SUMMARY

Leaf heading is an important and economically valuable horticultural trait in many vegetables. The formation of a leafy head is a specialized leaf morphogenesis characterized by the emergence of the enlarged incurving leaves. However, the transcriptional regulation mechanisms underlying the transition to leaf heading remain unclear. We carried out large‐scale time‐series transcriptome assays covering the major vegetative growth phases of two headingBrassica crops, Chinese cabbage and cabbage, with the non‐heading morphotype Taicai as the control. A regulatory transition stage that initiated the heading process is identified, accompanied by a developmental switch from rosette leaf to heading leaf in Chinese cabbages. This transition did not exist in the non‐heading control. Moreover, we reveal that the heading transition stage is also conserved in the cabbage clade. Chinese cabbage acquired through domestication a leafy head independently from the origins of heading in other cabbages; phylogenetics supports that the ancestor of all cabbages is non‐heading. The launch of the transition stage is closely associated with the ambient temperature. In addition, examination of the biological activities in the transition stage identified the ethylene pathway as particularly active, and we hypothesize that this pathway was targeted for selection for domestication to form the heading trait specifically in Chinese cabbage. In conclusion, our findings on the transcriptome transition that initiated the leaf heading in Chinese cabbage and cabbage provide a new perspective for future studies of leafy head crops.

Keywords: leafy head, Brassica, Chinese cabbage, cabbage, transcriptome, transition stage, ethylene, temperature response

Significance Statement

By profiling the gene expression dynamics during the heading formation in Chinese cabbage and cabbage, as compared with a non‐heading control, we identified a conserved, temperature‐responsive Leaf Heading Transition Stage marked by the transcriptional reprogramming along with the development of folding leaves. We highlight the ethylene pathway, whose genes are activated during the transition in Chinese cabbage, as the unintended target of domestication, which implies the existence of significant variation within the ancestral non‐heading races.

INTRODUCTION

Leaf heading is a distinctive horticultural trait that was domesticated multiple times for leafy vegetables, including the Chinese cabbage, cabbage, and lettuce (Doebley et al., 2006; Qi et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2019). The leafy head confers multiple advantages, such as higher yield, a longer storage life, and ease of product transport. In the vegetative growth period of leaf heading crops, the rosette stage is followed by an additional heading stage that does not exist in non‐heading crops. However, how the heading stage initiates and what biological activities or stimuli is part of this process remain unclear.

As an agronomically important vegetable from the genus Brassica of the Brassicaceae family, Chinese cabbage (Brassica rapa ssp. pekinensis) is a promising species for the investigation of the leafy head. It was domesticated from non‐heading ancestral morphotypes about 500 years ago in China as recorded by Ben Cao Gang Mu (Compendium of Materia Medica). Today, in many countries, particularly China, Korea, and Japan, Chinese cabbage is one of the most frequently consumed vegetables. Cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata) is another important Brassica vegetable worldwide. Cabbage was domesticated a second time, in the eastern Mediterranean, approximately 2–3000 years ago (Mabry et al., 2021). Considering the importance of Chinese cabbage and cabbage, their genomes were among the first vegetables sequenced (Liu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2011). Genome analysis revealed that the Brassica ancestor experienced a paleo‐hexaploidization event about 11 million years ago, which then re‐diploidized and evolved into different Brassica species (Cheng et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2011). Although many of the paralogous genes derived from the whole‐genome triplication were fractionated (loss of a duplicate), the retained ones probably fueled both the domestication and the diversification of traits (Cai et al., 2021; Cheng et al., 2018; Liang & Schnable, 2018; Zhang et al., 2019). Through artificial selection, both the Chinese cabbage and cabbage developed the heading trait, a sign of convergent domestication as evidenced in a previous resequencing study of B. rapa and B. oleracea (Cheng et al., 2016). Given the above, it is probable that the ancestral leaf morphotype for all Brassica is non‐heading; heading is a derived trait that experienced multiple independent domestication processes.

As a complex trait, development of the leafy head involves the incurve and enlargement of the leaf blade, shortening of the petiole, and/or change of the leaf angle associated with petiole morphology. For the heading Brassica crops, including the Chinese cabbage (Chiifu, HN53) and cabbage (JQ1) cultivars used in these studies, the heading capableness (competence) and earliness‐of‐heading are varied and are differentially affected by environmental factors during cultivation. The morphology changes associated with the heading process occur after the rosette stage. It is noteworthy that, after the heading process initiates, newborn leaves carrying the heading morphological characteristics (so‐called heading leaves) form the leafy head, while the already‐developed and differentiated rosette leaves stay unchanged, and thereby support the heading and all growth through photosynthesis (Sun et al., 2019). This history of rosette leaves in heading varieties suggested that a developmental switch might have occurred all over the leaf system. These several changes constituting the rosette to the heading stage switch is similar, but only similar, to the juvenile‐to‐adult phase transition during the vegetative growth of plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana (Arabidopsis), which also is accompanied by morphological changes such as the emergence of the abaxial trichomes (Telfer et al., 1997). Efforts to understand the juvenile‐to‐adult phase transition (a transition that is universal to all Brassica leaves and that is not heading‐specific) led to the identification of the central miR156‐SPL (SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING‐LIKE) module, as well as the endogenous and environmental factors affecting the timing and duration of the change to the adult leaf program (Poethig, 2013). However, the initiation of the heading process that occurred following the rosette stage has been, historically, enveloped in the adult stage, not the juvenile stage, based on the adult characters of leaf morphology (Wang et al., 2014). Although the ultimate origin of the “transition to heading” switch may involve shoot meristem, the transition from the rosette to heading phase is realized through the morphological and transcriptional changes of leaves. Therefore, the investigation of a hypothetical heading transition required a unique experimental design to focus on what happened throughout the heading process rather than the differentiation of individual leaves. Several genes associated with Brassica heading have been reported, including BcpLH (particular mRNA processing), BrpTCP4 (a mRNA target), BrARF3 (an auxin response factor), and BrBRX (involved in the crosstalk between auxin and brassinosteroid [BR]) (Cheng et al., 2016; Mao et al., 2014; Ren et al., 2020). However, there are no published developmental stages or intervals between the adult rosette leaves and the following heading leaves.

This study hopes to explore the possibility that a heading‐specific stage might, based on its placement in time, initiate the heading leaf growth. We call this hypothetical stage the “Leaf Heading Transition Stage.” Our primary experiment sampled the third leaf visible without dissection in a time‐series manner for transcript analysis. This leaf is fully developed, with a small petiole and blade, and differentiated. For developmental biologists used to using the unit “plastochron” for comparing leaves, here we hold constant the third leaf at approximately 5 cm long, and therefore sample plastochrons of increasing number over a 3‐month period. What changes over the course of the experiment are the number and size and photosynthetic activity of the leaves; the third visible leaf stays about the same to the eye. In so doing, we hope to capture a heading transition interval between the rosette and heading stages. What we sampled for our two Chinese cabbages (Chiifu and HN53) were also sampled from a non‐heading control (WS). A second heading cabbage (JQ1) is also included, because we hope to understand better how heading might have been repeatedly, but independently, bred as an agricultural trait.

Our framework for understanding heading at the onset of this study was to envision a Chinese cabbage plant growing as a rosette (not heading), and that it will continue to do so until the flowering transition, all without ever making a head. A period of suitable temperature or similar environmental signal triggers this rosette‐stage to switch to heading. As our experimental design was successful in identifying, via transcript clusters, a transition stage, the next question is: How did a transition stage get programmed into the rosette leaves? We further explore this question. Certainly, the meristem may be the candidate for involvement. However, the “make a head” signal is likely moving from the most developed part of the plant back to the smaller differentiating leaves.

Clusters of coordinately regulated genes discovered in time course studies are easier to understand if some better known diagnostic genes are expected a priori to be involved in any cluster even before the experimental results are in. The heading process itself, the physiological overgrowth of the abaxial (outer) layers of leaf cells, is likely to involve asymmetric leaf regulation and differential expansion. Our results will show that some of these expectations were met, and others were not.

The morphological resolution of this study is gross. We assay the leaf in two components, the petiole and the blade; each of these components is composed of three tissues, epidermis tissue with adaxial and abaxial orientations, and several types of cells. Identifying the heading transition stage did not necessitate finer resolution than the organ component. Understanding how this stage might receive signals and initiate heading will certainly require, at minimum, more cellular specificity.

RESULTS

Transcriptome dynamics of heading Brassica rapa identified a potential Leaf Heading Transition Stage

The heading B. rapa, Chiifu (Chiifu‐401‐42; Figure 1a), which is a cultivar that differentiates into an oblong leafy head, was chosen for our exploratory studies. In addition, Chiifu is the reference genome of B. rapa (Wang et al., 2011). The rosette leaves of Chiifu displayed a circular phylotaxy with relatively low plant height. Afterwards, the heading leaves begin an upward and then incurved‐growing pattern to form the leafy head (Figure S1a).

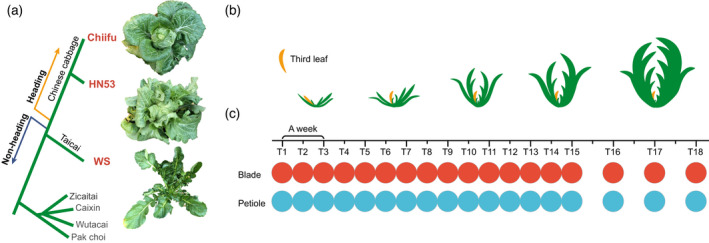

Figure 1.

Overview of the experimental design of the microRNA‐sequencing assay.

(a) Dendrogram showing the phylogenetic relationships among heading morphotypes Chiifu and HN53, and non‐heading morphotype Taicai WS. Gray fonts denote other phylogenetically distant Brassica rapa morphotypes.

(b) Leaf sampling process. The third visible leaf (count from inside out, yellow color) was collected.

(c) Schematic overview of the experimental design for three morphotypes. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

In an attempt to explore the transcriptional alterations throughout the heading process of Chinese cabbage, we conducted a time‐series microRNA (mRNA)‐seq assay, which lasted for 3 months spanning the major vegetative phase of Chiifu. Given the hypothesis that the switch from the rosette to the heading stage involves a leaf‐system‐level heading transition, we sampled the third leaf visible as a proxy of the transcriptome status of leaves at each time point. These third visible leaves were collected with comparable sizes (approximately 5 cm long) to rule out the potential transcriptomic differences lying in the leaves with different sizes (Figure 1b). The blade and petiole in one leaf were separated and prepared for the mRNA‐seq. As indicated in Figure 1c, bi‐weekly testing was arranged for leaf samples. The sampling process began at the early rosette stage (approximately six leaves) with the emergence of the adult leaves (Wang et al., 2014). While in the last 3 weeks, the size and shape of the leafy head of Chiifu were generally stabilized, indicating that any potential heading transition had come and gone over time. Therefore, such stabilized leaves were sampled once each week. In total, samples were collected at 18 consecutive time points (T1–18). This experimental design allowed us to establish a transcriptome time course, where a leaf at a set young stage of differentiation was tested over and over again over time elapsed (as plastochron number increased).

Paired‐end mRNA‐seq was conducted for these samples. After filtering out the low‐quality or ambiguous RNA‐seq data, a total of 105 gene expression profiles at 18 time points were obtained (Table S1). The average correlation coefficient among biological replicates was 0.94, indicating the high quality and reproducibility of our dataset. In general, gene expressions are estimated by transcript per million (TPM), and the number of expressed genes (TPM ≥0.1) varied from 28 035 to 30 104, with 29 007 on average.

A clear regulatory transition stage (T5–8; Figure 2) from rosette to leafy head development was identified, which was coordinated with the morphological changes, and is marked by obvious transcriptional reprogramming. By comparing the distances between any two time points evaluated through the Pearson's correlation coefficient (PCC), we built a cladogram representing clustering of the leaf blade transcriptome in our focal heading cultivar, Chiifu. As shown in Figure 2a, four clades were obtained, including the T1–4, T5–8, T9–13, and T14–18. The first clade T1–4 represents the rosette stage, as these sampling time points matched with the observed rosette leaves during this period (Figure S1a). The T5–8 clade was accompanied by the emergence of the upward‐tilted leaf above the rosette leaves (approximately 40 days after sowing), and this morphological pattern was generally stabilized at T8 (Figure S1a). Therefore, the T5–8 clade was considered to be corresponded with the transition from rosette to the heading stage and was named as the Leaf Heading Transition Stage (II). Previously, a folding stage was introduced to depict a short period with the emergence of incurved leaf, the incurvature level of which is not that extreme as those in the heading stage (Wang et al., 2014). It was observed that the folding stage was embedded in the late half of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage. Furthermore, rough examination of genes upregulated in this transition stage revealed that the biological regulation‐related Gene Ontology (GO) terms were significantly enriched, a sign of active transcription reorganization (Figure 2b). In contrast, ribosome and biosynthesis‐related terms were enriched in the following T9–13 clade, while transport and cell wall organization‐related GO terms were enriched in the last T14–18 clade (Table S2). Therefore, we defined the T9–13 stage as the heading growth stage (III) and the last time points (T14–18) as the heading mature stage (IV), respectively.

Figure 2.

Identification of the transition stage in Chinese cabbage (Chiifu).

(a) Time‐series transcriptomes of Chiifu leaves were clustered into four clades (indicated by different colors). PCC, Pearson's correlation coefficient.

(b) Gene Ontology enrichment analysis revealed distinct functional enrichments of genes highly expressed in the stage T5–8 (II) and in the stage T9–13 (III). The color of the circle indicates the statistical significance (here as P value), and circle size indicates the percentage of genes carrying certain GO term.

(c) Clustering of the time‐series transcriptomes of the non‐heading WS using the same method as (a).

(d) Gene expression heatmap for those genes that were significantly upregulated at least one time point among T5–13 as compared with both T1–4 and T14–18. A gene set (marked with yellow lines in the left dendrogram) was specifically transcriptionally activated in the hypothetical transition stage.

(e) Activation of hormone‐related genes in the transition stage (highlighted in yellow) is exemplified by several genes.

(f) Scenario of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) enrichment at different time points. Enriched KEGG pathways were determined based on the representative genes at each time point. The transition stage and corresponding KEGG pathways are marked by bold fonts on an orange background. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The Leaf Heading Transition Stage is distinct in the profiles of particular genes. By selecting and clustering the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that were significantly upregulated in the heading transition stage or the heading growth stage, we found that 22 genes were upregulated specifically in the transition stage using a strict cutoff (Figure 2d; Table S3; Experimental procedures). Among them, nine genes directly involve phytohormone signaling pathways, particularly the ethylene pathway (Figure 2e). Also found in the transition were upregulated genes predicted to encode growth regulators, such as the two copies of BG1 (big grain1) that positively regulate the polar auxin transport (Liu et al., 2015) (Figure 2e).

We determined the representative genes (RGs) for each time point by introducing stringent thresholds to remove the genes that were expressed stably across the heading process (Table S4). The RG‐based functional enrichments revealed the most distinct characteristic of the transition stage, as illustrated in Figure 2f, where particular Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways proved to be significantly enriched: “MAPK signaling pathway—plant” and “Plant hormone signal transduction.”

Leaf Heading Transition Stage is specific to heading cultivars; non‐heading WS lacks the transition stage in the blade

We then examined whether the Leaf Heading Transition Stage exists in the non‐heading morphotype. Considering that the heading trait was selected from the non‐heading morphotypes, we checked the phylogenetic tree based on the B. rapa population and identified the non‐heading morphotype Taicai as the phylogenetically closest clade to the heading Chinese cabbage as compared with other non‐heading ones such as Pak choi (Figure 1a) (Cheng et al., 2016). Therefore, a Taicai cultivar, WS, was selected as the non‐heading control. In contrast to Chiifu, the leaves of WS stayed loose with gradually enlarged leaf blade and elongate petiole (Figure S1b). The transcriptomes of WS were then profiled following the sampling method used for Chiifu (Figure 1c). We generated the transcript clustering cladogram and the KEGG enrichment heatmap based on RGs of WS, and then compared them with those for the heading cultivar Chiifu. While there is an overall similarity between the transcript clustering cladograms, of heading versus control leaves, there is one obvious difference. The putative “Leaf Heading Transition Stage,” T5–8, does not exist in WS, the non‐heading control (Figure 2c), and WS did not experience the transcription reorganization (Table S5). As seen in the heatmap of the aforementioned DEGs upregulated in the transition stage of Chiifu, these genes were not activated in the non‐heading control (Figure 2d). Meanwhile, for the KEGG enrichment heatmap, the non‐heading control shows no evidence of enrichment of “plant hormone signaling” or “MAPK signaling pathway” as that of Chiifu in T5–8 (Figure S2). We tentatively conclude that T5–8 (II), the Leaf Heading Transition Stage, is specific to Chinese cabbage varieties that make a head, and that the reason non‐heading B. rapa morphotypes do not head is because they lack the multigene program (i.e., the program of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage) necessary to initiate heading.

The Leaf Heading Transition Stage was also found in leaf petioles of Chinese cabbage. Using the sampling protocols shown in Figure 1, and the now diagnostic signaling pathway enrichments, we tried to find the Leaf Heading Transition Stage in the petiole of Chiifu. Coordinately, similar functional enrichments such as the phytohormone pathway in the transition stage of Chiifu leaf blade were found in the petiole organ (Figure S3a). We also investigated the expression dynamics of the DEGs shown in Figure 2d and found that the majority of them (15 of 20, two other genes excluded because they were not expressed in the petiole) were upregulated during the transition stage in petiole, as well as showed higher expression level than in the non‐heading WS (Figure S3b). These results suggested that the transition towards heading development occurred in the leaf system, both the leaf blade and petiole, of Chinese cabbage.

Further characteristics of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage

The transition stage is accompanied by the activation of genes involved in the leaf asymmetric growth, and certainly involves differential cell expansion. For example, through focusing on the leaf adaxial–abaxial polarity regulation genes, we found that four abaxial‐related genes (two BrKAN2s and two BrARF4s) were activated during the transition stage, and the expressions of many other abaxial genes increased gradually and reached the peaks at the heading mature stage (IV) (Figure S4a). While for the adaxial genes, four of five genes exhibited the expression peaks during the heading growth stage (III). We also found that genes known to participate in leaf curvature such as BrPLL5 and BrPRE2 were upregulated in the transition stage (Table S6) (Song & Clark, 2005; Zhu et al., 2017). In addition, based on the sorts of genes exclusively upregulated in the transition stage, and those genes that showed divergent expression patterns during the transition stage, we built three functional gene modules (Figure S4b–d). These modules were predicted to be associated functionally and were overall activated during the transition stage, involved asymmetric adaxial/abaxial growth, and included those genes associated with regulating the polar auxin transport, microtubule organization, and BIN2‐involved cell differentiation and division. Those genes listed in Table S7, as well as those aforementioned 22 transition‐stage‐upregulated genes (Figure 2d), could be putative diagnostic gene markers for the transition stage, and are promising candidates for future functional studies.

Heading transition stage is conserved in Brassica heading crops, continued

A second heading B. rapa cultivar was sampled in the same way as Chiifu (heading) and WS (non‐heading): HN53. HN53 is later‐maturing, and exhibits a looser overlapping leafy head with larger leaves compared with Chiifu (Figure 1a). We compared the gene expression profiles of HN53 with those of Chiifu and the non‐heading WS control. Although the leafy heads of HN53 and Chiifu varied in shape (Figure S5a), the gene expression correlation and the DEG comparison analyses revealed that HN53 and Chiifu showed high transcriptional similarity contrasting WS (Figure 3a; Figure S5b). In addition, more genes were highly expressed in Chiifu than in HN53 when compared with WS (Figure S5b), indicating that HN53 experienced a moderate transcriptional reprogramming process relative to Chiifu during the leafy head development. We then examined the expression patterns of hormonal and MAPK‐related genes that were significantly activated in the transition stage of Chiifu, and found that most of them were activated in HN53 (Figure 3b; Figure S5c). Intriguingly, they generally followed an attenuated expression pattern spanning a longer period (T5–12) than that in Chiifu (Figure 3c). The pattern of the aforementioned transition‐activated marker biological pathways, as well as the diagnostic genes (Figure S5d), implied a longer but gentler transition stage in HN53, which coincided with the later‐maturing property of HN53 as compared with Chiifu. These results reinforce our conclusion that heading Chinese cabbages, probably all of them, have a heading transition stage.

Figure 3.

Conservation of the heading transition stage in heading Brassica rapa HN53 and in cabbage JQ1.

(a) Line chart illustrating the Pearson's correlation coefficient distribution of different pairs (Chiifu vs. WS, HN53 vs. WS, and Chiifu vs. HN53).

(b) Plant hormone‐associated genes exhibit different expression patterns in Chiifu and HN53. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) genes were upregulated during the transition stage of Chiifu as compared with WS. Their fold‐changes (red) relative to WS in the transition and heading growth stages were calculated. Their performances in HN53 (green) were also collected using the same method. DEGs, differentially expressed genes.

(c) Expression patterns of hormone‐associated genes in Chiifu (left) and in HN53 (right) are exemplified by typical cases. Differences in expression patterns are consistent with the tendency reflected by the boxplots (d). TPM, transcript per million.

(d) Snapshot of the heading cabbage JQ1.

(e) Sampling strategy for cultivar JQ1. In total, 12 leaf samples were collected with the sampling interval indicated, using days as the unit.

(f) KEGG gene enrichment based on the DEGs between heading stages and the rosette stage of JQ1. Upper panel shows the enriched KEGG pathways (orange) based on genes that were downregulated in the heading stages compared with the rosette stage; bottom panel shows the pathways (green) based on genes that were upregulated in the heading stages compared with the rosette stage. Orange highlights (in c left and f) denote the transition stage of Chiifu (T5–8) and JQ1 (C3–6), respectively, while the green highlight (c right) shows the potentially longer transition stage of HN53 (T5–12). [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We further generated a time‐series mRNA‐seq assay for leaves in a heading cabbage JQ1 using a sampling strategy similar to that used for our focal morphotype, Chiifu: 12 time points (C1–12) (Figure 3d,e). By combining the clustering and time‐series comparison results with the phenotypic changes, a transition stage was also identified in cabbage, spanning four time points (C3–6, approximately 10 days; Figure S6). As expected the transition stage followed the rosette stage, during which time genes that were photosynthesis‐related were enriched. A heading growth stage followed, with gene transcript upregulation consistent with enhanced cell proliferation (Figure 3f). This transition stage is marked by the upregulation of genes in phytohormone‐related pathways and genes encoding transcription factors, which is consistent with Chiifu data. Moreover, we identified the cabbage orthologues of those transition‐activated diagnostic genes in Chiifu, investigated their expression patterns, and found that most of them (23 of 28) were upregulated in the transition stage of cabbage (Figure S6b). The identification of the transition stage in cabbage suggested that the ability to make a head marked by the presence of a Leaf Heading Transition Stage has evolved (i.e., by artificial selection/domestication) independently in Chiifu (Chinese cabbage) and JQ1 (cabbage).

Low temperature delays heading, and the Leaf Heading Transition Stage is involved

Both the Chinese cabbage and cabbage are cold‐weather crops, and high temperatures have an adverse impact on their leafy head formation. Cultivation of Chinese cabbage Chiifu in a plant incubator with a constant temperature of 25°C demonstrated that they failed to form the leafy head when expected (60 days) and even after >60 days of growth. These plants developed considerable numbers of adult leaves (Figure S7). To address the influences of high temperatures on the transcriptional regulation of the heading process, we planted Chiifu in a greenhouse and collected the leaf organs at the same time points as those growing outdoors in a plastic shed. The temperature in the greenhouse dropped much more slowly and was about 10°C higher than that in the plastic shed during heading development (Figure 4a). In line with the temperature difference, the formation of the leafy head in the greenhouse was much later (at least 10 days; Figure 4b; Figures S1 and S8). For clarity, we named the Chiifu in the plastic shed CFP, and the Chiifu in the greenhouse CFG.

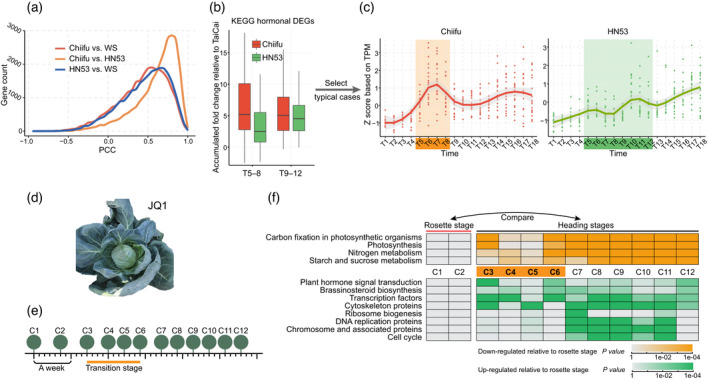

Figure 4.

Delayed activation of heading regulatory genes in a higher temperature environment.

(a) Temperatures in the plastic shed and greenhouse. Chiifu in the shed was named CFP, while Chiifu in the greenhouse was named CFG.

(b) Delayed heading process of CFG as shown by photos.

(c) Histograms showing the variation in expression peak of genes in CFP and CFG. Upper panel shows the frequency of gene expression peaks locating in the transition stage of CFP, while the bottom panel shows their corresponding expression peaks in CFG. The time point with the largest number of genes shifted from T6 in CFP to T7 in CFG, indicating a delay in expression peak. (d) The vast majority of transition‐activated Chiifu genes as identified above were delayed in CFG. According to the dendrogram, these genes were divided into five clades. (e) Expression patterns of genes in five clades as identified in (d). Transition stage is marked by bold fonts on an orange background. TPM, transcript per million. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

By identifying and comparing the expression peaks of genes between CFP (outdoors) and CFG (indoors), we found that the transition‐activated genes in CFG were delayed by one or more time points compared with CFP, causing the overall gene expression peak to move from T6 to T7 (Figure 4c). We identified genes with delayed expression peaks in CFG. For instance, the expressions of microtubule organization‐associated genes BrMAP70‐2 and BrMAP70‐4 were delayed (Table S8). More importantly, genes identified within the marker pathways “plant hormone” and “MAPK” were enriched in these delayed genes (Table S9; Figure S9), while the expressions of most of the transition‐activated genes in CFP were also elevated in CFG, but showed postponed activation (Figure 4d). As shown by the major gene clade in Figure 4d, some genes in CFP exhibited bimodal expression curves: one peak at T6–7, and a smaller peak at T14. Correspondingly, in CFG, they appeared with two peaks but at delayed time points (T8–9 and T18) (Figure 4e). The delayed gene expression pattern, coupled with the phenotypic alterations, suggested that the higher ambient temperature in CFG delayed the development of heading leaves via delaying the initiation of the heading transition.

In contrast to those genes with delayed expression, the SPL genes, which are commonly considered to be critical regulators of developmental timing (Chen et al., 2010), showed no significant expression alterations between CFP and CFG (Figure S10). Phenotypic observations found that the CFP and CFG plants varied little morphologically until the launch of the transition stage (Figures S1 and S8). This result indicated that the heading transition, influenced by the temperature, is independent from the well‐documented developmental phase transition. Meanwhile, we found that the important components in temperature sensing, phytochromes phyA and phyB, and transcriptional regulator PIF3 and PIF4, as well as related downstream genes, delivered delayed expression in CFG (Figure S11a). Among these genes, the ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)‐induced mutation lines of two BrPWR copies showed significant impairment of leafy head development (http://www.bioinformaticslab.cn/EMSmutation/home/; Table S10). Further examination in cabbage revealed that most of these thermo‐responsive genes were also activated in the transition stage of cabbage (Figure S11b). These results provided a hint that the temperature might be a conserved signal mediating the establishment or induction of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage.

Co‐expression networks highlighted connections among heading initiation pathways

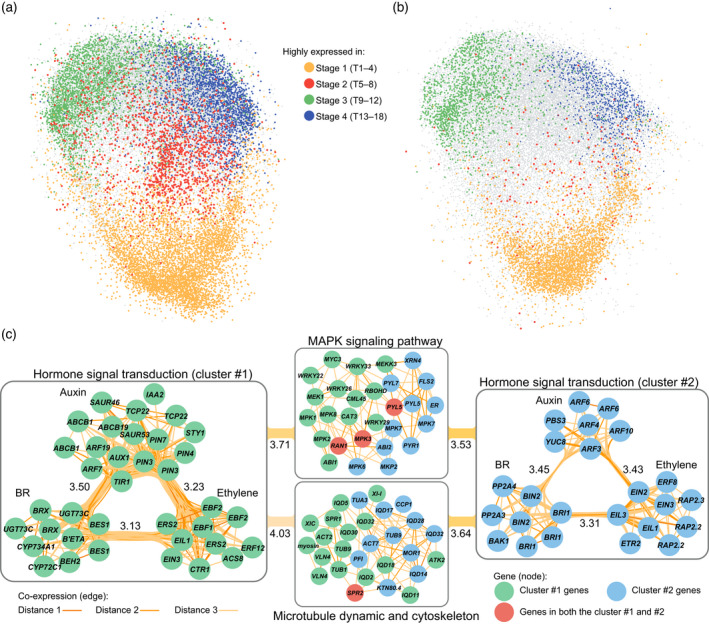

The functional associations among regulatory genes can be illustrated by their expression correlations among different developmental stages. An algorithm taking both the PCC and the mutual rank (MR) between genes into consideration was adopted for this co‐expression network construction. A network containing approximately 220 000 co‐expression pairs among 23 684 genes was obtained for Chiifu. As shown in Figure 5a, visualization of the network revealed that genes highly expressed in the same stage clustered together. Genes highly expressed in the transition stage, color‐coded red in Figure 5a, are located in the center of the network and many of them overlapped into other clusters, making it possible for them to reach, via interactions of products, other genes in a few steps (Figure 5a). The special, central position of these genes is consistent with a role in the initiation and regulation of leafy head formation. In contrast, genes in the rosette stage or the heading growth stage were more isolated from other stages. Investigation of the co‐expression network for non‐heading WS, our control, found little or no evidence of the centralization of genes highly expressed in the “transition” stage (Figure 5b). Once again, the Leaf Heading Transition Stage is heading‐specific and not a multipurpose gene regulatory stage.

Figure 5.

Co‐expressed gene clusters and pathways in the co‐expression network built for Chinese cabbage.

(a) Snapshot of the co‐expression network for Chiifu with genes highly expressed during different stages highlighted by different colors. Connections among genes (here as edge) and the isolated gene pairs were omitted. Visualization was conducted using the “preferred layout” in Cytoscape. (b) Snapshot of the co‐expression network for WS, the non‐heading control. The color of node was determined according to whether the genes marked with color in (a) were still highly expressed in corresponding stage in WS. If they did, these genes were colored same as in (a). If not, these genes were colored as gray. (c) Two triple‐hormones‐involved co‐expressed clusters are indicated by circles with different colors (green and blue). The color of genes in the MAPK and microtubule clusters were assigned according to the color of the hormonal cluster to which they connected in the network. Edge color indicates the value of the shortest path (distance) between two genes in the co‐expression network. Distance = 1 means that two genes are directly connected, while distance = 2 or 3 means that they were indirectly connected via one or two bridging intermediate gene(s), respectively. Numbers labeled beside the intra−/inter‐connections indicate the average distance between two gene clusters. Smaller numbers indicate closer connections. The gene prefix “Br” was omitted from the gene name. Owing to the abundance of multi‐copy genes in B. rapa, being descended from a recent hexaploidy event, genes marked with same name indicate different copies, such as the BES1s and EIN3s. BR, brassinosteroid. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The co‐expression network for leafy head differentiation provides a new way to explore potential gene regulatory relationships. We identified the closely connected genetic pathways through evaluating their distances in the network. Considering the remarkable transcriptional activation of phytohormone pathways, their associations with other pathways were inspected. We noticed that the ethylene pathway, with several key components identified as diagnostic genes (Figure 2e), had close relationships with multiple functional categories and pathways, including protein kinases and transporters (Figure S12). Intriguingly, ethylene pathway was connected to the BR pathway with many ethylene‐associated categories/pathways shared by both pathways. It was further found that the majority of genes in the BR pathway were also overwhelmingly activated in the transition stage of Chiifu (Figure S13), indicating the potential crosstalk between these two hormone genetic pathways in the heading transition process.

We also dissected the co‐expression relationships at the gene level. A subset of auxin genes that were upregulated beginning in the transition stage were co‐expressed, and they were intensively linked with the ethylene and BR pathways, forming a triple‐hormones‐involved co‐expression cluster (Figure 5c). In this cluster, BrPIN3s, BrPIN4, and BrPIN7, auxin transporter genes, stayed at the core connection and were co‐expressed with multiple ethylene‐ and BR‐related genes, suggesting that this hormonal crosstalk might regulate the PIN‐related polar auxin transport. Furthermore, another smaller cluster interacting with these three types of hormones was also identified (Figure 5c), in which the abaxial genes BrEINs, BrARFs, and BrBIN2s served as core nodes. Moreover, these interlaced clusters connected to the MAPK signaling pathway, the major members of which were MAPK cascade genes (Figure 5c). In addition, these clusters were also associated with genes involved in microtubule dynamics and the cytoskeleton. The cohesiveness among co‐expression clusters provided new clues on the interplay of different biological pathways, and suggested that the phytohormone ethylene might cooperate with auxin and BR, and participate in multiple biological processes to regulate the leafy head development of Chinese cabbage.

A co‐expression network of this sort is comparable with similar work of other laboratories, those studying leaf gene pathways in Arabidopsis, for example, or other species, and may identify new pathways as well (Figure 5c), such as the novel function of the ethylene pathway in the vegetative growth of Chinese cabbage. This new pathway was activated in the Leaf Heading Transition Stage.

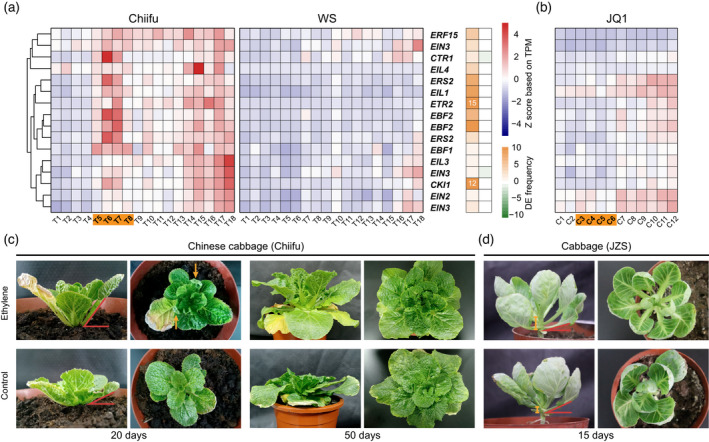

Ethylene pathway was launched by heading transition to initiate the leaf erectness in Chinese cabbage

We found that the ethylene pathway was highly activated starting from the transition stage of Chiifu blades. Almost all DEGs (15 of 16 genes) in the ethylene KEGG pathway, including the key components BrETR2, BrERS2s, BrEIN3s, BrEBFs, and BrEILs, showed a higher expression in Chiifu (Figure 6a; Table S11), and many of them showed sharp expression peaks constrained in the transition stage. Genes encoding protein in ethylene biosynthesis, such as BrACSs and BrACOs, and responsive factors, BrERFs, also exhibited a significant upregulated expression pattern (Table S11), suggesting an activation of ethylene pathway from the heading transition process. In contrast, the activation of ethylene pathway was not observed in Taicai (WS) (Figure 6a), the non‐heading control. Although many previous studies connected ethylene with fruit ripening and senescence, our results revealed its unexpected and specific role, which was association with the growth of the leafy head in the Chinese cabbage (both Chiifu and HN53). However, analysis in cabbage (JQ1) revealed that none of the key genes in the ethylene KEGG pathway were upregulated in its transition stage (Figure 6b).

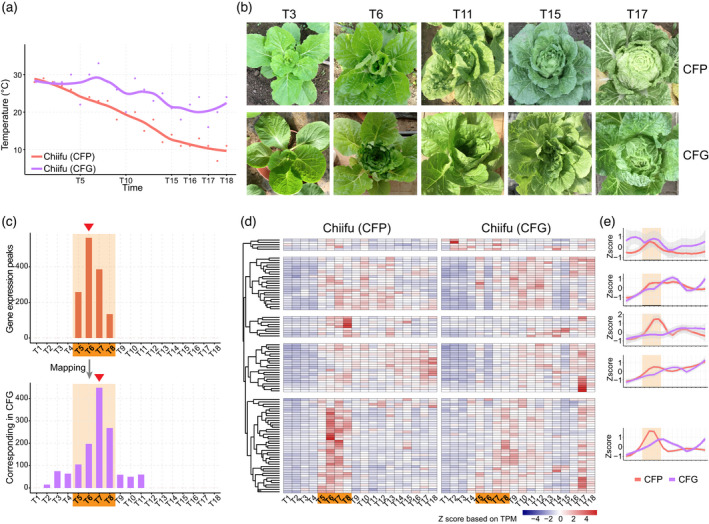

Figure 6.

Comparison of the performances of the ethylene pathway in the Chinese cabbage and cabbage.

(a) The majority of the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes‐annotated ethylene‐related genes were dramatically activated in Chiifu, while no similar phenomenon was found for WS. Right‐hand panel, small heatmap showing the frequencies of differentially expressed genes. The gene prefix “Br” was omitted from the gene name. The transition stage is marked by bold fonts on an orange background.

(b) Expression heatmap of the cabbage genes that were orthologous to those shown in (a). TPM, transcript per million.

(c) Phenotypes caused by the ethylene treatment on the Chinese cabbage Chiifu. The variations in leaf angle are highlighted by the red acute angles, while the incurved leaves are indicated by the yellow arrows. Photos were taken at 20 and 50 days after the ethylene treatment.

(d) Phenotypes caused by the ethylene treatment on cabbage JZS. The variations in internode length are indicated by the yellow lines. Photos were taken at 15 days after the ethylene treatment. [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Considering the distinct expressional behaviors of ethylene genes during the transition stages in Chinese cabbage and cabbage, we then conducted the ethylene treatment assay during the rosette stages of Chinese cabbage and cabbage. The results showed that the ethylene treatment induced the increase of leaf angle (horizontal) in Chinese cabbage, which resulted in the erect leaf and more compact plant architecture compared with the control (Figure 6c; Figure S14a). This effect probably extended to the leaf vein, as the young leaves treated by ethylene also exhibited clear incurved growing pattern. These features of leaf erectness highly resembled the common phenotype of heading leaves following the transition stage in Chinese cabbage. However, in cabbage, ethylene only led to the elongated internode and petiole, while the leaf angle stayed unchanged (Figure 6d; Figure S14a,b). Typically, leaf erectness is considered required during the formation of leafy head in Chinese cabbage rather than in the cabbage (Figure S14c,d). Therefore, the increase of leaf petiole angle promoted by the ethylene is likely to contribute to the leaf heading development of Chinese cabbage, but not in cabbage. The difference in ethylene genes between Chinese cabbage and cabbage were further supported by the genomic selection analysis using the resequencing data. Several heading transition‐activated ethylene genes including the biosynthesis‐related genes BrACS8 and BrACS4, as well as important regulators such as BrCTR1, BrEIN4, and BrEIL1 were under strong selection (evaluated by π) in the of Chinese cabbage population while only one gene BoACS8 was under selection in the cabbage population (Table S12). The results indicated that the ethylene pathway served as a specific artificial selection target in Chinese cabbage but not cabbage. Cabbage manages to head without the obvious upregulation of the ethylene pathway during the transition to heading.

DISCUSSION

Leaf heading is the most economically important trait of Chinese cabbage, cabbage, and other heading vegetables. Clarifying the regulating mechanism underlying this specialized leaf morphology could be of great value to both scientific and breeding research. In this study, we described the transcriptional landscape of the vegetative growth period in Chinese cabbage and cabbage, identified a temperature‐responsive regulatory transition stage, and revealed the unique upregulation of ethylene pathway genes, but only in heading morphotypes of Chinese cabbage.

High‐density time‐series RNA‐seq facilitated identification of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage

The emergence of the heading stage, as a unique growth stage, means that the heading crops experience a specific developmental transition. It is similar to juvenile‐to‐adult phase transition or the vegetative‐to‐reproductive phase transition (Huijser & Schmid, 2011), but only on the surface. Here it is the physiology of the whole plant, or at least the leaves, which dictate when leaves will transition to heading. Here, a transition stage was identified with the assistance of large‐scale transcriptomic data and leaf phenotypes. The heading transition emerged after the rosette stage, and was marked by the specific activations of hormonal and MAPK genes, as well as genes encoding transcription factors, which together indicated considerable transcriptional reprogramming. We showed that the developmental trajectory of heading and non‐heading morphotypes became transcriptionally different in the transition stage, before the adaxial overgrowth characterizing later stages. The transition stage is supported by leaf blade and petiole expression data from two morphotypes of Chinese cabbage. In addition, the Leaf Heading Transition Stage is conserved in the two Brassica heading crops. Notably, the longer but gentle transition stage in HN53 (Figure 3a–c), which coincided with its late‐maturing nature, suggested that the duration of heading maturity is closely associated with the duration of the transition stage. Furthermore, the transition stage affected by the ambient environment, and the postponement of the heading process under the greenhouse with higher temperature is most likely mediated by the delayed heading transition. These findings illustrated the crucial role of the transition stage in initiating the heading development by fueling transcriptional reprogramming, modifying both when heading occurs and how long it lasts.

We originally thought that the switch to heading during the Leaf Heading Transition Stage would be similar, to, or regulated by, the juvenile‐to‐adult phase change, or serve as a by‐product of this phase change. Actually, several BrSPLs did show divergent expression patterns between Chiifu and WS. BrSPL9 was highly upregulated in heading morphotypes compared with WS, corroborating a previous report that BrSPL9 regulates the earliness of heading (Wang et al., 2014, 9). However, none of these BrSPLs showed significant differences between Chiifu cultivars planted under different temperatures (Figure S10) even though the heading transition in greenhouse‐planted Chiifu was apparently delayed, suggesting that the progression of phase change in two environments was comparable. In addition, our sampling began at the rosette stage with the development of the early adult leaves according to the definition of developmental stages of Chinese cabbage in a previous study (Wang et al., 2014). Considering that the impact of BrSPL9 is accomplished through manipulation of the duration of the seedling and the rosette stages (Wang et al., 2014), these findings then supported the conclusion that the initiation of heading is not affected by the juvenile to adult phase change.

Signaling and origin of Leaf Heading Transition Stage

During the domestication (artificial evolution) of leaf heading, at least two very different sorts of “heading gene programs” are now known to exist. The first one refers to the program that responds to a signal. We conjectured that this signal originates from the fully differentiated and physiologically active rosette leaves and has a meaning “make a head.” This signal may travel from the leaves all over the leaf system. Given the independent “acquisition” of a Leaf Heading Transition Stage, and given that this stage of differentiation exists in not just leaf blades, but also leaf petioles, it makes sense that this special transition stage is, at least in part, a coadaptation to receive and transduce this “make a head” signal, and those sorts of genes upregulated during this transition stage fit this interpretation. The second program involves the origin of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage, and how such a domesticated trait could alter both leaf blade and petiole, two different components of the leaf. This co‐evolution makes it likely that the Leaf Heading Transition Stage derives from a phase of external signal reception followed by rapid transcriptional shifts among different organs. In this shifting regard, the heading transition resembles the juvenile‐to‐adult leaf transition (Yu et al., 2013). Here is one possible model to explain how plants of particular ages become competent to understand the “make a head” signal, and how this transcriptional stage is programmed into differentiating organs of the plant. Perhaps the commonality between leaf blade and petiole is a stage preceding rapid cell division or cell expansion, or both. So, the Leaf Heading Transition Stage specific to heading crops, was selected by breeders mainly for permitting heading. The process activates different organs of the plant to support the transition and the followed heading leaf growth. In other words, the whole plant may be modified to the heading leaf differentiation and growth. Further research using organ‐specific gene knockout mutations could test this hypothesis.

In addition, it is noteworthy that the evolutionary problem described here is to evolve a Leaf Heading Transition Stage “independently” multiple times for the various heading crops in Brassica, where the ancestral vegetative plant is moving directly from rosette leaves to flowering. This problem is similar to the “independent” evolution of C4 photosynthesis multiple times in the panicled grasses, where the ancestral state is known to be C3. The current model of convergent evolution considered that there were a series of mutations in homologous genes or different genes from common pathways served as genetic sources to the formation of similar traits in different species. It is possible as the Brassica species evolved from a paleo‐hexaploidization event, the retained multi‐copy genes accumulated rich mutations that could contribute to the gene functional differentiation and further the parallel evolution of heading traits in different Brassica crops. It could be exemplified by the multi‐copy BrBIN2s (Chinese cabbage) and BoBIN2s (cabbage) acting in the BR pathway, which showed distinct expression patterns and thereby were divided into different clusters in the expression heatmaps (Figures S13 and S15).

Heading transition initiated the ethylene pathway, upregulated during the Leaf Heading Transition Stage, could positively signal leaf heading in Chinese cabbage

Ethylene genes experienced an impressive expressional elevation during the transition stage of Chiifu. Studies revealed that frequent crosstalk between auxin and ethylene plays an important role in the root development and apical hook formation (Zemlyanskaya et al., 2018), while BR functions as indispensable player in the development of the apical hook (De Grauwe et al., 2005). We found that auxin flux carrier genes, auxin responsive genes, and gene module involving the auxin polar transport, as well as BR‐related genes were significantly activated in the transition stage of both Chinese cabbage and cabbage (Figures S13, S15–S17). These genes contributed to the appropriate spatial distribution of auxin, providing the prerequisite for asymmetric cell division and elongation, as well as for the much earlier establishment of adaxial–abaxial polarity (Du et al., 2018; Tian et al., 2018). Moreover, the ethylene‐driven petiole hyponasty, necessitating auxin and corresponding transport, also requires the involvement of the BR pathway, at least in Arabidopsis (Polko et al., 2013). Together, these studies highlight the importance of ethylene in modeling the asymmetric growth through forming tripartite hormone interactions, and what is true for Arabidopsis is likely, but not proved, to be true in Chinese cabbage. This hypothesis is supported by the erect‐leaf phenotype after ethylene treatment in Chinese cabbage, which is consistent with the petiole hyponasty found in Arabidopsis (Polko et al., 2011), and was further evidenced by the co‐expressed hormonal clusters and the unique selection of ethylene genes in the heading morphotypes of Chinese cabbage, but not in the non‐heading control.

In contrast, the cabbage showed no significant hyponastic response, nor the activation of genes in the ethylene pathway, nor the genomic selection of key ethylene genes. It is plausible that the ethylene pathway was not selected during the evolution of the heading trait in cabbage. Considering the generally round leafy head of cabbage, its petiole angle varies little before and after the heading stage, which is different from that of Chinese cabbage (Figure S14c,d). Moreover, the ethylene treatment showed an internode elongation effect in cabbage instead of leaf erectness found in Chinese cabbage. Long internode and petiole are distinctive in the wild B. oleracea, which grows much taller than cabbage. Moreover, it is known that the internode of cabbage in the rosette stage is much longer than that of Chinese cabbage, making the reduction of internodes critical for the appropriate launch of the heading particularly in cabbage. Thus, activation of the ethylene pathway would be reasonably counteractive for its heading process. Taken together, these adverse effects mediated by ethylene might explain why the ethylene pathway was not under selection in the heading of cabbage. The different phenotypic responses to ethylene, inducing leaf erection but not the elongation of internode in Chinese cabbage, while inducing the internode elongation but not the leaf erection in cabbage, observed here might be attributable to the different genetic backgrounds in Chinese cabbage and cabbage, which diverged about 4 million years ago (Liu et al., 2014). During the evolution and domestication processes, different adaptive strategies were likely to be adopted in these two species.

Based on this information, we infer that the flexible roles of the ethylene pathway in Chinese cabbage and cabbage reflect the independent domestication of these two heading crops, highlighting the significant variation that must have fueled the parallel selection of the heading traits.

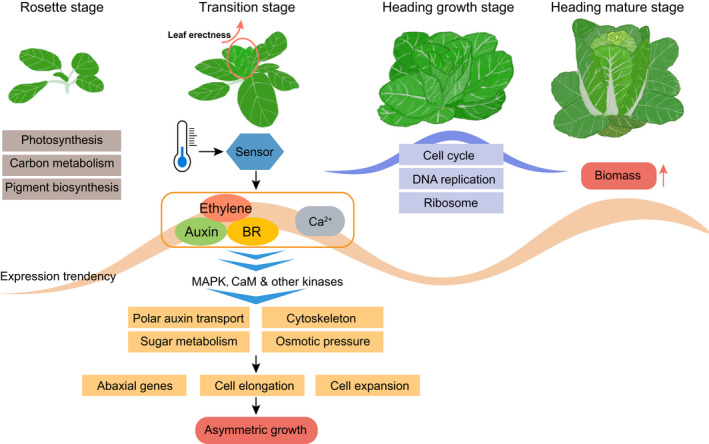

A hypothetical regulatory model may explain the heading differentiation process

We compiled an integrated regulatory model (Figure 7), in an attempt to explain the initiation of the head formation, and to depict the biological mechanisms underlying the growth stages. Generally, strong photosynthesis, pigment biosynthesis, and many other primary metabolisms reigned in the rosette stage. However, most of these photosynthetic functions vanished by the end of the rosette stage. Instead, distinct gene categories were activated in the following Leaf Heading Transition stage. Although extensive experiments need to be performed to confirm the key causal factors initiating the developmental transition, the behaviors of Chiifu under higher temperatures, accompanied by the expression alterations of thermo‐sensor genes, provided important clues. Chinese cabbage and cabbage are sensitive to high temperatures and the formation of the leafy head would be greatly affected by them (≥25°C) (Opena & Lo, 1979). Therefore, a drop in temperature possibly serves as a primary stimulus (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Hypothetical regulatory model to help explain the transcriptional dynamics during the heading differentiation process in Chinese cabbage.The rosette stage is accompanied by enhanced photosynthesis and many other primary metabolisms. The transition stage (our primary contribution to this discussion), in which the development of the folding and erect leaf begins, is considered a particularly important stage. Exogenous stimuli, such as low temperatures, are, hypothetically, sensed by sensor proteins. Plant hormones and second messenger Ca2+ are then activated, and the signals of which are transmitted and magnified through the MAPK signaling pathway and other kinases such as CaMs. These enhanced signals triggered many biological processes and promoted the asymmetric growth of leaves in which essential adaxial and abaxial identities have already been set. In the heading growth stage, many growth‐related processes were activated (indicated by the purple ribbon). In the heading mature stage, the re‐enhanced hormonal pathways (indicated by the light orange ribbon), promoted the formation of the leafy head and boost biomass. BR, brassinosteroid.

We speculate that the interplay among ethylene, auxin, and BR plays a definitive role in the appropriate initiation of heading leaf formation in the Chinese cabbage (Figure 7). These hormone signals and other intracellular signals are transmitted and amplified through the MAPK pathway, and other potential kinases (Figure 7). Subsequently, comprehensive changes, including the high expression of abaxial genes, the reorganization of microtubules (Figure S4), and that further activates cell division, cell expansion, and bending. The remodeling in cell morphogenesis leads to the asymmetric growth, which is essential for the leafy head formation. Notably, the activation of the ethylene pathway in the transition stage increases the petiole angle and results in the erect leaf; leaf posture is a distinguishable character of the developmental transition in Chinese cabbage. After the transition stage, the enhanced cell proliferation and activation of growth‐related genes in the subsequent heading growth stage provides the prerequisite for the rapid growth in the last heading mature stage, the latter of which is accompanied by the recalibration of hormone‐related genes that might contribute to the rapid increase of leaf size and the accumulation of biomass (Figure 7).

In conclusion, we identified a conserved regulatory Leaf Heading Transition Stage that is central (in the leaf transcriptional expression network) for vegetative growth in two Brassica heading crops, but is absent in the non‐heading control. Therefore, this new transition stage is specific to heading. Manipulation of this stage will probably be shown to determine the earliness of heading time and affect the quality of the leafy head. The identification of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage facilitated the prediction of heading‐regulating genes, and thereby paves the way for further in‐depth functional dissection of the molecular mechanism regulating the heading trait. The “make a head” signal, hypothetically originating in mature rosette leaves, and hypothetically being received and transduced in leaf cells in the Leaf Heading Transition Stage, is a research opportunity. Large‐scale transcriptomics can only go so far. The future of leaf heading research will require both genetics and molecular biology, and we hope comparative genomics will point the way.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant materials, cultivation, and sample collection

Three morphotypes of B. rapa, including Chiifu, HN53, and WS, were used in our field experiment. About 200 Chiifu, 100 HN53, and 100 WS seeds were sown into the potted trays in the greenhouse. After 2 weeks, most of the seedlings were planted into ground in the plastic shed, while 100 Chiifu seedlings stayed in the greenhouse. The first sample collection process began 25 days after sowing (six‐leaf stage). For the regular sampling, leaf was collected by tearing off the inner visible third leaf (approximately 5 cm long), and the petiole was then clipped from the leaf. The separated leaf blade and petiole were put into individual aluminum foil bags and were then flash‐frozen in liquid nitrogen. Leaf blade and petiole were collected twice each week (once every 3 or 4 days; Table S13). In the last 3 weeks, the size and head shape of Chiifu were generally stabilized. Therefore, the sampling frequency of leaf organs was reduced to once per week. In addition, about 30 cabbage JQ1 seedlings were planted into the field, and the leaves were collected following the regular sampling process used in the Chinese cabbage. The sampling of cabbage leaves began 25 days after sowing (six‐leaf stage) and ended at the time when the heads stabilized (approximately 65 days after sowing). The cabbage leaves were collected about twice each week, and the frequency was slightly adjusted to avoid the inclement weather. Each plant was used only once for a single leaf harvest. All of the samples were collected with three biological replicates, except for those that failed the sampling or the sequencing processes. All of the collected samples were stored at −80°C.

RNA extraction, sequencing, and processing of RNA‐seq reads

The mRNA was extracted using the Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Library construction was conducted using the VAHTS mRNA‐seq v2 Library Prep Kit for Illumina according to the instructions of the manufacturer. The libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq platform at Berry Genomics Beijing Co., Ltd, Beijing, China. For the mRNA‐seq data of B. rapa morphotypes, the latest genome version (v3) of Chiifu was used as the reference genome (Zhang et al., 2018), and the updated gene annotation (v3.1, available at http://www.bioinformaticslab.cn/pubs/heading/BrapaV3.1/) was used for gene expression quantification and following analyses. For data of the cabbage JQ1, the latest reference genome JZS version (v2) and the corresponding gene annotation were used (Cai et al., 2020). The raw 150‐bp paired‐end RNA‐seq reads (approximately 6 Gb data per sample) were filtered and trimmed using Trimmomatic (Bolger et al., 2014) with default parameters. Hisat2 (Kim et al., 2019) and FeatureCounts (Liao et al., 2014) were used to align reads to the reference genome and to report the read counts for each gene, respectively. FeatureCounts was run with parameter “‐Q 5” to filter low‐quality alignments. On average, 21.43 million reads were generated for each B. rapa sample, and 91.34% of them could be aligned to the reference genome Chiifu. Whereas for B. oleracea samples, 22.95 million reads were generated on average, and 91.29% of them could be aligned to JZS genome. The TPM values were calculated using a local Perl script that is available upon request.

Quality control for RNA‐seq replicates

The Spearman’s correlation coefficient (SCC) values among replicates were calculated using R, and the average SCC values were calculated to evaluate the quality of sample. Samples with average SCC values ≤0.85 were manually checked to remove the low‐quality replicates. Consequently, the expression profile of one B. rapa biological replicate was discarded due to its low correlations with other replicates (Table S14). Principal component analyses were conducted based on the transformed TPM values (log2 (TPM+1)) using the function “prcomp” in R. One replicate (outlier) was then excluded due to its significant deviation from other samples, with identical tissue attributes in the principal component analysis plot (Table S14). The average correlation coefficients among the retained biological replicates were 0.9554 and 0.9735 for B. rapa and B. oleracea samples, respectively. For each sample, the average TPM values of different replicates were considered the expression value of genes. Only genes with maximum TPM ≥2 and median TPM ≥0.01 across the time‐series data were retained for most following analyses.

Clustering of the time‐series gene expression profiles

In the sample clustering analysis for Chiifu and WS, we selected the last 10 000 genes with limited expression variation according to the order of coefficient of variation (CV) of transformed TPM to reduce the potential dominant effect caused by genes with extremely high expression fluctuation. We then selected the top 5000 highly expressed genes from the 10 000 genes ordered by the median value of transformed TPM. Samples were clustered based on a (1−PCC) distance matrix using the “hclust” function in R.

Stage‐based functional enrichment analysis

To characterize the stages identified through the clustering analysis, we determined the genes showing elevated expression level in certain stage. The 18 time points were divided into three parts (depending on the stages described in Results and in Figure 2a) and the averaged expression values in each part were calculated to simplify the data complexity. For example, if the target stage was set as the transition stage (T5–8, II), these 18 time points were divided as T1–4, T5–8, and T9–18. If the target stage was set as the heading growth stage (T9–13, III), these time points were divided as T1–8, T9–13, and T14–18. Then, TCseq was used to cluster genes with similar expression patterns based on the resultant gene expression matrix, which contained the averaged TPM in each part for each gene. In particular, gene clusters that showed a higher expression in the target part were selected and subjected to enrichment analyses. As for WS, similar analyses were conducted with the target part set as T5–8 and a discontinuous series (T3, T4, T6, T7, T8, and T10 based on the clustering result for WS) to simulate the transition stage found in Chiifu.

DEG analysis

DEGs between any two time points were calculated by the “DESeq2” in R (Love et al., 2014). An “all vs. all” approach was applied for all of the time points included in the time‐series gene expression profiles. Genes with ¦fold‐change≥2 and q value ≤0.01 were considered DEGs. To distinguish the transition stage (T5–8) from other stages in Chiifu, particularly the heading growth stage (T9–13), we selected the DEGs that were significantly upregulated during T5–13 relative to both the rosette stage (T1–4, four time points as a pool) and the heading mature stage (T14–18, five time points as a pool) based on the blade transcriptomes. In total, 77 DEGs were obtained and used to conduct the heatmap analysis. Among them, 22 genes, which were clustered together and were upregulated specifically in the transition stage (Table S3), were annotated and were further used for examining whether the transition stage exists in the non‐heading WS.

Identification of the RGs at each time point

The RGs were identified for each time point based on the DEGs. RGs for certain time points should meet the following criteria: the expression value of the gene at this time point was greater than that at 80% of time points (18 × 80% ≈ 14), two‐fold greater than 40% of them (18 × 40% ≈ 7), and significantly (means differentially expressed) greater than 20% of them (18 × 20% ≈ 4). Meanwhile, there was no sample with a significantly higher expression value than this sample. Therefore, one gene could be considered as an RG of up to four time points.

Construction of the functional gene modules

Two methods were used to generate a gene set, which were upregulated during the transition stage of Chiifu while not in WS, for the construction of the functionally associated gene modules. First, DEGs that were exclusively upregulated in the transition stage of Chiifu relative to WS were identified. DEGs between the blade transcriptomes of Chiifu and WS were called and categorized into three types according to their frequencies: DEGs with frequency <3 assigned as “random,” DEGs with frequency >15 as “basic,” and other DEGs. The random DEGs might be caused by the unreliable gene expression variations, while the basic DEGs present the constant variations that might reflect the genetic divergence between morphotypes. Both the two types of DEGs were filtered out, and only the retained DEGs were used. In total, 54 genes that were identified as DEGs (frequency ≥2) in the transition stage but not in any other stages were obtained (Table S6). Second, we determined the genes showing divergent expression patterns in the transition stage between Chiifu and WS. The PCC for each expressed gene between Chiifu and WS based on their transformed TPM values was calculated. Then, we masked a certain stage from the four stages and recalculated the PCC iteratively. The original PCC and the PCC values after masking were compared to judge whether the correlation increased or decreased after the expression data in this stage were masked. Genes with the decreased PCC values in the transition stage (PCCoriginal – PCCtransition‐stage‐masked ≥0.15) were selected. These genes were further filtered, and only those that were also identified as DEGs (frequency ≥2, not exclusively) in the transition stage were retained (264 genes in total; Table S15). These two gene sets were merged to obtain a set of “seed genes.” These seed genes were annotated, and the potential functional associations among genes were explored through a literature search.

Definition of the diagnostic gene markers for the transition stage

To examine the existence of the Leaf Heading Transition Stage in other morphotypes or species in addition to the heading morphotype Chiifu, we defined a set of diagnostic gene markers, during which both the expression pattern and the functional involvement of genes were considered. First, we included the aforementioned 22 genes that were upregulated specifically in the transition stage based on the heatmap analysis, as they exhibited a distinctive expression pattern in the transition stage. Second, the seed genes in three functional modules (13 genes; Table S7; Figure S4b–d) were also included, considering that they represented the functional activities that were activated during the transition stage. These genes were merged as the final diagnostic gene markers for the transition stage.

Identification of orthologous genes involving in important pathways

We used the SynOrths (Cheng et al., 2012) tool to identify the syntenic genes between B. rapa and A. thaliana, between B. oleracea and A. thaliana, and between B. rapa and B. oleracea. The orthologous gene maps were built for converting the known functional annotations in A. thaliana to B. rapa and to B. oleracea. For important individual genes and gene categories such as genes involved in the hormone pathway or in the abaxial–adaxial patterning, we manually checked the gene mapping results and corrected potential errors with the assistance of BLAST‐based reciprocal best hits. Because the hormone‐related genes annotated by KEGG are incomplete, extended gene sets were generated by collecting genes involved in the homeostasis and regulation of these phytohormones that were not included in the KEGG annotation. Notably, for exploring the transcriptional pattern of the transition stage in HN53, only the KEGG‐annotated hormone‐related genes and MAPK‐related genes were used to exclude the potential bias caused by the manual collection of genes.

Analyses of the time‐series mRNA‐seq data for cabbage JQ1

Because of the limited sample numbers in cabbage, DEGs relative to the rosette stage of cabbage (C1–C2) were identified and were used for the enrichment analyses. For the diagnostic gene markers identified in Chiifu, their orthologous genes in B. oleracea were identified based on the SynOrths‐based gene map. Owing to the lack of the mRNA‐seq data of the non‐heading B. oleracea morphotype, the B. oleracea genes were judged as activated or not based on whether their expression levels elevated in the transition stage compared with those in the rosette stage. The judgement was conducted based on the gene expression clustering results followed by manual check. For hormone‐related genes, we investigated whether they were shared by the Chinese cabbage and cabbage, i.e. whether the orthologous gene pair were activated in the transition stages in the respective species. In particular, to avoid the discrepancy caused by the methodology, we also re‐judged the activation status of B. rapa genes using the aforementioned judging method. The extended gene set for phytohormone pathways in addition to the ones annotated by KEGG were used for comparing the overlaps of activated genes between the Chinese cabbage and cabbage. Permutation tests were performed to calculate the P values by comparing the observed overlaps with expected overlaps based on 10 000 randomized sampling.

Identification of expression peak variations between CFP and CFG

The above‐described RGs at each time point meant that genes were highly expressed at this time point. However, a gene could be identified as an RG in two adjacent time points. In this case, the time point with relatively low expression could be falsely considered as an expression peak, the explicit determination of which is the prerequisite to identify the expression shift between CFP and CFG. Thus, we developed another method to identify the expression peaks. Expressed genes with maximum TPM ≥2 and median TPM ≥0.01 were subjected to the identification process. To reduce the expression fluctuation, a sliding window with size = 3 and step = 1 was used to calculate the average TPM in each window, which was then designed as the averaged TPM at each time point. We only focused on those time points with averaged TPM ≥median value and ≥mean value. Adjacent or near expression peaks (distance = 3) were compared and only the peak with the highest value in these clusters was retained. Resultant candidate peaks were then compared. Only ones greater than the 50% of the highest peaks and with averaged TPM ≥2 were kept. Finally, we checked the region around the candidate peak (three samples on the left and three samples on the right) and calculated the CV and range of samples in this region. Only peaks with CV ≥0.15 or range ≥30% of the peak were considered the expression peaks of genes. This method guaranteed that every peak was steep enough as compared with adjacent time points, and stayed away from other peaks. Therefore, multiple peaks of a certain gene could not disturb the judging process that determined whether the peak was delayed in CFG. Based on the identified peaks, genes that displayed delayed peaks in CFG were predicted with the maximum searchable distance set as 3 or 5. Among the delayed genes (distance = 3), genes that were identified as upregulated DEGs (frequency >2) in the comparisons between CFP and WS were summarized in Table S8.

Ethylene treatment assay

Plants were cultivated in the incubator under the long‐day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark) at 20°C. Hoagland's nutrient solution was applied to support the growth. Ethephon (2‐chloroethyl phosphonic acid) at 300 μl L−1 concentration was sprayed with a hand sprayer on the leaves at the rosette stage (approximately seven leaves for Chinese cabbage; approximately nine leaves for cabbage). The control group was sprayed with deionized water. Surfactant teepol (0.5%) was used as the wetting agent for both the ethephon treatment and control groups. The treatments were arranged in a randomized block design and the number of replicates for each treatment was three.

Genomic selection in the heading population of Brassica rapa and Brassica oleracea

We used the genome resequencing data of 199 B. rapa and 119 B. oleracea accessions generated in our previous study (Cheng et al., 2016) to identify the genes under the selection in the heading population compared with the non‐heading ones. The resequencing data were aligned to the reference genomes and the variants were called using the BWA (Li, 2013) and GATK (McKenna et al., 2010), respectively. Variants were then filtered using the VCFtools (Danecek et al., 2011) with the parameters of “‐‐maf 0.05 ‐‐max‐alleles 2 ‐‐min‐alleles 2 ‐‐minDP 3 ‐‐minQ 30 ‐‐max‐missing 0.5.” The nucleotide diversity (π) of genes (upstream and downstream 3 kb included) was calculated using the VCFtools for the heading (πH) and non‐heading (πNH) populations, and the activated ethylene‐related genes with reduced π values (top 10% of πH/πNH) in the heading populations were identified in B. rapa and B. oleracea.

Exploitation of the Chinese cabbage mutation population

A Chinese cabbage mutation population generated by EMS mutagenesis of a heading morphotype A03 was used to screen the genes that might functionally contribute to the formation of the leafy head. The genotypes and corresponding phenotypes of mutant lines were obtained from http://www.bioinformaticslab.cn/EMSmutation/home/. The orthologous genes between Chiifu and A03 were identified using SynOrths. Mutants carrying the significant mutations such as non‐sense and non‐synonymous mutations of these genes were identified, and those with affected heading phenotypes were further determined using the local Perl script (available upon request).

Construction of the co‐expression networks

For the expression data of Chiifu leaves, we built a PCC matrix containing all possible gene pairs using R based on their normalized TPM values. Rather than extracting the gene pairs with the top PCC values, we adopted an algorithm based on the MR of PCC, which has been used in the construction of several important co‐expression databases such as ATTED‐II (Obayashi et al., 2018). This algorithm and corresponding parameters were comprehensively described and discussed in a previous study (Obayashi & Kinoshita, 2009). In particular, we kept the pairs with MR top3 or MR ≤30, together with PCC ≥0.84 (top 5% of the PCC values of all positive co‐expression gene pairs). A co‐expression network was also built for WS using the same method.

The node degree and shortest path length (distance) between any two nodes were calculated using the “igraph” package in R. To interpret the potential associations among individual genes/pathways based on the co‐expression network, the shortest path length, i.e. the distance, between two nodes was used as a proxy to evaluate their co‐expression level. Aside from those directly connected gene pairs in the network (distance = 1), gene pairs that were indirectly connected with relatively short distances also could be co‐expressed. Based on this principle, the co‐expressed gene pairs from different functional categories such as auxin and BR pathways were identified through searching the pairs with distance ≤4. Then, a distance matrix was built for the retained gene nodes, in which the value represented the distance between any two nodes. Finally, the co‐expressed clusters were determined by extracting those gene pairs that were clustered together in the resultant matrix.

To build the network‐based associations between KEGG pathways, we selected the KEGG pathways that were enriched during the RG analyses as targets. For simplification, only DEGs in KEGG pathways were retained, and only pathways containing ≥10 DEGs (Chiifu vs. WS) were kept for the following analyses. We calculated the distance matrices between any two pathways in an “all vs. all” manner. Each pathway was queried against all other pathways (target pathway), and the gene pairs with the distance ≤4 were counted. Then, we constructed 100 randomized pathways that shared the same gene number with the target pathway but were comprised of genes that were randomly selected from the co‐expression network. Similarly, we counted the gene pairs with the distance ≤4 in each comparison, and considered the result as a sampling. Based on those results, we determined the significance level by comparing the authentic counts with the randomized ones using a T‐test. Iteratively, we obtained the significance levels for all pathway pairs, each of which contained two P values, as each pathway served as both query and target. Finally, pathway pairs with both P ≤ 0.01 were considered as associated pathways.

Enrichment analysis of gene sets