Abstract

Aim

To investigate the effects of mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidants (mitoAOXs) on glycaemic control, cardiovascular health, and oxidative stress outcomes in humans.

Materials and Methods

Randomized controlled trials investigating mitoAOX interventions in humans were searched for in databases (MEDLINE‐PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE and Cochrane Library) and clinical trial registries up to 10 June 2021. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias and Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations were used to assess trial quality and evidence certainty, respectively.

Results

Nineteen studies (n = 884 participants) using mitoAOXs (including Elamipretide, MitoQ and MitoTEMPO) were included in the systematic review. There were limited studies investigating the effects of mitoAOXs on glycaemic control; and outcomes and population groups in studies focusing on cardiovascular health were diverse. MitoAOXs significantly improved brachial flow‐mediated dilation (n = 3 trials; standardized mean difference: 1.19, 95% CI: 0.28, 2.16; I2: 67%) with very low evidence certainty. No significant effects were found for any other glycaemic, cardiovascular or oxidative stress‐related outcomes with mitoAOXs in quantitative analyses, with evidence certainty rated mostly as low. There was a lack of serious treatment‐emergent adverse events with mitoAOXs, although subcutaneous injection of Elamipretide increased mild–moderate injection site‐related events.

Conclusion

While short‐term studies indicate that mitoAOXs are generally well tolerated, there is currently limited evidence to support the use of mitoAOXs in the management of glycaemic control and cardiovascular health. Review findings suggest that future research should focus on the effects of mitoAOXs on glycaemic control and endothelial function in target clinical population groups.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, glycaemic control, mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant, oxidative stress, reactive oxygen species

1. INTRODUCTION

Mitochondria are a major producer of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cells. Excess mitochondrial ROS has been implicated in the pathophysiology of various chronic diseases including Parkinson's disease, cardiovascular disease (CVD), type 2 diabetes, and cancer. 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 Antioxidant‐based therapies have been used to target and reduce overproduction of ROS, although their efficacy overall appears heterogeneous for improving chronic disease‐related outcomes. 5 , 6 , 7 Moreover, antioxidants used in most studies are general and not targeted to specific sites within cells. Thus, they probably target multiple sources and sites of cellular ROS production. Given that mitochondrial‐generated ROS have been pathologically implicated in many chronic diseases, 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 therapeutic approaches specifically targeting mitochondrial ROS may be effective and efficient for the management of ROS‐related chronic diseases. 8

Mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant (mitoAOX) therapies are designed specifically to allow an antioxidant agent to enter, accumulate and act within the mitochondria of cells. Among the various mitoAOX agents used in research studies are antioxidants with lipophilic cations attached (e.g. MitoQ, SKQ1, mito vitE and MitoTEMPO), liposome‐encapsulated antioxidants (e.g. MITO‐Porter–carried antioxidants), and peptide‐based antioxidants targeting mitochondria (e.g. Elamipretide [a.k.a. SS‐31 or MTP‐131] and XJB‐5‐131). 8

Growing evidence from preclinical studies has shown mitoAOXs to have beneficial effects on disease‐related outcomes, including in models of CVD, 9 , 10 neurological diseases 11 , 12 and impaired glucose metabolism. 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 There is also an increasing number of clinical trials that have been and/or are currently being conducted using specific mitoAOXs in patients with heart failure, 16 mitochondrial genetic diseases 17 and neurological diseases. 18 While preclinical studies suggest a potential benefit of mitoAOXs for patients with impaired glucose metabolism, there is currently a lack of studies investigating the effects of mitoAOXs on glycaemic control and glucose metabolism in humans.

Overall, there is a lack of systematic reviews specifically focusing on the effects of mitoAOXs on chronic disease‐related health outcomes. Thus, the aim of this systematic review was to undertake a systematic review to investigate the effects of mitoAOXs on glycaemic control, cardiovascular health, and oxidative stress in humans.

2. METHODS

This systematic review includes randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving human participants, and excludes non‐randomized trials and observational studies, trials that lack a placebo or control group, animal studies, and in vitro studies. Databases (MEDLINE‐PubMed, Scopus, EMBASE and Cochrane Library) were searched up to and including 10 June 2021. Clinical trial registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, ANZCTR, EU Clinical Trial Register and ISRCTN) were also searched for unpublished studies with available results. No restrictions were placed on age or language of publication. One published study 19 was later identified and added to the review. The search terms used are shown in Table S1 . The systematic review was prospectively registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42021253647).

The selection of studies was performed by two reviewers independently. First, potential studies were screened based on their titles and abstracts. The studies that were not ruled out in this procedure had their full texts evaluated. For all selected studies, the full text was sought, and their eligibility was double‐checked. Studies with abstracts only (i.e. conference proceedings) that were relevant and informative of outcomes and that could be linked to clinical trial registry information were also included. Any disagreement between the two reviewers regarding the eligibility and inclusion of studies was adjudicated by a third reviewer. Articles meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were included in the systematic review.

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing the risk of bias in randomized trials was used to assess the quality of trials under domains of allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of participants and researchers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) and selective reporting (reporting bias). Other biases were also evaluated based on the use of compliance‐related measures and consideration of potentially confounding factors of diet and physical activity.

Data were extracted by two reviewers independently. A third reviewer adjudicated when there was a lack of consensus between the two reviewers. The following data were obtained from the studies: authors, publication year, study design, number of participants, health characteristics, gender, mean age, mean body mass index, duration of treatment, duration of wash‐out (if a cross‐over study), dose/dosage regimen of treatment, placebo/control used, losses per arm, adverse events, outcome measure means and standard deviations (SDs), and data to inform Cochrane bias domain assessments.

The direction of study outcomes (based on statistical significance) in relation to glycaemic control, cardiovascular health and oxidative stress were summarized and tabulated for individual studies. Additionally, quantitative estimates of effect sizes were determined when at least two studies included relevant quantitative data for a specific efficacy‐related outcome using a random‐effects model with DerSimonian–Laird methods in Review Manager software (Cochrane RevMan 5.3). Standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used to represent the effect size for changes in the mitoAOX group versus control group. Heterogeneity across studies was determined for specific outcomes using the I2 statistic and chi‐squared test, with I2 more than 75% and/or chi‐square P less than .1 denoting statistically significant heterogeneity.

In quantitative analyses, within‐group post‐treatment minus pretreatment mean change was compared between mitoAOX and control groups for outcomes. For parallel design trials, mean changes provided were used or were calculated from pretreatment and post‐treatment data. SDs of prepost changes were also used if provided or were calculated assuming a correlation coefficient of .7 if not provided. 7 Cross‐over trials were regarded similarly to parallel trials, with separate mitoAOX and control arms considered. For studies that did not provide pretreatment outcome values where post‐treatment data were provided, only post‐treatment data were used. For studies that did not provide post‐treatment outcome values where pretreatment data were provided, pretreatment data were carried forward and assumed as post‐treatment data. In a subsequent sensitivity analysis, exclusion of the latter studies had no meaningful impact on statistical findings for any outcome.

Small study effects were planned to be assessed using funnel plots and the Egger regression test if at least 10 studies reported on an outcome of interest, including at least one medium‐size sample study. 20

Grading of evidence certainty was undertaken for outcomes with at least two studies reporting on them using GRADEpro GDT software (Evidence Prime, Inc, Hamilton, Canada), and involved assessing certainty of evidence based on concerns of study design, risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and other considerations, such as publication bias, effects size and potential confounding. 21 Evidence was graded down a level when (a) statistical findings were inconsistent across individual Cochrane Risk of Bias domains when considering only ‘low risk of bias’ studies; (b) when heterogeneity across studies was statistically significant (I2 > 75% and/or chi‐squared P < .1); (c) when the outcome was a surrogate rather than a patient‐important outcome; and (d) if the sample size was small (n < 200).

3. RESULTS

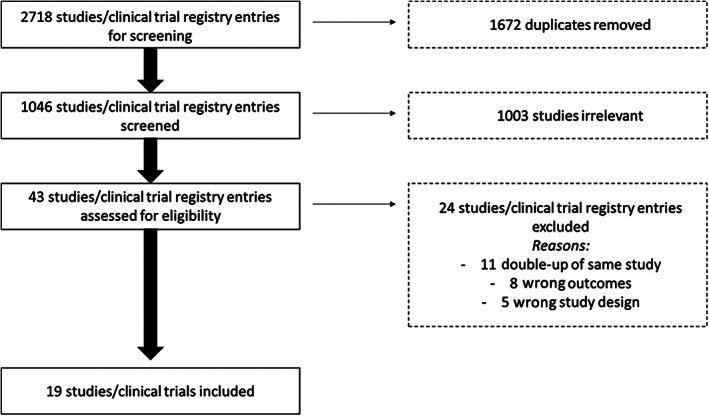

Nineteen studies (n = 884 participants) met the inclusion criteria and were included (Figure 1 and Table 1). The most common reasons for study exclusion were duplicate of the same study (same study/data published), wrong outcomes (study outcomes not relevant to the review), and wrong study design (non‐RCTs). Of the included studies, 16 were full‐text articles, 16 , 17 , 19 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 37 two were abstracts that were linked to clinical trial registry information, 22 , 29 and one was an unpublished study identified from a clinical trials registry. 36 Ten studies used Elamipretide as the mitoAOX agent, 16 , 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 26 , 27 , 32 , 34 , 36 eight studies used MitoQ, 19 , 25 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 37 and one study used MitoTEMPO. 28 Four studies included multiple mitoAOX treatment groups that used different mitoAOX doses. 16 , 17 , 23 , 25 For these studies, mitoAOX group data were combined into a single group for quantitative analyses, with collective means and SDs determined according to recommended methods. 38 Fourteen studies included participants with specific health conditions 16 , 17 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 32 , 34 , 36 and six studies included healthy participants. 19 , 28 , 31 , 33 , 35 , 37 Thirteen studies involved chronic mitoAOX supplementation ranging from five to 84 days, 16 , 17 , 19 , 22 , 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 35 , 36 , 37 while seven studies involved acute (<1 day) mitoAOX treatment. 23 , 24 , 26 , 28 , 30 , 34 , 37 Individual study findings are summarized in Table 2.

FIGURE 1.

Selection of studies for the systematic review

TABLE 1.

Studies included in the systematic review

| References | Year | Parallel or cross‐over | Control group | Duration (d) | Wash‐out (d) | Blinding | AOX agent | AOX form | AOX dose × frequency per day | Total n | n male/ female | Mean age (y) | Mean BMI (kg/m2) | Healthy or health condition? | Study quality a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broome et al. 19 | 2021 | Cross‐over | Placebo | 28 | 42 | Double | MitoQ | Tablets | 20 mg × once | 22 | 22/0 | 44 | 24.7 | Healthy | 5/7 |

| Butler et al. 16 | 2020 | Parallel | Placebo | 28 | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | S.C. injection | 4 mg or 40 mg × once | 71 | 54/17 | 64.8 | 28.4 | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction | 6/7 |

| Cleland et al. 22 | 2019 | Parallel | Placebo | Up to 7 | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | I.V. injection | 20 mg × once | 306 | 239/67 | 70.3 | N/A | Heart failure with an LVEF = 40% within 48 h of an admission for worsening peripheral oedema | 1/7 |

| Daubert et al. 23 | 2017 | Parallel | Placebo | 4 h | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | I.V. infusion | 0.005 or 0.05 or 0.25 mg/kg/h | 36 | 28/8 | 62 | 26 | Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (ejection fraction ≤ 35%) | 4/7 |

| Eirin et al. 24 | 2018 | Parallel | Placebo | 30 min pre‐ to 2.5 h post‐PTRA | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | I.V. infusion | 0.05 mg/kg/h | 14 | 7/7 | 67.7 | 30.5 | Renovascular hypertension patients undergoing PTRA | 0/7 |

| Gane et al. 25 | 2010 | Parallel | Placebo | 28 | N/A | Double | MitoQ | Tablets | 40 mg or 80 mg × once | 30 | 19/11 | 47.7 | 27.1 | Patients with document history of chronic HCV infection | 5/7 |

| Gibson et al. 26 | 2016 | Parallel | Placebo | 15‐60 min pre‐PCI and for 1 h following reperfusion | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | I.V. injection | 0.05 mg/kg/h | 118 | 85/33 | 60.1 | N/A | First‐time anterior STEMI subjects undergoing primary PCI for a proximal or mid left anterior descending artery occlusion | 2/7 |

| Karaa et al. 27 | 2020 | Cross‐over | Placebo | 28 | 28 | Double | Elamipretide | S.C. injection | 40 mg × once | 30 | 5/25 | 45.3 | 24.1 | Genetically confirmed primary mitochondrial myopathy | 5/7 |

| Karaa et al. 17 | 2018 | Parallel | Placebo | 2 h per day for 5 consecutive days | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | I.V. infusion | 0.01 or 0.1 or 0.25 mg/kg/h | 36 | 6/30 | 43 | 23 | Genetically confirmed primary mitochondrial myopathy | 5/7 |

| Kirkman et al. 28 | 2018 | Cross‐over | Placebo | Acute infusion | N/A | Unclear | MitoTempo | I.V. infusion | 1 mM | 11 | 6/5 | 58 | 24 | Healthy | 2/7 |

| 20 | 14/6 | 60 | 31 | CKD | |||||||||||

| Kirkman et al. 29 | 2020 | Parallel | Placebo | 28 | N/A | Double | MitoQ | Capsules | 20 mg × once | 18 | n.s. | 62 | N/A | Stage 3‐5 CKD | 2/7 b |

| Park et al. 30 | 2020 | Cross‐over | Placebo | Acute ingestion | 14 | Double | MitoQ | Capsules | 80 mg × once | 11 | 5/6 | 66.1 | 30 | Peripheral artery disease | 3/7 |

| Pham et al. 31 | 2020 | Cross‐over | Co‐enzyme Q | 42 | 42 | Double | MitoQ | Capsules | 20 × mg × once | 20 | 20/0 | 50.8 | 26.6 | Healthy | 5/7 |

| Reid Thompson et al. 32 | 2021 | Cross‐over | Placebo | 84 | 28 | Double | Elamipretide | S.C. injection | 40 mg × once | 12 | 12/0 | 19.5 | 17.6 | Genetically confirmed Barth syndrome | 5/7 |

| Rossman et al. 33 | 2018 | Cross‐over | Placebo | 42 | 0 | Double | MitoQ | Capsules | 20 mg × once | 24 | 9/11 | 68 | 23 | Healthy | 7/7 |

| Saad et al. 34 | 2017 | Parallel | Placebo | 30 min prior to PTRA until 3 h post | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | I.V. infusion | 0.05 mg/kg/h | 14 | 7/7 | 70.0 | 30.9 | Patients with severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis scheduled for PTRA | 4/7 |

| Shill et al. 35 | 2016 | Parallel | Placebo | 21 | N/A | Double | MitoQ | Capsules | 10 mg × once | 20 | 20/0 | 22.1 | 26.9 | Healthy | 4/7 |

| Stealth biotherapeutics Inc. 36 | 2021 | Parallel | Placebo | 28 | N/A | Double | Elamipretide | S.C. injection | 40 mg × once | 47 | 17/30 | 70.5 | N/A | Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction | 3/7 b |

| Williamson et al. 37 | 2020 | Parallel | Placebo | Acute ingestion 1 h pre‐exercise and 21 d | N/A | Double | MitoQ | Capsules | 20 mg × once | 24 | 24/0 | 25 | 26.6 | Healthy | 3/7 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CKD, chronic kidney disease; HCV, hepatitis C virus; I.V., intravenous; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; N/A, not applicable; n.s., not specified; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PTRA, percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty; S.C., subcutaneous; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction.

Study quality based on no. of Cochrane low risk‐of‐bias domains.

Study quality based only on abstract/clinical trial registry data.

TABLE 2.

Summary of direction of glycaemic control, cardiovascular health, and oxidative stress impacts in included studies (mitoAOX vs. control)

| MitoAOX agent | Health condition | Sample size (n) | Acute/ chronic (n days) | Dosage | Glycaemic control outcomes | Cardiovascular health‐related outcomes | Oxidative stress‐related outcomes | Reference | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | Cardiac measure | Marker of cardiac function | Endothelial/vascular function | Functional/patient‐important measure | Lipids | |||||||||

| Studies in patients with health conditions | Elamipretide | Heart failure | 71 | Chronic (28 d) | 4 mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | ↔ a , ↓ b | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | 16 |

| 40 mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | ||||||

| Heart failure | 306 | Chronic (7 d) | 20 mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | 22 | ||

| Heart failure | 36 | Acute | 0.005 mg/kg/h | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ c | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | 23 | ||

| 0.05 mg/kg/h | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ a , ↓ d | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ||||||

| 0.25 mg/kg/h | n/a | ↔ c | ↓ e | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ||||||

| Renovascular hypertension | 14 | Acute | 0.05 mg/kg/h | n/a | ↓ f | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 24 | ||

| STEMI | 118 | Acute | 0.05 mg/kg/h | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | 26 | ||

| Primary mitochondrial myopathies | 30 | Chronic (28 d) | 40 mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↓ g | n/a | ↔ c | 27 | ||

| Primary mitochondrial myopathies | 36 | Chronic (2 h/d for 5 d) | 0.01 mg/kg/h | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | 17 | ||

| 0.1 mg/kg/h | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | ||||||

| 0.25 mg/kg/h | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↑ h | n/a | ↔ c | ||||||

| Barth syndrome | 12 | Chronic (84 d) | 40 mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ i | n/a | n/a | 32 | ||

| Severe atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis | 14 | Acute | 0.05 mg/kg/h | n/a | ↓ f | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 34 | ||

| Heart failure | 47 | Chronic (28 d) | 40 mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | 36 | ||

| MitoQ | Chronic HCV infection | 30 | Chronic (28 d) | 40 mg × once daily | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | 25 | |

| 80 mg × once daily | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | ||||||

| Stage 3‐5 CKD | 18 | Chronic (28 d) | 20 mg × once daily | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | ↑ j | n/a | n/a | n/a | 29 | ||

| Peripheral artery disease | 11 | Acute | 80 mg | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | ↑ k | ↑ l | n/a | ↔ a , ↑ m | 30 | ||

| MitoTEMPO | CKD | 20 | Acute | 1 mM | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↑ n | n/a | n/a | n/a | 28 | |

| Studies in healthy participants | MitoQ | ‐ | 22 | Chronic (28 d) | 20 mg × once daily | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ c | ↓ o | 19 |

| ‐ | 20 | Chronic (42 d) | 20 × mg × once daily | ↔ c | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | ↔ a , ↓ p | 31 | ||

| ‐ | 20 | Chronic (42 d) | 20 × mg × once daily | ↔ c | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | ↑ q | n/a | ↔ c | ↓ r | 33 | ||

| ‐ | 20 | Chronic (21 d) | 10 × mg × once daily | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | ↔ c | 35 | ||

| ‐ | 24 | Acute | 20 mg | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | 37 | ||

| ‐ | 24 | Chronic (21 d) | 20 × mg once daily | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ s | |||

| MitoTEMPO | ‐ | 11 | Acute | 1 mM | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | ↔ c | n/a | n/a | n/a | 28 | |

Note: ↔, no statistically significant change in measured outcomes; ↑, statistically significant increase in measured outcomes; ↓, statistically significant decrease in measured outcomes.

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; FMD, flow‐mediated dilation; HCV, hepatitis C virus; mitoAOX, mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant; n/a, not assessed; Neuro‐QoL, Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders; PMMSA, Primary Mitochondrial Myopathy Symptom Assessment; RCT, randomized controlled trial; ROS, reactive oxygen species; STEMI, ST‐elevation myocardial infarction.

No changes for most outcomes assessed, but with exceptions.

Left atrial volume.

No changes for all outcomes assessed.

Right systolic ventricle pressure.

Left ventricle end systolic volume and left ventricle end diastolic volume.

Systolic blood pressure change within mitoAOX group only.

PMMSA Total Fatigue score, PMMSA Fatigue During Activities score, patient global assessment and Neuro‐QoL Fatigue Short Form.

6‐min walk test distance, when using an adjusted statistical model.

No changes in part 1 of study (RCT), but improvements in numerous functional/patient‐important outcomes in part 2 of study (non‐controlled, open‐label trial).

Central pressure waveforms (forward) and brachial FMD.

Brachial FMD and popliteal FMD.

Maximal walking distance, maximum walking time and time to onset of claudication.

Plasma superoxide dismutase.

Plateau phase of cutaneous vascular conductance.

Plasma F2‐Isoprostanes.

Skeletal muscle H2O2 in Complex I and Complex II leak after addition of oligomycin (Leako state) within mitoAOX group only.

Brachial FMD, FMD associated with amelioration of mitochondrial ROS‐related suppression of endothelial function (assessed as the increase in FMD with acute, supratherapeutic MitoQ [160 mg] and carotid‐femoral pulse‐wave velocity in participants with elevated baseline carotid‐femoral pulse wave velocity levels.

Plasma LDL oxidation.

No changes in oxidative stress markers/antioxidants, although exercise‐induced nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage was decreased in lymphocytes and muscle following mitoAOX supplementation.

Individual study quality was based on the number of ‘low risk’ Cochrane Risk of Bias domains (out of seven in total; Table 2). No studies were deemed to have any ‘high risk’ bias domains.

Most outcomes combined for quantitative analyses showed a lack of significant statistical heterogeneity across studies, although significant heterogeneity was reported for left atrial volume, right ventricular systolic pressure, brachial flow‐mediated dilation and malondialdehyde (Table 3). GRADE evidence was largely of low evidence, certainty for outcomes (Table 3). There were insufficient studies included in the review to investigate small study effects.

TABLE 3.

Quantitative syntheses of outcomes (with at least two studies) for mitoAOX versus control

| Outcome | Studies (n) | Participants (n) | SMD | 95% CI | P value | I2 (P value) | GRADE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting glucose | 2 | 71 | 0.24 | −0.22, 0.71 | .31 | 0% (.59) | LOW a , b |

| Systolic brachial BP | 7 | 175 | −0.19 | −0.50, 0.13 | .24 | 0% (.78) | LOW a , b |

| Diastolic brachial BP | 4 | 115 | −0.23 | −0.59, 0.14 | .23 | 0% (.79) | LOW a , b |

| Systolic central BP | 2 | 40 | −0.32 | −0.95, 0.30 | .31 | 0% (.99) | LOW a , b |

| LVESV | 3 | 217 | 0.12 | −0.16, 0.40 | .39 | 0% (1.00) | LOW a , b |

| LVEDV | 3 | 217 | 0.05 | −0.23, 0.33 | .71 | 0% (.90) | LOW a , b |

| LVEF | 3 | 217 | −0.08 | −0.36, 0.20 | .57 | 0% (.66) | LOW a , b |

| Left atrial volume | 2 | 99 | −0.13 | −1.27, 1.01 | .82 | 74% (.05) | VERY LOW a , b , c , d |

| Left ventricle mass | 2 | 189 | 0.07 | −0.23, 0.36 | .66 | 0% (.75) | LOW a , b |

| RV fractional area change | 2 | 99 | −0.12 | −0.57, 0.33 | .60 | 0% (.74) | LOW a , b |

| RV systolic pressure | 2 | 91 | −0.63 | −2.97, 1.71 | .60 | 91% (.0006) | VERY LOW a , b , c , d |

| E/e’ | 2 | 118 | 0.01 | −0.36, 0.38 | .96 | 0% (.93) | LOW a , b |

| LVGLS | 3 | 138 | 0.16 | −0.28, 0.61 | .47 | 28% (.25) | LOW a , b |

| Heart rate | 3 | 88 | 0.06 | −0.40, 0.52 | .79 | 0% (.78) | LOW a , b |

| NT‐proBNP | 4 | 452 | 0.01 | −0.18, 0.19 | .96 | 0% (.91) | MODERATE a |

| hs‐CRP | 3 | 107 | 0.03 | −0.38, 0.43 | .90 | 0% (.77) | LOW a , b |

| Brachial FMD | 3 | 80 | 1.19 | 0.28, 2.16 | .01 | 67% (.05) | VERY LOW a , b , c , d |

| CFPWV | 2 | 62 | −0.02 | −0.52, 0.48 | .93 | 0% (.97) | LOW a , b |

| 6‐min walk test distance | 4 | 214 | 0.06 | −0.22, 0.34 | .69 | 0% (.75) | MODERATE a |

| Triglycerides | 2 | 71 | 0.23 | −0.24, 0.69 | .34 | 0% (.72) | LOW a , b |

| MDA | 3 | 81 | −0.53 | −1.43, 0.37 | .25 | 73% (.03) | VERY LOW a , b , c |

| F2‐Isoprostanes | 3 | 107 | −0.01 | −0.58, 0.51 | .98 | 45% (.16) | LOW a , b |

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; CFPWV, carotid‐to‐femoral pulse wave velocity; E/e′, ratio between early mitral inflow velocity and mitral annular early diastolic velocity; FMD, flow‐mediated dilation; hs‐CRP, high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein; LVEDV, left ventricle end diastolic volume; LVEF, left ventricle ejection fraction; LVESV, left ventricle end systolic volume; LVGLS, left ventricle global longitudinal strain; MDA, malondialdehyde; mitoAOX, mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant; NT‐proBNP, N‐terminal‐pro hormone BNP; RV, right ventricle; SMD, standardized mean difference.

Surrogate measure, not patient‐important outcome.

Less than 200 participants per arm.

I2>75% or chi square P < .1.

Inconsistent significance when considering risk of bias domains with low risk only across all domains.

3.1. Glycaemic control outcomes

Two studies reported quantitatively on glycaemic control‐related outcomes following mitoAOX supplementation, both in healthy males 19 , 31 (Table 2). In one study, 31 no effects of treatment were found for HbA1c, fasting glucose, fasting insulin, or Homeostatic Model Assessment of Insulin Resistance (HOMA‐IR) after 6 weeks of supplementation with 20 mg MitoQ per day. In another study, 19 pre, during and postmoderate‐intensity exercise plasma glucose concentrations were unaffected in trained male cyclists after 4 weeks of supplementation with 20 mg MitoQ per day. In quantitative analyses of glycaemic‐related outcomes that were reported in at least two studies, no effect was found for fasting glucose in response to MitoQ supplementation (Table 4 and Figure S1).

TABLE 4.

Documented adverse events and safety‐related outcomes in included studies

| Study | Treatment | mitoAOX group | Control group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broome et al. 19 | MitoQ | No unfavourable or AEs reported | No unfavourable or AEs reported |

| Butler et al. 16 | Elamipretide |

4 mg dose: n = 9 (41%) AEs, n = 5 (23%) TEAEs (n = 1 [4%] injection‐site reactions), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 serious TEAEs, n = 0 deaths, n = 1 (4.5%) discontinuation because of TEAEs 40 mg dose: n = 16 (64%) AEs, n = 7 (28%) TEAEs (n = 6 [24%] injection‐site reactions, n = 1 (4%) SAE, n = 1 (4%) serious TEAEs, n = 0 deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of TEAEs |

n = 10 (42%) AEs, n = 0 TEAEs, n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 serious TEAEs, n = 0 all deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of TEAEs Rates of any study drug‐related events similar across all groups |

| Cleland et al. 22 | Elamipretide |

Within 40 d of randomization, n = 10 patients were rehospitalized for heart failure or had a cardiovascular death. Mean length of hospitalization admission: 10 (8‐12) d eGFR change: +1 (‐5, 7) ml/min/1.73m2 |

Within 40 d of randomization, n = 16 patients were rehospitalized for heart failure or had a cardiovascular death. Mean length of hospitalization admission: 9 (8‐10) d Differences in outcomes not significantly different between groups |

| Daubert et al. 23 | Elamipretide |

0.005 mg/kg/h dose: n = 1 (12%) AEs, n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs 0.05 mg/kg/h dose: n = 2 (25%) AEs, n = 0 SAEs, n = 1 discontinuation because of AEs 0.25 mg/kg/h dose: n = 0 AEs, n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs |

n = 0 AEs, n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs Differences in outcomes not significantly different between groups |

| Eirin et al. 24 | Elamipretide | eGFR significantly increased (+5.83 ± 2.64 ml/min/1.73m2) | eGFR did not change significantly (+1.86 ± 3.63 ml/min/1.73m2) |

| Gane et al. 25 | MitoQ |

40 mg/d dose: n = 29 AEs (n = 10 gastrointestinal disorder ‐ mostly nausea, vomiting, n = 8 nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 1 discontinuation because of AEs ALT and AST decreased significantly versus placebo 80 mg/d dose: n = 21 AEs (n = 8 gastrointestinal disorder, n = 4 nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs. ALT decreased significantly versus placebo |

n = 19 AEs (n = 1 gastrointestinal disorder, n = 5 nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs Except for higher gastrointestinal disorder events with MitoQ, no significant differences in the incidence of AEs were observed between groups |

| Gibson et al. 26 | Elamipretide |

In primary cohort: n = 8 (13.8%) had CHF events <24 h post‐PCI, n = 7 (12.1%) had any of: death, new‐onset CHF or CHF rehospitalization at 30 d, n = 5 (8.6%) had any of: death, new‐onset CHF or CHF rehospitalization at 6 mo In safety cohort: n = 20 (13.3%) had serious TEAEs, n = 2 (1.3%) had new MI, n = 37 (24.7%) had CHF Rise in serum creatinine with Elamipretide (+1 μmol/L) significantly lower versus placebo (+3.7 μmol/L) |

In primary cohort: n = 15 (25%) had CHF events <24 h post PCI, n = 5 (8.3%) had any of: death, new‐onset CHF or CHF rehospitalization at 30 d, n = 3 (5%) had any of: death, new‐onset CHF or CHF rehospitalization at 6 mo In safety cohort: n = 14 (9.5%) had serious TEAEs, n = 6 (4.1%) had new MI, n = 41 (27%) had CHF Apart from creatinine, no significant difference in outcomes between groups |

| Karaa et al. 17 | Elamipretide | n = 62 (total) AEs (including n = 48 injection‐site AEs), n = 0 SAEs, n = 1 discontinuation because of AE | n = 18 (total) AEs (including n = 5 injection‐site AEs), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AE |

| Karaa et al. 27 | Elamipretide |

0.01 mg/kg/h dose: n = 7 (77.8%) AEs (n = 1 [11.1%] gastrointestinal disorder, n = 3 [33.3%] nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs 0.1 mg/kg/h dose: n = 7 (77.8%) AEs (n = 3 [33.3%] gastrointestinal disorder, n = 2 [22.2%] nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs 0.25 mg/kg/h dose: n = 5 (55.6%) AEs (n = 0 gastrointestinal disorder, n = 2 [22.2%] nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs |

n = 5 (55.6%) AEs (n = 2 [22.2%] gastrointestinal disorder, n = 2 [22.2%] nervous system disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs No effect of treatments on ECG or blood chemistry measures |

| Park et al. 30 | MitoQ | No unfavourable or AEs reported | No unfavourable or AEs reported |

| Pham et al. 31 | MitoQ | No unfavourable or AEs reported | No unfavourable or AEs reported |

| Reid Thompson et al. 32 | Elamipretide | n = 74 (total) TEAEs across 12/12 participants reported (n = 46 injection site‐related events in 12/12 participants, n = 1 [8.3%] gastrointestinal disorders, n = 3 [25%] nervous system disorders) | n = 47 (total) TEAES across 10/12 participants reported (n = 13 injection site‐related events in 8/12 participants, n = 4 [33.3%] gastrointestinal disorders, n = 5 [41.7%] nervous system disorders) |

| Rossman et al. 33 | MitoQ | n = 1 (total) TEAEs (n = 1 gastrointestinal disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs |

n = 3 (total) TEAEs (n = 3 gastrointestinal disorder), n = 0 SAEs, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs A further n = 3 (total) TEAEs (n = 3 gastrointestinal disorder) were reported following acute administration of 160 mg MitoQ, but unclear which group this occurred in |

| Saad et al. 34 | Elamipretide |

No unfavourable or AEs reported eGFR significantly increased (+5.8 ± 11.1 ml/min/1.73m2) |

No unfavourable or AEs reported eGFR did not significantly change (+2.6 ± 7.8 ml/min/1.73m2) |

| Shill et al. 35 | MitoQ | No AEs reported, including during exercise | No AEs reported, including during exercise |

| Stealth biotherapeutics Inc. 36 | Elamipretide | n = 14 (60.9%) AEs (n = 20 [total] injection site‐related events, n = 0 nervous system disorders), n = 0 SAEs, n = 12 (52.2%) TEAEs, n = 1 severe TEAE, n = 0 deaths, n = 0 discontinuation because of AEs | n = 7 (29.2%) AEs (n = 2 [total] injection site‐related events, n = 1 [4.17%] nervous system disorders), n = 1 (4.17%) SAEs (n = 1 acute MI causing death), n = 2 (8.3%) TEAEs, n = 0 severe TEAE, n = 1 deaths, n = 1 discontinuation because of AEs |

| Williamson et al. 37 | MitoQ | No unfavourable or AEs reported | No unfavourable or AEs reported |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CHF, congestive heart failure; ECG, echocardiogram; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; MI, myocardial infarction; mitoAOX, mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAE, serious adverse event; TEAE, treatment‐emergent adverse event.

3.2. Cardiovascular health outcomes

Cardiac measures such as left ventricle end systolic volume (LVESV), left ventricle end diastolic volume (LVEDV), and LV ejection fraction (LVEF) were unchanged after Elamipretide in some studies, although a dose‐related improvement in LVESV and LVEDV was reported in one study involving an acute infusion of Elamipretide in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction 23 (Table 2). Similarly, cardiac function markers such as left ventricular filling pressure (E/e’), left ventricular global longitudinal strain (LVGLS, a measure of systolic function), N‐terminal pro b‐type natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) and high‐sensitivity C‐reactive protein did not significantly change with mitoAOX treatments. Functional‐related outcomes were also largely unchanged with mitoAOX treatments, although an Elamipretide dose‐related improvement in 6‐minute walk test performance was reported in a study involving 5 days of Elamipretide infusions in patients with genetically confirmed primary mitochondrial myopathies when considering a corrected statistical model. 17

Patient‐important outcomes including quality of life outcomes on the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy questionnaire and Barth Syndrome Symptom Assessment (a scale reporting on symptoms in patients with Barth Syndrome), all‐cause mortality, CVD‐related mortality, incidence of new congestive heart failure, rehospitalization because of heart failure, and duration of hospitalization remained unchanged after Elamipretide treatment. 16 , 17 , 22 , 26 , 32 , 36 However, in one study Elamipretide supplementation (40 mg/d for 28 days) significantly improved the Primary Mitochondrial Myopathy Symptom Assessment (PMMSA) total fatigue score, PMMSA Fatigue During Activities score, Patient global assessment and Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders Fatigue Form in patients with primary mitochondrial myopathies. 27 In another study in patients with mitochondrial myopathies, Elamipretide supplementation (dosages of 0.02‐0.5 mg/kg for 5 days) had no effect on outcomes in a Daily Symptoms Questionnaire or modified newcastle mitochondrial disease adult scale (NMDAS) questionnaire (focusing on quality of life and symptoms in patients with mitochondrial diseases). 17

Elamipretide treatment improved systolic brachial blood pressure in two studies in patients with atherosclerosis‐related impaired renal blood flow. 24 , 34 Acute MitoQ supplementation (80 mg) improved brachial and popliteal flow‐mediated dilation (FMD), maximum walking time, maximum walking distance, and time to onset of claudication in patients with peripheral artery disease (PAD) in one study. 30 Chronic MitoQ supplementation (20 mg/d) improved brachial FMD in one study involving healthy older participants 33 ; and improved brachial FMD and central pressure waveforms in participants with chronic kidney disease 29 (Table 2). MitoTEMPO infusion significantly increased the plateau phase of cutaneous vascular conductance in chronic kidney disease patients to levels observed in healthy controls in one study 28 (Table 2).

Quantitative analyses conducted for cardiovascular health‐related outcomes reported in at least two studies found a statistically significant lowering effect of mitoAOX treatments on brachial FMD, but not on any other cardiovascular health‐related outcome (Table 3 and Figures S2‐S4).

3.3. Oxidative stress outcomes

Some studies using MitoQ found improvements in markers of oxidative stress (Table 2). One study in healthy older participants reported an association between the improvement in brachial FMD with MitoQ supplementation and the amelioration of mitochondrial ROS‐related suppression of endothelial function. 33 In that study, a 62% improvement in brachial FMD was elicited by a single dose of MitoQ (160 mg) given after the placebo phase, while only a 7% improvement was found with acute MitoQ supplementation after the chronic mitoQ phase (20 mg MitoQ/d). In the same study, plasma LDL oxidation significantly decreased after supplementation with 20 mg MitoQ per day for 6 weeks. Another study in healthy participants found a significant decrease in skeletal muscle H2O2 concentration in Complex I and complex II leak after addition of oligomycin (leako state) following supplementation with 20 mg MitoQ per day for 6 weeks 31 ; and healthy males showed a 20% decrease in postexercise plasma F2‐Isoprostanes following 28 days of supplementation with 20 mg MitoQ. 19 A significant increase in plasma superoxide dismutase levels was observed after acute supplementation with MitoQ (80 mg) in patients with PAD. 30 Another study in healthy young adults found no changes in oxidative stress markers/antioxidant levels following MitoQ supplementation (20 mg/d for 21 days); however, exercise‐induced nuclear and mitochondrial DNA damage decreased in lymphocytes and muscle following MitoQ. 37

Quantitative analyses conducted for oxidative stress‐related outcomes reported in at least two studies found no significant effect of mitoAOX treatments on malondialdehyde or F2‐Isoprostanes (Table 3 and Figure S5).

3.4. Adverse events and safety‐related outcomes

Seventeen studies included in the review reported on adverse events and/or safety‐related outcomes. Comparisons between mitoAOX and control groups in adverse event reports are shown in Table 4. There appeared to be no differences between mitoAOX and control treatments in the reviewed studies with respect to serious adverse events (SAEs), with only one study reporting one SAE in the Elamipretide arm causing participant discontinuation in the study, 16 and one study reporting one SAE in the placebo arm causing myocardial infarction, death, and participant discontinuation in the study. 36 Non‐serious treatment‐emergent adverse events (TEAEs) tended to be higher with Elamipretide treatment compared with control when it was delivered by subcutaneous injection, largely because of increased mild–moderate injection site‐related reactions such as injection site erythema, bruising, swelling and pruritis. 16 , 17 , 32 , 36 One study reported a higher number of non‐serious TEAEs with MitoQ versus control, because of increased gastrointestinal‐related events such as nausea and vomiting. 25 However, this was not commonly reported across other studies. 30 , 31 , 33 Discontinuation of participation because of TEAEs was minor, with only three studies reporting on a single participant withdrawing because of a TEAE. 16 , 23 , 25 MitoAOX treatments had no apparent effect on all‐cause mortality, CVD‐related mortality, or health condition‐related rehospitalizations versus control in the studies reviewed. 16 , 17 , 22 , 26 , 36 Interestingly, mitoAOX treatments improved kidney function in some studies in patients with CVD‐related impairments, as indicated by increases in the estimated glomerular filtration rate or an attenuated rise in serum creatinine, 24 , 26 , 34 although not in all studies. 22 MitoQ supplementation at 40 and 80 mg/d also improved liver enzyme (aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase) levels in one study in patients with a history of chronic hepatitis C virus infection. 25

4. DISCUSSION

This systematic review evaluated current evidence from RCTs in humans on the effects of mitoAOXs on glycaemic control, cardiovascular health, and oxidative stress. The studies included were diverse with respect to target (clinical) population, specific study outcomes and the type of mitoAOX used. While our findings suggest limited evidence to support the use of mitoAOXs in the management of glycaemic control or cardiovascular health, there are some potentially promising findings that require further investigation. These findings include improved endothelial function (particularly brachial FMD) with mitoAOX supplementation in both healthy participants and in patients with specific health conditions; and improved blood pressure in patients with atherosclerosis‐related impairment of renal blood flow. MitoQ also appeared to be effective in some studies to improve markers of oxidative stress, although the findings overall were mixed. In quantitative analyses, evidence certainty was rated as mostly low to very low across the study outcomes investigated.

Most studies that investigated the effects of Elamipretide involved patients with heart failure. Cardiac measures of global left ventricular systolic performance and remodelling such as LVESV, LVEDV, and LVEF were measured in some studies, with mixed findings reported. One study reported a dose–response‐related effect of Elamipretide on LVESV and LVEDV, 23 which requires further investigation for a consensus on possible dose‐related beneficial effects of Elamipretide in these patients. Based on findings from the small number of studies included in our review, there appears to be limited benefit of mitoAOXs on markers including E/e′, early to late diastolic transmitral flow velocity ratio (E/a), LVGLS and NT‐proBNP in patients with CVD.

Studies were also mixed with respect to improvements in functional capacity in patients with health conditions. However, one study did report a dose‐related improvement in 6‐minute walk test performance with Elamipretide in patients with primary mitochondrial myopathies. 17 Future research needs to be conducted to further investigate possible dose‐related effects of mitoAOX agents like Elamipretide on functional capacity‐related outcomes in specific patient groups. With respect to patient‐important adverse events, current evidence appears to suggest limited effects of mitoAOX agents on all‐cause mortality, CVD‐related mortality, incidence of new congestive heart failure, rehospitalization because of heart failure, and duration of hospitalization. 16 , 17 , 22 , 26 , 36 However, the studies included in the review were mostly short term in duration, with a need for longer term follow‐up studies to better investigate these outcomes.

There is a notable absence of evidence on the effects of mitoAOXs on glycaemic control in humans. There was no evidence that mitoAOXs improved glycaemic control outcomes such as fasting glucose in healthy patients; however, it is unclear how they might affect glycaemic control in patients with impaired glucose metabolism such as type 2 diabetes. Given promising evidence for improvements in glucose intolerance and insulin resistance in preclinical trials with obese rodents using mitoAOXs, 13 , 14 , 15 these findings highlight a clear gap in the literature that should be a focus in future studies.

Current evidence is also lacking overall on the effects of mitoAOXs on oxidative stress outcomes in humans. Some studies, particularly in healthy participants, found improvements in oxidative stress markers with MitoQ supplementation. 19 , 30 , 31 , 33 However, overall, the limited evidence is not suggestive of benefits of mitoAOXs on systemic markers of oxidative stress such as malondialdehyde and F2‐Isoprostanes. Given the pathogenic factors of elevated mitochondrial ROS and oxidative stress in chronic diseases such as CVD and type 2 diabetes, 39 further investigation into the effects of mitoAOXs on mitochondrial ROS and oxidative stress markers is required in target clinical population groups.

Elamipretide and MitoQ appear to be well tolerated in participants, as indicated by a lack of SAEs and mostly mild–moderate TEAEs when they occurred. 16 , 17 , 19 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 Non‐serious TEAEs tended to be higher after subcutaneously injected (but not intravenously infused) Elamipretide because of an increase in injection site‐related events such as pruritis, soreness, erythema and swelling. 16 , 17 , 32 , 36 While this does appear to be a potential drawback to the practicality of this treatment, such adverse events only led to discontinuation of one participant across all the studies reviewed. Based on studies with multiple mitoAOX treatment doses, there did not appear to be any dose‐related effects of Elamipretide or MitoQ on adverse events. It is important to highlight that while we did report on adverse events in the included studies, adverse events were not specified in the search criteria; and thus, this review is not comprehensive with respect to a review of the safety of mitoAOXs. Thus, future reviews are required to provide a more comprehensive review of the safety and adverse effects of mitoAOXs.

The limitations of the current study relate to the variable aspects of the studies included with respect to outcomes, study participants, mitoAOX agent used, and mitoAOX dosage considerations. The findings of quantitative comparisons undertaken should be regarded cautiously, because of factors such as the inclusion of only a small number of studies including specific outcomes, the combining of different mitoAOX agents together, the combining of different population groups together (i.e. patients with specific health conditions and healthy participants) and the combining of different mitoAOX treatment dosages together. There were insufficient studies for specific outcomes to undertake subgroup analyses to further investigate potential areas of participant and supplement heterogeneity. There was a notable absence of studies involving long‐term supplementation with mitoAOX agents, with chronic supplementation studies lasting a median of 28 days (range 5‐84 days). Thus, conclusions are limited to mostly short‐term/acute mitoAOX treatments.

While some included studies did include functional/patient‐important outcomes, mostly only surrogate outcomes were sufficiently measured across studies for quantitative analysis. While a strength of our systematic review is the inclusion of grey literature (conference abstracts/clinical trial registry data), some important study‐related data and outcome data might have been lacking from these data sources. Thus, there was possibly insufficient information available from those studies to allow for a comprehensive and accurate evaluation of risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. Finally, we have only reviewed antioxidant compounds that are (by design) specific to mitochondria. It is probable that other, more generally acting antioxidants, have redox‐related effects in mitochondria. 40 Thus, our review is not comprehensive with respect to all possible antioxidant compounds that have mitochondrial effects.

Overall, there is limited evidence from RCTs to support the use of mitoAOXs for management of glycaemic control and cardiovascular health in humans. There appears to be some potential for the use of mitoAOXs such as MitoQ for improving endothelial function; and future research should focus on the effects of MitoQ on endothelial function and glycaemic control in target clinical populations. At present, the diversity in studies with respect to participant population, outcomes measured, mitoAOX agent used, and dosage regimen used makes it difficult to draw clear conclusions with respect to specific antioxidant agent effectiveness and the most optimal target patient group and optimal dosage regimen.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All named authors conceived the systematic review and were involved in preparation and critical revision of the manuscript. Shaun Mason and Lewan Parker performed systematic searches, study selections, data extractions and risk of bias analyses, with adjudications made by Glenn Wadley and Michelle Keske. Shaun Mason performed quantitative and qualitative data analyses and is guarantor of the work, taking responsibility for integrity and accuracy of the manuscript output.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/dom.14669.

Supporting information

Appendix S1 Supoorting information.

Appendix S2 Check List.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by Deakin University, as part of the Wiley ‐ Deakin University agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians. [Correction added on 18 May 2022: CAUL funding statement has been added.]

Mason SA, Wadley GD, Keske MA, Parker L. Effect of mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidants on glycaemic control, cardiovascular health, and oxidative stress in humans: A systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24(6):1047-1060. doi: 10.1111/dom.14669

Funding informationThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors. Dr Lewan Parker was supported by a NHMRC & National Heart Foundation Early Career Fellowship (APP1157930).

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Angelova PR, Abramov AY. Role of mitochondrial ROS in the brain: from physiology to neurodegeneration. FEBS Lett. 2018;592(5):692‐702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Peoples JN, Saraf A, Ghazal N, Pham TT, Kwong JQ. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in heart disease. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51(12):1‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nishikawa T, Kukidome D, Sonoda K, et al. Impact of mitochondrial ROS production on diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77((Suppl 1)):S41‐S45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sabharwal SS, Schumacker PT. Mitochondrial ROS in cancer: initiators, amplifiers or an Achilles' heel? Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(11):709‐721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Conti V, Izzo V, Corbi G, et al. Antioxidant supplementation in the treatment of aging‐associated diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jenkins DJA, Spence JD, Giovannucci EL, et al. Supplemental vitamins and minerals for CVD prevention and treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2570‐2584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mason SA, Keske MA, Wadley GD. Effects of vitamin C supplementation on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in people with type 2 diabetes: a GRADE‐assessed systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomized controlled trials. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(2):618‐630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jiang Q, Yin J, Chen J, et al. Mitochondria‐targeted antioxidants: a step towards disease treatment. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020;2020:8837893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Manskikh VN, Gancharova OS, Nikiforova AI, et al. Age‐associated murine cardiac lesions are attenuated by the mitochondria‐targeted antioxidant SkQ1. Histol Histopathol. 2015;30(3):353‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ribeiro Junior RF, Dabkowski ER, Shekar KC, Connell KAO, Hecker PA, Murphy MP. MitoQ improves mitochondrial dysfunction in heart failure induced by pressure overload. Free Radic Biol Med. 2018;117:18‐29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ghosh A, Chandran K, Kalivendi SV, et al. Neuroprotection by a mitochondria‐targeted drug in a Parkinson's disease model. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49(11):1674‐1684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yang L, Zhao K, Calingasan NY, Luo G, Szeto HH, Beal MF. Mitochondria targeted peptides protect against 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1,2,3,6‐tetrahydropyridine neurotoxicity. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11(9):2095‐2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coudray C, Fouret G, Lambert K, et al. A mitochondrial‐targeted ubiquinone modulates muscle lipid profile and improves mitochondrial respiration in obesogenic diet‐fed rats. Br J Nutr. 2016;115(7):1155‐1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Feillet‐Coudray C, Fouret G, Ebabe Elle R, et al. The mitochondrial‐targeted antioxidant MitoQ ameliorates metabolic syndrome features in obesogenic diet‐fed rats better than Apocynin or allopurinol. Free Radic Res. 2014;48(10):1232‐1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marín‐Royo G, Rodríguez C, Le Pape A, et al. The role of mitochondrial oxidative stress in the metabolic alterations in diet‐induced obesity in rats. FASEB J. 2019;33(11):12060‐12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butler J, Khan MS, Anker SD, et al. Effects of Elamipretide on left ventricular function in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: the PROGRESS‐HF phase 2 trial. J Card Fail. 2020;26(5):429‐437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Karaa A, Haas R, Goldstein A, Vockley J, Weaver WD, Cohen BH. Randomized dose‐escalation trial of elamipretide in adults with primary mitochondrial myopathy. Neurology. 2018;90(14):e1212‐e1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Snow BJ, Rolfe FL, Lockhart MM, et al. A double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study to assess the mitochondria‐ targeted antioxidant MitoQ as a disease‐modifying therapy in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25(11):1670‐1674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Broome SC, Braakhuis AJ, Mitchell CJ, Merry TL. Mitochondria‐targeted antioxidant supplementation improves 8 km time trial performance in middle‐aged trained male cyclists. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2021;18(1):58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sterne JA, Gavaghan D, Egger M. Publication and related bias in meta‐analysis: power of statistical tests and prevalence in the literature. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53(11):1119‐1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Balshem H, Helfand M, Schunemann HJ, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401‐406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cleland JGF, Carr J, Pellicori P, et al. Improving diuresis and dropsy with elamipretide in advanced heart failure (IDDEA‐HF); a multi‐centre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(Suppl. S1):5–592.32745277 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Daubert MA, Yow E, Dunn G, et al. Novel mitochondria‐targeting peptide in heart failure treatment: a randomized, placebo‐controlled trial of Elamipretide. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10(12):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eirin A, Herrmann SM, Saad A, et al. Urinary mitochondrial DNA copy number identifies renal mitochondrial injury in renovascular hypertensive patients undergoing renal revascularization: a pilot study. Acta Physiol. 2019;226(3):e13267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gane EJ, Weilert F, Orr DW, et al. The mitochondria‐targeted anti‐oxidant mitoquinone decreases liver damage in a phase II study of hepatitis C patients. Liver Int. 2010;30(7):1019‐1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gibson CM, Giugliano RP, Kloner RA, et al. EMBRACE STEMI study: a phase 2a trial to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of intravenous MTP‐131 on reperfusion injury in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(16):1296‐1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Karaa A, Haas R, Goldstein A, Vockley J, Cohen BH. A randomized crossover trial of elamipretide in adults with primary mitochondrial myopathy. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2020;11(4):909‐918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kirkman DL, Muth BJ, Ramick MG, Townsend RR, Edwards DG. Role of mitochondria‐derived reactive oxygen species in microvascular dysfunction in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2018;314(3):F423‐F429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kirkman DL, Shenouda N, Stock JM, et al. The effects of a mitochondrial targeted ubiquinone (MitoQ) on vascular function in chronic kidney disease. AHA Scientific Sessions. 2020;142(Suppl. 3):A16926. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Park SY, Pekas EJ, Headid RJ, et al. Acute mitochondrial antioxidant intake improves endothelial function, antioxidant enzyme activity, and exercise tolerance in patients with peripheral artery disease. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2020;319(2):H456‐H467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pham T, MacRae CL, Broome SC, et al. MitoQ and CoQ10 supplementation mildly suppresses skeletal muscle mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide levels without impacting mitochondrial function in middle‐aged men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2020;120(7):1657‐1669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Reid Thompson W, Hornby B, Manuel R, et al. A phase 2/3 randomized clinical trial followed by an open‐label extension to evaluate the effectiveness of elamipretide in Barth syndrome, a genetic disorder of mitochondrial cardiolipin metabolism. Genet Med. 2021;23(3):471‐478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rossman MJ, Santos‐Parker JR, Steward CAC, et al. Chronic supplementation with a mitochondrial antioxidant (MitoQ) improves vascular function in healthy older adults. Hypertension. 2018;71(6):1056‐1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Saad A, Herrmann SMS, Eirin A, et al. Phase 2a clinical trial of mitochondrial protection (Elamipretide) during stent revascularization in patients with atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2017;10(9):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Shill DD, Southern WM, Willingham TB, Lansford KA, McCully KK, Jenkins NT. Mitochondria‐specific antioxidant supplementation does not influence endurance exercise training‐induced adaptations in circulating angiogenic cells, skeletal muscle oxidative capacity or maximal oxygen uptake. J Physiol. 2016;594(23):7005‐7014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Stealth Biopharmaceuticals Inc A Phase 2 Randomized, Double‐Blinded, Placebo‐Controlled Study to Evaluate the Effects of 4 Weeks Treatment with Subcutaneous Elamipretide on Left Ventricular Function in Subjects with Stable Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. [Clinical trial]. In press, 2021.

- 37. Williamson J, Hughes CM, Cobley JN, Davison GW. The mitochondria‐targeted antioxidant MitoQ, attenuates exercise‐induced mitochondrial DNA damage. Redox Biol. 2020;36:101673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ceriello A, Testa R. Antioxidant anti‐inflammatory treatment in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(suppl 2):S232‐S236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Wesselink E, Koekkoek WAC, Grefte S, Witkamp RF, van Zanten ARH. Feeding mitochondria: potential role of nutritional components to improve critical illness convalescence. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(3):982‐995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1 Supoorting information.

Appendix S2 Check List.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.