Abstract

Aims

Black, Asian and minority ethnic women are at higher risk of dying during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatally and of experiencing premature birth, stillbirth or neonatal death compared with their White counterparts. Discrimination against women from ethnic minorities is known to negatively impact women's ability to speak up, be heard and their experiences of care. This evidence synthesis analysed Black, Asian and minority ethnic women's experiences of UK maternity services in light of these outcomes.

Design

We conducted a systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis using the method of Thomas and Harden.

Data Sources

A comprehensive search in AMED, Cinahl, Embase, Medline, PubMed and PsycINFO, alongside research reports from UK maternity charities, was undertaken from 2000 until May 2021. Eligible studies included qualitative research about antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care, with ethnic minority women in maternity settings of the UK NHS.

Review Methods

Study quality was graded using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool.

Results

Twenty‐four studies met the inclusion criteria. Our synthesis highlights how discriminatory practices and communication failures in UK NHS maternity services are failing ethnic minority women.

Conclusion

This synthesis finds evidence of mistreatment and poor care for ethnic minority women in the UK maternity system that may contribute to the poor outcomes reported by MBRRACE. Woman‐centred midwifery care is reported as positive for all women but is often experienced as an exception by ethnic minority women in the technocratic birthing system.

Impact

Ethnic minority women report positive experiences when in receipt of woman‐centred midwifery care. Woman‐centred midwifery care is often the exception in the overstretched technocratic UK birthing system. Mistreatment and poor care reported by many ethnic minority women in the UK could inform the inequalities of outcomes identified in the MBRRACE report.

Keywords: ethnic minority, literature review, maternity, meta‐synthesis, UK

1. INTRODUCTION

The ‘Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk through Audits and Confidential Enquiries’ (MBRRACE‐UK) audit confirmed that Black, Asian and minority ethnic women are at higher risk of dying during pregnancy, childbirth and postnatally and of experiencing premature birth, stillbirth or neonatal death compared with their White counterparts (Knight et al., 2020). Published explanations for these inequalities are complex and include a combination of contributing factors: organizational, language and cultural, help‐seeking and access barriers (Aquino et al., 2015, Fisher & Fraser, 2020, Henderson et al., 2018, Murray et al., 2010). Much of the evidence comes from international literature rather than the UK specifically and reflects different social, cultural and historical experiences. MBRRACE highlighted the need to review the evidence related to the UK health system.

2. BACKGROUND

Feeling cared for (Beake et al., 2013; Redshaw & Heikkila, 2011), staff attitudes (Rayment‐Jones et al., 2019) and communication (Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Wikberg et al., 2012) have been reported as being important by the whole population of birthing women. Yet experiences of negative stereotyping and lack of ‘cultural competence’ among maternity staff reveal dimensions of poor care experiences unique to women from ethnic minorities (Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013). Stereotyping and pre‐conceived ideas about women from ethnic minorities negatively impact women's ability to speak up and their experience of care (Hoffman et al., 2016; Puttusery et al., 2008). Such attitudes reinforce a ‘Them and Us’ approach that expects ethnic minority women to adapt to an insensitive and sometimes discriminatory health system rather than the system being responsive to the needs of the women (Lyons et al., 2008). There is a significant body of literature (largely from the USA) that co‐implicates social, economical and political forces in producing the stigma and inequality experienced in negative encounters with health services. These negative encounters include attempts at service engagement being rebuffed (Davis, 2019; Metzl & Hansen, 2014; O'Mahony & Donnelly, 2010).

3. THE REVIEW

3.1. Aim

The aim of this review was to synthesize the published qualitative evidence about Black, Asian and minority ethnic women's experiences of UK maternity services in light of the disparities reported in maternity outcomes between different groups of women.

3.2. Design

We used a thematic evidence synthesis method to extend the interpretations offered in the original individual studies included in this review (Thomas & Harden, 2008).

3.3. Search method

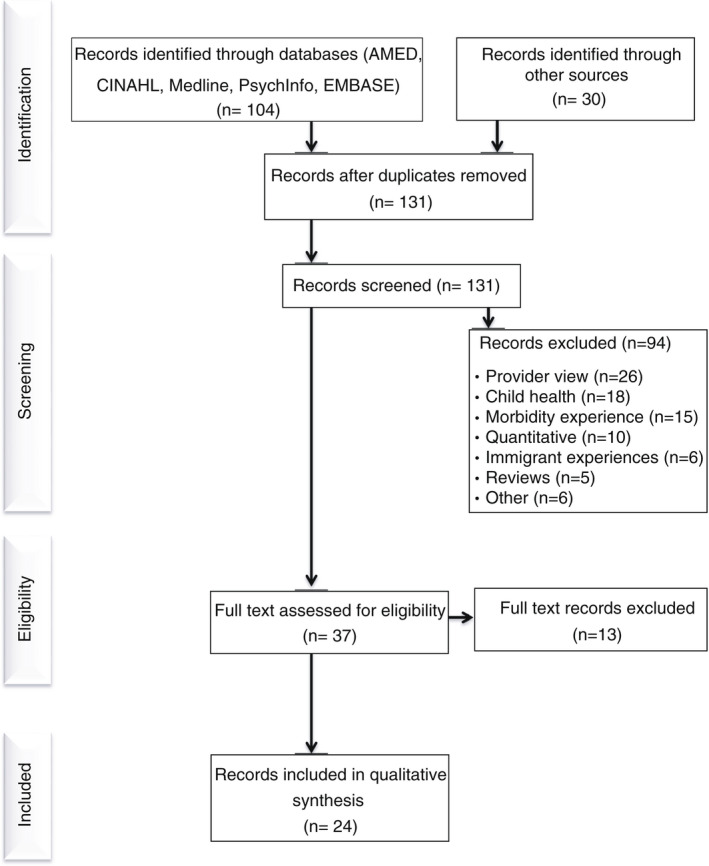

We registered our review on the PROSPERO database (MacLellan et al., 2020), followed the PRISMA guidance (Page et al., 2021; Rethlefsen et al., 2021) and used PICO (Population, Interest, COntext) to structure systematic searches for qualitative studies where Population = Black, Asian and minority ethnic women, Interest = Experiences, COntext = UK maternity services (Miller, 2001). The acronym ‘BAME’ was used in searching due to its consistent use in the preceding 20 years, but in line with recent UK government guidance, we use the term ‘ethnic minorities’ to include Black, Asian and other minority ethnic people. This update in terminology is an acknowledgement that the concept of ‘race’ refers to a shared culture and history among a group of people rather than skin colour. While MBRRACE did not include this group in their description of racial inequalities, the inclusion of the experiences of white minoritized ethnicities such as Orthodox Jewish, Gypsy, Roma and Irish Travellers is appropriate to our synthesis (Race Disparity Unit, 2021). Searches were carried out in December 2020 in AMED, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and MEDLINE databases, published in English from 2000. This cut‐off date was chosen as there was a major change in the maternity system approach in the late 1990s with the Changing Childbirth report, to woman‐centred care (Department of Health, 1993, 1997). For full search strategy, see Table 1: Search strategy. In addition, we used backwards citation tracking, Pubmed ‘related articles’, Google Scholar and research outputs of UK maternity and advocacy charities. Searches were repeated in May 2021 and yielded no additional records (Figure 1).

TABLE 1.

Literature search terms

| Population | Interest | Context | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BAME or Black or Asian or Minority Ethnic | Maternity Service or Antenatal or Postnatal or Childbirth | Experience or Perception or Attitude or View | NHS or National Health Service or the UK or the United Kingdom |

| Orthodox Jewish, Jewish and Judaism | |||

| Traveller community or travelling community or travellers or Gypsy traveller or Roma | |||

FIGURE 1.

Literature search results

3.4. Search outcome

We included studies that reported qualitative (interpretive and textual) data about antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal care, with ethnic minority women in primary and secondary care settings. We excluded papers about the experience of asylum seekers and women without recourse to public funds due to their unique financial and immigration concerns. Other exclusions were papers focused on morbidity, child health or the impact of COVID‐19. Studies reporting only professional perspectives were also excluded.

3.5. Quality appraisal

Study quality was graded using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tool for qualitative studies (CASP, 2019). Two reviewers (JM and SC) graded the papers independently, conferred on a random selection of 12 papers, with the third reviewer available to resolve any disparities (TR). While CASP does not advocate a scoring system, the majority of included papers achieved ‘yes’ on eight domains or more. As recommended by Atkins et al. (2008), papers were not excluded as a result of a low score but were integrated into the synthesis with these concerns made explicit. In all but one instance, the findings of the lower quality papers were corroborated by two or more high‐quality papers, adding confidence to the findings. In the single incidence, a confidence statement follows the report of the finding. We also examined the relative contributions of each study to the final analytic themes (Table 3: Theme contribution of included papers).

TABLE 3.

Thematic map and theme contribution of papers

| Analytical theme | Descriptive theme | Codes | Contributing paper |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power of the technocratic birthing system | Accountability to the institution rather than to the woman | Functional versus woman‐centred care | 1, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21, 22 |

| Decontextualizing women, ritualized care | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14, 19, 21 | ||

| Resource barriers | 5, 6, 13, 19, 21 | ||

| Communication failures | Avoidance of complexity | Inadequate information or signposting | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 10, 13, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24 |

| Compromised consent | 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 17 | ||

| Language | 1, 2, 6, 8, 11, 13, 15, 19, 23 | ||

| Interpreters | 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 11, 14, 17, 21 | ||

| Mistreatment of women | Differential treatment | Discrimination and prejudice | 1, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 14, 17, 24 |

| Isolating | 1, 5, 6, 14, 16, 17, 18, 20, 23 | ||

| Unable to speak up/not listened to | 1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 16, 17, 18, 22 | ||

| Lack of care | 5,14,16,17,19,22 | ||

| Unkind | 6,7,8,11,14,16,17,24 | ||

| Woman‐centred care as exceptional, not routine | When resources allow engagement with the complexity of women's lives | Targeted service | 1,5,6,7 |

| Cultural safety | 1,2,4,6,10,12,14,16,24 | ||

| Continuity/trust | 2,3,5,6,7,10,14,16,17,18 | ||

| Non judgemental | 3,4,5,6,7,11,13,14,16,17,18, 22,23 |

3.6. Data abstraction

We collated records into an Excel database, removed duplicates and screened abstracts for inclusion against the inclusion/exclusion criteria (JM and SC). Full texts were screened independently by two researchers (JM and SC) with a third reviewer available to resolve any discrepancies (TR).

3.7. Synthesis

Findings and results sections of papers were extracted and entered verbatim into NVivo 12 software to support thematic analysis guided by Thomas and Harden (2008). This began with independent line‐by‐line inductive coding by two researchers (JM and SC), who then organized the codes into broad descriptive themes for discussion by the full research team to refine. Four major themes have identified that structure the presentation of our synthesis findings below.

4. RESULTS

Searching yielded 131 papers after removing duplicates, with 37 fulfilling our eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Thirteen of these did not report directly on maternity service experiences, leaving 24 for synthesis (Table 2). Study samples ranged from 7 to 219 participants, with a combined total of over 760 participants from a range of different self‐identified ethnic backgrounds or classified according to researcher ethnic criteria (n = 2). The principal method of data collection was semi‐structured interview (n = 21) or focus groups (n = 5). An interpreter or a bi‐lingual researcher was offered in 18 studies, with the remaining six being conducted exclusively in English. Studies that scored high on researcher reflexivity used non‐hierarchical language, collected data through peer researchers or culturally congruent researchers, recruited participants through community sources and scored higher in terms of quality. Poorer quality studies tended to be more descriptive than interpretive but nonetheless offered some valuable data. The synthesis identified four core themes about the experience of maternity services in the UK by women of Black, Asian and minority ethnicities. These are

birthing in a technocratic system

communication failures

mistreatment of women

woman‐centred care as exceptional, not routine

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of included studies

| No. | References | No. of participants | Time since gave birth | Sample | Data collection method | Research methodology | Sampling | Reflexivity | CASP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ali N. (2004) Experiences of Maternity Services: Muslim Women's Perspectives. London;The Maternity Alliance; [https://www.maternityaction.org.uk/wp‐] | 43 | In the last 3 years | Muslim mothers Bangladesh, Pakistan, Europe, Iraq, Somali, African, Indian | Focus group in chosen language with interpreter always present, creche provided | Mixed methods | Snowball through Muslim organizations and charities | None | 8 |

| 2 | Alshawish E, Marsden j, Yeowell G, Wibberley C. (2013) Investigating access to and use of maternity health‐care services in the UK by Palestinian women. British Journal of Midwifery 2013;21:8:571–577 | 22 | Unknown | Palestinian women in the UK | Semist interview in English or Arabic | Pragmatism, framework analysis | Snowball at school and mosque | Yes | 8 |

| 3 | Beake S, Acosta L, Cooke P, McCourt C. (2013) Caseload midwifery in a multi‐ethnic community: The woman's experiences. Midwifery;29:996–1002 | 16 | In the last 6 months | 16 ethnic minority women: Black, Indian, Oriental, Bangladeshi, Other | Semi‐structured interview, only English speakers responded | Framework analysis | Invite letters sent in English | None | 8 |

| 4 | Binder‐Finnema P, Borne Y, Johnsdotter S, Essen B. (2012) Shared language is essential: Communication in a multiethnicity obstetric care setting. Journal of Health Communication 17:1171–1186 | 60 | 2 days–10 years ago | 39 immigrant Somali, 11 Ghanaian, 10 White British women and 62 obstetric care providers | 23 interviews, 5 focus group discussions using cultural brokers and interpreters | Framework analysis, naturalistic inquiry | Snowball in Somali through cultural brokers | None | 7 |

| 5 | Birthrights. (2020) Holding it all together: Understanding how far the human rights of women facing disadvantage are respected during pregnancy, birth, postnatal care. London: Birthrights | 12 | In the last 3 years | 11 Black, Asian, minority ethnic women, 1 white European | Semi‐structured interviews with interpreter used in 1 | Thematic analysis | Through targetted support services | Yes | 9 |

| 6 | Cardwell, V. Wainwright, L. (2019) Making Better Births a reality for women with multiple disadvantages. A qualitative peer research study exploring perinatal women's experiences of care and services in north‐east London. Birth Companions and Revolving Doors Agency London. | 34 | In the last 5 years | Women of multiple disadvantages including ethnic minority status | Peer‐led semi‐structured interviews and 1 focus group discussion. Interpreters provided | Participatory research | Through targetted support services | Use of peer researchers | 10 |

| 7 | Cross‐Sudworth, F. Williams, A. Herron‐Marx, S. (2011) Maternity services in multi‐cultural Britain: Using Q methodology to explore the views of first‐ and second‐generation women of Pakistaani origin. Midwifery 27: 458–468 | 15 | In the 3–18 months ago | 1st & 2nd generation Pakistani women | semi‐structured interview, urdu interpreter available | Q methodology ‐ mixed methods, thematic and factor analysis | Self‐identified in response to leaflet in child centre | None | 10 |

| 8 | Davies, M.M. Bath, P.A. (2001) The maternity information concerns of Somali women in the United Kingdom. Journal of Advanced Nursing; 36: 2: 237–245 | 13 | Unknown | Somali women in the UK less than 10 years | Semi‐structured interview and focus group discussion with a translator | Grounded Theory | Invited by a community health worker and project interpreter | Yes | 8 |

| 9 | Finigan, V. Long, T. (2014) Skin‐to‐skin contact: multicultural perspectives on birth fluids and birth ‘dirt’. International Nursing Review 61: 270–277 | 20 | 1–2 days | English, Pakistani, Bangladeshi | Audiotaped diaries, semi‐structured interviews, photographs and video recordings with NHS translation | Phenomenology | Unclear | Yes | 5 |

| 10 | Goodwin, L. Hunter, B. Jones, A. (2017) The midwife‐woman relationship in a South Wales community: Experiences of midwives and migrant Pakistani women in early pregnancy. Health Expectations 21: 347–357 | 9 | Still pregnant | Pakistani | Observation and interview, Interpreter offered | Ethnography | Recruited by MWs at Antenatal clinic | None | 10 |

| 11 | Harper Bulman, K. McCourt, C. (2002) Somali refugee women's experiences of maternity care in west London: A case study. Critical Public Health, 12:4, 365–380, DOI:10.1080/0958159021000029568 | 12 | Still pregnant + previous children | Somali | Int and focus group in Somali in women's house with an interpreter, findings discussed with women | Phenomenology/action research/not clear | Snowball | None | 8 |

| 12 | Hassan, S.M. Leavey, C. Rooney, J.S. (2019) Exploring English speaking Muslim women's first‐time maternity experiences: a qualitative longitudinal interview study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth 19: 156 doi: 10.1186/s12884‐019‐2302‐y | 7 | Still pregnancy | Muslim women from Yemen, Somalia, India +2 white British women | 3 in‐depth interviews with each woman, Antenataly, 2 and 4 months postnatally, in woman's home by the lead author in English | Qualitative longitudinal | Through women's groups | None | 5 |

| 13 | Jayaweera, H. D'Souza, L. Garcia, J. (2005) A local study of childbearing Bangladeshi women in the UK. Midwifery 21: 84–95 | 9 | Pregnant or in 1 year of giving birth | Low‐income Bangladeshi women in Leeds | 9 semi‐st interviews with women up to 1 year postpartum, 3 in woman's home by a researcher, 6 in Sylehti by org staff at the neighbourhood centre | Nested interview study principles of grounded theory | Approached by staff at family centres | None | 7 |

| 14 | Jomeen, J. Redshaw, M. (2013) Ethnic minority women's experience of maternity services in England. Ethnicity and Health, 18:3, 280–296 | 219 | 3 months ago | Women identified as BME on ONS record | Text responses to open questions in UK wide survey in English | Thematic analysis | ONS Survey text responses | Partly | 9 |

| 15 | Lam, E. Wittkowski, A. Fox, J.R.E. (2012) A qualitative study of the postpartum experience of Chinese women living in England. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology 30:1: 105–119 | 8 | In 1 year | Chinese | In‐depth interview in Chinese or English by researcher | Grounded theory | Poster at community centre | Yes | 9 |

| 16 | McAree, T. McCourt, C. Beake, S. (2010) Perceptions of group practice midwifery from women living in an ethnically diverse setting. Evidence based midwifery. 8:3: 91–97 | 12 | In 2–3 years | S. Asia, Somalia, Balkans | S‐St Int in women homes by bi‐lingual researcher 6 in English, 3 in Gujarati | Grounded Theory | By letter and phone to women using the maternity service in last year | Partly | 9 |

| 17 | McCourt, C. Pearce, A. (2000) Does continuity of carer matter to women from minority ethnic groups? Midwifery 16:145–154 | 26 | In 3–9 months | Caribbean, African, South and East Asian, Mediterranean, Middle Eastern women | Narrative Interview in womans home, 1 with somali translator | Principles of grounded theory | Follow‐up of survey non‐responders | None | 10 |

| 18 | McFadden, A. Siebelt, L. Jackson, C. Jones, H. Innes, N. MacGillivray, S. (2018) Enhancing Gypsy, Roma and Traveller peoples' trust. Report: University of Dundee | 42 | Unknown | Romany Gypsy, Irish Traveller and Eastern European Roma communities | 4 case studies with an interpreter | Thematic analysis | Through charities | None | 9 |

| 19 | Moxey, J.M. Jones, L.L. (2016) A qualitative study exloring how Somali women exposed to female genital mutilation experience and perceive antenatal and intrapartum care in England. BMJ Open 6:e009846 | 10 | In 5 years | Somali women, BMH | semi‐structured interview with a lay interpreter, known to the community, in an antenatal clinic | Descriptive qualitative but iterative rather than the framework | Snowball and convenience through community outreach workers | Yes | 9 |

| 20 | Ockleford EM; Berryman JC; Hsu R. (2004) Postnatal care: what new mothers say. British Journal of Midwifery. 12:3: 166–170 | 18 | In 3 months | White and Indian women | Semi‐structured interview by Gujarati speaker in woman's home | Content analysis | Recruited at booking visit with the midwife | None | 6 |

| 21 | Phillimore, J. (2016) Migrant maternity in an era of superdiversity: New migrants' access to, and experience of, antenatal care in the West Midlands, UK. Social Science and Medicine 148: 152–159 | 82 | In 5 years | 28 countries, including China, Iran, Pakistan and Poland | Mixed methods questionnaire +13 in‐depth interviews by poly‐lingual interviewers | Interpretive thematic analysis | Purposive from DoH database | None | 9 |

| 22 | Puttusery, S. Twamley, K. Macfarlane, A. Harding, S. Baron, M. (2010) ‘You need that tender loving care’: maternity care experiences and expectations of ethnic minority women born in the United Kingdom. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy 15:3:156–162 | 34 | In 1 year | UK‐born mothers of Black Caribbean, Black African, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Irish descent | Qual in‐depth interview by 2 researchers in woman's home in English | Grounded Theory | Through Midwives at Antenatal clinic | Partly | 9 |

| 23 | Watson, H. Soltani, H. (2019) Perinatal mental ill health: the experiences of women from ethnic minority groups.British Journal of Midwifery. 27:10: 642–648 | 51 | Unknown | 20 South Asian women, 31 from 14 different ethnic backgrounds, table of characteristics missing | Survey online and face to face in English | Mixed methods | None | 8 | |

| 24 | Wittkowski, A. Zumla, A. Glendenning, S. Fox, J.R.E. (2011) The experienceof postnatal depression in South Asian mothers living in Great Britain: a qualitative study, Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29:5, 480–492 | 10 | In 3 months | South Asian Mothers | Interview in English | Grounded theory | Health visitor and midwife recruited | Yes | 9 |

Abbreviation: CASP, Critical Appraisal Skills Programme.

5. BIRTHING IN A TECHNOCRATIC SYSTEM

Women of Black, Asian and minority ethnicities reported care to be functional rather than supportive that the maternity system was task focused, and failed to treat them as a person (Ali, 2004; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000) engendering feelings of being processed rather than being cared for (Beake et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; Ockleford et al., 2004; Puttusery et al., 2010). Among the women who reported their care as fragmented and task focused, they also described feeling the system was unable to engage with the complexity of their lives, with healthcare professionals assuming that they had access to childcare or transport, for example, which impacted women's ability to attend appointments (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Jayaweera et al., 2005; Moxey & Jones, 2016; Phillimore, 2016). They described feeling judged by healthcare providers when they requested support related to personal safety or resources during their antenatal appointments (Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Goodwin et al., 2017; Jayaweera et al., 2005; Phillimore, 2016) and noted that some healthcare providers made assumptions that all women had safe and stable housing (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Phillimore, 2016). Access to financial resources (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Jayaweera et al., 2005; Phillimore, 2016), employer or childcare support for appointments or labour (Phillimore, 2016) were concerns which they felt unable to discuss with their midwife (Alshawish et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Phillimore, 2016).

Women noticed the impact of short staffing and high workloads on the delivery of care, such that interactions with midwives in the antenatal and postnatal periods were described as ‘rushed’ (Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; Phillimore, 2016; Puttusery et al., 2010) or overly focused on measurement activities (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; Puttusery et al., 2010).

Staff were often too busy to come when called and when they did eventually come they were annoyed! (Indian Mother, UK born, Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013).

This context impacted negatively as ethnic minority women reported not feeling in control or participating in decision‐making. As a result, they experienced birthing as impersonal and dissatisfying:

I would have my appointments made for me and each time I went they would check or take what they wanted, and then I would leave without understanding what they had done… I saw no special kindness. They would just do the job and go (Somali mother, Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002).

It was the midwife …. She did not want to know. She had a set of things she wanted me to do and she did not want me to ask any questions. It did not matter that I speak English (South Asian mother, Davies & Bath, 2001).

This experience was exacerbated by lack of continuity of care which made building a trusting relationship difficult (Beake et al., 2013; Goodwin et al., 2017; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; Phillimore, 2016; Puttusery et al., 2010) and impacted negatively on the quality of communication (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; McAree et al., 2010; Puttusery et al., 2010) and women's confidence to attend follow‐ups (Phillimore, 2016). In one study (McCourt & Pearce, 2000), women reported multiple shift changes of staff attending the birth and several non‐essential staff or students present without the woman understanding why they were there or giving her consent, which reinforced the perception of care as technocratic.

6. COMMUNICATION FAILURES

Several communication failures were described by women as a consequence of knowledge assumptions by midwives and their avoidance of time consuming or potentially complex engagements. Navigating the UK maternity system was described as especially hard if different specialists were involved in care (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Goodwin et al., 2017; Moxey & Jones, 2016; Phillimore, 2016) or women were not confident in English (Ali, 2004; Alshawish et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Lam et al., 2012). Women felt midwives assumed they knew how to find antenatal classes (Ali, 2004, Birthrights, 2020, Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019, Moxey & Jones, 2016), and reliable information to prepare for parenthood (Ali, 2004; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Lam et al., 2012; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Moxey & Jones, 2016; Phillimore, 2016; Watson & Soltani, 2019). They felt health professionals did not have time to signpost key information (Ali, 2004; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Wittkowski et al., 2011) and that they were left to ‘fend for themselves’ (Ali, 2004; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019).

…they gave lots of paperwork which, to be honest, I do not even think I've read of it to this day. (Ethnic minority Mother, ethnicity not specified, Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019).

Some had been unaware of the available birth choices (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; McAree et al., 2010) about pain relief (McAree et al., 2010) or where to go for help if they had concerns (Ali, 2004, Alshawish, 2013; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019, Davies & Bath, 2001, Goodwin et al., 2017, Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013, Phillimore, 2016, Puttusery et al., 2010, Watson & Soltani, 2019, Wittkowski et al., 2011). Some women said that they did not know how to write a birth plan and felt their midwife had not checked if they needed support (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Hassan et al., 2019; Puttusery et al., 2010). However, when midwives did share information, it was well received and gave women the chance to voice their concerns (Watson & Soltani, 2019).

Women who were not confident in English often reported language barriers and interpretation challenges when trying to communicate with maternity staff (Ali, 2004; Alshawish et al., 2013; Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Jayaweera et al., 2005; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; Lam et al., 2012; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Moxey & Jones, 2016; Phillimore, 2016; Puttusery et al., 2010; Watson & Soltani, 2019). Concerns about consent were highlighted. In some cases, women had undergone procedures without fully understanding their purpose or risks (Ali, 2004; Alshawish et al., 2013; Beake et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McAree et al., 2010).

I do not know what's going to happen so and I did not know when they do a sweep I did not know what that was. (Ethnic minority Mother, ethnicity not specified, Beake et al., 2013).

Health‐trained interpreters were rarely used, resulting in reliance on friends and families (Ali, 2004; Alshawish et al., 2013; Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Phillimore, 2016), which caused discomfort and prevented full disclosure of symptoms (Ali, 2004; Alshawish et al., 2013; Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Moxey & Jones, 2016), asking of questions (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McCourt & Pearce, 2000) or attendance at appointments (Birthrights, 2020; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Jayaweera et al., 2005; Phillimore, 2016). Women were not always aware of their right to a trained interpreter (Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Birthrights, 2020; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011). If an interpreter was present, women worried about the accuracy of translation and confidentiality (Ali, 2004; Davies & Bath, 2001; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Phillimore, 2016). Some women felt they were made responsible for finding or booking an interpreter (Ali, 2004, Alshawish, 2013, Birthrights, 2020, Davies & Bath, 2001, Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002). In one study, women found the available translated information sheets unintelligible (Phillimore, 2016).

7. MISTREATMENT OF WOMEN

Differential treatment by staff impacted the quality of care women received (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Goodwin et al., 2017; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; McFadden et al., 2018; Ockleford et al., 2004; Wittkowski et al., 2011). Some women reported prejudice or discrimination based on their ethnicity, religion or culture (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Davies & Bath, 2001; Goodwin et al., 2017) and being treated in an unsympathetic or unhelpful way, especially compared with the ways White mothers were seen to be treated (Ali, 2004, Beake et al., 2013, Birthrights, 2020, Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019, Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011, Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013, McCourt & Pearce, 2000, McFadden et al., 2018,Wittkowski et al., 2011).

I was on a ward of four white women and I asked her, ‘You were really good with the person next door, could you help me. I asked two or three times I wanted to breastfeed and they did not come to me, yet they helped all the white women. (Muslim Mother, ethnicity not specified, Ali, 2004).

Direct discrimination, stereotyping or racist comments (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Goodwin et al., 2017; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Hassan et al., 2019; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McCourt & Pearce, 2000) were noted, including the suggestion that Asian women made a fuss and were unable to tolerate pain (McCourt & Pearce, 2000), and that Bangladeshi women had children to get more state benefits (Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Wittkowski et al., 2011). Two studies reported that women felt coerced to have intra‐uterine devices fitted immediately after birth to control their fertility (Ali, 2004; McCourt & Pearce, 2000).

These experiences and a lack of support in hospital (Ali, 2004; Beake et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; Puttusery et al., 2010; Watson & Soltani, 2019) led women to feel isolated, abandoned (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; McFadden et al., 2018; Moxey & Jones, 2016; Ockleford et al., 2004; Puttusery et al., 2010; Wittkowski et al., 2011) and lonely (Birthrights, 2020; Davies & Bath, 2001). They felt afraid to ask questions or voice their concerns (Birthrights, 2020; Phillimore, 2016).

The fact you are asking for help, sometimes you are labelled, fear of, that you cannot cope…. You'll be judged. You're feeling like you cannot look after your baby. (Mother, ethnicity not specified, Cardwell & Wainright 2019).

Women whose children had been removed for safeguarding reasons said that they received no support from midwives and wished for more openness, honesty and bereavement support (Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019):

To me it was all just about taking the baby you know, really. They never really asked, really, you know, me being sad… (Mother, ethnicity not specified, Cardwell & Wainright 2019).

If women did ask for help or support, they felt ignored or that their request was an imposition (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Davies & Bath, 2001; Hassan et al., 2019; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Puttusery et al., 2010; Watson & Soltani, 2019; Wittkowski et al., 2011). This was worse if there was a language barrier and made women feel frightened (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McAree et al., 2010; Phillimore, 2016). Even women who spoke English fluently recalled dismissive and disrespectful attitudes of maternity care staff, which discouraged them from speaking up (Ali, 2004; Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Davies & Bath, 2001; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Puttusery et al., 2010). Three papers reported women being denied adequate pain relief during labour despite asking for more (Birthrights, 2020; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McCourt & Pearce, 2000). In addition to making women feel low or scared (Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Puttusery et al., 2010; Wittkowski et al., 2011), the uncaring behaviour by the staff made them cautious about engaging with the hospital maternity service in future pregnancies Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019, McCourt & Pearce, 2000, Puttusery et al., 2010).

I will not have a baby in a hospital again… It's not worth going to hospital because the experience I had was just terrible (African first‐time mother, Puttusery et al., 2010).

One group of women who had experienced genital cutting (Gillespie, 2012) described how a lack of understanding of the practice among attending staff had negatively impacted their birth experience (Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002). Another study described Muslim women being ‘told off’ for fasting during Ramadan, being interrogated for refusing fetal screening, and not being informed that the vitamin K injection given to newborns contains porcine ingredients (Hassan et al., 2019). These findings are included for completeness but are reported with low confidence due to the single paper containing this evidence, which reports from a sample of seven women with no reflexivity and poor reporting of the method. Requests for female birth attendants by Muslim women and their partners were not always accommodated, causing them to feel guilty, and prompting decisions to birth at home or change healthcare providers (Ali, 2004; Alshawish et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Hassan et al., 2019; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013).

In two papers, women reported that staff audibly discussed sensitive personal information about them standing just behind a curtain in an open ward (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019). Privacy was also an issue: women felt disrespected when staff would keep opening their bed curtains which they had closed to breastfeed or pray (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Hassan et al., 2019).

8. WOMAN‐CENTRED CARE AS EXCEPTIONAL, NOT ROUTINE

Despite the emphasis on task‐focused care in a technocratic system and evidence of mistreatment of women, the synthesis also provided some examples of positive experiences of care. Sadly, these were often the exception and were confined to specific continuity of care services. Woman‐centred care was not the norm, nor was it reflected in the experiences of the majority of women in this synthesis. Where such care was delivered, it resulted in positive experiences (Beake et al., 2013, Birthrights, 2020, Cardwell & Wainwright 2019, Goodwin et al., 2017, McAree et al., 2010, McCourt & Pearce, 2000, McFadden et al., 2018, Moxey & Jones, 2016, Watson & Soltani, 2019) and fostered a sense of control (McCourt & Pearce, 2000), irrespective of whether the midwife and the woman shared ethnic or racial identity (Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Puttusery et al., 2010). Trusting relationships with maternity staff made women feel safe, and reassured (McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; McFadden et al., 2018) and improved access to information for the woman and her family (Birthrights, 2020; Goodwin et al., 2017; McAree et al., 2010; Watson & Soltani, 2019).

So I used to get along with her so good I used to talk to her about everything that I did not even speak to my husband or mum about …. You know when you get to know someone, it's easier to talk and stuff (Ethnic minority mother, ethnicity not specified, Beake et al., 2013).

Such relationships gave women confidence to ask questions and share decision‐making (Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Moxey & Jones, 2016).

My voice was heard, you know, they took my issues to heart. (Mother involved with social services, ethnicity not specified, Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019).

These relationships also facilitated self‐efficacy (Birthrights, 2020; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McCourt & Pearce, 2000). Trust was built more easily when the woman had the same midwife looking after her throughout pregnancy and labour (Beake et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; McFadden et al., 2018; Moxey & Jones, 2016) who knew her and her family and did not require a fresh set of explanations on every visit (Beake et al., 2013; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; McFadden et al., 2018). Women felt that continuity made communication easier (Beake et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; McAree et al., 2010; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Watson & Soltani, 2019), made them feel cared for (Beake et al., 2013; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McFadden et al., 2018), not judged (Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Puttusery et al., 2010), well supported (Beake et al., 2013; Binder‐Finnema et al., 2012; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; Jomeen & Redshaw, 2013; McFadden et al., 2018), and listened to (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011; Harper Bulman & McCourt, 2002; McCourt & Pearce, 2000; Watson & Soltani, 2019). Women appreciated when midwives were sensitive to their cultural and religious beliefs (Ali, 2004; Moxey & Jones, 2016) and Muslim parents valued the information given in classes on how to fulfil religious observance during pregnancy and birth (Ali, 2004).

Some papers described targeted services that offered additional support to ethnic minority women (Ali, 2004; Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Jayaweera et al., 2005; McAree et al., 2010), but referral to these charities and mental health services appeared highly dependent on local knowledge of the midwife (Birthrights, 2020; Cardwell & Wainwright, 2019; Cross‐Sudworth et al., 2011).

9. DISCUSSION

9.1. Main findings

Our synthesis of 24 qualitative studies highlights how the technocratic birthing system and discriminatory practices in the UK NHS maternity services fail ethnic minority women. In the context of chronic understaffing and heavy workloads, there is a focus on measurements and procedures rather than the provision of a kind, holistic women‐centred care. Ethnic minority women are being left in the dark about what to expect, their rights and their choices, during pregnancy, birth and postnatally. Particular communication failures, due to a woman's limited English or cultural customs unfamiliar to maternity staff, may be symptoms of an overstretched workforce or manifestations of a deeper and generalized tendency to undermine and silence ethnic minority women in maternity care. Evidence of more direct forms of discrimination based on race and religion (and their intersections with economic and social disadvantages) suggest a perverse inversion, whereby women in need of the greatest support are likely to receive the least. Woman‐centred continuity of care models resulted in positive experiences, but this was often only found in pockets with the personnel and mandate rather than being a norm across service provision.

9.2. Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to synthesize the qualitative literature from the UK exploring ethnic minority women's experiences of maternity services and we have used rigorous methods (Atkins et al., 2008; CASP, 2019; Karnieli‐Miller et al., 2009) for synthesizing and assessing the quality of the studies included.

Evidence synthesis works with secondary data and is limited by the original research questions of the papers, the quality of their methods and the presentation of their findings. Our search methods returned charity research reports and policy‐oriented papers, publication of doctoral research with local communities, alongside academic papers from research institutions. This variety meant that there was variation in rigour and reporting of methods, and sometimes a failure to consider power in the researcher–participant relationship. Notwithstanding these differences, our involved inductive approach has an added value by integrating these different sources to reveal new themes of interest.

9.3. Interpretation (findings in light of other evidence)

This synthesis augments the MBRRACE (Knight et al., 2020) analysis to illustrate how systemic biases, perpetuated by staff without skills and knowledge to understand the needs or listen to the concerns of ethnic minority women can prevent those women most at risk from receiving the care they need (Esegbona‐Adeigbe, 2021). Over 90% of the 566 deaths in the MBRRACE analysis were of women with a combination of risk factors that were also mentioned in this synthesis, reinforcing that ethnic minority women are at risk of poorer care and mistreatment. Core concepts identified as necessary for a positive birth experience among all birthing women include respectful care, trusting relationships, control and participation in decision‐making (Downe et al., 2018; Karlsdottir et al., 2018; Renfrew et al., 2014). These concepts were also highlighted as necessary for the ethnic minority women who participated in the studies included in our synthesis. However, they are entering the system already facing enormous disadvantages due to structural racism in society, and then there is further damage by more direct forms of racism in maternity care, both of which are not faced by white majority women.

Complaints of a dissatisfying birth experience in this underfunded, overstretched technocratic birthing system are shared by the white majority (Davis‐Floyd, 2003; Reed et al., 2017; Scamell & Aleszewski, 2012; Walsh, 2010). The technocratic approach, where clinical tasks and the safety agenda are privileged over person‐centred care, has been linked with negative psychological and social consequences (Beck, 2011; Benoit et al., 2010; Forssen, 2012; Reed et al., 2017; Soet et al., 2003). This has stimulated the Continuity of Midwifery Carer (CMC) policy linked to the Better Births maternity review (Department of Health, 2017) and aims to have at least 35% of birthing women receiving CMC by 2025 (NHSE, 2019). In light of the growing awareness of the greater impact of this system on ethnic minority women in the mortality and morbidity statistics reported by MBRRACE, CMC models have since been targeted to women of Black, Asian and minority ethnic backgrounds with the realization that they could deliver significant improvements in care experiences (NHSE, 2019). The papers reviewed for this synthesis were before this service change.

However, this is predicated on work to recruit and retain midwives, which is an ongoing concern (Hall, 2021), to reduce the staffing pressures known to engender a routinized, technocratic model of practice (Kirkup, 2021). Writing about UK mental health services, Nazroo et al. (2020) consider how, to tolerate the circumstances created by resource constraints, commissioners and care providers may feel the need to distance themselves from those receiving care. This is much easier when providing care to particular groups that can be treated as ‘other’ (such as racialized groups). This ‘othering’ creates and sustains inequalities, such that unequal health outcomes are understood simply as a reflection of wider structural conditions, in the context of resource constraints, and easily accepted as the norm.

Many women represented in the papers included in this synthesis reported instances of bullying, discrimination, unconsented procedures, coercive or insensitive care. Sometimes this was through omission or lack of consideration, but at others was direct. The recently proposed National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) guideline recommending that Black, Asian and ethnic minority women be offered clinical induction at 39 weeks, acknowledges the excess risks for ethnic minority women but fails to articulate where the risk lies. Given mounting evidence from the UK of racism in healthcare, and in maternity care, in particular, this silence is significant and reinforces the false medical narrative that pathologizes ethnic minority bodies as deficient or inferior. In 2020, The American Medical Association explicitly recognized racism as a threat to public health and, in 2021, adopted new guidelines to confront systemic racism in medicine (American Medical Association [AMA], 2021). A similar move is urgently needed in the UK.

The experiences reported in this synthesis, alongside the disparities highlighted in the MBRRACE report (Knight et al., 2020), add context to the legal charity ‘Birthrights’ national inquiry into disparities in maternity care experiences and the impact of systemic racism (Birthrights, 2021). While acknowledging, this may not be the experience of all ethnic minority women, this synthesis uncovers the presence of racism in UK maternity services. It documents the impact that this has on the experience and well‐being of birthing women from ethnic minorities and is thus a necessary core consideration in a woman‐centred care agenda (Trepagnier, 2017).

10. CONCLUSION

This synthesis shows that ethnic minority women report positive pregnancy and birth experiences when they are in receipt of kind, respectful and woman‐centred midwifery care. However, these experiences are often the exception in the overstretched technocratic birthing system of the UK. The integration of these 24 studies reveals varied and disturbing forms of mistreatment and poor care for ethnic minority women in the UK and it seems probably that these differences in experience are linked to the inequalities in outcomes identified in the MBRRACE report. There is clearly much to be done in education and practice to address these concerns and improve these women's experience of the birthing journey.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or personal interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jennifer MacLellan conceived the study. Jennifer MacLellan and Sarah Collins designed and performed the search, study screening, data extraction and preliminary data analysis in duplicate. Tanvi Rai was the arbiter for unresolved conflicts. Jennifer MacLellan, Sarah Collins, Margaret Myatt, Wanja Knighton and Tanvi Rai refined the analysis. Jennifer MacLellan, Sarah Collins and Tanvi Rai wrote the manuscript with revisions based on Catherine Pope Wanja Knighton and Margaret Myatt comments. All authors accept responsibility for the manuscript.

DETAILS OF ETHICS APPROVAL

Ethics approval was not required for secondary use of data in this systematic evidence synthesis. This manuscript is an honest, accurate and transparent account of the study being reported that no important aspects of the study have been omitted and that any discrepancies from the study as planned have been explained. Data extracted from included studies and data used for all analyses are available from the corresponding author on request.

OPEN RESEARCH BADGES

This article has a preregistered research design available at https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020225758

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15233.

Supporting information

DataS 1

FigureS 1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to acknowledge Nia Roberts (librarian, Bodleian Health Care Libraries, University of Oxford) for her guidance in developing the search strategy.

MacLellan, J. , Collins, S. , Myatt, M. , Pope, C. , Knighton, W. & Rai, T. (2022). Black, Asian and minority ethnic women's experiences of maternity services in the UK: A qualitative evidence synthesis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 2175–2190. 10.1111/jan.15233

Funding information

We thank the Burdett Trust for Nursing for funding researcher time (JM and TR) to complete this synthesis (grant ref: SB\ZA\101010662\633464).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Ali, N. (2004). Experiences of maternity services: Muslim Women's perspectives. The Maternity Alliance. https://www.maternityaction.org.uk/wp [Google Scholar]

- Alshawish, E. , Marsden, J. , Yeowell, G. , & Wibberley, C. (2013). Investigating access to and use of maternity health‐care services in the UK by Palestinian women. British Journal of Midwifery, 21, 571–577. [Google Scholar]

- American Medical Association (AMA) AMA adopts guidelines that confront systemic racism in medicine. Press release. 2021. https://www.ama‐assn.org/press‐center/press‐releases/ama‐adopts‐guidelines‐confront‐systemic‐racism‐medicine [Google Scholar]

- Aquino, M. R. , Edge, D. , & Smith, D. M. (2015). Pregnancy as an ideal time for intervention to address the complex needs of black and minority ethnic women: Views of British midwives. Midwifery, 31, 373–379. 10.1016/j.midw.2014.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, S. , Lewin, S. , Smith, H. , Engel, M. , Fretheim, A. , & Volmink, J. (2008). Conducting a meta‐ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 21. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beake, S. , Acosta, L. , Cooke, P. , & McCourt, C. (2013). Caseload midwifery in a multi‐ethnic community: The woman's experiences. Midwifery, 29, 996–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C. T. (2011). A metaethnography of traumatic childbirth and its aftermath: Amplified causal looping. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 301–311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, C. , Zadoroznyj, M. , Hallgrimsdottir, H. , Treloar, A. , & Taylor, K. (2010). Medical dominance and neoliberalisation in maternal care provision: The evidence from Canada and Australia (pp. 475–481). Social Science and Medicine. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder‐Finnema, P. , Borne, Y. , Johnsdotter, S. , & Essen, B. (2012). Shared language is essential: Communication in a multiethnicity obstetric care setting. Journal of Health Communication, 2012, 1171–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birthrights . (2020). Holding it all together: Understanding how far the human rights of women facing disadvantage are respected during pregnancy, birth, postnatal care. Birthrights. https://www.birthrights.org.uk/wp‐content/uploads/2019/09/Holding‐it‐all‐together‐Full‐report‐FINAL‐Action‐Plan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Birthrights (2021) Racial injustice in maternity care. A human rights inquiry: Call for evidence Birthrights. https://www.birthrights.org.uk/campaigns‐research/racial‐injustice/ [Google Scholar]

- Cardwell, V. , & Wainwright, L. (2019). Making better births a reality for women with multiple disadvantages. A qualitative peer research study exploring perinatal women's experiences of care and services in north—East London. Birth Companions and Revolving Doors Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme CASP CHECKLISTS ‐ CASP ‐ Critical appraisal skills programme. 2019. casp‐uk.net [Google Scholar]

- Cross‐Sudworth, F. , Williams, A. , & Herron‐Marx, S. (2011). Maternity services in multi‐cultural Britain: Using Q methodology to explore the views of first‐ and second ‐ generation women of Pakistani origin. Midwifery, 27, 458–468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, M. M. , & Bath, P. A. (2001). The maternity information concerns of Somali women in the United Kingdom. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(2), 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, D. (2019). Obstetric racism: The racial politics of pregnancy, labor, and birthing. Medical Anthropology, 38, 560–573. 10.1080/01459740.2018.1549389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis‐Floyd, R. E. (2003). Birth as an American rite of passage. University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (1993). Changing childbirth: Reports of the expert maternity group parts 1 & 2. Stationary Office. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (1997). The new NHS: Modern and dependable. HMSO; Stationary Office. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2017). Better births: Improving outcomes of maternity services in England – A five year forward view for maternity care. Stationary Office. [Google Scholar]

- Downe, S. , Lawrie, T. A. , Finlayson, K. , & Oladapo, O. (2018). Effectiveness of respectful care policies for women using routine intrapartum services: A systematic review. Reproductive Health, 15, 1. 10.1186/s12978-018-0466-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esegbona‐Adeigbe, S. (2021). The impact of a Eurocentric curriculum on racial disparities in maternal health. European Journal of Midwifery, 5, 36. 10.18332/ejm/140086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finigan, V. , & Long, T. (2014). Skin‐to‐skin contact: Multicultural perspectives on birth fluids and birth ‘dirt’. International Nursing Review, 61, 270–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, R. , & Fraser, C. (2020). Who gets in? What does the 2020 GP patient survey tell us about access to general practice? The Health Foundation. https://www.health.org.uk/news‐and‐comment/charts‐and‐infographics/who‐gets‐in [Google Scholar]

- Forssen, A. S. K. (2012). Lifelong significance of disempowering experiences in prenatal and maternity care: Interviews with elderly Swedish women. Qualitative Health Research, 22, 1535–1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie G. Why do we use the term female genital cutting and not female genital mutilation. The Orchid Project. 2012. https://www.orchidproject.org/why‐do‐we‐use‐the‐term‐female‐genital‐cutting‐and‐not‐female‐genital‐mutilation/ [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, L. , Hunter, B. , & Jones, A. (2017). The midwife‐woman relationship in a South Wales community: Experiences of midwives and migrant Pakistani women in early pregnancy. Health Expectations, 21, 347–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J. (2021). Midwifery staff shortages – Have we reached tipping point?. Maternity and Midwifery Forum Blog. https://www.maternityandmidwifery.co.uk/midwifery‐staff‐shortages‐have‐we‐reached‐tipping‐point/ [Google Scholar]

- Harper Bulman, K. , & McCourt, C. (2002). Somali refugee women's experiences of maternity care in West London: A case study. Critical Public Health, 12, 365–380. 10.1080/0958159021000029568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, S. M. , Leavey, C. , & Rooney, J. S. (2019). Exploring English speaking Muslim women's first‐time maternity experiences: A qualitative longitudinal interview study. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth, 19, 156. 10.1186/s12884-019-2302-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, J. , Gao, H. , & Redshaw, M. (2018). Experiencing maternity care: The care received and perceptions of women from different ethnic groups. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 2013, 196. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471‐2393/13/196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman, K. M. , Trawalter, S. , Axt, J. R. , & Oliver, M. N. (2016). Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 4296–4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jayaweera, H. , D'Souza, L. , & Garcia, J. (2005). A local study of childbearing Bangladeshi women in the UK. Midwifery, 21, 84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jomeen, J. , & Redshaw, M. (2013). Ethnic minority women's experience of maternity services in England. Ethnicity and Health, 18, 280–296. 10.1080/13557858.2012.730608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsdottir, S. L. , Sveinsdottir, H. , Kristjansdottir, H. , Aspelund, T. , & Olafsdottir, O. A. (2018). Predictors of women's positive childbirth pain experience: Findings from an Icelandic national study. Women and Birth, 31, e178–e184. 10.1016/j.wombi.2017.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karnieli‐Miller O, Strier R, Pessach L, (2009) Power relations in qualitative research Qualitative Health Research 2009;19:279‐89 10.1177/1049732308329306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkup, B. (2021). EPE0005 – Expert panel: Evaluation of the Government's commitments in the area of maternity services in England. Written Evidence Health and Social Care Committee. https://committees.parliament.uk/committee/81/health‐and‐social‐care‐committee/publications/written‐evidence/?SearchTerm=bill+kirkup [Google Scholar]

- Knight, M. , Bunch, K. , Tuffnell, D. , Shakespeare, J. , Kotnis, R. , Kenyon, S. , et al. (Eds.). (2020). MBRRACE‐UK: Saving lives, improving Mothers' Care 2020: Lessons to inform maternity care from the UKand Ireland confidential enquiries in maternal death and morbidity 2016–18. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Lam, E. , Wittkowski, A. , & Fox, J. R. E. (2012). A qualitative study of the postpartum experience of Chinese women living in England. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 30, 105–119. 10.1080/02646838.2011.649472 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons, S. M. , O'Keeffe, F. , Clarke, A. T. , & Staines, A. (2008). Cultural diversity in the Dublin maternity services: The experience of maternity service providers when caring for ethnic minority women. Ethnicity and Health, 13, 261–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLellan, J. , Collins, S. , Myatt, M. , Rai, T. , et al. (2020). A Metasynthesis of Black, Asian and minority ethnic women's experiences of maternity services in the UK (CRD42020225758 Available from:). PROSPERO. https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42020225758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAree, T. , McCourt, C. , & Beake, S. (2010). Perceptions of group practice midwifery from women living in an ethnically diverse setting. Evidence Based Midwifery, 8, 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- McCourt, C. , & Pearce, A. (2000). Does continuity of carer matter to women from minority ethnic groups? Midwifery, 16, 145–154. 10.1054/midw.2000.0204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, A. , Siebelt, L. , Jackson, C. , Jones, H. , Innes, N. , MacGillivray, S. , & Gypsy, E. (2018). Roma and Traveller peoples' trust: Report. University of Dundee. 10.20933/100001117 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Metzl, J. M. , & Hansen, H. (2014). Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Social Science and Medicine, 103, 126–133. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, S. A. (2001). PICO worksheet and search strategy. US National Center for Dental Hygiene Research. [Google Scholar]

- Moxey, J. M. , & Jones, L. L. (2016). A qualitative study exploring how Somali women exposed to female genital mutilation experience and perceive antenatal and intrapartum care in England. BMJ Open, 6, e009846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. , Windsor, C. , Parker, E. , & Tewfik, O. (2010). The experiences of African women giving birth in Brisbane, Australia. Health Care for Women International, 31, 458–472. 10.1080/07399330903548928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo, J. Y. , Bhui, K. S. , & Rhodes, T. (2020). Where next for understanding race/ethnic inequalities in severe mental illness? Structural, interpersonal and institutional racism. Sociology of Health and Illness, 42(2), 262–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NHSE . (2019). Targeted and enhanced midwifery‐led continuity of carer. NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/ltphimenu/maternity/targeted‐and‐enhanced‐midwifery‐led‐continuity‐of‐carer/ [Google Scholar]

- Ockleford, E. M. , Berryman, J. C. , & Hsu, R. (2004). Postnatal care: What new mothers say. British Journal of Midwifery, 12(3), 166–170. [Google Scholar]

- O'Mahony, J. , & Donnelly, T. (2010). Immigrant and refugee women's post‐partum depression help‐seeking experiences and access to care: A review and analysis of the literature. Journal of Psychiatry and Mental Health Nursing, 17, 917–928. 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01625.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J. , McKenzie, J. E. , Bossuyt, P. M. , Boutron, I. , Hoffmann, T. C. , Mulrow, C. D. , et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, n71. 10.1136/bmj.n71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillimore, J. (2016). Migrant maternity in an era of superdiversity: New migrants' access to, and experience of, antenatal care in the west midlands, UK. Social Science and Medicine, 148, 152–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttusery, S. , Twamley, K. , Harding, S. , Mirsky, J. , Baron, M. , & Macfarlane, A. (2008). ‘They're more like ordinary stroppy British women’: Attitudes and expectations of maternity care professionals to UK‐born ethnic minority women. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 13(4), 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puttusery, S. , Twamley, K. , Macfarlane, A. , Harding, S. , & Baron, M. (2010). ‘You need that tender loving care’: Maternity care experiences and expectations of ethnic minority women born in the United Kingdom. Journal of Health Services Research and Policy, 15(3), 156–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race Disparity Unit . Writing about ethnicity. 2021. https://www.ethnicity‐facts‐figures.service.gov.uk/style‐guide/writing‐about‐ethnicity

- Rayment‐Jones, H. , Harris, J. , Harden, A. , Khan, Z. , & Sandall, J. (2019). How do women with social risk factors experience United Kingdom maternity care? A realist synthesis. Birth: Issues in Perinatal Care, 46, 461–474. 10.1111/birt.12446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redshaw, M. , & Heikkila, K. (2011). Ethnic differences in women's worries about labour and birth. Ethnicity and Health, 16(3), 213–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed, R. , Sharman, R. , & Inglis, C. (2017). Women's descriptions of childbirth trauma relating to the care provider actions and interactions. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 17, 21. 10.1186/s12884-016-1197-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renfrew, M. J. , McFadden, A. , Bastos, M. H. , Campbell, J. , Channon, A. A. , Cheung, N. F. , Silva, D. R. A. D. , Downe, S. , Kennedy, H. P. , Malata, A. , McCormick, F. , Wick, L. , & Declercq, E. (2014). Midwifery and quality care: Findings from a new evidence‐informed framework for maternal and newborn care. The Lancet, 384(9948), 1129–1145. 10.1016/s0140-67369(14)607893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rethlefsen, M. L. , Kirtley, S. , Waffenschmidt, S. , Ayala, A. P. , Moher, D. , et al. (2021). PRISMA‐S group. PRISMA‐S: An extension to the PRISMA statement for reporting literature searches in systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 10(1), 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scamell, M. , & Aleszewski, A. (2012). Fateful moments and the categorisation of risk: Midwifery practice and the ever narrowing window of normality during childbirth. Health, Risk and Society, 14(2), 207–221. 10.1080/13698575.2012.661041 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soet, J. E. , Brack, G. A. , & Dilorio, C. (2003). Prevalence and predictors of women's experiences of psychological trauma during childbirth. Birth, 30(1), 36–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J. , & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8, 45. 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trepagnier, B. (2017). Silent racism: How well‐meaning white people perpetuate the racial divide. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, D. (2010). Childbirth embodiment: Problematic aspects of current understandings. Sociology of Health and Illness, 32(3), 486–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson, H. , & Soltani, H. (2019). Perinatal mental ill health: The experiences of women from ethnic minority groups. British Journal of Midwifery., 27(10), 642–648. [Google Scholar]

- Wikberg, A. , Eriksson, K. , & Bondas, T. (2012). Intercultural caring from the perspectives of immigrant new mothers. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic & Neonatal Nursing, 41, 5–649. 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2012.01395.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittkowski, A. , Zumla, A. , Glendenning, S. , & Fox, J. R. E. (2011). The experience of postnatal depression in south Asian mothers living in Great Britain: A qualitative study. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 29(5), 480–492. 10.1080/02646838.2011.639014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

DataS 1

FigureS 1

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.