Abstract

The ability of Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus administered in yogurt to survive the passage through the upper gastrointestinal tract was investigated with Göttingen minipigs that were fitted with ileum T-cannulas. After ingestion of yogurt containing viable microorganisms, ileostomy samples were collected nearly every hour beginning 3 h after food uptake. Living L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus were detected in the magnitude of 106 to 107 per gram of intestinal contents (wet weight) in all animals under investigation. A calculation of the minimum amount of surviving bacteria that had been administered is presented. Total DNA extracted from ileostomy samples was subjected to PCR, which was species specific for L. delbrueckii and S. thermophilus and subspecies specific for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus. All three bacterial groups could be detected by PCR after yogurt uptake but not after uptake of a semisynthetic diet. One pig apparently had developed an endogenous L. delbrueckii flora. When heat-treated yogurt was administered, L. delbrueckii was detected in all animals. S. thermophilus or L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was not detected, indicating that heat-inactivated cells and their DNAs had already been digested and their own L. delbrueckii flora had been stimulated for growth.

Most studies investigating survival during intestinal passage of probiotic bacteria have focused on strains of the genera Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium (34). These strains are not traditionally used as starter cultures for milk fermentations. On the other hand, typical starter bacteria like Lactococcus lactis (3, 7, 18), Streptococcus thermophilus, and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. lactis or bulgaricus (2, 4, 30) have only rarely been used in animal or human in vivo studies, because they are not considered to exert health benefits comparable to those of probiotic strains.

Survival of the intestinal transit is one of the preconditions for microorganisms to develop any beneficial effects after consumption. It is demanded that potential probiotic bacteria should be able to survive the low pH values of the stomach and to tolerate the bile salts in the duodenum (4, 8, 11, 17, 21, 29). First survival tests for potential probiotic strains were mostly performed in vitro. When exposed, e.g., in vitro to human gastric juice, Lactobacillus gasseri and Lactobacillus acidophilus showed better survival than L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, whereas S. thermophilus exhibited only poor survival (4). In another study, bifidobacteria isolated from the human gastrointestinal tract proved significantly less resistant to gastric juice than the lactobacilli tested (8). It is also known that probiotic bacteria vary considerably in their levels of bile tolerance (17). Thus, in vivo testing of survival appears to be indispensable. Pochart et al. (30) detected viable starter bacteria in human duodenal samples after fresh yogurt ingestion. In addition, it is more and more accepted that the way bacteria are administered is decisive for their survival and that they may be quite protected against, e.g., acidity, by the substrate they are consumed with (4, 7, 16, 30).

To effectively fulfill a beneficial or prophylactic role, probiotic strains must be capable of colonizing the intestine at least transiently. Certain adhesion capacities of the bacteria appear to be restricted to the host species (12, 13, 14) they were originally isolated from. However, more often it is observed that they are washed out from the gastrointestinal tract after cessation of continuous uptake (12, 20, 35).

Many studies on survival of administered bacteria have been conducted by sampling feces. As enumerations in feces do not truly reflect survival during transit in the upper gastrointestinal tract, our goal was to monitor survival in the small intestine (terminal ileum) at the entrance to the large bowel. In our study we used the model system of fistulated minipig. The animals had been shown earlier to remain in good health over long periods of cannulation. Thus, series of diets can be tested allowing frequent sampling under nearly normal conditions. It is also described that the flora appears to be unaffected by the presence of the fistulas (22). S. thermophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus are usually not part of the indigenous flora of mammals, although another subspecies (lactis) of the latter one is usually found in the human and porcine gastrointestinal tracts (6).

In the present study, yogurt containing living S. thermophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was fed to minipigs. By applying a PCR-based approach in combination with phenotypic identification methods, both microorganisms could be recovered alive from ileostomy contents. S. thermophilus was additionally identified on the strain level by phage typing. After extraction of nucleic acids from the chyme we were able to compare the effect of three different diets (a defined semisynthetic diet, a heat-treated yogurt, and a yogurt containing living starters) with respect to the detection of the species L. delbrueckii, of the ingested subspecies bulgaricus (which was distinguished from the indigenous lactis population), and of S. thermophilus. We also describe the time kinetics of the appearance of the organisms and their survival rates at the terminal ileum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media and growth conditions.

Lactobacilli were grown on Rogosa agar (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) or in MRS medium (5). Streptococci were grown on tM17 (19) agar at about 40°C. Bacillus stearothermophilus was grown on plate count agar (Merck) at 60 to 65°C.

Bacterial strains.

For fermentation of yogurts, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus Kt4 and S. thermophilus 71 or 55n were used. The strains were from the collection of the Institute for Microbiology at the Federal Dairy Research Center.

Fermentation of yogurt.

Ultrahigh-temperature-treated milk was heated to 100°C for 10 min before starter cultures were added. After cooling, incubation proceeded at 42°C until the yogurt was set. Yogurts were prepared 1 and 2 weeks before uptake. Heat-treated yogurt was prepared by heating to 80°C and keeping the temperature for 30 min, with casual stirring and immediate cooling afterwards.

Animals.

Göttingen miniature pigs, bred specific pathogen free (9), were fitted with T-cannulas at the terminal ileum and maintained during following years without problems. All experimental procedures described followed the guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and were approved by the Animal Care and Animal Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Environment of Schleswig-Holstein, Germany.

Feeding experiments were carried out with two or four pigs (mean body weight, 50 to 60 kg). During the experiments they were housed individually in metabolic cages. Four weeks before starting the experiments they were exclusively fed a semisynthetic diet.

Feeding experiments with fistulated Göttingen minipigs.

The feeding trials were carried out in two parts. The first part was designed to detect viable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and the second part—about 4 months later—to detect viable S. thermophilus. Experiments were carried out on four subsequent days with four and two individuals, respectively. For a better flow of the digesta, overnight fast was avoided and an additional day with semisynthetic diet (containing fibers) was introduced. The pigs were fed a semisynthetic diet on day 1 (Sacas 15 consisting of margarine [7.5%], lard [7.5%], cellulose [6.0%], vitamins and minerals [8.0%], corn starch [29%], sucrose [24%], casein [15%], Lacty [3%; Purac, Gorinchem, The Netherlands]). Six hundred grams of thermally treated yogurt (L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, S. thermophilus below the limit of detection) was applied on day 2, semisynthetic diet on day 3, and 600 g of yogurt with living starters on day 4. In the first experimental part, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus Kt4 counts were 5.8 × 108/g and in total were 3.5 × 1011. In the second experimental part, S. thermophilus 55n counts were 8 × 107/g and in total were 4.8 × 1010. CrIII2O3 (2%) was added to the heat-treated yogurt as a gastrointestinal transition marker. Spores of B. stearothermophilus (106 per gram of yogurt, Thermospore suspension; Difco, Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany) were mixed as quantitation markers into the yogurt containing living starter bacteria. Spores of B. stearothermophilus are resistant against digestion and are easily detectable because of their germination and growth at 60 to 65°C. Water was again given ad libitum. Ileal digesta were continuously collected as they passed the site of the fistula, usually between 3 and 10 h after feeding. Specimens were allowed to flow out into balloons which were attached to the fistulas. Balloons were changed for each sample approximately every hour.

Enumeration of bacteria.

Chyme samples were immediately weighed (in general, 5 g) after collection and were spread on tM17 or Rogosa agar. For identification of S. thermophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, 2 ml of tM17 or MRS medium was inoculated from single colonies by being toothpicked, incubated overnight, and investigated directly by PCR in a way similar to one described recently (26). Some of the cultures that were identified positively—approximately 50 isolates per subject—were additionally tested by the API 50 CHL identification system (Biomerieux, Nürtingen, Germany). The remaining parts of samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen and stored at −74°C until further use.

Calculation of survival of ingested bacteria.

The percentage of survival (S) at a special point of time was calculated on the basis of the absolute counts of PCR-confirmed colonies from the plate of the highest dilution corrected by the recovery rate of B. stearothermophilus spores: S (1 g of chyme/1 g of yogurt) = N × D × 100/(C × Y) (where N is the number of PCR-confirmed colonies, D is the dilution factor, C is the correction factor obtained by B. stearothermophilus counts, i.e., the recovery of B. stearothermophilus in 1 g of chyme in relation to the original concentration in 1 g of yogurt ingested, and Y is the count of the respective lactic acid bacterium in 1 g of yogurt). Total survival rates were obtained by summing up the survival rates of the whole amount of a series of samples collected and put into relation to the whole amount of yogurt ingested.

DNA extraction.

Chyme (0.5 g) was weighed, and total DNA was prepared according to Leenhouts et al. (23) and dissolved in 250 μl of TE buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]).

PCR.

When L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was investigated, the total reaction volume of 25 μl (50 μl when overnight cultures were directly used) contained 2.5 μl (5 μl for 50 μl) of 10× PCR buffer [200 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.55), 160 mM (NH4)2SO4, 15 mM MgCl2 · 6H2O], 0.1% (wt/vol) gelatin, 0.1% (vol/vol) Tween 20, each of the deoxynucleoside triphosphates at 0.1 mM, 1.0 mM concentrations of the appropriate primers (0.5 mM when two downstream primers in a seminested format were used, given in Table 1), and 0.5 U (1.0 U for 50 μl) of Ampli-Taq-Polymerase or Ampli-Taq-Gold (Perkin-Elmer, Roche, Weiterstadt, Germany). For the species L. delbrueckii, the cycling conditions were 10 cycles of 20 s at 92°C, 75 s at 65°C, and 40 s at 72°C. A further 35 cycles were run for 20 s at 90°C, for 50 s at 55°C, and for 30 s at 72°C. Terminal elongation was for 3 min at 72°C. The time-temperature conditions of a seminested PCR which was subspecies specific for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus were an initial denaturation of 5 min (10 min when Ampli-Taq Gold was used) at 94°C and then 35 cycles of 20 s at 90°C, 75 s at 55°C, and 40 s at 72°C followed by a terminal elongation of 3 min at 72°C. Detection of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in total DNA extracted from chyme samples was usually carried out with a slightly modified step-down PCR protocol: at the beginning, 10 additional cycles were run at an annealing temperature raised by 10 to 65°C. For S. thermophilus-specific PCR, 35 cycles consisted of 20 s at 92°C, 60 s at 58°C, and 30 s at 72°C, followed by 3 min of terminal elongation. For investigating total DNA from chyme, usually 45 cycles in a modified step-down PCR were performed (including the first 10 cycles at 66°C for the annealing temperature). One microliter of the DNA extracted or at least 0.5 μl from overnight cultures inoculated from single colonies was added to the reaction mixture.

TABLE 1.

Hybridization probes and PCR primers used in this study

| Species | Sequence (5′–3′) | Orientationa | Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L. delbrueckii | AAT TCC GTC AAC TCC TCA TC | Upstream | 715 | 25 |

| TGA TCC GCT GCT TCA TTT CA | Downstream | |||

| L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus | CCT CAT CAA CCG GGG CT | Upstream | 678 | 25 and this work |

| TGA TCC GCT GCT TCA TTT CA | Downstream | |||

| CGC CCG GGT GAA GGT G | Downstream | |||

| S. thermophilus | CAC TAT GCT CAG AAT ACA | Upstream | 968 | 27 |

| CGA ACA GCA TTG ATG TTA | Downstream |

For L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, two downstream primers in a seminested format were used.

Strain identification of S. thermophilus by phage typing.

Plates for phage typing were produced using 15 ml of tM17 medium solidified with 1.5% agar and overlaid with 3 ml of soft agar (0.6%). The soft agar had been inoculated with 0.3 ml of overnight cultures of S. thermophilus 55n or isolates from the intestine already identified by PCR. After gelling for 30 to 60 min, a few microliters of lysates of 52 typing phages (Collection of the Institute of Microbiology, Federal Dairy Research Center) was applied to the soft agar using a multipoint inoculator. Plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, and the pattern of lysis produced by the phages was compared with those of the original S. thermophilus strain 55n.

RESULTS

The first set of feeding trials was carried out on three subsequent days. On day 1 a semisynthetic diet was applied, on day 2 heat-treated yogurt was applied, and on day 3 yogurt with living starter cultures was applied. Chyme samples were collected postprandially about every hour starting 3 h after food intake. DNA was extracted from each ileal sample and was immobilized on a membrane. The hybridization obtained with a species-specific L. delbrueckii probe (data not shown) indicated high numbers of an endogenous L. delbrueckii flora in one of the minipigs. Thus, it was necessary to use at least a subspecies-specific identification system in order to distinguish L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus from the pigs' own lactis flora.

Identification of S. thermophilus, L. delbrueckii, and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus DNA by PCR of total DNA extracted from ileostomy samples.

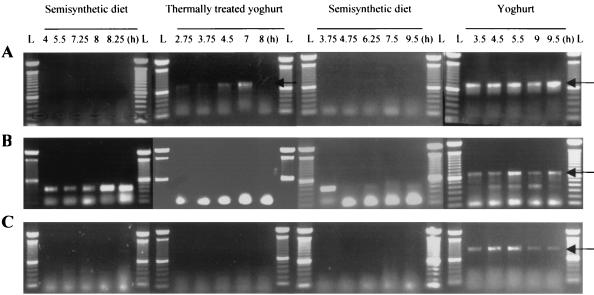

Feeding experiments were carried out with 4 pigs. Yogurt containing living starters was fed on the fourth and last day. When possible, five samples were taken between 3 and 10 h postprandially. Total DNA extracted from the digesta was investigated by PCR that was (i) species specific for L. delbrueckii (Fig. 1A; specific PCR product, 715 bp), (ii) subspecies specific for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (Fig. 1B; seminested PCR format; specific PCR product, 678 bp), and (iii) species specific for S. thermophilus (Fig. 1C; specific PCR product, 968 bp). In Fig. 1 it is shown (for one minipig) that amplification products of the expected sizes—indicating the presence of L. delbrueckii, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus, and S. thermophilus—were generated from all samples only when yogurt with living starters was applied. This was in contrast to the first and third day (application of the semisynthetic diet as control) when amplification products specific for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus were not detected. The occurrence of smaller PCR products (about 400 bp in length) in the seminested PCR format for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was most likely caused by other lactobacillus species. On the second day, when thermally treated yogurt containing inactivated starters was fed to the pigs, specific amplification was detected for L. delbrueckii but not for subspecies bulgaricus or for S. thermophilus.

FIG. 1.

Detection of L. delbrueckii (A), L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (B), and S. thermophilus (C) by PCR (715, 678, and 968 bp, respectively, as indicated by the arrows) in ileostomy samples of a Göttingen minipig after application of a semisynthetic diet, thermally treated yogurt, semisynthetic diet, and yogurt with living starter cultures on four subsequent days. Five samples were taken per day and diet, and DNA was extracted and investigated with species- or subspecies-specific PCR systems. The time of the sampling after food uptake is indicated in hours (gastrointestinal transit time) for each lane. L, a 100-bp ladder as a molecular size marker.

Detection of viable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus.

Usually five samples were taken and plated immediately after collection on Rogosa agar. An overview of the survival of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus at the terminal ileum after the intestinal passage is depicted in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Survival of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus in the chyme of 4 cannulated Göttingen miniature pigs

| Pig no. | Transition time (h) | No. of isolates testeda | No. identified as L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricusa | No. of lactobacilli (log10 CFU/g of chyme) | % B. stearothermophilus recovered (1 g of chyme per 1 g of yogurt)b | % Survival of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (1 g of chyme per 1 g of yogurt)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 795 | 3.25 | 110 | 0 | 6.1 | 0.03 | NDd |

| 4 | 111 | 48 | 7.3 | 480 | 0.8 | |

| 7.5 | 74 | 3 | 8.2 | 870 | 0.06 | |

| 8 | 123 | 0 | 8.5 | 910 | ND | |

| 9.25 | 184 | 0 | 8.7 | 210 | ND | |

| 796 | 5 | 60 | 31 | 8.4 | 1,400 | 0.7 |

| 8.25 | 62 | 8 | 7.6 | 400 | 0.13 | |

| 8.75 | 46 | 0 | 8.6 | 400 | ND | |

| 804 | 3.5 | 83 | 37 | 8.0 | 360 | 2.4 |

| 4.5 | 146 | 16 | 7.8 | 400 | 0.6 | |

| 6.5 | 151 | 0 | 7.8 | 500 | ND | |

| 9 | 100 | 41 | 7.1 | 350 | 0.2 | |

| 9.5 | 58 | 9 | 6.8 | 400 | 0.3 | |

| 805 | 3.75 | 67 | 0 | 7.0 | 50 | ND |

| 4.5 | 65 | 30 | 6.7 | 300 | 0.2 | |

| 5.5 | 30 | 13 | 6.5 | 400 | 0.05 | |

| 7 | 30 | 8 | 6.7 | 200 | 0.07 | |

| 7.75 | 22 | 0 | 5.5 | 100 | ND |

Isolates tested were taken from plates of different dilutions.

Arithmetic mean of two countings.

The survival rate of L. bulgaricus was calculated on the basis of the absolute counts of PCR-confirmed colonies identified from the plate of the highest dilution. It was corrected by the recovery rate of B. stearothermophilus. The calculation is presented in Materials and Methods.

ND, not detected.

During the intestinal passage, the numbers of quantitation marker B. stearothermophilus spores per gram increased up to 400, 500, or finally 1,400% compared to the numbers per gram of yogurt, depending on the animal and on the time of transit. This indicated a concentrating effect on the intestinal contents mainly due to water resorption. A transition time of about 3 to 4 h was observed for the first part of the yogurt to arrive at the site of the fistula.

Colonies of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus could be identified in two of five intestinal specimens of miniature pig 795, in two of three specimens of miniature pig 796, in four of five specimens of miniature pig 804, and in three of five specimens in miniature pig 805. Highest survival rates were generally observed in samples taken between 3.5 and 7 h after ingestion. They started to decrease in those samples taken after 7 to 8 h (three subjects). One exception was miniature pig 805, which still provided detectable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus isolates in samples after 9.5 h. Survival rates were estimated by direct PCR identification of colonies from plates of suitable dilution. Rates were estimated for 1 g of chyme (wet weight) in relation to 1 g of yogurt and were corrected by the recovery rate of the B. stearothermophilus spores. Highest values ranged from 0.2, 0.7, and 0.8 to 2.4% in the different animals at different transition times. The proportion of surviving L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus appeared to decrease with the duration of the time the starters remained in the stomach and small intestine.

The absolute numbers of B. stearothermophilus spores recovered were calculated from the total amount of intestinal contents actually collected. These counts corresponded to 57% (minipig 795), 70% (minipig 796), 84% (minipig 804), and 36% (minipig 805) of the total amounts of spores originally ingested.

The quantities of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus were in the order of 106 to 107 per g of chyme for all four pigs. These enumerations were corrected by the percentages of the quantitation marker recovered from each subject and put into relation to the total numbers of starters consumed. Thus, the total recovery rates obtained for the different pigs were 0.27, 0.36, 0.50, and 0.04%, respectively.

Detection of viable S. thermophilus.

Feeding experiments were repeated with two animals in order to investigate survival of S. thermophilus. Isolated colonies obtained from platings of different dilutions of intestinal contents were tested by PCR. Colonies yielding positive reactions for S. thermophilus were confirmed by phenotypic characters as described in Materials and Methods. About 10 isolates per minipig were confirmed on the strain level by phage typing. S. thermophilus colonies were identified in both individuals tested, in three of five specimens of individual 804 and in four of five specimens of individual 805 (depicted in Table 3). The magnitude was 106 to 107 per g of digesta (wet weight) in nearly all samples, with just one exception. Highest survival rates were again obtained postprandially after 3 to 6 h. They decreased rapidly after 8 h compared to those of B. stearothermophilus enumerations. The highest calculated survival rates (1 g of chyme in relation to 1 g of yogurt, corrected by the percentage of B. stearothermophilus counts detected) in the two individuals were 59 and 23%, respectively. The counts of B. stearothermophilus per gram of chyme were lower than those in yogurt, indicating that the digesta had not been concentrated, as was observed in the last trials. The total recoveries of B. stearothermophilus spores collected from all ileostomy samples were 12 and 28%, respectively. Estimations of recovery rates of total S. thermophilus related to these amounts of yogurt were calculated to be 1.2 and 2.2% for the two individuals.

TABLE 3.

Survival of S. thermophilus in the chyme of 2 cannulated Göttingen miniature pigs

| Pig no. | Transition time (h) | No. of isolates testeda | No. identified as S. thermophilusa | Amt on tM17 agar (log10 CFU/g of chyme)b | % B. stearothermophilus recovered (1 g of chyme per 1 g of yogurt) | % Survival of S. thermophilus (1 g of chyme per 1 g of yogurt)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 804 | 3.25 | 304 | 102 | 8.0 | 40 | 59 |

| 5.5 | 350 | 2 | 8.2 | 70 | 1.8 | |

| 5.75 | 219 | 4 | 8.0 | 30 | 0.8 | |

| 8 | 134 | 0 | 9.8 | 190 | NDd | |

| 9 | 115 | 0 | 9.5 | 300 | ND | |

| 805 | 6 | 310 | 32 | 8.2 | 140 | 18 |

| 6.5 | 145 | 8 | 8.4 | 60 | 23 | |

| 7 | 104 | 11 | 6.3 | 140 | 6 | |

| 8.5 | 66 | 0 | 8.0 | 230 | ND | |

| 9 | 119 | 1 | 7.9 | 210 | 0.6 |

Isolates tested were taken from plates of different dilutions.

Arithmetic mean of two countings.

Survival rate of S. thermophilus was estimated on the basis of the absolute counts of PCR-confirmed colonies identified from the plate of the highest dilution. It was corrected by the recovery rate of B. stearothermophilus. The calculation is presented in Materials and Methods.

ND, not detected.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we used minipigs as a model system for studying survival of yogurt starter bacteria during gastrointestinal passage. The suitability of an animal model and how far the results obtained with such a model can be transferred to the situation in humans depend on how close the physiology of the animal model comes to the human situation. Porcine bile employed in some in vitro assays, for example, exerts significantly more inhibitory effects against tested lactobacilli and bifidobacteria than bovine bile does. But regardless of their resistance patterns observed either in bovine or in porcine bile, all assayed bacteria were capable of growing in physiologically relevant concentrations of human bile (8). A comparison of the anatomy of the gastrointestinal tracts of humans and minipigs is depicted by Barth et al. (1). The stomach volumes of humans and minipigs (33 kg) are both approximately 1.2 to 1.5 liters, and the length of the small intestine of humans is about 4.5 m and that of minipigs ranges between 8.3 and 11.0 m. Due to their omnivorous nutritional behavior, which is similar to that of humans, minipigs appear to be suitable model systems for the in vivo screening of the survival of microorganisms. However, it has to be considered that colonization of the different compartments of the gastrointestinal tract is different. The proximal regions of the gastrointestinal tracts of pigs are lined with a stratified, squamous epithelium, and the surfaces of both secretory and nonsecretory regions of the stomach (10) are colonized by lactobacilli. In contrast, the microflora of humans is essentially confined to the large bowel (33).

Our aim was to investigate whether and in what numbers yogurt starter cultures reach the end of the small bowel and thus survive not only the acidic barrier of the stomach but also the duodenum, where bile salts and pancreatic juices are secreted. The latter are known to exhibit antimicrobial activities, too. In order to get an impression of the fate of both starters, we administered the yogurt meal with viable starters only once and did not perform a balance study with a daily delivery of living microorganisms, which results in a continuous inoculation of the gastrointestinal tract. The identification of the starter cultures after administration of yogurt with living cultures was compared with that after administration of other diets. A heat-treated yogurt contained lactose and inactivated starters, and a defined diet contained a sweetener (Lacty, a hydrated lactose) which has been described to be fermented by lactic acid bacteria (Information brochure, Purac Biochem). Therefore, it was necessary to unequivocally identify S. thermophilus and L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and to distinguish the latter one from the endogenous L. delbrueckii subsp. lactis population.

Permanent fistulas allowed us to follow the time course of the appearance of microorganisms in the ileostomy contents of the minipigs. The contents were investigated by extraction of total DNA that was tested by specific PCR systems and by recovery of live and culturable starters that were also mainly identified by PCR. Overnight cultures obtained from single colonies were inoculated and subsequently identified by PCR. The enumerations were directly used as the basis for the assessment of survival rates. We did not calculate survival on the basis of percentages of total toothpicked colonies, as we could not ensure that toothpicking had, in fact, been carried out at random. Toothpicking of single colonies from plates with colony numbers larger than 400 was not always possible. Still, the respective microorganisms in the mixed cultures could be identified by PCR. In most cases, however, the PCR results were confirmed by the classical biochemical methods. The calculated values for survival should thus be considered as rough, but also as minimum, rates at the site of the fistula.

Overall survival rates of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus were calculated for all four animals to be between 0.5 and 0.04%. These percentages were obtained from the entire amount of samples collected and did not represent the total ileal content, as the intestine was not closed by a balloon catheter. Depending on the animal and the experiment, they were related to different recovery proportions of the yogurt ingested. These proportions ranged between 84 and 36%. The main portion of living and culturable L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was found in the specimen obtained after 3 to 4 h in three animals and after 8 h in only one subject. The latter case might be due to different water resorption in the ileum and/or different emptying of the stomach.

PCR investigations carried out on total DNA extracted from the digesta throughout the whole experiment were generally in good agreement. The respective starter DNA could be detected in the total DNA after feeding of yogurt. In one minipig (796), however, S. thermophilus was detected but no L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus was detected, although colonies of the latter were identified after plating. This may be explained by technical reasons. While no specific PCR product was generated, products of ca. 400 bp were observed. These products most likely indicated a high background of other lactobacilli. The high background might have obscured the L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus identification by decreasing its detection sensitivity, e.g., through depletion of primers. Similar effects were also observed in one sample of another animal (795). In two animals (795 and 805) the very first samples did not yield any PCR amplifications of the three microorganisms, and, consistently, no colonies of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus were detected on the plates. In contrast, in the very last specimens, where no colonies of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus were found, DNA extracted from the digesta still resulted in PCR amplifications indicating the presence of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and S. thermophilus DNA. One can speculate that either the numbers of L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus colonies were below the detection level for toothpicking or the DNA extracted was still derived from dead but structurally intact microorganisms. Feeding of heat-treated yogurts resulted in detection in the digesta (of three out of four animals) of L. delbrueckii only. In the DNA extracted from thermally treated yogurt itself, S. thermophilus-specific products could still be amplified. Serial 10-fold dilutions of this DNA subjected to PCR reacted three orders of magnitude less sensitively than DNA extracted from the untreated product. This allows us to conclude that the DNA of the starters had already been degraded when the intestinal contents had reached the fistulas, since pancreatic juices are known to contain nucleases (15). The conclusion is also in accordance with data of Drouault and coworkers (7), who found that most dead Lactococcus lactis cells appear to be subject to rapid lysis.

The species L. delbrueckii detected in the digesta may belong to the endogenous flora. In contrast to the lack of growth on semisynthetic diet, they have evidently been stimulated for growth by the dairy diets. On days 1 and 3, when semisynthetic diet was applied, none of the 40 samples tested exhibited L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus-specific PCR products. One animal seemed to inhibit its own L. delbrueckii flora that was detected on day 1 but not on day 3. Pigs possess a special blind sac in the first or cardial part of the stomach (pars oesophagea) with a pH near 8.0 (15). It is known that numerous lactobacilli residing at that place originated from remains of earlier meals or were shed from the squamous epithelium where they adhere. They may occasionally be set free, thus inoculating the digesta (13, 15, 10, 33). However, in our experiment they did not grow up to detectable numbers in the following days' samples. In the chyme of two animals (795, two samples on day 1; 796, three samples on days 1 and 3), S. thermophilus DNA was found, too. Despite any contaminations that have to be considered when sensitive techniques are applied, we tend to think that S. thermophilus may have survived from the earlier feeding a few weeks before. This might also be the case for the L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus identifications in samples from another animal (805) fed heat-treated yogurt, because at the same time no S. thermophilus was detected. When the experiment was repeated with two animals in order to assess survival of S. thermophilus, the very first samples taken (until about 6 h after intake) again contributed to the main proportion of surviving microorganisms, as had already been observed in the previous experiment. Overall survival rates based on the data presented in Table 3 were calculated for 12 and 28% of the yogurt ingested (the amount of yogurt was calculated from the total amount of chyme samples obtained and the amount of spores present in the samples). Percentages of survival were 1.2 and 2.2% for the two pigs, respectively. They were at least a factor of two, and up to more than a magnitude, higher than those estimated for L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus (calculated on the same basis as for S. thermophilus). One possible explanation may be that the species S. thermophilus belongs to the chain-forming bacteria. The strain used contained on the average 8 cells per CFU in the early stationary phase (24). Therefore, inactivation of cells may be obscured by the fact that just one single surviving cell in a chain is able to generate a colony. In comparison, L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus possesses only 2 cells per CFU. A further reason could be that digesta had probably been diluted—as was deduced from the percentages of B. stearothermophilus recoveries—by drinking and/or by a reverse water transport into the lumen. One can imagine that dilution of digesta and gastric juices may have resulted in increased survival of the microorganisms.

In conclusion, PCR-based investigations of total DNA of ileostomy contents of Göttingen minipigs showed a consistent relationship between uptake of living yogurt starters and the appearance of the DNA at the terminal ileum near the entrance to the large intestine. Moreover, isolates of the subspecies L. delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and the species S. thermophilus were identified in the chyme after plating by PCR and by phenotypic methods. For the latter, species confirmation was done in part on the strain level. Estimated survival rates were higher than expected. The main proportion of surviving starters was observed in the early samples obtained between 3 and 7 h. The numbers detected (106 to 107 per g of chyme [wet weight]) are considered to be high enough for potential probiotic strains to exhibit biological effects (28).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Michael Teuber and Donna Hartley, who initiated this work years ago. We acknowledge the excellent technical assistance of Katrin Schneede and Maike Groszek. Both contributed considerably to the performing and finishing of the experiments. We are indebted to H. Fischer for excellent animal care and sampling. We thank V. Meiners, U. Krusch, and W. Bockelmann for performing the phenotypic characterizations and API 50 CHL tests, and we thank B. Fahrenholz and H. Neve for strain differentiation by phage typing.

This work was financed in part by Gervais Danone.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barth C A, Pfeuffer M, Scholtissek J. Animal models for the study of lipid metabolism, with particular reference to the Göttingen minipig. In: Kirchgäßner M, Parey Paul, editors. Advances in animal physiology and animal nutrition. Hamburg, Germany: Verlag; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bianchi-Salvadori B, Camaschella P, Bazzigaluppi E. Distribution and adherence of Lactobacillus bulgaricus in the gastroenteric tract of germ-free animals. Milk Sci Int. 1984;39:387–391. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brockmann E, Jakobsen B L, Hertel C, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Monitoring of genetically modified Lactococcus lactis in gnotobiotic and conventional rats by using antibiotic resistance markers and specific probe or primer based methods. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:203–212. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conway P L, Gorbach S L, Goldin B R. Survival of lactic acid bacteria in the human stomach and adhaesion to intestinal cells. J Dairy Sci. 1987;70:1–12. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(87)79974-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Man J C, Rogosa M, Sharpe M E. A medium for the cultivation of lactobacilli. J Appl Bacteriol. 1960;23:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drasar B S, Barrow P A. Intestinal microbiology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drouault S, Corthier G, Ehrlich S D, Renault P. Survival, physiology, and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in the digestive tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4881–4886. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4881-4886.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dunne C, Murphy L, Flynn S, O'Mahoney L, O'Halloran S, Feeney M, Morrissey D, Thornton G, Fitzgerald G, Daly C, Kiely B, Quigley E M M, O'Sullivan G C, Shanahan F, Collins K. Probiotics: from myth to reality. Demonstration of functionality in animal models of disease and in human clinical trials. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1999;76:279–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glodek P, Oldigs B. Das Göttinger Miniaturschwein. Schriftenreihe Versuchstierkunde 7. Hamburg, Germany: Paul Parey Verlag; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henriksson A, Andre L, Conway P L. Distribution of lactobacilli in the porcine gastrointestinal tract. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1995;16:55–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobsen C N, Rosenfeldt Nielsen V, Hayford A E, Møller P L, Michaelsen K F, Pæregaard A, Sandström B, Tvede M, Jacobsen M. Screening of probiotic activities of forty-seven strains of Lactobacillus spp. by in vitro techniques and evaluation of the colonization ability of five selected strains in humans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4949–4956. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.4949-4956.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johansson M-L, Molin G, Jeppsson B, Nobaek S, Ahrne S, Bengmark S. Administration of different Lactobacillus strains in fermented oatmeal soup: in vivo colonization of human intestinal mucosa and effect on the indigenous flora. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:15–20. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.15-20.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jonsson E. Proceedings on the third international seminar of the digestive physiology of the pig. 1985. Persistence in the gut of suckling piglets of a Lactobacillus strain and its influence on performance and health; pp. 288–291. Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jonsson E, Björck L, Claesson O. Survival of orally administered Lactobacillus strains in the gut of cannulated pigs. Livestock Prod Sci. 1985;12:279–285. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kidder D E, Manners M J, editors. Digestion in the pig. Bristol, United Kingdom: Scientechnica; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Klaenhammer T R. Functional activities of Lactobacillus probiotics: genetic mandate. Int Dairy J. 1998;8:497–505. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klaenhammer T R, Kullen M J. Selection and design of probiotics. Int J Food Microbiol. 1999;50:45–57. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(99)00076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klijn N, Weerkamp A H, de Vos W M. Genetic marketing of Lactococcus lactis shows its survival in the human gastrointestinal tract. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2771–2774. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.7.2771-2774.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krusch U, Neve H, Luschei B, Teuber M. Characterization of virulent bacteriophages and Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus by host specificity and electron microscopy. Kieler Milch Forsch Ber. 1987;39:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kullen M J, Amann M M, O'Shaughnessy M J, O'Sullivan D J, Busta F F, Brady L J. Differentiation of ingested and endogenous bifidobacteria by DNA fingerprinting demonstrates the survival of an unmodified strain in the gastrointestinal tract of humans. J Nutr. 1997;127:89–94. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lankaputhra W E V, Shah N P. Survival of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium spp. in the presence of acid and bile salts. Cultured Dairy Prod J. 1995;30:2–7. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Latymer E A, Low A G, Woodley S. Proceedings on the third international seminar of the digestive physiology of the pig. 1985. The effect of dietary fibre on the rate of passage through different sections of the gut in pigs; pp. 215–218. Copenhagen, Denmark. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leenhouts K J, Kok J, Venema G. Stability of integrated plasmids in the chromosome of Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:2726–2735. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.9.2726-2735.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lick S, Heller K J. Quantitation by PCR of yogurt starters in a model yogurt produced with a genetically modified Streptococcus thermophilus. Milk Sci Int. 1998;53:671–675. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lick S, Brockmann E, Heller K J. Identification of Lactobacillus delbrueckii and subspecies by hybridization probes and PCR. Syst Appl Microbiol. 2000;23:251–259. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(00)80012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lick S, Schneede K, Wittke A, Heller K J. Detection without sample processing of yogurt starters and DNA in milk products by PCR. Kieler Milch Forsch Ber. 1999;51:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lick S, Keller M, Bockelmann W, Heller K J. Rapid identification of Streptococcus thermophilus by primer-specific PCR-amplification. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:74–77. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marteau P, Rambeaud J-C. Potential of using lactic acid bacteria for therapy and immunomodulation in man. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1993;12:207–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1993.tb00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marteau P, Minekus M, Havenaar R, Huis in't Veld J H J. Survival of lactic acid bacteria in a dynamic model of the stomach and small intestine: validation and the effects of bile. J Dairy Sci. 1997;80:1031–1037. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(97)76027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pochart P, Dewit O, Desjeux O J-F, Bourlioux A. Viable starter culture, β-galactosidase activity, and lactose in duodenum after yogurt ingestion in lactase-deficient humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 1989;49:828–831. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/49.5.828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pochart P, Marteau P, Bouhnik Y, Goderel I, Bourlioux P, Rambeaud J-C. Survival of bifidobacteria ingested via fermented milk during their passage through the human intestine: an in vivo study using intestinal perfusion. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;55:78–80. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rojas M, Conway P L. Colonization by lactobacilli of piglet small intestinal mucus. J Appl Bacteriol. 1996;81:474–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1996.tb03535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tannock G. Modern methods and perspectives to assess the influence of nutritional factors, including live bacteria, on the gut microflora of man and farm animals. Bull IDF. 1992;272:32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tannock G W. Studies of the intestinal microflora: a prerequisite for the development of probiotics. Int Dairy J. 1998;8:527–533. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tannock G W, editor. Probiotics: a critical review. Norfolk, United Kingdom: Horizon Scientific Press; 1999. pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]