was applied onto the denaturing gel. The cloned 1.2-kb 16S rDNA fragments of S. thermophilum strain T IAM14863 and YK67 (9) were prepared by the standard technique and similarly processed to apply onto the gel as a control. Samples containing approximately equal amounts of PCR products were loaded onto 10% (wt/vol) polyacrylamide gels (37.5:1, acrylamide-bisacrylamide) in 1× Tris-acetate-EDTA (TAE), (containing 40 mM Tris, 20 mM acetic acid, and 1 mM EDTA) with a denaturing gradient ranging from 20 to 80% denaturant (100% denaturant contains 7 M urea and 40% [vol/vol] formamide in 1× TAE). Electrophoresis was performed at 60°C and 200 V for 180 min. The gel was stained with Vistra Green (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) and scanned and visualized by a Fluor Imager (Molecular Dynamics, Sunnyvale, Calif.).

DNA cloning, sequencing, and phylogenetic analysis of 16S rDNA.

The 1.2-kb 16S rDNA fragments amplified by the specific PCR using primers Sym4 and Sym5 were digested with BamHI and cloned at the BamHI site of M13 mp19. All the BamHI-digested amplicons produced a single band at the position of 1.2 kb in agarose gels, which indicated that the amplified fragments did not contain internal BamHI cleavage sites. A representative migration pattern of the amplicons before and after the digestion with BamHI is shown in Fig. 1. Restriction endonucleases and other modifying enzymes were purchased from TaKaRa Shuzo. The nucleotide sequence of each clone was determined following the standard cycle sequencing protocol by a Thermo Sequenase cycle sequencing kit (Amersham-Pharmacia) and analyzed by an automated DNA sequencer (model 4100; LiCor, Lincoln, Nebr.). Nucleotide sequences were aligned by Clustal W (17). Neighbor-joining phylogeny (12) was constructed by using the NJ plot program (10), and bootstrapping (1) was used to estimate the reliability of phylogenetic reconstructions (1,000 replicates).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

16S rDNA sequences were submitted to the DDBJ databank under accession numbers AB052368 to AB052397.

RESULTS

Detection of Symbiobacterium in mixed cultures of thermophiles.

Tryptophanase productivity was expected to be a characteristic specific to S. thermophilum among thermophilic bacteria, and thus the enzyme activity in cultures at elevated temperatures was used as an indicator for the presence of this bacterial species. We examined mixed cultures of thermophiles cultivated at 60°C which were obtained from various compost and soil samples and found that tryptophanase-positive (Trp+) cultures appeared frequently (Table 2). None of the colony-forming microbes derived from these positive cultures showed tryptophanase activities, which suggested that the enzyme activities in the mixed cultures were mostly due to the organisms which were unable to form colonies as S. thermophilum.

To further confirm the presence of Symbiobacterium, we carried out PCR to detect the specific 16S rDNA sequences. Application of the specific primers to the Trp+ cultures described above resulted in efficient amplification of the expected 1.2-kb 16S rDNA fragments (PCR+), some of which were preliminarily sequenced and confirmed to be identical or highly similar to that of S. thermophilum strain T. The ratio of the PCR+ to the Trp+ cultures was 78% in compost and 56% in soil (Table 2). Thus, we concluded that tryptophanase activity was a useful indicator for screening Symbiobacterium, and the PCR primers were specific for the detection of this organism. The preliminary experiment also suggested that more sensitive detection was achieved by introducing the two-step PCR procedure (see Materials and Methods), in which amplification of the universal 1.5-kb fragments was carried out prior to the specific reaction to Symbiobacterium. All the PCR-based detection shown below followed this protocol.

Enrichment with kanamycin.

In our study on its physiological properties, S. thermophilum strain T was found to be resistant to kanamycin concentrations up to 100 μg/ml and the possibility of using the antibiotic to enrich Symbiobacterium was examined. Several kanamycin-free cultures of thermophiles were examined as to the tryptophanase and 16S rDNA signals and then transferred into LB broth added with kanamycin together with kanamycin-resistant B. subtilis cells as a growth supporter. As shown in Table 3, Trp+ cultures were obtained from all the pig intestinal contents examined irrespective of the kanamycin selection, and the selection further enabled amplification of the specific fragments in several cultures that were PCR− without the selection. This result suggested that selection with kanamycin is useful to enrich Symbiobacterium in the mixed thermophilic cultures. This procedure was applied to the screening samples from animal intestinal contents and feces.

TABLE 3.

Effect of kanamycin selection for enrichment of Symbiobacterium in representative cultures derived from pig intestinal contents

| Sample no. | Without kanamycin

|

With kanamycin

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp | PCR | Trp | PCR | |

| 2 | + | − | + | − |

| 4a | + | − | + | + |

| 5a | + | − | + | + |

| 7a | + | − | + | + |

| 11 | + | − | + | − |

| 14 | + | + | + | + |

| 18 | + | + | + | + |

| 24 | + | − | + | − |

| 27 | + | + | + | + |

Culture became PCR+ after kanamycin selection.

Distribution of Symbiobacterium in the environment. (i) Compost and soil.

To investigate the distribution of S. thermophilum and its relatives in the environment, we first examined compost, the original source of S. thermophilum strain T. As summarized in Table 2, compost collected at different regions not only in the main island of Japan, Honsyu, but also in Hokkaido, Kyusyu, and Okinawa frequently produced Trp+ cultures of thermophiles at 60°C (72 of 107 samples), among which a large fraction (56 of 72 samples) was PCR+. At relatively lower but still high frequencies, Trp+ (25 of 93) and Trp+ PCR+ (14 of 25) cultures were obtained from soil samples. Successive plating of each Trp+ culture broth sample onto LB agar medium and cultivation at 60°C produced colonies of thermophilic bacteria, most of which were those of Bacillus spp. as judged from macroscopic and microscopic observations. No colonies showed a positive reaction to Kovács reagent, indicating that none of the colony-forming microbes produced tryptophanase.

(ii) Feces and intestinal contents of animals.

During the course of screening, we noticed that compost made from animal feces produced positive cultures at a relatively high ratio. This observation prompted us to examine whether Symbiobacterium is one of the commensal organisms in animal digestive organs. First we examined fresh feces of cows (Holstein) bred at a farm, and found that 7 out of 26 samples gave Trp+ PCR+ cultures (Table 4). We further examined feces of various animals reared in zoos. Among feces of 41 different animal species collected at two zoos, samples from 35 species of mammals (including 11 ruminants), four species of reptiles, and two species of birds produced Trp+ PCR+ cultures (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Numbers of Trp+ and PCR+ cultures obtained from animal feces

| Animal | Site of collectiona | No. tested | No. positive

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp | PCR | |||

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | H | 26 | 7 | 7 |

| Buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) | T | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Takin (Budorcas taxicolor) | T | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Tailed deer (Elaphurus davidianus) | T | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) | T | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis) | T | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| African elephant (Loxodonta africanus) | T | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Oryx (Oryx beisa) | T | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Yaku-shika deer (Cervus nippon) | T | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochoeris) | U | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 11 Animal speciesb | T | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 27 Animal speciesc | U | 1 | 1 | 1 |

Abbreviations: H, Hosono Holstein Farm; T, Tama zoo; U, Ueno zoo.

Species included were Asiatic elephant (Elephans maximus), Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus), Japanese boar (Sus leucomystax), cheetah (Acinonyx jubatus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), Amur tiger (Panthera tigris), lion (Panthera leo), Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata), ounce (Panthera uncia), red kangaroo (Macropus rufus), and orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus).

Species included Asiatic elephant (Elephans maximus), brown bear (Ursus arctos), polar bear (Thalarctos maritimus), wolverine (Gulo gulo), lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), white-mantled black colobus (Colobus guereza), mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx), Brazilian tapir (Tapirus terrestris), llama (Lama glama), bison (Bison bison), Yaku-shika deer (Cervus nippon), Sumatran tiger (Panthera tigris), leopard cat (Felis bengalensis), hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius), pigmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis), white rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simus), Barbary sheep (Ammotragus lervia), mountain zebra (Equus zebra), orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus), red-necked wallaby (Macropus rufogriseus), ostrich (Struthio camelus), emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), Californian sea lion (Zalophus californianus), uracoan rattle snake (Crotalus durissus), dwarf crocodile (Osteolaemus tetraspis), Galapagos tortoise (Geochelone nigra), and green iguana (Iguana iguana).

We also examined fresh contents of rumens and intestines (Table 5) of several livestock. Fifty-five individual ruminal contents of cattle in total were examined, and 53 gave Trp+ cultures, including 44 PCR+ cultures. Similarly, Trp+ PCR+ cultures were obtained from ruminal contents of goats (4 of 5 cultures) and horses (2 of 4 cultures) and the intestinal contents of pigs (14 of 33 cultures).

TABLE 5.

Numbers of Trp+ and PCR+ cultures obtained from contents of animal digestive organs

| Animal | Site of collectiona | No. tested | No. positive

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trp | PCR | |||

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | C | 51 | 49 | 40 |

| Cattle (Bos taurus) | S | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Goat (Capra hircus) | N | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Horse (Equus caballus) | C | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| Pig (Sus scrofa) | C | 31 | 22 | 14 |

Abbreviations: S, STAFF Institute; C, Chuou Meat Inspection Laboratory; N, Nihon University.

(iii) Feeds.

Although the above results strongly suggested that animal intestines are the original habitats of Symbiobacterium, the wide distribution among a variety of animal species raised the possibility that the origin is their feeds. In fact, similar experiments revealed that Trp+ PCR+ cultures were obtained not only from samples of hays prepared in an experimental farm and from commercial grains such as wheat and corn, but from 15 of 20 different commercial pellet-type feeds.

Phylogeny and DGGE analysis of the amplified 16S rDNA products.

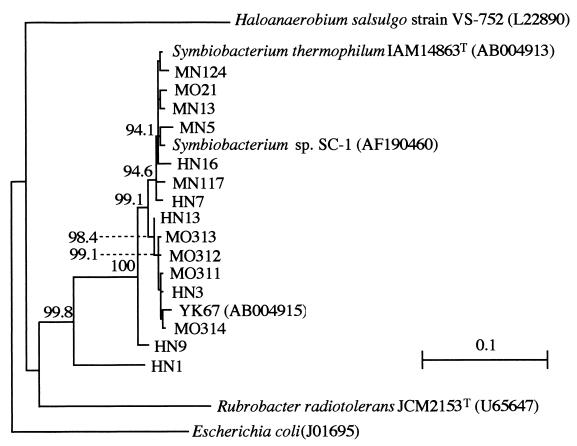

To evaluate the phylogenetic position and diversity of Symbiobacterium detected in this study, the 1.2-kb fragments of 16S rDNA were cloned from the randomly selected 31 amplicons derived from compost, soil, and feces, and each representative clone was sequenced (Table 6). Sequence alignment and successive phylogenetic analysis revealed that 15 clones were almost identical to that of S. thermophilum strain T (>99.5%), but the other 16 clones showed different extents of diversity, as shown in Fig. 2. While the 2 clones HN1 and HN9 respectively formed distinctly isolated branches, the other 14 clones fell into two subgroups, one including S. thermophilum strain T and the other including YK67 (9). The sequence of Symbiobacterium sp. strain SC-1 (6) fell into the same subgroup as strain T.

TABLE 6.

Symbiobacterium-specific clones sequenced randomly

| Clone no. | Clone name | Origin | % Similaritya | Length (nt) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MO87 | Compost (Fukushima) | 100.0 | 1,150 | AB052368 |

| 2 | YK88 | Compost (Fukushima) | 100.0 | 1,150 | AB052369 |

| 3 | YK63 | Compost (Kanagawa) | 100.0 | 1,150 | AB052370 |

| 4 | MO16 | Compost (Chiba) | 100.0 | 1,150 | AB052371 |

| 5 | YK1 | Soil (Kanagawa) | 100.0 | 1,150 | AB052372 |

| 6 | MO33 | Feces (cattle) | 100.0 | 1,057 | AB052373 |

| 7 | MO17 | Soil (Chiba) | 99.9 | 1,150 | AB052374 |

| 8 | MO22 | Feces (cattle) | 99.9 | 1,057 | AB052375 |

| 9 | YK2 | Soil (kanagawa) | 99.8 | 1,150 | AB052376 |

| 10 | YK66 | Soil (Tokyo) | 99.8 | 1,150 | AB052377 |

| 11 | HN15 | Feces (red kangaroo) | 99.8 | 1,057 | AB052378 |

| 12 | MO32 | Feces (cattle) | 99.7 | 1,057 | AB052379 |

| 13 | MN128 | Feces (oryx) | 99.7 | 1,057 | AB052380 |

| 14 | MO31 | Feces (cattle) | 99.7 | 1,057 | AB052381 |

| 15 | YK3 | Compost (Kanagawa) | 99.7 | 1,151 | AB052382 |

| 16 | MN13 | Feces (cattle) | 99.3 | 1,153 | AB052383 |

| 17 | MN124 | Feces (African elephant) | 99.2 | 1,057 | AB052384 |

| 18 | MN117 | Feces (reindeer) | 99.2 | 1,057 | AB052385 |

| 19 | MO21 | Feces (cattle) | 99.1 | 1,058 | AB052386 |

| 20 | HN7 | Feces (tiger) | 99.1 | 1,055 | AB052387 |

| 21 | MN5 | Feces (cattle) | 98.7 | 1,138 | AB052388 |

| 22 | HN13 | Feces (ounce) | 98.7 | 1,057 | AB052389 |

| 23 | MO312 | Compost (Chiba) | 98.4 | 1,057 | AB052390 |

| 24 | MO313 | Compost (Chiba) | 98.4 | 1,057 | AB052391 |

| 25 | MO314 | Compost (Chiba) | 98.1 | 1,057 | AB052392 |

| 26 | MO311 | Compost (Chiba) | 98.1 | 1,057 | AB052393 |

| 27 | HN3 | Feces (cheetah) | 98.1 | 1,057 | AB052394 |

| 28 | HN16 | Feces (orang utan) | 97.4 | 1,074 | AB052395 |

| 29 | HN9 | Feces (lion) | 97.2 | 1,057 | AB052396 |

| 30 | YK67 | Soil (Tokyo) | 96.9 | 1,155 | AB004915 |

| 31 | HN1 | Feces (Malayan tapir) | 85.5 | 1,022 | AB052397 |

Similarity to the sequence of S. thermophilum strain T is shown as percentage.

FIG. 2.

Unrooted tree showing phylogenetic branches of Symbiobacterium and the sequences isolated in this study. Symbiobacterium sp. strain SC-1 (6) is also included. The tree, constructed by the neighbor-joining method, was based on a comparison of aligned positions of 1,050 nucleotides (excluding deleted and ambiguously aligned sites). Each bootstrap value is expressed as a percentage of 1,000 replications. Values above 80% are given at branching points. The accession numbers of the sequences retrieved from database are shown in parentheses. Bar, 10% sequence divergence.

To assess the heterogeneity further, the Symbiobacterium-specific PCR products derived from different kinds of pellet-type animal feeds were subjected to DGGE analysis. Each 1.2-kb 16S rDNA amplicon was purified by extraction from agarose gel and used as a template for the PCR with DGGE primers followed by electrophoresis in the denaturing gradient gel (Fig. 3). The analysis showed that each PCR product consisted of multiple bands with different migration patterns, possibly reflecting the presence of different species or subspecies in each mixed culture. It was also evident that the band corresponding to the sequence of S. thermophilum strain T was commonly present in all the samples, while that of YK67 was absent.

FIG. 3.

DGGE patterns of the amplicons derived from commercial feeds. Lanes 1 and 2, amplicons derived from the cloned 16S rDNA of S. thermophilum strains T and YK67, respectively; lanes 3 to 12, amplicons derived from the various commercial feeds (lane 3, Manna Club [Kyodo Shiryo, Yokohama, Japan]; lanes 4 to 6, Winny A, M, and Z; lane 7, Neo-dairy Bulgy; lane 8, Kuro-ushi; lane 9, Bio-calf; lane 10, Meat DX; lane 11, beet pellet; lane 12, Neo-prechick [Nosan, Yokohama, Japan]).

DISCUSSION

The present study clearly demonstrated the wide distribuion of S. thermophilum and its relatives in compost, soil, animal intestinal contents, feces, and feeds. Because of the symbiotic nature, conventional cultivation methods could be adopted neither to definitive detection nor to isolation of the bacteria in environment. The difficulty was overcome by the PCR-based procedure enabling detection of the specific 16S rDNA sequences. Since all the amplicons randomly sequenced fell into the subgroups belonging to the discrete phylogenetic limb of Symbiobacterium (Fig. 2), the PCR primers designed according to the 16S rDNA sequence of S. thermophilum strain T were sufficiently specific to detect the group of bacteria. The primer stringency, however, may have rather limited the detection to the members relatively close to strain T, and thus even the high frequency of detection in this study may still underestimate the actual distribution of this group of bacteria.

Wide geographical distribution of Symbiobacterium was confirmed by its detection in compost and soil collected at regions covering latitudes between 43°N (Kushiro, Hokkaido) and 26°N (Naha, Okinawa) in Japan. That the detection frequency in compost was higher than that in soil may suggest that compost is a favorable niche for this group of bacteria not only due to the high temperatures but also due to the rich nutritional conditions. Furthermore, the frequent detection in intestinal contents and feces of a variety of animals strongly suggested that the animal intestinal tracts are the primary habitats of Symbiobacterium. The productivity of tryptophanase and tyrosine-phenol lyase (14–16) may be a reflection of the intestinal environment as seen with the Enterobacteriaceae. It is noteworthy that S. thermophilum shows better growth under anaerobic conditions (O2 < 2% [unpublished data]). However, our preliminary quantification of its population in cattle rumen fluids by quantitative PCR suggested its relatively low cell density (<105 cells per ml). Probably temperatures in the rumen as well as in other parts of the intestines are not sufficiently high to make this group of bacteria dominant. On the other hand, detection of Symbiobacterium from animal feeds including hays and grains raises the possibility that there is recycling between feeds and animal intestines. It seems possible that this group of bacteria may be ubiquitous, like Bacillus spores in the environment, but more extensive screening is required to settle this problem.

Similarly to the original isolation in 1988, bacteria belonging to Symbiobacterium sp. identified in this study were cocultured with other microbes, most of which were thermophilic Bacillus sp. This may indicate that the major growth-supporting organism for Symbiobacterium in nature is Bacillus. On the other hand, we recently revealed that growth-supporting activity for S. thermophilum is present in the culture supernatants of various bacterial species other than Bacillus (8). Thus, it is more likely that the growth of Symbiobacterium is supported by multiple organisms in the natural environments and that the aerobic cultivation at 60°C eliminated those organisms, resulting in the dominant proliferation of thermophilic Bacillus sp. as the major supporter for Symbiobacterium.

We determined the nucleotide sequences of 31 fragments of the 16S rDNA, in which half the population (15 of 31) was almost identical (>99.5%) to that of S. thermophilum strain T. The dominance was also strongly suggested by the DGGE pattern of the amplicons derived from feeds, in which a large part of the PCR products commonly contained the band corresponding to that of strain T. This result may reflect the actual dominance of S. thermophilum in nature, although we cannot exclude the possibility that it contains some bias of the primer selectivity in the specific PCR procedure.

The other 16 fragments exhibited different extents of diversity: HN1 fell into a remotely isolated position, while HN9 formed a branch within the genus Symbiobacterium. The other 14 sequences formed two closely related subgroups, one including S. thermophilum strain T and the other including YK67 (9). According to Stackebrandt and Goebel (13), different bacterial species are expected to share less than 97% identity in the 16S rDNA sequences. Thus, we may conclude that the sequences of HN1 and HN9, sharing 85.5 and 97.2% identity with that of strain T, respectively, are those of species different from S. thermophilum. It is also evident that a certain divergence exists between the two subgroups of strain T and YK67. The presence of diverged species different from S. thermophilum was also implicated by the result of DGGE analysis (Fig. 3), in which multiple bands other than that of strain T were observed.

In spite of the wide distribution, reports on isolation of the bacteria belonging to Symbiobacterium have been limited to ours except for one report from Korea (6). This apparently indicates that even a general culturable microbe could be easily left unrecognized because of its nature, such as the dependence on symbiosis. Further isolation and comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of Symbiobacterium species would contribute not only to the understanding of the bacterial diversity but also to the accumulation of genetic information available for industrial application.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the kind help offered by the members of the Tama zoo, the Ueno zoo, the Hosono Holstein Farm, and the Chuou Meat Inspection Laboratory of Gunma. We thank K. Yoshida, T. Nagamine, Y. Morita, N. Iwabuchi, H. Nishida, and M.-H Sung for helpful discussions.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (no. 06660091 and 08660121) and the High-Tech Research Center Project of The Ministry of Education, Science, Sports, and Culture, Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirahara T, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and overexpression in Escherichia coli of the β-tyrosinase gene from an obligately symbiotic thermophile, Symbiobacterium thermophilum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1993;39:341–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00192089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hirahara T, Suzuki S, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Cloning, nucleotide sequences, and overexpression in Escherichia coli of tandem copies of a tryptophanase gene in an obligately symbiotic thermophile, Symbiobacterium thermophilum. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:2633–2642. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.8.2633-2642.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Imanaka T, Fujii M, Aiba S. Isolation and characterization of antibiotic resistance plasmids from thermophilic bacilli and construction of deletion plasmids. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:1091–1097. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.1091-1097.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kudo H, Natsume R, Nishiyama M, Horinouchi S. Analysis of stability and catalytic properties of two tryptophanases from a thermophile. Protein Eng. 1999;12:687–692. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.8.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee S-G, Hong S-P, Choi Y-H, Chung Y-J, Sung M-H. Thermostable tyrosine phenol-lyase of Symbiobacterium sp. SC-1: gene cloning, sequence determination, and overproduction in Escherichia coli. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;11:263–270. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muyzer G, De Waal E C, Uitterlinden A G. Profiling of complex microbial populations by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis analysis of polymerase chain reaction-amplified genes coding for 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:695–700. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.3.695-700.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohno M, Okano I, Watsuji T, Kakinuma T, Ueda K, Beppu T. Establishing the independent culture of a strictly symbiotic bacterium, Symbiobacterium thermophilum, from its supporting Bacillus strain. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1999;63:1083–1090. doi: 10.1271/bbb.63.1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohno M, Shiratori H, Park M-J, Saito Y, Kumon Y, Yamashita N, Hirata A, Nishida H, Ueda K, Beppu T. Symbiobacterium thermophilum gen. nov., sp. nov., a symbiotic thermophile that depends on co-culture with a Bacillus strain for growth. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1829–1832. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perriere G, Gouy M. WWW-query: an on-line retrieval system for biological sequence banks. Biochimie. 1996;78:364–369. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)84768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saito H, Shibata T, Ando T. Mapping of genes determining nonpermissiveness and host-specific restriction to bacteriophages in Bacillus subtilis Marburg. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;170:117–122. doi: 10.1007/BF00337785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stackebrandt E, Goebel B M. Taxonomic note: a place for DNA-DNA reassociation and 16S rRNA sequence analysis in the present species definition in bacteriology. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:846–849. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki S, Hirahara T, Shim J-K, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Purification and properties of thermostable β-tyrosinase from an obligately symbiotic thermophile, Symbiobacterium thermophilum. Biosci Biotech Biochem. 1992;56:84–89. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suzuki S, Hirahara T, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Purification and properties of thermostable tryptophanase from an obligately symbiotic thermophile, Symbiobacterium thermophilum. Agric Biol Chem. 1991;55:3059–3066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suzuki S, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Growth of a tryptophanase-producing thermophile, Symbiobacterium thermophilum gen. nov., sp. nov., is dependent on co-culture with a Bacillus sp. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:2353–2362. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighing, positions-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]