Abstract

Selecting the right dose is a significant challenge in designing clinical development programs, especially for slowly progressing diseases lacking predictive biomarkers of efficacy that may require long‐term treatment to assess clinical benefit. Gantenerumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody (mAb) that binds to aggregated amyloid‐beta, was tested in two 24‐month phase III studies (NCT01224106, NCT02051608) in participants with prodromal and mild Alzheimer’s disease (AD), respectively. Dosing in the first phase III study was suspended after a preplanned interim futility analysis in 2014. Subsequently, a dose–response relationship was observed in a subgroup of fast AD progressors that, together with contemporary aducanumab (another anti–amyloid‐beta mAb) data, indicated higher doses may be needed for clinical efficacy. The gantenerumab phase III studies were therefore transformed into dose‐finding, open‐label extension (OLE) trials. Two exposure–response models were developed to support dose selection via simulations for the OLEs: a pharmacokinetics (PK)/PET (positron emission tomography) model describing amyloid removal using PET data from low‐dose gantenerumab and high‐dose aducanumab, and a PK/ARIA‐E (amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities‐edema) model describing the occurrence of ARIA‐E events leveraging an existing bapineuzumab model. Multiple regimens were designed to gradually up‐titrate participants to the target dose of 1,200 mg gantenerumab every 4 weeks to mitigate the increased risk of ARIA‐E events that may be associated with higher doses of anti–amyloid‐beta antibodies. Favorable OLE data that matched well with model predictions supported the decision to continue the gantenerumab clinical development program and further apply model‐based analytical techniques to optimize the design of new phase III studies.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS THE CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON THE TOPIC?

☑ Alzheimer’s disease drug development has seen mainly failures over the last 20 years. Targeting brain amyloid may require much higher doses than originally anticipated. Class‐specific adverse events, amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities, could be mitigated with drug titration regimens.

WHAT QUESTION DID THIS STUDY ADDRESS?

☑ Are there signals that warrant continuation of a phase III program that was halted early for futility with gantenerumab, an anti‐amyloid antibody? How can modeling‐based approaches guide further drug development?

WHAT DOES THIS STUDY ADD TO OUR KNOWLEDGE?

☑ Alzheimer’s disease progression and competitor data, if translated into pharmacometric models, meaningfully adds to our understanding of clinical trial results and capability to further optimize trial design; it can give new directions for futile phase III programs within a short period. Open‐label extensions of unsuccessful trials provide opportunities to update these models for application in future studies for more efficient drug development.

HOW MIGHT THIS CHANGE CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY OR TRANSLATIONAL SCIENCE?

☑ This study emphasizes, yet again, the value of quickly deriving and updating quantitative models of disease progression and drug treatments.

Approximately 50 million people live with dementia worldwide, with nearly 10 million new cases every year. 1 Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is the most common form of dementia, accounting for approximately two thirds of cases. 2 Together, AD and other types of dementia are the seventh leading cause of death worldwide and the second leading cause of death in high‐income countries. 2 Despite considerable drug development efforts and a large unmet medical need, the only disease‐modifying therapy to be approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of AD has been the recent accelerated approval for the anti–amyloid‐beta (Aβ) antibody aducanumab in 2021, after demonstrating a reduction in Aβ plaque. 3 , 4 AD is characterized by the accumulation of amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. Amyloid plaques are composed primarily of aggregated Aβ peptide that is deposited in the brain parenchyma, likely decades before onset of clinical symptoms. 5

Gantenerumab is a fully human immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) anti‐Aβ monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to aggregated Aβ and promotes its removal by Fc receptor‐mediated phagocytosis. 6 In a phase I study in participants with mild to moderate AD, intravenous (IV) administration of gantenerumab (60 or 200 mg) resulted in a reduction in brain amyloid load over the course of 6 months. 7 However, at the higher dose, amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities–edema (ARIA‐E) and amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities–hemosiderosis (ARIA‐H; microbleeds) were detected. 7 ARIA are brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities associated with a variety of antibodies targeting Aβ in the brain. 8 Due to uncertainties around the impact of ARIA on patient safety, the higher of the two doses of gantenerumab evaluated in the first phase III study of gantenerumab in individuals with prodromal AD, SCarlet RoAD (SR), was lower than the upper dose used in phase I. 7 , 9 Monthly subcutaneous (SC) doses of 105 mg gantenerumab (equivalent to ~ 60 mg IV) were administered, independent of APOEε4 carrier status, and 225 mg gantenerumab (~ 135 mg IV) was administered to APOEε4 heterozygous carriers and noncarriers. Dosing in the SR study was discontinued for futility following an interim futility analysis (IFA) performed in 2014 when 50% of participants had completed 2 years of treatment. However, exploratory analyses of the trial data showed a promising effect on Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive Subscale 13 (ADAS‐Cog 13) scores in fast progressors. 9 Together with the insights on dosing gained from the publication of the outcomes in the PRIME study (Multiple Dose Study of Aducanumab (BIIB037) (Recombinant, Fully Human Anti‐Aβ IgG1 mAb) in Participants With Prodromal or Mild Alzheimer's Disease) of aducanumab 10 that became available shortly after the IFA, this information was sufficiently convincing to transform the study into an open‐label extension (OLE) with treatment administered over a 2‐year period. 7 , 9 A second phase III study, Marguerite RoAD (MR), in which participants with mild AD received 105 mg SC gantenerumab for 6 months, followed by 225 mg SC gantenerumab until Month 24 continued as per protocol until the results of the SR IFA became available. Based on the IFA findings, MR was also transformed into an OLE study with a 2‐year treatment administration. 11 , 12

In the present paper, we describe how pharmacometric modeling provided direction in the gantenerumab development program. In particular, we describe how disease progression and exposure–response models supported the decision to continue the clinical development of gantenerumab, the selection of notably higher doses than studied in phase I, and the design of OLE dosing regimens that aimed to balance pharmacodynamic (PD) activity (brain amyloid removal as assessed by positron emission tomography (PET)) and adverse events (ARIA‐E).

METHODS

Data sources

Relevant data were obtained from the gantenerumab study SR (NCT01224106), 9 aducanumab study PRIME (NCT01677572), 10 and bapineuzumab studies 301 and 302 (NCT00575055 and NCT00574132) for the development of the models. 13 Information on the design of the included studies is provided in Tables S1 and S2 . All studies were conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. All protocols were approved by their representative Institutional Review Boards or ethics committee. The study protocols have been described previously. 9 , 10 , 13 Written informed consent to participate was obtained from all participants or their legally authorized representatives or caregivers.

Pharmacokinetic model

The gantenerumab pharmacokinetic (PK) model was a standard two‐compartment disposition model, simultaneously applied to combined IV and SC data obtained from the gantenerumab phase I program (Table S3 ). 7 The absorption phase following SC administration was best described by a zero‐order followed by a first‐order process. Model equations were as follows (details of this model are presented in Supplement 1 ):

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

where t is the time after first drug administration, a is drug amount at absorption site, F is bioavailability, D SC is subcutaneous gantenerumab dose, D1 is the duration of the zero‐order absorption process for the subcutaneous administration, KA is first‐order absorption rate constant, c is central compartment drug concentration, Vc is volume of central compartment, D IV is the IV gantenerumab dose, CL is drug elimination clearance from central compartment, Q is intercompartmental clearance, cp is peripheral compartment drug concentration, and Vp is volume of the peripheral compartment.

This model was used to calculate average drug concentrations (C av) over periods of interest as a measure of drug exposure. It was also used to plug the PK time course into the PET and ARIA‐E models and used for the simulation of potential OLE titration schemes.

Identification of fast progressors

After the SR IFA, exploratory analyses were conducted to identify any subpopulations who may have experienced potential treatment benefits. For this purpose, we leveraged an existing AD disease progression model 14 that could reliably classify patients into slow or fast Clinical Dementia Rating Scale Sum of Boxes (CDR‐SB) progressors based only on their baseline CDR‐SB, Functional Activities Questionnaire, and hippocampal volume values. SR participants were classified accordingly.

Pharmacometric models to guide dosing regimen selection for OLE

The identification of potential dosing regimens for the OLE of SR/MR was based on two exposure–response models: a PK/PET model describing the effects of drug concentrations on brain amyloid as assessed by PET standardized uptake value ratios (SUVRs) and a PK/ARIA model describing the relationship between drug concentrations, time after start of treatment, and the first occurrence of an ARIA‐E event. This combination of models was used to identify a target dose / dosing regimen capable of removing ~ 20% of amyloid plaque after 1 year of treatment, with a predicted maximal ARIA‐E incidence of 25–30% at the end of a 2‐year study period. A 20% plaque removal was used as an anchor as it is associated with a statistically significant slowing of clinical decline measured by CDR‐SB at Week 52 of the PRIME study following treatment with 10 mg/kg of aducanumab. 10

PET model development

The PET model was developed using combined data from the gantenerumab SR study and the aducanumab PRIME study 10 (which tested intravenous doses of up to 10 mg/kg), as high‐dose information was not available for gantenerumab. Pooling of gantenerumab and aducanumab PK and PET information was considered acceptable after comparison of their physicochemical (molecular weight, immunoglobulin isotype) and PK/PD properties, and the available low‐dose data of aducanumab 1–3 mg/kg IV every 4 weeks (Q4W) (see Supplement 2 for further information). In both studies, brain amyloid removal was assessed by 18F–florbetapir amyloid PET. Standardized uptake values from five brain regions were integrated into a composite score (SUVR) with mean whole cerebellum as reference region and correlated with the estimated drug concentrations in plasma/serum. 7 , 15 Details of the model‐building process are described in Supplement 2 . Equations for the final population PET model were as follows:

| (4) |

| (5) |

where c is plasma concentration of gantenerumab, ce is the effect compartment concentration, t is time after first drug administration, SUVR is standard uptake value ratio, SUVR0 is baseline value of SUVR, Ke0 is rate constant for drug transfer from plasma into the effect compartment, and SLOP and POW are parameters driving the drug effect. Available covariate data were limited to that reported in the PRIME trial, and an exploratory graphical analysis was performed for PET baseline values, compound type, sex, and dose. A small trend was observed between PET baseline and estimated individual Ke0 values; however, this graphical analysis did not reveal any covariate relationships that would warrant further investigation.

ARIA model

In 2013, Hutmacher et al. 16 presented a hazard model for time‐to‐first ARIA‐E event, developed using data from phase III studies of bapineuzumab, 13 another anti‐Aβ monoclonal antibody. Their analysis showed that the first occurrence of an ARIA‐E event can be described by an equation combining the APOEε4 status, drug concentration, and time after the start of treatment:

| (6) |

where BSAPOEε4 is the ARIA‐E hazard without treatment, in either APOEε4 carriers or noncarriers. The drug effect is described by an Emax (maximum effect) model with bapineuzumab drug concentrations (c) and parameters Emax and EC50 (concentration producing 50% of the maximum effect). This effect is attenuated with time after first drug administration (t); T 50 (half maximum time effect) and γ (sigmoidicity parameter) are parameters shaping the time effect. This model was applied to SR double‐blind period (DB) data using the population PK model of gantenerumab described above (see PK model section). Due to the low number of ARIA‐E events in SR DB, only drug effect parameters specific to gantenerumab (Emax and EC50) could be estimated (NONMEM v7.3, ICON, Dublin, Ireland). All other parameters (BSAPOEε4 (with separately estimated values for carriers and noncarriers), T 50, and γ) were fixed to values derived from bapineuzumab studies 301 and 302. 16 Details of this model are presented in Supplement 3 .

To test the general applicability of the model for higher doses, ARIA‐E events for high‐dose aducanumab were predicted using the newly estimated ARIA model parameters, which were coupled with aducanumab PK data and plotted against the reported ARIA‐E events from the aducanumab PRIME study. Results indicated that the model was suited for this purpose (details described in Supplement 3 ).

Simulation of fixed dose and titration regimens for OLEs

The use of titration regimens was suggested by Hutmacher et al., 16 who hypothesized that due to the observed time‐dependent reduction in ARIA‐E risk, introducing higher doses later in the course of the trial should mitigate the risk of ARIA‐E events. To inform the selection of titration regimens for the SR and MR OLEs, extensive simulations were performed using the PK, PET, and ARIA models with PK model parameters fixed at their population values.

Fixed high‐dose regimens of gantenerumab were simulated to assess the potential effects of higher doses of gantenerumab on PET SUVR. In addition, titration regimens were compared with fixed high‐dose regimens to assess the positive impact on the predicted ARIA‐E incidence. The goal of these simulations was to optimize the benefit/risk profile, i.e., to achieve a significant reduction in the PET signal after 1 year of treatment, with an acceptable cumulative ARIA‐E event rate over 2 years for both APOEε4 carriers and noncarriers.

Prediction intervals for the PK/PET model were calculated at a 1‐year dense time grid. The model individually simulated the data from 500 participants with PET model parameters that varied according to their estimated between‐subject variance (Tables S4 and S5 ). A 90% prediction interval was calculated from the 5% and 95% percentiles of calculated SUVR percent change from baseline.

For the PK/ARIA model, the predicted proportion of events was calculated using PK parameters (as above). As there was no between‐subject variability for the ARIA model, no prediction interval for the proportion of events was calculated.

Comparison of OLE data with model predictions

Observed values in the SR and MR OLEs for SUVR after 1 year and for ARIA‐E events after 2 years 12 were compared with the respective model predictions. Predictions of the individual change from baseline in SUVR over time and the ARIA‐E cumulative event trajectories were performed using the fixed‐effect population values for the PK/PET and PK/ARIA models (Tables S4 – S6 ), with the individual gantenerumab doses received by participants. Baseline SUVR was defined as the last SUVR value before the start of the OLE. As there were considerable differences between SR and MR participants with respect to prior exposure and stage of AD, OLE participants were classified into four groups: SR‐DBP/SR‐DBA (participants from SR who received either a placebo, or active treatment in the DB) and MR‐DBP/MR‐DBA (participants from MR who received either a placebo, or active treatment in the DB). For SUVR, mean and 90% confidence intervals (based on t statistics) were calculated. For ARIA‐E, the proportion of participants expected to experience an ARIA‐E event within the first 2 years of treatment was calculated along with a 90% confidence interval based on the score statistics for proportions. 17 Additionally, the impact of applied titration regimens on the observed and predicted SUVR changes from baseline and ARIA‐E rates were examined.

RESULTS

Treatment effects in the SR DB

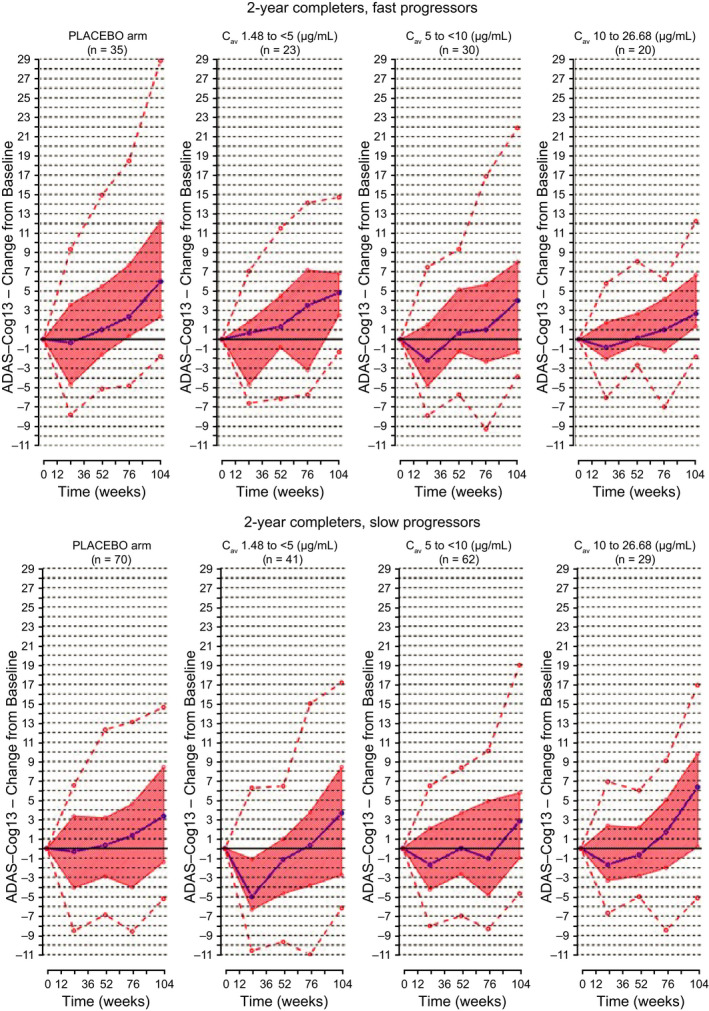

In the DB part of the SR study, no statistically significant treatment effect was observed in the overall population based on the primary end point assessed, CDR‐SB, leading to the study being stopped early for futility. However, application of the disease progression model to define subgroups of slow and fast progressors based on Delor et al. 14 criteria revealed a trend of a dose‐dependent drug effect on ADAS‐Cog13 scores in the fast progressor population of SR, 9 but not among the two‐thirds of participants classified as slow progressors. The trend towards a dose effect was confirmed by a graphical drug concentration–response analysis in the fast progressor subpopulation. As shown in Figure 1 , for the participants who completed 2 years of treatment, increasing drug exposure was associated with consistently lower scores on the ADAS‐Cog13 scale, with up to a 3‐point median reduction after 2 years in the highest exposure category compared with a placebo. Similar plasma concentration‐dependent trends were observed for the Mini‐Mental State Examination and the Cambridge Neuropsychological Test Automated Battery (CANTAB), but not for CDR‐SB. This signal in fast progressors supported the decision to continue gantenerumab drug development.

Figure 1.

ADAS‐Cog13 change from baseline vs. time in SR classified by drug exposure. Upper panels: 2‐year completers, fast progressors; lower panels: 2‐year completers, slow progressors; purple line, median change from baseline; orange shaded area, interquartile range; orange dotted lines, 5th and 95th percentiles of observations. ADAS‐Cog13, Alzheimer's Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive Subscale 13 items; Cav, average drug concentrations; SR, SCarlet RoAD.

Selection of the new target dose

The median tendency and between‐subject variability in the SUVR changes from baseline in all drug exposure groups were well captured by the PK/PET model for the combined SR gantenerumab and PRIME aducanumab data sets, as indicated by visual predictive checks, shown in Figure S6 .

The PET model was then used to estimate the gantenerumab dose that would lead to 20% plaque removal after a year of Q4W dosing. As shown in Figure 2 (top‐left panel), a target dose of 1,200 mg gantenerumab fulfilled this goal.

Figure 2.

Simulation of treatment effects on SUVR and ARIA‐E rates with respect to APOEε4 status: SC 1,200 mg Q4W (left panel), fast (middle panel) and slow (right panel) titrations up to 1,200 mg Q4W. Q4W Slow titration regimen (dose, number of doses): 105 mg (3) to 225 mg (3) to 450 mg (2) to 900 mg (2) to 1,200 mg; Q4W fast titration regimen (dose, number of doses): 300 mg (2) to 600 mg (2) to 1,200 mg. Solid line, ARIA (cumulative proportion of ARIA‐E events), SUVR (median); gray area, 5–95% percentile range. APOEε4, apolipoprotein E ε4; ARIA‐E, amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities – vasogenic edema; CFB, change from baseline; PET, positron emission tomography; Q4W, every 4 weeks; SC, subcutaneous; SUVR, standardized uptake value ratio.

Dosing regimen selection for the OLEs

After the selection of the target dose that was expected to result in a meaningful plaque removal, the PET and ARIA models were used together to inform the selection of dosing regimens for the OLEs.

Figure 2 illustrates the effects of different titration regimens on PET SUVR and ARIA‐E incidence in comparison with a fixed dose of 1,200 mg SC Q4W. The fixed dose of 1,200 mg SC Q4W could result in a 20% PET reduction at Year 1 but had a high predicted rate of ARIA‐E, with up to 60% ARIA‐E incidence in APOEε4 carriers.

The titration regimens tested resulted in slower plaque removal, compared with higher dose gantenerumab, especially at the beginning of treatment. However, all regimens were predicted to show similar plaque removal after 2 years of treatment. ARIA‐E incidence after up‐titration to 1,200 mg Q4W was significantly lower compared with fixed dosing, and dependent on the speed of up‐titration.

Based on the anticipated risk in the population, and the fact that participants in SR were on average off‐treatment for 89 weeks between the end of the SR DB and the start of the OLE, several dosing regimens were tested in the SR / MR OLEs. This approach was also expected to better inform further refinements of the PET and ARIA models than a single‐dosing regimen in all participants. Figure 3 describes the dosing regimens tested in the OLEs. Dependent on the last dose in the double‐blind phase, the APOEε4 carrier status, and the study, participants were assigned to five different dosing regimens. The regimens differed in starting dose, number of steps, and time to reach the target dose of 1,200 mg.

Figure 3.

Year 1 of the 2‐year titration regimens selected for testing in SR/MR OLEs. APOEε4, apolipoprotein E ε4; MR, Marguerite RoAD; OLE, open‐label extension; PBO, placebo; SR, SCarlet RoAD.

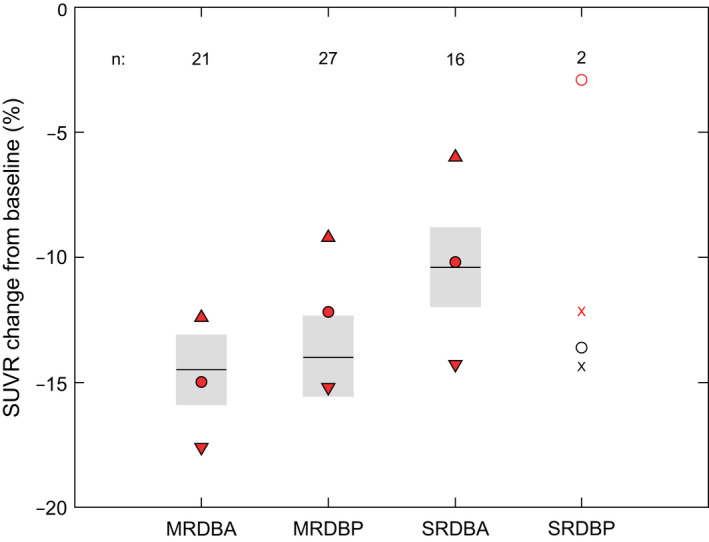

Comparison of OLE data with PK/PET model predictions

Observed data from Year 1 of the OLE for the relative change from baseline in SUVR were compared with model predictions. As shown in Figure 4 , the predictions were in good agreement with the observed data (maximum group mean difference of 2.2%), indicating that the model was able to describe the plaque removal associated with higher and differing doses of gantenerumab. This result is in line with the analysis by titration regimen (Table 1 ).

Figure 4.

PET SUVR change from baseline (%) at Year 1 in OLEs. The model used the complete (DB and OLE) dosing histories. SUVR baseline is defined as the value nearest to start (= dosing) in OLE. Red symbols, mean, and 90% confidence intervals of observations; black line and gray shaded areas: mean and 90% confidence interval of predictions. MRDBA, Marguerite RoAD double‐blind active treatment group; MRDBP, Marguerite RoAD, double‐blind placebo group; OLE, open‐label extension; PET, positron emission tomography; SRDBA, SCarlet RoAD double‐blind active treatment group; SRDBP, SCarlet RoAD double‐blind placebo group; SUVR, standardized uptake value ratio.

Table 1.

SUVR results (Year 1) by titration regimen

| Titration regimen | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | SR | SR | SR | MR | MR | MR | MR |

| Last dose DB (mg) | 0, 105 | 0, 105, 225 | 225 | 0, 105 | 225 | 0, 105 | 225 |

| APOEε4 carrier | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| Number of individuals | n = 6 | n = 2 | n = 6 | n = 19 | n = 10 | n = 10 | n = 8 |

|

SUVRCFB%, mean predicted change based on planned OLE regimen |

−12.2 | −17.1 | −17.1 | −17.1 | −18.9 | −18.7 | −19.7 |

|

SUVRCFB%, mean, (SD) predicted change based on dose received in OLE |

−12.2 (1.6) | −10.3 (7.1) | −13.1 (1.1) | −12.3 (5.4) | −15.0 (2.5) | −16.6 (3.0) | −15.4 (3.4) |

|

SUVRCFB%, mean (SD) observed in OLE |

−9.2 (10.5) | −4.2 (6.3) | −12.7 (11.0) | −12.6 (9.0) | −16.3 (7.5) | −11.2 (9.0) | −14.8 (7.5) |

|

Predicted vs. observed P value (paired t test) |

0.56 | 0.64 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.68 | 0.13 | 0.82 |

APOEε4, apolipoprotein E ε4; DB, double‐blind period; MR, Marguerite RoAD; OLE, open‐label extension; PET, positron emission tomography; PK, pharmacokinetic; SD, standard deviation; SR, SCarlet RoAD; SUVR, standard uptake value ratio; SUVRCFB%, standard uptake value ratio percent change from baseline.

Comparison of OLE data with ARIA‐E model predictions

To assess the predictive performance of the ARIA‐E model, the observed ARIA‐E events at Year 2 of the OLE trials were compared with predictions using a similar procedure used for the comparison of PK/PET model predictions with OLE SUVR data. As shown in Figure 5 , the model captured the ARIA‐E events of the former placebo and active treatment groups from SR and MR reasonably well. However, the model had the tendency to underestimate ARIA‐E event rates.

Figure 5.

Proportions (%) of subjects with ARIA events at Year 2 in the OLE per DBP and DBA groups. The model used OLE dosing history data only and did not include data from the DB phase. Red symbols, proportions of observed events and 90% binomial score intervals; black line and gray shaded areas, proportion of predicted events and 90% binomial score intervals. APOEε4, apolipoprotein E ε4; ARIA‐E, amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities; DBA, double‐blind active treatment group; DBP, double‐blind placebo group; MRDBA, Marguerite RoAD double‐blind active treatment group; MRDBP, Marguerite RoAD double‐blind placebo group; obs, observed; SRDBA, SCarlet RoAD double‐blind active treatment group; SRDBP, SCarlet RoAD double‐blind placebo group.

Analysis by titration regimen revealed that the model predicted the ranking order of ARIA‐E proportions across the treatment groups correctly for APOEε4‐negative participants, although with a small, consistent underestimation. In APOEε4‐positive participants, reliable predictions were achieved for up‐titrations in MR, but in SR the predictions showed statistically significant deviations from the observed events. Titration regimen 1 was associated with more ARIA‐E events than expected (36.5% vs. 19.4%), while there were fewer events than expected in titration regimen 3 (17.9% vs. 38%) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

ARIA‐E results (Year 2) by titration regimen

| Titration regimen | 1 a | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| study | SR | SR | SR | MR | MR | MR | MR |

| Last dose DB (mg) | 0, 105 | 0, 105, 225 | 225 | 0, 105 | 225 | 0, 105 | 225 |

| Carrier | + | − | + | + | + | − | − |

| Number of individuals | n = 74 | n = 44 | n = 28 | n = 83 | n = 60 | n = 45 | n = 33 |

|

ARIA‐E, proportion (%) predicted proportion based on planned OLE regimen |

20.8 | 11.6 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 51.2 | 13.6 | 18.2 |

|

ARIA‐E, proportion (%) predicted proportion based on dose received in OLE |

19.4 | 10.4 | 38.0 | 32.2 | 46.8 | 12.4 | 16.5 |

|

ARIA‐E, proportion (%) observed in OLE |

36.5 | 13.6 | 17.9 | 34.9 | 38.3 | 22.2 | 24.2 |

|

Predicted vs. observed P value (score test for proportions) |

0.003 | 0.69 | 0.01 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.41 |

ARIA‐E, amyloid related imaging abnormality–edema; DB, double‐blind period; MR, Marguerite RoAD; OLE, open‐label extension; SR, SCarlet RoAD.

35 patients on placebo; 39 patients on active in DB.

DISCUSSION

The most critical factors for successful clinical development of therapeutics are achieving the correct target, tissue exposure, dose, patient population, and safety profile. 18 Despite all the efforts to understand the disease biology, there are still many uncertainties around these factors in AD, contributing to the high failure rate of therapeutics in clinical development. One of the most challenging decisions during drug development is the dose selection to advance into late‐phase clinical trials. The increasing attrition rate in phase III trials is, at least in part, due to improper dose selection; selecting a dose that is too low may not achieve the desired benefit, while a dose that is too high may result in an unacceptable safety profile. 19 A workshop at the European Medicines Agency/European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EMA/EFPIA) highlighted inadequate dose selection in confirmatory trials as one of the most challenging issues in drug development. 20 Several advanced methods, including pharmacometrics, were recommended for designing clinical trial dosage regimens as applied here in the clinical development of gantenerumab. 20

The decision to transform SR and MR into OLEs was supported by the application of the Delor model 14 and the detection of a signal in fast progressors for gantenerumab dose‐dependent decline in ADAS‐Cog13, CANTAB, and Mini–Mental State Examination (MMSE). 9 The prespecified analyses did not find any relevant signals from the cognitive end points; however, the Delor model subsequently revealed that two‐thirds of participants in SR were slow progressors. 9 This is important as the detection of treatment effects largely depends on disease progression in the control group during the study period. Using the disease model, SR participants were assigned to the slow or fast disease‐progressing population based only on their baseline characteristics, which allowed us to observe a treatment signal in the population who were most likely to progress during the observation period of the study. This application of the Delor model to SR was part of a post hoc exploratory analysis of SR, but demonstrates the value of using such models to optimize trial design.

However, uncertainties remained due to the low number of participants in the fast‐progressor subgroup, and considering that treatment effects were observed in multiple secondary end points (ADAS‐Cog13, CANTAB, and MMSE) but not the primary end point of CDR‐SB. 9 Following the IFA, confidence in the amyloid hypothesis in AD was bolstered by the outcomes from the aducanumab PRIME study, which showed that treatment benefit could be achieved after administration of higher doses. However, higher doses of anti‐amyloid antibodies were associated with more ARIA events, as shown by the PRIME study 10 and our multiple ascending dose trial (NCT00531804). 7 Therefore, the clinical benefits of a dose increase must be weighed against the increased risk of ARIA. Through extensive simulations of titration regimens, our PET and ARIA models were instrumental in enabling the balancing of the benefits and risks of higher gantenerumab doses.

For the development of the PET model, internal data from the SR DB were not sufficient to reliably estimate the drug effect at higher doses. Therefore, we integrated PET information from all doses of aducanumab tested in the PRIME study. 10 A comparison of gantenerumab and aducanumab suggested that the molecules were similar enough to combine the PET information for this approach (Supplement 2 ). Both lower dose groups (1 and 3 mg/kg) indicated that the systemic exposure – PET SUVR relationship was comparable, and data from the higher two dose groups (6 and 10 mg/kg) gave reliable model parameter estimates for larger observed drug effects on PET SUVR. A comparison of the predicted plaque removal with the observed PET data from the OLEs supported this assumption (Table 1 ). Predictions of the change from baseline in SUVR, made before the start of OLE, did not differ from OLE observations by more than 7% for all titration regimens apart from regimen 2 (comprised of only two participants). The PET model did not include natural plaque accumulation over time as a separate process, as we did not observe a meaningful accumulation in the placebo group of the SR DB. This omission was considered acceptable for the purpose of this PET model. However, in the future, we plan to incorporate natural plaque accumulation into the model to provide guidance on questions around the effect of withdrawal of gantenerumab on plaque re‐accumulation, as well as its impact on long‐term treatment efficacy, in which natural plaque accumulation may be an important factor in the prediction of long‐term treatment outcomes.

On June 7, 2021, the FDA approved aducanumab in patients with AD based on the evidence that it reduces amyloid beta plaques in the brain and that the reduction in these plaques is reasonably likely to predict clinical benefit. 4 The PET results of the aducanumab phase III trials (Emerge and Engage 21 , 22 ) also confirmed our strategy to include the PRIME PET data into our modeling framework to select the dose for subsequent gantenerumab trials. However, the significant controversy about the aducanumab approval due to a lack of a direct correlation between plaque removal and clinical efficacy shows that additional efforts are needed to connect PK, biomarker, and efficacy data in a quantitative framework to validate a biomarker as a surrogate end point for disease‐modifying therapies in AD.

The ARIA‐E time‐to‐first‐event model was originally developed by Hutmacher et al. 16 using 243 ARIA events observed after IV administration of bapineuzumab (0.5, 1, or 2 mg/kg) every 13 weeks. Application of the model structure to SR data with parameter re‐estimation was unsuccessful due to only 50 ARIA‐E events having been observed. For this reason, model parameters expected to be linked to the ARIA‐E hazard over time (T50 and γ) were fixed to the results from the bapineuzumab data. We assumed a shared pathophysiologic basis for occurrence of ARIA‐E and the hazard time effect by both drugs. The dose increase was expected to incur a penalty (i.e., that the concentration‐dependent risk of having an ARIA‐E event would increase more than the mitigating effect of time in the model), but due to lack of experimental information we could not include this in the model.

The estimated parameters for T50 and γ imply they have a strong effect on the severity of ARIA‐E hazard over time. Using the current model with a fixed dose of Q4W 225‐mg gantenerumab applied to a cohort of APOEε4 carriers, one would expect 20% of the population to have a first ARIA‐E event within the first 2 years, followed by an additional 2.5% in the subsequent 2 years. Excluding the effect of time, one would get much higher rates of 56% and 24%, respectively. If the dose was increased to 1,200 mg after 2 years, one would expect an additional increase of 3% and 43% with and without consideration of the effect of time. Thus, the hazard‐decreasing time effect in the ARIA model nearly eliminates the hazard‐increasing effect due to a dose increase to 1,200 mg Q4W. Consequently, we avoided applying the ARIA model to the complete dosing history (from first dose in DB) in participants that were included in OLEs, but rather started from time after the first dose in the OLE.

In Figure 5 the predicted ARIA‐E rates, when compared with the observed values, appear to show that the model has a tendency to underestimate the rate of ARIA‐E occurrence. This was particularly true for slow titration regimen 1 (Table 2 ). This indicates that the model may be less capable of predicting the effects of slow titration regimens where the effect of time may have offset the effect of up‐titration using its current parameter values. The marked difference of ARIA‐E rates for titration regimen 3 (predicted: 38%; observed: 18%) may be due to a selection bias of participants. Regimen 3 consisted of participants who received the higher (225 mg) gantenerumab dose in SR DB and had no major ARIA‐E events. A similar finding is shown for titration regimen 5, in which APOEε4‐positive participants who previously received 225 mg gantenerumab experienced fewer events than predicted. More detailed results are presented in Table 2 .

As explained above, the time effect of the ARIA model is challenging, as the impact of treatment interruptions (such as those seen in SR) is not well captured. To adapt the model to such drug‐free periods, one needs to implement a mechanism that brings the ARIA‐E hazard back to “normal” values, to “reset the clock.” Another issue is the tendency of the model to underestimate ARIA‐E events if up‐titration is slow. Without a major revision of the model, a re‐estimation of model parameters using OLE data could be a quick remedy. However, this was not an objective for the current investigation. Further refinements to the PET and ARIA model were subsequently undertaken in the development of the final dosing regimen for the GRADUATE pivotal phase III program and will be described elsewhere.

The ARIA model was only developed for ARIA‐E and not ARIA‐H, which is a limitation of our approach. 16 ARIA‐H was not considered due to a lack of available data and an unclear relationship of ARIA‐H to gantenerumab dose. However, there was a clear relationship between ARIA‐E and gantenerumab dose in the SR DB population. 9 Another limitation of the model is that it only captured the first occurrence of an event. Modeling activities to promote a better understanding of the relationship between an individual’s characteristics (e.g., amyloid load at baseline, amyloid removal, APOEε4 status) and dosing vs. ARIA severity and recurrence are ongoing.

Our exposure–response model approach for OLE dose selection combined external and internal information to guide the further clinical development of gantenerumab. It allowed the identification of a dose that should be able to significantly remove amyloid plaque and informed how this target dose could be achieved while mitigating treatment‐related safety risks (ARIA‐E). By extending SR and MR to OLEs, confirmation studies that were halted early for futility were successfully converted into a new valuable resource that provided validation of new models developed to evaluate the potential benefits and risks of dose titration regimens. These models helped inform the study design for the ongoing gantenerumab GRADUATE program, and their wider application will continue to help inform dosing regimens in future studies. Further enhancements to these models are under consideration, for instance, taking into account the kinetics of amyloid turnover for the PET model, or the loss/gain of sensitivity to ARIA‐E events with respect to treatment gaps in the ARIA model. These modifications should support the safe and effective use of anti‐amyloid antibody treatments.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was funded by F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

S.R.: employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd. R.G.: consultant to F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd and shareholder of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd. D.S.: consultant to F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd and shareholder of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd. C.W.: employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd. N.F.: employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd. C.H.: employee and shareholder of F. Hoffmann‐La Roche Ltd.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.H., R.G., S.R., D.S., C.W., and N.F. wrote the manuscript. C.H. and S.R. designed and performed the research. S.R., R.G., D.S., and C.H. analyzed the data.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dominik Lott, F. Hoffmann‐La Roche, for his assistance with the production of the visual predictive checks. Editorial support with the development of this manuscript was furnished by Chris Ackroyd, MSc, of Health Interactions, funded by F. Hoffmann‐La Roche.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

For up to date details on Roche's Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: https://go.roche.com/data_sharing. Requests for the pharmacokinetic modeling data underlying this publication requires a detailed, hypothesis‐driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and company subject matter experts. Direct such requests to carsten.hofmann@roche.com for consideration. Anonymised records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche can not, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient re‐identification.

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . Dementia fact sheet <https://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/dementia>. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO) . The top 10 causes of death <http://www.who.int/en/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/the‐top‐10‐causes‐of‐death>. Accessed September 29, 2020.

- 3. Bullain, S. & Doody, R. What works and what does not work in Alzheimer's disease? From interventions on risk factors to anti‐amyloid trials. J. Neurochem. 155, 120–136 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. US Food and Drug Administration . FDA Grants Accelerated Approval for Alzheimer’s Drug <https://www.fda.gov/news‐events/press‐announcements/fda‐grants‐accelerated‐approval‐alzheimers‐drug> (2021).

- 5. Jack, C.R. Jr et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet Neurol. 12, 207–216 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bohrmann, B. et al. Gantenerumab: a novel human anti‐Aβ antibody demonstrates sustained cerebral amyloid‐β binding and elicits cell‐mediated removal of human amyloid‐β. J. Alzheimers Dis. 28, 49–69 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ostrowitzki, S. et al. Mechanism of amyloid removal in patients with Alzheimer disease treated with gantenerumab. Arch. Neurol. 69, 198–207 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sperling, R.A. et al. Amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities in amyloid‐modifying therapeutic trials: recommendations from the Alzheimer's Association Research Roundtable Workgroup. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 367–385 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ostrowitzki, S. et al. A phase III randomized trial of gantenerumab in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 9, 95 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sevigny, J. et al. The antibody aducanumab reduces Aβ plaques in Alzheimer's disease. Nature 537, 50–56 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Abi‐Saab, D. et al. Update on the safety and tolerability of gantenerumab in the ongoing open‐label extension (OLE) of the Marguerite RoAD study in patients with prodromal Alzheimer's disease (AD) after approximately 2 years of study duration. Alzheimers Dement. 14, Abstract O1‐09‐04 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12. Klein, G. et al. Gantenerumab reduces amyloid‐β plaques in patients with prodromal to moderate Alzheimer’s disease: a PET substudy interim analysis. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 11, 101 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Salloway, S. et al. Two phase 3 trials of bapineuzumab in mild‐to‐moderate Alzheimer's disease. N. Engl. J Med. 370, 322–333 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Delor, I. , Charoin, J.E. , Gieschke, R. , Retout, S. & Jacqmin, P. Modeling Alzheimer's disease progression using disease onset time and disease trajectory concepts applied to CDR‐SOB scores from ADNI. CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 2, e78 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sevigny, J. et al. Amyloid PET screening for enrichment of early‐stage Alzheimer disease clinical trials: experience in a phase 1b clinical trial. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 30, 1–7 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hutmacher, M. et al. Pharmacokinetic‐pharmacodynamic modeling of amyloid‐related imaging abnormalities of edema following intravenous administration of bapineuzumab to subjects with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 40, Abstract W‐040 S015–S149 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casella, G. & Berger, R.L. Statistical Inference 2nd edn (Thomson Learning, Pacific Grove, CA, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cook, D. et al. Lessons learned from the fate of AstraZeneca's drug pipeline: a five‐dimensional framework. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 419–431 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Antonijevic, Z. , Pinheiro, J. , Fardipour, P. & Lewis, R.J. Impact of dose selection strategies used in phase II on the probability of success in phase III. Stat. Biopharm. Res. 2, 469–486 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 20. Musuamba, F.T. et al. Advanced methods for dose and regimen finding during drug development: summary of the EMA/EFPIA workshop on dose finding (London 4–5 December 2014). CPT Pharmacometrics Syst. Pharmacol. 6, 418–429 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Biogen . 221AD302 Phase 3 Study of Aducanumab (BIIB037) in Early Alzheimer's Disease (EMERGE) <https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02484547> NLM Identifier: NCT02484547. Accessed December 2021.

- 22. Biogen . 221AD301 Phase 3 Study of Aducanumab (BIIB037) in Early Alzheimer's Disease (ENGAGE) <https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02477800> NLM Identifier: NCT02477800. Accessed December 2021.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Material

Data Availability Statement

For up to date details on Roche's Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see here: https://go.roche.com/data_sharing. Requests for the pharmacokinetic modeling data underlying this publication requires a detailed, hypothesis‐driven statistical analysis plan that is collaboratively developed by the requestor and company subject matter experts. Direct such requests to carsten.hofmann@roche.com for consideration. Anonymised records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche can not, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient re‐identification.