Key Points

Question

Is inclusion of hospital events, interventions, and responses to treatment in the first month after severe intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) or intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) associated with improved prediction of functional outcome trajectory among survivors with initial poor outcome?

Findings

In this post hoc longitudinal analysis of the Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage phase 3 trial (CLEAR-III) and the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE-III) phase 3 trial, more than 40% of patients with poor outcome at day 30 recovered to good outcome by 1 year. Inclusion of hospital events and hematoma volume reduction was significantly associated with enhanced discrimination of eventual functional recovery at 1 year.

Meaning

The findings indicate that hospital events significantly influenced long-term functional recovery after ICH and IVH, suggesting that aggressive ICH and IVH resolution and prevention of systemic complications and cerebral ischemic injury may promote better outcomes among patients with ICH and IVH with high clinical severity.

This secondary analysis of 2 phase 3 clinical trials evaluates 1-year functional recovery among patients with intracerebral and intraventricular hemorrhage and initial severe disability and assesses factors associated with long-term recovery.

Abstract

Importance

Patients who survive severe intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) typically have poor functional outcome in the short term and understanding of future recovery is limited.

Objective

To describe 1-year recovery trajectories among ICH and IVH survivors with initial severe disability and assess the association of hospital events with long-term recovery.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This post hoc analysis pooled all individual patient data from the Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage phase 3 trial (CLEAR-III) and the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE-III) phase 3 trial in multiple centers across the US, Canada, Europe, and Asia. Patients were enrolled from August 1, 2010, to September 30, 2018, with a follow-up duration of 1 year. Of 999 enrolled patients, 724 survived with a day 30 modified Rankin Scale score (mRS) of 4 to 5 after excluding 13 participants with missing day 30 mRS. An additional 9 patients were excluded because of missing 1-year mRS. The final pooled cohort included 715 patients (71.6%) with day 30 mRS 4 to 5. Data were analyzed from July 2019 to January 2022.

Exposures

CLEAR-III participants randomized to intraventricular alteplase vs placebo. MISTIE-III participants randomized to stereotactic thrombolysis of hematoma vs standard medical care.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary outcome was 1-year mRS. Patients were dichotomized into good outcome at 1 year (mRS 0 to 3) vs poor outcome at 1 year (mRS 4 to 6). Multivariable logistic regression models assessed associations between prospectively adjudicated hospital events and 1-year good outcome after adjusting for demographic characteristics, ICH and IVH severity, and trial cohort.

Results

Of 715 survivors, 417 (58%) were male, and the overall mean (SD) age was 60.3 (11.7) years. Overall, 174 participants (24.3%) were Black, 491 (68.6%) were White, and 49 (6.9%) were of other races (including Asian, Native American, and Pacific Islander, consolidated owing to small numbers); 98 (13.7%) were of Hispanic ethnicity. By 1 year, 129 participants (18%) had died and 308 (43%) had achieved mRS 0 to 3. In adjusted models for the combined cohort, diabetes (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.50; 95% CI, 0.26-0.96), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (aOR, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96), severe leukoaraiosis (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.16-0.54), pineal gland shift (aOR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76-0.99]), acute ischemic stroke (aOR, 0.44; 95% CI, 0.21-0.94), gastrostomy (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.17-0.50), and persistent hydrocephalus by day 30 (aOR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.14-0.98) were associated with lack of recovery. Resolution of ICH (aOR, 1.82; 95% CI, 1.08-3.04) and IVH (aOR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.02-4.68) by day 30 were associated with recovery to good outcome. In the CLEAR-III model, cerebral perfusion pressure less than 60 mm Hg (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.13-0.71), sepsis (aOR, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.00-0.80), and prolonged mechanical ventilation (aOR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-1.00 per day), and in MISTIE-III, need for intracranial pressure monitoring (aOR, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.12-0.98), were additional factors associated with poor outcome. Thirty-day event-based models strongly predicted 1-year outcome (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve [AUC], 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83–0.90), with significantly improved discrimination over models using baseline severity factors alone (AUC, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.71-0.80; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among survivors of severe ICH and IVH with initial poor functional outcome, more than 40% recovered to good outcome by 1 year. Hospital events were strongly associated with long-term functional recovery and may be potential targets for intervention. Avoiding early pessimistic prognostication and delaying prognostication until after treatment may improve ability to predict future recovery.

Introduction

Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) prognostication is historically performed on admission, and most models predict short-term outcomes.1,2,3 However, survivors of severe ICH often have initial considerable disability, with a median 90-day modified Rankin Scale score (mRS) of 54 and limited understanding of future recovery. In a meta-analysis of population-based studies, 12% to 39% of ICH survivors gained functional independence beyond 1 year.5 However, most studies describing long-term outcomes in ICH are single-center studies4,6,7,8,9 and rarely describe long-term recovery among ICH survivors with initial severe disability.6 For these patients and their caregivers, long-term prognostication and decision-making have important implications. Therefore, the goal of this study was to describe 1-year outcome trajectories among patients with ICH and severe disability (mRS 4 to 5) at day 30.

Most ICH prognostication models include baseline ICH severity factors,1,2,3,10,11 not accounting for comorbidities, hospital interventions, and complications. Other factors of potential importance include leukoariosis,12 temporal changes in hematoma volume,13 and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) severity.14 IVH grading scales often only incorporate baseline IVH-volume,15,16,17 not accounting for IVH expansion,18 volume reduction, or hydrocephalus,19 which may also impact recovery. We hypothesized that including comorbidities, hospital procedures, medical complications, and temporal hematoma evolution would be significantly associated with improved prediction of 1-year recovery among survivors of ICH and IVH with initial disability compared with models using only baseline characteristics. Understanding the impact of hospital events on long-term recovery among ICH survivors might help identify important targets for interventions to improve ICH outcomes as well as assist in counseling patients and their families regarding potential for future recovery.

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a post hoc longitudinal analysis of prospectively collected participant data from the Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage phase 3 trial (CLEAR-III)20 and the Minimally Invasive Surgery plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation (MISTIE-III) trial.21 Parent trial protocols were approved by the institutional review boards of each trial site, and written informed consent was obtained prior to trial enrollment. This study was approved by our local institutional review board and performed in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Participants and Data Collection

CLEAR-III randomized 500 patients with spontaneous obstructive IVH and small to moderate supratentorial ICH (<30 mL) to receive intraventricular thrombolysis vs placebo.20 MISTIE-III randomized 499 patients with spontaneous large supratentorial ICH (≥30 mL) without obstructive IVH to receive either minimally invasive stereotactic thrombolysis of the hematoma or standard medical treatment.21 Both trials were neutral for primary end point of improved functional outcome at 180 days and 1 year, respectively. However, both trials demonstrated a significant reduction in mortality for the treatment vs control groups at 180 and 365 days. In the current study, we included all patients with ICH and IVH from both trials who survived and had mRS 4 to 5 at day 30.

Measurements

Baseline characteristics included age, sex, race, ethnicity, stroke-related comorbidities, Glasgow Coma Scale score, and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score. Race and ethnicity were included to account for racial or ethnic variances in ICH outcomes and were recorded by trial investigators from review of medical records. Hematoma volumes were measured on noncontrast computed tomography scans performed upon admission, at ICH and IVH stability, at end of treatment, and at day 30 from enrollment in both clinical trials. End of treatment was defined as 24 hours after the last study treatment or placebo in CLEAR-III. In MISTIE-III, end of treatment time was defined as 24 hours after the last study treatment in the surgical arm, and the median time to end of treatment in the surgical arm was used as end of treatment for the medical arm. ICH volumes were calculated using semiautomated planimetry and read by a single neuroradiologist blinded to treatment and outcomes. IVH severity was graded using modified Graeb score in CLEAR-III.15 ICH resolution was defined as 0-mL ICH volume and IVH resolution as either 0–modified Graeb score or 0-mL IVH volume. Midline shift was measured at septum pellucidum and pineal gland. Obstructive hydrocephalus was defined as third ventricular obstruction by hematoma and/or IVH.22 Hydrocephalus was measured on admission and at day 30 via computed tomography using the Evans index in CLEAR-III.23 Leukoaraiosis was graded on admission computed tomography by 2 independent reviewers (N.U. and B.M.H.) using the van Sweiten Scale24 in CLEAR-III. In MISTIE-III, leukoaraiosis was graded on magnetic resonance imaging, using the Fazekas scale.25 Severe leukoaraiosis was defined as van Sweiten Scale score 3 or higher, deep Fazekas scale score 2 to 3, and/or total Fazekas scale score greater than 3. In CLEAR-III, intracranial and cerebral perfusion pressure were measured every 4 hours after extraventricular drain insertion. Only 72 (14.4%) patients in MISTIE-III underwent intracranial pressure monitoring, and these data were excluded. Adverse events and hospital complications were adjudicated centrally during the treatment phase in both trials, and serious adverse events were also assessed by an independent safety committee until the end of follow-up.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was 1-year mRS. Blinded mRS assessments were performed in both trials at days 30, 180, and 365. Secondary outcomes included 1-year mortality, withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, home discharge, and European Quality-of-Life Visual Analog Scale (EQ-VAS) score.26 EQ-VAS score was self-reported by survivors at days 30, 180, and 365.

Statistical Analysis

Patients were dichotomized into 2 groups based on 1-year mRS outcome: good (mRS 0 to 3) vs poor (mRS 4 to 6). Traditionally, mRS 0 to 2 is most closely associated with functional independence27,28 and has been used previously to define good or excellent functional outcome in clinical trials. However, in this analysis, mRS 3 was also classified as good outcome, as both CLEAR-III20 and MISTIE-III21 used this dichotomization to determine treatment efficacy. Additionally, more recent literature suggests that survivors of moderate to severe stroke or ICH survivors with mRS 2 vs mRS 3 report a similar quality of life and have identical direct valuation of their current health status in standard-gamble utility.29,30,31 In addition, considerable interrater disagreement when classifying mRS 2 and 332 suggests that these categories may have similar functional status.

Median time to home, death, and withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment were calculated using time-to-event analyses. mRS and EQ-VAS score trajectories were assessed using mixed-effects linear regression, treating mRS and EQ-VAS scores as outcome, day of assessment (30, 180, and 365) as fixed effects, and patients as random effects.

Factors associated with functional recovery at 1 year were assessed by bivariate analyses comparing all variables between good vs poor 1-year outcome groups in each trial and in the combined cohort. We used the Wilcoxon rank sum test or t test for continuous variables and χ2 test or Fisher exact test for categorical variables. Multivariable logistic regression evaluated the association between variables of interest prior to day 30 and 1-year good outcome for each trial independently and for the combined cohort. Covariates were selected using a significance of P < .20 in bivariate analysis with backward elimination of covariates with P > .10 in final models. Age, sex, race, and ethnicity were chosen a priori as universal confounders and included in models regardless of P value. In models for each independent trial, we adjusted for assignment to treatment group and, for the combined cohort of patients, we adjusted for the trial cohort. Receiver operating characteristic curve and area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) were compared between full models and models using baseline predictors only (ie, age, Glasgow Coma Scale score, ICH volume, presence of IVH [IVH volume for CLEAR-III], and ICH location [deep location for MISTIE-III and thalamic location for CLEAR-III]). Ordinal logistic regression for 1-year mRS was not included in final results as models violated the proportional odds assumption in likelihood-ratio and Brant tests. In log-ordered analyses, covariates were assessed at each mRS threshold and remained similar, with a few covariates demonstrating variability in adjusted odds ratios across different mRS thresholds. Cox proportional hazards regression assessed factors associated with 1-year mortality. All patients surviving to 1 year were censored. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess impact of missing outcomes and data points. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp), and were 2-tailed with significance set at P ≤ .05.

Results

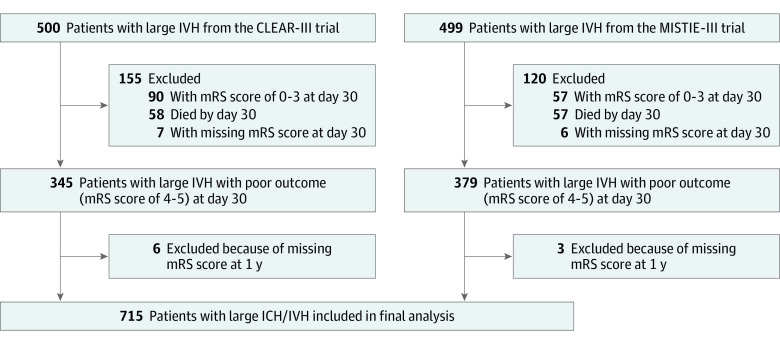

Of 999 patients, 115 (11.5%) died and 147 (14.7%) had good outcome (mRS 0 to 3) at day 30, while 22 (2.2%) lacked mRS data. The final pooled cohort consisted of 715 patients with poor outcome (mRS 4 to 5) at day 30 (218 [29.5%] with mRS 4 and 497 [69.5%] with mRS 5) (Figure 1). The mean (SD) age was 60.3 (11.7) years, and 417 participants (58%) were male. Overall, 174 participants (24.3%) were Black, 491 (68.6%) were White, and 49 (6.9%) were of other races (including Asian, Native American, and Pacific Islander, consolidated owing to small numbers); 98 (13.7%) were of Hispanic ethnicity.

Figure 1. Flow Diagram Showing Selection of Patients in the Study.

CLEAR-III indicates the Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage phase 3 trial; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; MISTIE-III, the Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation phase 3 trial; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score.

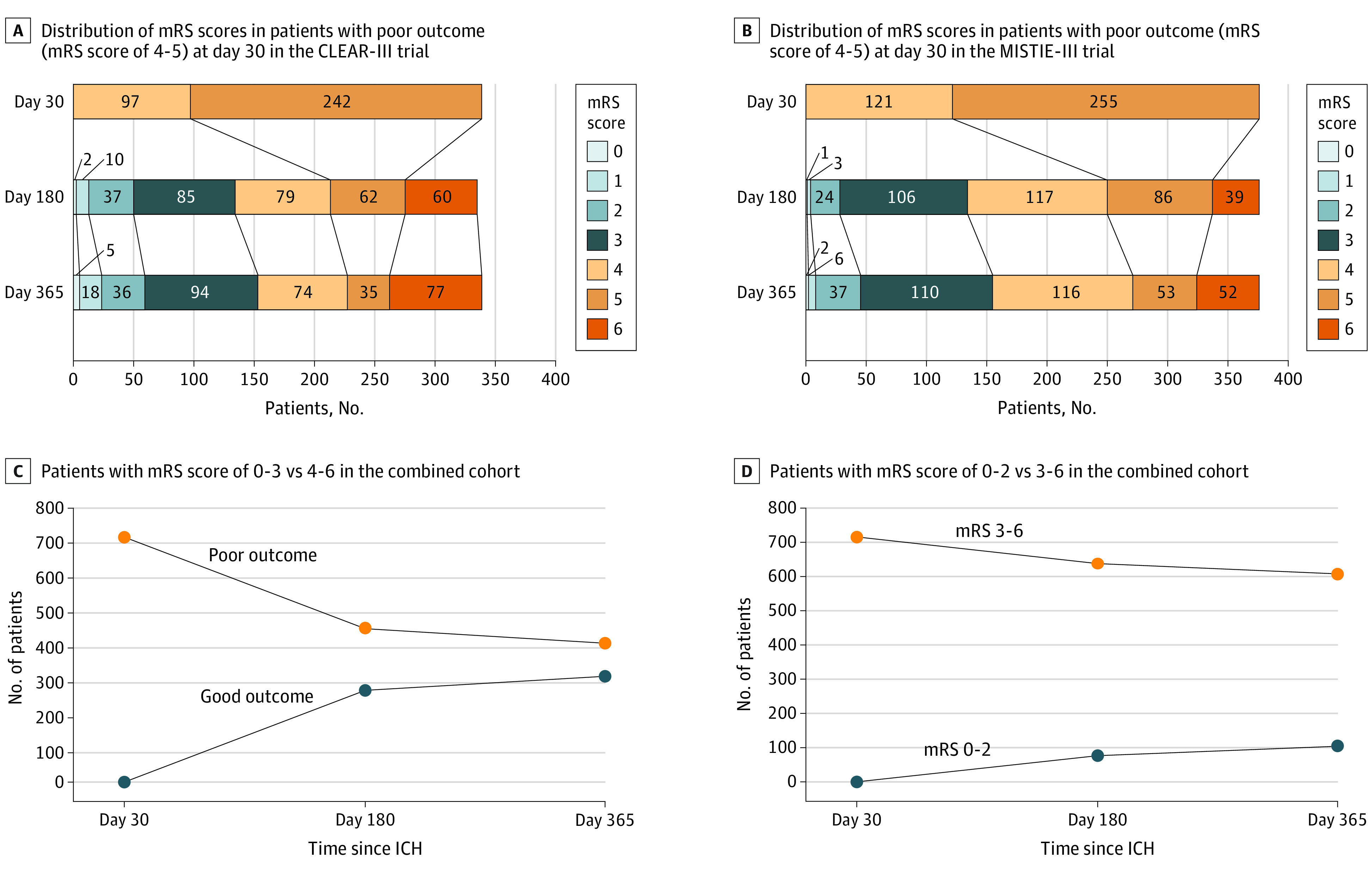

Of these, 308 patients (43%; 153 [45.1%] in CLEAR-III and 155 [41.2%] in MISTIE-III) recovered to good outcome at 1 year. Median (IQR) improvement in mRS was 1 (0-2). A 2-point improvement or greater occurred in 214 patients (30%) and a 1-point improvement occurred in 248 (34.7%) (Figure 2; eFigure 1 in the Supplement).

Figure 2. Ordinal Distribution of Modified Rankin Scale Score (mRS) at Serial Time Points in Patients With Poor Outcomes at Day 30 in the CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III cohorts.

A and B, Grotta bars demonstrate ordinal distribution of mRS at days 30, 180, and 365 in patients in CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III with poor outcomes (mRS 4-5) at day 30. C, Number of patients with mRS 0-3 vs 4-6 at days 180 and 365 in the combined cohort of patients in CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III with poor outcomes (mRS 4-5) at day 30. D, Number of patients with mRS 0-2 vs 3-6 at days 180 and 365 in the combined cohort of patients in CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III with poor outcomes at day 30. CLEAR-III indicates Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage Phase 3 Trial; MISTIE-III, Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation Phase 3 Trial.

By 1 year, 462 patients (64.6%) had returned home at a median (IQR) of 98 (52-302) days postictus. Among 308 patients recovering to good outcome by 1 year, 294 (95.4%) returned home, as did 168 of 407 patients (41%) who had persistent poor outcome at 1 year (eFigures 2 and 3 in the Supplement). Differences by good and poor 1-year outcome groups are shown in Table 1 and eTable 1 in the Supplement.

Table 1. Baseline and 30-Day Characteristics in Patients With Poor Outcome (mRS 4-5) at Day 30 in the CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Cohorts.

| Characteristic | CLEAR-III survivors (n = 339) | MISTIE-III survivors (n = 376) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | P value | No. (%) | P value | |||

| Good 1-y outcome (n = 153) | Poor 1-y outcome (n = 186) | Good 1-y outcome (n = 155) | Poor 1-y outcome (n = 221) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.9 (10.8) | 62.7 (10.2) | <.001 | 56.1 (12.3) | 63.5 (11.7) | <.001 |

| Female | 65 (42.5) | 92 (49.5) | .20 | 61 (39.4) | 80 (36.2) | .53 |

| Male | 88 (57.5) | 94 (50.5) | 94 (60.6) | 141 (63.8) | ||

| Racep | ||||||

| Black | 46 (30.1) | 55 (29.6) | .50 | 29 (18.7) | 44 (20.0) | .37 |

| White | 97 (63.4) | 124 (66.7) | 109 (70.3) | 161 (73.2) | ||

| Othera | 10 (6.5) | 7 (3.8) | 17 (11.0) | 15 (6.8) | ||

| Hispanic ethnicityp | 21 (13.7) | 23 (12.4) | .71 | 23 (14.8) | 31 (14.0) | .83 |

| Medical comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 141 (92.2) | 169 (90.9) | .67 | 150 (96.8) | 218 (98.6) | .22 |

| Congestive heart failure | 6 (3.9) | 9 (4.8) | .68 | 2 (1.3) | 6 (2.7) | .35 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 (8.5) | 20 (10.8) | .49 | 5 (3.2) | 13 (5.9) | .24 |

| Coronary artery disease | 5 (3.3) | 12 (6.5) | .18 | 11 (7.1) | 25 (11.3) | .17 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 17 (11.1) | 22 (11.8) | .84 | 26 (16.8) | 81 (36.7) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 37 (24.2) | 46 (24.7) | .91 | 52 (33.5) | 80 (36.2) | .60 |

| Long-term anticoagulation use | 13 (8.5) | 19 (10.2) | .59 | 7 (4.5) | 13 (5.9) | .56 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 13 (8.5) | 17 (9.1) | .84 | 2 (1.3) | 9 (4.1) | .12 |

| COPD | 4 (2.6) | 14 (7.5) | .04 | 6 (3.9) | 11 (5.0) | .61 |

| Baseline mRSb | ||||||

| 0 | 141 (92.2) | 151 (81.2) | .01 | 151 (97.4) | 201 (91.0) | .01 |

| 1 | 12 (7.8) | 34 (18.3) | 4 (2.6) | 20 (9.0) | ||

| Clinical severity | ||||||

| Enrollment NIHSS score, median (IQR)c | 17 (10-23) | 25 (17-35.5) | <.001 | 18 (15-22) | 20 (17-25) | .02 |

| Enrollment Glasgow Coma Scale score, median (IQR)d | 10 (8-13) | 8 (6-10) | .27 | 11 (9-13) | 10 (8-12) | .01 |

| Radiological characteristics | ||||||

| Admission imaging | ||||||

| Thalamic location | 83 (54.2) | 127 (68.3) | .01 | 2 (1.3) | 10 (4.5) | .08 |

| Deep location | 131 (85.6) | 166 (89.2) | .31 | 90 (58.1) | 166 (75.1) | <.001 |

| Location of lesione | ||||||

| Right hemisphere | 67 (43.8) | 85 (45.7) | .40 | 72 (46.5) | 114 (51.6) | .33 |

| Left hemisphere | 72 (47.1) | 91 (48.9) | 83 (53.5) | 107 (48.4) | ||

| ICH volume, mean (SD), mLf | 8.30 (6.4) | 11.94 (8.1) | <.001 | 41.2 (15.6) | 46.1 (18.2) | .01 |

| IVH volume, mean (SD), mLf | 25.8 (18.0) | 31.6 (21.1) | .01 | 2.0 (5.9) | 2.8 (6.6) | .24 |

| IVH present | 153 (100) | 186 (100) | NA | 80 (51.6) | 168 (76.0) | <.001 |

| Modified Graeb Score, mean (SD)g | 16.4 (4.6) | 16.6 (4.4) | .73 | NA | NA | NA |

| Obstructive hydrocephalus | 116 (75.8) | 163 (87.6) | .01 | 12 (7.7) | 23 (10.4) | .38 |

| Evans index, mean (SD)h | 0.33 (0.04) | 0.35 (0.05) | .001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Septal shift, mean (SD), mmi | 4.0 (2.6) | 4.7 (3.0) | .05 | 4.2 (2.26) | 4.5 (2.83) | .27 |

| Pineal shift, mean (SD), mmi | 1.4 (1.9) | 1.7 (2.1) | .17 | 2.3 (2.01) | 2.7 (2.08) | .14 |

| vSS score, median (IQR)j | 2.0 (0-3.5) | 0.0 (0-2.0) | <.001 | NA | NA | NA |

| Fazekas scale score, median (IQR)j | NA | NA | NA | 2.0 (1-3) | 3.0 (2-4) | <.001 |

| Severe leukoariosisj | 17 (11.1) | 54 (29) | <.001 | 22 (16.1) | 88 (45.4) | <.001 |

| Stability (S) imaging | ||||||

| Stability ICH volume, mean (SD), mL | 9.8 (7.7) | 11.5 (8.2) | .05 | 45.0 (15.8) | 51.2 (16.8) | <.001 |

| Stability IVH volume, mean (SD), mL | 23.9 (17.3) | 28.3 (19.1) | .03 | 2.0 (4.8) | 3.4 (6.6) | .03 |

| EOT imaging | ||||||

| EOT ICH volume, mean (SD), mL | 7.6 (6.3) | 11.1 (8.2) | <.001 | 27.5 (19.0) | 32.3 (21.8) | .02 |

| EOT IVH volume, mean (SD), mL | 10.8 (12.0) | 14.8 (15.1) | .01 | 1.2 (3.2) | 2.1 (4.2) | .02 |

| EOT removal of >85% IVH | 29 (19.0) | 18 (9.7) | .01 | 54 (34.8) | 63 (28.5) | .19 |

| Day 30 imaging characteristicsk | ||||||

| ICH volume, mean (SD), mLk | 0.66 (1.57) | 1.63 (2.7) | <.001 | 7.26 (10.9) | 8.61 (12.4) | .29 |

| Modified Graeb score, mean (SD)g | 0.62 (1.25) | 0.99 (1.31) | .01 | |||

| Resolution of IVHk,l | 111 (72.5) | 98 (52.7) | <.001 | 118 (92.9) | 159 (88.8) | .23 |

| Resolution of ICHk,l | 100 (66.7) | 79 (45.7) | <.001 | 68 (46.3) | 80 (39.4) | .20 |

| Persistent hydrocephalusk | 11 (7.2) | 29 (16.8) | .01 | 7 (4.8) | 17 (8.4) | .19 |

| Evans index, mean (SD)h | 0.30 (0.05) | 0.32 (0.05) | .001 | NA | NA | NA |

| In-hospital events in first 30 d | ||||||

| Admission systolic blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | 191.2 (38.0) | 196.7 (39.4) | .20 | 183.0 (30.7) | 183.6 (34.4) | .87 |

| ICP monitoring | 153 (100) | 186 (100) | NA | 15 (9.7) | 37 (16.7) | .05 |

| % ICP readings >20 mm Hg, mean (SD), % | 9.26 (11.8) | 9.31 (12.3) | .97 | NA | NA | NA |

| % CPP readings <60 mm Hg, mean (SD), % | 1.1 (2.70) | 1.3 (3.30) | .49 | NA | NA | NA |

| Any ICP reading >20 mm Hg | 109 (71.7) | 130 (69.9) | .72 | NA | NA | NA |

| Any ICP reading >30 mm Hg | 56 (36.8) | 47 (25.3) | .02 | NA | NA | NA |

| Any CPP reading <60 mm Hg | 26 (17.2) | 52 (28.0) | .02 | NA | NA | NA |

| Mechanical ventilation duration, mean (SD), d | 6.6 (7.4) | 11.3 (10.4) | <.001 | 3.8 (5.4) | 7.5 (0.04) | <.001 |

| ICU days, mean (SD) | 15.7 (6.4) | 19.7 (6.9) | <.001 | 12.0 (7.7) | 15.7 (7.9) | <.001 |

| Adverse events | ||||||

| Ischemic stroke | 14 (9.2) | 25 (13.4) | .22 | 17 (11.0) | 36 (16.3) | .14 |

| New symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage | 4 (2.6) | 5 (2.7) | .97 | 2 (1.3) | 3 (1.4) | .96 |

| Any cardiac adverse eventm | 11 (7.2) | 19 (10.2) | .33 | 17 (11.0) | 25 (11.3) | .92 |

| Cardiac arrest | 0 (0) | 2 (1.1) | .20 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | .40 |

| ARDS | 2 (1.3) | 5 (2.7) | .37 | 2 (1.3) | 2 (0.9) | .72 |

| Pulmonary edema | 6 (3.9) | 15 (8.1) | .12 | 3 (1.9) | 4 (1.8) | .93 |

| Any pulmonary adverse eventm | 49 (32.0) | 82 (44.1) | .02 | 46 (29.7) | 80 (36.2) | .19 |

| Acute kidney injury | 11 (7.2) | 22 (11.8) | .15 | 5 (3.2) | 7 (3.2) | .98 |

| Venous thromboembolism | 14 (9.2) | 23 (12.4) | .35 | 14 (9.0) | 20 (9.0) | >.99 |

| Any infection | 73 (47.7) | 110 (59.1) | .04 | 46 (29.7) | 78 (35.3) | .25 |

| Urinary tract infection | 21 (13.7) | 27 (14.5) | .84 | 18 (11.6) | 18 (8.1) | .26 |

| Central nervous system infection | 13 (8.5) | 21 (11.3) | .39 | 2 (1.3) | 5 (2.3) | .49 |

| Pneumonia | 44 (28.8) | 69 (37.1) | .11 | 30 (19.4) | 53 (24.0) | .29 |

| Sepsis | 2 (1.3) | 6 (3.2) | .25 | 4 (2.6) | 4 (1.8) | .61 |

| Interventions and surgical procedures in first 30 d | ||||||

| Trial treatment assignmentn | 69 (45.1) | 99 (53.2) | .14 | 79 (51.0) | 115 (52.0) | .84 |

| Ventriculoperitoneal shunt | 24 (15.7) | 29 (15.6) | .98 | 3 (1.9) | 8 (3.6) | .34 |

| Gastrostomy tube placement | 35 (22.9) | 98 (52.7) | <.001 | 31 (20.0) | 106 (48.0) | <.001 |

| EQ-VAS score, mean (SD)o | ||||||

| Day 30 | 43.2 (24.7) | 29.0 (23.3) | <.001 | 46.6 (24.0) | 31.4 (21.7) | <.001 |

| Day 180 | 67.6 (20.4) | 46.6 (24.3) | <.001 | 66.3 (19.2) | 49.3 (23.6) | <.001 |

| Day 365 | 70.5 (19.2) | 55.5 (21.6) | <.001 | 70.9 (17.2) | 53 (21.7) | <.001 |

| Discharge disposition | ||||||

| Home | 5 (3.3) | 2 (1.1) | <.001 | 15 (9.7) | 7 (3.2) | <.001 |

| Rehabilitation facility | 73 (47.7) | 41 (22.4) | 88 (56.8) | 87 (39.4) | ||

| Short-term care facility | 65 (42.5) | 101 (54.3) | 35 (22.6) | 74 (33.5) | ||

| Long-term care facility | 10 (6.5) | 39 (21.2) | 17 (11.0) | 53 (24.0) | ||

| No. of patients eventually discharged to home | 141 (92.2) | 60 (32.2) | <.001 | 153 (98.7) | 108 (48.9) | <.001 |

| Time to home, median (IQR), d | 64 (44-109) | 104 (64-154) | <.001 | 59 (41-84) | 93 (55-166) | <.001 |

| Time spent at home after ictus, median (IQR), d | 295 (252-323) | 224 (140.5-283.5) | <.001 | 307 (283-323) | 253 (147.5-301.5) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome; CLEAR-III, Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage Phase 3 Trial; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; EOT, end of treatment; EQ-VAS, European Quality of Life Scale Visual Analog Scale; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; ICP, intracranial pressure; ICU, intensive care unit; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; MISTIE-III, Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation Phase 3 Trial; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; NA, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; vSS, van Sweiten Scale.

Includes Asian, Native American, and Pacific Islander, consolidated owing to small numbers.

Scores range from 0 to 6, with higher scores indicating severe disability and death.

Scores range from 0 to 42; higher scores correlate with higher stroke severity. NIHSS score was recorded at study enrollment and was not available for 27 patients in CLEAR-III.

Scores range from 3 to 15, with lower scores indicating coma; Glasgow Coma scale score readings were recorded at study enrollment.

Hemispheric side of lesion was missing in 24 patients in CLEAR-III. Of these, 17 had a primary IVH or periventricular bleed and 1 had infratentorial bleed; thus 6 individuals with a hemispheric basal ganglia hemorrhage had missing documentation on side of lesion.

ICH and IVH volume on admission were not available in 14 patients in MISTIE-III and 2 in CLEAR-III.

Scores range from 0 to 32, with higher scores indicating higher IVH volumes.

Ratio of maximal width of anterior horns of lateral ventricles to the maximal width of calvaria at level of Foramen of Monroe; ratio >0.3 suggests hydrocephalus.

Midline shift parameters were not available in 79 patients in CLEAR-III and 85 in MISTIE-III.

vSS: computed tomography grading scale for leukoaraiosis ranging from 0 to 4 (used in CLEAR-III). Fazekas scale: magnetic resonance imaging grading scale from leukoaraiosis ranging from 0 to 6, combining deep and periventricular regions (used in MISTIE-III, missing in 45 patients). Severe leukoaraiosis was defined as a total Fazekas score >3 or deep Fazekas score 2 to 3 for MISTIE-III or vSS ≥3 for CLEAR-III.

Day 30 computed tomography IVH resolution data were missing in 13 patients in CLEAR-III and 70 in MISTIE-III; day 30 computed tomography ICH volumes, ICH resolution, and hydrocephalus data were missing in 16 patients in CLEAR-III and 26 in MISTIE-III.

Resolution of IVH defined as modified Graeb score of 0 or IVH volume 0 mL and resolution of ICH defined as ICH volume of 0 mL on day 30 computed tomography scan.

Defined as any serious adverse events involving the respiratory system and cardiovascular system in the prospectively adjudicated event reporting of the 2 trials.

Defined as intraventricular thrombolysis with tissue plasminogen activator in CLEAR-III and MISTIE surgery in MISTIE-III.

In addition to 129 patients who died by 1 year, EQ-VAS score was also not reported by 70 CLEAR-III and 74 MISTIE-III patients at either day 30 or day 365.

Race and ethnicity data were included to account to racial and ethnic variances in ICH outcomes. Race and ethnicity were collected by trial investigators from review of medical records.

Trajectories of Recovery

mRS Score Trajectories

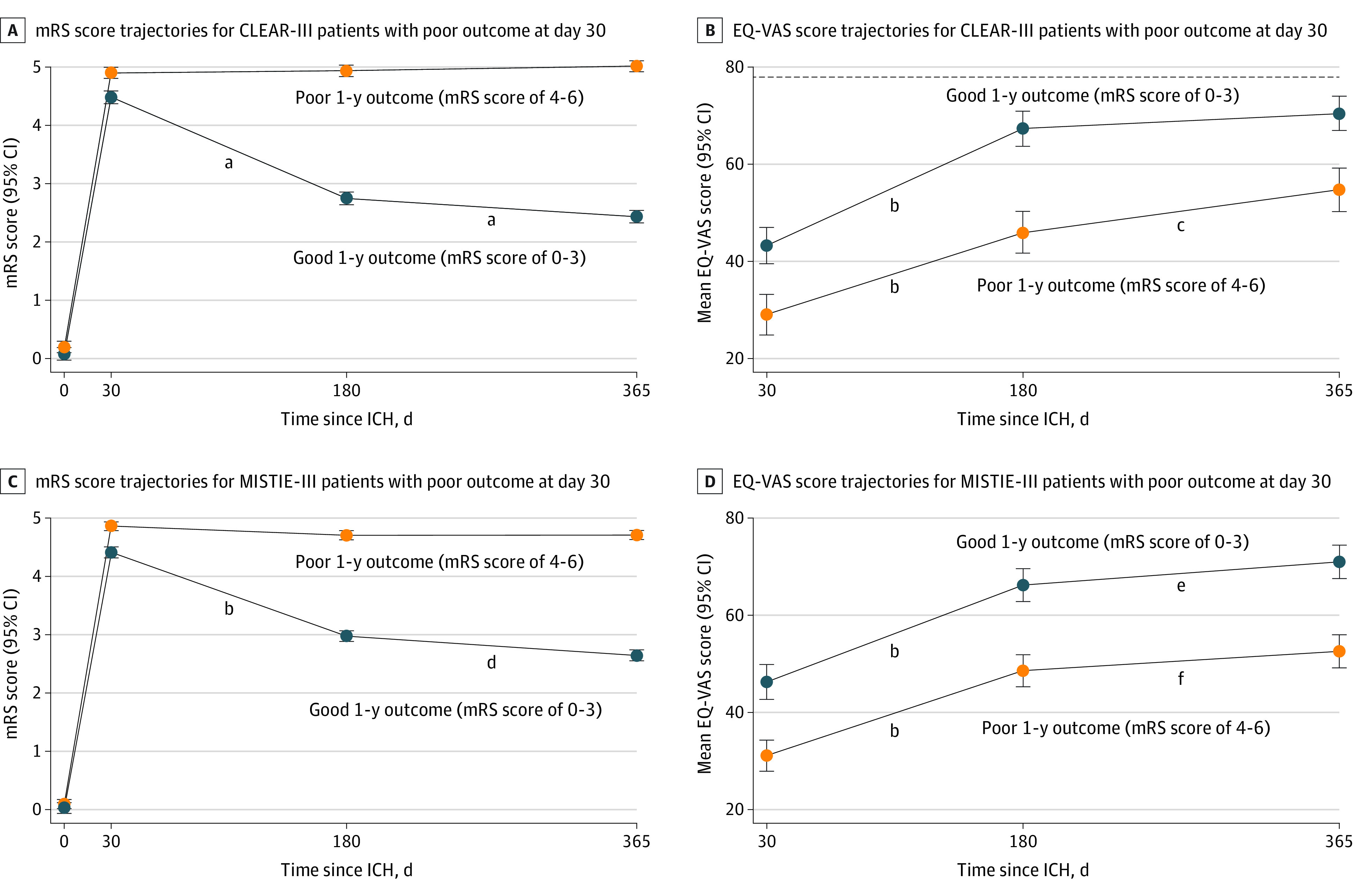

Day 30 and 1-year mRS were missing in 13 and 9 patients, respectively. Patients lacking mRS data were younger, did not have diabetes or hyperlipidemia, and were less likely to have chronic hydrocephalus but were more likely to have new symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage within the first 30 days (eTable 2 in the Supplement). Adjusted linear predictions of mRS over 1 year for good vs poor 1-year outcome groups are shown in Figure 3. For good 1-year outcome group models, improvement in mean mRS was significant between all time points (day 30 vs day 180; day 180 vs day 365) in mixed linear models. Good 1-year outcome groups had a 2-point improvement in mean mRS (eFigure 4 in the Supplement).

Figure 3. Linear Prediction of Modified Rankin Scale Score (mRS) and European Quality of Life Scale (EuroQol) Visual Analog Scale (EQ-VAS) Score Trajectories for Patients With Poor Outcomes at Day 30 in the CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III cohorts.

A and B, Adjusted linear predictions of trajectories of mean mRS (n = 339) and mean EQ-VAS (n = 297) scores for patients with good vs poor outcomes at 1 year in CLEAR-III. C and D, Adjusted linear predictions of trajectories of mean mRS (n = 376) and mean EQ-VAS score (n = 358) for patients with good vs poor outcomes at 1 year in MISTIE-III. B and D, Dotted line indicates mean age-matched US population norm for EQ-VAS score. CLEAR-III indicates Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage Phase 3 Trial; ICH, intracerebral hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; MISTIE-III, Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation Phase 3 Trial.

aP < .001.

bDay 30 vs day 180, P < .001.

cDay 180 vs day 365, P = .002.

dDay 180 vs day 365, P < .001.

eDay 180 vs day 365, P = .02.

fDay 180 vs day 365, P = .05.

EQ-VAS Score Trajectories

In addition to 129 patients (18%) who died, 77 of 586 survivors (13.1%) did not report EQ-VAS score at follow-up (day 180 and/or day 365). These patients were more likely to have higher baseline National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score, lower Glasgow Coma Scale score, severe leukoaraiosis, left-hemispheric lesions, and a worse clinical course with longer ventilatory support, need for gastrostomy, and persistent poor outcomes (eTable 3 in the Supplement). In mixed linear models, EQ-VAS score was significantly lower in the poor 1-year outcome group throughout follow-up, but both groups were associated with a statistically significant upward trajectory in EQ-VAS scores (Figure 3).

Multivariable Logistic Regression Models: 1-Year Outcome

Covariates associated with recovery to good outcome in both trials are shown in Table 2. In the combined cohort of patients with ICH and IVH and poor outcome at day 30, diabetes (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.50; 95% CI, 0.26-0.96), National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score (aOR per 1 point, 0.93; 95% CI, 0.90-0.96), severe leukoaraiosis (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.16-0.54), pineal gland shift (aOR per 1 mm, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.76-0.99), persistent hydrocephalus at day 30 (aOR, 0.37; 95% CI, 0.14-0.98), new ischemic stroke (aOR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.21-0.96), and gastrostomy (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.17-0.50) were associated with lack of recovery. Radiographic ICH (aOR, 1.83; 95% CI, 1.08-3.08) and IVH (aOR, 2.20; 95% CI, 1.03-4.70) resolution by day 30 were associated with recovery to good outcome after adjusting for baseline ICH and IVH characteristics, demographic characteristics, and trial cohort. In the CLEAR-III model, cerebral perfusion pressure less than 60 mm Hg (aOR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.13-0.71), sepsis (aOR, 0.05; 95% CI, 0.00-0.80), prolonged mechanical ventilation (aOR, 0.96; 95% CI, 0.92-1.00, per -day), and in MISTIE-III, need for intracranial pressure monitoring (aOR, 0.35; 95% CI, [0.12-0.98]) were additional factors associated with lack of recovery to good outcome. The day 30 model for the combined cohort (AUC, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.90) showed significantly improved discrimination for 1-year outcome compared with the baseline model (AUC, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.71-0.80; P < .001). The CLEAR-III day 30 model (AUC, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.86-0.93) showed improved discrimination compared with the baseline model (AUC, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.75-0.85; P < .001). In MISTIE-III, the day 30 model (AUC, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.83-0.91; P < .001) vs the baseline model (AUC, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.74-0.84; P < .001) (eFigure 5 in the Supplement). Notably, 286 patients were excluded in the combined model because of missing data points. A comparison of these patients is included in eTable 4 in the Supplement.

Table 2. Multivariable Logistic Regression of Factors Associated With Good Outcome at 1 Year Among Patients With Large Intracerebral Hemorrhage (ICH) and Intraventricular Hemorrhage (IVH) and Poor Outcome (mRS 4-5) at Day 30.

| Factora | aOR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Survivors with large IVH in CLEAR-III (n = 292) | ||

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Age, per y | 0.93 (0.90-0.97) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 4.52 (2.12-9.63) | <.001 |

| Racei | ||

| Black | 1.10 (0.47-2.57) | .83 |

| White | [Reference] | NA |

| Otherb | 1.17 (0.25-5.50) | .85 |

| Hispanic ethnicityi | 0.82 (0.31-2.20) | .70 |

| Admission IVH volume (per 1-mL increase) c | 0.95 (0.93-0.97) | <.001 |

| Stability ICH volume (per 1-mL increase) | 0.93 (0.88-0.99) | .02 |

| Thalamic location of hematoma | 0.26 (0.11-0.64) | .003 |

| NIHSS score (per 1-point increase)d | 0.96 (0.93-0.99) | .02 |

| Leukoaraiosis (vSS score: per 1-point increase)e | 0.64 (0.50-0.82) | <.001 |

| 30-d In-hospital events | ||

| Intraventricular thrombolytic therapy | 0.45 (0.23-0.89) | .02 |

| Resolution of IVH by day 30f | 2.66 (1.26-5.63) | .011 |

| Resolution of ICH by day 30f | 3.84 (1.50-9.84) | .005 |

| Any CPP reading <60 mm Hg | 0.30 (0.13-0.71) | .006 |

| Any ICP reading >30 mm Hg | 1.80 (0.85-3.84) | .13 |

| Sepsis | 0.05 (0.004-0.804) | .03 |

| Need for gastrostomy placement | 0.38 (0.19-0.78) | .008 |

| Mechanical ventilation duration, per d | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) | .07 |

| Survivors with large ICH in MISTIE-III (n = 330) | ||

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Age, per y | 0.90 (0.88-0.93) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 1.40 (0.76-2.59) | .28 |

| Racei | ||

| Black | 0.89 (0.41-1.91) | .76 |

| White | [Reference] | NA |

| Otherb | 2.34 (0.80-6.84) | .12 |

| Hispanic ethnicityi | 1.09 (0.47-2.54) | .85 |

| Presence of IVH | 0.31 (0.16-0.60) | <.001 |

| Deep location of hematoma | 0.12 (0.05-0.27) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.35 (0.17-0.69) | .003 |

| NIHSS score (per 1-point increase)d | 0.94 (0.89-0.99) | .02 |

| Severe leukoaraiosise | 0.28 (0.14-0.55) | <.001 |

| Stability ICH volume (per 1-mL increase) | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) | .048 |

| 30-d In-hospital events | ||

| Need for ICP monitoring | 0.35 (0.12-0.98) | .05 |

| Need for gastrostomy tube | 0.40 (0.21-0.78) | .007 |

| MISTIE treatment assignment | 1.04 (0.57-1.91) | .89 |

| ICH and IVH survivors (combined cohorts; n = 429) | ||

| Baseline characteristics | ||

| Age, per y | 0.92 (0.90-0.95) | <.001 |

| Male sex | 1.28 (0.76-2.14) | .35 |

| Racei | ||

| Black | 0.69 (0.37-1.30) | .25 |

| White | [Reference] | NA |

| Otherb | 1.22 (0.42-3.55) | .71 |

| Hispanic ethnicityi | 0.75 (0.38-1.50) | .42 |

| Stability ICH volume (per 1-mL increase) | 0.96 (0.94-0.98) | .001 |

| Admission IVH volume (per 1-mL increase)c | 0.98 (0.96-1.00) | .06 |

| Deep location of hematoma | 0.09 (0.04-0.22) | <.001 |

| Type 2 diabetes | 0.50 (0.26-0.96) | .04 |

| NIHSS score (per 1-point increase)d | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) | <.001 |

| Severe leukoariosise | 0.30 (0.16-0.54) | <.001 |

| Pineal gland shift (per 1-mm increase)g | 0.87 (0.76-0.99) | .04 |

| 30-d In-hospital events | ||

| Resolution of ICH by day 30f | 1.82 (1.08-3.04) | .02 |

| Resolution of IVH by day 30f | 2.19 (1.02-4.68) | .04 |

| Persistent hydrocephalus at day 30f | 0.37 (0.14-0.98) | .04 |

| Ischemic stroke | 0.45 (0.21-0.96) | .04 |

| Need for gastrostomy | 0.30 (0.17-0.50) | <.001 |

| Trial cohort (MISTIE-III vs CLEAR-III) | 0.94 (0.33-2.62) | .90 |

Abbreviations: CLEAR-III, Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage Phase 3 Trial; CPP, cerebral perfusion pressure; CT, computed tomography; FS, Fazekas Scale; ICP, intracranial pressure; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; MISTIE-III, Minimally Invasive Surgery Plus Alteplase for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation Phase 3 Trial; mRS, modified Rankin Scale score; NA, not applicable; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; vSS, van Sweiten Scale.

Covariates selected based on a significance of P < .20 in the bivariate regression.

Includes Asian, Native American, and Pacific Islander, consolidated owing to small numbers.

Admission IVH volume was not available in 2 patients in CLEAR-III and 13 in MISTIE-III.

NIHSS score was missing in 26 patients in CLEAR-III.

van Swieten scale (vSS): CT grading scale for leukoaraiosis severity ranging from 0 to 4 (used in CLEAR-III); FS score: magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) grading scale from leukoaraiosis severity ranging from 0 to 6, combining deep and periventricular regions (used in MISTIE-III). Severe leukoaraiosis defined as total FS score >3 or deep FS score 2 to 3 for MISTIE-III and vSS ≥3 for CLEAR-III; FS score was missing in 45 patients in MISTIE-III.

Resolution of ICH was defined as ICH volume of 0 mL on day 30 CT; resolution of IVH defined as modified Graeb score of 0 on day 30 CT; day 30 CT IVH resolution was not available in 83 patients, and ICH resolution and hydrocephalus were not available in 42 patients.

Pineal gland shift data were not available in 79 patients in CLEAR-III and 85 in MISTIE-III.

Pineal gland shift data were not available in 79 patients in CLEAR-III and 85 in MISTIE-III.

Race and ethnicity data were included to account form racial and ethnic variances in ICH outcomes. Race and ethnicity were collected by trial investigators from review of medical records.

Multivariable logistic regression for other mRS dichotomizations, including recovery to mRS 0 to 2 and mRS improvement of 1-point or greater, revealed similar covariates (eTables 5-7 in the Supplement), with a notable exception of ICH resolution by day 30, which was independently associated with recovery to mRS 0 to 3 but not with mRS 0to 2.

1-Year Mortality

Seventy-seven patients in CLEAR-III (22.7%) and 52 in MISTIE-III (13.8%) with poor day 30 outcome died by 1 year (total deaths = 129 [18%]). Median (IQR) time to death was 85 (48-180) days postictus. Index ICH led to delayed deaths in 19 patients (15%). Twelve deaths (9%) occurred because of other neurological events (brain death, herniation, recurrent hemorrhage, or hydrocephalus) and 98 (76%) because of nonneurological causes. Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment occurred in 40 patients (31%) at a median (IQR) time of 73 (25-188) days after day 30.

In Cox proportional hazards regression for the combined cohort, 1-year mortality was associated with age (hazard ratio [HR] per year, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03-1.08), female sex (HR male, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.43-0.94), diabetes (HR, 1.75; 95% CI, 1.09-2.79), severe leukoaraiosis (HR, 1.94; 95% CI, 1.30-2.92), pulmonary edema (HR, 3.04; 95% CI, 1.44-6.42), sepsis (HR, 2.88; 95% CI, 1.02-8.09), and lack of IVH resolution (HR, 0.52; 95% CI, 0.30-0.91) by day 30 after adjusting for ICH severity (eTable 8 in the Supplement).

Sensitivity Analyses

In sensitivity analyses conducted for missing outcomes, models were largely unchanged after accounting for patients lacking mRS data (eTables 9 and 10 in the Supplement). Most covariates were unchanged in sensitivity analysis for the combined model after including all patients, except for IVH volume and pineal shift, which were no longer statistically significant (eTable 11 in the Supplement). Similarly, covariates in the Cox regression model for 1-year mortality were also unchanged in sensitivity analysis (eTable 12 in the Supplement) (eFigures 6 and 7 in the Supplement).

Discussion

In this post hoc analysis of patients with ICH and IVH and initial severe disability, more than 40% of patients recovered to good outcome by 1 year. Prediction of long-term functional recovery was significantly associated with improvement after inclusion of more granular baseline characteristics (ie, diabetes, leukoaraiosis, IVH volume, and pineal shift) and hospital events, including cerebral hypoperfusion, ischemic stroke, sepsis, persistent hydrocephalus, need for supportive interventions (mechanical ventilation and gastrostomy), and hematoma evolution. Significant reduction in hematoma and IVH volumes in the first month were strongly associated with long-term functional recovery, highlighting the importance of minimally invasive interventions to reduce blood volume.

The combined cohort experienced higher rates of good 1-year outcome than previously reported,2,33 despite the inclusion of only patients with high-severity ICH and IVH. Outcomes from these clinical trials may be biased by rigid exclusion criteria, including baseline Glasgow Coma Scale score less than 4, fixed pupils, infratentorial extension, and baseline mRS greater than 1, limiting generalizability. However, outcomes were less impacted by early withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment, which occurred in only 88 of 999 patients (8.8%) in the first month, compared with 20% to 30% in prior studies.10,33 Patients with ICH who are maximally treated have favorable outcomes at a similar rate,10 highlighting the possible negative impact of early pessimistic prognostication on future recovery.34

Most ICH outcome prognostication scales only include admission characteristics and typically predict short-term outcomes.2,3 Previous prediction scores have not integrated hospital events and therapeutic interventions that also impact outcome. Thus, existing scales have lower discrimination for 1-year outcome among patients with ICH who receive maximal treatment.10 Hence, by delaying prognostication until after the treatment phase and incorporating hospital events, our study provides a novel approach to ICH outcome prognostication, emphasizing the need to promote maximal treatment of patients with ICH and IVH. These findings also identify targets for therapeutic interventions in the short term to promote long-term recovery.

Among comorbidities, type 2 diabetes was associated with persistent poor 1-year outcome. No associations were noted between diabetes and short-term functional outcomes in prior community-based stroke registry studies,35,36 but diabetes is associated with long-term mortality37 and long-term functional decline among ICH survivors.38 Diabetes is associated with recurrent ischemic stroke in ICH survivors,39 which may explain the association between ICH and poor long-term outcome. Severe leukoaraiosis was also associated with persistent poor outcome at 1 year in this analysis, further supporting its association with short-term outcomes after ICH.12,40

Among hospital events, need for intracranial pressure monitoring (MISTIE-III) and cerebral perfusion pressure less than 60 mm Hg (CLEAR-III) were associated with persistent poor outcome. In CLEAR-III, any cerebral perfusion pressure less than 60 mm Hg negatively influenced functional recovery41 even though intracranial pressure elevation did not, similar to findings from a prior MISTIE-III analysis, which also reported cerebral perfusion pressure as an independent predictor of poor long-term outcome.42 This suggests that cerebral hypoperfusion may be more critical than intracranial hypertension, raising concerns about aggressive blood pressure reduction in patients with large hematomas.43,44,45 Ischemic stroke in the first month was also associated with lack of functional recovery, which is associated with leukoaraiosis, high-volume hemorrhage, and rapid blood-pressure reduction.44,45 Thus cerebral ischemic injury prior to and following ICH appears to be an important contributor to persistent poor long-term outcomes among survivors38 and may be driven by underlying comorbidities (eg, diabetes and leukoaraiosis) and secondary injury due to cerebral hypoperfusion.46

Gastrostomy and prolonged ventilatory support were independently associated with poor 1-year outcome, even after adjusting for ICH and IVH severity. This may suggest that other factors driving the need for prolonged supportive care, such as nosocomial infections,47 may also contribute to poor functional recovery. Specifically, need for supportive interventions may indicate impaired protective (eg, cough and gag) reflexes, which are associated with increased long-term mortality in general stroke populations.48 Among medical complications, sepsis and pulmonary edema were associated with persistent poor long-term outcome and reduced long-term survival after ICH, confirming that hospital complications impact recovery well beyond hospital discharge.49,50,51,52

Association of intraventricular thrombolysis with persistent poor outcomes in CLEAR-III likely reflects a higher proportion of patients with mRS 5 in the alteplase group (alteplase, 17% vs placebo, 9%; P = .007).20 However, after adjusting for alteplase use, complete resolution of IVH and ICH by day 30 was independently associated with functional recovery at 1 year. IVH clearance was also associated with improved long-term survival. These findings support associations between hematoma volume reduction and 180-day good outcomes in both CLEAR-III20 and MISTIE-III,21 consistent with the established effects of alteplase on mortality and supporting the need for continued efforts to develop interventions that will assist in timely reduction of IVH and ICH volumes.

Despite a significantly lower quality of life reported among patients who did not functionally recover by 1 year, there was a statistically significant upward trajectory in EQ-VAS scores of these patients throughout the one-year follow-up period.53 Additionally, nearly half of the survivors with persistent poor 1-year outcome were able to return home. These findings emphasize that an acceptable quality of life may be achieved even among survivors who do not make good functional recovery. The strengths of our study include a large cohort of prospectively monitored patients with high-severity ICH or IVH, well-defined inclusion criteria, preestablished time points for neuroimaging, adjudicated and prospectively collected hospital events, prolonged follow-up, and serial blinded mRS and quality-of-life assessments.

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study warranting discussion. First, generalizability of the findings may be limited owing to the strict inclusion criteria of the clinical trials. Second, testing associations between a large number of covariates and 1-year outcomes may have been impacted by type I error. While we demonstrated that 30-day event-based models performed better than admission criteria–based models, we acknowledge that their performance was not compared with that of models using factors at other time points between admission and day 30. Also, given that patients were enrolled over an 8-year period, temporal advances in ICH management could have influenced outcomes through the study period. Additionally, combining CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III cohorts has limitations owing to significant differences in patient characteristics and trial interventions. However, to address this we adjusted for trial cohort in the combined model and created separate models for each trial. Missing variables led to exclusion of many patients in the multivariable analysis, especially for the combined cohort. Thus, the analysis may have been affected by an omitted-variable bias. However, in sensitivity analysis, most covariates remained unchanged after including all patients. Similarly, 2.2% of patients were lost to follow-up owing to missing mRS data. Quality-of-life data may have been impacted by a reporting bias, given that patients that did not report EQ-VAS score, had a worse clinical course, and had more left hemispheric lesions, suggesting that aphasia and poor functional and cognitive recovery may have impaired their ability to self-report quality of life. Ascertainment of leukoaraiosis in CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III used different methods; however, significant association between van Sweiten Scale and Fazekas scale has been reported previously.54,55 Owing to these limitations, models from this post hoc analysis of clinical trials need independent prospective validation in external data sets.

Conclusions

In this cohort study of patients with high-severity ICH and IVH enrolled in clinical trials, nearly half of survivors with poor outcome in the early phase recovered to a good functional outcome by 1 year. Discrimination of an upward trajectory compared with stable or downward trajectory was associated with significant improvement when including factors not included in traditional models, such as preexisting conditions, hospital events, and responses to therapy. These findings support longer evaluation periods to provide better communication about long-term recovery after severe ICH and IVH and identify important targets of improvement in ICH care that may enhance long-term recovery.

eTable 1. Bivariate Analysis comparing good versus poor one-year outcome groups in the combined cohort of CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Patients

eTable 2. Differences between patients included in the analysis versus those excluded due to missing mRS at day-30 and/or day-365

eTable 3. Differences between patients that reported EQ-VAS versus those that did not report EQ-VAS

eTable 4. Differences between patients included and excluded from combined multivariable logistic regression model for primary outcome (mRS 0-3) due to missing data

eTable 5. Multivariable Logistic Regression Models for Factors Associated with Recovery to mRS 0-2 among Patients with mRS 3-5 at day-30

eTable 6. Multivariable Logistic Regression Model for Factors Associated with Recovery of at least 1-point in mRS among Patients with mRS 1-5 at day-30

eTable 7. Multivariable Logistic Regression Models Using Other mRS-Dichotomizations in ICH/IVH survivors with mRS 4-5 at day-30

eTable 8. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models Predicting One-Year All-Cause Mortality Among ICH/IVH survivors with Poor Day-30 Outcome

eFigure 1. Distribution of patients in each day-365 mRS category for all CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Survivors at day-30

eFigure 2. Home Discharge and Discharge Disposition Over One-Year

eFigure 3. Time to Home among CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Patients with Poor Outcome at Day-30

eFigure 4. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) trajectories among patients with mRS 4 versus mRS 5 at day-30

eFigure 5. Receiver Operator Curves (ROC) and Area-Under-the-Curve (AUC) for day-30 models versus baseline models

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis for missing mRS at day-30

eTable 10. Sensitivity Analysis for missing mRS at one-year mRS

eTable 11. Sensitivity Analysis for missing data-points in Combined Model for Good One-Year Outcome

eTable 12. Sensitivity Analysis for missing data-points in Cox Regression Model for One-Year Mortality

eFigure 6. Sensitivity Analysis for mRS Trajectories

eFigure 7. Sensitivity Analysis for EQ-VAS Trajectories

References

- 1.Hemphill JC III, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32(4):891-897. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.32.4.891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rost NS, Smith EE, Chang Y, et al. Prediction of functional outcome in patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage: the FUNC score. Stroke. 2008;39(8):2304-2309. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.512202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weimar C, Benemann J, Diener HC, German Stroke Study Collaboration . Development and validation of the Essen intracerebral haemorrhage score. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77(5):601-605. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.081117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Øie LR, Madsbu MA, Solheim O, et al. Functional outcome and survival following spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: A retrospective population-based study. Brain Behav. 2018;8(10):e01113. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJM. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9(2):167-176. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70340-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee L, Lo YT, See AAQ, Hsieh PJ, James ML, King NKK. Long-term recovery profile of patients with severe disability or in vegetative states following severe primary intracerebral hemorrhage. J Crit Care. 2018;48:269-275. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2018.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roch A, Michelet P, Jullien AC, et al. Long-term outcome in intensive care unit survivors after mechanical ventilation for intracerebral hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(11):2651-2656. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000094222.57803.B4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sreekrishnan A, Leasure AC, Shi FD, et al. Functional improvement among intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) survivors up to 12 months post-injury. Neurocrit Care. 2017;27(3):326-333. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0425-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang WJ, Lu JJ, Wang YJ, et al. ; China National Stroke Registry (CNSR) . Clinical characteristics, management, and functional outcomes in Chinese patients within the first year after intracerebral hemorrhage: analysis from China National Stroke Registry. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(9):773-780. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00367.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sembill JA, Gerner ST, Volbers B, et al. Severity assessment in maximally treated ICH patients: the max-ICH score. Neurology. 2017;89(5):423-431. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000004174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji R, Shen H, Pan Y, et al. ; China National Stroke Registry (CNSR) investigators . A novel risk score to predict 1-year functional outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage and comparison with existing scores. Crit Care. 2013;17(6):R275. doi: 10.1186/cc13130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caprio FZ, Maas MB, Rosenberg NF, et al. Leukoaraiosis on magnetic resonance imaging correlates with worse outcomes after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44(3):642-646. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.676890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dowlatshahi D, Demchuk AM, Flaherty ML, Ali M, Lyden PL, Smith EE; VISTA Collaboration . Defining hematoma expansion in intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship with patient outcomes. Neurology. 2011;76(14):1238-1244. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182143317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Trifan G, Arshi B, Testai FD. Intraventricular hemorrhage severity as a predictor of outcome in intracerebral hemorrhage. Front Neurol. 2019;10:217. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.00217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morgan TC, Dawson J, Spengler D, et al. ; CLEAR and VISTA Investigators . The modified Graeb score: an enhanced tool for intraventricular hemorrhage measurement and prediction of functional outcome. Stroke. 2013;44(3):635-641. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.670653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graeb DA, Robertson WD, Lapointe JS, Nugent RA, Harrison PB. Computed tomographic diagnosis of intraventricular hemorrhage. etiology and prognosis. Radiology. 1982;143(1):91-96. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.6977795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hallevi H, Dar NS, Barreto AD, et al. The IVH score: a novel tool for estimating intraventricular hemorrhage volume: clinical and research implications. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):969-974. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318198683a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roh DJ, Asonye IS, Carvalho Poyraz F, et al. Intraventricular hemorrhage expansion in the CLEAR III trial: a post hoc exploratory analysis. Stroke. 2022;53(6):1847-1853. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.121.037438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bhattathiri PS, Gregson B, Prasad KS, Mendelow AD; STICH Investigators . Intraventricular hemorrhage and hydrocephalus after spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: results from the STICH trial. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2006;96:65-68. doi: 10.1007/3-211-30714-1_16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hanley DF, Lane K, McBee N, et al. Thrombolytic removal of intraventricular haemorrhage in treatment of severe stroke: results of the randomised, multicentre, multiregion, placebo-controlled CLEAR III trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10069):603-611. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32410-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hanley DF, Thompson RE, Rosenblum M, et al. . Efficacy and safety of minimally invasive surgery with thrombolysis in intracerebral haemorrhage evacuation (MISTIE III): a randomised, controlled, open-label, blinded endpoint phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2019;393(10175):1021-1032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30195-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ullman NL, Tahsili-Fahadan P, Thompson CB, Ziai WC, Hanley DF. Third ventricle obstruction by thalamic intracerebral hemorrhage predicts poor functional outcome among patients treated with alteplase in the CLEAR III trial. Neurocrit Care. 2019;30(2):380-386. doi: 10.1007/s12028-018-0610-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Evans WJ. An encephalographic ratio for estimating ventricular and cerebral atrophy. Arch NeurPsych. 1942;47(6):931-937. doi: 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1942.02290060069004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Swieten JC, Hijdra A, Koudstaal PJ, van Gijn J. Grading white matter lesions on CT and MRI: a simple scale. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53(12):1080-1083. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.53.12.1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fazekas F, Barkhof F, Wahlund LO, et al. CT and MRI rating of white matter lesions. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13(suppl 2):31-36. doi: 10.1159/000049147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy. 1996;37(1):53-72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sulter G, Steen C, De Keyser J. Use of the Barthel index and modified Rankin scale in acute stroke trials. Stroke. 1999;30(8):1538-1541. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.30.8.1538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weisscher N, Vermeulen M, Roos YB, de Haan RJ. What should be defined as good outcome in stroke trials; a modified Rankin score of 0-1 or 0-2? J Neurol. 2008;255(6):867-874. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0796-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rangaraju S, Haussen D, Nogueira RG, Nahab F, Frankel M. Comparison of 3-month stroke disability and quality of life across modified Rankin Scale categories. Interv Neurol. 2017;6(1-2):36-41. doi: 10.1159/000452634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slaughter KB, Meyer EG, Bambhroliya AB, et al. Direct assessment of health utilities using the standard gamble among patients with primary intracerebral hemorrhage. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2019;12(9):e005606. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.119.005606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asaithambi G, Tipps ME. Quality of life among ischemic stroke patients eligible for endovascular treatment: analysis of the Defuse 3 trial. J Neurointerv Surg. 2021;13(8):703-706. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wilson JTL, Hareendran A, Hendry A, Potter J, Bone I, Muir KW. Reliability of the modified Rankin Scale across multiple raters: benefits of a structured interview. Stroke. 2005;36(4):777-781. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000157596.13234.95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemphill JC III, Farrant M, Neill TA Jr. Prospective validation of the ICH score for 12-month functional outcome. Neurology. 2009;73(14):1088-1094. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b8b332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56(6):766-772. doi: 10.1212/WNL.56.6.766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karapanayiotides T, Piechowski-Jozwiak B, van Melle G, Bogousslavsky J, Devuyst G. Stroke patterns, etiology, and prognosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. Neurology. 2004;62(9):1558-1562. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000123252.55688.05 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jørgensen H, Nakayama H, Raaschou HO, Olsen TS. Stroke in patients with diabetes. the Copenhagen Stroke Study. Stroke. 1994;25(10):1977-1984. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.25.10.1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hansen BM, Nilsson OG, Anderson H, Norrving B, Säveland H, Lindgren A. Long term (13 years) prognosis after primary intracerebral haemorrhage: a prospective population based study of long term mortality, prognostic factors and causes of death. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2013;84(10):1150-1155. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-305200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasi M, Casolla B, Kyheng M, et al. Long-term functional decline of spontaneous intracerebral haemorrhage survivors. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2021;92(3):249-254. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2020-324741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pennlert J, Eriksson M, Carlberg B, Wiklund PG. Long-term risk and predictors of recurrent stroke beyond the acute phase. Stroke. 2014;45(6):1839-1841. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.005060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uniken Venema SM, Marini S, Lena UK, et al. Impact of cerebral small vessel disease on functional recovery after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;50(10):2722-2728. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.025061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ziai WC, Thompson CB, Mayo S, et al. ; Clot Lysis: Evaluating Accelerated Resolution of Intraventricular Hemorrhage (CLEAR III) Investigators . Intracranial hypertension and cerebral perfusion pressure insults in adult hypertensive intraventricular hemorrhage: occurrence and associations with outcome. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(8):1125-1134. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000003848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Al-Kawaz MN, Li Y, Thompson RE, et al. Intracranial pressure and cerebral perfusion pressure in large spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage and impact of minimally invasive surgery. Front Neurol. 2021;12:729831. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.729831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Havenon A, Majersik JJ, Stoddard G, et al. Increased blood pressure variability contributes to worse outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2018;49(8):1981-1984. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Boulanger M, Schneckenburger R, Join-Lambert C, et al. Diffusion-weighted imaging hyperintensities in subtypes of acute intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2019;50:135–142. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Menon RS, Burgess RE, Wing JJ, et al. Predictors of highly prevalent brain ischemia in intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(2):199-205. doi: 10.1002/ana.22668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prabhakaran S, Naidech AM. Ischemic brain injury after intracerebral hemorrhage: a critical review. Stroke. 2012;43(8):2258-2263. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.655910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hinduja A, Dibu J, Achi E, Patel A, Samant R, Yaghi S. Nosocomial infections in patients with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage. Am J Crit Care. 2015;24(3):227-231. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2015422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakajoh K, Nakagawa T, Sekizawa K, Matsui T, Arai H, Sasaki H. Relation between incidence of pneumonia and protective reflexes in post-stroke patients with oral or tube feeding. J Intern Med. 2000;247(1):39-42. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2000.00565.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Murthy SB, Moradiya Y, Shah J, et al. Nosocomial infections and outcomes after intracerebral hemorrhage: a population-based study. Neurocrit Care. 2016;25(2):178-184. doi: 10.1007/s12028-016-0282-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berger B, Gumbinger C, Steiner T, Sykora M. Epidemiologic features, risk factors, and outcome of sepsis in stroke patients treated on a neurologic intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2014;29(2):241-248. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maramattom BV, Weigand S, Reinalda M, Wijdicks EF, Manno EM. Pulmonary complications after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2006;5(2):115-119. doi: 10.1385/NCC:5:2:115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Otite FO, Khandelwal P, Malik AM, Chaturvedi S, Sacco RL, Romano JG. Ten-year temporal trends in medical complications after acute intracerebral hemorrhage in the united states. Stroke. 2017;48(3):596-603. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.015746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jiang R, Janssen MFB, Pickard AS. US population norms for the EQ-5D-5L and comparison of norms from face-to-face and online samples. Qual Life Res. 2021;30(3):803-816. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02650-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pantoni L, Simoni M, Pracucci G, Schmidt R, Barkhof F, Inzitari D. Visual rating scales for age-related white matter changes (leukoaraiosis): can the heterogeneity be reduced? Stroke. 2002;33(12):2827-2833. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000038424.70926.5E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ferguson KJ, Cvoro V, MacLullich AMJ, et al. Visual rating scales of white matter hyperintensities and atrophy: Comparison of computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(7):1815-1821. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.02.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Bivariate Analysis comparing good versus poor one-year outcome groups in the combined cohort of CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Patients

eTable 2. Differences between patients included in the analysis versus those excluded due to missing mRS at day-30 and/or day-365

eTable 3. Differences between patients that reported EQ-VAS versus those that did not report EQ-VAS

eTable 4. Differences between patients included and excluded from combined multivariable logistic regression model for primary outcome (mRS 0-3) due to missing data

eTable 5. Multivariable Logistic Regression Models for Factors Associated with Recovery to mRS 0-2 among Patients with mRS 3-5 at day-30

eTable 6. Multivariable Logistic Regression Model for Factors Associated with Recovery of at least 1-point in mRS among Patients with mRS 1-5 at day-30

eTable 7. Multivariable Logistic Regression Models Using Other mRS-Dichotomizations in ICH/IVH survivors with mRS 4-5 at day-30

eTable 8. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression Models Predicting One-Year All-Cause Mortality Among ICH/IVH survivors with Poor Day-30 Outcome

eFigure 1. Distribution of patients in each day-365 mRS category for all CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Survivors at day-30

eFigure 2. Home Discharge and Discharge Disposition Over One-Year

eFigure 3. Time to Home among CLEAR-III and MISTIE-III Patients with Poor Outcome at Day-30

eFigure 4. Modified Rankin Scale (mRS) trajectories among patients with mRS 4 versus mRS 5 at day-30

eFigure 5. Receiver Operator Curves (ROC) and Area-Under-the-Curve (AUC) for day-30 models versus baseline models

eTable 9. Sensitivity Analysis for missing mRS at day-30

eTable 10. Sensitivity Analysis for missing mRS at one-year mRS

eTable 11. Sensitivity Analysis for missing data-points in Combined Model for Good One-Year Outcome

eTable 12. Sensitivity Analysis for missing data-points in Cox Regression Model for One-Year Mortality

eFigure 6. Sensitivity Analysis for mRS Trajectories

eFigure 7. Sensitivity Analysis for EQ-VAS Trajectories