Abstract

The circumscription and composition of the Hyaloscyphaceae are controversial and based on poorly sampled or unsupported phylogenies. The generic limits within the hyaloscyphoid fungi are also very poorly understood. To address this issue, a robust five-gene Bayesian phylogeny (LSU, RPB1, RPB2, TEF-1α, mtSSU; 5521 bp) with a focus on the core group of Hyaloscyphaceae and Arachnopezizaceae is presented here, with comparative morphological and histochemical characters. A wide representative sampling of Hyaloscypha supports it as monophyletic and shows H. aureliella (subgenus Eupezizella) to be a strongly supported sister taxon. Reinforced by distinguishing morphological features, Eupezizella is here recognised as a separate genus, comprising E. aureliella, E. britannica, E. roseoguttata and E. nipponica (previously treated in Hyaloscypha). In a sister group to the Hyaloscypha-Eupezizella clade a new genus, Mimicoscypha, is created for three seldom collected and poorly understood species, M. lacrimiformis, M. mimica (nom. nov.) and M. paludosa, previously treated in Phialina, Hyaloscypha and Eriopezia, respectively. The Arachnopezizaceae is polyphyletic, because Arachnoscypha forms a monophyletic group with Polydesmia pruinosa, distant to Arachnopeziza and Eriopezia; in addition, Arachnopeziza variepilosa represents an early diverging lineage in Hyaloscyphaceae s.str. The hyphae originating from the base of the apothecia in Arachnoscypha are considered anchoring hyphae (vs a subiculum) and Arachnoscypha is excluded from Arachnopezizaceae. A new genus, Resinoscypha, is established to accommodate Arachnopeziza variepilosa and A. monoseptata, originally described in Protounguicularia. Mimicoscypha and Resinoscypha are distinguished among hyaloscyphoid fungi by long tapering multiseptate hairs that are not dextrinoid or glassy, in combination with ectal excipulum cells with deep amyloid nodules. Unique to Resinoscypha is cyanophilous resinous content in the hairs concentrated at the apex and septa. Small intensely amyloid nodules in the hairs are furthermore characteristic for Resinoscypha and Eupezizella. To elucidate species limits and diversity in Arachnopeziza, mainly from Northern Europe, we applied genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition (GCPSR) using analyses of individual datasets (ITS, LSU, RPB1, RPB2, TEF-1α) and comparative morphology. Eight species were identified as highly supported and reciprocally monophyletic. Four of these are newly discovered species, with two formally described here, viz. A. estonica and A. ptilidiophila. In addition, Belonium sphagnisedum, which completely lacks prominent hairs, is here combined in Arachnopeziza, widening the concept of the genus. Numerous publicly available sequences named A. aurata represent A. delicatula and the confusion between these two species is clarified. An additional four singletons are considered to be distinct species, because they were genetically divergent from their sisters. A highly supported five-gene phylogeny of Arachnopezizaceae identified four major clades in Arachnopeziza, with Eriopezia as a sister group. Two of the clades include species with a strong connection to bryophytes; the third clade includes species growing on bulky woody substrates and with pigmented exudates on the hairs; and the fourth clade species with hyaline exudates growing on both bryophytes and hardwood. A morphological account is given of the composition of Hyaloscyphaceae and Arachnopezizaceae, including new observations on vital and histochemical characters.

Citation: Kosonen T, Huhtinen S, Hansen K. 2021. Taxonomy and systematics of Hyaloscyphaceae and Arachnopezizaceae. Persoonia 46: 26–62. https://doi.org/10.3767/persoonia.2021.46.02.

Keywords: Arachnoscypha, epibryophytic, genealogical species, Helotiales, subiculum, type studies

INTRODUCTION

Helotiales is one of the remaining unsolved pieces in the great puzzle of Leotiomycetes systematics. Depending on the taxonomic concept, the number of recognised species ranges from c. 2 360 (Baral 2016) to 3 881 (Kirk et al. 2008). There are no recent speculations on the total number of existing species, but e.g., Hawksworth (2001) gives an estimate of c. 70 000 species. Members of Helotiales are morphologically very variable and exhibit saprobic, parasitic as well as mycorrhizal life strategies. Hyaloscyphaceae in the traditional wide sense (Nannfeldt 1932) is the largest and most diverse family in the order (Kirk et al. 2008, Baral 2016 as Lineage D/Hyaloscyphaceae s.lat. with 68 genera and 673 species).

When Nannfeldt (1932) introduced the concept of Hyaloscyphaceae, it included three tribes, i.e., Arachnopezizeae, Hyaloscypheae and Lachneae, and altogether 13 genera. Nannfeldt emphasized especially the shape and structure of the excipular cells as a delimiting character at the family-level. Lachneae included species with lanceolate paraphyses and multiseptate granulate hairs and Arachnopezizeae species with a subiculum surrounding the apothecia. The species of Hyaloscypheae were not united by any unique combination of characters, but the majority of genera had cylindrical paraphyses and hairs of very diverse shapes and size.

Hyaloscyphaceae received growing attention during the following years and the systematics of the whole group was treated in studies by Dennis (1949, 1962, 1981), Raitviir (1970, 1987), Spooner (1987) and Svrček (1987). Although only a few monographs on hyaloscyphaceous genera have been published so far (Korf 1951b, Zhuang 1988, Huhtinen 1989), various authors contributed in documenting the diversity of the hairy Helotiales, e.g., Korf (e.g., 1951a, 1978, 1981, 2007), Haines (1974, 1989), Raschle (1977), Svrček (e.g., 1977, 1984, 1985), Korf & Kohn (1980), Raitviir & Sharma (1984), Baral & Krieglsteiner (1985), Spooner & Dennis (1985), Raitviir & Galán (1986), Baral (e.g., 1987, 1993), Huhtinen (e.g., 1987a, b, 1993a), Galán & Raitviir (1994, 2004), Cantrell & Hanlin (1997), Hosoya & Otani (1997), Raitviir & Huhtinen (1997), Leenurm et al. (2000), Zhuang (2000), Raitviir (2001), Quijada et al. (2014), and Baral & Rämä (2015). The number of recognised genera today is c. 70 and the number of species c. 1 000 (Kirk et al. 2008, Baral 2016).

There were no major revisions to the higher-level systematics until the 21st century. In his revised synopsis of the Hyaloscyphaceae s.str., Raitviir (2004) concluded that the morphological differences between the core members of the two largest tribes, Hyaloscypheae and Lachneae were ‘strictly contrasting’. With evidence on the ultra-structural differences in the hair wall layers (Leenurm et al. 2000) and the first phylogenetic analyses of the ITS region available (Cantrell & Hanlin 1997), Raitviir (2004) emended Hyaloscyphaceae to conform to the tribe Hyaloscypheae, and elevated Lachneae to the rank of family.

Recent multi-gene phylogenetic analyses have clearly shown that Hyaloscyphaceae sensu Raitviir (2004) is polyphyletic (Han et al. 2014, Johnston et al. 2019). The species occur in six or more clades, spread among other clades of Helotiales. These hyaloscyphoid clades correspond to emended tribes/sub-families/families, and to two newly described families (Arachnopezizaceae, Hyaloscyphaceae s.str., Lachnaceae, Pezizellaceae, Vandijckellaceae), as well as to unnamed groups (Raitviir 2004, Han et al. 2014, Crous et al. 2017, Johnston et al. 2019). The sampling of taxa or molecular characters is, however, very limited in the molecular studies (Han et al. 2014, Johnston et al. 2019), and the evolutionary history of these fungi is still poorly understood. In this study, we focus specifically on taxa closely related to Arachnopezizaceae, and the core group of Hyaloscyphaceae.

Arachnopezizaceae

Of the three original tribes, Arachnopezizeae comprised only a small number of species. Nannfeldt (1932) was unsure about the status of the tribe and gave only a provisional description. Korf (1951b) validated the tribe and stressed the significance of subiculum together with septate spores as the key morphological characters defining a natural group. Subiculum refers to the protruding hyphal elements forming an interconnected web-like structure on the substratum surrounding the apothecia (Kirk et al. 2008, see also Fig. 1). Korf (1951b) defined the tribe further as having septate hairs and partially thick-walled excipular cells. He included the genera Arachnopeziza, Eriopezia and Tapesina in Arachnopezizeae and placed Arachnoscypha in synonymy with Arachnopeziza. Dennis (1949, 1981) still recognised Arachnoscypha (for A. aranea), but did not comment on the close relationship between A. aranea and Arachnopeziza eriobasis shown by Korf (1951b). Raitviir (1970) removed Arachnopezizeae from Hyaloscyphaceae, emphasizing the similarities in the excipular structure to Durelloideae and Phialeoideae (Helotiaceae); he thought these three tribes should be placed in a separate family. Doing this, Raitviir gave less weight to the presence or absence of hairs in the overall systematics, suggesting that the presence of ‘true hairs’ is a polyphyletic character within Helotiales. Korf (1978) recognised Arachnopezizeae as a subfamily within Hyaloscyphaceae. At the same time he divided Arachnopezizoideae into two tribes: Arachnopezizeae including Arachnopeziza and provisionally Velutaria; and Polydesmiaeae, including Eriopezia, Parachnopeziza and Polydesmia. Later, a newly established genus Proliferodiscus was placed in Polydesmiaeae (Haines & Dumont 1983).

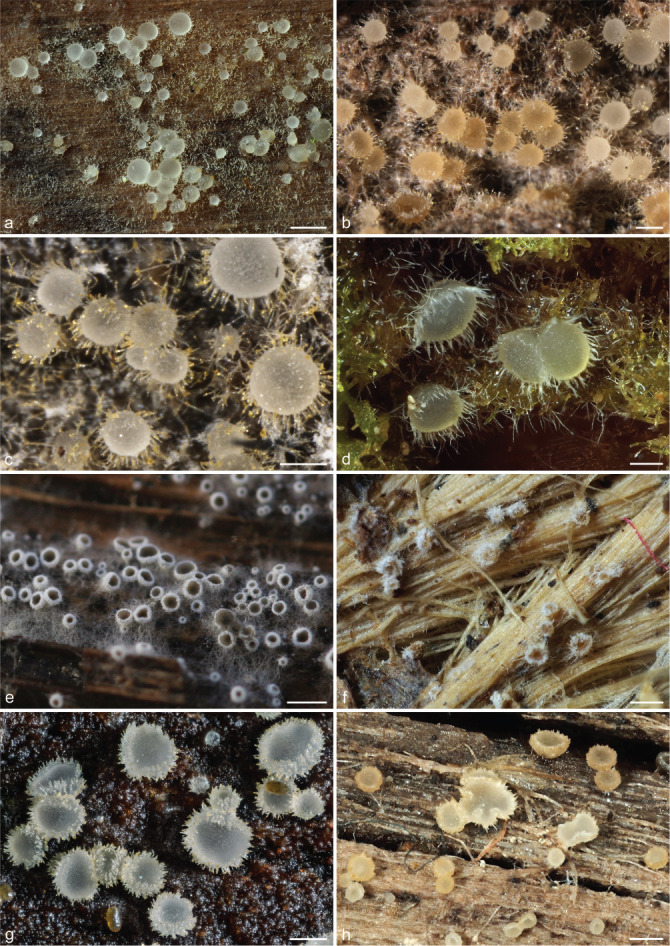

Fig. 1.

Examples of apothecia and habitats in Arachnopezizaceae, Arachnoscypha and Hyaloscyphaceae. a–c. Arachnopeziza leonina, showing hairs with crystals and subiculum; d. Arachnopeziza ptilidiophila; e. Eriopezia caesia; f. Arachnoscypha aranea†; g. Eupezizella aureliella; h. Olla transiens (a: T. Kosonen 7294; b: S. Huhtinen 16/42; c: S. Huhtinen 16/58; d: T. Kosonen 7289; e: T. Kosonen 7005; f: DPP-11788; g: DMS-9189563; h: T. Kosonen 7017). — Scale bars: a, e–f, h = 0.5 mm; b–d, g = 0.25 mm; † dried material. — Photos: a, d, f, h. N. Llerena; b–c. K. Hansen; e. T. Kosonen; g. J.H. Petersen.

Han et al. (2014) addressed the delimitation and relationship between Hyaloscyphaeae and Arachnopezizeae using phylogenetic analyses of the ITS, partial LSU rDNA, mtSSU and RPB2 sequences. Polydesmia and Proliferodiscus were suggested not to be close relatives of Arachnopeziza. Eventually, the rank of Arachnopezizeae was raised to its present status as a family including the genera Arachnopeziza, Arachnoscypha, Austropezia, Eriopezia and Parachnopeziza (Baral 2015). Although many species in Arachnopeziza are relatively conspicuous and new species have continued to be described, the number of Arachnopeziza sequences available is still relatively low as is the number of species sampled. A phylogenetic approach to clarify the family limits of Arachnopezizaceae, and the generic limits of the largest genus Arachnopeziza, is lacking.

Two different species have been interpreted as the type species of Arachnopeziza: A. aurata and A. aurelia. We follow here Korf (1951b: 132–133, 152) who concluded that A. aurata is the type species, as indicated by Saccardo (1884) when he combined Arachnopeziza as a subgenus in Belonidium. In his synopsis of the discomycete genera, Saccardo (1884) listed in general only one species per genus or subgenus that appear to have been selected as typical for them. Korf (1951b) also found it unfortunate if A. aurelia was to be considered the type species, because Fuckel (1872) excluded it from Arachnopeziza shortly after he described the genus. Several databases (e.g., MycoBank, Index Fungorum and Index Nominum Genericorum) list A. aurelia as the type species. Either they follow Clements & Shear (1931), who applied the ‘first species rule’ (A. aurelia is the first species listed by Fuckel (1870) in his description of Arachnopeziza), or Cannon et al. (1985) who first cite Korf (1951b) and then (erroneously!) list A. aurelia as the type species. The likeness of the epithets ‘aurelia’ and ‘aurata’ possibly contributed to that error.

Towards Hyaloscyphaceae sensu stricto

The disciplined use of histochemical methods and the reintroduction of vital taxonomy resulted in novel insights in inoperculate discomycetes systematics throughout the later part of the 20th century. The variation in iodine reactions and the significance of KOH pretreatment and its implications to taxonomy was observed and reviewed by Kohn & Korf (1975) and further explored by Baral (1987) resulting in the concept of hemiamyloidity. Nevertheless, the reactions in the cells produced by Melzer’s reagent were often reported inaccurately and an effort was made to distinguish between amyloid and dextrinoid reactions (Huhtinen 1987b, 1989, 1993b). The importance of studying living material was underlined by the works of Baral & Krieglsteiner (1985) and Baral (1992), showing the cells contained taxonomically valuable characters, changing or disappearing upon drying and/or using various reagents.

The type genus Hyaloscypha, as well as Phialina and Hamatocanthoscypha, were treated in detail by Huhtinen (1989). Many hyaloscyphaceous genera are characterised by a substance in the hair wall filling the space inside the hair partially or completely, giving it a glassy appearance. Several authors paid special attention to this character and proposed generic limits based on the morphology and chemical properties of the hairs (Raschle 1977, Korf & Kohn 1980, Huhtinen 1987b, 1989). Despite many advances, Hyaloscyphaceae remained essentially a combination of genera without a clear concept on their evolutionary relationship.

Combining the first phylogenetic results (Han et al. 2014) and vital taxonomy, Baral (2016) resurrected the family Pezizellaceae for 18 hyaloscyphaceous genera. The unifying morphological character is the frequent presence of vacuolar bodies (VB) in the cells of fresh specimens and a Chalara or similar asexual morph (Baral 2016). The family is supported as a distinct lineage in a recent study employing genome scale data (Johnston et al. 2019). In the systematic arrangement of the helotialean genera (Baral 2016), 26 genera representing c. 220 species were left in a restricted Hyaloscyphaceae, although the available phylogenetic evidence suggested it may still be polyphyletic (Han et al. 2014). As such, the family is delimited without any unique combination of characters, becoming distinguished rather by the lack of specific characters (i.e., the absence of Chalara asexual morph and VB’s). As a result, several taxa are included in Hyaloscyphaceae merely because no better placement is known.

Recent evidence shows, contrary to the traditional view, that at least some species of Urceolella and Cistella belong to a mono-phyletic clade Vandijckellaceae, distantly related to Hyaloscypha (Crous et al. 2017, Johnston et al. 2019). Han et al. (2014) proposed a very narrow concept of Hyaloscyphaceae, including only the genus Hyaloscypha. In their analyses of a dataset (the ‘inter-set’) including representatives from other families of Helotiales, Hyaloscypha formed a well-supported monophyletic group, resolved as a sister group to a clade including species of Olla, Hyalopeziza, Vibrisseaceae, Dermateaceae and Loramycetaceae. Johnston et al. (2019) showed that Amicodisca castanea and Dematioscypha are likely sisters to Hyaloscyphaceae s.str. However, many hyaloscyphoid genera have not been included in molecular phylogenetic studies and several might be non-monophyletic. Fehrer et al. (2018) provided some new samples, but most importantly broadened the view on the ecology of Hyaloscyphaceae by showing the connection between several well-known or new mycorrhizal-forming sterile, asexual or sexual morphs (including the Rhizoscyphus (Hymenoscyphus) ericae aggregate) and sexual Hyaloscypha species. The need to investigate the composition and circumscription of Hyaloscyphaceae is evident.

In the present study, we considerably expand the number of molecular characters, through the addition of sequence data from three protein-coding genes (RPB1, RPB2, TEF-1α), mitochondrial SSU and LSU rDNA, 5 521 bp in total. The ITS region was sequenced and used to aid in species identification or delimitation. With our observations of less known and novel species, together with phylogenetic analyses of sequences, we address the circumscription and relationships of Hyaloscyphaceae and Arachnopezizaceae. In Hyaloscyphaceae, we examine the delimitation of Hyaloscypha and the phylogenetic relationships of closely related taxa. In Arachnopezizaceae we investigate the phylogenetic placement and status of Arachnoscypha, and clarify species boundaries within Arachnopeziza, with a focus on Northern Europe, using genealogical concordance and comparative morphological studies, including the description of two new species and several new combinations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Material studied

This study is mainly based on samples collected by the authors in Estonia, Finland and Sweden during 2014–2018. These specimens are deposited in S and TUR. Several samples were collected as part of the project ‘Epibryophytic and lichenicolous fungi in Finland’ in 2003–2008 (Stenroos et al. 2010). In addition, we received both fresh and dry material from mycologists from Europe and North America (USA). From all of these, 69 samples were chosen for molecular phylogenetic study (Table 1). Fungarium material from CUP, H, K, NMNS, PRM, S, TAAM, TNS and TUR were studied.

Table 1.

Collections used in the molecular phylogenetic analyses, with voucher information and GenBank accession numbers. The number in parenthesis following a species name indicates the specific collection of a species (used in Fig. 2, 3, 4). Some GenBank sequences are re-identified by us and the names originally used in GenBank are listed after the taxon names (‘as’). Accession numbers in bold are sequences generated in this study. Sequences marked with ‘not used’ are available in GenBank but they were not used in the analyses. Unavailable sequence marked with an n-dash (–).

| Taxon | Voucher or culture1 | Origin, year, collector | GenBank accession number2 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | LSU | TEF-1α | RPB1 | RPB2 | mtSSU | |||

| Amicodisca svrcekii | TK7157 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen | MT231647 | MT231647 | MT434824 | MT216583 | MT228637 | MT231568 |

| A. virella | SBRH828 (S, TUR) | Netherlands, 2015, S. Helleman | MT231648 | MT231648 | MT254577 | MT216584 | MT228638 | MT231569 |

| Arachnopeziza araneosa (1) | ICMP 21731 | New Zealand, NA, NA | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| A. araneosa (2) | PDD 59117 /IMCP 22836 | New Zealand, 1991, P.R. Johnston | MH578555 | − | − | − | − | − |

| A. araneosa (3) | PDD 69076 /IMCP 22837 | New Zealand, 1994, P.R. Johnston | MH578556 | − | − | − | − | − |

| A. araneosa (4) | PDD 74085 /IMCP 22838 | New Zealand, 2001, P.R. Johnston & S. Whitton | MH578557 | − | − | − | − | − |

| A. aurata (1) | TUR 179456 | Denmark, 2007, J. Fournier | MT231649 | MT231649 | MT241676 | – | MT228639 | – |

| A. aurata (2) | CBS 116.54 | France, F. Mangenot | − | MH878241 | − | − | − | − |

| A. aurelia (1) | KUS-F51520 | Korea, 2007 | JN033409 | JN086712 | – | – | – | not used |

| A. aurelia (2) | CBS 117.54 | France, F. Mangenot | MH857261 | MH868796 | – | – | – | – |

| A. aurelia (3) | TNS-F-11211 / NBRC 102330 | Japan, 2003 | JN033435 | AB546937 | – | – | not used | not used |

| A. aurelia (4) | CBS 127675 | Japan, O. Izumi, single spore isolation | MH864618 | MH876056 | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (1) | TNS-F-12770 | Japan, 2004, T. Hosoya | JN033433 | JN086736 | – | – | JN086877 | JN086802 |

| A. delicatula (2) | TK7076 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231650 | MT231650 | MT254567 | MT216585 | MT228640 | MT231570 |

| A. delicatula (3) | JK14051801 (S, TUR) | USA, 2014, J. Karakehian | MT231651 | MT231651 | MT241687 | MT216586 | MT228641 | MT231571 |

| A. delicatula (4) | JP6655 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2013, J. Purhonen | MT231652 | MT231652 | MT241688 | MT216587 | MT228642 | – |

| A. delicatula (5) | TK7036 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231653 | MT231653 | MT241689 | MT216588 | MT228643 | MT231572 |

| A. delicatula (6) as ‘A. aurata’ | TNS-F-11212 | Japan, 2003, T. Hosoya | JN033436 | AB546936 | – | – | JN086881 | JN086806 |

| A. delicatula (7) | TK7115 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231654 | MT231654 | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (8) | TK7127 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231655 | MT231655 | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (9) | TK7152 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen | MT231656 | MT231656 | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (10) as ‘A. aurata’ | TENN 074424 | USA, SC, 2018, D. Newman & K. Fleming | MH558278 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (11) as ‘A. aurata’ | Isolate CL0301_4_1 | South Africa | KY228700 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (12) as ‘A. aurata’ | JHH 2210 (NYS) | USA, MA | U57496 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (13) as ‘A. aurata’ | CBS 127674 | Japan | MH864617 | MH876055 | – | – | – | – |

| A. delicatula (14) as ‘A. aurata’ | KUS-F52038 | South Korea, 2008 | JN033393 | JN086696 | – | – | not used | not used |

| A. estonica (1) | SH15/38 (S, TUR) | Estonia, 2015, S. Huhtinen | MT231657 | MT231657 | MT241693 | MT216589 | MT228644 | MT231573 |

| A. estonica (2) | TL210 (TUR) | Finland, 2005, T. Laukka | MT231658 | MT231658 | MT241677 | MT216590 | MT228645 | – |

| A. estonica (3) | TL245 (TUR) | Finland, 2005, T. Laukka | MT231659 | MT231659 | MT241678 | MT216591 | MT228646 | – |

| A. estonica (4) | TL253 (TUR) | Finland, 2005, T. Laukka | MT231660 | MT231660 | MT241679 | MT216592 | MT228647 | – |

| A. japonica (1) | SH06/03 (TUR) | Sweden, 2006, S. Huhtinen | MT231661 | MT231661 | MT241683 | MT216593 | MT228648 | – |

| A. japonica (2) | RI194 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, R. Ilmanen | MT231662 | MT231662 | MT241684 | MT216594 | MT228649 | – |

| A. japonica (3) | RI239 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, R. Ilmanen | MT231663 | MT231663 | MT241685 | MT216595 | MT228650 | – |

| A. japonica (4) | TL267 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, T. Laukka | MT231664 | MT231664 | MT241686 | MT216596 | MT228651 | – |

| A. leonina (1) | KH.15.23 (S, TUR) | Estonia, 2015, K. Hansen | MT231665 | MT231665 | MT254566 | MT216597 | MT228652 | MT231574 |

| A. leonina (2) | TK7101 (S, TUR) | Estonia, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231666 | MT231666 | MT241694 | MT216598 | MT228653 | MT231575 |

| A. leonina (3) | SH16/42 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen & S. Huhtinen | MT231667 | MT231667 | MT241695 | MT216599 | MT228654 | MT231576 |

| A. leonina (4) | JYV 11610 | Finland, 2013, J. Purhonen | MT277004 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. obtusipila (1) | TNS-F-12768 | Japan, 2006, T. Hosoya | JN033445 | JN086746 | – | – | JN086890 | JN086815 |

| A. obtusipila (2) | TNS-F-12769 | Japan, 2006, T. Hosoya | JN033446 | JN086747 | – | – | not used | not used |

| A. ptilidiophila (1) | TK7287 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2018, T. Kosonen | MT231668 | MT231668 | – | MT216600 | MT228655 | MT231577 |

| A. ptilidiophila (2) | TK7289 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2018, T. Kosonen | MT231669 | MT231669 | – | MT216601 | MT228656 | MT231578 |

| A. ptilidiophila (3) | TK7290 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2018, T. Kosonen | MT231670 | MT231670 | – | – | MT228657 | MT231579 |

| A. ptilidiophila (4) | AL51 (TUR) | Finland, 2005, A. Lesonen | MT231671 | MT231671 | MT241680 | MT216602 | MT228658 | – |

| A. sp. ‘a’ (1) | RI199 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, R. Ilmanen | MT435517 | MT435517 | MT241681 | MT216603 | MT228659 | – |

| A. sp. ‘a’ (2) | TL260 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, T. Laukka | MT231672 | MT231672 | MT241682 | MT216604 | MT228660 | – |

| A. sp. ‘a’ (3) as ‘uncultured fungus’ | OTU19 (environ.) | n/a | EF521221 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. ‘a’ (4) as ‘uncultured fungus’ | SG031 E06 (environ.) | n/a | KP889888 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. ‘a’ (5) as ‘uncultured fungus’ | OTU18 (environ.) | n/a | EF521220 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. ‘b’ (1) | TK7223 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2017, T. Kosonen | MT231673 | MT231673 | MT241696 | MT216605 | MT228661 | – |

| A. sp. ‘b’ (2) | TK7286 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2018, J. Purhonen | MT231674 | MT231674 | – | MT216606 | MT228662 | MT231580 |

| A. sp. (1) | L30_2013 /JCM 31955 | Japan, 2013, N. Nakamura | LC190976 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (2) as ‘uncultured fungus’ | c19 (environ.) | USA, NC | HM030576 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (3) as ‘Arachnopeziza sp.’ | PDD 112237 /ICMP 22830 | New Zealand, 2008, P.R. Johnston & P. White | MH578548 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (4) as ‘Helotiales’ | EXP-0411F | n/a | DQ914728 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (5) as ‘fungal sp.’ | Strain Mh859.5.8 | USA, NC | GQ996153 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (6) | PDD 112226 | New Zealand, 2018, P.R. Johnston | MH578523 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (7) | PDD 111524 /IMCP 22834 | Australia, 2009, P.R. Johnston | MH578552 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (8) | PDD 105290 /IMCP 22833 | New Zealand, 1994, P.R. Johnston | MH578551 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sp. (9) | PDD 105289 /IMCP 22832 | New Zealand, 2008, P.R. Johnston & P. White | MH578550 | – | – | – | – | – |

| A. sphagniseda (1) | RI226 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, R. Ilmanen | MT231675 | MT231675 | – | MT216607 | MT228663 | – |

| A. sphagniseda (2) | RI267 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, R. Ilmanen | MT231676 | MT231676 | – | MT216608 | – | – |

| A. sphagniseda (3) | TUR 178046 | Finland, 2006, S. Huhtinen | MT231677 | MT231677 | – | – | – | – |

| A. sphagniseda (4) | TL268 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, T. Laukka | MT231678 | MT231678 | – | – | – | – |

| A. trabinelloides (1) | GJO 0071771 | Austria, 2014, I. Wendelin | MT231679 | MT231679 | MT241697 | MT216609 | MT228664 | MT231581 |

| A. trabinelloides (2) | JK14030203 (S, TUR) | USA, MA, 2014, J. Karakehian | MT252825 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Arachnoscypha aranea (1) | SH15/44 (S) | Finland, 2015, S. Huhtinen | MT231680 | MT231680 | MT241698 | MT216610 | MT228665 | MT231582 |

| A. aranea (2) | TK7129 (S) | Sweden, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231681 | MT231681 | MT254568 | MT216611 | MT228666 | MT231583 |

| Ascocoryne sarcoides | NRRL 50072 | Chile, 2003 | not used | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Calycellina leucella | MP150937 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, M. Pennanen | MT231682 | MT231682 | MT241672 | MT216612 | MT228667 | – |

| Calycina citrina | CBS 139.62 | France | – | FJ176871 | – | – | FJ238354 | FJ176815 |

| Cenangiopsis quercicola | TAAM:178677 | Denmark | not used | KX090811 | KX090663 | KX090760 | KX090713 | – |

| Chlorociboria aeruginascens | TAAM:198512 | Germany | not used | LT158419 | KX090657 | KX090752 | KX090706 | – |

| C. aeruginosa | OSC 100056 | n/a | not used | AY544669 | DQ471053 | DQ471125 | DQ470886 | AY544734 |

| Ciborinia camelliae | ICMP 19812 | New Zealand, 2012, M. Denton-Giles | not used | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Cudoniella clavus | OSC 100054 | n/a | not used | DQ470944 | DQ471056 | DQ471128 | DQ470888 | DQ470992 |

| Cyathicula microspora | TF2006-BI (TUR) | Sweden, 2006 | EU940165 | EU940088 | – | – | EU940304 | EU940240 |

| Dematioscypha delicata | TK7123 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231683 | MT231683 | MT254569 | MT216613 | MT228668 | MT231584 |

| D. richonis | TK7082 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231684 | MT231684 | MT254576 | MT216614 | MT228669 | MT231585 |

| Dermea acerina | CBS 161.38 | Canada, 1936 | – | DQ247801 | DQ471091 | DQ471164 | DQ247791 | DQ247809 |

| Eriopezia caesia | TK7005 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2014, S. Huhtinen | MT231685 | MT231685 | MT241673 | MT216615 | MT228670 | MT231586 |

| Eupezizella aureliella (1) | TK7300 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen & S. Huhtinen | MT231686 | MT231686 | MT241699 | MT216616 | MT228671 | MT231587 |

| E. aureliella (2) | s.n. (S, TUR) | Finland, 2016, O. Miettinen | MT231687 | MT231687 | MT241700 | MT216617 | MT228672 | MT231588 |

| Hamatocanthoscypha straminella | JHP-15.170 (S, TUR) | Estonia, 2015, J.H. Petersen | MT231688 | MT231688 | MT254565 | MT216618 | MT228673 | MT231589 |

| Hyalopeziza alni | TK7210 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen | MT231689 | MT231689 | MT241701 | MT216619 | MT228674 | MT231590 |

| H. nectrioidea (1) | CBS 597.77 | Switzerland, 1973, P. Raschle | JN033381 | JN086684 | – | – | JN086836 | JN086761 |

| H. nectrioidea (2) | ES-2016.35 (S, TUR) | Switzerland, 2016, E. Stöckli | MT231690 | MT231690 | – | MT216620 | – | MT231591 |

| Hyaloscypha fuckelii (1) | AMFB1780 (S, TUR) | Belgium, 2016, B. Clesse | MT231691 | MT231691 | MT254571 | MT216621 | MT228675 | MT231592 |

| H. fuckelii (2) | TK7053 (S, TUR) | Finland, Åland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231692 | MT231692 | MT254572 | MT216622 | MT228676 | MT231593 |

| H. hepaticola | MK37 (TUR) | Finland, 2006, M. Kukkonen | JN943614 | EU940150 | – | JN985233 | EU940359 | EU940290 |

| H. herbarum | MP150945 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, M. Pennanen | MT231693 | MT231693 | MT241674 | MT216623 | MT228677 | MT231594 |

| H. intacta | TK7111 (S, TUR) | Estonia, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231694 | MT231694 | MT241675 | MT216624 | MT228678 | MT231595 |

| H. leuconica var. leuconica | TK7014 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2014, T. Kosonen | MT231695 | MT231695 | MT254573 | MT216625 | MT228679 | MT231596 |

| H. occulta as ‘Hyaloscypha sp.’ | TNS-F-31287 | Japan, 2007, T. Hosoya | JN033454 | JN086754 | – | – | JN086900 | JN086825 |

| H. usitata | TK7083 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231696 | MT231696 | MT254574 | MT216626 | MT228680 | MT231597 |

| H. vitreola | SH14/10 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2014, S. Huhtinen | MT231697 | MT231697 | MT254575 | MT216627 | MT228681 | MT231598 |

| Hyaloscyphaceae sp. | SH16/40 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen & S. Huhtinen | MT231698 | MT231698 | MT241702 | MT216628 | MT228682 | MT231599 |

| Hymenoscyphus caudatus | KUS-F52291 | Korea, 2008 | not used | JN086705 | – | – | JN086856 | JN086778 |

| H. fraxineus | CBS 133217 (MNHNL) | Luxembourg, 2012, G. Marson | not used | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| H. fructigenus | TNS-F-44644 | Japan, 2011, T. Hosoya | AB926057 | AB926144 | – | – | AB926189 | – |

| H. infarciens | CBS 122016 | France, 2001, G. Marson | not used | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Lachnum imbecille | TK7121 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231699 | MT231699 | MT254570 | MT216629 | MT228683 | MT231600 |

| Leotia lubrica | OSC 100001 | n/a | – | AY544644 | DQ471041 | DQ471113 | DQ470876 | AY544746 |

| Meria laricis | CBS 298.52 | Switzerland, 1952, E.Müller | MH857046 | DQ470954 | DQ842026 | DQ471146 | DQ470904 | DQ471002 |

| Mimicoscypha lacrimiformis (1) | SH17/8 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2017, S. Huhtinen | MT231700 | MT231700 | MT241703 | MT216630 | MT228684 | MT231601 |

| Mimicoscypha lacrimiformis (2) | TK7224 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2017, T. Kosonen | MT231701 | MT231701 | – | – | – | – |

| Mimicoscypha lacrimiformis (3) | SH17/6 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2017, S. Huhtinen | MT231702 | MT231702 | – | – | MT228685 | MT231602 |

| Mimicoscypha lacrimiformis (4) | SH17/7 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2017, S. Huhtinen | MT231703 | MT231703 | MT434823 | MT216631 | MT228686 | MT231603 |

| Mimicoscypha lacrimiformis (5) | KH.17.02 (S) | Sweden, 2017, K. Hansen | MT231704 | MT231704 | – | – | MT228687 | – |

| Neobulgaria pura | CBS 477.97 | USA, 1996, K. Cameron | – | FJ176865 | FJ238397 | FJ238434 | FJ238350 | – |

| Olla millepunctata | TK7167 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen | MT231705 | MT231705 | MT241705 | MT216632 | MT228688 | MT231604 |

| O. transiens | TK7125 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231706 | MT231706 | MT241706 | MT216633 | MT228689 | MT231605 |

| Pezicula carpinea | CBS 282.39 | Canada, 1932, H.S. Jackson | – | DQ470967 | DQ479932 | DQ842032 | DQ479934 | DQ471016 |

| Polydesmia pruinosa (1) | TK7139 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2015, T. Kosonen | MT231707 | MT231707 | MT241707 | MT216634 | MT228690 | MT231606 |

| P. pruinosa (2) | TK7236 (S, TUR) | Finland, 2017, T. Kosonen | MT231708 | MT231708 | MT241708 | – | MT228691 | MT231607 |

| Proliferodiscus sp. | KUS-F52660 | Korea, 2010 | not used | JN086730 | – | – | JN086871 | JN086796 |

| Resinoscypha variepilosa | SH16/41 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen & S. Huhtinen | MT231709 | MT231709 | MT241709 | MT216635 | MT228692 | MT231608 |

| Rustroemia firma | CBS 341.62 | France | – | DQ470963 | DQ471082 | DQ471155 | DQ470912 | DQ471010 |

| Sclerotinia sclerotiorum | 1980_UF70 | n/a | not used | genome | genome | genome | genome | genome |

| Scutoscypha fagina | TK7178 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2016, T. Kosonen | MT231710 | MT231710 | MT241710 | MT216636 | MT228693 | MT231609 |

| Solenopezia solenia | SH17/18 (S, TUR) | Sweden, 2017, S. Huhtinen | MT231711 | MT231711 | MT241711 | MT216637 | MT228694 | MT231610 |

| Trichopeziza sp. | s.n. (S, TUR) | Spain, 2016, J. Castillo | MT427744 | MT427744 | MT241712 | MT216638 | – | MT231611 |

| Vibrissea truncorum | CBS 258.91 | Canada, 1987, R.G. Thorn | not used | FJ176874 | FJ238405 | FJ238438 | FJ238356 | FJ190635 |

1 In personal collection numbers names have been shortened and only the initials are given. Herbaria are cited according to acronyms in Index Herbariorum (http://sweetgum.nybg.org/ih/).

2 ITS: Internal transcribed spacers (ITS1 and ITS2) and the 5.8S gene of the nrDNA; LSU: 28S large subunit of the nrRNA gene; TEF-1α: Translation elongation factor 1-alpha; RPB1: RNA polymerase II largest subunit; RPB2: RNA polymerase II second largest subunit.

Fungal cultures

Fresh collections were cultured on malt-agar plates in order to ensure ample living material for DNA extraction. Depending on the size of the collection, 4–10 small pieces of substratum (c. 2 × 2 mm) with fresh apothecia were cut under a dissecting microscope and placed on moist paper tissue of a slightly larger size. In cases where apothecia from different species were growing intermixed, the apothecia of the untargeted species were removed. A 50 mm Petri dish, half filled with growth media, was placed upside down on top of each piece of apothecia assembly. The growth media consisted of sterile ion-exchanged water with 2 % (w/v) malt, glucose, agar, 0.1 % peptone and 0.01 % chloramphenicol. Spore release was triggered by altering the air pressure inside the Petri dish by carefully lifting it partially for 1–2 s. After 12–24 h, the Petri dish was closed and sealed. Similar hyphal growth pattern, on the 4–10 plates made from one collection, was used as an indication of the target species being successfully isolated. Cultures were grown for 3–6 mo at room temperature prior to DNA extraction. We observed no asexual reproductive structures during the first 3 mo when cultures were under consistent observation. Fungal cultures will be deposited in the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (CBS-KNAW collection).

Morphological methods

The material was studied with Olympus BX53 and Nikon i80 microscopes with bright field optics. Measurements were made using a 1 000× magnification. Fresh samples were first studied in tap water. Other mounting media used were: Melzer’s reagent (MLZ), IKI solution (LUG), Cotton blue (CB), ammoniacal Congo red (CR) and c. 5 % potassium hydroxide (KOH). The formulas for reagents follow Huhtinen (1989). Large apothecia were cut in half or sectioned for mounting, whereas minute and fragile apothecia were squash mounted. Thirty discharged spores were measured, when possible, from each population. Dimensions were recorded subjectively at the accuracy of 0.1 μm. The mean spore Q values were calculated separately from the individual Q values. The total number of spores measured is given (n), followed by the number of populations used as a source. Spore sizes include 90 % of the measured variation; the smallest and the largest 5 % of the values are excluded, although the largest measured value is given in parentheses. Colours, when accurately described, are given according to Cailleux (1981). Line drawings were made using a drawing tube and when present, photographs of vital characters were used as an aid. The exclamation mark (!) indicates that we examined type or other original.

Molecular techniques

DNA was isolated from fresh mycelia scraped from the agar plates, or in cases of unsuccessful culturing from fresh or very recently dried apothecia. In the latter case, 10–30 apothecia were handpicked to a sterile Eppendorf tube. The material was shaken in a cell disrupter Mini-BeadBeaterTM (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, Oklahoma) with 1.2 mm disposable steel beads in a 2 mL screw-cap microvial, at 4 200 rpm for 20 s. If necessary, shaking was repeated once after allowing the sample to cool down for 2–3 min. Alternatively, fresh mycelia were ground in an Eppendorf tube with a pestle together with a tiny amount of sterilized sea sand. DNA was extracted using the DNeasy® Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen), following the standard protocol for fresh plant material. In the final step, the DNA extract was eluted with the provided elution buffer in a volume of 200 μL. A 1 : 10 dilution of the DNA with sterile DNase-free water was used as template for the polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The DNA extract from scanty specimens was (in the final step) eluted in only a volume of 100 μL or less, and without further dilution used for PCR. For a small (random) part of the material, DNA was extracted using the Promega Wizard® Genomic DNA purification kit, following the provided protocol for filamentous fungi. The brightness of ITS-LSU PCR bands was used as an initial indication of the concentration of the DNA that was diluted even further, if necessary, for subsequent reactions.

Six different gene regions were amplified: rDNA ITS1–5.8S–ITS2 and the D1–D2 regions of LSU, c. 1300–1400 bp; mitochondrial small subunit (mtSSU), regions U2–U6, c. 800–1000 bp; RNA polymerase I (RPB1), A–C region, c. 700 bp; RNA polymerase II (RPB2), 5–11 regions, c. 1800 bp; and translation elongation factor 1-alpha (TEF-1α), c. 1000–1300 bp. The respective primers used were: ITS1, ITS4, LR0R, LR3 and LR5 (White et al. 1990); mrSSU1 and mrSSU3R (Zoller et al. 1999); RPB1A, RPB1C (Matheny et al. 2002); 5F, 6F, 7R, 7F, 11aR (Liu et al. 1999) and both RPB2-9R (Taşkin et al. 2010, referred as ‘RPB2-9f’ in the article) and RPB2-9mR (ATY AAA TGD GCA ATN GTC ATR CG), a modification of the RPB2-9R primer; 526F, 2F, 1567R and 2218R (S. Rehner unpubl., Rehner & Buckley 2005) and EF–3AR (Taşkin et al. 2010). Generally, the gene regions were PCR amplified in one piece. If unsuccessful, the genes were PCR amplified in two or more overlapping pieces. A standard approach for the RPB2 and TEF-1α genes was to use primers 5F and 9mR (RPB2) and 526F and EF-3AR (TEF-1α). This resulted in strong target product without multiple bands in 80–90 % of the sampled species. PCR amplifications were done using IllustraTM Hot Start Mix RTG PCR beads (GE Healthcare, UK) in a volume of 25 μL. All PCR programs included an initial hot start at 95 °C for 5 min and a final incubation at 72 °C for 7 min. The actual cycles were as follows: ITS and LSU regions of rDNA: 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 45 s and extension at 72 °C for 1–1.5 min; for mtSSU the program was identical, except that the annealing was at 56 °C for 1 min; for RPB1: 35 cycles at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 52 °C with 1 °C increase every 5 s until 72 °C and extension at 72 °C for 1.5 min; for RPB2: 34–40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 55–58 °C for 1 min and extension at 72 °C 1 min with an increase of 1 s each cycle; for TEF-1α a touchdown program: 9 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 66 °C for 30 s with temperature reduced 1 °C every cycle and extension at 72 °C for 1 min followed by an additional 30–33 cycles with denaturation at 95 °C, annealing at 56 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min. PCR products were examined on 1 % agarose gel and either purified directly using ExoSap–IT (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to remove excess primers and nucleotides. In the case of multiple bands, the total volume of PCR was run on a 1.5 % agarose gel and the band of correct size was excised and retained using the Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen). Purified PCR products were sequenced by Macrogen Inc. (the Netherlands). The primers used for PCR (listed above) were also used for sequencing. Two internal primers were in addition used for sequencing long PCR products (> 1 000 bp), to produce multiple overlapping sequences.

Alignment, data-partitioning and phylogenetic analyses

Sequences were assembled and edited using Sequencher v. 4.10 (Gene Codes Corporation, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Nucleotide sequences were aligned manually using Se-Al v. 2.0a11 (Rambaut 2002). Each alignment of the protein-coding genes was translated to amino acids using MacClade v. 4.08 (Maddisson & Maddisson 2000) to verify the alignment and determine the intron positions. The introns were too variable to align unambiguously and were therefore excluded from the analyses. All gene regions were analysed using the nucleotides. Two multi-gene datasets were assembled:

the Helotiales dataset, to resolve the boundaries and relationships of Arachnopezizaceae and Hyaloscyphaceae (including also representatives of other Helotiales); and

the Arachnopezizaceae dataset, to delimit species and elucidate the relationships in Arachnopeziza (including Arachnopezizaceae s.str. as delimited from analyses of the Helotiales dataset).

Leotia lubrica was used as an outgroup for the Helotiales dataset based on its placement outside Helotiales in various studies (Spatafora et al. 2006, Johnston et al. 2019). Amicodisca virella was used as an outgroup for the Arachnopezizaceae dataset, based on our results from analyses of the Helotiales dataset. Arachnopeziza aurelia (TNS-F11211) was not included in the final multi-gene Arachnopezizaceae dataset, because of missing data (no RPB1 and TEF-1α sequences are available and the RPB2 sequence is short (716 bp) compared to our sequences) and because it in preliminary analyses was found to be divergent from the other species sampled by us. The combination of lack of characters and closely related species (occurring on a very long branch) resulted in loss of resolution in the backbone of the multi-gene Bayesian and ML phylogenies (in the relationships among the Arachnopeziza clades). Arachnopeziza obtusipila was included, despite missing similar data, because it is closely related to another taxon (A. leonina) and the impediment of the missing data appeared to have no (or less) effect on the analyses. For each dataset the single gene regions were analysed separately and combined. Each of the three protein coding gene regions (RPB1, RPB2 and TEF-1α) were analysed with two distinct partitions:

first and second codon positions; and

third codon positions.

The LSU rDNA and mtSSU were each analysed as one distinct partition. Thus, the combined five-gene datasets were analysed with eight partitions.

The ITS was too variable to align across Helotiales and it was therefore not included in the Helotiales dataset. For the Arachnopezizaceae dataset, the ITS sequences were alignable. Analyses of the six-gene dataset, including the ITS region, improved the support values for the Arachnopeziza leonina clade, but weakened the support values for some of the backbone nodes. Also, we observed that analyses including the ITS were very sensitive to minor, but equally justified alterations in the ITS alignment. As a result, we did not include the ITS in the combined Arachnopezizaceae dataset. Nevertheless, to provide further insight into the species and ecological diversity and geographical distributions of Arachnopeziza, a third dataset was assembled that included additional Arachnopeziza species and collections with only ITS and, if available, LSU sequences (from GenBank and our own data). For an improved alignment, no outgroup was included in the analyses of this dataset and the phylogenies were rooted along the branch leading to A. sphagniseda. The beginning and tail of the mtSSU sequences were highly variable and not possible to align, and were not included in the Helotiales or Arachnopezizaceae data-sets. Alignments of the combined five-gene Helotiales and Arachnopezizaceae datasets, and the more inclusive ITS-LSU alignment of Arachnopeziza, are available at TreeBASE under accession number S25441.

Individual and combined analyses of the six different gene regions were performed using Metropolis-coupled Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMCMC) in MrBayes v. 3.2.6 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003) and Maximum Likelihood-based inference (ML) in RAxML-HPC2 v. 8.2.10 (Stamatakis 2014). All analyses were run on CIPRES science Gateway (Miller et al. 2010). The Bayesian analyses were run in parallel using model jumping (/mixed models) (Ronquist et al. 2012), and with all parameter values, except branch length and tree topologies, unlinked. The analyses consisted of four parallel searches, with four chains each, initiated with random trees. For the single gene datasets the analyses were run for 5 M generations and the combined five-gene datasets for 10 M generations. The chains were sampled every 500 generations in the 5 M generation runs and every 1 K generations in the 10 M runs. A majority rule consensus tree was assembled and the posterior probabilities (PP) were calculated from the last 75 % of the posterior tree samples. The ML analyses used a GTRGAMMA model for the rate heterogeneity with all free model parameters estimated by the program. Maximum likelihood bootstrap analyses (ML-BP) were performed using 1 000 rapid bootstrap replicates from random starting trees, followed by a thorough ML search similarly using 1 000 replicates to find the best tree.

We applied the concept of Genealogical Concordance Phylogenetic Species Recognition (GCPSR) (Taylor et al. 2000) to delimit species in Arachnopeziza. To identify independent evolutionary lineages using genealogical concordance we employed two criteria based on Dettman et al. (2003):

the clade had to be present in the majority (3/4) of the single-gene phylogenies; and

the clade was well supported in at least one single-gene phylogeny (as judged by both PP ≥ 0.95 and ML-BP ≥ 75 %), and if its existence was not contradicted by any of the other single-gene phylogenies at the same level of support.

The ITS, LSU, RPB1, RPB2 and TEF-1α genealogies were visually compared to find concordance.

RESULTS

Sequences produced, congruence and data partitions

Altogether 346 sequences from 69 samples were produced in this study. GenBank accession numbers for the specific gene regions are listed in Table 1. In addition, 126 sequences of 28 samples were retrieved from GenBank. The concatenated datasets for Helotiales and Arachnopezizaceae contained 5 521 and 5 124 characters, respectively. The Arachnopeziza ITS-LSU dataset had 1 045 characters. All Bayesian analyses converged: the average standard deviation of split frequencies reached values below 0.01, except in the individual analysis of RPB2 in the Helotiales dataset, which reached a value of c. 0.013 after 5 M generations. In all analyses, the Potential Scale Reduction Factor values stabilized at 1.000. In the ML analyses of the combined Helotiales and Arachnopezizaceae datasets, the single best scoring trees were recovered with –InL = 73800.332097 and –InL = 18838.975670, respectively. In the ML analyses of the Arachnopeziza ITS-LSU dataset, the single best scoring tree was recovered with –InL = 3423.787414. Individual trees for each gene marker for both concatenated datasets were studied for conflicts. There were no supported (PP ≥ 0.95 and ML-BP ≥ 75 %) conflicts between the individual gene trees of the Helotiales dataset.

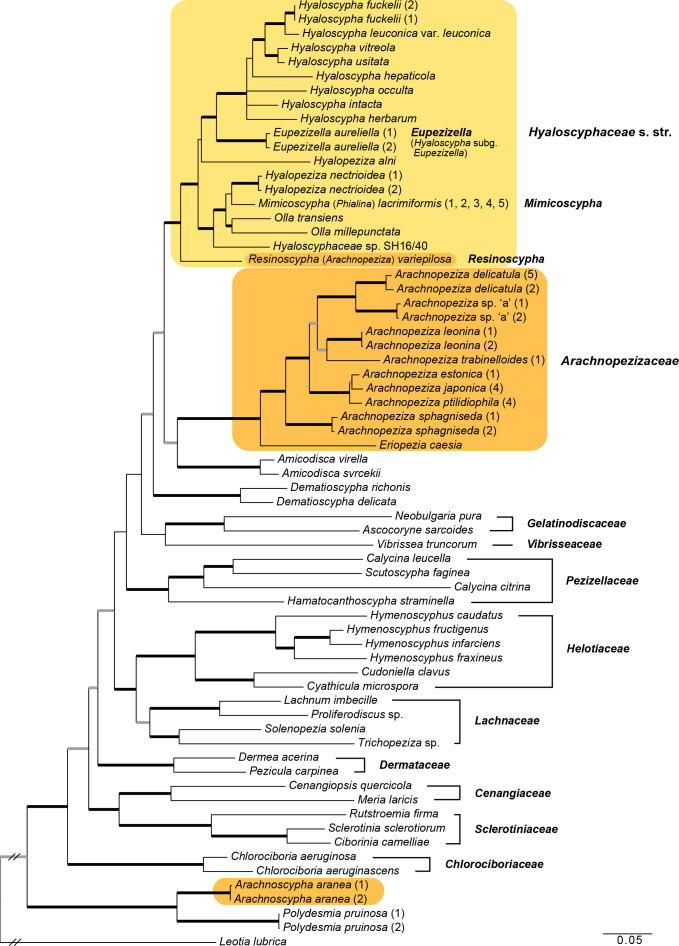

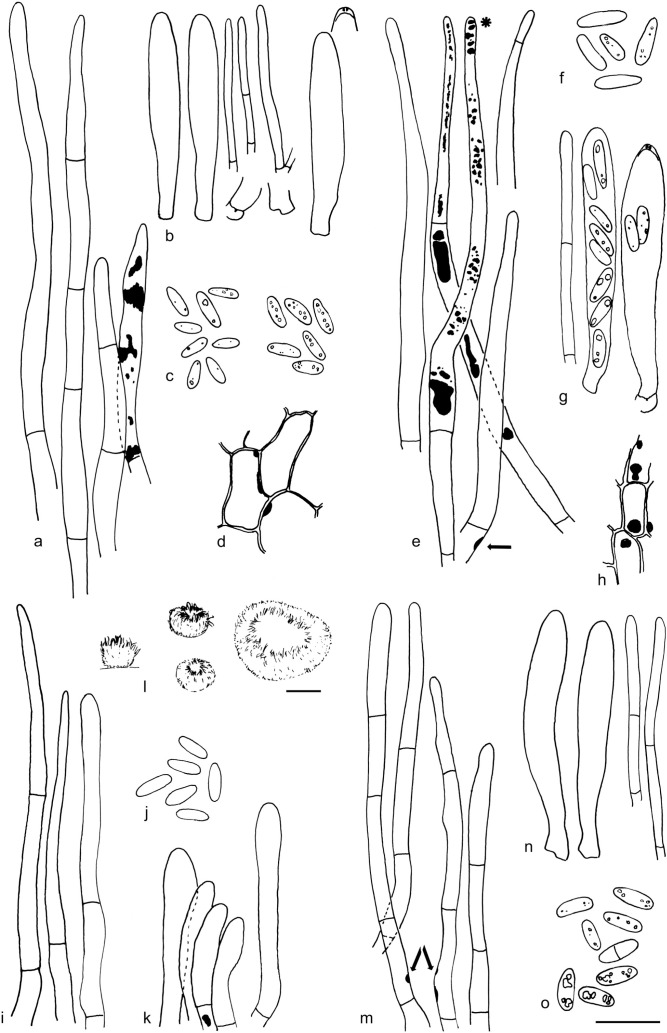

The major lineages and relationships of Arachnopezizaceae, Hyaloscyphaceae s.str. and related genera

Bayesian and ML analyses of the five-gene Helotiales dataset produced topologies with identical deeper branching patterns. The back-bone nodes are supported by Bayesian analysis (PP values ≥ 0.95, Fig. 2), except for two nodes that have low support (both PP 0.73) i.e., in the placement of Pezizellaceae, Vibrissea(ceae) and Gelatinodiscaceae. The Arachnopezizaceae is polyphyletic, because Arachnoscypha forms a highly supported monophyletic group with Polydesmia pruinosa as a sister group to the rest of the Helotiales (PP 1.00, ML-BP 91 %), very distant to Arachnopeziza and Eriopezia. Eight species of Arachnopeziza and Eriopezia caesia form a highly supported monophyletic group (PP 1.00, ML-BP 100 %). Arachnopeziza variepilosa is supported as a separate distinct lineage. Hyaloscyphaceae (Hyaloscypha and closely related taxa) is supported as a sister group to a clade of Arachnopezizaceae and Amicodisca in Bayesian analyses (PP 0.96), with Dematioscypha as a sister group to all of those (PP 0.96) (Fig. 2). The ML analysis, however, resolves Dematioscypha and Amicodisca as successive sister taxa to Hyaloscyphaceae, but without support (ML-BP below 50 %). The placement of Gelatinodiscaceae and Vibrissea differs likewise in the ML phylogeny, but also without support. The Hyaloscyphaceae s.str. here includes novel sequences of poorly understood hyaloscyphoid taxa. All other families, as represented here, are supported as monophyletic in both Bayesian and ML analyses, except Lachnaceae that is resolved as two successive sister lineages to members of Helotiaceae in the ML-analysis but without support (ML-BP 59 %). Members of Lachnaceae and Helotiaceae form a highly supported monophyletic group (PP 1.00, ML-BP 94 %) as do members of Cenangiaceae and Sclerotiniaceae (PP 1.00, ML-BP 94 %).

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships of Arachnopezizaceae (orange square) and Hyaloscyphaceae (yellow square) among members of Helotiales based on Bayesian analyses of combined LSU, RPB1, RPB2, TEF-1α and mtSSU loci. Arachnoscypha aranea and Resinoscypha variepilosa (orange squares) were previously treated in Arachnopezizaceae. Thick black branches received both Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥ 0.95 and maximum likelihood bootstrap value (ML-BP) ≥ 75 %. Thick grey branches received support by either PP ≥ 0.95 or ML-BP ≥ 75 %. The number in parenthesis after a species name refers to an exact collection (see Table 1).

Generic relationships in Hyaloscyphaceae s.str.

The nine selected species of Hyaloscypha form a highly supported monophyletic clade (Fig. 2). Hyaloscypha aureliella is strongly supported as a sister lineage to all other Hyaloscypha species (PP 1.00, ML-BP 99 %), confirming that it is distinct; Huhtinen (1989) recognised it within Hyaloscypha in subgenus Eupezizella. It is here accepted in the separate genus Eupezizella (see Taxonomy). The relationships within Hyaloscypha s.str. are not fully resolved (Fig. 2). Two species of Olla, O. transiens and O. millepunctata (type species of Olla), form a monophyletic group (PP 1.00, ML-BP 81 %). Two species of Hyalopeziza, H. alni and H. nectrioidea, do not form a monophyletic group. Our preliminary results on the type species of Hyalopeziza (H. ciliata) indicate that it belongs in Pezizellaceae (not shown) and that it is not closely related to any of the other sequenced Hyalopeziza species. Hyalopeziza alni forms a separate distinct lineage within Hyaloscyphaceae s.str., but its placement is without support. Hyalopeziza nectrioidea forms a monophyletic group with Olla and Mimicoscypha (Phialina) lacrimiformis. The relationships of M. lacrimiformis are resolved differently between the two analyses and with only low support from Bayesian PP and ML bootstrap analyses, but it is clearly distinct morphologically from Olla and from the two Hyalopeziza species (see Taxonomy) and therefore we erect a new genus Mimicoscypha for this taxon. Based on morphology this is not a species of Phialina. Other species of Phialina or Calycellina are placed in Pezizellaceae (Han et al. 2014, Baral 2016, Johnston et al. 2019).

A possible new species or genus constitutes a distinct lineage (Hyaloscyphaceae sp., SH 16/40), sister to the Mimicoscypha-Olla clade. Additional material is needed to fully understand and describe this taxon. Arachnopeziza variepilosa is highly supported as a sister group to all other Hyaloscyphaceae s.str. representatives. It is clearly distant from other species of Arachnopeziza and a new genus, Resinoscypha, is therefore created (Fig. 2, see Taxonomy).

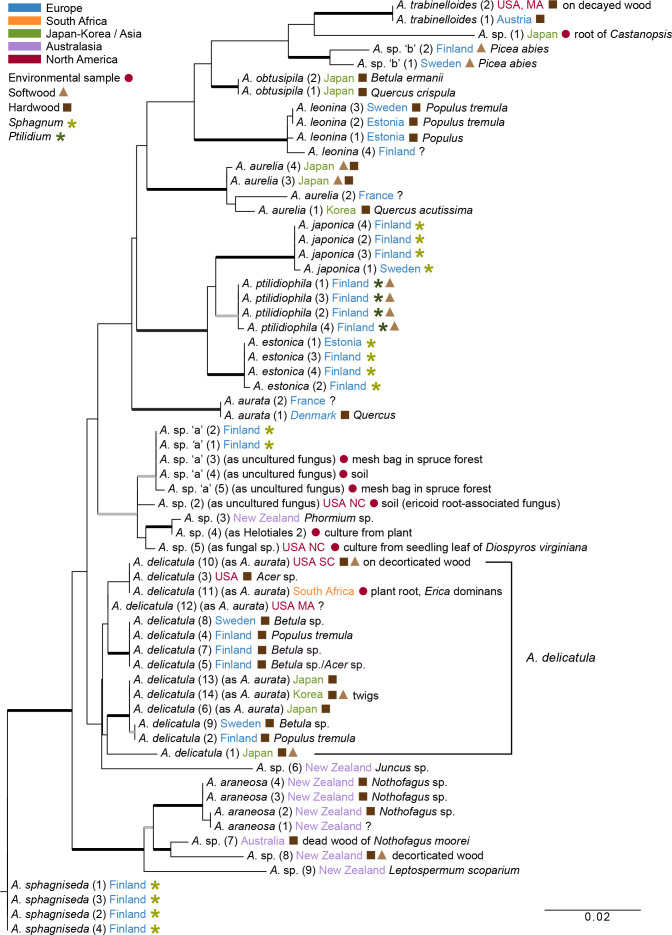

Phylogenetic species recognition and diversity in Arachnopeziza

Eight terminal independent evolutionary lineages were identified in Arachnopeziza, using the two grouping criteria for GCPSR (see Materials and Methods), and these are inferred as phylogenetic species (marked by a triangle on the node in Fig. 3). All of the species were strongly supported as monophyletic by Bayesian PP (≥ 0.95) and ML-BP (≥ 75 %) in at least two of the single gene trees (Table 2). Four of them present newly discovered species of which two are formally described in the present paper, A. estonica and A. ptilidiophila. Analyses of the LSU did not resolve A. delicatula and A. estonica as monophyletic, but their monophyly was not significantly contradicted in the LSU genealogies. Bayesian and ML analyses of the combined LSU, RPB1, RPB2, and TEF-1α data supported all eight species as monophyletic (PP 1.00, ML-BP 100 %). The monophyly of four putative species (A. araneosa, A. aurata, A. obtusipila and A. trabinelloides), represented by only single collections, could not be tested, but they were considered to be distinct because they were genetically divergent from their sisters (Fig. 3). ITS and LSU sequences were available in GenBank from one to three additional collections of these four species and our analyses of the taxon-expanded ITS-LSU dataset support them as monophyletic groups (Fig. 4). The two collections each of A. aurata (from Denmark and France), A. obtusipila (Japan) and A. trabinelloides (Austria and USA, MA) showed identical ITS and/or LSU sequences. Arachnopeziza delicatula showed internal phylogenetic structure in analyses of the five-gene dataset, with two subgroups: A. delicatula (4) and (5) (PP 1.00) and A. delicatula (2) and (6) (ML-BP 88 %) (Fig. 3), but these groupings were strongly contradicted among the single genealogies suggesting recent recombination within a single lineage/species. The A. delicatula populations sampled for multiple gene analyses were from three different continents, Japan, Northern Europe and USA, and did not show any geographical pattern.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree based on Bayesian analysis of the Arachnopezizaceae dataset (combined LSU, RPB1, RPB2, TEF-1α and mtSSU loci). Amicodisca virella was used as an outgroup in the analysis and for rooting the tree. Thick black branches received both Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥ 0.95 and maximum likelihood bootstrap value (ML-BP) ≥ 75 %. Thick grey branches received support by either PP ≥ 0.95 or ML-BP ≥ 75 %. The triangles at the nodes indicate eight species recognised by genealogical concordance phylogenetic species recognition. The number in parenthesis after a species name refers to an exact collection (see Table 1). Four clades are named for discussion.

Table 2.

Support values for Arachnopeziza species recognised by genealogical concordance in the analysis of individual gene regions and in the combined dataset (LSU, RPB1, RPB2, EF-1α and mtSSU3): Maximum Likelihood values (RAxML) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP). NA, only one or no sequences available. Limits of these species correspond to the nodes with triangles in Fig. 3.

| Species1 | ITS ML-BP / PP | LSU ML-BP / PP | RPB1 ML-BP / PP | RPB2 ML-BP / PP | TEF-1α ML-BP / PP | Combined five-gene data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. delicatula | 87 / 0.82 | –2 / – | 96 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. estonica | 100 / 1.00 | – / – | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 99 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. japonica | 100 / 1.00 | 95 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. leonina | 100 / 1.00 | 97 / 0.96 | 100 / 1.00 | 98 / 0.99 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. ptilidiophila | 97 / 0.68 | 64 / 0.84 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | NA | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. sphagniseda | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 99 / 1.00 | NA | NA | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. sp. ‘a’ | 99 / 1.00 | 77 / 0.84 | 97 / 1.00 | 92 / 1.00 | NA | 100 / 1.00 |

| A. sp. ‘b’ | 98 / 0.97 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 | 99 / 1.00 | 100 / 1.00 |

1 Support values not available for the following species represented by a single collection: A. aurata, A. araneosa, A. obtusipila and A. trabinelloides.

2 –, the clade was not resolved as monophyletic.

3 Support values based on mtSSU alone are not given due to the limited taxon sampling.

Fig. 4.

The best scoring maximum likelihood phylogeny of Arachnopeziza based on ITS-LSU. Thick black branches received both Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) ≥ 0.95 and maximum likelihood bootstrap value (ML-BP) ≥ 75 %. Thick grey branches received support by either PP ≥ 0.95 or ML-BP ≥ 75 %. The analyses were run without an outgroup. The tree was rooted on the branch leading to A. sphagniseda. All sequences are derived from ascomata or cultures derived from ascomata, unless marked as environmental samples. The number in parenthesis after a species name refers to an exact collection (see Table 1).

Bayesian and/or ML analyses of the taxon-expanded ITS-LSU dataset supported all of the species recognised using GCPSR or genetic divergence, except for A. delicatula (Fig. 4). In addition to the six collections included in our multi-gene analyses (Fig. 3), nine other A. delicatula collections were included in the ITS-LSU dataset. Six of these were retrieved from GenBank as A. aurata, but are for the time being referred to the A. delicatula lineage, because they had ITS (± LSU) sequences that were identical to ITS and LSU sequences of A. delicatula studied by us (Fig. 4). They include populations from four different continents, i.e., Northern Europe, Eastern North America, South Africa and East Asia. Arachnopeziza aurata, the type species of Arachnopeziza, forms a separate distinct lineage (Fig. 3, 4). Included in the ITS-LSU phylogeny is one species not represented in our five-gene phylogeny, A. aurelia, which is supported as a distinct lineage (PP 1.00, ML-BP 99 %). Three undetermined sequences of Arachnopeziza are closely related or conspecific with A. araneosa, originating from apothecia on hardwood or softwood from Australia and New Zealand (A. sp. 7, 8, 9). Three environmental ITS sequences from clones originating from mesh bag in spruce forest and soil, i.e., A. sp. ‘a’ (3, 4, 5) (Fig. 4), were 100 % identical or nearly so to our two ITS sequences from A. sp. ‘a’ (1, 2) collections from Finland on Sphagnum, and are considered conspecific. Another four undetermined ITS sequences are likely closely related or conspecific with A. sp. ‘a’ based on ML analyses (ML-BP 75 %): three are environmental sequences from plant leaves (A. sp. 4, 5) and from soil (A. sp. 2), and one from apothecia on Phormium (A. sp. 3) (Fig. 4).

Relationships among phylogenetic species in Arachnopeziza

No supported conflict (PP ≥ 0.95, ML-BP ≥ 75 %) was detected between the single gene Arachnopezizaceae phylogenies in terms of relationships among the twelve species recognised. The five-gene phylogeny of Arachnopezizaceae is fully resolved and highly supported in all branches as inferred from Bayesian PP and/or ML-BP, except for the node joining A. aurata and the A. leonina clade, which has no support (Fig. 3). Eriopezia caesia is placed as the earliest diverging lineage in Arachnopezizaceae (as also found in the five-gene Helotiales phylogeny, Fig. 2). Four major clades are identified in Arachnopeziza and to facilitate results and discussion we have named these as indicated on Fig. 3. These clades receive high support from Bayesian PP (1.00) and ML-BP (100 %) except for the A. leonina clade that is supported only by Bayesian PP 0.99 (ML-BP 37 %).

The A. japonica clade consists of three closely related species with a lifestyle connected to bryophytes. Arachnopeziza estonica and A. japonica are morphologically very alike and they both form apothecia on stems and branches of Sphagnum. They are strongly supported as sister species in the five-gene phylogeny (Fig. 3); although Bayesian and ML analysis of RPB1 resolve A. ptilidiophila and A. japonica as sister species (PP 0.92, ML-BP 70 %), analysis of RPB2 and TEF-1α strongly supports A. japonica and A. estonica as sisters (PP 1.00, ML-BP 98 % and PP 0.53, ML-BP 87 %). Arachnopeziza ptilidiophila is associated with Ptilidium spp. and Pinus sylvestris, forming apothecia both on wood and Ptilidium shoots. Its connection to Ptilidium is unclear, not least because Ptilidium is omnipresent on Pinus sylvestris trunks. The A. japonica clade forms a highly supported monophyletic group with the A. delicatula clade as inferred from ML-BP 78 % (PP 0.86). The A. delicatula clade is composed of A. delicatula, A. araneosa and a newly discovered species A. sp. ‘a’ (to be described later when more material has been collected, including observations on vital morphological features). Arachnopeziza delicatula and A. sp. ‘a’ form a monophyletic group (PP 1.00, ML-BP 83 %). The A. leonina clade includes two highly supported subclades: A. leonina and A. obtusipila; and A. trabinelloides and a newly discovered species A. sp. ‘b’. Arachnopeziza sp. ‘b’ is morphologically difficult to distinguish from A. leonina, but appears to be restricted to Picea abies. The two records from Sweden and Finland show marked variation in all the studied gene regions and additional material is needed to explore this further. The A. leonina clade (and A. aurata) is placed as sister to the A. japonica and A. delicatula clades (PP 1.00, ML-BP 88 %). Arachnopeziza sphagniseda (previously Belonium sphagnisedum) constitutes a distinct separate clade, strongly supported as sister to the rest of Arachnopeziza in the five-gene phylogeny (PP = 1.00, ML-BP = 98 %, Fig. 3).

TAXONOMY

Based on GCPSR or genetic divergence using five loci (Fig. 3, Table 2), we delimited 12 species within Arachnopeziza, and with newly collected material from Northern Europe, nine of these are treated and discussed below. Based on the five-gene Bayesian phylogeny (Fig. 2) and morphological and histochemical characters, the two new genera within Hyaloscyphaceae, Mimicoscypha and Resinoscypha, are described with two and three species, respectively, that are combined in the genera. Updated descriptions or notes are given for all of these. Eupezizella is recognised as a separate genus for four species that are combined in the genus. Hyaloscypha usitata is reported for the first time from Europe. An account is given for Arachnoscypha that is removed from Arachnopezizaceae and placed in the Arachnoscypha-Polydesmia clade.

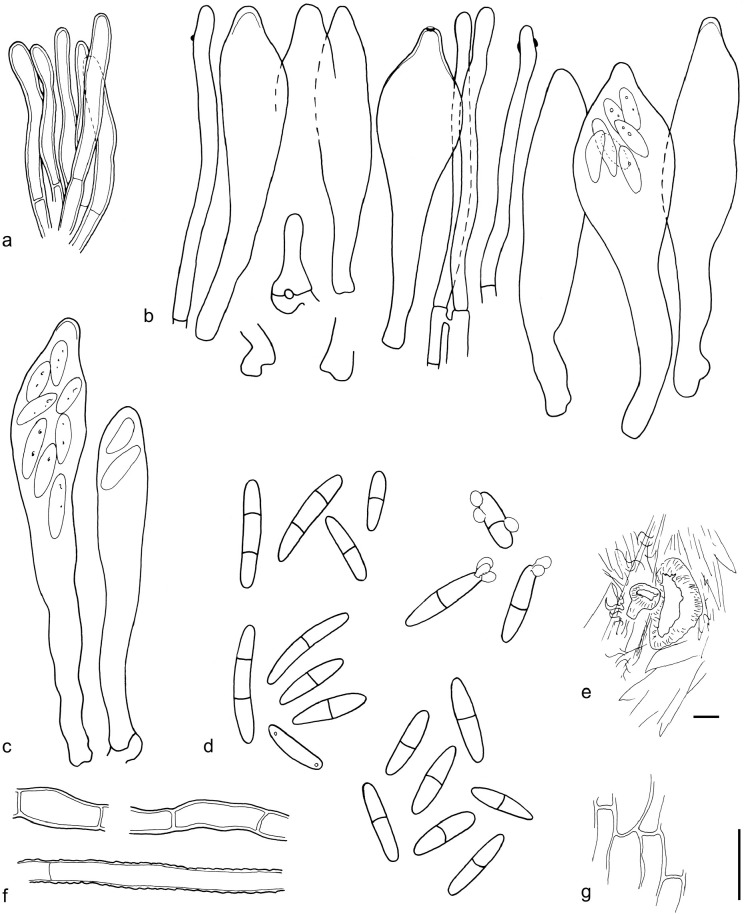

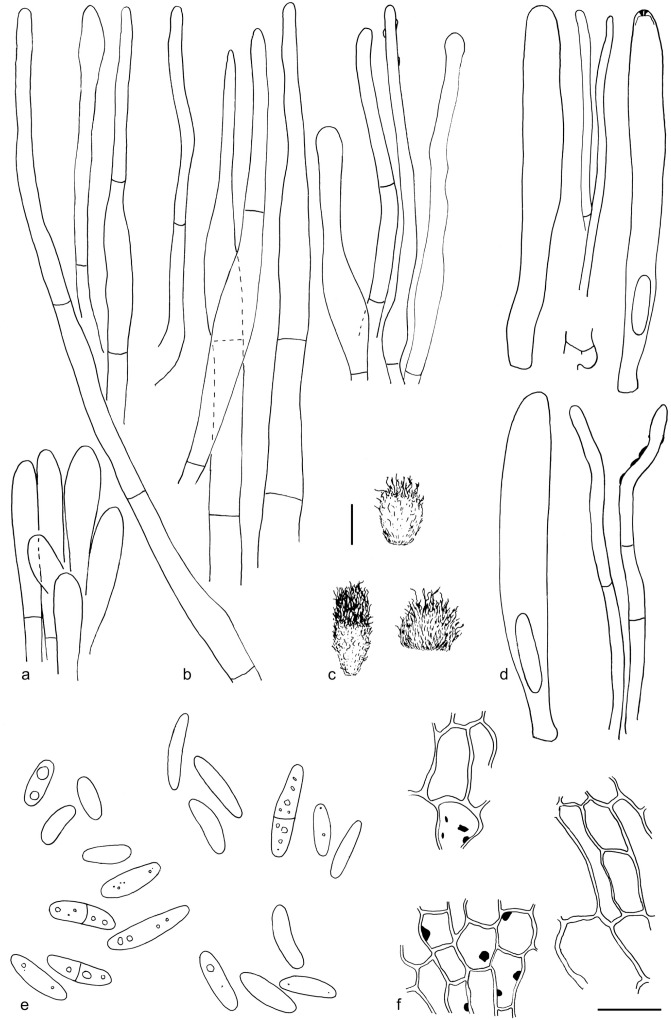

Arachnopeziza aurata Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 23–24: 304. 1870 — Fig. 5

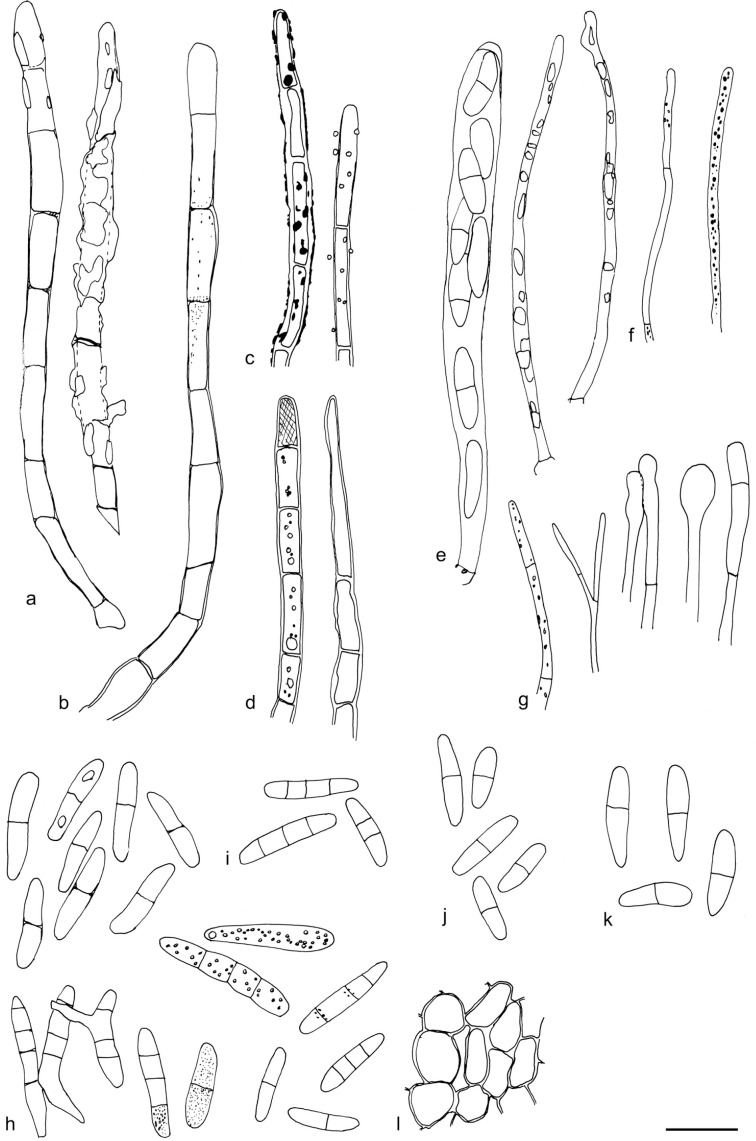

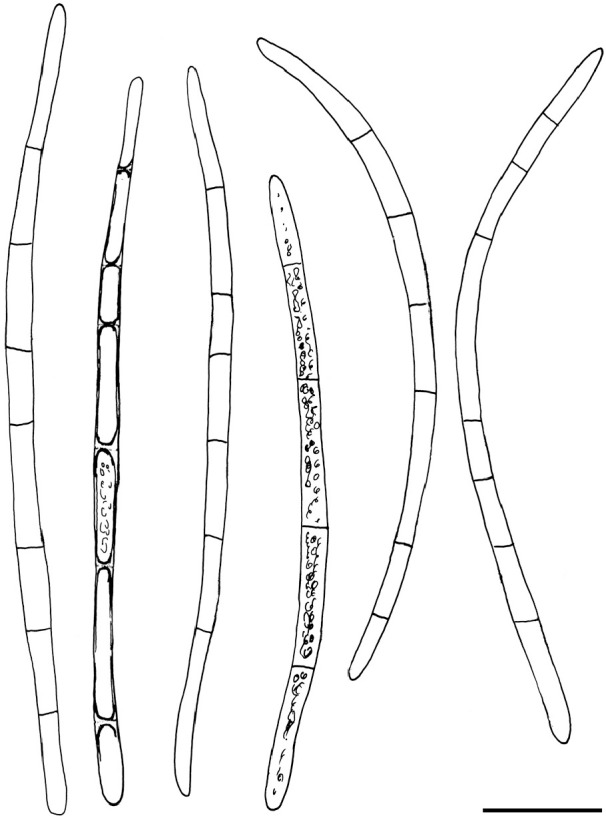

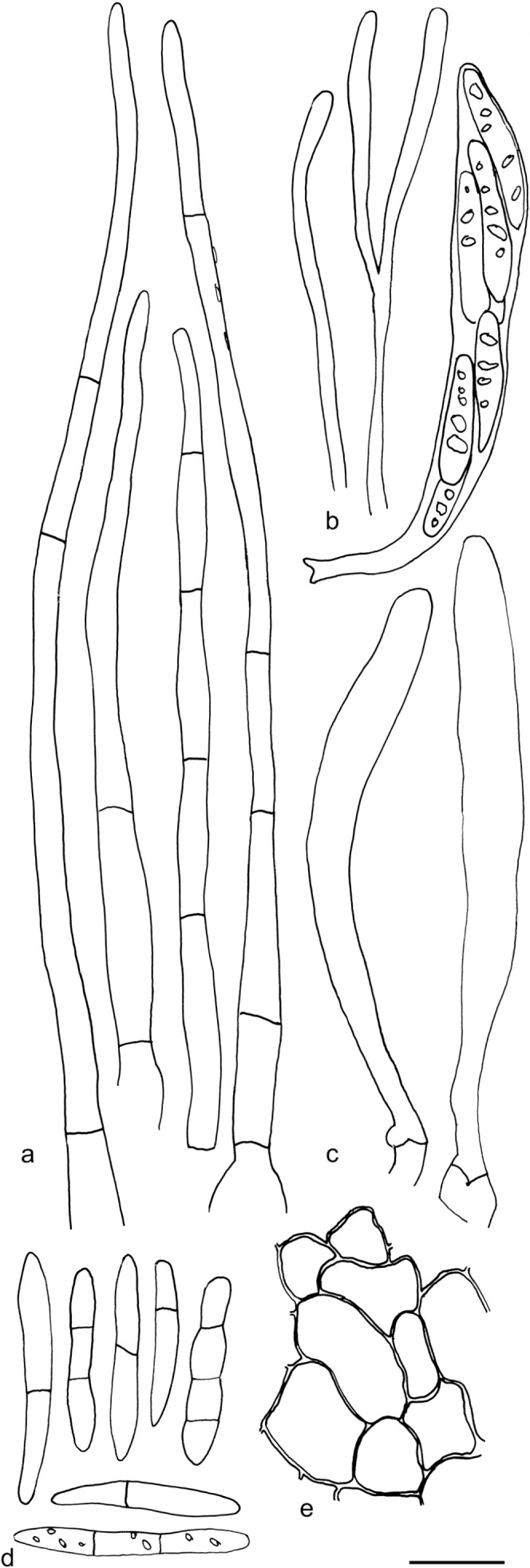

Fig. 5.

Arachnopeziza aurata. Spores in water (TUR 179456). — Scale bar = 10 μm. — Drawings: T. Kosonen.

Original material. GERMANY, Oestrich, on very moist inner bark of Populus pyramidalis, in the autumn, Fuckel (no date) (S-F92643, ex Herb. Fuckel 1894, ex Herb. Barbey-Boissier 1266) ! (duplicate S-F92641).

Specimen examined. DENMARK, Sjælland, Allindelille Fredskov, on hardwood, 26 May 2007, J. Fournier (TUR 179456).

Notes — We apply the name A. aurata to a collection from Denmark and, based on identical LSU sequences, to CBS 116.54 from France (Fig. 4). It is a distinct, well-delimited species based on our multi-gene phylogenetic analyses and morphology (Fig. 3, 5). In his monograph, Korf (1951b) distinguished A. aurata and A. delicatula primarily on spore measurements and septation: A. aurata with longer, (43–)48–73(–80) × 1.4–2.7(–3.4) μm, 7-septate spores; and A. delicatula with shorter, (24–)28–40(–48) × 2–2.7(–3.4) μm, 3–5 septate spores. Based on our molecular results using GCPSR, A. delicatula populations have often longer and up to 6–7-septate spores thus overlapping with A. aurata (see further under A. delicatula). We suggest that A. aurata is distinguished from A. delicatula by narrower, pointed and straight or curved spores, with regularly 6–7 septa. The spore measurements for the studied material are: 51.8–70.6(–78.3) × 1.7–2.7(–2.9) μm, mean 61.1 × 2.2 μm (n = 30), Q = 21.4–34.0, mean Q = 28.7. The apothecia of the Danish collection are intensively yellow orange. Resin is present on the hairs, among the excipulum cells as large droplets and on the subicular hyphae. No resin was observed on the paraphyses, but the exact placement of the pigment should be studied from fresh material.

Arachnopeziza aurata is resolved as a sister species to the A. leonina clade (Fig. 3), characterized by ample resin depositions on the hairs and in the excipulum. Arachnopeziza delicatula, although with overlapping spore morphology, belongs to a separate clade. Since the large material studied and referred to A. aurata by Korf (1951b) may include collections representing A. delicatula, the reported variation in morphology is possibly variation between A. delicatula and A. aurata populations. The distribution and ecological range of A. aurata is thus also unclear, and will need further study. It is interesting that the collections of A. aurata sensu Korf were not only from various decaying hardwood trees, but also from herbaceous plants, i.e., Typha and Andromeda (Korf 1951b), a substrate not commonly reported for Arachnopeziza species. We made no observations of A. aurata from Estonia, Finland and Sweden during forays in a wide range of habitats, whereas A. delicatula was observed continuously.

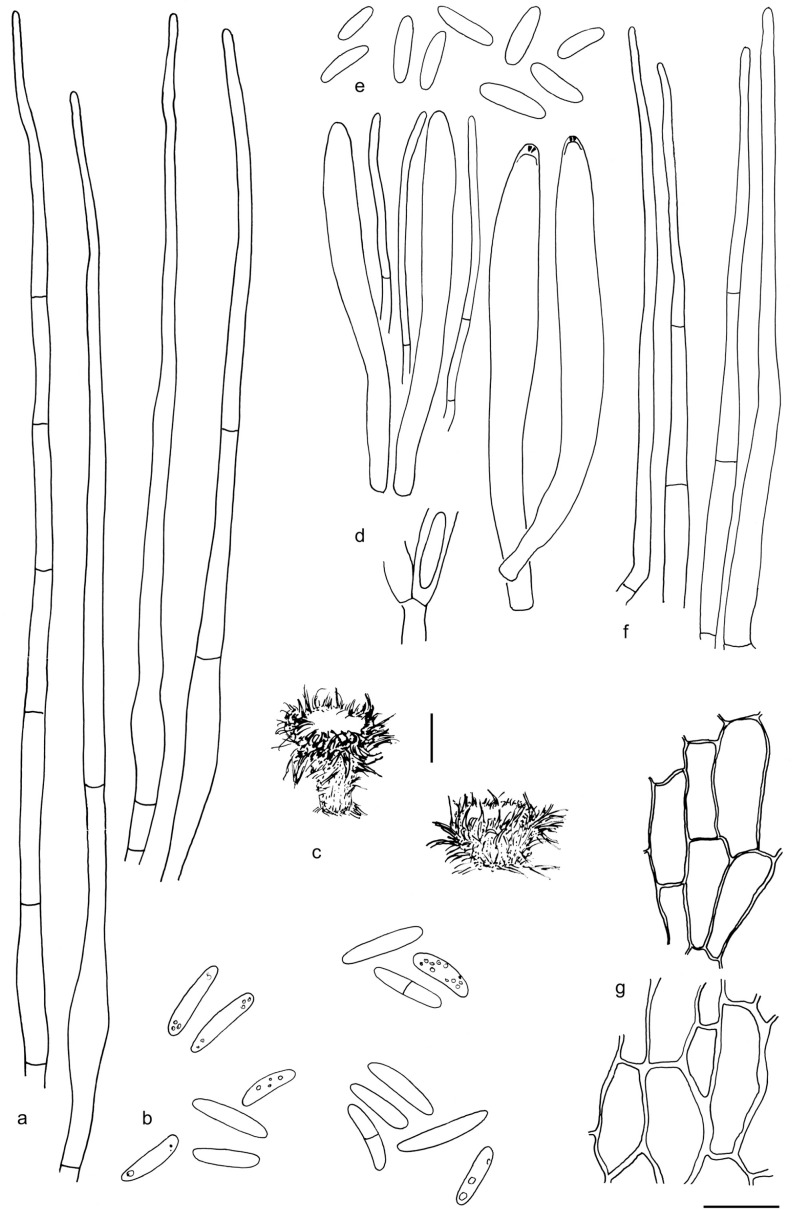

Arachnopeziza delicatula Fuckel, Jahrb. Nassauischen Vereins Naturk. 23–24: 304. 1870 — Fig. 6

Fig. 6.

Arachnopeziza delicatula. Spores in CR (a: TNS-F12770; b: T. Kosonen 7036; c: T. Kosonen 7076; d: T. Kosonen 7127). — Scale bar = 10 μm. — Drawings: T. Kosonen.

Original material. GERMANY, Eberbach, Eichberg forest, on Quercus sp., Fuckel, no date (S-F153832, Fuckel Fungi Rhen. Exs. 2384) !

Specimens examined. CANADA, Yukon, Kluane Lake, NW of Sulphur Lake, on Populus tremuloides, 22 Sept. 1987, S. Huhtinen 87/145 (TUR). – FINLAND, Varsinais-Suomi, Turku, Piipanoja, 14 May 2015, T. Kosonen 7036 (S, TUR); Etelä-Häme, Urjala, Raikonkulma, Rantakaski, on a fallen trunk of Betula, 25 Sept. 2015, T. Kosonen 7115 (S, TUR); same date and location, T. Kosonen 7116 (S, TUR); Pohjois-Savo, Suonenjoki, Viippero, Ilmakkamäki, on a trunk of P. tremula, 23 Sept. 2013, J. Purhonen 6655 (JYV 11610); Muurame, Kuusimäki, 25 Aug. 2015, T. Kosonen 7076 (S, TUR). – JAPAN, Hokkaido, Iwamizawa-shi, Tonebetsu, 25 July 2004, T. Hosoya (TNS-F12770). – SWEDEN, Dalsland, Håverud, Forsbo Nature Reserve, on a trunk of Betula, 23 Sept. 2016, S. Huhtinen 16/54 (S, TUR); Västergötland, Falköping, Forentorpa ängars Nature Reserve, on a trunk of Betula, 15 Oct. 2015, T. Kosonen 7127 (S, TUR); Kinnekulle, Munkängerna, on Ulmus, 17 Oct. 2015, K. Hansen & T. Kosonen 7132 (S, TUR); Öland, Byxelkrok, Trollskogen, on a trunk of Betula, 29 Mar. 2016, T. Kosonen 7152 (S, TUR). – USA, Massachusetts, Bristol County, North Easton, Borderland State Park, on the underside of a decayed hardwood log, 19 May 2012, J. Karakehian 12051901 (S, TUR).

Notes — Arachnopeziza delicatula appears to be a phylogenetically and morphologically diverse species. Both Fuckel (1870) in the original description and Korf (1951b) in his monograph describe A. delicatula spores being on average less than 50 μm long and with up to 5 septa. Such populations exist in the material reported here, but using GCPSR they do not represent a distinct species from those populations with on average longer spores (above 50 μm). Instead, our results suggest that A. delicatula have spores with a wide range in length: 30–61.0(–63.5) × 2.4–3.8(–4.0) μm in CR, mean 47.6 × 2.9 μm, Q = 9.7–23.8(–25.7), mean Q = 16.5 (n = 35, from three populations). It can be distinguished from A. aurata by the width of the spores that are on average wider in A. delicatula (3–3.5 μm wide in the longest spores) and by the Q-value that is in average less than 20 in A. delicatula and above 20 in A. aurata. Most likely this is the main reason for the numerous ITS and LSU sequences deposited in GenBank under the name A. aurata, which we consider to represent A. delicatula (see Fig. 4). Despite the wide range in spore size and high divergence in ITS sequences we found no support for delimiting further species based on GCPSR or on geographical origin (Fig. 3, Table 2). All the samples studied by us were from hardwood and most of the ITS and LSU sequences retrieved from GenBank originated from apothecia on wood (if specified, on hardwood). One GenBank ITS sequence is from a plant root (CL0301_4_1 from South Africa) (Fig. 4). It is identical to an ITS sequence of a North American collection (J. Karakehian 12051901), which is also represented in our multi-gene analyses (A. delicatula 3, Fig. 3). There are earlier reports of A. delicatula from softwood (e.g., Korf 1951b), as well as some more recent collections in TAAM. Our preliminary morphological study of the TAAM A. delicatula collection (TAAM062455) from softwood, found it conforms to the other A. delicatula material examined here. This could well be a demonstration of a broad ecology, but there are no sequences available from material on softwood.

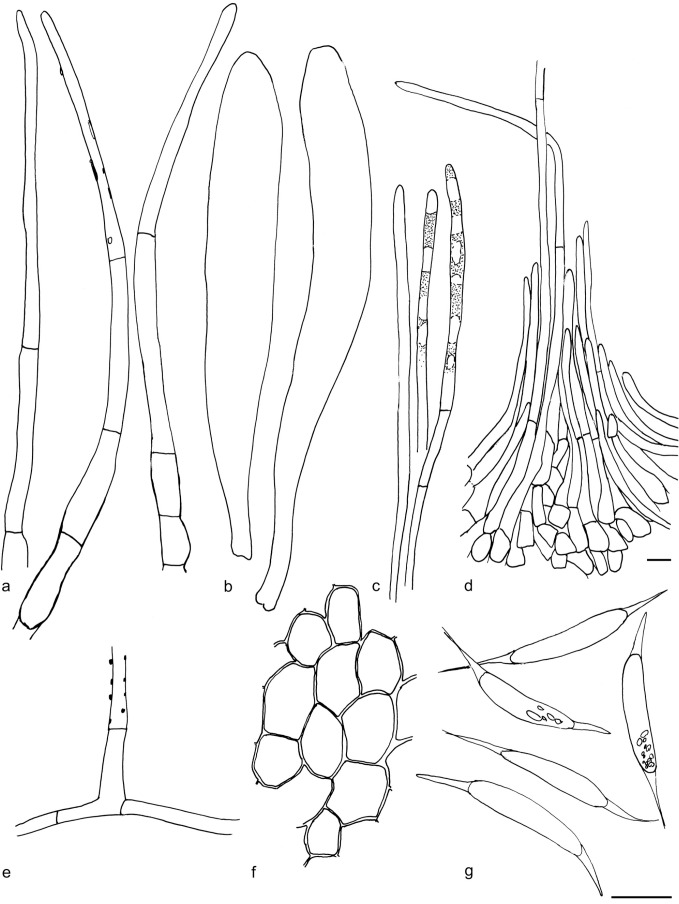

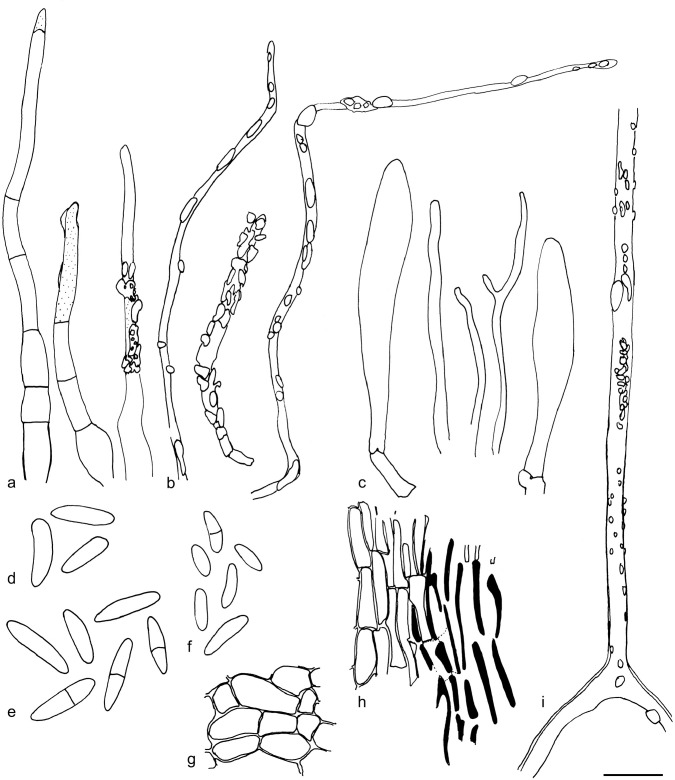

Arachnopeziza estonica T. Kosonen, Huhtinen, K. Hansen, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB835728, Fig. 7

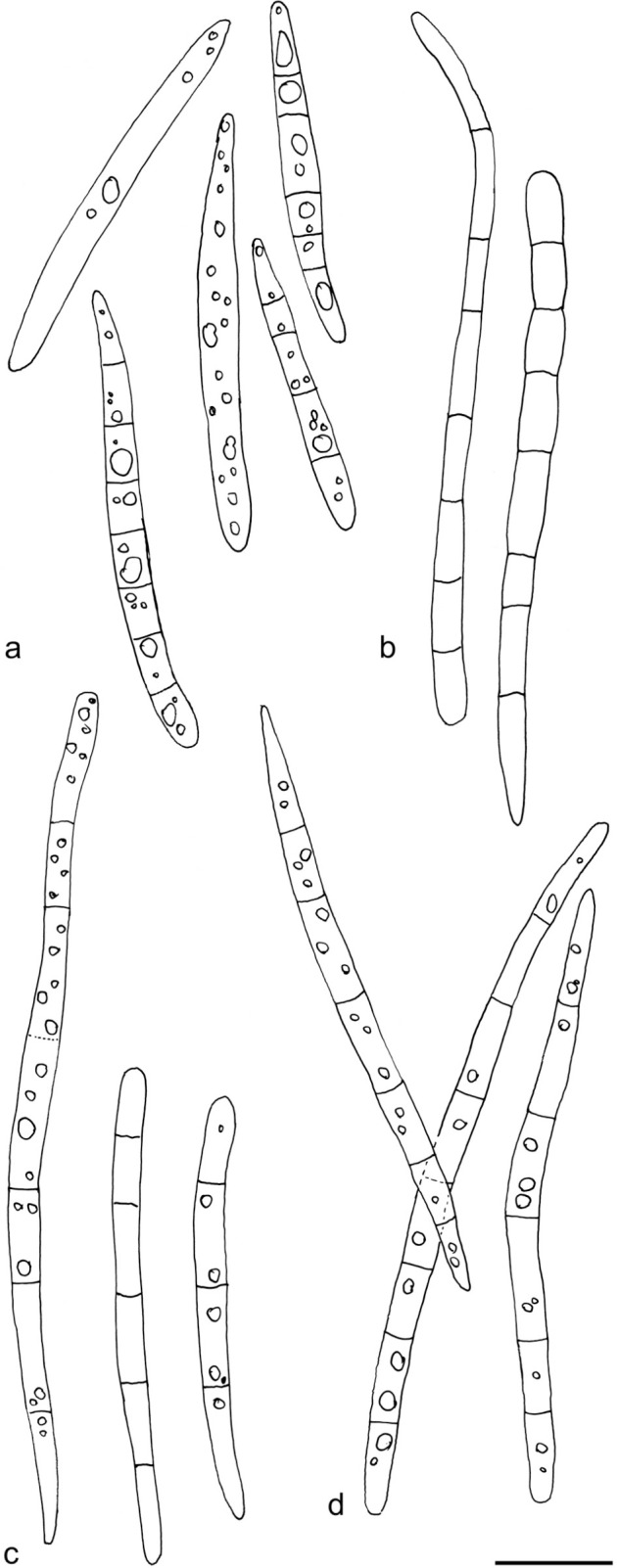

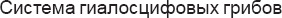

Fig. 7.

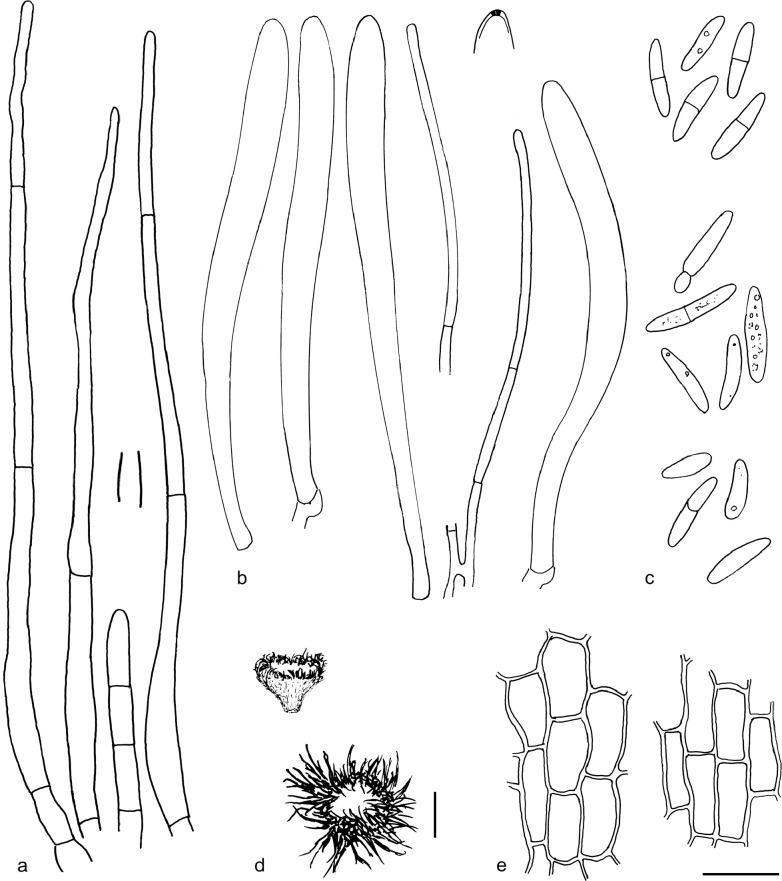

a, c, e–f. Arachnopeziza estonica (holotype) and b, d, g–i. A. japonica. All in CR. a–b. Hairs; c–d. asci and paraphyses; e–f. spores; g–h. excipulum; i. hairs, asci and spores (a, c, e–f: S. Huhtinen 15/38; b, d, g–h: T. Laukka 267; i: holotype). — Scale bar = 10 μm. — Drawings: T. Kosonen.

Etymology. Referring to the geographical origin of the holotype.

Holotype. ESTONIA, Otepää, Kääriku, NE of lake Kääriku, on Sphagnum squarrosum, in a boggy mixed forest, 13 Sept. 2015, S. Huhtinen 15/38 (S-F399746); Isotype (TUR 212780) !

Apothecia 0.2–0.5 mm diam, hyaline to white when fresh, white with a yellow hue when dry, on leaves of Sphagnum, narrowly attached, often only with a few visible long hairs originating from the margin and upper flanks, subiculum present but indistinct to naked eye. Ectal excipulum in the upper flanks of textura prismatica, cells c. 15–20 × 5 μm, below and towards the base of textura angularis to globulosa, cells c. 5–10 μm diam. Hairs 50–90 × 3–4 μm, with 3–5 septa, cylindrical, thin-walled, but moderately to clearly thick-walled in the basal parts, uppermost cell tapering distinctly, smooth, hyaline resin present on the outside. Asci 70–90 × 6–10(–14) μm, cylindrical to clavate, apical pore MLZ+, arising from croziers. Ascopores 15.6–23.2(–24.2) × 2.8–4.4(–5.2) μm, mean 18.8–3.7 μm, Q = 3.9–8.3, mean Q = 5.2 (n = 55, from two populations), cylindrical, often narrowing more prominently towards basal end, with characteristic angular appearance, usually with 0–1 septa, or more rarely with two. Paraphyses cylindrical, regularly branched at the basal cell, smooth and without content in CR. Subicular hyphae 3–5 μm wide, thick-walled, finely warted.

Specimens examined. FINLAND, Varsinais-Suomi, Turku, Kuhankuono, on Sphagnum, 13 Nov. 2005, T. Laukka 253 (TUR); Etelä-Häme, Tammela, Liesjärvi, on Sphagnum, 4 July 2005, T. Laukka 210 (TUR); Pohjois-Häme, Ruovesi, Siikaneva National Park, on Sphagnum squarrosum, 7 Sept. 2005, T. Laukka 245 (TUR).

Notes — This species is very closely related to A. japonica and morphologically very similar. It is supported as a separate species using GCPSR (Fig. 3, Table 2) and it can be distinguished by the on average larger spores and wider hairs as compared to A. japonica. The hair apices are slightly inflated in A. japonica, whereas in A. estonica the hairs taper evenly and no apical widening is observed. All observations are from Sphagnum and often from Sphagnum squarrosum. The two close species, A. japonica and A. estonica, appear to have very similar ecology at least in Scandinavia.

Arachnopeziza japonica Korf, Bull. Natl. Sci. Mus., Tokyo 44: 392. 1959 — Fig. 7

Holotype. JAPAN, Kyushu, Miyazaki prefecture, Yabitsu valley, Kijomura village, on leaves, leaf-galls and debris, 6 Nov. 1957, S. Imai et al. (CUP-JA-422) !

Apothecia 0.2–0.6 mm diam, hyaline to whitish when fresh, white with a yellow hue when dry, at margin distinctly hairy, broadly attached, subiculum present, scanty. Ectal excipulum of firm walled textura prismatica, cells c. 18 × 5 μm in the upper flanks, somewhat thick-walled textura angularis – textura globulosa towards the base, cells 3.5–10 μm wide. Hairs 50–80 × 2–3 μm, cylindrical, with 3–5 septa, thin-walled, in the basal parts with moderately to clearly thickened walls, apices typically widened, smooth, hyaline resin present, only partly soluble in MLZ or lactic acid, hairs often tightly glued together in dry material. Asci 70–90 × 6–10(–14) μm, cylindrical to clavate, apical pore clearly MLZ+, arising from croziers. Ascospores 12.5–21.6(–23.2) × 2.7–4.1(–4.4) μm, mean 16.3 × 3.3 μm (n = 60, from two populations), Q = 3.9–7.9, mean Q = 5.1, cylindrical, but usually narrowing more prominently towards the basal end, slightly angular, usually with 1–2 septa, the 2-septate spores are relatively common, rarely with 3 septa. Paraphyses regularly branched at the basal cell, smooth and without content in CR, with a round apex. Subicular hyphae 3–5 μm wide, thick-walled, warted.

Specimens examined. All specimens on Sphagnum. FINLAND, Varsinais-Suomi, Nousiainen, Pukkipalo, 26 May 2006, R. Ilmanen 194 (TUR); Parainen, Kirjalansaari, 22 Sept. 2006, R. Ilmanen 239 (TUR); same location, 22 Sept. 2006, T. Laukka 267 (TUR). – SWEDEN, Söderåsen Nature Park, 5 June 2006, S. Huhtinen 06/3 (TUR).

Notes — Arachnopeziza japonica is recorded for the first time from Europe. The four collections from Finland and Sweden agree well with the original description and our study of the holotype. In spore size, the holotype (CUP-JA-422, spores: 11.5–16.0 × 2.7–3.0, n = 4) represents the smaller-spored part of the variability, but the observed range is relatively wide and the number of measured spores from the scanty specimen is very small. New observations include a population (R. Ilmanen 194) with a roughly similar average spore size and variation as the holotype. Spores with 3 septa are rare and usually then clearly overmature. Spores with 2 septa are relatively common and have the same size and shape as spores with one or no septa. The original description was based on only the holotype from forest litter without any mention of bryophytes or mires. The four recent collections are from Sphagnum from paludified forest habitats. Arachnopeziza japonica belongs to a clade of three closely related species sharing a connection to bryophytes. Often apothecia of these Arachnopeziza species were found by studying randomly picked Sphagnum tuffs under a dissecting microscope. Based on the frequently found (single) apothecia on Sphagnum, we conclude that the species are relatively common (on Sphagnum), but the limits of their ecological niche are poorly known. Larger groups of apothecia of these species were found less often.

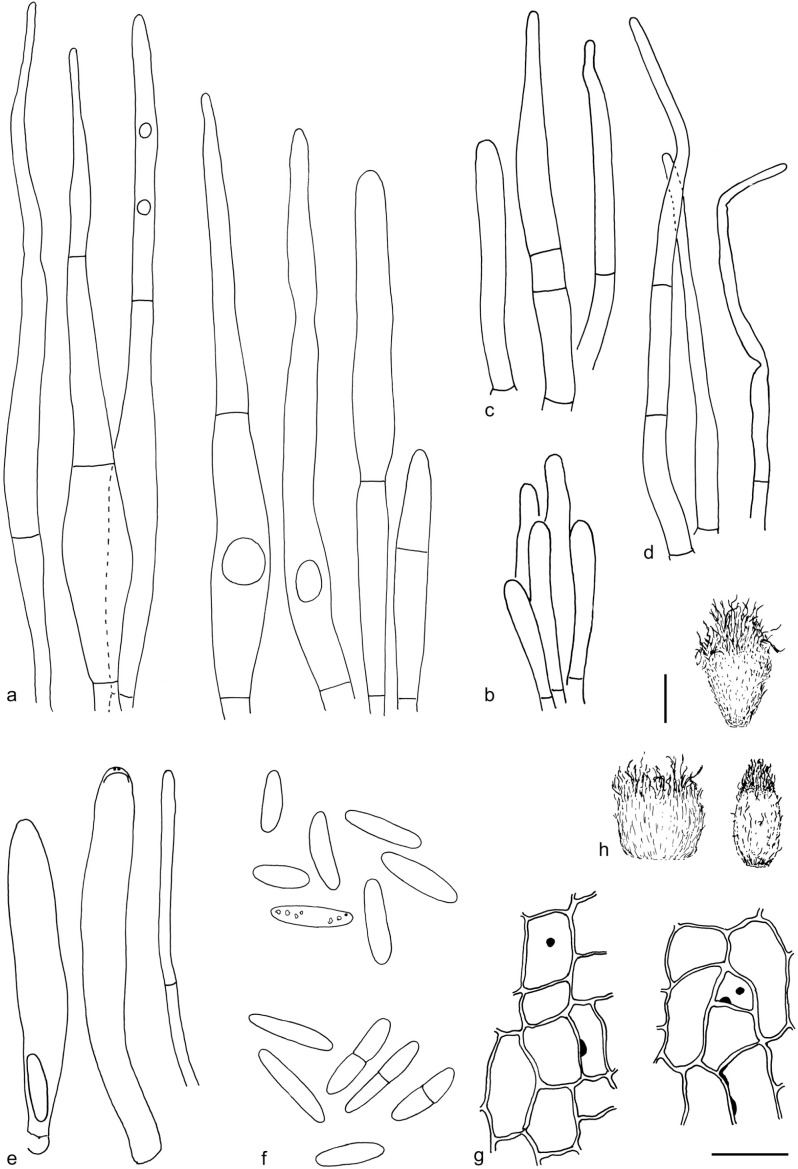

Arachnopeziza leonina (Schwein.) Dennis, Kew Bull. 17: 351. 1963 — Fig. 1a–c, 8

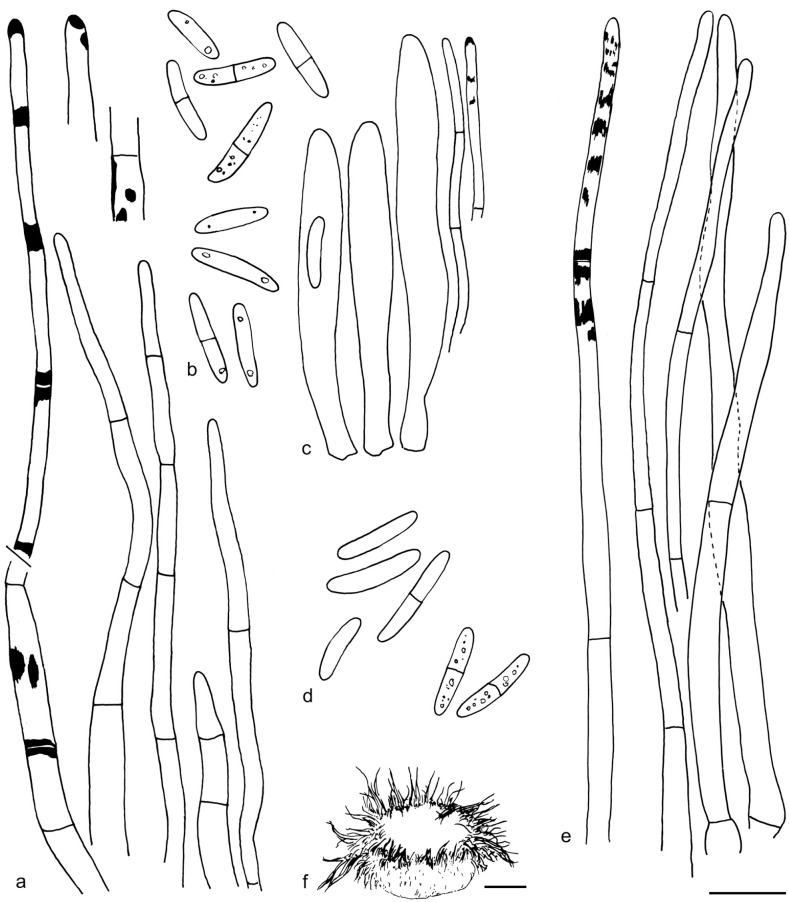

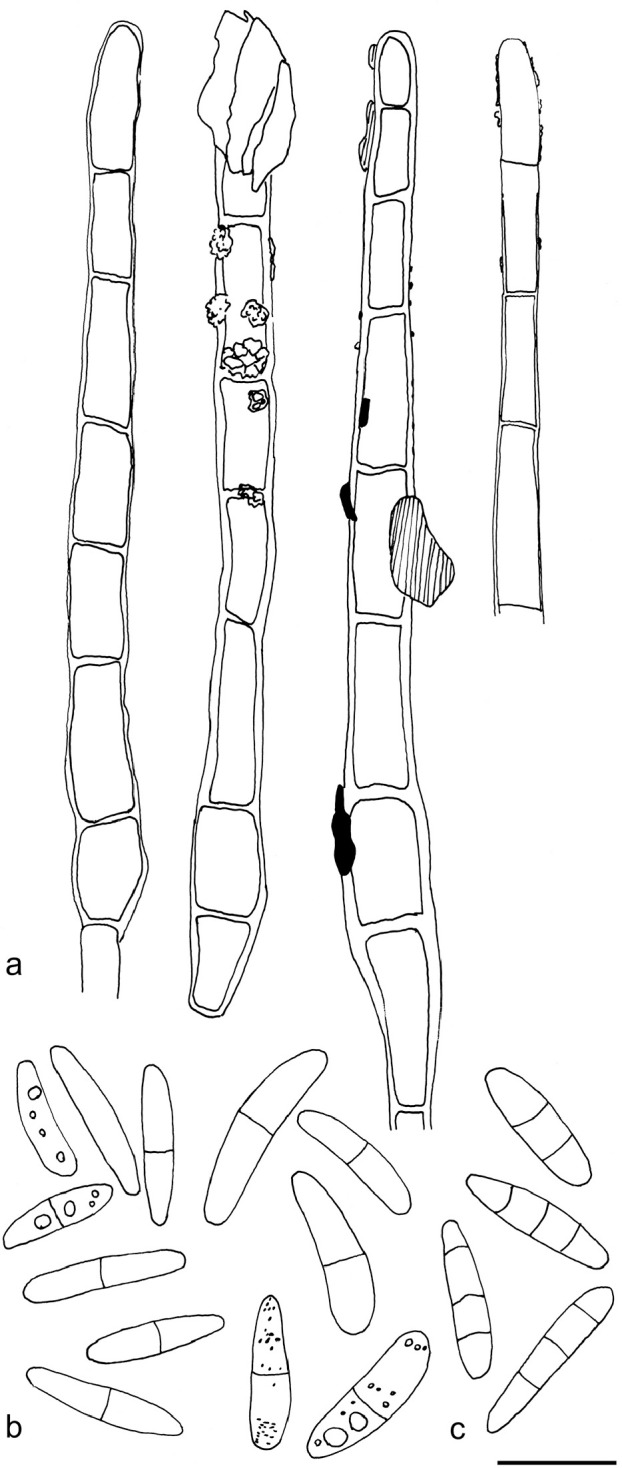

Fig. 8.

Arachnopeziza leonina. a. Hairs in water; b. spores in water; c. four spores with multiple septa in CR (a–b: GJO 0071770; c: KH.15.23). — Scale bar = 10 μm. — Drawings: T. Kosonen.

Basionym. Peziza leonina Schwein., Schr. Naturf. Ges. Leipzig 1: 93. 1822.

Synonym. Arachnopeziza candido-fulva (Schwein.) Korf, Lloydia 14: 163. 1951.

Specimens examined. AUSTRIA, Steiermark, Graz, Andritz, near the church of St. Ulrich, on hardwood, 1 Mar. 2014, I. Wendelin (GJO 0071770). – ESTONIA, Valga, Sangaste, Lauküla, Keesliku forest, on a trunk of Populus tremula, 12 Sept. 2015, T. Kosonen 7101 (S, TUR); same date and location, K. Hansen, KH.15.23 (S, TUR). – FINLAND, Pohjois-Häme, Muurame, Kuusimäki, on a trunk of Betula sp., 25 Aug. 2015, T. Kosonen 7078 (S, TUR); same date and location, on a trunk of P. tremula, T. Kosonen 7091 (S, TUR); on a trunk of Betula sp., T. Kosonen 7092 (S, TUR); on trunk of Betula sp., 14 May 2018, J. Purhonen & T. Kosonen 7294 (S, TUR). – SLOVAKIA, Chorvátsky Grob, Čierna voda, National Nature Reserve Šúr, on a decayed hardwood trunk, 22 Nov. 2017, A. Polhorský 18/26 (S, TUR). – SWEDEN, Stockholm, Haninge, Tyresta National Park, on a trunk of P. tremula, 1 June 2016, T. Kosonen & S. Huhtinen 16/42 (S, TUR); Västra Götaland, Falköping, Forentorpa ängars Nature Reserve, 15 Oct. 2015, T. Kosonen 7128 (S, TUR).