Abstract

Purpose:

A T1 sequence on routine baseline staging rectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is thought to help detect bone lesions. Our primary aim was to evaluate the incidence of bone lesions encountered on baseline staging rectal MRI, particularly the prevalence of bone metastases.

Methods:

This retrospective study included patients with rectal adenocarcinoma who underwent baseline rectal MRI at our institution between January 2010 and December 2017. The MRI report was reviewed for presence of bone lesions. When found, lesion type, presence of axial T1 non-fat-suppressed sequence, primary tumor T-stage, and presence of other organ metastases were recorded. In the absence of bone biopsy, the reference standard was follow-up imaging via computed tomography (CT), MRI, and/or positron emission tomography/CT (PET/CT) ≥ 1 year after the baseline MRI. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test were used to compare clinicopathologic data of patients with malignant or benign bone lesions.

Results:

A total of 1,197 patients were included. 62/1197 patients (mean age 56.8 years (SD: 13.8), with 39 men) had bone lesions on baseline imaging, with 6 being bone metastases (0.5%, 95% CI: 0.2%–1.1%). Of the 6 patients with bone metastases, 5/6 had other metastases (i.e. liver, lung) at baseline.

Conclusion:

Bone metastases on baseline rectal MRI performed for rectal adenocarcinoma are extremely rare. Furthermore, bone metastases without other organ (i.e. liver, lung) involvement is extremely rare.

Keywords: Rectal neoplasm, bone neoplasm, magnetic resonance imaging

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most common cancer in men and women in the United States [1-3]. While the prognosis of rectal cancer has improved in the recent decades – from increased screening, standardized high quality pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for staging [4-7], and targeted therapy – the metastatic form of rectal cancer still has a poor prognosis where the five-year survival rate is only 15.8% [8]. Rectal cancer metastasizes to the liver and lungs more frequently than to the bone or other organs [9-11]. When bone metastases arise from rectal cancer, their presence is uncommon at initial diagnosis of rectal cancer, occurring between 1% and 5.5% of patients [12,13]; in addition, it very rarely occurs without liver or lung metastases [9,14,15,13].

There is a lack of agreement between guidelines established by European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) and Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) panels on whether to acquire a T1 sequence with rectal MRI performed for the clinical staging of rectal cancer [6,7]. The SAR panel reached consensus (greater than 70% agreement) that patients should be scanned with an unenhanced T1 sequence for the detection of bone lesions and mucinous tumor extent [6]. However, the ESGAR panel recommended against routine T1-weighted (fat suppressed non-enhanced and contrast-enhanced) sequences because obtaining an axial T1 sequence may be superfluous on routine baseline staging rectal MRI given the low prevalence of bone metastases in rectal cancer.

Our primary aim was to evaluate the incidence of bone lesions encountered on baseline staging rectal MRI, particularly the prevalence of bone metastases.

Materials and Methods

Patient selection

Approval for this retrospective study was obtained from our institutional review board and the requirement for written informed consent was waived. This study was conducted in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

An institutional electronic database (DataLine) was searched to identify consecutive patients who underwent their first dedicated rectal MRI exam between January 1, 2010, and December 31, 2017. One oncologic imaging fellow with 3 years of experience in rectal MRI (**) reviewed the indication for the exam and excluded patients undergoing MRI performed for reasons other than baseline rectal cancer staging or who had a history of an additional primary cancer. Of the 2,690 rectal MRI examinations performed at our institution during the study timeframe, 1,197 patients met the inclusion criteria for newly-diagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma undergoing baseline staging rectal MRI (Figure 1).

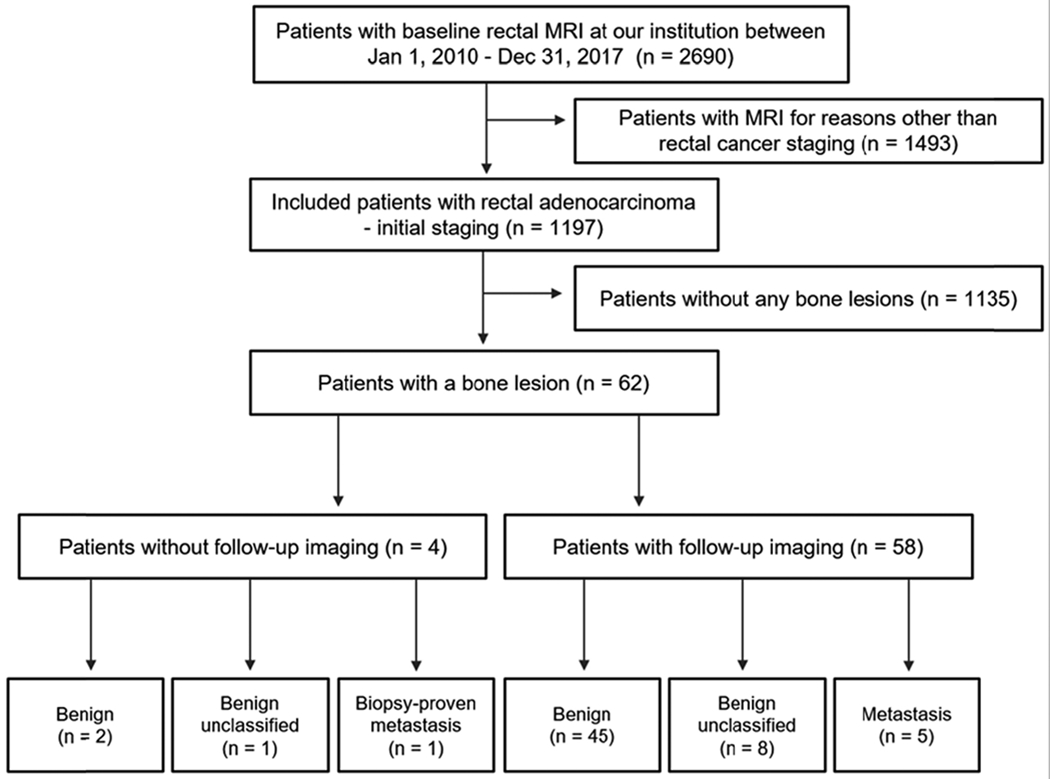

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of patient inclusion

MRI protocol

Images were acquired at our institution with a 1.5 Tesla or 3 Tesla MRI scanner (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee, WI) between 2010 and 2017 with standard pelvic MRI and dedicated sequences to evaluate the rectum with field of view from L5 to the anal verge (Table 1). A body coil was used for excitation, and a multi-channel phased-array coil (without endorectal coil) was used for signal reception. During the study period, the MRI parameters varied slightly as per the standard departmental protocol, as scans before August 24, 2013, included an axial T1-weighted non-fat suppressed sequence; 70% (803/1197) of scans, however, were obtained after this date.

Table 1.

MRI protocol

| Seq | TR/TE (ms) | Matrix | FOV (mm) | ST/S (mm) | BW (kHz)/ FA | b Value (s/mm2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Axial T2-weighted imaging | |||||||

| 1.5T | FSE | 4000–6000/110 | 320×224 | 200–240 | 5/1 | 32/90 | - |

| 3.0T | 4000–6000/110 | 320×224 | 200–240 | 5/1 | 32/90 | - | |

| Oblique Axial T2-weighted imaging | |||||||

| 1.5T | FSE | 4000–6000/120 | 320×224 | 180 | 3/1 | 32/90 | - |

| 3.0T | 4000–6000/120 | 320×224 | 180 | 3/1 | 32/90 | - | |

| DWI | |||||||

| 1.5T | DWI | 6000/minimum | 128×128 | 240 | 5/1 | - | 0,800 |

| 3.0T | 6000/minimum | 128×128 | 240 | 5/1 | - | 0,800,1500 | |

BW, bandwidth; DWI, diffusion-weighted imaging; FA, fractional anisotropy; FOV, field-of-view; FSE, fast spin echo; ST/S, slice thickness per slice; TE, echo time; TR, repetition time

Data collection

The MRI reports were reviewed by an oncologic imaging fellow with 3 years of experience in rectal MRI (**) for verbiage indicating the presence or absence of metastatic disease, no suspicious bone lesions, presence of a benign bony lesion, findings indeterminate for bone metastases, or one or more bone metastases. When a bone lesion was found, the following characteristics were recorded: number of bony lesions, maximum lesion diameter, lesion type as reviewed by a musculoskeletal-trained radiologist (**) with 15 years of experience, whether the exam includes an axial T1 non-fat suppressed sequence, rectal primary tumor T stage by imaging, and whether the patient had metastases to other organs at baseline (e.g., liver, lung).

For each patient whose baseline MRI report mentioned at least one bony lesion, the electronic medical record was searched for the patient’s age at time of imaging, type of rectal cancer (adenocarcinoma versus non-adenocarcinoma, as determined by pathologic examination), baseline carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and alkaline phosphatase, and whether the patient underwent bone biopsy. Additional data recorded included the date of the baseline MRI examination, number of follow-up MRI examinations, computed tomography (CT), or positron emission tomography-CT (PET-CT) scans, and the date and modality of the last available follow-up examination.

Reference standard

Histopathologic bone biopsy, when performed, was considered the reference standard. However, in the absence of bone biopsy, bone metastases were confirmed by any typical imaging findings on available CT, PET-CT, or MRI, such as hypointense signal relative to skeletal muscle on non-fat suppressed T1-weighted imaging or T2-weighted imaging, hyperintense rim on fat-suppressed T2 (halo sign), cortical destruction, pathologic fracture, extraosseous soft tissue component, or increase in size on follow-up [16-19]. These imaging characteristics were considered in combination with at least 1-year follow-up imaging showing features such as an increase in size or development of overt malignant features (evident bone destruction, pathologic fracture, development of soft tissue component), or FDG-avidity on PET/CT. Indeterminate bone lesions which could not be classified owing to their non-specific appearance were considered unlikely to represent bone metastases if there was no growth after one year from baseline and they demonstrated intralesional fat representative of focal red marrow based on T1-weighted imaging without fat suppression or T2-weighted imaging with fat suppression [20]. If follow-up imaging was not performed on an indeterminate lesion, assessment of malignant potential was based on contemporaneous imaging or the treating clinician’s clinical assessment.

Statistical analysis

95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by biostatisticians (**, **) to help extrapolate the results from this study sample. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test and Fisher’s exact test were used to summarize and compare associations of patient characteristics and laboratory values between patients presenting with malignant or benign bone lesions at baseline staging. All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 62/1197 patients who met the inclusion criteria (mean age 56.8 years (SD: 13.8), with 39 men and 23 women) were included in the analysis. Figure 1 shows the patient inclusion flowchart. Reasons for exclusion included MRI acquired for reasons other than rectal cancer staging (n = 1493) and patients without any bone lesions (n = 1135). Table 2 details the clinicopathologic variables of the 62 patients who were included in the study. A total of 62/1197 (5.2%) patients had bone lesions, of which 6 (0.5%) of these were determined to be bone metastases. Of the 6 bone metastases, only one was biopsy-proven whereas the remaining five were diagnosed based on imaging features generally interpreted as indicative of bone metastasis as previously described.

Table 2.

Clinicopathologic features of patients at the time of the baseline scan, stratified by benign versus malignant bone lesion

| Benign (n = 56) | Metastasis (n = 6) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | 55 (28–85) | 56 (36–73) | 0.8 |

| CEA1 (ng/mL) | 5 (0–86) | 10 (2–1702) | 0.14 |

| ALK2 (IU/L) | 74 (43, 151) | 96 (73, 103) | 0.12 |

| Distant metastasis (%) | 5/56 (8.9) | 5/6 (83) | < 0.001 |

| T stage (%) | |||

| 0 | 3/56 (5.4) | 1/6 (17) | - |

| 1, 2 | 6/56 (11) | 0/6 (0) | - |

| 3 | 36/56 (64) | 1/6 (17) | - |

| 4 | 11/56 (20) | 4/6 (67) | - |

Baseline CEA not available for 8 benign lesions and 1 metastasis.

Baseline ALK not available for 10 benign lesions and 1 metastasis.

CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ALK, alkaline phosphatase.

Spectrum of bone abnormalities detected on primary staging rectal MRI

A total of 47/62 (75.8%) bone lesions were characterized as classic benign bone lesions (Table 3), such as bone islands (Figure 2), sacral insufficiency fractures (Figure 3), or hemangiomas. While 9/62 (14.5%) lesions could not be classified owing to a non-specific appearance, upon additional review, they were categorized as benign unclassified lesions based on imaging and follow-up. Only one benign unclassified lesion did not have any follow-up imaging or an accompanying clinical assessment or treatment plan available; however, this lesion had evidence of benign imaging features on a contemporaneous CT (vacuum effect and abutment of the sacroiliac joint). The remaining 6/62 (9.8%) lesions represented bone metastases.

Table 3.

Spectrum of bone lesions

| Bone lesion (n = 62) | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Bone island | 14 (23%) |

| Benign unclassified | 9 (15%) |

| Hemangioma | 8 (13%) |

| Degenerative changes | 7 (11%) |

| Island of red marrow | 6 (9.7%) |

| Metastasis | 6 (9.7%) |

| Enchondroma | 3 (4.8%) |

| Benign fibro-osseous lesion | 2 (3.2%) |

| Intraosseous lipoma | 2 (3.2%) |

| Sacral insufficiency fracture | 2 (3.2%) |

| Femoral head avascular necrosis | 1 (1.6%) |

| Liposclerosing myxofibrous tumor | 1 (1.6%) |

| Synovial herniation pit | 1 (1.6%) |

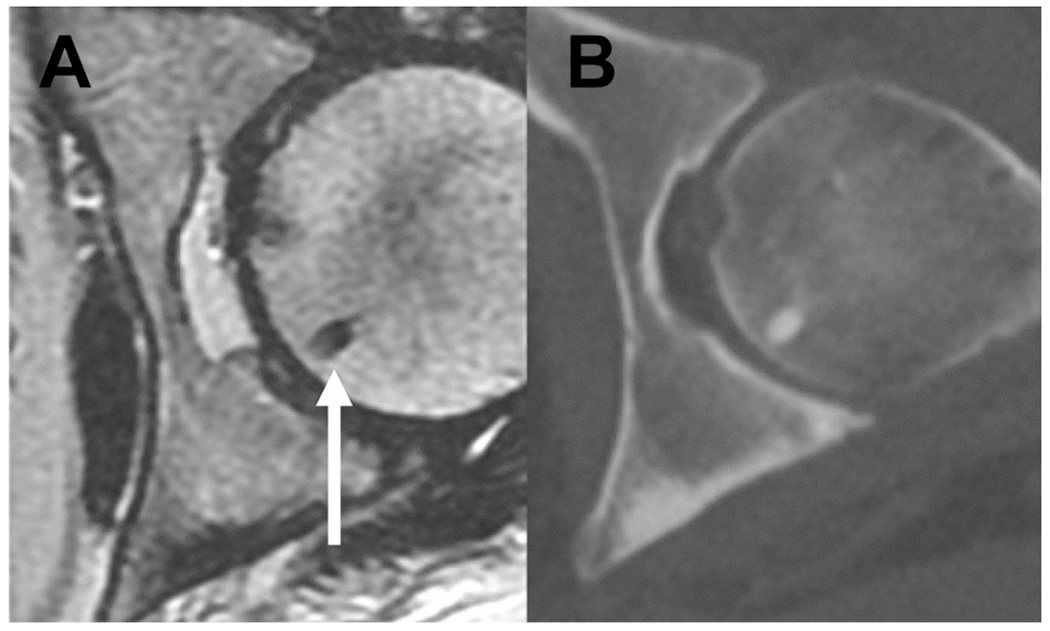

Fig. 2.

Benign bone lesion at baseline in a 50-year-old woman presenting with newly diagnosed rectal cancer. Bone island in the left femoral head (arrow) on (A) axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and (B) corresponding CT image from staging CT CAP. A bone island is a small focus of dense (cortical) bone within the medullary space and hence is of very low signal in all MRI sequences including axial T2 MRI

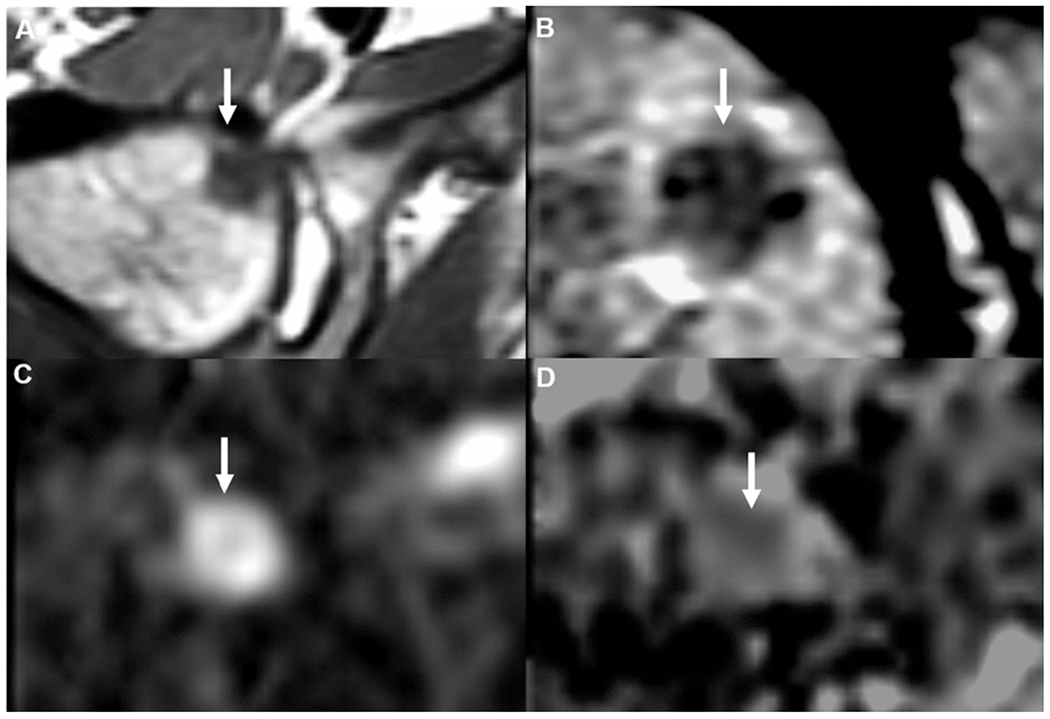

Fig. 3.

Right femoral head metastasis in a 52-year-old man with newly diagnosed rectal cancer. (A) Hypointense lesion on non-contrast axial T1 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with corresponding intermediate signal on axial T2 (B), restricted diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI), (D) and low apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) signal.

Prevalence of bone metastases on primary staging rectal MRI

Only 29.5% (353/1197) of patients had a rectal MRI with an acquisition protocol employing an axial T1 non-fat suppressed sequence. Only 1/1197 patients was diagnosed with a metastatic bone lesion using this T1-weighted sequence (Figure 3). Five of six patients with bone metastases were diagnosed without a T1 non-fat suppressed sequence.

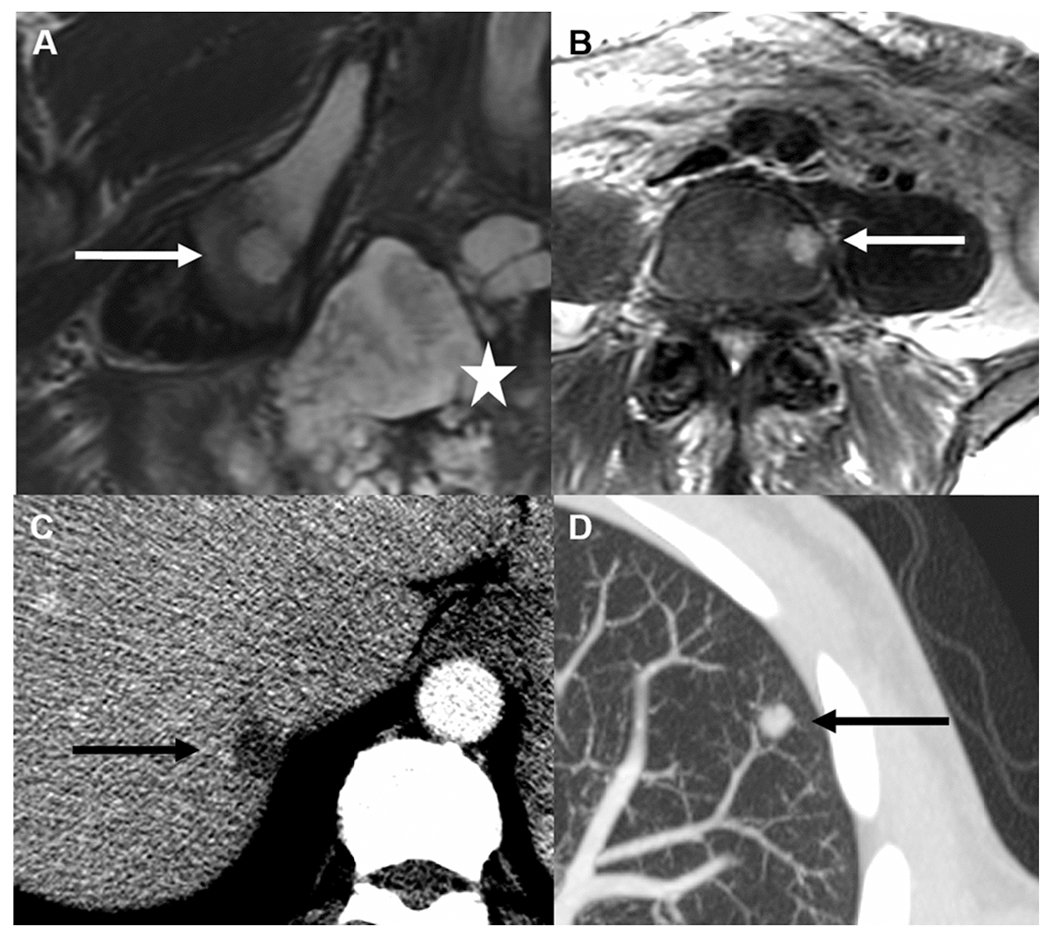

Distant metastases were found at baseline in 5/6 patients with bone metastases (Figures 4 and 5). Three patients had liver metastases, two had lung metastases, and one had pelvic adenopathy. Only 1/1197 patients had bone metastasis without other visceral metastases (Figure 6).

Fig. 4.

58-year-old man with mucinous rectal tumor seen on Axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (A, star) with right ilium metastasis (A, arrow) in addition to L4 vertebral body metastasis (B, arrow). Axial images from baseline contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) show liver (C, arrow) and lung (D, arrow) metastases.

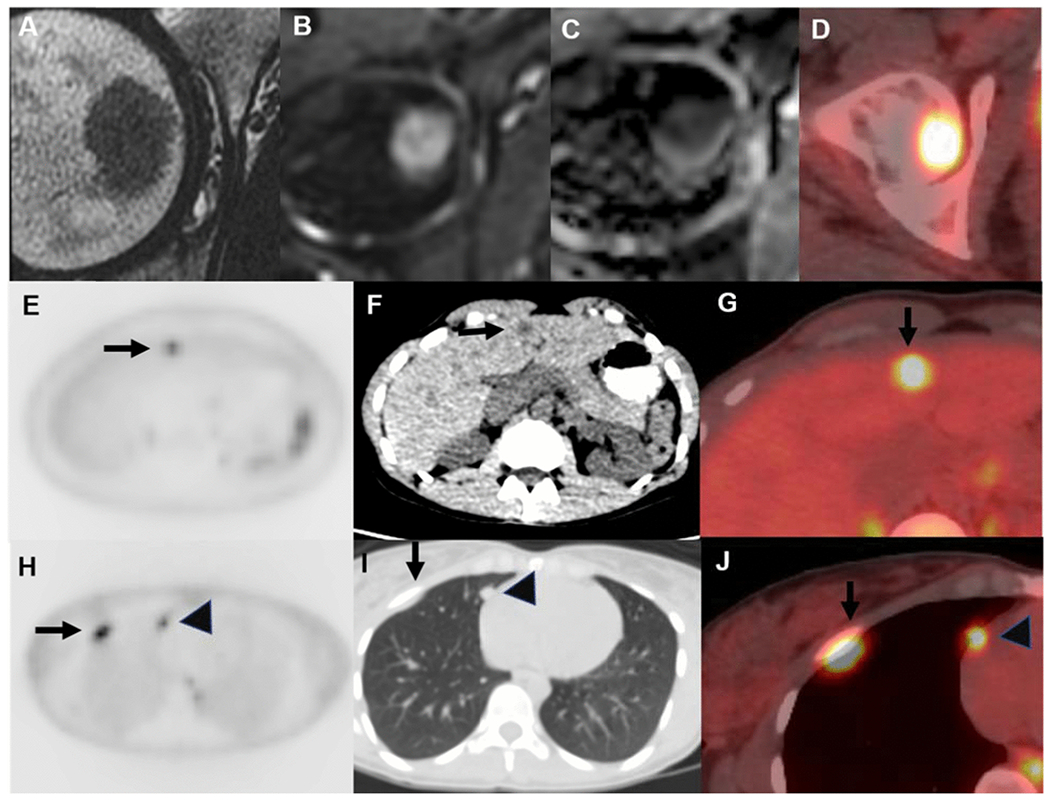

Fig. 5.

Femoral head metastasis in a 35-year-old woman with newly diagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma. Metastasis is hypointense on axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (A), restricts diffusion on diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) (B), and demonstrates low signal on apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) (C), with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity on positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) (D). Other organ metastases were present at PET-CT; for example, maximum intensity projection (MIP), non-contrast CT, and fused axial images show liver (E–G, arrow), lung (H–J, arrow), and pleural (H–J, arrowhead) metastases.

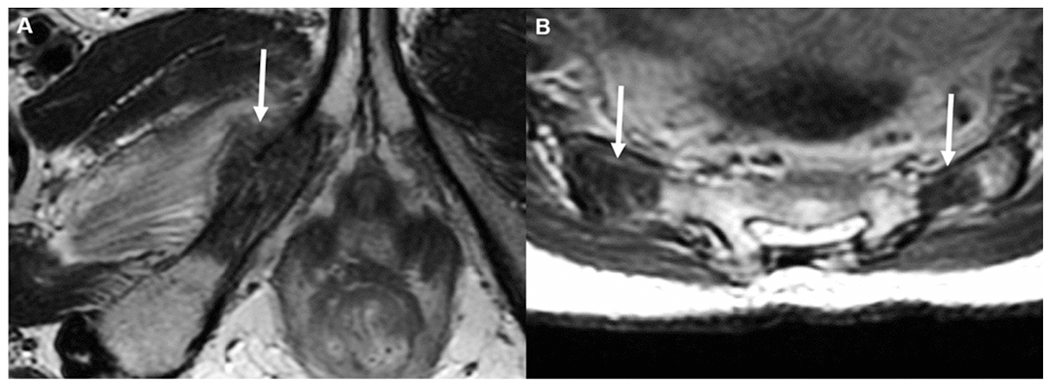

Fig. 6.

In this study, the only patient who had bone metastasis (right inferior pubic ramus metastasis) without other visceral metastasis was a 46-year-old woman with newly diagnosed T3 rectal cancer. (A) Markedly hypointense lesion on axial T2 magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), with associated pathologic fracture and small extraosseous component (arrow). Also, there were bilateral sacral metastases (B, arrows) on axial T2 MRI.

Discussion

A T1 sequence on routine baseline staging rectal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is thought to help detect bone lesions. Therefore, we conducted a large retrospective study with 1,197 patients who underwent rectal MRI for initial staging at our institution to evaluate the prevalence of bone metastases with a secondary aim to determine the spectrum of bone abnormalities and assess the need for sequences sensitive to significant bone lesions. We found that the prevalence of bone metastases (6/1197) as well as the prevalence of metastases only to bone without other visceral metastases (1/1197) were both extremely rare. Our data suggest that the addition of bone sensitive sequences may play no significant role in rectal cancer staging.

Our findings are concordant with the previously published literature that bone metastases from rectal cancer are exceedingly rare [12,13,15]. Thus, given the low prevalence of bone metastases, our findings suggest that an unenhanced T1-weighted MRI sequence would not be helpful over the T2 sequence as part of the standard rectal MRI acquisition protocol. A standard imaging acquisition protocol for rectal MRI is different from a dedicated musculoskeletal MRI. The minimum acquisition protocols for bone lesion characterization on MRI typically use a small field-of-view focused on the lesion, include some form of fat suppression, and include the lesion on all sequences performed [21]. State-of-the-art rectal MRI, on the other hand, includes T2-weighted images including small field-of-view axial obliques through the primary tumor, combined with diffusion-weighted images. Large field-of-view T2-weighted images of the entire pelvis are acquired from the aortic bifurcation to the perineum, which is primarily used for the evaluation of lymph nodes and bone lesions [6]. While bone lesions in rectal MRI are often only covered in the large field-of-view T2 images and not in other sequences, our findings nevertheless favor omitting the T1 sequence. In our analysis, a T2 sequence was found to be sensitive for detecting bone metastases and while a T1 is most helpful in determining whether the lesion seen on a T2 sequence is concerning or not, other imaging, such as CT and PET-CT can help shed light on the etiology of the T2 lesion. This is in contrast to the published SAR Rectal and Anal Disease Focused Panel guidelines [6] which recommends acquiring a routine T1 sequence for the purpose of detecting bone metastases; however, the extra sequence has the potential to unnecessarily prolong exam time and may impact patient comfort with low yield for bone metastases. Furthermore, while the T1 sequence has a relatively short acquisition time, MR scanner time is always a scarce resource, and the time savings over multiple studies may provide an opportunity to switch to higher resolution for improved diagnostic confidence or add advances sequences while maintaining an efficient workflow.

As to the prevalence of only bone metastases without any distant metastases to other organs, we note that there have been a few case reports in the literature of solitary bone metastases in rectal adenocarcinoma [22-24]. However, consistent with previously reported epidemiologic data [13], our findings indicate that such metastases only to bone without other organ involvement is exceedingly rare. Thus, acquiring a T1 sequence at baseline rectal MRI for the sole purpose of identifying bone metastases would provide no incremental value, given that CT of the chest and abdomen are also recommended for baseline staging of T3 or T4 tumors (vs T1 and T2 tumors which are at lower risk for distant metastases) [8,25].

Thus, our findings are in line with ESGAR consensus but in contrast to SAR recommendations [6,7]. While a T1-weighted sequence may be helpful in other clinical scenarios such as mucinous rectal cancer [6,26], our study indicates it has a low yield for detection of bone metastases. Furthermore, while one patient was diagnosed with a metastatic bone lesion using a T1-weighted sequence, this could have also been diagnosed with a T2 sequence.

Our study has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective, single-institution study with the associated limitations of such a study design, including selection bias and uncertain generalizability to other practice settings. As a single-center retrospective analysis, our sample size is small and our results need further validation in a prospective multicenter study to compare the detection of bone metastases using protocols with and without a T1 sequence. However, it is unlikely to change the overall conclusion. Another limitation is that this study was not designed to assess the ability of MRI to detect or characterize bone lesions. Instead, it was performed to assess the prevalence and spectrum of bone lesions in a large sample of patients with rectal cancer at a large, dedicated oncology center. Third, we had no histopathology to prove the benignity of most of the bone lesions detected on MRI. Although an ideal study would include pathologic evaluation of all imaging-detected lesions, this is not in accordance with standard clinical practice. Bone lesions are only biopsied if there is sufficient clinical concern for metastatic disease and the imaging findings are indeterminate or if there is a need for tissue confirmation of diagnosis. Lastly, as with all imaging findings, inter- and intra-observer variability will exist in the detection and reporting of these bone lesions at MRI, and so more benign bone lesions may have been present but omitted in reporting; this study was not designed to assess that variability. Our working assumption, however, is that any bone lesion present at the time of staging rectal MRI, which after ≥ 1 year of follow-up did not manifest as evident metastatic disease, was highly unlikely to represent metastasis.

In conclusion, bone lesions are uncommon in patients undergoing baseline MRI staging of rectal adenocarcinoma. In our study population they very rarely represent metastatic disease in the overall population. While recognizing that accurate preoperative staging is essential, the rarity of bone metastases in rectal cancer without other organ metastases suggests that acquiring an additional T1-weighted sequence at baseline for purposes of detecting bone metastases may play no significant role in rectal cancer staging. Simplifying MRI protocols by omitting the extra unenhanced T1-weighted sequence could lead to decreased scanning time and increased efficiency.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Joanne Chin, MFA, ELS, for editorial support and Natalie Gangai for assistance on this article.

Funding:

This research was funded in part by the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee institutional review board at Memorial Sloan Kettering cancer Center and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Consent to participate: For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data and material:

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1.Meyer JE, Narang T, Schnoll-Sussman FH, Pochapin MB, Christos PJ, Sherr DL (2010) Increasing incidence of rectal cancer in patients aged younger than 40 years: an analysis of the surveillance, epidemiology, and end results database. Cancer 116 (18):4354–4359. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68 (6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferlay J, Parkin DM, Steliarova-Foucher E (2010) Estimates of cancer incidence and mortality in Europe in 2008. Eur J Cancer 46 (4):765–781. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sahni VA, Silveira PC, Sainani NI, Khorasani R (2015) Impact of a Structured Report Template on the Quality of MRI Reports for Rectal Cancer Staging. AJR Am J Roentgenol 205 (3):584–588. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.14053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norenberg D, Sommer WH, Thasler W, D’Haese J, Rentsch M, Kolben T, Schreyer A, Rist C, Reiser M, Armbruster M (2017) Structured Reporting of Rectal Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Suspected Primary Rectal Cancer: Potential Benefits for Surgical Planning and Interdisciplinary Communication. Invest Radiol 52 (4):232–239. doi: 10.1097/RLI.0000000000000336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gollub MJ, Arya S, Beets-Tan RG, dePrisco G, Gonen M, Jhaveri K, Kassam Z, Kaur H, Kim D, Knezevic A, Korngold E, Lall C, Lalwani N, Blair Macdonald D, Moreno C, Nougaret S, Pickhardt P, Sheedy S, Harisinghani M (2018) Use of magnetic resonance imaging in rectal cancer patients: Society of Abdominal Radiology (SAR) rectal cancer disease-focused panel (DFP) recommendations 2017. Abdom Radiol (NY) 43 (11):2893–2902. doi: 10.1007/s00261-018-1642-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beets-Tan RGH, Lambregts DMJ, Maas M, Bipat S, Barbaro B, Curvo-Semedo L, Fenlon HM, Gollub MJ, Gourtsoyianni S, Halligan S, Hoeffel C, Kim SH, Laghi A, Maier A, Rafaelsen SR, Stoker J, Taylor SA, Torkzad MR, Blomqvist L (2018) Magnetic resonance imaging for clinical management of rectal cancer: Updated recommendations from the 2016 European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ESGAR) consensus meeting. Eur Radiol 28 (4):1465–1475. doi: 10.1007/s00330-017-5026-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.NCCN Guidelines for Patients®: Rectal Cancer (2018) National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Rectal Cancer (Version 2.2018).https://www.nccn.org/patients/guidelines/content/PDF/rectal-patient.pdf. Accessed April 11 2020

- 9.Disibio G, French SW (2008) Metastatic patterns of cancers: results from a large autopsy study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 132 (6):931–939. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165(2008)132[931:MPOCRF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hess KR, Varadhachary GR, Taylor SH, Wei W, Raber MN, Lenzi R, Abbruzzese JL (2006) Metastatic patterns in adenocarcinoma. Cancer 106 (7):1624–1633. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss L, Grundmann E, Torhorst J, Hartveit F, Moberg I, Eder M, Fenoglio-Preiser CM, Napier J, Horne CH, Lopez MJ, et al. (1986) Haematogenous metastatic patterns in colonic carcinoma: an analysis of 1541 necropsies. J Pathol 150 (3):195–203. doi: 10.1002/path.1711500308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baek SJ, Hur H, Min BS, Baik SH, Lee KY, Kim NK (2016) The Characteristics of Bone Metastasis in Patients with Colorectal Cancer: A Long-Term Report from a Single Institution. World J Surg 40 (4):982–986. doi: 10.1007/s00268-015-3296-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth ES, Fetzer DT, Barron BJ, Joseph UA, Gayed IW, Wan DQ (2009) Does colon cancer ever metastasize to bone first? a temporal analysis of colorectal cancer progression. BMC Cancer 9:274. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-274 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katoh M, Unakami M, Hara M, Fukuchi S (1995) Bone metastasis from colorectal cancer in autopsy cases. J Gastroenterol 30 (5):615–618. doi: 10.1007/BF02367787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kanthan R, Loewy J, Kanthan SC (1999) Skeletal metastases in colorectal carcinomas: a Saskatchewan profile. Dis Colon Rectum 42 (12):1592–1597. doi: 10.1007/BF02236213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hwang S, Panicek DM (2007) Magnetic resonance imaging of bone marrow in oncology, Part 1. Skeletal Radiol 36 (10):913–920. doi: 10.1007/s00256-007-0309-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bernard S, Walker E, Raghavan M (2017) An Approach to the Evaluation of Incidentally Identified Bone Lesions Encountered on Imaging Studies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 208 (5):960–970. doi: 10.2214/AJR.16.17434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schweitzer ME LC, Mitchell DG, Gannon FH, Gomella LG. (1993) Bull’s-eyes and halos: useful MR discriminators of osseous metastases. Radiology 188:249–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghazizadeh S, Foss EW, Didier R, Fung A, Panicek DM, Coakley FV (2014) Musculoskeletal pitfalls and pseudotumours in the pelvis: a pictorial review for body imagers. Br J Radiol 87 (1042):20140243. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20140243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simpfendorfer CS, Ilaslan H, Davies AM, James SL, Obuchowski NA, Sundaram M (2008) Does the presence of focal normal marrow fat signal within a tumor on MRI exclude malignancy? An analysis of 184 histologically proven tumors of the pelvic and appendicular skeleton. Skeletal Radiol 37 (9):797–804. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0523-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nascimento D, Suchard G, Hatem M, de Abreu A (2014) The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of bone tumours and tumour-like lesions. Insights Imaging 5 (4):419–440. doi: 10.1007/sl3244-014-0339-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bangera S, Dunkow P, Weerasinghe S, Murugesan SV (2016) An unusual pain in the hip. Oxf Med Case Reports 2016 (9):omw072. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omw072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Udare A, Sable N, Kumar R, Thakur M, Juvekar S (2015) Solitary osseous metastasis of rectal carcinoma masquerading as osteogenic sarcoma on post-chemotherapy imaging: a case report. Korean J Radiol 16 (1):175–179. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2015.16.1.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chalkidou AS, Boutis AL, Padelis P (2009) Management of a Solitary Bone Metastasis to the Tibia from Colorectal Cancer. Case Rep Gastroenterol 3 (3):354–359. doi: 10.1159/000239626 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal I, Fowler KJ, Kaur H, Cash BD, Feig BW, Gage KL, Garcia EM, Hara AK, Herman JM, Kim DH, Lambert DL, Levy AD, Peterson CM, Scheirey CD, Small W, Smith MP Jr., Lalani T, Carucci LR (2017) ACR Appropriateness Criteria((R)) Pretreatment Staging of Colorectal Cancer. J Am Coll Radiol 14 (5S):S234–S244. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2017.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horvat N, Hope TA, Pickhardt PJ, Petkovska I (2019) Mucinous rectal cancer: concepts and imaging challenges. Abdom Radiol (NY) 44 (11):3569–3580. doi: 10.1007/s00261-019-02019-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.