Abstract

In their effort to prevent the spread of infections, retirement homes have been forced to limit physical interaction between residents and the outside world and to drastically reduce their residents’ activities, decisions which are likely to increase loneliness in residents. To investigate this issue, we evaluated loneliness in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) living in retirement homes in France during the COVID-19 crisis. The study included 63 participants with mild AD. Participants were invited to complete the following statement “During the social distancing, I feel” with one of the three options: not at all alone, somewhat alone, or very alone. Most of the participants answered “somewhat alone”, suggesting a significant level of loneliness during the crisis. While it serves to prevent infections, social distancing in retirement homes is likely to result in significant loneliness in residents. Because loneliness may increase cognitive decline in AD, it to pressing to prepare social programs/activities that promote contact between residents of retirement homes and the outside world as soon as the confinement is lifted.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, COVID-19, Loneliness, Retirement homes

Introduction

To cope with COVID-19 and limit its spread among residents, retirement homes in France have been obliged to prohibit physical contact between residents and families and friends and, in several cases, even between residents or between residents and caregivers. While they serve to prevent infections, these measures are forcing retirement homes to separate residents physically from the outside world and to drastically reduce their activities. Because these decisions are likely to come at a cost to residents and their wellbeing and mental health, we investigated whether social distancing increases loneliness in patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD) who live in retirement homes.

A brief definition of loneliness is required before discussing research on loneliness in AD. Loneliness can be generally defined as a subjective state involving distressing, depressing, and detached feelings that people experience due to emptiness in their life [1]. While associated with the experience of emptiness and social isolation, loneliness can also mirror dissatisfaction with available relationships and social contacts [1]. Loneliness, as associated with social isolation, can be a risk factor for dementia [2]. A large body of research has demonstrated that loneliness and social isolation in normal aging may contribute to increased risk of dementia [3], [4], [5]. On the other hand, social integration in normal aging may contribute to reduced rates of dementia [6], [7]. Having an extended social network, high frequency of contacts, and adequate social support can be protective factors against the risk of dementia [2].

The relationship between loneliness and AD was evaluated in a longitudinal study by Wilson, Krueger [8] who assessed loneliness in a sample of 823 older adults free of cognitive decline. During follow-up, they observed that the incidence of AD was more than doubled in participants with high loneliness at baseline compared with those who did not experience it. Interestingly, controlling for indicators of social isolation did not even affect the results. In other words, loneliness, more than social isolation, was associated with AD during the follow-up. Similarly, Holwerda, Deeg [9] assessed loneliness and social isolation in a sample of 2173 older adults free of cognitive decline. Follow-up results demonstrated that participants who experienced loneliness at baseline were 1.64 times more likely to develop AD compared with those who did not experience it. These findings remained even after controlling for demographic, somatic and psychiatric factors. Interestingly, Holwerda, Deeg [9] reported that loneliness rather than social isolation was associated with AD. Loneliness, as a risk factor for AD, was also reported by Rafnsson, Orrell [10], who assessed loneliness and social isolation in a sample of 6.677 of older adults free of cognitive decline. Follow-up results demonstrated that later AD was associated with loneliness and having few close social relationships at baseline. Together, research has demonstrated how loneliness in normal aging can be associated with later AD.

Besides being a potential risk factor for AD, significant loneliness may be observed in patients with AD. Because of their decreased cognitive and functional abilities, they may experience significant difficulty in communicating, resulting in increased loneliness. This loneliness can even increase in patients with AD living in retirement homes during the COVID-19 crisis. Although retirement homes are used to dealing with the cognitive and functional characteristics of AD, COVID-19 has heavily modified the way they function. To cope with the crisis, retirement homes in France have significantly restricted visits since 15 March 2020. All activities considered as non-essential have been suspended, including restricting access to non-essential personnel (e.g., hairdressers), group activities, and even communal dining. Despite the efforts of caregivers to provide the best care possible, they have had to struggle with an increased workload (e.g., increased vigilance for potential fever and respiratory symptoms, increased requirements to provide postmortem care) and deal with shortages in equipment and supplies, such as sanitizers, gloves and facemasks. These challenges may have significantly reduced the social interaction between caregivers and patients, thereby exacerbating the feeling of loneliness in patients.

To summarize, we evaluated loneliness in patients with AD living in retirement homes in France during the COVID-19 crisis. We instructed caregivers to ask patients with AD to rate their loneliness. We expected that patients with AD would declare high levels of loneliness.

Method

Participants

The study included 63 participants with a clinical diagnosis of probable AD (39 women; M age = 70.13 years, SD = 5.32; M years of formal education = 9.14, SD = 2.49) who participated voluntarily in the study. They were recruited from retirement homes in France. They were recruited by contacting professional colleagues (19 psychologists, physicians or nurses) who work in retirement homes in France, either directly or through social networks (e.g., Facebook groups of geriatric caregivers). These on-site caregivers agreed to obtain consent from eligible participants, provide historical information about them and administer the study procedures. On-site colleagues were asked to verify in the medical records that a diagnosis of probable AD had been made by a neurologist or geriatrician according to the clinical criteria of the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer's Association criteria for probable Alzheimer's disease [11], and that the patients had been assessed with the Mini Mental State Exam [12] within three months before the study to provide a recent assessment of their cognitive status. Due to their increased workload during the crisis, we did not ask on-site caregivers to repeat administration of the Mini Mental State Exam or perform any other clinical test. We selected a score of 21/30 points or higher as an inclusion criterion (M = 22.01, SD = 1.01) to limit enrollment of patients with mild AD. We did not include patients with a score < 21 points on the Mini Mental State Exam because our study required some introspection into loneliness.

Procedures

On-site caregivers provided participants with the following instruction: “We would like to evaluate the psychological effects of the social distancing measures to cope with the COVID-19 crisis. We would like you to complete the following statement: “During social distancing, I feel…” with one of these three options: not at all alone, somewhat alone, or very alone”. Note that the question was provided orally by on-site caregivers and answers were also provided orally by patients to minimize the risk of contamination by exchanging paper and pencil materials. We invited caregivers to note the answer and provide us with the answer by phone or email. The procedures were conducted following the latest Declaration of Helsinki. Participation was voluntary and participants were invited to provide their consent prior to answer the loneliness statement. The collected data was anonymized and secured to avoid any breach of agreed confidentiality and anonymity.

Results

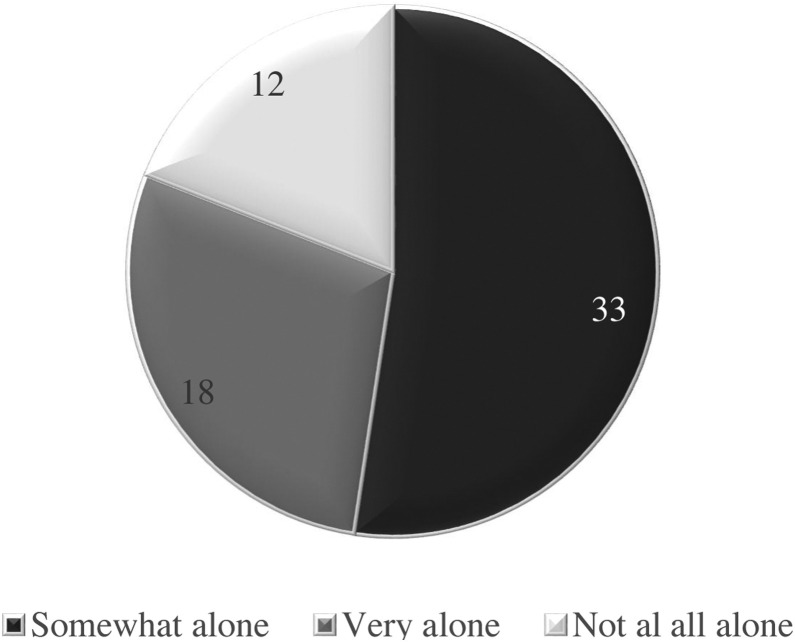

The total number of answers was 63 (i.e., one answer per participant = 63). Using χ2 tests, we compared the number of “not at all alone”, “somewhat alone”, and “very alone” answers (as illustrated in Fig. 1 ). Analysis demonstrated a significant difference between the numbers of the three answers [χ2 (2, n = 63) = 11.14, P = 0.004, Cohen's d=0.93]. Analysis also demonstrated more “somewhat alone” than “very alone” [χ2 (1, n = 51) = 4.41, P=0.036, Cohen's d=0.61] or “not at all alone” answers [χ2 (1, n = 45) = 9.80, P = 0.002, Cohen's d=0.98]. No significant differences were observed between the number of “very alone” and “not at all alone” answers [χ2 (1, n = 30) = 1.20, P = 0.273, Cohen's d = 0.41].

Fig. 1.

Number of three categories of answers as provided by participants to describe their loneliness during COVID-19 crisis (one answer for each of the 63 participants).

Discussion

This is the first empirical assessment of loneliness as experienced by patients with AD living in retirement homes during the COVID-19 crisis. To the statement “During the social distancing, I feel…”, most of the participants answered “somewhat alone”, suggesting a significant level of loneliness.

The loneliness experienced by our participants can be attributed to the social distancing measures and drastic changes in the daily life of the residents during the crisis. Retirement homes in France, other European and North American countries are currently restricting visits. Non-essential activities and services are also being restricted, including basic social activities such as communal dining. In some cases, residents are asked not to leave their rooms and, when in wards, to keep a safe distance from other residents to avoid contracting the virus. They are not yet allowed to have any physical contact with their family members and friends. While these restrictions may be deemed necessary, they are likely to come at a cost to residents in retirement homes and their wellbeing (i.e., in loneliness). While many residents are keeping contact with family members via virtual communication tools, this technology is not yet available for all residents in retirement homes. Many patients with AD are also unfamiliar with this technology and, owing to cognitive decline, may have trouble in learning about it. For instance, owing to anterograde amnesia, patients with AD may experience significant difficulty in retaining information about how to use virtual communication tools. Another factor that may contribute to the loneliness of residents is the decreased contact with caregivers who, despite their efforts to provide the best care, have been dealing with an increased workload, shortages in equipment and supplies, and increased postmortem care.

One of the consequences of this loneliness may be increased cognitive decline. Together with a reduction in the number and quality of social interactions, loneliness results in diminished cognitive stimulation, which itself leads to cognitive decline [13]. This assumption is supported by the well-known Nun Study, demonstrating how social activities and social engagement may stimulate cognition [14]. Loneliness may lead to cognitive decline in patients with AD by decreasing their neural reserve through decreased dendritic arborization in the hippocampal and prefrontal areas, resulting in cognitive impairment [15]. The negative effects of loneliness on cognitive functioning in AD can also be attributed to a stress-related mechanism. Lonely patients may experience heightened exposure to stress because loneliness in general is associated with elevated cortisol in everyday life, and with heightened inflammatory cytokine responses to acute stress [16]. These stress responses have been associated with neural damage in the frontal and limbic regions, which in turn impairs cognitive function [17]. According to Sapolsky [18], hypersecretion of the glucocorticoids, as occurs in stress responses, causes accelerated hippocampal degeneration and leads to cognitive decline. Briefly, loneliness can exacerbate cognitive decline in patients with AD.

While the study offers the first empirical assessment of loneliness in residents of retirement homes during the COVID-19 crisis, a potential shortcoming is the single-question assessment. While the study was designed to fit the constraints of social distancing and not to overload the caregivers who administered the protocol, an assessment based on a single question does not provide an in-depth view of loneliness, as would be the case if scales such as the UCLA loneliness scale were to be used [19]. Note, however, that loneliness in patients with AD is typically assessed with only a few questions. For instance, in their longitudinal study, Wilson, Krueger [8] assessed loneliness with five items, and Holwerda, Deeg [9] even used only one question.

By providing the first empirical assessment of loneliness of residents in retirement homes during the COVID-19 crisis, this study draws the attention of researchers, clinicians and even decision-makers to the need to consider the effects of loneliness on patients. As emphasized herein, loneliness can exacerbate cognitive decline in patients with AD. It is therefore pressing to set up social programs/activities that maintain contact between residents of retirement homes and the outside world as soon as the confinement is lifted.

Funding statement

The first author was supported by the LABEX (excellence laboratory, program investment for the future) DISTALZ (Development of Innovative Strategies for a Transdisciplinary Approach to Alzheimer Disease).

Disclosure of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Ethics

This study was designed and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the LPCL ethical board (2020-017). Participants provided their verbal consent to participate and were able to withdraw whenever they wished.

References

- 1.Killeen C. Loneliness: an epidemic in modern society. J Adv Nurs. 1998;28(4):762–770. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Penninkilampi R., Casey A.-N., Singh M.F., et al. The association between social engagement, loneliness, and risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;66:1619–1633. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crooks V.C., Lubben J., Petitti D.B., et al. Social network, cognitive function, and dementia incidence among elderly women. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1221–1227. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saczynski J.S., Pfeifer L.A., Masaki K., et al. The effect of social engagement on incident dementia: the Honolulu-Asia aging study. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(5):433–440. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stoykova R., Matharan F., Dartigues J.F., et al. Impact of social network on cognitive performances and age-related cognitive decline across a 20-year follow-up. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(9):1405–1412. doi: 10.1017/S1041610211001165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnes L.L., Mendes de Leon C.F., Wilson R.S., et al. Social resources and cognitive decline in a population of older African Americans and whites. Neurology. 2004;63(12):2322–2326. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000147473.04043.b3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ertel K.A., Glymour M.M., Berkman L.F. Effects of social integration on preserving memory function in a nationally representative US elderly population. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(7):1215–1220. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.113654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson R.S., Krueger K.R., Arnold S.E., et al. Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2007;64(2):234–240. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holwerda T.J., Deeg D.J.H., Beekman A.T.F., et al. Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL) J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85(2):135–142. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2012-302755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rafnsson S.B., Orrell M., d’Orsi E., et al. Loneliness, social integration, and incident dementia over 6 years: prospective findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. J Gerontol. 2017;75(1):114–124. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbx087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McKhann G., Knopman D.S., Chertkow H., et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y) 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folstein M.F., Folstein S.E., McHugh P.R. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourassa K.J., Memel M., Woolverton C., et al. Social participation predicts cognitive functioning in aging adults over time: comparisons with physical health, depression, and physical activity. Aging Ment Health. 2017;21(2):133–146. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1081152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snowdon D.A., Greiner L.H., Mortimer J.A., et al. Brain infarction and the clinical expression of Alzheimer disease. The Nun Study. JAMA. 1997;277(10):813–817. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson R.S., Barnes L.L., Bennett D.A., et al. Proneness to psychological distress and risk of Alzheimer disease in a biracial community. Neurology. 2005;64(2):380–382. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000149525.53525.E7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cacioppo S., Grippo A.J., London S., et al. Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2015;10(2):238–249. doi: 10.1177/1745691615570616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McEwen B.S. Physiology and neurobiology of stress and adaptation: central role of the brain. Physiol Rev. 2007;87(3):873–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sapolsky R.M. Glucocorticoids, stress, and their adverse neurological effects: relevance to aging. Exp Gerontol. 1999;34(6):721–732. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00047-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Russell D.W. UCLA Loneliness Scale (Version 3): reliability, validity, and factor structure. J Pers Assess. 1996;66(1):20–40. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]