Abstract

A multicopper oxidase gene, cumA, required for Mn(II) oxidation was recently identified in Pseudomonas putida strain GB-1. In the present study, degenerate primers based on the putative copper-binding regions of the cumA gene product were used to PCR amplify cumA gene sequences from a variety of Pseudomonas strains, including both Mn(II)-oxidizing and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. The presence of highly conserved cumA gene sequences in several apparently non-Mn(II)-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains suggests that this gene may not be expressed, may not be sufficient alone to confer the ability to oxidize Mn(II), or may have an alternative function in these organisms. Phylogenetic analysis of both CumA and 16S rRNA sequences revealed similar topologies between the respective trees, including the presence of several distinct phylogenetic clusters. Overall, our results indicate that both the cumA gene and the capacity to oxidize Mn(II) occur in phylogenetically diverse Pseudomonas strains.

Most of the manganese(II) oxidation which occurs in the environment is bacterially mediated (20, 26), yet the diversity of organisms responsible for this activity and the underlying mechanisms of catalysis are poorly understood. Over the years, Pseudomonas strains capable of oxidizing Mn(II) have been isolated from a wide variety of environments, including soils, freshwater, seawater, water pipes, and even manganese nodules (12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 18, 24). However, to date, the only well-characterized Mn(II)-oxidizing organisms within this genus are the closely related strains Pseudomonas putida MnB1 and GB-1. Due to the ubiquity of P. putida in the environment and the ease with which it can be grown, these strains have provided an excellent model system for studying bacterial Mn(II) oxidation.

Upon reaching stationary phase, P. putida strains MnB1 and GB-1 oxidize Mn(II) to Mn(III, IV) oxides which are precipitated on the cell surface, eventually encrusting the organism. Previous studies suggested that MnB1 produces a soluble intracellular Mn(II)-oxidizing protein in late logarithmic and early stationary phase (8, 18). More recent biochemical studies with GB-1 resulted in the partial purification and characterization of two Mn(II)-oxidizing factors with estimated molecular masses of 180 and 250 kDa (21). The Mn(II)-oxidizing activity of these factors, which are believed to be multiprotein complexes, is inhibited by the redox enzyme inhibitor azide as well as metal chelators, suggesting the involvement of a metal cofactor.

In order to identify genes involved in Mn(II) oxidation, transposon mutagenesis was used in P. putida strains MnB1 and GB-1 (6, 11) to generate mutants which no longer oxidize Mn(II). In both studies, genes involved in the biogenesis and maturation of c-type cytochromes were found to be involved in Mn(II) oxidation. However, cytochromes alone are not believed to be sufficient for catalyzing this reaction. More recently, a gene encoding a multicopper oxidase, designated cumA, was reported to be essential for Mn(II) oxidation in GB-1 (4). This finding is consistent with the fact that multicopper oxidases have also been shown to be involved in Mn(II) oxidation in two other phylogenetically distinct organisms, the marine Bacillus sp. strain SG-1 (28) and the freshwater organism Leptothrix discophora SS-1 (7). In addition, small amounts of copper have been shown to enhance the rates of Mn(II) oxidation by all three organisms (4, 5, 28). Thus, cumA has been suggested to encode a Cu-dependent oxidase which is directly involved in Mn(II) oxidation.

The objective of this study was to assess the distribution and diversity of cumA multicopper oxidase genes within the genus Pseudomonas. In particular, a wide variety of Pseudomonas strains were screened both for their ability to oxidize Mn(II) and for the presence of the cumA gene. Phylogenetic analyses of CumA and 16S rRNA sequences from both Mn(II)-oxidizing and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains were used to determine how widespread the ability to oxidize Mn(II) is within this environmentally important genus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and Mn(II) oxidation assays.

The bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Various non-Mn(II)-oxidizing transposon mutants of P. putida strains MnB1 and GB-1 were tested for ABTS [2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid)] oxidation (see below), including MnB1 mutants UT302, UT402, and UT403 (6) and GB-1 mutants GB-1-003, GB-1-004, GB-1-005, and GB-1-007 (11). Strains were maintained on L. discophora medium (2) containing 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.5) and 100 μM MnCl2. The ability to oxidize Mn(II) was monitored by the formation of brown colonies on plates or visible Mn oxide formation in liquid cultures. The presence of Mn oxides was confirmed using the colorimetric dye leucoberbelin blue (19).

TABLE 1.

Mn(II)-oxidizing and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains used in this study

| Organism | Strain | Origin [for new Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates] | Mn(II) oxidationa | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas sp. | GB13 | Sediments, Green Bay, Wis. | + | L. Stein |

| Pseudomonas sp. | GP11 | Pulpmill Effluent, Grande Prairie, Alberta, Canada | +++ | This study |

| Pseudomonas sp. | ISO1 | Metallogenium particles from Horsetooth Reservoir, Fort Collins, Colo. | + | L. Stein |

| Pseudomonas sp. | ISO6 | Metallogenium particles from Horsetooth Reservoir, Fort Collins, Colo. | ++ | L. Stein |

| Pseudomonas sp. | MG1 | Metallogenium particles from Horsetooth Reservoir, Fort Collins, Colo. | + | L. Stein |

| Pseudomonas sp. | PCP | Pinal Creek sediments, Globe, Ariz. | +++ | This study |

| Pseudomonas sp. | PCP2 | Pinal Creek sediments, Globe, Ariz. | +++ | B. Clement |

| Pseudomonas sp. | SI85-2B | Oxic-anoxic interface, Saanich Inlet, British Columbia, Canada | +++ | This study |

| P. putida | GB-1 | +++ | J. P. de Vrind | |

| P. putida MnB1 | ATCC 23483 | +++ | ATCCb | |

| P. putida | ATCC 12633 | + | ATCC | |

| P. putida mt-2 | ATCC 33015 | + | ATCC | |

| P. chlororaphis | ATCC 9446 | + | ATCC | |

| P. aeruginosa | ATCC 15692 | − | ATCC | |

| P. aureofaciens | ATCC 13985 | − | ATCC | |

| P. denitrificans | ATCC 13867 | − | ATCC | |

| P. fluorescens | ATCC 13525 | − | ATCC | |

| P. stutzeri | JM300 | − | B. Ward | |

| P. syringae pv. Tomato | PT23 | − | D. Cooksey | |

| Pseudomonas sp. | ADP | − | D. Crowley |

Relative intensity of Mn(II) oxidation after 10 days of growth on plates: −, negative; +, weak; ++, moderate; +++, strong. Colonies of weak oxidizers are generally light brown or only partially encrusted with rings of brown Mn oxides. Strong oxidizers produce uniformly dark brown colonies. Colonies of moderate oxidizers accumulate Mn oxides to an intermediate extent relative to weak and strong oxidizers. All Mn(II)-oxidizing colonies react strongly with leucoberbelin blue.

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection.

DNA extraction, PCR, cloning, and sequencing.

DNA was extracted from cells using the QIAamp DNA extraction kit (Qiagen). The initial set of PCR primers was designed based on the determinants of the two copper-binding regions of the P. putida GB-1 cumA gene that are farthest apart, and the sequences were as follows: CumAF, 5′-ATCCATTGGCACGGCATCCGC-3′; and CumARdg, 5′-TCCATRTGRTCRATSACRTGRCARTG-3′. Several internal primers were subsequently designed to amplify cumA from additional Pseudomonas strains and had the following sequences: CumAIdgFB, 5′-TBGADATGGAYGGCGTGCC-3′; CumAIdgR2, 5′-TCGTTCTTGCCSARCARRTASGTRTCGGTGAA-3′; CumAIdg2B, 5′-GAYGCCGGYAGCTACTGGTAYCACCC-3′; and CumAIdgR, 5′-ACYTTGAARSYCATGCCRTGCARRTG-3′. The PCR program for cumA amplification was 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 45°C for 30 s, and 60°C for 1 min, using Taq polymerase (Roche). PCR products were cloned using a TOPO-TA cloning kit (Invitrogen), and both strands were sequenced using an ABI 373A automated sequencer. 16 rRNA genes were amplified with 27F and 1492R primers (29) in a standard 30-cycle PCR, and both strands were sequenced directly.

Phylogenetic analysis.

16S rRNA sequences were aligned manually in Sequencher 3.1 and compared to alignments generated using CLUSTALW and the Ribosomal Database Project Sequence Aligner, and both gaps and ambiguously aligned regions were removed. Phylogenetic trees were generated by neighbor joining, using Jukes-Cantor corrected distances, or by maximum parsimony within the PAUP (version 4.0b3) software package. Derived CumA amino acid sequences were aligned using CLUSTALW, and phylogenetic trees were constructed using neighbor-joining and parsimony methods within PAUP. Bootstrap analysis was used to estimate the reliability of phylogenetic reconstructions (1,000 replicates). The accession numbers of the 16S rRNA sequences used for comparison are as follows: P. aeruginosa, Z76651; P. chlororaphis, D86004; P. fluorescens, D86001; P. putida ATCC 12633, AF094736; P. putida mt-2, D37924; P. putida MnB1, U70977; and P. stutzeri JM300, X98607. The accession numbers for the cumA sequences of P. putida GB-1 and P. aeruginosa PAO1 are AF086638 and AE004795, respectively.

Southern blot analysis.

Chromosomal DNAs (≈5 μg) from various strains were digested with restriction enzymes, separated by gel electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels, and transferred to nylon membranes. Digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes were generated by using the DIG High Prime (Roche) random-priming kit to label cumA PCR products obtained from P. putida MnB1 and P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692. DNA was bound to the membranes by UV irradiation, hybridized overnight with DIG-labeled probe at 55°C, and washed in 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate)–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 1× SSC–0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate at the same temperature, essentially by the method of Sambrook et al. (22). Bound probe was detected using the chemiluminescent substrate CDP-star (Roche), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

ABTS oxidation.

To assay strains for laccase-like activity, ABTS, a chromogenic substrate used for measuring laccase and peroxidase activities, was added to L. discophora medium without Mn(II) to a final concentration of 1 mM. The oxidation of this substrate resulted in the formation of a greenish-purple color on plates.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rRNA sequences of the Pseudomonas strains determined in the present study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers AF326374 to AF326383. The 15 new cumA gene sequences have been deposited under accession numbers AF326398 to AF326412.

RESULTS

Diversity of organisms capable of Mn(II) oxidation.

In addition to the model Mn(II)-oxidizing strains, P. putida GB-1 and MnB1, several well-characterized P. putida strains (ATCC 12633 and ATCC 33015) were also found to be capable of oxidizing Mn(II), although to a lesser extent. Also, despite having been previously placed into separate biovars (8) and in several cases having distinct colony morphologies and Mn(II)-oxidizing properties, several of Schweissfurth's isolates (MnB6, 11, 14, 18, and 104) (18) had 16S rRNA sequences identical to that of MnB1. The finding that a variety of P. putida strains were capable of oxidizing Mn(II) is consistent with previous studies by DePalma (8) suggesting that P. putida may be an important species involved in Mn(II) oxidation in the environment. The 16S rRNA sequence of the atrazine-degrading organism Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP (10) was fairly closely related (≈98.5% identity) to those of some of these P. putida strains, but this organism did not oxidize Mn(II) on solid or liquid media.

A number of other environmentally important and well-characterized Pseudomonas species also did not appear to have the capacity to oxidize Mn(II), including P. fluorescens ATCC 13525, P. syringae pv. Tomato PT23, P. stutzeri JM300, P. aureofaciens ATCC 13985, and P. denitrificans ATCC 13867. Although P. aeruginosa ATCC 15692 did not oxidize Mn(II) under our experimental conditions, Brouwers et al. (4) reported that logarithmic-phase cultures of another P. aeruginosa strain, PAO1, could oxidize Mn(II) “in principle” but not reproducibly. The only other previously known species tested which oxidized Mn(II) to any extent was P. chlororaphis (ATCC 9446).

Phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA genes obtained from a number of new Mn(II)-oxidizing strains (GB13, GP11, ISO1, ISO6, MG1, PCP, PCP2, and SI85-2B) isolated from a variety of environments (Table 1) revealed that the capacity to oxidize Mn(II) is not restricted only to close relatives of P. putida but actually appears to be quite widespread within the genus Pseudomonas. Most of the Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates are very closely related (>99.5% identity) to other Pseudomonas sequences in the databases (Ribosomal Database Project and GenBank), suggesting that these organisms may be members of the same species and also have the capacity to oxidize Mn(II). In particular, the Mn(II)-oxidizing strains GB13, ISO6 (and PCP), GP11, and MG1 (and ISO1) are most closely related to P. mandelii (accession number AF058286), P. putida ATCC 17484 (biovar B) (D85993), P. alcalophila (AB030583), and P. migulae (AF074383), respectively. The two other Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates, SI85-2B and PCP2, were more distantly related to other Pseudomonas sequences in the databases, sharing only ≈97% identity with 16S rRNA sequences of P. flavescens (U01916) and P. resinovorans (AB021373), respectively.

Amplification and sequence analysis of cumA genes.

The initial sets of PCR primers for amplification of cumA sequences were designed based on the determinants of two of the putative copper-binding regions (IHWHGI and HCHVIDHME) of the deduced CumA amino acid sequence of GB-1, since these residues would be expected to be highly conserved due to their functional role. Although several primers were designed based on these regions with various degrees of degeneracy, the most effective primer combination was a nondegenerate forward primer (CumAF) and a degenerate reverse primer (CumARdg). These primers were used to successfully amplify cumA products of the expected size (≈1,056 bp) from 10 different Pseudomonas strains. Based on conserved regions of the 12 existing sequences (including P. putida GB-1 and P. aeruginosa PAO1), several additional internal primers were designed and used to amplify smaller (≈954- or ≈810-bp) regions of cumA from five additional strains which did not amplify with the other primers. Strain PCP2 was the only Mn(II)-oxidizing isolate for which no specific amplification occurred with any of the primer combinations. However, Southern blot analysis with a DIG-labeled cumA probe demonstrated the presence of a hybridizing band (data not shown).

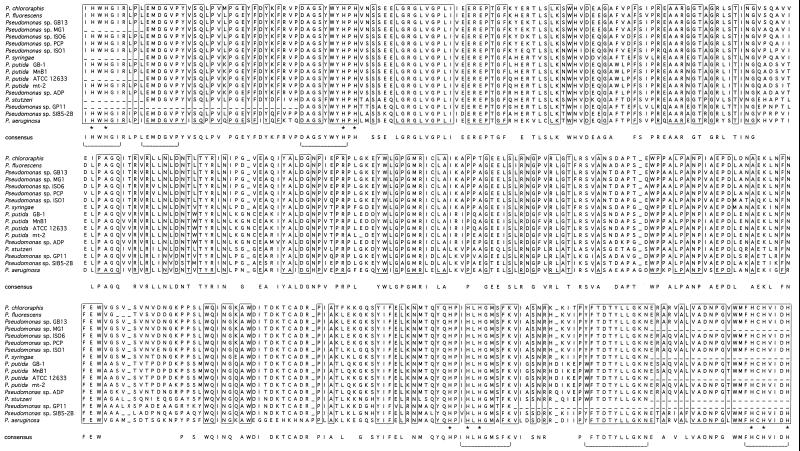

Sequence analysis revealed that the cumA sequences ranged from 67 to 100% identical (at the DNA level) to the P. putida GB-1 sequence. The deduced CumA amino acid sequences also ranged from 67 to 100% identical, while the similarities ranged from 81 to 100%, as expected from the translation of “wobble” codons into amino acid residues. The most divergent sequence was that of P. aeruginosa PAO1, whereas identical sequences were identified in P. putida MnB1 as well as the closely related strains MnB6, 11, 14, 18, and 104 (data not shown). Alignment of the 17 derived CumA amino acid sequences (Fig. 1) revealed that certain regions of the protein were extremely highly conserved. As expected, the copper-binding regions were highly conserved, but in addition, over 43% of the total amino acid residues were identical in all 17 sequences (>50% if P. aeruginosa PAO1 is excluded from the comparison).

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the derived amino acid sequences from 17 cumA genes. Boxed residues are conserved across all 17 protein sequences. The consensus represents residues present in at least 80% (14 out of 17) of the sequences. Conserved histidine residues within the putative copper-binding regions are highlighted by asterisks. Horizontal brackets correspond to the conserved regions targeted by our PCR primers.

Phylogenetic analysis of CumA sequences.

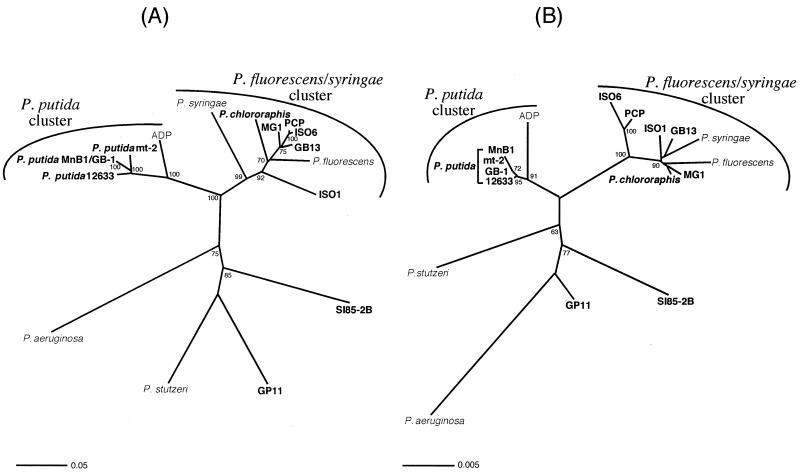

Phylogenetic trees based on all 17 CumA amino acid sequences revealed the presence of several distinct phylogenetic clusters (Fig. 2A). These included a P. putida cluster, a P. fluorescens-P. syringae cluster, and a group of four more divergent sequences [P. stutzeri, P. aeruginosa, and the Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates SI85-2B and GP11]. CumA sequences from five non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains were spread throughout the phylogenetic tree. Relative to the CumA sequence of P. putida GB-1, sequences within the P. putida cluster shared an average of 97% identity and 98% similarity, those within the P. fluorescens-P. syringae cluster shared 81% identity and 88% similarity, and those within the third group shared 69% identity and 82% similarity. The four P. putida strains formed a tight cluster, while the ADP sequence was slightly more divergent (91% identity and 93% similarity to GB-1). Five of the Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates fell within the P. fluorescens-P. syringae cluster, but only one of these organisms, strain PCP, would be classified as a strong Mn(II) oxidizer. Strain ISO6, despite having a CumA sequence identical to that of PCP, is a relatively weak to moderate oxidizer, oxidizing Mn(II) only when streaked down into the agar, which suggests a preference for microaerobic conditions for Mn(II) oxidation. When streaked in this same manner, PCP initially oxidizes within the agar but eventually oxidizes uniformly on the surface of the plate as well. The other three Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates within this cluster (MG1, GB13, and ISO1), as well as P. chlororaphis, can all be classified as weak oxidizers, while P. fluorescens is a nonoxidizer. P. syringae, which also is incapable of Mn(II) oxidation, appears to have a CumA sequence somewhat distinct from those of the other members of the P. fluorescens-P. syringae cluster but, overall, clearly groups with this cluster (99% bootstrap value). The third group is composed of four distantly related sequences, with SI85-2B and P. aeruginosa clustering more closely with the other two distantly related phylogenetic clusters than with P. stutzeri or GP11.

FIG. 2.

Unrooted neighbor-joining trees based on partial CumA amino acid sequences (A) and 16S rRNA sequences (B) from 17 Pseudomonas strains, including Mn(II)-oxidizing strains (in boldface) and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. Bootstrap values (>60%) are indicated at the supported nodes. Scale bars correspond to the number of mutations per sequence position.

For comparative purposes, a 16S rRNA phylogenetic tree was generated for the same 17 organisms from which CumA sequences were obtained (Fig. 2B). The overall topologies of the 16S rRNA and CumA phylogenetic trees are quite similar (Fig. 2), in that there are essentially two tight phylogenetic clusters and a group of more divergent sequences only distantly related to one another. One obvious difference, however, is that at the 16S rRNA level the PCP-ISO6 clade is less tightly associated with the P. fluorescens-P. syringae cluster, which is interesting since PCP and ISO6 are stronger oxidizers than the other Mn(II)-oxidizing strains within this overall cluster. The relationship between the four P. putida strains and strain ADP is also quite similar at the 16S rRNA level, with ADP being somewhat distinct from the tight cluster of P. putida strains. This distinction may reflect different physiological properties of strain ADP relative to other P. putida strains, such as the unique ability to degrade atrazine (10) as well as the inability to oxidize Mn(II). Finally, the relative relationships of P. stutzeri, SI85-2B, GP11, and P. aeruginosa appear to differ somewhat at the 16S rRNA level, with P. stutzeri and P. aeruginosa essentially swapping phylogenetic positions relative to the CumA tree. At the 16S rRNA level, strain PCP2 clusters more closely with P. aeruginosa than do any of the other Mn(II) oxidizers (data not shown), suggesting that this strain might also fall in a similar position within a CumA tree.

Alternative organic substrates for Mn(II)-oxidizing organisms.

Since all known multicopper oxidases are capable of oxidizing organic substrates (25) and CumA shares significant sequence similarity with fungal laccases (1, 27) in particular, both Mn(II)-oxidizing and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains were tested for the capacity to directly oxidize the synthetic laccase substrate ABTS. All of the strong Mn(II) oxidizers (P. putida MnB1 and GB-1, PCP, PCP2, GP11, and SI85-2B) oxidized the substrate to various extents, resulting in the formation of a greenish-purple color on plates. However, none of the weakly oxidizing or nonoxidizing strains visibly oxidized the substrate. To further assess whether this activity was directly related to the ability to oxidize Mn(II), several non-Mn(II)-oxidizing transposon mutants of P. putida MnB1 and GB-1 (6, 11), which were incapable of forming active Mn(II)-oxidizing complexes, were tested for ABTS oxidation (Fig. 3). None of these mutants, including a cumA mutant and various ccm mutants, were able to oxidize ABTS, indicating a link between the Mn(II) oxidase and the oxidation of organic compounds.

FIG. 3.

P. putida MnB1 and a non-Mn(II)-oxidizing MnB1 mutant streaked on plates containing Mn(II) (top) or ABTS (bottom). Mn(II) oxidation results in the formation of brown Mn oxides on colonies, while ABTS oxidation results in the formation of a diffusible purplish-green product. The mutant is incapable of oxidizing both substrates and remains opaque on plates.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study clearly indicate that the ability to oxidize Mn(II) is widespread within the genus Pseudomonas. In addition, the multicopper oxidase gene, cumA, appears to be widely distributed within the genus Pseudomonas, occurring in both Mn(II)-oxidizing and non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. The similarity between the topologies of the CumA and 16S rRNA trees (Fig. 2) suggests that it is unlikely that the cumA gene has recently been horizontally transferred throughout the genus Pseudomonas. Instead, it appears that the cumA gene may be an evolutionarily and functionally important gene in these organisms.

Although the overall phylogenetic clusters are quite similar in the CumA and 16S rRNA trees, as with many functional genes, the phylogeny based on the cumA gene product may provide higher resolution than that based on the 16S rRNA gene. For example, the relative phylogenetic placement of the Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates PCP and ISO6, which group tightly within the core of the P. fluorescens-P. syringae cluster at the CumA level, is more distant from this cluster at the 16S rRNA level. An explanation for this stems from the fact that the 16S rRNA sequences of strains PCP and ISO6 are almost identical to that of P. putida ATCC 17484 (biovar B), a strain reported to be more phenotypically similar to P. fluorescens than to classical P. putida (biovar A) strains (30). Our results are similar to those of Yamamoto and Harayama (30), who found that strain ATCC 17484 clustered more closely with P. fluorescens than with P. putida (biovar A) strains based on gyrB and rpoD sequences.

The presence of cumA gene sequences in various non-Mn(II)-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains has a number of interpretations. One possibility is that the cumA gene product is functionally inactive in the non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. However, this seems rather unlikely considering how highly conserved this gene is in several of these organisms (e.g., strain ADP and P. fluorescens, etc.). The conservation of structural motifs (e.g., copper-binding regions) also suggests that these genes did not arise from duplications or related genes. Pseudogenes or nonfunctioning genes are under no selective pressure and thus would not be expected to maintain the structural elements needed for a functional protein (23).

Since the Mn(II)-oxidizing factors isolated from P. putida GB-1 are believed to be multiprotein complexes (21), CumA may have to be directly associated with other proteins to have activity. Thus, it is possible that the cumA gene sequences from the non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains encode functional proteins but that some other essential component of the complex is missing or inactive. Since N-terminal signal peptides and a two-step protein secretion pathway have been implicated as being important in localizing the Mn(II)-oxidizing complex to the cell surface (3, 4), perhaps these features are different or absent in the non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. Alternatively, it is possible that the non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains do in fact possess the genetic potential to oxidize Mn(II) but that they do so under different conditions (e.g., nutrient availability, Eh, O2 level, or metal concentration, etc.) than the other known Mn(II)-oxidizing pseudomonads.

Finally, it is possible that the cumA gene product has a different or alternative function in the non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. In particular, the sequence similarity to fungal laccases suggested that, like all other known multicopper oxidases (25), CumA could be involved in the oxidation of organic substrates. However, what was found was that only Mn(II)-oxidizing Pseudomonas strains were capable of oxidizing the synthetic laccase substrate ABTS. This is interesting in light of the fact that a fungal laccase was recently reported to directly oxidize Mn(II) to Mn(III) in the presence of the complexing agent Na-pyrophosphate (17), while the Fe(II)-oxidizing multicopper oxidase FET3 (from yeast) also has the capacity to oxidize certain organic compounds like p-phenylenediamine (Km = 900 μM) but has a much higher affinity for Fe(II) (Km = 2 μM) (9). Thus, a scenario analogous to that of the ferroxidase might be envisioned, in which the metal is the primary substrate for CumA while the organic is a secondary, lower-specificity substrate. A direct link between Mn(II)-oxidizing activity and ABTS oxidation was substantiated by the fact that non-Mn(II)-oxidizing transposon mutants of P. putida MnB1 and GB-1, which are incapable of forming active Mn(II)-oxidizing complexes, were also incapable of ABTS oxidation. Although an alternative function for cumA from non-Mn(II)-oxidizing strains was not identified through these experiments, the range of potential substrates, activities, and functions of Mn(II)-oxidizing enzymes has been expanded. Further studies of purified Mn(II)-oxidizing proteins should reveal the relative affinities and specificities of these enzymes for metals and organic substrates.

Caution should be exercised if the cumA gene is used as a functional gene probe for Mn(II) oxidation potential in the environment, since highly conserved cumA sequences are present in a wide variety of phylogenetically diverse Pseudomonas strains, including strains that are apparently incapable of Mn(II) oxidation. The primers used in this study were designed to amplify cumA sequences from as many strains as possible and thus would not be appropriate for specifically detecting cumA from Mn(II)-oxidizing strains. However, it should now be possible to design a suite of gene probes or PCR primers specific for cumA in Mn(II)-oxidizing pseudomonads, based on the cumA sequences of the Mn(II)-oxidizing strains in this study. Linking the presence of Mn(II) oxidation-associated multicopper oxidase genes (e.g., cumA, mnxG, and mofA) with bacterial Mn(II) oxidation in the environment will be essential for establishing the importance of these Cu-dependent enzymes in nature.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Lisa Stein for generously providing several Mn(II)-oxidizing isolates (MG1, ISO1, ISO6, and GB13), Brian Clement for providing strain PCP2, and Hans de Vrind and Liesbeth de Vrind-de Jong for providing the P. putida GB-1 mutants. We also thank Margo Haygood and Rebecca Verity for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This research was funded in part by the National Science Foundation (grants MCB-9808915 and CHE-0089208) and the Collaborative UC/Los Alamos Research (CULAR) Program. C.A.F. was supported in part by a STAR Graduate Fellowship from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the University of California Toxic Substances Research and Training Program.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archibald F S, Roy B. Production of manganic chelates by laccase from the lignin-degrading fungus Trametes (Coriolus) versicolor. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:1496–1499. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.5.1496-1499.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boogerd R C, de Vrind J P M. Manganese oxidation by Leptothrix discophora SS-1. J Bacteriol. 1987;169:489–494. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.2.489-494.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brouwers G J, de Vrind J P M, Corstjens P L A M, de Vrind-de Jong E W. Genes of the two-step protein secretion pathway are involved in the transport of the manganese-oxidizing factor across the outer membrane of Pseudomonas putida GB-1. Am Mineral. 1998;83:1573–1582. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brouwers G J, de Vrind J P M, Corstjens P L A M, Cornelis P, Baysse C C, de Vrind-de Jong E W. cumA, a gene encoding a multicopper oxidase, is involved in Mn2+ oxidation in Pseudomonas putida GB-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1762–1768. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1762-1768.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brouwers G J, Corstjens P L A M, de Vrind J P M, Verkamman A, de Kuyper M, de Vrind-de Jong E W. Stimulation of Mn2+-oxidation in Leptothrix discophora SS-1 by Cu(II) and sequence analysis of the region flanking the gene encoding putative multicopper oxidase MofA. Geomicrobiol J. 2000;17:25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caspi R, Haygood M G, Tebo B M. c-type cytochromes and manganese oxidation in Pseudomonas putida MnB1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3549–3555. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3549-3555.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corstjens P L A M, de Vrind J P M, Goosen T, de Vrind-de Jong E W. Identification and molecular analysis of the Leptothrix discophora SS-1 mofA gene, a gene putatively encoding a manganese-oxidizing protein with copper domains. Geomicrobiol J. 1997;14:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.DePalma S R. Manganese oxidation by Pseudomonas putida. Ph.D. thesis. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Silva D, Davis-Kaplan S, Fergestad J, Kaplan J. Purification and characterization of Fet3 protein, a yeast homologue of ceruloplasmin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14208–14213. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza M L, Wackett L P, Boundy-Mills K L, Mandelbaum R T, Sadowsky M J. Cloning, characterization, and expression of a gene region from Pseudomonas sp. strain ADP involved in the dechlorination of atrazine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3373–3378. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3373-3378.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.de Vrind J P M, Brouwers G J, Corstjens P L A M, den Dulk J, de Vrind-de Jong E W. The cytochrome c maturation operon is involved in manganese oxidation in Pseudomonas putida GB-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3556–3562. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3556-3562.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douka C. Study of the bacteria from manganese concretions. Soil Biol Biochem. 1977;9:89–97. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Douka C. Kinetics of manganese oxidation by cell-free extracts of bacteria isolated from manganese concretions from soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1980;39:74–80. doi: 10.1128/aem.39.1.74-80.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehrlich H L. Bacteriology of manganese nodules. II. Manganese oxidation by cell-free extract from a manganese nodule bacterium. Appl Microbiol. 1968;16:197–202. doi: 10.1128/am.16.2.197-202.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiorse W C. Biology of iron- and manganese-depositing bacteria. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1984;38:515–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.002503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gregory E, Staley J T. Widespread ability to oxidize manganese among freshwater bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:509–511. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.2.509-511.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hofer C, Schlosser D. Novel enzymatic oxidation of Mn2+ to Mn3+ catalyzed by a fungal laccase. FEBS Lett. 1999;451:186–190. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00566-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung W E, Schweissfurth R. Manganese oxidation by an intracellular protein of a Pseudomonas species. Z Allg Mikrobiol. 1979;19:107–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krumbein W E, Altman H J. A new method for detection and enumeration of manganese-oxidizing and -reducing microorganisms. Helgol Wiss Meeresunters. 1973;25:347–356. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nealson K H, Tebo B M, Rosson R A. Occurrence and mechanisms of microbial oxidation of manganese. Adv Appl Microbiol. 1988;33:279–318. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okazaki M, Sugita T, Shimizu M, Ohode Y, Iwamoto K, de Vrind-de Jong E W, de Vrind J P M, Corstjens P L A M. Partial purification and characterization of manganese-oxidizing factors of Pseudomonas fluorescens GB-1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4793–4799. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4793-4799.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scala D J, Kerkhof L J. Diversity of nitrous oxide reductase (nosZ) genes in continental shelf sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:1681–1687. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.4.1681-1687.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schutt C, Ottow J C. Distribution and identification of manganese-precipitating bacteria from noncontaminated ferromanganese nodules. In: Krumbein W E, editor. Environmental biogeochemistry and geomicrobiology: methods, metals and assessment. Ann Arbor, Mich: Ann Arbor Science; 1978. pp. 869–878. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Solomon E I, Sundaram U M, Machonkin T E. Multicopper oxidases and oxygenases. Chem Rev. 1996;96:2563–2605. doi: 10.1021/cr950046o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tebo B M, Ghiorse W C, van Waasbergen L G, Siering P L, Caspi R. Bacterially-mediated mineral formation: insights into manganese(II) oxidation from molecular genetic and biochemical studies. Rev Mineral. 1997;35:225–266. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thurston C F. The structure and function of fungal laccases. Microbiology. 1994;140:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Waasbergen L G, Hildebrand M, Tebo B M. Identification and characterization of a gene cluster involved in manganese oxidation by spores of the marine Bacillus sp. strain SG-1. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:3517–3530. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.12.3517-3530.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto S, Harayama S. Phylogenetic relationship of Pseudomonas putida strains deduced from the nucleotide sequences of gyrB, rpoD, and 16S rRNA genes. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1998;48:813–819. doi: 10.1099/00207713-48-3-813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]