Abstract

Background:

People experiencing homelessness are vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection and its consequences. We aimed to understand the perspectives of people experiencing homelessness, and of the health care and shelter workers who cared for them, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

We conducted an interpretivist qualitative study in Toronto, Canada, from December 2020 to June 2021. Participants were people experiencing homelessness who received SARS-CoV-2 testing, health care workers and homeless shelter staff. We recruited participants via email, telephone or recruitment flyers. Using individual interviews conducted via telephone or video call, we explored the experiences of people who were homeless during the pandemic, their interaction with shelter and health care settings, and related system challenges. We analyzed the data using reflexive thematic analysis.

Results:

Among 26 participants were 11 men experiencing homelessness (aged 28–68 yr), 9 health care workers (aged 33–59 yr), 4 health care leaders (aged 37–60 yr) and 2 shelter managers (aged 47–57 yr). We generated 3 main themes: navigating the unknown, wherein participants grappled with evolving public health guidelines that did not adequately account for homeless individuals; confronting placelessness, as people experiencing homelessness often had nowhere to go owing to public closures and lack of isolation options; and struggling with powerlessness, since people experiencing homelessness lacked agency in their placelessness, and health care and shelter workers lacked control in the care they could provide.

Interpretation:

Reduced shelter capacity, public closures and lack of isolation options during the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the displacement of people experiencing homelessness and led to moral distress among providers. Planning for future pandemics must account for the unique needs of those experiencing homelessness.

Homelessness has been an intractable problem in Canada, the United States and elsewhere for decades. Every night, an estimated 35 000 Canadians1 and more than 500 000 Americans2 are homeless. Most live in shelters, are adult men1 and have chronic mental and physical health conditions that put them at risk for COVID-19 complications. 3–5 Shelter residents have been particularly vulnerable to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Physical distancing, maintaining hygiene, obtaining SARS-CoV-2 testing and isolating when symptomatic are all difficult in shelter settings. Indeed, many shelters have had outbreaks during the pandemic, often with asymptomatic spread;6–8 these outbreaks have continued despite high rates of vaccination in the general population.9 Research has found that people experiencing homelessness are not just more likely to test positive for SARS-CoV-2 but also to experience complications and die from the infection.10

As system leaders reflect on the lessons from the pandemic, it is important to learn from the lived experience of people who were homeless and those who cared for them.11 Some qualitative research has begun to explore the impact of COVID-19 on access to hand hygiene facilities,12 health-related resources13 and primary care14 for the homeless population, as well as their experiences in the first months of the pandemic15 or during periods of lockdown.16 However, few qualitative studies have explored the impact of pandemic policies and procedures on people experiencing homelessness in North America. We sought to understand the perspectives of people experiencing homelessness who interacted with emergency departments, testing centres and shelters during the first 12–15 months of the COVID-19 pandemic (the first 3 waves in Ontario), as well as the perspectives of the health care workers and homeless shelter staff who cared for them and bore witness to their experiences.

Methods

Study design and setting

We conducted an interpretivist qualitative study,17 employing reflexive thematic analysis,18 to understand participants’ experiences of the pandemic and the meanings they assigned to them. Interviews were conducted between December 2020 and June 2021, when Toronto had stringent public health restrictions, including city-wide lockdown measures (i.e., closure of many public spaces and stay-at-home orders).19–21

Toronto is Canada’s largest city, with an estimated 8715 people experiencing homelessness in 2018, 80% of whom live in the city’s 75 shelter sites.22 Our study included participants who worked or lived at or near St. Michael’s Hospital, located close to many shelters downtown. On Mar. 16, 2020, St. Michael’s opened one of Ontario’s COVID-19 Assessment Centres (CACs), providing free COVID-19 testing to members of the public. The CAC was open during daytime hours (7 days a week, 8 am–8 pm from March to August 2020; 8 am–6 pm September 2020 to June 2021); people were directed to the St. Michael’s emergency department if they required a test after hours or needed a more thorough medical assessment. Beginning on Apr. 23, 2020, the St. Michael’s CAC and community partners began doing mobile outreach testing at local shelters under the direction of public health authorities.6

The study was reported using the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) checklist.23

Participants and recruitment

We focused on 4 groups of participants, namely people experiencing homelessness who had received SARS-CoV-2 testing through shelter outreach, health care workers who worked in the emergency department or CAC, health care leaders who oversaw CAC or emergency department operations during the pandemic and managers of homeless shelters where mobile testing occurred.

We used convenience sampling to recruit people experiencing homelessness who received mobile outreach testing through St. Michael’s Hospital and who consented to be contacted for future research opportunities. We contacted them by telephone and invited them to participate in this study. We also contacted representatives at shelters involved in mobile testing and asked them to share recruitment flyers with people who had consented; flyers instructed shelter residents to contact the study team. We scheduled telephone interviews with everyone who agreed to participate.

We used a mix of purposive and convenience sampling24 to recruit the remaining participants. We identified 4 health care leaders who were involved in the initial planning and implementation of St. Michael’s Hospital’s COVID-19 response and invited them to participate via email. We then asked them to recommend health care workers in the CAC and emergency department who supported people experiencing homelessness and to send recruitment emails to those individuals, and their teams, on our behalf. Two authors (K.H. and A.C.-N.) also sent recruitment emails to managers and directors of 4 shelters who were involved in mobile testing. Where possible, we selected participants to maximize diversity in roles and experiences (i.e., inclusion of physicians, nurses, peer support workers and administrative support staff, with representation from the CAC and emergency department). All participants, except health care leaders, were given gift cards as honorariums.

Data collection

Using in-depth individual interviews (conducted by K.H., J.P. and C.J.-P., female researchers), we explored participants’ perspectives of SARS-CoV-2 testing, the procedures surrounding testing and the broader challenges facing people experiencing homelessness during the pandemic. Interviews were conducted online via video call or by telephone, and were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The team created interview guides (Appendix 1, available at www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/3/E685/suppl/DC1), guided by the research question and tailored to each participant group. The interview guide for participants experiencing homelessness was reviewed by 4 individuals with lived experience of homelessness who were members of a Community Expert Group. This standing group was created under the auspices of the MAP Centre for Urban Health Solutions to provide guidance and advice on research related to homelessness, housing and health.

Data analysis

We concurrently generated and analyzed data using reflexive thematic analysis,18,25,26 which involves reading the transcripts, inductively coding the data and grouping the codes into interpretive themes reflecting commonalities in participants’ experiences. One author (K.H.) led the analysis, in collaboration with two others (J.P. and C.J.-P.), all experienced qualitative researchers. The full team included clinicians, methodologists and content experts, many of whom have experience caring for homeless populations or conducting research in this area.

One author (K.H.) first coded the data by participant group using NVivo and brought initial codes and reflections to J.P. and C.J.-P. for discussion, who had also coded a subset of the transcripts. As the coding framework developed, K.H. then generated cross-cutting themes through constant comparison of the data (within and across groups) and iterative analytical discussions with J.P. and C.J.-P. Theme descriptions and accompanying codes were presented to the remaining authors for additional interpretation and refinement. The themes were iteratively updated, and data collection and analysis continued until the team agreed we had reached informational and meaning sufficiency27 (i.e., new data bolstered our current themes rather than suggesting new themes). We engaged in reflexivity throughout this process, continuously questioning our assumptions and viewing the data from multiple perspectives.18,27

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was granted by the Unity Health Toronto Research Ethics Board.

Results

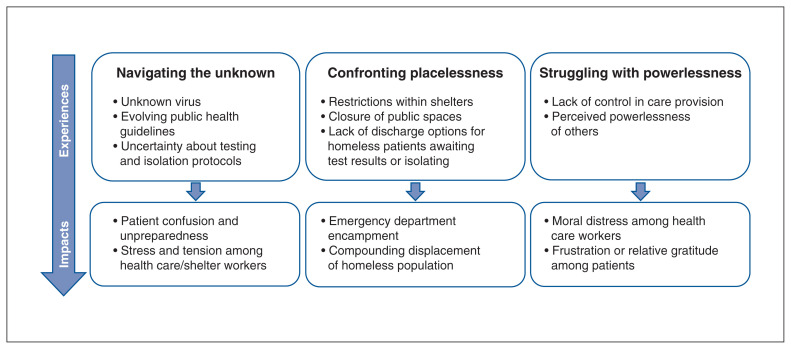

We interviewed 26 participants, including 11 people experiencing homelessness residing at 1 of 3 shelters; 9 health care workers involved in SARS-CoV-2 testing, including physicians, nurses, clinical support staff and administrative support staff; 4 health care leaders; and 2 managers of homeless shelters (Table 1). Interviews with people experiencing homelessness were conducted by telephone; the rest were conducted by video call. Interviews were 30–60 minutes in length. We generated 3 cross-cutting themes from the interview data: navigating the unknown, confronting “placelessness” and struggling with powerlessness, depicted in Figure 1 and described below. Supporting quotes for each theme appear in Boxes 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1:

Participant demographic characteristics

| Characteristic | Patients n = 11 |

Health care workers n = 9 |

Health care leaders n = 4 |

Shelter managers n = 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yr, range | 28–68 | 33–59 | 37–60 | 47–57 |

| Gender, male, no. (%) | 11 (100) | 4 (44) | 2 (50) | 1 (50) |

Figure 1:

Experiences and impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on people experiencing homelessness. Bullets represent main concepts that constitute each theme.

Box 1: Supporting quotes for theme: navigating the unknown .

We were all in the dark. Nobody had any idea what to anticipate and the whole world shut down. (HCW 05)

It was very worrying, to be honest with you. We didn’t know what to expect. We didn’t know how it was going to impact the homeless. What we did know, though, is that if [COVID-19] got into the homeless population, and in particular into our [shelter], the transmission would go through the place very quickly if we didn’t do anything. (Shelter manager 01)

One of the first things that was talked about was physical distancing. So what do you do when you’ve got a congregate setting of almost 600 people in dorm style? … What does it look like to isolate somebody who [has a history of substance use] or who has a psychotic disorder or who has liver failure or who’s in our managed alcohol program? It’s not so easy. (Shelter manager 02)

It was changing on the fly all the time. You could barely keep up with how it was working. (HCW 09)

Everyone just didn’t quite understand what their role was. You know, what are we supposed to do? It was sort of on the fly that we were trying to help. But I think that others felt frustrated by “What is our role here? Should we be doing this? Is there someone who’s better to be doing this?” (HCW 07)

And then [we] dealt with “where does this patient go?” So we’ll just put them in our waiting room to wait, but it put a lot of pressure on the emergency department … we didn’t know where to send people because there was no real clear communication [about that]. (HCW 09)

It was a pretty crazy time. You would call a shelter … and they were in dire straits … I remember having conversations with people where I’m just trying to talk them off the ledge, over the phone. And it’s not even the patient. Like, I’m dealing with staff. It was really scary. It was a pretty tough time. (HCW 05)

The emergency department at the time felt a bit like a ticking time bomb. It was tense. Because there were a lot of people [there], and we didn’t know that much about the virus, none of us were vaccinated at the time … . It was a stressful period, that’s for sure. (HCW 08)

I spent a lot of time on the phone with the front line shelter worker that was trying to manage the emotions of people at the front door of her place. And we were managing the understandable anger and frustration of the clients that were here in our emergency department. And we literally ran out of room that night. And that was probably the most scary night … . What’s very clear to me is how vulnerable you are at the front line and how unfair this is to our joint clients or patients. (Health care leader 04)

The situation, it’s really putting us against the wall. So, you know, you can’t beat everybody up because of that situation … Canada can’t do anything more than what they’re doing right now. (PEH 04)

Note: HCW = health care worker, PEH = person experiencing homelessness.

Box 2: Supporting quotes for theme: confronting placelessness .

The ED basically became an area that took over lodging and feeding of people that were homeless who were not able to go to the shelter system anymore because there [were] concerns that they were infected with COVID [-19] or that they were in close contact [with someone who was]. And early in the pandemic, the infrastructure wasn’t set up for the city to manage homeless shelters … so it ended up falling on the [COVID-19 Assessment Centre], of which then it sort of fell back on the Emerg. (Health care leader 02)

So many barriers were put in the way of the homeless … . Their usual places like coffee shops, the mall, the library, places where they could go and rest and get out of the extreme weather were all closed and taken away from them … . And it’s still an issue today … . So the people with no fixed address have nowhere to go during the day. (Shelter manager 01)

The general order is stay at home. [But] what if you don’t have a home to stay? (PEH 05)

They have the atrium … where we can hang out … . Well now they closed that off for the mornings because the cleaners … [so] now we don’t have access to that until 9:00 in the morning, which means all the guys are crammed even closer now [in the hallway] because they have even less places to go … it makes it an even worse scenario for everybody to get sick. (PEH 07)

When you’re in a shelter, you’re allowed to be inside for a certain period of time and you’ve got to be out for a certain period of time. Well, where do you go? Everything’s closed. (PEH 11)

I used to go to the community centre … I used to do the weight room, the gym, the basketball courts and stuff like that. A lot of stuff is not available anymore. And even a friend of mine, he said he went to take his kids out to play the other day, they won’t even allow [them] to play outside, and it was an outdoor park you know. That’s how bad it is right now. (PEH 07)

Like the computer room, we used to be able to go on the computer for housing or jobs. And that’s closed because it’s a small area. (PEH 03)

For somebody who was homeless and living on the streets, it became a really dire situation for them. They were already in a crisis situation, and then on top of that, you’re compounding all these other issues where they can’t access their caseworkers, they can’t access mental health, they can’t access their medications … . They can’t access their family doctors. They can’t make phone calls and do zoom appointments. They can’t access the Internet. They have no access to food. There’s no access to clothing or showers. It really started to pile up and it was a pretty tough time. (HCW 05)

People dealing with severe mental health issues, with trauma, with substance abuse issues … . One of the important things that keeps those people stable, to some extent … [is] connections … . Once COVID [-19] shut everything down … all of those folks weren’t able to connect with the life that they built. (HCW 06)

Note: ED = emergency department, HCW = health care worker, PEH = person experiencing homelessness.

Box 3: Supporting quotes for theme: struggling with powerlessness .

Every kind of homeless-serving agency but shelters shut down … . Everything closed. The whole city shut down and then it was hospitals and us. It just felt like we were alone in the world. (Shelter manager 02)

The patient might have been going through severe withdrawal … and once that was taken care of, the person was put into a makeshift shelter [in the ED] and we sort of looked after them that way. But really “looking after them” was you maybe hand them a meal or you spoke to them from a distance to say, “Hey, do you need anything?”… . But they couldn’t leave, they couldn’t go anywhere … . It was horrible. (HCW 06)

If we were at max capacity, and somebody came in and their COVID [-19] swab came back negative, we still were not able to obtain a shelter but we basically had no other choice but to discharge them … . And it became very difficult and disheartening at times. (HCW 05)

People with mental health issues rapidly decompensated because their supports were taken away … . We could see people getting more and more sick on the streets, decompensating, knowing that the only thing we could do is call the police and tell them we need a mental health team to respond. (Shelter manager 01)

We were the messenger, and that was hard. Because understandably, [patients] were extremely angry. But underneath that anger was fear. … And we were managing that in a space where we, too, felt really overwhelmed by the responsibility, that we were the last resort. (Health care leader 04)

Every time we saw someone at the COVID [-19] Centre that came for a test and perhaps they weren’t aware that they were going back to their shelter because, until they received the results, they were not welcome back. So often we were the folks telling them, “Hey, listen, you’re not going back to your home. You are staying with us. We actually don’t know where you’re going to go. You might need to stay at the emergency department. We don’t know how long you’re going stay there.” … Those are some of the biggest challenges I think we experienced. (Health care leader 01)

We in the emergency department ended up having to convert spaces that were never meant for patient care into patient care spaces. … It was very difficult for me as a leader who believes very strongly in equity to see the environments where people had to stay in our emergency department. And it was not something we were proud of, being the only option, because it is not fair for somebody to have to stay in a storeroom for 7 days. (Health care leader 03)

There’s a culture here [in the shelter]. … If you want to start complaining, it feels like, because they are in charge of some of the grants for our rent, housing, they feel like we cannot do nothing about it … they feel like we don’t have a voice. And at the same time, you don’t want to get kicked out of here. … And that’s why I was struggling. (PEH 08)

They [shelter staff] shushed us away the other day. We were just trying to talk, trying to have a place where we can sit and have meetings, there’s 3 or 4 of us trying to start something … and they just shushed us away. (PEH 09)

I never have any serious problems with anything here, with what the shelter has to offer. They’re doing the best they can with what they have. … They’re helping me out as best they can, and I’m grateful for that. (PEH 03)

Note: HCW = health care worker, PEH = person experiencing homelessness.

Navigating the unknown

Participants spoke about the overwhelming uncertainty they felt, particularly in the early months of the pandemic. Health care workers and shelter managers highlighted how knowledge of the virus and ways to confront it were constantly evolving, along with relevant public health guidance. Shelter managers also expressed their uncertainty in how to follow directives that did not easily apply in their context, such as enforcing physical distancing in dorm room settings or isolating people with substance abuse or mental health issues.

Hospital leaders described the uncertainty they faced developing processes when “there was really no rulebook” (Health care leader 01). Health care workers who needed to follow these protocols noted how directives changed rapidly, leaving them unsure how to respond on a given day. They also described problem solving in the absence of clear guidelines, most notably supporting people experiencing homelessness who could not self-isolate.

Health care workers noted that people experiencing homelessness were often unaware of protocols, and would sometimes arrive at the testing centre or hospital not knowing they would be unable to return to their shelter while awaiting test results. Participants experiencing homelessness also depicted navigating this uncertainty, where usual activities, spaces and routines were all changed as a result of pandemic restrictions. They also expressed recognizing the challenges of health care workers and shelter staff during this time.

In trying to provide safe and effective care amidst so many unknowns, health care workers and shelter staff spoke about the intense stress they had early in the pandemic, with one describing the emergency department as a “ticking time bomb” (Health care worker 08).

Confronting “placelessness”

Participants highlighted the pervasive “placelessness” of people experiencing homelessness throughout the pandemic. This was most acute in the early pandemic, when test results could take 3–7 days and health care workers needed to make space in the emergency department for patients to stay while awaiting results. The emergency department became a makeshift encampment for people experiencing homelessness who were not able to return to their shelters because they may have been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 but had nowhere else to go.

Participants experiencing homelessness spoke about a broader sense of displacement they felt throughout the pandemic owing to physical restrictions both inside and outside their shelters. In shelters, certain common rooms were closed and bedrooms sometimes needed to be vacated for extended periods for enhanced cleaning protocols. This reportedly led to residents congregating in hallways while bedrooms and common spaces were inaccessible. They recognized that this had important implications for their own and others’ safety. They noted being limited in where they could go outside their shelters at this time given widespread closures of public places. Health care workers commented that ongoing public closures exacerbated the vulnerability of people experiencing homelessness by reducing access to other health care or social supports.

One participant noted that these closures not only limited people’s access to services but potentially destabilized them psychologically, as the physical and emotional connections that constituted their lives were suddenly unavailable to them. Some participants linked the cumulative impact of such destabilization to increased mental health issues and opioid-related deaths among shelter residents. Some also noted that many of these were long-standing issues but were exacerbated and illuminated by the pandemic.

Struggling with powerlessness

Health care workers spoke extensively about the lack of control they felt in providing adequate care for patients experiencing homelessness, noting the tension they felt in the care they could offer versus the care they wished they could give. One participant described the distress of needing to discharge patients once the emergency department reached capacity, even if they did not have anywhere else to go. Shelter managers also conveyed their lack of control in effectively serving residents, particularly those with mental health issues, given the lack of supports available to them.

Ultimately, these participants felt limited in their abilities, as if they were “caught in the middle of the process” (Health care worker 07), without agency. Many health care workers conveyed feeling overwhelmed and powerless during this time. Moreover, they spoke about the psychological toll of witnessing patients’ powerlessness throughout the pandemic.

In contrast, participants experiencing homelessness described a different kind of powerlessness. They spoke relatively positively about health care interactions, noting that the testing they received at their shelters was “very straightforward” (Person experiencing homelessness 08) and that they had “no complaints” (Person experiencing homelessness 05) about staying in an isolation hotel. However, some expressed frustration about the ongoing restrictions and general atmosphere within shelters, conveying a sense of powerlessness there. Others, conversely, spoke positively of their shelter experience and seemed to recognize the powerlessness of shelter staff during this time. When asked about what other supports might help people experiencing homelessness during a pandemic, most could not identify any, instead conveying a sense of relative gratitude for their situation.

Interpretation

For years, our health and social systems have struggled to meet the needs of people experiencing homelessness. Our qualitative study provides a nuanced picture of how the pandemic heightened existing challenges. Participants described how the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the placelessness of an already destabilized population. With the closure of public spaces and restrictions within shelter settings, people experiencing homelessness had nowhere to go. Early on, shelter residents who required self-isolation often ended up with unplanned overnight stays in the emergency department because there were no other systems in place. Both people experiencing homelessness and providers felt they were left to navigate the uncertainty of the pandemic on their own and felt powerless in their situation. Shelter and health care workers described directives and resource constraints that prevented them from delivering the kind of care they wanted to provide.

Our findings are consistent with other research that has highlighted the compounding marginalization of homeless populations during the pandemic. People experiencing homelessness were more likely to acquire SARS-CoV-2, become seriously ill and die from the infection.15,28 Others have also described increased food insecurity owing to widespread closures, 15 a loss of “place” amidst restrictions and distanced services, 29 a rise in overdose deaths,30 and increased fear, confusion and uncertainty.15,29 In some regions, vaccinations have been slow to reach people living in shelters, leading to outbreaks even as other parts of the population were protected.9

Health care workers and shelter staff in our study faced an emotional toll from trying to care for patients experiencing homelessness within a system that did not adequately support their efforts. Other researchers have described the adverse psychological impacts of COVID-19 on front-line health care workers28,31–35 and the rise of moral distress — being unable to take the right or ethical course of action because of institutionalized obstacles.36–39 Moral distress can lead to burnout38 and intention to resign,39 both notable trends in recent surveys.40,41 These effects on the workforce may make it even more challenging for people experiencing homelessness to receive the care they need in the future. In our study, people experiencing homelessness seemed less distressed about their circumstances than those caring for them, which may relate to differing expectations.

Our findings highlight that our society needs to do better to meet the needs of people experiencing homelessness, now and in future pandemics. Participants spoke about some of the system changes required, including better communication and collaboration between stakeholders, centralized oversight of the response, more mental health and addiction supports and, most importantly, housing integrated with social supports. These suggestions should be explored in future research that guides pandemic planning. On the one hand, the pandemic has exposed the limitations of shelters as even a temporizing solution to homelessness. On the other hand, it has shown us that we can use existing infrastructure, such as unused hotel rooms, to rapidly house people.42 Ultimately, a better pandemic response would include creative solutions to end homelessness.43

Limitations

We focused on the experiences of participants in 1 geographic region and were only able to recruit male participants experiencing homelessness, which limits the generalizability of our findings. There were temporal differences in what participants explored in their interviews, which may have affected thematic sufficiency; some highlighted early pandemic experiences while others reflected on circumstances at the time of the interview, almost 1 year into the pandemic.

Conclusion

Participants experiencing homelessness reported having nowhere to go during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic given public closures and restrictions. Caring for this population amidst resource constraints led to moral distress among health care and shelter workers. Planning for future pandemics needs to account for the unique needs of people experiencing homelessness and include advocacy for policy solutions to end homelessness altogether.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Carolyn Snider for her input into the study design and leadership in the emergency department during COVID-19 and the Community Expert Group who informed our interviews with people with lived experience of homelessness. They also thank those who led pandemic efforts, including leaders in the emergency department and COVID-19 Assessment Centre at St. Michael’s Hospital and in the outreach testing in shelters done in partnership with Sherbourne Health Centre, and shelter staff for their tireless work. Finally, the authors thank the participants who shared their time and experiences with the research team.

Footnotes

Competing interests: Stephen Hwang reports grants from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and participation on the data safety monitoring board for a study on smoking cessation. He has roles with the board of directors of Good Shepherd Ministries, the research committee of the National Health Care for the Homeless Council and with Inner City Health Associates. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Esther Rosenthal, Stephen Hwang, Joel Lockwood, Paul Das and Tara Kiran conceived the study. All authors helped design the study. Kathryn Hodwitz, Janet Parsons and Clara Juando-Pratts collected and analyzed the data. Kathryn Hodwitz, Janet Parsons, Clara Juando-Pratts, Esther Rosenthal, Stephen Hwang, Joel Lockwood and Tara Kiran interpreted the data. Kathryn Hodwitz and Tara Kiran drafted the manuscript and all authors critically reviewed it. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was supported by a grant from the St. Michael’s Hospital Foundation. The study sponsor had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data, manuscript preparation or the decision to submit for publication. Tara Kiran is the Fidani Chair in Improvement and Innovation at the University of Toronto. She is supported as a clinician scientist by the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Toronto and at St. Michael’s Hospital.

Data sharing: The data in this study cannot be made available owing to participant privacy and confidentiality.

Supplemental information: For reviewer comments and the original submission of this manuscript, please see www.cmajopen.ca/content/10/3/E685/suppl/DC1.

References

- 1.Gaetz S, Dej E, Richter T, et al. The state of homelessness in Canada 2016. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness Press; 2016. [accessed 2021 Sept. 20]. Available: https://www.homelesshub.ca/SOHC2016. [Google Scholar]

- 2.2019 AHAR: Part 1 - PIT estimates of homelessness in the U.S. Washington (DC): US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2020. [accessed 2021 Sept. 20]. Available: https://www.hudexchange.info/resource/5948/2019-ahar-part-1-pit-estimates-of-homelessness-in-the-us/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tsai J, Wilson M. COVID-19: a potential public health problem for homeless populations. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5:e186–7. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30053-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perri M, Dosani N, Hwang SW. COVID-19 and people experiencing homelessness: challenges and mitigation strategies. CMAJ. 2020;192:E716–9. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. Permanent supportive housing: evaluating the evidence for improving health outcomes among people experiencing chronic homelessness; accessed 2021 Dec. 19; Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2018. Available https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519594/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK519594.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiran T, Craig-Neil A, Das P, et al. Factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 positivity in 20 homeless shelters in Toronto, Canada, from April to July 2020: a repeated cross-sectional study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:E302–8. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baggett TP, Keyes H, Sporn N, et al. Prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in residents of a large homeless shelter in Boston. JAMA. 2020;323:2191–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mosites E, Parker EM, Clarke KEN, et al. COVID-19 Homelessness Team. Assessment of SARS-CoV-2 infection prevalence in homeless shelters: four US cities, March 27–April 15, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:521–2. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6917e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nielsen K. 76 COVID-19 cases now connected to outbreak in Waterloo Region congregate setting. Global News. 2021. Jun 14, [accessed 2021 Dec. 19]. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/7948916/covid-19-outbreak-waterloo-region-congregate-setting/

- 10.Richard L, Booth R, Rayner J, et al. Testing, infection and complication rates of COVID-19 among people with a recent history of homelessness in Ontario, Canada: a retrospective cohort study. CMAJ Open. 2021;9:E1–9. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20200287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teti M, Schatz E, Liebenberg L. Methods in the time of COVID-19: the vital role of qualitative inquiries. Int J Qual Methods. 2020:19. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montgomery MP, Carry MG, Garcia-Williams AG, et al. Hand hygiene during the COVID-19 pandemic among people experiencing homelessness: Atlanta, Georgia, 2020. J Community Psychol. 2021;49:2441–53. doi: 10.1002/jcop.22583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Allaria C, Loubière S, Mosnier E, et al. “Locked down outside”: perception of hazard and health resources in COVID-19 epidemic context among homeless people”. SSM Popul Health. 2021;15:100829. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Howells K, Burrows M, Amp M, et al. Exploring the experiences of changes to support access to primary health care services and the impact on the quality and safety of care for homeless people during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study protocol for a qualitative mixed methods approach. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:29. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01364-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Paula HC, Daher DV, Koopmans FF, et al. No place to shelter: ethnography of the homeless population in the COVID-19 pandemic [article in Portuguese] Rev Bras Enferm. 2020;73(Suppl 2):e20200489. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2020-0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bhattacharya P, Khemka GC, Roy L, et al. Social injustice in the neoliberal pandemic era for homeless persons with mental illness: a qualitative inquiry from India. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:635715. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weaver K, Olson JK. Understanding paradigms used for nursing research. J Adv Nurs. 2006;53:459–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11:589–97. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fox C. CP24 updated 2020 Nov. 20. Toronto and Peel placed under “lockdown,” all non-essential retail will be limited to curbside pickup only. [accessed 2022 Mar. 28]. Available: https://www.cp24.com/news/toronto-and-peel-placed-under-lockdown-all-non-essential-retail-will-be-limited-to-curbside-pickup-only-1.5197335.

- 20.Davidson S. Stay-at-home order extended in Toronto, Peel and North Bay until March 8, restrictions to ease in York. CTV News Toronto. [accessed 2022 Mar. 28]. updated 2021 Feb. 19. Available: https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/stay-at-home-order-extended-in-toronto-peel-and-north-bay-until-march-8-restrictions-to-ease-in-york-1.5315544.

- 21.The Canadian Press. COVID-19: Ontario now under provincewide ‘shutdown’ to control spread of virus. Global News. 2021. Apr 3, [accessed 2022 Mar. 28]. updated 2021 Apr. 4. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/7736868/covid-ontario-provincewide-shutdown/

- 22.City of Toronto. Toronto street needs assessment 2018 results report. Toronto: Canadian Observatory on Homelessness/Homeless Hub; 2018. [accessed 2021 Dec. 19]. Available: www.homelesshub.ca/resource/toronto-street-needs-assessment-2018-results-report. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative methods for health research. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Clarke V, Braun V. Thematic analysis. J Posit Psychol. 2017;12:297–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2021;13:201–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedrosa AL, Bitencourt L, Fróes ACF, et al. Emotional, behavioral, and psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11:566212. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parkes T, Carver H, Masterton W, et al. ‘They already operated like it was a crisis, because it always has been a crisis’: a qualitative exploration of the response of one homeless service in Scotland to the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18:26. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00472-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baral S, Bond A, Boozary A, et al. Seeking shelter: homelessness and COVID-19. Facets. 2021;6:925–58. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, et al. Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2020;89:242–50. doi: 10.1159/000507639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jalili M, Niroomand M, Hadavand F, et al. Burnout among healthcare professionals during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2021;94:1345–52. doi: 10.1007/s00420-021-01695-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khan KS, Mamun MA, Griffiths MD, et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic across different cohorts. Int J Ment Health Addict. 2022;20:380–6. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00367-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheather J, Fidler H. COVID-19 has amplified moral distress in medicine. BMJ. 2021:372. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamiani G, Borghi L, Argentero P. When healthcare professionals cannot do the right thing: a systematic review of moral distress and its correlates. J Health Psychol. 2017;22:51–67. doi: 10.1177/1359105315595120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hines SE, Chin KH, Glick DR, et al. Trends in moral injury, distress, and resilience factors among healthcare workers at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:488. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18020488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, et al. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10:113–24. doi: 10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Couto Zuber M. Nearly 75 per cent of Ontario doctors experienced burnout during pandemic, survey finds. CTV News Toronto. 2021. Aug 18, [accessed 2021 Sept. 20]. Available: https://toronto.ctvnews.ca/nearly-75-per-cent-of-ontario-doctors-experienced-burnout-during-pandemic-survey-finds-1.5552218.

- 41.Etz R, Green LA. Quick COVID-19 primary care survey, Series 29. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Library; Jul 27, 2021. 2021. [accessed 2021 Aug. 23]. Available https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/168418. [Google Scholar]

- 42.City of Toronto COVID-19 response for people experiencing homelessness. Toronto: City of Toronto; 2020. [accessed 2021 Dec. 19]. Available: https://www.toronto.ca/news/city-of-toronto-covid-19-response-for-people-experiencing-homelessness/ [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hwang S. It is possible to end chronic homelessness if we act now. Globe and Mail. 2020. Sept 28, [accessed 2021 Sept. 20]. Available: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-it-is-possible-to-end-chronic-homelessness-if-we-act-now/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.