Abstract

Background

Efforts to synthesise existing knowledge concerning the effects of exercise interventions on obesity (i.e. changes in body weight and composition) have been made, but scientific evidence in this matter is still limited. This systematic review and meta‐analysis aims to identify and critically analyse the best available evidence regarding the use of physical exercise as a strategy to attenuate obesity through its effects on adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters in people with intellectual disability (ID).

Methods

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses guidelines, a literature search was performed using PubMed, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library through specific keywords up to July 2020. The search adhered to the population, intervention, comparison and outcome strategy. Randomised controlled trials addressing the effects of the exercise intervention on adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters (body mass index, waist circumference, waist–hip ratio, fat percentage or body weight) in children, adolescents and adults with ID were included. The methodological quality of the studies found was evaluated through the PEDro scale.

Results

A total of nine investigations with children and/or adolescents (10–19 years) and 10 investigations with adults (18–70 years) were selected, mostly experiencing mild and moderate ID. Methodological quality was fair in 13 of these publications, good in five and excellent in one. Seventeen trials reported comparable baseline and post‐intervention data for the intervention and control groups and were included in the meta‐analysis. In nine studies, the intervention group performed a cardiovascular training programme. Five papers described a combined training programme. Two trials executed whole‐body vibration training programmes, and one publication proposed balance training as the primary intervention. According to the meta‐analysis results, the reviewed studies proposed exercise modalities that, in comparison with the activities performed by the participants' in the respective control groups, did not have a greater impact on the variables assessed.

Conclusions

While physical exercise can contribute to adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters in people with mild and moderate ID, these findings show that exercise alone is not sufficient to manage obesity in this population. Multicomponent interventions appear to be the best choice when they incorporate dietary deficit, physical activity increase and behaviour change strategies. Finding the most effective modality of physical exercise can only aid weight loss interventions. Future research would benefit from comparing the effects of different exercise modalities within the framework of a multicomponent weight management intervention.

Keywords: adiposity, body mass index, exercise, fat percentage, intellectual disability, obesity

Introduction

Overweight and obesity, defined as a body mass index (BMI) over 25 or 30 kg/m2, respectively, are an excessive fat accumulation (i.e. adiposity) that is associated with poor health outcomes, including an increased risk of incidence and mortality from cancers (Parra‐Soto et al. 2021) and cardiovascular diseases (Dwivedi et al. 2020). Because of the important health burden and the economic costs to the healthcare systems worldwide derived from obesity, it is a health condition that needs treatment and, more importantly, prevention (Meldrum et al. 2017).

Excessive adiposity is largely due to a chronic imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure favouring the former. Strategies directed at reducing its prevalence should have as a priority to create a negative energy balance. To this aim, exercise promotion plays a key role (Petridou et al. 2019). Indeed, exercise can help modify several adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters linked to obesity (i.e. BMI, fat mass and waist circumference) associated with morbidity and mortality (Huxley et al. 2010). Internationally recognised guidelines support increasing physical activity (PA) as an integral part of a lifestyle intervention for weight loss, but that this must be combined with a dietary change that produces a calorie deficit and with behaviour change strategies (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2010; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014a,b).

Consequently, there are currently different systematic reviews and meta‐analyses to provide scientific evidence about the benefits of exercise on obese people and the training modalities that are more suitable for them. These pieces of research are generally focused on children (García‐Hermoso et al. 2018), adults (Kim et al. 2019) and elderly persons (Martínez‐Amat et al. 2018) with obesity or in individuals with co‐morbidities related to this condition (Ostman et al. 2017). However, research of this kind around people with intellectual disability (ID) has been sparse. This is a population often neglected, despite being at high risk of developing obesity and associated chronic health conditions (Hsieh et al. 2014).

Compared with the general population, the prevalence of obesity is much higher in persons with ID, in both adults (Doody & Doody 2012) and youth (Hinckson et al. 2013). Obesity leads to a significant contribution to the reduced life expectancy and increased health needs in these individuals (Melville et al. 2007). Therefore, there is a need for actions to reduce its prevalence. Obesity has multifactorial causes and decreased resting energy expenditure, and low PA levels have been shown to be determinant factors in those with ID (Bertapelli et al. 2016). Accordingly, physical exercise performance takes a prominent role among the lifestyle modifiable factors that can contribute to reducing obesity in this population (Spanos et al. 2013).

Efforts to synthesise existing knowledge concerning the effects of exercise interventions on obesity in people with ID have been made (Conrad & Knowlden 2020). Hamilton et al. (2007) reviewed the scientific evidence on the effectiveness of interventions for obesity in ID and indicated that PA interventions proved to be effective in the short term and should be considered an essential component of a weight loss programme. However, they specifically focused on adults with ID. In addition, most of the studies found had significant methodological problems that prevented them from extracting solid conclusions. Similarly, Maïano et al. (2014) reviewed the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions targeting changes in body weight and found that PA programmes were somewhat effective in provoking changes in body weight and composition. The authors focused on young men with ID, and they also observed serious limitations in the reviewed studies, such as small sample sizes or methodological flaws that led to inconclusive findings. Another systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) by Harris et al. (2015) indicated that PA interventions did not significantly change body weight or BMI on young adults with ID, and its effects on other measures of body composition were inconsistent. The generalisability of their findings was limited because of the heterogeneity of the sample population in age ranges and the fact that no comparison on the effects of different PA programmes could be performed. Indeed, the authors highlighted that published RCTs were inadequate to form firm conclusions. More recently, the systematic review and meta‐analysis by Kapsal et al. (2019) showed that PA generally had a positive impact on physical and psychological outcomes, but not in the case of BMI. However, certain methodological aspects such as excluding adults from their analysis and an insufficient number of RCTs that led to a considerable risk of bias limited the strength of the obtained findings. Finally, Casey & Rasmussen (2013) did review the literature on the effects of exercise on both young and adults with ID. They found that although exercise interventions appear effective at maintaining fat levels, they seemed to be particularly ineffective at reducing body fat percentage. These results were limited because the authors conducted a scoping review; thus, there was a lack of uniformity in study design and measurement, and no quality appraisal was performed. Besides, body fat was the only adiposity‐related outcome analysed.

Another important aspect to highlight is that BMI is an indirect marker of adiposity that does not consider body composition (i.e. fat and lean mass). It has been reported that anthropometric proxies for central obesity, such as waist circumference, are better predictors of health risks (Janssen et al. 2004; Schneider et al. 2010). Furthermore, it has been suggested a higher risk of mortality for high waist circumference compared with high BMI (Yusuf et al. 2005; Pischon et al. 2008; Staiano et al. 2012). The body fat percentage, a direct measure of body fat, is associated with coronary heart disease (Lavie et al. 2009), a leading cause of death in developed countries (World Health Organization 2020), and reflects better the serum lipid profile and related metabolic alterations than the anthropometric surrogates (Nagaya et al. 1999). In spite of this, no previous systematic reviews have performed a meta‐analysis comparing the effects of different types of physical exercise on these different adiposity‐related parameters in people with ID.

Altogether, it seems that no systematic review and meta‐analysis of RCTs on the effects of PA when performed as a sole intervention on obesity in both children and adults with ID and that also examines the impact of different exercise modalities has been published so far. Therefore, this review aims to answer the following research questions:

Is physical exercise an accurate strategy to attenuate obesity through its effects on adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters in people with ID?

What is the methodological quality of the studies that have addressed this topic?

Is there any physical exercise modality that should be specifically prescribed for this aim in this population?

Methods

The systematic review and meta‐analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al. 2009). The review protocol was registered at the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42020162080).

Search strategy

A systematic search of randomised controlled trials (RCT) that examined the effects of different PA interventions on adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters in people with ID until July 2019 was performed. Articles from PubMed, Scopus, SPORTDiscus, CINAHL and the Cochrane Library were identified. The search adhered to the population, intervention, comparison and outcome strategy. Only terms regarding the population and the intervention, in a combination of standardised MeSH and free‐text terms, according to recommendations from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Green 2008), were used. Consequently, the search syntax was developed as follows: (exercise OR ‘physical activity’ OR ‘physical exercise’) AND (‘intellectual disability’ OR ‘mental retardation’ OR idiocy).

Eligibility criteria and study selection

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) RCT based on exercise or PA programmes, (2) sample entirely made up of individuals with ID and (3) studies analysing the effects of the intervention on adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters (BMI, waist circumference, waist–hip ratio, fat percentage or body weight). Investigations that carried out interventions combined with other types of non‐exercise therapies or that were merely based on the promotion of PA, as well as research not published in English, French, Portuguese or Spanish in peer‐reviewed journals, were excluded.

Titles and abstracts of search results for key criteria were screened, and then full‐text potentially relevant articles for inclusion were assessed. Also, the reference lists of relevant studies for any additional suitable publications were screened. Two authors (M. A. S.‐L. and J. S.‐B.) independently assessed eligibility, with discrepancies resolved through discussion with a third author (C. A. P.).

Data extraction

One researcher (J. S.‐B.) extracted information using a predeveloped form comprising participants' characteristics, exercise programmes, outcomes and measurement tools, and main findings from the original works, and two investigators (M. A. S.‐L. and C. A. P.) confirmed the accuracy of data extraction. The data extraction procedure was not blind, as the names of the authors of the selected studies and the title of the journals in which they were published were identifiable. Missing data were obtained by contacting the study authors whenever possible.

Methodological quality assessment

The information on the quality of RCTs was retrieved directly from PEDro, the Physiotherapy Evidence Database. If a trial was not included in PEDro, two authors (M. A. S.‐L. and J. S.‐B.) appraised its quality using the PEDro scale. A third author (C. A. P.) provided advice to reach a consensus in case of disagreement. The PEDro scale rates internal study validity and the presence of replicable statistical information on a scale from 0 to 10. The suggested cut‐off points to categorise studies by quality were excellent (9–10), good (6–8), fair (4–5) and poor (≤3) (Silverman et al. 2012).

Data analysis

A meta‐analysis to measure post‐intervention changes between exercise intervention groups and control groups unassigned to any exercise programmes was used. The standardised mean differences (SMDs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to assess the change in each outcome. The SMD was computed using intervention and control group sample sizes, baseline and post‐intervention mean, and standard deviation (SD) for each selected outcome measure. To obtain the change from baseline and post‐intervention SD, the following formula was used: SDchange = √(SD2 baseline + SD2 post‐intervention) − (2 × Corr × SD2 baseline × SD2 post‐intervention), where Corr = 0.5. The value for Corr was imputed on the assumption of moderate correlation between baseline and post‐intervention measurements (Gates et al. 2013; Northey et al. 2018). Multiple publications from the same trial were identified in order to avoid double counting the same sample of participants (Senn 2009).

Both fixed‐effect and random‐effect models were applied to determine the pooled effects, considering the first if I 2 heterogeneity was <30% or the second if higher (DerSimonian & Laird 1986). Forest plots displaying SMDs and 95% CIs to compare the effects between the intervention and control groups were utilised. The SMDs were considered as significant when their 95% CIs excluded zero, while pooled SMD values were evaluated as small (≤0.2), medium (0.2–0.8) or large effects (≥0.8) (Cohen 1992).

All statistical analyses were performed using stata (version 13; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX).

Results

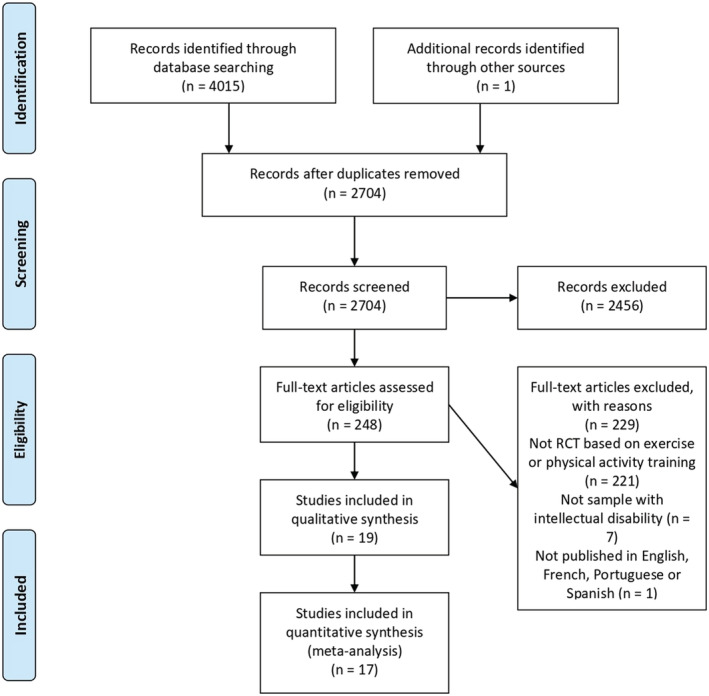

Figure 1 provides a full depiction of the systematic review process. A total of 4015 records from the database search were obtained. After excluding duplicates, 2704 records were identified. Titles and abstracts were screened, and 248 studies for full‐text assessment were retrieved. Finally, 19 RCTs met the full inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. Of the total, 17 trials reported comparable baseline and post‐intervention data for both the intervention and control groups and were included in the meta‐analysis. From these, three publications were derived from the same sample (Ordoñez et al. 2013; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the systematic review process. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Design and samples

A total of nine studies included children and/or adolescents (10–19 years), and 10 investigations included adults (18–70 years).

Fourteen publications (Rimmer et al. 2004; Calders et al. 2011; González‐Agüero et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Lin & Wuang 2012; Ordoñez et al. 2013; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Matute‐Llorente et al. 2015; Melville et al. 2015; Shields & Taylor 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Silva et al. 2017) provided information regarding ID aetiology and classified as follows: Down syndrome (DS) (n = 449), mental ill health (n = 33), autism (n = 24), epilepsy (n = 22) fragile X syndrome (n = 18), problem behaviours (n = 18), Prader–Willi syndrome (n = 6), fetal alcohol syndrome (n = 6) and hydrocephalus (n = 3).

A total of eight trials informed about the ID level of the sample, identified through specific scales (Stanford–Binet Scale and Wechsler Scale) as mild (Ordoñez et al. 2013; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Melville et al. 2015), moderate (Lin & Wuang 2012; Melville et al. 2015; Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska 2015), mild to moderate (Ozmen et al. 2007; Shields & Taylor 2015) and severe (Melville et al. 2015). When ID level was not reported, ID condition was determined through medical diagnosis (i.e. DS and Prader–Willi syndrome) (Rimmer et al. 2004; Calders et al. 2011; González‐Agüero et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014; Matute‐Llorente et al. 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Silva et al. 2017) and/or by stating participants' intelligent quotient (Calders et al. 2011; Boer et al. 2014). One paper did not report how the ID was ascertained (Kim 2017).

Methodological quality

Table 1 shows the methodological quality, which was fair in 13 RCTs (Rimmer et al. 2004; González‐Agüero et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Ordoñez et al. 2013; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Matute‐Llorente et al., 2015, 2016; Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska 2015; Kim 2017), good in five studies (Calders et al. 2011; Lin & Wuang 2012; Melville et al. 2015; Shields & Taylor 2015; Silva et al. 2017) and excellent in one publication (Boer & Moss 2016) (see Table 1 for full quality appraisal criteria). A 100% of trials accomplished item 1 (random allocation) and item 10 (point estimates and variability), while 95% and 89.5% of investigations fulfilled item 9 (between‐group comparisons) and item 3 (baseline comparability), respectively. The items 7 (adequate follow‐up), 6 (blind assessors), 8 (intention‐to‐treat analysis) and 2 (concealed allocation) had a percentage of achievement of 53%, 37%, 26% and 21%, respectively. Only one paper presented a positive result in item 4 (blind participants) (5%), and no RCT attained item 5 (blind therapists).

Table 1.

PEDro results of the methodological quality evaluation of the included studies

| Study | PEDro items | Score | Quality | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |||

| Boer & Moss (2016) | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | 9/10 | Excellent |

| Lin & Wuang (2012) | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | 7/10 | Good |

| Melville et al. (2015) | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + | + | 7/10 | Good |

| Shields & Taylor (2015) | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | 7/10 | Good |

| Silva et al. (2017) | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | 7/10 | Good |

| Calders et al. (2011) | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | 6/10 | Good |

| Ordonez et al. (2014) | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | + | + | 5/10 | Fair |

| Rimmer et al. (2004) | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | 5/10 | Fair |

| Boer et al. (2014) | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | 5/10 | Fair |

| González‐Agüero et al. (2011) | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | 5/10 | Fair |

| González‐Agüero et al. (2012) | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | 5/10 | Fair |

| Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. (2014) | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| Ordoñez et al. (2013) | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| Matute‐Llorente et al. (2015) | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| Ferry et al. (2014) | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| González‐Agüero et al. (2013) | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska (2015) | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| Ozmen et al. (2007) | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

| Kim (2017) | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | 4/10 | Fair |

1: random allocation; 2: concealed allocation; 3: baseline comparability; 4: blind participants; 5: blind therapists; 6: blind assessors; 7: adequate follow‐up; 8: intention‐to‐treat analysis; 9: between‐group comparisons; and 10: point estimates and variability.

Intervention characteristics

Table 2 displays the characteristics of the interventions.

Table 2.

Summary of characteristics and results of included studies

| Study | Sample characteristics | Intervention | Outcomes (measurement tool) | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ordonez et al. (2014) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 20/20; 20 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD; range):

IQ, score (mean; range): NR; 50–69 ID level (n; scale): mild (all; Stanford–Binet Scale) ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 10 weeks IG:

CG:

|

BMI (kg/m2) Waist circumference (anthropometric tape) Waist‐to‐hip ratio Fat mass (bioelectrical impedance analysis) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG reduced the waist circumference (94.7 ± 3.3 cm pre vs. 91.5 ± 3.1 cm post), waist‐to‐hip ratio (1.12 ± 0.001 pre vs. 1.00 ± 0.001 post) and percentage of fat mass (38.9 ± 4.0% pre vs. 35.0 ± 3.8% post) in the intra‐group analyses |

| Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. (2014) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 20/20; 20 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score (mean; range): NR; 50–69 ID level (n; scale): mild (all; Stanford–Binet Scale) ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 10 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Waist circumference (anthropometric tape) Fat mass (bioelectrical impedance analysis) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG reduced waist circumference (94.7 ± 3.3 cm pre vs. 91.5 ± 3.1 cm post) and percentage of fat mass (38.9 ± 4.0% pre vs. 35.0 ± 3.8% post) in the intra‐group analyses |

| Ordoñez et al. (2013) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 20/20; 20 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI: NR IQ, score (mean; range): NR; 50–69 ID level (n; scale): mild (all; Stanford–Binet Scale) ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 10 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Waist circumference (anthropometric tape) Waist‐to‐hip ratio Fat mass (bioelectrical impedance analysis) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG reduced waist circumference (94.7 ± 3.3 cm pre vs. 91.5 ± 3.1 cm post), waist‐to‐hip ratio (1.12 ± 0.006 pre vs. 1.00 ± 0.005 post) and percentage of fat mass (38.9 ± 4.6% pre vs. 35.0 ± 4.2% post) in the intra‐group analyses |

| Lin & Wuang (2012) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 92/92; 49 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score (mean): 52 (IG), 53 (CG) ID level (n; scale): moderate (NR; Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children) ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 6 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (specific questionnaire) BMI (kg/m2) |

IG adherence (%) (mean): 100 Significant results: the IG decreased weight (52.2 ± 7.2 kg pre vs. 49.8 ± 6.6 kg post) in comparison with the CG after the intervention |

| Matute‐Llorente et al. (2015) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 30/25; 8 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 20 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (stadiometer) BMI (kg/m2) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: NR |

| Melville et al. (2015) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 102/82; 45 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level (n; scale): mild, moderate and severe (NR; NR) ID cause (n): mental ill health (33), problem behaviours (18), epilepsy (10) |

Length: 12 weeks IG:

CG:

|

BMI (kg/m2) Waist circumference (NR) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: NR |

| Rimmer et al. (2004) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 52/52; 29 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 12 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (NR) BMI (NR) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG reduced weight after the intervention (80.5 ± 20 kg pre vs. 79.5 ± 19.9 kg post) |

| Shields & Taylor (2015) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 16/16; 8 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level (n; scale): mild to moderate (all; parent report) ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 8 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (weighting scale) Waist circumference (tape measure) |

IG adherence (%) (mean): 96 Significant results: NR |

| Silva et al. (2017) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 27/25; NR women Distribution; age (years) (range):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 8 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (segmental body composition analyser) BMI (segmental body composition analyser) Waist circumference (steel anthropometric tape) Fat mass (segmental body composition analyser) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: NR |

| Boer et al. (2014) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 54/46; 16 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score (mean): 59.2 (IG1), 57.3 (IG2), 59.1 (CG) ID level: NR ID cause (n): fragile X syndrome (NR), fetal alcohol syndrome (NR), Prader–Willi syndrome (NR), hydrocephalus (NR), pervasive developmental disorder (NR), Sotos syndrome and Steinert syndrome (NR), severe autism (NR), epilepsy or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (NR) |

Length: 15 weeks IG1:

IG2:

CG:

|

Weight (digital balance scale) BMI (kg/m2) Waist circumference (tape metre) Fat mass (bioelectrical impedance analysis) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: after the intervention, the IG2 showed a reduction in waist circumference (95.9 ± 9.6 cm pre vs. 93.4 ± 9.6 cm post) and fat mass (32.3 ± 7.0% pre vs. 31.3 ± 6.6% post) compared with the CG. Fat mass was more decreased in the IG1 (34.2 ± 6.9% pre vs. 30.4 ± 7.0% post) compared with the IG2 |

| Boer & Moss (2016) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 46/42; 17 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 12 weeks IG1:

IG2:

CG:

|

Weight (calibrated electronic scale) BMI (kg/m2) Waist circumference (flexible steel tape) Fat mass (bioelectrical impedance analysis) |

IG adherence (%) (mean): 95 (IG1), 96 (IG2) Significant results: in the IG1, weight (71.7 ± 8.4 kg pre vs. 69.4 ± 8.3 kg post) and BMI (29.0 ± 4.0 kg/m2 pre vs. 28.5 ± 4.0 kg/m2 post) were more decreased compared with the CG after intervention. These variables also decreased more in the IG2 (weight, 70.2 ± 14.6 kg pre vs. 69.2 ± 14.6 kg post; BMI, 30.6 ± 6.1 kg/m2 pre vs. 30.2 ± 6.3 kg/m2 post) compared with the CG. Weight decreased more in the IG2 compared with the CG |

| Calders et al. (2011) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 45/45; 27 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score (mean; range): 56 (IG1), 58 (IG2), 53 (CG); 45–70 ID level: NR ID cause (n): severe autism (24), fragile X syndrome (18), mild epilepsy (12), fetal alcohol syndrome (6), Prader–Willi syndrome (6), hydrocephalus (3) |

Length: 20 weeks IG1:

IG2:

CG:

|

Weight (digital balance scale) BMI (kg/m2) Waist circumference (tape measure) Fat mass (formula of Kyle) Lean mass (formula of Kyle) |

IG adherence (%) (total): 90 Significant results: NR |

| Ferry et al. (2014) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 42/42; 18 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 12 months IG:

CG:

|

Weight (balance‐beam scale) BMI (kg/m2) Fat mass (Siri equation) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG decreased the fat mass percentage (33.5 ± 5.% pre vs. 33.1 ± 5.2% post) after the intervention in the intra‐group analysis |

| González‐Agüero et al. (2013) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 30/24; 11 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 20 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (stadiometer) BMI (kg/m2) Fat mass (dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry) Lean mass (dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry) |

IG adherence (%) (mean ± SD): 69.9 ± 18.7 Significant results: the IG showed a higher per cent declination in fat mass at the upper limbs (0.78 ± 0.06 kg pre vs. 0.75 ± 0.09 kg post) than the control group |

| González‐Agüero et al. (2011) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 26/25; 13 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 21 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (stadiometer) BMI (kg/m2) Fat mass (dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry) Lean mass (dual‐energy X‐ray absorptiometry) |

IG adherence (%) (mean ± SD): 81.8 ± 9.2 Significant results: BMI decreased in the CG (22.4 ± 3.4 kg/m2 pre vs. 22.3 ± 3.2 kg/m2 post). Fat mass was also decreased in the CG in the analysis adjusted for height and Tanner stage (whole‐body fat mass, 12.4 ± 1.3 kg pre vs. 12.0 ± 1.3 kg post) |

| González‐Agüero et al. (2012) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 28/27; 13 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause (n): Down syndrome (all) |

Length: 21 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (stadiometer) BMI (kg/m2) |

IG adherence (%) (mean): 83.3 Significant results: NR |

| Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska (2015) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 34/34; 6 women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score (mean ± SD): 45.5 ± 3.39 ID level (n; scale): moderate (NR; NR) ID cause: NR |

Length: 12 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (stadiometer) BMI (kg/m2) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG decreased weight (65.8 ± 14.0 kg pre vs. 65.0 ± 13.6 kg post) and BMI (24.8 ± 6.2 kg/m2 pre vs. 24.3 ± 5.9 kg/m2 post) in the intra‐group analyses |

| Ozmen et al. (2007) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 30/30; NR women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI (kg/m2) (mean ± SD):

IQ, score: NR ID level (n; scale): mild to moderate (all; NR) ID cause: NR |

Length: 10 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Fat mass (manual skinfold callipers) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: not found |

| Kim (2017) |

Sample size (n pre/post; sex): 24/24; NR women Distribution; age (years) (mean ± SD):

BMI: NR IQ, score: NR ID level: NR ID cause: NR |

Length: 12 weeks IG:

CG:

|

Weight (bioelectrical impedance instrument) Fat mass (bioelectrical impedance instrument) |

IG adherence (%): NR Significant results: the IG decreased weight (65.6 ± 1.5 kg pre vs. 61.3 ± 1.6 kg post) and fat mass percentage (32.3 ± 1.6% pre vs. 27.5 ± 1.1% post) compared with the CG after intervention. The CG increased both weight and fat mass percentage |

1RM, one‐repetition maximum; BMI, body mass index; CG, control group; HR, heart rate; HRmax, maximum heart rate; HRpeak, peak heart rate; ID, intellectual disability; IG, intervention group; IQ, intelligence quotient; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation; V̇O₂peak, peak oxygen uptake.

In nine studies, the intervention group (IG) performed a cardiovascular training programme, and these investigations were classified as ‘cardiovascular exercise’ in the meta‐analysis (Ozmen et al. 2007; Lin & Wuang 2012; Boer et al. 2014; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Melville et al. 2015; Shields & Taylor 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Kim 2017). Two publications compared two types of exercise modalities (sprint interval training vs. continuous aerobic training); hence, two IGs were included in these trials (Boer et al. 2014; Boer & Moss 2016).

Five papers described a combined training programme. Rimmer et al. (2004) combined strength training and endurance training. González‐Agüero et al. (2012) carried out a plyometric training programme and general conditioning using press‐ups on walls, fitness bands and medicine balls. In contrast, Ferry et al. (2014) employed plyometric jumps, bodybuilding exercises, agility and speed exercises, and gymnastic routines, all in the form of dynamic games. Silva et al. (2017) implemented a combined balance and isometric strength training programme. Finally, one RCT (Calders et al. 2011), with two different IGs, conducted strength and endurance training (IG1) and endurance training (IG2).

Two studies executed whole‐body vibration training programmes (González‐Agüero et al. 2013; Matute‐Llorente et al. 2015), and one investigation proposed balance training as the primary intervention (Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska 2015). These three trials were included in the meta‐analysis as ‘other interventions’.

The duration of the training programmes ranged between 6 (Lin & Wuang 2012) and 52 weeks (1 year) (Ferry et al. 2014) in length, with sessions between 25 (González‐Agüero et al. 2011; Lin & Wuang 2012) and 60 min long (Rimmer et al. 2004; Ozmen et al. 2007; Ordoñez et al. 2013; Ferry et al. 2014; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014), and a frequency ranging from 2 (Calders et al. 2011; González‐Agüero et al. 2011; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014) to 3 days/week (Ozmen et al. 2007; Lin & Wuang 2012; González‐Agüero et al. 2013; Ordoñez et al. 2013; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Matute‐Llorente et al., 2015, 2016; Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Silva et al. 2017).

Regarding exercise intensity prescription, four publications used the participant's maximum heart rate (HRmax), ranging from 50% to 70% HRmax (Ordoñez et al. 2013; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Kim 2017); two papers prescribed exercise intensity based on maximum oxygen consumption (V̇O₂max), ranging from 50% to 80% V̇O₂max (Rimmer et al. 2004; Boer & Moss 2016); and one RCT opted for the ventilatory anaerobic threshold increasing from 90% up to 110% (Calders et al. 2011). The one‐repetition maximum was used to prescribe the intensity of the strength training programme in two studies (Rimmer et al. 2004; Calders et al. 2011).

None of the investigations with control groups assigned these to any exercise programmes during the intervention, requiring them to avoid exercise participation in 12 publications (Rimmer et al. 2004; González‐Agüero et al., 2011, 2013; Lin & Wuang 2012; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014; Ordonez et al. 2014; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Melville et al. 2015; Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Kim 2017); or to continue with the daily life activities in four trials (Ozmen et al. 2007; Calders et al. 2011; Matute‐Llorente et al. 2015; Silva et al. 2017); or to perform social activities in one paper (Shields & Taylor 2015).

Seven RCTs reported adherence, which ranged between 69.9% and 100% (Calders et al. 2011; González‐Agüero et al., 2011, 2012, 2013; Lin & Wuang 2012; Shields & Taylor 2015; Boer & Moss 2016).

Clinical significance of the results

A total of 14 studies reported body weight measurements. Of those, only three studies (Lin & Wuang 2012; Boer & Moss 2016; Kim 2017) reported an average weight loss superior to −3% (ranging between 3.2% and 6.6%), which is considered of clinical relevance (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2014b).

Results of the meta‐analysis

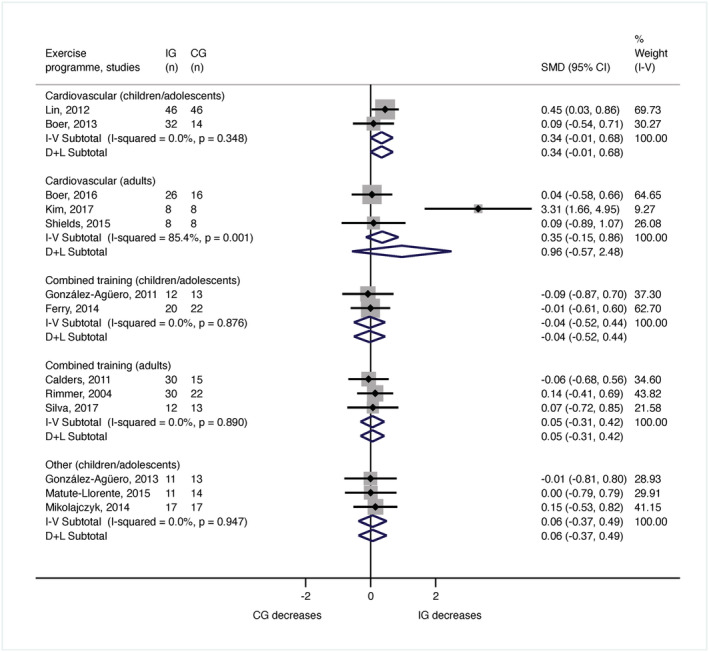

Weight

In the meta‐analysis for body weight, a total of 484 individuals were included (288 children or adolescents and 196 adults). In children and adolescents, seven studies analysed weight (González‐Agüero et al., 2011, 2013; Lin & Wuang 2012; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014; Matute‐Llorente et al. 2015; Mikolajczyk & Jankowicz‐Szymanska 2015). The meta‐analysis demonstrated no significant results for cardiovascular training (n = 138; SMD = 0.34, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.68]; I 2 = 0%), combined training (n = 67; SMD = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.52, 0.44]; I 2 = 0%) or other type of exercise (n = 83; SMD = 0.06, 95% CI [−0.37, 0.49]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 2). In adults, six investigations assessed weight (Rimmer et al. 2004; Calders et al. 2011; Shields & Taylor 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Kim 2017; Silva et al. 2017). The meta‐analysis showed no significant results for cardiovascular training (n = 74; SMD = 0.35, 95% CI [−0.15, 0.86]; I 2 = 85.4%) or combined training programmes (n = 122; SMD = 0.05, 95% CI [−0.31, 0.42]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Meta‐analysis for the body weight by age and type of exercise programme. CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; SMD, standardised mean difference. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

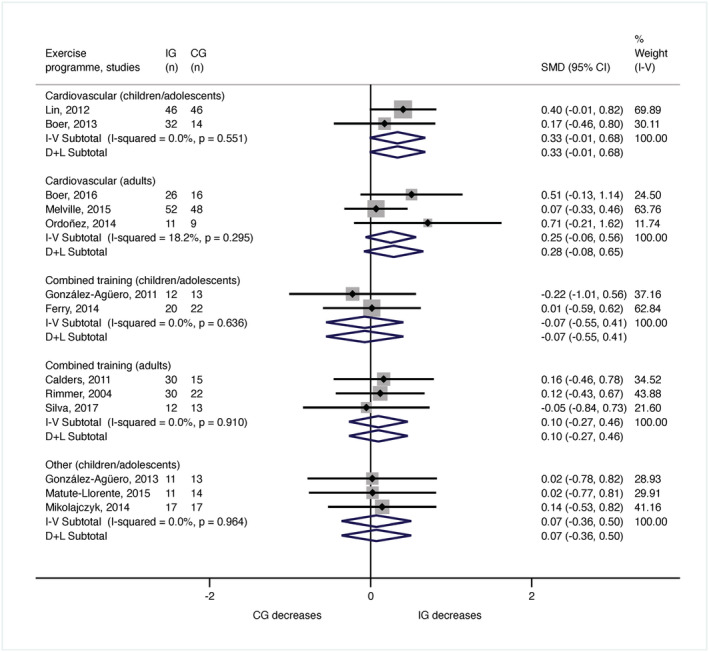

Body mass index

The meta‐analysis for BMI comprised 572 participants (288 children or adolescents and 284 adults). The meta‐analysis of the seven trials evaluating the BMI changes in children and adolescents (González‐Agüero et al. 2011, 2013; Lin & Wuang 2012; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014; Matute‐Llorente et al. 2015) revealed no significant modifications after cardiovascular training (n = 138; SDM = 0.33, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.68]; I 2 = 0%), or combined training programmes (n = 67; SDM = −0.07, 95% CI [−0.55, 0.41]; I 2 = 0%) or balance and whole‐body vibration training (n = 83; SDM = 0.07, 95% CI [−0.36, 0.50]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 3). In adults, six RCTs measured BMI (Rimmer et al. 2004; Calders et al. 2011; Ordonez et al. 2014; Melville et al. 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Silva et al. 2017). The meta‐analysis indicated no significant changes in BMI after cardiovascular training (n = 162; SDM = 0.25, 95% CI [−0.06, 0.56]; I 2 = 18.2%) or combined training programmes (n = 122; SDM = 0.10, 95% CI [−0.27, 0.46]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Meta‐analysis for the body mass index by age and type of exercise programme. CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; SMD, standardised mean difference. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

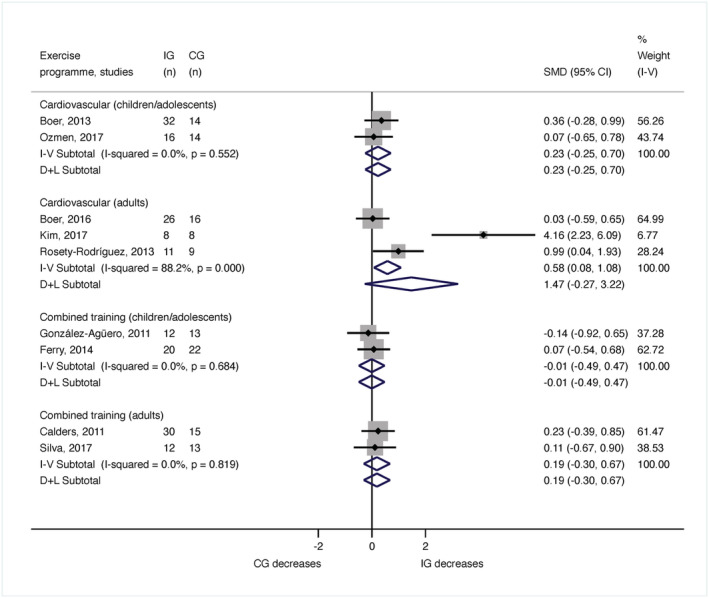

Fat mass

The meta‐analysis for fat mass incorporated 288 participants (143 children or adolescents and 145 adults). In children and adolescents, fat mass was inspected in four publications (Ozmen et al. 2007; González‐Agüero et al. 2011; Boer et al. 2014; Ferry et al. 2014), and the meta‐analysis showed no significant changes after performing cardiovascular training (n = 76; SMD = 0.23, 95% CI [−0.48, 0.46]; I 2 = 0%) or combined training programmes (n = 67; SMD = −0.01, 95% CI [−0.49, 0.47]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 4). In adults, body fat was examined in five studies (Calders et al. 2011; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Boer & Moss 2016; Kim 2017; Silva et al. 2017). The results of the meta‐analysis were non‐significant for cardiovascular training (n = 78; SMD = 0.58, 95% CI [0.08, 1.08]; I 2 = 88.2%) or combined training programmes (n = 67; SMD = 0.19, 95% CI [−0.30, 0.67]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Meta‐analysis for the body fat by age and type of exercise programme. CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; SMD, standardised mean difference. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

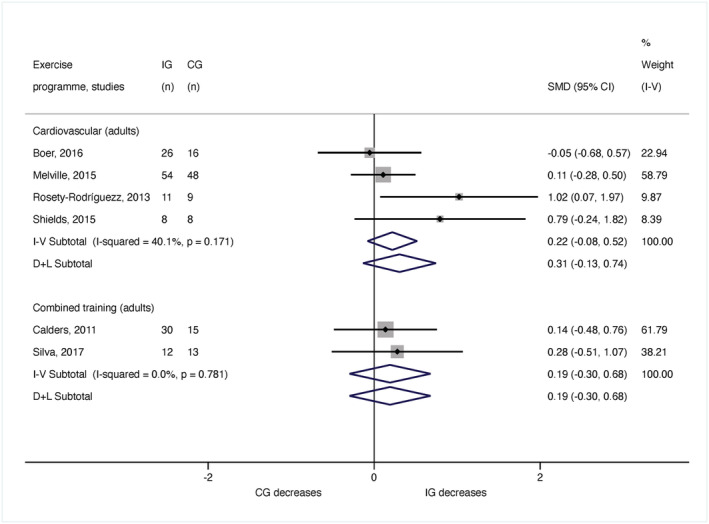

Waist circumference

A total of 250 adults from six articles (Calders et al. 2011; Rosety‐Rodriguez et al. 2014; Melville et al. 2015; Shields & Taylor 2015; Boer & Moss 2016; Silva et al. 2017) were pooled in the meta‐analysis for waist circumference. There were no significant results for cardiovascular training (n = 180; SMD = 0.22, 95% CI [−0.08, 0.52]; I 2 = 40.1%) or combined training programmes (n = 70; SMD = 0.19, 95% CI [−0.30, 0.68]; I 2 = 0%) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

Meta‐analysis for the waist circumference by age and type of exercise programme. CG, control group; CI, confidence interval; IG, intervention group; SMD, standardised mean difference. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Sensitivity analysis

The results of the sensitivity analysis, including only aerobic exercise programmes in children or adolescents and adults, exhibited significant improvements for BMI when the analysis was not stratified by age groups (Fig. S1). A trend towards improvement was generally found for all variables (weight, BMI, waist circumference and body fat, Fig. S2).

Discussion

This systematic review aimed at summarising, critically evaluating and integrating the available scientific evidence regarding the impact of exercise on a number of obesity‐related parameters related in children, adolescents and adults with ID. A considerable number of RCTs ranging from fair to excellent methodological quality were found, and the meta‐analysis included 85% of these trials. Thus, the information provided here can help guide best practices among those therapists and researchers interested in the possibilities and potential impact of prescribing exercise as a weight loss strategy for people with ID.

According to the meta‐analysis results, the reviewed studies proposed exercise modalities that, in comparison with the activities performed by the participants in the respective control groups, did not have a greater impact on the variables assessed. Given that the training programmes were generally well designed, and exercise adherence was usually high, our results would imply that exercise alone does not lead to significant anthropometric and body weight parameter changes. This finding is in line with previous observations indicating that exercise often does not produce significant morphological changes in people with ID (Hamilton et al. 2007; Spanos et al. 2013; Harris et al. 2015; Martínez‐Aldao et al. 2019). Moreover, these results reinforce the idea that interventions targeting obesity should focus on reducing energy intake rather than solely on exercise‐induced energy expenditure (Westerterp 2019).

Nevertheless, it is worth mentioning that the sensitivity analysis showed a significant trend revealing that aerobic exercise might contribute to significant changes in obesity‐related parameters. Indeed, when all the investigations that utilised this exercise modality were analysed together (without considering the participants' age), the results were statistically significant. Thus, it is plausible to think that if the reviewed trials had a greater sample size, the meta‐analysis would have detected a significant impact of aerobic exercise on anthropometric and body composition parameters. Indeed, this exercise modality proves to be central for body weight management among overweight and obese adults (Ismail et al. 2012).

The idea of which exercise modality could have a greater influence on adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters cannot be elaborated further, because only three investigations comparing different exercise modalities were found. From the obtained data, it seems that aerobic interval training might have certain advantages over continuous aerobic training, while combined endurance and muscular training do not exhibit a greater effect than aerobic exercise alone. This is supported by similar findings from previous works evaluating other populations (Monteiro et al. 2015; Wewege et al. 2017).

In this piece of research, publications including both adult and young populations mostly with mild to moderate ID were reviewed. Although ID causes were not always reported, many investigations focused on young people with DS were found. This is a fact that deserves some appreciation because this group of individuals presents a high obesity prevalence (O'Shea et al. 2018); but yet, based on previous findings (Bertapelli et al. 2016) and also to our results, exercise‐based programmes appear to be insufficient to achieve weight or fat loss.

Recent evidence has identified the difficulty of procuring an effective strategy to reduce obesity among people with ID. For instance, Harris et al. (2018) reported that current multicomponent weight management interventions were not more effective than no treatment in this population. The authors suggested that this lack of effect was due to the interventions did not adhere to clinical recommendations regarding diet, exercise and behaviour change techniques. However, they did show that multicomponent interventions that specifically included an energy‐deficient diet were effective. Similarly, Ptomey et al. (2018) demonstrated that a well‐controlled and designed intervention combining diet, PA and counselling led to significant weight changes in obese people with ID. Altogether, these results suggest that multicomponent interventions are a more effective approach than prescribing exercise alone for obesity management in people with ID.

The main strength of this review lies in its ability to build upon currently existing revisions and meta‐analysis of the RCTs regarding the impacts of exercise on anthropometric and body composition parameters in people with ID, in order to reach more robust conclusions. Nevertheless, some methodological weaknesses must be recognised. First, various reviewed papers did not inform the aetiology and severity of ID. Also, the low number of studies included in the meta‐analyses did not allow a stratified analysis by ID aetiology. Second, most of the studies had samples wholly made up of DS participants. Although this finding was somehow expected, because people with DS are one of the most at‐risk groups within the ID population for weight gain and obesity, it shows the need for further studies including different diagnoses within the ID population. Third, the different procedures to measure adiposity across the included studies limit the quality of the meta‐analysis. Fourthly, investigations with two exercise‐based programmes were not included in the meta‐analysis. Hence, proper advice about the benefits of a specific exercise modality compared with other exercise options could not be given. Fifthly, because of the reduced number of studies included per meta‐analysis, a moderator analysis using meta‐regression could not be performed, which would reduce the risk of type I error (Gordon et al. 2018). Sixthly, the analysed evidence might be incomplete because of language restrictions and because the grey literature was not reviewed. Finally, another limitation is the potential selective publication in the scientific literature (publication bias).

Conclusions

While physical exercise can contribute to adiposity‐related anthropometric parameters in people with mild and moderate ID, these findings show that exercise alone is not sufficient to manage obesity in this population. Multicomponent interventions appear to be the best choice when they incorporate dietary deficit, PA increase and behaviour change strategies. Finding the most effective modality of physical exercise can only aid weight loss interventions. There is a need for future research aimed at comparing the impacts of different exercise modalities within the framework of a multicomponent intervention.

Source of funding

The authors declare no funding for this research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Forest plot of the meta‐analysis for effects of exercise overall on adiposity‐related anthropometric variables. CG control group; CI confidence interval; EG experimental group; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure S2. Forest plot of the meta‐analysis for effects of exercise overall stratified by age group on adiposity‐related anthropometric variables. CG control group; CI confidence interval; IG intervention group, SMD standardised mean difference.

Acknowledgements

None.

Salse‐Batán, J. , Sanchez‐Lastra, M. A. , Suárez‐Iglesias, D. , and Pérez, C. A. (2022) Effects of exercise training on obesity‐related parameters in people with intellectual disabilities: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 66: 413–441. 10.1111/jir.12928.

Data availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supporting information. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Bertapelli F., Pitetti K., Agiovlasitis S. & Guerra‐Junior G. (2016) Overweight and obesity in children and adolescents with Down syndrome—prevalence, determinants, consequences, and interventions: a literature review. Research in Developmental Disabilities 57, 181–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer P.‐H., Meeus M., Terblanche E., Rombaut L., Wandele I. D., Hermans L. et al. (2014) The influence of sprint interval training on body composition, physical and metabolic fitness in adolescents and young adults with intellectual disability: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 28, 221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boer P.‐H. & Moss S. J. (2016) Effect of continuous aerobic vs. interval training on selected anthropometrical, physiological and functional parameters of adults with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 60, 322–334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calders P., Elmahgoub S., Roman de Mettelinge T., Vandenbroeck C., Dewandele I., Rombaut L. et al. (2011) Effect of combined exercise training on physical and metabolic fitness in adults with intellectual disability: a controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation 25, 1097–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey A. F. & Rasmussen R. (2013) Reduction measures and percent body fat in individuals with intellectual disabilities: a scoping review. Disability and Health Journal 6, 2–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1992) A power primer. Psychological Bulletin 112, 155–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad E. & Knowlden A. P. (2020) A systematic review of obesity interventions targeting anthropometric changes in youth with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities 24, 398–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DerSimonian R. & Laird N. (1986) Meta‐analysis in clinical trials. Controlled Clinical Trials 7, 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody C. M. & Doody O. (2012) Health promotion for people with intellectual disability and obesity. British Journal of Nursing 21, 460–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi A. K., Dubey P., Cistola D. P. & Reddy S. Y. (2020) Association between obesity and cardiovascular outcomes: updated evidence from meta‐analysis studies. Current Cardiology Reports 22, 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry B., Gavris M., Tifrea C., Serbanoiu S., Pop A.‐C., Bembea M. et al. (2014) The bone tissue of children and adolescents with Down syndrome is sensitive to mechanical stress in certain skeletal locations: a 1‐year physical training program study. Research in Developmental Disabilities 35, 2077–2084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García‐Hermoso A., Ramírez‐Vélez R., Ramírez‐Campillo R., Peterson M. D. & Martínez‐Vizcaíno V. (2018) Concurrent aerobic plus resistance exercise versus aerobic exercise alone to improve health outcomes in paediatric obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 52, 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gates N., Singh M. A. F., Sachdev P. S. & Valenzuela M. (2013) The effect of exercise training on cognitive function in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 21, 1086–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González‐Agüero A., Matute‐Llorente A., Gómez‐Cabello A., Casajus J. A. & Vicente‐Rodríguez G. (2013) Effects of whole body vibration training on body composition in adolescents with Down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities 34, 1426–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González‐Agüero A., Vicente‐Rodríguez G., Gómez‐Cabello A., Ara I., Moreno L. A. & Casajús J. A. (2011) A combined training intervention programme increases lean mass in youths with Down syndrome. Research in Developmental Disabilities 32, 2383–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González‐Agüero A., Vicente‐Rodríguez G., Gómez‐Cabello A., Ara I., Moreno L. A. & Casajús J. A. (2012) A 21‐week bone deposition promoting exercise programme increases bone mass in young people with Down syndrome. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology 54, 552–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon B. R., McDowell C. P., Hallgren M., Meyer J. D., Lyons M. & Herring M. P. (2018) Association of efficacy of resistance exercise training with depressive symptoms: meta‐analysis and meta‐regression analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Psychiatry 75, 566–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton S., Hankey C. R., Miller S., Boyle S. & Melville C. A. (2007) A review of weight loss interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities. Obesity Reviews 8, 339–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L., Hankey C., Murray H. & Melville C. (2015) The effects of physical activity interventions on preventing weight gain and the effects on body composition in young adults with intellectual disabilities: systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clinical Obesity 5, 198–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris L., Melville C., Murray H. & Hankey C. (2018) The effects of multi‐component weight management interventions on weight loss in adults with intellectual disabilities and obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials. Research in Developmental Disabilities 72, 42–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins J. P. & Green S. (2008) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Hinckson E. A., Dickinson A., Water T., Sands M. & Penman L. (2013) Physical activity, dietary habits and overall health in overweight and obese children and youth with intellectual disability or autism. Research in Developmental Disabilities 34, 1170–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh K., Rimmer J. H. & Heller T. (2014) Obesity and associated factors in adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 58, 851–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huxley R., Mendis S., Zheleznyakov E., Reddy S. & Chan J. (2010) Body mass index, waist circumference and waist:hip ratio as predictors of cardiovascular risk—a review of the literature. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 64, 16–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ismail I., Keating S. E., Baker M. K. & Johnson N. A. (2012) A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effect of aerobic vs. resistance exercise training on visceral fat. Obesity Reviews 13, 68–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen I., Katzmarzyk P. T. & Ross R. (2004) Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity‐related health risk. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 79, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsal N. J., Dicke T., Morin A. J. S., Vasconcellos D., Maïano C., Lee J. et al. (2019) Effects of physical activity on the physical and psychosocial health of youth with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 16, 1187–1195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. B., Kim K., Kim C., Kang S.‐J., Kim H. J., Yoon S. et al. (2019) Effects of exercise on the body composition and lipid profile of individuals with obesity: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome 28, 278–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S.‐S. (2017) Effects of endurance exercise and half‐bath on body composition, cardiorespiratory system, and arterial pulse wave velocity in men with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 29, 1216–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavie C. J., Milani R. V. & Ventura H. O. (2009) Obesity and cardiovascular disease: risk factor, paradox, and impact of weight loss. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 53, 1925–1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H.‐C. & Wuang Y.‐P. (2012) Strength and agility training in adolescents with Down syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Research in Developmental Disabilities 33, 2236–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maïano C., Normand C. L., Aimé A. & Bégarie J. O. (2014) Lifestyle interventions targeting changes in body weight and composition among youth with an intellectual disability: a systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities 35, 1914–1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐Aldao D., Martínez‐Lemos I., Bouzas‐Rico S. & Ayán‐Pérez C. (2019) Feasibility of a dance and exercise with music programme on adults with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 63, 519–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martínez‐Amat A., Aibar‐Almazán A., Fábrega‐Cuadros R., Cruz‐Díaz D., Jiménez‐García J. D., Pérez‐López F. R. et al. (2018) Exercise alone or combined with dietary supplements for sarcopenic obesity in community‐dwelling older people: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Maturitas 110, 92–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute‐Llorente A., González‐Agüero A., Gómez‐Cabello A., Olmedillas H., Vicente‐Rodríguez G. & Casajús J. A. (2015) Effect of whole body vibration training on bone mineral density and bone quality in adolescents with Down syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporosis International 26, 2449–2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matute‐Llorente A., González‐Agüero A., Gómez‐Cabello A., Tous‐Fajardo J., Vicente‐Rodríguez G. & Casajús J. A. (2016) Effect of whole‐body vibration training on bone mass in adolescents with and without Down syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Osteoporosis International 27, 181–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meldrum D. R., Morris M. A. & Gambone J. C. (2017) Obesity pandemic: causes, consequences, and solutions—but do we have the will? Fertility and Sterility 107, 833–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville C. A., Hamilton S., Hankey C. R., Miller S. & Boyle S. (2007) The prevalence and determinants of obesity in adults with intellectual disabilities. Obesity Reviews 8, 223–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melville C. A., Mitchell F., Stalker K., Matthews L., McConnachie A., Murray H. M. et al. (2015) Effectiveness of a walking programme to support adults with intellectual disabilities to increase physical activity: walk well cluster‐randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 12, 125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolajczyk E. & Jankowicz‐Szymanska A. (2015) The effect of dual‐task functional exercises on postural balance in adolescents with intellectual disability—a preliminary report. Disability and Rehabilitation 37, 1484–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G. & PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6, e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro P. A., Chen K. Y., Lira F. S., Saraiva B. T. C., Antunes B. M. M., Campos E. Z. et al. (2015) Concurrent and aerobic exercise training promote similar benefits in body composition and metabolic profiles in obese adolescents. Lipids in Health and Disease 14, 153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagaya T., Yoshida H., Takahashi H., Matsuda Y. & Kawai M. (1999) Body mass index (weight/height2) or percentage body fat by bioelectrical impedance analysis: which variable better reflects serum lipid profile? International Journal of Obesity and Related Metabolic Disorders 23, 771–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014a) Obesity: Identification, Assessment and Management . Available at: www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189 [PubMed]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014b) Weight Management: Lifestyle Services for Overweight or Obese Adults . NICE Guidance. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph53/chapter/1‐Recommendations#recommendation‐13‐ensure‐contracts‐for‐lifestyle‐weight‐management‐programmes‐include‐specific

- Northey J. M., Cherbuin N., Pumpa K. L., Smee D. J. & Rattray B. (2018) Exercise interventions for cognitive function in adults older than 50: a systematic review with meta‐analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine 52, 154–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez F. J., Fornieles‐Gonzalez G., Camacho A., Rosety M. A., Rosety I., Diaz A. J. et al. (2013) Anti‐inflammatory effect of exercise, via reduced leptin levels, in obese women with Down syndrome. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 23, 239–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ordonez F. J., Rosety M. A., Camacho A., Rosety I., Diaz A. J., Fornieles G. et al. (2014) Aerobic training improved low‐grade inflammation in obese women with intellectual disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 58, 583–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Shea M., O'Shea C., Gibson L., Leo J. & Carty C. (2018) The prevalence of obesity in children and young people with Down syndrome. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 31, 1225–1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ostman C., Smart N. A., Morcos D., Duller A., Ridley W. & Jewiss D. (2017) The effect of exercise training on clinical outcomes in patients with the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Cardiovascular Diabetology 16, 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozmen T., Ryildirim N. U., Yuktasir B. & Beets M. W. (2007) Effects of school‐based cardiovascular‐fitness training in children with mental retardation. Pediatric Exercise Science 19, 171–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parra‐Soto S., Cowley E. S., Rezende L. F. M., Ferreccio C., Mathers J. C., Pell J. P. et al. (2021) Associations of six adiposity‐related markers with incidence and mortality from 24 cancers—findings from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. BMC Medicine 19, 1–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petridou A., Siopi A. & Mougios V. (2019) Exercise in the management of obesity. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 92, 163–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pischon T., Boeing H., Hoffmann K., Bergmann M., Schulze M. B., Overvad K. et al. (2008) General and abdominal adiposity and risk of death in Europe. The New England Journal of Medicine 359, 2105–2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ptomey L. T., Steger F. L., Lee J., Sullivan D. K., Goetz J. R., Honas J. J. et al. (2018) Changes in energy intake and diet quality during an 18‐month weight‐management randomized controlled trial in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics 118, 1087–1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimmer J. H., Heller T., Wang E. & Valerio I. (2004) Improvements in physical fitness in adults with Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation 109, 165–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosety‐Rodriguez M., Diaz A. J., Rosety I., Rosety M. A., Camacho A., Fornieles G. et al. (2014) Exercise reduced inflammation: but for how long after training? Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 58, 874–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider H. J., Friedrich N., Klotsche J., Pieper L., Nauck M., John U. et al. (2010) The predictive value of different measures of obesity for incident cardiovascular events and mortality. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 95, 1777–1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (2010) Management of Obesity: A National Clinical Guideline . Available at: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign115.pdf

- Senn S. J. (2009) Overstating the evidence—double counting in meta‐analysis and related problems. BMC Medical Research Methodology 9, 10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields N. & Taylor N. F. (2015) The feasibility of a physical activity program for young adults with Down syndrome: a phase II randomised controlled trial. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability 40, 115–125. [Google Scholar]

- Silva V., Campos C., Sá A., Cavadas M., Pinto J., Simões P. et al. (2017) Wii‐based exercise program to improve physical fitness, motor proficiency and functional mobility in adults with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 61, 755–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman S. R., Schertz L. A., Yuen H. K., Lowman J. D. & Bickel C. S. (2012) Systematic review of the methodological quality and outcome measures utilized in exercise interventions for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 50, 718–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanos D., Melville C. A. & Hankey C. R. (2013) Weight management interventions in adults with intellectual disabilities and obesity: a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition Journal 12, 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiano A. E., Reeder B. A., Elliott S., Joffres M. R., Pahwa P., Kirkland S. A. et al. (2012) Body mass index versus waist circumference as predictors of mortality in Canadian adults. International Journal of Obesity 36, 1450–1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerterp K. R. (2019) Physical activity and body‐weight regulation. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 110, 791–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wewege M., van den Berg R., Ward R. E. & Keech A. (2017) The effects of high‐intensity interval training vs. moderate‐intensity continuous training on body composition in overweight and obese adults: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews 18, 635–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020) The Top 10 Causes of Death . Available at: http://www.who.int/news‐room/fact‐sheets/detail/the‐top‐10‐causes‐of‐death

- Yusuf S., Hawken S., Ounpuu S., Bautista L., Franzosi M. G., Commerford P. et al. (2005) Obesity and the risk of myocardial infarction in 27 000 participants from 52 countries: a case‐control study. Lancet 366, 1640–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Forest plot of the meta‐analysis for effects of exercise overall on adiposity‐related anthropometric variables. CG control group; CI confidence interval; EG experimental group; SMD, standardised mean difference.

Figure S2. Forest plot of the meta‐analysis for effects of exercise overall stratified by age group on adiposity‐related anthropometric variables. CG control group; CI confidence interval; IG intervention group, SMD standardised mean difference.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supporting information. Raw data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.