Abstract

Objectives

Our objective was to evaluate the impact of a service delivery model led by membership-based associations called Iddirs formed by women on tuberculosis preventive treatment (TPT) initiation and completion rates among children.

Design

Comparative, before-and-after study design.

Setting

Three intervention and two control districts in Ethiopia.

Participants

Children who had a history of close contact with adults with infectious forms of tuberculosis (TB). Child contacts in whom active TB and contraindications to TPT regimens were excluded were considered eligible for TPT.

Interventions

Between July 2020 and June 2021, trained women Iddir members visited households of index TB patients, screened child household contacts for TB, provided education and information on the benefits of TPT, linked them to the nearby health centre and followed them at home for TPT adherence and side effects. Two control zones received the standard of care, which comprised of facility-based provision of TPT to children. We analysed quarterly TPT data for treatment initiation and completion and compared intervention and control zones before and after the interventions and tested for statistical significance using Poisson regression.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

There were two primary outcome measures: proportion of eligible children initiated TPT and proportion completed treatment out of those eligible.

Results

TPT initiation rate among eligible under-15-year-old children (U15C) increased from 28.7% to 63.5% in the intervention zones, while it increased from 34.6% to 43.2% in the control zones, and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.001). TPT initiation rate for U5C increased from 13% (17 out of 131) to 93% (937 out of 1010). Of the U5C initiated, 99% completed treatment; two discontinued due to side effects; three parents refused to continue; and one child was lost to follow-up.

Conclusion

Women-led Iddirs contributed to significant increase in TPT initiation and completion rates. The model of TPT delivery should be scaled-up.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, PUBLIC HEALTH, Community child health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We used a double-difference analysis approach substantiated with statistical tests to ascertain the impact of the interventions.

Data on the full cascade of care including treatment outcome data were available for all under-5-year-old children included in this study.

We provide the first report on the beneficial role that engaging Iddirs, locally established community support groups, can have in tuberculosis care in Ethiopia.

Before–after study designs have inherent limitations such as failure to control for other confounding factors.

The intervention had several inter-related components making it impossible to attribute impact to the involvement of Iddirs alone.

Introduction

Of the 1.7 billion people estimated to be infected with tuberculosis (TB) worldwide in 2019, about 80% reside in South-East Asian, Pacific and African regions.1 If the goal of ending TB by 2030 is to be met,2 management of TB infection and preventing TB disease should be intensified along with strengthened efforts to diagnose and treat active disease.3 Reviews of recent progress, however, show a significant lag in achieving globally agreed on targets. According to the progress report of the UN high-level meeting targets, only 21% (6.3 of 30 million) of TB preventive treatment (TPT) targets were met after 40% of the time has elapsed. Moreover, achievements varied considerably by population subgroups: <1% for household contacts older than 5 years, 20% for contacts under-5-year-old children (U5C) and 88% for people living with HIV (PLHIV) making efforts to treat the first two groups of critical importance.4

In Ethiopia, a high TB burden country missing about a third of estimated 151 000 people who develop TB each year,5 treatment of TB infection among children has also been a major area of concern. The pathway of care for TPT in children usually begins with contact investigation of a household member with diagnosed TB. Young children are identified and screened for active disease. If active disease is ruled out, then TPT can be offered. Programmatic data show variable TPT initiation rates ranging from 13% to 64.3%,6 and treatment completion rates have been either low or unknown, with some sites reporting as low as 12%.7 Nevertheless, Ethiopia is among a few African countries that have made significant progress in increasing TPT.6 8 High treatment completion rates were reported in districts that received additional technical assistance to the existing health extension programme.9 These results were achieved through additional technical and financial support, but sustainably replicating these best practices requires further work.9 10

Of several factors that contribute to the low uptake of TPT in the household contact groups, cost of travel to health facilities; perceived lack of need for TPT in children among parents; low level of knowledge among healthcare workers; stigma; other competing priorities of the family; and medication related challenges such as pill burden stand out as common barriers.11 12 Other factors include fear of side effects,7 lack of supplies and poor recording and reporting practices.13 Common themes with the barriers include access and information, which may be better addressed with community-based interventions.

There are successful examples of community-based interventions that helped improve childhood TB services. In Nepal, for example, intensified community-based case-finding strategies led to improvements in childhood TB case-finding.14 Similarly, in Uganda, strategies that included decentralised delivery of TB services through community health workers contributed to 85% TPT completion rates.15 In a prospective study in Peru where community-based accompaniment team of trained community health workers and nurse technicians were involved in a comprehensive psychosocial support that included home visits and direct treatment observation, 61 contacts including 35 aged 0–19 years received TPT prescriptions. Of those prescribed TPT, 57 received treatment of whom 51 completed the treatment.16

While Ethiopia demonstrated impressive results in TPT uptake and TB case detection by engaging paid community health workers,9 10 17 the contribution of volunteer women organised through the government system has been inconsistent.18 An often-overlooked local support system is the role of indigenous associations such as Iddirs in TB control in Ethiopia. Iddirs are membership-based local associations of people who have voluntarily entered an agreement to help each other during times of adversities. According to Pankhurst and Mariam,19 Iddirs are one of the oldest social capital institutions, designed to help reduce poverty by creating a strong network and cooperation among the community and as risk sharing and coping mechanism during economic crises. They are indigenous voluntary associations, mostly unique to Ethiopia, established primarily to provide support in burial matters. Household membership is ensured through payment of monthly fixed contributions. The association raises money whenever death occurs in a household, the amount depending on the specific bylaws.

There are no data on the role of Iddirs in TB care, but their engagement in HIV care and other social services has been reported.19 20 Similarly, engaging saving groups has been beneficial for infant-feeding practices in Malawi.21 Studies on the role of Iddirs and similar groups in TB care are scarce. We share results from an innovative project that collaborated with Iddirs in Ethiopia. Since empowering women is associated with favourable child health outcomes, we selected women-only Iddirs as a strategy to empower women in decision-making for their children’s medical care.22 23 Our objective was to assess the outcomes of engaging women-only Iddirs in TPT uptake in U5C in selected districts in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study sites

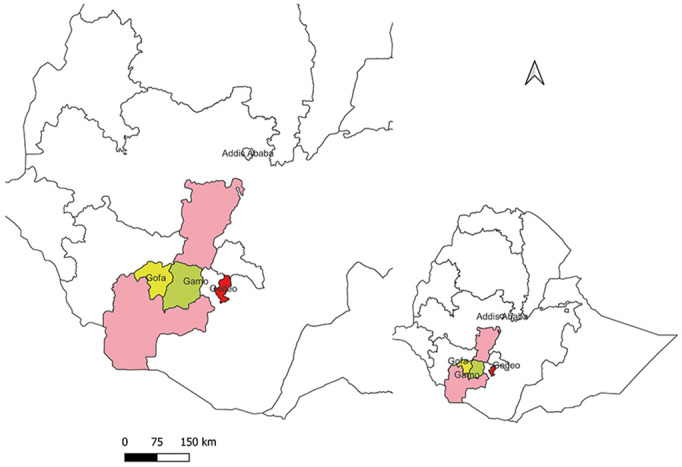

We conducted this study in two remote zones, Gamo and Goffa, in the Southern Nations’, Nationalities’ and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR) of Ethiopia and Addis Ketema subcity in the capital Addis Ababa. Figure 1 shows a map of intervention and control zones.

Figure 1.

Map of study sites.

The two zones were selected based on their low TPT coverage and lack of external partner support at the time of project initiation. Gamo and Goffa were under one zonal administration (Gamo Goffa zone) during the planning phase of this project, but they were split into two zones at the beginning of implementation. The two newly formed zones have a combined population of 2 202 751 (Gamo 1 544 756 and Goffa 658 005). Addis Ketema is a densely populated slum subcity with population of 343 228, and had 1 of the lowest TPT initiation rates in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital. Gedeo zone from SNNPR (population 1 138 814) and Yeka subcity (population 415 735) from Addis Ababa served as control zones and were purposefully selected based on their population size, geographic location (distinct and far away from the intervention zones) and similarity in baseline TPT initiation rates.

Study design

We used a before–after study design involving three intervention areas and two control areas as part of a TB REACH project following standardised methodology designed to measure TPT uptake in U5C in the selected project sites. As described below, the two control zones received the standard of care, while the intervention zones received the Iddir intervention.

Study period

Interventions were implemented between July 2020 and June 2021.

The standard of care

According to the national guidelines, TPT services are provided at the health centre or hospital level. Children are offered enrolment in TPT if they present at health facilities as a household contact of a person with TB and are found not to have active disease. Active search or contact investigation for eligible child contacts is rarely practiced at community level despite this being recommended to be part of the package for health extension workers (HEWs). Iddirs do not participate in contact investigation, TPT service facilitation, or other TB services. A 6-month course of isoniazid (INH) (6H) was the only nationally recommended IPT regimen for all eligible children during the designing phase of this project. Only U5C contacts and PLHIV were eligible for TPT until the guideline changed in July 2019 to include U15C. At the same time, the new national recommendations included two additional TPT regimens: a 3-month daily dose of INH and rifampicin (3HR) and weekly INH and rifapentine (3HP).

Interventions

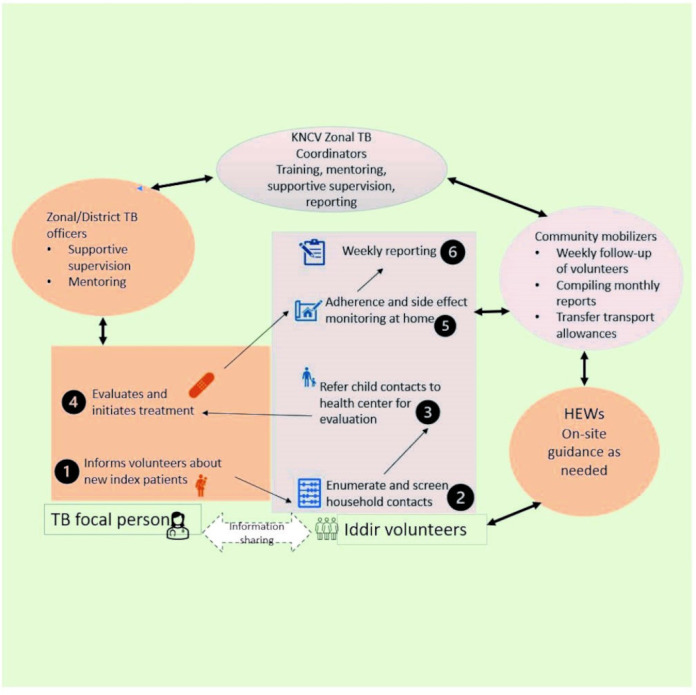

Figure 2 summarises the key interventions, which encompassed the following components and roles.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the core interventions and key players. HEWs, health extension workers; TB, tuberculosis.

Selection and capacity building of Iddir members and focal persons

We first mapped, selected and conducted capacity building of women-only Iddir members and focal persons from each selected district. Iddir leaders then nominated two focal persons from each Iddir to liaise with the project. During the selection of the Iddir focal persons and the additional Iddir members, the following criteria were used: previous engagement in volunteer services in the community, ability to read and write, possession of a mobile phone and good communication skills. The selected Iddir focal persons and members received training on the basics of TB with a focus on under-5-year-old child contact management and TPT. The training curriculum was customised from the integrated refresher training (IRT) material used for training HEWs. The IRT is a modular training material aimed at enhancing the knowledge and skills of HEWs in a wide range of disease prevention and health promotion topics where TB and HIV are included as one module. In addition to the basic training, they received training on COVID-19 preventive and personal protective equipment for use during home and health facility visits. The main trainer was an MSc level trained health officer from KNCV TB foundation together with two zonal project coordinators.

To ensure proper alignment of the project activities with the existing health system, we sensitised the district TB coordinators and TB focal persons about the project approaches and got their buy-in for implementation. This was organised as part of a 3-day event combined with a project kick-off meeting.

Active outreach for contact investigation and TPT

Each trained Iddir focal person selected three additional volunteers, to form a village steering group. The volunteer women conducted home visits to the households with known index pulmonary TB patients based on a list they obtained from the health facility TB focal person. During home visits, volunteers did symptom-based screening using a checklist, or verified if contacts were already screened for TB, with special focus on U5C. All under-5-year-old child contacts received a referral slip to the nearby health centre for further evaluation and TPT initiation. The volunteers then cross-checked clinic registers for linkage and initiation of all referred eligible children. The volunteers and clinic TB focal persons made frequent face to face and phone contacts to ensure no eligible child is left unattended. The district and zonal TB officers emphasised linkage and TPT initiation during their quarterly mentoring and supervision meetings. Community mobilisers (one per zone) who were nurses with additional orientation on the project activities provided additional technical guidance and administrative support to the volunteer women. By the end of each week, the volunteer women reported to the community mobilisers on the status of new enrolment and treatment completion rates. Figure 2 describes the core activities of the volunteers and other key contributors.

Once a child started TPT, community volunteers continued the follow-up by daily direct home visits, if the home was accessible and close to her home. Otherwise, visits were conducted one or two times per week. Additionally, in areas where mobile network was available, community volunteers sent daily text reminders and phone calls to the mothers/guardians to remind them about the daily dose intake. The volunteers used a checklist to monitor children’s adherence level and to document any side effects. The project provided airtime and transport costs for the volunteer women. Mothers/guardians of children who completed at least 95% of the recommended doses received a certificate of completion.

Strengthen data collection, monitoring and evaluation

Community mobilisers collected weekly progress reports from Iddir focal persons, and then aggregated the data and submitted to zonal project coordinators. The zonal project coordinators, after checking for data quality, submitted the report to the central project coordinator for quarterly compilation and reporting. Zonal project coordinators also visited intervention supported health facilities on a quarterly basis to provide onsite support. A key component of this quarterly onsite support included hands-on demonstration and feedback on the use of the nationally approved contact investigation and TPT registers. The intervention organised quarterly review meetings where planning, achievements and challenges were discussed.

Data sources and analysis

We used two data sources for the analysis. The first data source was the District Health Information System (DHIS-2) that compiles routine data for the national health system. Here, age disaggregation was limited to just two categories (<15 year and ≥15 year). Also, TPT completion data were not available. Since the DHIS-2 became fully operational only from July 2019, we limited our zonal comparative analysis to two time periods: July 2019–June 2020 as preintervention and July 2020–June 2021 as postintervention periods. The variables in the DHIS-2 database included number of U15C screened, eligible and initiated on TPT. We obtained the data through the Ministry of Health of Ethiopia, DHIS-2 platform. Since the DHIS-2 data were available both from control and intervention zones, we used these data to demonstrate impact using the difference-in-difference (DiD) approach.24

The second data source was a Microsoft Excel-based data collected by project teams from the intervention sites for U5C contacts. These data contained information extracted from facility registers since July 2018, then collected and updated prospectively on a monthly basis. The prospective data collection was done by Iddir women who maintained a logbook of every child identified and linked to the nearby health facility. At the end of every work week, they visited the health facility and checked the status of every child they referred. With support from the health facility TB focal person, they extracted the information from the health facility TPT register using a paper-based data abstraction form. They collected information about the number of children screened, eligible and initiated TPT, and reported to the community mobilisers on a weekly basis who in turn compiled the data in a monthly reporting format and submitted to a central coordinator. These data were not available for the control zones. As a result, data analysis from this source focused on trends in TPT improvement over three time periods: July 2018–June 2019 as pre intervention; July 2019–June 2020 as preparatory; and July 2020–2021 as post intervention.

The key variables collected and analysed included the standard cascade of contact investigation:

Eligible: screened children in whom active TB was excluded and contraindications for TPT ruled out.

Initiated: eligible children who started TPT.

Completed: successful completion was defined as 80% of the recommended doses taken within 120% of planned TPT duration, or 90% of recommended doses used within 133% of planned TPT duration according to the national guideline. The number of recommended doses were 12 for 3HP, 84 for 3HR and 168 for 6H. Completion status was ascertained by the community volunteers based on their weekly treatment follow-up records cross-checked with the clinic TPT register.

We calculated total numbers and proportion of eligible children initiated TPT; and number and proportion of initiated children who successfully completed treatment (for the U5C group only). Eligibility for TPT was based on the national guideline as described under the standard of care above.

We used Microsoft Excel to compile, analyse and describe quarterly TPT initiation data before and after the intervention. We presented the results in tables and displayed visually in graphs. In our DiD analysis, we used pictorial comparison of the directionality of change in key variables and calculated differences in numbers and percentages. To test for statistical significance, we performed Poisson regression analysis in SPSS V.25 using count data for eligible and initiated children as dependent variables, and Iddir interventions, region and pre–post periods as predictors.25 Statistical significance was set at p<0.05 and the results were presented as exponential beta values with 95% CI.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and other members of the public were not involved in the conception and design of the study. We will disseminate the summary of final study results translated into the local language to the local community through the district TB officers.

Results

Characteristics of Iddirs

We identified 67 women-only Iddirs in the 3 project zones, 42 in Gamo, 15 in Goffa and 10 in Addis Ketema. Seven of the ten Iddirs in Addis Ketema subcity were involved in childcare, five in wedding services and three in HIV care support. However, only 2 of the 42 Iddirs in Gamo and 2 of the 15 Iddirs in Goffa were involved in non-funeral activities at baseline. None of these Iddirs was involved in TB care at baseline.

Trends in the number of index TB patients notified

The number of all forms of TB notified declined both in the intervention and control zones. There was an 11.8% decline in the intervention zones, from 2021 at baseline to 1783 post intervention. The decline in the control zones was less dramatic (2.3%)—from 2589 at baseline to 2529 post intervention.

Improvements in the number of eligible U15C enrolled and initiated

The number of U15C contacts screened in intervention zones increased from 351 at baseline to 1620 during the intervention which was a 361% increase. In the control zones, the increase was just by 53.6%, from 567 to 871. Similarly, the number of eligible U15C enrolled in the intervention zones increased from 320 at baseline to 1550 post intervention (nearly fivefold increase). In the control zones, the increase in the number of eligible U15C enrolment was just by 52%. While the overall improvement in additional eligible patients enrolled was dramatic (964 overall difference), the improvement in the intervention subcity in Addis Ababa was lower than that of the control subcity. Table 1 summarises the differences and percentage changes in improvement.

Table 1.

The difference-in-difference analysis of eligible U15C enrolled and treated before and after the intervention

| Region | Intervention | Control | ||||

| Eligible | Initiated | % Initiated | Eligible | Initiated | % Initiated | |

| Addis Ababa | ||||||

| Before | 156 | 33 | 21.1 | 43 | 6 | 13.9 |

| After | 234 | 181 | 77.3 | 98 | 58 | 59.2 |

| Difference (%) | 78 (+50%) | 148 (+448%) | 56.2 (+266%) | 55 (+128%) | 52 (+866%) | 45.3 (+326%) |

| SNNPR | ||||||

| Before | 164 | 59 | 35.9 | 466 | 170 | 36.5 |

| After | 1316 | 796 | 60.4 | 677 | 277 | 40.9 |

| Difference (%) | 1152 (+702%) | 737 (+1249%) | 24.5 (+68.2%) | 211 (+45%) | 107 (+63%) | 3.5 (+9.6%) |

| Total | ||||||

| Before | 320 | 92 | 28.7 | 509 | 176 | 34.6 |

| After | 1550 | 977 | 63.05 | 775 | 335 | 43.2 |

| Difference (%) | 1230 (+384%) | 885 (+963%) | 42.6 (+148%) | 266 (+52%) | 159 (+90.3%) | 8.6 (+24.9%) |

In this table, “before” refers to the period July 2019-June 2020 while after refers to the period July 2020-June 2021.

SNNPR, Southern Nations’, Nationalities’ and Peoples’ Region.

The overall rate of TPT initiation in the intervention zones increased from 28.7% to 63.5%. Despite increments in the number of eligible children aged 5–14 years from 194 to 540 in the intervention zones, the TPT initiation rate for this age group declined from 31.9% (62/194) at baseline to 7.4% (40/540) post intervention. In the control districts, the overall TPT initiation rate increased from 34.6% to just 43.2%. There was regional variation with the control subcity in Addis Ababa having the highest percentage point improvement in TPT initiation rate (table 1).

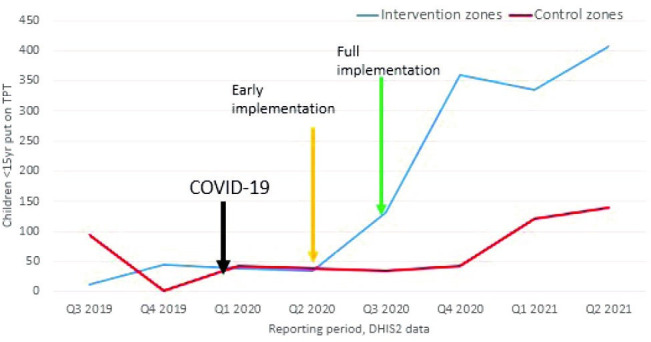

As clearly shown in figure 3, TPT initiation rates started to be visibly different between intervention and control districts starting from the second quarter of 2020 which coincided with the deployment of zonal project officers and the baseline assessment. In the third quarter of 2020, the difference became even wider.

Figure 3.

Trends in the number of under-15-year-old children put on TPT. DHIS-2, District Health Information System; TPT, tuberculosis preventive treatment.

Results from the Poisson regression analyses are presented in table 2 and show significantly higher number of eligible and initiated children, and the number initiated was more than 10 times higher in the intervention zones after the intervention (Exp (β), (95% CI)=10.62 (8.58 to 13.15); p<0.001).

Table 2.

Adjusted Poisson regression analyses showing the impact of Iddir interventions on the number of eligible children and those initiated on tuberculosis preventive treatment

| Factors | Eligible | Initiated |

| Exp (β) (95% CI) | Exp (β) (95% CI) | |

| Control zones | ||

| Time period (after vs before) | 1.52 (1.36 to 1.70) | 1.90 (1.59 to 2.28) |

| Region (SNNPR vs Addis Ababa) | 8.11 (6.81 to 9.66) | 6.99 (5.37 to 9.08) |

| Intervention zones | ||

| Time period (after vs before) | 4.84 (4.29 to 5.46) | 10.62 (8.58 to 13.15) |

| Region (SNNPR vs Addis Ababa) | 3.79 (3.39 to 4.24) | 3.99 (3.44 to 4.64) |

| Combined zones | ||

| Iddir intervention (yes vs no) | 1.46 (1.36 to 1.56) | 2.09 (1.88 to 2.32) |

| Time period (after vs before) | 2.80 (2.59 to 3.04) | 4.89 (4.29 to 5.58) |

| Region (SNNPR vs Addis Ababa) | 4.94 (4.50 to 5.42) | 4.68 (4.11 to 5.33) |

P<0.001 for all factors.

SNNPR, Southern Nations’, Nationalities’ and Peoples’ Region.

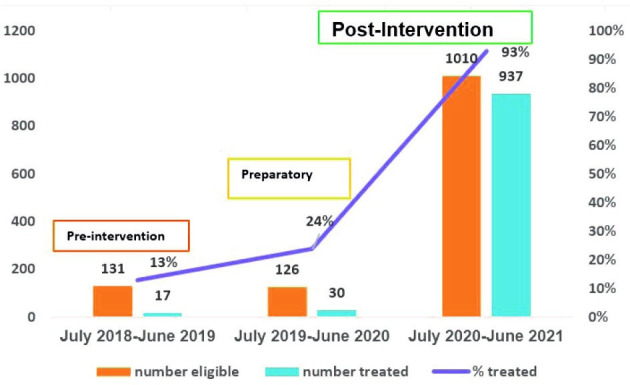

The number of eligible U5C children enrolled during the preintervention period was 131; slightly declined to 126 during the preparatory phase, and then increased dramatically to 1010 during the postintervention period. The proportion of U5C among all eligible children enrolled in the intervention zones increased from 39% (126/320) to 65% (1010/1550). Similarly, taking July 2019–June 2020 as a common baseline for intervention zones, U5C constituted only 33% of those initiated TPT at baseline (30 out of 92), but increased to 96% (937 out of 977) postintervention. The TPT initiation rate for U5C improved steadily from 13% during the preintervention period to 24% during the preparatory phase, and then to 93% during the postintervention period. (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Trends in tuberculosis preventive treatment initiation rate in under-5-year-old children.

Of 937 U5C initiated, 872 (93.1%) received 3RH, 45 (4.8%) 6H and 20 (2.1%) 3HP. Treatment outcome status was available for all the 937 U5C, of whom 99% successfully completed treatment. Treatment was discontinued in two children who had side effects. Three parents refused to continue treatment because they were not convinced why their apparently healthy child needed treatment. Only one child was lost to follow-up.

Discussion

We provide the first report on the beneficial role that engaging Iddirs, locally established community support groups, can have in TB care in Ethiopia. We found that despite a general upwards trend in TPT enrolment in both groups, children in the intervention zone had uptake and acceptance rates that were several times higher than those of control zones. TPT initiation among eligible U5C more than quadrupled after the intervention, and 99% of these children were treated successfully. The results highlight that volunteer women mobilised through Iddirs can serve as additional support to the health system in improving TPT services in the community. This new model of care has a potential for further scale-up in Ethiopia for TB but also other health issues that may require a greater involvement of community care rather than medicalised approaches.

The observed improvement in TPT service uptake sparks an important question about the place of Iddirs in a country where the HEWs are believed to be the anchors of the community health system. Despite improvements the HEWs brought about, several challenges were identified including low productivity and efficiency; poor working and living conditions of HEWs; limited capacity of health posts; and socioeconomic factors of cross-cutting nature.26 While the HEWs will remain the pillar of Ethiopia’s community-based health services, additional results obtained by engaging volunteer groups highlights potential synergies that can be achieved through such interventions. Earlier studies demonstrated that HEWs can be more effective when they receive adequate technical and financial support through well-organised mechanisms.9 10 The evidence from our study adds a fresh perspective that indigenous groups such as Iddirs as time-tested social capitals can serve as a more sustainable addition to the existing arsenal against TB.

Until recently, Iddirs were reluctant to be involved in development activities due to fear of state interference.19 Financial constraints due to high rates of HIV-associated death among young people forced Iddirs to consider alternative sources of income including letting their properties and engaging in development activities. Subsequently, they became more and more involved in issues beyond funeral support, which was their focus initially. A study in Addis Ababa showed several beneficial roles Iddirs play including emotional support, experience sharing, creating opportunities for social interaction and improving leadership roles.27 In our study, at least 30% of those selected in Addis Ababa were active in HIV-related activities, which suggests the continued role Iddirs play in the HIV response in major urban areas. Even more striking is the finding that 70% of the Iddirs were reportedly involved in childcare in Addis Ababa, which shows their evolving focus as the country’s health priorities shift.

Despite clear and much greater improvements in TPT initiation rates between intervention and control zones, the 63.05% TPT initiation rate among U15C is still suboptimal and could be due to several reasons. First, the primary target groups of this project were U5C according to the prevailing national guidelines. In addition, the analysis was based on the routine health system data that were still in transition to incorporate the updated indicators, which may have led to some data quality issues. Nevertheless, the 93% TPT initiation rate achieved among under-5-year-old child contacts in the intervention zones clearly supports the impact of the intervention for service uptake among the intended target beneficiaries. In 2018, nationally reported programmatic data showed TPT initiation rate of 51.6% in U5C.6

In other African settings, TPT uptake rates are dismally low. A recent report from South Africa, for example, shows that only 0.5% of household contacts received TPT.28 A systematic review that included 24 studies on TPT initiation rate showed that TPT initiation rates among all U5C screened ranged from 2.3% to 100%. However, 9 of the 24 studies reported that less than a half of the screened children initiated TPT.12 Further in this review, one of the two studies that reported a 100% TPT initiation rate was from Ethiopia in which the full cascade of care was not described, precluding us from making conclusions about the proportion initiated TPT among eligible children.7 In fact, this study from Ethiopia with TPT completion rate of 12% was the very study that prompted us to look for additional interventions to improve the poor performance of TPT in the country. Similarly, the Indian study that was reported to have a TPT initiation rate of 100% had missed 39% of the children at screening; they initially identified 71 (81%) of the 87 child contacts, screened 53 of the 71, and then put all the 53 on TPT.29 Therefore, the 93% TPT initiation rate among all eligible U5C contacts in our study is on the high end even compared with globally reported rates. Moreover, since the focus of our intervention was U5C, the higher rate of initiation among the U5C compared with the rate among the U15C clearly shows the impact of the interventions.

The TPT success rate of 99% in this study is perhaps the highest ever reported unless proven otherwise through systematic reviews. In a previous TB REACH project that used a community-based approach through HEWs, 91.7% of child contacts completed a 6-month course of TPT.9 In another project that employed comprehensive health facility-based support, treatment completion rate of 6H among child contacts was 80.3%.30 The shorter treatment regimen used in our study can explain only part of the difference as even in a European setting where shorter treatment regimens were used, treatment completion rate among foreign-born patients was 92%.31 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of TPT initiation and completion rates among migrants in low TB incidence countries showed that only 52% of those who initiated completed treatment.32

The difference in performance rates between the urban (Addis Ababa) and rural (SNNPR) intervention sites is worth discussing. The lesser increase in the number of eligible patients enrolled in Addis Ababa could be related to the higher impact of COVID-19 due to stricter restriction of activities implemented especially during the first wave of the pandemic.33 Also, the Iddirs in Addis Ababa were already busy with other competing social activities as shown in our baseline assessment.

Our results should be interpreted cautiously because of some limitations. We cannot demonstrate causality of the Iddir intervention as it was not a randomised trial design. Before–after study designs have inherent limitations such as failure to control for other confounding factors such as general health system support in the area.34 Since the intervention had several inter-related components such as mentoring and supervision by zonal project officers, involvement of community mobilisers and the additional support received from health workers in the catchment health facilities, it is not possible to make effect attribution to involvement of Iddirs alone. Improved recording and reporting of U5C in the intervention zones may have led to apparent improvement in TPT enrolment. However, improvement in recording and reporting practices that followed the national recommendation to expand the age limit for TPT initiation may have led to sustaining TPT initiation and completion rates in control zones, counterbalancing the possible information bias introduced by the intervention. One can also argue about a potential positive impact of change in national guidelines, but our results clearly show relative increase in the proportion of U5C enrolled further confirming the impact of the intervention. It is also highly probable that the Iddir intervention made a clear difference as visual evidence shown in the graphs is a valid way of making inferences in DiD analysis,35 which was further confirmed by the statistical tests.

Conclusion

This is the first comprehensive report of the beneficial role of Iddirs in TB programme implementation in Ethiopia. Engaging women Iddir members contributed to demonstrable increase in TPT initiation rates and high treatment success rates among U5C in two rural zones and in a slum subcity in Ethiopia. These results were achieved in the face of an unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent measures that hampered health service uptake in the country. The results suggest the untapped potential of social networks such as Iddirs in supporting the health system to improve TB service uptake in high TB burden settings.

A more rigorous evaluation and further refinement of the intervention is needed to scale up the approach. Qualitative studies should also be planned to better understand the various intervention subcomponents which contributed to achieving higher TPT initiation and completion rates post-intervention. The role of other indigenous associations both in Ethiopia and in other high TB burden settings should be studied. Further work is needed to better understand how this model of intervention can be sustained without external financial and technical support.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Jacob_Creswell

Contributors: DJ designed the study, acquired resources, supervised implementation, analysed the data, wrote the first and subsequent drafts and approved the final version. DA supervised data collection and implementation, contributed to analysis, reviewed the first and subsequent drafts, and approved the final version. KT, SB and SS collected data, trained health workers and community volunteers, supervised community and health facility workers, reviewed the draft manuscript, and approved the final version. FA and AB oversaw implementation, supervised data collection, reviewed the first and subsequent drafts and approved the final version. AK and JC contributed to data analysis, reviewed the first and subsequent drafts and approved the final version. The contents of the article are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of donors or employers of the authors. DJ is the guarantor of the study

Funding: This project was funded by the STOP TB Partnership under TB REACH Wave 7. The grant number was STBP/TBREACH/GSA/W7-8044.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Aggregate data will be available for sharing immediately after publication.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

Although ethics approval was not needed for the aggregate data analysis, the study was reviewed and approved by Ethics Committees of Addis Ababa (ID-2793/227) and SNNP Regional Health Bureaus (ID-RDG-4-3054) because we intended to analyse side effect profiles of the new drugs based on individual patient data. The health facility data were accessed with full permission of the heads of health facilities.

References

- 1.Houben RMGJ, Dodd PJ. The global burden of latent tuberculosis infection: a re-estimation using mathematical modelling. PLoS Med 2016;13:e1002152. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO . The end TB strategy, 2015. Available: https://www.who.int/tb/strategy/End_TB_Strategy.pdf

- 3.Harries AD, Kumar AMV, Satyanarayana S, et al. The growing importance of tuberculosis preventive therapy and how research and innovation can enhance its implementation on the ground. Trop Med Infect Dis 2020;5:61. 10.3390/tropicalmed5020061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO . Overview: progress towards achieving global tuberculosis targets and implementation of the UN political Declaration on tuberculosis, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khatri UD N. Quality of tuberculosis services assessment in Ethiopia: report: measure evaluation. University of North Carolina, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kebede BA, Fekadu L, Jerene D. Ethiopia’s experience on scaling up latent TB infection management for people living with HIV and under-five child household contacts of index TB patients. Journal of Clinical Tuberculosis and Other Mycobacterial Diseases 2018;10:29–31. 10.1016/j.jctube.2017.12.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garie KT, Yassin MA, Cuevas LE. Lack of adherence to isoniazid chemoprophylaxis in children in contact with adults with tuberculosis in southern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2011;6:e26452. 10.1371/journal.pone.0026452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jerene D, Melese M, Kassie Y, et al. The yield of a tuberculosis household contact investigation in two regions of Ethiopia. int j tuberc lung dis 2015;19:898–903. 10.5588/ijtld.14.0978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datiko DG, Yassin MA, Theobald SJ, et al. A community-based isoniazid preventive therapy for the prevention of childhood tuberculosis in Ethiopia. int j tuberc lung dis 2017;21:1002–7. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yassin MA, Datiko DG, Tulloch O, et al. Innovative community-based approaches doubled tuberculosis case notification and improve treatment outcome in southern Ethiopia. PLoS One 2013;8:e63174. 10.1371/journal.pone.0063174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grace SG. Barriers to the implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy for tuberculosis in children in endemic settings: a review. J Paediatr Child Health 2019;55:278–84. 10.1111/jpc.14359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szkwarko D, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Du Plessis L, et al. Child contact management in high tuberculosis burden countries: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS One 2017;12:e0182185. 10.1371/journal.pone.0182185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ngugi SK, Muiruri P, Odero T, et al. Factors affecting uptake and completion of isoniazid preventive therapy among HIV-infected children at a national referral hospital, Kenya: a mixed quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Infect Dis 2020;20:294. 10.1186/s12879-020-05011-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joshi B, Chinnakali P, Shrestha A, et al. Impact of intensified case-finding strategies on childhood TB case registration in Nepal. Public Health Action 2015;5:93–8. 10.5588/pha.15.0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zawedde-Muyanja S, Nakanwagi A, Dongo JP, et al. Decentralisation of child tuberculosis services increases case finding and uptake of preventive therapy in Uganda. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2018;22:1314–21. 10.5588/ijtld.18.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuen CM, Millones AK, Contreras CC, et al. Tuberculosis household accompaniment to improve the contact management cascade: a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2019;14:e0217104. 10.1371/journal.pone.0217104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Merid Y, Mulate YW, Hailu M, et al. Population-based screening for pulmonary tuberculosis utilizing community health workers in Ethiopia. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2019;89:122–7. 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maes K, Closser S, Tesfaye Y, et al. Volunteers in Ethiopia’s women’s development army are more deprived and distressed than their neighbors: cross-sectional survey data from rural Ethiopia. BMC Public Health 2018;18:258. 10.1186/s12889-018-5159-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pankhurst A, Mariam DH. The iddir in Ethiopia: historical development, social function, and potential role in HIV/AIDS prevention and control. Northeast Afr Stud 2000;7:35–57. 10.1353/nas.2004.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Léonard T. Ethiopian Iddirs mechanisms. Case study in pastoral communities in Kembata and Wolaita, 2013. Inter Aide. Available: wwwinteraideorg/pratiques/sites/default

- 21.Flax VL, Chapola J, Mokiwa L, et al. Infant and young child feeding learning sessions during savings groups are feasible and acceptable for HIV‐positive and HIV‐negative women in Malawi. Matern Child Nutr 2019;15:e12765. 10.1111/mcn.12765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abreha SK, Walelign SZ, Zereyesus YA. Associations between women’s empowerment and children’s health status in Ethiopia. PLoS One 2020;15:e0235825. 10.1371/journal.pone.0235825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fantahun M, Berhane Y, Wall S, et al. Women’s involvement in household decision-making and strengthening social capital—crucial factors for child survival in Ethiopia. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:582–9. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00147.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Columbia Univerisy . Difference-in-Difference estimation, 2013. Available: https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/population-health-methods/difference-difference-estimation [Accessed updated September 30, 2021; cited 2021 October 9].

- 25.InCorporation IBMArmonk NY, ed. SPSS statistics for windows. 25, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Assefa Y, Gelaw YA, Hill PS, et al. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Global Health 2019;15:24. 10.1186/s12992-019-0470-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teshome E, Zenebe M, Metaferia H, et al. Participation and significance of self-help groups for social development: exploring the community capacity in Ethiopia. Springerplus 2014;3:189. 10.1186/2193-1801-3-189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van de Water BJ, Meyer TN, Wilson M, et al. TB prevention cascade at a district hospital in rural Eastern Cape, South Africa. Public Health Action 2021;11:97–100. 10.5588/pha.20.0055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rekha B, Jagarajamma K, Chandrasekaran V, et al. Improving screening and chemoprophylaxis among child contacts in India’s RNTCP: a pilot study. int j tuberc lung dis 2013;17:163–8. 10.5588/ijtld.12.0415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tadesse Y, Gebre N, Daba S, et al. Uptake of isoniazid preventive therapy among Under-Five children: TB contact investigation as an entry point. PLoS One 2016;11:e0155525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0155525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schein YL, Madebo T, Andersen HE, et al. Treatment completion for latent tuberculosis infection in Norway: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis 2018;18:587. 10.1186/s12879-018-3468-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rustage K, Lobe J, Hayward SE. Initiation and completion of treatment for latent tuberculosis infection in migrants globally: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chilot D, Woldeamanuel Y, Manyazewal T. Real-Time impact of COVID-19 on clinical care and treatment of patients with tuberculosis: a multicenter cross-sectional study in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ann Glob Health 2021;87:109. 10.5334/aogh.3481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gasparrini A, Lopez Bernal J. Commentary: on the use of quasi-experimental designs in public health evaluation. Int J Epidemiol 2015;44:966–8. 10.1093/ije/dyv065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wing C, Simon K, Bello-Gomez RA. Designing difference in difference studies: best practices for public health policy research. Annu Rev Public Health 2018;39:453–69. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-013507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Aggregate data will be available for sharing immediately after publication.