CONFLICT OF INTEREST

CA has received research grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation, European Union (EU CURE), Novartis Research Institutes (Basel, Switzerland), Stanford University (Redwood City, Calif) and SciBase (Stockholm, Sweden); he is the Co‐Chair for EAACI Guidelines on Environmental Science in Allergic diseases and Asthma and serves on the Advisory Boards of Sanofi/Regeneron, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline and SciBase, and is the Editor‐in‐Chief of Allergy. All other authors have no conflicts to disclose.

To the Editor,

There is a substantial need to better understand the pathophysiology of asthma to develop preventive approaches and better treatments. Preclinical models as close as possible to human in vivo situations are essential to fulfil these aims. 3D airway culture models, particularly airway organoids, have several advantages over traditional 2D cultures, such as mimicking organ structure, ability to generate in vivo relevant cell–cell interaction models, suitability for high‐throughput experiments, and applications in epithelial self‐assembly, morphogenesis, differentiation and repair studies. 1 , 2 A dominant endotype of asthma is characterized with an impaired airway epithelial barrier, remodelling and the involvement of type 2 inflammation with cytokines such as interleukin (IL)‐4, IL‐5 and IL‐13. 3 , 4 In the present study, we aimed at establishing a 3D airway organoid model from primary bronchial epithelial basal cells to investigate the characteristic features of asthma, such as epithelial cell differentiation, epithelial remodelling and mucosal tight junction barrier impairment in the presence of a main pathogenetic type 2 cytokine, IL‐13.

A 3D airway organoid model was developed as previously described 2 from commercially obtained healthy primary bronchial epithelial basal cells (Figure S1). Since this organoid model does not have self‐renewal capacity and consists solely of epithelial cells, it is hereinafter referred to as the ‘bronchial epithelial spheroid model’. In order to study the main features of asthma, cells were continuously stimulated with 2 ng/ml IL‐13 every second day starting from Day 2 until the end of the cultures. For the control group, only fresh medium was added to the wells. Cultures were terminated on Days 8 and 16, then, light microscopy examination, mRNA isolation, paracellular flux (Day 16) and immunofluorescent staining were performed (Figure S2). Detailed methods are provided in online supplementary (Table S1‐S3).

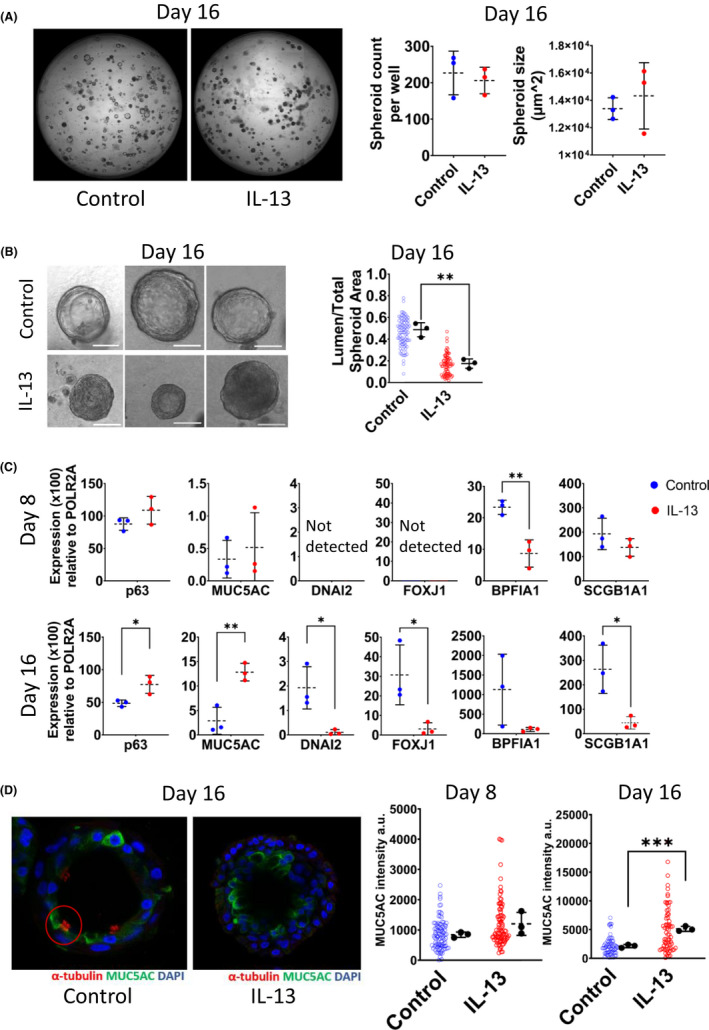

Treatment of developing spheroids with IL‐13 did not affect the spheroid count per well and spheroid size (Figure 1A). However, it caused the development of thick‐walled spheroids with small or no lumen resulting in a decreased ratio of ‘lumen‐to‐total spheroid area’ (Figure 1B). The differentiation process was greatly affected by the presence of IL‐13, resulting in increased differentiation towards mucus‐producing goblet cells with a dramatic decrease in mRNA levels of both ciliated cell markers, dynein axonemal intermediate chain 2 (DNAI2) and forkhead box protein J1 (FOXJ1). FOXJ1, a master regulator of ciliogenesis, has crucial physiological roles in ciliated cell development. 2 , 4 Therefore, decreased mRNA levels of these marker genes indicate the suppression of ciliated cell differentiation. In addition, it is noteworthy that the mRNA levels of the club cell marker, secretoglobin family 1A member 1 (SCGB1A1) decreased in fully mature spheroids (Figure 1C) under IL‐13 treatment. SCGB1A1 has been proposed as a predictive marker for the risk of impaired lung function, such as lung epithelial damage in asthma. It is involved in tissue repair processes and has anti‐inflammatory effects. 5 These findings are consistent with the low protein levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids of asthmatic individuals. 5 Furthermore, the decrease in the number of the club and ciliated cells by IL‐13 suggests a differentiation or metaplasia towards goblet cells in bronchial epithelial spheroids. Moreover, IL‐13 decreased the mRNA levels of bactericidal/permeability‐increasing protein fold‐containing family member A1 (BPIFA1). BPIFA1 has crucial roles in reducing eosinophilic airway inflammation, relaxing airway smooth muscle and antibacterial activity against Gram‐negative bacteria. 6 Meta‐analysis of BPIFA1 expression in epithelia obtained by bronchial brushings from asthmatic individuals shows decreased mRNA levels similar to our findings. 6 Confocal microscopy imaging showed a significant increase in MUC5AC intensity without detectable ciliated cells, which were identified by acetylated α‐tubulin staining in organoids treated with IL‐13 (Figure 1D). These findings are parallel to the epithelial differentiation features of type 2 asthmatic individuals, findings in mouse models and airway epithelial cell cultures. 2 , 4

FIGURE 1.

Treatment of bronchial epithelial spheroids with IL‐13 recapitulates characteristic asthmatic epithelial cell differentiation phenotype. A, Representative light microscopy images from control and IL‐13‐treated bronchial epithelial spheroids on Day 16. The average number of spheroids and average spheroid size per well (µm2) (right panel). B, Representative light microscopy images on Day 16. Scale bar 50 µm. ‘Lumen‐to‐total spheroid area’ is shown on the right side. C, Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of goblet cell (MUC5AC), ciliated cell (FOXJ1 and DNAI2), basal cell, (p63) club cell (SCGB1A1) markers and antimicrobial protein BPIFA1. Expression values calculated with 2 (−ΔCt) formula and represented as expression (x100) relative to housekeeping gene, POLR2A. D, Immunostaining of spheroids for DNA (blue), and markers of ciliated cells (acetylated α‐tubulin, red) and goblet cells (MUC5AC, green). Graphical representations of MUC5AC intensity at Days 8 and 16 of treatment are shown at right. Individual spheroids were represented as hollow dots and biological replicates (n:3) as black dots. Data are presented as means +/‐ SDs. For statistical analysis, two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test was used. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

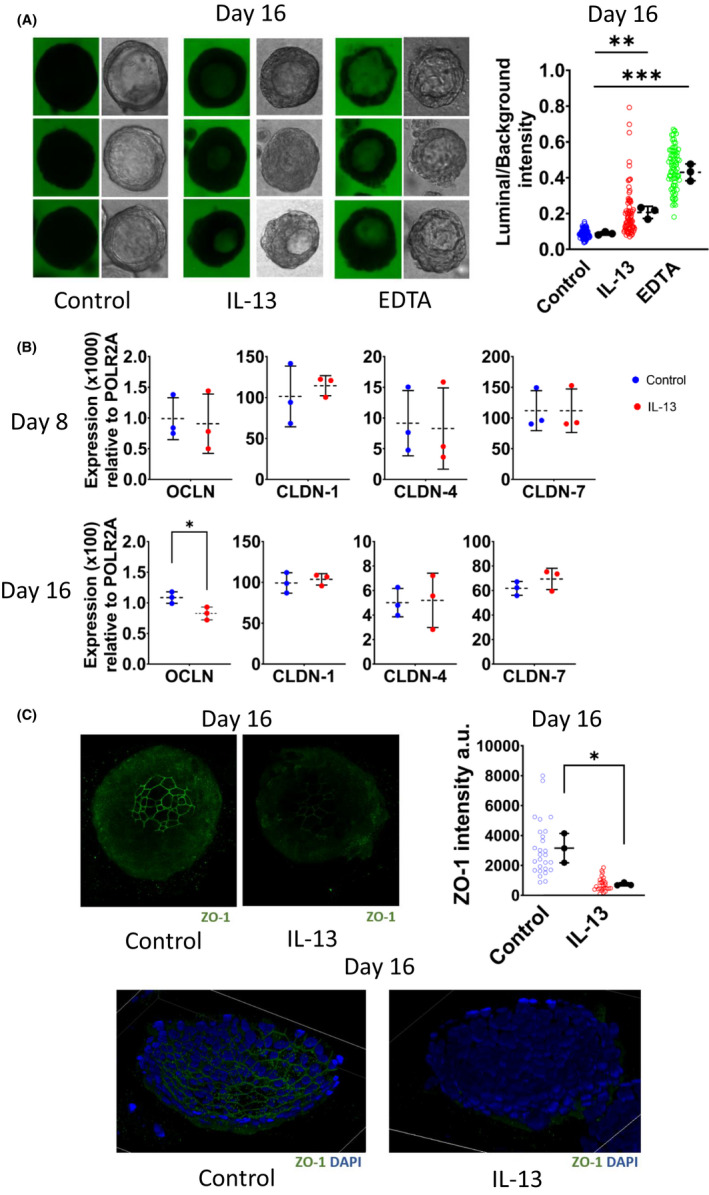

Given the fact that the impaired epithelial barrier is one of the hallmarks of asthma, 3 we assessed the epithelial barrier development in spheroids. On Day 16 of the culture, fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)‐labelled 4‐kDa dextran was added to the cultures and the paracellular flux of it into the lumen of the spheroids was assessed with confocal microscopy at the end of the 24‐hour incubation. EDTA was used as a positive control for epithelial barrier impairment (Figure S3). Only luminated spheroids were included in the measurements. IL‐13 treatment resulted in an impaired epithelial barrier development evidenced with a high ‘lumen‐to‐background intensity ratio’ (Figure 2A) and decreased occludin mRNA and ZO‐1 staining intensity on Day 16 (Figures 2B,C). These results demonstrated that bronchial epithelial spheroid development under the influence of a type 2 cytokine, IL‐13, is leading to an epithelial barrier disorder similar to asthma. 3

FIGURE 2.

Treatment of bronchial epithelial spheroids with IL‐13 impaired epithelial barrier development. A, Representative light and fluorescence microscopy images of the paracellular flux assay performed on Day 16 of culture. Each row of the spheroid pictures represents a biological replicate. EDTA used as a positive control for epithelial barrier impairment. Individual spheroids are represented as hollow dots and biological replicates (n:3) presented as black dots (right panel). B, Quantitative RT‐PCR analysis of tight junction proteins, occludin (OCLN), claudin‐1 (CLDN‐1), claudin‐4 (CLDN‐4) and claudin‐7 (CLDN‐7). Expression values calculated with 2 (−ΔCt) formula and represented as expression (×100) relative to POLR2A. C, Immunostaining of spheroids for DNA (blue) and ZO‐1 (green). Graphical representations of ZO‐1 intensity on Days 8 and 16 of culture are shown at right. Individual spheroids were represented as hollow dots and biological replicates (n:3) as black dots. Data are presented as means ±SDs. For statistical analysis, two‐tailed unpaired Student's t‐test was used. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001

In conclusion, we successfully developed an in vitro asthma model with a 3D airway organoid model termed here bronchial epithelial spheroids that recapitulates characteristic features of asthmatic airway epithelia. It demonstrates decreased ciliated and club cells and skew to a high mucus‐producing and goblet cell‐dominant phenotype with disrupted epithelial barrier by IL‐13. These results demonstrate that IL‐13 impairs the epithelial barrier by affecting both epithelial differentiation and tight junction protein expression. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first in vitro asthma model that investigates epithelial barrier development and differentiation process in a 3D culture of primary bronchial epithelial cells with a detailed analysis including functional permeability, gene expression and immunofluorescence studies. The model is adaptable for high‐throughput experiments, airway epithelial morphogenesis and development studies.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

Movie S1

Movie S2

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Open access funding provided by Universitat Zurich.

Funding information

None.

REFERENCES

- 1. Tan Q, Choi KM, Sicard D, Tschumperlin DJ. Human airway organoid engineering as a step toward lung regeneration and disease modeling. Biomaterials. 2017;113:118‐132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Danahay H, Pessotti AD, Coote J, et al. Notch2 is required for inflammatory cytokine‐driven goblet cell metaplasia in the lung. Cell Rep. 2015;10(2):239‐252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Akdis CA. Does the epithelial barrier hypothesis explain the increase in allergy, autoimmunity and other chronic conditions? Nat Rev Immunol. 2021;1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jackson ND, Everman JL, Chioccioli M, et al. Single‐cell and population transcriptomics reveal pan‐epithelial remodeling in type 2‐high asthma. Cell Rep. 2020;32(1):107872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mootz M, Jakwerth CA, Schmidt‐Weber CB, Zissler UM. Secretoglobins in the big picture of immunoregulation in airway diseases. Allergy. 2022;77(3):767‐777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kellogg C, Huang J, Frisbee J, et al. BPIFA1 expression in asthmatics. Eur Respir J. 2020;56(suppl 64):615. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Movie S1

Movie S2