Abstract

Among individuals of African and Latinx descent compared to those of European background, there is a higher prevalence, earlier onset, more rapid progression of primary open angle glaucoma and greater incidence of blindness. Although some suggest that outreach, education and screening programs may expand earlier diagnosis, and attention to access, cost of treatment, and adherence will improve outcomes, there is increasing evidence of genetic and physiologic differences which may be associated with these disease disparities.

Introduction

Disparities in health care have been repeatedly documented over the last few decades across a broad range of medical conditions. Members of minority groups are more likely to receive lower-quality care than their White counterparts, even following adjustment for income levels, insurance status, and education, as noted in a report from the National Institute of Medicine.1 An important example of the impact of racial and ethnic disparities on chronic disease includes glaucoma, a leading cause of irreversible blindness worldwide (Figure 1). Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy with a common endpoint of retinal ganglion cell death. Lowering of intraocular pressure (IOP), the only known modifiable risk factor, has been shown to reduce risk of developing glaucoma and progression to vision loss and blindness at all levels of disease severity. Thus, adherence to provider appointments and therapies, both medical and surgical, leads to improved outcomes. However, Latinx and Black patient status represents an independent risk factor for inconsistent follow-up in a glaucoma clinic2 and lower rates of ancillary glaucoma testing relative to risk, although these rates did improve somewhat from the 1990s compared to a decade later.3,4 Cost, access, and health literacy issues also contribute to racial disparities of glaucoma. Unfortunately, these were likely magnified by the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only may Black patients be surgically undertreated, but they are also at increased risk for surgical failure. Additionally, the markedly low numbers of Latinx and Black ophthalmologists in the United States (<2%) may negatively impact physician-patient communication and potentially lower patient trust and satisfaction. However, there is more to the story of identification of glaucoma disparities in populations of both Latinx and African descent than solely such socio-demographic factors.

Figure 1.

US prevalence rates of glaucoma by age and race in 2010

What is Race?

There is no simple definition of race. According to Merriam Webster’s dictionary, race is defined as “any one of the groups that humans are often divided into based on physical traits regarded as common among people of shared ancestry.” In contrast, ethnicity refers to shared culture, such as language, ancestry, practices, and beliefs. Many individuals in the United States and worldwide have a heterogeneous genetic background of “mixed” ancestry representing a great challenge for binary classification. Race classification by self-report on a patient questionnaire is often used in epidemiological studies.5,6 Discrepancies in the evaluation of large population studies highlight questions of proper racial stratification. Self-reports are often unreliable and correlate poorly with true racial origins, affecting the genomic assessment of individuals in identifying disease loci and predicting disease outcomes.7 Accurate identification of ancestral background is critical to truly stratify individuals but is rarely performed in scientific studies. High quality donor DNA may now be utilized to perform genomic ancestral composition detection by microarray analysis. For example, in Missouri, mean African ancestry of self-reported African American (AA) subjects is 75–80%.8

Epidemiology

Large, population-based studies have revealed that glaucoma is more prevalent in Black and Latinx populations.9 In the United States, the Baltimore Eye Survey found that the prevalence of glaucoma in individuals of African descent was six times the levels of the European American (EA) population in some age groups.10 Primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is the leading cause of blindness in the AA population, where it is six times more likely to result in blindness than in EA.11,12 Glaucoma is diagnosed 10 years earlier and shows more rapid progression in the AA population.13 Ocular hypertension, defined as elevated IOP, is the most important and only modifiable risk factor for the development of POAG. This finding occurs 12 years earlier in the AA population, with a higher percentage of Blacks progressing to the development of glaucoma.13 Population-based studies outside of the United States in Barbados, the West Indies and East Africa have also confirmed the high prevalence of glaucoma in those of African descent.14–16 The precise pathogenesis of POAG has not been fully elucidated as it represents a variety of different pathologies, genetic predispositions and contributing environmental factors.

Vascular Disease Considerations

Patients of European descent have lower risk of systemic vascular complications compared to those of African background. Arterial hypertension and arterosclerotic vascular disease may contribute to ocular vascular compromise, and the higher rates of arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus in both Latinx and AA patients likely explains an increased risk of stroke and cardiovascular disease. In contrast, the Barbados Eye Study, predominately consisting of patients of African descent, determined that lower systolic blood pressure and systolic ocular perfusion pressure were predictors of POAG progression.17 Correlations between systolic and diastolic blood pressure with ocular hypertension and glaucoma prevalence are complex and not currently clearly delineated. Associations between diabetes and POAG are also not definitive as studies have shown both increased risk and enhanced protection against the development of glaucoma.18,19

Genetic Studies

Despite abundant data indicating increased prevalence and severity of glaucoma in Black subjects, no definitive physiologic differences have been identified to explain these disparities. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified several genetic mutations linked to glaucoma, yet these currently represent a small percentage of glaucoma cases.20 Several studies indicate genetic contributions to the risk of developing glaucoma by mapping chromosomal regions associated with dominantly inherited risk of open angle glaucoma, including subjects of African descent in Barbados. However, it is not surprising that glaucoma genetic susceptibility alleles in White subjects may not be integral to risk in those of African ancestry.21 GWAS studies of AA individuals included in the ongoing Primary Open-Angle African-American Glaucoma Genetics (POAAGG) study22 are now providing valuable information about family history, gender, and genomic variants in this population.23

Similar GWAS studies in the Latinx population have identified multiple genetic variants associated with glaucoma risk factors of vertical cup-disc ratio and central corneal thickness leading to development of genetic risk scores.24 Causative genetic modifications at these loci have yet to be identified and functions of many genes lying within the mapped intervals are yet unknown. By identifying the physiologic basis of the increased glaucoma risk in individuals of African and Latinx descent, this information could have significant global impact on therapies for this blinding disease. GWAS represent a major advance in genetic research, enabling the assessment of genetic risk factors associated with complex diseases via large-scale, population-based studies. However, GWAS results have limited translational qualities,25 and functional genomics must be coordinated with this data to fill this knowledge gap to enhance understanding of physiology.26 Tissue-specific gene expression and protein transcriptional differences may provide additional insights into the pathophysiology of glaucoma. Differential endothelial cell gene expression by AA vs. EA has identified significantly different stress responses between racial groups.27 This represents an example of how genetic differences may have implications for the role of endothelial cells in addressing racial disparities of vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, cancer, and potentially glaucoma burden in the AA population.

Racial Disparities in Other Diseases May Yield Clues of Biological Differences

Racial disparities exist in several other important diseases, including diabetes mellitus, atherosclerosis, and prostate, colon and breast cancer, with higher incidence and worse prognosis in AA compared to EA individuals. Studies of the molecular basis for disparities in AA men with prostate cancer have revealed differences in androgen receptors, growth factors, and variants of genes of enzymes involved in androgen biosynthesis and metabolism.28 A recent review identified that ethnic differences of genetic variations of nuclear DNA encoding mitochondrial proteins may contribute to cancer disparities.29 Important breakthroughs in genomics, metabolomics and other molecular biotechnologies will facilitate translational research advances to improve our understanding of racial disparities and identification of novel disease mechanisms.

Trabecular Meshwork and IOP Control

The trabecular meshwork (TM) and its specialized cytoskeleton architecture in the anterior chamber (AC) angle are responsible for the drainage of aqueous humor through the conventional outflow system into Schlemm’s canal, ultimately flowing into the episcleral venous system (Figure 2). The physiology and regulation of aqueous humor outflow by the TM cells is not fully understood. Neural control, both muscarinic and adrenergic, actomyosin contractile changes, nitric oxide signaling, and mechanosensitive reflexes play a role in IOP regulation and have been or are currently being studied to expand the pharmacologic treatment of glaucoma. Ultrastructural changes in both the TM and the extracellular matrix, important for the maintainance and integrity of these specialized cells, contribute to IOP dysregulation and subsequent glaucoma development.

Figure 2.

Anatomical image of the eye with focus on anterior chamber angle structures and the aqueous humor outflow pathway.

Oxidative Stress and Glaucoma

Oxidative stress contributes to several systemic and ocular diseases including macular degeneration, uveitis, age-related cataract and glaucoma. As a candidate for its contribution to the pathology of glaucoma, Alvarado et al. suggested that aging and oxidative stress underlie the degeneration of TM cells in glaucoma patients.30 Subsequent studies provide evidence for oxidative damage and reduced resistance to oxidative stress in the outflow pathway and retinal ganglion cell degeneration.31 “Oxidative stress” is defined as an increase over physiologic values in the intracellular concentrations of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The unknown source(s) of oxidative stress may be linked to higher molecular oxygen (pO2) in the anterior chamber (AC) angle that we found in AA eyes compared with EA eyes undergoing cataract and/or glaucoma surgery.32

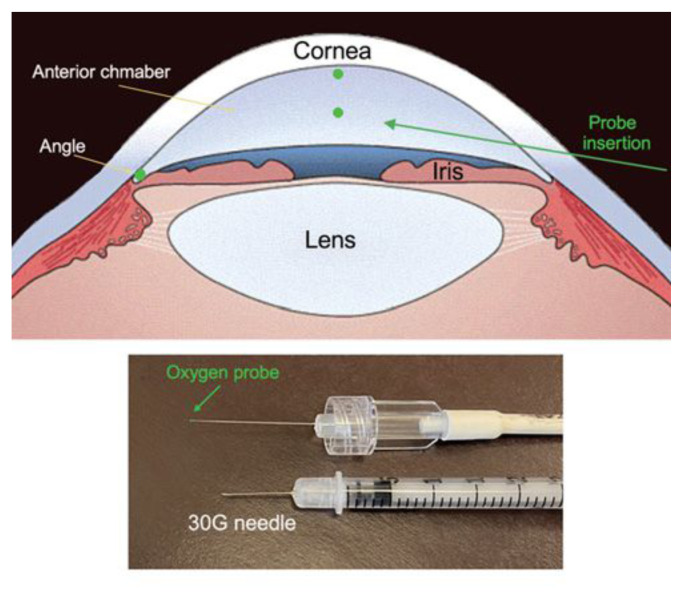

Briefly, an optical oxygen sensor (Oxylab pO2 optode; Oxford Optronix, Oxford, England) was introduced throught a 30-gauge needle entry track. The tip of the flexible fiberoptic probe was positioned for three measurements in all patients (1) near the central corneal endothelium, (2) in the mid-AC, and (3) in the AC angle (Figure 3). We also discovered a correlation of pO2 in the AC angle with thinner central corneas, an established independent risk factor for development and progression of POAG.33 Notably, AA individuals have thinner corneas as compared to EA.34 The greater oxygen concentration in the aqueous humor outflow pathway may be a source or byproduct of ROS, depleting antioxidant defenses. Its contribution to the risk of developing glaucoma requires further study.35 Additionally, oxidative damage to DNA is greater in TM cells in glaucoma patients compared to controls and correlates with both IOP level and visual field loss.36 AA patients have increased levels of systemic oxidative stress compared to EA, following adjustment for differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors and inflammation.37 However, many studies of oxidative stress do not include or consider effects of diverse racial background as they recruit from EA populations, nor consistently include consideration of sex differences, metabolic disease or smoking history.

Figure 3.

Locations of pO2 measurements in the human eye in vivo during ophthalmic surgery (upper image) Oxygen probe used for measurements shown with 30G needle for entry through peripheral cornea (lower image)

Gene Expression in Trabecular Meshwork

As noted above, exploring “deeper” into gene expression and protein composition of tissues may provide greater information of specific disease processes as compared to whole genome analyses. Looking further into this concept of oxidative stress, we evaluated specimens of TM from patients with glaucoma obtained during glaucoma surgery. Assessment by RNA-sequencing identified different levels of gene expression comparing AA and EA patients. Specifically, the most highly significant gene expression differences were identified in genes encoding for mitochondrial elements, with nearly all displaying upregulation in AA subjects compared to EA. Although the mechanism/physiologic consequence of these gene differences is unknown, this finding may help explain differences in oxygen metabolism in AA.32,38 Upregulation of these key mitochondrial components of oxidative phosphorylation complexes may indicate compensatory mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction in AA patients. A complex I defect is associated with glaucomatous TM cell degeneration and complex I mitochondrial gene mutations have been verified in POAG as well as dysfunctional mitochondrial calcium regulation.39,40 However, racial impact on these findings has not been studied. Our preliminary results suggest that racial differences in mitochondrial protein gene expression profiles may explain differences in oxygen consumption and intracellular ROS metabolism. We continue to explore these findings by studying ATP synthesis, ROS production and antioxidant defense mechanisms in TM cells from AA compared to EA. In this manner, we may verify the significance and therapeutic potential of mitochondrial-targeted antioxidants as novel therapies for glaucoma.

Conclusions

There is strong evidence that both race and social determinants of health and disease greatly impact the prevalence and outcomes for patients with many systemic conditions, including primary open angle glaucoma. It is crucial that, as health care professionals and scientists, we thoroughly study and increase our understanding of the underlying epidemiologic factors of socio-economic status, health literacy, cultural sensitivity, and community care influences on disease disparities. Importantly, we must also rigorously study the scientific aspects of these disease differences of prevalence, rates of progression, and blindness. Both genetic studies of disease risk factors and pathophysiologic mechanisms must include subjects of diverse backgrounds in order to better delineate individual risk and disease mechanisms as we look forward to the development of future precision therapies.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant to the John F. Hardesty MD Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness and funded by the National Eye Institute (R01EY021515).

Footnotes

Carla J. Siegfried, MD, (above), and Ying-Bo Shui, MD, PhD, are in the John F. Hardesty MD Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences, Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri.

Disclosure

This work was supported by an unrestricted grant to the John F. Hardesty MD Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences from Research to Prevent Blindness and funded by the National Eye Institute (R01EY021515).

References

- 1.Smedley BDSA, Nelson AR, editors. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington DC: Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Murakami Y, Lee BW, Duncan M, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in adherence to glaucoma follow-up visits in a county hospital population. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(7):872–8. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Coleman AL, Yu F, Rowe S. Visual field testing in glaucoma Medicare beneficiaries before surgery. Ophthalmology. 2005;112(3):401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stein JD, Talwar N, Laverne AM, Nan B, Lichter PR. Racial disparities in the use of ancillary testing to evaluate individuals with open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130(12):1579–88. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mersha TB, Abebe T. Self-reported race/ethnicity in the age of genomic research: its potential impact on understanding health disparities. Hum Genomics. 2015;9:1. doi: 10.1186/s40246-014-0023-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Parra FC, Amado RC, Lambertucci JR, Rocha J, Antunes CM, Pena SD. Color and genomic ancestry in Brazilians. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(1):177–82. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0126614100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rotimi CN, Jorde LB. Ancestry and disease in the age of genomic medicine. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1551–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0911564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bryc K, Durand EY, Macpherson JM, Reich D, Mountain JL. The genetic ancestry of African Americans, Latinos, and European Americans across the United States. Am J Hum Genet. 2015;96(1):37–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kosoko-Lasaki O, Gong G, Haynatzki G, Wilson MR. Race, ethnicity and prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(10):1626–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tielsch JM, Sommer A, Katz J, Royall RM, Quigley HA, Javitt J. Racial variations in the prevalence of primary open-angle glaucoma. The Baltimore Eye Survey JAMA. 1991;266(3):369–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Javitt JC, McBean AM, Nicholson GA, Babish JD, Warren JL, Krakauer H. Undertreatment of glaucoma among black Americans. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(20):1418–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199111143252005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Munoz B, West SK, Rubin GS, et al. Causes of blindness and visual impairment in a population of older Americans: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(6):819–25. doi: 10.1001/archopht.118.6.819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wilson R, Richardson TM, Hertzmark E, Grant WM. Race as a risk factor for progressive glaucomatous damage. Ann Ophthalmol. 1985;17(10):653–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Leske MC, Connell AM, Schachat AP, Hyman L. The Barbados Eye Study. Prevalence of open angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112(6):821–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1994.01090180121046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mason RP, Kosoko O, Wilson MR, et al. National survey of the prevalence and risk factors of glaucoma in St. Lucia, West Indies. Part I. Prevalence findings. Ophthalmology. 1989;96(9):1363–8. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(89)32708-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Buhrmann RR, Quigley HA, Barron Y, West SK, Oliva MS, Mmbaga BB. Prevalence of glaucoma in a rural East African population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(1):40–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Leske MC, Wu SY, Hennis A, Honkanen R, Nemesure B, Group BES. Risk factors for incident open-angle glaucoma: the Barbados Eye Studies. Ophthalmology. 2008;115(1):85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Quigley HA, West SK, Rodriguez J, Munoz B, Klein R, Snyder R. The prevalence of glaucoma in a population-based study of Hispanic subjects: Proyecto VER. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(12):1819–26. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.12.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gordon MO, Beiser JA, Kass MA, Ocular Hypertension Treatment, Study G. Is a history of diabetes mellitus protective against developing primary open-angle glaucoma? Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;126(2):280–1. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2007.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wiggs JL, Pasquale LR. Genetics of glaucoma. Hum Mol Genet. 2017;26(R1):R21–R7. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddx184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu Y, Hauser MA, Akafo SK, et al. Investigation of known genetic risk factors for primary open angle glaucoma in two populations of African ancestry. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(9):6248–54. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-12779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Charlson ES, Sankar PS, Miller-Ellis E, et al. The primary open-angle african american glaucoma genetics study: baseline demographics. Ophthalmology. 2015;122(4):711–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Collins DW, Gudiseva HV, Chavali VRM, et al. The MT-CO1 V83I Polymorphism is a Risk Factor for Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma in African American Men. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018;59(5):1751–9. doi: 10.1167/iovs.17-23277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Nannini DR, Kim H, Fan F, Gao X. Genetic Risk Score Is Associated with Vertical Cup-to-Disc Ratio and Improves Prediction of Primary Open-Angle Glaucoma in Latinos. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(6):815–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marian AJ. Molecular genetic studies of complex phenotypes. Transl Res. 2012;159(2):64–79. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Iglesias AI, Springelkamp H, Ramdas WD, Klaver CC, Willemsen R, van Duijn CM. Genes, pathways, and animal models in primary open-angle glaucoma. Eye (Lond) 2015;29(10):1285–98. doi: 10.1038/eye.2015.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wei P, Milbauer LC, Enenstein J, Nguyen J, Pan W, Hebbel RP. Differential endothelial cell gene expression by African Americans versus Caucasian Americans: a possible contribution to health disparity in vascular disease and cancer. BMC Med. 2011;9:2. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hatcher D, Daniels G, Osman I, Lee P. Molecular mechanisms involving prostate cancer racial disparity. Am J Transl Res. 2009;1(3):235–48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Choudhury AR, Singh KK. Mitochondrial determinants of cancer health disparities. Semin Cancer Biol. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alvarado J, Murphy C, Polansky J, Juster R. Age-related changes in trabecular meshwork cellularity. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;21(5):714–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kong GY, Van Bergen NJ, Trounce IA, Crowston JG. Mitochondrial dysfunction and glaucoma. J Glaucoma. 2009;18(2):93–100. doi: 10.1097/IJG.0b013e318181284f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Siegfried CJ, Shui YB, Holekamp NM, Bai F, Beebe DC. Racial differences in ocular oxidative metabolism: implications for ocular disease. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129(7):849–54. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2011.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Siegfried CJ, Shui YB, Bai F, Beebe DC. Central corneal thickness correlates with oxygen levels in the human anterior chamber angle. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015;159(3):457–62e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2014.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mercieca K, Odogu V, Fiebai B, Arowolo O, Chukwuka F. Comparing central corneal thickness in a sub-Saharan cohort to African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans. Cornea. 2007;26(5):557–60. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3180415d90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sacca SC, Izzotti A. Oxidative stress and glaucoma: injury in the anterior segment of the eye. Prog Brain Res. 2008;173:385–407. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)01127-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sacca SC, Pascotto A, Camicione P, Capris P, Izzotti A. Oxidative DNA damage in the human trabecular meshwork: clinical correlation in patients with primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(4):458–63. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.4.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Morris AA, Zhao L, Patel RS, et al. Differences in systemic oxidative stress based on race and the metabolic syndrome: the Morehouse and Emory Team up to Eliminate Health Disparities (META-Health) study. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2012;10(4):252–9. doi: 10.1089/met.2011.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Eynon N, Moran M, Birk R, Lucia A. The champions’ mitochondria: is it genetically determined? A review on mitochondrial DNA and elite athletic performance. Physiol Genomics. 2011;43(13):789–98. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00029.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kamel K, Farrell M, O’Brien C. Mitochondrial dysfunction in ocular disease: Focus on glaucoma. Mitochondrion. 2017 doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sundaresan P, Simpson DA, Sambare C, et al. Wholemitochondrial genome sequencing in primary open-angle glaucoma using massively parallel sequencing identifies novel and known pathogenic variants. Genet Med. 2015;17(4):279–84. doi: 10.1038/gim.2014.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]