ABSTRACT

Recovery of microbial synthetic polymers with high economic value and market demand in activated sludge has attracted extensive attention. This work analyzed the synthesis of cyanophycin granule peptide (CGP) in activated sludge and its adsorption capacity for heavy metals and dyes. The distribution and expression of synthetic genes for eight biopolymers in two wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) were analyzed by metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. The results indicate that the abundance and expression level of CGP synthase (cphA) are similar to those of polyhydroxyalkanoate polymerase, implying high synthesis of CGP in activated sludges. CGP in activated sludge is mainly polymerized from aspartic acid and arginine, and its secondary structure is mainly β-sheet. The crude yields of CGP are as high as 104 ± 26 and 76 ± 13 mg/g dry sludge in winter and in summer, respectively, comparable to those of polyhydroxyalkanoate and alginate. CGP has a stronger adsorption capacity for anionic pollutants (Cr (VI) and methyl orange) than for cationic pollutants because it is rich in guanidine groups. This study highlights prospects for recovery and application of CGP from WWTPs.

IMPORTANCE The conversion of organic pollutants into bioresources by activated sludge can reduce the carbon dioxide emission of wastewater treatment plants. Identification of new high value-added biopolymers produced by activated sludge is beneficial to recover bioresources. Cyanophycin granule polypeptide (CGP), first discovered in cyanobacteria, has unique chemical and material properties suitable for industrial food, medicine, cosmetics, water treatment, and agriculture applications. Here, we revealed for the first time that activated sludge has a remarkable ability to produce CGP. These findings could further facilitate the conversion of wastewater treatment plants into resource recycling plants.

KEYWORDS: biopolymer, cyanophycin, polyhydroxyalkanoate, activated sludge, bioresource recovery

INTRODUCTION

The annual output of polymers worldwide exceeds 300 million tons and consumes ~6% of the crude oil production, which is expected to increase to 20% by 2050 (1). Microbial polymers as alternative polymer sources can reduce the dependence on crude oil. However, production of commercial biopolymers by bacterial fermentation needs expensive substrates and substantial investment into capital equipment, which is less economic than extracting from nature and chemical synthesis (2). Microorganisms in wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) can synthesize many biopolymers, including polysaccharides, proteins, polyesters, and polyamides, intracellularly or extracellularly (3). Therefore, WWTPs have increasingly attracted investigation and commercial interest as resource recovery plants.

In recent decades, the investigation or application of biopolymer recovery, including polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), cellulose, and alginate, has been extensive (4). These biopolymers, which contribute to the circular economy, are applied as bioplastics, hydrogel coating materials, and biosorbent materials (5, 6). However, the biosynthetic pathways of PHA, alginate and cellulose, are complex, and the regulatory mechanisms in the complex microbial community remain unclear (7–9). Biopolymer yield is affected by different wastewater characteristics and operating conditions. The alginate crude yield is 32 to 240 mg/g volatile suspended solids (VSS) in granular sludge and only 42 to 95 mg/g VSS in floc sludge (10, 11). In addition, the structure and purity of recycled biopolymers do not meet the current market standards, which is a significant limiting factor (12). The PHA produced from WWTPs is mainly a mixture of different chain lengths, whereas single monomer PHA has better functionality and occupies the main market (13). In short, these biopolymers still face a recovery dilemma to some extent (14). Therefore, the recognition and recovery of new biopolymers with high economic value, and market demand to further promote the conversion of WWTPs into resource recovery plants, are urgent (15).

Biopolymer identification is usually performed by spectroscopy, gas/liquid chromatography, mass spectrometry (MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (16). However, biopolymers synthesized in activated sludge are complex, heterogeneous, and variable, making the characterization of their components and structures very challenging (17). The complexity of the biopolymer structure and variability of molecular weight increase the difficulty of finding new biopolymers in WWTPs. Exploring the distribution and expression of biopolymer synthesis genes is an effective means of predicting the existence of biopolymers (18). Currently, metagenomics and metatranscriptomics are widely used to analyze the functional genes and predict the microbial products in complex microbial communities (19). Therefore, these meta-omics methods help discover neglected high value-added polymers and elucidate their synthesis pathway.

In this work, the synthesis of cyanophycin granule peptide (CGP) in two wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) and its application in adsorption of pollutants were investigated. The synthesis potential of alginate, cellulose, hyaluronic acid (HA), xanthan, succinoglycan, PHA, poly-γ-glutamic acid (γ-PGA), and CGP in activated sludge was analyzed by metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. We found that the abundance and expression levels of CGP synthases (cphA) are similar to those of PHA, demonstrating the high production potential of CGP. CGP was then extracted from activated sludge and characterized using a variety of techniques. CGP yield was compared with that of other biopolymers. In addition, the adsorption capacities for heavy metals and dyes were studied to exploit its application potential in water/wastewater treatment. Overall, this study is the first to report considerable CGP synthesis in WWTPs and further advances the development of high value-added resource recovery from WWTPs.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Biosynthesis potential of CGP in activated sludge.

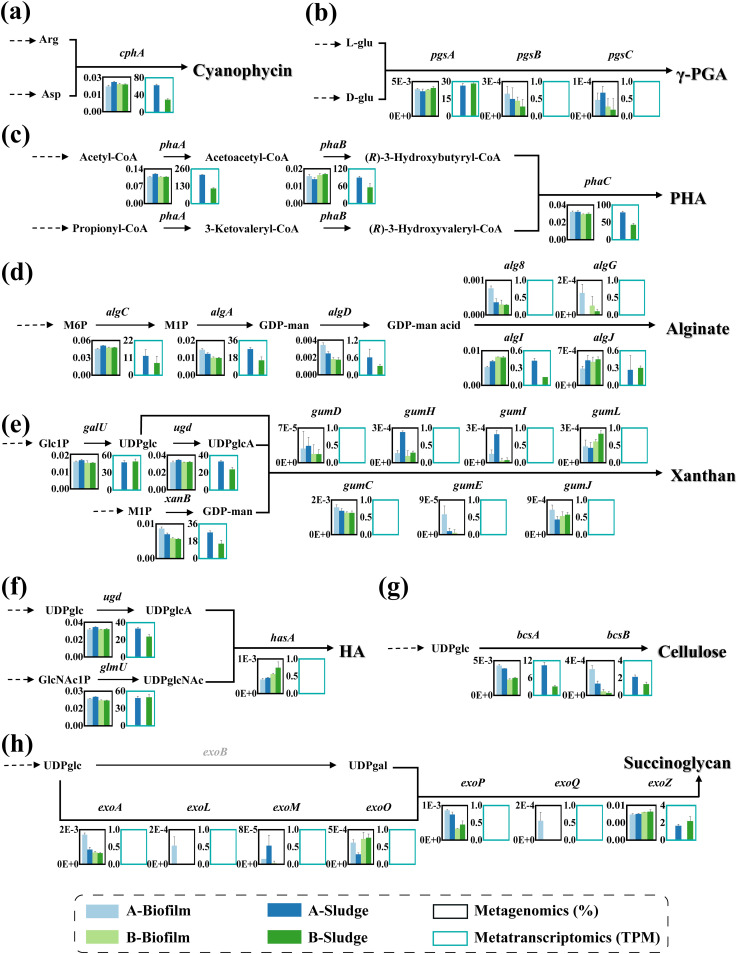

(i) Synthetic potential of CGP approximates PHA. Figure 1 shows the gene abundances and expression and the biosynthesis pathways of eight biopolymers including two polyamides (CGP [cphA] and γ-PGA [pgsA, pgsB, and pgsC]), one polyester (PHA [phaA, phaB, and phaC]), and five exopolysaccharides (alginate [algC, algA, algD, alg8, algG, algI, and algJ], cellulose [bcsA and bcsB], HA [ugd, glmU, and hasA], xanthan [galU, ugd, xanB, gumD, gumC, gumE, gumH, gumI, gumJ, and gumL], and succinoglycan [exoA, exoL, exoM, exoO, exoP, exoQ, and exoZ]), according to metagenomics and metatranscriptomics. The results indicate that the activated sludge can simultaneously synthesize multiple high value-added biopolymers (20). The synthesis ability of activated sludge was evaluated for each biopolymer on the basis of the abundances and gene expression of synthase or polymerase. The synthase/polymerase gene abundances and expression in decreasing order are phaC > cphA > bcsA > alg8 ≈ hasA > pgsB > exoQ > gumE, and phaC > cphA > bcsA, respectively. Among them, expression of alg8, hasA, pgsB and pgsC, exoQ, and gumE were not detected. For polyester and polyamides, the abundances and expression levels of cphA and phaC were the highest. In wastewater resource recovery, PHA has aroused extensive research enthusiasm in the past decade as a substitute for bioplastics, and high PHA production requires high phaC expression (21). In contrast, CGP in activated sludge has rarely been reported. For exopolysaccharides, the abundances of genes hasA, exoQ, and alg8 are similar but lower than those of bcsA. The low abundance of gumE indicates that xanthan may not be the dominant exopolysaccharide in WWTPs.

FIG 1.

Abundances and expression of synthetic genes and proposed synthesis pathway of eight biopolymers in activated sludges based on metagenomics and metatranscriptomics: CGP (a), γ-PGA (b), PHA (c), alginate (d), xanthan (e), HA (f), cellulose (g), and succinoglycan (h).

Alginate, cellulose, and PHA have been found or recovered from WWTPs (11, 15, 22). The catalytic process of GDP-mannose dehydrogenase (algD) is the major rate-limiting step in alginate biosynthesis (23). Low expression of algD in activated sludge (transcripts per million [TPM] = ~0.47) may limit production of alginate. Moreover, the expression of alg8 is undetected, indicating that the alginate production/productivity rate may be relatively low in activated sludge. As reported by Chen et al. (24), the alginate equivalent in algal-bacterial aerobic granular sludge is approximately 9 mg/g VSS. During cellulose biosynthesis, cellulose synthase polymerizes UDP-glucose to nascent b-D-1,4-glucan chain to form cellulose. BcsA and BcsB play a key role in cellulose synthesis, but the expression levels of these two enzymes in activated sludge (TPMbcsA = ~6.7; TPMbcsB = ~1.7) are low. PHA synthesis includes three pathways (7). The main carbon source of PHA synthesis is carbohydrate in aerobic conditions and fatty acids (and their degradation products) in anaerobic conditions (22). According to metagenomics and metatranscriptomics, PHA in floc sludge and biofilm was mainly made by the acetoacetyl-CoA pathway (phaA, phaB, and phaC), suggesting that the main carbon source for PHA synthesis in aerobic sludge is carbohydrates.

CGP was first discovered in cyanobacteria as a nitrogen-rich reserve polymer (25). CGP synthesis only requires one step, namely, the polymerization of Asp and Arg with the catalysis of CGP synthase (CphA) (26). CGP can be synthesized by the heterologous expression of cphA using Asp and Arg as substrates in engineered strains, including Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas putida, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Rhizopus oryzae, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae (27). Interestingly, the gene abundance and expression level of cphA (relative abundance = 0.02%; TPM = 29.4 to 62.6) are similar to those of phaC (relative abundance = 0.03%; TPM = 43.2 to 78.7), indicating that WWTPs have considerable CGP production ability.

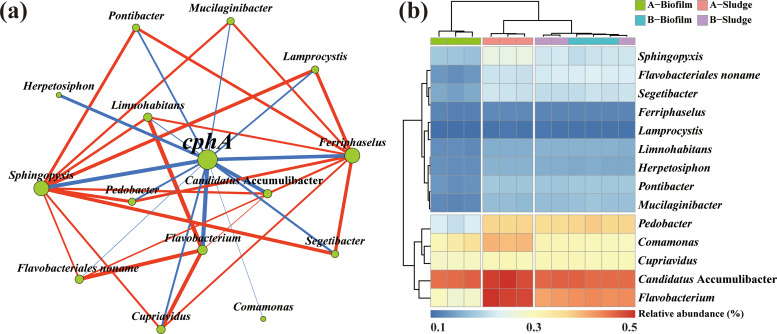

(ii) Potential host of cphA in activated sludge. Activated sludge biopolymers are produced by microorganisms; thus, potential hosts for cphA must be elucidated. As shown in Fig. 2, on the basis of the annotation results of the same contigs in the KEGG and nr databases, and according to co-occurrence network analysis, 14 potential hosts of cphA were screened (r > 0.6, P < 0.05, r is Spearman correlation coefficient). Among them, the relative abundances of Flavobacterium, Candidatus Accumulibacter, Cupriavidus, Comamonas, and Pedobacter as dominant potential hosts for cphA are all higher than 0.3%, unlike the previously reported Acinetobacter sp., Bordetella bronchiseptica, and Clostridium botulinum (27). This phenomenon indicates that other species can synthesize CGP in WWTPs. For example, cphA was found in ammonia-oxidizing Nitrosomonas europaea (28). Some investigations indicated that the synergistic interaction between different microorganisms improves the utilization efficiency of substrates, promoting production of biopolymers (29). Arg and Asp as common substrates for CGP synthesis can achieve transmembrane transport. In WWTPs, Arg and Asp can be derived from wastewater or synthesized by other activated sludge microorganisms (30). Therefore, the synergistic effect between the activated sludge microorganisms might improve the production of CGP (31).

FIG 2.

(a) Co-occurrence network between cphA and potential hosts. (b) Relative abundance of cphA potential hosts at genus levels. (Node size represents the degree of connection, and edge thickness represents the size of the correlation; P < 0.05).

A significant positive correlation was found between Candidatus Accumulibacter and cphA (r = 0.863, P < 0.01). As a typical phosphorus accumulating bacteria, Candidatus Accumulibacter also plays an important role in the process of phosphorus removal from WWTPs. Furthermore, Candidatus Accumulibacter is a potential host of phaC (Fig. S1) and was reported capable of accumulating PHA (32). Therefore, the simultaneous recovery of intracellular CGP and PHA from activated sludge is also feasible.

CGP in activated sludge are mainly polymerized from Asp and Arg.

To further explore the evidence of CGP in activated sludge, multiple approaches were adopted to identity the composition and property of CGP. As shown in Fig. 3a and b, CGP is an insoluble dark green gelatinous substance at pH 7.5. According to previous study (33), the activated sludge CGP was stained using the Sakaguchi reaction (arginine reacts with α-naphthol in the presence of sodium hypochlorite to give a red product). The moist CGP gel was stained red as shown in Fig. 3c and is consistent with that extracted from Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803 (33). This result demonstrates the presence of Arg in CGP. To determine the main amino acid species of CGP, HPLC-MS was performed to identity the hydrolysates of CGP extracted from four activated sludge samples. As shown in Fig. 3e, the hydrolysates of all the four samples have obvious absorption peaks around 3 and 17 min, which correspond to Asp and Arg, respectively. The MS results (Fig. 3f) further prove the existence of Arg (m/z = 310.11) and Asp (m/z = 269.1). However, Lys was also found in the acid hydrolysate of the activated sludge CGP (Fig. S2). Several studies have shown that Lys, Cit, and Orn replace Arg and polymerize with Asp to form CGP and affect its solubility (34).

FIG 3.

Identification and characterization of CGP from four activated sludge samples. (a) Image of CGP suspension at pH 7.5. (b) Image of CGP gels. (c) Image of Sakaguchi reaction of CGP. (d) HPLC analysis of Asp and Arg. (e) HPLC analysis of CGP hydrolysate. (f) Positive Ion ESI-MS analysis of Arg and Asp from CGP hydrolysate. (g) UV–vis absorption spectra of CGP. (h) FTIR of CGP. (i) Curve-fitted amide I region (1,700 to 1,600 cm−1) of CGP FTIR.

Activated sludge CGP spectral characteristics in different samples were also investigated. In Fig. 3g, the CGP does not show an obvious absorption peak in the range of 200 to 800 nm. The strong polarity of the CGP molecules leads to weak UV absorption. However, an indistinct UV absorption peak at 195 to 198 nm was observed, which was also reported by Ziegler et al. (35), and may be the terminal absorption caused by the n → σ* transition. As shown in Fig. 3h, the infrared (IR) peaks of the extracted CGP appeared around 3,445 cm−1 (O–H), 1,645 cm−1 (C = O), 1,545 cm−1 (N–H), 1,381 cm−1 (COO–), and 928 to 1,047 cm−1 (C–O). The peaks of the amide bonds appeared at 1,620 cm−1, and the peak at 1,159 cm−1 is assigned to the C–N bonds from the guanidyl groups. The results demonstrate that the CGP from four samples have similar IR absorption peak positions but different peak intensity ratios, indicating that these CGPs may have different monomer compositions.

The secondary structures of the CGP were also revealed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR). As can be seen from Fig. 3i, the amide I band (C = O stretching) at 1,700 to 1,600 cm−1 was processed by deconvolution. The bands located at 1,695 to 1,675 cm−1 are assigned to aggregated strands. The characteristic band for α-helical conformation is located at 1,670 to 1,645 cm−1. The bands at 1,645 to 1,640 cm−1 are assigned to random coil structures. The bands at 1,640 to 1,610 cm−1 are expected for β-sheet components (36). The results show that β-sheet was the main secondary structure, accounting for 61%, 57%, 54%, and 54% in A-Biofilm, A-sludge, B-Biofilm, and B-Sludge, respectively. Simon et al. (37) also confirmed through Raman spectroscopy and circular dichroism that the main structure of the CGP in Anabaena cylindrica is β-sheet. These findings indicate that the composition of the CGP extracted from activated sludge is similar with that produced by reported strains.

Comparable crude yields of CGP with those of alginate and PHA.

To validate the metagenomics and metatranscriptomics results, six biopolymers including cellulose, alginate, HA, PHA, γ-PGA, and CGP, were extracted from activated sludge samples (including winter and summer samples), and their crude dry weights were determined as shown in Fig. 4a (winter samples) and Fig. 4b (summer samples). The biopolymer compositions of the activated sludge and commercial sources were compared using FTIR (Fig. S4a to S4e). The alginate extracted from the biofilm and floc sludge samples in WWTP-A reached 46 and 23 mg/g in dry sludge in winter and 72 and 42 mg/g in dry sludge in summer, respectively. The main absorption peaks of commercial and extracted alginate are consistent, implying that their compositions are similar (Fig. S4). The yields of alginate from the floc sludge and biofilm summer samples were half of those reported by Li et al. (38) and even less from the winter samples. This difference can be attributed to the different wastewater characteristics or temperature (24).

FIG 4.

Crude yields of the five biopolymers extracted from activated sludges at winter (a) and summer (b).

The extracted yields of cellulose are equivalent to those of alginate. However, the actual yield of cellulose may be lower than that of alginate because it is insoluble and does not undergo dialysis. Figure S4b also shows that the extracted celluloses differed greatly from the commercial cellulose in the region below 1,200 cm−1, suggesting the presence of impurities. Although the abundance and expression level of cellulose synthase are higher than those of alginate synthase, the high expression of cellulases (endoglucanases, exoglucanases, and β-glucosidases) may cause cellulose decomposition (Fig. S3).

The yields of HA in the two WWTPs range from 12 to 43 mg/g dry sludge weight. The extracted HA has a similar FTIR spectra (Fig. S4c). Compared with commercial HA, the absorption peak of the extracted HA shifted from 1,629 cm−1 to 1,580 cm−1 due to the carboxylate formation (15). The synthase abundance, expression, and yields of γ-PGA were very low in the activated sludge. The FTIR spectra of the commercial and extracted γ-PGA were quite different (Fig. S4d), indicating that the extracted γ-PGA may be of low purity. These results suggest that the recovery potential of γ-PGA is low. The crude yield of PHA was highly affected by the season, with 58 and 26 mg/g dry sludge weight in winter and summer, respectively, probably because low temperatures help accumulate PHA (39). The IR absorption peak positions of the extracted and commercial PHA were close, but their intensities varied greatly (Fig. 4f). The strong peaks around 2,962, 2,924, and 2,856 cm−1 are ascribed to the C–H of the extracted PHA, implying the abundant fat acid chains.

The crude yields of CGP in WWTPs range from tens to more than 100 mg/g dry sludge (Fig. 4a and b). Assuming a MLSS ranging from 2 to 3 g/L, the CGP yields in WWTPs can reach 139 to 347 mg/L. This amount is quite impressive compared to the yields of Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803, Cyanothece sp. ATCC 51142, and Acinetobacter sp. strain ADP1 (40). The extraction of biopolymers from WWTPs is more economical than bacterial fermentation (41). These data indicate that the crude yield of CGP is at the same level as those of alginate and PHA, suggesting that WWTPs are an important source of CGP resources. The abundance of cphB (encoding cyanophycinase) was 0.01% to 0.02%. In order to promote the accumulation of CGP, methods of inhibiting cyanophycinase activity need to be developed in future studies.

Adsorption properties of CGP.

CGP is an amphoteric molecule that is rich in carboxyl and guanidine/amino groups. Thus, the adsorption capacity for anionic and cationic heavy metals and dyes of CGP was evaluated to better elucidate the application potential of CGP in water treatment. As shown in Fig. 5a, under the initial Cr2O72− concentration of 50 mg/L, the adsorption equilibrium could be reached in 18 min, and the adsorption capacity was ~31 mg/g. The adsorption rate is higher than that of inorganic materials such as Mn-incorporated ferrihydrite and biochar-based iron oxide composites (42, 43). The CGP adsorption capacity is also higher than that of chitosan/triethanolamine/Cu (II) composite adsorbent (44). The adsorption process conforms to pseudo-first-order kinetics, indicating that the adsorption process is accompanied by physical adsorption and chemical adsorption. The binding energy of CGP for Cr2O72− was calculated based on density functional theory (DFT). Figure 5b shows that the two N–Cr bond lengths are 3.581 and 3.959 Å in the binding configuration, and the O–Cr bonds are changed from 1.814 Å to 1.805 Å. The binding energy is −9.350 eV, indicating a stable N–Cr bond. However, the equilibrium adsorption capacities for metal ions Pb2+ and Cd2+ by CGP were only ~17 and ~14 mg/g, respectively, much lower than those of Cr (VI) at the initial concentration (Fig. S4). The experimental results show that CGP has a stronger ability to remove anionic metal ions than cationic metal ions.

FIG 5.

Adsorption dynamics of Cr2O72− and methyl orange by CGP from different activated sludge samples. (a) The adsorption of Cr2O72− by CGP at pH 5. (b) The optimized binding configuration of Cr2O72− and amidogen group with Cr2O72−. (c) The adsorption of methyl orange by CGP at pH 1 and pH 5.

Figure 5c and Fig. S5 show the adsorption properties of CGP for methylene blue and methyl orange at pH 1 and pH 5, respectively. Similar to metal ions, CGP has stronger advantages in removing anionic dye methyl orange than cationic dye methylene blue. The initial methyl orange concentration was 50 mg/L, and the adsorption equilibrium (24 mg/g) was reached within 1.2 h under pH 5. At pH 5, the CGP was positively charged due to protonation of guanidine groups, which is favorable for adsorbing anionic pollutants. The dissociation constant (pKa) for methyl orange is 3.46, indicating that methyl orange molecules were mainly present as monovalent anions. Under the circumstances, the adsorbing capacity of CGP for methyl orange declined due to the electrostatic repulsion between protonated methyl orange and positively charged CGP. In addition, the adsorption capacities of the CGP extracted from different sludges are similar, indicating that activated sludge could be a stable source of CGP-based adsorbent material.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial source.

Floc sludge and biofilm samples were collected from the aeration tanks of municipal WWTPs in Xiangtan (WWTP-A) and Zhuzhou (WWTP-B) China, respectively. The main processes of WWTP-A and WWTP-B are anaerobic-anoxic-oxic integrating aerobic moving bed biofilm reactor (AAO-MBBR) and AAO integrating membrane bioreactor (AAO-MBR), respectively. The qualities and relevant operational parameters of the two WWTPs are shown in Table S1. Floc sludge samples and biofilm samples were collected from different aeration tanks (floc sludge samples were from aerobic tanks, biofilm samples were from moving bed biofilm reactors for WWTP-A and from membrane bioreactors for WWTP-B), and three samples were collected from three different locations in each aeration tank. The collected samples were stored in a dark icebox during transport to the laboratory.

Metagenomics analysis.

The metagenomics analysis was performed by Sangon Biotech (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. The genomic DNAs from the floc sludge and biofilm samples were extracted using the E.N.A. Soil DNA Kit (OMEGA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The genomic DNAs integrity was examined by agarose gel electrophoresis (1% agarose, voltage: 220 V, time: 30 min). The DNA libraries were sequenced on HiSeq-PE1500 (Illumina). FastQC (version 0.11.2) and Trimmomatic (version 0.36) were used on the metagenomic sequencing data for quality control. IDBA_UD (version 1.1.2) and MEGAHIT (version 1.0) were used to splice the reads of the sequencing data. Prodigal (version 1.1.2) and MetaGeneMark (version 3.26) were used to predict the open reading frame of the contigs in the sequencing data and translate them into amino acid sequences. In the metagenomic sequencing data, Bowtie2 (version 2.1.0) was used to align the clean reads of each sample to the sequence of the nonredundant gene set, SAMtools (version 0.1.18) was used to obtain the reads on the alignment, and the gene length was used to calculate the abundance information of the gene in each sample.

Metatranscriptomics analysis.

The total RNA of floc sludge samples from WWTP-A and WWTP-B was extracted using the RNeasy PowerMicrobiome kit (Qiagen, Germany) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was submitted for DNase treatment to remove DNA contaminants using the DNase Max kit (Qiagen, Germany). RNA integrity was checked using agarose gel electrophoresis (1% agarose; voltage: 5 V/cm; time: 15 min). rRNA was removed from the total RNA using Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kits (Illumina, USA). The RNA libraries were sequenced on HiSeq-PE1500 (Illumina) and a HiSeq xten sequencer (Illumina). Cutadapt (version 1.12) and BWA were used on the matetranscriptomics data for quality accusation and de-hosting. The gene expression level was calculated by using the number of clean reads aligned to the reference genome region. The Kallisto (version 0.44.0) software was used to calculate the amount of each gene/transcript in the sample. The TPM value was taken as the expression level of the gene/transcript in the sample.

The gene set was compared with the nr, KEGG, and SEED databases to obtain gene species annotation information and functional annotation information.

Extraction and analysis of biopolymer.

Biopolymers were extracted from floc sludge and biofilm according to the existing extraction methods. Before biopolymer extraction, activated sludge samples were freeze-dried, ground, and passed through 1-mm sieve to remove inorganic particles. Alginate was extracted using sodium carbonate extraction (11). Cellulose was extracted using the combined ultrasonic-enzymatic hydrolysis-H2O2-KOH treatment (45). HA extraction was performed according to the method described by Felz et al. (15). γ-PGA isolation was carried out using modified methanol–ethanol fractional precipitation (46). CGP was isolated based on the concentrated HCl method (47, 48). PHA was extracted from the biomass using chloroform treatment (49). The specific separation procedures of these biopolymers are described in Text S1. The FTIR spectra of each extracted biopolymer and the commercial polymers purchased from Macklin (Shanghai, China) were determined using a FTIR spectrophotometer (Nicolet 380, USA) with recording over a frequency range of 4,000 to 400 cm−1.

Identification of CGP.

The UV–vis absorption spectra were recorded on a UV-2550 spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Japan). As described by Fevzioglu et al. (36), the CGP spectra were used for Gaussian/Lorentzian curve-fitting using the PeakFit v4.12 software (SeaSolve, USA). The CGP extracted from the activated sludge was hydrolyzed using hydrochloric acid and then quantified through ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) analysis with a C18 reversed-phase column (5 μm, 2.1 × 150 mm; Agilent) coupled with a UV detector set at 254 nm. Amino acid analysis was performed by MS with 50 mM ammonium acetate and 40% methanol as the mobile phases. The MS system used was a Finnigan LXQ ion trap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). MS was conducted in the electron spray ionization mode (ESI) using positive polarity. Scanning was performed at 100 to 350 Da.

Adsorption of heavy metals and dyes by CGP.

The adsorption experiments on CGP (1 mg/mL) are performed in solution. Pb(NO3)2, Cd(NO3)2, and K2Cr2O7 were selected, and 50 mg/L each of Pb2+, Cd2+, Cr (VI), methyl orange, and methylene blue were prepared using deionized water. The experimental samples were incubated in a shaker at 120 rpm and 25°C. Metal ion adsorption experiment (pH 5) and dye adsorption experiment (pH 1 or pH 5) were conducted.

Computing method.

The Shannon–Wiener and Simpson indexes were used to characterize the species and gene diversities of the samples (Table S2). Student's t test was used to test the statistical significance, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. The above process was carried out in R 3.6.3.

According to spin-polarized DFT, binding energy calculation was performed in the DMol3 module in the Materials Studio 2017 software. GAA/PBE functionals and dual numerical polarization (DNP) basis were used. The orbital cutoff of atoms was 4.5 Å. Adsorption binding energy is the difference between the steady-state binding and aggregate energies of the isolated adsorbent and adsorbate. An explicit model (COSMO) was adopted to simulate the aqueous layer coating of the material during adsorption (the dielectric constant is 78.54) (50). In addition, the convergence tolerances for the geometric optimization calculations were set to a maximum displacement of 0.005 Å, a maximum energy change of 1.0 × 10−5 eV/atom, and a maximum force of 0.08 eV/Å.

Data availability.

The raw DNA sequences data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (accession no. CRA003823). The raw RNA sequences data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (accession no. CRA007158).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51708475 and 21777135), Research Foundation of Education Bureau of Hunan Province, China (20B585), and the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province, China (2021JJ30664, 2022JJ50131).

We thank Huang Li (Shanghai Bioprofile Technology Company Ltd.) for helping with data analysis.

We declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Peng Zhang, Email: pzhang@xtu.edu.cn.

Jennifer B. Glass, Georgia Institute of Technology

REFERENCES

- 1.Payne J, McKeown P, Jones MD. 2019. A circular economy approach to plastic waste. Polym Degrad Stab 165:170–181. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2019.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rehm BH. 2010. Bacterial polymers: biosynthesis, modifications and applications. Nat Rev Microbiol 8:578–592. 10.1038/nrmicro2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yu HQ. 2020. Molecular insights into extracellular polymeric substances in activated sludge. Environ Sci Technol 54:7742–7750. 10.1021/acs.est.0c00850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kehrein P, van Loosdrecht M, Osseweijer P, Garf M, Dewulf J, Posada J. 2020. A critical review of resource recovery from municipal wastewater treatment plants–market supply potentials, technologies and bottlenecks. Environ Sci Water Res Technol 6:877–891. 10.1039/C9EW00905A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feng C, Lotti T, Canziani R, Lin Y, Tagliabue C, Malpei F. 2021. Extracellular biopolymers recovered as raw biomaterials from waste granular sludge and potential applications: a critical review. Sci Total Environ 753:142051. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang P, Xu XY, Zhang XL, Zou K, Liu BZ, Qing TP, Feng B. 2021. Nanoparticles-EPS corona increases the accumulation of heavy metals and biotoxicity of nanoparticles. J Hazard Mater 409:124526. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang X, Lin Y, Wu Q, Wang Y, Chen GQ. 2020. Synthetic biology and genome-editing tools for improving PHA metabolic engineering. Trends Biotechnol 38:689–700. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2019.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitney JC, Howell PL. 2013. Synthase-dependent exopolysaccharide secretion in Gram-negative bacteria. Trends Microbiol 21:63–72. 10.1016/j.tim.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Romling U, Galperin MY. 2015. Bacterial cellulose biosynthesis: diversity of operons, subunits, products, and functions. Trends Microbiol 23:545–557. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amorim de Carvalho C, Ferreira Dos Santos A, Tavares Ferreira TJ, Sousa Aguiar Lira VN, Mendes Barros AR, Bezerra Dos Santos A. 2021. Resource recovery in aerobic granular sludge systems: is it feasible or still a long way to go? Chemosphere 274:129881. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schambeck CM, Magnus BS, de Souza LCR, Leite WRM, Derlon N, Guimaraes LB, da Costa RHR. 2020. Biopolymers recovery: dynamics and characterization of alginate-like exopolymers in an aerobic granular sludge system treating municipal wastewater without sludge inoculum. J Environ Manage 263:110394. 10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van Loosdrecht MC, Brdjanovic D. 2014. Water treatment. Anticipating the next century of wastewater treatment. Science 344:1452–1453. 10.1126/science.1255183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shahid S, Razzaq S, Farooq R, Nazli ZI. 2021. Polyhydroxyalkanoates: next generation natural biomolecules and a solution for the world’s future economy. Int J Biol Macromol 166:297–321. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.10.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Izadi P, Izadi P, Eldyasti A. 2021. Holistic insights into extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) in anammosx bacterial matrix and the potential sustainable biopolymer recovery: a review. Chemosphere 274:129703. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.129703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felz S, Neu TR, van Loosdrecht MCM, Lin Y. 2020. Aerobic granular sludge contains Hyaluronic acid-like and sulfated glycosaminoglycans-like polymers. Water Res 169:115291. 10.1016/j.watres.2019.115291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang P, Chen YP, Qiu JH, Dai YZ, Feng B. 2019. Imaging the microprocesses in biofilm matrices. Trends Biotechnol 37:214–226. 10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boleij M, Pabst M, Neu TR, van Loosdrecht MCM, Lin Y. 2018. Identification of glycoproteins isolated from extracellular polymeric substances of full-scale anammox granular sludge. Environ Sci Technol 52:13127–13135. 10.1021/acs.est.8b03180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seviour T, Derlon N, Dueholm MS, Flemming HC, Girbal-Neuhauser E, Horn H, Kjelleberg S, van Loosdrecht MCM, Lotti T, Malpei MF, Nerenberg R, Neu TR, Paul E, Yu H, Lin Y. 2019. Extracellular polymeric substances of biofilms: suffering from an identity crisis. Water Res 151:1–7. 10.1016/j.watres.2018.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu X, Heal KR, Ingalls AE, Doxey AC, Neufeld JD. 2020. Metagenomic and chemical characterization of soil cobalamin production. ISME J 14:53–66. 10.1038/s41396-019-0502-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hao X, Wu D, Li J, Liu R, van Loosdrecht M. 2022. Making Waves: a sea change in treating wastewater–why thermodynamics supports resource recovery and recycling. Water Res 218:118516. 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ren Q, van Beilen JB, Sierro N, Zinn M, Kessler B, Witholt B. 2005. Expression of PHA polymerase genes of Pseudomonas putida in Escherichia coli and its effect on PHA formation. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 87:91–100. 10.1007/s10482-004-1360-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tu W, Zhang D, Wang H, Lin Z. 2019. Polyhydroxyalkanoates (PHA) production from fermented thermal-hydrolyzed sludge by PHA-storing denitrifiers integrating PHA accumulation with nitrate removal. Bioresour Technol 292:121895. 10.1016/j.biortech.2019.121895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hay ID, Ur Rehman Z, Moradali MF, Wang Y, Rehm BH. 2013. Microbial alginate production, modification and its applications. Microb Biotechnol 6:637–650. 10.1111/1751-7915.12076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen X, Wang J, Wang Q, Yuan T, Lei Z, Zhang Z, Shimizu K, Lee DJ. 2022. Simultaneous recovery of phosphorus and alginate-like exopolysaccharides from two types of aerobic granular sludge. Bioresour Technol 346:126411. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Simon RD. 1971. Cyanophycin granules from the blue-green alga Anabaena cylindrica: a reserve material consisting of copolymers of aspartic acid and arginine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 68:265–267. 10.1073/pnas.68.2.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharon I, Haque AS, Grogg M, Lahiri I, Seebach D, Leschziner AE, Hilvert D, Schmeing TM. 2021. Structures and function of the amino acid polymerase cyanophycin synthetase. Nat Chem Biol 17:1101–1110. 10.1038/s41589-021-00854-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elbahloul Y, Krehenbrink M, Reichelt R, Steinbuchel A. 2005. Physiological conditions conducive to high cyanophycin content in biomass of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus strain ADP1. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:858–866. 10.1128/AEM.71.2.858-866.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Krehenbrink M, Oppermann-Sanio FB, Steinbuchel A. 2002. Evaluation of non-cyanobacterial genome sequences for occurrence of genes encoding proteins homologous to cyanophycin synthetase and cloning of an active cyanophycin synthetase from Acinetobacter sp. strain DSM 587. Arch Microbiol 177:371–380. 10.1007/s00203-001-0396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ju F, Zhang T. 2015. Bacterial assembly and temporal dynamics in activated sludge of a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant. ISME J 9:683–695. 10.1038/ismej.2014.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Su RJ, Shi PH, Zhu MC, Zhang WF, Hong F, Li DX. 2013. Analysis of free amino acids in waste-activated sludge protease hydrolysate by a simple and accurate Rp-Hplc method. Fresenius Environ Bull 22:818–823. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shi Z, Campanaro S, Usman M, Treu L, Basile A, Angelidaki I, Zhang S, Luo G. 2021. Genome-centric metatranscriptomics analysis reveals the role of hydrochar in anaerobic digestion of waste activated sludge. Environ Sci Technol 55:8351–8361. 10.1021/acs.est.1c01995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu WT, Nielsen AT, Wu JH, Tsai CS, Matsuo Y, Molin S. 2001. In situ identification of polyphosphate- and polyhydroxyalkanoate-accumulating traits for microbial populations in a biological phosphorus removal process. Environ Microbiol 3:110–122. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watzer B, Engelbrecht A, Hauf W, Stahl M, Maldener I, Forchhammer K. 2015. Metabolic pathway engineering using the central signal processor PII. Microb Cell Fact 14:192. 10.1186/s12934-015-0384-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steinle A, Bergander K, Steinbuchel A. 2009. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for production of novel cyanophycins with an extended range of constituent amino acids. Appl Environ Microbiol 75:3437–3446. 10.1128/AEM.00383-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziegler K, Deutzmann R, Lockau W. 2002. Cyanophycin synthetase-like enzymes of non-cyanobacterial eubacteria: characterization of the polymer produced by a recombinant synthetase of Desulfitobacterium hafniense. Z Naturforsch C J Biosci 57:522–529. 10.1515/znc-2002-5-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fevzioglu M, Ozturk OK, Hamaker BR, Campanella OH. 2020. Quantitative approach to study secondary structure of proteins by FT-IR spectroscopy, using a model wheat gluten system. Int J Biol Macromol 164:2753–2760. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simon RD, Lawry NH, McLendon GL. 1980. Structural characterization of the cyanophycin granule polypeptide of Anabaena cylindrica by circular dichroism and raman spectroscopy. Biochim Biophys Acta 626:277–281. 10.1016/0005-2795(80)90121-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li J, Hao X, Gan W, van Loosdrecht MCM, Wu Y. 2021. Recovery of extracellular biopolymers from conventional activated sludge: potential, characteristics and limitation. Water Res 205:117706. 10.1016/j.watres.2021.117706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang F, Xu RZ, Huang YQ, Luo JY, Xie WM, Ni BJ, Cao JS. 2021. Exploring the feasibility of nitrous oxide reduction and polyhydroxyalkanoates production simultaneously by mixed microbial cultures. Bioresour Technol 342:126012. 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.126012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Watzer B, Forchhammer K. 2018. Cyanophycin synthesis optimizes nitrogen utilization in the unicellular cyanobacterium Synechocystis sp. strain PCC 6803. Appl Environ Microbiol 84(20):e01298-18. 10.1128/AEM.01298-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Daigger G, Lee DJ, Liu J, Ren NQ, Qu J, Liu G, Butler D. 2018. Evolving wastewater infrastructure paradigm to enhance harmony with nature. Sci Adv 4:eaaq0210. 10.1126/sciadv.aaq0210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liang C, Fu F, Tang B. 2021. Mn-incorporated ferrihydrite for Cr(VI) immobilization: Adsorption behavior and the fate of Cr(VI) during aging. J Hazard Mater 417:126073. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dong FX, Yan L, Zhou XH, Huang ST, Liang JY, Zhang WX, Guo ZW, Guo PR, Qian W, Kong LJ, Chu W, Diao ZH. 2021. Simultaneous adsorption of Cr(VI) and phenol by biochar-based iron oxide composites in water: Performance, kinetics and mechanism. J Hazard Mater 416:125930. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Mu C, Zhong L, Xue J, Zhou Y, Han X. 2019. Recycling of Cr (VI) from weak alkaline aqueous media using a chitosan/triethanolamine/Cu (II) composite adsorbent. Carbohydr Polym 205:151–158. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hashimoto K, Kubota N, Marushima T, Ohno M, Nakai S, Motoshige H, Nishijima W. 2021. A quantitative analysis method to determine the amount of cellulose fibre in waste sludge. Environ Technol 42:1225–1235. 10.1080/09593330.2019.1662097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Song Y, Zhang Y, He M, Liu H, Hu C, Yang L, Yu P. 2020. Enhancing the production of poly-gamma-glutamate in Bacillus subtilis ZJS18 by the heat- and osmotic shock and its mechanism. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 50:1023–1030. 10.1080/10826068.2020.1780610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wiefel L, Steinbuchel A. 2014. Solubility behavior of cyanophycin depending on lysine content. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:1091–1096. 10.1128/AEM.03159-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lu Z, Ye J, Chen Z, Xiao L, Lei L, Han BP, Paerl HW. 2022. Cyanophycin accumulated under nitrogen-fluctuating and high-nitrogen conditions facilitates the persistent dominance and blooms of Raphidiopsis raciborskii in tropical waters. Water Res 214:118215. 10.1016/j.watres.2022.118215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Arcos-Hernandez MV, Pratt S, Laycock B, Johansson P, Werker A, Lant PA. 2013. Waste activated sludge as biomass for production of commercial-grade polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA). Waste Biomass Valor 4:117–127. 10.1007/s12649-012-9165-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen H, Gao Y, El-Naggar A, Niazi NK, Sun C, Shaheen SM, Hou D, Yang X, Tang Z, Liu Z, Hou H, Chen W, Rinklebe J, Pohořelý M, Wang H. 2022. Enhanced sorption of trivalent antimony by chitosan-loaded biochar in aqueous solutions: characterization, performance and mechanisms. J Hazard Mater 425:127971. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.127971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Text S1, Tables S1 and S2, and Fig. S1 to S5. Download aem.00742-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 1.1 MB (1.1MB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

The raw DNA sequences data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (accession no. CRA003823). The raw RNA sequences data were deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (accession no. CRA007158).