Abstract

A fluorescence method to monitor lysis of cheese starter bacteria using dual staining with the LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit is described. This kit combines membrane-permeant green fluorescent nucleic acid dye SYTO 9 and membrane-impermeant red fluorescent nucleic acid dye propidium iodide (PI), staining damaged membrane cells fluorescent red and intact cells fluorescent green. For evaluation of the fluorescence method, cells of Lactococcus lactis MG1363 were incubated under different conditions and subsequently labeled with SYTO 9 and PI and analyzed by flow cytometry and epifluorescence microscopy. Lysis was induced by treatment with cell wall-hydrolyzing enzyme mutanolysin. Cheese conditions were mimicked by incubating cells in a buffer with high protein, potassium, and magnesium, which stabilizes the cells. Under nonstabilizing conditions a high concentration of mutanolysin caused complete disruption of the cells. This resulted in a decrease in the total number of cells and release of cytoplasmic enzyme lactate dehydrogenase. In the stabilizing buffer, mutanolysin caused membrane damage as well but the cells disintegrated at a much lower rate. Stabilizing buffer supported permeabilized cells, as indicated by a high number of PI-labeled cells. In addition, permeable cells did not release intracellular aminopeptidase N, but increased enzyme activity was observed with the externally added and nonpermeable peptide substrate lysyl-p-nitroanilide. Finally, with these stains and confocal scanning laser microscopy the permeabilization of starter cells in cheese could be analyzed.

Lactic acid bacteria in cheese starters have a dual role during cheese manufacture. Initially, they are responsible for the rapid acidification of the milk through efficient conversion of lactose into lactic acid. In a later stage of the process the proteolytic, peptidolytic, and amino acid-converting enzymes of the starter bacteria play a crucial role in the generation of flavor components. Most of these enzymes are located in the cytoplasm, while their substrates are mostly present outside the cells in the cheese matrix. Lysis results in leakage of intracellular enzymes. Therefore, lysis of the starter lactic acid bacteria is generally considered an essential part of the ripening process (2, 12, 20, 30).

Lysis in cheese depends on the choice of the strain and is strongly influenced by cheese-processing conditions such as pH, temperature, and salt concentration (2, 7, 30). By selecting rapidly lysing strains and process conditions that favor lysis, flavor development may be enhanced during ripening (9, 15). A major drawback in this selection is the difficulty in demonstrating lysis, especially in cheese.

Lysis is mostly studied in aqueous systems. In clear growth medium lysis can be observed by the decrease of turbidity. Other markers for monitoring lysis are decrease of viable counts, release of DNA, and release of intracellular enzymes (2, 19, 30). In cheese, however, these methods cannot be applied directly. Usually, an elaborate extraction procedure, which can be so rigorous that major cell damage or cell death is induced, is required. This makes an evaluation of the original cell integrity in the cheese almost impossible (8, 30). Another complicating factor is the occurrence, in cheese, of starter cells in different stages of cell disintegration, such as spheroplast cells (9, 29). Electron microscopy studies have shown that this spheroplast stage, when the cells seemed to leak proteins and ribosomes, was followed by major disruption of the cell membrane and release of the intracellular content. After complete lysis only residual material could be identified in cheese (e.g., ribosomes) (7). The osmotically fragile spheroplasts may be prevented from disruption by an osmostabilizing effect of the cheese environment (27). Alternative methodologies for extraction such as using a cheese press and using hypertonic buffers have been tried (30). However, to date no really good method is available, and an understanding of the role of lysis in cheese ripening is still lacking (8, 22).

Fluorescent probes provide alternative methods for assessment of bacterial physiology (4, 10; P. Haugland, Handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals, 7th ed., Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.). With flow cytometry (FCM) individual cells in solution can rapidly be measured with high sensitivity and accuracy (24). With confocal scanning laser microscopy (CSLM) individual cells can be observed in solid matrices without the need for extraction.

The aim of this study was to develop an accurate and rapid method to measure lysis of cheese bacteria. In this work we demonstrate and quantify cell permeabilization and disruption of Lactococcus lactis in a buffer that stabilizes the cells, simulating cheese conditions. We applied the stains of the commercially available LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit of Molecular Probes, SYTO 9, and propidium iodide (PI) (P. Haugland, Handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals, 7th ed., Molecular Probes). We show that the lysis process can be monitored with these stains by counting the number of intact and permeable cells at different time points. We also show the practical relevance of permeable cells in the lysis process by measurement of the accessibility of the intracellular peptidolytic enzyme aminopeptidase N (PepN). Finally, the direct application of the stains in combination with CSLM for cheese studies is described.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strain and culture conditions.

L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363 was routinely stored in M17 broth (Oxoid, Haarlem, The Netherlands) with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose and 15% (wt/vol) glycerol at −80°C. A culture was grown overnight in M17 supplemented with 0.5% (wt/vol) glucose (GM17) at 30°C without aeration. The overnight culture was diluted 50-fold with fresh GM17 and further incubated at 30°C until the culture had reached an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 1.0 (exponential growth phase). After harvest the cells were washed once with 50 mM sodium phosphate (NaPi) buffer, pH 6.5, and resuspended in the same buffer.

Induction of lysis and stabilization of permeabilized cells.

The cell suspension was divided into two equal portions. One portion was resuspended in NaPi buffer, pH 6.5, referred to as control buffer. The other portion was resuspended in buffer consisting of 50 mM NaPi, 400 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, and 5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA), pH 6.5, referred to as stabilizing buffer. For each cell suspension three 10-ml portions were transferred to new tubes and 0, 10, and 100 U of mutanolysin (Sigma-Aldrich Chemie BV, Zwijndrecht, The Netherlands)/ml were added, respectively. The cells were incubated at 30°C, and the decrease of turbidity was monitored by measurements of optical density at 600 nm. At various time points samples were taken for analyses.

Plate counts.

Samples were serially diluted in peptone physiological salt solution (Tritium Microbiologie B.V., Veldhoven, The Netherlands), and 1-ml portions of the appropriate dilution were spread out on plastic petri disks in duplicate. Twenty milliliters of molten GM17 agar (GM17 with 1.5% [wt/vol] agar, 46°C) was poured out on the plates. After incubation for 2 days at 30°C the colonies were counted.

Fluorescence labeling.

The LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit with separate solutions of SYTO 9 and PI (Molecular Probes) contains high-concentration stock solutions in dimethyl sulfoxide: 3.34 mM SYTO 9 and 20 mM PI. Fresh dilutions of 0.5 mM SYTO 9 and 1.5 mM PI in distilled water were prepared daily and kept in the dark at 4°C. Fifty-microliter portions of the samples were incubated with SYTO 9, with PI, or with both or without dye for 10 min at 30°C. The final dye concentrations were 10 μM SYTO 9 and 30 μM PI.

Epifluorescence microscopic counting.

Countings were performed with an image analysis system connected to a Dialux microscope (Ernst Leitz, Wetzlar, Germany) that was equipped with a 50-W mercury arc lamp and a Leitz fluorescein isothiocyanate filter (excitation wavelength, 450 to 490 nm; emission wavelength, >515 nm). The emitted light was directed to a charge-coupled device (CCD) camera with C-mount at ×0.63 (COHU high-performance CCD camera; Leica, Rijswijk, The Netherlands). Images were recorded using the Q-Fluoro software package (Leica). Samples labeled only with PI were used in these experiments. The total number of cells was determined from images recorded with phase-contrast illumination. The number of PI-labeled cells was determined from images recorded with epifluorescence illumination. The averages of three image fields were calculated.

FCM.

FCM was performed with cell suspensions labeled with SYTO 9 and PI, with SYTO 9 only, or with PI only and with nonlabeled cells. Cell suspensions were diluted in 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffers that had been filtered using a 0.2-μm-pore-size filter. Cells that had been incubated in control buffer were diluted in buffer containing 100 mM MES and 50 mM KCl at pH 6.5 (MES control buffer). Cells that had been incubated in stabilizing buffer were diluted in buffer containing 100 mM MES, 450 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, and 5% BSA at pH 6.5 (MES stabilizing buffer). Yellow-green fluorescent polystyrene microspheres with a diameter of 0.7 μm (Polysciences Europe GmbH; Eppelheim, Germany) were used to enable enumerations of cells in the FCM samples. FCM samples were prepared by mixing 2 μl of cell suspension, 100 μl of fluorescent bead suspension (1.335 × 107 beads per ml), and either MES control buffer or MES stabilizing buffer to a total volume of 1,000 μl. Thus, the concentration of fluorescent beads in the FCM sample was exactly 1.335 × 106 beads per ml and the concentration of cells was between 106 and107 cells per ml, depending on the cell incubation conditions.

Flow-cytometric analyses were performed with a FACSCalibur flow cytometer and data analysis software as described previously (5). A side scatter (SSC) threshold level was used to reduce background noise. The cell samples were delivered at the low flow rate, which gave 300 to 600 events per s. We used 2 min of data acquisition, which permitted measurement of on average 40,000 cells. For each cell, forward scatter (FSC), SSC, green fluorescence (515 to 545 nm), yellow-orange fluorescence (564 to 606 nm), and red fluorescence (>670 nm) were recorded. The data were analyzed using dot plots, i.e., bivariate displays in which each dot represents one measured event.

In the dot plot of FSC and SSC the cells and the beads gave distinct, nonoverlapping populations, and a cell region and a bead region were created for gating. The subpopulations of SYTO 9-labeled cells and PI-labeled cells were distinguished best in the red fluorescence histogram gated on cells. The beads gave a series of subpopulations with decreasing number at increasing FSC, SSC, and fluorescence signals, corresponding to single beads, double beads, etc. This was confirmed by fluorescence microscopic examination, which showed that the bead suspension contained mainly single beads but also some chains of two beads, three beads, and even four beads. The total number of beads was calculated by taking all bead subpopulations that gave distinct peaks in the green fluorescence histogram into account, usually up to four peaks. The concentrations of SYTO 9-labeled cells and PI-labeled cells were calculated from the ratios of cells to beads and the known concentration of beads.

The accuracy of counts is indicated by the coefficient of variation (CV). In a counting of n items, the associated standard deviation is n1/2. The CV is the standard deviation over the mean. The CV is a common measure of precision (24).

Enzyme assays.

l-Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) activity was assayed by measurement of the decrease of A340 resulting from the pyruvate-dependent oxidation of NADH as described previously (31). For measurement of the total LDH activity cell extract was used. This was prepared by disruption of the cell suspension with zirconium beads by bead beating twice for 30 s each using a FastPrep FP120 (Bio 101, Savant Instruments, Holbrook, N.Y.). The disrupted cell suspension was centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C, and the supernatant was carefully pipetted into another tube for use. Released LDH activity was determined by using supernatant of the centrifuged cell suspension.

Aminopeptidase N (PepN) activity was assayed as described previously (14). l-lysyl-p-nitroanilidedihydrobromide was used as the substrate because it is not permeant and therefore not hydrolyzed in a suspension of intact living cells at pH 6.5 (14). By incubating a whole-cell suspension with the substrate the accessible PepN activity was measured. Furthermore, the released activity was measured using supernatant of the centrifuged cell suspension.

CSLM of labeled cheese.

Slices of 2-week-old Gouda cheese (5 by 5 by 2 mm) were cut with a razor blade and placed on a microscope slide. A staining mixture with 20 μM SYTO and 60 μM PI (25 μl) was spread out on the freshly cut cheese surface, and a coverslip was placed on top. The cheese slice was thus incubated with the stains for 30 to 60 min in the dark at room temperature. The CSLM work was carried out using a Leica TCS SP confocal scanning laser microscope (Leica) with an argon-krypton laser (488- and 568-nm excitation) and a ×63 objective with a numerical aperture of 1.2. Maximum emission intensities were at 520 to 530 nm for SYTO 9 and 645 to 655 nm for PI. CSLM images were obtained 10 μm below the level of the coverslip.

RESULTS

Induction of lysis and stabilization of permeabilized cells.

Model strain L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363 was used as the test organism. Cells harvested in mid-exponential phase were resuspended in buffer containing 50 mM NaPi, pH 6.5 (control buffer), and mutanolysin was added to induce lysis to a final concentration of 10 or 100 U/ml or cells were incubated without mutanolysin. Also, cells were resuspended in a buffer with high protein and high salt concentrations (50 mM NaPi, 400 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, and 5% BSA, pH 6.5), referred to as stabilizing buffer, and incubated without mutanolysin or with 10 or 100 U of mutanolysin/ml. Cell suspensions were incubated for 22 h at 30°C.

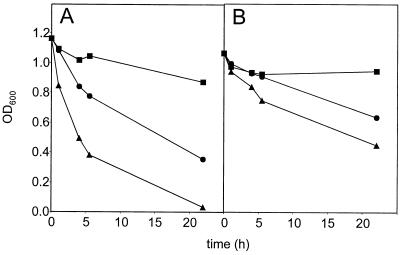

A typical example of the effect of mutanolysin treatment on the turbidity of the cell suspension in control buffer is shown in Fig. 1A. Without mutanolysin there was only a slight decrease in the turbidity, caused by spontaneous lysis. With 10 U of mutanolysin/ml the turbidity decreased considerably. With 100 U of mutanolysin/ml the turbidity decreased fast and the suspension was almost cleared after 22 h. In stabilizing buffer the turbidity decreased at a lower rate (Fig. 1B). In the example shown it decreased in 22 h only one-half as much as in control buffer. Both the mutanolysin-induced lysis and the spontaneous lysis were slower in stabilizing buffer.

FIG. 1.

Effect of mutanolysin treatment on the turbidity of the L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363 cell suspension. Cells were incubated in control buffer (A) and in stabilizing buffer (B) at 30°C with 0 (squares), 10 (circles), or 100 (triangles) U of mutanolysin/ml. OD600, optical density at 600 nm.

The survival of the cells under the various incubation conditions was tested by plate counting (Table 1). The number of CFU decreased much more than the turbidity. Without mutanolysin the CFU decreased by 1/2 log unit. Mutanolysin caused a further decrease of CFU, down to a survival of less than 1%. There was no obvious difference between survival in control buffer and survival in stabilizing buffer.

TABLE 1.

Effect of 22 h of mutanolysin treatment on L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363 viability

| Buffera | Treatment | LG CFU/ml in expt:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| Control | No incubation | 9.3 | 9.2 |

| Incubation without mutanolysin | 8.5 | 8.6 | |

| Incubation with 10 U of mutanolysin/ml | 8.1 | 6.9 | |

| Incubation with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml | 6.7 | 8.5 | |

| Stabilizing | No incubation | 9.2 | 9.2 |

| Incubation without mutanolysin | 8.7 | 8.8 | |

| Incubation with 10 U of mutanolysin/ml | 7.6 | 8.5 | |

| Incubation with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml | 7.8 | 8.0 | |

Control buffer: 50 mM NaPi, pH 6.5; stabilizing buffer: 50 mM NaPi, 400 mM KCl, 20 mM MgCl2, 5% BSA, pH 6.5.

Release of LDH.

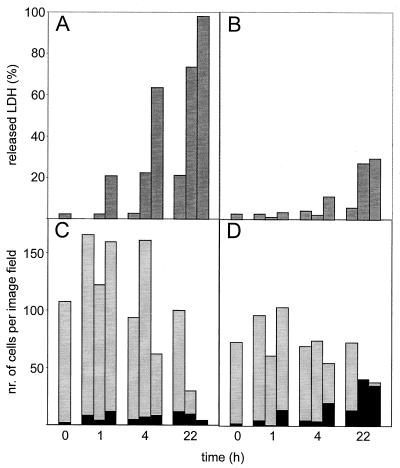

LDH is a cytoplasmic protein, and in most lactic acid bacteria it is a key enzyme in metabolism. It is commonly used as a marker for lysis. The LDH activities of supernatant and of cell extract were measured, and the ratio was taken as the fraction of LDH released. The LDH releases in stabilizing buffer were much lower than those in control buffer. In the example shown 21% of the LDH was released after 22 h of incubation in control buffer without mutanolysin as a result of spontaneous lysis (Fig. 2A). When cells were treated with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml, almost all LDH was released. In stabilizing buffer spontaneous lysis resulted in release of only 6% of total LDH after 22 h, and treatment with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml resulted in release of 29% of total LDH (Fig. 2B). For a control, the effect of buffer composition on the activity of LDH was measured. The presence of BSA, potassium, and magnesium had no influence on the activity level of LDH (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of mutanolysin treatment on LDH release and on total and permeable cell numbers of L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363. Cells were incubated in control buffer (A and C) and stabilizing buffer (B and D) at 30°C with 0 (left bar), 10 (middle bar), or 100 (right bar) U of mutanolysin/ml. The released LDH percentage is the ratio of supernatant (released) and cell extract (total) activity (A and B). The microscopic counts of total cells (total height of the bars) and permeable cells (black part) were done by fluorescence microscopy image analysis using PI labeling. Average numbers of three image fields were calculated (C and D).

Fluorescence microscopy.

Fluorescence labeling and microscopy allowed direct observations of the individual cells in the suspension. Samples were labeled with SYTO 9 and PI and analyzed with epifluorescence microscopy. Before incubation the concentration of cells was high and almost all cells were intact. After 20 h of incubation with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml in control buffer the number of cells was much lower. In contrast, in stabilizing buffer, the concentration of cells remained high but many of the cells were permeabilized as indicated by PI labeling.

Figure 2C and D show the results of a counting experiment using image analysis. In control buffer the total number of cells decreased as a function of time and mutanolysin concentration. The remaining number of cells after 22 h of incubation with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml was less than 5% of the number of cells before incubation. The numbers of permeable cells under these conditions were low. Under stabilizing conditions, on the other hand, the decrease of cell numbers was much smaller, with the lowest recorded values still remaining above 50%. However, the fraction of permeable cells increased with time and mutanolysin concentration. After 22 h of incubation with 10 or 100 U of mutanolysin/ml nearly all remaining cells were labeled by PI. The difference between the total number of cells and the number of permeable cells represents the number of intact cells. In stabilizing buffer the number of intact cells was similar to the number in control buffer.

Comparisons of LDH release and microscopic countings show that the LDH release coincided with the decrease in total numbers of cells. The results indicate that mutanolysin treatment caused cell damage, rendering the cells permeable for PI but not for LDH. In control buffer, cell damage rapidly causes complete cell disruption, resulting in complete LDH release. Under stabilizing conditions, cell disruption is a much slower process, and therefore LDH appears much more gradually in the external medium.

FCM.

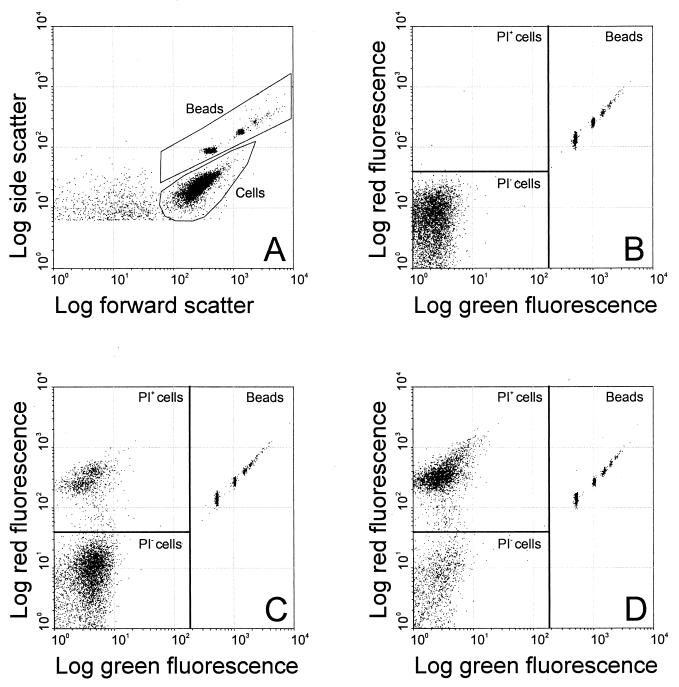

Cell suspensions labeled with SYTO 9 and PI were diluted in MES-based buffers to 106 to 107 cells per ml, and yellow-green fluorescent polystyrene beads were added to enable calculations of cell numbers. The permeable cells were distinguished by PI labeling. Figure 3 shows typical FCM results. In the FSC-SSC plot (Fig. 3A) a region of beads and a region of cells were identified. Within the bead region subpopulations of single beads, double beads, etc., were observed. Figure 3B to D show dot plots of green fluorescence and red fluorescence gated for cells and beads of untreated cells (B), cells incubated in stabilizing buffer for 21 h without mutanolysin (C), and cells incubated for 21 h with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml (D). The beads gave distinct subpopulations in the upper left quadrant. The PI-stained cells gave a population with high red fluorescence and low green fluorescence (PI+). The cells that were not stained by PI but by SYTO 9 gave a population with low fluorescence signals (PI−). In untreated cell suspensions very few cells were stained by PI (Fig. 3B). The total number of cells did not change in stabilizing buffer, but the fraction of permeable cells increased with time and mutanolysin concentration. After 21 h of incubation without mutanolysin 17% of cells were permeable as indicated by PI+ staining (Fig. 3C), whereas the sample with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml contained 70% permeable cells (Fig. 3D). In control buffer (not shown) the total number of cells decreased as a function of time and mutanolysin concentration and the number of permeable cells remained low. After 21 h with 0, 10, and 100 U of mutanolysin/ml the total number of cells was decreased to 75, 68, and 37%, respectively. Of the remaining cells less than 10% were permeable.

FIG. 3.

Effect of mutanolysin treatment on cell number and membrane permeability of L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363 shown by SYTO 9 and PI labeling and FCM. Shown are a dot plot of FSC and SSC (A) and dot plots of green and red fluorescence gated for cells and beads of an untreated cell suspension (B), a cell suspension incubated for 21 h in stabilizing buffer (C), and a cell suspension incubated for 21 h in stabilizing buffer with 100 U of mutanolysin/ml (D).

As expected, FCM counting results corresponded with microscopic counting results, but the advantage of the FCM countings is that they give the actual number of cells per milliliter.

Furthermore, the FCM results are more accurate since more cells are counted. The average total cell count by FCM was 40,000. A count of 40,000 has a CV of 0.5%. When the PI-labeled subpopulation was as small as 5%, the CV of this subpopulation (2,000 events) was still only 2.2%. With fluorescence microscopy, on average 250 cells were counted as the total of three image fields. The CV of a total count of 250 is 6%, and the CV of a subpopulation that comprises 5% of the cells is 28%. The imprecision of the plate counts is similar to that of the microscopic counts, since the counted numbers were on the same order of magnitude.

The results show that fluorescence staining with SYTO 9 and PI and analysis with FCM constitute a highly accurate and straightforward method for assessment of total, intact, and permeable cell numbers.

Release and accessibility of PepN.

Peptidases are an important group of enzymes in the generation of flavor components in cheese (18). Aminopeptidase N is an intracellular enzyme capable of catalyzing the hydrolysis of a wide range of substrates, and it has a strong debittering effect in cheese ripening. Cells have to be disrupted for release of the enzyme. To assay PepN activity, we used the artificial substrate l-lysyl-p-nitroanilidedihydrobromide, which releases the chromophoric (yellow) p-nitroaniline upon cleavage. Intact cells cannot catalyze this reaction since the substrate cannot permeate through the intact cell envelope. In a cell suspension, cleavage of the substrate can be a result of PepN released into the external medium or of intracellular PepN that has become accessible for the substrate because of cell permeabilization. We observed high cell-associated PepN activity specifically under conditions that resulted in permeabilization of the cells. Table 2 shows the results of an experiment using 21-h incubations with 10 U of mutanolysin/ml. In stabilizing buffer, 75% of the accessible enzyme activity was localized in the cell and only 25% was localized outside. In control buffer, 20% of the accessible enzyme activity was intracellular and 80% was released. The total measured PepN activity in stabilizing buffer was approximately the same as in control buffer, but the amount of activity released was much lower. The results show that intracellular enzymes become accessible for peptidase substrates when cells become permeable. This is specifically relevant for conditions found in cheese, where cell lysis is slow and many cells are present for prolonged periods of time in an intermediate, and permeable, stage of cell disruption.

TABLE 2.

Effect of mutanolysin treatment on the PepN activity of L. lactis subsp. lactis MG1363d

| Buffer | Time (h) | PepN activity (ΔA450/min/ml)

|

% PI labeled | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total accessiblea | Releasedb (%) | Intracellularc (%) | |||

| Control | 3 | 0.031 | 0.004 | 0.027 | 2 |

| 21 | 0.184 | 0.147 (80) | 0.037 (20) | 26 | |

| Stabilizing | 3 | 0.043 | 0.023 | 0.020 | 6 |

| 21 | 0.197 | 0.049 (25) | 0.148 (75) | 84 | |

Total accessible activity was assayed by measuring activity of a whole-cell suspension.

Released activity was assayed by measuring the activity of supernatant.

Intracellular fraction of accessible activity was calculated by subtracting the released activity from the total accessible activity.

Cells were incubated in control buffer and stabilizing buffer with 10 U of mutanolysin/ml.

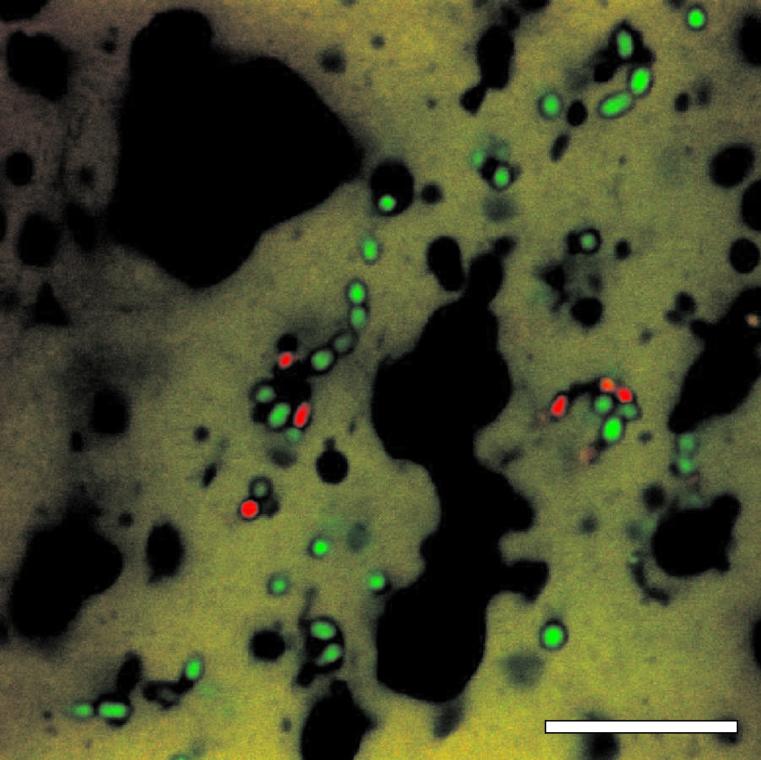

Lysis in cheese.

Thin slices of young, 2-week-old Gouda cheese were incubated with SYTO 9 and PI and were analyzed by CSLM. CSLM allowed clear observations of stained cells within the cheese matrix (Fig. 4). A majority of the starter cells were intact as shown by their green fluorescence. However, a substantial number of the cells were permeable as indicated by PI labeling. These results show that the cheese matrix supports permeable cells. As in stabilizing buffer, the lytic processes cause permeabilization but complete disruption is postponed by the stabilizing conditions. So the presence of permeable cells is an important feature during cheese ripening.

FIG. 4.

CSLM image of 2-week-old Gouda cheese stained with SYTO 9 and PI. Bar, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

In this paper we describe an effective method for measuring cell permeabilization in cheese. The measurement of lysis in cheese has always been a major problem (7, 9). Because the decrease of cell turbidity cannot be measured in cheese, other markers for lysis have been used such as decrease of viable counts, release of DNA, and release of intracellular enzymes, such as phospho-β-galactosidase, LDH, and different peptidases (2, 19, 20, 30). For all these methods, extraction procedures are required; these will, unquestionably, induce more lysis, thus causing overestimation of this process. The direct labeling with fluorescent dyes, as described in this paper, has great advantages since extraction procedures are not required. Furthermore, it can measure other cell characteristics in addition to the markers commonly used for lysis.

A number of fluorescence techniques for evaluating the physiological conditions of bacteria have been introduced over the last decade (for reviews see references 4, 10, and 16). Among the wide range of applications there are fluorescent dyes for measuring enzyme activities, membrane potential, redox potential, respiration activity, intracellular pH, membrane integrity, and viability of cells. Fluorescence microscopy enables direct visual analysis of labeled cell suspensions. However, FCM is often the method of choice for quantitative analysis. FCM measurements are made very rapidly on a large number of individual cells and give objective and accurate results (5, 11, 21, 24).

In the work described here, we used the fluorescent dyes of the LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit of Molecular Probes. The kit contains two fluorescent nucleic acid stains: the permeant SYTO 9 (green) and the nonpermeant PI (red) (P. Haugland, Handbook of fluorescent probes and research chemicals, 7th ed., Molecular Probes). When used in combination intact cells are labeled green and cells with damaged membranes are labeled red. The BacLight bacterial viability kit has been used for various bacterial species in pure culture, such as Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp., and Listeria spp. (11, 25, 26). Also, it has been used for bacteria in various environments, such as seawater, drinking water, biofilms, and also different food products (3, 13, 17). Recently, labeling of dairy products, including cheese curd, with the BacLight kit has been used to investigate viability of probiotic bacteria (1). Also, CSLM of BacLight-labeled cheese curd was applied to show the difference in viability between lytic and nonlytic L. lactis strains (23).

To study lytic processes, an aqueous system is preferred to facilitate extensive experimental analyses. However, lysis in a standard buffer may not represent lysis in cheese very well. In ripening cheese high concentrations of milk protein, fat globules, and salt are present, and the matrix becomes increasingly solid in time. The high osmolarity may well be an important factor in starter lysis during cheese ripening. Electron microscopy indicated this (7, 27, 29). Cells with various extents of wall lysis were observed, such as cells with protoplast membranes, which were maintained presumably by the osmotic stability in cheese, exploded protoplasts from which parts of the cell wall were released, and ghost cells whose walls were deformed. After complete lysis residual cell material remained detectable in the cheese for some time. The liberation of cytoplasmic material, including all intracellular enzymes, into cheese is commonly considered an essential step in protein degradation during production of fermented dairy products (20, 29, 30). However, Chapot-Chartier and coworkers measured a significant amount of peptide hydrolysis without detecting lysis or enzyme release (7). It was proposed that cells become permeable to enzyme substrates at the beginning of ripening and that free amino acids are released from bacterial cells. However, electron microscopy cannot visualize this initial process of cell wall and membrane permeabilization. Nevertheless, bacterial cell disruption was still considered important for facilitating access of peptide substrates and acceleration of ripening (7).

Discrimination between intact and permeable cells by fluorescent stains has been used in many studies on bacteria, including a few recent applications on lactic acid bacteria. Injury of Lactobacillus plantarum by nisin treatment was observed with PI and carboxyfluorescein succinimidylester using FCM (28). Furthermore, the membrane permeability of L. lactis was measured with PI and carboxyfluorescein diacetate (cFDA) using spectrofluorimetry and fluorescence microscopy in a study of viability after various stress treatments (6). Also, permeable fractions in post-logarithmic-phase cultures of L. lactis were measured with PI using spectrofluorimetry (22). Finally, permeabilization by bile salts and acid with concomitant cell death of various lactic acid bacteria was measured with PI, TOTO-1, and cFDA (5). The fluorescence detection of permeable cells makes it reasonable to suggest that unlysed cells with permeabilized membranes may be significant in cheese ripening. Peptides from the cheese matrix may freely diffuse inside the permeable cells and be hydrolyzed by intracellular enzymes.

The present study demonstrated the presence of permeable cells and their relevance in peptidolytic activity under cheese conditions. To mimic the stabilizing conditions that occur in cheese, we used a buffer with high protein and salt concentrations. Lysis was induced by cell wall-digesting enzyme mutanolysin. Under stabilizing conditions mutanolysin addition resulted in smaller decreases of turbidity and total number of cells than were found with control buffer. The results of the fluorescence staining suggest that the process of cell disintegration is much slower under stabilizing conditions, resulting in the presence of permeable cells for long periods of time. The release of the marker enzyme LDH was much less in the stabilizing buffer than in control buffer. This LDH release did not correspond with the permeabilization but with the decrease in total cell number, indicating that LDH is too big to leak out of these permeable cells. However, permeabilization of the cells did make the intracellular peptidase PepN accessible for the extracellular, and impermeant, peptide substrates. Apparently, the cell damage caused by mutanolysin treatment is sufficient to make cells permeable for enzyme substrates, as well as for PI, but not severe enough for leakage of enzymes.

Our results clearly show the added value of using fluorescent stains for assessment of lysis, including CSLM analysis of cheese. The fluorescence method of cell counting using SYTO 9 and PI not only monitors the complete disintegration of cells, as is the case with traditional methods of measuring lysis, but also visualizes the permeabilization of the cell envelope upon cell wall digestion by lytic enzymes. Upon permeabilization intracellular enzymes are able to contribute to the process of protein degradation and flavor formation, as is shown for PepN activity. This clearly suggests that many cells in cheese could be present in permeabilized state. Traditional lysis techniques based on measurement of released intracellular enzymes into the cheese matrix overlook the contribution to the total peptidase activity by all the enzymes present in permeabilized cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Fedde Kingma for his assistance in the lysis experiments and for helpful discussions and to Jan van Riel for performing the CSLM analysis.

Christine Bunthof was financially supported by The Netherlands Technology Foundation (STW). Saskia van Schalkwijk was financially supported by EU-RTD contract FAIR CT98 4396.

Christine Bunthof and Saskia van Schalkwijk contributed equally to this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Auty M A E, Gardiner G E, McBrearty S J, O'Sullivan E O, Mulvihill D M, Collins J K, Fitzgerald G F, Stanton C, Ross R P. Direct in situ viability assessment of bacteria in probiotic dairy products using viability staining in conjunction with confocal scanning laser microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:420–425. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.1.420-425.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bie R, Sjöström G. Autolytic properties of some lactic acid bacteria used in cheese production. Part II. Experiments with fluid substrates and cheese. Milchwissenschaft. 1975;30:739–747. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulos L, Prevost M, Barbeau B, Coallier J, Desjardins R. LIVE/DEAD BacLight: application of a new rapid staining method for direct enumeration of viable and total bacteria in drinking water. J Microbiol Methods. 1999;37:77–86. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7012(99)00048-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breeuwer P, Abee T. Assessment of viability of microorganisms employing fluorescence techniques. Int J Food Microbiol. 2000;55:193–200. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(00)00163-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bunthof C J, Bloemen K, Breeuwer P, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Flow cytometric assessment of the viability of lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:2326–2335. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.5.2326-2335.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunthof C J, van den Braak S, Breeuwer P, Rombouts F M, Abee T. Rapid fluorescence assessment of the viability of stressed Lactococcus lactis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3681–3689. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.8.3681-3689.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chapot-Chartier M P, Deniel C, Rousseau M, Vassal L, Gripon J C. Autolysis of two strains of Lactococcus lactis during cheese ripening. Int Dairy J. 1994;4:251–269. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crow V L, Coolbear T, Gopal P K, Martley F G, McKay L L, Riepe H. The role of autolysis of lactic acid bacteria in the ripening of cheese. Int Dairy J. 1995;5:855–875. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crow V L, Coolbear T, Holland R, Pritchard G G, Martley F G. Starters as finishers: starter properties relevant to cheese ripening. Int Dairy J. 1993;3:423–460. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davey H M, Kell D B. Flow cytometry and cell sorting of heterogeneous microbial populations: the importance of single-cell analyses. Microbiol Rev. 1996;60:641–696. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.4.641-696.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davey H M, Welchart D H, Kell D B, Kaprelyants A S. Estimation of microbial viability using flow cytometry. In: Robinson J P, Darzynkiewics Z, Dean P, Orfao A, Rabinovitch P, Tanke H, Wheeless L, editors. Current protocols in flow cytometry. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1999. pp. 11.3.1–11.3.20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Ruyter P G G A, Kuipers O P, Meijer W C, de Vos W M. Food-grade controlled lysis of Lactococcus lactis for accelerated cheese ripening. Nat Biotech. 1997;15:976–979. doi: 10.1038/nbt1097-976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duffy G, Sheridan J J. Viability staining in a direct count rapid method for the determination of total viable counts on processed meats. J Microbiol Methods. 1998;31:167–174. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Exterkate F A. Location of peptidases outside and inside the membrane of Streptococcus cremoris. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1984;47:177–183. doi: 10.1128/aem.47.1.177-183.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox P F, Wallace J M, Morgan S, Lynch C M, Niland E J, Tobin J. Acceleration of cheese ripening. Antonie Leeuwenhoek J Microbiol. 1996;70:271–297. doi: 10.1007/BF00395937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joux F, Lebaron P. Use of fluorescent probes to assess physiological functions of bacteria at single-cell level. Microbes Infect. 2000;2:1523–1535. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(00)01307-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Joux F, Lebaron P, Troussellier M. Succession of cellular states in a Salmonella typhimurium population during starvation in artificial seawater microcosms. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1997;22:65–76. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kunji E R S, Mierau I, Hagting A, Poolman B, Konings W N. The proteolytic systems of lactic acid bacteria. Antonie Leeuwenhoek J Microbiol. 1996;70:187–221. doi: 10.1007/BF00395933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Langsrud T, Landaas A, Castberg H B. Autolytic properties of different strains of group N streptococci. Milchwissenschaft. 1987;42:556–560. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Law B A, Sharpe M E, Reiter B. The release of intracellular dipeptidase from starter streptococci during cheddar cheese ripening. J Dairy Res. 1974;41:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lloyd D, editor. Flow cytometry in microbiology. London, United Kingdom: Springer-Verlag; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niven G W, Mulholland F. Cell membrane integrity and lysis in Lactococcus lactis: the detection of a population of permeable cells in post-logarithmic phase cultures. J Appl Microbiol. 1998;84:90–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1997.00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O'Sullivan D, Ross R P, Fitzgerald G F, Coffey A. Investigation of the relationship between lysogeny and lysis of Lactococcus lactis in cheese using prophage-targeted PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2192–2198. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.5.2192-2198.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shapiro H M. Practical flow cytometry. 3rd ed. New York, N.Y: Wiley-Liss, Inc.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suller M T E, Lloyd D. Fluorescence monitoring of antibiotic-induced bacterial damage using flow cytometry. Cytometry. 1999;35:235–241. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0320(19990301)35:3<235::aid-cyto6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swarts A J, Hastings J W, Roberts R F, von Holy A. Flow cytometry demonstrates bacteriocin-induced injury to Listeria monocytogenes. Curr Microbiol. 1998;36:266–270. doi: 10.1007/s002849900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas T D, Pritchard G G. Proteolytic enzymes of dairy starter cultures. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1987;46:245–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ueckert J E, Von Caron G N, Bos A P, Ter Steeg P F. Flow cytometric analysis of Lactobacillus plantarum to monitor lag times, cell division and injury. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1997;25:295–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1997.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Umemoto Y, Sato Y, Kito J. Direct observation of fine structures of bacteria in ripened cheddar cheese by electron microscopy. Agric Biol Chem. 1978;42:227–232. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilkinson M G, Guinee T P, Fox P F. Factors which may influence the determination of autolysis of starter bacteria during cheddar cheese ripening. Int Dairy J. 1994;4:141–160. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wittenberger C L, Angelo N. Purification and properties of a fructose-1,6-diphosphate-activated lactate dehydrogenase from Streptococcus faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:717–724. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.3.717-724.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]