Abstract

Mental Health Nurse Consultants are advanced practice mental health nurses who consult with nurses and other health professionals in a general hospital setting. The aim of this review was to analyse and synthesize the available evidence related to the impact of Mental Health Nurse Consultants on the care of general hospital patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions. The integrative literature review method was utilized as it allows for the inclusion and integration of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research which produces a synthesized understanding of data to inform practice, policy, and research. The Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Review and Meta‐Analyses guided the search strategy. All published studies examining the impact of clinical consultations provided by Mental Health Nurse Consultants on the mental health care of general hospital patients were included. The 19 selected articles were from North America, Australia, the United Kingdom, and Europe. Fifteen were quantitative, three were qualitative, and one used mixed methods. The findings highlight the role is generally positively received by hospital staff. The results indicate that clinical consultations provided by Mental Health Nurse Consultants (i) may improve patient experiences of mental health conditions, (ii) influence aspects of care delivery, (iii) are valued by staff, particularly nurses, and (iv) increase staff competence and confidence in the provision of mental health care. The review highlighted significant limitations of the available evidence, the need for contemporary discussion and debate of MHNC theory and practice, and further evaluation of the role to inform future service delivery.

Keywords: general hospitals, Mental Health Nurse Consultant, mental illness, multimorbidity, Psychiatric‐Mental Health Nursing

INTRODUCTION

A developing challenge for health systems across the world is the increasing proportion of adults experiencing multiple coexisting health conditions and the common co‐occurrence of physical and mental health conditions (AIHW 2021). For example, anxiety disorder is frequently diagnosed in long‐term physical conditions, such as epilepsy (50%) and cardiovascular disease (30%) (Latas et al. 2019). There is strong evidence that people experiencing enduring mental health conditions are at considerable risk of developing more than one long‐term physical health condition (Rodrigues et al. 2021), have significantly higher rates of general hospital (GH) admission (Fok et al. 2019; Jayatilleke et al. 2018), and have poorer physical health outcomes (Lawrence et al. 2013).

The implication of these figures is that at any time, a significant proportion of the GH patient population will experience co‐occurring mental health conditions. Accurate data on the prevalence of mental health conditions in GH patients are difficult to ascertain given the multitude of conditions that could be examined, the various diagnostic methods and nomenclature utilized (Ranjith 2012), and the patient group or sub‐group studied. With these limitations in mind, the prevalence of mental health conditions in GH patients has been estimated between 15 and 50% (Wolff et al. 2018).

The available literature indicates that depressive symptoms, depressive and anxiety disorders, and stress‐related disorders are the most common mental health conditions experienced by GH patients (Groves & Muskin 2018; Huang et al. 2019; Latas et al. 2019; Yanzón de la Torre et al. 2016). Older GH patients are more likely to experience dementia (41%) or delirium (27%) with 19% experiencing both (Whittamore et al. 2014). Sixteen per cent of people admitted to a large GH were found to screen positive for significant substance use (Wakeman et al. 2020). People who experience enduring mental health problems such as schizophrenia, and schizoaffective, bipolar (Jayatilleke et al. 2018), and personality disorder (Fok et al. 2019) are over‐represented in GH admissions.

Mental health conditions in GH patients are associated with increased mortality (Karim et al. 2019) and added distress for patients and relatives (Clissett et al. 2013). The additional complexity of care results in increased resource usage (Jansen et al. 2018; Wolff et al. 2018) and unique pressures on staff (Foye et al. 2020). It has been found repeatedly that nurses not specifically educated in mental health care struggle to identify the mental health needs of patients and when they do, lack the confidence and expertise to intervene (Alexander et al. 2016; Bird 2018; Brunero et al. 2018; Weare et al. 2019).

Mental health support in general hospitals

For nearly a century, psychiatrists have assisted medical colleagues in the care of GH patients experiencing co‐occurring mental health conditions through a Mental Health Consultation‐Liaison Service (MHCLS) (Aitken et al. 2016). It has been demonstrated that these services can have a positive impact on patient outcomes, length of stay, resource usage, and readmissions (Oldham et al. 2019; Stein et al. 2020; Toynbee et al. 2021; Wood & Wand 2014).

During the early 1960s, American nurse leaders began voicing their concerns about deficits in mental health care in GHs (Robinson 1982). Like their medical colleagues, mental health nurses recognized that their specialized skills could be of assistance to GH colleagues through consultancy and education. The Mental Health Nurse Consultant (MHNC) role was subsequently developed (Robinson 1982). The international development of the MHNC was informed by this pioneering work with seminal publications in Canada (Moreau et al.,1974), Australia (Meredith & Weatherhead 1980), the United Kingdom (Jones 1989), New Zealand (Chiplin & Geraghty 1990), Greece (Priami & Plati 1997), Taiwan (Chui 1999), and the Netherlands (Latour, 2001).

A MHNC is an advanced practice mental health nurse who consults with nurses and other health professionals in a GH setting. The MHNC supports staff to provide mental health care to patients admitted for a physical condition through clinical consultation (assessment, interventions, monitoring, and discharge planning) to patients and/or their relatives (family and significant others). Clinical consultation includes two‐way communication between the MHNC and staff which creates an opportunity for provision of staff support, guidance, and informal education. It also facilitates the collaborative development of a care plan that is adjusted as required. Formal education may also be provided to support patient care. In addition, MHNCs can provide organizational consultation to the GH on mental‐health‐related projects, and policy development (Sharrock et al. 2006). Some positions work alongside their psychiatrist and allied health colleagues in a MHCLS and some work independently from other mental health clinicians (Sharrock et al. 2008).

A preliminary review of the literature yielded limited publications on MHNC theory and practice in the last decade, or research on the impact of MHNC on the care of GH patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions, since the role was introduced. The first mention of potential impact was a review of referral patterns to psychiatrists in a GH in the United States (Lipowski & Wolston 1981). A MHNC was added to the medical MHCLS during the study period. It was noted that from that time there were less requests for transfer from medical–surgical units to psychiatry units. The authors postulated that this was a result of the MHNC working with staff, particularly nurses, supporting them to care for patients experiencing co‐occurring mental health conditions (Lipowski & Wolston 1981). They also noticed that the MHNC identified patients in need of mental health support earlier in their stays, liaised with staff, and engaged patients that might not otherwise engage with a psychiatrist only team.

Anecdotally, MHNC positions have increased across Australia since the 1980s (Sharrock et al. 2008). While this growth suggests their services are valued, the specific contribution they make has not been clearly established. Opportunities for ongoing growth in the MHNC role is likely, particularly in Victoria, Australia, where the recent Royal Commission into the state’s mental health system has recognized that GH patients should be provided with “high‐quality integrated mental health treatment, care and support” during their hospitalization (State of Victoria 2021, p.582). A position that is reinforced by the expectation of the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC 2019) that general health care providers meet the comprehensive care needs of patients, inclusive of mental health.

In this contemporary context, it is important to have a clear understanding of MHNC practice and its links to outcomes if informed decisions are to be made about the optimal mix of mental health professionals to provide consultation to GHs to support the integration of quality mental health care to patients in GHs.

Aim

The aim of this review is to analyse and synthesize the available evidence related to the impact of MHNCs on the care of GH patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions.

METHODS

An integrative literature review (Whittemore & Knafl 2005) was chosen as it allows for the inclusion and integration of quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods research which results in a synthesized understanding of the topic under investigation that informs practice, policy, and research. In keeping with this method, the steps for conducting an integrative review were followed (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Steps of an integrative review

| Step 1 |

Problem identification Background reading and knowledge of the subject Application of the SPICE framework |

| Step 2 |

Literature review Search strategy: search terms, inclusion criteria Application of PRISMA to the systematic dentification and screening of studies via databases and other methods |

| Step 3 |

Data evaluation Application of the MMAT |

| Step 4 |

Data analysis and synthesis Data reduction and display in an electronic spreadsheet Data comparison, drawing conclusions, and verification |

| Step 5 | Presentation of the integrative review |

Problem identification

The first step in an integrative review is to clearly identify the problem and the “variables of interest” (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). The problem has been described in the introductory paragraphs of this paper but to refine this further, the SPICE (setting, perspective, intervention, comparison, evaluation) framework (Booth 2006) was applied (see Table 2). The problem is that the existing evidence related to the impact of MHNC services on the care of GH patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions has not been systematically searched, analysed, and integrated into a summary that informs the ongoing development of and research into MHNC as a specialist area of mental health nursing.

Table 2.

Application of the SPICE framework

|

Setting MHNC service that supports staff to provide mental health care to patients admitted to a GH. A GH provides medical/surgical services to patients admitted primarily for a physical condition. The MHNC service may be nurse‐led or imbedded in a MHCLS. |

|

Perspective Key stakeholders: Those who use the service: referred patients and/or their relatives and consultees who request consultation. Those who have an interest in the service: nursing, medical and allied health staff groups, clinical and general managers, MHCLS clinicians, MHNCs, and mental health services. |

|

Intervention MHNC service that provides clinical consultation includes direct care to patients and/or their significant others (assessment, interventions, monitoring, and discharge planning) and may include indirect care via staff support and guidance, collaborative care planning or education (Sharrock et al. 2006). |

|

Comparison Data collected before and after clinical consultation, after a clinical consultation, before and after initiation of MHNC service, or cross‐sectionally after initiation of MHNC service. |

|

Evaluation To determine if there was some form of impact on care of GH patients with concurrent mental health conditions. |

Therefore, the primary question that this review addresses is: ‘What impact do MHNCs have on the care of GH patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions?’ This question will be examined through primary research or quality improvement projects from the perspectives of key stakeholders (referred patients and/or their relatives and consultees who request consultation, nursing, medical and allied health staff groups, clinical and general managers, mental health services, MHCLS clinicians, and MHNCs).

Literature search

The second step in an integrative literature review is the literature search, starting with the development of the search strategy. The search terms were determined from knowledge of the subject, further background reading, and using keywords listed in relevant articles. The title used to describe the MHNC role varies across the world and terminology has changed over time, so to capture this, multiple combinations of terms and their synonyms were required. The search strategy used “*” to capture variations of root words and “n” (CINAHL) or “adj” (MEDLINE AND PsycINFO) to search for words in proximity to each other. An example of a search strategy is provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

An example of the search terms in the CINAHL database

|

"mental health" n3 nurs* n3 specialist* OR psychiatr* n3 nurs* n3 specialist* OR "mental health" n3 nurs* n3 consulta* OR psychiatr* n3 nurs* n3 consulta* OR "mental health" n3 nurs* n3 liaison OR psychiatr* n3 nurs* n3 liaison OR "mental health" n4 advanced n4 practice n4 nurs*" OR psychiatr* n4 advanced n4 practice n4 nurs* OR psychiatr* n3 “nurse practitioner*” OR "mental health" n3 “nurse practitioner*” OR “consultation liaison*” OR "mental health” n2 liaison OR psychiatr* n2 liaison |

| AND |

| satisfaction OR outcome* OR effective* OR improv* OR evidence OR quality OR cost* OR resource* OR evaluat* OR impact OR “length of stay” OR “constant observ*” OR special* OR sitter* OR “one to one” |

A search of three electronic databases (CINAHL, Medline, and PsycINFO) and a hand search of ProQuest Dissertations and OpenDissertations was conducted in August 2021. To identify any additional articles, the reference lists of each full‐text article and citations for each of the selected articles were checked.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Given a preliminary literature review uncovered limited research, an open‐ended date range was used. Journal articles, theses, and dissertations that reported in English on original research or quality improvement projects were included. Selected articles examined the impact of MHNC services within GHs on the care of patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions. Articles were included if they described a MHNC that provided clinical consultation inclusive of direct patient care (assessment, interventions, monitoring, and discharge planning) as described in Table 2. Articles that reported on organizational consultations or outcomes associated with a MHCLS without identifying any nursing specific findings were excluded. MHNC services exclusively provided to emergency departments, outpatient or primary care settings, and nursing homes were also excluded.

Screening process

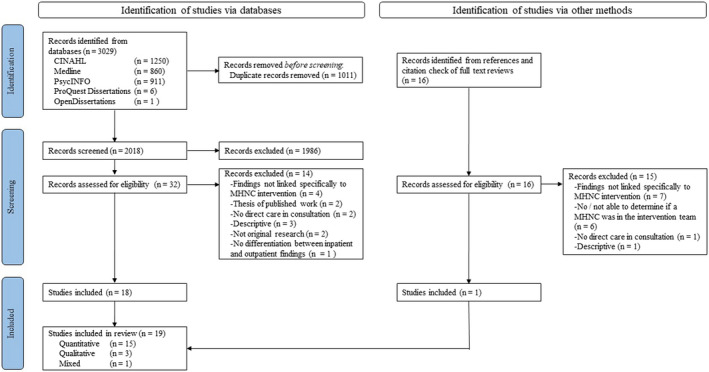

A systematic approach was applied to the literature search by following the stages set out in PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Review and Meta‐Analyses) (Page et al. 2021). This is summarized in Figure 1. After removing duplicates, the title of each remaining article was reviewed and those without relevance to the topic were removed. The abstracts of the remaining articles were then reviewed and those without relevance to the topic were removed. After these steps were completed, there were 48 articles for full‐text review. Twenty nine of these articles were excluded. For more information, see Figure 1. Nineteen articles were selected from the full‐text review and are summarized in Table 4.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow chart of search and screening process (Page et al. 2021).

Table 4.

Summary of included studies

|

Author/s (Year) Country |

Aim |

Design Measures Participants |

Setting Consultation trigger Model |

Key findings | Limitations | MMAT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Afriyie‐Boateng et al. (2019) Canada |

Determine the impact of a nurse led Behavioural Optimization and Outcomes Support Team on staff with a focus on their perceptions of support and safety at work and burden of care of patients with behavioural disturbance |

Quantitative cross‐sectional descriptive (QI) Survey of staff perceptions of safety at work and the service elements that contribute to this Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile sub‐scale ‐ perceived burden of care of patients with behavioural disturbance n = 64 56 nurses and 8 social workers Response rate 78% |

Teaching GH medical–surgical units 2 MHNC (new) Augmented a MHCLS Patients all ages Proactive screening Requests from any staff member due to behavioural disturbance Consultation included collaborative care planning, formal/informal education, and debriefing |

Improved access to resources and ability to manage challenging behaviours Increased sense of safety at work (p = 0.05) Reduced perception of burden of challenging patient behaviour while perception of frequency remained the same Valued interventions: ‐individual/standardized care plans ‐support/availability ‐proactive consultation ‐debriefs after critical incidents |

Methods and findings lacked detail Survey instrument not well described Unclear how the participants were selected Violent incidents not analysed (part of the intervention was to lower the threshold for calling codes) but could have measured interventions used in the code from verbal de‐escalation to use of restraint |

* |

|

Baldwin et al. (2004) United Kingdom |

Determine the effectiveness of a Mental Health Liaison Nurse on symptoms of depression and cognitive impairment in older patients |

Quantitative RCT Screening: 4‐item GDS; Orientation Memory Concentration test Outcome: 12‐item HoNOS 65+; GDS 30; Standardized Mini‐Mental State Examination n = 153/120 77 intervention and 59 at follow‐up 76 control and 61 at follow‐up |

4 acute medical units of a district GH 1 MHNC Access to psychiatrists and a community mental health team Patients ≥ 65 Positive screen for depressive symptoms and/or cognitive impairment and randomized to intervention Consultation included encouraging person‐centred care, education and linking with resources |

6‐ to 8‐week follow‐up: ‐significantly lower GDS scores in the intervention group ‐no significant difference in overall HONOS 65+ score or in 10/12 items (behaviour, self‐injury, substance use, cognition, illness or disability, hallucinations and delusions, activities of daily living, occupation and activities, and other symptoms not specified) ‐no difference in cognitive improvement ‐no significant differences on LoS (inadequately statistical powered), re‐hospitalization, or death Increased psychiatrist referrals |

Recruitment not high but adequate given age and illness Crossover affect could not be eliminated Control group had access to a psychiatric treatment Cognitive status at discharge is not a sensitive outcome measure |

***** |

|

Brinkman (2006) Canada |

Examine how the Mental Health Liaison Nurse contributes to increased awareness within nurses of holistic nursing care delivery |

Qualitative descriptive Semi‐structured individual or group interviews n = 14 Nurses from a range of specialities |

Small rural GH with 26 inpatient beds plus emergency and community functions 1 MHNC (new) Unclear if access to MHCLS Patients all ages Requests from any staff member Consultation included collaborative care planning and formal/informal education |

MHNC was available and visible, improved access to a specialist in mental health resource, reduced stigma as mental health was being incorporated into care Built capacity through: ‐care planning and treatment contracts ‐education, coaching and role‐modelling ‐troubleshooting difficult situations |

MHNC was the interviewer and data analyst Rigour not discussed Specific feedback about the role imbedded in an experiential learning activity MHNC providing service for wards, with emergency department and community functions |

***** |

|

Brinkman et al. (2009) Canada |

Evaluate a Mental Health Liaison Nurse service in relation to access, continuity of care, quality of care, and provision of education |

Quantitative descriptive Cross‐sectional 10‐item survey on a 5‐point Likert scale with space for narrative responses n = 58 Profession not stated Response rate 50% (75% of possible medical staff) |

As above | 94.5% and above agreement on all 10 satisfaction items focussed on access to service, continuity of care, quality of care, and provision of education |

Methods and findings lacked detail MHNC providing service for wards, with emergency department and community functions |

** |

|

Cullum et al. (2007) United Kingdom |

Determine the effectiveness of Liaison Psychiatric Nurse on depressive symptoms or disorder in older patients |

Quantitative RCT Screening: 15‐item GDS Outcomes: 15‐item GDS, Geriatric Mental State (depressive disorder), EuroQol, Abbreviated Mental Test Score, Cumulative Illness Rating Scale‐Geriatric, Activities of Daily Living Score; 4‐point Likert patient satisfaction scale n = 121/84 62 intervention and 41 follow‐up 59 control and 43 at follow‐up |

Acute medical wards of a district GH 1 MHNC Unclear access to MHCLS Patients ≥ 65 Positive screen for depression and randomized to intervention Consultation included care planning but unclear about collaboration; did not educate staff to avoid contamination of control |

No significant changes in measures at 16‐week follow‐up there but there was a trend towards improvement depressive symptoms/disorder and QoL Death in intervention group twice that of the control group 93% of responses scored on the top two positive anchor points for service satisfaction |

Base‐line groups different Small sample size, high dropout/death rate Control group had access to a treatment of depression |

***** |

|

de Jonge et al. (2003) Netherlands |

Investigate the effect of Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse on LoS and QoL for medical patients |

Quantitative non‐RCT Stepped detection and treatment strategy with historic control group Screening: COMPRI; INTERMED Outcomes: SF‐36, LoS n = 193/143 100 intervention and 81 at discharge 93 historic control and 62 at discharge |

Metropolitan teaching GH medicine, nephrology, and gastroenterology units 1 MHNC part of established MHCLS service Patients adult and >65 Positive screen for increased risk of extended LoS or poor health status at discharge Consultation that may include interdisciplinary discussion or referral to a psychiatrist |

Reduced LoS in intervention group who were over >65 and small improvement in QoL for the whole intervention group but did not hold after controlling for confounders No difference in death rates Referrals to MHCLS doubled during intervention period |

Non‐randomized using an historic control with differences in groups i.e. slightly older in intervention group Historic control and intervention group had access to MHCLS intervention |

***** |

|

Happell and Sharrock (2002) Australia |

Determine the impact of the Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse on patient outcomes as perceived by staff |

Qualitative descriptive 3 semi‐structured focus groups n = 17 16 nurses; 1 social worker |

830‐bed metropolitan teaching GH 1 MHNC (new) Added to a MHCLS Patients adult and ≥ 65 Requests from any staff but primarily nurses Consultation included collaborative care planning and formal/informal education |

Overwhelmingly positive responses Themes of “Making Contact”, “Helping Staff”, “Implementing Strategies” and “Utilizing Attributes” |

In/exclusion criteria, recruitment, and consent process not clear | ***** |

|

Heyman and Lombardo (1995) United States |

Present the outcomes from a Clinical Nurse Specialist program for confused, agitated or suicidal patients and hospital‐paid companion use |

Quantitative descriptive (QI) Paid companion data; LoS; falls, deaths |

Large teaching GH 2 MHNC In addition to a MHCLS Patients age not reported Request for companions due to behaviour Consultation included care planning, decision about companions, and referrals to MHCLS where necessary, education imbedded into project |

Reduction in paid companions: 482 to 101 patients requiring companions in first year, cost saving US$81,254, then maintained at a mean of 4475 hours per annum Average LoS for 28 suicidal patients in the first year 1.2 days below standard allowance No patient falls or suicides associated with the project |

Methods and findings lacked detail Could have measured restraint use |

** |

|

Kurlowicz (2001) United States |

Describe the characteristics, changes in psychiatric symptoms, and discharge disposition of older patients and satisfaction of staff following Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse consultation |

Quantitative descriptive 12‐month retrospective cohort (QI) Outcomes: 30‐item GDS; Confusion Assessment Method n = 103 patients 31 depression baseline and 21 at discharge 34 delirium baseline and at discharge 2‐item consultee satisfaction survey (Was the consultation helpful? If yes, describe how were you “most” helped by the consultation) n = 83 nurse consultees Response rate 80% |

Urban teaching GH (8 surgical and 7 medical units) 1 MHNC In addition to MHCLS Patients ≥60 Requests primarily from nurses but also medical staff Consultation included working with the staff, care planning, and implementation of protocol for delirium; may include recommendation for referral to MHCLS |

Significant decrease in mean GDS for patients with depression Discharge disposition improved in 12% screen positive patients No patients had delirium at discharge 100% said the consult was helpful |

Survey not validated Patients had access to psychiatric treatment of depression with medication prescription not reported Cognitive status at discharge is not a sensitive outcome measure |

***** |

|

Lakatos (2009) United States |

Examine how do nurses perceive their comfort and competence in providing psychologically based nursing care and what knowledge they have of delirium following implementation of the Psychiatric Nursing Resource Service |

Quantitative descriptive (QI) 19‐item comfort and competence 4‐point Likert 10‐item knowledge of delirium multiple‐choice Security calls; sitter rates n = 132 Pre 81; post 51 Post‐response rate 20.4% |

155 beds across 2 medical and 3 surgical units in a large tertiary academic GH 1.3 MHNC (new) Unclear access to MHCLS Patients age not reported Requests from nurses Consultation included care planning, coaching, and education |

Increased comfort and competence Delirium knowledge: 6/10 questions answered correctly 70% 57% reduction in security calls in 1st year, 10% increase in 2nd (increased no of brain injured patients) Overall reduction in sitters; for delirium from an average of 9.74 to 8.07 (full time equivalent) per annum |

Possibility of selection bias‐convenience sample and poor response rate Instruments not validated Self‐assessment, not matched Restraint not measured in second phase |

*** |

|

Mallory et al. (1993) United States |

Undertake an in‐depth analysis of hospital data on patients receiving varying intensity of MHCLS and nursing resource usage |

Quantitative descriptive Retrospective audit 2 years of referrals grouped into low‐, medium‐, and high‐intensity MHCLS users MHCLS intensity data; fiscal data; case‐mix; clinical files n = 150 |

Large metropolitan teaching GH MHNC numbers not provided Part of MHCLS Patients mean age 48 MHCLS referrals (n = 1734) Consultation may include staff/patient conference, consultee supervision, or liaison activity (not defined) |

Low‐intensity group primarily seen by the MHNC only show no significant impact on resource usage |

Reduction in nursing resource usage by medium intensity patients but no isolation of MHNC‐specific interventions Nursing care hours increase in the high‐intensity group may not be a negative outcome i.e. it may be that they are getting the care they need that was previously neglected |

***** |

|

Newton and Wilson (1990) Canada |

Elicit consultee perceptions of Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse contribution to the care of medical patients |

Quantitative descriptive (QI) Prospective 12‐item consultee satisfaction survey on a 4‐point Likert scale at the end of the consultation (or study) n = 69 Response rate 92% of 75 consultations |

Major teaching tertiary care GH of 1100 beds 1.5 MHNC Collaborates with MHCLS Patients all ages including infants Requests from nurses Consultation included care planning and may recommend referral to others |

100% overall satisfaction with consultation and likelihood of making another referral 98.5% High satisfaction with access, documentation, communication, recommendations, Lowest rating was sufficient follow‐up 88.1% |

Instrument not validated | **** |

|

Priami and Plati (1997) Greece |

Investigate the effectiveness of Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse consultation on patient symptoms and satisfaction with service |

Quantitative descriptive Nurses’ Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation 3‐item patient satisfaction interview guide on a 5‐point Likert scale n = 95 |

Medical–surgical patients in a general district GH 1 MHNC Part of MHCLS Patients “of age” Referrals to MHCLS Consultation with no staff interventions described |

Improvements on most symptoms which included: mood, emotional state, thought content and form, perception, and behaviour Agreement from patients that the MHNC interventions improved their health outcomes |

Only 21% met the selection criteria and unclear why Instrument not valid for general hospital patients and was modified Findings not well explained Statistical analysis not clear Consumer feedback lacks detail as to what was and was not helpful |

*** |

|

Rausch and Bjorklund (2010) United States |

Evaluate the impact of Psychiatric Liaison Nurse on constant observation of medical patients |

Quantitative descriptive (QI) Constant observer and restraint use, and patient falls pre‐ and post‐intervention n = 175 |

800‐bed urban tertiary GH 1 MHNC (new) MHNC for physician referrals Patients adolescent, adult and ≥ 65 Requests for constant observation due to at‐risk behaviour CC included collaborative care planning and formal/informal education |

50% reduction in constant observation costs without associated increase in falls or restraint use | Could have measured LoS | ***** |

|

Roberts (1998) United Kingdom |

Determine how the Liaison Mental Health Nurse was perceived by the nursing team and examine the implications of this for the role |

Qualitative descriptive Focus group n = 3 Nurses |

Haematology unit of a large tertiary teaching GH 1 MHNC Part of MHCLS Patients age not reported Requests from treating team Consultation included collaborative care planning and formal/informal education |

Role was valued ‐ availability, visibility, objectivity, and provision of staff support; provide counselling support to patients; clarify normal reactions from illness Complemented the psychosocial care the unit nurses provided |

Methods and findings poorly described Interviewer was the MHNC 3 participants so the findings do not represent the views of the ward team Brief article in non‐peer reviewed nursing magazine |

* |

|

Sharrock and Happell (2001) Australia |

Evaluate the Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse role added to an established MHCLS |

Quantitative descriptive 11‐item Health Professionals Perception Survey (designed and prescribed by the project) n = 113 82% had made a referral 94 nurses, 11 medical, 8 allied health Response rate 43.5% |

Companion paper to Happell and Sharrock (2002) | Strong positive responses to the 7 satisfaction items |

Survey prescribed by broader project; not validated Aim and in/exclusion criteria not clearly stated Short answer response analysis not clear Rigour not discussed No nursing implications for future education, practice, and research |

** |

|

Sharrock et al. (2006) Australia |

Evaluate the effectiveness of a Psychiatric Consultation‐Liaison Nurse as perceived by health professionals and its impact on nursing attitudes |

Mixed methods Health Professionals Survey (general nurses’ attitudes to caring for people with a mental illness) 3 semi‐structured focus groups n = 322 Pre 180/post 142 Response rate 52% and 37% n = 25 (focus groups) 13 nurses, 7 allied health, 5 medical |

Major metropolitan teaching GH with 46,000 annual admissions 1 MHNC (new) Added to a MHCLS Patients adult and ≥ 65 Requests from any staff but primarily nurses Consultation included collaborative care planning and formal/informal education |

Positive responses from focus groups Themes ‐improved the access ‐translating mental health concepts for nursing staff ‐care planning ‐providing practical assistance in the mental health care of patients ‐supporting nursing staff ‐an approachable “sounding board” ‐skill development and education Attitudes were found to be negative overall and no attitudinal change noted |

Process for quantitative approach poorly described In/exclusion criteria not clear Attitudinal surveys: modified survey, unclear if validated, pre‐ and post‐responses not matched No examples of negative attitudes given or discussion of the lack of change in attitudes Potentially could have done correlation analysis Rigour not discussed |

*** |

|

Stiefel et al. (2008) Switzerland |

Determine the impact of Psychiatric Liaison Nurse interventions on the health outcomes of complex medically ill patients |

Quantitative RCT Screening: INTERMED Outcomes: MINI (depression section), CES‐D, SF‐36, and EuroQol at assessment and 3‐, 6‐, 9‐, and 12‐month intervals n = 247 125 intervention and 76 at final follow‐up at 12 months 122 control and 83 at final follow‐up at 12 months |

Rheumatology inpatients and endocrinology outpatients at a university GH 2 MHNCs Part of a MHCLS Patients age not reported Positive screen for increased risk of extended LoS or poor health status at discharge and randomized to intervention Consultation may include multidisciplinary conference or include referral to a psychiatrist |

Improvement in depressive symptoms in rheumatology inpatients CES‐D [effect size: 1.7 (s.e. = 1.1); p = 0.14] i.e. severity of depressive Sx No other findings were isolated for the inpatient intervention group |

Findings from inpatient and outpatient intervention not isolated apart from a reduction in severity of depressive symptoms Usual care could include referral to a psychiatrist Antidepressant prescription may have increased as referral to psychiatrists increased but this was not recorded Low response rate risk of non‐response bias |

***** |

|

Talley et al. (1990) United States |

Evaluate the impact of Psychiatric Liaison Nurse interventions on suicidal and non‐suicidal patients requiring sitters |

Quantitative RCT Number of sitter shifts; nursing note observations of mood, behaviour, and mental status; patient and sitter incidents, walkoffs and refusals LoS n = 107 49 non‐suicidal control and 36 intervention 11 suicidal control and 11 intervention |

Large urban GH 2 MHNCs Access to psychiatrists Patients adult and ≥ 65 Allocated a sitter Consultation included collaborative care planning and education |

No reduction in sitter shifts, patient or sitter incidents or LoS No increase in charted nursing observations of mood, behaviour, and mental status |

Process for randomization not described Groups appear different at baseline No information if data collectors were blinded Number of patient and sitter incidents too small for analysis Systemic issues that were out of MHNC control that impacted on outcomes |

** |

Abbreviations: COMPRI, Complexity Prediction Instrument; EuroQol, European Quality of Life; GDS, Geriatric Depression Scale; HoNOS 65+, Health of the Nation Outcome Scale 65+; INTERMED, Interdisciplinary Medicine; LoS, Length of Stay; MHCLS, Mental Health Consultation‐Liaison Service; MINI, Mini‐International Neuropsychiatric Interview; QI, Quality Improvement project; QoL, Quality of Life; RCT, randomized controlled trial; SF‐36, Short Form survey.

Data evaluation

The third step in an integrative review is to evaluate the selected articles. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was chosen as it can be used for quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods research (Hong et al. 2018). The tool has two optional screening questions that ascertain if the study has clear research questions and if data collected allow for the research questions to be addressed. Not all articles framed their research focus as a question, but they did have a clear aim so were included in the MMAT evaluation.

The selected studies were allocated to a study type category. Each category has five questions where one can answer “yes”, “no”, or “can’t tell”. Scoring is discouraged by the MMAT authors (Hong et al. 2018). Instead, the overall quality for each study is presented in Table 4 using asterisks, ranging from * when one question has an affirmative response up to ***** when all questions have an affirmative response. The authors also advise against excluding studies based on low quality (Hong et al. 2018). To reduce the risk of bias, the first author reviewed all the papers, the second author reviewed papers excluding those she co‐authored, and the third author reviewed those written by the first two authors. The authors compared their evaluations and discrepancies were discussed to reach consensus.

Data analysis and synthesis

Data analysis is the fourth step of an integrative review (Whittemore & Knafl 2005). Each article was examined and compared, similarities and differences were noted, and they were organized for data extraction. Whittemore and Knafl (2005) acknowledge that one of the aspects of integrative review that is least developed is data analysis. Given this, “data‐based convergent synthesis” (Hong et al. 2017, p.7) was applied to integrate qualitative and quantitative data. In keeping with this approach, quantitative and qualitative evidence was analysed in a parallel manner during the same phase of analysis. To be able to compare quantitative and qualitative data, quantitative data were transformed into qualitative descriptive data.

Data were reduced, organized, and displayed in a spreadsheet which allowed for themes, patterns, and relationships within the data to emerge. The process of comparing data and moving iteratively between data and the emerging synthesis provided the opportunity to verify that conclusions being drawn from the data were a plausible interpretation of the evidence.

Data analysis was undertaken by the primary author and reviewed by the other authors. Interpretations and conclusions were discussed, and any discrepancies were reconsidered until agreed upon. This process led to the development of an integrated synthesis of the phenomenon under review. This is the final step of an integrative review and is presented as a descriptive narrative in the following section.

RESULTS

Study characteristics

Articles were from the United States (n = 6), Canada (n = 4), Australia (n = 3), the United Kingdom (n = 3), Switzerland (n = 1), Greece (n = 1), and the Netherlands (n = 1). Twelve studies were undertaken between 2001 and 2010, six between 1990 and 1998, and one in 2019. Fifteen of the selected articles were quantitative, three were qualitative, and one used mixed methods.

Studies reported on the impact of MHNC services on a range of outcomes and an overview is provided in Table 5. These include patient experiences of mental health conditions (n = 7), patient perceptions of care (n = 2), aspects of care delivery (n = 12), consultee perceptions of consultations (n = 5), staff perceptions of MHNC services (n = 8), and staff competence and/or confidence in providing mental health care (n = 10).

Table 5.

Overview of reported outcomes

| Symptoms | QoL | Service satisfaction | Survival | Access to specialists | LoS | Readmission | Discharge destination | Constant observation | Restraint | Calls to security | Falls | Nursing care | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baldwin et al. (2004) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Brinkman et al. (2009) | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Cullum et al. (2007) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| de Jonge et al. (2003) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Heyman | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kurlowicz (2001) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Lakatos (2009) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Quality | |||||||||

| Mallory et al. (1993) | ✓ | Intensity | |||||||||||

| Priami and Plati (1997) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Rausch and Bjorklund (2010) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Sharrock and Happell (2001) | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Sharrock et al. (2006) | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Stiefel et al. (2008) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Talley et al. (1990) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Quality |

| Access | Consultee satisfaction | Staff perceptions | Patient outcomes | Care plan | Regular contact | Support/education | Attributes/expertise | Criticisms/cautions | Knowledge | Attitude | Anxiety | Reflective practice | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afriyie‐Boateng et al. (2019) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Brinkman (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Brinkman et al. (2009) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Happell and Sharrock (2002) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Heyman and Lombardo (1995) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Kurlowicz (2001) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Lakatos (2009) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Newton and Wilson (1990) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Roberts (1998) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Sharrock and Happell (2001) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Sharrock et al. (2006) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Abbreviations: LoS, Length of Stay; QoL, Quality of Life.

MHNC model of service delivery

Position titles varied which reflected international differences and changes over time. The amount of detail provided about the model of service delivery also varied, but enough information was available to determine that the MHNCs provided clinical consultations for patients and/or their relatives that consisted of specialized assessment, interventions, monitoring, and discharge planning. However, not all articles provided a description of interventions undertaken with staff during clinical consultations. It remains unclear if this was not part of their model of intervention or if it was simply absent from the article. Given most articles (n = 16) referenced mental health nursing consultation theory which includes interventions with staff (support, guidance, collaborative care planning, informal and formal education, and ongoing monitoring of the care plan), then it is likely that these were included in their model of service delivery. Further detail of these characteristics is available in Table 4.

Service users

Patients and relatives

MHNC services were provided to all age groups including infants where the primary service recipients were parents. Four studies (Lakatos 2009; Newton & Wilson 1990; Priami & Plati 1997; Sharrock et al. 2006) provided an overview of the mental health conditions experienced by patients at the centre of the requests for consultation. Behaviour that challenged the ability of GH staff to provide safe and effective care that was possibly indicative of an underlying mental health condition was a common precipitant of requests for a MHNC consultation (Lakatos 2009; Newton & Wilson 1990; Priami & Plati 1997; Sharrock et al. 2006). This was particularly prominent where behavioural disturbance was articulated in the model of service delivery as the primary trigger for referral (Afriyie‐Boateng et al. 2019; Heyman & Lombardo 1995; Rausch & Bjorklund 2010; Talley et al. 1990). Behaviours described in these studies included aggression, risk of self‐harm, wandering, elopement, and difficulty collaborating in care. It is recognized that the behavioural descriptors applied by the authors of these studies are limited as they do not capture the experiences or perspectives of patients. The one study in this group (Priami & Plati 1997) that explored the patient perspective did not include their perception of their behaviour. While it is acknowledged that these are clinician focused terms, given their common usage in this literature, alternative words may not be clearly understood.

The most frequent diagnostic groupings were organic mental illnesses (particularly delirium) and issues related to adjustment or coping with illness (patients and/or relatives), followed by mood disorders (particularly depression or depressive symptoms), anxiety, psychotic symptoms or disorder, and issues related to substance use.

Staff participants

A total of 438 staff participated in surveys with an overall response rate of 60.8%. Most participants were nurses (n = 353) followed by allied health (n = 14), medical (n = 9), and MHCLS medical (n = 4) staff. The professional group of 58 survey respondents (Brinkman et al. 2009) was not specified but 75% of possible medical staff responded. A total of 59 staff participated in interviews with nurses (n = 46) making up the bulk of the participants. Allied health (n = 8) and MHCLS medical (n = 5) staff also participated in these interviews.

MHNC intervention may improve patient experiences of mental health conditions

Seven articles reported on the impact of MHNC intervention on patient outcomes through quantitative methods: randomized controlled (RCT) (n = 3), descriptive (n = 3), and non‐randomized (n = 1).

The evidence that the MHNC may influence improvements in patient symptoms was seen on depressive symptoms in older inpatients. Baldwin et al. (2004) measured global symptoms of mental health conditions using the validated Health of the Nation Outcome Scale 65+. The only items that demonstrated improvement were depressive symptoms and relationships. Another RCT using the validated Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) reported a “trend toward improvement” in their intervention group of older medical inpatients (Cullum et al. 2007). Improvements in patients’ depressive symptoms were found using the Nurses’ Observation Scale for Inpatient Evaluation (Priami & Plati 1997). A study of rheumatology inpatients using the validated Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Rating Scale also demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in symptoms, particularly those with more severe depressive symptoms and less severe pain (Stiefel et al. 2008). However, limitations of these four studies include that; (i) any patient could receive treatment for depression from the treating team though referral to a psychiatrist and/or medication prescription, (ii) the scale was modified and not validated for use in a GH setting (Priami & Plati 1997), and (iii) high drop‐out rate was noted in Cullum et al. (2007).

Two studies (Baldwin et al. 2004; Kurlowicz 2001) found improvement from baseline in cognition of their intervention groups of older patients. While improved cognition is a positive outcome, it is the result of a team effort in addressing the underlying causes of delirium and cannot be linked to the MHNC.

The evidence for improved quality of life (QoL) in patients with MHNC consultation is also noted (Cullum et al. 2007; de Jonge et al. 2003). One intervention group (Cullum et al. 2007) expressed significantly higher (95%) satisfaction with overall inpatient care than the control group (61%). Structured interviews undertaken with 95 patients about the impact that MHNC consultation had on four domains of their well‐being reflected improvement in their symptoms and perceptions of their health (Priami & Plati 1997). Each question had the option of four anchor points and responses predominantly fell within the top two positive anchor points in that MHNC facilitated verbal expression, relieved, and had not worsened their psychological condition. The fourth question asked if MHNC intervention relieved their physical illness and 69.4% of responses were on the top two positive anchor points. This may reflect that improved mental health can lead to more positive perceptions of other areas of life.

Five studies reported on death rates of patients and where deaths occurred, they were not attributed to MHNC intervention but to worsening medical conditions (Cullum et al. 2007; Talley et al. 1990).

This group of studies was limited by methodological weaknesses in that their samples were small and included a cross‐section of the heterogeneous patient group seen by MHNCs. Models of service delivery were not well described and did not report on concurrent treatment from others such as psychiatrists, and what impact this may have had on outcomes.

MHNC intervention influences aspects of care delivery

Access to specialized mental health care for GH patients

Participants observed improved patient access to mental health care after MHNC services were introduced GH (n = 6). Pathways to specialist patient assessment were clearer (Sharrock et al. 2006), much needed support for patients was available (Brinkman et al. 2009), and a previously unmet need was met (Brinkman et al. 2009; Happell & Sharrock 2002; Sharrock & Happell 2001). MHNC interventions aimed at promoting “feelings of control, comfort and safety” were perceived to benefit distressed patients and both patients and their relatives responded positively to a “nursing expert” being involved in care (Heyman & Lombardo 1995, p.118).

MHNCs facilitated involvement of other mental health specialists. In a non‐RCT (de Jonge et al. 2003), social work referrals increased from 6% pre‐intervention to 14% during the intervention and psychiatrist referrals increased from 26% to 64%. In a RCT (Baldwin et al. 2004), referral rates to psychiatrists rose from an average of 11 to 19 per month and with no change in psychotropic prescription rates. de Jonge et al. (2003) reported that 46 of the 64 patients referred to a psychiatrist were prescribed medication, but previous prescription rates had not been collected so comparison was not possible. In terms of post‐discharge mental health services, Kurlowicz (2001) found that 15 of the 55 screen positive patients were referred to home mental health care after discharge.

Length of stay, discharges, and readmission

Studies (n = 5) that reported on patient length of stay (LoS) produced mixed findings. In one intervention group, the patients who were over 65 had a shorter LoS (de Jonge et al. 2003) but there was no reduction in LoS in another older age intervention group (Baldwin et al. 2004). The LoS of 28 out of 135 suicidal patients seen by the MHNC was reduced by 1.2 days below the standard allowance through early consultation and timely discharge (Heyman & Lombardo 1995). It is important to acknowledge that as an outcome measure, LoS is influenced by a range of factors, many of which are out of the control of the MHNC. For this reason, one study did not measure LoS (Afriyie‐Boateng et al. 2019) and another found no significant difference (Talley et al. 1990).

A detailed retrospective examination of the characteristics of 2 years of referrals to a MHCLS consisting of psychiatrists and nurses grouped the referrals into low‐, medium‐, and high‐intensity MHCLS users (Mallory et al. 1993). This study also measured LoS and use of GH nursing resources for each group. The low intensity group was the only group where MHNC findings were isolated. This group was more likely to be seen by the MHNC on a single occasion, referred later in the admission for concerns about coping or behaviour, have no mental illness, and be discharged. There was no demonstrable impact on LoS or nursing resource usage found and the authors postulated that more positive outcomes might have been achieved if the MHNC had been able to intervene earlier in the admissions. Findings for the medium‐ and high‐intensity groups are not included in this review as they were seen by both medical and nursing staff with no differentiation in findings.

The actual discharge destination of eight out of 52 patients seen by a MHNC was improved from initial predictions made by the treating team; that is “discharged to settings for more active treatment with more hopeful or optimistic prognoses or indicating improved function” (Kurlowicz 2001, p.56). No other studies looked at this outcome.

Baldwin et al. 2004 found no significant difference in readmission rates of their intervention group. Stiefal et al. (2008) found readmissions did reduce in their intervention group but did not isolate the inpatient from outpatient intervention findings. No other studies reported on this outcome.

Care of patients considered at risk

Constant observation (CO) is an established intervention used when patients are at risk of falls, self‐harm, or elopement. Referred to as sitters in some literature, it is an intensive and costly intervention with limited evidence about its efficacy, minimal inquiry into the patient experience, and a lack of consensus on how it is provided (Shekelle et al. 2019).

The first study (Talley et al. 1990) to report on the impact that MHNCs might have on the use of CO and care quality for this group of at‐risk patients was undertaken in a large general hospital in the United States with a well‐established MHNC service. There was no evidence to support their hypotheses that MHNC interventions would result in improved care and a reduction in CO. In contrast, two subsequent studies (Heyman & Lombardo 1995; Rausch & Bjorklund 2010) found constant observer use decreased with MHNC input. The difference in the later studies is that the MHNC engaged the organization with the project in addition to the provision of clinical consultations. An organizational approach to support clinical consultations was also taken by a MHNC service in a large tertiary teaching hospital (Lakatos 2009). Constant observer usage was reduced but in addition, there was a significant improvement in the quality of care provided. Delegation of tasks to staff providing CO became more specific and they were expected to be actively engaged in patient care. To reflect the shift in focus from sitting and observing to providing care, the term sitter was changed to “Patient Care Associate”. There was also a reduction in the use of mechanical restraint (measured during the pilot phase only) and calls to security to manage patients. Rausch and Bjorklund (2010) also found that the reduction in CO did not result in an increase in restraint use or falls.

MHNC services are valued by staff

Access to mental health expertise

Staff valued the accessibility of mental health nursing expertise and assistance that was easy to contact and responded in a timely manner (n = 8). Increased referral rates (Afriyie‐Boateng et al. 2019) reinforced the view that the service was well received. The regularity of contact with the MHNC (Happell & Sharrock 2002) and the proactive identification of patients with potential mental health needs (Afriyie‐Boateng et al. 2019) facilitated access to mental health service for patients that might not have had access otherwise.

The availability of the MHNC for “spot dialogue about pressing concerns or questions” (Brinkman 2006) or to act as a “sounding board” (Happell & Sharrock 2002; Sharrock et al. 2006) for staff was appreciated. Staff could clarify with the MHNC if their concerns were warranted, to assist them to understand the needs of the patient, and to determine a referral path if required.

The MHNC facilitated involvement of experts including psychiatrists and social workers (n = 7) and was seen as a conduit to inpatient and community mental health services (Happell & Sharrock 2002).

Access to helpful clinical consultations

Two studies sought feedback from consultees following a total of 152 clinical consultations. All consultees who responded to the surveys were satisfied with the consultation (Newton & Wilson 1990) or found the consultation helpful (Kurlowicz 2001). Newton and Wilson (1990) developed a 12‐item Likert scale, each with four anchor points. The responses were extremely positive with the majority of responses on the top two anchor points and an average of 97.9% for 11 out of 12 questions. The lowest scoring question related to adequacy of follow‐up (88.1% in the top two anchor points). Higher overall satisfaction was linked with increased visits and extended involvement of the MHNC. Lower overall satisfaction was more likely when patients had a primary psychiatric diagnosis. The authors postulated that nurses may have preferred more direct input into patient care or possibly transfer of these patients with a primary psychiatric diagnosis to a mental health facility. Given a strong combined response rate of 85% and the timely connection between the feedback and the intervention, these two studies provide valuable feedback on consultee satisfaction with the MHNC consultation.

Eight studies explored the perceptions of past MHNC consultations without linkage in a timely way to a specific consultation. The facilitators of focus groups (Happell & Sharrock 2002) opened semi‐structured interviews with an invitation to participants to provide a description of when they requested consultation with the MHNC, the nature of the issues that prompted the request, the response of the MHNC and how the interventions impacted on their confidence and patient care. This study found an “overwhelmingly positive” response to the clinical consultations provided by the MHNC from the 16 nurses and one social worker who participated. Thematic analysis grouped their responses into: Making Contact, Helping Staff, Implementing Strategies, and Utilizing Attributes which reflect the accessibility and helpfulness of the MHNC.

The last theme refers to the professional use of self in the consultancy work undertaken by the MHNC and was linked with positive perceptions of the role. Being knowledgeable but non‐threatening, supportive, present, and visible meant that staff, particularly nurses, felt able to approach the MHNC for assistance without discomfort or feelings of inadequacy.

The MHNC was seen as a nurse leader (Brinkman 2006) or a role model (Sharrock & Happell 2001) who promoted mental health nursing standards (Kurlowicz 2001). Being an expert who was trustworthy, professional, empathetic, consistent, collaborative, compassionate, tolerant, patient, non‐judgemental, and reliable were some of the attributes that were identified in MHNCs. Objectivity (Happell & Sharrock 2002; Roberts 1998), autonomy (Sharrock & Happell 2001), and holding an “outsider status” were identified as important to some participants as it allowed the MHNC “to observe situations from a broader perspective than those who were quite deeply entrenched in the ward culture” (Happell & Sharrock 2002, p. 57).

Two studies surveyed staff (n = 171) about their opinions of MHNC services in their respective GHs (Brinkman et al. 2009; Sharrock & Happell 2001). The findings reflected the high value placed on the MHNCs because clinical consultations were timely, relevant to the problem that triggered the request, clearly communicated, well‐documented, and delivered professionally and collaboratively. There was also a high level of satisfaction with the MHNC’s assessment, care planning and implementation, and follow‐up (Sharrock & Happell 2001).

The participants in four studies (Brinkman 2006; Brinkman et al. 2009; Happell & Sharrock 2002; Sharrock & Happell 2001) reported that the MHNC contributed to improved patient care outcomes. The elements of the clinical consultation that the participants perceived as contributing to positive outcomes were as follows:

the provision of assistance with developing a care plan (n = 10);

the provision of support, guidance, and education (n = 10) that facilitated staff to implement the care plan;

being present, visible, and regularly monitoring the patient and reviewing progress with staff enhanced continuity of care (n = 7); and

the expertise and attributes of the MHNC (n = 9).

Care plans were particularly valued when they were patient focussed, addressed practical nursing care delivery, included strategies, and facilitated a consistent approach that supported continuity. Regular contact and communication with the MHNC gave staff the opportunity to discuss care issues and clarify the mental health needs of the patient which helped them get “a clearer view of the clinical problem and an increased understanding of the patient’s predicament” (Kurlowicz 2001, p.57). Informal education, coaching, clinical supervision, and formal education sessions at ward level backed up with educational material and resources supported collaborative care planning.

Feedback from MHCLS medical staff was that they appreciated the MHNC’s ability to interpret and translate their assessments into a language and approach to care that could be understood and utilized by GH nurses (Sharrock et al. 2006). Given the understanding MHNCs had of mental health services as well as their ability to translate the mental health needs of the patient for all members of the multidisciplinary team, the MHNC was seen by some as well placed to coordinate mental health care of the patient.

However, allied health focus group participants expressed concern about what they perceived as a lack of role clarity and role boundaries in a newly introduced role (Sharrock et al. 2006). There was also concern about the limited resource where one MHNC was spread across large organizations (Brinkman et al. 2009; Happell & Sharrock 2002; Sharrock & Happell 2001). During the interviews undertaken by Brinkman (2006), there was discussion about the potential for GH nurses to become de‐skilled because of the readily available resource (Brinkman 2006, p.61). Of the overall positive responses in one staff survey, there was a single negative response to each survey question and a comment that suggested that the MHNC approach was “general and theoretical rather than specific and practical” (Sharrock & Happell 2001, p.265). Otherwise, there was a distinct absence of critical feedback from participants in this group of studies (n = 10). What remains unknown are the views and experiences of the staff who were less positive about the role and did not take the opportunity to complete surveys or undertake interviews.

MHNC increase GH staff’s competence and confidence in the provision of mental health care

The competence and comfort of GH nurses in providing psychologically based care was examined through the comparison of results of a pre‐ and post‐self‐assessment survey after the introduction of a MHNC service. Significant improvements in competence and comfort were found with a significant, positive, and strong correlation between competence and comfort (r = 0.987; p < 0.000). Areas of most improvement were in the care of patients with delirium and exhibiting behaviours described as demanding, impulsive, manipulative, and needy and least with patients who were violent, psychotic, or sexually provocative. Within the post‐introduction survey, there was a cross‐sectional 10‐item assessment of delirium knowledge. The answers to 6 of 10 questions were correct greater than 70% of the time. The questions most poorly answered related to hypoactive delirium and medication administration. A reduction in crisis consultation requests, use of CO, and security calls for patients with delirium reflected the increased competence and confidence in delirium care and a practice shift from coercive limit‐setting to safer and more knowledgeable care. It is important to note that the findings in this study should be considered cautiously as the response rate was low at 20.3%, and the instruments were not validated.

However, these findings are supported by nine studies where participants in GHs described increased knowledge, skill, and understanding of mental health through contact with MHNCs. Strategies applied in one clinical consultation assisted in the development of skills that could be used in other clinical situations (Sharrock et al. 2006). Kurlowicz (2001) undertook a thematic analysis of answers to their second survey question about what was helpful within the consultation. Essentially the respondents reported that they gained knowledge and understanding; experienced a sense of support and resolution of their clinical challenges; and their capacity to provide mental health care had improved. They developed more positive feelings and understanding towards patients, an increased capacity to manage and articulate the clinical issues, and an improved ability to advocate for patients. Consultations supported a person‐centred approach that linked theory with practice (Kurlowicz 2001).

Nurses interviewed by Brinkman (2006) described having developed skills that incorporated an holistic approach and had begun to recognize that connecting with and supporting patients did not necessarily take that much time. They had also learned about self‐care that supported them to be more self‐aware, comfortable within themselves, credible, and authentic.

Positive shifts in stigma and attitude to patients were reported (Brinkman 2006; Happell & Sharrock 2002; Kurlowicz 2001) but an attempt to measure the impact of a MHNC on staff attitudes to caring for people with a mental illness did not reflect this (Sharrock et al. 2006). However, this attitudinal survey was limited as the pre‐ and post‐survey respondents were unmatched, and the instrument was modified and not validated.

Anxiety containment

Knowing that a resource was available had a calming effect on the staff, for example, feeling “relief in being able to solve the patients’ clinical problems” (Kurlowicz 2001), feeling like they could “cope”, or a sense that “It’s going to be all right” when the MHNC is involved (Happell & Sharrock 2002). Repeated contact with the MHNC led to skill development (Sharrock et al. 2006) and anxiety containment (Happell & Sharrock 2002) which contributed to more considered and less reactive responses to patients. Lakatos (2009) observed that when staff understood what contributed to behavioural disturbance, they were more able to reduce the risk of harm, facilitate safe care, and reduce restrictive interventions, and that over time, requests for consultation demonstrated a more sophisticated understanding of mental health needs of patients.

The most recent study (Afriyie‐Boateng et al. 2019) reported on a survey of 64 of a possible 82 staff who had utilized the newly introduced pro‐active MHNC team. To examine their perception of their safety at work and burden of care from “challenging” patient behaviours, a subscale of a widely used North American Geriatric Institutional Assessment Profile was used. Fifty‐six nurses and eight allied health staff completed the survey, and these findings were compared to an unmatched group who had completed this sub‐scale in a hospital survey prior to the introduction of the service. There was a significant reduction in perception of burden of challenging behaviour despite the perception that the frequency of behavioural issues remained high. A sense of safety at work was enhanced knowing the service was available with 78% of the survey respondents linking safety with access to and support from the MHNC service.

Reflection on practice

Providing staff with opportunities to reflect on practice and debrief with a trusted professional who empathized, listened, and understood was highly appreciated by staff (n = 6). This supported nurses to “operate more freely and competently”, to feel more hopeful for the patients and reduced “confusion about the clinical problem” (Kurlowicz 2001, p.58). Reflection assisted nurses to deal with their response to caring for the person (Sharrock et al. 2006) and gave them “permission to talk about matters of the heart, matters that hurt” (Brinkman 2006, p.61).

DISCUSSION

In the context of the increasing prevalence of co‐existing physical and mental health conditions (AIHW 2021), amplified by the COVID‐19 pandemic (Lele et al. 2021), GHs are expected to meet the comprehensive care needs of patients (ACSQHC 2019) and provide sustained and high‐quality integrated mental health treatment, care, and support (State of Victoria 2021). Given the ongoing concerns about the quality of mental health care of GH patients, it is important that services are supported to meet these expectations.

MHNCs have been supporting GHs and their staffs in the mental health care of patients since the early 1960s (Robinson 1982). This literature review highlights that this role is generally well received and valued by GH staff, particularly nurses. It found that clinical consultations undertaken by MHNCs may improve patient experiences, influence aspects of care delivery, and increase staff competence and confidence in the provision of mental health care. The findings provide a more comprehensive understanding of the elements of the MHNC consultation and how these interventions may relate to improved outcomes.

The review also highlights the importance of interventions provided directly to patients and their relatives during clinical consultation, and interventions undertaken with staff, particularly collaborative care planning, support, and education. These findings are congruent with the wisdom that guided the development of the model of consultation to non‐mental health staff (Caplan 1970) that was applied to mental health nurse consultancy (Lewis & Levy 1982). This was refined using contemporary language, emphasizing collaboration with staff (Sharrock et al. 2006), and applying a capacity building approach where the MHNC:

is able to proactively create sustainable change as opposed to a reactive short‐term problem‐solving approach (Brunero & Lamont 2010).

Building the capacity of staff to provide mental health care of all GH patients through the development of both staff competence (knowledge, attitude, and skills) (Valizadeh et al. 2019) and confidence (being able to apply knowledge to practice in terms of actions and behaviour) (Zieber & Sedgewick 2018) is necessary for a sustained improvement in mental health care of GH patients. This is especially so given the high rates of mental health conditions in GH patients, the ongoing difficulties that GH nurses experience in attending to the mental health needs of GH patients, and the unresolved issue that Australian nurses continue to graduate with inadequate preparation in mental health (Happell et al. 2020).

In addition to the clinical consultation, organizational engagement was described in three of the studies examining the use of CO (Heyman & Lombardo 1995; Lakatos 2009; Rausch & Bjorklund 2010). The most recent of the included studies (Afriyie‐Boateng et al. 2019) also applied an organizational approach into a “Safe Patients/Safe Staff Program” that was:

Proactive through screening patients who might benefit from MHNC intervention coupled with rapid provision of identification and care for patients at “high risk” and/or with “high needs”;

Standardized approaches to patient care;

Skill‐building through extensive staff training using multiple modalities; and

Collaborative by involving the total organization in the cultural change.

The findings in this review align with the trend that a more assertive and intensive approach is associated with stronger outcomes (Oldham et al. 2019) and reinforce the value of a model of care that integrates clinical and organizational consultations (Sharrock et al. 2006).

While the existing MHNC research makes an important contribution to our understanding of MHNC services, this critical analysis and synthesis highlights considerable gaps and limitations. The most significant of these are that nearly all the studies were undertaken over 10 years ago, most evaluated one MHNC providing service across a large hospital setting, no studies were undertaken over more than one hospital, seven were of low quality, and studies were primarily cross‐sectional, exploratory, and descriptive. Given that MHNCs predominantly focus on facilitating improved mental health nursing care, it is not surprising that participants in the studies were primarily nurses. However, there are additional perspectives from which to evaluate MHNC services. Particularly absent were the views of patients and their relatives which is a significant gap when the consumer experience is a valued and necessary component of contemporary service delivery (ACSQHC 2019).

A limitation of seeking feedback from staff on a voluntary basis which requires varying degrees of individual effort above work as usual is the risk of response bias. Participation may have been more attractive to those who were positive about the service and wanted to support its ongoing provision. Kurlowicz (2001) speculated that the high positive ratings might be due to a reluctance of the consultees to provide negative feedback. Newton and Wilson (1990) argued to accept the findings at face value because the consultees were professional colleagues who had a good understanding of the goals and limitations of MHNC services. Using survey instruments that are predominantly self‐developed and not validated also increases the risk of response bias. Another limitation is that eight studies sought more global retrospective impressions of service and did not link the feedback closely to the consultation which may not accurately capture performance on a case‐by‐case basis (Newton & Wilson 1990).

It is recognized that it is a research challenge (Toynbee et al. 2021) to ascertain the impact of MHCLSs as there are multiple factors that contribute to outcomes in complex GH settings. The health conditions of patients are heterogenous and spread across an heterogenous group of wards and teams. It is not easy to evaluate MHNC services using RCTs or purely quantitative methods (Parsonage et al. 2012). It is also ethically questionable to conduct a study that denies patients a service that is almost commonplace in many Australian hospitals and is now expected in Victorian GHs (State of Victoria 2021).

However, given the pressing requirement for GHs to meet the mental health needs of patients, and the limited contemporary literature available on MHNC models and outcomes, it is timely to consider evaluation of the MHNC role. To ensure the specialist MHNC resource is optimally utilized, evaluation needs to examine the MHNC role within the multidisciplinary MHCLS, what and how MHNC interventions are provided, and how interventions link with outcomes (Kurlowicz 2001). Outcomes need to be determined from the perspective of multiple key stakeholders, allow for the heterogeneity of patients and hospital services, and align with policy development. What is needed is rigorous evaluation utilizing mixed research methods undertaken on more than one site with a developing or developed multidisciplinary MHCLS that is inclusive of nurses. Existing models of MHNC service delivery must be refined so that practice and policy is informed, and effective service delivery can be replicated.

CONCLUSION

The goal of this review was to address the absence of systematic analysis of evidence relating to the impact MHNCs have on the care of GH patients experiencing concurrent mental health conditions. This review has synthesized all published quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods studies relating to this topic. The review found that MHNC clinical consultation may improve patient experiences of mental health conditions; influence aspects of care delivery; are valued by staff, particularly nursing staff; and increase staff competence and confidence in the provision of mental health care. However, there are significant gaps in the available evidence: only one study has been undertaken within the last decade; most evaluated one MHNC providing service across a single large hospital; the perspective obtained was primarily from nurses; tools used were not validated with potential significant response bias; seven were low quality; and they were primarily cross‐sectional, exploratory, and descriptive. Further contemporary research is warranted to inform future MHNC service provision.

Relevance for Clinical Practice

The findings of this review demonstrate that MHNC expertise is a valuable resource and contributes to improved care of patients with a range of complex needs and “nuances of brain dysfunction” (Lakatos 2009, p.9) that can manifest as disturbed behaviour. It is important that mental health nurses who take on this role recognize the depth and breadth of what their skills offer and what mental health nursing can be. This does not mean an unbounded service, but it does mean that MHNCs are able to respond to requests for consultation regarding patients experiencing mental health conditions from a range of sources.

This review provides MHNCs, mental health clinicians, and managers with an accessible summary that gives a deeper understanding of the elements of a clinical consultation that are linked to positive outcomes. It reinforces the importance of not only the interventions undertaken by MHNCs with patients and relatives, but the interventions undertaken with staff, particularly the nurses, and the organization. Given the significant lack of confidence and competence that nurses have in providing mental health and nursing care, the MHNC must do more that assess, advise, and leave.