Abstract

Objective

To determine if patients with post‐polio syndrome (PPS) show spinal cord gray matter (SCGM) atrophy and to assess associations between SCGM atrophy, muscle strength and patient‐reported functional decline.

Methods

Twenty patients diagnosed with PPS (March of Dimes criteria) and 20 age‐ and sex‐matched healthy controls (HC) underwent 3T axial 2D‐rAMIRA magnetic resonance imaging at the intervertebral disc levels C2/C3–C6/C7, T9/T10 and the lumbar enlargement level (T max) (0.5 × 0.5 mm2 in‐plane resolution). SCGM areas were segmented manually by two independent raters. Muscle strength, self‐reported fatigue, depression and pain measures were assessed.

Results

Post‐polio syndrome patients showed significantly and preferentially reduced SCGM areas at C2/C3 (p = 0.048), C3/C4 (p = 0.001), C4/C5 (p < 0.001), C5/C6 (p = 0.004) and T max (p = 0.041) compared to HC. SCGM areas were significantly associated with muscle strength in corresponding myotomes even after adjustment for fatigue, pain and depression. SCGM areaTmax together with age and sex explained 68% of ankle dorsiflexion strength variance. No associations were found with age at or time since infection. Patients reporting PPS‐related decline in arm function showed significant cervical SCGM atrophy compared to stable patients adjusted for initial disease severity.

Conclusions

Patients with PPS show significant SCGM atrophy that correlates with muscle strength and is associated with PPS‐related functional decline. Our findings suggest a secondary neurodegenerative process underlying SCGM atrophy in PPS that is not explained by aging or residua of the initial infection alone. Confirmation by longitudinal studies is needed. The described imaging methodology is promising for developing novel imaging surrogates for SCGM diseases.

Keywords: post‐polio syndrome, rAMIRA imaging, spinal cord gray matter atrophy, spinal cord gray matter imaging

Spinal cord gray matter atrophy is associated with functional decline in post‐polio syndrome.

INTRODUCTION

Acute poliomyelitis is caused by a central nervous system infection with the poliovirus. The lower motor neurons of the spinal cord (SC) anterior horn are mainly affected [1]. Neuronal damage is not evenly distributed, which leads to the classical clinical picture of flaccid, often asymmetric paralyses of one or more limbs with or without involvement of the respiratory or bulbar muscles [1, 2, 3]. The extent of histopathologically documented neuronal damage exceeds the clinically visible neurological deficits, with early pathological reports demonstrating 20% motor neuron reductions in clinically unaffected segments [4, 5]. Usually, full or partial recovery of function occurs [6]. After a clinically stable period of several years to decades, up to 85% of polio survivors [7] develop a complex of new muscular weakness and atrophy of previously affected, but also of previously unaffected muscles, muscular pain and fatigue, termed the post‐polio syndrome (PPS) [8]. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of PPS are not fully understood, and PPS as a distinct disease entity and its differentiation from normal aging continue to be debated.

Characterizing spinal cord gray matter (SCGM) and white matter (WM) in vivo by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is technically challenging due to the SC fine structure and artifacts from physiological motions and surrounding tissues [9]. Novel developments of MRI‐based techniques enable SCGM and WM quantitation in vivo [10, 11]. Studies in multiple sclerosis demonstrated close associations between cervical SCGM atrophy and clinical disability and progression [12, 13]. Latest advances in MRI sequence development allow an improved contrast between SCGM and WM, particularly in the lower thoracic cord, in feasibly short acquisition times using radially sampled averaged magnetization inversion recovery acquisitions (r‐AMIRA) imaging [14, 15].

Spinal cord gray matter areas have not been systematically investigated in patients with PPS, which as a rare, but presumed pure, lower motor neuron disorder can serve as a model for other neurodegenerative, genetic or autoimmune diseases affecting the SCGM.

The primary objectives of this study were to evaluate SCGM atrophy in patients with PPS in comparison to age‐ and sex‐matched healthy control subjects (HC) and to assess segment‐wise associations of SCGM atrophy with clinical metrics of disability.

Secondary objectives were to explore whether SCGM atrophy can also be detected in SC segments that remained asymptomatic at the time of initial infection and whether SCGM atrophy is more pronounced in regions with reported PPS‐related functional decline than in stable regions.

METHODS

Participants and setting

This was an explorative, prospective, single‐center, observational case–control study conducted at the University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland. Detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria are described in Table 1. A total of 32 patients aged >18 years and diagnosed with PPS who had presented previously at least once to either the neuromuscular clinic of the University Hospital Basel or University Children's Hospital Basel for neurological evaluation were initially considered for study participation. These patients were evaluated regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1). Two patients did not fulfil the March of Dimes criteria, two had contraindications against MRI, and eight did not want to participate. The remaining 20 patients were recruited together with 20 age‐ and sex‐matched HC. The study was approved by the Northwest and Central Switzerland Ethics Committee and registered at ClincialTrials.gov (NCT03561623). All participants provided written informed consent.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for patients with post‐polio syndrome

| Inclusion criteria |

| Patients older than 18 years |

| Prior paralytic poliomyelitis with evidence of motor neuron loss confirmed by history of the acute paralytic illness, signs of residual weakness and atrophy of muscles on neuromuscular examination, and signs of motor neuron loss |

| A period of partial or complete functional recovery after acute paralytic poliomyelitis, followed by an interval (usually 15 years or more) of stable neuromuscular function |

| Slowly progressive and persistent new muscle weakness or decreased endurance, with or without generalized fatigue, muscle atrophy, or muscle and joint pain; symptoms that persist for at least a year |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Contraindications against magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) |

| Known or suspected malignancy |

| Other chronic disease or clinically relevant limitation |

| Severe disease of the spine or spinal cord including severe spinal cord stenosis, known myelopathy or infarction, history of spinal or spinal cord injury or tumor, or other relevant spinal cord diseases interfering with the clinical/MRI examination |

Image acquisition

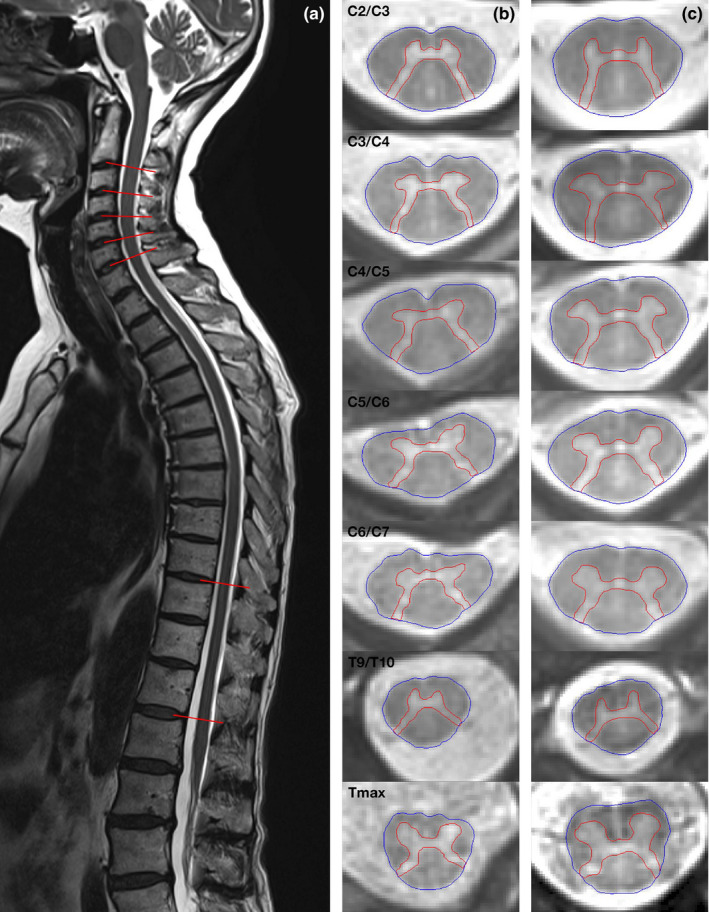

We examined all participants with the same 3T whole‐body MRI scanner at University Hospital Basel (Magnetom PRISMA, Siemens Healthineers) using a 64‐channel head and neck coil as well as the built‐in spine coil. Axial 2D rAMIRA images [14, 15] were acquired perpendicular to the SC (Figure 1) at intervertebral disc levels C2/C3–C6/C7 and T9/T10–T11/T12 and, in participants with low standing conus, also at T12/L1. To control for the anatomic variability of the conus position, the thoracic level with the largest total cross‐sectional area (TCA) between T10/T11 and T12/L1 was defined as T max. We used this level and the level T9/T10, which is located above the lumbar enlargement and showed less anatomic variability in previous studies [16], for further analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Axial 2D‐rAMIRA (averaged magnetization inversion recovery acquisitions) images obtained at the intervertebral disc levels perpendicular to the spinal cord (as highlighted on the sagittal T2‐weighted image of a healthy control person (a)). Axial 2D‐rAMIRA images of a patient with post‐polio syndrome (b) and an age‐ and sex‐matched healthy control person (c) from top to bottom: C2/3, C3/4, C4/5, C5/6, C6/7, T9/T10 and T max (in‐plane resolution 0.5 × 0.5 mm2) [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The utilized rAMIRA acquisition protocol was based on the “optimized rAMIRA protocol for the thoracic SC” presented in the initial methods paper [15]. Like the original, Cartesian sampling‐based AMIRA approach [14], the employed rAMIRA sequence consisted of an initial inversion recovery preparation followed by a time‐limited, cine‐like balanced steady‐state free precession (bSSFP) readout module. The readout acquired segmented k‐space data for five images simultaneously with the mean inversion times TIeff = 174, 239, 304, 368, 433 ms. These images were used separately for the automatic segmentation algorithm (Appendix S1) but also combined (i.e., averaged) to yield a signal‐to‐noise and contrast‐to‐noise improved image [14, 15].

Further rAMIRA acquisition parameters were: field of view (FOV) = 128 × 128 mm2, 512 readout samples (included 2× oversampling), 260 radial projections, 10 segments, isotropic in‐plane resolution 0.50 × 0.50 mm2, slice thickness 8 mm, TRbSSFP = 6.49 ms (“echo spacing”), TEbSSFP = 3.23 ms, excitation flip angle 50°, receiver bandwidth = 310 Hz/px, averages = 2.

The rAMIRA sequence used cardiac triggering to mitigate potential pulsation artifacts realized with a standard infrared finger clip. Thus, the overall TRrAMIRA of the rAMIRA sequence depended on the heart rate and was kept around 3 s. The same was true for the acquisition time: for instance, for a heartbeat of 60 beats per minute (bpm), the resulting acquisition time (TA) corresponded to TA =2:39 min per slice.

Furthermore, all participants received T2‐weighted turbo spin echo imaging covering the whole SC in sagittal and coronal slice orientation. These measurements were also used for properly aligning the rAMIRA acquisitions orthogonal to the SC. The corresponding sequence parameters were: (1) sagittal: FOV = 360 × 360 mm2, in‐plane resolution = 0.7 × 0.7 mm2, phase oversampling = 75%, 17 slices of thickness 3 mm, repetition time (TR) = 3400 ms, echo time (TE) = 102 ms, flow compensation along the read encoding direction, bandwidth = 260 Hz/px, flip angle = 150°, signal averaging = 2, TA = 4:17 min; (2) coronal: FOV = 450 × 450 mm2, in‐plane resolution = 1.4 × 1.4 mm2, phase oversampling = 20%, 17 slices of thickness 3 mm, TR = 3500 ms, TE = 95 ms, flow compensation along the read encoding direction, bandwidth = 260 Hz/px, flip angle = 160°, TA = 0:37 min.

Image analysis

First, we segmented TCAs semi‐automatically using the software JIM7 (www.xinapse.com). T max was identified for each participant. SCGM areas were segmented manually. Two trained, independent raters blinded to participant status performed the segmentations. Interrater reliability of the manual GM segmentations between the two independent raters was high at cervical levels and acceptable at thoracic levels with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC; two‐way random, absolute agreement): C2/C3: 0.981 (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.964–0.990); C3/C4: 0.975 (0.953–0.987); C4/C5: 0.984 (0.967–0.992); C5/C6: 0.981 (0.961–0.991); C6/C7: 0.988 (0.974–0.994); T9/T10: 0.986 (0.971–0.993); T max: 0.874 (0.748– 0.937).

Furthermore, SC data were analyzed using an automated segmentation method specifically developed for segmentation of rAMIRA images (for details and preliminary results see Appendix S1).

Clinical assessment

We obtained detailed, structured information about onset and symptoms during the acute infection, the stable interval and the PPS phase. We graded the initial infection severity (a) by the number of clinically affected regions reported by the patient (bulbar, upper limb, thoracic, lower limb) [17] as well as by (b) respiratory involvement. All participants received a structured clinical examination by an experienced neurologist, including muscle strength assessments of wrist extensors and ankle dorsiflexors by handheld dynamometry following the TRICALS protocol [18]. We measured neck flexion strength according to a pre‐specified protocol [19]. We selected these three muscle groups as their assessment by dynamometer is relatively reliable and was shown to correlate well with clinical metrics in other motor neuron diseases [20]. This approach allowed us to estimate motor neuron function in the SC segments C2–C3, C7 and L4–L5, respectively. Based on a post‐mortem study [21] and an in vivo MRI study in healthy individuals [10], these segments project to the respective intervertebral disc levels C2/C3, C5/C6 and T max.

Furthermore, the following patient‐reported outcomes (PRO) were assessed: The Fatigue Severity Scale (FSS) [22], the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) [23] and the Chronic Pain Grade Scale (GCPS) [24] to control for comorbidities with high prevalence in PPS [25] potentially interfering with the muscle strength assessments.

Statistical methods

Primary analyses

According to Kolmogorov–Smirnov and Shapiro–Wilk testing, SCGM area metrics were normally distributed. Pairwise comparisons of SCGM areas between patients with PPS and age‐ and sex‐matched HC were performed using Wilcoxon signed rank tests acknowledging the sample size.

Associations between SCGM areas at the intervertebral disc levels C2/C3, C5/C6 and T max with muscle strength in their corresponding myotome [10, 21], that is, strength of neck‐flexion, wrist extension and ankle dorsiflexion, respectively, along with demographic and PRO variables (fatigue, pain, depression levels) [22, 23, 24] were analyzed in patients using multivariable linear regression analysis. For each SC segment–muscle strength pair (1–3), we performed a step‐wise backward selection procedure using a starting model including the SCGM area at the given level along with all PRO variables with a Pearson correlation coefficient of |r| ≥ 0.2 in univariate analysis as predictor variables, as well as age and sex as fixed predictor variables with muscle strength at the respective corresponding myotome [10, 21] as outcome. The adjusted r 2 of the models 1–3 resulting from the backward selection procedures were reported.

Secondary explorative analyses

Regarding the secondary, exploratory objectives, subgroup analyses of cervical SCGM areas were performed using multivariable regression analysis with age and sex as covariates comparing: (a) patients with vs. without reported upper limb (UL) involvement during the acute infection vs. healthy controls and (b) patients with vs. without reported PPS‐related decline of UL function vs. healthy controls.

To assess the effects of disease severity of the initial infection, age at infection and time since infection on SCGM area, we included theses variables, respectively, to the multivariable models in additional sensitivity analyses. Given the exploratory nature of these secondary analyses in this rare disease, we report raw p values, explicitly not adjusted for multiple comparisons.

The statistical significance level was set to alpha <0.05. The statistical packages JMP Pro version 13 (2016; SAS Institute Inc.) and SPSS version 25.0 (2017; IBM Corp.) were used for the data analysis.

RESULTS

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants are summarized in Table 2. HC (mean age 66.3 years, SD 6.3; 8 women) showed similar age and sex distributions as patients with PPS (mean age 66.5 years, SD 4.7; 8 women). PPS manifested as new muscular weakness and/or atrophy in 11 patients (55%) and as new abnormal muscular fatigability in 2 patients (10%). Five patients (25%) reported an aggravation of persisting symptoms and 2 patients (10%) a reactivation of previously resolved symptoms. Four patients (20%) reported respiratory failure at the initial infection. Grading disease severity by the number of clinical regions involved during initial infection, 6, 6 and 8 patients reported 1, 2 and ≥3 involved regions, respectively.

TABLE 2.

Basic demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with post‐polio syndrome and healthy controls

| Demographic and clinical characteristics |

Patients with PPS (n = 20) |

HC (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 66.5 (4.7) | 66.3 (6.3) |

| Median (range) | 66.0 (57–76) | 66.0 (54–78) |

| Gender (M:F) | 12:8 | 12:8 |

| Mean age at polio infection (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.0 (3.4) | NA |

| Median (range) | 2.5 (0.25–10) | |

| Mean interval acute infection to PPS onset (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 44.4 (10.1) | NA |

| Median (range) | 43.5 (25–61) | |

| Regions involved at acute infection (n (%)) | ||

| 1 | 6 (30) | NA |

| 2 | 6 (30) | |

| >3 | 8 (40) | |

| Respiratory failure at initial infection (n (%)) | 5 (20) | NA |

| Fatigue a (Fatigue Severity Scale [22]) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 42.6 (13.7) | NA |

| Median (range) | 45 (22–62) | |

| Depression b (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [23]) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.9 (2.0) | NA |

| Median (range) | 2.5 (1–7) | |

| Chronic pain c (Chronic Pain Grading Scale [24]) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.3 (0.6) | NA |

| Median (range) | 1 (1–3) | |

Abbreviations: F, female; HC, healthy control; M, male; NA, not applicable; PPS, post‐polio syndrome; SD, standard deviation; range, minimum to maximum.

Fatigue Severity Scale: range 7–63, cut‐off for fatigue ≥36.

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale: range 0–21, cut‐off for depression ≥7.

Chronic Pain Grade Scale: range 1–3.

Generally, rAMIRA image quality was high. At the levels T9/T10 and T max, the two independent raters were not able to perform the manual GM segmentation due to motion artifacts in one participant, and due to severe scoliosis resulting in adverse signal reception in one further participant.

Main analyses

Table 3 shows the comparison of SCGM metrics of patients with PPS and HC. In the main analysis, we found significantly reduced SCGM areas in patients with PPS compared to age‐ and sex‐matched HC at the intervertebral disc levels close to the cervical and lumbar enlargements, namely C2/C3 (p = 0.048), C3/C4 (p = 0.001), C4/C5 (p < 0.001), C5/C6 (p = 0.004) and T max (p = 0.041) (Table 4). SCGM were maximally and preferentially reduced in the area of the cervical and lumbar enlargements (Appendix S2, Table S1).

TABLE 3.

Spinal cord gray matter metrics of patients with post‐polio syndrome (PPS) and healthy controls

| Gray matter area (mm2) at intervertebral disc level |

Patients with PPS (n = 20) |

HC (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| C2/C3 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 14.42 (2.26) | 15.49 (1.16) |

| Median (range) | 14.27 (10.47–20.17) | 15.38 (13.23–17.10) |

| C3/C4 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 16.27 (2.22) | 19.32 (1.73) |

| Median (range) | 15.9 (11.84–20.11) | 19.94 (15.08–21.76) |

| C4/C5 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 17.42 (2.05) | 20.70 (1.55) |

| Median (range) | 17.31 (14.21–21.91) | 20.92 (17.51–23.64) |

| C5/C6 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 16.97 (2.81) | 20.04 (2.6) |

| Median (range) | 16.6 (11.66–22.79) | 20.18 (14.6–25.1) |

| C6/C7 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 15.48 (3.3) | 17.62 (1.1) |

| Median (range) | 15.02 (9.05–22.37) | 16.9 (13.59–21.53) |

| T9/T10 | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.88 (1.43) | 9.76 (1.1) |

| Median (range) | 8.99 (5.48–12.52) | 9.97 (7.84–11.5) |

| T max | ||

| Mean (SD) | 18.73 (5.15) | 22.93 (3.78) |

| Median (range) | 19.36 (8.49–26.91) | 22.15 (18.08–30.13) |

Abbreviations: HC, healthy control; PPS, post‐polio syndrome; range, minimum to maximum; SD, standard deviation.

TABLE 4.

Mean differences in gray matter (GM) areas between patients with post‐polio syndrome and age‐ and sex‐matched healthy control subjects

| Intervertebral disc level | Difference (mm2) in GM areas betw. PPS patients and controls |

p Value First rater |

p Value Additional rater |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mean) | (SE) | (95% CI) | |||

| C2/C3 | −1.07 | 0.53 | (−2.19, 0.04) | 0.048 | 0.037 |

| C3/C4 | −3.05 | 0.70 | (−4.23, −1.58) | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| C4/C5 | −3.17 | 0.56 | (−4.36, −1.98) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| C5/C6 | −2.97 | 0.83 | (−4.72, −1.21) | 0.004 | 0.013 |

| C6/C7 | −1.67 | 0.80 | (−3.36, 0.02) | 0.107 | 0.044 |

| T9/T10 | −0.67 | 0.41 | (−1.55, 0.21) | 0.098 | 0.134 |

| T max | −3.96 | 1.78 | (−7.77, −0.15) | 0.041 | 0.044 |

First and additional rater p values were derived from Wilcoxon non‐parametric comparisons.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GM, gray matter; PPS, post‐polio syndrome; SE, standard error.

Bold numbers denote significant p‐values.

Table 5 shows the results of the backward selection procedures of the models 1–3: We found significant associations between SCGM areas and segmental muscle strength measured by handheld dynamometry in corresponding myotomes. While pain, depression and fatigue metrics were each eliminated in the backward selection procedure, (1) SCGM area at C2/C3 remained a significant predictor for neck flexion strength, (2) SCGM area at C5/C6 remained a significant predictor for wrist extension strength and (3) SCGM area at T max remained a significant predictor for ankle dorsiflexion strength, with age and sex as covariates, respectively.

TABLE 5.

Association between muscle strength and gray matter area at intervertebral disc level adjusted for potential risk factors

| Model a | Outcome | Factor | Estimate | SE | t‐value | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Muscle strength (N): | Intercept | 267.91 | 194.24 | 1.38 | 0.190 |

| Adj. r 2 = 0.56 p value = 0.002 | Neck flexion (segment C2/C3) | GM area C2/C3 | 12.83 | 4.99 | 2.57 | 0.022 |

| Age | −4.92 | 2.41 | −2.04 | 0.061 | ||

| Sex | 33.84 | 10.49 | 3.23 | 0.006 | ||

| Model 2 | Muscle strength (N): | Intercept | 66.96 | 127.08 | 0.53 | 0.606 |

| Adj. r 2 = 0.32 p value = 0.032 | Wrist extension (segment C7) | GM area C5/C6 | 6.82 | 3.08 | 2.22 | 0.043 |

| Age | −1.01 | 1.87 | −0.54 | 0.599 | ||

| Sex | 23.1 | 8.41 | 2.75 | 0.015 | ||

| Model 3 | Muscle strength (N): | Intercept | 28.47 | 185.78 | 0.15 | 0.882 |

| Adj. r 2 = 0.68 p value = 0.006 | Ankle dorsiflexion (segment L5) | GM area T max | 9.62 | 2.82 | 3.41 | 0.009 |

| Age | −0.72 | 2.80 | −0.26 | 0.804 | ||

| Sex | 15.38 | 17.33 | 0.89 | 0.401 |

Abbreviations: adj, adjusted; GM, gray matter; N, Newton; SE, standard error.

Based on a post‐mortem study [21] and an in vivo magnetic resonance imaging study in healthy persons [10], the intervertebral disc levels C2/C3, C5/C6 and T max project to the spinal cord segments C2/C3, C7 and L5, respectively.

Multivariate models resulting from the backward selection procedures using a starting model with age and sex as fixed predictor variables and the spinal cord gray matter area at the given intervertebral disc level along with all patient‐reported outcome (PRO) variables with a Pearson correlation coefficient of |r| > 0.2 in univariate analysis as predictor variables and muscle strength at the respective corresponding myotome as outcome. The following PRO variables were included in the starting models: for neck flexion strength, fatigue, pain and depression; for wrist extension strength, pain; and for ankle dorsiflexion strength, depression.

Secondary exploratory analyses

Patients reporting symptomatic UL paresis during the initial infection showed significant cervical SCGM atrophy at levels C3/C4, C4/C5 and C5/C6 compared to HC using multivariable regression analysis with adjustment for age and sex. Patients without symptomatic UL paresis at the time of the initial infection showed significant cervical SCGM atrophy, but only at the level close to the cervical enlargement (C4/C5) (Table 6).

TABLE 6.

Differences in adjusted mean cervical spinal cord gray matter areas between post‐polio syndrome patients with upper limb involvement during the acute infection and healthy control persons and between patients without upper limb involvement during the acute infection and healthy control persons

| GM area (mm2) at intervertebral disc level | Group | Estimate a /SE | 95% CI for the estimate a | Adjusted b mean GM area (mm2)/SE |

p Value First rater |

p Value Additional rater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2/C3 | With UL involvement | −1.14/0.64 | (−2.45, 0.17) | 14.38/0.52 | 0.086 | 0.104 |

| Without UL involvement | −0.91/0.74 | (−2.42, 0.59) | 14.60/0.63 | 0.226 | 0.305 | |

| Controls | 15.51/0.40 | |||||

| C3/C4 | With UL involvement | −3.71/0.72 | (−5.16, −2.25) | 15.61/0.58 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Without UL involvement | −2.02/0.82 | (−3.70, −0.35) | 17.29/0.69 | 0.019 | 0.078 | |

| Controls | 19.32/0.44 | |||||

| C4/C5 | With UL involvement | −4.07/0.66 | (−5.40, −2.74) | 16.65/0.53 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Without UL involvement | −2.19/0.73 | (−3.68, −0.70) | 18.53/0.62 | 0.005 | 0.008 | |

| Controls | 20.71/0.39 | |||||

| C5/C6 | With UL involvement | −3.69/1.02 | (−5.78, −1.62) | 16.40/0.83 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Without UL involvement | −2.22/1.15 | (−4.55, 0.11) | 17.88/0.96 | 0.061 | 0.218 | |

| Controls | 20.10/0.61 | |||||

| C6/C7 | With UL involvement | −2.04/1.06 | (−4.18, 0.11) | 15.49/0.86 | 0.063 | 0.028 |

| Without UL involvement | −1.38/1.18 | (−3.78, 1.02) | 16.15/0.99 | 0.250 | 0.150 | |

| Controls | 17.53/0.63 |

The values in bold type denote significant p‐values.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GM, gray matter; SE, standard error; UL, upper limb.

The estimate equals the difference between a level and the reference level (controls),

Means are least‐square means with adjustment for age and sex using linear regression.

Patients reporting PPS‐related new or worsening UL motor function demonstrated significantly reduced SCGM areas at the levels C3/C4, C4/C5, C5/C6 and C6/C7 compared to HC, while patients with stable UL motor function did not (Table 7). In direct comparison, patients with PPS‐related new or worsening UL motor function showed significantly reduced SCGM areas compared to stable patients at the levels C4/C5 and C5/C6 even after adjusting for the severity of the initial infection in sensitivity analyses by (a) the binary variable respiratory failure or (b) the number of reported regions affected at the time of initial infection [17] at C4/C5 (p = 0.0058, p = 0.0066) and C5/C6 (p = 0.0227, p = 0.0436), respectively.

TABLE 7.

Differences in adjusted mean spinal cord gray matter areas of patients reporting upper limb worsening as part of their post‐polio syndrome versus healthy control persons, and of patients reporting stable upper limb function versus healthy control persons

| GM area (mm2) at intervertebral disc level | Group | Estimate a /SE | 95% CI for the estimate a | Adjusted b mean GM area (mm2)/SE |

p Value First rater |

p Value Additional rater |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C2/C3 | Worsening | −1.31/0.59 | (−2.52, −0.11) | 14.20/0.45 | 0.033 | 0.054 |

| Stable | −0.24/0.88 | (−2.03, 1.55) | 15.27/0.79 | 0.785 | 0.783 | |

| Control | 15.52/0.39 | |||||

| C3/C4 | Worsening | −3.47/0.67 | (−4.84, −2.10) | 15.85/0.52 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Stable | −1.70/1.00 | (−3.74, 0.33) | 17.62/0.90 | 0.099 | 0.174 | |

| Control | 19.33/0.45 | |||||

| C4/C5 | Worsening | −4.04/0.57 | (−5.20, −2.89) | 16.68/0.44 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Stable | −1.14/0.83 | (−2.82, 0.54) | 19.59/0.75 | 0.177 | 0.246 | |

| Control | 20.73/0.37 | |||||

| C5/C6 | Worsening | −4.02/0.89 | (−5.82, −2.22) | 16.09/0.68 | <0.001 | 0.003 |

| Stable | −0.44/1.29 | (−3.06, 2.18) | 19.67/1.16 | 0.734 | 0.866 | |

| Control | 20.12/0.57 | |||||

| C6/C7 | Worsening | −2.78/0.92 | (−4.45, −0.70) | 14.96/0.71 | 0.009 | 0.002 |

| Stable | 0.51/1.34 | (−2.22, 3.24) | 18.05/1.21 | 0.706 | 0.810 | |

| Control | 17.54/0.60 |

The values in bold type denote significant p‐values

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; GM, gray matter; SE, standard error.

The estimate equals the difference between a level and the reference level (controls),

Means are least‐square means with adjustment for age and sex using linear regression.

Lastly, in multivariate regression analysis adjusting for severity of the initial infection expressed as the number of regions involved, we found no significant associations between SCGM atrophy and (a) the age at or (b) the time since the acute infection.

DISCUSSION

Post‐polio syndrome is a rare, presumed pure, lower motor neuron disorder that we chose in this study as a model for other neurodegenerative, genetic or autoimmune diseases affecting the SCGM to clinically validate the novel imaging methodology rAMIRA for SCGM quantification. Based on rAMIRA imaging [15], our study provides in vivo evidence of significant and preferential cervical and thoracic SCGM atrophy in patients with PPS compared to age‐ and sex‐matched HC. SCGM areas show segment‐wise significant associations with muscle strength in the corresponding myotomes, even when covarying for the level of depression, fatigue and pain, comorbidities that are frequently found in PPS [25]. This indicates the clinical relevance on a segmental level of the SCGM atrophy observed.

The most common theory of PPS etiopathogenesis presumes a decompensation of the enlarged motor units initially formed as a response to motor neuron loss during the acute infection. During the healthy aging process, the immune system undergoes a series of changes termed “immunosenescence” accompanied by a low‐grade sterile inflammation called “inflamm‐aging” [26, 27]. These changes are present in the central nervous system and lead to microglial and neuronal dysfunction and impaired repair mechanisms [28, 29]. It seems plausible that previously damaged neurons and those in control of giant motor units may be more susceptible to further damage due to oxidative stress or immune‐mediated processes, thus leading to the decompensation of motor neurons resulting in the development of PPS as the second phase of the disease [30, 31, 32].

To further explore whether the SCGM atrophy observed in our PPS cohort can be attributed to a secondary process or rather constitute residuals of the initial infection we assessed in a subanalysis cervical SCGM area differences between patients who reported a PPS‐related worsening of UL function and patients with stable UL function and HC. Patients with PPS‐related worsening UL function demonstrated significant cervical SCGM atrophy at all investigated cervical cord levels while patients with stable UL function did not significantly differ compared to controls. Cervical SCGM areas in patients with PPS‐related UL worsening were reduced by 7%–24% compared to patients with stable UL function, compatible with a PPS‐associated decline of SCGM area in the former.

One study described an association between the severity of the initial infection and the probability of developing PPS, that is, patients in need of hospitalization, ventilator use, and with tetraparesis were more likely to develop PPS over a time span of 30–40 years [33]. Furthermore, in the same study, patients older than 10 years at onset had a higher probability of developing PPS than younger patients [33]. To explore whether the cervical SCGM atrophy observed in patients with worsening UL function could be attributed to the severity of the initial infection, we performed additional sensitivity analyses accounting for the patient‐reported disease burden at the time of the acute infection. Both the worsening and the stable patient groups showed the same prevalence of respiratory insufficiency at the acute infection as easily self‐reportable surrogates for a severe initial disease course (20%, respectively). The difference in cervical SCGM area observed between patients with worsening vs. stable UL function remained statistically significant after adjustment for the severity of the initial infection expressed as the number of regions involved [17]. Taken together, our findings tentatively suggest that the cervical SCGM atrophy observed in patients reporting PPS‐related UL worsening can not only be attributed to the severity of the initial infection, but develops (at least partly) independently from it. However, these results will have to be confirmed in studies with larger sample sizes.

Our observation that both age at infection and time since infection did not correlate with the extent of SCGM atrophy when adjusting for the severity of the acute infection supports the assumption that PPS manifestation is not just an aging effect.

Patients reporting an UL involvement during the acute infection consistently showed significant and widespread cervical SCGM atrophy. A somewhat less pronounced, but significant, GM atrophy at the cervical enlargement level (C4/C5) could be detected even in those patients without UL involvement during the acute infection. This observation is in line with the existing evidence from histopathological [2] and eletrophysiological [34] studies that neuronal damage during the acute infection is more extensive than is clinically detectable and also involves motor neurons of SC segments that correspond to clinically unaffected myotomes.

There are some limitations to this study. Due to the rarity of the disease, this study's sample size is rather small, but in line with other studies [35]. As we deployed our recently developed MRI sequence [15], we chose a single‐center design to ensure the highest image quality and consistency in the acquisition of images, which were obtained by the same experienced MRI technician (T.H.). While the rAMIRA approach has already proved valuable in the development of normalization strategies for SC metrics to reduce anatomical variability 36, to date, direct comparisons between rAMIRA and other dedicated SC imaging approaches were not conducted.

The acquisition time of 3 min per slice is relatively long. Obviously common types of MRI acceleration techniques such as SENSE and GRAPPA can be used but will reduce the overall signal‐to noise ratio (SNR). Owing to both the more difficult RF reception conditions at the thoracic compared to the cervical SC (fewer signal‐contributing RF coil elements, larger noise‐contributing reception volumes) and its finer structure requiring higher spatial (in‐plane) resolutions, the current rAMIRA protocol operates at the minimum SNR for reliable segmentation and quantitative evaluation of the thoracic segments. The rAMIRA protocol employed was shown to achieve a careful balance between thoracic signal reception conditions, minimum SNR, achieved GM–WM contrast, essential high in‐plane resolutions, sampling, and acquisition time [15]. To ensure identical imaging along the entire SC, the same rAMIRA protocol was used for the cervical SC, although more favorable imaging conditions at the cervical SC would allow a protocol with reduced acquisition time.

Further methodological refinements including the development of rAMIRA specific automatic segmentation methods (as described in Appendix S1) are ongoing, which will facilitate larger multicentric designs in the study of this rare disease in the future.

A further limitation is the cross‐sectional study design. Information about change over time relied on SRO measures and may therefore be more prone to other factors. Here, follow‐up studies are warranted to investigate the evolution of SCGM atrophy and clinical metrics over time.

CONCLUSIONS

The rAMIRA approach is a novel, promising, clinically feasible and sensitive method for segment‐wise quantitation of GM atrophy in the cervical and thoracic SC in patients with lower motor neuron disorders. This study demonstrated its clinical applicability and validated it in patients with PPS, a presumed pure, lower motor neuron disorder, which can serve as a model for other neurodegenerative, genetic or autoimmune diseases of the SCGM.

Patients with PPS show significant SCGM atrophy, particularly at levels close to the cervical and lumbar enlargements. Even after adjustment for the level of depression, fatigue and pain, potential confounding symptoms frequently observed in PPS, SCGM atrophy is significantly and segment‐wise associated with muscle strength in corresponding myotomes. Moreover, SCGM atrophy is associated with patient‐reported PPS‐related functional decline. Secondary analyses suggest that SCGM atrophy is rather due to a second disease phase than being a sole residuum of the initial infection or a pure aging effect. These observations support the hypothesis of a focally accentuated neurodegenerative process in the SC underlying PPS. Larger, ideally multicentric, longitudinal studies conducted over a sufficiently long timespan are an important next step to confirm our results and gain more insights into the development of SCGM atrophy over time and its correlation to clinical symptom evolution in patients with PPS.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to the content of this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Maria Janina Wendebourg: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); project administration (equal); visualization (lead); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Matthias Weigel: Conceptualization (equal); methodology (equal); software (equal); writing – original draft (lead); writing – review and editing (equal). Laura Richter: Data curation (equal); formal analysis (equal); investigation (equal); project administration (equal); Writing – review and editing (equal). Vanya Gocheva: Investigation (supporting); project administration (supporting). Patricia Hafner: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Anna‐Lena Orsini: Data curation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Valentina Crepulja: Data curation (supporting); investigation (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Simone Schmidt: Data curation (supporting); investigation (supporting). Antal Huck: Investigation (supporting); methodology (supporting); software (equal). Johanna Oechtering: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Maria Blatow: Methodology (supporting); supervision (supporting); writing – review and editing (supporting). Tanja Haas: Formal analysis (supporting); investigation (equal). Cristina Granziera: Writing – review and editing (supporting). Ludwig Kappos: Supervision (supporting); Writing – review and editing (supporting). Philippe Cattin: Methodology (equal); software (equal); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Oliver Bieri: Conceptualization (supporting); funding acquisition (equal); investigation (equal); methodology (equal); resources (equal); software (equal); supervision (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Dirk Fischer: Conceptualization (equal); resources (supporting); writing – review and editing (equal). Regina Schlaeger: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (lead); funding acquisition (lead); investigation (lead); methodology (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (lead); writing – review and editing (lead).

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank the patients and healthy controls for their participation and Prof. Monsch and his team for helping with recruitment of healthy controls from their healthy aging cohort at the University Department of Geriatric Medicine Felix Platter, Basel, Switzerland. They also wish to thank Dr. Leticia Grize for her valuable comments on the manuscript and data analysis. Open access funding provided by Universitat Basel.

Wendebourg MJ, Weigel M, Richter L, et al. Spinal cord gray matter atrophy is associated with functional decline in post‐polio syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2022;29:1435–1445. doi: 10.1111/ene.15261

Maria Janina Wendebourg and Matthias Weigel equal contributors.

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03561623).

Funding information

This study was supported by the University of Basel (DMS2382 to R.S.), the Freiwillige Akademische Gesellschaft Basel, and the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) [grant number 320030_156860]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Upon reasonable request, we will render the detailed results derived from the reported analyses available.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bodian D. Poliomyelitis. Neuropathologic observations in relation to motor symptoms. JAMA. 1947;134:1148‐1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dalakas MC. The post‐polio syndrome as an evolved clinical entity. Definition and clinical description. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;753:68‐80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kaminski HJ, Tresser N, Hogan RE, Martin E. Spinal cord histopathology in long‐term survivors of poliomyelitis. Muscle Nerve. 1995;18:1208‐1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bodian D. Histopathologic basis of clinical findings in poliomyelitis. Am J Med. 1949;6:563‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bodian D. Pathogenesis of poliomyelitis. Am J Health Nations Health. 1952;42:1388‐1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lo JK, Robinson LR. Post‐polio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis: Part 1. Pathogenesis, biomechanical considerations, diagnosis, and investigations. Muscle Nerve. 2018;58:751‐759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Farbu E, Gilhus NE, Barnes MP, et al. EFNS guideline on diagnosis and management of post‐polio syndrome. Report of an EFNS task force. Eur J Neurol. 2006;13:795‐801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. March of Dimes Guidelines for People Who Have Had Polio. White Plains, N.Y., 2002. https://www.marchofdimes.org/mission/polio.aspx. Accessed February 8, 2019.

- 9. Stroman PW, Wheeler‐Kingshott C, Bacon M, et al. The current state‐of‐the‐art of spinal cord imaging: methods. NeuroImage. 2014;84:1070‐1081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Papinutto N, Schlaeger R, Panara V, et al. 2D phase‐sensitive inversion recovery imaging to measure in vivo spinal cord gray and white matter areas in clinically feasible acquisition times. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42:698‐708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Papinutto N, Henry RG. Evaluation of intra‐ and interscanner reliability of MRI protocols for spinal cord gray matter and total cross‐sectional area measurements. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;49:1078‐1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schlaeger R, Papinutto N, Panara V, et al. Spinal cord gray matter atrophy correlates with multiple sclerosis disability. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:568‐580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schlaeger R, Papinutto N, Zhu AH, et al. Association between thoracic spina cord gray matter atrophy and disability in multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72:897‐904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weigel M, Bieri O. Spinal cord imaging using averaged magnetization inversion recovery acquisitions. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79:1870‐1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Weigel M, Haas T, Wendebourg MJ, Schlaeger R, Bieri O. Imaging of the thoracic spinal cord using radially sampled averaged magnetization inversion recovery acquisitions. J Neurosci Methods. 2020;343:108825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papinutto N, Schlaeger R, Panara V, et al. Age, gender and normalization covariates for spinal cord gray matter and total cross‐sectional areas at cervical and thoracic levels: a 2D phase sensitive inversion recovery imaging study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0118576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Balendra R, Al Khleifat A, Fang T, Al‐Chalabi A. A standard operating procedure for King's ALS clinical staging. Amyotroph Lateral Scler Frontotemporal Degener. 2019;20(3–4):159‐164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. TRICALS Quick Reference Isometric Strength Testing protocol. Version September 2016.

- 19. Versteegh T, Beaudet D, Greenbaum M, Hellyer L, Tritton A, Walton D. Evaluating the reliability of a novel neck‐strength assessment protocol for healthy adults using self‐generated resistance with a hand‐held dynamometer. Physiother Can. 2015;67:58‐64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shefner JM, Liu D, Leitner ML, et al. Quantitative strength testing in ALS clinical trials. Neurology. 2016;87:617‐624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kameyama T, Hashizume Y, Sobue G. Morphologic features of the normal human cadaveric spinal cord. Spine. 1996;21:1285‐1290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Koopman FS, Brehm MA, Heerkens YF, Nollet F, Beelen A. Measuring fatigue in polio survivors: content comparison and reliability of the Fatigue Severity Scale and the Checklist Individual Strength. J Rehabil Med. 2014;46:761‐767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361‐370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain. 1992;50:133‐149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McNalley TE, Yorkston KM, Jensen MP, et al. Review of secondary health conditions in postpolio syndrome: prevalence and effects of aging. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;94:139‐145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Franceschi C, Capri M, Monti D, et al. Inflammaging and anti‐inflammaging: a systemic perspective on aging and longevity emerged from studies in humans. Mech Ageing Dev. 2007;128:92‐105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fulop T, Larbi A, Dupuis G, Le Page A, Frost EH, Cohen AA, et al. Immunosenescence and inflamm‐aging as two sides of the same friends or foes? Front Immunol. 1960;2018:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rawji KS, Mishra MK, Michaels NJ, Rivest S, Stys PK, Yong VW. Immunosenescence of microglia and macrophages: impact on the ageing central nervous system. Brain. 2016;139:653‐661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Deleidi M, Jäggle M, Rubino G. Immune aging, dysmetabolism, and inflammation in neurological diseases. Front Neurosci. 2015;9:172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Miller DC. Post‐polio syndrome spinal cord pathology. Case report with immunopathology. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;753:186‐193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Larsson L, Li X, Tollbäck A, Grimby L. Contractile properties in single muscle fibres from chronically overused motor units in relation to motoneuron firing properties in prior polio patients. J Neurol Sci. 1995;132:182‐192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gordon T, Hegedus J, Tam SL. Adaptive and maladaptive motor axonal sprouting in aging and motoneuron disease. Neurol Res. 2004;26:174‐185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Halstead LS, Wiechers DO, Rossi CD. Results of a survey of 201 polio survivors. South Med J. 1985;78:1281‐1287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. McComas AJ, Quartly C, Griggs RC. Early and late losses of motor units after poliomyelitis. Brain. 1997;120:1415‐1421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gawel M, Zalewska E, Szmidt‐Salkowska E, et al. Motor Unit Number Index (MUNIX) as a biomarker of motor unit loss in post‐polio syndrome versus needle EMG. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 2019;46:35‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kesenheimer EM, Wendebourg MJ, Weigel M, et al. Normalization of spinal cord total cross‐sectional and gray matter areas as quantified with radially sampled averaged magnetization inversion recovery acquisitions. Front Neurol. 2021;12: 637198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Upon reasonable request, we will render the detailed results derived from the reported analyses available.