Abstract

In this study, we wanted to assess the impact of the use of a patient educational app on patient knowledge about noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) and preparedness for prenatal screening decision-making. A randomized control study was carried out at three international sites between January 2019 and October 2020. Study participants completed a pre-consultation survey and post-consultation survey to assess knowledge, satisfaction, and preparedness for prenatal screening consultation. Providers completed a post-consultation survey. In the control arm, the pre-consultation survey was completed prior to consultation with their prenatal care provider. In the intervention arm, the pre-consultation survey was completed after using the app but prior to consultation with their prenatal care provider. Mean knowledge scores in the 203 participants using the app were significantly higher pre-consultation (p < 0.001) and post-consultation (p < 0.005) than those not using the app. Higher pre-consultation knowledge scores in the intervention group were observed at all sites. Most (86%) app users stated they were “Satisfied” or “Very Satisfied” with it as a tool. Providers rated the intervention group as more prepared than controls (p = 0.027); provider assessment of knowledge was not significantly different (p = 0.073). This study shows that clinical implementation of a patient educational app in a real-world setting was feasible, acceptable to pregnant people, and positively impacted patient knowledge.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12687-022-00596-x.

Keywords: Noninvasive prenatal testing, Surveys and questionnaires, Health knowledge, Attitudes, Decision making, Patient satisfaction

Introduction

First introduced into clinical care in 2011, noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) for common aneuploidy screening has been widely adopted across the globe (Ravitsky et al. 2021). NIPT analyzes cell-free DNA in a pregnant person’s blood and has the highest sensitivity and specificity for aneuploidy screening of available prenatal screening tests (Gil et al. 2017). Globally, professional medical societies recognize NIPT as an appropriate screening option for pregnant patients and emphasize the importance of pre-test counseling prior to prenatal screening and the need for informed choice.

According to Marteau, “an informed choice is one that is based on relevant knowledge, consistent with the decision maker’s values and behaviorally implemented” (Marteau et al. 2001). Evidence has not yet supported the concern (Kater-Kuipers et al. 2018) that the ease of use with cell-free DNA screening will lead to “routinization” of testing and erode pregnant people’s informed choice (Cernat et al. 2019). Historically, counseling regarding prenatal screening and testing options has focused on ensuring that pregnant people have sufficient knowledge to make an informed decision. However, given concerns about limited time and resources available for pretest counseling, there is a trend toward the providers’ role shifting from primarily being that of information-giver to that of decision-making facilitator.

NIPT Insights is an app-based patient educational tool designed to aid prenatal care providers in the dissemination of the foundational knowledge required as a component of informed choice. By providing pregnant people with the information prior to consultation with their providers, incorporating the app into clinical care will enable the provider to use the limited face-to-face consultation time in a shared decision-making model facilitating a decision that is consistent with the pregnant person’s beliefs and values.

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of NIPT Insights as an adjunct to provider counseling regarding NIPT on patients’ preparedness for discussion with their providers about prenatal screening and testing options. Secondary objectives were to assess patient satisfaction with the app and impact of the app-based educational tool on time spent counseling about prenatal screening and testing options by the prenatal provider.

Materials and methods

This was a randomized controlled trial implemented at three sites: An Ultrasound Unit in Madrid, Spain; a Fetal Medicine Unit with dedicated aneuploidy screening clinics in Clamart, France; and a Prenatal Genetics clinic in Tokyo, Japan. Pregnant people who were being offered NIPT as part of their routine care, and who were 18 years of age or older and spoke either English, French, Spanish, or Japanese, were eligible for participation. Participants were recruited between January 2019 through October 2020. Participants were randomized into one of two arms at the provider level. In the control arm, participants received routine care regarding prenatal screening and testing options, which varied across sites. Routine care in Spain included consultation with an obstetrician; in France, consultation with a dedicated midwife or genetic counselor; and in Japan, consultation with a genetic counselor. In the intervention arm, participants were provided access to the app-based patient educational tool in addition to routine care. Participants in the intervention group were provided with an iPad with access to NIPT Insights [https://apps.apple.com/us/app/nipt-insights/id1408704012; https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=eu.fiveminutes.illumina&hl=en_US&gl=US] for review in the waiting room prior to their consultation.

NIPT Insights was developed by Illumina, Inc. The content was written by three board-certified genetic counselors. Input was incorporated from maternal–fetal medicine specialists, patient advocacy groups, and focus groups of mothers of children with medical conditions from multiple countries throughout the world. The app was tested by women of reproductive age for input on design. NIPT Insights provides information about prenatal screening and testing options, with an emphasis on NIPT. It is available in multiple languages, with country-specific content. Features of the app include values assessment questions, ability to save topics of interest for further conversations, and the ability to email a summary of the participants’ app journey to themselves or their providers.

All study participants were asked to complete both a pre-consultation survey and post-consultation survey. The pre-consultation survey consisted of 25 questions, including 10 demographic questions and 15 knowledge-based questions (see Online Resource 1, Supplementary Table 1). The knowledge questions were modeled after the Maternal Serum Screening Knowledge Questionnaire (Goel et al. 1996) but updated to include NIPT. The post-consultation survey consisted of 24 questions for both groups, consisting of nine questions related to preparedness for the consultation and the 15 knowledge-based questions from the pre-consultation survey, with an additional six questions related to satisfaction with using the app for the intervention arm only (see Online Resource 1, Supplementary Table 2). Finally, each participant’s care provider was asked to complete a short provider survey consisting of five questions related to the length of time spent counseling about screening and testing options and subjective assessments of the participant’s preparedness for the consultation and knowledge level (see Online Resource 1, Supplementary Table 3).

The pre-consultation survey was completed after using the app-based tool but prior to consultation with their prenatal care provider in the intervention arm and prior to consultation with their prenatal care provider in the control arm. Participants in both arms completed the post-consultation survey following consultation with their prenatal care provider. The participants’ prenatal care provider completed the provider survey following the consultation with the participant. The surveys were conducted through SurveyMonkey on a device provided to the participants at their appointments. Unique participant codes were used to link each participant’s surveys. Participants that failed to complete both surveys were excluded from the analysis, regardless of whether the provider survey was completed for that participant.

Statistical analyses

Knowledge scores and rating questions were calculated by summing the responses using − 2, − 1, 0, 1, 2 points corresponding to the five-point Likert scale answer. A value of 2 is assigned if the correct response was given with a “strongly” agree or disagree, and a value of 1 for correct response with an agree or disagree statement. Incorrect responses are assigned a value of − 2 and − 1, respectively, while a value of 0 is assigned for a neutral response. Given 15 knowledge questions, the potential range for knowledge scores was − 30 to 30. Knowledge and satisfaction scores for each participant and summary statistics including mean, standard deviation, and range were calculated. Comparisons between groups were analyzed by Chi-square for categorical variables, ANOVA for continuous variables between three or more groups, and t tests for continuous variables between two groups.

Power calculations were based upon a two-sided t test assuming equal variance using PASS 15, assuming a standard deviation of around 15% in knowledge scores and with a goal of being able to detect a 10% absolute difference in knowledge score (e.g., 60% in controls and 70% in intervention group) and suggested a minimum number of participants of 60 per arm (120 total). We over-recruited due to possible additional variance based on provider and geography.

Results

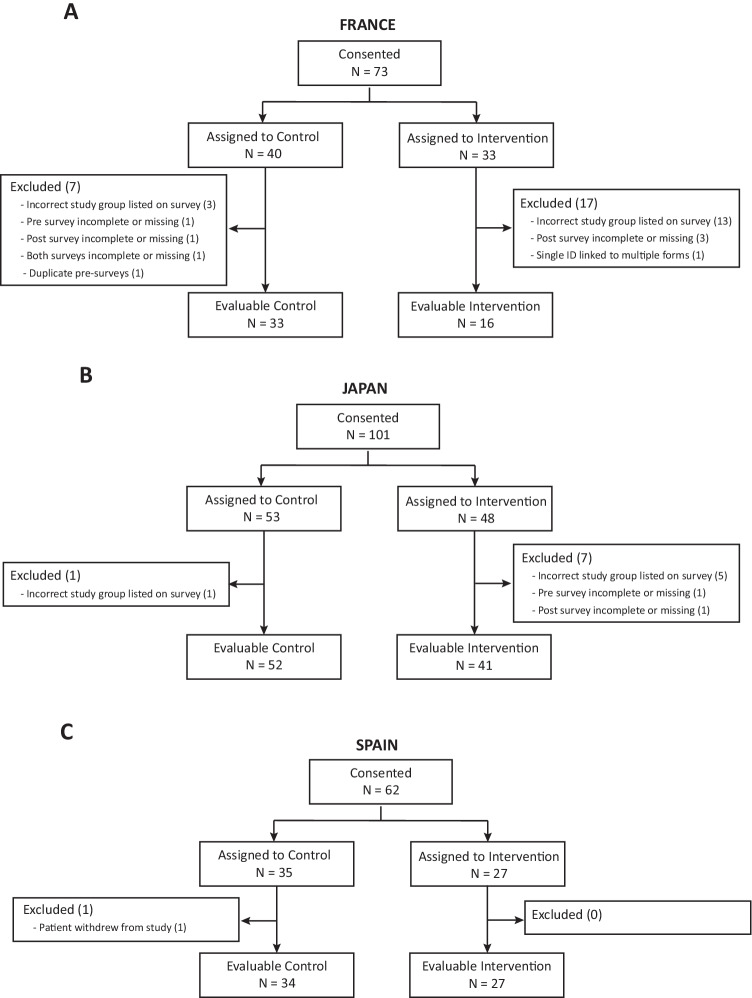

A total of 236 people agreed to participate in the study across the three sites. Of these, 203 (86%) completed the pre-survey and the post-survey and were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). A total of 33 participants were excluded from the analysis: 22 listed the incorrect study group on their survey; eight had a missing or incomplete pre- and/or post-survey; one submitted more than one pre-survey; one had the same ID linked to multiple forms; and one patient withdrew from the study. Provider surveys were completed for 203 (100%) of the included participants. Table 1 shows the demographics of the study population.

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart

Table 1.

Demographics of the study population

| Characteristic | France | Japan | Spain | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | |

| N | 33 | 16 | 52 | 41 | 34 | 27 | 119 | 84 |

| Age | ||||||||

| 18–24 years | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0(0%) | 1(1%) |

| 25–34 years | 18 (55%) | 9 (56%) | 9 (17%) | 7 (17%) | 19 (56%) | 16 (59%) | 46 (39%) | 32 (38%) |

| ≥ 35 years | 15 (45%) | 7 (44%) | 43 (83%) | 34 (83%) | 15 (44%) | 10 (37%) | 73 (61%) | 51 (61%) |

| Gestational age | ||||||||

| < 10 weeks | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) |

| 10–14 weeks | 19 (58%) | 8 (50%) | 44 (85%) | 34 (83%) | 34 (100%) | 26 (96%) | 97 (82%) | 68 (81%) |

| 15 weeks | 14 (42%) | 8 (50%) | 8 (15%) | 6 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (18%) | 14 (17%) |

| Number prior pregnancies | ||||||||

| 0 | 5 (15%) | 2 (13%) | 19 (37%) | 14 (34%) | 15 (44%) | 12 (44%) | 39 (33%) | 28 (33%) |

| 1 | 7 (21%) | 4 (25%) | 16 (31%) | 10 (24%) | 10 (29%) | 7 (26%) | 33 (28%) | 21 (25%) |

| 2 or more | 21 (64%) | 10 (63%) | 17 (33%) | 17 (41%) | 9 (26%) | 8(30%) | 47 (39%) | 35(42%) |

| Number of children | ||||||||

| 0 | 8 (24%) | 5 (31%) | 34 (65%) | 19 (46%) | 17 (50%) | 17 (63%) | 59 (50%) | 41 (49%) |

| 1 | 13 (39%) | 6 (38%) | 13 (25%) | 15 (37%) | 10 (29%) | 9 (33%) | 36 (30%) | 30 (36%) |

| 2 or more | 12 (36%) | 5 (31%) | 5 (10%) | 7 (17%) | 7 (21%) | 1 (4%) | 24 (20%) | 13 (15%) |

| Prior pregnancy with Down syndrome | ||||||||

| Yes | 3 (9%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (6%) | 5 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (5%) | 5 (6%) |

| No | 30 (91%) | 16 (100%) | 49 (94%) | 36 (88%) | 34 (100%) | 27 (100%) | 113 (95%) | 79 (94%) |

| Highest level of education | ||||||||

| No formal qualifications | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| High school and/or apprenticeship | 3 (9%) | 2 (13%) | 7 (13%) | 7 (17%) | 11 (32%) | 5 (19%) | 21 (18%) | 14 (17%) |

| Bachelors or equivalent | 6 (18%) | 2 (13%) | 39 (75%) | 31 (76%) | 4 (12%) | 6 (22%) | 49 (41%) | 39 (46%) |

| Graduate or higher | 22 (67%) | 12 (75%) | 6 (12%) | 3 (7%) | 19 (56%) | 15 (56%) | 47 (39%) | 30 (36%) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Black/African/Caribbean/N African | 14 (42%) | 5 (31%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 15 (13%) | 5 (6%) |

| East Asian/South Asian/Japanese | 0 (0%) | 2 (13%) | 52 (100%) | 41 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 52 (47%) | 43 (51%) |

| Mixed/Multiple or Other | 1 (3%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| South American/Latin American | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (2%) | 2 (2%) |

| White | 18 (55%) | 8 (50%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (88%) | 22 (81%) | 48 (40%) | 30 (36%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) |

| Primary language at home | ||||||||

| French | 31 (94%) | 15 (94%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (26%) | 15 (18%) |

| Japanese | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 51 (98%) | 41 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 51 (43%) | 41 (49%) |

| Spanish | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (94%) | 25 (93%) | 32 (27%) | 25 (30%) |

| English | 1 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 1 (3%)a | 1 (6%)b | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%)c | 2 (7%)¶d | 3 (3%) | 3 (4%) |

| Prior screening or testing | ||||||||

| None | 7 (21%) | 2 (13%) | 46 (88%) | 38 (93%) | 26 (76%) | 22 (81%) | 79 (66%) | 62 (74%) |

| Amniocentesis | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) |

| Serum screening | 11 (33%) | 6 (38%) | 3 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (4%) | 16 (13%) | 7 (8%) |

| Ultrasound | 5 (15%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 2 (6%) | 1 (4%) | 7 (6%) | 3 (4%) |

| Serum screening and | 9 (27%) | 6 (38%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 9 (8%) | 7 (8%) |

| Ultrasound | ||||||||

| Other, Unsure, or Unanswered | 1 (3%) | 1 (6%) | 1 (2%) | 1 (2%) | 4 (12%) | 3 (11%) | 6 (5%) | 5 (6%) |

Values are shown as n (%)

aPortuguese

bArabic

cArabic and German

dArabic and Romanian

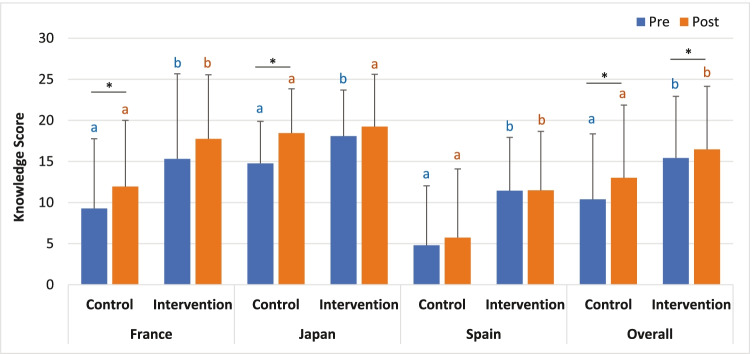

Overall, the mean knowledge scores in the participants using the app were significantly higher both pre-consultation (10.4 ± 8.0 vs. 15.4 ± 7.5; p < 0.001) and post-consultation (13.0 ± 9.9 vs. 16.5 ± 7.7; p < 0.005) than those in participants not using the app (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The mean knowledge score for the intervention group was 15 pre-consultation vs 16 post-consultation (p = 0.03) and for the control group was 10 pre-consultation and 13 (range, − 11–30; SD 8.8) post-consultation (p < 0.001). Although there was wide variation across the study sites, higher pre-consultation knowledge scores in participants using the app were observed at all sites (Table 2). The control groups at each site showed a larger improvement in knowledge scores from pre-survey to post-survey, suggesting that participants in the intervention group already had some of the knowledge typically discussed in consultation prior to meeting with their provider.

Table 2.

Knowledge scores of study participants

| Pre-survey knowledge | Post-survey knowledge | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control Mean ± SD Range |

Intervention Mean ± SD Range |

P value | Control Mean ± SD Range |

Intervention Mean ± SD Range |

P value | |

| Overall |

10.4 ± 8.0 - 7 - 26 |

15.4 ± 7.5 - 4 -30 |

< 0.001 |

13.0 ± 8.8 - 11 - 30 |

16.5 ± 7.7 2 - 30 |

0.004 |

| Spain |

4.8 ± 7.2 - 6 - 26 |

11.4 ± 6.5 2 - 27 |

< 0.001 |

5.7 ± 8.4 - 11 - 24 |

11.5 ± 7.2 - 2 - 25 |

0.006 |

| France |

9.3 ± 8.5 7 - 24 |

15.3 ± 10.4 4 - 30 |

0.035 |

11.9 ± 8.1 - 2 - 25 |

17.8 ± 7.8 6 - 28 |

0.021 |

| Japan |

14.8 ± 5.1 5 - 26 |

18.1 ± 5.6 5 -29 |

0.004 |

18.4 ± 5.4 7 - 30 |

19.2 ± 6.4 5 - 30 |

0.513 |

Fig. 2.

Impact of using an educational app on knowledge scores before and after physician visit. The control arm completed the pre-survey before their appointment with their health care provider. The intervention group completed the pre-knowledge survey after use of the educational app that provided information on prenatal testing but prior to their appointment with their health care provider. Both arms completed the post-survey immediately after their appointment with their health care provider. Different letters indicate a significant difference (p < 0.05) between pre- and post-knowledge scores within the control or intervention group

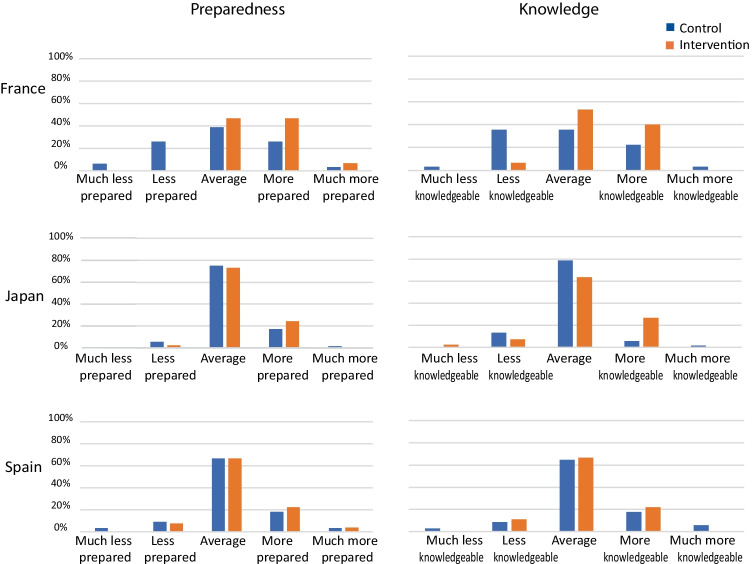

Most participants (137/203; 67%) indicated they felt they had enough information about prenatal screening and testing options prior to their appointment (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). There was a wide variation in the amount of time and the resources used to gather information for the appointment (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 2). The number of participants indicating they had enough information increased after their appointment (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 1) to 179/203 (88%). In addition, 79% of participants stated they felt “Prepared” or “Very Prepared” to discuss screening and testing options with their provider (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 1). Interestingly, when the participants’ providers were asked to subjectively rate the participants’ levels of knowledge and preparedness for the appointment (Fig. 3), participants in the intervention group had higher preparedness scores than the control group (p = 0.027); provider assessment of knowledge was not significantly different between the groups (p = 0.073). For provider assessment of patient preparedness and knowledge at a country level, the only significant finding was higher preparedness in France (p = 0.020). Participants in both groups overwhelmingly reported knowing the differences in various prenatal screening and testing options (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Provider rating of preparedness and knowledge

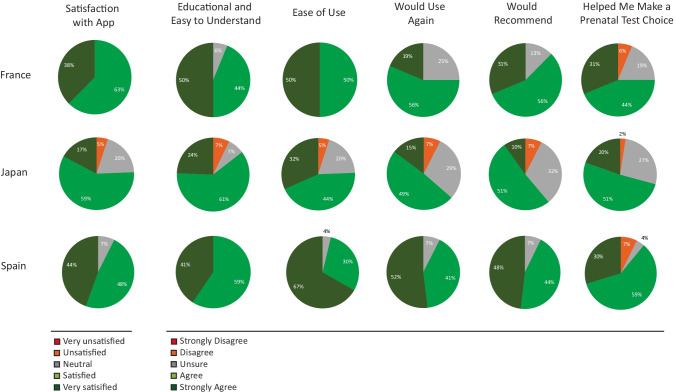

Participants reported high satisfaction levels with the app (Fig. 4). Across sites the majority (86%) of participants using the app stated they were “Satisfied” or “Very Satisfied” with the patient educational app as a tool to learn more about prenatal screening and testing options. Most agreed the app was easy to use, easy to understand, and helped them make a prenatal test choice. In addition, most would use the app again and would recommend the app to others. Participants indicated multiple benefits to using the app and, to a lesser extent, some potential concerns with use of the app (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

App satisfaction and ratings

On average, providers reported spending 16.3 min and 16.5 min discussing prenatal screening and testing options with participants in the control and intervention groups, respectively (p = 0.91). Of note, the time reported by providers varied between countries, with Spain typically reporting the lowest amount of time and Japan reporting the highest amount of time (see Online Resource 2, Supplementary Fig. 5). Within countries, there was no significant difference in the average time providers reported spending with patients between groups. Overall, most participants (92%) felt they had sufficient time to discuss prenatal screening and testing options with their providers. Interestingly, participants from France and Spain generally estimated they spent more time with the provider than reported by the provider.

Discussion

We showed that the NIPT Insights educational app in conjunction with provider consultation increased patient knowledge about prenatal screening and testing options more than consultation alone. Participants with app access had higher knowledge scores pre- and post-consultation than those without app access. There was no difference in the time providers spent counseling about prenatal options between the two arms; however, providers did subjectively rate those with access to the app as more prepared for their consultation.

Sufficient knowledge is one component of informed choice. Prior to the introduction of NIPT, studies consistently demonstrated people had low-level understanding of prenatal aneuploidy screening (Gourounti and Sandall 2008; Jaques et al. 2004; Pop-Tudose et al. 2018; van den Berg et al. 2005), which persists in the NIPT era (Abousleiman et al. 2019). One-third of patients make uninformed choices regarding NIPT acceptance, predominantly due to insufficient knowledge (Beulen et al. 2016; Lewis et al. 2017). In one study of pregnant people with low-risk NIPT results in the current pregnancy, only 44% were able to correctly answer at least six of eight statements about NIPT and only 10% correctly answered all eight (Piechan et al. 2016). This effect is likely magnified in those with lower educational levels and lower health literacy and numeracy, who have been shown to have lower knowledge scores for prenatal genetic testing (Cho et al. 2007). The high educational status of participants in this study precludes examination of the potential effectiveness of an app-based tool in people with lower educational levels. More recently, studies have shown that pregnant people in France (Wehbe et al. 2020) and the USA (Palomaki et al. 2017) are more knowledgeable about aneuploidy screening and NIPT than previously suggested.

Professional societies emphasize the need for pre-test counseling to facilitate informed decision-making. With expanding use and testing options of NIPT, there is a growing need to explore alternative counseling approaches. We demonstrated that an app-based educational tool increased knowledge. Other studies investigating alternative service delivery models show mixed results. Patient knowledge and self-reported understanding was shown to be positively impacted by use of educational videos (de Leeuw et al. 2019; Mulla et al. 2018). A randomized controlled trial in the USA found that using a computerized interactive decision support guide significantly increased informed choice of people considering amniocentesis (Kuppermann et al. 2014). Similarly, another US-based randomized control trial showed people using interactive technology in addition to standard counseling for prenatal screening demonstrated better knowledge than people receiving provider counseling only; this was consistent across diverse educational, health literacy, and electronic literacy backgrounds, suggesting that digital tools may be widely applicable (Yee et al. 2014). A similar trial in the Netherlands found a significant increase in informed reproductive decision-making associated with use of a web-based multimedia decision aid (Beulen et al. 2016). Carlson et al. demonstrated that knowledge scores in people using a computerized decision aid were not inferior to those of people having genetic counseling (Carlson et al. 2019). Conversely, Skjoth et al. failed to find a significant impact on informed choice with use of an interactive website (Skjøth et al. 2015) and a study in Thailand found that computer-assisted instruction was less effective in improving patient knowledge scores than was individual counseling in combination with a self-read leaflet in patients considering amniocentesis (Hanprasertpong et al. 2013).

Prenatal health care providers acknowledge a lack of time to adequately counsel pregnant patients about prenatal screening options (Gammon et al. 2016). This was echoed by findings of a meta-synthesis of patients’ experiences with NIPT, in which some patients felt that consultations were too short to address their questions and concerns (Cernat et al. 2019), probably influenced by background characteristics, experience, attitudes, and knowledge (Nishiyama et al. 2021). Patients described feeling overwhelmed by the amount of information and the limited time in which to process it (Cernat et al. 2019). In a survey of US-based obstetrical providers, the average time spent on pre-test discussion with the patient was 6 min (range, 2.5–15 min) (Palomaki et al. 2017). Here, the time providers reported spending with patients varied between countries. Most participants indicated they had enough information and sufficient time with their provider to discuss testing options. App use did not appear to impact the amount of time spent in consultation with a provider but may have positively impacted participants’ preparedness for this discussion, as assessed by their providers.

Here, 86% of intervention participants reported satisfaction with the app. Previous studies suggested that many pregnant people considering NIPT prefer getting information a few days before testing (Laberge et al. 2019; Lewis et al. 2014), involving partners in the decision-making process (Laberge et al. 2019; Portocarrero et al. 2017), and having information accessible at home (Portocarrero et al. 2017). This was reflected in app benefits reported by participants of this study. However, patients also strongly value consultation with their providers (Laberge et al. 2019), which was echoed by our findings with 5% of participants preferring only a provider consultation.

Strengths of this study include the randomized design and inclusion of geographically diverse regions, demonstrating the intervention effectiveness in different settings. Limitations of the study include differing routine care at each site, which may have impacted patient knowledge as measured in the post-survey. In addition, the baseline knowledge was not assessed in the intervention group. Given the high educational level of participants, we could not assess the impact of an app-based intervention in people with lower health literacy. In addition, participants were provided with access to NIPT Insights at the time of their testing appointment, rather than prior to the appointment as we would recommend for routine clinical use.

As NIPT use expands into routine clinical care for all pregnant people and in complexity with screening for a growing number of conditions, educational tools to facilitate pre-test counseling are needed. Educational tools, such as NIPT Insights, can provide the foundational information necessary to prepare pregnant people for consultation with their providers. An app-based approach addresses many of the preferences reported by pregnant people regarding pre-test counseling by providing information before a testing decision needs to be made and enabling them to reflect on the information in their home with their partner or other support persons. Importantly, equipping pregnant people with information prior to their consultation allows health care providers to utilize their limited consultation time to address specific questions and explore a patient’s values and beliefs, facilitating informed choice through shared decision-making. This study shows that clinical implementation of a patient educational app in a real-world setting was feasible, acceptable to pregnant people, and positively impacted patient knowledge.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Letourneau for managing the daily operations (site coordinator and recruitment) as well as the contributions of Miriam Sanchez and Miguel Rodriguez at the French study site. In addition, from Illumina, Inc., we thank Patty Taneja and Holly Snyder for their work in developing the NIPT Insights app, Kristin Dalton and Jake Massa for their work in identifying study sites, and Darcy Vavrek for her statistical support and guidance.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation and data collection were performed by Alexandra Benachi, Maria Mar Gil, Belen Santacruz, Miyuki Nishiyama, Fuyuki Hasegawa, and Haruhiko Sago. Data analysis was performed by Kirsten Jane Curnow. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Patricia Winters and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Illumina, Inc.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study. This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. The study was approved by relevant local Ethics Boards at each site. For the French site, the study protocol received Institutional Review Board approval by the Comité d’Ethique de la Recherche en Obstétrique et Gynécologie Ethical Review Committee (submission number CEROG 2018-OBS-0707) in 2018. For the Japan site, the study protocol was approved by Institutional Review Board at National Center for Child Health and Development on September 3, 2020 (project number 2020–088). For the Spain site, the study protocol was approved by Ethics Committee for the Hospital Universitario De Torrevieja and Hospital Universitario Del Vinalopo on September 25, 2019.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Conflict of interest

Patricia Winters and Kirsten Curnow are employed by and own stock in Illumina, Inc. Alexandra Benachi, Maria Mar Gil, Belen Santacruz, Miyuki Nishiyama, Fuyuki Hasegawa, and Haruhiko Sago declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abousleiman C, Lismonde A, Jani JC. Concerns following rapid implementation of first-line screening for aneuploidy by cell-free DNA analysis in the Belgian healthcare system. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2019;53:847–848. doi: 10.1002/uog.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beulen L, van den Berg M, Faas BH, Feenstra I, Hageman M, van Vugt JM, Bekker MN. The effect of a decision aid on informed decision-making in the era of non-invasive prenatal testing: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24:1409–1416. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LM, Harris S, Hardisty EE, Hocutt G, Vargo D, Campbell E, Davis E, Gilmore K, Vora NL. Use of a novel computerized decision aid for aneuploidy screening: a randomized controlled trial. Genet Med. 2019;21:923–929. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0283-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernat A, De Freitas C, Majid U, Trivedi F, Higgins C, Vanstone M. Facilitating informed choice about non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT): a systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis of women's experiences. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:27. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2168-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho RN, Plunkett BA, Wolf MS, Simon CE, Grobman WA. Health literacy and patient understanding of screening tests for aneuploidy and neural tube defects. Prenat Diagn. 2007;27:463–467. doi: 10.1002/pd.1712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Leeuw RA, van der Horst SFB, de Soet AM, van Hensbergen JP, Bakker P, Westerman M, de Groot CJM, Scheele F. Digital vs face-to-face information provision in patient counselling for prenatal screening: A noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39:456–463. doi: 10.1002/pd.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gammon BL, Kraft SA, Michie M, Allyse M. "I think we've got too many tests!": Prenatal providers' reflections on ethical and clinical challenges in the practice integration of cell-free DNA screening. Ethics Med Public Health. 2016;2:334–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jemep.2016.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil MM, Accurti V, Santacruz B, Plana MN, Nicolaides KH. Analysis of cell-free DNA in maternal blood in screening for aneuploidies: updated meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;50:302–314. doi: 10.1002/uog.17484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goel V, Glazier R, Holzapfel S, Pugh P, Summers A. Evaluating patient's knowledge of maternal serum screening. Prenat Diagn. 1996;16:425–430. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0223(199605)16:5<425::Aid-pd874>3.0.Co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourounti K, Sandall J. Do pregnant women in Greece make informed choices about antenatal screening for Down's syndrome? A questionnaire survey. Midwifery. 2008;24:153–162. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanprasertpong T, Rattanaprueksachart R, Janwadee S, Geater A, Kor-anantakul O, Suwanrath C, Hanprasertpong J. Comparison of the effectiveness of different counseling methods before second trimester genetic amniocentesis in Thailand. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33:1189–1193. doi: 10.1002/pd.4222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaques AM, Halliday JL, Bell RJ. Do women know that prenatal testing detects fetuses with Down syndrome? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:647–651. doi: 10.1080/01443610400007885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kater-Kuipers A, de Beaufort ID, Galjaard RH, Bunnik EM. Ethics of routine: a critical analysis of the concept of 'routinisation' in prenatal screening. J Med Ethics. 2018;44:626–631. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2017-104729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuppermann M, Pena S, Bishop JT, Nakagawa S, Gregorich SE, Sit A, Vargas J, Caughey AB, Sykes S, Pierce L, Norton ME. Effect of enhanced information, values clarification, and removal of financial barriers on use of prenatal genetic testing: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:1210–1217. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laberge AM, Birko S, Lemoine M, Le Clerc-Blain J, Haidar H, Affdal AO, Dupras C, Ravitsky V. Canadian pregnant women's preferences regarding NIPT for Down syndrome: the information they Want, how they want to get it, and with whom they want to discuss it. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:782–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Hill M, Silcock C, Daley R, Chitty LS. Non-invasive prenatal testing for trisomy 21: a cross-sectional survey of service users' views and likely uptake. BJOG. 2014;121:582–594. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.12579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis C, Hill M, Chitty LS. Offering non-invasive prenatal testing as part of routine clinical service. Can high levels of informed choice be maintained? Prenat Diagn. 2017;37:1130–1137. doi: 10.1002/pd.5154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Dormandy E, Michie S. A measure of informed choice. Health Expect. 2001;4:99–108. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2001.00140.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulla BM, Chang OH, Modest AM, Hacker MR, Marchand KF, O'Brien KE. Improving patient knowledge of aneuploidy testing using an educational video: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132:445–452. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000002742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishiyama M, Ogawa K, Hasegawa F, Sekido Y, Sasaki A, Akaishi R, Tachibana Y, Umehara N, Wada S, Ozawa N, Sago H. Pregnant women's opinions toward prenatal pretest genetic counseling in Japan. J Hum Genet. 2021;66:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s10038-021-00902-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomaki GE, Kloza EM, O'Brien BM, Eklund EE, Lambert-Messerlian GM. The clinical utility of DNA-based screening for fetal aneuploidy by primary obstetrical care providers in the general pregnancy population. Genet Med. 2017;19:778–786. doi: 10.1038/gim.2016.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechan JL, Hines KA, Koller DL, Stone K, Quaid K, Torres-Martinez W, Wilson Mathews D, Foroud T, Cook L. NIPT and informed consent: an assessment of patient understanding of a negative NIPT result. J Genet Couns. 2016;25:1127–1137. doi: 10.1007/s10897-016-9945-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop-Tudose ME, Popescu-Spineni D, Armean P, Pop IV. Attitude, knowledge and informed choice towards prenatal screening for Down Syndrome: a cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18:439. doi: 10.1186/s12884-018-2077-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portocarrero ME, Giguère AM, Lépine J, Garvelink MM, Robitaille H, Delanoë A, Lévesque I, Wilson BJ, Rousseau F, Légaré F. Use of a patient decision aid for prenatal screening for Down syndrome: what do pregnant women say? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:90. doi: 10.1186/s12884-017-1273-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravitsky V, Roy MC, Haidar H, Henneman L, Marshall J, Newson AJ, Ngan OMY, Nov-Klaiman T. The emergence and global spread of noninvasive prenatal testing. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2021;22:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-083118-015053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skjøth MM, Draborg E, Lamont RF, Pedersen CD, Hansen HP, Ekstrøm CT, Jørgensen JS. Informed choice about Down syndrome screening—effect of an eHealth tool: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94:1327–1336. doi: 10.1111/aogs.12758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg M, Timmermans DR, Ten Kate LP, van Vugt JM, van der Wal G. Are pregnant women making informed choices about prenatal screening? Genet Med. 2005;7:332–338. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000162876.65555.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehbe K, Brun P, Gornet M, Bory JP, Raimond É, Graesslin O, Barbe C, Duminil L. DEPIST 21: Information and knowledge of pregnant women about screening strategies including non-invasive prenatal testing for Down syndrome. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2020;50:102001. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.102001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee LM, Wolf M, Mullen R, Bergeron AR, Cooper Bailey S, Levine R, Grobman WA. A randomized trial of a prenatal genetic testing interactive computerized information aid. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:552–557. doi: 10.1002/pd.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.