Abstract

Objectives:

To assess prevalence and factors associated with low back pain among health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

Methods:

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was employed from August 1 to September 10, 2021. The total sample size was 470 and a multi-stage sampling technique was used. Data were collected through face-to-face interviews and taking Anthropometric measurements. Epi data version 3.1 for data entry and SPSS version 25 for analysis were used. The fitness of the model was checked using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit test. A binary logistic regression analysis was done, and variables with a p-value of less than .025 in univariate analysis were taken to bivariate analysis. Statistically significant was declared at a p-value of less than .05 with an adjusted odds ratio and 95% confidence interval.

Results:

The 1-year prevalence of low back pain among health care providers was 44.2% (95% CI 39.5–48.3). Past medical history of systemic illness, most commonly adopted posture, a job never requiring repeating motions within 60 s difference, belief that working health profession activities at night aggravate low back pain, and job satisfaction were significantly associated with low back pain, believing that working at night aggravated low back pain, (often lift, push, pull carry or move) more than 10 kg alone, and job satisfaction were important risk factors for low back pain.

Conclusion:

About four in 10 health care providers in public hospitals in the Gamo zone were suffering from low back pain. Therefore, using ergonomic equipment and lifting techniques and alternating posture while caring for patients may reduce the burden.

Keywords: Low back pain, prevalence, associated factor, health care providers

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is pain or discomfort in the spinal area between the lower costal margins and gluteal folds with or without radiation to the lower extremities.1,2 Health care providers assist, lift, and transfer patients or other heavy equipment in difficult conditions in countries where aid materials are unavailable. 3 LBP affects health care providers and the quality of care provided to patients. 4 It is the most prevalent musculoskeletal disease that affects 50-80% of the adult population at some point in their lifetime.5,6

It is estimated that over 80% of the population experiences an episode of LBP at some time during life, and about 18% of the population experiences it at any given moment. 7 As stated by the United States burden of disease collaborators, out of all diseases and injuries contributing to disability-adjusted life years, LBP is in the third rank and is a major cause of activity limitation among individuals aged less than 45 years. 6 Globally, LBP is found to have the sixth-highest burden and to cause more disability. 7 Sixteen percent of sick leave days—that accumulate to a loss of 28 to 146 million working days annually—are attributed to LBP.5,8 At the moment, it has been a major problem in low- and middle-income countries. 9

Various risk factors have been implicated in the etiology, and LBP is a multi-factorial origin of individual, work-related, psychosocial, and environmental factors.10,11 The big issue here is that LBP affects the working population, increases absenteeism, and decreases productivity. Health care professionals suffer musculoskeletal injuries more frequently than other professional groups, and it is also more frequent among health care professionals whose work requires the lifting of dependent patients. 12

Even though the literature on the prevalence of LBP has accumulated, studies have been limited to developed countries. 13 There is still limited information on LBP among health care providers in Ethiopia, especially concerning the risk factors. 12 Therefore, this study was designed to investigate the prevalence of LBP and associated factors among health care providers working in public hospitals in Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted in Gamo zone, South Nation Nationalities, and the Peoples Region. Gamo zone is located 454 km away south of Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia. The population of the Gamo zone is estimated to be 1,852, 000 (based on the initial data separating the previous Gamo Gofa zone into Gamo zone and Gofa zone in 2019). There are 14 districts and six town administrations in the Gamo zone. There are one general and five district hospitals, namely, Arba Minch general hospital, Kamba district hospital, Grasse district hospital, Chencha district hospital, Dilfana district hospital, and Selamber district hospital. The study was conducted from August 1 to September 10, 2021.

Study design

An institution-based cross-sectional study design was employed.

Source population

All health care providers working in public hospitals of Gamo zone.

Study population

The study population is all the selected health care providers working in public hospitals in the Gamo zone.

Inclusion criteria

Criteria were all permanently employed health care providers working in public hospitals of the Gamo zone.

Exclusion criteria

Criteria were health care providers who worked for less than 12 months in public hospitals of Gamo zone and health care providers who were pregnant.

Sample size determination

The sample size was determined using Epi Info version 7 considering assumptions of confidence level of 95%, power of 80%, a ratio of percent exposed to unexposed of 1:1, and taking an adjusted odds ratio from a previous study. 12 A non-response rate of 5% and a design effect of 1.5 were considered (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sample size determination of LBP among health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variables | % in unexposed | AOR | Sample size | Non-response rate | Design effect | Total sample size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year of experience | 26.0 | 3.13 | 121 | 5% | 1.5 | 191 |

| Work in an awkward position | 75.6 | 3.39 | 201 | 5% | 1.5 | 211 |

| Lifting weight > 10 kg manually | 88.8 | 5.26 | 298 | 5% | 1.5 | 470 |

LBP: low back pain; AOR: adjusted odds ratio.

The largest of the three calculated sample sizes was 470 which was the final sample size.

Sampling technique

There were different numbers of health care providers working in public hospitals in the Gamo zone. Four hundred and sixteen health care providers were working in Arba Minch General hospital, 212 health care providers working in Kamba district hospital, 201 health care providers working in Geresse district hospital, 204 health care providers working in Chencha district hospital, and 198 health care providers working in Selamber district hospital.

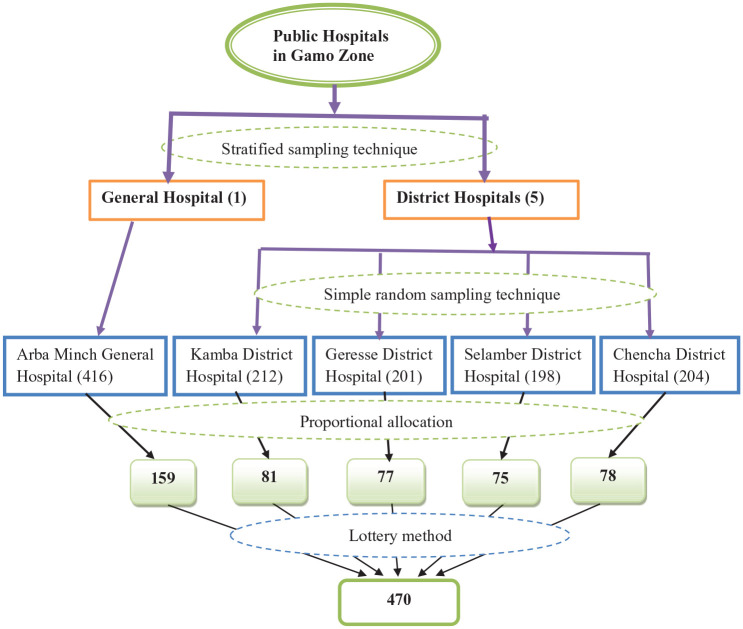

A stratified sampling technique was used to include one general hospital and four district hospitals (Figure 1). Then, a simple random sampling technique was used to include four district hospitals from five district hospitals. Next, by using the number of health care providers in each hospital (both general and district), the required participants were determined by proportional allocation. Finally, the health care providers were selected by using simple random sampling (lottery method) using their registration number at the respective hospital.

Figure 1.

Sampling procedure of LBP among health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

Diagrammatic presentation of sampling

Study variables

Dependent variable

LBP.

Independent variables

Socio-demographic factors

Age, gender, marital status, educational status, and monthly income.

Personal factors

Weight, height, BMI in kg/m2, smoking cigarettes, drinking alcohol, ever chewed chat, practice physical exercise, and past medical systemic illness.

Ergonomic factors

Job involving bending or twisting, working in the same position, most commonly adopted posture, the job requiring repeating motions, (often lift, push, pull, carry, or move) alone, (often lift, push, pull, carry, or move) more than 10 kg alone, training on ergonomics-related issues, exert great force, and sufficient space to do work.

Occupational factors

Work experience, professional line, and working unit, days spend on work per week, hours spent on work per day, type of health facility currently working, asks for assistance, uses assistive devices, adequate rest interval, shortage of staff, frequency of work condition, and believe working at night aggravates LBP.

Psychosocial factors

Job stress and job satisfaction.

Operational and definition of terms

Health care providers

Those health care professionals who give health care to clients. This study included a physician, nurse, public health officer, pharmacy technician, laboratory technician, midwife, anesthesia, and optometry nurse.

LBP

Pain or discomfort in the spinal area between the lower costal margins and gluteal folds with or without radiation to the lower extremities. It was measured by taking the responses to the question; had LBP in the last year before the data collection period. Then, categorized as have LBP (if responded yes) and no LBP (if responded no).1,12

Job stress

Measured by using eight questions that ask about job stress. Each question was rated in five workplace stress scale responses (that is; 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, and 5 = usually). Then, the response was computed, coded, and categorized as yes (if scored mean and above) and no (if scored below mean). 12

Job satisfaction

Measured by using nine questions that ask about job satisfaction. Each question was rated on a five-point Likert-type scale response (i.e., 1 = very dissatisfied, 2 = dissatisfied, 3 = neutral, 4 = satisfied, and 5 = very satisfied). Then, the response was computed, coded, and categorized as satisfied (if scored mean and above) and not satisfied (if scored below mean). 12 Cronbach’s alpha test was analyzed and it was 0.767.

Data collection techniques

Data were collected through face-to-face interviews with the questionnaire, which was prepared in the English version. Then, it was translated to Amharic (the official work language of Ethiopia) and retranslated back to English for consistency by language experts. Anthropometric measurements of the weight (kg) and height (m) of the participants were also measured. A digital weight scale was used for measuring weight, and height was measured using a standard meter. Body mass index (kg/m2) was calculated from weight and height.

Data quality control

A pretest was carried out on 5% of the total sample size (24 health care providers) among health care providers working in Sawula general hospital. Five data collectors and two supervisors were recruited and got training before data collection on how to properly fill out the questionnaire. Data completeness, accuracy, and clarity were checked daily by supervisors. The overall work was managed and supported by investigators.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered by using EpiData version 3.1 and analyzed using SPSS version 25 software. Descriptive findings were presented as frequency tables, percentages, and graphs. To check the interaction among independent variables, multi-collinearity was checked. The fitness of a good model was checked by using the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fittest. To determine the independent variables associated with LBP, binary logistic regression analysis was done, and variables with a p-value of less than .025 in univariate analysis were taken into bivariate logistic regression analysis. Statistical significance was declared at a p-value less than .05 in adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) in bivariate logistic regression analysis.

Result

Socio-demographic characteristics of health care providers

Four hundred and sixty-eight health care providers gave a response, which made the overall response rate 99.6%. Most, 375 (80.1%) of the health care providers were in the age group of 25–29 years. More than half 254 (54.3%) of health care providers were males. A total of 234 (50.0%) health care providers were married, and also the educational level of the half 234 (50.5%) was a diploma (Table 2).

Table 2.

Socio-demographic characteristics of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variable (n = 468) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ⩽24 | 6 | 1.3 |

| 25–29 | 375 | 80.1 | |

| 30–34 | 28 | 6.0 | |

| 35–39 | 30 | 6.4 | |

| ⩾40 | 29 | 6.2 | |

| Gender | Male | 254 | 54.3 |

| Female | 214 | 45.7 | |

| Marital status | Single | 222 | 47.4 |

| Married | 234 | 50.0 | |

| Widowed | 7 | 1.5 | |

| Divorce | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Educational status | Diploma | 234 | 50.0 |

| BSc degree | 211 | 45.1 | |

| MSc degree | 23 | 4.9 | |

| Monthly income | 4000–5500 ETB | 204 | 43.6 |

| 5501–7000 ETB | 90 | 19.2 | |

| ⩾7001 ETB | 174 | 37.2 |

BSc: Bachelor of sciences, MSc: master of sciences, ETB: Ethiopian Birr.

Personal factors of the health care providers

The BMI of 281 (60.0%) was within 18.6–24.5 Kg/m2 and most 449 (95.9%) of health care providers did not smoke a cigarette at least a stick a day. About 442 (94.4%) of health care providers did not drink alcohol at least twice a week and 442 (94.4%) of health care providers practice physical exercise at least twice a week for 30 min. About 445 (95.1%) of them did not ever chew chat and only 30 (6.4%) of the health care providers had a past medical history of systemic illness (Table 3).

Table 3.

Personal factors of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variable (n = 468) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI in kg/m2 | ⩽18.5 | 21 | 4.5 |

| 18.6–24.5 | 281 | 60.0 | |

| 24.6–29.9 | 161 | 34.4 | |

| ⩾30 | 5 | 1.1 | |

| Smoke cigarettes at least stick a day | Yes | 19 | 4.1 |

| No | 449 | 95.9 | |

| Drink alcohol at least twice a week | Yes | 26 | 5.6 |

| No | 442 | 94.4 | |

| Ever chewed chat | Yes | 23 | 4.9 |

| No | 445 | 95.1 | |

| Chewed chat in the last 30 days (n = 23) | Yes | 15 | 65.2 |

| No | 8 | 34.8 | |

| Practice physical exercise at least twice a week for 30 minutes | Yes | 442 | 94.4 |

| No | 26 | 5.6 | |

| Past medical history of systemic illness (DM, thyroid, chronic renal, gout) | Yes | 30 | 6.4 |

| No | 438 | 93.6 |

BMI: body mass index, kg/m2: kilogram per meter square, DM: diabetes mellitus.

Ergonomic factors of the health care providers

More than half of the health care providers’ jobs, 269 (57.5%) sometimes involve bending or twisting and 279 (59.6%) of health care providers work sometimes in the same position for more than 2 h. The most commonly adopted posture for most health care providers was standing, which accounted for 312 of health care providers 66.7% and about 61.3% of those whose work sometimes requires repeating motions within 60 s difference. More than half 279 (59.6%) of the health care providers often lift, push, pull, carry, or move alone, and 217 (46.4%) of the health care providers often lift, push, pull, carry, or move more than 10 kg alone and only 29 (6.2%) of the health care providers got any training on ergonomics-related issues. About 35.5% of health care providers exerted great perceived force to operate tools and machinery, and 194 (41.5%) of health care providers work in a space that is sufficient to do work properly (Table 4).

Table 4.

Ergonomic factors of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variable (n = 468) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| The job involves bending or twisting | Never | 163 | 34.8 |

| Sometimes | 269 | 57.5 | |

| Always | 36 | 7.7 | |

| Work in the same position for more than 2 h (standing, bending over, or sitting) | Never | 129 | 27.6 |

| Sometimes | 279 | 59.6 | |

| Always | 60 | 12.8 | |

| Most commonly adopted a posture | Standing | 312 | 66.7 |

| Sitting | 97 | 20.7 | |

| Bending | 59 | 12.6 | |

| The job requires repeating motions within 60 s of difference | Never | 80 | 17.1 |

| Sometimes | 287 | 61.3 | |

| Always | 101 | 21.6 | |

| Often lift, push, pull, carry or move alone | Yes | 279 | 59.6 |

| No | 189 | 40.4 | |

| Often lift, push, pull, carry or move more than 10 kg alone | Yes | 217 | 46.4 |

| No | 251 | 53.6 | |

| Got any training on ergonomics-related issues | Yes | 29 | 6.2 |

| No | 439 | 93.8 | |

| Exert great force to operate tools and machinery | Yes | 157 | 35.5 |

| No | 311 | 66.5 | |

| Sufficient space to do work properly | Yes | 194 | 41.5 |

| No | 274 | 58.5 |

Occupational factors of the health care providers

More than half 264 (56.4%) of the health care providers had work experience of less than or equal to 5 years, 235 (63.0%) were nurses, and almost half 233 (49.8%) of the health care providers worked inward. Nearly half 239 (51.1%) of the health care providers spend 5 days at work per week and 461 (98.5%) spend 8 h at work per day. More than half 309 (66.0%) of the health care providers work in the district hospitals. More than half 325 (69.4%) of the health care providers ask for assistance when performing patient handling activities, and 301 (64.3%) of the health care providers use assistive devices for patient handling activities. More than half 248 (53.0%) of the health care providers had adequate rest intervals, and there was a shortage of staff in the working unit for 295 (63.0%) health care providers. The frequency of work condition status for 393 (84%) of the health care providers was sometimes day or night on shift, and 159 (34.0%) of the health care providers believed that working at night aggravated LBP (Table 5).

Table 5.

Occupational factors of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variable (n = 468) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work experience | ⩽5 year | 264 | 56.4 |

| >5 year | 204 | 43.6 | |

| Professional line | Physician | 32 | 6.8 |

| Nurse | 295 | 63.0 | |

| Public health officer | 15 | 3.2 | |

| Pharmacy technician | 23 | 4.9 | |

| Laboratory technician | 31 | 6.6 | |

| Midwife | 54 | 11.5 | |

| Others (Anesthesia, Optometry) | 18 | 3.8 | |

| Working unit | Outpatient department | 109 | 23.3 |

| Ward | 233 | 49.8 | |

| Intensive care unit | 57 | 12.2 | |

| Operation room | 16 | 3.4 | |

| Others (drug dispensary, laboratory) | 53 | 11.3 | |

| Days spent on work per week | 5days | 239 | 51.1 |

| >5 days | 229 | 48.9 | |

| Hours spend on work per day | <8 h | 3 | 0.6 |

| 8h | 461 | 98.5 | |

| >8 h | 4 | 0.9 | |

| Type of health facility currently working | General hospital | 159 | 34.0 |

| District hospital | 309 | 66.0 | |

| Asks assistance when performing patient handling activities | Yes | 325 | 69.4 |

| No | 143 | 30.6 | |

| Uses assistive devices for patient handling activities like bed remote | Yes | 301 | 64.3 |

| No | 167 | 35.7 | |

| Adequate rest interval | Yes | 248 | 53.0 |

| No | 220 | 47.0 | |

| Shortage of staff in the working unit | Yes | 295 | 63.0 |

| No | 173 | 37.0 | |

| Frequency of work condition status | Day | 75 | 16.0 |

| Sometimes day or night on shift | 393 | 84.0 | |

| A belief that working at night aggravates low back pain | Yes | 159 | 34.0 |

| No | 309 | 66.0 |

Job stress of health care providers

Job stress of health care providers in public hospitals is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Job stress of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

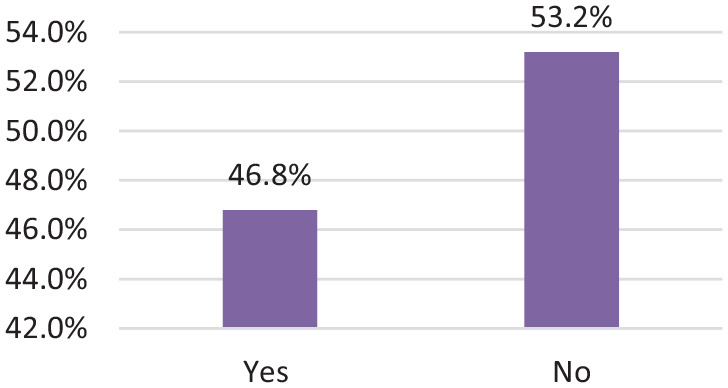

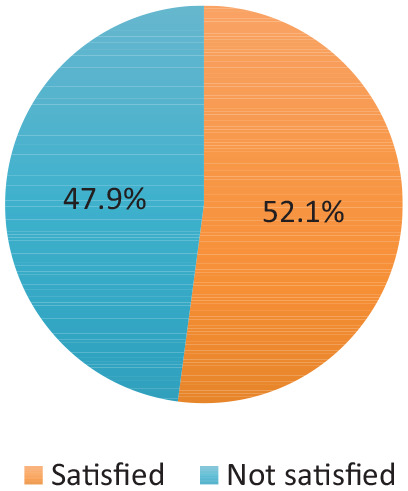

Job satisfaction of health care providers

Job satisfaction of health care providers in public hospitals is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Job satisfaction of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

LBP among health care providers

Less than half 207 (44.2%) of health care providers had LBP, and it is infrequent for 181 (87.4%) of the health care providers. More than half 162 (78.3%) of the health care providers felt pain in lower extremities and other body parts and 171 (82.6%) of health care providers had LBP during the last 7 days. A majority, 189 (91.3%) of the health care providers ever suffer from LBP before working as a health care professional, and 185 (89.8%) of health care providers have ever been absent from work in the past year due to LBP (Table 6).

Table 6.

Low back pain among health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variable (n = 468) | Category | Frequency | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Had low back pain in the last 1 year | Yes | 207 | 44.2 |

| No | 261 | 55.8 | |

| Repeatability of LBP (n = 207) | Infrequent (<3 days per week) | 181 | 87.4 |

| Frequent (3–5 days per week) | 11 | 5.3 | |

| Daily (7 days per week) | 15 | 7.2 | |

| Feel pain in lower extremities and other body parts (n = 207) | Yes | 162 | 78.3 |

| No | 45 | 21.7 | |

| Had low back pain during the last 7 days (n = 207) | Yes | 171 | 82.6 |

| No | 36 | 17.4 | |

| Ever suffer from LBP before working as a health professional (n = 207) | Yes | 189 | 91.3 |

| No | 18 | 8.7 | |

| Ever been absent from work for last year due to LBP (n = 207) | Yes | 185 | 89.8 |

| No | 21 | 10.2 |

LBP: low back pain.

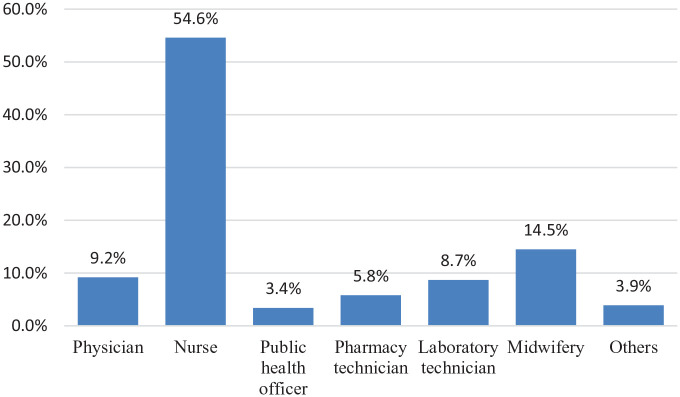

Prevalence of LBP regarding professional line

In this study, the prevalence of LBP among professional lines slightly varied for each professional line. It was 79 (9.2%) in physicians, 113 (54.6%) in nurses, 7 (3.4%) in public health officers, 12 (5.8%) in pharmacy technicians, 18 (8.7%) in laboratory technicians, 30 (14.5%) in midwifery, and 8 (3.9%) in others (anesthesia and optometry) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Prevalence of LBP regarding the professional line of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

Others: anesthesia, optometry.

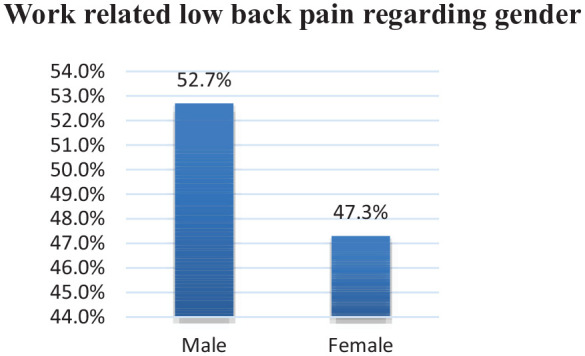

Prevalence of LBP regarding gender

Of the 207 health care providers who had LBP, 109 (52.7%) were male and 98 (47.3%) were female (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Prevalence of LBP regarding the gender of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

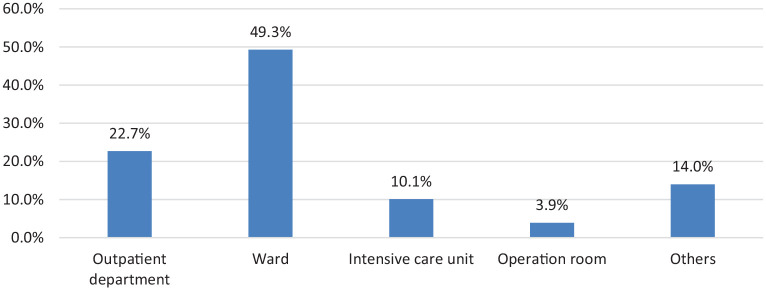

Prevalence of LBP regarding working unit

Of the 207 health care providers who had LBP, 47 (22.7%) worked in the outpatient department, 102 (49.3%) worked inward, 21 (10.1%) worked in the intensive care unit, 8 (3.9%) operation room and 29 (14.0%) working in others (drug dispensary and laboratory) had LBP (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Prevalence of LBP regarding working unit of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

Others: drug dispensary, laboratory.

Factors associated with LBP

In univariate analysis, age, educational status, body mass index, practice physical exercise at least twice a week for 30 min, past medical history of systemic illness, job involving bending or twisting, most commonly adopted posture, the job requires repeating motions within 60 s difference, often lift, push, pull, carry or move alone, often lift, push, pull, carry or move more than 10 kg alone, sufficient space to do work properly, adequate rest interval, belief that working at night aggravates LBP and job satisfaction were associated with LBP. Whereas, in bivariate analysis; a past medical history of systemic illness (AOR: 4.32, 95% CI 1.58–11.78), most commonly adopted sitting posture (AOR: 2.74, 95% CI 1.38–5.41), most commonly adopted bending posture (AOR: 3.29, 95% CI 1.47–7.37), the job requires repeating motions within 60 seconds difference (AOR: 1.76, 95% CI 1.01–3.07), often lift, push, pull carry or move more than 10 kg alone (AOR: 0.38, 95% CI 0.23–0.62), belief that working at night aggravate LBP (AOR: 1.86, 95% CI 1.16–2.96), and job satisfaction (AOR: 1.83, 95% CI 1.14–2.95) were significantly associated with LBP (Table 7)

Table 7.

Univariate and bivariate analysis of health care providers in public hospitals of Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia, 2021.

| Variables (n = 468) | Category | LBP | COR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No LBP | Have LBP | |||||

| Educational status | Diploma | 132 (28.2%) | 102 (21.8%) | 1 | 1 | |

| BSc degree | 123 (26.3%) | 88 (18.8%) | 0.27 (0.10–0.72) | 0.49 (0.15–1.66) | .253 | |

| MSc degree | 6 (1.3%) | 17 (3.6) | 0.25 (0.09–0.67) | 0.34 (0.11–1.05) | .060 | |

| Past medical history of systemic illness | Yes | 23 (4.9%) | 7 (1.5%) | 2.76 (1.16–6.57) | 4.32 (1.58–11.78) | .004* |

| No | 238 (50.9%) | 200 (42.7%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| The job involves bending or twisting | Never | 73 (15.6%) | 90 (19.2%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Sometimes | 162 (34.6%) | 107 (22.9%) | 3.21 (1.45–7.08) | 1.56 (0.63–3.86) | .338 | |

| Always | 26 (5.6%) | 10 (2.1%) | 1.72 (0.79–3.72) | 1.07 (0.45–2.54) | .874 | |

| Most commonly adopted the posture | Standing | 168 (35.9%) | 144 (30.8%) | 1 | 1 | |

| Sitting | 51 (10.9%) | 46 (9.8%) | 2.12 (1.15–3.88) | 2.74 (1.38–5.41) | .004* | |

| Bending | 42 (9.0%) | 17 (3.6%) | 2.23 (1.12–4.44) | 3.29 (1.47–7.37) | .004* | |

| The job requires repeating motions within less than 60 s of difference | Never | 32 (6.8%) | 48 (10.3%) | 2.71 (1.48–4.96) | 5.40 (2.49–11.71) | .000* |

| Sometimes | 164 (35.0%) | 123 (26.3%) | 1.35 (0.85–2.17) | 1.76 (1.01–3.07) | .045* | |

| Always | 65 (13.9%) | 36 (7.7%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Often lift, push, pull, carry or move alone | Yes | 136 (29.1%) | 143 (30.6%) | 0.49 (0.33–0.71) | 0.89 (0.54–1.46) | .649 |

| No | 125 (26.7%) | 64 (13.7%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Often lift, push, pull carry or move more than 10 kg alone | Yes | 10 (21.4%) | 117 (25.0%) | 0.48 (0.33–0.69) | 0.38 (0.23–0.62) | .000* |

| No | 161 (34.4%) | 90 (19.2%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Have sufficient space to do work properly | Yes | 92 (19.7%) | 102 (21.8%) | 0.56 (0.39–0.81) | 0.84 (0.52–1.36) | .474 |

| No | 169 (36.1%) | 105 (22.4%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Have adequate rest interval | Yes | 121 (25.9%) | 127 (27.1%) | 0.54 (0.38–0.79) | 0.76 (0.47–1.22) | .261 |

| No | 140 (29.9%) | 80 (17.1%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Believe working health profession activities at night aggravate LBP | Yes | 108 (23.1%) | 51 (10.9%) | 2.16 (1.45–3.22) | 1.86 (1.16–2.96) | .009* |

| No | 153 (32.7%) | 156 (33.3%) | 1 | 1 | ||

| Job satisfaction | Satisfied | 149 (31.8%) | 95 (20.3%) | 1.57 (1.09–2.26) | 1.83 (1.14–2.95) | .013* |

| Not satisfied | 112 (23.9%) | 112 (23.9%) | 1 | 1 | ||

COR: crude odds ratio, AOR: adjusted odds ratio, BSc: Bachelor of sciences, MSc: master of sciences, ETB: Ethiopian birr, LBP: low back pain.

p < .05 statistically associated; “1” reference group.

Discussion

The one-year prevalence of LBP among health care providers was 44.2% (95% CI 39.5–48.3). It was in line with the LBP study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, (45.8%), 10 Harari Region and Dire Dawa City Administration, Eastern Ethiopia (38.1%), 12 Ibadan, Nigeria (44.1%), 14 Norway (43%), 15 Iran (46.2%) 16 and India (45%). 17 It was lower than the prevalence of LBP in Gondar town, Ethiopia (64%), 18 South Africa (59%), 19 Zigazig Hospital, Egypt (79%), 20 Kanombe Military Hospital, Rwanda (78%), 21 Malaysia (56.9%), 22 Nigerian hospital (73%), 23 Taiwan (72%) 24 and medical students in Belgrade (59.5%). 7 This might be due to the available status of patient lifting equipment in the hospitals. It also might be due to the inclusion of a variety of health professionals in addition to nurses in this study, the difference in settings of the working environment, and the workload of health care providers.

However, it was higher than the annual prevalence of LBP among health care providers in tertiary health institutions in Sokoto, Nigeria (39.1%), 9 Bangladesh (35%), 25 and (36.2%). 26 This might be due to the sampling size variation of the studies, the difference in settings of the working environment, the reporting behavior of study participants, and the duration of workload among health care providers.

In this study, the prevalence of LBP for each profession was assessed, and it showed variation from profession to profession. The prevalence of LBP among physicians was 28.1%. It was lower than a study in Turkey (63.3%). 27 This might be due to the differences in hospital settings and the self-reported status of the nurses can also cause variation in results. The prevalence of LBP was 38.3%. It was lower than a study in Turkey (77.1%), 27 Nigeria (73.53%), 23 and Riyadh (65%). 28 This might be due to the differences in hospital settings and the nurses’ awareness to take care of themselves during patient handling. The reporting status of the nurses can also cause variation in the results. Among public health officers were 46.7%, pharmacy technician was 52.2%, laboratory technician was 58.1%, midwife was 55.5%, and anesthesia and optometry in combination was 44.4%. This variation within the professional line might be due to the nature of the care provided for patients. Also, LBP for health care professionals has multiple risk factors. 29

In this study, the prevalence of LBP in each working unit was assessed, and it showed variation among working units. It was 49.3% in the ward, 22.7% in the outpatient department, 14.1% in the drug dispensary and laboratory in combination, 10.1% in the intensive care unit, and 3.9% in the operation room. This difference might be due to the patients’ physical condition and the availability of lifting equipment in the working units. For example, most patients in the ward are patients who need frequent positioning. Then, patients come to the outpatient department, and the operating room and the intensive care unit are well equipped for lifting and positioning patients.

Health care providers whose monthly income ranged from 5501 to 7000 ETB were 55% times less likely to have LBP and health care providers whose monthly income was greater than 7001 ETB were 62% times less likely to have LBP compared to health care providers whose monthly income ranged from 4000 to 5501 ETB. This was reversely stated in a study that showed multiple domains such as social relationships, social roles, family duties, and life satisfaction affect the occurrence of LBP. 29 This disparity might be due to an imbalance between the level of income and handling the requirements for basic, personal, familial, and social needs.

In this study, past medical history of systemic illness was statistically associated with LBP. Health care providers who had a past medical history of systemic illness were 4.32 times more likely to have LBP compared to health care providers who had no past medical history of systemic illness. This was stated in another study, chronic fatigue syndrome was found to be statistically associated with LBP. 30 In another study, a positive history of back trauma was determined as a risk factor for LBP. 31 This might be due to the synergic effect of the past medical history of systemic illness and health care activities, which increased the occurrence of LBP. The difference in stating the variable was as a result of the nature of pain, as it is a subjective sensation that different individuals respond to it in various ways.

The most commonly adopted posture was significantly associated in this study. Health care providers whose most commonly adopted posture was sitting were 2.74 times more likely to have LBP and health care providers whose most commonly adopted posture was bending were 3.29 times more likely to have LBP compared to health care providers whose most commonly adopted posture was standing. This finding was stated as nurses who worked in an awkward position were more likely to develop LBP in different ways.11,12,22,23,32 –35 The reason for this might be similarity nature of health providers activities in any part of the world in which providing care requires standing sitting and bending postures. In a study conducted in South Nigeria, prolonged sitting or standing in the same posture was determined as a risk factor for LBP. 36 Similarly, in Ibadan, southwest Nigeria, bending and staying in the same position for more than three hours was a significant risk factor for LBP. 14 This might be due to the physiological condition of muscles that prolonged stay enhances muscle fatigue and causes pain.

Health care providers whose job never requires repeating motions within 60 s difference were 5.4 times more likely to have LBP and health care providers whose job sometimes requires repeating motions within 60 s difference were 1.76 times more likely to have LBP compared to health care providers whose job always requires repeating motions within 60 s difference. This might be related to physical inactivity, as an absence of motion increases muscle fatigue and leads to lower back pain.

In this study, often lifting, pushing, pulling, carrying, or moving more than 10 kg alone was significantly associated with LBP. Health care providers who often lift, push, pull carry or move more than 10 kg alone were 62% times less likely to have LBP compared to health care providers who did not lift, push, pull, carry, or move more than 10 kg alone. However, this was reversely associated in other studies; in Harar Region and Dire Dawa City Administration, Eastern Ethiopia, 12 Makah, Saudi Arabia, 32 Doha, Qatar, 27 Ankara, Turkey, 27 South Nigeria, 36 Taif, Saudi Arabia, 11 Kenya, 37 and Zagazig University Hospital, Egypt. 20 This reverse association might be due to the appropriate use of body mechanics while weight lifting and has gained some important intervention mechanisms for health care providers about how to lift objectives without affecting themselves. It was similar to a study conducted in South Africa that started lifting, bending, pulling, pushing, and sustained positions were identified as risk factors. 38 It was supported by a study in tertiary health institutions in Sokoto, Nigeria. 9 In other studies, the manual handling performed by nurses was stated as an important factor for LBP.22,38 This was the same as a study conducted in public hospitals in Eastern Ethiopia stated that nurses who manually lifted a weight of greater than 10 kg were more likely to experience LBP compared to those who did not. 12

Health care providers who believe that working health profession activities at night aggravate LBP were 1.86 times more likely to have LBP compared to health care providers who did not believe that working health profession activities at night aggravate LBP. This might be a reason that those health care providers assigned at night were off day time, and thus, they may have other personal activities, and being busy during both day and night can induce LBP. The other possible reason for it might be the perception of subjective and self-explanatory as night is a resting and sleeping time.

Job satisfaction was also statistically associated in this study with LBP. Health care providers who were not satisfied with their jobs were 1.83 times more likely to have LBP compared to health care providers who were satisfied with their jobs. This was similarly stated in a study that showed independence in satisfying one’s own needs and life satisfaction. 29 Job satisfaction showed a significant association in another study. 38 The possible reason for this might be that satisfied health care providers can have internal pleasure and relaxation in the work environment.

Limitation of the study

Selecting study participants from only public hospitals could be a limitation of this study, and it may also have recall bias as it asks back one year.

Conclusion

About four in 10 health care providers working in public hospitals in the Gamo zone were suffering from LBP. Past medical history of systemic illness, most commonly adopted posture, a job that never required repeating motions within 60 s difference, often lift, push, pull, carry or moved more than 10 kg alone, a belief that working at night aggravated LBP, and job satisfaction were important risk factors for LBP. Therefore, taking appropriate treatment for systemic illness, using appropriate lifting techniques during patient handling and alternating posture while caring for patients, refreshing the belief that working at night aggravates LBP, and being satisfied with the job may reduce the burden of LBP among health care providers.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for being voluntary and giving the necessary information, data collectors, and supervisors.

Footnotes

Author contributions: All authors made a significant contribution to the work reported, whether that is in the conception, study design, execution, acquisition of data, analysis, and interpretation, or in all areas; took part in drafting, revising, and critically reviewing the article; gave final approval of the version to be published; have agreed on the journal to which the article has been submitted; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Availability of data: The data analyzed were available with the corresponding author.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical consideration: The ethical approval and clearance were obtained from the institutional research ethics committee of Paramed College, Arba Minch (PC/AM/28/13). A permission letter was obtained from each hospital administrates.

Informed consent: Written informed consent was given for each participant as the information obtained from them would not have been disclosed to a third person and it was only for investigation purposes.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Elias Ezo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6428-6541

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6428-6541

References

- 1. Yehualaw W. Assessment of self-reported low back pain and associated factors among nurses working in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at public and private hospitals, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Amirah F. Low back pain among nurses in orthopedic and intensive care unit at Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre: the incidence, impacts, and level of disability. Selangor, Malaysia: IIUM, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Yitayeh A, Mekonnen S, Fasika S, et al. Annual prevalence of self-reported work-related musculoskeletal disorders and associated factors among nurses working at Gondar Town Governmental Health Institutions, Northwest Ethiopia. Emerg Med (Los Angel) 2015; 5(227): 2. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sikiru L, Shmaila H. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among nurses in Africa: Nigerian and Ethiopian specialized hospitals survey study. East Afr J Public Health 2009; 6(1): 22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thon C, Feng P, Lian C. Risk factors of low back pain among nurses working in Sarawak General Hospital. Health 2016; 7(1): 13–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murray C, Abraham J, Ali M, et al. The state of US health, 1990–2010: burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. JAMA 2013; 310(6): 591–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Vujcic I, Stojilovic N, Dubljanin E, et al. Low back pain among medical students in Belgrade (Serbia): a cross-sectional study. Pain Res Manag 2018; 2018: 8317906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Duthey B. Priority medicines for Europe and the world: a public health approach to innovation. WHO Background Paper, WHO, Geneva, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Awosan KJ, Yikawe SS, Oche OM, et al. Prevalence, perception and correlates of low back pain among healthcare workers in tertiary health institutions in Sokoto, Nigeria. Ghana Med J 2017; 51(4): 164–174. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Belay M, Worku A, Gebrie S, et al. Epidemiology of low back pain among nurses working in public hospitals of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. East Cent Afr J Surg 2016; 21(1): 113–131. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hasan M, Keriri S. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among nurses in operating rooms, Taif, Saudi Arabia. Am J Res Comm 2013; 1(11): 45–70. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mijena GF, Geda B, Dheresa M, et al. Low back pain among nurses working at public hospitals in Eastern Ethiopia. J Pain Res 2020; 13: 1349–1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arero AG, Arero G, Mohammed SH, et al. Prevalence of low back pain among working Ethiopian population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol Health Sci. Epub ahead of print 24 November 2020. DOI: 10.1101/2020.11.29.20238170. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tinubu B, Mbada C, Oyeyemi A, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among nurses in Ibadan, South-west Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010; 11(1): 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Woodhouse A, Pape K, Romundstad P, et al. Health care contact following a new incident neck or low back pain episode in the general population: the Hunt study. BMC Health Serv Res 2016; 16(81): 81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rezaee M, Ghasemi M. Prevalence of low back pain among nurses: predisposing factors and role of work place violence. Trauma Mon 2014; 19(4): e17926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mendhe H, Hanumanth N, Harika G. A study on musculoskeletal disorders distribution and health-seeking behavior among geriatric people in the field practice area of rural health and training center of a tertiary care hospital. Int J Med Sci Public Health 2016; 5(11): 2226–2229. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mekonnen TH, Yenealem DG. Factors affecting healthcare utilization for low back pain among nurses in Gondar town, northwest Ethiopia, 2018: a cross-sectional study. BMC Res Notes 2019; 12: 185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dlungwane T, Voce A, Knight S. Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain among nurses at a regional hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health SA 2018; 23: 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Abou E, Soud A, El-Najjar A, et al. Prevalence of low back pain in working nurses in Zagazig University Hospitals: an epidemiological study. Egypt Rheumatol Rehabil 2014; 41(3): 109. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lela M, Frantz J. Physical activity among nurses in Kanombe Military Hospital. S Afr J Physiother Rehabil Sci 2012; 4(1–2): 63–66. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mohd I, Najib M, Mohd I, et al. Low back pain and its associated factors among nurses in public hospitals of Penang, Malaysia. Malaysian Orthoped J 2010; 4(2): 23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sikiru L, Hanifa S. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among nurses in a typical Nigerian hospital. Afr Health Sci 2010; 10(1): 26–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shieh S, Sung F, Su C, et al. Increased low back pain risk in nurses with the high workload for patient care: a questionnaire survey. Taiwanese J Obstetr Gynecol 2016; 55(4): 525–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Miad K, Khan S, Sizear M, et al. Socioeconomic status & health seeking behavior of rural people: a cross-sectional study in Fatikchhari, Chittagong. MOJ Public Health 2016; 4(4): 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sanjoy S, Ahsan G, Nabi H, et al. Occupational factors and low back pain: a cross-sectional study of Bangladeshi female nurses. BMC Res Notes 2017; 10: 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karahan A, Kav S, Abbasoglu A, et al. Low back pain: prevalence and associated risk factors among hospital staff. J Adv Nurs 2009; 65(3): 516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abbas M, Zaid L, Fiala L, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among nurses in four tertiary care hospitals at King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh, KSA. Med J Cairo Univ 2010; 78(2): 219–223. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Janowski K, Steuden S, Kuryłowicz J. Factors accounting for psychosocial functioning in patients with low back pain. Eur Spine J 2010; 19(4): 613–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Terzi R, Altın F. The prevalence of low back pain in hospital staff and its relationship with chronic fatigue syndrome and occupational factors. Agri 2015; 27(3): 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ibrahim A, Nabil J, Mona A, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain among health care workers in southwestern Saudi Arabia. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019; 20: 56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bin Homaid M, Abdelmoety D, Alshareef W, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among operation room staff at a Tertiary Care Center, Makkah, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Ann Occup Environ Med 2016; 28: 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deng G, Zhang Y, Cai H, et al. Effects of physical factors on neck or shoulder pain and low back pain of adolescents. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2014; 94(43): 3411–3415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wedderkopp N, Kjaer P, Hestbaek L, et al. High-level physical activity in childhood seems to protect against low back pain in early adolescence. Spine J 2009; 9(2): 134–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. O’Sullivan P, Smith A, Beales D, et al. Association of biopsychosocial factors with degree of slump in sitting posture and self-report of back pain in adolescents: a cross-sectional study. Phys Ther 2011; 91(4): 470–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Johnson E, Edward E. Prevalence and risk factors of low back pain among workers in a health facility in South —South Nigeria. Br J Med Medical Res 2016; 11(8): 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Munyao DK, Meng’anyi LW. Factors contributing to back pain among nurses in a maternity ward at a level 5 hospital, Kenya. Int J Nurs Sci 2020; 10(2): 33–38. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Dlungwane T, Voce A, Knight S. Prevalence and factors associated with low back pain among nurses at a regional hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Health SA 2014; 23: 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]