Abstract

Background

Risankizumab has demonstrated durable, high rates of efficacy in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis as assessed by the achievement of relative Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) improvement and Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) 0/1.

Objectives

The aim of this post hoc analysis is to assess the achievement of absolute PASI thresholds and related improvements in health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis treated with (i) risankizumab compared with ustekinumab, and (ii) long‐term (>52 weeks to 172 weeks) risankizumab.

Methods

Data from patients randomised to 150 mg risankizumab or 45 or 90 mg ustekinumab in replicate randomised controlled trials UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 were analysed for the achievement of absolute PASI thresholds PASI ≤ 3, PASI ≤ 1, and PASI = 0, time to achieve these thresholds, and combined PASI and DLQI endpoints. Data from pat ients initially randomised to risankizumab who continued on risankizumab in the open‐label extension study LIMMitless were analysed for the achievement of absolute PASI levels, mean DLQI scores, and DLQI 0/1.

Results

Significantly greater proportions of patients treated with risankizumab compared with ustekinumab achieved PASI ≤ 3, PASI ≤ 1, and PASI = 0, as well as combined endpoints for absolute PASI and DLQI [(PASI ≤ 3 and DLQI ≤ 5) or (PASI ≤ 1 and DLQI 0/1)]. The median time to first achieve PASI ≤ 3, PASI ≤ 1, and PASI = 0 was significantly lower for risankizumab‐treated patients compared with ustekinumab‐treated patients. Among patients treated with long‐term risankizumab, more than 90% achieved PASI ≤ 3 though week 172 and more than 80% achieved DLQI 0/1. Low absolute PASI scores corresponded with low mean absolute DLQI scores through week 172 of continuous risankizumab treatment.

Conclusions

Risankizumab treatment demonstrated high rates of rapid and durable efficacy as measured by absolute PASI thresholds and improvements in patient HRQoL.

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune‐mediated, systemic inflammatory disease with prominent skin manifestations estimated to affect between 1% and 4% of the population in developed countries, approximately 100 million people worldwide. 1 , 2 , 3 Approximately 20% of patients are estimated to have a more severe form of psoriasis, affecting ≥10% of body surface area. 4 Psoriasis has a profound negative impact on patients’ quality of life and increases the risk for early mortality and prevalence of comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and depression. 5 , 6 , 7 Complete or nearly complete clearance is now achievable with available biologic treatments targeting various cytokines involved in disease pathogenesis, namely interleukin (IL)‐17, IL‐23, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)‐α 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ; however, the durability of response with many biologics is limited in clinical practice after 1–2 years due to loss of treatment effect over time. 12 , 13

IL‐23, a key regulatory cytokine, is essential for pathogenic T helper 17 (Th17) cell differentiation, activation, and survival. 14 In psoriasis, the IL‐23/Th17 pathway is activated, driving cutaneous plaque formation and chronic inflammation. 14 , 15 Recent clinical trials demonstrated that selective inhibition of IL‐23 through antibodies targeting the p19 subunit produced high and durable efficacy associated with reductions in inflammatory cytokine expression in skin. 8 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 Specific inhibition of IL‐23 may offer additional safety benefits over biologics that target IL‐17 by preserving the function of IL‐23–independent, IL‐17–producing cells that are involved in mucocutaneous defence and barrier tissue integrity. 20

Risankizumab is a humanised immunoglobulin G1 monoclonal antibody that binds with high affinity to the p19 subunit and specifically inhibits IL‐23. 21 Phase 3 clinical trials in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis have demonstrated superior efficacy for risankizumab compared with placebo, adalimumab, ustekinumab, and secukinumab at week 16, which was sustained through weeks 44 (compared with adalimumab) and 52 (compared with ustekinumab and secukinumab). 18 , 19 , 22

Relative improvements in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI; eg, PASI 75 or PASI 90), often used for assessing the benefits of psoriasis therapies in clinical trials, have some limitations. Notably, calculation of relative PASI requires assessment of baseline disease status, which may not be available in routine clinical practice or other clinical settings in which patients may switch from other treatments without a washout period. Additionally, patients with high baseline PASI scores (PASI > 20) who achieve PASI 75 or PASI 90 may still have significant levels of persistent psoriasis. Conversely, patients with lower absolute PASI at baseline, such as those switching from one treatment to another, may have difficulty achieving PASI 90, given the known lack of precision in the PASI at lower levels of disease activity. Recent treat‐to‐target guidelines from the National Psoriasis Foundation recommend basing decisions to change therapy primarily on level of skin involvement and not on percent PASI reduction. 23 Absolute PASI provides an additional tool to standardise measures of efficacy and may provide more clinically relevant information when evaluating the efficacy of biologics during the treatment maintenance phase, when changing therapy, and when baseline PASI information is lacking. Low absolute PASI values have been correlated with improvements in patient health‐related quality of life (HRQoL), 24 , 25 , 26 and treatment goals defined by absolute PASI targets have enabled a more standardised quality of care. Additionally, patients who achieve clear or almost‐clear skin are more likely to report that psoriasis has no impact on their HRQoL and other measures of symptoms. 27 , 28 In this report, we assess achievement of absolute PASI thresholds and improvements in HRQoL in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis treated with risankizumab compared to ustekinumab using integrated data from 2 pivotal phase 3 randomised controlled trials (RCTs), UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2, and assess the long‐term (>52 to 172 weeks) efficacy of risankizumab using data from the ongoing open‐label extension (OLE) study LIMMitless.

Methods

Study design and patients

This is a post hoc integrated analysis of the UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 replicate phase 3, randomised, double‐blinded, placebo‐ and active comparator–controlled studies, comparing risankizumab and ustekinumab efficacy and safety, with long‐term risankizumab data analysis from the LIMMitless ongoing, phase 3, single‐arm, international, multicentre, OLE study. The eligibility criteria for UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 have been previously published. 19 Briefly, the studies included adult patients (≥18 years) with stable (≥6 months) moderate‐to‐severe chronic plaque psoriasis (with or without psoriatic arthritis) with body surface area (BSA) involvement ≥10%, PASI ≥ 12, and static Physician’s Global Assessment (sPGA) ≥ 3. PASI was collected with 1 digit after the decimal, while BSA was up to integer in percentage scale.

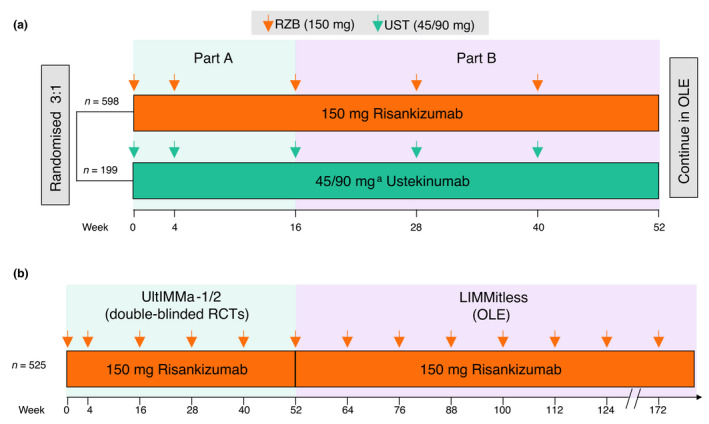

The comparator analysis is focused on patients initially randomised to risankizumab or ustekinumab, receiving either 150 mg risankizumab or 45/90 mg ustekinumab based on weight per label (45 mg for patients with body weight ≤100 kg or 90 mg for patients with body weight >100 kg) subcutaneously at weeks 0 and 4 and then every 12 weeks (Q12W) through week 40 (Fig. 1a). All patients who completed UltIMMa‐1 or UltIMMa‐2 and were candidates for long‐term risankizumab treatment were eligible to enrol in the ongoing, phase 3, single‐arm, international, multicentre, OLE study LIMMitless (NCT03047395). There was no requirement for response thresholds to enrol into LIMMitless, and additional inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table S1 (Supporting Information). Upon enrollment in LIMMitless, patients receive 150 mg open‐label risankizumab subcutaneously Q12W with no washout period (Fig. 1b). The long‐term analysis, herein, is focused on patients initially randomised to risankizumab in UltIMMa‐1 or UltIMMa‐2 who elected to enrol in LIMMitless and continued to receive risankizumab as 150 mg open‐label Q12W.

Figure 1.

Study design. Study design for (a) UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 post hoc analysis, full study design included a placebo arm 19 and (b) LIMMitless; OLE, open‐label extension; RCT, randomised controlled trial; RZB, risankizumab; UST, ustekinumab. aPatients weighing ≤100 kg received 45 mg UST, while patients weighing >100 kg received 90 mg UST, per label instructions.

The studies were conducted in accordance with the protocol, International Council for Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Pharmaceuticals for Human Use guidelines, applicable local regulations and Good Clinical Practice guidelines governing clinical study conduct, and ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. All study‐related documents (including study protocols) were approved by an institutional review board or independent ethics committee at each study site; all patients provided written informed consent prior to study participation.

Outcomes

In this analysis, efficacy was assessed using measures of disease activity, including the proportion of patients achieving absolute PASI ≤ 3, PASI ≤ 1, and PASI = 0 through 52 weeks in UltIMMa‐1 or UltIMMa‐2 and through 172 weeks in LIMMitless (interim snapshot on March 26, 2020). To gain further insight into the distribution of responses at each time point, absolute PASI response data were regrouped into 6 non‐overlapping categories representing the proportion of patients reaching absolute PASI > 10, >5–10, >3–5, >1–3, >0–1, and =0, assessed through week 52 in UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 and through week 172 in LIMMitless. Time to achievement of absolute PASI thresholds (PASI ≤ 3, PASI ≤ 1, and PASI = 0) was assessed for patients treated with either risankizumab or ustekinumab in UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2. To understand the relationship between absolute PASI and HRQoL, 2 distinct combined endpoints were assessed as (i) achievement of (PASI ≤ 3 and Dermatology Life Quality Index [DLQI] ≤ 5) or (ii) achievement of (PASI ≤ 1 and DLQI 0/1) at weeks 16 and 52 in UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2. For the long‐term risankizumab population, mean absolute DLQI scores and proportion of patients achieving DLQI 0/1 were assessed every 24 weeks starting after week 52 through week 172 in LIMMitless. Safety was assessed as treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) for all patients receiving at least 1 dose of study medication.

Statistical analysis

For the UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 integrated post hoc analysis, patients with missing efficacy data for categorical variables were handled by non‐responder imputation (NRI) and for continuous variables with last observation carried forward (LOCF). Categorical variables were tested using the Cochran‐Mantel‐Haenszel risk difference estimate. For the LIMMitless post hoc analysis, missing efficacy data were imputed using modified NRI (mNRI; non‐response is imputed only for treatment failures, defined as patients who have worsening of psoriasis, then mixed‐effect model was used on the imputed dataset), LOCF, and observed cases (OC). Nominal P values are reported. All statistical analyses were conducted using SAS® version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA) or higher.

Results

In UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2, 797 patients were randomised to risankizumab (150 mg, n = 598) or ustekinumab (45 or 90 mg, n = 199); efficacy and safety for these pivotal trials have been previously published. 19 Among patients initially randomised to risankizumab, 525 enrolled in LIMMitless and continued to receive open‐label 150 mg risankizumab (Fig. S1, Supporting Information). At the time of this interim analysis, 465/525 patients receiving long‐term, continuous risankizumab had completed 172 weeks of treatment in LIMMitless. Baseline patient demographics and disease characteristics upon entry to UltIMMa‐1 and UtIMMa‐2 were generally balanced between treatment groups and were mostly consistent with those of recent trials in patients with psoriasis (Table 1). Reasons for discontinuation in UltIMMa‐1, UltIMMa‐2, and LIMMitless are reported in Fig. S1 (Supporting Information).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics & disease characteristics

| Characteristic | UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 | LIMMitless | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

UST n = 199 |

RZB n = 598 |

RZB n = 525 |

|

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 47.5 (14.1) | 47.2 (13.6) | 47.7 (13.32) |

| Male, n (%) | 136 (68.3) | 415 (69.4) | 364 (69.3) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 165 (82.9) | 455 (76.1) | 393 (74.9) |

| Weight, kg, mean (SD) | 90.4 (22.2) | 90.0 (22.4) | 89.9 (22.13) |

| Weight >100 kg, n (%)† | 56 (28.1) | 169 (28.3) | 149 (28.4) |

| BMI, kg/m2, mean (SD) | 30.4 (6.8) | 30.5 (7.0) | 30.4 (6.83) |

| PASI, mean (SD) | 19.2 (6.4) | 20.6 (7.7) | 20.4 (7.63) |

| sPGA of severe, n (%) | 33 (16.6) | 114 (19.1) | 101 (19.2) |

| BSA, %, mean (SD) | 23.0 (13.6) | 26.2 (15.6) | 25.8 (15.41) |

| Psoriatic arthritis status, n (%)† | 50 (25.1) | 159 (26.6) | 143 (27.2) |

| Any prior biologic therapy, n (%) | 73 (36.7) | 222 (37.1) | 196 (37.3) |

| Prior TNFi, n (%)† | 43 (21.6) | 134 (22.4) | 119 (22.7) |

| Prior IL‐17i, n (%) | 35 (17.6) | 111 (18.6) | 95 (18.1) |

BMI, body mass index; BSA, body surface area; IL‐17i, interleukin‐17 inhibitor; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RZB, risankizumab; SD, standard deviation; sPGA, static Physician’s Global Assessment; TNFi, tumor necrosis factor inhibitor; UST, ustekinumab.

Randomisation was stratified by weight (≤100 kg or >100 kg) and prior TNFi exposure. ‡Diagnosed or suspected psoriatic arthritis.

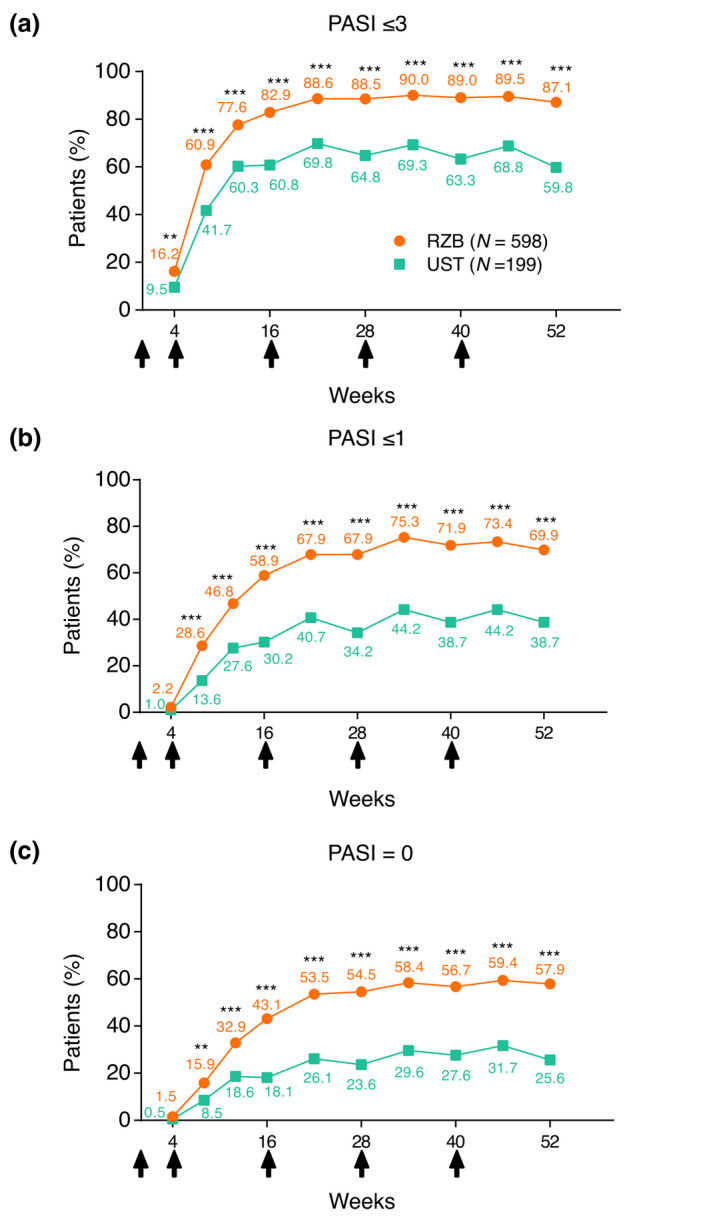

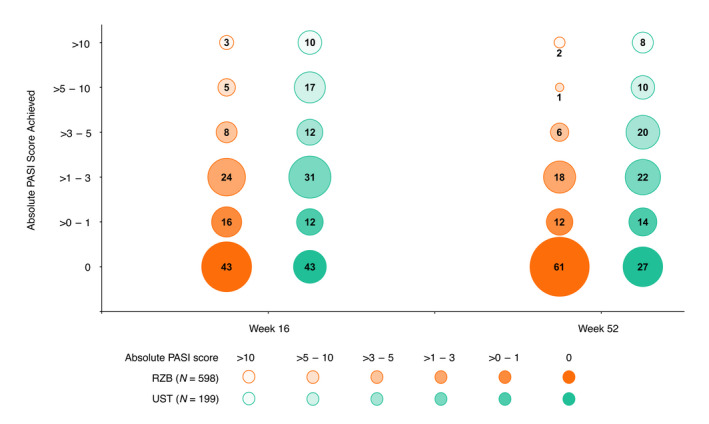

Efficacy of risankizumab versus ustekinumab was assessed as the achievement of absolute PASI thresholds for patients who participated in UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2. Significantly greater proportions of patients receiving risankizumab compared with those receiving ustekinumab achieved PASI ≤ 3 as early as week 4 (P < 0.01), and this difference was increased and maintained through week 52 (P < 0.001; Fig. 2a). Similarly, greater proportions of risankizumab‐treated patients achieved PASI ≤ 1 (Fig. 2b) and PASI = 0 (Fig. 2c) compared with ustekinumab‐treated patients as early as week 8 and through week 52 of treatment. Among risankizumab‐treated patients, 87.1%, 69.9%, and 57.9% achieved PASI ≤ 3, ≤1, and =0 at week 52, respectively (Fig. 2). Regrouping absolute PASI response data into the achievement of absolute PASI tiers allows for visualisation of individual improvement. Typical to the enrollment criteria of clinical trials, all patients entered UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 with absolute PASI ≥ 12. Greater proportions of risankizumab‐treated patients achieved lower absolute PASI thresholds (PASI ≤ 5, PASI ≤ 3, PASI ≤ 1, and PASI = 0) than ustekinumab‐treated patients as early as week 4 and through week 52 (Fig. 3 and Video S1, Supporting Information). The rapidity of absolute PASI response was also assessed. The median time to achieve PASI ≤ 3 (58 vs 84 days), PASI ≤ 1 (94 vs 199 days), and PASI = 0 (148 vs 370 days) was lower for risankizumab‐treated patients than for ustekinumab‐treated patients, respectively, P < 0.001 for all (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Achievement of absolute PASI thresholds over time. Percentage of patients achieving absolute PASI scores of (a) ≤3, (b) ≤1, (c) or = 0 over time for patients receiving risankizumab or ustekinumab (NRI). NRI, non‐responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RZB, risankizumab; UST, ustekinumab. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001 compared to UST. Arrows indicate timing of doses for patients with either 150 mg RZB or weight‐based UST (45/90 mg UST).

Figure 3.

Percentage of patients within absolute PASI score categories at weeks 16 and 52 (LOCF). The size of each circle represents the proportion of patients falling into each absolute PASI category; the whole numbers indicate that proportion rounded to the nearest percentage imputed as LOCF. All patients started the trials with a PASI >10 since 1 of the inclusion criteria required patients to have a baseline PASI ≥ 12. LOCF, last observation carried forward; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RZB, risankizumab; UST, ustekinumab.

Table 2.

Time to achievement of absolute PASI thresholds (days)

| Absolute PASI | RZB (n = 598) | UST (n = 199) |

RZB vs UST P‐value of log‐rank Test, hazard ratio (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Median Days |

Percentile | Median Days | Percentile | ||||

| 25th | 75th | 25th | 75th | ||||

| PASI ≤ 3 | 58 | 56 | 85 | 84 | 57 | 153 |

<0.001 1.664 (1.397, 1.982) |

| PASI ≤ 1 | 94 | 60 | 159 | 199 | 86 | N/A |

<0.001 2.273 (1.864, 2.773) |

| PASI = 0 | 148 | 85 | 280 | 370 | 145 | N/A |

<0.001 2.400 (1.926, 2.991) |

PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RZB, risankizumab; UST, ustekinumab.

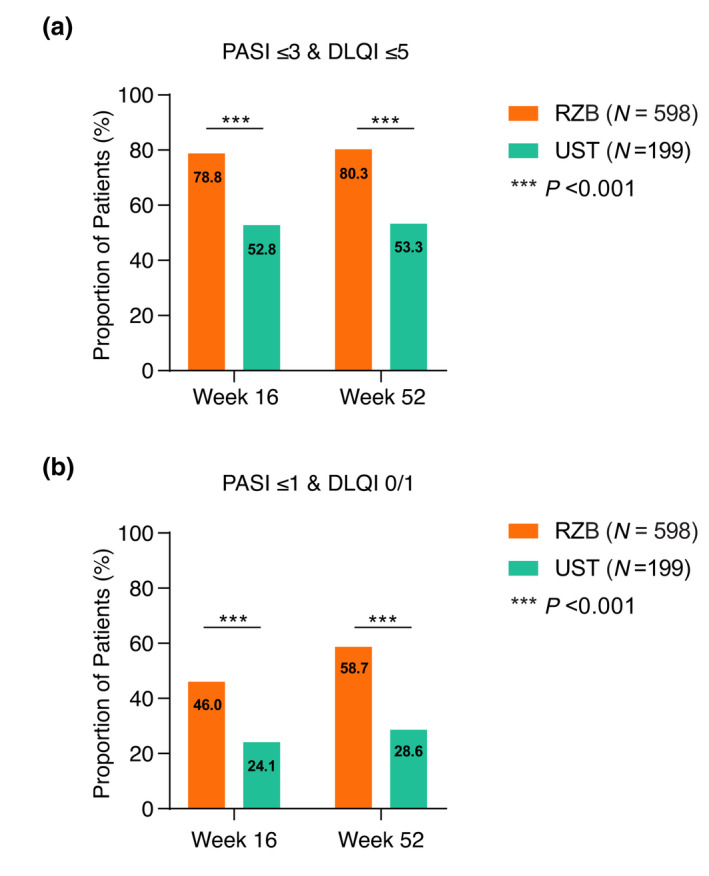

To better understand the level of HRQoL improvement that patients experience with skin clearance, we assessed the achievement of combined PASI and DLQI targets for patients treated with risankizumab compared to those treated with ustekinumab. A significantly greater proportion of risankizumab‐treated patients achieved combined absolute PASI ≤ 3 and DLQI ≤ 5 at week 16 and 52 compared with ustekinumab patients (Fig. 4a); the adjusted difference between the 2 treatments was 26.2% [18.6, 33.8 (95% CI)] and 27.2% [19.8, 34.6 (95% CI)] for week 16 and week 52, respectively. Similarly, combined absolute PASI ≤ 1 and DLQI 0/1 was achieved by a greater proportion of risankizumab‐treated patients than ustekinumab‐treated patients (Fig. 4b), with adjusted differences between the 2 treatments of 22.1% [15.2, 29.1 (95% CI)] and 30.3% [23.1, 37.6 (95% CI)] for week 16 and week 52, respectively.

Figure 4.

Treat‐to‐target combined analysis. Proportion of patients achieving combined treatment targets (a) PASI ≤ 3 and DLQI ≤ 5 and (b) PASI ≤ 1 and DLQI 0/1, at weeks 16 and 52 (NRI). Numbers indicate the percentage of patients in each group. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; NRI, non‐responder imputation; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RZB, risankizumab; UST, ustekinumab. ***P < 0.001.

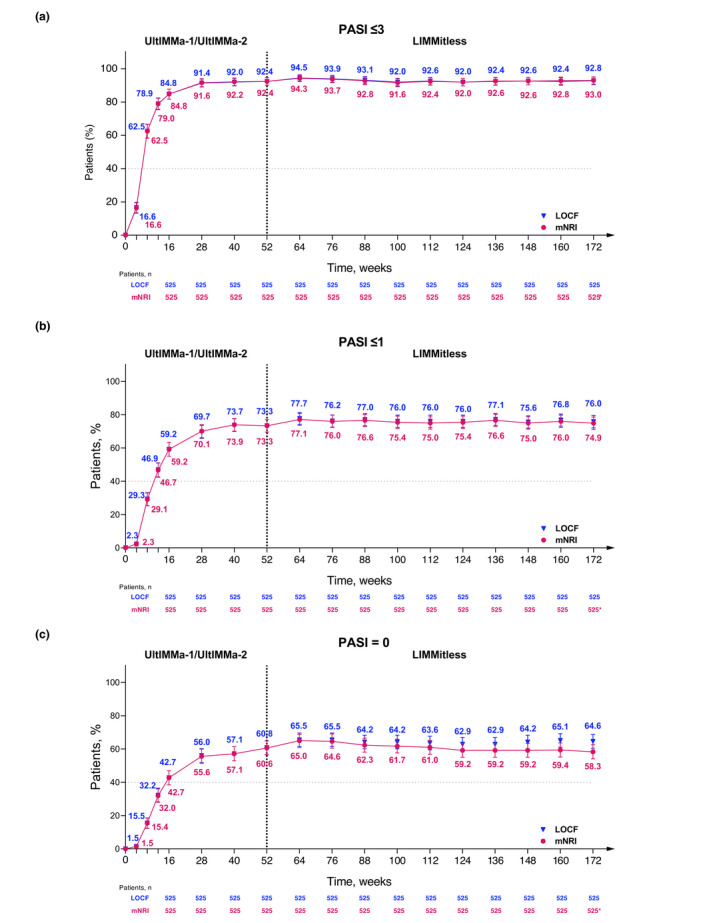

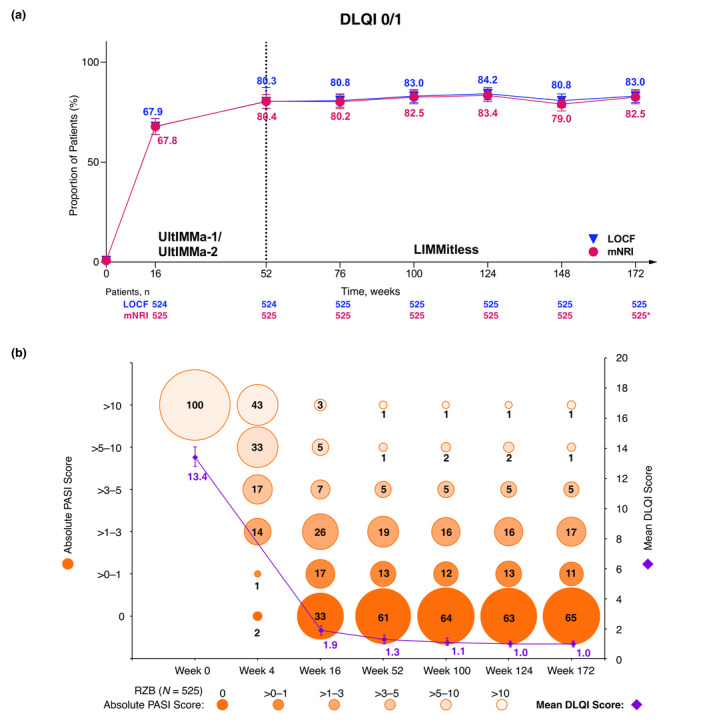

To assess the long‐term efficacy of risankizumab treatment, we evaluated the achievement of absolute PASI thresholds for patients who were initially randomised to risankizumab in UltIMMa‐1 or UltIMMa‐2, completed the base study, and enrolled in the ongoing LIMMitless OLE study (n = 525). At week 172, with more than 3 years of continuous risankizumab treatment, the proportion of patients achieving an absolute PASI ≤ 3 remained above 90% [92.8% (LOCF) and 93.0% (mNRI), Fig. 5a, 94.2% (OC) (N = 465), Table S2, Supporting Information]. Similar durability is demonstrated by the proportion of patients achieving absolute PASI ≤ 1 [75.8% (LOCF) and 74.9% (mNRI), Fig. 5b, 77.2% (OC) (N = 465), Table S2, Supporting Information] and PASI = 0 [64.8% (LOCF) and 58.3% (mNRI), Fig. 5c, 66.0% (OC) (N = 465), Table S2, Supporting Information]. Additionally, these patients achieved high rates of traditional measures PASI 90 [88.6% (LOCF), 88.4% (mNRI), and 90.5% (OC)] and PASI 100 [64.6% (LOCF), 62.9% (mNRI), and 66.0% (OC)], as well as 95.9% (LOCF) and 96.6% (OC) mean percent PASI improvement from baseline after 3 years of continuous risankizumab treatment (Fig. S2a,b and Table S2, Supporting Information). Long‐term risankizumab treatment also resulted in achievement of DLQI 0/1 in a high proportion of patients through week 172 [83.0% (LOCF) and 82.5% (mNRI), Fig. 6a, 84.3% (OC) (N = 471), Table S3, Supporting Information]. Grouping of absolute PASI response levels demonstrates high rates of skin clearance for risankizumab‐treated patients through week 172 (Fig. 6b). Long‐term risankizumab treatment also resulted in achievement of mean absolute DLQI < 2 by week 16 and mean DLQI = 1.0 at week 124 through week 172 (Fig. 6b).

Figure 5.

Long‐term achievement of absolute PASI thresholds (mNRI and LOCF). Percentage of patients achieving absolute PASI scores of (a) ≤3, (b) ≤1, (c) or = 0 over long‐term, continuous risankizumab treatment (OC, LOCF, and mNRI). *The drop‐off in response rates (mNRI) is attributed to the lower number of observations at this timepoint, as many patients had not yet completed 172 weeks of treatment by the time of this analysis. Due to more missing data at this time point, the mixed‐effect analysis results in lower response rates. Imputed patients who discontinued due to worsening of symptoms as non‐responders; all other missing data handled using mixed‐effects models. LOCF, last observation carried forward; mNRI, modified non‐responder Imputation; OC, observed cases; PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index.

Figure 6.

Long‐term achievement of (a) DLQI 0/1 (mNRI and LOCF), (b) absolute PASI categories, and mean absolute DLQI (LOCF). (a) Percentage of patients achieving DLQI 0/1 over long‐term, continuous risankizumab treatment (mNRI and LOCF). Error bars represent 95% confidence interval based on the normal approximation. *The drop‐off in response rates (mNRI) is attributed to the lower number of observations at this timepoint, as many patients had not yet completed 172 weeks of treatment by the time of this analysis. Due to more missing data at this timepoint, the mixed‐effect analysis results in lower response rates. (b) Percentage of patients within absolute PASI categories and mean DLQI achieved by patients with long‐term, continuous risankizumab treatment (LOCF). Each circle represents the proportion of patients falling into each absolute PASI category; the whole numbers indicate that proportion rounded to the nearest percentage. All patients started the trials with a PASI > 10 since 1 of the inclusion criteria required patients to have a baseline PASI ≥ 12. DLQI, Dermatology Life Quality Index; LOCF, last observation carried forward; mNRI, modified non‐responder Imputation (imputed patients who discontinued due to worsening of symptoms as non‐responders; all other missing data handled using mixed‐effects models). PASI, Psoriasis Area and Severity Index; RZB, risankizumab.

Rates of adverse events (AEs) ranged from 157.0–228.0 events/100 patient‐years (E/100 PY), serious AEs from 6.3–9.4 E/100 PY, and serious infections from 1.1–1.8 E/100 PY in the UltIMMa‐1/UltIMMa‐2 and LIMMitless populations (Table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment‐emergent adverse events

| Treatment‐emergent adverse events†, n (%) | Events (E/100 PY) | |

|---|---|---|

|

UltIMMa‐1/2 n = 598 (PY = 618) |

LIMMitless n = 525 (PY = 1909.5) |

|

| Any AE | 1409 (228.0) | 2998 (157.0) |

| Serious AE | 58 (9.4) | 121 (6.3) |

| Severe AE | 47 (7.6) | 109 (5.7) |

| AE leading to drug discontinuation | 5 (0.8) | 30 (1.6) |

| Serious infection | 11 (1.8) | 21 (1.1) |

| Active tuberculosis | 0 | 0 |

| Adjudicated MACE | 2 (0.3) | 1 (<0.1) |

| Malignancies | 3 (0.5) | 19 (1.0) |

| Malignancies excluding NMSC | 0 | 8 (0.4) |

| Serious hypersensitivity | 0 | 2 (0.1) |

| Deaths (including non‐TEAEs) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (0.2)† |

AE, adverse event; E/100 PY, events per 100 patient‐years; MACE, major adverse cardiac event; NMSC, non‐melanoma skin cancer; RZB, risankizumab; TEAEs, treatment‐emergent adverse events.

Events with onset after the first dose of RZB until 20 weeks after last dose of RZB. ‡Cardiopulmonary arrest, unrelated to study drug. §Automobile accident, unrelated to study drug. ¶Sudden cardiac death, unrelated to study drug.

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of the randomised, double‐blinded, controlled clinical trials UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 and the long‐term data from the OLE study LIMMitless, patients treated with risankizumab achieved clinically relevant absolute PASI thresholds and improved patient HRQoL. By these measures, risankizumab demonstrated superior efficacy to ustekinumab over 52 weeks and durable rates of efficacy over 172 weeks of continuous treatment.

Risankizumab treatment resulted in statistically superior (nominal P value) rates of patients achieving absolute PASI = 0, ≤1, and ≤3 compared to ustekinumab by week 8. In risankizumab‐treated patients, the proportion of patients treated with risankizumab who achieved an absolute PASI score of 0 continued to increase from week 16 to week 52. Risankizumab demonstrated numerically higher rates of achieving an absolute PASI = 0 and numerically lower rates of achieving absolute PASI scores >5 compared with ustekinumab at weeks 16 and 52. When assessed as rapidity of response, the median time to achieve PASI = 0, ≤1, and ≤3 was shorter for patients treated with risankizumab compared with ustekinumab. Long‐term, continuous risankizumab dosed Q12W provided long‐term maintenance of efficacy in terms of absolute PASI improvement through week 172, with most patients achieving clear skin (PASI = 0) for more than 3 years. Traditional measures of PASI 90, PASI 100, and mean percent PASI improvement also demonstrate consistently durable, high rates of skin clearance in this population. Safety outcomes for UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 have been previously reported, 19 and safety for long‐term risankizumab treatment was consistent with the known safety profile for risankizumab with no new safety signals. 29

With the emergence of new, improved therapies for psoriasis, high levels of skin clearance are increasingly considered as a treatment target because of the impact of residual disease on patients’ quality of life. 24 , 25 , 26 , 30 , 31 Patients who obtain clear or almost‐clear skin are more likely to report that psoriasis has no impact on their HRQoL and other measures of disease signs and symptoms. 27 , 28 , 32 In this analysis, achievement of low absolute PASI scores corresponded with an improvement in HRQoL as assessed by DLQI. Significantly greater proportions of risankizumab‐treated patients achieved combined PASI and DLQI improvements at weeks 16 and 52 than patients treated with ustekinumab; a majority of risankizumab patients achieved the treatment target of PASI ≤ 1 and DLQI 0/1 at week 52. In addition to high rates of PASI = 0, ≤1, and ≤3 achievement, more than 80% of patients treated with long‐term risankizumab achieved DLQI 0/1. Patients who continued to receive risankizumab long‐term in LIMMitless achieved a mean DLQI = 1.0 at week 124 and week 172. These data indicate that risankizumab results in improvement of clinical measures, when assessed for stringent absolute PASI and DLQI response levels. Treatment goals defined by absolute PASI targets provide an additional tool for a more standardised quality of care than measures of relative PASI improvement alone. 31

This study has several limitations. Notably, this is a post hoc analysis of the UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2 RCTs, which were not powered for measuring differences in absolute PASI. Additionally, due to the design of the LIMMitless OLE study, there is no direct comparator for long‐term data beyond week 52, which limits the conclusions of the long‐term assessments. The RCTs enrolled patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis, and thus the study populations were largely homogeneous with high baseline absolute PASI scores.

In summary, selective blockade of IL‐23 through binding the p19 subunit by risankizumab was superior to dual inhibition of IL‐12 and IL‐23 by ustekinumab in providing substantial skin clearance and improvement in HRQoL, with a rapid onset and durable maintenance of efficacy. A majority of patients treated with risankizumab achieved treat‐to‐target goals of absolute PASI and DLQI thresholds, both in comparison to ustekinumab and over long‐term risankizumab treatment.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Patient disposition for UltIMMa‐1/2 and LIMMitless.

Figure S2. Long‐term (a) PASI 90 and (b) PASI 100 achievement and (c) mean percent improvement in PASI from baseline.

Table S1. LIMMitless trial eligibility criteria.

Table S2. Long‐term achievement of absolute PASI thresholds (OC).

Table S3. Long‐term achievement of DLQI 0/1 (OC).

Table S4. Long‐term achievement of PASI 90 and PASI 100 (OC).

Video S1. Percentage of patients within absolute PASI score categories over time (LOCF).

Acknowledgements

AbbVie and the authors thank all study investigators for their contributions and the patients who participated in these studies. AbbVie, Inc. funded the research for these studies and provided writing support for this abstract. RBW is supported by the Manchester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre. The authors would like to acknowledge Priya S. Mathur, PhD of AbbVie for medical writing support in the production of this publication.

Conflicts of interest

M Gooderham has been an investigator, speaker, adviser, or consultant for AbbVie, Amgen, Akros, Arcutis, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, BMS, Celgene, Coherus, Dermira, Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Galderma, GSK, Incyte, Janssen, Kyowa Kirin Pharma, Leo Pharma, MedImmune, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Regeneron, Sanofi‐Genzyme, Sun Pharma, UCB, and Valeant/Bausch. A Pinter has been an investigator, speaker, adviser, or consultant for AbbVie, Allmirall‐Hermal, Amgen, Biogen Idec, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Celgene, GSK, Eli Lilly, Galderma, Hexal, Janssen, LEO Pharma, MC2, Medac, Merck Serono, Mitsubishi, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Tigercat Pharma, Regeneron, Roche, Sandoz Biopharmaceuticals, Schering‐Plough, and UCB Pharma. LK Ferris has been an investigator for Amgen, AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, BMS, Acrutis, Dermavant, Regeneron, InflaRx, Novartis, and UCB; and a consultant for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, BMS, Arcutis, Dermavant, and Pfizer. RB Warren received grants from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Lilly, LEO Pharma, Medac, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB and received personal fees from AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Astella’s, Avillion, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, Celgene, DiCE, GSK, Janssen, Lilly, LEO Pharma, Medac, Novartis, Pfizer, Sanofi, Sun Pharma, UCB, and UNION. B Strober has been a Consultant (honoraria) for AbbVie, Almirall, Amgen, Arcutis, Arena, Aristea, Asana, Boehringer‐Ingelheim, Immunic Therapeutics, Bristol Myers Squibb, Connect Biopharma, Dermavant, Equillium, Janssen, Leo, Eli Lilly, Maruho, Meiji Seika Pharma, Mindera, Novartis, Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline, UCB Pharma, Sun Pharma, Ortho Dermatologics, Regeneron, Sanofi‐Genzyme, Ventyxbio, and vTv Therapeutics; a Speaker for AbbVie, Eli Lilly, Janssen, and Sanofi‐Genzyme; a Co‐Scientific Director (consulting fee) for CorEvitas (formerly Corrona) Psoriasis Registry; an Investigator for Dermavant, AbbVie, Corrona Psoriasis Registry, Dermira, Cara, and Novartis; a Shareholder of Connect Biopharma; and an Editor‐in‐Chief (honorarium) for the Journal of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis. T Zhan, J Zeng, AM Soliman, C Kaufmann, B Kaplan, and H Photowala are full‐time employees of AbbVie Inc. and may hold stock or stock options.

Funding sources

AbbVie funded the research for these studies and provided writing support for this abstract. AbbVie participated in the study design; study research; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; and writing, reviewing, and approving this abstract for submission. All authors had access to the data and participated in the development, review, and approval of the abstract. No honoraria or payments were made for authorship.

Data availability statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual, and trial‐level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols and clinical study reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our‐science/clinical‐trials/clinical‐trials‐data‐and‐information‐sharing/data‐and‐information‐sharing‐with‐qualified‐researchers.html.

References

- 1. Di Meglio P, Villanova F, Nestle FO. Psoriasis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014; 4: a015354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goff KL, Karimkhani C, Boyers LN et al. The global burden of psoriatic skin disease. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172: 1665–1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Harden JL, Krueger JG, Bowcock AM. The immunogenetics of psoriasis: a comprehensive review. J Autoimmun 2015; 64: 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Papp KA, Gniadecki R, Beecker J et al. Psoriasis prevalence and severity by expert elicitation. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 2021; 11: 1053–1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ros S, Puig L, Carrascosa JM. Cumulative life course impairment: the imprint of psoriasis on the patient's life. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2014; 105: 128–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vanaclocha F, Crespo‐Erchiga V, Jimenez‐Puya R et al. Immune‐mediated inflammatory diseases and other comorbidities in patients with psoriasis: baseline characteristics of patients in the AQUILES study. Actas Dermosifiliogr 2015; 106: 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Elmets CA, Leonardi CL, Davis DMR et al. Joint AAD‐NPF guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with awareness and attention to comorbidities. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019; 80: 1073–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Blauvelt A, Papp KA, Griffiths CE et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the continuous treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis: results from the phase III, double‐blinded, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 1 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 405–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gordon KB, Blauvelt A, Papp KA et al. Phase 3 trials of ixekizumab in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2016; 375: 345–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Langley RG, Elewski BE, Lebwohl M et al. Secukinumab in plaque psoriasis–results of two phase 3 trials. N Engl J Med 2014; 371: 326–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Papp K, Crowley J, Ortonne JP et al. Adalimumab for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: efficacy and safety of retreatment and disease recurrence following withdrawal from therapy. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164: 434–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Iskandar IYK, Warren RB, Lunt M et al. Differential drug survival of second‐line biologic therapies in patients with psoriasis: observational cohort study from the British Association of Dermatologists Biologic Interventions Register (BADBIR). J Invest Dermatol 2018; 138: 775–784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. No DJ, Inkeles MS, Amin M et al. Drug survival of biologic treatments in psoriasis: a systematic review. J Dermatolog Treat 2018; 29: 460–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chan TC, Hawkes JE, Krueger JG. Interleukin 23 in the skin: role in psoriasis pathogenesis and selective interleukin 23 blockade as treatment. Ther Adv Chronic Dis 2018; 9: 111–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Di Meglio P, Nestle F. The role of IL‐23 in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. F1000 Biol Rep 2010; 2: 40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Reich K, Armstrong AW, Foley P et al. Efficacy and safety of guselkumab, an anti‐interleukin‐23 monoclonal antibody, compared with adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderate to severe psoriasis with randomized withdrawal and retreatment: results from the phase III, double‐blind, placebo‐ and active comparator‐controlled VOYAGE 2 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 418–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Reich K, Papp KA, Blauvelt A et al. Tildrakizumab versus placebo or etanercept for chronic plaque psoriasis (reSURFACE 1 and reSURFACE 2): results from two randomised controlled, phase 3 trials. Lancet 2017; 390: 276–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Reich K, Gooderham M, Thaci D et al. Risankizumab compared with adalimumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis (IMMvent): a randomised, double‐blind, active‐comparator‐controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2019; 393: 576–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gordon KB, Strober B, Lebwohl M et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab in moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis (UltIMMa‐1 and UltIMMa‐2): results from two double‐blind, randomised, placebo‐controlled and ustekinumab‐controlled phase 3 trials. Lancet 2018; 392: 650–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaffen SL, Jain R, Garg AV et al. The IL‐23‐IL‐17 immune axis: from mechanisms to therapeutic testing. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14: 585–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Papp KA, Blauvelt A, Bukhalo M et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2017; 376: 1551–1560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Warren RB, Blauvelt A, Poulin Y et al. Efficacy and safety of risankizumab vs. secukinumab in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis (IMMerge): results from a phase III, randomized, open‐label, efficacy‐assessor‐blinded clinical trial. Br J Dermatol 2021; 184: 50–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Armstrong AW, Siegel MP, Bagel J et al. From the Medical Board of the National Psoriasis Foundation: treatment targets for plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2017; 76: 290–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Blauvelt A, Griffiths CEM, Lebwohl M et al. Reaching complete or near‐complete resolution of psoriasis: benefit and risk considerations. Br J Dermatol 2017; 177: 587–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Puig L, Dossenbach M, Berggren L et al. Absolute and relative Psoriasis Area and Severity Indices (PASI) for comparison of the efficacy of ixekizumab to etanercept and placebo in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis: an integrated analysis of UNCOVER‐2 and UNCOVER‐3 outcomes. Acta Derm Venereol 2019; 99: 971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gerdes S, Korber A, Biermann M et al. Absolute and relative Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) treatment goals and their association with health‐related quality of life. J Dermatolog Treat 2020; 31: 470–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Strober B, Papp KA, Lebwohl M et al. Clinical meaningfulness of complete skin clearance in psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2016; 75: 77–82.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Feldman SR, Bushnell DM, Klekotka PA et al. Differences in psoriasis signs and symptom severity between patients with clear and almost clear skin in clinical practice. J Dermatolog Treat 2016; 27: 224–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gordon KB, Lebwohl M, Papp KA et al. Long‐term safety of risankizumab from 17 clinical trials in patients with moderate‐to‐severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2021. 10.1111/bjd.20818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. van den Reek J, van Vugt LJ, van Doorn MBA et al. Initial results of secukinumab drug survival in patients with psoriasis: a multicentre daily practice cohort study. Acta Derm Venereol 2018; 98: 648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zweegers J, Roosenboom B, van de Kerkhof PC et al. Frequency and predictors of a high clinical response in patients with psoriasis on biological therapy in daily practice: results from the prospective, multicenter BioCAPTURE cohort. Br J Dermatol 2017; 176: 786–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Viswanathan HN, Chau D, Milmont CE et al. Total skin clearance results in improvements in health‐related quality of life and reduced symptom severity among patients with moderate to severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat 2015; 26: 235–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Patient disposition for UltIMMa‐1/2 and LIMMitless.

Figure S2. Long‐term (a) PASI 90 and (b) PASI 100 achievement and (c) mean percent improvement in PASI from baseline.

Table S1. LIMMitless trial eligibility criteria.

Table S2. Long‐term achievement of absolute PASI thresholds (OC).

Table S3. Long‐term achievement of DLQI 0/1 (OC).

Table S4. Long‐term achievement of PASI 90 and PASI 100 (OC).

Video S1. Percentage of patients within absolute PASI score categories over time (LOCF).

Data Availability Statement

AbbVie is committed to responsible data sharing regarding the clinical trials we sponsor. This includes access to anonymised, individual, and trial‐level data (analysis data sets), as well as other information (eg, protocols and clinical study reports), as long as the trials are not part of an ongoing or planned regulatory submission. This includes requests for clinical trial data for unlicensed products and indications.

This clinical trial data can be requested by any qualified researchers who engage in rigorous, independent scientific research, and will be provided following review and approval of a research proposal and statistical analysis plan and execution of a data sharing agreement. Data requests can be submitted at any time and the data will be accessible for 12 months, with possible extensions considered. For more information on the process, or to submit a request, visit the following link: https://www.abbvie.com/our‐science/clinical‐trials/clinical‐trials‐data‐and‐information‐sharing/data‐and‐information‐sharing‐with‐qualified‐researchers.html.