Abstract

Nocardiopsis strains were isolated from water-damaged indoor environments. Two strains (N. alba subsp. alba 704a and a strain representing a novel species, ES10.1) as well as strains of N. prasina, N. lucentensis, and N. tropica produced methanol-soluble toxins that paralyzed the motility of boar spermatozoa at <30 μg of crude extract (dry weight) ml−1. N. prasina, N. lucentensis, N. tropica, and strain ES10.1 caused cessation of motility by dissipating the mitochondrial membrane potential, Δψ, of the boar spermatozoa. Indoor strain 704a produced a substance that destroyed cell membrane barrier function and depleted the sperm cells of ATP. Indoor strain 64/93 was antagonistic towards Corynebacterium renale. Two indoor Nocardiopsis strains were xerotolerant, and all five utilized a wide range of substrates. This combined with the production of toxic substances suggests good survival and potential hazard to human health in water-damaged indoor environments. Two new species, Nocardiopsis exhalans sp. nov. (ES10.1T) and Nocardiopsis umidischolae sp. nov. (66/93T), are proposed based on morphology, chemotaxonomic and physiological characters, phylogenetic analysis, and DNA-DNA reassociations.

Water-damaged indoor building materials are frequently colonized by complex microbial communities and may emit mixed bioaerosols into the indoor air (4, 6, 20, 49). Many studies have been carried out with the aim of revealing which microbial agents are responsible for causing the development of the ill health symptoms associated with damp houses (17, 21, 26, 47, 50). Mycotoxins, lipopolysaccharides of gram-negative bacteria, β-d-glucans, and cytotoxic metabolites produced by Streptomyces have been suspected to have adverse health effects (5, 21, 40, 47).

The guidelines of the Finnish Health Authority state that the presence of spore-forming actinobacteria in indoor environments may indicate a risk to human health (8) but do not specify any genera or species. Nocardiopsis dassonvillei has been isolated from lung biopsies of farmers suffering from alveolitis (36). This species is classified as hazard category 2 in European legislation (7). Strains of the actinobacterial genus Nocardiopsis have also been reported to produce antimicrobial and bioactive agents (e.g., a cytotoxic antifungal antibiotic, kalafungin [55]; antibacterial 3-trehalosamine [16], an inhibitor of protein kinase C, methylpendolmycin [52]; and a staurosporin-like inhibitor of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase enzyme [23]). Nocardiopsis species have been observed in indoor environments (6, 42), and a bioactive agent-producing isolate was recently reported (42).

Here, we report on five Nocardiopsis isolates from water-damaged indoor environments, of which two (N. alba subsp. alba 704a and an isolate representing a novel species, ES10.1) produced toxins, which were detected by using boar spermatozoa as test cells. Also N. lucentensis, N. prasina, and N. tropica were shown to produce substances toxic to boar spermatozoa. N. prasina, N. lucentensis, N. tropica, and the isolate ES10.1 dissipated the mitochondrial membrane potential (Δψ), and thus were mitochondriotoxic, whereas isolate 704a produced a substance that destroyed the cell membrane barrier function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

Samples of indoor air, dust, and construction materials of water-damaged buildings were sources for isolating the actinobacterial strains. The air of indoor environments was sampled by using a six-stage Andersen sampler (28.3 liters/min; Graseby Andersen, Atlanta, Ga.) supplied with tryptic soy agar (TSA) plates (Difco, Detroit, Mich.). Plates were incubated at 15°C for 14 days. Bacterial strains were isolated from dust and construction materials as described previously (4, 6). The isolates and reference strains used in this study are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Nocardiopsis isolates and reference strains used in this study

| Strain designation | Strain codea | Origina | 16S rDNA sequence accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor isolate | ES 10.1 | Indoor air of a private dwelling | AY028325 |

| DSM 44407T | |||

| Indoor isolate | 66/93 | Indoor dust of a water-damaged school | AY036001 |

| DSM 44362T | |||

| Indoor isolate | 64/93 | Indoor dust of a water-damaged school | AY036004 |

| Indoor isolate | 123 | Water-damaged gypsum liner from children's day care centerb | AY036002 |

| Indoor isolate | 704a | Indoor air of a cattle barnb | AY036003 |

| Nocardiopsis listeri | DSM 40297T | Human clinical isolate | X97887 |

| Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. albirubida | DSM 40465T | X97882 | |

| Nocardiopsis dassonvillei | DSM 43111T | Mildewed grain and fodder | X97886 |

| Nocardiopsis dassonvillei | DSM 43884 | Ice sheet of the central antarctic glacier | X97885 |

| Nocardiopsis alba subsp. alba | DSM 43377T | Drainage from hip | X97883 |

| Nocardiopsis prasina | DSM 43845T | Soil | X97884 |

| Nocardiopsis synnemataformans | DSM 44143T | Sputum | Y13593 |

| Nocardiopsis lucentensis | DSM 44048T | Salt marsh soil | X97888 |

| Nocardiopsis trehalosi | VKM Ac-942T | AF105972 | |

| DSM 44380T | |||

| Nocardiopsis tropica | VKM Ac-1457T | Soil | AF105971 |

| DSM 44381T | |||

| Saccharothrix coeruleofusca | DSM 43679T | Soil | NAc |

| Corynebacterium renale | DSM 20688T | NA | |

| Micrococcus luteus | DSM 20030T | NA |

DSM strains were obtained from German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures, Braunschweig, Germany.

Andersson et al. (5).

NA, not applicable.

Analysis of toxicity.

The bacterial biomass of indoor isolates and reference strains analyzed for toxicity was grown on TSA plates at 28°C for 10 days, harvested, frozen and thawed, and then extracted into methanol. Methanol was evaporated, and the residue was weighed and dissolved into a known volume of methanol. A boar spermatozoan motility inhibition assay was performed as described by Andersson et al. (4), but judged by phase-contrast microscope. Boar spermatozoa were obtained from commercial sources (AI Cooperative, Kaarina, Finland) and were used as delivered for insemination of farm animals.

ATP content of the boar spermatozoa was measured as described by Juonala et al. (30). Damage to the spermatozoan plasma membrane permeability barrier was assayed in terms of stainability by propidium iodide (PI) as described by Juonala et al. (31) or by differential staining with PI and SYBR-14 as described by Peltola et al. (42). Reduction of resazurin by the spermatozoa was assayed fluorometrically (1). The dissipation of boar sperm cell mitochondrial Δψ by methanol extracts was determined by selective staining with JC-1 as described by Peltola et al. (42).

The agar diffusion assay was performed with filter paper disks impregnated with extracts dissolved in methanol prepared from the cultures of Nocardiopsis species with Corynebacterium renale DSM 20688T (13) and Micrococcus luteus DSM 20030T (43) as the indicator bacteria on plates containing TSA alone (M. luteus) or plates containing TSA plus 0.3% Tween 80 (C. renale). Penicillin (Neo Sensitabs; A/S Rosco, Taastrup, Denmark) similarly applied (a 5-μg diffusible amount) was used as a positive control, and 5 μl of 100% methanol was used as a reagent blank. The plates were read after 1 and 2 days at 28°C.

Antagonism was determined by streaks of the test bacteria grown for 10 days at 28°C on plates of TSA (for M. luteus antagonism) or of TSA plus 0.3% Tween 80 (for C. renale antagonism). The plates were overlaid with 15 ml of nutrient broth soft agar (3 g of meat extract, 5 g of peptone, 8 g of NaCl, 4 g of agar liter−1) containing two loopfuls of the indicator bacterium C. renale DSM 20688T or M. luteus DSM 20030T per 250 ml, and the plates were read after 1 and 2 days at 28°C.

Morphology.

Gram staining was performed by the Hucker method (39). For scanning electron microscopy, blocks of TSA with colonies grown at 28°C for 7 days were placed for 10 min in 5% (wt/vol) KOH and fixed in 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) for 2 h. The agar blocks were then rinsed three times with the buffer, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, and critical point dried. These agar blocks were coated with platinum vapor and examined with a scanning electron microscope (Zeiss DSM 962, Jena, Germany). For thin sections, the cells, grown for 7 days at 28°C, were prefixed with 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7) for 2 h at room temperature and washed three times with the same buffer. The specimen was postfixed for 2 h in buffered 1% (wt/vol) osmium tetroxide, dehydrated in graded series of ethanol and acetone, and embedded in Epon LX-112. Thin sections were stained and examined as described elsewhere (3). The spermatozoa were fixed and examined by the same approach.

Cell chemistry and physiology.

For whole-cell fatty acid analysis, the isolates were grown on cellophane placed on Trypticase soy broth agar (TSBA) (BBL, Becton Dickinson and Company, Cockeysville, Md.) for 6 days at 28°C. Whole-cell fatty acid methyl esters were prepared by the method of Väisänen et al. (57) and analyzed with MIDI Aerobic Library version 3.90 (Microbial ID, Newark, Del.). Salt tolerance was tested on TSA plates containing 2.5, 5.0, 7.5, or 10% NaCl and read after 14 to 30 days at 28°C. For quinone analyses, cells were grown for 2 days in medium containing 0.3% peptone from casein, 0.3% yeast extract, and 0.23% Na2-succinate (pH 7.2). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed once in saline. Menaquinones were extracted as described previously (54). Extracts were analyzed directly by high-performance liquid chromatography without purification by thin-layer chromatography (TLC). Quinones were identified by comparison with the quinone profiles from reference strains such as Nocardiopsis dassonvillei DSM 43111T and Microbacterium esteraromaticum DSM 8608T. The bacterial mass for the following chemotaxonomic analyses was grown in Trypticase soy broth (DSMZ medium 535 [15]), collected by centrifugation, washed twice with distilled water, and freeze dried. The amino acid and sugar analysis of whole-cell hydrolysates followed previously described procedures (51). Polar lipids were extracted, examined by two-dimensional TLC, and identified by published methods (D. E. Minnikin, L. Alshamaony, and M. Goodfellow, Gas chromatography application note 228–241, Hewlett-Packard, Palo Alto, Calif., 1975). The occurrence of mycolic acids was determined by TLC following the procedure of Minnikin et al. (Gas chromatography application note 228–241, Hawlett-Packard, 1975).

Physiological characteristics.

Indoor isolates were characterized on the basis of 65 biochemical and physiological tests on microtiter plates as described previously (32, 33). Test plates were read after 7 days of incubation at 20°C.

Phylogenetic analyses.

The extraction of genomic DNA, PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene, and sequencing of the purified PCR products were carried out as described previously (44). Sequence reaction products were purified by ethanol precipitation and electrophoresed with a model 310 Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). The 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in this study were aligned against previously determined actinobacterial sequences by using the ae2 editor (34). The method of Jukes and Cantor (29) was used to calculate evolutionary distances. Phylogenetic dendrograms were generated by using various treeing algorithms contained in the PHYLIP package (19).

DNA-DNA reassociation analysis.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared by using the lysis protocol according to the method described by Altenbuchner and Cullum (2), starting with 5 g (wet weight) of cells. This was followed by purification according to the method described by Marmur (35) in order to obtain high-molecular-weight DNA. The concentrations of DNA obtained were determined chemically according to the method of Richards (46). Fragmentation, dialysis, and measurement of the initial renaturation rates in a Gilford 2600 spectrophotometer by the optical method of De Ley et al. (14) were done as described by Auling et al. (9). DNA was denatured for 5 min at 104°C, and 80°C was chosen as the optimum renaturation temperature. The degree of binding was calculated from the data of four repetitions by using formula no. 10 given by De Ley et al. (14).

RESULTS

Isolation of indoor actinobacterial strains.

A number of aerial mycelium-producing strains were isolated from indoor environments, and five of them were identified as members of the genus Nocardiopsis. The isolates originated from indoor air (isolates ES10.1 and 704a), dust (isolates 66/93 and 64/93), and water-damaged gypsum board (isolate 123) (Table 1).

Toxicity and antagonistic activity of Nocardiopsis strains.

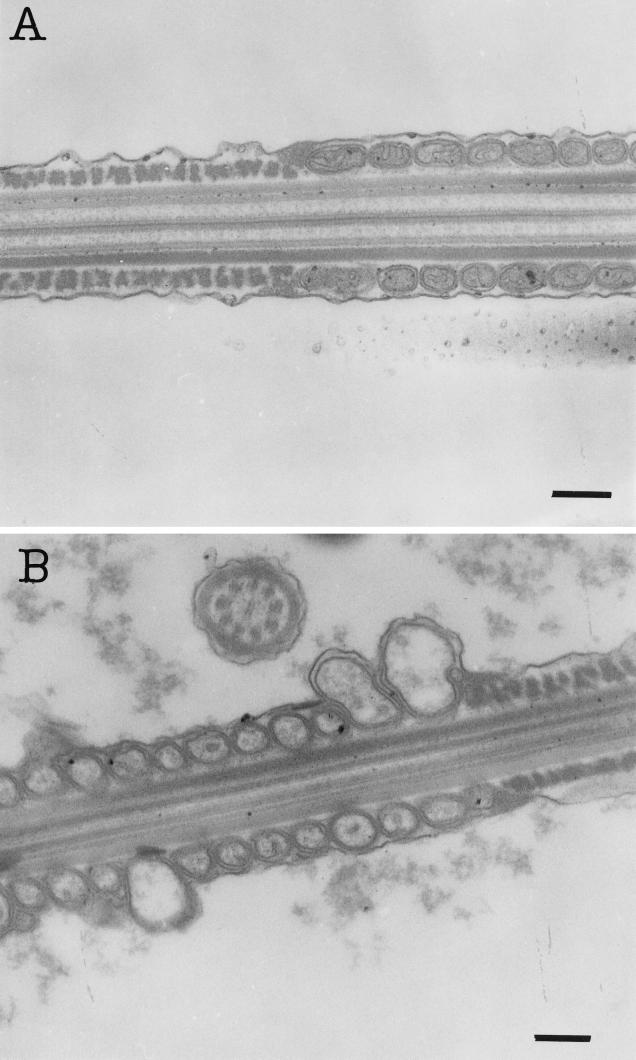

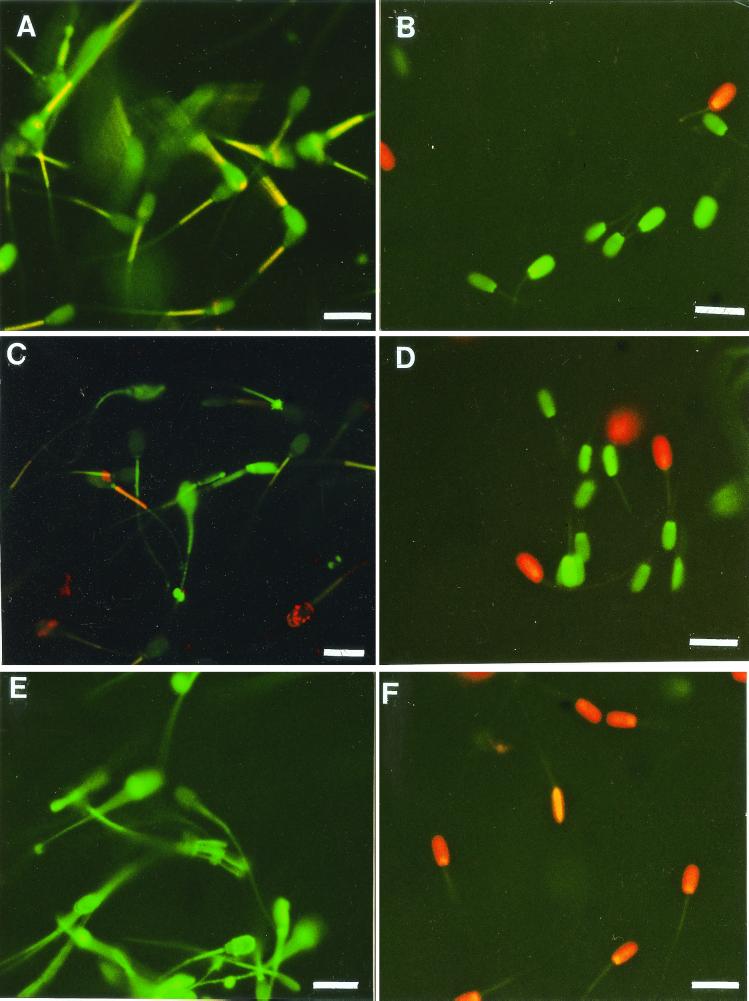

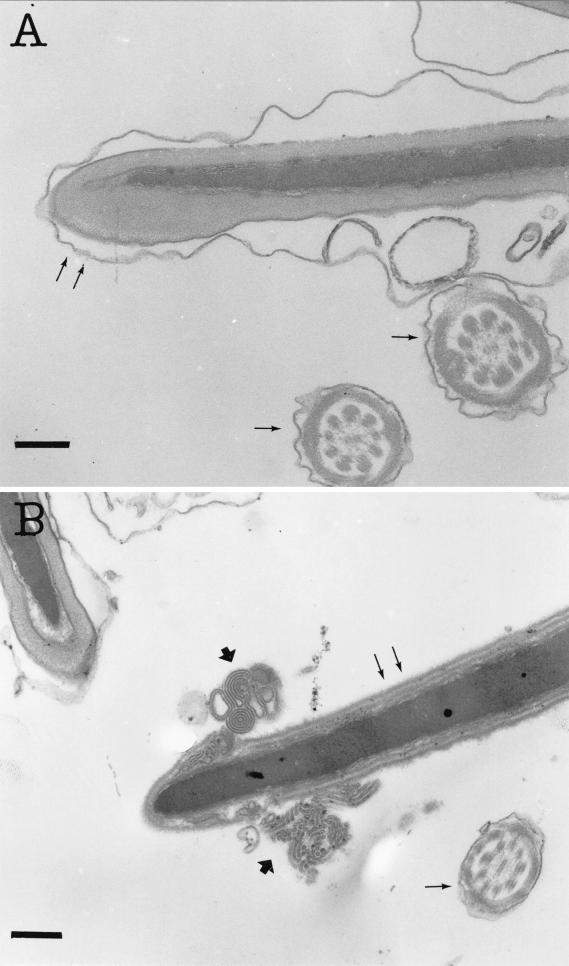

The results of toxicity and antagonistic activity testing of the indoor environment Nocardiopsis isolates and described Nocardiopsis species to boar spermatozoa and selected actinobacteria are shown in Table 2. Methanol extracts (≤30 μg of methanol-soluble solids [dry weight] ml−1) from the cultures of the isolates ES10.1 and 704a, as well as from N. prasina DSM 43845T, N. lucentensis DSM 44048T, and N. tropica DSM 44381T, inhibited the motility of ≥50% of the exposed boar spermatozoa. Metabolites from the indoor environment isolate ES10.1 inhibited motility without causing ultrastructural changes to boar spermatozoa (Fig. 1). Staining with the dual dye JC-1, shown in Fig. 2, revealed that exposure to ES10.1 extract quenched the yellow fluorescence in the midpiece of the sperm cell containing the mitochondria, indicating that substances emitted by this isolate dissipated the mitochondrial Δψ (compare Fig. 2C and A). Uptake of live-cell stain SYBR-14 by the sperm cells (Fig. 2D) was not affected by the exposure, indicating that the plasma membrane was intact. This remained the case when a 10-times-higher concentration of extract was used. Methanolic extracts prepared from the cultures of type strains of N. prasina, N. lucentensis, and N. tropica also induced changes in Δψ of boar sperm cells similar to those by isolate ES10.1. These results indicate that the strains of the various Nocardiopsis species excreted substances that induce changes in ion permeability of the mitochondrial inner membrane of sperm cells. Loss of yellow fluorescence in the JC-1-stained mitochondrial sheath of the spermatozoan middle region was also observed after exposure to extract from isolate 704a (compare Fig. 2E and A). The same exposure also converted the spermatozoan permeable to PI, visible as red fluorescence in Fig. 2F, and also depleted the spermatozoa of ATP. Transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of spermatozoa exposed to the extract isolate 704a (Fig. 3B) showed ultrastructural changes in the sperm head. The metabolite causing all of these changes was soluble and functional in 100% methanol, indicating that it was not a protein. The toxic metabolites from isolate 704a differed from those of isolate ES10.1 by clearly inducing damage to the plasma membrane of boar sperm cells.

TABLE 2.

Toxicity of indoor isolates and reference strains of Nocardiopsis to selected eukaryotic and prokaryotic target organisms

| Parameter | Strain(s) |

|---|---|

| Response of boar spermatozoa to ≤30 μg of extract ml−1 (EC50a) | |

| Inhibition of motility | ES 10.1 |

| 704a | |

| N. prasina DSM 43845T | |

| N. lucentensis DSM 44048T | |

| N. tropica DSM 44381T | |

| Loss of membrane integrity | 704a |

| Loss of resazurin-reducing ability | 704a |

| Depletion of ATP | 704a |

| Dissipation of mitochondrial Δψ | ES 10.1 |

| N. prasina DSM 43845T | |

| N. lucentensis DSM 44048T | |

| N. tropica DSM 44381T | |

| Inhibition of growth ofb: | |

| Corynebacterium renale DSM 20688T | 64/93 |

| N. lucentensis DSM 44048T | |

| Antagonistic activity towardc: | |

| Corynebacterium renale DSM 20688T | Saccharothrix coeruleofuscad DSM 43679T |

| N. dassonvillei DSM 43884 | |

| N. lucentensis DSM 44048T | |

| Micrococcus luteus DSM 20030T | N. lucentensis DSM 44048T |

EC50 (50% effective concentration) was assayed as the end point dilution of methanol extract causing a >50% change in vitality parameters of extended boar spermatozoa compared to that of spermatozoa exposed to diluent only (= reagent blank) as described by Andersson et al. (4).

The concentration of the extract used was ≥60 μg in the agar diffusion assay.

Antagonism was determined by streaks on plates containing TSA alone or TSA plus 0.3% Tween 80.

Formerly classified as Nocardiopsis coeruleofusca.

FIG. 1.

Transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of a middle piece of boar spermatozoa exposed for 3 days to methanol extract (16 pg ml−1) of Nocardiopsis strain ES 10.1 (A) or to water extract of the isolate Bacillus cereus F-5881 (B). The thin section in panel A shows intact membranes and normal size mitochondria, and that in panel B shows an intact middle piece outer membrane and swelled mitochondria. Bars, 0.2 μm.

FIG. 2.

Epifluorescense micrographs of exposed spermatozoa stained with JC-1 (A, C, and E) or with a combination of SYBR-14 and PI (B, D, and F). (A and B) Spermatozoa exposed to solvent (methanol) only. (C and D) Spermatozoa exposed for 4 days to methanol-soluble metabolites from the indoor Nocardiopsis strain ES 10.1 (30 μg ml−1). (E and F) Spermatozoa exposed for 4 days to methanol-soluble metabolites from Nocardiopsis strain 704a (25 μg ml−1). Excitation light, 390 to 490 nm. Bars, 10 μm. SYBR-14, known to bind DNA, was used in combination with a counterstain, PI. PI needs damaged plasma membranes to be able to penetrate into the cell and to intercalate in DNA (22). The dual dye JC-1 accumulates in mitochondria as “J-aggregates” and fluoresces yellow or orange when the potential (Δψ) is high, but remains green (monomeric form) when the Δψ is low (22).

FIG. 3.

Transmission electron micrographs of thin sections of boar spermatozoa. (A) Spermatozoon exposed to the solvent (methanol) only, showing intact membranes. (B) Spermatozoa exposed to methanol-soluble solids (26 μg ml−1) of the indoor Nocardiopsis strain 704a. Demolished membranes are visible (thick arrows). Single thin arrows show the transsection of boar sperm cell tail, and double thin arrows show the head of the boar sperm cell. Bars, 0.2 μm.

The type strain of N. lucentensis was strongly antagonistic to indicator species Micrococcus luteus DSM 20030T and to Corynebacterium renale DSM 20688T (inhibition zone, >20 mm) when tested by a streak assay on TSA plates (Table 2). N. dassonvillei DSM 43884 and Saccharothrix coeruleofusca DSM 43679T (formerly Nocardiopsis coeruleofusca) antagonized growth of C. renale DSM 20688T, but not that of M. luteus DSM 20030T.

Methanol extracts (≥60 μg ml−1) from the indoor isolate 64/93 and from N. lucentensis DSM 44048T inhibited growth of C. renale DSM 20688T when tested with filter paper disks by agar diffusion assay. The active substances from the indoor environment isolate 64/93 and from N. lucentensis DSM 44048T were soluble in methanol, indicating that they were not proteins. None of the cell-free methanol-extractable metabolites from Nocardiopsis isolates inhibited the growth of M. luteus DSM 20030T (Table 2).

Identification of the indoor isolates.

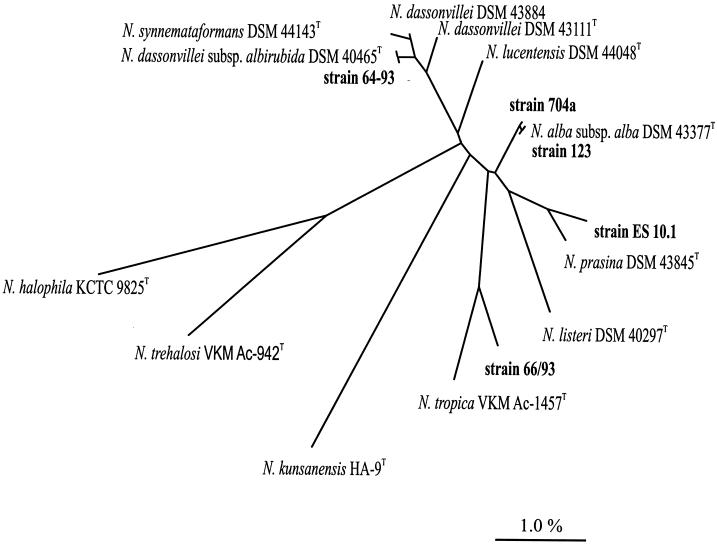

The whole-cell fatty acid methyl esters (FAME) patterns of five indoor environment isolates and eight reference strains of Nocardiopsis are shown in Table 3. Biomass harvested from TSBA plates (6 days, 28°C) of all strains contained iso- or anteiso-branched fatty acids as the major fatty acids, with smaller amounts of 10-methyl branched fatty acids, as found in the genus Nocardiopsis (24). Tuberculostearic acid (10-methyl-C18:0) was also present in all strains. Each of the five indoor isolates 123, 64/93, 66/93, 704a, and ES10.1 displayed a complex quinone system consisting exclusively of MK-10 as the major menaquinone with a variable degree of saturation [MK-10(H2, H4, H6, H8)]. Almost complete 16S rRNA gene sequences (1,454 to 1,460 nucleotides) were determined for the five indoor environment isolates. Phylogenetic analyses based on a data set comprising 1,404 unambiguous nucleotides between positions 41 and 1493 (Escherichia coli positions [11]) showed the new isolates to cluster within the radiation of the species of the actinobacterial genus Nocardiopsis (Fig. 4). The five indoor isolates thus are members of the genus Nocardiopsis and share 97.6 to 99.9% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity.

TABLE 3.

Composition (percent) of whole-cell fatty acids of the indoor isolates and reference strains of Nocardiopsis grown for 6 days on TSB agar at 28°C

| Fatty acid | Indoor isolates

|

Reference strains

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ES 10.1 | 66/93 | 64/93 | 123 | 704a | N. listeri DSM 40297T |

N. dassonvillei subsp. albirubida DSM 40465T |

N. dassonvillei DSM 43111T |

N. dassonvillei DSM 43884 |

N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T |

N. prasina DSM 43845T |

N. synnemataformans DSM 44143T |

N. lucentensis DSM 44048T |

N. trehalosi DSM 44380T |

N. tropica DSM 44381T |

|

| 15:0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 1.3 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 2.3 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| 16:0 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 2.1 | <1.0 | 1.5 | 3.2 | 1.7 | 2.0 | 2.4 | 2.3 | 1.1 | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.6 |

| 17:0 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 3.4 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 2.8 | <1.0 | 2.1 | 1.5 | <1.0 | 1.5 | 3.6 |

| 18:0 | 9.1 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 3.7 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 2.7 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 4.2 | 1.3 | 8.9 | 11.3 |

| 14:0 iso | 3.4 | 2.4 | 1.0 | 3.0 | 2.8 | 4.7 | 1.7 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 1.0 | <1.0 | 1.0 | 2.0 |

| 15:0 iso | 5.0 | 1.6 | 1.4 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 2.1 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 1.3 | <1.0 | 4.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 |

| 15:0 anteiso | 10.2 | 8.6 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 1.4 | 7.3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 4.1 | 2.5 | 9.0 | 2.5 | 5.1 |

| 16:0 iso | 22.0 | 19.8 | 23.6 | 41.2 | 43.3 | 29.9 | 33.0 | 36.4 | 26.5 | 39.5 | 20.9 | 31.8 | 18.1 | 16.8 | 26.6 |

| 16:0 10 methyl | <1.0 | <1.0 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1.1 | 1.1 | <1.0 | 5.5 | <1.0 | <1.0 |

| 17:0 iso | 4.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.3 | <1.0 | 3.0 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 1.1 | 3.3 | 2.5 | 6.7 | 3.2 | 3.0 |

| 17:0 anteiso | 10.7 | 16.5 | 19.3 | 6.6 | 5.2 | 10.2 | 9.3 | 10.7 | 14.0 | 5.8 | 17.7 | 13.5 | 27.3 | 9.3 | 13.8 |

| 17:0 10 methyl | 3.3 | 4.3 | 4.6 | 5.3 | 5.5 | 7.0 | 4.4 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 4.8 | 9.3 | 3.5 | 7.6 | 2.7 | 3.8 |

| 18:0 iso | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 4.4 | 2.4 | 4.2 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 2.3 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 3.9 | <1.0 | 3.5 | 2.8 |

| TBSAb 10Me 18:0 | 12.1 | 14.0 | 14.5 | 15.6 | 12.1 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 10.8 | 15.1 | 16.0 | 21.3 | 8.5 | 3.8 | 14.8 | 11.8 |

| 16:1 iso G | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 7.1 | <1.0 |

| 17:1 anteiso A | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | <1.0 | 6.8 | <1.0 |

| 17:1 ω8c | 1.6 | 3.8 | 2.3 | 1.4 | 3.3 | 2.8 | 7.1 | 3.6 | 4.3 | 2.4 | 1.9 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 2.3 | 2.6 |

| 18:1 ω9c | 8.4 | 10.0 | 5.9 | 7.2 | 14.6 | 6.4 | 13.9 | 12.5 | 10.1 | 11.2 | 4.4 | 15.9 | 1.9 | 9.9 | 9.0 |

| Othera | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 4.6 | 2.8 | 3.9 | 2.3 | <1.0 | 2.8 | 5.6 | 6.2 | 1.9 |

“Other” includes 10:0 iso, 12:0 iso, 12:0 2OH, 13:0, 13:0 iso, 13:0 anteiso, 14:0, 14:0 anteiso, 15:1 iso G, 15:1 ω6c, 15:1 ω8c, 16:0 anteiso, 16:1 iso H, 16:1 ω7c/15 iso 2OH, 17:0 cyclo, anteiso 17:1 ω9c, 17:1 ω5c, 17:1 ω6c, 18:1 iso H, 18:1 iso G, 18:1 ω9c/ω12t/ω7c, 19:0, 19:0 cyclo ω10c/un, 19:0 iso, 19:0 anteiso, 19:0 10 methyl, unknown 19:1, and iso 17:1 ω9c.

TBSA, tuberculostearic acid.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic dendrogram based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The scale bar represents 1 inferred nucleotide substitution per 100 nucleotides.

Based on phylogenetic data, isolate 123 is identical to N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T (100% similarity). The whole-cell fatty acids of this isolate were most similar to those of N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T (Table 3). Physiologically, isolate 123 was closest to N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T (46 shared properties [Table 4]) and N. prasina DSM 43845T (43 shared properties [Table 4]). Isolate 64/93 shared 100% 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity with N. dassonvillei subsp. albirubida DSM 40465T. Also based on fatty acid (Table 3) and physiological data, this isolate was closest to N. dassonvillei, sharing 43 to 45 physiological properties (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Physiological and biochemical characteristics of the Nocardiopsis strains used in this study

| Characteristicsa | Reaction of strainb

|

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indoor isolates

|

Reference strains

|

||||||||||||||

| ES 10.1 | 66/93 | 64/93 | 123 | 704a | N. listeri DSM 40297T |

N. dassonvillei subsp. albirubida DSM 40465T |

N. dassonvillei DSM 43111T |

N. dassonvillei DSM 43884 |

N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T |

N. prasina DSM 43845T |

N. synnemataformans DSM 44143T |

N. lucentensis DSM 44048T |

N. trehalosi DSM 44380T |

N. tropica DSM 44381T |

|

| Enzymic activity (catalase) | + | + | + | NDc | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | + | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Utilization of: | |||||||||||||||

| N-Acetyl-d-glucosamine | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| l-Arabinose | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | (+) | (+) |

| p-Arbutin | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| d-Fructose | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | (+) | + |

| d-Galactose | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| Gluconate | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| d-Glucose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| d-Mannose | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | (+) | + |

| d-Maltose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | (+) | + |

| α-d-Melibiose | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | ND | ND |

| l-Rhamnose | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | (+) | + | (+) | (+) |

| d-Ribose | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| d-Sucrose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − |

| Salicin | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | − | + |

| d-Trehalose | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| d-Xylose | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | (+) | + |

| Adonitol | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − |

| i-Inositol | − | − | − | − | + | (+) | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Maltitol | − | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + |

| Putrescine | + | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | + |

| Acetate | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| Propionate | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| 4-Aminobutyrate | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| Azelate | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − |

| Citrate | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Fumarate | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Glutarate | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − |

| dl-Lactate | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | + |

| l-Malate | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| Mesaconate | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Oxoglutarate | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| Pyruvate | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Suberate | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| l-Alanine | + | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| β-Alanine | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| l-Aspartate | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| l-Histidine | − | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| l-Leucine | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | − | + |

| l-Ornithine | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| l-Phenylalanine | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| l-Proline | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| l-Serine | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| l-Tryptophan | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 3-Hydroxybenzoate | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| 4-Hydroxybenzoate | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Phenylacetate | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + |

| Hydrolysis of: | |||||||||||||||

| Esculin | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | + |

| pNP-α-d-glucopyranoside | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| pNP-β-d-glucopyranoside | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Bis-pNP-phosphate | − | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | + | + |

| pNP-phenylphosphonate | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| pNP-phosphorylcholine | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| 2-Deoxythymidine-5′-pNP-phosphatase | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − |

| l-Alanine-pNA | − | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + |

| l-Glutamate-γ-3-carb.-pNA | − | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| l-Proline-pNA | − | + | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | + | + |

None of the strains utilized d-sorbitol, adipate, itaconate, pNP-β-d-galactopyranoside, or pNP-β-d-glucuronide. All strains utilized d-cellobiose, d-mannitol, cis-aconitate, and dl-3-hydroxybutyrate. pNP, para-nitrophenyl; pNA, para-nitroanilide.

+, positive; (+), weak positive; −, negative.

ND, not determined.

Isolate 704a was phylogenetically highly related to isolate 123 (99.9%) and to N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T (99.9%). According to whole-cell fatty acid data, isolate 704a also was similar to isolate 123 and to N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T (Table 3). However, isolate 704a was physiologically very different from any validly described Nocardiopsis species, which may in part be due to its faster growth on test plates (2 days) compared to that of other indoor isolates (3 to 4 days). Indoor isolate 704a differed from all Nocardiopsis species and other indoor isolates by its ability to utilize l-ornithine, l-tryptophan and 3-hydroxybenzoate (Table 4). It did not utilize fumarate or hydrolyze para-nitrophenyl-α-d-glucopyranoside, whereas all other Nocardiopsis strains studied did so (Table 4). Isolate 704a also differed from the indoor isolate 123 and N. alba subsp. alba DSM 43377T by being toxic to boar sperm cells (Table 2).

The two isolates that showed the least 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity to validly described Nocardiopsis species were ES10.1 and 66/93. Isolate ES10.1 clustered with N. prasina DSM 43845T (99.4% similarity), but showed in DNA-DNA reassociation analysis only a 58% degree of binding to N. prasina DSM 43845T. Isolate ES10.1 had fatty acids similar to those of N. trehalosi DSM 44380T, N. tropica DSM 44381T, and N. prasina DSM 43845T (Table 3). Physiologically, isolate ES10.1 was closest to N. listeri DSM 40297T. The ability to assimilate putrescine, acetate, 4-aminobutyrate, azelate, glutarate, l-alanine, and 4-hydroxybenzoate differentiated isolate ES10.1 from N. listeri DSM 40297T (Table 4).

The 16S rRNA gene sequence of the indoor isolate 66/93 was most similar to N. tropica DSM 44381T (99.2%). It shared whole-cell fatty acid composition with another indoor isolate, 64/93. The closest reference strains were N. dassonvillei strain DSM 43884 and N. tropica DSM 44381T. Indoor isolate 66/93 shared 49 physiological characters with N. dassonvillei strain DSM 43884.

Based on the results presented above, isolates 123 and 704a were closest to N. alba subsp. alba, and isolate 64/93 was closest to N. dassonvillei subsp. albirubida. The indoor environment isolates ES10.1 and 66/93 were not similar to any validly described Nocardiopsis species. Therefore, these were characterized in detail.

Whole-cell hydrolysates of isolates ES10.1 and 66/93 contained ribose and glucose and mesodiaminopimelic acid as the only diamino acid of the peptidoglycan. No mycolic acids were found. The polar lipid pattern was composed of the diagnostic phosphatidylcholine and phosphatidylinositol, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphatidylmethylethanolamine, diphosphatidylglycerol, and three to four unknown phospholipids with a high Rf value (above that of diphosphatidylglycerol).

The vegetative hyphae of Nocardiopsis isolates ES10.1 and 66/93 were yellowish, and the aerial hyphae were white on TSA plates (3 days at 28°C). No diffusible pigments were produced. The isolates formed gram-positive hyphae penetrating into the agar and compact colonies on the agar surface. The hyphae of isolate ES10.1 were slightly spiral shaped, and those of 66/93 formed thick bundles detected by scanning electron microscopy. The hyphae of isolate ES10.1 fragmented into rod-shaped elements 0.5 to 2 μm long and 0.5 μm wide. The hyphae of the indoor isolate 66/93 were 0.3 to 0.5 μm wide as measured from transmission electron microscopy figures. Both isolates grew to colonies at 28 and at 37°C in 3 days and at 10°C in 14 days, but not at 50°C. The isolates grew well in the presence of 7.5% NaCl, but in 10% NaCl, isolate ES10.1 grew only slowly (30 days).

DISCUSSION

We have earlier reported Nocardiopsis species in sick building environments, in indoor air, and at high density in building material (105 to 106 CFU g−1) (6, 42, 49). In this paper, we demonstrate a new feature of the genus Nocardiopsis: the production of methanol-soluble metabolites that inhibited the motility of boar spermatozoa at low concentration.

Metabolites from strain ES10.1 and the type strains of N. prasina, N. lucentensis, and N. tropica dissipated the mitochondrial Δψ in boar spermatozoa, while the plasma membrane remained intact. Cereulide produced by Bacillus cereus and valinomycin produced by indoor isolates of Streptomyces griseus have been reported to collapse the Δψ in mammalian mitochondria (38). These potassium ionophores also cause swelling of mitochondria (5, 38). Nocardiopsis extracts did not cause swelling of mitochondria, thus representing a mitochondriotoxin different from those emitted by indoor isolates of Streptomyces griseus (5) and Bacillus cereus (38). Mitochondrial damage is known to induce pathways leading to programmed cell death (10). Our results show that mitochondrial toxicity is a property widely present among members of the genus Nocardiopsis. The indoor strain N. alba subsp. alba 704a resembled the food-poisoning and mastitis-related isolates of Bacillus licheniformis in its toxic action (48).

Nocardiopsis trehalosi (previously N. trehalosei) has been reported to produce 3-trehalosamine, a disaccharide with activity against Bacillus subtilis (16). We show here that two Nocardiopsis species, N. dassonvillei subsp. albirubida 66/93 and N. lucentensis DSM 44048T, produced a cell-free methanol-soluble substance inhibiting the growth of Corynebacterium renale. In addition, N. dassonvillei DSM 43884, N. lucentensis DSM 44048T, and Saccharothrix coeruleofusca DSM 43679T (formerly Nocardiopsis coeruleofusca) were antagonistic towards Corynebacterium renale DSM 20688T. Corynebacterium renale is susceptible to Staphylococcus aureus strains producing staphylococcin BacR1, which is associated with the production of exfoliative toxin B connected to human skin disease (13). N. lucentensis DSM 44048T was also shown to strongly antagonize Micrococcus luteus DSM 20030T a known indicator for tracking producers of potassium ionophore types of toxins like valinomycin (43).

The indoor strains of Nocardiopsis showed several conspicuous environmentally significant features. (i) The ability of the indoor strains ES10.1 and 66/93 to grow in the presence of high salt concentrations (7.5 to 10% of NaCl) will favor survival in a low-water-activity environment, such as may occur under the repeated cycles of wetting and drying of building materials, which leads to changing moisture conditions. The type strains of N. lucentensis, N. alba subsp. alba, and N. prasina (former name, N. alba subsp. prasina), N. synnemataformans and N. tropica also grow at high salt concentrations (18, 58, 59). (ii) A wide range of substrates were utilized by the indoor Nocardiopsis strains (Table 4). This will promote their propagation in nutrient-deficient environments such as building materials. (iii) Antagonistic properties of the indoor Nocardiopsis strains give them a competitive advantage in water-damaged building materials.

Many actinobacterial genera are known as producers of antibiotics or antimicrobial substances (23, 28). Members of the genera Streptosporangium, Microbispora, Actinomadura, and Thermomonospora, which are related to the genus Nocardiopsis, are also known to produce a wide variety of antibiotics (23, 25, 27, 41, 53, 56). Indoor actinobacteria have previously been reported as being antagonistic to Streptococcus salivarius subsp. thermophilus, Candida albicans, and Alternaria brassicola (45).

The xerotolerance and wide range of substrate utilization of the Nocardiopsis species, combined with the ability to emit toxic nonprotein substances, indicate that members of this genus may well survive and also represent hazards to human health in water-damaged indoor environments.

In this paper, three of the indoor Nocardiopsis isolates were identified as N. alba subsp. alba and N. dassonvillei subsp. albirubida. We also propose two new species of Nocardiopsis as represented by strains ES10.1 and 66/93. These indoor strains were similar to other Nocardiopsis strains in morphology, producing white, moderately branched aerial mycelia and yellowish substrate mycelia (37). The 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity between strain ES10.1 and N. prasina DSM 43845T was 99.4%, but the low match of physiological properties together with and DNA-DNA reassociation studies (degree of binding of 58% to N. prasina DSM 43845T) confirm that strain ES10.1 was a novel species. The 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of the indoor strain 66/93 was highest to N. tropica DSM 44381T (99.2%) (18). In the case of members of the genus Nocardiopsis, this is a low value (44) and in combination with phenotypic differentiation provides evidence for the description of strain 66/93 as a novel species. During the preparation of this article, the new Nocardiopsis species N. kunsanensis was described (12). Based on 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons, N. kunsanensis HA-9T is not closely related to the new Nocardiopsis species N. exhalans strain ES10.1 and N. umidischola strain 66/93 proposed in this paper (Fig. 4). The isolation of novel Nocardiopsis strains from indoor environments, including dust and air, further extends the reported habitats of this genus.

Description of Nocardiopsis exhalans sp. nov.

Nocardiopsis exhalans (ex.ha′lans. L. partic. adj. exhalans, emitting odors, fumes, toxins, etc.). The vegetative hyphae are yellowish and penetrate agar. The aerial hyphae are white, slightly spiral shaped, and 0.5 μm in diameter and fragment to form rod-shaped, nonmotile spores. No soluble pigment is produced. Gram positive. Catalase positive and aerobic. Grows in the presence of 10% NaCl. Growth occurs at 10, 28, and 37°C; no growth at 50°C. Assimilates arabinose, cellobiose, fructose, gluconate, glucose, mannose, maltose, rhamnose, ribose, sucrose, trehalose, xylose, mannitol, putrescine, acetate, cis-aconitate, 4-aminobutyrate, azelate, citrate, fumarate, glutarate, 3-hydroxybutyrate, pyruvate, suberate, l-alanine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, 4-hydroxybenzoate, and phenylacetate, but not N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, arbutin, galactose, melibiose, salicin, adonitol, inositol, maltitol, sorbitol, propionate, adipate, itaconate, lactate, malate, mesaconate, oxoglutarate, β-alanine, aspartate, histidine, leucine, ornithine, tryptophan, or 3-hydroxybenzoate. Esculin is not hydrolyzed. Phosphatase and α-glucosidase are produced. The fatty acid profile includes straight-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, branched-chain fatty acids of the iso and anteiso types, and 10-methyl branched-chain fatty acids. Predominant menaquinones were MK-10 (H6) and MK-10 (H8), and relatively high concentrations of MK-10 (H4), MK-9 (H6), and MK-9 (H8) were found. Mesodiaminopimelic acid was the diamino acid of the peptidoglycan. The polar lipid pattern was composed of the diagnostic phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatidylinositol, phosphotidylglycerol, phosphatidylmethylethanolamine, and diphosphatidylglycerol. The type strain was isolated from the indoor air of the basement of a water-damaged building of which the occupants suffered from nonspecific health symptoms. The type strain of Nocardiopsis exhalans is strain ES10.1 (=DSM 44407 = NRRL B-24123).

Description of Nocardiopsis umidischolae sp. nov.

Nocardiopsis umidischolae (u. mi. di. scho′ lae L. adj. umidus, moist; L. fem. n. schola, school; N.L. gen. fem. n. umidischolae, of a moist school). The vegetative hyphae are yellowish and penetrate agar. The aerial hyphae are white and 0.2 μm in diameter, and they form thick bundles. No soluble pigment is produced. Gram positive. Catalase positive and aerobic. Grows in the presence of 7.5% NaCl. Growth occurs at 10, 28, and 37°C; no growth at 50°C. Assimilates N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, arabinose, arbutin, cellobiose, fructose, galactose, gluconate, glucose, mannose, maltose, melibiose, rhamnose, ribose, sucrose, trehalose, xylose, maltitol, mannitol, acetate, propionate, cis-aconitate, 4-aminobutyrate, citrate, fumarate, glutarate, 3-hydroxybutyrate, lactate, malate, oxoglutarate, pyruvate, l-alanine, β-alanine, aspartate, histidine, phenylalanine, proline, serine, and phenylacetate, but not salicin, adonitol, inositol, sorbitol, putrescine, adipate, azelate, itaconate, mesaconate, suberate, leucine, ornithine, tryptophan, 3-hydroxybenzoate, or 4-hydroxybenzoate. Esculin is not hydrolyzed. Produces α- and β-glucosidases, phosphatase, and peptidases. The fatty acid profile includes straight-chain saturated and unsaturated fatty acids, branched-chain fatty acids of the iso and anteiso types, and 10-methyl branched-chain fatty acids. The predominant menaquinone was MK-10 (H6), and relatively high concentrations of MK-10 (H4), MK-10 (H8), and MK-11 (H6) were found. Mesodiaminopimelic acid was the diamino acid of the peptidoglycan. The polar lipid pattern was composed of the diagnostic phosphatidylcholine, and phosphatitylinositol, phosphatidylglycerol, phosphotidylmethylethanolamine, and diphosphatidylglycerol. The type strain was isolated from the indoor dust of a water-damaged school. The type strain of Nocardiopsis umidischolae is strain 66/93 (=DSM 44362 = NRRL B-24122).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant of ABS Graduate School to J.P., the Center of Excellence Fund of the University of Helsinki, the Finnish Fund for Work Environment, and the Academy of Finland by grants to M.S.-S.

We thank Tuire Koro and Arja Strandell for preparing the thin sections, M. C. Andersson for advice on the analysis of boar spermatozoa and Jyrki Juhanoja for advice on electron microscopy. We thank the Laboratory of Electron Microscopy of Helsinki University for access to their facilities. We also thank Erko Stackebrandt for releasing the 16S rRNA gene sequences of Nocardiopsis tropica DSM 44381 and Nocardiopsis trehalosi DSM 44380 prior to publishing, Inge Reupke for technical assistance during isolation of chromosomal DNA and optical determination of renaturation, and especially H. Trüper for help with Latin names of bacteria.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ali-Vehmas T, Louhi M, Sandholm M. Automation of the resazurin reduction test using fluorometry of microtitration trays. J Vet Med B. 1991;38:358–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1991.tb00883.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altenbuchner J, Cullum J. DNA amplification and an unstable arginine gene in Streptomyces lividans 66. Mol Gen Genet. 1984;195:1513–1523. doi: 10.1007/BF00332735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersson M A, Laukkanen M, Nurmiaho-Lassila E-L, Rainey F A, Niemelä S, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Bacillus thermosphaericus sp. nov. A new thermophilic ureolytic Bacillus isolated from air. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1995;18:203–220. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andersson M A, Nikulin M, Köljalg U, Andersson M C, Rainey F J, Reijula K, Hintikka E-L, Salkinoja-Salonen M J. Bacteria, molds, and toxins in water-damaged building materials. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:387–393. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.387-393.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersson M A, Mikkola R, Kroppenstedt R, Rainey F A, Peltola J, Helin J, Sivonen K, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Mitochondrial toxin produced by Streptomyces griseus strains isolated from an indoor environment is valinomycin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:4767–4773. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.4767-4773.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andersson M A, Weiss N, Rainey F A, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Dust-borne bacteria in animal sheds, schools and children's day care centers. J Appl Microbiol. 1999;86:622–634. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.1999.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. Categorization of biological agents according to hazard and categories of containment. 4th ed. London, United Kingdom: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anonymous. Indoor air guideline. Department of Social Affairs and Health. Helsinki, Finland: Edita; 1997. . (In Finnish.) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Auling G, Probst A, Kroppenstedt R. Chemo- and molecular taxonomy of d(−)-tartrate-utilizing pseudomonads. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1986;8:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernardi P, Scorrano L, Colonna R, Petronilli V, Di Lisa F. Mitochondria and cell death. Mechanistic aspects and methodological issues. Eur J Biochem. 1999;264:687–701. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brosius J, Palmer M L, Kennedy J P, Noller H F. Complete nucleotide sequence of the ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4801–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun J, Bae K S, Moon E Y, Jung S-O, Lee H K, Kim S-J. Nocardiopsis kunsanensis sp. nov., a moderately halophilic actinomycete isolated from a saltern. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:1909–1913. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-5-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Crupper S S, Gies A J, Iandolo J J. Purification and characterization of staphylococcin BacR1, a broad-spectrum bacteriocin. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4185–4190. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.11.4185-4190.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.De Ley J, Cattoir H, Reynaerts A. The quantitative measurements of DNA-hybridization from renaturation rates. Eur J Biochem. 1970;12:133–142. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1970.tb00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen. Catalogue of strains. Braunschweig, Germany: DSMZ; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dolak L, Castle T, Laborne A. 3-Trehalosamine, a new disaccharide antibiotic. J Antibiot. 1980;33:690–694. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.33.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Etzel R, Montana E, Sorenson W, Kullman G, Allan T, Dearborn D. Acute pulmonary hemorrhage in infants associated with exposure to Stachybotrys atra and other fungi. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:757–762. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.8.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evtushenko L, Taran V, Akimov V, Kroppenstedt R, Tiedje J, Stackebrandt E. Nocardiopsis tropica sp. nov., Nocardiopsis trehalosi sp. nov., rev. and Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. albirubida subsp. nov., comb. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:73–81. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsenstein J. Phylogenetic inference package, version 3.5.1. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flannigan B, McCabe E, McGarry F. Allergenic and toxigenic micro-organisms in houses. J Appl Bacteriol Symp Suppl. 1991;70:61S–73S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flannigan B, Miller J D. Health implications of fungi in indoor environments—an overview. In: Samson R A, Flannigan B, Flannigan M E, Verhoeff A P, editors. Health implications of fungi in indoor environments. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garner D L, Thomas C A, Gravance C G. The effect of glycerol on the viability, mitochondrial function and acrosomal integrity of bovine spermatozoa. Reprod Domest Anim. 1999;34:399–404. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gräfe U. Biochemie der Antibiotika: Struktur-Biosynthese-Wirkmechanismus. Heidalberg, Germany: Spektrum Akademischer-Verlag GmbH; 1992. pp. 219–318. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grund E, Kroppenstedt R M. Chemotaxonomy and numerical taxonomy of the genus Nocardiopsis Meyer 1976. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1990;40:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harada K, Kimura I, Takami E, Suzuki M. Structural investigation of the antibiotic sporaviridin. X. Isolation and characterization of components of N-acetylsporaviridins. J Antibiot. 1984;37:976–983. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hendry K, Cole E. A review of mycotoxins in indoor air. J Toxicol Environ Health. 1993;38:183–198. doi: 10.1080/15287399309531711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ikemoto T, Katayama T, Haenishi T. Aculeximycin, a new antibiotic from Streptosporangium albidum. II. Isolation, physicochemical and biological properties. J Antibiot. 1983;36:1097–1100. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.36.1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jack R W, Tagg J R, Ray B. Bacteriocins of gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:171–200. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.2.171-200.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Juonala T, Lintukangas S, Nurttila T, Andersson M C. Relationship between semen quality and fertility in 106 A1-boars. Reprod Domest Anim. 1998;33:155–158. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Juonala T, Salonen E, Nurttila T, Andersson M C. Three fluorescence methods for assessing boar sperm viability. Reprod Domest Anim. 1999;34:83–87. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kämpfer P, Steiof M, Dott W. Microbiological characterization of a fuel-oil contaminated site including numerical identification of heterotrophic water and soil bacteria. Microb Ecol. 1991;21:227–251. doi: 10.1007/BF02539156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kämpfer P, Denner E B M, Meyer S, Moore E R B, Busse H-J. Classification of “Pseudomonas azotocolligans” Anderson 1955, 132, in the genus Sphingomonas as Sphingomonas trueperi sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:577–583. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Parker C T, Jr, Garrity G M, Larsen N, Bing L, Lilburn T G, McCaughey M J, Olsen G J, Overbeek R, Pramanik S, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M, Woese C R. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:171–173. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.1.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acids from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 36.McNeil M M, Brown J M. The medically important aerobic actinomycetes: epidemiology and microbiology. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:357–417. doi: 10.1128/cmr.7.3.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meyer J. Nocardiopsis, a new genus of the order Actinomycetales. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1976;26:487–493. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mikkola R, Saris N-E, Grigoriev P A, Andersson M A, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Ionophoretic properties and mitochondrial effects of cereulide, the emetic toxin of B. cereus. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:112–117. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murray R G E, Doetsch R N, Robinow C F. Determinative and cytological light microscopy. In: Gerhardt P, Murray R G E, Wood W A, Krieg N R, editors. Methods for general and molecular bacteriology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1994. pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paananen A, Mikkola R, Sareneva T, Matikainen S, Andersson M, Julkunen I, Salkinoja-Salonen M, Timonen T. Inhibition of human NK cell function by valinomycin, a toxin from Streptomyces griseus in indoor air. Infect Immun. 2000;68:165–169. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.165-169.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel M, Hegde V, Horan A, Gullo V, Loebenberg D, Marquez J, Miller G, Puar M, Waitz J. A novel phenazine antifungal antibiotic, 1,6-dihydroxy-2-chlorophenazine: fermentation, isolation, structure and biological properties. J Antibiot. 1984;37:943–948. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.37.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peltola J, Andersson M A, Haahtela T, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Rainey F A, Kroppenstedt R M, Samson R A, Salkinoja-Salonen M. Toxic-metabolite-producing bacteria and fungus in an indoor environment. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2001;67:3269–3274. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.7.3269-3274.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Perkins J B, Guterman S K, Howitt C L, Williams II V E, Pero J. Streptomyces genes involved in biosynthesis of the peptide antibiotic valinomycin. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3108–3116. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.6.3108-3116.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rainey F A, Ward-Rainey N, Kroppenstedt R M, Stackebrandt E. The genus Nocardiopsis represents a phylogenetically coherent taxon and a distinct actinomycete lineage: proposal of Nocardiopsaceae fam. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:1088–1092. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-4-1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Räty K, Raatikainen O, Holmalahti J, von Wright A, Joki S, Pitkänen A, Saano V, Hyvärinen A, Nevalainen A, Buti I. Biological activities of Actinomycetes and fungi isolated from the indoor air of problem houses. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad. 1994;34:143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Richards G M. Modification of the diphenylamine reaction giving increased sensitivity and simplicity in the estimation of DNA. Anal Biochem. 1974;57:369–376. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(74)90091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rylander R. Microbial cell wall constituents in indoor air and their relation to disease. Indoor Air. 1998;4(Suppl.):59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Salkinoja-Salonen M S, Vuorio R, Andersson M A, Kämpfer P, Andersson M C, Honkanen-Buzalski T, Scoging A. Toxigenic strains of Bacillus licheniformis related to food poisoning. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4637–4645. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4637-4645.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Salkinoja-Salonen M S, Andersson M A, Mikkola R, Paananen A, Peltola J, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Vuorio R, Saris N-E, Grigorjev P, Helin J, Kõljalg U, Timonen T. Toxigenic microbes in indoor environment: identification, structure, and biological effects of the aerosolizing toxins. In: Johanning E, editor. Bioaerosols, fungi and mycotoxins: health effects, assessment, prevention and control. Albany, N.Y: Eastern New York Occupational and Environmental Health Center; 1999. pp. 432–443. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sorenson W G, Frazer D G, Jarvis B B, Simpson J, Robinson V A. Trichothecene mycotoxins in aerosolized conidia of Stachybotrys atra. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:1370–1375. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.6.1370-1375.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stanek J L, Roberts G D. Simplified approach to identification of aerobic actinomycetes by thin-layer chromatography. Appl Microbiol. 1974;28:226–231. doi: 10.1128/am.28.2.226-231.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun H H, White C B, Dedinas J, Cooper R. Methylpendolmycin, an indolactam from a Nocardiopsis sp. J Nat Prod. 1991;54:1440–1443. doi: 10.1021/np50077a040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takizawa M, Hida T, Horiguchi T, Hiramoto A, Harada S, Tanida S. TAN-1511 A, B and C, microbial lipopeptides with G-CSF and GM-CSF inducing activity. J Antibiot. 1995;48:579–588. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.48.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tindall B. Lipid composition of Halobacterium lacusprofundi. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;66:199–202. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsujibo H, Sakamoto T, Miyamoto K, Kusano G, Ogura M, Hasegawa T, Inamori Y. Isolation of cytotoxic substance, kalafungin from an alkalophilic actinomycete, Nocardiopsis dassonvillei subsp. prasina. Chem Pharm Bull. 1990;38:2299–2300. doi: 10.1248/cpb.38.2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tsurumi Y, Ohata N, Iwamoto T, Shigematsu N, Sakamoto K, Nishikawa M, Kiyoto S, Okuhara M. WS79089A, B and C, new endothelin converting enzyme inhibitors isolated from Streptosporangium roseum no. 79089: taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J Antibiot. 1994;47:619–630. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.47.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Väisänen O M, Nurmiaho-Lassila E-L, Marmo S A, Salkinoja-Salonen M S. Structure and composition of biological slimes on paper and board machines. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:641–653. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.2.641-653.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yassin A F, Galinski E A, Wohlfarth A, Jahnke K-D, Schaal K P, Trüper H G. A new actinomycete species, Nocardiopsis lucentensis sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1993;43:266–271. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yassin A F, Rainey F A, Burghardt J, Gierth D, Ungerechts J, Lux I, Seifert P, Bal C, Schaal K P. Description of Nocardiopsis synnemataformans sp. nov., elevation of Nocardiopsis alba subsp. prasina to Nocardiopsis prasina comb. nov., and designation of Nocardiopsis antarctica and Nocardiopsis alborubida as later subjective synonyms of Nocardiopsis dassonvillei. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:983–988. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]