Abstract

Tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a proinflammatory cytokine, is a crucial mediator of psoriasis pathogenesis. TNF-α functions by activating TNF-α receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNFR2. Anti-TNF drugs that neutralize TNF-α, thus blocking the activation of TNFR1 and TNFR2, have been proven highly therapeutic in psoriatic diseases. TNF-α also plays an important role in host defense; thus, anti-TNF therapy can cause potentially serious adverse effects including opportunistic infections and latent tuberculosis reactivation. These adverse effects are attributed to TNFR1 inactivation. Thus, understanding the relative contributions of TNFR1 and TNFR2 has clinical implications in mitigating psoriasis versus global TNF-α blockade. We found a significant reduction in psoriasis lesions as measured by epidermal hyperplasia, characteristic gross skin lesion and IL-23 or IL-17A levels in TNFR2 knockout (TNFR2KO), but not in TNFR1KO mice, in the imiquimod psoriasis (IMQ) model. Further, IMQ-mediated increase in the myeloid dendritic cells (MDC), TNF/iNOS producing DC (Tip-DC) and IL-23 expression, in the draining lymph nodes were dependent on TNFR2, but not TNFR1. Together, our results support that psoriatic inflammation is not dependent on TNFR1 activity but driven by a TNFR2-dependent IL-23/IL-17 pathway activation. Thus, targeting the TNFR2 pathway may emerge as a potential next generation therapeutic approach for psoriatic diseases.

INTRODUCTION

TNF-α is a key signaling protein in the regulation of adaptive and innate immune system and functions by activating TNFR1 and TNFR2. There are common and distinct roles for the two receptors; TNFR1 is proinflammatory and has a major role in immune defenses, whereas TNFR2 is linked to inflammation, immune cell proliferation and survival (Chandrasekharan et al., 2007, Faustman and Davis, 2013, Sedger and McDermott, 2014). Anti-TNF therapy, although highly effective in treating immune-mediated inflammatory diseases, including psoriasis is associated with an increased risk of major side effects such as opportunistic infections, reactivation of latent tuberculosis, certain malignancies and limited responsiveness (up to 40% of patients do not respond) (Cordoro and Feldman, 2007, Finckh et al., 2006, Gottenberg et al., 2016, Sedger and McDermott, 2014). Preclinical studies show TNFR1KO mice succumb to more infections compared to WT, whereas TNFR2KO mice do not show this effect (Peschon et al., 1998, Rothe et al., 1993, Wroblewski et al., 2016). Also, TNFR1-meditated apoptosis of immune cells, which is required for maintaining a stable granuloma, is critical for preventing latent tuberculosis from reactivation (Tsuji et al., 1997). Other adverse effects, including malignancy attributed to aberrant immune reactivity, are implicated specifically to the inhibition of TNFR1-mediated apoptosis (Solovic et al., 2010). Unlike TNFR1, TNFR2 lacks death domains in its cytosolic region and, therefore, does not induce classical apoptotic pathways (Chen and Goeddel, 2002, Vandenabeele et al., 1995). Contrarily, TNFR2, but not TNFR1, induces immune cell activation/proliferation (Chen et al., 2007, Tartaglia et al., 1991) and neoangiogenesis (Goukassian et al., 2007, Pan et al., 2002, Zhang et al., 2003), processes that are known to drive psoriasis pathogenesis.

In plaque psoriasis (hereafter, psoriasis), increased keratinocyte proliferation in the epidermis leads to a disease manifestation with scaly, erythematous plaques. Studies suggest that during the initiation phase of psoriasis, activated skin dendritic cells drain into lymph nodes and drive differentiation of naïve T cells to TH17 and TH1cells (Nestle et al., 2009). The TH17 and TH1 cells subsequently infiltrate into psoriatic skin via the circulation. In skin, the infiltrated TH17 and TH1 cells secrete additional inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and growth factors including TNF-α, CXCL10, CXCL11, interferons and the interleukin (IL)-17 family of proteins. The abundance of cytokines and growth factors activate various dermal cells driving proliferation and incomplete terminal differentiation of keratinocytes leading to psoriatic plaque formation (Nestle et al., 2009).

In this study, using the imiquimod (IMQ) mouse model (van der Fits et al., 2009), in which application of IMQ to the skin of otherwise healthy mice induces psoriasis-like lesions, we found TNFR2, rather than TNFR1 plays a prominent role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis-like inflammation via activating IL-23/17 pathways.

RESULTS

IMQ-induced epidermal thickness was reduced in TNFR2KO, but not in TNFR1KO mice.

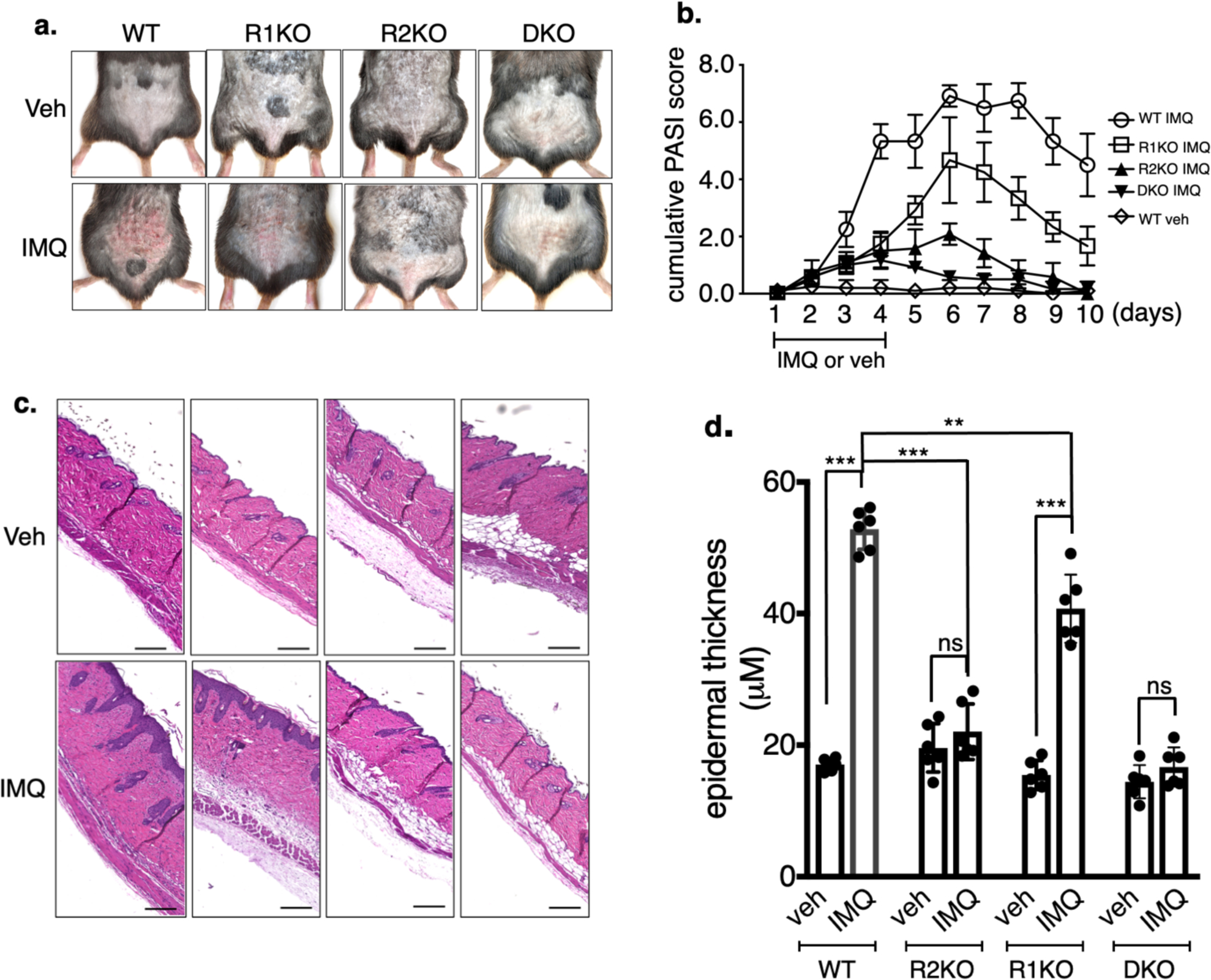

Upon IMQ application, wild type (WT) and TNFR1KO mice that received IMQ developed skin lesions reminiscent of psoriasis, whereas TNFR2KO and TNFR1;TNFR2-double knockout (DKO) mice showed minimal plaque lesions (Figure 1a). Cumulative Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) scores peaked at day 6 following initiation of IMQ application in WT mice (Figure 1b, 6.9 ± 0.40) and 4.67 ± 1.5 in TNFR1KO mice. Notably, effect of IMQ on TNFR2KO mice (PASI, 2.1 ± 0.38, p < 0.001) or DKO mice (PASI, 0.58 ± 0.2, p < 0.001) was minimal compared to IMQ-treated WT.

Figure 1. IMQ-induced epidermal thickness is reduced in TNFR2KO, but not in TNFR1KO mice.

a. Dorsal area of the mice of indicated genotypes were shaved and IMQ was applied once every day for four consecutive days. Picture of the IMQ-treated region was taken on day 5. b. Cumulative PASI score (Erythema + scaling + skin thickness) of mice treated with IMQ in a separate set of experiments. Each value in the PASI is the Mean of 4 independent scores of each mouse at each time point were recorded in a double-blinded fashion (n = 6; mean ± SEM). c. H&E-stained skin sections. Scale bar, 125 μm. d. Epidermal thickness induced by IMQ was quantified by Image-Pro software. (n = 6; mean ± SEM, student t test), ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01. ns = not significant.

Histologic examination followed by image quantification shows an increase in keratinocyte hyperplasia in the lesional skin of WT and TNFR1KO upon IMQ treatment (Figure 1c & d). IMQ treatment resulted in a ~3-fold increase in epidermal thickness in lesional WT skin (p < 0.001). There was no significant increase in epidermal thickness in TNFR2KO mice or DKO (mice, whereas TNFR1KO showed significant increase in epidermal thickness (p < 0.001). However, compared to IMQ-treated WT skin, IMQ-treated TNFR1 skin showed less epidermal thickness (p < 0.01), suggesting a minor contribution of TNFR1 in IMQ-mediated skin hyperplasia, compared to TNFR2.

IL-17A and IL-23 gene induction in IMQ-treated mice skin is TNFR2-specific.

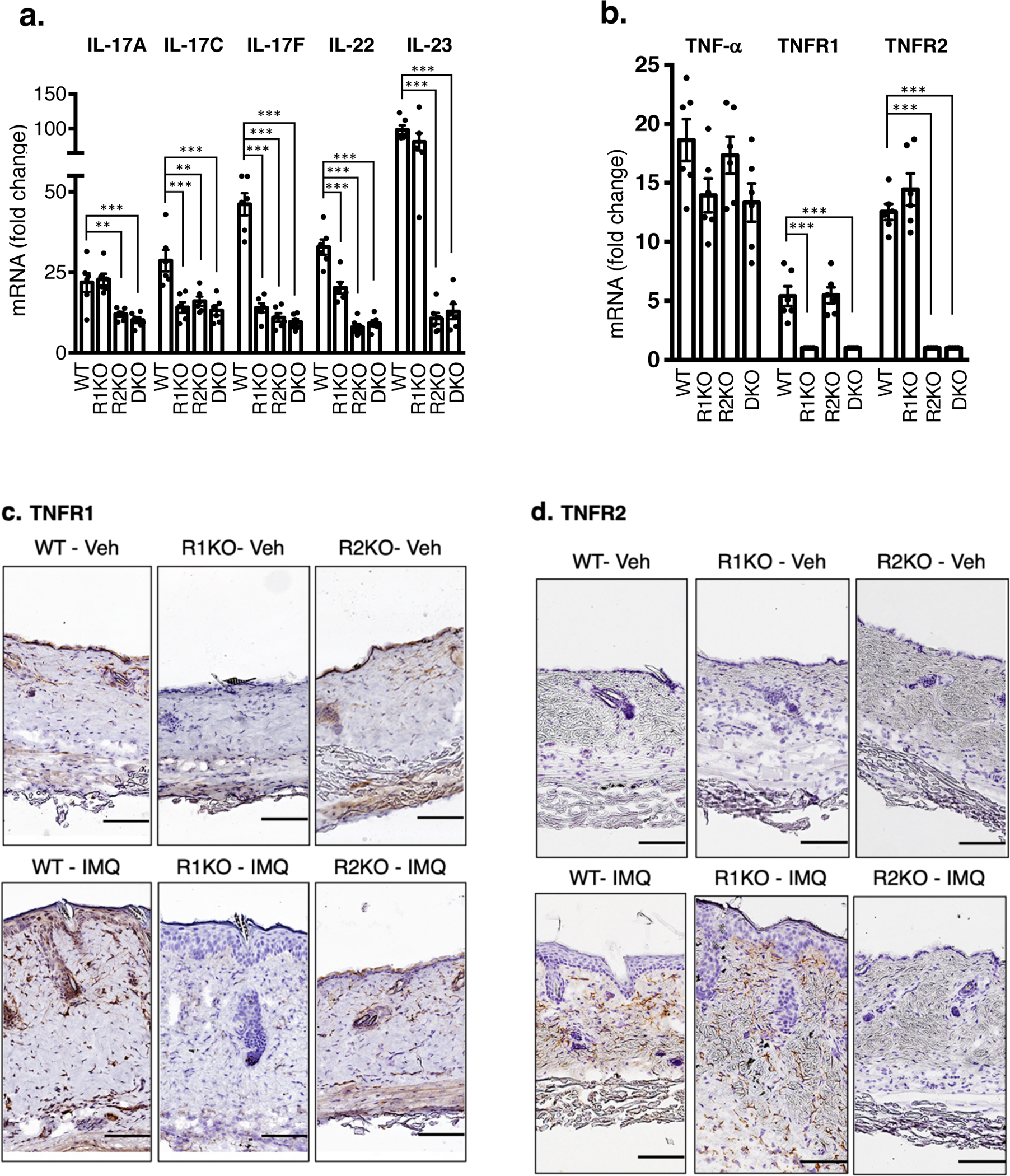

IMQ-mediated psoriatic disease is dependent on the IL-23/IL-17 axis (van der Fits et al., 2009). As expected, mRNA levels of IL-17 family of genes and genes encoding IL-22 and IL-23 were upregulated many-fold in IMQ-treated WT skin (Figure 2a). Importantly, IMQ-mediated IL-17A and IL-23 gene induction were predominantly dependent on TNFR2 activity (p < 0.001) but not due to TNFR1. The DKO showed similar inhibitory effect as TNFR2KO on the expression of these genes. IMQ induction of IL-17C, IL-17F and IL-22 was inhibited significantly in TNFR1KO (p <0.001) and TNFR2KO mice (IL-17C, p < 0.01; IL17F & IL-22 p < 0.001). Similar to IL-17A and IL-23, chemokines CXCL10 and CXCL11 induction requires TNFR2, not TNFR1 (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 2. IMQ induction of psoriasis-related genes are differentially regulated in the skin of TNFR1KO vs TNFR2KO mice.

Total RNA from IMQ-treated (4 days of IMQ treatment) or vehicle-treated skin was isolated from WT or indicated TNF receptor knockout mice. Quantitative PCR was performed to determine the abundance of mRNA. a. IL-17A, IL-17C, IL-17F, IL-22 and IL-23. b. TNF-α, TNFR1, TNFR2. Results expressed as fold mRNA change compared to vehicle-treated skin of mice with respective genotypes. (n = 6; mean ± SEM, ANOVA), ***p < 0.001, **p < 0. 01. Immune-stained TNFR1 (c) and TNFR2 (d) proteins in the skin isolated from vehicle-treated WT or IMQ-treated WT, TNFR1KO, TNFR2KO mice. Scale bar, 125 μm. e. TNF-α levels were measured by ELISA (R&D systems) after the skin tissue was homogenized in PBS containing 0.1% nonionic detergent. n = 6; mean ± SEM, ANOVA, ***p < 0.001. ns = not significant.

Deletion of TNFR1 gene did not alter TNFR2 expression and vice versa (Figure 2b). Immunohistochemistry studies show TNFR1expression, as expected, is ubiquitous including in the keratinocytes in both untreated and IMQ-treated conditions (Figure 2c). Interestingly, TNFR2 expression appears to be limited to infiltrated leukocytes and vasculature, but not in keratinocytes (Figure 2d). However, one study showed an upregulation of TNFR2 expression in keratinocytes upon IMQ in mice (Peng et al., 2018). These discrepancies in TNFR2 expression can be due to differences in the mouse strains (our C57Bl/6 vs their BALB/c mice) and IMQ dose (our 4 days vs their 7 days).

TNF-α mRNA induction in response to IMQ was similar in the skin tissues of WT, TNFR1KO and TNFR2KO mice on day 4 (Figure 2b, left panel), however, TNF-α protein level was lower in TNFR2KO skin compared to WT or TNFR1KO (p < 0.001, Figure 2e).

Our enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) demonstrates that circulating IL-17A, CXCL10, CXCL11, IL-10 and IFN-α levels were upregulated largely in a TNFR2-, but not TNFR1- dependent fashion in response to IMQ (Supplementary Figure S2a–e). TNF-α in the blood was increased independent of TNFR1 or TNFR2 (Supplementary Figure S2f).

TNFR2 depletion, but not TNFR1 depletion reduces infiltrated TH17 cells, IL-17A protein, dendritic cell populations, and neoangiogenesis in IMQ-treated mice skin.

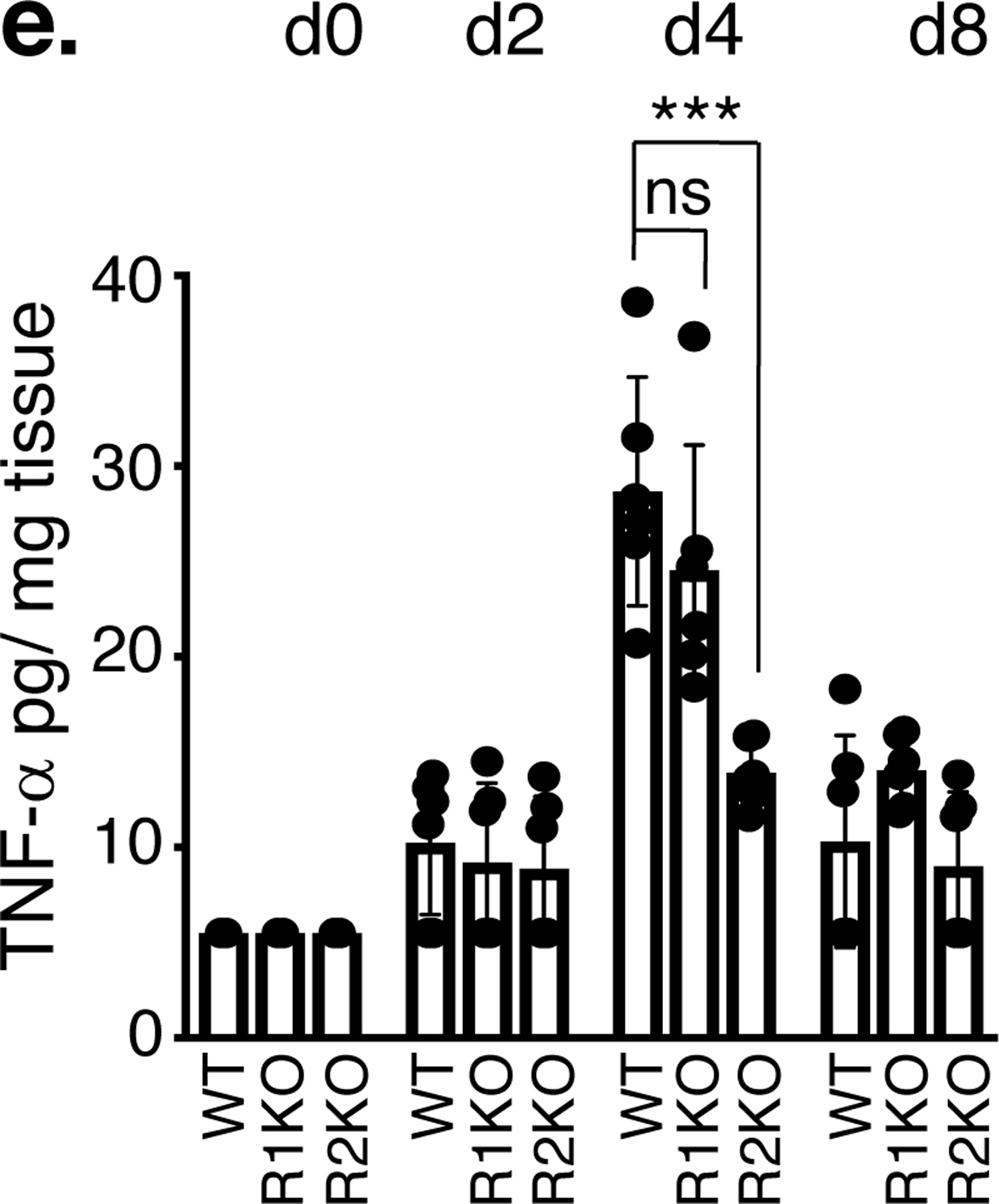

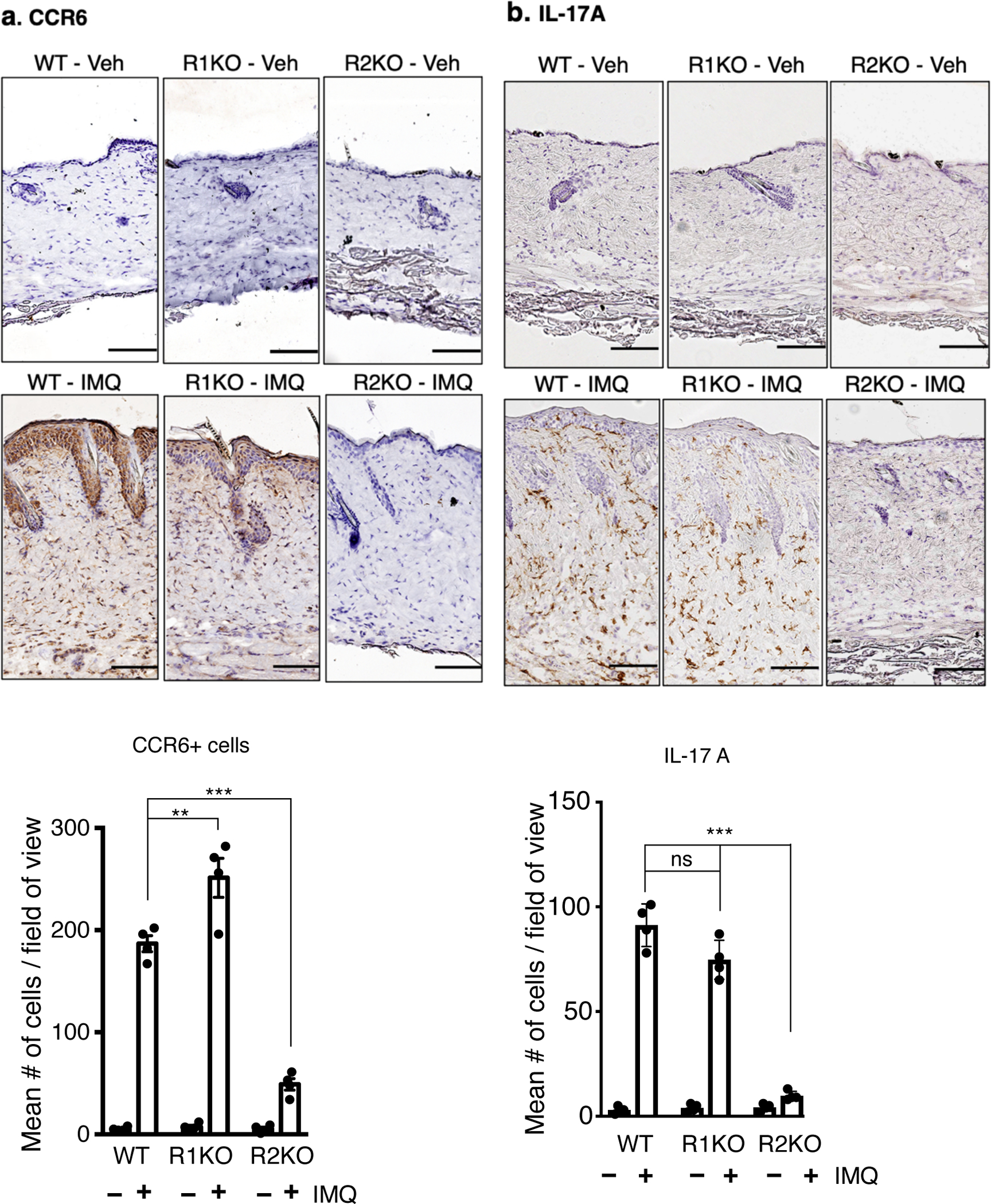

Our immunohistochemistry studies show an increase in C-C-chemokine receptor type 6 (CCR6)-positive, indicative of TH17 expressing cells in the skin of WT and TNFR1KO mice, respectively (Figure 3a), in response to IMQ. However, in IMQ-treated TNFR2KO mice, the number of CCR6-positive cells was significantly lower compared to WT or TNFR1KO mice (p <0.001 vs WT). IMQ-induced IL-17A immune reactivity in skin was also reduced in TNFR2KO, but not in TNFR1 mice (Figure 3b. p < 0.001). Since IMQ application in DKO mice was similar to TNFR2KO mice in terms of PASI, epidermal thickness and cytokine induction, we did not include DKO mice here onwards.

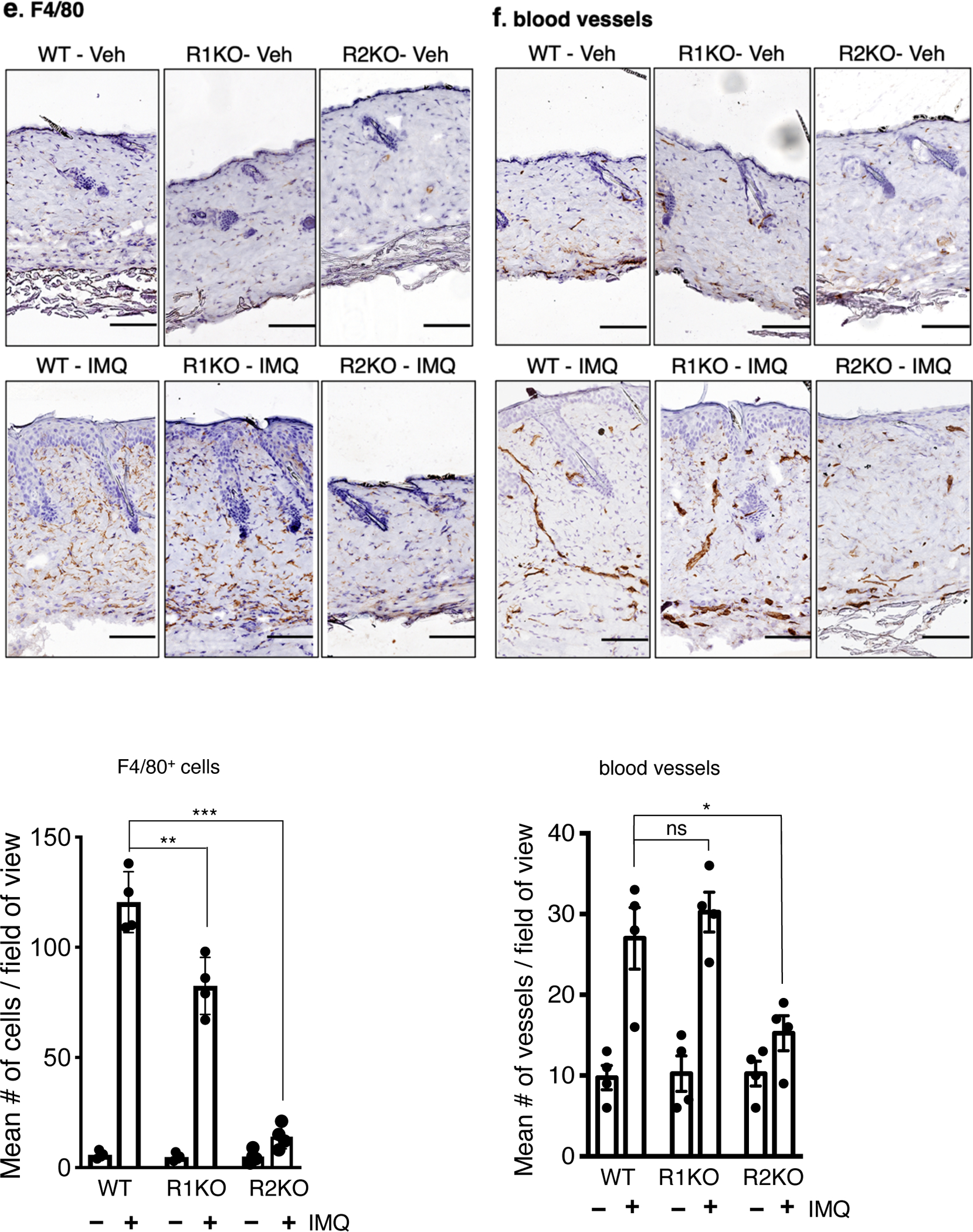

Figure 3. Effect of TNFR1 and TNFR2 gene inactivation on immune cell infiltration, IL-17A expression and angiogenesis in mouse skin in response to IMQ treatment.

Representative pictures of immunohistochemistry to detect, a. CCR6+ cells (indicative of TH17 cells), b. IL-17A expression, c. BST2+ cells (indicative of dendritic cells, red arrows), d. Gr-1+ cells (indicative of neutrophils), e. F4/80+ cells (indicative of macrophages) and f. meca-32+ cells (indicative of endothelial cells/capillary vessels) in the dorsal skin of vehicle-treated or IMQ-treated WT and TNFR1KO, TNFR2KO mice. Scale bar, 125 μm. Corresponding quantification is shown in bar graphs. Cells or microvessels were counted on three field of view (FOA, 20X) per section in a high-power field. Scoring was performed by two independent blinded researchers. Values are represented by mean ± SEM, (n = 4) ***p < 0.001, **p < 0.01, *p < 0. 05 (ANOVA).

Gamma delta T cells (γδ T cells) also produce IL-17A and can play a crucial role in psoriasis (Benhadou et al., 2019, Cai et al., 2011). However, we did not find a significant presence of γδ T cells in untreated or IMQ-treated skins samples of WT or TNFRKO mice (data not shown). In lymph nodes, both CCR6-positive cells and γδ T cells are increased in a TNFR2-dependent fashion (Supplementary Figure S3 a & b, respectively, p < 0.001).

Bone marrow stromal cell antigen 2 (BST2)-positive cells, indicative of plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), were also diminished in TNFR2KO skin (Figure 3c, p < 0.01). IMQ-induced infiltration of neutrophils (Gr-1+) was inhibited significantly in TNFR1KO and TNFR2KO skin compared to WT (p < 0.001 for both, Figure 3d). In contrast, although both receptors were involved, TNFR2 was predominant in recruiting F4/80-positive cells (macrophages) (Figure 3e, p <0.001), whereas TNFR2KO mice showed significantly lower number of blood vessels in the skin tissue (Figure 3f, p < 0.05) upon IMQ application.

Treg cells and dendritic cells are reduced in the lymph nodes of TNFR2KO mice in reseponse to topical IMQ treatment.

Upon topical IMQ application, we found a ~3 fold increase in CD25high, Foxp3+, Treg cell population in lymph nodes on 4 day of IMQ in WT and TNFR1KO, whereas in TNFR2KO there was no significant increase (Supplementary Figure 4a & b, p < 0.001). Time-course analysis showed Treg cells peaked at day 4 of IMQ application in WT and TNFR1KO mice but not in TNFR2KO mice (Supplementary Figures 4c, p < 0.001). Similarly, we found an increase in CD11c+ cells (p < 0.01) and, to a lesser extent, CD11b+ cells in WT and TNFR1KO mice but not in TNFR2KO mice (Supplementary Figure 4d & e). We did not find significant changes in CD4+ or CD8+ cells in WT or TNFRKO mice in response to IMQ (Supplementary Figure 4f & g).

Myeloid dendritic cells (MDC), TNF/iNOS producing DC (Tip-DC) and IL-23 expression, in the draining lymph nodes are TNFR2 - dependent.

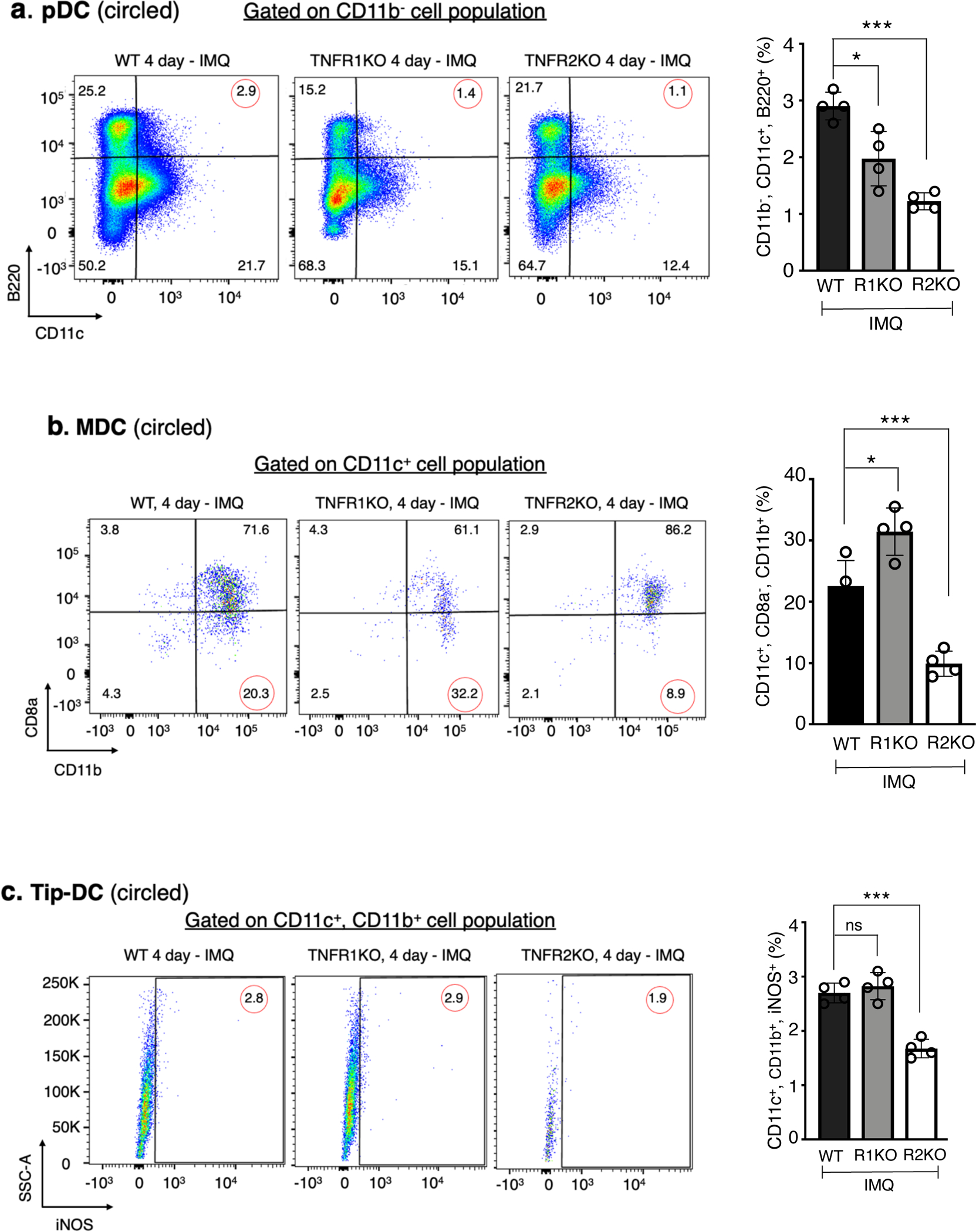

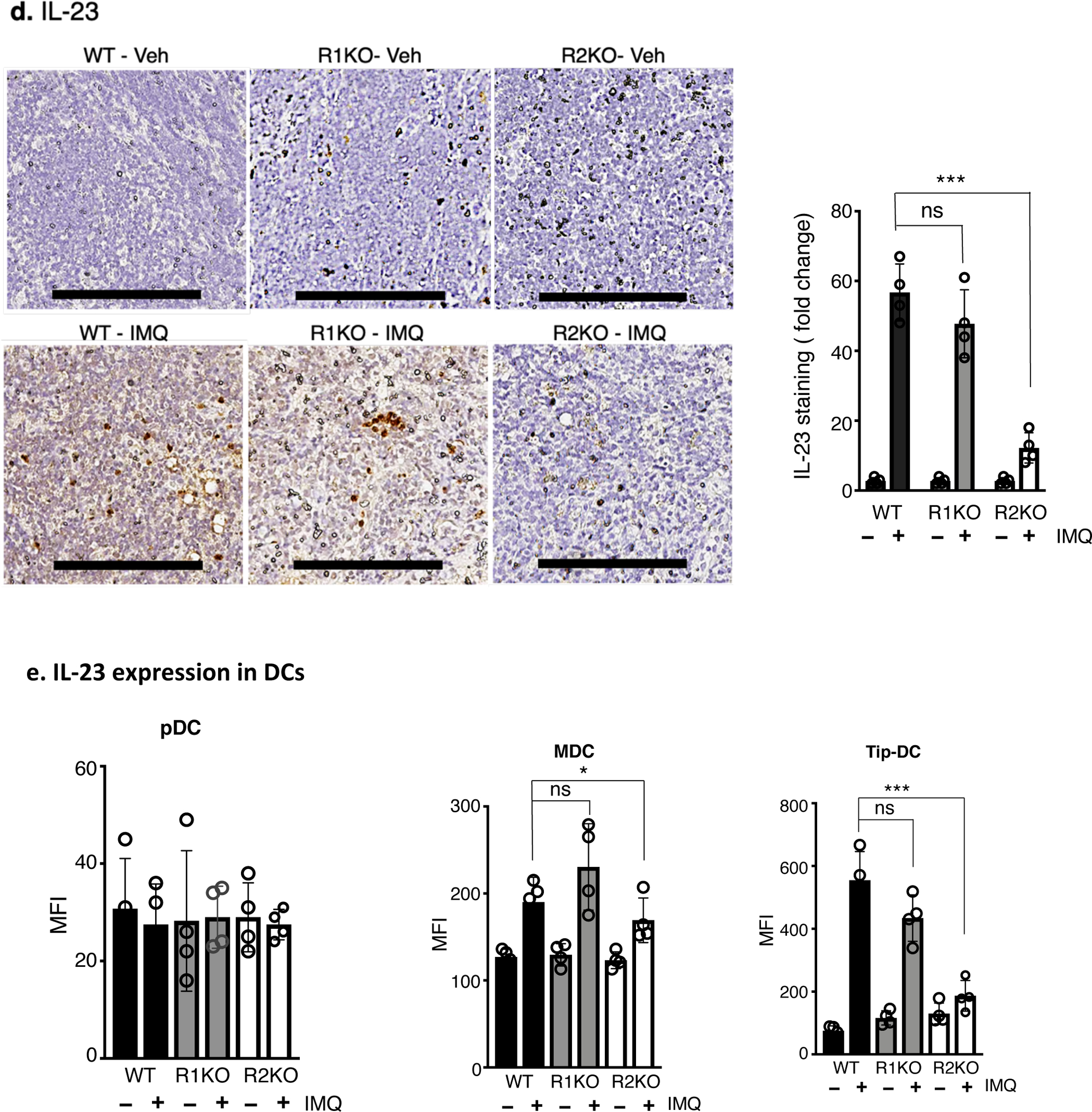

In psoriasis, pDC, MDC and Tip-DC, upon activation, migrate to draining lymph nodes and induce proliferation/polarization of TH17 cells (Fukunaga et al., 2008, Nestle et al., 2009). We found a reduced propotion of pDC in TNFR2KO (p < 0.001) as compared to WT in response to IMQ in the draining lymph nodes (Figure 4a, p < 0.001). TNFR1KO mice also showed a reduction in pDC but to a lesser magnitude (p < 0.05). Importantly, there was a significant reduction of MDC and Tip-DC in TNFR2KO (p < 0.001), but not in TNFR1KO mice (Figure 4b & c). Dendritic cell product, IL-23, which facilitates the polarization and stabilization of inflammatory TH17 cells (Langrish et al., 2005) is also reduced in the lymph nodes of TNFR2KO mice compared to WT (Figure 4d, p < 0.001). FACS analysis further showed that TNFR2-depletion reduced IL-23 production mainly in Tip-DCs (p < 0.001) and to a lesser extent in MDCs (p < 0.05), in response to IMQ (Figure 4e). CD86 expression indicative of dendritic cell activation and phagocytosis activity measured by engulfed polystyrene beads were comparable in lymph node CD11c+ cells isolated from TNFR2KO, TNFR1KO and WT mice upon IMQ (Supplementary Figure S5a & b).

Figure 4. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDC), myeloid DC (MDC) and Tip-DC are reduced in the lymph nodes of TNFR2KO mice vs WT or TNFR1KO mice, in response to IMQ.

Representative FACS analysis showing a. pDC (CD11c+, B220+, CD11b−), b. MDC (CD11c+, CD8a−, CD11b+) and c. Tip-DC (CD11c+, iNOS+, CD11b+ isolated from the lymph nodes (brachial & inguinal) of WT, TNFR1KO, and TNFR2KO mice that were undergone 3 days of IMQ treatment and harvested on day 4. The right panels shows quantification of corresponding cells (%). Percentage of pDC, MDC and Tip-DC in the lymph nodes from control mice low (< 1% for pDC and Tip-DC and < 3% for MDC, Supplentary figure S9). d. Immunohistochemistry showing IL- 23 protein in the paraffin sections of lymph nodes isolated from WT, TNFR1KO or TNFR2KO mice. Scale bar, 125 μm. The bar diagram demonstrates the quantification of IL-23 staining using Image J software and expressed as fold change with respect to control antibody image. e. IL-23 protein in pDC, MDC or Tip-DC prepared from vehicle- or IMQ-treated mice and cultured 16 hours in the presence of GolgiStop (BD Biosciences) and mean florescence intensity (MFI) was determined by flow cytometry using PE-labelled antiIL-23 antibody (R&D systems). n = 4; mean ± SEM, ANOVA, ***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05.

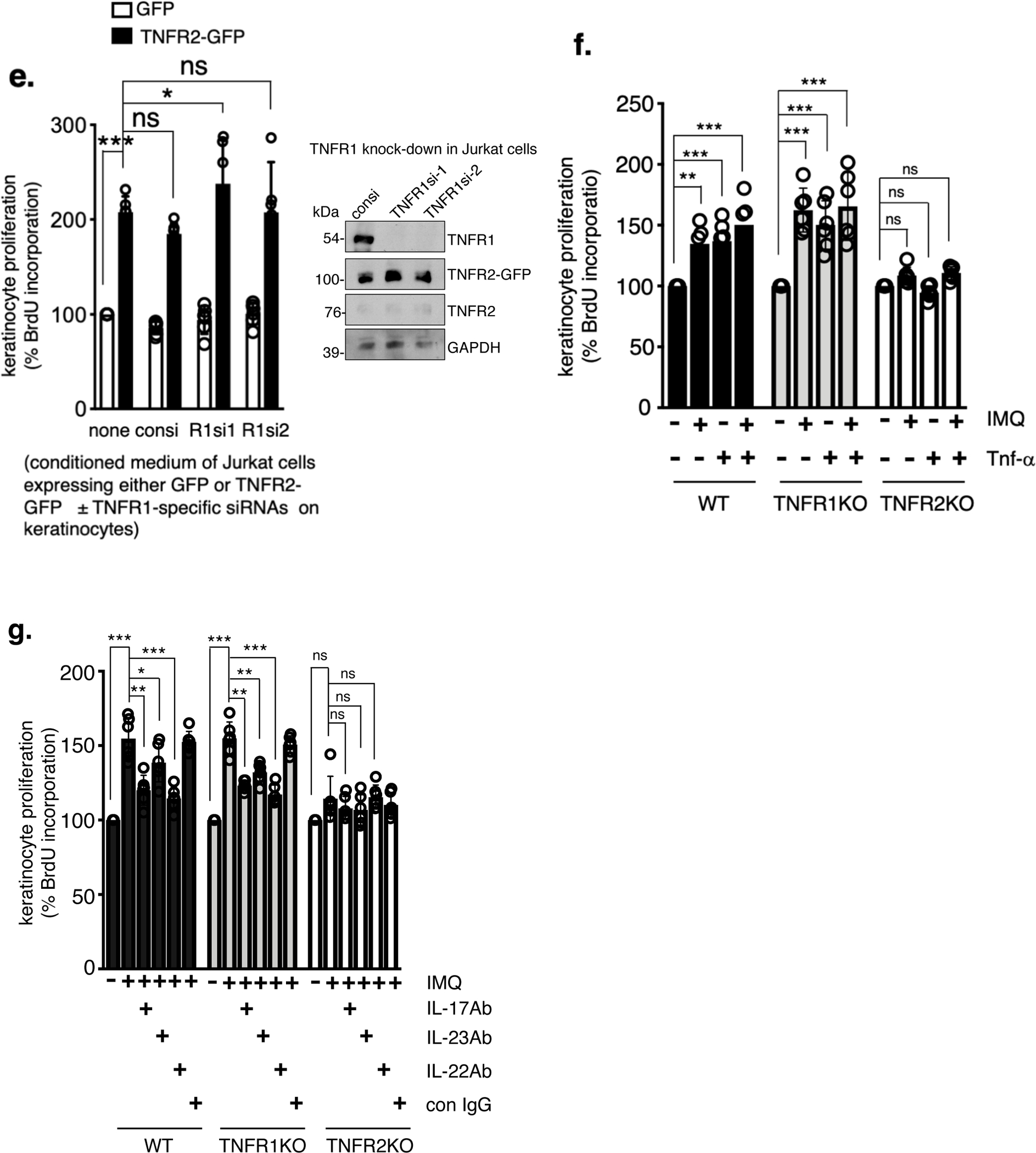

T-cell secretory factors produced in response to TNFR2 activation can induce keratinocyte proliferation in a paracrine fashion.

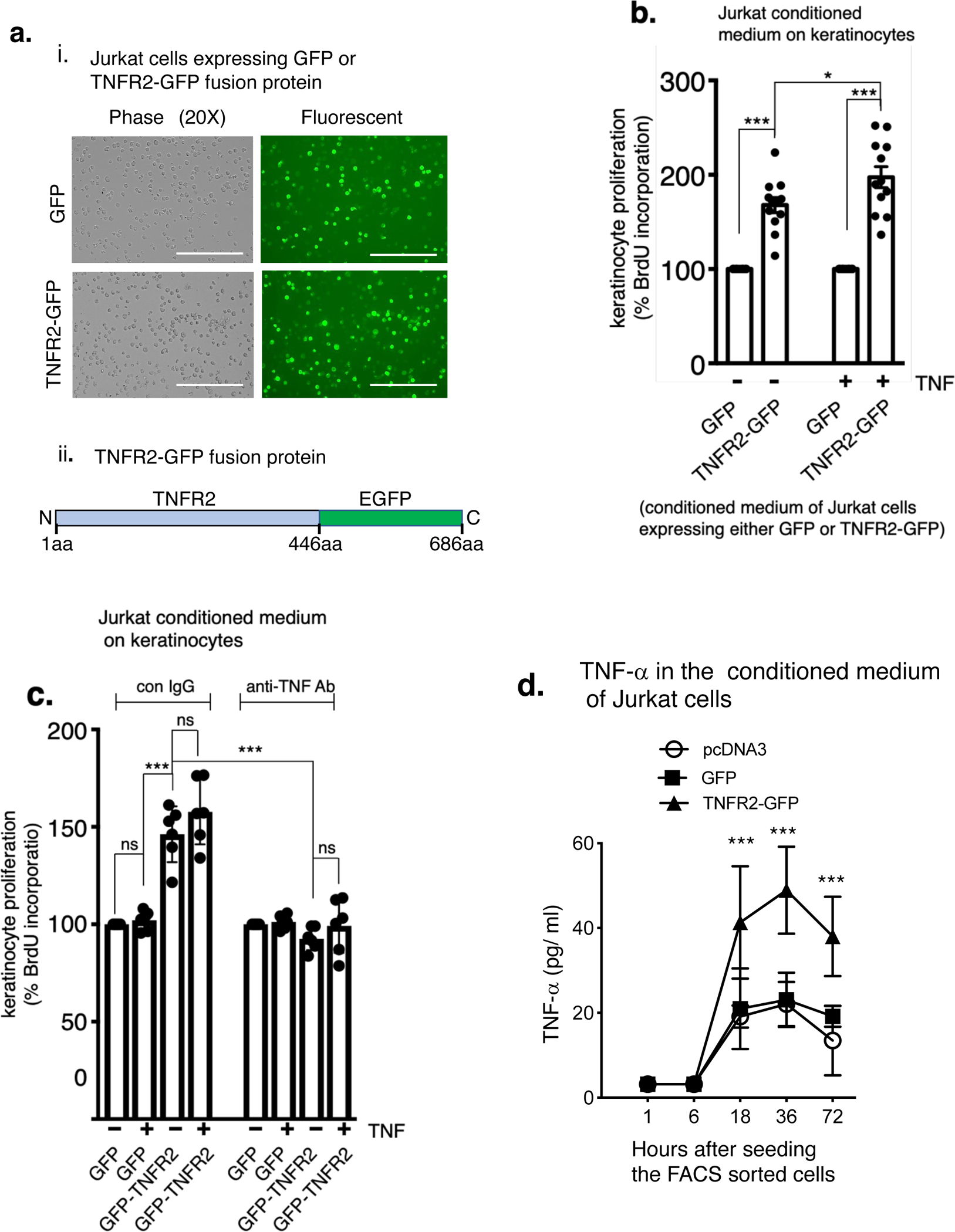

Epidermal hyperplasia is due to abnormal keratinocyte proliferation. Since TNFR2, but not TNFR1 is critical for TNF-α-mediated immune cell expansion and proliferation (Sheehan et al., 1995, Ye et al., 2018), we hypothesized that TNFR2-dependent activation of skin-infiltrated immune cells produce secretory factors that promote keratinocyte proliferation. To test this, we expressed TNFR2-GFP fusion protein in Jurkat T cells (Figure 5a), a cell-line that does not express TNFR2 but expresses TNFR1 (Chan and Lenardo, 2000, Ting et al., 1996, Zhang et al., 2017). The conditioned medium of FACS-sorted, TNFR2-GFP expressing Jurkat cells were used to test keratinocyte proliferation.

Figure 5. TNFR2 activity-dependent T-cell secretory factors induce keratinocyte activation.

ai. Jurkat T cells expressing GFP (control) or TNFR2-GFP fusion protein. The FACS sorted green cells were then cultured in a 96-well plate. Scale bar, 200 μm. aii. TNFR2-GFP construct, schematically. b. Keratinocyte proliferation induced by conditioned medium of GFP or TNFR2-GFP expressing Jurkat T cells. Jurkat T cells expressing GFP or TNFR2-GFP were cultured in the presence or absence of human TNF-α (2 ng/ml) for 18 hours. The supernatant was collected and treated on cultured adult human keratinocytes for 36 hours. Keratinocyte proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation assay by measuring absorbance at 450 nm. (n = 9; mean ± SEM, ANOVA). c. The Jurkat T cells in this case were cultured in the presence of control IgG or a TNF-α-neutralizing antibody (R&D systems, cat# AF-210-NA, 100 ng/ml) for 18 hours. The antibodies were removed from the supernatant by protein A/G agarose prior to treating the keratinocytes for 36 hours. In the right panel TNF-α (2ng/ml) was added after removing the TNF-α-neutralizing antibody, but prior to treating with the keratinocytes (n = 9; mean ± SEM, ANOVA). d. TNF-α levels (measured by ELISA) in the conditioned medium of Jurkat T cells reconstituted with TNFR2-GFP at the indicated time points. e. Keratinocyte proliferation was measured in response to conditioned medium of TNFR2-GFP reconstituted but TNFR1-depleted Jurkat T cells. Two independent TNFR1-specific siRNAs (R1si1& R1si2) were used to deplete TNFR1. The right panel shows effective knock-down of TNFR1 or TNFR2 protein. f. Keratinocyte proliferation induced by conditioned medium of cultured lymph node cells is TNFR2-dependent. Lymph node cells from untreated or IMQ-treated (IMQ: 3 days once daily & harvested on day 4) WT, TNFR1KO and TNFR2KO mice were cultured (48 hours) ± TNF-α (2ng/ml) and the conditioned medium was used to treat keratinocytes for 36 hours. g. Lymph node cells harvested from WT, TNFR1KO and TNFR2KO mice ( ± IMQ) and cultured in the presence of neutralizing antibodies (100ng/ml) targeting, IL-17A, IL-23 and IL-22 (all from R&D systems). Keratinocyte proliferation was determined by BrdU incorporation by measuring absorbance at 450 nm. (n = 6; mean ± SEM, ANOVA). ***p < 0.001, **p < 0. 01 and *p < 0.05.

Interestingly, keratinocytes treated with a conditioned medium of TNFR2-GFP cells showed a significant increase in proliferation, even in the absence of TNF-α stimulation (Figure 5b, p < 0.001). TNF-α stimulation showed only marginal additional increase in keratinocyte proliferation. Conditioned medium of TNFR2-GFP expressing Jurkat T cells (without external TNF-α stimulation) that are cultured in the presence of TNF-α-neutralizing antibody failed to induce keratinocyte proliferation (Figure 5c, right panel), however adding TNF-α after removing neutralizing antibody also did not increase keratinocyte proliferation. Further, we found TNF-α is secreted in TNFR2-GFP cells in a time-dependent fashion (Figure 5d). Also, conditioned medium of TNFR1-depleted, TNFR2-GFP cells did not reduce keratinocyte proliferation (Figure 5e). These results together suggest TNFR2 activation in Jurkat T cells, most likely in an autocrine fashion is sufficient to secret factors, which in turn induce keratinocyte proliferation.

To determine the in vivo relevance of our findings, we tested the conditioned medium of cultured lymph node cells harvested from untreated or IMQ-treated WT, TNFR1KO or TNFR2KO mice on keratinocyte proliferation. Conditioned medium of WT and TNFR1KO lymph node cells increased in keratinocyte proliferation (Figure 5f, p < 0.001), but not conditioned medium of TNFR2KO lymph node cells. Furthermore, culturing the WT and TNFR1KO lymph node cells with specific neutralizing antibodies targeting IL-17, IL-23 or IL-22 diminished the keratinocyte proliferation significantly (Figure 5g).

We next tested whether keratinocytes (which expresses TNFR1, but not TNFR2, Supplementary Figure S6a) directly induce psoriatic disease-related genes in response to TNF-α. TNF-α induction of psoriasis-related gene such as S100A9 was minimal (Supplementary Figure S7a), wereas, IL-17A and IL-22, which are produced by TH17 cells (Fitch et al., 2007) induced the expression of S100A9 significantly (p < 0.01). IL-17A or IL-22 together with TNF-α did not alter S100A9 induction significantly. However, when we treated keratinocytes with IL-17A and IL-22 in combination we found a synergistic effect on S100A9 induction (p < 0.001). Also, IL-17A and IL-22 in combination reduced keratin 10 gene expression, an indicator of keratinocyte differentiation, significantly (Supplementary Figure S7b, p < 0.05). These results together suggest that the effect of TNF-α on keratinocyte response in psoriasis pathogenesis is indirect, potentially via TNFR2 / TH17 axis.

DISCUSSION

Although many targeted therapies are available to treat psoriatic disease, anti-TNF therapy remains one of the most efficacious for treating both skin and joints (Elyoussfi et al., 2016, Ogdie et al., 2020, Singh et al., 2019). These anti-TNF agents work by neutralizing TNF-α and prevent it from binding to TNFR1 and TNFR2. However, the relative contributions of these two receptors in psoriasis pathogenesis are not well-understood. Here, we demonstrate mechanistically, the critical role of TNFR2 as opposed to TNFR1 in psoriasis pathogenesis, using a preclinical model.

Similar to psoriasis in human, IMQ-mediated psoriasis inflammation is facilitated predominantly via the IL-23/IL-17 axis (Flutter and Nestle, 2013, van der Fits et al., 2009). IL-17 family of cytokines including IL17A, IL-17C and IL-17F is abundantly expressed in psoriatic lesions (Johnston et al., 2013, Monin and Gaffen, 2017). Among these, the role of IL-17A in psoriasis pathogenesis is well-documented and IL-17A-neutralizing antibodies (secukinumab, ixekizumab) are effective for treating psoriasis (Monin and Gaffen, 2017). Similarly, ustekinumab, an IL-12/IL-23 neutralizing antibody, is also effective in treating psoriasis (Cao et al., 2015). In addition, it has been shown using in vitro studies that anti-TNF agents can reduce TH17 cell response via down regulating dendritic cell activation (Zaba et al., 2007) or via inhibiting TNF-α / TNFR2 signaling in TH17 cells (Shiga et al., 2015). Our studies show IMQ induction of IL-17A and IL-23 are greatly reduced in the affected skin and peripheral blood of TNFR2KO mice compared to WT or TNFR1KO mice. Further, in the draining lymph nodes, a subset of psoriasis-related dendritic cells, MDC, and Tip-DC and CCR6+, TH17 cells were increased upon IMQ in a TNFR2-dependent fashion. TNFR2-depletion did not compromise TH17 cell polarization of CD4+ T cells in vitro (Supplementary Figure S8), whereas it reduced IL-23 protein levels in the lymph nodes. We also found that in the absence of TNFR2, IMQ-induced IL-23 production is compromised significantly in Tip-DCs and MDCs. Therefore, it is likely that the downregulation of IL-17A expression in TNFR2KO mice is due to the inhibition of dendritic cell-dependent IL-23 production and consequent reduction in TH17 cell polarization.

IMQ induction of IL-17C and IL-17F, however, is inhibited when either TNFR1 or TNFR2 is inactivated. Further, TNF-α can directly act on keratinocyte TNFR1 and induce IL-6 and IL-8 (Supplementary Figure S6b). This may partly explain why TNFR1KO also shows a reduction in skin pathology, but relatively a lesser effect than in the TNFR2KO mice.

We found that conditioned medium of TNFR2 expressing Jurkat T cells can induce TNF-α. This conditioned medium can also induce keratinocyte proliferation, which is inhibited when the Jurkat T cells are cultured in the presence of a TNF-α neutralizing antibody. Interestingly, direct TNF-α stimulation failed to induce keratinocyte proliferation. These results together suggest that keratinocyte proliferation is likely due to factors other than TNF-α, secreted by Jurkat T cells, as a result of potentially, autocrine TNFR2 activation.

The mechanisms underlying TNFR2-mediated production of TNF-α in the Jurkat T cells is not clear. It is possible that this could be due to a constitutional activity of the TNFR2. TNF-α is expressed as a membrane-anchored protein (Kriegler et al., 1988) and a TNF-α-converting enzyme cleaves and releases membrane-bound TNF-α into a soluble form (Black et al., 1997). Soluble TNF-α activates TNFR1, whereas TNFR2 can be activated by both soluble and membrane-anchored TNF-α (Grell et al., 1995). Therefore, it is also possible that TNFR2 activation and consequent TNF-α production can be driven via an intercellular, membrane-bound TNF-α /TNFR2 interactions by adjacent T cells. Further studies are warranted to decipher underlying molecular mechanisms of TNFR2-mediated activation of immune cells within the context of psoriasis pathogenesis.

While dendritic cells participate in psoriasis pathogenesis, Treg cells help in resolving inflammatory responses via producing anti-inflammatory molecules such as IL-10 (Arce-Sillas et al., 2016, Cai et al., 2012). We found IMQ induction of IL-10 production is also TNFR2-dependent. It is possible that this paradoxical observation is due to a robust TNFR2 immune responses such as dendritic cell proliferation and IL-23 production overrides Treg cell-dependent anti-inflammatory effects. There are reports of a functional defect in Treg cells in patients with autoimmune diseases, including psoriasis (Grant et al., 2015, Pasare and Medzhitov, 2003, Smigiel et al., 2014). Therefore it is important to determine functional integrity of Treg cells to fully account for its suppressive effect on TH17 cell polarization.

A recent publication by Chen et. al., reported that depleting TNFR2 resulted in a more severe psoriasis-like inflammation in IMQ model, compared to WT mice, whereas TNFR1KO mice displayed a lesser disease phenotype (Chen et al., 2021). This decrepancy may be due to potential methodological differences. These include, thoroughly removing the dorsal hair prior to IMQ application, which is a critical factor for achieving a consistent IMQ effect. We experienced that commerically available depilatory agents can cause uneven IMQ responses, most likely by inducing/priming a non-specific inflammatory response. Also, quantification of epidermal thickness and psoriasis-related immunecells in the skin section need to be characterzed. Chen et. al., did not disclose these specifics making it difficult to evaluate their study. However, they showed that an adaptive transfer of Treg cells from WT mice can reduce the disease phenotype in TNFR2KO mice. Other than the absence of the quantified skin parameters, the adaptive transfer experiment is missing some key controls: transfer of Treg cells isolated from TNFR2KO mice to WT, TNFR1KO and TNFR2KO which are necessary to rule out non-specific effects of the adaptive transfer. Nevertheless, it is important to be cautious with therapies that target TNFR2 in humans and can be applied in diseases where TNFR2-mediated deleterious responses outweigh the Treg-dependent anti-inflammatory protection.

TNFR1 is expressed ubiquitously including keratinocytes of normal and lesional human skin, however, there are varying data with respect to the TNFR2 expression profile in the lesional psoriasis skin. For example, Caldarola, et. al. reported TNFR2 expression in keratinocytes of human psoriatic skin (Caldarola et al., 2009). Other studies have demonstrated that TNFR2 is localized in dermal blood vessels and perivascular infiltrating cells, but not in keratinocytes (Kristensen et al., 1993, Trefzer et al., 1993). In agreement with the latter, we found TNFR1, but not TNFR2 is expressed in mice skin keratinocytes (Figure 2c & d) and in cultured human keratinocytes (Supplementary Figure S6a).

In summary, our study provides compelling evidence that TNFR2, but not TNFR1, plays a dominant role in pathogenesis of psoriatic inflammation. Notwithstanding that evidence of protective function by soluble TNFR2 exists (Keeton et al., 2014), our findings potentially have strong clinical implications on patients outcomes, as long-term use of current anti-TNF drugs display unintended effects, which are largely associated with TNFR1, but not TNFR2 inactivation (Balkwill, 2006, Jacobs et al., 2000, Senaldi et al., 1996, Tsuji et al., 1997, Yasui, 2014). Further, unlike ubiquitously expressed TNFR1, TNFR2 expression is limited, mostly in tissues relevant to psoriasis pathogenesis (Faustman and Davis, 2010). This restricted tissue expression may also limit the adverse effects of a TNFR2-targeted therapy. Taken together, selectively inhibiting TNFR2 while retaining TNFR1 function may be effective and possibly show fewer adverse effects compared to the existing anti-TNF drugs in treating patients with psoriasis and potentially other immune-mediated diseases.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Imiquimod (IMQ)-induced psoriasis mouse model

WT, TNFR1KO, TNFR2KO, and TNFR1; TNFR2-double-null mice (DKO) are in the C57BL/6 background. 8–10-week-old mice with equal number of males and females (n=6) received a daily topical dose of 80 mg (4 mg of the active compound) of commercially available imiquimod cream (Aldara, 3M Health Care Limited, UK).

The cream was applied on the shaved (using a Wahl Pocket Trimmer) dorsal skin (~4 cm2 area) for 4 consecutive days as reported earlier (van der Fits et al., 2009). Mice were euthanized and skin and blood samples were collected. Control mice were treated with a baby lotion (Johnson & Johnson), which contains similar inactive ingredients as Aldara cream. The harvested skin specimens from each mouse are divided into 4 aliquots for paraffin fixation, frozen sections, RNA and protein extraction.

Culturing mice lymph node cells.

Brachial and inguinal lymph nodes were harvested from vehicle-treated or IMQ-treated mice after euthanization. The lymph nodes were teased to generate single-cell suspension using a 3 ml syringe plunger. The cell suspensions were passed through a cell strainer (30μM mesh size) to eliminate clumps and debris. The cell suspensions were centrifuged for 5 minutes (1000×g) at 4°C and the cell pellet was resuspended in cold culture medium (RPMI with 10% FBS). Cell preparations with > 95% cell viability was used for culturing and further analysis.

The animal procedures used in this study were approved by Cleveland Clinic IACUC (protocol number: 2017–1810) which adhere to the guidelines in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the NIH.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Blood samples were collected from the mice by saphenous bleeding at indicated days of IMQ treatment and plasma underwent ELSA of cytokines with kits IL-17A, IL-10, IFN-α and TNF-α (R&D Systems), CXCL10 (Novus Biologicals) and CXCL11 (Thermofisher Scientific). The concentrations of the cytokines were calculated from the standard curve following the manufacturer’s protocol.

Details of cell culture, PASI scoring, histology & immunohistochemistry, quantitative PCR, RNA interference, BrdU incorporation assay, Flow cytometry and statistical analysis are provided in the Supplementary Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

We thank Flow Cytometry Core and Imaging Core of Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic for flow cytometry analysis and histology analysis. This work was supported by the following agencies: National Psoriasis Foundation (NPF) Discovery Grant: NPSF1608UC to UMC, NPF Bridge-Grant: NPF1808UC to UMC & MEH, NIH Grant R01AR075777 to MEH & UMC, NIH Grant GM050009 (T. Egelhoff - PI, UMC - CoI), NIH grant HL155064 to RGS, and Institutional support to MEH by the Department of Rheumatic and Immunologic Diseases, Cleveland Clinic.

Conflict of interests.

APF receives research support from Mallinckrodt, AbbVie, Pfizer and Novartis and honorarium from AbbVie, Novartis, UCB, and Mallinckrodt for consulting, advisory board participation, and speaking. The remaining authors declare no conflict of Interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data availability Statement.

All relevant data for this article is included, and any further inquiry including the protocol used can be made to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- Arce-Sillas A, Alvarez-Luquin DD, Tamaya-Dominguez B, Gomez-Fuentes S, Trejo-Garcia A, Melo-Salas M, et al. Regulatory T Cells: Molecular Actions on Effector Cells in Immune Regulation. J Immunol Res 2016;2016:1720827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F TNF-alpha in promotion and progression of cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2006;25(3):409–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benhadou F, Mintoff D, Del Marmol V. Psoriasis: Keratinocytes or Immune Cells - Which Is the Trigger? Dermatology 2019;235(2):91–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RA, Rauch CT, Kozlosky CJ, Peschon JJ, Slack JL, Wolfson MF, et al. A metalloproteinase disintegrin that releases tumour-necrosis factor-alpha from cells. Nature 1997;385(6618):729–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Fleming C, Yan J. New insights of T cells in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Cell Mol Immunol 2012;9(4):302–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Shen X, Ding C, Qi C, Li K, Li X, et al. Pivotal role of dermal IL-17-producing gammadelta T cells in skin inflammation. Immunity 2011;35(4):596–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldarola G, De Simone C, Carbone A, Tulli A, Amerio P, Feliciani C. TNFalpha and its receptors in psoriatic skin, before and after treatment with etanercept. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2009;22(4):961–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z, Carter C, Wilson KL, Schenkel B. Ustekinumab dosing, persistence, and discontinuation patterns in patients with moderate-to-severe psoriasis. J Dermatolog Treat 2015;26(2):113–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan FK, Lenardo MJ. A crucial role for p80 TNF-R2 in amplifying p60 TNF-R1 apoptosis signals in T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol 2000;30(2):652–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekharan UM, Siemionow M, Unsal M, Yang L, Poptic E, Bohn J, et al. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha) receptor-II is required for TNF-alpha-induced leukocyte-endothelial interaction in vivo. Blood 2007;109(5):1938–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Goeddel DV. TNF-R1 signaling: a beautiful pathway. Science 2002;296(5573):1634–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Lin Z, Xi L, Zheng Y, Zhou Q, Chen X. Differential role of TNFR1 and TNFR2 in the development of imiquimod-induced mouse psoriasis. J Leukoc Biol 2021;110(6):1047–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Baumel M, Mannel DN, Howard OM, Oppenheim JJ. Interaction of TNF with TNF receptor type 2 promotes expansion and function of mouse CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. J Immunol 2007;179(1):154–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordoro KM, Feldman SR. TNF-alpha inhibitors in dermatology. Skin Therapy Lett 2007;12(7):4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elyoussfi S, Thomas BJ, Ciurtin C. Tailored treatment options for patients with psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: review of established and new biologic and small molecule therapies. Rheumatol Int 2016;36(5):603–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustman D, Davis M. TNF receptor 2 pathway: drug target for autoimmune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2010;9(6):482–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faustman DL, Davis M. TNF Receptor 2 and Disease: Autoimmunity and Regenerative Medicine. Front Immunol 2013;4:478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finckh A, Simard JF, Gabay C, Guerne PA, physicians S. Evidence for differential acquired drug resistance to anti-tumour necrosis factor agents in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65(6):746–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch E, Harper E, Skorcheva I, Kurtz SE, Blauvelt A. Pathophysiology of psoriasis: recent advances on IL-23 and Th17 cytokines. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2007;9(6):461–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flutter B, Nestle FO. TLRs to cytokines: mechanistic insights from the imiquimod mouse model of psoriasis. Eur J Immunol 2013;43(12):3138–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga A, Khaskhely NM, Sreevidya CS, Byrne SN, Ullrich SE. Dermal dendritic cells, and not Langerhans cells, play an essential role in inducing an immune response. J Immunol 2008;180(5):3057–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottenberg JE, Brocq O, Perdriger A, Lassoued S, Berthelot JM, Wendling D, et al. Non-TNF-Targeted Biologic vs a Second Anti-TNF Drug to Treat Rheumatoid Arthritis in Patients With Insufficient Response to a First Anti-TNF Drug: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2016;316(11):1172–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goukassian DA, Qin G, Dolan C, Murayama T, Silver M, Curry C, et al. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor p75 is required in ischemia-induced neovascularization. Circulation 2007;115(6):752–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant CR, Liberal R, Mieli-Vergani G, Vergani D, Longhi MS. Regulatory T-cells in autoimmune diseases: challenges, controversies and--yet--unanswered questions. Autoimmun Rev 2015;14(2):105–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grell M, Douni E, Wajant H, Lohden M, Clauss M, Maxeiner B, et al. The transmembrane form of tumor necrosis factor is the prime activating ligand of the 80 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell 1995;83(5):793–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs M, Brown N, Allie N, Chetty K, Ryffel B. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 plays a minor role for mycobacterial immunity. Pathobiology 2000;68(2):68–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston A, Fritz Y, Dawes SM, Diaconu D, Al-Attar PM, Guzman AM, et al. Keratinocyte overexpression of IL-17C promotes psoriasiform skin inflammation. J Immunol 2013;190(5):2252–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeton R, Allie N, Dambuza I, Abel B, Hsu NJ, Sebesho B, et al. Soluble TNFRp75 regulates host protective immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Clin Invest 2014;124(4):1537–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegler M, Perez C, DeFay K, Albert I, Lu SD. A novel form of TNF/cachectin is a cell surface cytotoxic transmembrane protein: ramifications for the complex physiology of TNF. Cell 1988;53(1):45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen M, Chu CQ, Eedy DJ, Feldmann M, Brennan FM, Breathnach SM. Localization of tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and its receptors in normal and psoriatic skin: epidermal cells express the 55-kD but not the 75-kD TNF receptor. Clin Exp Immunol 1993;94(2):354–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langrish CL, Chen Y, Blumenschein WM, Mattson J, Basham B, Sedgwick JD, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med 2005;201(2):233–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monin L, Gaffen SL. Interleukin 17 Family Cytokines: Signaling Mechanisms, Biological Activities, and Therapeutic Implications. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestle FO, Di Meglio P, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2009;9(10):679–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogdie A, Coates LC, Gladman DD. Treatment guidelines in psoriatic arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2020;59(Suppl 1):i37–i46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S, An P, Zhang R, He X, Yin G, Min W. Etk/Bmx as a tumor necrosis factor receptor type 2-specific kinase: role in endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 2002;22(21):7512–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll pathway-dependent blockade of CD4+CD25+ T cell-mediated suppression by dendritic cells. Science 2003;299(5609):1033–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Li Q, Wang H, Wu J, Li C, Liu Y, et al. Fn14 deficiency ameliorates psoriasis-like skin disease in a murine model. Cell Death Dis 2018;9(8):801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peschon JJ, Torrance DS, Stocking KL, Glaccum MB, Otten C, Willis CR, et al. TNF receptor-deficient mice reveal divergent roles for p55 and p75 in several models of inflammation. J Immunol 1998;160(2):943–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothe J, Lesslauer W, Lotscher H, Lang Y, Koebel P, Kontgen F, et al. Mice lacking the tumour necrosis factor receptor 1 are resistant to TNF-mediated toxicity but highly susceptible to infection by Listeria monocytogenes. Nature 1993;364(6440):798–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedger LM, McDermott MF. TNF and TNF-receptors: From mediators of cell death and inflammation to therapeutic giants - past, present and future. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2014;25(4):453–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senaldi G, Yin S, Shaklee CL, Piguet PF, Mak TW, Ulich TR. Corynebacterium parvum- and Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin-induced granuloma formation is inhibited in TNF receptor I (TNF-RI) knockout mice and by treatment with soluble TNF-RI. J Immunol 1996;157(11):5022–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan KC, Pinckard JK, Arthur CD, Dehner LP, Goeddel DV, Schreiber RD. Monoclonal antibodies specific for murine p55 and p75 tumor necrosis factor receptors: identification of a novel in vivo role for p75. J Exp Med 1995;181(2):607–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiga T, Sato K, Kataoka S, Sano S. TNF inhibitors directly target Th17 cells via attenuation of autonomous TNF/TNFR2 signalling in psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci 2015;77(1):79–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh JA, Guyatt G, Ogdie A, Gladman DD, Deal C, Deodhar A, et al. Special Article: 2018 American College of Rheumatology/National Psoriasis Foundation Guideline for the Treatment of Psoriatic Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019;71(1):2–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smigiel KS, Srivastava S, Stolley JM, Campbell DJ. Regulatory T-cell homeostasis: steady-state maintenance and modulation during inflammation. Immunol Rev 2014;259(1):40–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solovic I, Sester M, Gomez-Reino JJ, Rieder HL, Ehlers S, Milburn HJ, et al. The risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: a TBNET consensus statement. Eur Respir J 2010;36(5):1185–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tartaglia LA, Weber RF, Figari IS, Reynolds C, Palladino MA, Jr., Goeddel DV. The two different receptors for tumor necrosis factor mediate distinct cellular responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1991;88(20):9292–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ting AT, Pimentel-Muinos FX, Seed B. RIP mediates tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 activation of NF-kappaB but not Fas/APO-1-initiated apoptosis. EMBO J 1996;15(22):6189–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trefzer U, Brockhaus M, Lotscher H, Parlow F, Budnik A, Grewe M, et al. The 55-kD tumor necrosis factor receptor on human keratinocytes is regulated by tumor necrosis factor-alpha and by ultraviolet B radiation. J Clin Invest 1993;92(1):462–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H, Harada A, Mukaida N, Nakanuma Y, Bluethmann H, Kaneko S, et al. Tumor necrosis factor receptor p55 is essential for intrahepatic granuloma formation and hepatocellular apoptosis in a murine model of bacterium-induced fulminant hepatitis. Infect Immun 1997;65(5):1892–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Fits L, Mourits S, Voerman JS, Kant M, Boon L, Laman JD, et al. Imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation in mice is mediated via the IL-23/IL-17 axis. J Immunol 2009;182(9):5836–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenabeele P, Declercq W, Beyaert R, Fiers W. Two tumour necrosis factor receptors: structure and function. Trends Cell Biol 1995;5(10):392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wroblewski R, Armaka M, Kondylis V, Pasparakis M, Walczak H, Mittrucker HW, et al. Opposing role of tumor necrosis factor receptor 1 signaling in T cell-mediated hepatitis and bacterial infection in mice. Hepatology 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasui K Immunity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the risk of biologic anti-TNF-alpha reagents. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2014;12:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye LL, Wei XS, Zhang M, Niu YR, Zhou Q. The Significance of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Type II in CD8(+) Regulatory T Cells and CD8(+) Effector T Cells. Front Immunol 2018;9:583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaba LC, Cardinale I, Gilleaudeau P, Sullivan-Whalen M, Suarez-Farinas M, Fuentes-Duculan J, et al. Amelioration of epidermal hyperplasia by TNF inhibition is associated with reduced Th17 responses. J Exp Med 2007;204(13):3183–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M, Wang J, Jia L, Huang J, He C, Hu F, et al. Transmembrane TNF-alpha promotes activation-induced cell death by forward and reverse signaling. Oncotarget 2017;8(38):63799–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Xu Y, Ekman N, Wu Z, Wu J, Alitalo K, et al. Etk/Bmx transactivates vascular endothelial growth factor 2 and recruits phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase to mediate the tumor necrosis factor-induced angiogenic pathway. J Biol Chem 2003;278(51):51267–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data for this article is included, and any further inquiry including the protocol used can be made to the corresponding author.