Abstract

Objective

The formation of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol is a brain‐specific mechanism of cholesterol catabolism catalyzed by cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase (CYP46A1, also known as CH24H). CH24H has been implicated in various biological mechanisms, whereas pharmacological lowering of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol has not been fully studied. Soticlestat is a novel small‐molecule inhibitor of CH24H. Its therapeutic potential was previously identified in a mouse model with an epileptic phenotype. In the present study, the anticonvulsive property of soticlestat was characterized in rodent models of epilepsy that have long been used to identify antiseizure medications.

Methods

The anticonvulsive property of soticlestat was investigated in maximal electroshock seizures (MES), pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) acute seizures, 6‐Hz psychomotor seizures, audiogenic seizures, amygdala kindling, PTZ kindling, and corneal kindling models. Soticlestat was characterized in a PTZ kindling model under steady‐state pharmacokinetics to relate its anticonvulsive effects to pharmacodynamics.

Results

Among models of acutely evoked seizures, whereas anticonvulsive effects of soticlestat were identified in Frings mice, a genetic model of audiogenic seizures, it was found ineffective in MES, acute PTZ seizures, and 6‐Hz seizures. The protective effects of soticlestat against audiogenic seizures increased with repetitive dosing. Soticlestat was also tested in models of progressive seizure severity. Soticlestat treatment delayed kindling acquisition, whereas fully kindled animals were not protected. Importantly, soticlestat suppressed the progression of seizure severity in correlation with 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering in the brain, suggesting that 24S‐hydroxycholesterol can be aggressively reduced to produce more potent effects on seizure development in kindling acquisition.

Significance

The data collectively suggest that soticlestat can ameliorate seizure symptoms through a mechanism distinct from conventional antiseizure medications. With its novel mechanism of action, soticlestat could constitute a novel class of antiseizure medications for treatment of intractable epilepsy disorders such as developmental and epileptic encephalopathy.

Keywords: anticonvulsants, cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase, CYP46A1, epilepsy, soticlestat

Key Points.

Soticlestat is a novel inhibitor of CH24H, a brain‐specific enzyme responsible for conversion of cholesterol into 24S‐hydroxycholesterol

Soticlestat was found effective in seizure models with secondary generalization but ineffective in acutely induced seizures in neurologically intact animals

To obtain a detectable level of anticonvulsive efficacy, brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol needs to decrease by 50%–60%

CH24H inhibitor could constitute a novel class of antiseizure medication, with efficacy properties different from conventional drugs

1. INTRODUCTION

As a fundamental component of biological membrane physiology, cholesterol metabolism occurs in various biochemical pathways, 1 , 2 , 3 including the formation of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol, a brain‐specific mechanism of cholesterol catabolism. 4 , 5 The catabolic product, a brain‐specific side‐chain oxysterol, passes through the blood–brain barrier and is further metabolized into bile acids in the liver. Also known as cerebrosterol, 6 24S‐hydroxycholesterol has been extensively studied as a circulation biomarker reflecting metabolic activity in the brain, mostly in neurological disorders. 7 , 8 , 9 However, our understanding of what pathophysiological implications can arise from an increase or decrease of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol in the brain remains incomplete.

Substantial progress has been made into the biological functions of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol. A variety of receptors and ion channels can be either positively or negatively modulated by 24S‐hydroxycholesterol. These include the liver X receptor, 10 the estrogen receptor, 11 the RAR‐related orphan receptor, 12 the N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate (NMDA) receptor, 13 the BK channel, 14 and the smoothened G‐protein‐coupled receptor. 15 Furthermore, 24S‐hydroxycholesterol has been implicated in various cellular mechanisms such as proinflammatory signaling, 16 necroptosis, 17 oxidative stress, 18 and TrkB signaling. 19

Given this array of diverse functions, pharmacological alteration of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol levels may exert different effects in various disease conditions. CYP46A1 (also known as cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase [CH24H]) is the enzyme responsible for conversion of cholesterol into 24S‐hydroxycholesterol. 20 Pioneering work demonstrated that the reverse transcriptase inhibitor efavirenz can enhance the enzyme activity of CH24H, leading to a series of investigations in preclinical models of Alzheimer disease. 21 , 22 , 23 In contrast, the extended therapeutic potential of CH24H inhibition had not been extensively characterized until the recent discovery of soticlestat, a small molecule inhibitor of the enzyme. 24 Currently in Phase 3 clinical studies for Dravet syndrome and Lennox–Gastaut syndrome, soticlestat has already clinically demonstrated pharmacodynamic effects on levels of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol in the plasma in an exposure‐dependent manner. 25 , 26

Our previous study demonstrated that soticlestat has the potential to limit excessive neural excitation in an epileptic transgenic mouse model. 24 The transgenic mouse model carries human amyloid precursor protein and presenilin 1 (APP/PS1‐Tg) and is known for excitatory/inhibitory imbalance and premature death reminiscent of sudden unexpected death in epilepsy (SUDEP). 27 APP/PS1‐Tg mice yielded a remarkable survival benefit when crossbred with CH24H‐knockout animals. 28 Soticlestat lowered brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol in the model, and substantially reduced premature deaths. 24

The survival benefits of soticlestat treatment suggested that CH24H inhibition could be a novel therapeutic approach for epilepsy. This hypothesis is also supported by the antiseizure activity and SUDEP prevention by soticlestat in mouse models of Dravet syndrome (DS) in which animals harbor a mutation in the Scn1a gene. 29 Although DS models are gaining increasing attention as a drug screening platform, 30 they have not yet been standardized enough for a reliable comparison to the historic data. In this sense, “the gold standard” models such as maximum electroshock seizures (MES), 31 subcutaneous pentylenetetrazol (scPTZ) seizures, 32 6‐Hz psychomotor seizures, 33 audiogenic seizures, 34 kindled seizures, and kindling acquisition 35 , 36 still remain important resources. By comparison with the large body of historic data, these models will be especially valuable as a platform for characterizing a new molecular entity such as soticlestat.

This study describes the anticonvulsive property of soticlestat in the aforementioned models. Soticlestat was found ineffective in the MES, scPTZ, and 6‐Hz (32 and 44 mA) models of seizure induction; however, it was effective in audiogenic seizures and kindling acquisition. To provide translational insights, we also investigated how 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering relates to the antiseizure effects of soticlestat. The more aggressive the 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering, the more potent was the suppression of kindling acquisition. Overall, the data suggest that CH24H inhibition constitutes a novel class of antiseizure medications (ASMs).

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Administration of soticlestat

Soticlestat was synthesized in the Neuroscience Drug Discovery Unit at Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. For oral administration, soticlestat was suspended in .5% (wt/vol) methyl cellulose solution (Methyl Cellulose 50cp, Wako Pure Chemical Industries), and the prepared drug suspension was administered once daily to mice and rats at the volume of 10 and 5 ml/kg, respectively. For subcutaneous infusion, soticlestat was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) at 100 mg/ml and then mixed with an equal volume of polyethylene glycol 400 (PEG 400). The soticlestat solution in DMSO/PEG 400 (1:1) that we obtained was then diluted to the indicated doses. Osmotic pumps (Model 2004, Durect) were filled with the prepared drug solution and stored overnight in saline at 37°C. The pumps were then implanted subcutaneously on the backs of the mice under anesthesia with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg).

2.2. Animals

Adult male (8–10 weeks) Sprague Dawley rats weighing 100–150 g and adult male CF‐1 mice (25–30 g) were obtained from Charles River. Male and female Frings mice (18–30 g) were obtained from a colony housed and maintained at the University of Utah (Department of Comparative Medicine). Animals were cared for in a matter consistent with the recommendations detailed in the National Research Council publication, “Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.”

Five‐week‐old male mice from the Institute of Cancer Research were used in the PTZ kindling (20–40 g, CLEA Japan). The animals were housed at a temperature of 22 ± 1°C with a 12‐h light–dark cycle (lights on 7:00 to 19:00), and allowed free access to food and water. The animal experiments were approved by the Experimental Animal Care and Use Committee of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited and conducted in accordance with the guidelines. The animal care and use program is accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International Council on Accreditation. The AAALAC sets standards that call for the humane care and use of laboratory animals by enhancing animal well‐being, improving the quality of research, and advancing scientific knowledge relevant to humans and animals.

2.3. Measurement of soticlestat pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics

Soticlestat concentrations in plasma and brain were determined by liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry following the previously described method. 24 Brain levels of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol were determined by high‐performance liquid chromatography. 24 To collect brain samples, cerebellum was removed, in which CH24H expression is considerably lower than other areas. 37

2.4. Animal behavioral experiments

The methods of MES, scPTZ, 6‐Hz psychomotor, Frings audiogenic seizure, amygdala kindling, PTZ kindling, corneal kindling, and the rotarod test are described in Appendix S1.

2.5. Statistical analysis

The number of animals protected from seizures or fully kindled were not selected for statistical analysis due to the parametric nature of indices. In the audiogenic seizure model, median effective dose (ED50) values were calculated using Probit analysis. Times to start and stop either wild run or tonic‐extension seizures (TE) in Frings mice, and the duration (stop time − start time) were evaluated by two‐way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni a posteriori test. A p‐value < .05 was considered significant.

In the amygdala kindling model, comparisons for parametric datasets were made using a Student t‐test, with a p‐value < .05 considered significant, whereas no paired analyses were performed on each time point. For comparisons of the number of stimulations to reach the first generalized seizure or fully kindled status, if the criterion was not met during the analysis period, a value equal to the maximum number of stimulations (plus one) occurring during the analysis period was used.

In the PTZ kindling model, no paired analyses were performed on each time point. Instead, cumulative seizure scores were defined as an overall seizure burden. The statistical significance between two experimental groups was evaluated by Student t‐test, with p‐value < .05 considered significant. To evaluate dose dependency, one‐tailed Williams test was used, and p‐values < .025 were considered significant.

3. RESULTS

To evaluate the potential anticonvulsive properties of soticlestat, MES, scPTZ, 6‐Hz psychomotor, and Frings audiogenic seizure models were employed. We previously showed that soticlestat took a minimum of 3 days of repetitive administration before its pharmacodynamics reached a maximum because of the slow turnover of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol levels in the brain. 24 Soticlestat was thus administered for 3 days prior to seizure induction for optimal pharmacodynamics. The proportion of animals protected from elicited seizures in each model is summarized in Table 1. The selected doses of soticlestat achieved brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering by approximately 50% in both mice and rats in agreement with the treatment condition found effective in the previous study. 24 In this initial screening, notable anticonvulsive effects of soticlestat were observed only in the audiogenic seizure model. Seizure‐caused deaths were observed in the mouse MES model. Six of eight mice died in the vehicle‐treated group following seizure induction, whereas no deaths were observed in the soticlestat arm (data not shown). Mice underwent rotarod testing, and no signs of motor impairment were noted (Table 1). Rats were observed only for general signs of behavioral impairment, and no abnormalities were observed. These observations agree with our previous studies, in which soticlestat was administered with a regimen that yields nearly full enzyme inhibition. 24

TABLE 1.

Screening study of soticlestat in the MES model (mouse and rat), the mouse scPTZ model, the mouse 6‐Hz model of psychomotor seizures (32‐mA and 44‐mA stimulation intensities), and AGS using Frings mice

| Test | Soticlestat, mg/kg POQD | Protected/tested, n | Rotarod failures/tested, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| MES | Vehicle | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| 30 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| MES, rat | Vehicle | 1/8 | na |

| 100 | 0/8 | na | |

| scPTZ | Vehicle | 0/8 | na |

| 30 | 0/8 | na | |

| 6 Hz, 32 mA | Vehicle | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| 30 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| 6 Hz, 44 mA | Vehicle | 0/8 | 0/8 |

| 30 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| AGS | Vehicle | 0/8 | na |

| 30 | 7/8 | na |

Animals were treated with soticlestat at the indicated dose for 3 days prior to the seizure testing.

Abbreviations: AGS, audiogenic seizures; MES, maximum electroshock seizures; na, not applicable; POQD, orally once daily; scPTZ, subcutaneous pentylenetetrazol.

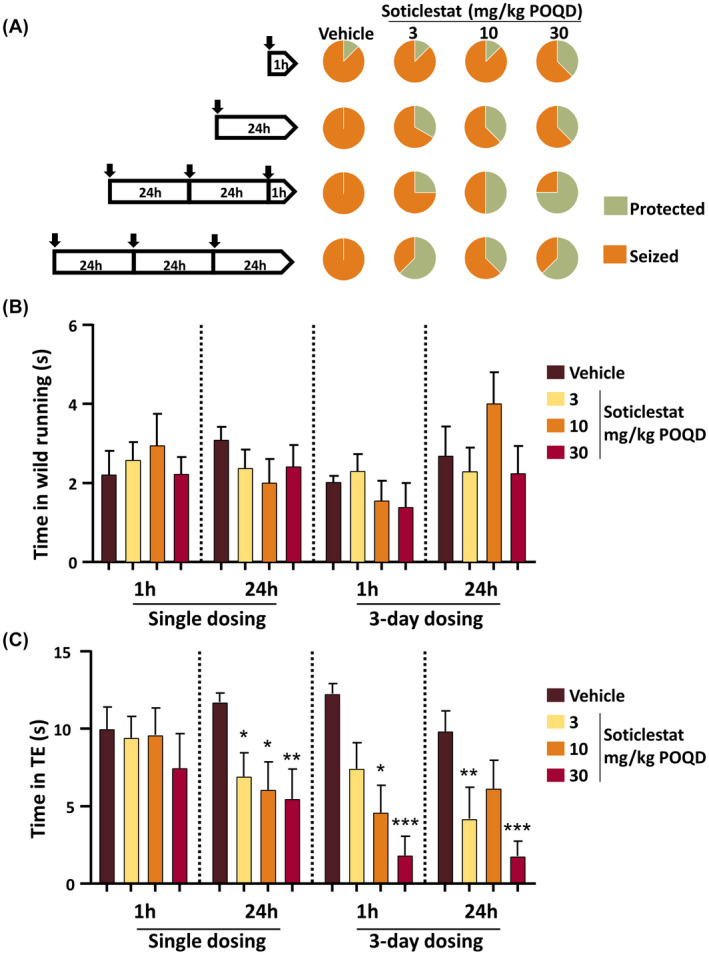

To further characterize the protective effects of soticlestat found in the Frings model, a dose‐ranging study was conducted. To better understand soticlestat's mechanism of action, Frings mice underwent four different treatment paradigms (Figure 1A). The protected proportion of animals is shown in Figure 1A and in Table S1. The clearest dose dependency was observed in the group that received seizure induction 1 h after the last administration of the 3‐day treatment. In this cohort of animals, seizure protection was 25%, 50%, and 75% for 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg, respectively. The ED50 of soticlestat in the Frings model was estimated at 10.7 mg/kg (the 95% confidence interval included the entire dosing range).

FIGURE 1.

Dose‐ and time‐dependent effects of soticlestat on audiogenic seizures (AGS) in Frings mice. (A) Experimental design and the overall seizure protection by soticlestat. Each of the black arrows in the pentagonal diagrams on the left‐hand side indicates soticlestat administration, which was given at 3, 10, and 30 mg/kg (orally once daily [POQD]) singly or three times before seizure induction. The numbers in the diagrams indicate hours prior to auditory seizure induction. The pie charts on the right‐hand side indicate the proportion of mice protected from AGS in each different dosing condition. The data are given in Table S1. (B) Effects of soticlestat on the time spent in wild‐running behaviors. (C) Effects of soticlestat on the time spent in tonic‐extension seizures (TE). Data are mean ± SEM (n = 8–13). *, **, ***p < .05, .01, .001, respectively, compared to the vehicle control group in the same treatment paradigm (two‐way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni posttest)

Figure 1B,C shows the time duration spent in wild running following the onset of auditory stimulation and TE, respectively. In general, the duration of wild running did not show obvious effects associated with soticlestat doses (Figure 1B). In contrast, the change in TE duration represented the effects on seizure protection well (Figure 1A,C). Overall, repetitive treatments with soticlestat yielded a greater extent of protection than the single dosing paradigm (Figure 1C). The 30‐mg/kg group consistently experienced the shortest duration of TE, whereas discrepancies were found in the 3‐ and 10‐mg/kg groups among different treatment conditions.

Unlike neurologically intact animals used in the MES, scPTZ, and 6‐Hz models, Frings mice have an underlying pathology accountable for the innate susceptibility to seizures. 38 , 39 It was thus assumed that soticlestat may modify neurological conditions behind seizure susceptibility. To test the hypothesis, a seizure model with progressive phenotypes was employed. Kindling is an irreversible acquisition of seizure susceptibility, mimicking a process of epileptogenesis in humans. 40 Soticlestat was given to rats in parallel with amygdala stimulations to assess its effects on the process of kindling development. The duration of afterdischarge (AD) was electrographically measured at every kindling stimulation as a quantitative marker of focal seizures. 35 , 41 In a pilot dose‐finding study, signals of efficacy were found at 30 and 100 mg/kg (orally once daily [POQD], Table S2). To confirm the effects, the dose of 100 mg/kg was further tested. The kindling acquisition curve of the soticlestat group was separated downward from that of the vehicle‐treated control animals (Figure 2A).

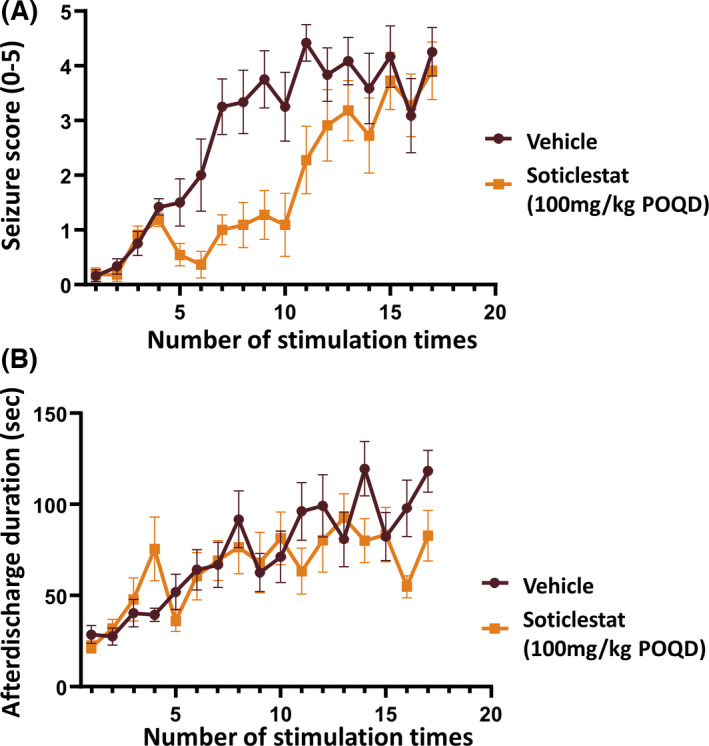

FIGURE 2.

Time course of soticlestat effects on seizure progression in the rat amygdala kindling model. Treatment was started on the first day of kindling stimulation and maintained once daily over the study period. Statistical analyses were performed on various indices and shown in Table 2. (A) Change of Racine seizure severity scores over the course of kindling stimulation in parallel with soticlestat administration (100 mg/kg orally once daily [POQD]). (B) Change of afterdischarge duration during the development of kindling. Data are plotted as mean ± SEM (n = 12)

The separation of the two curves was retained in the first half of the testing period, but gradually became smaller toward the endpoint, indicating a delay of seizure progression but not a complete prevention. The average seizure score of the vehicle‐treated control group and the soticlestat group was 4.3 and 3.9 at the study end point, respectively. Meanwhile, soticlestat seemingly had little impact on the duration of AD (Figure 2B). AD duration progressed during the course of kindling stimulation in both the vehicle‐treated control and the soticlestat group with a similar increasing trend. Table 2 describes the effects of soticlestat on the acquisition of amygdala kindling in detail. Soticlestat had no significant effects on the number of stimulations given until the first representation of seizures. At the endpoint, nine of 12 vehicle‐controlled rats reached the fully kindled state versus five of 11 in the soticlestat group. Statistically significant differences were revealed between the vehicle treatment and the soticlestat treatment in the following indices: number of stimulations to the first generalized seizure, total number of generalized seizures, and number of stimulations to the fully kindled status (p < .05, Student t‐test).

TABLE 2.

Afterdischarge and behavioral seizure observations during the rat amygdala kindling study, following administration of vehicle or soticlestat

| Vehicle | Soticlestat, 100 mg/kg POQD | Statistical significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stimulations to the first seizure, n | 2.7 ± 1.0 | 2.8 ± 1.0 | ns |

| Stimulations to the first generalized seizure, n | 8.9 ± 3.8 | 13.2 ± 3.6 | p < .05 |

| Total generalized seizures, n | 8.2 ± 4.2 | 4.4 ± 3.5 | p < .05 |

| Consecutive generalized seizures, n | 7.0 ± 4.9 | 3.8 ± 3.6 | ns |

| Mean afterdischarge duration, s | 72.8 ± 22.8 | 65.2 ± 25.5 | ns |

| Fully kindled rats, n a | 9/12 | 5/11 | na |

| Stimulations to fully kindled status, n a | 12.9 ± 3.3 | 16.4 ± 2.2 | p < .05 |

Treatment was started on the first day of kindling stimulation and maintained once daily over the study period.

Abbreviations: na, not applicable; ns, not significant; POQD, orally once daily.

Five Stage 4–5 seizures over 8 days. Statistical significance was assessed with a t‐test.

To relate the soticlestat effects to its pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) in detail, a mouse model of PTZ kindling development was employed. 42 Soticlestat decreased brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol levels in a dose‐dependent manner in line with systemic and brain exposure levels (Figure 3A–C). It should be noted that the observed systemic exposure levels were much lower than those achievable in humans. 25

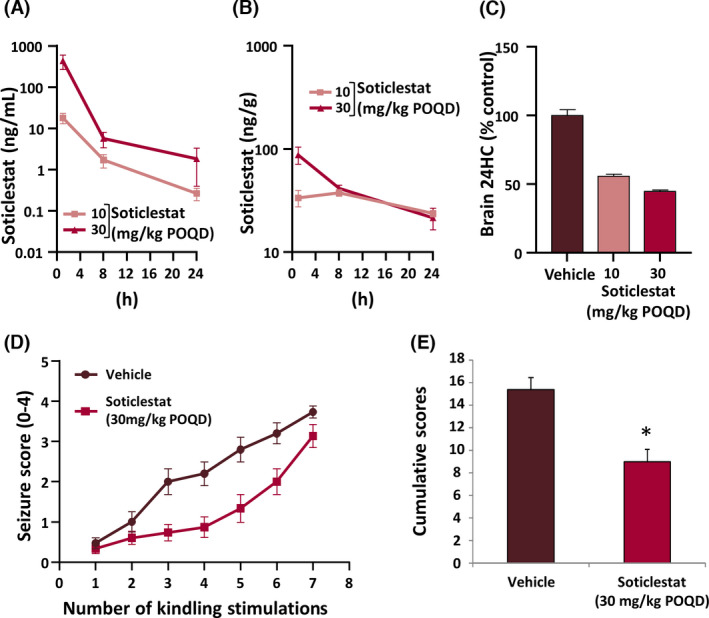

FIGURE 3.

Soticlestat pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics and treatment effects on seizure progression in the mouse pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) kindling model. (A) Plasma and (B) brain soticlestat exposure levels during the 24 h following a single administration of soticlestat to kindled mice (10 and 30 mg/kg orally once daily [POQD]). (C) Effects of repetitive soticlestat treatments on the brain level of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol (24HC; 10 and 30 mg/kg POQD for 3 days). (D) Effects of soticlestat (30 mg/kg POQD) on the progression of seizure severity over the course of PTZ stimulation. Treatment was started on the first day of kindling stimulation and maintained once daily over the study period. (E) Cumulation of Racine scores. *p < .05 compared with the vehicle‐treated control group (Student t‐test). Data are mean ± SEM

At the dose of 30 mg/kg (POQD), soticlestat retarded kindling acquisition, albeit with incomplete suppression (Figure 3D). A similar trend was already observed in the rat kindling model (Figure 2A). To quantify the treatment effects on kindling acquisition, scores of each individual mouse were added as an index of total severity burden. At the dose yielding a 55% lowering in brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol levels, soticlestat reduced the total seizure severity by 42% (Figure 3E).

To investigate the relationship between soticlestat PD effects and anticonvulsive efficacy in more detail, the drug effect was further characterized under a steady‐state PK/PD condition, in which mice were continuously exposed to soticlestat through a subcutaneous osmotic pump during the course of kindling. Subcutaneous infusion (SC inf) was found to be a more effective administration route to achieve greater PD effects of soticlestat than oral gavage. 24 Figure 4A shows the course of kindling development in each of the treatment arms over the four PTZ stimulations in 11 days. A marked suppression of seizure progression was observed in the 3‐ and 10‐mg/kg groups (SC inf) throughout the testing period. The distribution of seizure severity monitored over the entire study period is summarized in Figure 4B. The exact numbers of seizure events at each severity score are shown in Table S3. A clear and dose‐dependent trend was observed toward fewer generalized full motor seizures (Score 4). No Score 4 seizures were observed in the 3‐ and 10‐mg/kg groups (SC inf). To quantify the treatment effects of soticlestat, accumulation of seizure scores was calculated (Figure 4C). Statistically significant effects were seen at the dose of 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg (SC inf, p < .025, one‐tailed Williams test). The cumulative seizure score at the highest dose (10 mg/kg SC inf) was 75% lower than that of the vehicle‐treated control group, indicating promising antiseizure effects.

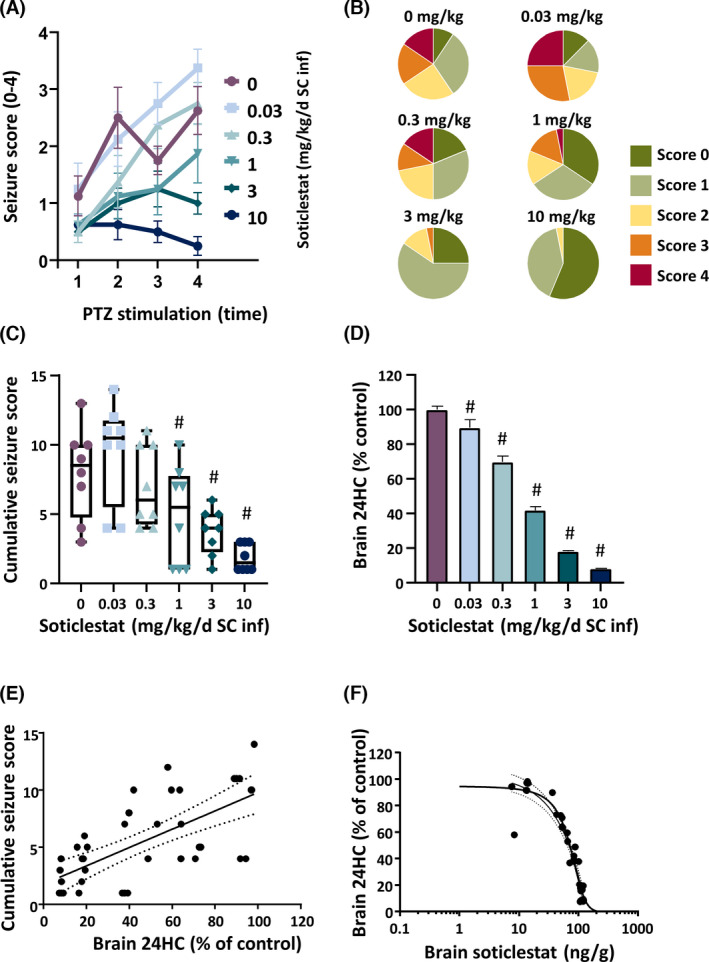

FIGURE 4.

Steady‐state soticlestat pharmacokinetics (PK)/pharmacodynamics (PD) and treatment effects on seizure progression in the mouse pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) kindling model. To investigate a steady‐state PK/PD relationship, soticlestat treatment was maintained through subcutaneous infusion over the study period (SC inf). (A) Effects of soticlestat on the progression of seizure severity over the four PTZ stimulations (.03, .3, 1, 3 and 10 mg/kg/day SC inf). The vehicle treatment is indicated as 0 mg/kg soticlestat. (B) Distribution of the Racine scores obtained over the total experiment period. (C) Cumulative seizure scores obtained over the total experimental period. #p < .025 compared to the vehicle‐controlled group (one‐tailed Williams test). (D) Brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol (24HC)‐lowering effects evaluated at the study endpoint. #p < .025 compared to the vehicle‐controlled group (one‐tailed Williams test). (E) Correlation between brain 24HC‐lowering and antiseizure effects of soticlestat. The dashed lines define the 95% confidence band in linear regression. (F) Correlation between brain 24HC lowering and brain soticlestat levels determined at the study endpoint. The dashed lines define the 95% confidence band in nonlinear regression

Figure 4D shows the effects of soticlestat on the brain level of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol at the study endpoint. Soticlestat significantly reduced 24S‐hydroxycholesterol levels in the brain at all doses in the experiment (p < .025, one‐tailed Williams' test). The reduction of brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol at the dose of 10 mg/kg reached 92%, implying that the enzyme activity of CH24H was inhibited almost completely. Statistical significance was revealed in the association between the cumulative seizure scores and the 24S‐hydroxycholesterol‐lowering effects (Figure 4E; r = .682). The data suggested that the effects of soticlestat on kindling acquisition were associated with CH24H enzyme inhibition.

We also confirmed that the 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering was strongly correlated with brain levels of soticlestat (Figure 4F; r = −.963). The plasma levels of soticlestat at 10 mg/kg were 28.6 ± 15.6 ng/ml, indicating that a more effective exposure was sustained than the same dose with bolus administration (Figure 3A).

These observations prompted us to test whether the robust CH24H inhibition through SC inf can protect mice against acutely evoked PTZ convulsions more effectively than the condition in bolus administration (Table 1). Following 2 weeks of soticlestat infusion, mice underwent PTZ seizure testing (80 mg/kg ip). Following the PTZ testing, brain levels of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol were measured. The reduction rate in the 1‐mg/kg SC inf and 10‐mg/kg SC inf groups were approximately 50% and 90% from the control group, respectively (Table S4). The numbers of mice protected per test were one of nine (vehicle), zero of eight (1 mg/kg SC inf), and two of nine (10 mg/kg SC inf; Table S4). The proportion in absence of seizures was apparently independent from 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering. Finally, the potential effects of soticlestat on kindled seizures were examined in corneally kindled mice. Fully kindled mice were treated with soticlestat (30 mg/kg, POQD) for 5 consecutive days, while kindling stimulus was maintained each day. Notable differences were not found in the proportion protected between the vehicle‐treated control group and the treatment group at any point during the study (Table S5), suggesting that soticlestat does not suppress already established kindled seizures.

4. DISCUSSION

In the present study, soticlestat was characterized in well‐established animal models of seizure. The data shown in this study suggest that inhibition of CH24H, an enzyme little studied in the context of epilepsy, exerts anticonvulsive benefits in a manner distinct from that of conventional seizure medications. In our panel of acute seizure models, soticlestat was found ineffective in MES, 6‐Hz, and scPTZ models (Table 1). However, soticlestat's anticonvulsive efficacy was detected in the audiogenic seizure and kindling acquisition models (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). Interestingly, soticlestat had little impact on the wild‐running behavior of Frings mice triggered by sound stimulation (Figure 1B). In contrast, it clearly suppressed development of TE in that model (Figure 1C). The lack of effects on early stage seizures was also observed in the model of kindling development. Soticlestat retarded kindling acquisition without altering AD duration (Figure 2). This suggests that the kindling delay by soticlestat was independent of focal seizure activity in the amygdala and may be attributed to modification of seizure progression.

These observations have led to the hypothesis that soticlestat has therapeutic potential to modify the process of secondary generalization, which is a common underlying mechanism in audiogenic seizures and kindling acquisition. In contrast, the seizure models that did not respond to soticlestat treatment, MES, scPTZ, and 6‐Hz, do not have a component of secondary generalization. In support of this hypothesis, fully kindled mice no longer responded to soticlestat (Table S5). The neuroanatomical architecture of seizure origin and propagation might provide insight into the mechanism by which soticlestat shows its anticonvulsive effects. Striatum has a higher expression of CH24H protein relative to other brain areas, 24 , 37 and its circuitry is known to be involved in secondary generalization of seizures. 43 The regional distribution of CH24H expression is of interest for future studies to clarify pathologic brain regions that give rise to secondary generalization.

To date, 24S‐hydroxycholesterol has been implicated in diverse biological functions. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 44 It is likely that the pharmacological mechanism of CH24H inhibition involves multiple molecular pathways. For example, one of the multiple mechanisms relevant to kindling epileptogenesis is TrkB signalling, 45 in which CH24H has been implicated. 19 Another interesting example is positive allosteric modulation of NMDA receptors by 24S‐hydroxycholesterol. 13 Further investigation is required to understand the exact role 24S‐hydroxycholesterol plays in seizure progression.

This study was also intended to shed light on translational aspects of CH24H inhibitor as a potential epilepsy medication in line with our previous findings. 24 In the PTZ‐kindling model, we demonstrated that soticlestat effects on seizure progression were associated with brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol lowering (Figure 4C–E). 24S‐Hydroxycholesterol lowering is considered a specific PD biomarker of CH24H inhibition, which is closely associated with soticlestat brain exposure (Figure 4F). It has already been established as a clinical PD marker of CH24H inhibition, as the plasma level directly reflects that in the brain. 25 , 46 At the maximum level of CH24H inhibition, soticlestat yielded a 75% decrease in seizure severity (Figure 4C,D), whereas no impairment in motor coordination was observed. 24 To obtain a detectable level of anticonvulsive efficacy, we propose it is necessary to reduce brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol by approximately 60%. This condition yielded 40% reduction in seizure severity in the PTZ‐kindling model (Figure 4C,D). It should be noted that this is a clinically achievable level of CH24H inhibition based on clinical data. 25 , 26 The data shown in this study serve as a bridge linking efficacy data in animal models to the dose setting in clinical trials. Despite the growing list of ASMs, a substantial population of patients do not always achieve satisfactory seizure control, highlighting the need for discovery work on treatments with novel mechanisms of action. 47 This unmet need is even more disparate in treatment‐resistant epilepsies such as developmental and epileptic encephalopathy (DEE). 48 To our best knowledge, CH24H inhibition has never been investigated as a therapeutic option for epilepsy. With its novel mechanism of action, soticlestat could constitute a new and novel class of ASM for the treatment of DEE.

In summary, the present study characterizes the anticonvulsive property of soticlestat in conventional seizure models. The data collectively suggest that it is potentially a novel class of epilepsy drug. We propose that the therapeutic mechanism of soticlestat is a modification of secondary generalization of seizures through reduction of brain 24S‐hydroxycholesterol. Now that oxysterol is implicated in a number of biological functions, further studies both in preclinical and clinical settings will shed more light on this brain‐specific mechanism of cholesterol metabolism.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

T.N., S.F., S.H., M.M., E.S., S.W., and S.K. are either current or former employees of Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited. C.S.M. and H.S.W have no competing interests to declare.

Supporting information

App S1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Thomas Hedberg (Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited) for comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited.

Nishi T, Metcalf CS, Fujimoto S, Hasegawa S, Miyamoto M, Sunahara E, et al. Anticonvulsive properties of soticlestat, a novel cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase inhibitor. Epilepsia. 2022;63:1580–1590. 10.1111/epi.17232

REFERENCES

- 1. Pfrieger FW. Outsourcing in the brain: do neurons depend on cholesterol delivery by astrocytes? BioEssays. 2003;25:72–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dietschy JM, Turley SD. Thematic review series: Brain lipids. Cholesterol metabolism in the central nervous system during early development and in the mature animal. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:1375–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Borroni MV, Vallés AS, Barrantes FJ. The lipid habitats of neurotransmitter receptors in brain. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1858;2016:2662–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lund EG, Xie C, Kotti T, Turley SD, Dietschy JM, Russell DW. Knockout of the cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase gene in mice reveals a brain‐specific mechanism of cholesterol turnover. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:22980–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xie C, Lund EG, Turley SD, Russell DW, Dietschy JM. Quantitation of two pathways for cholesterol excretion from the brain in normal mice and mice with neurodegeneration. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1780–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith LL, Ray DR, Moody JA, Wells JD, Van Lier JE. 24‐Hydroxycholesterol levels in human brain. J Neurochem. 1972;19:899–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Papassotiropoulos A, Lutjohann D, Bagli M, Locatelli S, Jessen F, Buschfort R, et al. 24S‐Hydroxycholesterol in cerebrospinal fluid is elevated in early stages of dementia. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:27–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leoni V, Mariotti C, Tabrizi SJ, Valenza M, Wild EJ, Henley SM, et al. Plasma 24S‐hydroxycholesterol and caudate MRI in pre‐manifest and early Huntington's disease. Brain. 2008;131:2851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Leoni V, Caccia C. Oxysterols as biomarkers in neurodegenerative diseases. Chem Phys Lipids. 2011;164:515–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lehmann JM, Kliewer SA, Moore LB, Smith‐Oliver TA, Oliver BB, Su JL, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3137–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Umetani M, Domoto H, Gormley AK, Yuhanna IS, Cummins CL, Javitt NB, et al. 27‐Hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous SERM that inhibits the cardiovascular effects of estrogen. Nat Med. 2007;13:1185–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang Y, Kumar N, Crumbley C, Griffin PR, Burris TP. A second class of nuclear receptors for oxysterols: regulation of RORalpha and RORgamma activity by 24S‐hydroxycholesterol (cerebrosterol). Biochem Biophys Acta. 2010;1801:917–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Paul SM, Doherty JJ, Robichaud AJ, Belfort GM, Chow BY, Hammond RS, et al. The major brain cholesterol metabolite 24(S)‐hydroxycholesterol is a potent allosteric modulator of N‐methyl‐D‐aspartate receptors. J Neurosci. 2013;33:17290–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tajima N, Xiaoyan L, Taniguchi M, Kato N. 24S‐Hydroxycholesterol alters activity of large‐conductance Ca(2+)‐dependent K(+) (slo1 BK) channel through intercalation into plasma membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2019;1864:1525–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Qi X, Liu H, Thompson B, McDonald J, Zhang C, Li X. Cryo‐EM structure of oxysterol‐bound human Smoothened coupled to a heterotrimeric G(i). Nature. 2019;571:279–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Alexandrov P, Cui JG, Zhao Y, Lukiw WJ. 24S‐Hydroxycholesterol induces inflammatory gene expression in primary human neural cells. NeuroReport. 2005;16:909–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Noguchi N, Saito Y, Urano Y. Diverse functions of 24(S)‐hydroxycholesterol in the brain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2014;446:692–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nury T, Zarrouk A, Mackrill JJ, Samadi M, Durand P, Riedinger JM, et al. Induction of oxiapoptophagy on 158N murine oligodendrocytes treated by 7‐ketocholesterol‐, 7beta‐hydroxycholesterol‐, or 24(S)‐hydroxycholesterol: protective effects of alpha‐tocopherol and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA; C22:6 n‐3). Steroids. 2015;99:194–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sodero AO, Weissmann C, Ledesma MD, Dotti CG. Cellular stress from excitatory neurotransmission contributes to cholesterol loss in hippocampal neurons aging in vitro. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32:1043–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lund EG, Guileyardo JM, Russell DW. cDNA cloning of cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase, a mediator of cholesterol homeostasis in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:7238–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mast N, Anderson KW, Johnson KM, Phan TTN, Guengerich FP, Pikuleva IA. In vitro cytochrome P450 46A1 (CYP46A1) activation by neuroactive compounds. J Biol Chem. 2017;292:12934–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mast N, Saadane A, Valencia‐Olvera A, Constans J, Maxfield E, Arakawa H, et al. Cholesterol‐metabolizing enzyme cytochrome P450 46A1 as a pharmacologic target for Alzheimer's disease. Neuropharmacology. 2017;123:465–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mast N, Verwilst P, Wilkey CJ, Guengerich FP, Pikuleva IA. In Vitro activation of cytochrome P450 46A1 (CYP46A1) by efavirenz‐related compounds. J Med Chem. 2019;63:6477–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nishi T, Kondo S, Miyamoto M, Watanabe S, Hasegawa S, Kondo S, et al. Soticlestat, a novel cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase inhibitor shows a therapeutic potential for neural hyperexcitation in mice. Sci Rep. 2020;10:17081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang S, Chen G, Merlo Pich E, Affinito J, Cwik M, Faessel H. Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, bioavailability and food effect of single doses of soticlestat in healthy subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;87:4354–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Halford JJ, Sperling MR, Arkilo D, Asgharnejad M, Zinger C, Xu R, et al. A phase 1b/2a study of soticlestat as adjunctive therapy in participants with developmental and/or epileptic encephalopathies. Epilepsy Res. 2021;174:106646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sierksma AS, de Nijs L, Hoogland G, Vanmierlo T, van Leeuwen FW, Rutten BP, et al. Fluoxetine treatment induces seizure behavior and premature death in APPswe/PS1dE9 mice. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51:677–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Halford RW, Russell DW. Reduction of cholesterol synthesis in the mouse brain does not affect amyloid formation in Alzheimer's disease, but does extend lifespan. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3502–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hawkins NA, Jurado M, Thaxton TT, Duarte SE, Barse L, Tatsukawa T, et al. Soticlestat, a novel cholesterol 24‐hydroxylase inhibitor, reduces seizures and premature death in Dravet syndrome mice. Epilepsia. 2021;62(11):2845–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wilcox KS, West PJ, Metcalf CS. The current approach of the Epilepsy Therapy Screening Program contract site for identifying improved therapies for the treatment of pharmacoresistant seizures in epilepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2020;166:107811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Toman JE, Swinyard EA, Goodman LS. Properties of maximal seizures, and their alteration by anticonvulant drugs and other agents. J Neurophysiol. 1946;9:231–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Everett GM, Richards RK. Comparative anticonvulsive action of 3,5,5‐trimethyloxazolidine‐2,4‐dione (Tridione), dilantin and phenobarbital. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1944;81:402–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Barton ME, Klein BD, Wolf HH, White HS. Pharmacological characterization of the 6 Hz psychomotor seizure model of partial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2001;47:217–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Frings H, Frings M. Development of strains of albino mice with predictable susceptibilities to audiogenic seizures. Science. 1953;117:283–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Goddard GV, McIntyre DC, Leech CK. A permanent change in brain function resulting from daily electrical stimulation. Exp Neurol. 1969;25:295–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mason CR, Cooper RM. A permanent change in convulsive threshold in normal and brain‐damaged rats with repeated small doses of pentylenetetrazol. Epilepsia. 1972;13:663–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Yutuc E, Angelini R, Baumert M, Mast N, Pikuleva I, Newton J, et al. Localization of sterols and oxysterols in mouse brain reveals distinct spatial cholesterol metabolism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117:5749–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Skradski SL, White HS, Ptácek LJ. Genetic mapping of a locus (mass1) causing audiogenic seizures in mice. Genomics. 1998;49:188–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Han JY, Lee HJ, Lee YM, Park J. Identification of missense ADGRV1 mutation as a candidate genetic cause of familial febrile seizure 4. Children (Basel). 2020;7(9):144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Bertram E. The relevance of kindling for human epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2007;48:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McIntyre DC, Gilby KL. Mapping seizure pathways in the temporal lobe. Epilepsia. 2008;49(Suppl 3):23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Dhir A. Pentylenetetrazol (PTZ) kindling model of epilepsy. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Brodovskaya A, Kapur J. Circuits generating secondarily generalized seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2019;101:106474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raccosta L, Fontana R, Maggioni D, Lanterna C, Villablanca EJ, Paniccia A, et al. The oxysterol‐CXCR2 axis plays a key role in the recruitment of tumor‐promoting neutrophils. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1711–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. He X‐P, Kotloski R, Nef S, Luikart BW, Parada LF, McNamara JO. Conditional deletion of TrkB but not BDNF prevents epileptogenesis in the kindling model. Neuron. 2004;43:31–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bjorkhem I, Lutjohann D, Diczfalusy U, Stahle L, Ahlborg G, Wahren J. Cholesterol homeostasis in human brain: turnover of 24S‐hydroxycholesterol and evidence for a cerebral origin of most of this oxysterol in the circulation. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1594–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Löscher W, Potschka H, Sisodiya SM, Vezzani A. Drug resistance in epilepsy: clinical impact, potential mechanisms, and new innovative treatment options. Pharmacol Rev. 2020;72:606–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Strzelczyk A, Schubert‐Bast S. Therapeutic advances in Dravet syndrome: a targeted literature review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2020;20:1065–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

App S1