Abstract

The field of psychology is coming towards a critical juncture; scholars are increasingly recognizing that race, ethnicity, and culture play important roles in their fields of study, but do not always have the language to integrate race and culture into their own work. Furthermore, common conceptions of race may systematically exclude those from multiple racial and ethnic backgrounds in favor of fixed and discrete racial categories that ultimately perpetuate white supremacy. Meanwhile, as the Multiracial population of the US is growing at an unprecedented rate, psychologists need language to acknowledge this population in their studies and pursue research to advance the field’s knowledge of this diverse group and its many subpopulations. In an attempt to educate psychologists across subfields and disciplines, we provide a detailed account of preferred terms related to race and ethnicity with emphasis on ways to think about and talk about Multiracial populations in the United States. While preferred terms may change across time, the aim of this paper is to provide psychologists with the tools to begin nuanced and necessary discussions about how race informs their research and the populations they work with in uniform and non-stigmatizing ways. By highlighting terminology related to those of multiple racial and ethnic backgrounds, we demystify and legitimize these rapidly-growing but often hidden populations. Different perspectives on various terms are provided throughout to set psychologists on the path to beginning more race-conscious conversations and scientific inquiries into the experiences of Multiracial Americans and those from other marginalized racial-ethnic groups.

Keywords: Multiracial, Biracial, Multiethnic, Race, Identity

“As demographics change, language falls behind”

Race. The controversial topic that most try to avoid in daily conversation. This socially constructed grouping has shaped American society since Europeans first set foot on what is now the United States. If you walk into a college classroom and ask students to list the official racial categories on the U.S. Census, most would likely get it wrong. Yet, researchers often ask participants about their race on the first page of every survey, and reporting race or ethnicity is required by many journals (APA, 2020). Consequently, regardless of whether race is the focus of one’s research, it is a concept that all researchers in psychology must deeply consider.

Race is an elusive concept because, as a social construction, its meaning varies across time and context (Suyemoto et al., 2020). In this paper, we focus on the understanding of race in the U.S. context, drawing heavily from sociological literature that has provided important insights into the social construction of race in the US (e.g., Bonilla Silva, 2005). According to Critical Race Theory (Delgado & Stefancic, 2012), race is not an objective, biological trait, but rather races are invented by societies and manipulated when convenient to uphold a racial hierarchy that benefits a dominant group. Thus, over the course of U.S. history, racial categories and how people are assigned to those categories has changed relative to sociopolitical contexts. This is evident in how the U.S. Census categories have changed over time (Morning, 2000). Psychologists have played a role in perpetuating the biological basis of race and the inferiority of racial groups of color through the 20th century (Smedley & Smedley, 2005), and scientific racism has made a more recent comeback with genomics research (Roberts, 2011). At this juncture, it is especially important that psychologists rededicate themselves towards promoting racial equity and equality in their research, teaching, and mentorship . One major way psychologists can begin to work towards these goals is by reexamining the terms and language they use to refer to racial groups, as our understanding and conceptualization of race impacts not only our research, but also how we teach and train the next generation of psychologists.

To understand the ever changing nature of race and racial categories, researchers need to be explicit about language. In particular, psychologists need a common understanding of the terminology used in research about race to guide valid and robust research (Suyemoto et al., 2020). In recent decades, one of the significant population shifts has been among the Multiracial population in the U.S. The Multiracial population is currently the fastest growing racial group in the United States (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018). However, Multiracial Americans were only officially recognized and counted by the U.S. Census starting in 2000, just a little over two decades ago. The limited data that is available about the nation’s Multiracial population analyzed by the Pew Research Center reveals that one in seven babies born in 2015 were Multiracial or multiethnic (Livingston, 2017), and projections estimate that by 2060, Multiracial youth under the age of 18 will make up 11.3% of the U.S. population (U.S. Census Bureau, 2018).

But who comprises this population? Who is considered Multiracial when socially constructed definitions of race are constantly changing over time? Where should the line be drawn of who to identify as Multiracial given that all humans are technically Multiracial because they have migrated across the globe and mixed with one another all throughout history (Spickard, 2016)? With the recent popularity of DNA test kits, more and more individuals are discovering that they have genealogically distant mixed ancestry, which could lead more people to identify with multiple racial backgrounds or call themselves Multiracial despite this identity not being salient to them before. Given these new developments, how do we, as researchers, define the rapidly growing Multiracial population?

To keep up with the changing demographics, the purpose of this paper is to provide a starting point for psychologists to understand race terminology that is inclusive of the growing Multiracial population1. Recommendations for how race should be measured in research are beyond the scope of the present paper (see Helms et al., 2005 and Saperstein et al., 2016). However, we do not support the use of racial categories as proxies for the examination of processes underlying racial differences that are often due to systemic racism and oppression (Helms et al., 2005). We share our perspectives as a team of scholars with lived experiences of being Multiracial and being part of multiracial families, applying what we have learned from studying Multiracials to offer guidance for defining and understanding race and multiraciality in the current socio-political moment. Importantly, we utilize Critical Multiracial Theory (MultiCrit; Harris, 2016) as a framework for understanding race and racism. Multicrit highlights the need to challenge ahistorical analyses of racial issues and dominant ideologies of race. One manifestation of racism is the monoracial paradigm of race in the United States, which emphasizes that racial categories are mutually exclusive (Harris, 2016). The construction of race as existing in neatly defined monoracial categories has long functioned to maintain the idea of racial purity, effectively upholding white2 supremacy and erasing Multiracial realities (Harris, 2016). As the Multiracial population in the US grows, there is an urgent need for researchers to define racism and race as it relates to the experiences of both monoracial and Multiracial people.

There are varying ways that terms and populations can be defined, and we attempt to note the different perspectives on using certain terminology. The definitions we present are specific to the U.S. context, given that race is constructed differently around the world. We also acknowledge that the terms listed here will one day be problematic, outdated, and/or change in meaning as language is ever-evolving. Furthermore, we do not expect every scholar to agree with and use our definitions of these terms in the Multiracial literature. Given that the nature of academia is to challenge one another to advance science, we hope that everyone participates in a collective effort to use terminology that challenges the white supremacy and racism that has long dominated the field of psychology and U.S. society. Lastly, please note that our definitions may not reflect colloquial understandings (see Suyemoto et al., 2020 study of colloquial understandings of race and ethnicity). In sum, our strongest recommendation is that scholars always define the terms they are using in their studies. We even suggest that terms as basic as “race” and “ethnicity” be contested and re-defined, because as scholars focused on these topics often note, these constructs are not always clear cut (Schwartz et al., 2014). For a summary of the terms and definitions provided in this paper, please see Table 1.

Table 1.

Terms and definitions

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Monoracial paradigm of race | An understanding of race that emphasizes mutually exclusive racial categories (Harris, 2016) |

| Racism | “Organized systems within societies that cause avoidable and unfair inequalities in power, resources, capacities, and opportunities across groups” (Paradies et al., 2015, p.2) |

| Race | A socially constructed political system and product of racism that categorizes people into different groups based on perceived physical differences and/or recent ancestry in order to create and maintain a power hierarchy that privileges whiteness |

| Ethnicity | A social group with shared culture, language, and/or place of origin |

| Culture | The shared physical and social customs of a group of people, which can include art and social norms, beliefs, and values (Betancourt & López, 1993) |

| Racialization | The creation and transformation of racial groups according to meanings assigned for political reasons (Omi & Winant, 2015) |

| Multicultural | Representing multiple cultures |

| Multiethnic; mixed heritage | Refers to anyone with biological parents of two or more different ethnic backgrounds |

| Monoracial | Refers to an individual or group with only one racial background |

| Multiracial; mixed race | Refers to anyone with biological parents of two or more different racial backgrounds |

| Multigenerational Multiracial | Refers to anyone with at least one biological parent who is Multiracial |

| Second-generation Multiracial | Multiracial individuals with one or two Multiracial biological parents and monoracial grandparents |

| Biracial | Refers to anyone with two different racial backgrounds, including but not limited to individuals with two biological parents from different monoracial groups |

| Racial majority group | Refers to Whites as the racial group with the most power in the context of the US |

| Racial minority group | Refers to Black, Asian, Latinx, American Indian, Pacific Islander, and Middle Eastern/North African racial groups as the oppressed in the context of the US |

| Majority-minority Biracial | Biracial individuals with one White biological parent and one biological parent from a minoritized monoracial group |

| Majority-minority Multiracial | Multiracial individuals with White ancestry |

| Minority-minority Biracial; dual-minority Biracial | Multiracial individuals with two biological parents from minoritized monoracial groups |

| Multiple-minority Multiracial | Individuals with biological parents from two or more minoritized monoracial groups |

| Genealogically-immediate mixed race ancestry | Individuals who are Biracial or who have one or two biological parents that are Biracial |

| Genealogically-distant mixed race ancestry | Individuals with ancestors who had Multiracial children more than two generations previously |

Defining Race, Ethnicity, and Culture

The prerequisite to defining Multiracial is to define racism and race. We contend that race should always be defined based on its connection to racism. Paradies and colleagues (2015) defined racism as “organized systems within societies that cause avoidable and unfair inequalities in power, resources, capacities, and opportunities across racial groups” (p. 2). As a form of social organization, racism produces race and organizes racial groups according to a hierarchical racial structure (Bonilla-Silva, 2015). The function of racism is to preserve the social, economic, political, and ideological dominance of one racial group. Consequently, race and racial categories are differentially constructed across time and contexts to serve specific material needs. For example, racial categories were used to justify the exploitation of Black slave labor in the United States (Wright, 1900).

Historically, the racial structure in the United States has enforced discrete, monoracial boundaries based on phenotype (e.g., skin color, hair texture, eye shape) in order to uphold white supremacy. Accordingly, racial identity scholars have defined race as “a characterization of a group of people believed to share physical characteristics such as skin color, facial features, and other hereditary traits” (Cokley, 2007, pp. 225). Moreover, the newest edition of the American Psychological Association (APA) Publication Manual similarly defines race as “physical differences that groups and cultures consider socially significant” (APA, 2020, p. 142). However, racial ideology does not require distinctive physical traits for people to racialize others (Smedley & Smedley, 2005). Richeson and Sommers’ (2016) illustrate other factors that affect racial categorization in their model of race, noting, “the emerging research on the perception of multiracial individuals underscores that racial categorization is far more than a simple matter of physical appearance or biology, but rather a dynamic process informed by a number of sociocultural, motivation, and cognitive factors” (p. 443). For example, Khanna (2010) found that Black-White Biracial participants who did not have visible characteristics indicating Black ancestry reported being treated as Black after revealing their ancestry. Furthermore, acknowledging the power basis of race is important in defining it. Thus, we suggest that race be defined as a socially constructed political system and product of racism that categorizes people into different groups based on perceived physical differences and/or recent ancestry in order to create and maintain a power hierarchy that privileges whiteness (Roberts, 2011; Smedley & Smedley, 2005; Suyemoto et al., 2020).

In the United States, physical differences have historically been used to distinguish between monoracial categories. However, as Franco (2019, pp. 55) points out, “Multiracial people violate traditional norms of race” because their phenotypes do not always fit neatly into monoracial categories. In Chen and Hamilton’s (2012) experimental study, Americans had more difficulty and took longer classifying images of Multiracial people than monoracial people. It takes more cognitive capacity to categorize Multiracials because they do not fit into the prevailing schema of race in the United States defined by separate, monoracial groups. Thus, we include recent racial ancestry in the definition of race to acknowledge that Multiracial individuals are still considered members of racial groups even if they are not physically read as such by others. It is also important to note that the system of assigning race solely based on phenotype may be the norm in the contexts of other countries, such as Brazil, where people are racially identified based on the color of their skin rather than their ancestry (Golash-Boza, 2018).

Next, we define ethnicity as a social group with shared culture, language, and/or place of origin (Golash-Boza, 2018; Smedley & Smedley, 2006) and culture as the shared physical and social customs of a group of people, which can include social norms, beliefs, and values (Betancourt & López, 1993). One key difference between race and ethnicity is that race is based in power and privilege such that racial groups are predominantly defined by the dominant group’s views, while ethnic groups typically define what values and practices are associated with their ethnicity (Markus, 2005). Thus, in studying racial groups, researchers need to acknowledge and understand how racism and the system of power differences based on race affect the lived experiences of the study populations and context. In studying ethnic groups, researchers may be primarily interested in understanding cultural experiences or differences, but it may still be necessary to acknowledge how race and racism intersect with ethnic lived experiences.

We acknowledge that race and ethnicity are often conflated in both public and academic settings. Life experiences can be both racial and ethnic at the same time and distinguishing between them is not always possible or appropriate. Black culture, for example, is both a racial phenomenon and a cultural set of beliefs and practices. Psychologists have recognized these blurred boundaries when operationally defining constructs and processes such as ethnic-racial socialization (Hughes et al., 2006) and ethnic-racial identity development (Umana-Taylor et al., 2014). We agree that this hyphenation can be a useful heuristic depending on the question or issue being addressed or studied. However, if the goal or focus is to identify and target specific groups and populations (e.g. Multiracial, multiethnic, monoracial Black, monoethnic Chinese), then researchers need to be mindful of the distinctive nature of the constructs and separately interrogate and study these experiences.

Racial Groups

Which groups are considered races in the US? This is a complicated issue given that race is socially constructed and the recognition of various groups as races has always been in flux over the course of history based on sociopolitical circumstances and the process of racialization, in which racial groups are created and transformed according to the meanings assigned to them for political reasons (Omi & Winant, 2015; Pierce, 2000). In the 2000 and 2020 U.S. Censuses, the following five groups were considered racial groups: White, Black or African American, Asian, American Indian or Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander (Pew Research Center, 2020). In addition, they included a box for “some other race” (which has been an option since 1910, though originally worded as “other”; Ashok, 2016). Starting in 2000, respondents could select multiple boxes on the Census to indicate Multiracial heritage.

However, Latinx is not officially included as a racial group in the Census. Note that we utilize the term Latinx (pronounced La-teen-ex), as the Journal of Latinx Psychology recommends this term, which is more inclusive of diverse gender identities (Cardemil et al., 2019). Another gender-neutral alternative that some people prefer is Latiné. The Census first attempted to describe this population with the racial category of “Mexican” in the 1930 Census, but this was removed as there was concern Mexicans were not a racial group (Allen et al., 2011). In the 1970 census, the term Hispanic was first introduced by the Census to describe those who have origins in Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Central or South America or other “Spanish” cultures, highlighting language as a unifying feature of this ethnic classification. However, given that Brazil is not a Spanish speaking country, the term Latino was introduced in the 2000 Census and specifically focused on those with Latin American origins as opposed to focusing on Spanish-speaking origins (e.g., Spain). Both terms are still used by the population as self-descriptors. But it is important to note that these terms uniquely exist in the U.S as a ‘pan-ethnic’ label that are meaningless in other countries and that within the population, Latinxs eschew the notion of a shared cultural and ethnic identity, preferring to remain connected to their country of origin (Taylor et al., 2012). Thus, the grouping of Latinx population as a meaningful ethnic and cultural group is somewhat problematic, and suggests that this population aligns more with our definition of a racial group.

In the 2000 Census, “some other race” became the third largest racial group in the U.S. due to the large portion of Latinx folks who did not endorse any of the five racial groups (Humes et al., 2011). Indeed, across four decennial Censuses (1980–2020), about 40% of Latinx/Hispanic people endorsed “some other race” versus less than 2% of non-Latinx/Hispanics (Rodriguez et al., 2013). At first, this selection was attributed to the fact that Latinx folks may identify inherently as “mestizos” or Multiracial, which was not an option in the earlier censuses. But when given the option of checking multiple racial categories in the 2000 Census, “some other race” was still significantly endorsed (47%), and multiple racial groups were only endorsed by 6% of the Latinx population. This suggests that a majority of Latinx folks do not perceive themselves inherently as Multiracial but instead see themselves as a distinct racial group (i.e., some other race) or as fitting within the current racial hierarchy in the U.S. (e.g., in the 2010 Census, primarily White (53%) and Black (2.5%); Humes et al., 2011).

Given that our focus is on race as a categorization that enables white supremacy, sociological work highlights the racialization of Latinx groups into the racial hierarchy, particularly for darker-skinned and immigrant Latinxs (Bonilla-Silva, 2004), whereby Latinx identified individuals experience significant discrimination and racism in the U.S. Taken together with the fact that “some other race” was the third largest racial category in the 2010 Census (Humes et al., 2011), to study the Multiracial population in the U.S. requires a consideration of the racialization in the U.S. of Latinx-origin populations. Yet, by having Latinx as a larger racial category, this may obscure differences between Latinx who identify as White, Black, or “some other race,” and there is evidence to suggest that Black or “some other race” Latinx tend to experience more marginalization (e.g., lower levels of education, greater discrimination, more likely to be foreign born; Stokes-Brown, 2012). Thus, Latinx individuals who identify as White or are phenotypically White do not experience the same level of marginalization and benefit from white privilege (Chavez-Duenas et al., 2014).

The lack of clarity of Latinx as a racial vs. ethnic group complicates then how to consider this group in terms of Multiraciality. If considered an ethnicity, as Morning (2000) noted when the option to check multiple boxes on the Census first became available, “An American of German and Mexican ancestry is likely to consider himself or herself mixed-race since Hispanics are often considered a social race distinct from Whites. Yet such Multiracial identification will not emerge in a Census that does not recognize Hispanics as constituting a separate racial group” (p. 212). Further, Black-Latinx Multiracials (e.g., African American and Mexican American parentage) that are not Afro-Latinx (e.g., both parents from a Latin American country) would also not be classified as Multiracial even though their heritage and identity may be distinct from an Afro-Latinx identity. The 2020 U.S. Census continued to treat Hispanic, Latinx, and Spanish origin as an ethnic group, preceding the race question in the Census with the “Hispanic Origin” question, which will have continued implications for how individuals with Latinx ancestry are able to self-identify. A study by Miyawaki (2016) found that 74% of Multiracial Latinx participants wanted Hispanic origins to be included in the race question, and 70% identified as “mixed” or as “both” Latinx and another race. Thus, racial classification for Latinxs is complex, nuanced and beyond the scope of this paper (see Allen et al., 2011 for further discussion). However, in research with Multiracial populations, the unique experiences of Latinxs in the United States as a racialized group suggest that people with Latinx ancestry may consider themselves Multiracial and hence their experiences and identity need to be further explored.

We also consider Middle Eastern or North African (MENA) to be its own racial group in the United States due to their unique racialized experiences, including increased discrimination since 9/11. Chaney and colleagues (2020) found that participants rarely categorized MENA Americans as White despite their legal classification as White. As Awad and colleagues (2019) highlight, the historical classification of MENA as White has resulted in their unique racial experiences being understudied, when this group faces discrimination and suffers health disparities. Furthermore, the U.S. Census considered adding Latinx and MENA as racial groups for the 2020 Census (Wang, 2018), so the consideration of these groups as races seems to be the direction that U.S. society is currently headed. While each group has its own unique history of terminology and categorization, we focus here on Latinx and MENA because they are not officially recognized on the Census. In summary, we consider the following seven groups to be racial groups: American Indian or Alaska Native, Pacific Islander, African American or Black, Latinx, Asian, MENA, and White. Note that if it is necessary to label study participants with a term they may not personally identify with (e.g., grouping people who identify as Mexican American, Puerto Rican, etc. and referring to them as Latinx), we recommend acknowledging this issue when presenting the data.

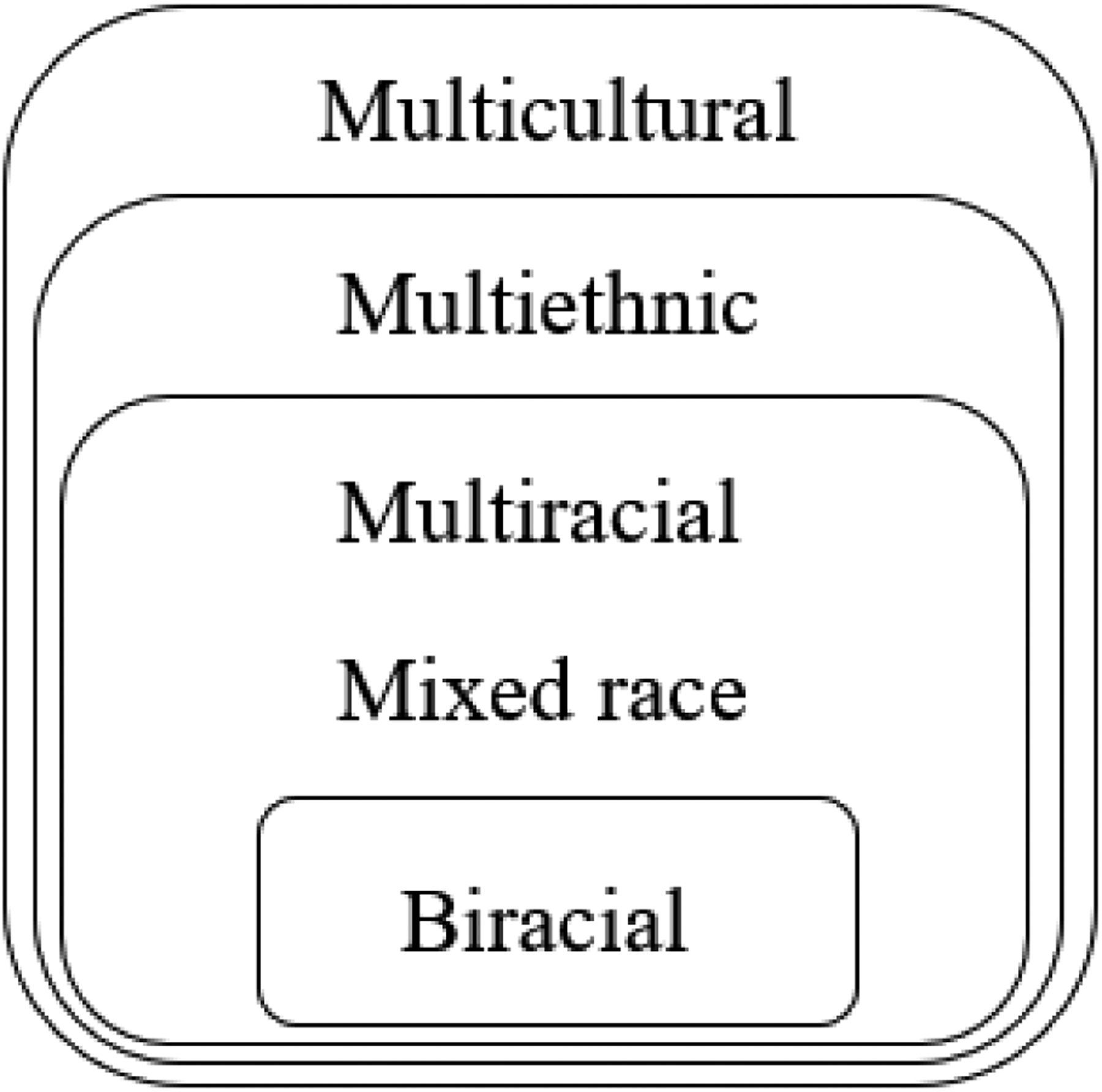

Defining Multiracial, Biracial, Multiethnic, and Multicultural

It is important to distinguish the terms Multiracial, Biracial, multiethnic, and multicultural, given that they are sometimes used interchangeably when it may be more appropriate to use a specific term (see Figure 1 to see how these terms are related). Individuals may identify with these terms in ways that are not in line with our research definitions. Furthermore, depending on how the researcher defines race and ethnicity in their study, and the groups associated with each, who is considered Multiracial and multiethnic may vary. Again, we acknowledge that the terms that are accepted vary across time and contexts. We describe our understanding of what terms are commonly used in the literature with Multiracial Americans in recent years, but different countries may use other terms. For example, “mixed parentage” seems to be used more often by scholars in the United Kingdom than in the United States (e.g., Britton, 2013). Thus, it is crucial that researchers clearly define the terms race and ethnicity, the groups they consider races, and the respective population of interest in each study.

Figure 1.

A visualization of the relationship between terms.

Multicultural

Multicultural is a very broad term that refers to anything involving multiple cultures. For example, multicultural psychology is the study of the ways culture influences how people think, feel, and act (Mio et al., 2019), whereas multicultural education refers to education that incorporates different cultural histories and perspectives. While multicultural could be used to describe a population, individuals can be multicultural for a number of reasons other than their parents having different racial or ethnic group memberships (e.g., growing up in different countries, being raised by stepparents from other cultures). Thus, the term is somewhat vague for defining a population. Related, but also distinct, bicultural is a term growing in popularity in the field of psychology which refers to individuals with two cultures (Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, 2013). However, this term is typically used to refer to the acculturation process for American immigrants, in that the two cultures involved are the dominant, mainstream culture (e.g., U.S. American culture) and one’s ethnic heritage culture. Thus, the term bicultural and most of the existing measures that assess biculturalism are designed for research with monoracial minority populations (e.g., Asians and Latinx; Nguyen & Benet-Martinez, 2013). A notable exception is the Multiracial Identity Integration (MII) measure created by Cheng and Lee (2009), which is an adaptation of Benet-Martinez and Haritatos’ (2005) Bicultural Identity Integration measure. The MII aims to measure the relative distance and conflict between an individual’s multiple monoracial groups in forming a cohesive and integrated racial identity. While the biculturalism literature may add a unique perspective to the study of Multiracials, additional care to intersectionality and possible existence of a distinct Multiracial identity may be warranted. Albuja, Sanchez, and Gaither (2019) provide a good example of a careful and principled comparison of bicultural and Biracial individuals, as they provide strong theoretical rationale for the potential similarities and differences between these groups.

Multiethnic

Multiethnic and mixed heritage are terms that refer to anyone with biological parents of two or more different ethnic backgrounds. All Multiracial individuals are multiethnic, but not all multiethnic individuals are Multiracial. For example, someone who is Chinese and Japanese would be multiethnic but monoracial Asian, and someone who is Irish and Swedish would be multiethnic but monoracial White. Thus, the term multiethnic encompasses a much broader group than Multiracial. We recommend that researchers be as specific as possible when labeling a group. While there are shared experiences between Multiracial and monoracial multiethnic individuals, there are also differences based on the unique racialized experiences of Multiracials whose existence challenges the monoracial paradigm of U.S. society. Thus, there may be times when grouping Multiracials and monoracial multiethnic individuals together is less informative.

Multiracial and mixed race

Currently, mixed race and Multiracial are generally viewed as acceptable, synonymous terms referring to individuals with biological parents of two or more different racial backgrounds (including parent(s) that are themselves Multiracial). The term “Multiracial” is said to have first been introduced in 1979 in a dissertation by Christine Iijima Hall exploring the experiences of Black and Japanese individuals (Donnella, 2016). However, the term “mixed” has been around for at least 200 years, and has been more controversial. In particular, critics of the term “mixed” or “mixed race” feel that it reinforces stereotypes of being mixed up or confused, or is tied to animal breeding such as mixed dogs or horses, which are regarded as inferior to pure-breeds (Donnella, 2016). Multiracial scholar, Teresa Williams-Leon, believes the term mixed “evokes identity crisis”, becoming “the antithesis to pure” (Donnella, 2016). On the other hand, some prefer the terms mixed or mixed race because Multiracial is sometimes confused with referring to a diverse group of people with multiple monoracial members (e.g., a multiracial society), rather than to an individual with multiple racial heritages.

Notably, while the field of psychology does not have any organizations dedicated to Multiracial scholars or research, the largest academic organization serving Multiracial individuals is “Critical Mixed Race Studies,” and its affiliated journal is the Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies. The journal editor, Reginald Daniel, discusses the debate over whether to use the term Multiracial or mixed race in the title in the editor’s note of the first issue (see Daniel, 2011 for the discussion). To summarize, there was concern that naming the journal the Journal of Multiracial Studies would lead to confusion as to whether Multiracial was referring to diversity and multiculturalism broadly, so they chose to go with mixed race, noting that both terms are used interchangeably in the journal as terms that are widely used in Multiracial research and the public imagination (Daniel, 2011).

It is also important to note that applying the term Multiracial to describe families does not necessarily equate to a family with Multiracial individuals in it. A multiracial family could also describe a family with a transracial adoptee, in which the parents and adopted children are of different racial backgrounds. Alternatively, an interracial couple with no children or a blended family in which a parent with monoracial children remarried someone of a different racial background could also be considered multiracial families due to having individuals of different racial backgrounds in the family. There are a number of other terms that refer to Multiracial people as well - please see the “specific terms” section below for a discussion of more colloquial terminology. We decided to consistently describe unique Multiracial groups by hyphenating their racial group memberships. For example, we refer to people with Black and Asian heritage as “Black-Asian” or “Asian-Black.” Researchers may also choose to be intentional by listing lower status racial groups first in an effort to challenge the privileges afforded to more powerful groups in the U.S. racial hierarchy (e.g., Whites).

Multigenerational Multiracial

Multigenerational Multiracial is a broad term that refers to anyone with at least one biological parent who is Multiracial, while second-generation Multiracial specifically refers to Multiracials with one or two Multiracial biological parents and monoracial grandparents. But where do we draw the line for who we consider Multiracial? Song (2017) asks this question,

Given the growing commonality of second (and even third) generation Multiracial people (i.e., people who know of their mixed ancestries going several generations back), is there a tipping point at which one’s Multiracial status (or a distant minority ancestry) is no longer meaningful to people, and how may the salience (or not) of one’s Multiracial ancestry differ for disparate types of mixed people?

(p. 2335)

Currently, there is no widely accepted convention for who is considered Multiracial in the social sciences (Song, 2017). As Morning (2000) noted when the 2000 Census first allowed people to check multiple boxes,

Despite the fact that racial intermixing has taken place for centuries in the United States, today the biracial, genealogically-immediate experience seems to be our normative Multiracial status, and Americans whose mixed race ancestry is more distant do not fit our image of the Multiracial population.

(p. 214)

However, given the increased visibility and growing numbers of Multiracials since 2000, it is more common for second-generation Multiracials to be recognized and identify as Multiracial. Who can be considered Multiracial and who identifies as Multiracial varies according to a number of factors (e.g., age, gender, education, class, region of residence in the U.S., political attitudes, racial ancestry; Morning, 2000) and will continually change over time. As researchers, where people draw the line is an empirical question to be explored. For now, in studies, researchers should be clear about who is included in their definition of Multiracial.

Biracial

The terms Multiracial and mixed race serve as an umbrella to Biracial, which more specifically refers to individuals with two different racial backgrounds. Biracial is typically thought to describe individuals with two biological parents of different monoracial backgrounds. However, it is possible that individuals with two racial backgrounds and one or two Multiracial parents would consider themselves Biracial as well. For example, an individual’s mother may be Biracial Asian and White and their father may be monoracial Asian, so they consider themselves Biracial because they technically have two racial backgrounds. Alternatively, one might have two parents with the same racial mix (e.g., both parents are Mexican and Filipino), and thus consider themselves Biracial. However, others with these same backgrounds may subscribe to the former definition and consider themselves Multiracial instead of Biracial. Researchers aiming to study a Biracial sample should consider which of these definitions is appropriate for their research question and define the population accordingly for potential participants. Furthermore, researchers should note that when a participant indicates they have two racial backgrounds on a survey, they may not necessarily have two monoracial parents as shown in the examples above.

Throughout this paper, we utilize the definition of Biracial individuals as those with monoracial biological parents of two different racial backgrounds. Based on this definition, there are 21 different Biracial combinations of the seven racial groups. However, as Song (2017) notes, this categorization implies that the biological parents are “pure” monoracial when there is a possibility that one or more of their ancestors were racially mixed.

The usage of majority, minority, and non-White

Many are moving away from using the terms “majority” and “minority” to refer to racial groups (Morris, 2019). One argument against using these terms is that the U.S. population is moving towards being a ‘majority minority’ country, in that there will soon be no majority group because Whites will no longer be the numerical majority by 2042. Thus, the terms will no longer be mathematically accurate. Another argument is that the term “minority” connotes being of lesser importance, normalizing the idea that people of color have a permanent status of subordination relative to the dominant White majority (Armstrong, 2019). Furthermore, critics say that the term is a euphemism for avoiding “straight talk about race relations” (Woods, 2002), and that it is insulting to Blacks, Latinx, Asians, American Indians, and Pacific Islanders because it ignores their unique experiences by grouping them all together. The APA Publication Manual (2020) highlights these arguments, advising the following:

To refer to non-White racial and ethnic groups collectively, use terms such as “people of color” or “underrepresented groups” rather than “minorities.” The use of “minority” may be viewed pejoratively because it is usually equated with being less than, oppressed, or deficient in comparison with the majority (i.e., White people). Rather, a minority group is a population subgroup with ethnic, racial, social, religious, or other characteristics different from those of the majority of the population, though the relevance of this term is changing as the demographics of the population change… If a distinction is needed between the dominant racial group and nondominant racial groups, use a modifier (e.g., “ethnic,” “racial”) when using the word “minority” (e.g., ethnic minority, racial minority, racial-ethnic minority). When possible, use the specific name of the group or groups to which you are referring.

(p. 145)

In addition to these guidelines, alternative terms that have been recommended include majoritized and minoritized to “recognize the socially and politically constructed nature of people’s statuses in the US” (Armstrong, 2019). People of color can also collectively be referred to using the acronym BIPOC, which stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color to recognize Black and Indigenous voices that are often erased (Garcia, 2020).

Notably, others interpret the terms majority and minority as a way to acknowledge the marginalized status of oppressed racial groups relative to the power held by the majority group, regardless of the population count. This is the perspective from which previous Multiracial scholars have used the terms majority-minority and minority-minority, multiple-minority, or dual-minority to refer to Multiracial individuals (e.g., Atkin & Jackson, 2021; Rondilla et al., 2017). Specifically, majority-minority Biracial has been used to label anyone with one White biological parent (i.e., majority) and one biological parent from a minoritized monoracial group (i.e., minority) (Atkin & Jackson, 2021). Majority-minority in reference to Multiracials generally can be used to describe those with White ancestry (e.g., an individual with a Black parent and a Biracial White and American Indian parent). Minority-minority, multiple-minority, and dual-minority Biracial have been used to label individuals with two biological parents from minoritized monoracial groups (Atkin & Jackson, 2021; Rondilla et al., 2017). Multiple-minority Multiracial may be most straightforward for referring to Multiracial individuals with biological parents from two or more minoritized monoracial groups.

However, using the terms above without “Biracial” could be confusing because technically all Multiracial people are also racial-ethnic minorities. For instance, someone with a Multiracial parent with White heritage, such as an Asian and White mother, and Latino father, could be considered minority-minority or dual-minority as both their Multiracial parent and monoracial minority parent are racial minorities. However, as noted previously, due to having White heritage, such an individual could instead be categorized as majority-minority. Depending on the goals of the broader categorization, researchers should define and label these groups in line with the study goals. For example, we present these terms to recognize that within the incredibly diverse Multiracial population, there are some notable differences between the experiences of majority-minority Multiracials due to their White heritage compared to those of multiple-minority Multiracials who do not have White heritage (Rondilla et al., 2017). The latter are largely invisible in U.S. society and research on the Multiracial population. Thus, referring to these populations allows researchers to highlight these disparities, while also describing how samples represent and generalize to subgroups of the Multiracial population. Given that there are 21 possible Biracial combinations based on the seven racial groups we recognize, six of which are majority-minority groups and 15 of which are multiple-minority groups, having these terms could be useful to summarize who is being represented in studies, though we recommend being more specific in listing unique racial combinations when possible. Though White Biracial, White Multiracial, non-White Biracial, and non-White Multiracial could be alternatives as well, these terms are problematic in how they center whiteness. In sum, we recommend that researchers be thoughtful about how they define and utilize terms and the implications of the language they use for the populations they are referring to.

Specific Terms Referring to Multiracial Individuals

There are a number of colloquial terms and nicknames that refer to Multiracials generally or to specific racial combinations. The meaning and acceptability of these terms also changes frequently across time and context. For instance, we consider the following terms to be dehumanizing and offensive: “mutt,” “mongrel,” “hybrid,” “half breed,” “half caste,” even though Barack Obama, who is Biracial, referred to himself as a “mutt” (Squires et al., 2010). In addition, “mulatto” is an outdated term referring to mixed race children of Black and White interracial unions, which was derived from the word “mule,” a sterile mixed-breed animal (Jackson & Samuels, 2019). However, some such as Loving Day book author Mat Johnson (2015) say they have reclaimed the term as their preferred identifier (Donnella, 2016). While a Multiracial person has the right to identify with whatever term they choose, researchers need to be cautious about the terms they use and placing labels on individuals. Thus, we recommend that researchers only use derogatory terms when necessary to portray a participant’s own words, and to follow this with clarification about why the terms are viewed as problematic.

There are other terms used for specific Multiracial backgrounds that are common but controversial. For example, “mestizo” was a term pushed by elites in Latin America to form a unified national identity that emphasized racial mixing and integration, but it still privileged whiteness and de-emphasized the unique contributions of marginalized communities (e.g, Indigenous, African origin; Telles & Garcia, 2013). Furthermore, “hapa” has long been popular among the Asian Multiracial community, but there is a growing awareness that the term is problematic for non-Hawaiians to use given that the word originates from the Hawaiian native language and is thus appropriative and “complicit in settler colonial erasure of Indigenous peoples” (Chang, 2018, p. 9). “Amerasian” is also a term referring to Asian Multiracial children specifically born from interracial relationships between American GIs and Asian women during World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War; and therefore, this term is not often used by younger generations. Multiracial Japanese often use the term “hafu,” or half, from the Japanese language, but some find it derogatory given it implies one is not fully Japanese. Similarly, we do not endorse using “part,” “half,” or any other fraction to describe Multiracials because this implies that they are not full members of their racial groups and reinforces essentialist ideas of race (Atkin & Yoo, 2019; Rondilla et al., 2017). We refer readers to Schmidt’s (2011) critical review on Native American identity and the history of blood quantum for a deeper understanding of the potential social, economic, and political problems associated with needing a certain percentage of native blood and family lineage to claim tribal group membership. This is in no way an exhaustive list of terms, as new terms are being created by Multiracial individuals to label themselves every day (e.g., Blasian, Mexipino, Latinegra, Blaxican, Indipino; Guevarra, 2012; Rondilla et al., 2017). However, we hope this highlights that researchers need to be thoughtful about the terms they employ and consider the history and implications that complicate their usage. We recommend learning about the history and experiences of Multiracial populations by reading across disciplines (e.g., Carter, 2013; Cashin, 2017).

Identity vs. Ancestry

Having mixed race ancestral origins and identifying as Biracial or Multiracial are two related, but separate issues. While all people who identify as Multiracial have genealogically mixed race ancestry, not all people with mixed race ancestry identify as Multiracial (Morning, 2000). Pew Research Center (2015) reported that more than 60% of individuals reporting a mixed racial ancestry did not self-identify as Multiracial. Multiracial individuals with genealogically-immediate mixed race ancestry would be those who are Biracial or who have one or two biological parents that are Biracial; it is more likely that these individuals would identify as Biracial or Multiracial. Individuals with genealogically-distant mixed race ancestry would include those with ancestors who had Multiracial children more than two generations previously. Distinguishing between mixed race identity and mixed race ancestry and using and defining the above terms may be helpful for researchers. However, even Biracials may choose to identify as monoracial, so describing participants using terms other than what they identify with should be avoided unless necessary to distinguish racial experiences related to power and oppression. For example, the one-drop rule, or hypodescent, which was created to keep the mixed race offspring of Black people enslaved, is often still applied to assign Multiracial individuals to their lowest status minoritized racial group (Bratter & O’Connell, 2017). Thus, some Black Multiracial youth choose to identify as Black because they are treated as Black and want to show pride in this group devalued by society.

Furthermore, racial categorization alone is not enough to understand the racial experience of Multiracial individuals, as there is a lot of phenotypic variation among individuals with the same racial ancestry that affects their experiences in society. For instance, there is a long history of the phenomenon of “White passing” (see Hobbs, 2014), when Multiracial Black people chose to pass as White to escape slavery prior to emancipation or in order to get jobs to survive during Jim Crow segregation. Today, the term White passing is often used outside of its historical context to refer to Multiracial people perceived as White. Thus, we recommend that scholars clearly define what they mean if using the term White passing, clarifying whether they are referring to an intentional act of choosing to pretend to be monoracial White. Alternatively, White presenting, White assumed, or read as White may be more appropriate for describing Multiracial individuals who are mistakenly perceived as White due to their phenotype.

Lastly, we want to acknowledge that being Multiracial and Black, Latinx, American Indian, Pacific Islander, Asian, and/or White are not mutually exclusive. For example, the first author identifies as a Biracial Asian American. While this is highly controversial in U.S. society, we hold that one can be both Biracial and Black, though everyone is entitled to identify however they choose. Regardless of how one identifies, being Multiracial is an intersectional identity, in line with MultiCrit’s (Harris, 2016) tenet of intersections of multiple identities, which calls for an exploration of one’s multiple racial heritages beyond their singular social identities. Multiracials are not a monolithic group, as each unique mix has its own history and experiences.

Capitalization of Terms

Finally, we explain why we advocate for the capitalization of the terms “Multiracial” and “Biracial.” The 2010 APA Publication Manual does not mention Multiracial people, but states that, “Racial and ethnic groups are designated by proper nouns and are capitalized” (p. 75). Several Multiracial scholars who consider Multiracial and Biracial to be distinct racial groups therefore treat these words as proper nouns and capitalize them (e.g., Atkin et al., 2021; Franco & Carter, 2019; Sanchez et al., 2021). The 2020 edition of the APA Publication Manual added, “If people belong to multiple racial or ethnic groups, the names of the specific groups are capitalized, but the terms “multiracial,” “biracial,”… are lowercase” (p. 143). We disagree with this recommendation. Franco and Carter (2019), “favor the capitalization of [Multiracial] in recognition of the legitimacy of this racial group as being on par with that of other racial groups” (p. 203). Thus, Multiracial is capitalized by some to validate and empower Multiracial individuals. As Atkin and Jackson (2021) wrote, “Multiracial is capitalized as a proper noun to recognize Multiracial individuals as a distinct, though not exclusive, group of people who share unique racialized experiences and to directly challenge the limiting monoracial structure of existing racial categories” (p. 14). Similarly, Harris (2017) capitalizes Multiracial “to (linguistically) empower the Multiracial participants in this research” (p. 1055). From this perspective, not capitalizing Multiracial delegitimizes the group, making it seem less important in a list of other racial groups (e.g., Black, Asian, multiracial), and demoting the identity status of those who wish to proudly label themselves as “Biracial” or “Multiracial.” As Sanchez and colleagues (2021) wrote, “language is a powerful communicator of legitimacy” (p. 118). It is also practical for distinguishing between, for example, a Multiracial group for mixed race people and a multiracial group with racially diverse members. However, we do not support capitalizing “monoracial,” as this term is not a personal identity that empowers a marginalized group.

However, we do recognize the issues with buying into the system of racial categorization by arguing that Multiracial should be capitalized or classified as its own racial group. As Gullickson and Morning (2010) note, “Any discussion of “multiracial” people implicitly risks essentializing and reifying race by implying that multiraciality results from the mixing of “pure” racial types” (p. 499). Atkin and Jackson (2021) acknowledged that “the system of identifying, using, and capitalizing labels of race perpetuates racial essentialism and ultimately white supremacy” (p. 14). While suggesting that Multiracial should be its own racial group fails to reject the social construction of race, we recognize the reality of how society is racially structured, and the consequences that these categories carry cannot be ignored (Omi & Winant, 1994; Song, 2017). Thus, we choose to empower Multiracial individuals and work to make space for Multiracial people and their unique racialized experiences by challenging the system that has long restricted Multiracials to selecting monoracial categories.

Conclusion

In conclusion, these considerations for understanding and defining race terminology will be useful for advancing the field of psychology’s discussions of race in ways that are inclusive of the rapidly growing Multiracial population in the US. To fulfill the APA’s commitment to solving societal problems and improving lives, there must also be a commitment to achieving racial justice, which requires being intentional in using language and producing research that respects and recognizes oppressed racial groups in society. Adopting more inclusive terms, naming race and racism, and continuing to update our language with the passing of time will help to dismantle the systems that have historically oppressed minoritized communities both within the contexts of psychological research and U.S. society.

Public significance statement:

This paper presents definitions and perspectives on terminology for discussing race and racial groups in the United States. The terms are useful for anyone and attempt to acknowledge power and privilege in our racial systems to ensure that the language recommendations are sensitive to racial inequality in U.S. society.

Funding Source:

This work was supported in part by a predoctoral fellowship provided by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (T32-HD07376) through the Carolina Consortium on Human Development, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, to N. Keita Christophe

Footnotes

Note that in presenting these terms, we are not suggesting that all individuals identify with these self-identification labels.

We do not capitalize the word “white” when referring to concepts such as “white supremacy” and “whiteness,” but do capitalize it when referring to people as prescribed by the APA Publication Manual (2020). The term “White” should be used for people of European ancestry instead of “Caucasian,” as the latter originates from a false scientific theory positing that Caucasians constitute a biologically distinct race (Teo, 2009).

References

- Albuja AF, Sanchez DT, & Gaither SE (2019). Identity denied: Comparing American or White identity denial and psychological health outcomes among Bicultural and Biracial people. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(3), 416–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen VC Jr., Lachance C, Rios-Ellis B, & Kaphingst KA (2011). Issues in the assessment of “race” among Latinos: implications for research and policy. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 33(4), 411–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2010). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (6th edition). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th edition). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong A (2019). “It put me in a really uncomfortable situation”: A need for critically conscious educators in interworldview efforts. Journal of College & Character, 20(2), 172–179. [Google Scholar]

- Ashok S (2016). The rise of the American ‘Others’. The Atlantic https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/08/the-rise-of-the-others/497690/ [Google Scholar]

- Atkin AL, & Jackson KF (2021). “Mom, you don’t get it”: A grounded theory examination of Multiracial youths’ perceptions of parent support. Emerging Adulthood, 9(4), 305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Atkin AL, Jackson KF, White RMB, & Tran AGTT (2021). A qualitative examination of familial racial-ethnic socialization experiences among diverse Multiracial American emerging adults. Journal of Family Psychology. Advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin AL, & Yoo HC (2019). Familial racial-ethnic socialization of Multiracial American youth: A systematic review of the literature with MultiCrit. Developmental Review, 53, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Awad GH, Kia-Keating M, & Amer MM (2019). A model of cumulative racial-ethnic trauma among Americans of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent. American Psychologist, 74(1), 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benet-Martínez V, & Haritatos J (2005). Bicultural identity integration (BII): Components and psychosocial antecedents. Journal of Personality, 73(4), 1015–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betancourt H, & Lopez SR (1993). The study of culture, ethnicity, and race in American psychology. American Psychologist, 48(6), 629–637. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E (2004). From bi-racial to tri-racial: Towards a new system of racial stratification in the USA. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 27(6), 931–950. [Google Scholar]

- Bonilla-Silva E (2015). The structure of racism in color-blind, “post-racial” America. American Behavioral Scientist, 59, 1358–1376. [Google Scholar]

- Bratter JL, & O’Connell HA (2017). Multiracial identities, single race history: Contemporary consequences of historical race and marriage laws for racial classification. Social Science Research, 68, 102–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J (2013). Researching White mothers of mixed-parentage children: The significance of investigating whiteness. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 36(8), 1311–1322. [Google Scholar]

- Cardemil EV, Millan F, & Aranda E (2019). A new, more inclusive name: The Journal of Latinx Psychology. Journal of Latinx Psychology, 7(1), 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Carter G (2013). The United States of the United Races: A utopian history of racial mixing. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cashin S (2017). Loving: Interracial intimacy in American and the threat to white supremacy. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chaney KE, Sanchez DT, & Saud L (2020). White categorical ambiguity: Exclusion of Middle Eastern Americans from the White racial category. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 1–10. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH (2018). Hapa tales and other lies. Rising Song Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen JM, & Hamilton DL (2012). Natural ambiguities: Racial categorization of multiracial individuals. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1), 152–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng C-Y, & Lee F (2009). Multiracial identity integration: Perceptions of conflict and distance among Multiracial individuals. Journal of Social Issues, 65(1), 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cokley K (2007). Critical issues in the measurement of ethnic and racial identity: A referendum on the state of the field. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 224–234. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel GR (2014). Editor’s note. Journal of Critical Mixed Race Studies, 1(1). [Google Scholar]

- Delgado R, & Stefancic J (2012). Critical race theory: An introduction. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donnella L (2016). All mixed up: What do we call people of multiple backgrounds? NPR Code Switch. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2016/08/25/455470334 [Google Scholar]

- Franco M (2019). Let the racism tell you who your friends are: The effects of racism on social connections and life-satisfaction for Multiracial people. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 69, 54–65. [Google Scholar]

- Franco M, & Carter S (2019). Discrimination from family and substance use for Multiracial individuals. Addictive Behaviors, 92, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia SE (2020). Where did BIPOC come from? New York Times. nytimes.com/article/what-is-bipoc.html [Google Scholar]

- Golash-Boza TM (2018). Race & racisms: A critical approach (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Guevarra RP (2012). Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic identities and communities in San Diego. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gullickson A, & Morning A (2011). Choosing race: Multiracial ancestry and identification. Social Science Research, 40, 498–512. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JC (2016). Toward a critical multiracial theory in education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(6), 795–813. [Google Scholar]

- Harris JC (2017). Multiracial campus professionals’ experiences with Multiracial microaggressions. Journal of College Student Development, 58(7), 1055–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Helms JE, Jernigan M, & Mascher J (2005). The meaning of race in psychology and how to change it: A methodological perspective. American Psychologist, 60(1), 27–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs A (2014). A chosen exile: A history of racial passing in American life. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Rodriguez J, Smith EP, Johnson DJ, Stevenson HC, & Spicer P (2006). Parents’ ethnic-racial socialization practices: A review of research and directions for future study. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 747–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes KR, Jones NA, & Ramirez RR (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Jackson KF, & Samuels GM (2019). Multiracial cultural attunement. NASW Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M (2015). Loving Day. Spiegel & Grau. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna N (2010). “If you’re half Black, you’re just Black”: Reflected appraisals and the persistence of the one-drop rule. The Sociological Quarterly, 51, 96–121. [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G (2017). The rise of multiracial and multiethnic babies in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/06/06/the-rise-of-Multiracial [Google Scholar]

- Markus HR (2008). Pride, prejudice, and ambivalence: Toward a unified theory of race and ethnicity. American Psychologist 63, 651–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mio JS, Barker L, Domenech Rodriguez MM, & Gonzalez J (2019). Multicultural psychology: Understanding our diverse communities (5th ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki MH (2016). Part-Latinos and racial reporting in the Census: An issue of question format? Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, 2(3), 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Morning A (2000). Who is Multiracial? Definitions and decisions. Sociological Imagination, 37(4), 209–229. [Google Scholar]

- Morris W (2019). Is Being a ‘Minority’ Really Just a Matter of Numbers? The New York Times Magazine. https://nyti.ms/2S1IZIL [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen AD, & Benet-Martinez V (2013). Biculturalism and adjustment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 44(1), 122–159. [Google Scholar]

- Omi M, & Winant H (2015). Racial formation in the United States. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, Gupta A, Kelaher M, & Gee G (2015). Racism as a Determinant of Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PloS one, 10(9), e0138511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2015). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse and growing in numbers. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america

- Pew Research Center (2020). What census calls us. https://www.pewresearch.org/interactives/what-census-calls-us/

- Pierce L (2000). The continuing significance of race. In Spickard P & Burroughs J (Eds.) We are a people: Narrative and multiplicity in constructing ethnic identity. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Richeson JA, & Sommers SR (2016). Toward a social psychology of race and race relations for the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Psychology, 67, 439–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts D (2011). Fatal Invention. The New Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore KA, & Brunsma DL (2002). Socially embedded identities: Theories, typologies, and processes of racial identity among Black/White biracials. Sociological Quarterly, 43(3), 335–356. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez CE, Miyawaki MH, & Argeros G (2013). Latino racial reporting in the US: To be or not to be. Sociology Compass, 7(5), 390–403. [Google Scholar]

- Rondilla JL, Guevarra RP, & Spickard P (2017). Red & yellow, black & brown: Decentering whiteness in mixed race studies. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez DT, Gaither SE, Albuja AF, & Eddy Z (2020). How policies can address Multiracial stigma. Policy Insights from Behavioral Brain Sciences, 7(2), 115–122. [Google Scholar]

- Saperstein A, Kizer JM, & Penner AM (2016). Making the most of multiple measures: Disentangling the effects of different dimensions of race in survey research. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(4), 519–537. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt RW (2011). American Indian identity and blood quantum in the 21st century: A critical review. Journal of Anthropology, 2011, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Knight GP, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Rivas-Drake D, … Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group (2014). Methodological issues in ethnic and racial identity research with ethnic minority populations. Child Development, 85, 58–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smedley A, & Smedley BC (2005). Race as biology is fiction, racism as a social problem is real: Anthropological and historical perspectives on the social construction of race. American Psychology, 60(1); 16–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song M (2017). Generational change and how we conceptualize and measure multiracial people and “mixture.” Ethnic and Racial Studies, 40(13), 2333–2339. [Google Scholar]

- Song M (2019). Learning from your children: Multiracial parents’ identifications and reflections on their own racial socialization. Emerging Adulthood, 7(2), 119–127. [Google Scholar]

- Spickard PR (2016). Race in Mind. Notre Dame Press. [Google Scholar]

- Squires C, Watts EK, Vavrus MD, Ono KA, Feyh K, Calafell BM, & Brouwer DC (2010). What is this “post-” in postracial, postfeminist… (fill in the blank)? Journal of Communication Inquiry, 34(3), 210–253. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes-Brown AK (2012). America’s Shifting Color Line? Reexamining determinants of Latino racial self-identification. Social Science Quarterly, 93(2), 309–332. [Google Scholar]

- Suyemoto KL, Curley M, & Mukkamala S (2020). What do we mean by “ethnicity” and race”? A consensual qualitative research investigation of colloquial understandings. Genealogy, 4(81), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Lopez MH, Martínez JH, & Velasco G (2012). When labels don’t fit: Hispanics and their views of identity. Pew Hispanic Center. http://latinodonorcollaborative.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Pew-Hispanic-Research-Hispanic-Identity-April-4-2012.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Teo T (2009). Psychology without Caucasians. Canadian Psychology, 50(2), 91–97. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE Jr, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, … & Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85(1), 21–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau (2018). Demographic turning points for the United States. Population projections from 2020 to 2060. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/p25-1144.html [Google Scholar]

- Wang HL (2018, January 26). 2020 Census to keep racial, ethnic categories used in 2010. NPR. npr.org/2018/01/26/580865378 [Google Scholar]

- Woods K (2002). The language of race. Poynter. www.poynter.org/archive/2002/the-language-of-race/. [Google Scholar]

- Wright CD (1900). The history and growth of the United States Census. The U.S. Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/history/pdf/wright-hunt.pdf [Google Scholar]