Abstract

The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) produced by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a highly contagious infectious disease. In addition to typical flu-like symptoms, COVID-19 can also cause extrapulmonary spread and systemic inflammation, potentially causing multiorgan dysfunction, including thyroid dysfunction. Thyroid function changes in patients with COVID-19 have been widely reported, but the results are inconsistent. Based on available data, SARS-CoV-2 infection can lead to changes in thyroid function, and the degree of thyroid function changes was positively correlated with the severity of COVID-19, which involved multiple potential mechanisms. In contrast, current evidence was insufficient to prove that thyroid function changes could induce the progression of COVID-19 clinical deterioration.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Thyroid function change, Interaction

Introduction

The global pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is the most severe and overwhelming health crisis in one century. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection often induces systemic inflammation, which is associated with abnormal immune inflammatory responses to the virus and likely involves the coagulation, cytokine and complement systems; therefore, SARS-CoV-2 can also lead to extrapulmonary spread and multiorgan involvement, including thyroid involvement. Based on the available clinical data, patients with COVID-19 may be complicated with thyroid function changes, and serum thyroid hormone can in turn reflect the severity or mortality of COVID-19. However, the causal relationship between thyroid function changes and COVID-19 severity is still unclear. In this viewpoint, we try to discuss this topic from the two dimensions of causality.

COVID-19 results in thyroid function changes and are associated with disease severity

Changes in thyroid function are common in patients with COVID-19. In early 2020, a retrospective study [1] reported that COVID-19 patients had significantly lower serum TSH and TT3 levels than both healthy controls and patients affected by non-COVID-19 pneumonia, suggesting a specific role of COVID-19 in thyroid function alteration. To date, with the spread of COVID-19 worldwide, an increasing number of studies [1–10] have reported altered thyroid function after COVID-19 diagnoses. Based on the accumulated evidence, the most common was a marked decrease in TSH or FT3 with increasing COVID-19 severity [1–7], and a lower level of TSH or FT3 has also been observed in nonsurvivor patients [8, 9]. In addition, some studies [4, 10] also reported a lower FT4 level in patients with severe COVID-19, indicating nonthyroidal illness syndrome (NTIS). Nonetheless, it is worth mentioning that thyroid dysfunction occurred in only a handful of patients; most thyroid function changes were within biochemically euthyroid, and most could return to normal without any specific treatment. Although there were more or less certain thyroid function parameter alterations, whether rising or falling, that occurred after COVID-19 and were significantly related to the severity of COVID-19, these results are inconsistent. Recently, a meta-analysis evaluated the association between COVID-19 and thyroid-related hormones, including almost the most comprehensive related research articles in the field [11]. In total, 3609 hospitalized COVID-19 patients were included, and thyroid-related hormone abnormalities were common in patients with severe COVID-19. Patients with severe COVID-19 had lower levels of TSH and FT3 than patients with nonsevere COVID-19, while the difference in FT4 levels was not significant between the two groups. Similar results were also observed when grouping by survivors and nonsurvivors. However, the high heterogeneity of the included articles in the above analyses made it difficult to provide reliable information for further analysis [11].

The other thyroid disorders secondary to COVID-19, including subacute thyroiditis (SAT), Graves’ disease (GD) and Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (HT), are mainly presented in the form of case reports or case series [12–15], so that the quality of published data of were relatively poor [16]. These diseases are mainly characterized by transient hyperthyroidism, accompanied by changes in thyroid-related antibodies. Although hyperthyroidism may foster worse clinical progression, it is difficult to evaluate the impact of these thyroid disorders on the prognosis of COVID-19 through limited case reports. Meanwhile, taking SAT as an example, this thyroid disorder was only sporadic reports in the large infected population, so the observer bias caused by excessive attention to pneumonia should be vigilant, and the role of COVID-19 in inducing SAT might have been overestimated [13].

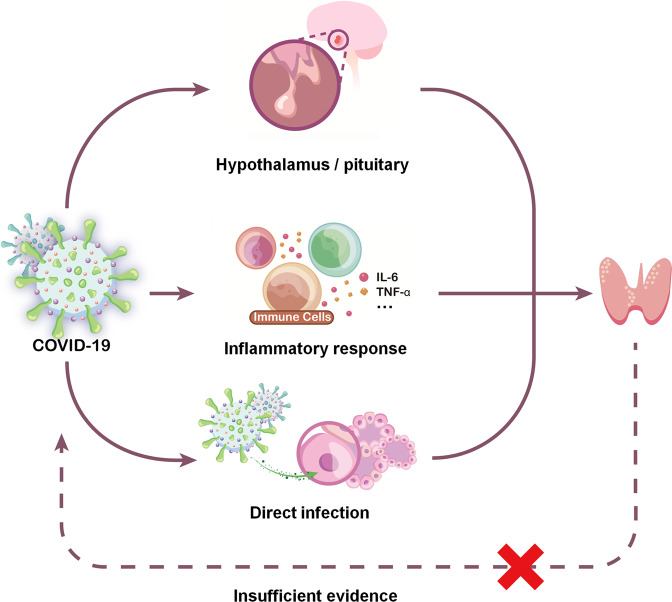

The etiology and pathogenesis of thyroid function change after COVID-19 involves complex cellular and molecular signaling mechanisms. In general, it mainly includes the following three points: direct infiltration, indirect influence through multiple inflammatory factors, and induction of hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis changes (Fig. 1). Both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 use angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) combined with transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2) as the key molecular complex to enter and infect host cells [17]. ACE2 and TMPRSS2 expression levels were found to be high in the thyroid [18], and the ACE-2 mRNA was also identified in thyroid follicular cells [19], suggesting that the thyroid may be a potential target for SARS-CoV-2 entry. However, there seems to be no evidence of SARS-CoV-2 expression in thyroid tissue. Although chronic lymphocytic infiltration in the interstitium or follicular epithelial cell disruption have been noted in some COVID-19 patients [20, 21], more histopathological findings are needed for further confirmation. Thyroid dysfunction after COVID-19 may also be mediated by a cytokine storm triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Direct evidence is that the thyroid dysfunction level is negatively correlated with multiple inflammatory factors, such as CRP, IL-6 ESR, and TNF-α [3, 5, 9]. Immune activation accompanied by triggering of proinflammatory responses is a classic process after SARS infection, and there is a significant correlation between inflammatory cytokines and thyroid function [22]. Lymphocyte infiltration was found in the interstitium of thyroid follicular epithelial cells [20, 21], suggesting a potential inflammatory response activity. One interesting finding is that ACE-2 mRNA levels in thyroid cells could be facilitated by pro-inflammatory cytokines in vitro; suggesting the elevated level of inflammatory cytokines may promote the entering of the virus in cells and thus influence the degree of severity of COVID-19 [23]. Another hypothesis is that dysfunction of the HPT axis causes a diminished level of serum TSH in patients with SARS-CoV-2, thus leading to thyroid dysfunction. Edema and neuronal degeneration along with the SARS-CoV-1 genome have been noted in the hypothalamus, suggesting that these regions may be potential targets of the virus [24]. Although there is no direct evidence of direct damage to the pituitary or hypothalamus after SARS-CoV-2 infection, central endocrine system disorders are still widely reported [12]. Central hypothyroidism was reported in some patients and was found to be associated with the severity of prognosis in COVID-19 [1, 25].

Fig. 1.

Potential mechanisms causing thyroid function changes with the severity of COVID-19

Together, current evidence shows that COVID-19 can lead to changes in thyroid function, and the degree of change increases with the severity of COVID-19. However, given that most studies are retrospective and do not well control for confounding factors at baseline, the reliability of the results is greatly limited. To date, there have been few studies on the relationship between thyroid function and COVID-19. More high-quality prospective studies with large sample sizes may help better answer this question.

Can thyroid function change worsen the prognosis of COVID‑19?

Because most previous studies excluded patients with preexisting thyroid dysfunction or thyroid disease, available evidence could only indicate that COVID-19 can lead to thyroid function change and correlate with the severity of COVID-19, while whether serum thyroid hormone impacts the severity or mortality of COVID-19 in turn is hard to explain. As mentioned above, patients with critical COVID-19 had lower levels of FT3 or TSH than patients with noncritical COVID-19 [6, 9]. These results seem to suggest that thyroid function at admission could predict the progression of COVID-19, but there are still several key points that need to be further explained. First, patients included in the study already had different severities of COVID-19 at the time of admission. For example, in the prospective study from Beltrao FEL et al. [9], the severity of COVID-19 was stratified within 48 h after admission, which was consistent with the measurement time of thyroid function. Hence, it is difficult to judge whether the patient’s thyroid function level at admission is original or has been affected by COVID-19 before admission. Second, most studies only included and analyzed the baseline thyroid function level at admission and lacked the changes in thyroid function with the progression of COVID-19 during follow-up. This lack of information was important to dynamically evaluate the relationship between thyroid function changes and COVID-19 severity.

Since measuring thyroid function after the diagnosis of COVID-19 makes it difficult to determine the causal relationship between the two, the analysis of pre-existing thyroid dysfunction before COVID-19 seems to better explain whether the change in thyroid function can impact the prognosis of COVID-19, but such studies are extremely rare. Limited evidence indicates that hypothyroidism is not associated with an increased risk of COVID-19-related hospitalization or a worse outcome [26], and treatment for thyroid dysfunction, whether pre-existing hypo- or hyperthyroidism, does not influence the prognosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection [27]. A systematic review from Trimboli P and colleagues also indicated that having a thyroid disease does not increase the risk for SARS-CoV-2 infection [28]. Meanwhile, NTIS may be able to explain this confusion in another way. NTIS typically occurs in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICUs) and is closely associated with the disease condition and prognosis. NTIS has also been reported with different incidences in COVID-19 patients and was confirmed to be associated with multiple COVID-19-related adverse events, including prolonged hospital stay, clinical deterioration, and even death [2, 5]. Since patients with NTIS are often characterized by normal or low serum TSH concentrations and low T3 concentrations [29], could thyroid hormone therapy reverse the negative clinical effects related to NITS? The available evidence is regrettable: NTIS is more often considered an adaptive response to reduced tissue metabolism during systemic illnesses, and the use of thyroxine for patients with NTIS did not produce additional benefits [29, 30]. These results seem to suggest that thyroid function changes are not the cause of COVID-19 clinical deterioration.

Conclusion

Patients with COVID-19 are often complicated with thyroid function changes, especially a decrease in TSH and FT3. Based on available evidence, thyroid function changes are directly or indirectly affected by COVID-19, while whether serum thyroid hormone impacts the severity or mortality of COVID-19 in turn is hard to conclude. Further studies are necessary to confirm this causal relationship.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (82173245), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020YFS0208), and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020YJ0237).

Author contributors

W.J.C: literature retrieval and data collection, and drafting of the manuscript; J.Y.L.: study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript. Z.H.L.: study concept and design, critical revision of the manuscript, and study supervision. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation (82173245), Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020YFS0208), and Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2020YJ0237).

Abbreviations

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- SARS-CoV-2

severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- NTIS

nonthyroidal illness syndrome

- SAT

subacute thyroiditis

- GD

Graves’ disease

- HT

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

- HPT

hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid

- ACE2

angiotensin-converting enzyme 2

- TMPRSS2

transmembrane protease serine 2

- ICUs

intensive care units

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jianyong Lei, Email: leijianyong@scu.edu.cn.

Zhihui Li, Email: rockoliver@vip.sina.com.

References

- 1.M. Chen., W.B. Zhou, W.W. Xu. Thyroid Function Analysis in 50 Patients with COVID-19: A Retrospective Study. Thyroid. 2020. 10.1089/thy.2020.0363 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Baldelli R, Nicastri E, Petrosillo N, Marchioni L, Gubbiotti A, Sperduti I, et al. Thyroid dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021;44(12):2735–9. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01599-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gao W, Guo W, Guo Y, Shi M, Dong G, Wang G, et al. Thyroid hormone concentrations in severely or critically ill patients with COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021;44(5):1031–40. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01460-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guven M, Gultekin H. The prognostic impact of thyroid disorders on the clinical severity of COVID-19: Results of single-centre pandemic hospital. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75(6):e14129. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lui DTW, Lee CH, Chow WS, Lee ACH, Tam AR, Fong CHY, et al. Thyroid Dysfunction in Relation to Immune Profile, Disease Status, and Outcome in 191 Patients with COVID-19. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021;106(2):e926–e35. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgaa813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lui DTW, Lee CH, Chow WS, Lee ACH, Tam AR, Fong CHY, et al. Role of non-thyroidal illness syndrome in predicting adverse outcomes in COVID-19 patients predominantly of mild-to-moderate severity. Clin. Endocrinol. 2021;95(3):469–77. doi: 10.1111/cen.14476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.C. Sparano C., E. Zago, A. Morettini, C. Nozzoli, D. Yannas, V. Adornato, et al. Euthyroid sick syndrome as an early surrogate marker of poor outcome in mild SARS-CoV-2 disease. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021. 10.1007/s40618-021-01714-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Chen T, Wu D, Chen H, Yan W, Yang D, Chen G, et al. Clinical characteristics of 113 deceased patients with coronavirus disease 2019: retrospective study. Bmj. 2020;368:m1091. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beltrao FEL, Beltrao DCA, Carvalhal G, Beltrao FEL, Brito ADS, Capistrano K, et al. Thyroid Hormone Levels During Hospital Admission Inform Disease Severity and Mortality in COVID-19 Patients. Thyroid. 2021;31(11):1639–49. doi: 10.1089/thy.2021.0225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.M.A. Ballesteros Vizoso, A.F. Castilla, A. Barcelo, J.M. Raurich, P. Argente Del Castillo, D. Morell-Garcia, et al. Thyroid Disfunction in Critically Ill COVID-19 Patients. Relationship with In-Hospital Mortality. J. Clin. Med. 10, (2021). 10.3390/jcm10215057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Chen Y, Li X, Dai Y, Zhang J. The Association Between COVID-19 and Thyroxine Levels: A Meta-Analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2021;12:779692. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.779692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.G. Lisco, A. De Tullio, A. Stragapede, A.G. Solimando, F. Albanese, M. Capobianco, et al. COVID-19 and the Endocrine System: A Comprehensive Review on the Theme. J. Clin. Med. 10(13), (2021). 10.3390/jcm10132920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Trimboli P, Camponovo C, Franscella S, Bernasconi E, Buetti N. Subacute Thyroiditis during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Searching for a Clinical Association with SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Endocrinol. 2021;2021:5588592. doi: 10.1155/2021/5588592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pirola I, Gandossi E, Rotondi M, Marini F, Cristiano A, Chiovato L, et al. Incidence of De Quervain’s thyroiditis during the COVID-19 pandemic in an area heavily affected by Sars-CoV-2 infection. Endocrine. 2021;74(2):215–8. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02841-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.W. Chen, Y. Tian, Z. Li, J. Zhu, T. Wei, J. Lei. Potential Interaction Between SARS-CoV-2 and Thyroid: A Review. Endocrinology. 162(3), (2021). 10.1210/endocr/bqab004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Trimboli P, Cappelli C, Croce L, Scappaticcio L, Chiovato L, Rotondi M. COVID-19-Associated Subacute Thyroiditis: Evidence-Based Data From a Systematic Review. Front. Endocrinol. 2021;12:707726. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.707726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Kruger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–80 e8. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li MY, Li L, Zhang Y, Wang XS. Expression of the SARS-CoV-2 cell receptor gene ACE2 in a wide variety of human tissues. Infect. Dis. Poverty. 2020;9(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s40249-020-00662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotondi M, Coperchini F, Ricci G, Denegri M, Croce L, Ngnitejeu ST, et al. Detection of SARS-COV-2 receptor ACE-2 mRNA in thyroid cells: a clue for COVID-19-related subacute thyroiditis. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021;44(5):1085–90. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01436-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanley B, Naresh KN, Roufosse C, Nicholson AG, Weir J, Cooke GS, et al. Histopathological findings and viral tropism in UK patients with severe fatal COVID-19: a post-mortem study. Lancet Microbe. 2020;1(6):e245–e53. doi: 10.1016/S2666-5247(20)30115-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.X.H. Yao, T.Y. Li, Z.C. He, Y.F. Ping, H.W. Liu, S.C. Yu et al. [A pathological report of three COVID-19 cases by minimal invasive autopsies]. Zhonghua bing li xue za zhi = Chinese journal of pathology 49(5), 411–7 (2020). 10.3760/cma.j.cn112151-20200312-00193 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Croce L, Gangemi D, Ancona G, Liboa F, Bendotti G, Minelli L, et al. The cytokine storm and thyroid hormone changes in COVID-19. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2021;44(5):891–904. doi: 10.1007/s40618-021-01506-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coperchini F, Ricci G, Croce L, Denegri M, Ruggiero R, Villani L, et al. Modulation of ACE-2 mRNA by inflammatory cytokines in human thyroid cells: a pilot study. Endocrine. 2021;74(3):638–45. doi: 10.1007/s12020-021-02807-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leow MK, Kwek DS, Ng AW, Ong KC, Kaw GJ, Lee LS. Hypocortisolism in survivors of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Clin. Endocrinol. 2005;63(2):197–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng J, Cui Z, Shi N, Tian S, Chen T, Zhong X, et al. Suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid axis is associated with the severity of prognosis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2021;21(1):228. doi: 10.1186/s12902-021-00896-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Gerwen M, Alsen M, Little C, Barlow J, Naymagon L, Tremblay D, et al. Outcomes of Patients With Hypothyroidism and COVID-19: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Front. Endocrinol. 2020;11:565. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2020.00565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brix TH, Hegedus L, Hallas J, Lund LC. Risk and course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients treated for hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(4):197–9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trimboli P, Camponovo C, Scappaticcio L, Bellastella G, Piccardo A, Rotondi M. Thyroid sequelae of COVID-19: a systematic review of reviews. Rev. Endocr. Metab. Disord. 2021;22(2):485–91. doi: 10.1007/s11154-021-09653-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van den Berghe G. Non-thyroidal illness in the ICU: a syndrome with different faces. Thyroid. 2014;24(10):1456–65. doi: 10.1089/thy.2014.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brent GA, Hershman JM. Thyroxine therapy in patients with severe nonthyroidal illnesses and low serum thyroxine concentration. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1986;63(1):1–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem-63-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]