The World Health Organization recommends exclusive breastfeeding for at least 6 months for health reasons, and it could be associated with better infant development outcomes that continue into childhood and adolescence. 1 Temperamental‐based behavioural traits and maternal anxiety are well‐known key contributors to infants' cognitive and developmental outcomes. 2 However, studies have disagreed on associations between exclusive breastfeeding and infants' temperament. Lauzon‐Guillain et al. 3 reported lower regulatory capacities and higher negative effects in exclusively breastfed 3‐month‐old infants than formula‐fed infants. Another study reported that exclusive breastfeeding at 3 months was associated with lower levels of infants' negative emotionality at 18 months. 4 We believe this is the first study to explore the independent and interactive effects of exclusive breastfeeding and postnatal maternal anxiety on infants' temperament.

The cohort was drawn from the Italian Measuring the Outcomes of Maternal COVID‐19‐related Prenatal Exposure study. 5 Data on 320 mother–infant dyads were collected from 10 neonatal units in northern Italy from May 2020 to August 2021. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the lead institution (IRCCS Mondino Foundation) and the participating hospitals. All the mothers provided written informed consent. They completed online surveys, at childbirth (T0) and after 6 months (T1), on whether they were using exclusive breastfeeding, maternal milk from a bottle, formula or mixed feeding methods. At birth (T0), the mothers also filled in the state‐anxiety scale of the State‐Trait Anxiety Inventory—which provides a quantitative score from 20 to 80. After their infants reached 6 months (T1), they filled in the Infant Behavior Questionnaire‐Revised short‐form, which provides a quantitative estimation of three main temperament domains: surgency, negative emotionality and regulatory capacity.

At 6 months, 217/320 (69%) mother–infant dyads remained in the study: 42% had exclusive breastfeeding since birth and 58% had discontinued. The groups did not significantly differ with regard to mean gestational age, birth weight, 5‐min Apgar score, mode and complexity of delivery and mean maternal age (Table S1).

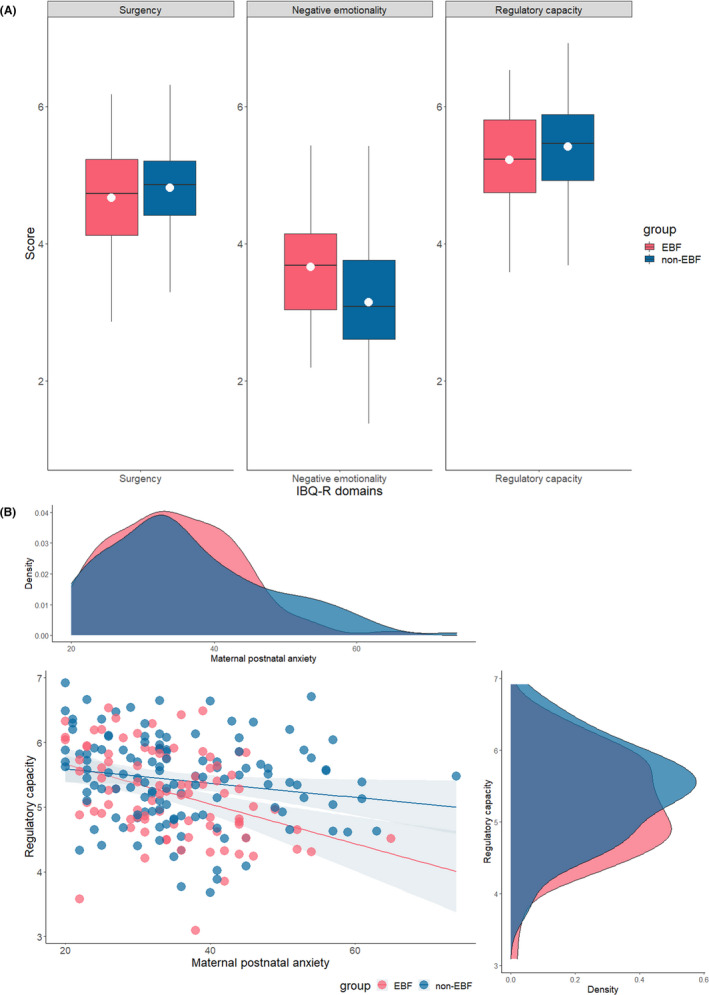

Maternal postnatal anxiety significantly correlated with the infants' regulatory capacity (r = −0.24, p < 0.001), but not with surgency and negative emotionality. Separate between‐subject t‐tests were carried out between the groups of exclusively breastfed and nonexclusively breastfed infants on the three temperament domains. Exclusively breastfed infants exhibited higher levels of negative emotionality (p < 0.001) and lower regulatory capacity (p = 0.042) than the other group, with no significant differences for surgency (Figure 1A and Table S1). Three separate hierarchical linear regression models were used to assess the independent and interaction effects of exclusive breastfeeding and maternal postnatal anxiety on infant temperament. A significant model was obtained for regulatory capacity (R 2 = 0.10, p = 0.039.) Significant main effects emerged for exclusive breastfeeding (B = 0.221, 95% C.I. [0.041:0.402], p = 0.016) and for postnatal maternal anxiety (B = −0.017, 95% C.I. [−0.026:−0.008], p < 0.001.) The main effects were further explained by a significant interaction effect (B = 0.020, 95% C.I. [0.001:0.039], p = 0.039). The post hoc investigation revealed a significant negative association between postnatal maternal anxiety and infants' regulatory capacity in the exclusive breastfeeding group, R 2 = 0.15, p < 0.001, compared with the other group, R 2 = 0.03, p = 0.025.

FIGURE 1.

(A) Effect of exclusive breastfeeding from birth to 6 months on infants' temperament. (B) Interaction effect of exclusive breastfeeding and maternal postnatal anxiety on infant's regulatory capacity at 6 months

Mothers who exclusively breastfed for 6 months reported that their infants had more challenging temperaments, in particular for negative emotionality and regulatory capacity. These results are consistent with the previous study, 3 which reported that exclusively breastfed infants were more irritable and cried more than formula‐fed controls. These findings suggest that exclusive breastfeeding may be highly demanding for mothers and infants. In the light of mixed evidence from previous literature, 4 these findings might shed new light by incorporating maternal postnatal anxiety in the explanatory model. We found that poorer regulatory temperament was much more prominent in exclusively breastfed infants if their mothers had high postnatal anxiety. In contrast, when maternal postnatal anxiety was not elevated, there were no differences in regulatory skills between the exclusive and nonexclusive breastfeeding infants. We could speculate that some anxious mothers may stop exclusive breastfeeding before 6 months. However, infants could have a higher risk of developing less‐than‐optimal regulatory skills when breastfeeding continues, despite elevated anxiety levels.

Our study was based on self‐reports from a specific geographical area in Northern Italy, and this was a limitation. In addition, the data were collected during the COVID‐19 pandemic, and pandemic‐related stress and social restrictions may have elevated maternal anxiety. 5

In conclusion, the present study suggests that previous controversial data on the effects of exclusive breastfeeding on infants' temperament during the first months of life may be better understood in the context of maternal postnatal anxiety. Exclusive breastfeeding recommendations should consider maternal well‐being and parenting beliefs. Especially, when relevant maternal anxiety symptoms are present, promoting breastfeeding without taking care of psychological issues may have detrimental effects. Preventive interventions are warranted to be delivered at an early stage to new mothers.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

Funding information

This study is supported by funds from the Italian Ministry of Health (Cinque per Mille 2017) and from Fondazione Roche (Fondazione Roche per la Ricerca Indipendente 2020) to author LP.

Supporting information

Tab S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Renato Borgatti for mentoring and supervising the study and Elisa Roberti, Francesca Masoni, Vanessa Manfredini, Giada Pettenati and Luisa Vercellino for helping with the data collection and curation. Open Access Funding provided by Universita degli Studi di Pavia within the CRUI‐CARE Agreement.

APPENDIX 1.

MOM‐COPE Study Group: Giulia Bensi, Giacomo Biasucci, Anna Cavallini, Lidia Decembrino, Rossana Falcone, Elisa Fazzi, Barbara Gardella, Roberta Longo, Maria Luisa Magnani, Renata Nacinovich, Dario Pantaleo, Benedetta Pietra, Camilla Pisoni, Federico Prefumo, Barbara Scelsa, Pierangelo Veggiotti.

Grumi S, Capelli E, Giacchero R, Anceresi G, Fullone E, Provenzi L; Measuring the Outcomes of Maternal COVID‐19‐related Prenatal Exposure Study Group . Exclusive breastfeeding and maternal postnatal anxiety contributed to infants' temperament issues at 6 months of age. Acta Paediatr. 2022;111:1380–1382. doi: 10.1111/apa.16333

Measuring the Outcomes of Maternal COVID‐19‐related Prenatal Exposure Study Group members listed in Appendix 1.

[Correction added on 14 May 2022, after first online publication: CRUI‐CARE funding statement has been added.]

Contributor Information

Livio Provenzi, Email: livio.provenzi@unipv.it.

Measuring the Outcomes of Maternal COVID‐19‐related Prenatal Exposure Study Group:

Giulia Bensi, Giacomo Biasucci, Anna Cavallini, Lidia Decembrino, Rossana Falcone, Elisa Fazzi, Barbara Gardella, Roberta Longo, Maria Luisa Magnani, Renata Nacinovich, Dario Pantaleo, Benedetta Pietra, Camilla Pisoni, Federico Prefumo, Barbara Scelsa, and Pierangelo Veggiotti

REFERENCES

- 1. Krol KM, Grossmann T. Psychological effects of breastfeeding on children and mothers. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2018;61(8):977‐985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Behrendt H, Wade M, Bayet L, Nelson C, Bosquet EM. Pathways to social‐emotional functioning in the preschool period: the role of child temperament and maternal anxiety in boys and girls. Dev Psychopathol. 2020;32(3):961‐974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lauzon‐Guillain BD, Wijndaele K, Clark M, et al. Breastfeeding and infant temperament at age three months. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jonas W, Atkinson L, Steiner M, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal sensitivity predict early infant temperament. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104(7):678‐686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Provenzi L, Grumi S, Giorda R, et al. Measuring the outcomes of maternal COVID‐19‐related prenatal exposure (MOM‐COPE): study protocol for a multicentric longitudinal project. BMJ Open. 2020;10(12):e044585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Tab S1