Abstract

Advanced liver disease (AdvLD) is a high-risk common condition with a progressive, highly morbid, and often fatal course. Despite effective treatments, there are substantial shortfalls in access to and use of evidence-based supportive and palliative care for AdvLD. Although patient-centered, chronic illness models that integrate early supportive and palliative care with curative treatments hold promise, there are several knowledge gaps that hinder development of an integrated model for AdvLD. We review these evidence gaps. We also describe a conceptual framework for a patient-centered approach that explicates key elements needed to improve integrated care. An integrated model of AdvLD would allow clinicians, patients, and caregivers to work collaboratively to identify treatments and other healthcare that best align with patients’ priorities.

Advanced liver disease (AdvLD), defined as cirrhosis of any cause with 1 or more liver-related complications, is a high-risk common condition with a progressive, highly morbid, and often fatal course. The prevalence of AdvLD has doubled from 2001 to 2013, and is expected to increase further.1,2 AdvLD predisposes to a range of complications including ascites, hepatic encephalopathy, variceal bleeding, and hepatocellular cancer (HCC). Complications occur at an annual rate of approximately 10%.3 Half of patients die within 2 years of developing complications; however mortality ranges from 20% to 70%–80% in different studies—highlighting the variability in prognosis.3 AdvLD is also resource intensive; many complications require hospital admission4 and nearly 70% experience readmission at a cost >$20,000 per admission.5 The burden of AdvLD is amplified by its dramatic impact on patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQOL) resulting from multiple physical, psychological, and social stressors.6,7

Antiviral treatments and liver transplantation hold promise for arresting progress of liver disease and even have curative potential.8,9 For patients with AdvLD, liver transplantation is a valid option, but is received by only a small subset of patients.10,11 All patients, even those who are considered for transplant, can benefit from supportive care therapies and chronic care, which can reduce morbidity and mortality associated with AdvLD.12,13 Palliative care referrals may reduce procedure burden and cost of terminal hospitalizations.14 Surveillance of cirrhosis increases detection of early stage HCC and prolongs survival among selected patients.15 Evidence based therapies can reduce the risk of variceal bleeding, complications of encephalopathy, and frequent hospitalizations.16,17 Psychological care can encourage alcohol abstinence and reduce complications.18

Despite effective treatments, there are substantial shortfalls in access to and use of evidence-based supportive and palliative care for AdvLD. Fewer than a third of AdvLD patients receive all recommended supportive and palliative care (ie, preventive or symptomatic treatments of AdvLD complications, managing coexisting pain or depression, and advance directives).19,20 Other studies show significant underuse of end-of-life comfort-oriented care (comfort care and hospice decisions). For example, among 102 consecutive patients with severe AdvLD (median survival 52 days), only 11% had received referral to palliative care.21 Unfortunately, curative, supportive and palliative, and end-of-life comfort care approaches often conflict rather than reinforce one another in routine practice. A study of almost 500 AdvLD patients found that patients considered for transplant received lower-quality end-of-life care than did patients not considered for transplantation, with major deficits in communication (including advance directives and hospice decisions) and symptom management.22

Patient-centered, chronic illness models that integrate early supportive and palliative care with life-prolonging treatments are becoming increasingly common in cancer. Palliative care is an approach that focuses on quality of life of patients and their families through the prevention, assessment and relief of suffering, pain, and other problems using symptom management, psychosocial care, communication, complex decision making, and transitions of care. Supportive care is a term now commonly used to encourage earlier referrals due to the misperception that palliative care is relevant only at the end of life.23,24 In a study by Temel et al,25 early supportive and palliative care (integrated with oncology care) of patients with advanced lung cancer led to prolonged survival with improvements in HRQOL and mood compared with patients receiving standard care.26 These beneficial effects may have stemmed in part from improvements in patients’ coping strategies and understanding of their prognosis, which influenced their decisions to opt for palliative rather than curative care.25 Qualitative data from this study suggest that early palliative care facilitated broader communication between patients and clinicians.27 These and other emerging data28,29 provide compelling evidence for integrating supportive and palliative with curative care earlier in the course of a serious illness, in which morbidity can be attenuated, mortality forestalled, and HRQOL preserved, even at late stages of disease.30 Models of AdvLD care that integrate early supportive and palliative care with curative care can potentially improve patient outcomes. As of yet, there are only a few similar efforts in AdvLD. None rely on patients’ preferences to align treatments to their health priorities across the full course of a chronic illness.

We describe a conceptual framework for an integrated patient-centered approach to AdvLD care derived from a review of literature. This framework structures a model of AdvLD care delivery based on patients’ priorities related to their clinical management,31 and supports a shared mental model of the importance of early integration of palliative care principles in the care of patients with AdvLD.32 Patients’ health priorities include their desired curative as well as supportive and palliative outcomes (ie, health outcome goals) and what patients will or will not do to achieve those goals (ie, care preferences).33 Moreover, patients’ priorities and preferences are grounded in their illness experiences as they contend with advancing disease. We believe that an integrated model of AdvLD would allow clinicians, patients, and caregivers to work collaboratively to identify treatments and other health care that best align with patients’ priorities and may be more effective in improving patient-centered health outcomes than would one-size-fits-all approaches. We conclude with recommendation on how to develop this integrated model of AdvLD care.

Management of AdvLD: Need for Collaborative Treatment Planning Guided by Patient Priorities

Contemporary thinking on how best to manage chronic, serious illness is often informed by the chronic care model,34 which guides our own model, particularly in identifying shortcomings in patient-centered approaches in AdvLD. The chronic care model, tailored to AdvLD, is presented in Figure 1. A patient-centered approach to any chronic illness includes the following essential elements: informed and involved patients and caregivers, receptive and responsive clinicians, and a health care environment that supports the collaborative efforts of patients, caregivers, and their clinicians. A central tenet of patient-centered chronic illness care is the availability of reliable information about prognosis and the availability of suitable, evidence-based therapies. Indeed, providing patients and their families with information about a condition, its prognosis, and available therapies is an integral component of the Institute of Medicine’s blueprint for patient-centered care in cancer. The bold arrows in Figure 1 show the relationships between these components. Starting on the left, prognostic and therapeutic data contribute to informed patients and caregivers by clarifying the likely course of disease and the available options. Better understanding of prognosis and his or her likelihood of receiving transplant (curative care) nudges patients and family members from precontemplation toward contemplation and preparation in regards to their expectations about the future, likelihood for complications, and self-management needed for AdvLD care. By envisioning the 2 realities (their prognosis and chance of curative liver transplantation), patients are more prepared to prioritize their goals of care across the disease spectrum and frame their preferences for curative and supportive and palliative care.25 For example, patients who have a high probability of becoming a transplant recipient may choose aggressive treatments (transplant evaluation). Conversely, patients unlikely to receive a transplant or unable to be considered (eg, size of HCC) may favor supportive and palliative care to improve HRQOL. For clinicians, prognostic data informs conversations about the course of illness and provides a context for more personalized care recommendations with the overarching goal of promoting early integration of supportive, palliative care with curative care.

Figure 1.

Chronic care model applied to advance liver disease care. AdvLD, advanced liver disease

Combined, these 3 elements (prognostic and therapeutic information, informed patients and caregivers, and prepared clinicians) can foster collaborative treatment planning between clinicians, patients, and caregivers. We choose the term collaborative treatment planning, as opposed to shared decision making. Traditional shared decision making typically focuses on treatment preferences for a single event (ie, the treatment “decision”). In contrast, collaborative treatment planning focuses on aligning treatments to patient priorities across the full course of a chronic illness,35 and thus has the potential to successfully integrate (curative, supportive, and palliative end-of-life comfort) care in AdvLD. In this manner, patients and their caregivers may simultaneously opt for processes that meet a range of treatment outcomes earlier in their disease course (eg, enroll in transplant evaluation, participate in an alcohol abstinence program, receive training for ascites self-management, and engage in preparing an advance directive). The goals may shift more toward palliative and then end-of-life comfort care as the disease becomes potentially life threatening, especially for patients for whom liver transplantation is no longer an option (for any reason). However, this process is dynamic, as patients can move in both directions on the integrated AdvLD continuum as a result of shifts in AdvLD status and prognosis.

Structured tools (including print-, video-, or web-based media) can empower patients and caregivers for collaborative treatment planning with clinicians that fosters this early and ongoing integration. Two recent systematic reviews found that these tools can improve knowledge and treatment choices, including palliative care and goals of care communication in seriously ill patients.36,37 However, most tools are designed for serious illnesses in which the trajectory is clear (eg, advanced cancer and dementia), and many only support one-time decisions. These prior systematic reviews called for tools and programs that facilitate ongoing treatment planning among clinicians and patients/caregivers facing serious but uncertain trajectories (eg, AdvLD), especially as illness progresses and circumstances evolve.36,37 Unfortunately, critical knowledge gaps affect all 3 key elements described previously, rendering it difficult to design tools and platforms (eg, decision support, communication tools) for patients and their caregivers that incorporate early supportive and palliative care into management of AdvLD. We discuss these gaps subsequently.

Knowledge Gaps in Understanding of Illness Prognosis and Therapeutic Options in AdvLD

The 2 commonly used prognostic models for AdvLD are Child-Turcotte-Pugh and Model for End-stage Liver Disease scores. These scores are readily available for use in clinical care. Both rely on clinical and laboratory data and have modest discriminative ability (C-statistic <0.7) for mortality.38 However, both omit variables known to predict adverse outcomes in AdvLD. Older age,4,39 male sex,4,39,40 physical and mental health comorbidities, and sarcopenia and frailty41,42 predict suboptimal outcomes in AdvLD, but are not included in the available prognostic models.40,43 Alcohol use40 increases risk, whereas eradication of hepatitis C virus may decrease risk.8 Data also underscore social determinants of health (eg, marital status and homelessness)44 and use of medical services (eg, emergency visits) in predicting hospitalization or mortality.45,46 The latter are commonly used in generic models, including the Care Assessment Need score.45 Expanding current models with these factors may increase their predictive ability for mortality. Further, although mortality is an important outcome, risk of hospitalization, and development of new liver complications are additional outcomes that matter to patients and clinicians, but not modeled in existing prognostic scores. The lack of these prognostic data related to the clinical outcomes that matter most to patients and caregivers hinders treatment planning.

Clinicians, patients, and caregivers are often unclear or unaware of the range of therapeutic options available to them across the integrated care spectrum. Bringing dietitians, physical therapists, mental health providers, pain specialists and transplant teams into routine collaborative care conversations with a shared mental model of integrative care to achieve patients’ priorities is critical for providing more patient-centered AdvLD care.32,33 Decision support tools that better inform patients and clinicians of the range of evidence-based therapies are needed at the point of care to promote collaborative care conversations across the range of integrated AdvLD care.

Knowledge Gaps in Understanding Patients’ Perceptions of their Prognosis, Priorities, and Experiences

Little is known about patients’ and caregivers’ understanding of AdvLD prognosis, disease trajectory, and likelihood of receiving transplantation. Many patients with other serious illnesses hold inaccurate perceptions of their prognoses25; patients with AdvLD may not be an exception. Additionally, it is unclear how (format and timing) patients and caregivers would prefer to receive prognostic and therapeutic information in clinical encounters.

There are also very limited data on patient-defined outcome goals of AdvLD care (ie, health and life outcomes that patients desire from their health care and are aligned with what matters most to them—patients’ values).33 Few available studies suggest that while patients value curative care, they also endorse supportive care outcomes as important goals, highlighting the need for earlier integration of supportive and palliative care.29 Studies in other areas of medicine underscore the importance of goal-oriented care,47 which relies on eliciting abilities and activities that patients value the most, then collaboratively reaching care decisions that prioritize (rather than compromise) those values. In a study of patients with colorectal, head and neck, gastric, or esophageal cancers,48 over half of the participants expressed values of balancing quality and length of life (62%) and self-engagement in care (69.9%). Other valued activities and abilities included connectedness and legacy (37%), function and self-sufficiency (18.5%), and life enjoyment (9%). These values were important to the participants and shaped their preferences and health care decisions. No research to date has comprehensively examined the health values of patients with AdvLD. Understanding patient and caregiver preferences for care consists of a clear articulation of what they are willing and not willing to do to achieve their outcome goals, what care they find helpful, and care they find burdensome and are not willing to do. A clear articulation of the health outcome goals that patients and caregivers desire across the disease spectrum is needed to adequately frame the bounds of patient-centered AdvLD care.33

Last, patients’ illness-specific health care needs and their experiences with care likely shape how they access and engage in collaborative AdvLD care.49-54 We found one recent review of literature that included 13 qualitative studies conducted from 1990 to 2012 that describe AdvLD patients’ and caregivers’ experiences.49 We identified an additional 7 studies (Table 1) by updating the review through August 2016, and expanding the search criteria to include studies on AdvLD patients’ and caregivers’ needs and preferences Collectively, the data show that patients with AdvLD need physical, psychological, social, and educational support. Their illness experience is marked by debilitating fatigue and discomfort that impacts HRQOL and causes mental distress. Increasing complications are common stressors. Anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder are prevalent among patients with AdvLD, and most patients do not receive psychiatric care. Many patients reported a desire to maintain physical and social independence, and to self-manage the illness. However, there is a great deal of uncertainty about the cause, self-care responsibilities, course of the disease, and future care needs. Little is known about the role of patients’ social support networks in the management of AdvLD. Some patients avoid discussing prognosis or acknowledging the possibility of death; lack of communication about prognosis can leave patients uncertain, unprepared, and unable to cope. In general patients expect their clinicians to initiate discussions about end-of-life care, but literature suggests that providers may avoid or truncate these important conversations.29

Table 1:

Patient experience in advanced liver disease: qualitative studies (or studies containing a qualitative element) retrieved

| Authors | Year Published |

Study aims | Methodology | Study population | Disease cause represented |

Post- Transplant |

Key results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdi et al.52 | 2015 | Describe experiences of individuals with liver cirrhosis |

|

10 patient participants (7 men; 3 women); ages 39-54; Location: Iran | Cirrhosis | No |

|

| Day et al.65 | 2015 | Explore experiences of patients living with non-malignant ascites receiving inpatient paracentesis to manage their symptoms |

|

6 patients (3 referred for transplant evaluation) Location: United Kingdom | Cirrhosis with Ascites, without cancer | No |

|

| Etkind et al.50 | 2017 | Examine patient experiences of uncertainty in advanced illness and develop a typology of responses and preferences to inform practice |

|

30 total patients (12 women; 18 men); Heart failure (n=10), COPD1 (n=4), Renal disease (n=10), Cancer (n=5), Liver disease (n=1); Location: United Kingdom | Liver disease, heart failure, renal failure, cancer, and lung disease | No |

|

| Kendall et al.53 | 2015 | Explore how patients with different advanced conditions and their family and professional caregivers perceive their deteriorating health and the services they need |

|

828 interviews (156 patients; 114 family caregivers; 170 health professionals); Patient age 21-95; Location: Scotland | Multiple conditions ranging in illness trajectory and phase of illness across trajectories | No |

|

| Kimbell et al.51 | 2015 | Explore the experiences and support needs of people with advanced liver disease and those of their lay and professional careers |

|

37 participants (15 patients, 11 lay, and 11 professional careers); No age given; Location-United Kingdom | Advanced liver disease | No |

|

| Kunzler-Heule et al.66 | 2016 | Explore experiences of informal caregiving for a relative with liver cirrhosis and overt hepatic encephalopathy |

|

12 informal caregivers (4 male; 8 female); No age given; Location: Switzerland | Hepatic encephalopathy; liver cirrhosis | No |

|

| Saracino et al.54 | 2018 | Examine prevalence of psychiatric disorders and mental health service utilization among patients awaiting liver transplant |

|

120 patients (73 male; 47 female); Avg. age 56 (27-76). Location: United States (civilian) | Hepatitis C, alcoholic liver disease, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | No |

|

AdvLD: advanced liver disease; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; HRQOL, health-related quality of life; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

Knowledge Gaps in Understanding Clinicians’ Experiences

Clinicians’ approaches to supportive and palliative care in AdvLD are the starting point for developing patient-centered models, yet little is known about their experiences with the collaborative planning process. Integrated and collaborative care in serious illness should focus on patients’ outcome goals and care preferences, including end-of-life issues and trade-offs, and should begin early during a serious illness.34 Available literature in other areas of medicine suggests that clinicians may be reluctant to initiate such discussions when patients are not experiencing severe symptoms, or when they have not exhausted curative treatment options.55,56 Almost all (90%) patients receiving dialysis in one study reported that their clinicians had not discussed disease prognosis,57 despite the relatively high annual mortality rate. Clinicians may avoid discussions of prognosis because they are uncertain about prognostic accuracy.58 When clinicians do discuss prognosis, they tend to be overly optimistic,59 which can sway patients to opt for curative care, rather than supportive and palliative care. Literature also suggests that clinicians wait to initiate prognosis conversations until very late in the course of illness, often only days before death, when not much can be done to change a patient’s experience.56,60

Lack of integration of patients’ priorities into the care plan can result in undue focus on curative care even with dwindling chances of transplant, rather than proactively addressing supportive and palliative care goals.55 Ambiguity about the purpose of collaborative planning, who should initiate it, and when in a patient’s trajectory it needs to occur can impede collaborative care. Some of these aspects (eg, who should initiate these discussions) are being addressed in an ongoing large randomized controlled trial. However, other questions (patients understanding of the purpose of planning and when it needs to occur) remain unanswered. Other barriers include clinicians knowledge gaps, low motivation, doubts about collaborative planning efficacy, and barriers to availability and reimbursement for palliative and supportive care.55,61 Clinicians may feel uncomfortable having conversations about patients’ care preferences, outcome goals, and trade-offs for the fear of generating anxiety or negative emotions in patients.33 For example, a recent proof-of-concept study to identify patient priorities in routine medical encounters demonstrated that clinicians find the process to be rewarding yet challenging, mostly owing to lack of patients’ readiness to engage in such discussions.33 Time constraints and inadequate training can be significant barriers to collaborative treatment planning. There are no direct data about clinician experiences with AdvLD treatment and how they may incorporate collaborative treatment planning into normal clinical workflows.

Conceptual Framework for an Integrated Model of Collaborative AdvLD Care

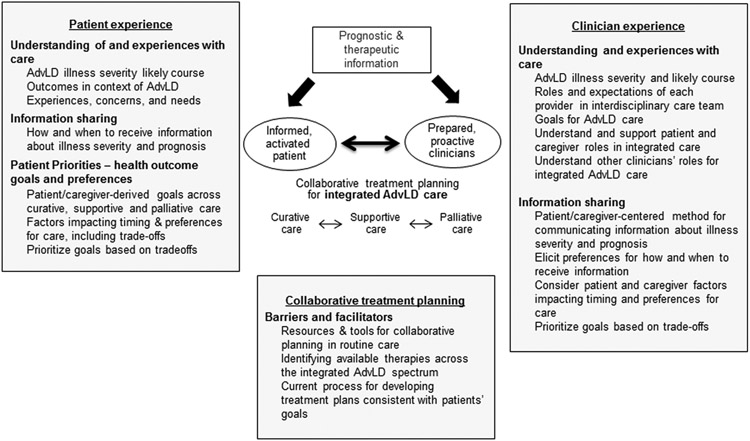

Building from the chronic care model and observations that patient, clinician, and system factors all contribute to deficiencies in patient-centered care for serious chronic illness,55,62 we propose a framework for patient-centered AdvLD care (Figure 2) with collaborative treatment planning among patients, their caregivers, and clinicians as its central, critical element.

Figure 2.

The integrated model for patient-centered advanced liver disease care. AdvLD, advanced liver disease

Our framework, drawn from several aligned models of care,31-33,55 is predicated on conditions necessary for promoting collaborative treatment planning, including (1) patients’, caregivers’, and clinicians’ understanding of illness prognosis and available therapeutics (including understanding of transplant eligibility and preferences and processes for information sharing); (2) explication of patients’ experiences of care, outcome goals, and care preferences33; (3) clarification of clinicians’ attitudes toward, experiences with, and capacity to integrate supportive and palliative care31; and (4) identification of structures and processes that facilitate delivery of coordinated interdisciplinary, patient-centered AdvLD care. Pursuant to the latter, the framework also draws on the Normalization Process Model,63 which postulates that “normal,” routine clinical practices reflect local professional relationships and organization structures and that planned changes must take existing arrangements into account. These include clinicians’ understanding of their own and patients’ roles, willingness to incorporate changes, and the resources needed to “normalize” new care.

Moving Toward Individualized Collaborative, Integrated AdvLD Care

Individualized collaborative treatment planning in serious illness involves developing shared understanding and thus a shared mental model among patients, caregivers, and clinicians about what to expect in terms of disease progression, patient and caregiver priorities, and what therapeutic options are available (and realistic) in light of these priorities and AdvLD status. A collaborative care model of patient-centered AdvLD care also requires tools for eliciting patient’s life context, extent of social support, and patient and caregiver priorities (ie, their preferences for care and their health outcome goals),33 and the alignment of treatments and services to achieve these goals.

To guide patients, caregivers, and clinicians through the process of individualized collaborative, integrated AdvLD care, we propose the development of the following strategies: (1) more accurate prognostic tools; (2) informed tactics for eliciting patients’ understandings of their illness, their goals for treatment (including eligibility for transplant), and their preferences for treatment strategies; and (3) analogous processes for identifying physicians’ preferences in light of these prognosis tools and awareness of patient preferences.

The first calls for quantitative modeling that more comprehensively capitalizes on granular data available in most modern electronic medical records and advanced analytical models to better predict outcomes. High-quality data on AdvLD prognosis and novel quantitative approaches can be applied to this data to measure AdvLD severity and model the likelihood of health outcomes that matter most to patients and caregivers.

The second and third call for largely qualitative inquiries into how patients and their clinicians understand the 2 parallel realities of AdvLD (chance of receiving curative liver transplant and a high risk of death) and derive outcome goals, care preferences, and treatment strategies to meet these goals. Data from patients would define the typical issues and concerns of patients, including knowing what to ask about and how to ask patients dealing with AdvLD. These interviews could elaborate the range of curative, supportive and palliative, and end-of-life-related outcome goals. These data can also facilitate the development of decision support tools to guide patients and caregivers in prioritizing and communicating their goals. Similarly, clinicians could provide a rich understanding of their experiences of and attitudes toward providing integrated AdvLD care, their understanding of their roles and expectations, perceptions of patients’ and other clinicians’ roles, and their willingness to incorporate new or adapted skills and responsibilities for themselves and others in delivering AdvLD care. Data can also identify the ideal workflow and referral patterns among clinicians providing different aspects of integrated AdvLD care.

Collectively, these data can inform the design of various decision support tools that incorporate prognostic data, patients’ priorities, and the identification of available AdvLD treatments that align with patient priorities. Similar to all implementation efforts, these tools and processes may be met with patient, clinician, and system-level barriers. Successful implementation may be facilitated by simultaneously assessing how different kinds of evidence inform current practices and understanding the impact of contextual features of AdvLD care, including but not limited to geography, financial incentives, and local culture and workflows.64 Data from these assessments can serve as the foundation to develop explicit clinical workflows, clinician and team training modules, and incentives for developing processes and structures to overcome barriers and allow sustainable implementation of an individualized patient-centered model of AdvLD care that integrates curative, and supportive and palliative care in routine clinical encounters.

Conclusions

Recent patient-centered models of care in other conditions, such as cancer, have promoted early integration of curative care with supportive and palliative care. These models can improve quality and even length of life.28 Integrated care models may be even more important in noncancer conditions such as AdvLD, in which disease course can be more prolonged and uncertain, yet much can be done with patients to reduce complications and maintain both function and well-being.31 However, there are several reasons why patient-centered integrated models for AdvLD have been slow to develop. The possibility of receiving curative liver transplantation has traditionally conflicted with receipt of supportive and palliative care. Several other reasons at the patient and clinician levels have delayed the development of an integrated care model. We describe these reasons, identify the key gaps in knowledge, and present a framework to fill these gaps crucial to developing integrated patient-centered care for AdvLD. We conclude that successful early integration of curative care with supportive and palliative care should be truly patient centered by focusing on individual health outcome goals.

Funding

This material is based on work supported by Investigator Initiated Research Award Number I01 HX002204-01 from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Health Services Research & Development Service of the VA Office of Research and Development. The work is also supported in part by the Veterans Administration Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN 13-413), Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center, Houston, Texas. The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- AdvLD

advanced liver disease

- HCC

hepatocellular cancer

- HRQOL

Health-Related Quality of Life

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

The authors disclose no conflicts.

References

- 1.Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001–2013. Gastroenterology 2015;149:1471–1482.e5; quiz e17–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, Yu X, White D, El-Serag HB. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:301–308.e1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.D’Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol 2006;44:217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ratib S, Fleming KM, Crooks CJ, Aithal GP, West J. 1 and 5 year survival estimates for people with cirrhosis of the liver in England, 1998-2009: A large population study. J Hepatol 2014;60:282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J, Rakoski MO, Lok AS. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, et al. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2001;120:170–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanwal F, Spiegel B, Hays R, et al. Prospective validation of the short form liver disease quality of life instrument. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2008;28:1088–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Backus LI, Boothroyd DB, Phillips BR, Belperio P, Halloran J, Mole LA. A sustained virologic response reduces risk of all-cause mortality in patients with hepatitis C. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;9:509–516.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Afdhal N, et al. Improvement of health-related quality of life and work productivity in chronic hepatitis C patients with early and advanced fibrosis treated with ledipasvir and sofosbuvir. J Hepatol 2015;63:337–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldberg DS, French B, Forde KA, et al. Association of distance from a transplant center with access to waitlist placement, receipt of liver transplantation, and survival among US veterans. JAMA 2014;311:1234–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. An explicit quality indicator set for measurement of quality of care in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010;8:709–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Santos J, Planas R, Pardo A, et al. Spironolactone alone or in combination with furosemide in the treatment of moderate ascites in nonazotemic cirrhosis. A randomized comparative study of efficacy and safety. J Hepatol 2003;39:187–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stanley MM, Ochi S, Lee KK, et al. Peritoneovenous shunting as compared with medical treatment in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and massive ascites. N Engl J Med 1989;321:1632–1638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel AA, Walling AM, Ricks-Oddie J, May FP, Saab S, Wenger N. Palliative care and health care utilization for patients with end-stage liver disease at the end of life. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15:1612–1619.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bolondi L, Sofia S, Siringo S, et al. Surveillance programme of cirrhotic patients for early diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a cost effectiveness analysis. Gut 2001;48:251–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gluud LL, Klingenberg S, Nikolova D, Gluud C. Banding ligation versus beta-blockers as primary prophylaxis in esophageal varices: systematic review of randomized trials. Am J Gastroenterol 2007;102:2842–2848; quiz 2841, 2849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bass NM, Mullen KD, Sanyal A, et al. Rifaximin treatment in hepatic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1071–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Khan A, Tansel A, White DL, et al. Efficacy of psychosocial interventions in inducing and maintaining alcohol abstinence in patients with chronic liver disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;14:191–202.e1–4; quiz e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buchanan PM, Kramer JR, El-Serag HB, et al. The quality of care provided to patients with varices in the department of Veterans Affairs. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:934–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Buchanan P, et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology 2012;143:70–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poonja Z, Brisebois A, van Zanten SV, Tandon P, Meeberg G, Karvellas CJ. Patients with cirrhosis and denied liver transplants rarely receive adequate palliative care or appropriate management. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:692–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Walling AM, Asch SM, Lorenz KA, Wenger NS. Impact of consideration of transplantation on end-of-life care for patients during a terminal hospitalization. Transplantation 2013;95:641–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bruera E, Hui D. Integrating supportive and palliative care in the trajectory of cancer: establishing goals and models of care. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:4013–4017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Back AL, Park ER, Greer JA, et al. Clinician roles in early integrated palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A qualitative study. J Palliat Med 2014;17:1244–1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Temel JS, Greer JA, Admane S, et al. Longitudinal perceptions of prognosis and goals of therapy in patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer: Results of a randomized study of early palliative care. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:2319–2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas TH, Jackson VA, Carlson H, et al. Communication differences between oncologists and palliative care clinicians: a qualitative analysis of early, integrated palliative care in patients with advanced cancer. J PalliatMed 2019;22:41–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bickel KE, McNiff K, Buss MK, et al. Defining high-quality palliative care in oncology practice: an American Society of Clinical Oncology/American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine guidance statement. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:e828–e838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walling AM, Wenger NS. Palliative care and end-stage liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;12:699–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larson AM. Palliative care for patients with end-stage liver disease. Curr Gastroenterol Rep 2015;17:440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tinetti ME, Naik AD, Dodson JA. Moving from disease-centered to patient goals–directed care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: Patient value-based care. JAMA Cardiol 2016;1:9–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.D’Ambruoso SF, Coscarelli A, Hurvitz S, et al. Use of a shared mental model by a team composed of oncology, palliative care, and supportive care clinicians to facilitate shared decision making in a patient with advanced cancer. J Oncol Pract 2016;12:1039–1045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naik AD, Dindo L, Van Liew J, et al. Development of a clinically-feasible process for identifying patient health priorities. J Am Geriatr Soc 2018;66:1872–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:1097–1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coulter A, Entwistle VA, Eccles A, Ryan S, Shepperd S, Perera R. Personalised care planning for adults with chronic or long-term health conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;3:CD010523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Austin CA, Mohottige D, Sudore RL, Smith AK, Hanson LC. Tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness: a systematic review. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:1213–1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, Shippee N, Kane RL. Decision aids for advance care planning: an overview of the state of the science. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:408–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kaplan DE, Dai F, Aytaman A, et al. Development and performance of an algorithm to estimate the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score from a national electronic healthcare database. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:2333–2341.e1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bruno S, Saibeni S, Bagnardi V, et al. Mortality risk according to different clinical characteristics of first episode of liver decompensation in cirrhotic patients: a nationwide, prospective, 3-year follow-up study in Italy. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:1112–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Andersen PK, Lash TL, Sørensen HT. Comorbidity and survival of Danish cirrhosis patients: A nationwide population-based cohort study. Hepatology 2008;48:214–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lai JC, Sonnenday CJ, Tapper EB, et al. Frailty in liver transplantation: an expert opinion statement from the American Society of Transplantation Liver and Intestinal Community of Practice. Am J Transplant 2019;19:1896–1906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tandon P, Ismond KP, Riess K, et al. Exercise in cirrhosis: translating evidence and experience to practice. J Hepatol 2018;69:1164–1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Lash TL. Development and validation of a comorbidity scoring system for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology 2014;146:147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Singal AG, Rahimi RS, Clark C, et al. An automated model using electronic medical record data identifies patients with cirrhosis at high risk for readmission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;11:1335–1341.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care 2013;51:368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanwal F, Asch SM, Kramer JR, Cao Y, Asrani S, El-Serag HB. Early outpatient follow-up and 30-day outcomes in patients hospitalized with cirrhosis. Hepatology 2016;64:569–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karel MJ, Mulligan EA, Walder A, Martin LA, Moye J, Naik AD. Valued life abilities among veteran cancer survivors. Health Expect 2016;19:679–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Naik AD, Martin LA, Moye J, Karel MJ. Health values and treatment goals of older, multimorbid adults facing life-threatening illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 2016;64:625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kimbell B, Murray SA. What is the patient experience in advanced liver disease? A scoping review of the literature. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2013;5:471–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Etkind SN, Bristowe K, Bailey K, Selman LE, Murtagh FE. How does uncertainty shape patient experience in advanced illness? A secondary analysis of qualitative data. Palliat Med 2017;31:171–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimbell B, Boyd K, Kendall M, Iredale J, Murray SA. Managing uncertainty in advanced liver disease: a qualitative, multiperspective, serial interview study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abdi F, Daryani NE, Khorvash F, Yousefi Z. Experiences of individuals with liver cirrhosis. Gastroenterol Nurs 2015;38:252–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kendall M, Carduff E, Lloyd A, et al. Different experiences and goals in different advanced diseases: comparing serial interviews with patients with cancer, organ failure, or frailty and their family and professional carers. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:216–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saracino RM, Jutagir DR, Cunningham A, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity, health-related quality of life, and mental health service utilization among patients awaiting liver transplant. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;56:44–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernacki RE, Block SD. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ufere NN, Donlan J, Waldman L, et al. Physicians’ perspectives on palliative care for patients with end-stage liver disease: a national survey study. Liver Transpl 2019;25:859–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;5:195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Arnold RM, Tattersall MH. Discussing life expectancy with terminally ill cancer patients and their carers: a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christakis NA. Death foretold: prophecy and prognosis in medical care. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fricker ZP, Serper M. Current knowledge, barriers to implementation, and future directions in palliative care for end-stage liver disease. Liver Transpl 2019;25:787–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tinetti ME, Esterson J, Ferris R, Posner P, Blaum CS. Patient priority–directed decision making and care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions. Clin Geriatr Med 2016;32:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Elwyn G, Légaré F, van der Weijden T, Edwards A, May C. Arduous implementation: Does the Normalisation Process Model explain why it’s so difficult to embed decision support technologies for patients in routine clinical practice. Implement Sci 2008;3:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. BMJ Qual Saf 1998;7:149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Day R, Hollywood C, Durrant D, Perkins P. Patient experience of non-malignant ascites and its treatment: a qualitative study. Int J Palliat Nurs 2015;21:372–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kunzler-Heule P, Beckmann S, Mahrer-Imhof R, Semela D, Handler-Schuster D. Being an informal caregiver for a relative with liver cirrhosis and overt hepatic encephalopathy: a phenomenological study. J Clin Nurs 2016;25:2559–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]