Abstract

Hidradenitis suppurativa has a substantial negative effect on quality of life of affected persons. Diagnosis is based mainly on clinical examination. However, physical examination alone might underestimate disease severity compared with imaging modalities. We report here the application of non-contrast-enhanced 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging using surface-coil and sonography for assessment of hidradenitis suppurativa lesions based on topographic assessment of skin lesions. In addition, we review the literature regarding the application of ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging in hidradenitis suppurativa.

Key words: 3-Tesla, hidradenitis suppurativa, MRI, sonography, surface coil, treatment

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a debilitating, recurrent, inflammatory dermatological disorder, which reduces quality of life, with physical, emotional, and psychological consequences (1–3). The clinical manifestations of HS range from recurrent inflamed nodules and abscesses to draining sinus tracts and scar formation (3). The associated pain, drainage, malodour and disfigurement contribute to a remarkable psychosocial impact of the disease (3, 4). Diagnosis, clinical evaluation, current staging and follow-up of HS are based mainly on physical examination of palpable and visible lesions (5, 6). However, physical examination alone usually underestimates disease severity compared with imaging modalities (7–9). In addition, surgical treatment of HS could benefit from radiological modalities with a higher sensitivity, enabling better detection of the extent of HS involvement (6–9). Furthermore, improved knowledge of HS lesions might aid in the selection of appropriate treatments and more precise disease monitoring, which could improve clinical outcomes (7–9). This study reports the simultaneous application of sonography and non-contrast-enhanced 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) using surface-coil in a patient with moderate-to-severe HS (Hurley stage II) to assess the topography of the skin lesions. Furthermore, a review of the literature is presented regarding the application of sonography and MRI in HS.

SIGNIFICANCE

Magnetic resonance imaging and sonography are the main non-invasive imaging modalities for treatment selection, preoperative planning, and evaluation of effectiveness of therapy in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. We report here the application of non-contrast-enhanced 3-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging using surface-coil and sonography for assessment of hidradenitis suppurativa lesions based on topographic assessment of skin lesions.

CASE REPORT

A 34-year-old woman presented with a history of recurrent painful lesions in the axillae, genital and gluteal area for 4 years. She was a smoker and overweight. She had multiple inflamed nodules, comedones and scar formation in typical locations for HS (Hidradenitis suppurativa Hurley II) (Figs 1 and 2). In order to better assess the superficial cutaneous and subcutaneous structures in the axillae, ultrasound was performed using an Acuson Sequoia ultrasound system (Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a Linear 9 MHz transducer (Figs 1 and 2). This revealed bilateral dermal thickening together with some small dermal fluid collection up to 10 mm, with no sign of fistula formation on the left axilla. In order to complement the results of sonography, a surface-coil MRI was performed to assess the topography of the skin lesions. Surface-coil MRI enables high-resolution imaging of superficial structures, such as the skin, owing to its high signal-to-noise ratio. As result, a non-contrast-enhanced MRI was performed using a 3-T MRI scanner (Magnetom Prisma; Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a surface shoulder coil. Optimized turbo inversion recovery magnitude (TIRM) blade and proton density turbo spin echo (PD-TSE) fat suppressed sequences, in axial and coronal planes (Table I), were performed. MRI scan of the right/left axilla revealed dermal thickening on the coronal and axial sequences, with suspicion of the beginning of tiny sinus tract formation on the coronal acquisition in the right side and small fluid formation on the coronal acquisition in the left side (Figs 1 and 2).

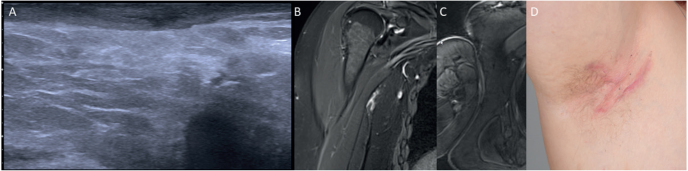

Fig. 1.

Right shoulder. (A) Sonography: dermal thickening without fluid collection or fistula formation. (B, C) Magnetic resonance imaging: Both pictures show dermal thickening in the coronal and axial sequences, with suspicion of beginning of tiny sinus tract formation on the coronal acquisition. (B) TIRM (Turbo-Inversion Recovery-Magnitude) blade coronal right; (C) T2 Blade FS (Fat Suppressed) axial. (D) Clinical image.

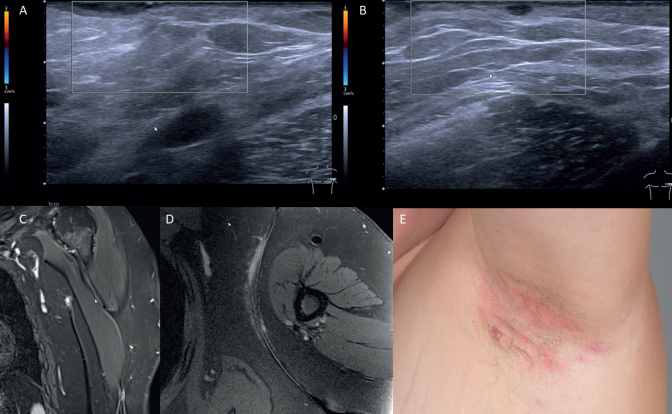

Fig. 2.

Left shoulder. (A, B) Sonography: in addition to routine ultrasound (US) imaging, power Doppler and colour Doppler ultrasound modalities can be utilized to visualize hidradenitis suppurativa lesions and differentiate nearby vasculature. Ultrasound shows dermal thickening with some small dermal fluid collection up to 10 mm without sign of fistula formation. (C, D) Magnetic resonance imaging: both pictures show diffuse infiltrating dermal thickening in the axial sequences, with small fluid formation on the coronal acquisition. No fistula formation. (C) TIRM (Turbo-Inversion Recovery-Magnitude) blade coronal. (D) PD (Proton Density) TSE (Turbo Spin Echo) FS (Fat Suppressed) axial. (E) Clinical image.

Table I.

Parameters for surface coil magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

| Parameter | TIRM blade | PD TSE FS |

|---|---|---|

| Repetition time (ms) | 3930 | 3000 |

| Echo time (ms) | 45 | 34 |

| Slice thickness (mm) | 3 | 3 |

| Inversion time (ms) | 220 | 220 |

| Field of view (mm) | 200x200 | 150x150 |

TIRM: turbo inversion recovery magnitude; PD TSE FS: proton density turbo spin echo fat suppressed.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Search strategy

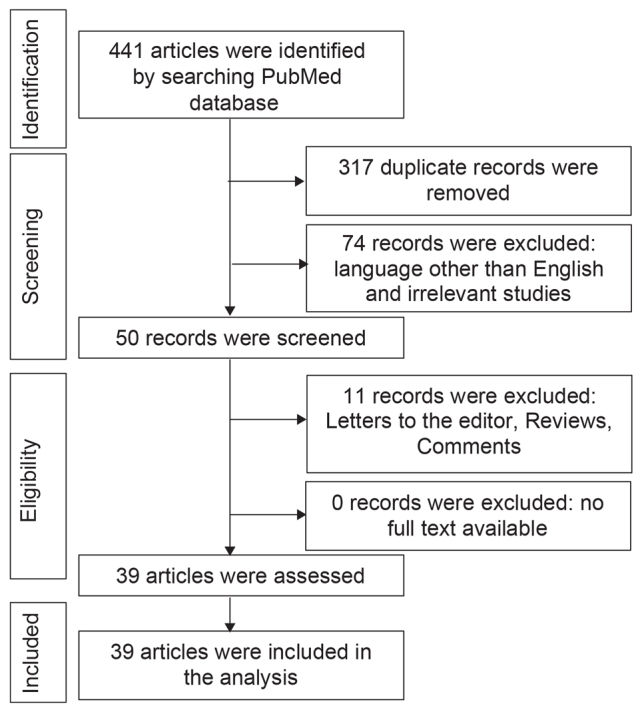

A review was carried out following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (10) (Fig. 3). The literature search was conducted in PubMed from January 2000 to April 2020, using the following search terms, their synonyms or respective combinations: acne inversa, hidradenitis suppurativa, sonography, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, and MRI.

Fig. 3.

Flow of information during the review.

Study selection and data collection

A database was made of the initial results, using Microsoft Excel. Title, abstracts and publication type were screened for inclusion in full-text assessment. Criteria leading to study exclusion were: language (other than English), comments, and non-human studies. The selected studies were then summarized chronologically in a table to show the advances made over time (Tables II and III). Finally, the main emerging topics regarding the application of MRI and ultrasound in HS were discussed in more detail.

Table II.

Summary of selected studies that showed application of sonography in hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)

| Year | Study | Patients n | Selected radiological method | Frequency of probe | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | Jemec & Gniadecka (12) | 15 HS; 13 HC | US | 20 MHz | US shows characteristic differences in the shape of hair follicles in HS. A thickened skin may play a pathogenic role in the development of HS. |

| 2004 | Wortsman, et al. (11) | 21 VSD; 13 HC | US | Linear 15–7 MHz; linear 12–5 MHz | US allows objective, accurate, non-invasive and easy measurements of several parameters of skin morphology. |

| 2007 | Wortsman, et al. (17) | 7 HS | US | Linear 15.7- MHz; linear 17.5- MHz | US shows a number of HS features and can identify the true extent of lesions in HS, which may be of use in preoperative planning. |

| 2009 | Wortsman, et al. (31) | 10 HS | US | Linear 15–7 MHz; linear 12–5 MHz | Lymph node involvement only occurs with late-stage HS and may therefore reflect secondary infection rather than primary aetiological involvement. |

| 2010 | Kelekis, et al. (28) | 19 HS | US | Linear 7–12 MHz | US aids in diagnosis and severity assessment of HS. |

| 2012 | Kolodziejczak, et al. (43) | 51 HS | US | Linear 6–12 MHz; Endoprobe 10–16 MHz | TPUS is an accessible imaging method, which confirms the typical localization of changes of HS, and together with AUS it allows for the proper differentiation of HS from an anal fistula or an abscess. |

| 2013 | Wortsman, et al. (16) | 25 HS | US | Linear 7–15 MHz; linear 7–18 MHz | A 3D US can show the sinus tract formation in HS. |

| 2013 | Wortsman, et al. (8) | 34 HS | US | Linear 7–18 MHz | US is useful for HS staging. |

| 2015 | Wortsman & Wortsman (14) | 50 HS | US | Linear 16 MHz; linear 18 MHz | Ultrasound can detect retained hair tracts in HS. |

| 2015 | Zarchi, et al. (30) | 20 HS | US | Linear 6–18 MHz and linear 10–22 MHz | Pain and inflammation in HS correspond to morphological changes identified by US. |

| 2016 | Wortsman, et al. (40) | 52 HS | US (+ CD) | Linear upper range up to 18 MHz | Fistulous tracts in HS can be categorized using US, which may support earlier and precise management. |

| 2016 | Wortsman, et al. (19) | 12 HS | CD | Upper range up to 16 and 18 MHz | US can be a reliable and safe imaging tool to support diagnosis, staging and non-invasive monitoring of treatment in children with HS. |

| 2017 | Wortsman, et al. (34) | 43 PC; 41 HS | CD | Upper range up to 16 and 18 MHz | Key lesions of PC and HS have similar sonographic morphological characteristics, which suggests that a PC may be a variant or localized form of HS. |

| 2018 | Caposiena Caro, et al. (6) | 61 HS | CD (+ PD) | Linear 10–18 MHz | Vascular distribution of HS lesions can be evaluated by PD with additional relevant information for earlier and better disease management. |

| 2018 | Loo, et al. (20) | 62 HS | US | NM | US can add diagnostic information to the clinical and biochemical characteristics of patients with HS. |

| 2018 | Nazzaro, et al. (36) | 140 HS | US | Linear 18–5-MHz | Ultrasonography may reveal non-clinically evident HS lesions. |

| 2018 | Nazzaro, et al. (37) | 140 HS | US | NM | There is a relevant disagreement between clinical and US scores. US might discover non-clinically evident HS lesions, notably fistulae. |

| 2018 | Kanni, et al.(45) | 20 HS | US | Linear 7–12-MHz | US observations could be used to assess the efficacy of MABp1 therapy in HS. |

| 2019 | Lacarrubba, et al. (35) | 434 HS | US | 14–20 MHz | The use of clinical grading only to assess HS severity may underestimate the real disease severity. |

| 2019 | Lyons, et al. (42) | 1 HS | US | 8–18 MHz | Pre-operative US can aid in evaluation of HS. |

| 2019 | Martorell, et al. (15) | 143 HS | US | Linear upper range up to 18 MHz | US can modify the clinical staging and therapeutic management in HS by detecting subclinical disease. |

| 2019 | Martorell, et al. (38) | 117 HS | US | 18 MHz | The US evaluation seems to play an important role to define the fistular patterns. |

| 2019 | Napolitano, et al. (7) | 124 HS | US | NM | US seems to have good agreement with clinical assessment of HS. |

| 2019 | Nazzaro, et al. (32) | 24 Hs | US (+CD) | NM | The study shows the correlation between vascularization of HS lesions assessed with CD and local pain. |

| 2019 | Nazzaro, et al. (46) | 180 HS | US | 18–5 MHz | US in HS might highlight the rational for permanent hair laser removal. |

| 2019 | Oranges, et al. (56) | 50 HS | US | 48 MHz; 70 MHz | UHFUS provides a better understanding of HS. Patients can be monitored more effectively, thereby preventing the most severe changes. |

| 2019 | Wortsman, et al. (18) | 139 HS | US | Linear 15 MHz; linear 18 MHz; linear 70 MHz | US can detect early signs of HS that are linked to severity and 2 types of fragmentation of the keratin, which could support the generation and perpetuation of the fluid collections and tunnels. |

| 2019 | Zussino, et al. (33) | 3 Hs | US (+ CD) | NM | The combination of US and CD seems to be a reliable instrument for differentiating between steatocystoma multiplex and HS lesions, particularly distinguishing HS pseudocystic nodules from true cysts of steatocystoma multiplex |

| 2019 | Caposiena Caro, et al. (44) 60 Hs | US | NM | US observations could be used to assess the efficacy of clindamycin versus clindamycin plus rifampicin in HS treatment. | |

| 2020 | Álvarez, et al. (57) | 53 HS | US | NM | US observations could be used to assess the efficacy of intralesional triamcinolone for fistulous tracts in HS. |

| 2020 | Cuenca-Barrales, et al. (41) | 40 HS | US | Linear 7–15 MHz | Preoperative ultrasonography improves surgical margin delimitation and can lower recurrence rates. |

| 2020 | Nazzaro, et al. (58) | 1 HS | IT and CD | NM | Role of infrared thermography in combination with CD seems to be a reliable tool for detecting the intensity of inflammation in HS. |

AUS: anal ultrasonography; CD: colour Doppler; HS: suppurativa; HC: healthy control; IT: infrared thermography; NM: not mentioned; PC: pilonidal cysts; PD: power Doppler; TPUS: transperineal ultrasonography; UHFUS: ultra-high frequency ultrasound; US: ultrasound; VSD: various skin diseases; 3D: three-dimensional.

Table III.

Summary of selected studies that showed application of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in hidradenitis suppurativa (HS)

| Year | Study | Patients n | Selected radiologic method | Scanner | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | Kelly, et al. (29) | 1 HS | MRI | On a 1.5-T scanner | MRI shows important features of HS. |

| 2014 | Griffin, et al. (50) | 18 HS | MRI | On a 1.5-T scanner | MRI may help define the extent of anogenital disease and assess response to treatment. |

| 2014 | Poh, et al. (5) | 1 HS | MRI | NM | MRI shows important features and complications of HS. |

| 2015 | Takiyama, et al. (49) | 2 HS | MRI | NM | Perianal HS with complicated anal fistulae can be diagnosed using MRI and treated safely. |

| 2015 | Virgilio, et al. (52) | 1 HS | MRI | NM | MRI can be used in the diagnosis and post-treatment evaluation of anogenital HS. |

| 2017 | Monnier, et al. (51) | 23 HS; 46 CD | MRI | On a 1.5-T scanner | MRI features can help in differentiation of HS and CD. |

| 2018 | Derruau, et al. (53) | 1 HS | MRI | On a 1.5-T scanner | Combining MRI and IT could help to distinguish healthy tissues and inflammatory sites during excision. |

CD: Crohn’s disease; IT: infrared thermography; NM: not mentioned; T: Tesla.

RESULTS

A total of 441 articles were identified. Screening of the abstracts were results in exclusion of 391 articles. After full-text evaluation of the remaining 50 articles, a final total of 39 articles were included in this study (Fig. 3, Tables II and III).

Ultrasound imaging

Ultrasound is a non-invasive real-time method based on the propagation and return of sound waves in different tissues (6). Ultrasound could be of use in dermatology, by enabling physicians to visualize skin tissue and cutaneous lesions, according to their echogenicity (6, 11). Ultrasound imaging has been utilized for over 20 years in assessment of HS lesions (9, 12). During this time, ultrasound imaging of HS has advanced HS diagnosis, management and follow-up (6, 9, 12–17). The most commonly used ultrasound equipment for evaluating HS has a maximum frequency range of 15–22 MHz (18).

Ultrasound to determine the pathogenesis and clinical signs of hidradenitis suppurativa

US can reliably and non-invasively support better understanding the pathogenesis and diagnosis of HS, through real-time assessment of the characteristics, extension, and relationship of HS lesions with the surrounding tissues (19, 20). The anatomical information obtained with US supports our histological understanding of the evolution of HS (16).

The exact pathogenetic mechanism of HS remains unclear (3, 21). The primary event in disease development is thought to be follicular occlusion, based on histopathological observations in very early lesions (3, 22, 23). Follicular occlusion is probably caused by infundibular keratosis and hyperplasia of the follicular epithelium, which results in accumulation of cellular debris and formation of cysts (3, 22, 24–26). Eventually, the hair follicle ruptures, followed by introduction of follicular contents to the surrounding dermis, which induces significant expression of inflammatory mediators and recruitment of inflammatory cells (3, 22, 24–26). Similar to the histological findings, the observed primary widening of hair follicles (probably due to the presence of follicular and perifollicular inflammation, and the increased size of the hair shafts, may be secondary to dysregulation of the production of keratin) seen on ultrasound, followed by dermal thickening and/or diffuse alteration of dermal echogenicity pattern (which reflects the underlying painful inflammatory process), formation of pseudocysts in dermis (round or oval-shaped hypoechoic or anechoic nodular structures), fluid collection (anechoic or hypoechoic fluid deposits in the dermis or hypodermis connected to the base of widened hair follicles), and fistulous tracts (anechoic or hypoechoic band-like structures across skin layers in the dermis or hypodermis connected to the base of widened hair follicles) (3, 8, 9, 11, 12, 14, 16–20, 27–30). In addition, HS is an inflammatory disease, and yet palpable lymph nodes are rarely found clinically. However, ultrasound could be used to identify and measure regional lymph nodes in patients with HS, especially late-stage HS (31).

Doppler sonography

The combination of ultrasound and colour Doppler could provide additional information about HS lesions, such as vasculature components and inflammation, which might be correlated with local pain (6, 32). Furthermore, colour Doppler sonography might help to provide significant anatomical evidence and differentiate among steatocystoma multiplex, pilonidal cysts and HS lesions (33, 34).

Grading and assessment of severity using ultrasound

The accurate evaluation of disease severity is an important and challenging task in HS (30). Clinical scoring based on physical findings is easy, but provides insufficient detail on the severity of HS (8). Ultrasound might add important findings in diagnosis and severity assessment of HS (28). As a result, Wortsman et al. recommended a sonographic scoring system for HS (SOS-HS) to define disease severity. SOS-HS combined the results of parameters included in Hurley’s clinical staging with the relevant sonographic findings, i.e. number and distribution of fluid collections, fistulous tracts, pseudocystic nodules, widening of the hair follicles and changes in dermal thickness/echogenicity (8, 27). More recently, the 5 main lesions detectable by US have been validated: pseudocyst, fistulous tract, fluid collection, connected fistulous tracts, and hair tracts (13, 35). Using this score, recent studies have demonstrated a relevant disagreement between clinical and ultrasonography scores, due to the greater sensitivity of ultrasonography (7, 15, 30, 36, 37). Physical examination alone significantly underestimates the severity of HS and ultrasound-discovered subclinical HS lesions, notably fistulous tracts, which reflect a more aggressive disease (7, 15, 17, 30, 37–40).

Pre-operative planning using ultrasound

Surgical removal (or possibly laser therapy) can be used to remove lesional tissue with long-term inflammatory damage (3, 12, 17, 41). The size of the excision is important to improve clinical outcome and reduce the recurrence rate (12, 41). Current preoperative assessment of the necessary excision size is based mainly on clinical evaluation by the dermatologist and/or surgeon (12). However, a more exact preoperative assessment of the lesions and involved area of the skin could minimize the size of the excision, morbidities and recurrence rate (12). Clinical scoring of HS may underestimate the true extent of the disease, since visual examination and palpation pose difficulties in determining the presence of deeper lesions (42). Ultrasound can help to identify the location, size, and shape of the affected area and exclude other possible diagnosis (9, 12, 42, 43). Cuenca-Barrales et al. (41) showed recently that the use of pre-operative ultrasound planning in surgical management of HS improves surgical margin delimitation and reduces recurrence rates at 24 weeks. This highlights the importance of a pre-operative evaluation to precisely identify excision targets and elaborate personalized surgical management of patients with HS to minimize the risk of recurrence (38, 42).

Use of ultrasound in planning and monitoring therapy

Notable associations between morphological changes identified using ultrasound and patient assessments of flare activity and pain suggest that these parameters might be strong indicators of the degree of inflammation in HS (30). Thus, ultrasound might also be also useful in treatment response monitoring and follow-up, by non-invasively observing and measuring the number and size of lesions, reduction/disappearance of fluid collections, and fistulous tracts or a decrease/lack of Doppler activity (8, 15, 35, 40, 44). Clinical studies have used ultrasound to monitor the efficacy of systemic and local therapies as intralesional triamcinolone, clindamycin plus rifampicin and MABp1 (a human monoclonal antibody that neutralizes IL-1a) (41, 44, 45). Since a high prevalence of retained hair tract, detected by ultrasound confirms the pathogenic role of hair follicle as a foreign body that stimulates chronic inflammation in HS, permanent hair removal might be suggested to all patients with mild-tomoderate HS (8, 14, 46).

Limitations of ultrasound in hidradenitis suppurativa

Clear delineation between HS lesions, acne, folliculitis or cutaneous nodules using ultrasound findings may not be easy (27, 30, 42, 43, 47). In addition, ultrasound may not always be the best method for distinguishing HS fistulas from rectal fistulas or abscesses (27, 30, 42, 43, 47). In addition, ultrasound has limited ability to detect very small and/or very deep HS lesions (size/depth depends on sample frequency), which may impact on initial detection (8, 27, 30, 42, 43, 47). Furthermore, the correct use of ultrasound in HS, obtaining high-quality images and standardizing reporting requires specific training and a longer time than simple clinical examination (35, 42).

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI uses the magnetic properties of the body, specifically hydrogen atoms present in water and fat, to produce an image (9, 48). MRI has been used in the diagnosis and treatment of severe and complex HS lesions for over a decade (9, 29, 48). As a result of increased inflammation, HS changes the water content of the tissue (9, 49). Such areas appear to consist of subcutaneous networks of sinus tracts, which are visible on MRI due to the high contrast resolution (9, 49).

Magnetic resonance imaging in determining pathogenesis of hidradenitis suppurativa and in clinical use

The MRI findings of HS could be relatively non-specific, including marked thickening of the skin, induration of the subcutaneous tissues, and formation of multiple subcutaneous abscesses (5, 29). In the presence of anogenital involvement, MRI could help define the extent of HS and its associated complications, and may help exclude other differential possibilities, such as Crohn’s disease (50, 51). Furthermore, MRI also provides important additional information by a remarkable visualization of local enlarged lymph nodes, abscesses, and sinus tracts involving the rectum or other pelvic organs (5, 29, 49–52). In addition, this non-invasive method may determine whether medical therapy needs to be escalated or whether surgical intervention is required (50). If surgery is indicated, MRI might also be used for preoperative assessment to avoid post-surgical recurrence or complications (42, 49, 50, 53).

High-resolution magnetic resonance imaging using surface coils

Surface coils are used in MRI to better receive the radio-frequency signal, as they are more sensitive to signals close to the coil, thus detecting signals from organs of interest more efficiently (54). There is a wide range of MRI coil types, which have good signal-to-noise ratio for the tissue adjacent to the coil (54). Therefore, detection of magnetic resonance signals with surface coils provides increased signal-to-noise ratio for superficial structures, such as skin layers and their abnormalities (54, 55). Different geometries of surface coils can be used for different regions. Coils that are flat or curved to fit body contours are useful for general imaging, with a range of coil sizes for structures of different sizes or depths (55).

Conclusion

Ultrasound and MRI are the main modalities of imaging commonly used in patients with HS (9). Ultrasound is a well-stablished, non-invasive imaging method that has improved the assessment of disease severity, treatment selection, preoperative planning, evaluation of therapy effectiveness and monitoring of HS complications through real-time assessment of the features, extension and relationship of HS lesions with the surrounding tissues (5, 9, 19, 20, 35).

In addition, ultra-high-frequency ultrasound can help improve our understanding of the evolution of HS from early to advanced stages and thus contribute to understanding of the pathogenesis and early diagnosis of HS (18, 56). Using MRI localization, the depth, size and number of the HS lesions, especially fistulas and sinus tracts, could be assessed more precisely compared with ultrasound, due to the high-contrast resolution. Furthermore, disease activity parameters, such as expansion, local oedema, tissue inflammation and scar formation might be evaluated better using MRI, compared with ultrasound. As MRI is not user-dependent, it is a more practical technique to follow patients and analyse their therapy responses. In addition, MRI is a recommend radiological modality for specific localizations, such as the anogenital area. As a result, MRI can be used to evaluate the distribution of HS lesions, perform correct staging, select the proper treatment and for pre-surgical planning. MRI findings include thickening of the skin, induration of the subcutaneous tissue and multiple abscesses. However, MRI should be reserved for complex and challenging cases, especially in the presence of anogenital involvement.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The included patient in the current study read and provided signed informed consent.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seyed Jafari SM, Knusel E, Cazzaniga S, Hunger RE. A retrospective cohort study on patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology 2018; 234: 71–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Houriet C, Seyed Jafari SM, Thomi R, Schlapbach C, Borradori L, Yawalkar N, et al. Canakinumab for severe hidradenitis suppurativa: preliminary experience in 2 cases. JAMA Dermatol 2017; 153: 1195–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seyed Jafari SM, Hunger RE, Schlapbach C. Hidradenitis suppurativa: current understanding of pathogenic mechanisms and suggestion for treatment algorithm. Front Med (Lausanne) 2020; 7: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jemec GB, Heidenheim M, Nielsen NH. Hidradenitis suppurativa – characteristics and consequences. Clin Exp Dermatol 1996; 21: 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poh F, Wong SK. Imaging of hidradenitis suppurativa and its complications. Case Rep Radiol 2014; 2014: 294753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caposiena Caro RD, Solivetti FM, Bianchi L. Power Doppler ultrasound assessment of vascularization in hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 1360–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napolitano M, Calzavara-Pinton PG, Zanca A, Bianchi L, Caposiena Caro RD, Offidani AM, et al. Comparison of clinical and ultrasound scores in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: results from an Italian ultrasound working group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: e84–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wortsman X, Moreno C, Soto R, Arellano J, Pezo C, Wortsman J. Ultrasound in-depth characterization and staging of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg 2013; 39: 1835–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elkin K, Daveluy S, Avanaki K. Review of imaging technologies used in Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Skin Res Technol 2020; 26: 3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 264–269, w64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wortsman XC, Holm EA, Wulf HC, Jemec GB. Real-time spatial compound ultrasound imaging of skin. Skin Res Technol 2004; 10: 23–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jemec GB, Gniadecka M. Ultrasound examination of hair follicles in hidradenitis suppurativa. Arch Dermatol 1997; 133: 967–970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martorell A, Wortsman X, Alfageme F, Roustan G, Arias-Santiago S, Catalano O, et al. Ultrasound evaluation as a complementary test in hidradenitis suppurativa: proposal of a standarized report. Dermatol Surg 2017; 43: 1065–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wortsman X, Wortsman J. Ultrasound detection of retained hair tracts in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg 2015; 41: 867–869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martorell A, Alfageme Roldan F, Vilarrasa Rull E, Ruiz-Villaverde R, Romani De Gabriel J, Garcia Martinez F, et al. Ultrasound as a diagnostic and management tool in hidradenitis suppurativa patients: a multicentre study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: 2137–2142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wortsman X, Jemec G. A 3D ultrasound study of sinus tract formation in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Online J 2013; 19: 18564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wortsman X, Jemec GB. Real-time compound imaging ultrasound of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg 2007; 33: 1340–1342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wortsman X, Calderon P, Castro A. Seventy-MHz ultrasound detection of early signs linked to the severity, patterns of keratin fragmentation, and mechanisms of generation of collections and tunnels in hidradenitis suppurativa. J Ultrasound Med 2019; 39: 845–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wortsman X, Rodriguez C, Lobos C, Eguiguren G, Molina MT. Ultrasound diagnosis and staging in pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa. Ped Dermatol 2016; 33: e260–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Loo CH, Tan WC, Tang JJ, Khor YH, Manikam MT, Low DE, et al. The clinical, biochemical, and ultrasonographic characteristics of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa in Northern Peninsular Malaysia: a multicenter study. Int J Dermatol 2018; 57: 1454–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hunger RE, Laffitte E, Lauchli S, Mainetti C, Muhlstadt M, Schiller P, et al. Swiss practice recommendations for the management of hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa. Dermatology 2017; 233: 113–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prens E, Deckers I. Pathophysiology of hidradenitis suppurativa: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015; 73: S8–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vekic DA, Cains GD. Hidradenitis suppurativa – management, comorbidities and monitoring. Aust Fam Physician 2017; 46: 584–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Laffert M, Stadie V, Wohlrab J, Marsch WC. Hidradenitis suppurativa/acne inversa: bilocated epithelial hyperplasia with very different sequelae. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim SYD, Oon HH. Systematic review of immunomodulatory therapies for hidradenitis suppurativa. Biologics 2019; 13: 53–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Napolitano M, Megna M, Timoshchuk EA, Patruno C, Balato N, Fabbrocini G, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: from pathogenesis to diagnosis and treatment. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2017; 10: 105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wortsman X. Imaging of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin 2016; 34: 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelekis NL, Efstathopoulos E, Balanika A, Spyridopoulos TN, Pelekanou A, Kanni T, et al. Ultrasound aids in diagnosis and severity assessment of hidradenitis suppurativa. Br J Dermatol 2010; 162: 1400–1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly AM, Cronin P. MRI features of hidradenitis suppurativa and review of the literature. Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185: 1201–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zarchi K, Yazdanyar N, Yazdanyar S, Wortsman X, Jemec GB. Pain and inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa correspond to morphological changes identified by high-frequency ultrasound. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2015; 29: 527–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wortsman X, Revuz J, Jemec GB. Lymph nodes in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatology 2009; 219: 22–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nazzaro G, Passoni E, Calzari P, Barbareschi M, Muratori S, Veraldi S, et al. Color Doppler as a tool for correlating vascularization and pain in hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. Skin Res Technol 2019; 25: 830–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zussino M, Nazzaro G, Moltrasio C, Marzano AV. Coexistence of steatocystoma multiplex and hidradenitis suppurativa: assessment of this unique association by means of ultrasonography and color Doppler. Skin Res Technol 2019; 25: 877–880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wortsman X, Castro A, Morales C, Franco C, Figueroa A. Sonographic comparison of morphologic characteristics between pilonidal cysts and hidradenitis suppurativa. J Ultrasound Med 2017; 36: 2403–2418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lacarrubba F, Dini V, Napolitano M, Venturini M, Caposiena Caro DR, Molinelli E, et al. Ultrasonography in the pathway to an optimal standard of care of hidradenitis suppurativa: the Italian Ultrasound Working Group experience. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2019; 33: S10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nazzaro G, Passoni E, Guanziroli E, Casazza G, Muratori S, Barbareschi M, et al. Comparison of clinical and sonographic scores in a cohort of 140 patients with hidradenitis suppurativa from an Italian referral centre: a retrospective observational study. Eur J Dermatol 2018; 28: 845–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nazzaro G, Passoni E, Muratori S, Moltrasio C, Guanziroli E, Barbareschi M, et al. Comparison of clinical and sonographic scores in hidradenitis suppurativa and proposal of a novel ultrasound scoring system. G Ital Dermatol Venereol 2018. Oct 4 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martorell A, Giovanardi G, Gomez-Palencia P, Sanz-Motilva V. Defining fistular patterns in hidradenitis suppurativa: impact on the management. Dermatol Surg 2019; 45: 1237–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zouboulis CC, Tzellos T, Kyrgidis A, Jemec GBE, Bechara FG, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, et al. Development and validation of the International Hidradenitis Suppurativa Severity Score System (IHS4), a novel dynamic scoring system to assess HS severity. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 1401–1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wortsman X, Castro A, Figueroa A. Color Doppler ultrasound assessment of morphology and types of fistulous tracts in hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 760–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cuenca-Barrales C, Salvador-Rodriguez L, Arias-Santiago S, Molina-Leyva A. Pre-operative ultrasound planning in the surgical management of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2020; 34: 2362–2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lyons AB, Zubair R, Kohli I, Hamzavi IH. Preoperative ultrasound for evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg 2019; 45: 294–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kolodziejczak M, Sudol-Szopinska I, Wilczynska A, Bierca J. Utility of transperineal and anal ultrasonography in the diagnostics of hidradenitis suppurativa and its differentiation from a rectal fistula. Postepy Hig Med Dosw (Online) 2012; 66: 838–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Caposiena Caro RD, Cannizzaro MV, Botti E, Di Raimondo C, Di Matteo E, Gaziano R, et al. Clindamycin versus clindamycin plus rifampicin in hidradenitis suppurativa treatment: clinical and ultrasound observations. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 1314–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kanni T, Argyropoulou M, Spyridopoulos T, Pistiki A, Stecher M, Dinarello CA, et al. MABp1 Targeting IL-1alpha for moderate to severe hidradenitis suppurativa not eligible for adalimumab: a randomized study. J Invest Dermatol 2018; 138: 795–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nazzaro G, Zerboni R, Passoni E, Barbareschi M, Marzano AV, Muratori S, et al. High-frequency ultrasound in hidradenitis suppurativa as rationale for permanent hair laser removal. Skin Res Technol 2019; 25: 587–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Halani S, Foster FS, Breslavets M, Shear NH. Ultrasound and infrared-based imaging modalities for diagnosis and management of cutaneous diseases. Front Med 2018; 5: 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berger A. Magnetic resonance imaging. BMJ 2002; 324: 35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Takiyama H, Kazama S, Tanoue Y, Yasuda K, Otani K, Nishikawa T, et al. Efficacy of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of perianal hidradenitis suppurativa, complicated by anal fistulae: a report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep 2015; 15: 107–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Griffin N, Williams AB, Anderson S, Irving PM, Sanderson J, Desai N, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: MRI features in anogenital disease. Dis Colon Rectum 2014; 57: 762–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monnier L, Dohan A, Amara N, Zagdanski AM, Drame M, Soyer P, et al. Anoperineal disease in hidradenitis suppurativa: MR imaging distinction from perianal Crohn’s disease. Eur Radiol 2017; 27: 4100–4109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Virgilio E, Bocchetti T, Balducci G. Utility of MRI in the diagnosis and post-treatment evaluation of anogenital hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg 2015; 41: 865–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Derruau S, Renard Y, Pron H, Taiar R, Abdi E, Polidori G, et al. Combining magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and medical infrared thermography (MIT) in the pre- and peri-operating management of severe hidradenitis suppurativa (HS). Photodiagnosis Photodyn Ther 2018; 23: 9–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jerrold T. Bushberg, John M. Boone. The essential physics of medical imaging. Philadelphia, USA. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Axel L, Hayes C. Surface coil magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Int Physiol Biochim 1985; 93: 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oranges T, Vitali S, Benincasa B, Izzetti R, Lencioni R, Caramella D, et al. Advanced evaluation of hidradenitis suppurativa with ultra-high frequency ultrasound: a promising tool for the diagnosis and monitoring of disease progression. Skin Res Technol 2020; 26: 513–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Álvarez P, García-Martínez FJ, Poveda I, Pascual JC. Intralesional triamcinolone for fistulous tracts in hidradenitis suppurativa: an uncontrolled prospective trial with clinical and ultrasonographic follow-up. Dermatology 2020; 236: 46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nazzaro G, Moltrasio C, Marzano AV. Infrared thermography and color Doppler: Two combined tools for assessing inflammation in hidradenitis suppurativa. Skin Res Technol 2020; 26: 140–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]