Abstract

Although iron (Fe) is an essential element for almost all living organisms, little is known regarding its acquisition from the insoluble Fe(III) (hydr)oxides in aerobic environments. In this study a strict aerobe, Pseudomonas mendocina, was grown in batch culture with hematite, goethite, or ferrihydrite as a source of Fe. P. mendocina obtained Fe from these minerals in the following order: goethite > hematite > ferrihydrite. Furthermore, Fe release from each of the minerals appears to have occurred in excess, as evidenced by the growth of P. mendocina in the medium above that of the insoluble Fe(III) (hydr)oxide aggregates, and this release was independent of the mineral's surface area. These results demonstrate that an aerobic microorganism was able to obtain Fe for growth from several insoluble Fe minerals and did so with various growth rates.

Used in all heme enzymes (proteins with an Fe cofactor), including cytochromes and hydroperoxidases, a constituent of ribonucleotide reductase and essential for the activity of nitrogenases, Fe is required by all microorganisms except those lactobacilli lacking heme and using a cobalt type of ribonucleotide reductase (1, 3). Fe's biological importance is a result of its electronic structure, which is capable of reversible changes in oxidation state over a wide range of oxidation-reduction potentials: 300 mV in a-type cytochromes to −490 mV in some Fe-sulfur proteins (7, 8, 17, 28). Owing to this redox versatility, Fe occupies a vital role in biological systems (31). However, Fe is very insoluble at circumneutral pH and in oxic environments. Although abundant at the Earth's surface, the most common forms of Fe, the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides (which include oxides, oxyhydroxides, and hydrated oxides) have solubility products ranging from 10−39 to 10−44, limiting the Fe3+ aqueous equilibrium concentration to ca. 10−17 M (20) in the absence of complexing ligands.

Most microorganisms require micromolar concentrations of Fe to support growth (18); as a consequence, Fe deprivation of many species will occur when the culture medium contains <0.1 μM available Fe. Given this constraint, microorganisms are faced with overcoming an approximately 10 orders of magnitude discrepancy between the available Fe (≈10−17 M) and their metabolic requirement (≈10−7 M) in aerobic environments. As emphasized by Schwertmann (23), the availability of Fe in aerobic soils must be governed by mineral dissolution rates.

For more than 50 years microbiologists have been aware of extracellular ligands, most notably siderophores, which are believed to be the primary means by which microorganisms acquire Fe (17). In fact, it has been assumed that because of the high formation constants of the siderophore-Fe(III) complexes (as high as 1052) Fe(III) (hydr)oxides would undergo spontaneous dissolution in the presence of a siderophore ligand. However, with the exception of a few studies (e.g., references 9, 12, and 30), there is little quantitative discussion in the literature regarding siderophore-mediated dissolution of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides and virtually no discussion of microbial acquisition of Fe from these solid phases in aerobic environments. To better understand the acquisition of Fe, we investigated the removal of Fe from three Fe(III) (hydr)oxides (geothite, hematite, and ferrihydrite) by a strict aerobe. We chose these minerals because they are found commonly in soils and represent major sources of Fe in natural environments. We chose an aerobic microorganism because, in contrast to facultative anaerobic environments, wherein dissimilatory iron-reducing bacteria (DIRB) are often abundant, very little is known about microbial interactions with Fe(III) (hydr)oxides in oxic environments, even though such environments are of widespread abundance and importance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fe(III) (hydr)oxides.

The minerals used in these experiments were synthesized according to methods described by Schwertmann and Cornell (24). BET (Brunauer, Emmett, and Teller) surface areas (i.e., surface areas determined from gas adsorption) were measured with an ASAP-2000 volumetric sorption analyzer from Micrometritics, Inc. (Norcross, Ga.) using N2 adsorption at −195.5°C (4). The resulting specific surface areas were designated As. Method 4 of Schwertmann and Cornell (24), i.e., “Preparation by Transformation of Ferrihydrite,” was used for the hematite (α-Fe2O3) synthesis and yielded two batches consisting of small, roughly hexagonal platelets, with As values of 15 and 32 m2 g−1. Goethite (α-FeOOH) was prepared from the Fe(III) system described in section 5.2.1 of that study (24). Different batches produced needle-like crystals ranging in length from 0.5 to 1 μm for greater-As (37 m2 g−1) to 1 to 3 μm for lower As (27 m2 g−1) size particles. Amorphous ferrihydrite was prepared by precipitation with alkali, as described in section 8.3 (24). This method yielded particles < 20 nm in diameter with an As = 284 m2 g−1. Particle size and shape estimates were confirmed by atomic force microscopy (AFM) performed at Kent State University using a Multi Mode NanoScope III AFM (Digital Instruments, Inc., Santa Barbara, Calif.).

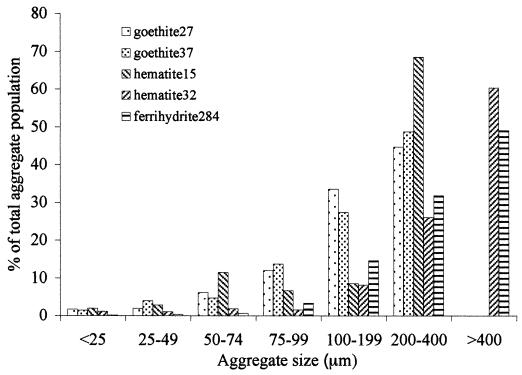

The BET method measured all surface area accessible to gas adsorption. Each of these minerals, however, formed aggregates during preparation. Because of this aggregation, not all of the BET surface area may have been available to the bacterial cells, and exterior aggregate surface area may have been a better indication of the proportion of total surface area which was accessible to microorganisms for attachment (i.e., the “effective” surface area, which we designate Aeff). Therefore, we estimated Aeff for each Fe(III) (hydr)oxide by using a phase-contrast microscope, in the absence of bacteria in the succinate medium. This size distribution is presented in Fig. 1. Aeff values for all the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides were found to differ substantially from the BET As values (Table 1). In order to determine Aeff, aggregates were assumed to be spherical for the sake of approximate calculations. However, this assumption necessarily neglects surface irregularities. Furthermore, due to limits on resolution of optical microscopy this method may have undercounted small aggregates and single particles, both of which have high specific surface areas. Hence, the Aeff values listed in Table 1 are likely to be minimum estimates.

FIG. 1.

Aggregate size distribution of Fe(III) (hydr)oxide aggregates.

TABLE 1.

Sample surface areas of synthetic Fe(III) (hydr)oxides

| Sample | Mean surface area (m2 g−1)

|

|

|---|---|---|

| BET (As) ± SD | Effective (Aeff) | |

| Hematite 32 | 32.2 ± 0.8 | 11.9 |

| Hematite 15 | 15.4 ± 0.04 | 11.5 |

| Goethite 37 | 37.2 ± 0.5 | 13.4 |

| Goethite 27 | 26.8 ± 0.2 | 13.9 |

| Ferrihydrite | 284 ± 4.0 | 13.7 |

Medium, growth conditions, and microorganism.

Fe deficient medium (FeDM) was prepared by adding to 1.0 liter of distilled, deionized water the following analytical-grade ingredients (Fluka Chemie, Buchs, Switzerland): 0.5 g of K2HPO4, 1.0 g of NH4Cl, 0.2 g of MgSO4 · 7H2O, 0.05 g of CaCl2, 5.0 g of succinic acid disodium salt anhydrous (C4H4Na2O4), and 0.125 ml of trace elements (0.005 g of MnSO4 · H2O, 0.0065 g of CoSO4 · 7H2O, 0.0023 g of CuSO4, 0.0033 g of ZnSO4, and 0.0024 g of MoO3 per 100 ml of distilled, deionized water). The pH of the medium was approximately 7.2. No attempt was made to deferrate the medium as suggested by Schwyn and Neilands (25) because it has been our experience that such attempts lead to variations in Fe concentrations due to Fe contamination within the 8-hydroxyquinoline (the agent used to deferrate growth medium) or chloroform (used to remove 8-hydroxyquinoline from the growth medium) or both. Rather, we used the analytical-grade ingredients listed above, acid-washed polycarbonate glassware, and ultrapure distilled and/or deionized water (18 MΩ cm−1). Most importantly, we compared growth on each of the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides to that of a no-added-Fe control. If substantial growth occurred in the control flasks (e.g., >0.6 absorbance units), the entire experiment was terminated and then restarted.

Polycarbonate Erlenmeyer flasks (250 ml) containing 30 ml of FeDM were used for all subsequent experiments. To these flasks were added various Fe sources: FeEDTA, goethite, hematite, ferrihydrite, or no-added-Fe control. For the FeEDTA growth studies, FeEDTA was added to yield 0, 0.048, 0.24, 1.2, 6.0, or 30 μM concentrations of Fe. For the Fe acquisition experiments, minerals were added so that the Aeff was 29 m2 liter−1 or the minerals were added in various concentrations (goethite, 0.0, 0.06, 0.22, 1.2, 5.8, or 29 m2 liter−1; hematite, 0.0, 0.04, 0.19, 0.98, 4.8, or 24 m2 liter−1; ferrihydrite, 0.0, 0.06, 0.23, 1.1, 5.7, or 28 m2 liter−1). We determined in previous experiments that P. mendocina could acquire Fe as easily from FeEDTA as it could from either FeNTA (NTA = nitrilotriacetic acid) or iron citrate and that neither EDTA nor NTA served as a carbon or an electron donor (15). Inoculated controls (no-added-Fe) contained neither minerals nor FeEDTA. The flasks were then sterilized by autoclaving.

The bacterium used for this study was isolated as part of the Yucca Mountain Project (the proposed site of the Nation's high-level nuclear repository) from sediment in a surface holding pond of a drilling operation at the Nevada Test Site. It was then identified as P. mendocina based on total rRNA sequence analysis at the 0.78% confidence level (MIDI, Inc.). Also, this organism tested positive for catalase, oxidase, and nitrate reduction (assimilatory) but negative for fermentation and dissimilatory nitrate, Fe, and sulfate reduction. Therefore, this organism is an obligate aerobe, one not capable of using nitrate or Fe as a terminal electron acceptor, and Fe acquisition is for metabolic needs only.

Each flask was inoculated with 285 μl of early-log-growth cells, at a 0.2 absorbance at 600 nm. The flasks were incubated in the absence of light [to minimize photo-induced Fe(III) reduction] at 22°C, while agitated at 50 rpm. The cell concentration was determined by absorbance (600 nm) and was related to cell numbers by separate comparisons of absorbance to CFU. We chose absorbance of the broth to determine cell numbers because it assessed the entire microbial population with the flasks. For example, total protein analysis (14) revealed no significant difference (t- test) between the number of microorganisms growing in the broth and the total population (microorganisms in the broth plus those attached to particles). Thus, absorbance of the broth accounted for both the free-swimming and attached cells, making it unnecessary to make separate measurements. Furthermore, the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides did not interfere with the absorbance readings because they agglomerated, settled to the bottom of the flasks, and remained there during the course of the experiments (11). Absorbance readings were taken twice daily for 4 days.

Fe concentrations.

After maximum microbial growth had occurred, the concentration of Fe in the FeDM containing either goethite, hematite, or ferrihydrite as an Fe source was determined by using three different methods: (i) from the cell numbers (absorbance), (ii) by spectrophotometric analysis, and (iii) by graphite furnace atomic absorption spectroscopy (GFAAS). From the number of cells (absorbance at 600 nm) present in the liquid medium it was possible to deduce the amount of Fe in the growth medium (i.e., the amount of Fe removed from the mineral surface) because under our experimental conditions cell growth was strictly controlled by, and thus could be used to determine, Fe concentration (10, 20). By comparing the absorbance of cells grown in FeDM with either the absorbance of cells grown in FeEDTA (Fig. 2) or Fe(III) (hydr)oxides (Fig. 3 and 4), one could determine the amount of Fe removed from the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides by the microorganisms. Second, Fe was determined spectrophotometrically by the reduction of Fe with aspartic acid, followed by complexation with bathophenanthroline and measuring the absorbance at 562 nm. Finally, Fe was measured using graphite furnace on a Perkin-Elmer atomic absorption spectrometer equipped with Zeeman background correction. The instrument was calibrated from 5 to 100 mg of Fe liter−1 by diluting a 1,000-mg liter−1 AA/ICP Calibration Standard (Aldrich). The pH of the Fe standards were lowered to pH ∼2 by using ultrapure HCl. Samples of >100 mg of Fe liter−1 were diluted 1:10 with Milli-Q water, and the pH was readjusted to ca. 2. The precision of analysis, as measured by relative standard deviation, was <5% for all concentrations above 10 mg liter−1.

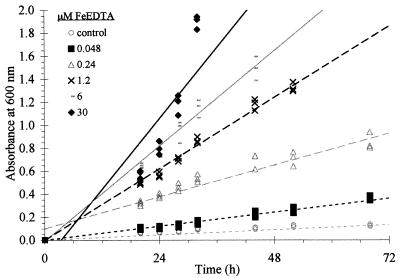

FIG. 2.

Microbial growth in response to various concentrations of FeEDTA: 30 μM, y = 0.051, x − 0.176, R2 = 0.81; 6.0 μM, y = 0.035x − 0.009, R2 = 0.98; 1.2 μM; y = 0.026x − 0; R2 = 0.99; 0.24 μM, y = 0.012x + 0.100, R2 = 0.93; 0.05 μM, y = 0.005x − 0, R2 = 0.99; and control, y = 0.002x − 0, R2 = 0.99.

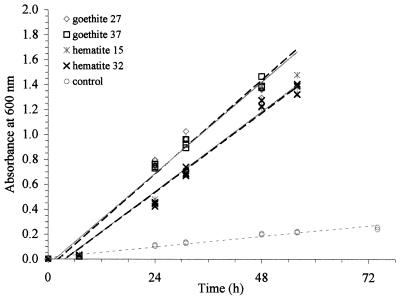

FIG. 3.

Microbial growth on two different hematites and two different goethites (Ca. 29 m2 liter−1 Aeff each) and a no-Fe-added control: goethite 27, y = 0.031x − 0.047, R2 = 0.97; goethite 37, y = 0.031x − 0.071, R2 = 0.98; hematite 15, y = 0.027x − 0.100, R2 = 0.98; hematite 32, y = 0.027x − 0.100, R2 = 0.98; and control, y = 0.004x − 0.011, R2 = 0.97.

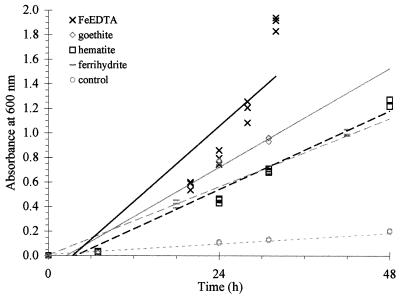

FIG. 4.

Microbial growth on different sources of Fe (30 μM FeEDTA; minerals approximately 29 m2 1−1, Aeff) and a no-Fe-added control: FeEDTA, y = 0.051x − 0.176, R2 = 0.81; goethite, y = 0.034x − 0.087, R2 = 0.97; hematite, y = 0.027x − 0.102, R2 = 0.97; ferrihydrite, y = 0.023x + 0.003, R2 = 0.99; and control, y = 0.004x + 0.008, R2 = 0.97.

Medium-promoted dissolution and nutrient sorption.

Two different control experiments were performed to assess (i) the effects of the FeDM and the autoclaving procedure on the dissolution of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides and (ii) the effects of the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides on the ingredients of FeDM. First, to determine if either the medium itself or the autoclave procedure was promoting Fe dissolution, sterile media (autoclave) containing each of the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides were set aside for 2 weeks, passed through 0.2-μm (pore-size) filters (to remove the minerals), inoculated with P. mendocina, and incubated as described above. Growth in this conditioned medium relative to the no-added-Fe control would indicate increased Fe concentrations in the medium due to dissolution promoted by succinate or the autoclave process.

A second analysis was performed to determine whether the three Fe(III) (hydr)oxides sorbed ingredients of the FeDM differently. This was important to determine because such selective adsorption could affect growth on a particular Fe(III) (hydr)oxide different from another Fe(III) (hydr)oxide, making it difficult to compare the relative growth on each of the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. The media were conditioned as described above, the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides were removed by filtration (0.2 μm), and the supernatants were supplemented with FeEDTA (30 μm) and inoculated. Growth was compared to that of the control (unconditioned, FeDM plus 30 μM FeEDTA).

All experiments described in the Materials and Methods section were performed in triplicate.

RESULTS

Cell growth and Fe concentration.

As the concentration of FeEDTA decreased, so did growth rate (Fig. 2). This confirmed previous observations (10, 18) that within this particular experimental approach it was possible to control growth by controlling the concentration of Fe.

When the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides were the sources of Fe, we observed microbial growth in the medium (as well as on the surface of the mineral) that exceeded that of the no-added-Fe control (a very limited amount of growth did occur in the control medium, as seen in Fig. 4). Apparently, microorganisms attached to the Fe(III) (hydr)oxide agglomerates at the bottom of the flasks were removing enough Fe to support not only their growth but also the growth of nonattached cells in the medium above the minerals. In fact, all three methods of measuring Fe concentration in the medium determined that ample Fe was present in the FeDM to support microbial growth. The most conservative values came from estimates based on microbial growth (Table 2), in which estimated Fe concentrations ranged from 0.7 to 0.9 μM. GFAAS analysis yielded intermediate values. For example, hematite 15 and 32 both had 1 to 2 μM Fe, as opposed to geothite 27 and 37 FeDM, which contained 4 to 5 μM Fe. Finally, analysis by Fe(III) reduction to Fe(II), followed by complexation with bathophenanthroline, resulted in higher but more varied estimates of liberated Fe (2.6 versus 10.9 μM Fe were present in the FeDM for ferrihydrite and goethite 37, respectively). Together, these results demonstrate that P. mendocina removed Fe from the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides, resulting in increased Fe concentrations in the FeDM. As presented in Fig. 2, 1.0 μM Fe present in the FeDM is more than enough Fe to support the growth of this microorganism.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of results from different methods for determining Fe concentration (micromolar) in the medium

| Sample | Mean ± SD

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial growtha | GFAAS | Fe(III)-Fe(II)b | |

| Goethite 37 | 0.7 ± 0.03 | 5.1 ± 0.71 | 10.9 ± 1.9 |

| Goethite 27 | 0.7 ± 0.02 | 4.1 ± 0.51 | 10.0 ± 2.4 |

| Hematite 32 | 0.7 ± 0.02 | 2.0 ± 0.54 | 10.1 ± 2.0 |

| Hematite 15 | 0.7 ± 0.04 | 1.9 ± 0.35 | 8.4 ± 4.8 |

| Ferrihydrite | 0.85 ± 0.01 | NDo | 2.6 ± 0.6 |

Determined by comparison to growth on FeEDTA.

Reduction and complexation with bathophenanthroline.

ND, no data available.

When Fe was provided as FeEDTA, goethite, hematite, ferrihydrite, or no-added-Fe control, different rates of microbial growth were observed (Table 3 and Fig. 4). The two treatments whose 95% confidence bounds were the closest were ferrihydrite and hematite (the upper bound of ferrihydrite is 0.0246 and the lower bound for hematite is 0.0282; Table 3). The difference between the slopes for these two treatments is 0.007. The small sample standard deviation for the difference of these two slopes is 0.000859 (see, for example, the study by McClave and Dietrich [16]) and the P value for the t- test of the difference between the two slopes being zero is <0.0001 (using 17 degrees of freedom). Thus, there is strong evidence that the two treatments (hematite and ferrihydrite) were different. Furthermore, because the two closest rates differed significantly at the 0.0001 level, the rates of all the treatments would differ at a P value of this size or less, thereby providing strong evidence that all of the treatments differed significantly from one another. This analysis confirms that the order of growth on the various sources of Fe was as follows: FeEDTA > goethite > hematite > ferrihydrite > no-added-Fe control.

TABLE 3.

Statistical analysis of the rates of growth of P. mendocina on various sources of Fea

| Fe source | Slopeb | Slope SE | 95% minimum slope | 95% maximum slope | Degrees of freedom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.0035 | 0.0002 | 0.0031 | 0.0039 | 11 |

| Goethite | 0.0395 | 0.0015 | 0.0365 | 0.0425 | 7 |

| Hematite | 0.0300 | 0.0009 | 0.0282 | 0.0318 | 10 |

| Ferrihydrite | 0.0230 | 0.0008 | 0.0214 | 0.0246 | 7 |

| FeEDTA | 0.1086 | 0.0095 | 0.0896 | 0.1276 | 10 |

The Fe source slopes (rates), standard errors for the slopes, and the upper and lower 95% confidence bounds for the slopes are presented.

Growth rate(s) are represented as absorbance units h−1.

Surface area.

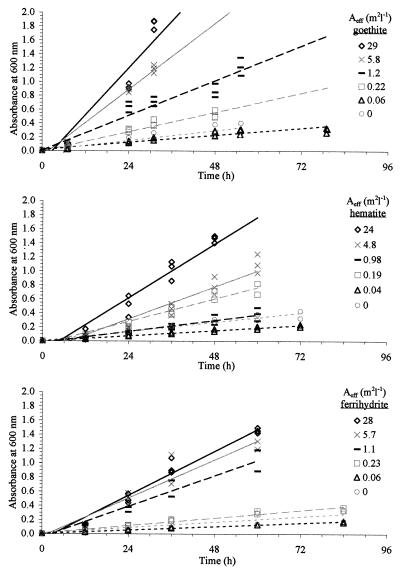

As can be seen in Fig. 5, increases in the amount of goethite, hematite, and ferrihydrite resulted in increased growth rates for this microorganism. Clearly, the microorganism responded to the increase in Fe in the form of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. While it appears that increased surface area resulted in increased growth, it does not appear that surface area alone controlled growth. Although different As values were used [the amount of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides added to the flasks was determined by Aeff], identical growth rates were obtained for two goethites (Fig. 3). Identical growth rates also were obtained for two hematites having different As values. These results suggest that Aeff and not As controlled the microbial growth on Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. Furthermore, the growth of P. mendocina was affected differently by the different Fe(III) (hydr)oxides with the same Aeff (Fig. 3 and 4). Surprisingly, growth rates were greater on the more ordered goethite than on the poorly ordered and higher-As ferrihydrite.

FIG. 5.

Microbial growth in response to various quantities of available surface area of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides.

Medium-promoted dissolution and nutrient sorption.

Growth greater than in the controls (FeDM) was not observed in the conditioned media [FeDM exposed to Fe(III) (hydr)oxides, filtered and then inoculated], demonstrating that neither the medium nor the autoclaving procedure were responsible for Fe dissolution.

Additionally, no difference in the growth of the bacterium was observed between that of the FeDM exposed to goethite, hematite or ferrihydrite [Fe(III) (hydr)oxides were then removed by filtration, and each filtrate was supplemented with FeEDTA] and that of the control (FeDM). This result confirms that none of the three Fe(III) (hydr)oxides selectively sorbed nutrients from the FeDM.

DISCUSSION

Dissolution of Fe.

Measurements of Fe by GFAAS, Fe(III) reduced to Fe(II) measured with bathophenanthroline, and estimates of Fe based on microbial growth all indicate that ample Fe was liberated into FeDM during microbial growth in the presence of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. The variability in these measurements may be because each measured different portions of the Fe held in the aqueous phase. Estimating Fe based on optical density reflects microbial response to a particular Fe concentration but does not reveal the total Fe concentration, only the amount used by the cell. GFAAS analysis measures the entire concentration (in solution, bound to the cell walls, and inside the cells). Measurement of Fe(III) reduction measures Fe(III) accessible to the reductant. In spite of their variability, together these measurements demonstrate that the P. mendocina removed Fe from the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. Furthermore, enough Fe (in a micromolar concentration) was liberated to support the luxuriant growth of both attached and free-swimming P. mendocina.

Solubility.

As stated above, P. mendocina was able to obtain metabolic Fe from Fe(III) (hydr)oxides in the following order: goethite > hematite > ferrihydrite. These results are in contrast to typical abiotic dissolution rates (27) and are in contrast to reports by a number of groups (see, for example, reference 26), particularly for studies of Fe(III) reduction by facultative anaerobes such as DIRB. Although DIRB studies are conducted under reducing conditions, such results are germane to understanding the relationship between solubility-crystalline order and dissolution. In one study, Phillips et al. (19) reported that microorganisms readily reduced poorly ordered Fe(III) oxide (e.g., ferrihydrite), extractable by oxalate, and did not reduce the more ordered Fe(III) forms such as goethite (FeOOH) and hematite (Fe2O3), which oxalate did not extract.

Simplistically, one might anticipate that the relative sequence of Fe acquisition would correlate to the relative solubility of the three Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. At circumneutral pH, ferrihydrite is the most soluble of the three, followed by hematite, which is slightly more soluble than goethite (5). However, P. mendocina obtained Fe from these minerals in contrast to their relative solubilities. Thus, solubility cannot be used to explain our results, and it appears that microbial removal of Fe from these minerals did not follow conventional wisdom because neither solubility nor crystalline order controlled acquisition.

Surface area.

While our results show clearly that increases in mineral concentration for each of the three Fe(III) (hydr)oxides resulted in increased growth rate (Fig. 5), our analysis also revealed that the BET surface area (As) did not control Fe acquisition (Fig. 3). The As values were different for the different goethites as well as for the different hematites, yet the growth curves for the two goethites were identical, as were the growth curves for the two hematites. Differences in As for either Fe(III) (hydr)oxide had no effect on microbial acquisition of Fe from either goethite or hematite. Thus, we believe that factors other than As controlled Fe acquisition in our experiments. This observation is consistent with reports in the literature (e.g., reference 2 and 20). For example, Arnold et al. (2) suggested that the tendency of hematite and goethite to aggregate in neutral pH range makes standard measures (such as nitrogen adsorption, i.e., BET) of particulate surface area inappropriate. They suggest that “such measurements would overestimate the surface which is available for microbial contact.” These authors go on to caution that their observed rate in reductive dissolution is clearly dependent on hematite morphology and cannot be extended to minerals with a significantly different particle size distribution.

In a recent study, Roden and Zachara (20) reported that cell growth correlated with surface area. Although their preparation of Fe(III) (hydr)oxide (6) was different from ours (24), they did use transmission electron microscopy to determine the size range of individual particles and to assess the degree of particle aggregation (similar to our efforts to determine Aeff). Thus, these authors were not correlating dissolution to BET surface area but rather to an approximated surface area, in agreement to what we report here.

Al substitution.

We have reported that correlation of the dissolution of goethite to surface area can be misleading (15). In that study, normalizing for Aeff revealed that dissolution was not a function of surface area but rather correlated positively with increased Al substitution. This result was counterintuitive because the stability of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides has been shown to increase with increasing Al substitution (29, 32); thus, the bacterium should have grown more easily on the less ordered (i.e., less Al substituted) goethite. It may be that particle (and aggregate) morphology was more important than surface area or thermodynamic stability; goethite needles become shorter and less multidomainic as their Al content increases (15, 24). These results, when combined with the discussion of surface area (above) strongly suggest that neither thermodynamic stability nor BET surface area control microbially mediated Fe(III) (hydr)oxide dissolution.

Hydroxyl coordination.

Recently, Cornell and Schwertmann (5) discussed the occurrence and importance of singly, doubly, triply, and geminal coordinated hydroxyl groups, which are in effect the functional groups of Fe(III) (hydr)oxides, i.e., the chemically reactive entities at the mineral surface in an aqueous environment. Adsorption reactions are considered to involve only singly coordinated groups; the doubly and triply coordinated groups appear to be nonreactive (13, 21). In general, singly coordinated hydroxyl groups are believed to be more common on the faces of goethite than on hematite (5). Unfortunately, little is known about the relative distributions of hydroxyl groups on ferrihydrite (with respect to goethite and hematite) because the bulk structure of ferrihydrite is poorly understood and ferrihydrite surface structure is likely so dynamic that it may transform during titration analysis. Although the relative occurrence of surface reactive entities (goethite > hematite) is consistent with our observed Fe acquisition from Fe(III) (hydr)oxides, uncertainties with respect to ferrihydrite make this particular comparison premature at this time. Certainly, we will be vigilant with respect to developments concerning hydroxyl group distribution on the surface of ferrihydrite, since this explanation appears to hold promise.

Transients.

Perhaps the most intriguing influence comes from Samson and Eggleston (see reference 22 and references therein), who reported that the effect of transients are responsible for initially rapid Fe dissolution rates. Transients are nonstructural Fe sorbed to the mineral surface that are difficult to quantify and are ephemeral, in that once removed by cleaning they may reform. It is possible that some fraction of the Fe acquired by P. mendocina from Fe(III) (hydr)oxides was nonstructural and transient. Thus, the dissolution reported here may be sensitive to both differences in mineral surface characteristics (hydroxyl groups) and the presence surface transients. Unfortunately, it is nearly impossible to determine the relative contribution of transients to the total budget of acquired Fe. Nevertheless, significant and repeatable differences were observed in the acquisition of Fe from the different Fe treatments, suggesting that from the microorganism's point of view, significant differences in the available Fe at or on the surfaces of those treatments did exist. If transient Fe is being utilized by the cells, its use was influenced by the Fe(III) (hydr)oxide on which it is found. As with developments in the hydroxyl coordination literature, we will anxiously await further developments in the studies of transient Fe.

In conclusion, our results demonstrate that P. mendocina obtained Fe for growth with increasing difficulty from goethite, followed by hematite, and finally ferrihydrite, independent of the BET surface area. Furthermore, several different lines of evidence suggest that Fe acquisition activity occurred at rates high enough to support the growth of not only those microorganisms attached to the mineral surface but also those growing unattached. As stated earlier, at circumneutral pH and oxic conditions, the solubility of Fe is approximately 10−17 M. In effect, this microorganism was increasing the solubility of Fe by 10 to 11 orders of magnitude, for each of the Fe(III) (hydr)oxides examined. We provide here the first description of significantly different growth rates of a strict aerobe on three environmentally relevant, insoluble Fe(III) (hydr)oxides. Hopefully, this work will serve to stimulate further research into the Fe metabolism and dissolution process by microorganisms in Fe-deficient environments.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the Department of Energy/Basic Energy Sciences.

We thank Mietek Jaroniec in the Department of Chemistry at Kent State University, Kent, Ohio, for performing BET surface area measurements and Garrison Sposito, University of California at Berkeley, for careful editing of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Archibald F. Micrococcus lysodeikticus, an organism not requiring iron. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1983;19:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold R G, DiChristina T J, Hoffmann M R. Reductive dissolution of Fe(III) oxides by Pseudomonas sp. 200. Biotech Bioeng. 1988;32:1081. doi: 10.1002/bit.260320902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briat J-F. Iron assimilation and storage in prokaryotes. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:2475–2483. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-12-2475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brunauer S, Emmett P H, Teller E. Adsorption of gases in multimolecular layers. J Phys Chem. 1938;60:309–319. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cornell R M, Schwertmann U. The iron oxides. 1996. pp. 181–184. and 207–213. VCH, Weinheim, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodman B A, Lewis D G. Mossbauer-spectra of aluminous goethites (FeOOH) J Soil Sci. 1981;32:351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerinot M L. Microbial iron transport. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1994;48:743–772. doi: 10.1146/annurev.mi.48.100194.003523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guerinot M L, Yi Y. Iron: nutritious, noxious and not readily available. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:815–820. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.3.815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hersman L, Lloyd T, Sposito G. Siderophore-promoted dissolution of hematite. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1995;59:3327–3330. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersman L, Maurice P, Sposito G. Iron acquisition from hydrous Fe(III) oxides by an aerobic Pseudomonas sp. Chem Geol. 1996;132:25–31. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hersman L E, Huang A, Maurice P A, Forsythe J H. Siderophore and reductant production by Pseudomonas mendocina in response to Fe deprivation. Geomicrobiol J. 2001;17:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holmen B A, Casey W H. Hydroxymate ligands, surface chemistry, and the mechanism of ligand-promoted dissolution of goethite [α-FeOOH(s)] Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1996;60:4403–4416. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lewis D G, Farmer V C. Infrared absorption of surface hydroxyl groups and lattice vibrations in lepidocrocite (γ-FeOOH) and boehmite (γ-Al-OOH) Clay Min. 1986;21:93–100. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maurice P A, Lee Y-J, Hersman L E. Dissolution of Al-substituted goethites by an aerobic Pseudomonas mendocina var. bacteria. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 2000;64:1363–1374. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McClave J T, Dietrich F H. A first course in statistics. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif: Dellen Publishing Company; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neilands J B. Microbial iron compounds. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:715–732. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.003435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Neilands J B, Nakamura K. Detection, determination, isolation, characterization, and regulation of microbial iron chelates. In: Winkelmann G, editor. Handbook of microbial iron chelates. Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press, Inc.; 1991. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Phillips E J P, Lovley D R, Roden E E. Composition of non-microbially reducible Fe(III) in aquatic sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:2727–2729. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.8.2727-2729.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Roden E E, Zachara J M. Microbial reduction of crystalline iron(III) oxides: influence of oxide surface area on potential for cell growth. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:1618–1628. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russel J D, Parfitt R L, Fraser A R, Farmer V C. Surface structure of gibbsite, goethite and phosphated goethite. Nature. 1974;248:220–221. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Samson S D, Eggleston C M. Active sites and the non-steady-state dissolution of hematite. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:2871–2875. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schwertmann U. Solubility and dissolution of iron oxides. Plant Soil. 1991;129:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwertmann U, Cornell R M. Iron oxides in the laboratory. New York, N.Y: VCH; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schwyn B, Neilands J B. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal Biochem. 1987;160:47–56. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90612-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seaman J C, Alexander D B, Loeppert R H, Zuberer D A. The availability of iron from various solid-phase iron sources to a siderophore-producing Pseudomonas strain. J Plant Nutr. 1992;15:2221–2233. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stumm W, Furrer G, Wieland E, Zinder B. The effects of complex-the dissolution of oxides and aluminosilicates. In: Drever J I, editor. The chemistry of weathering D. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Reidel Publishing Co.; 1985. pp. 55–74. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stumm W, Morgan J J. Aquatic chemistry. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. pp. 489–491. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trolard F, Tardy Y. The stabilities of gibbsite, boehmite, aluminous goethites and aluminous hematites in bauxites, ferricretes and laterites as a function of water activity, temperature, and particle size. Geochim Cosmochim Acta. 1987;51:945–957. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watteau F, Berthelin J. Microbial dissolution of iron and aluminum from soil minerals: efficiency and specificity of hydroxamate siderophores compared to aliphatic acids. Eur J Soil Biol. 1994;30:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams R J P, Frausto J J R. The natural selection of the chemical elements. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press; 1996. pp. 487–489. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yapp C J. Effects of AlOOH-FeOOH solid solution on goethite-hematite equilibrium. Clays Clay Min. 1983;31:239–240. [Google Scholar]