Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the characteristics and methodology consistency in nursing research with descriptive phenomenological design.

Design

Scoping review methodology.

Data sources

Three electronic databases (CINAHL, Embase, PubMed) were systematically searched for qualitative studies with a descriptive phenomenological design published in nursing journals between January 2021 and December 2021.

Review methods

Quality appraisal of each study was conducted using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist. Data were extracted and presented narratively based on research objective, design justification and consistency, theoretical framework, sampling method and sample size, data collection method, data analysis approach and presentation of findings.

Results

One hundred and three studies were included in the review. Overall, the characteristics of the studies are mostly consistent with Husserl's phenomenology approach in terms of research objectives, the use of other theoretical frameworks, sampling and data collection methods. However, the findings revealed several inconsistencies between research design and data analysis techniques, the lack of design justification and the lack of mention of bracketing.

Conclusions

Apart from the need for more research and standardized guidelines to clarify the various qualitative research methods, future nurse researchers are urged to provide more methodological details when publishing a descriptive phenomenological study so that readers can examine the effectiveness and quality of the method.

Keywords: methods, nursing research, peer‐review, qualitative research, scoping review

Impact.

What problem did the study address?

Descriptive phenomenology is increasingly used in nursing research to answer ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions in nursing science, but it is uncertain whether nurse researchers who practice descriptive phenomenology share the same understanding of the research design used.

What were the main findings?

The methodology of nursing studies published in 2021 that self‐report a descriptive phenomenology design is mostly consistent with Husserl's described approach apart from several inconsistencies between research design and data analysis techniques, the lack of design justification and the lack of mention of bracketing.

Where and on whom will the research have an impact?

Nurse researchers are recommended to justify their research design used, provide more methodological details, including bracketing process when publishing a descriptive phenomenology study. Nursing research institutions are urged to update, clarify and standardized research guidelines for different qualitative research methods.

1. INTRODUCTION

Qualitative research methods have been receiving increasing recognition in healthcare and nursing research, as it seeks to understand a natural phenomenon through the emphasis on the meaning, views and experiences of participants (Al‐Busaidi, 2008). As nurse researchers strive to develop knowledge that embraces the ideals of holistic nursing, it is essential for nurse researchers to understand human experiences in health and illness and explore the needs of both nurses, patients and other stakeholders (Wojnar & Swanson, 2007). Learning from the experiences of others allows nurse researchers to glean insights about a particular phenomenon and maximizes the effectiveness of feedback and workplace learning (Neubauer et al., 2019). In recent decades, ‘phenomenology’ has become a frequently used term in nursing research and phenomenology has become a key guiding philosophy in generating nursing‐related knowledge (Koivisto et al., 2002; Moi & Gjengedal, 2008; Woodgate et al., 2008). The phenomenological method, which emphasizes on lived experiences, has been deemed the closest fit conceptually to clinical nursing research as it provides a new way to interpret the nature of individual's consciousness and is commonly used to answer ‘what’ and ‘how’ questions in nursing science (Beck, 1994; Lopez & Willis, 2004; Neubauer et al., 2019).

1.1. Background

Phenomenology is rooted in the philosophical tradition developed by Edmund Husserl in the early 20th century which was later expanded on by his followers at the universities in Germany and subsequently spread to the rest of the world (Zahavi, 2003). Husserl's ideas about how science should be conducted resulted in the development of a descriptive phenomenological inquiry method (Cohen, 1987), which is aligned with the naturalism doctrine that denies a strong separation between scientific and philosophical methodologies and rejects logical positivism's focus on objective observations of external reality (Freeman, 2021; Neubauer et al., 2019). However, Husserl's concept of phenomenology has been criticized by other existentialists and philosophers, resulting in a variation of phenomenology types, such as the more renowned Heidegger's (1988) transcendental hermeneutic phenomenology and Maurice Merleau‐Ponty's (1965) embodied phenomenology.

Husserl argued that the focus of a study should be the phenomenon perceived by the individual's consciousness and that consciousness was central to all human experience. Husserl posits that the events or life situations that humans live through are held within one's consciousness prereflectively and that humans are able to reflect, discover and access this consciousness, thus bringing forward one's lifeworld or lived experience (Willis et al., 2016). The common features of lived experiences of people who underwent the same event or life situation are labelled as universal essences or eidetic structures (Lopez & Willis, 2004). Therefore, the goal of descriptive phenomenology is to describe the universal essence of an experience as lived, which represents the true nature of the phenomenon (Lopez & Willis, 2004; Willis et al., 2016).

Since the description of an individual's direct lived experience is central to Husserl's phenomenology, Husserl maintained that no assumptions, a priori scientific or philosophical theory, empirical science, deductive logic procedures should inform the phenomenology's inquiry (Lopez & Willis, 2004; Moran, 2002). Another tenet of Husserl's phenomenology is that humans are ‘free agents’ uninfluenced by the social and cultural environment they lived in, and thus nurse researchers should not pay attention to the socio‐cultural contexts of people being studied (Lopez & Willis, 2004; Matua & Van Der Wal, 2015; Wojnar & Swanson, 2007).

In descriptive phenomenology, the researcher's goal is to achieve transcendental subjectivity, described as a state where ‘the impact of the researcher on the inquiry is constantly assessed and biases and preconceptions neutralized, so that they do not influence the object of study’ (Lopez & Willis, 2004). This state can be achieved through phenomenological reduction that is facilitated by epoche (the process of bracketing). Bracketing requires researchers to hold off one's ideas in abeyance or bracket off assumptions, past knowledge and understanding of a phenomenon (Ashworth, 1996). Various types of bracketing have been mentioned in Gearing's (2004) study, such as ideal, descriptive, existential, analytic, reflexive and pragmatic bracketing. In order to bracket off biases and preconceived notions, some researchers even suggested not conducting a literature review before the initiation of the study and not having specific research questions that could potentially be leading (Speziale & Carpenter, 2011). The specific process to analyse collected data varies across researchers, with the most commonly used method being Colaizzi's (1978) and Giorg’s (2003) phenomenological analysis. Colaizzi's seven‐step approach include familiarization, identifying significant statements, formulating meanings, clustering themes, developing an exhaustive description and seeking verification of the fundamental structure (Morrow et al., 2015), whereas Giorgi's five‐step approach include contemplative dwelling on descriptions, identifying meaning units, identifying focal meaning, synthesize situated structural descriptions and synthesize a general structural description (Aldiabat et al., 2021; Giorgi & Giorgi, 2003; Russell & Aquino‐Russell, 2011).

An issue with many qualitative studies is the lack of relationship between the methodology used and the philosophical underpinnings that are supposed to guide the process (Lopez & Willis, 2004; Stubblefield & Murray, 2002). Previous research has tried to distinguish the types of qualitative research methods by drawing theoretical and methodological comparisons between qualitative description, interpretive phenomenology, descriptive phenomenology and hermeneutic phenomenology (Lopez & Willis, 2004; Matua & Van Der Wal, 2015; Neubauer et al., 2019; Reiners, 2012; Willis et al., 2016; Wojnar & Swanson, 2007). While valuable, it is uncertain whether researchers who practice descriptive phenomenology share the same understanding of the research design used. Therefore, it is imperative to consolidate an updated overview and evaluate the methodological consistency of peer‐reviewed studies that claimed to have used a descriptive phenomenological approach in the nursing context. Such reviews have been done for descriptive qualitative studies (Kim et al., 2017) and phenomenological studies in the nursing context (Beck, 1994; Norlyk & Harder, 2010) where methodological approaches are compared across nursing studies with the same research design. Given the constant evolution of phenomenological methods and the increasing interest in nursing research, this review aims to consolidate updated evidence and comprehensively map the characteristics and methodology used in nursing research with descriptive phenomenological design to improve standardization and inform future nursing methodological research.

2. THE REVIEW

2.1. Aim

The aim of this review was to provide an overview and to evaluate the characteristics and methodology consistency in nursing research with descriptive phenomenological design.

2.2. Design

A scoping review was conducted to identify and map all relevant evidence on the use of descriptive phenomenological design in nursing research. A scoping review design was deemed the most appropriate as it aims to ‘map the literature on a particular topic or research area and provide an opportunity to identify key concepts; gaps in the research and types and sources of evidence to inform practice, policymaking and research’ (Daudt et al., 2013). This review was guided by Arksey and O′Malley's (2005) five‐stage framework: identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data and collating, summarizing and reporting the results. This review is reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA) Extension for Scoping Reviews (Tricco et al., 2018). There is no registered protocol.

2.3. Search methods

In January 2022, three electronic databases (CINAHL, Embase and Pubmed) were searched for qualitative studies with a descriptive phenomenological design published between January 2021 and December 2021 in nursing journals. Given a large number of qualitative studies, we have narrowed the search to the most recent year, 2021, to include more updated and relevant research articles. Based on a research analytics tool, the 2021 Journal Citation Reports Science Edition (Clarivate Analytics, 2021), 181 journals were identified under the nursing category. In addition to the journal titles, search terms generated were derived from the concept ‘descriptive phenomenological’. The sample search strategy for PubMed is available in Material S1 and the representation of nursing journals indexed in each database is available in Material S2.

Studies were included if they (i) explicitly mentioned using a descriptive phenomenological study design or analysis in the main text, (ii) published in 2021, (iii) published in the English language and (iv) published in one of the 181 nursing journals. Studies were excluded if they (i) were not of qualitative nature, or (ii) explicitly stated the use of an interpretive or hermeneutical phenomenological approach or other qualitative design. Ambiguous studies that have ‘descriptive qualitative phenomenological’ designs or ‘descriptive qualitative grounded in phenomenological approach’ were included. Online preprints that were available as of 31 December 2021 were included. Quantitative studies, reviews, pilot studies, protocols, editorials and conference abstracts were excluded.

2.4. Study selection

References and citations from the database search were exported into a reference management software, EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics), where duplicates were removed. Article titles and abstracts were then screened for relevance by two reviewers independently. The full texts of shortlisted articles were downloaded and assessed for eligibility against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by two reviewers. The interrater agreement was approximately 96% and any inconsistencies were resolved through discussions between both reviewers until a mutual consensus is reached

2.5. Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal of the finalized studies was conducted by two reviewers independently using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) qualitative checklist (CASP, 2019). The CASP tool is a generic and most used tool for quality appraisal in social and healthcare‐related qualitative evidence syntheses and is also endorsed by Cochrane and World Health Organization (Long et al., 2020). Therefore, the CASP tool was chosen to appraise the rigour of the qualitative studies included in this study. The CASP tool consists of 10 main questions and several subquestions that examine the clarity and appropriateness of the study aim, research design (sampling, data collection, data analysis), and the presentation of results. As the CASP was used to gauge the overall rigour of included studies, no studies were excluded based on the CASP results.

2.6. Charting the data

A tabular data extraction form was created using Microsoft Excel with reference to a previous study (Kim et al., 2017). The following data were extracted from each study: First author name, country of origin, research objective, design justification and consistency, theoretical framework, sampling method and sample size, data collection method, data analysis approach and presentation of findings. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and cross‐checked with the second reviewer. Inconsistencies were resolved through discussion until a consensus is reached.

2.7. Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

The characteristics of the included studies are summarized in frequencies and percentages. Methodological consistency within and between studies and unique features observed from the extracted data will be discussed narratively. Extracted data from each study are presented in Table S1. Ethical approval and informed consent were not sought as no participants were recruited for this study. Given a large number of included studies, the references are provided in Material S3.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search outcomes

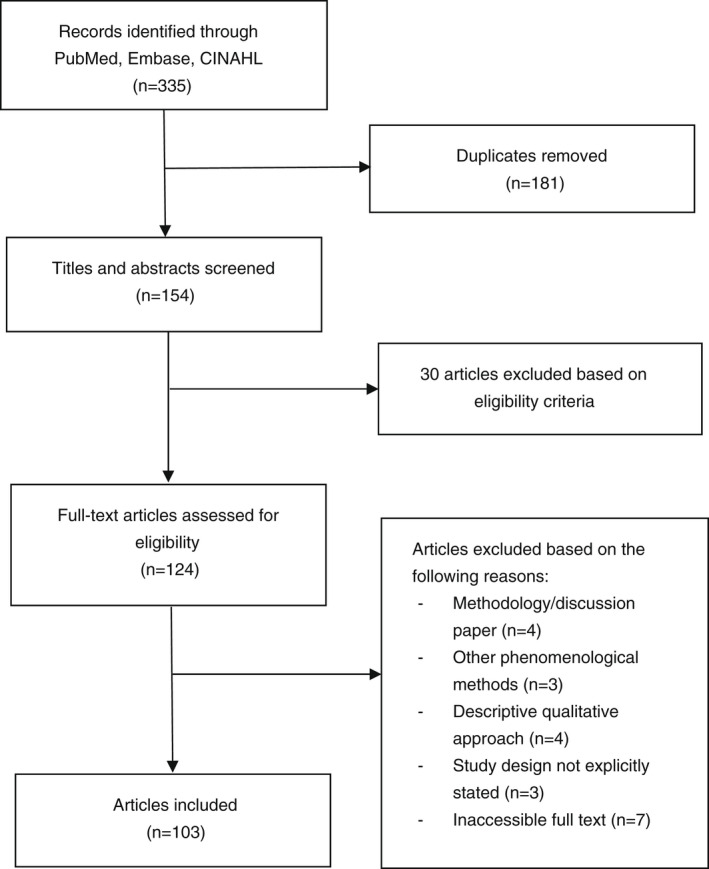

The initial search yielded 335 articles. After removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts of 154 articles were screened for relevance, and 124 full‐text articles were shortlisted and assessed for eligibility, resulting in 103 finalized articles being included in the study. The PRISMA diagram summarizing the screening process is found in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

Of the 103 studies, the majority was conducted in Asia (n = 51, 50%), and North America (n = 27, 25%), followed by Europe (n = 15, 15%), Africa (n = 6, 6%), Oceania (i.e. Australia) (n = 3, 3%) and South America (n = 1, 1%). Six of the studies were post‐intervention studies (Ingersgaard et al., 2021; Jensen et al., 2021; Jerntorp et al., 2021; Macapagal et al., 2021; Mathews & Anderson, 2021; Schumacher et al., 2021) and one was a part of a larger mix‐methods study (Mohaupt et al., 2021).

3.3. Quality appraisal

All studies had a clear statement of research aims, but only 65 studies (63.1%) justified the use of a descriptive phenomenological research design and 78 (75.7%) studies elaborated on the participant selection process in addition to stating the sampling method and participant eligibility criteria. Although all studies clearly stated how data were collected, 74 (71.8%) did not justify the method chosen, and only 77 (74.8%) studies discussed data saturation. The examination of the relationship between researcher and participants for potential bias and influence was reported in 63 (61.2%) studies. Ethics approval was explicitly stated in 101 (98.1%) studies and 92 (89.3%) provided a detailed description of the data analysis process. All studies reported a clear statement of findings, but only 85 (82.5%) discussed the credibility, rigour or trustworthiness of their findings. The quality appraisal for each study is presented in Material S4, whereas a summary of the quality appraisal is available in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Overall frequency of CASP scoring (N = 103)

| Items | Yes, n (%) | Cannot tell, n (%) | No, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | 103 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 2. Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | 65 (63.1) | 38 (36.9) | 0 (0) |

| a) Did the researcher justify the research design (e.g. have they discussed how they decided which method to use)? | 65 (63.1) | 0 (0) | 38 (36.9) |

| 3. Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | 78 (75.7) | 25 (24.3) | 0 (0) |

| a) Did the researcher explain how the participants were selected? | 78 (75.7) | 0 (0) | 25 (24.3) |

| 4. Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | 103 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| a) Was it clear how data were collected (e.g. focus group, semi‐structured interview etc.)? | 103 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| b) Did the researcher justify the methods chosen? | 29 (28.2) | 0 (0) | 74 (71.8) |

| c) Did the researcher make the methods explicit (e.g. for interview method, is there an indication of how interviews are conducted, or did they use a topic guide) | 100 (97.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (2.9) |

| d) Is the form of data clear? (e.g. tape recordings, notes, video) | 97 (94.2) | 1 (1.0) | 5 (4.8) |

| e) Did the researcher discuss saturation of data? | 77 (74.8) | 0 (0) | 26 (25.2) |

| 5. Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | 63 (61.2) | 0 (0) | 40 (38.8) |

| a) Did the researcher critically examine their own role, potential bias and influence during (i) formulation of the research questions (ii) data collection, including sample recruitment and choice of location? | 63 (61.2) | 0 (0) | 40 (38.8) |

| 6. Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | 101 (98.1) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) |

| a) Was approval sought from the ethics committee? | 101 (98.1) | 2 (1.9) | 0 (0) |

| 7. Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | 92 (89.3) | 11 (10.7) | 0 (0) |

| a) Is there an in‐depth description of the analysis process? (i.e. is it clear how categories/themes were derived) | 92 (89.3) | 0 (0) | 11 (10.7) |

| 8. Is there a clear statement of findings? | 103 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| a) Were the findings explicit? | 103 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| b) Did the researcher discuss the credibility of their findings (e.g. triangulation, respondent validation, more than one analyst) | 85 (82.5) | 0 (0) | 18 (17.5) |

| c) Were the findings discussed in relation to the original research question? | 103 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

3.4. Research objective

Across all 103 studies, the most used verbs in research objectives or aims were “explore” (n = 66, 64%), “describe” (n = 14, 14%), “understand” (n = 12, 12%) and “investigate” (n = 10, 10%). Lesser used verbs include “assess”, “determine”, “examine”, “explain”, “highlight” and “illuminate”. Most studies focused on more generic “experiences” (n = 44, 43%), or “lived experiences (n = 36, 35%), whereas a few others looked at “perceptions”, “coping strategies”, “meaning”, “challenges”, “perspectives”, “motivations”, “needs”, “impact”, “behaviour”, “practices” and “factors” related to a certain phenomenon (e.g. Covid‐19, online learning, caregiving) (n = 89, 86%) or nursing interventions and practices (n = 6, 6%).

3.5. Research design

Out of 103 studies, 81 (79%) studies explicitly mentioned using a ‘descriptive phenomenological’ research design or approach. Four studies reported a generic phenomenological research design but used a descriptive phenomenological data analysis technique (Ghorbani et al., 2021; HeydariKhayat et al., 2021; Luo et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2021). Ten studies reported being a descriptive, qualitative, or descriptive qualitative study ‘with’ or ‘grounded in’ a phenomenological approach. Although seven studies reported adopting a qualitative or descriptive qualitative approach, they proceeded to describe a descriptive phenomenological data analysis technique by Giorgi, Colaizzi or Sundler (Al Gilani et al., 2021; Macapagal et al., 2021; Nuuyoma & Makhene, 2021; Olander et al., 2021; Othman et al., 2021; Ratnawati & Rizaldi, 2021; Sundler et al., 2021). However, one study (George et al., 2021) used a ‘phenomenological approach with descriptive thematic analysis’ without providing references.

Although 58 nurse researchers provided a reference to justify the use of their stated research design, 64 researchers described the rationale behind their choice of research design. The length of rationale descriptions ranged from one‐liner to a full paragraph, with the gist of it being able to explore the essence of the lived experience of a specific phenomenon, especially when little is known about the phenomenon.

3.6. Theoretical framework

Nine studies had other theoretical underpinnings that are unrelated to the descriptive phenomenological design. Woodley et al. (2021) used Choi's Theory of Cultural Marginality in the conceptualization of the study's purpose and research question. Jensen et al. (2021) used the stress‐vulnerability model and transtheoretical model of change as a basis for the development of an intervention. Corcoran et al. (2021) used Benner's Novice to Expert theory to determine the inclusion criteria of the study. Two studies used Lawrence Green's Behaviour Causes theory (Ratnawati & Rizaldi, 2021) and the Disablement Process model to develop interview guides (Seyman & Ozcetin, 2021), and six studies related their findings to theoretical frameworks (continuity theory, Carper's ways of knowing theory, symptom management theory, Khantzian's self‐medication hypothesis, Habermas' system and lifeworld, theory of communicative action, behaviour causes theory, disablement process model) in the discussion section (Aldiabat et al., 2021; Carrasco, 2021; Ghelani, 2021; Ratnawati & Rizaldi, 2021; Ravn Jakobsen et al., 2021; Seyman & Ozcetin, 2021).

However, Seyman and Ozcetin (2021) stated that the theoretical framework ‘guided the data analysis procedure’ and ‘helped in the construction of themes and subthemes’, which may be problematic from a descriptive phenomenology standpoint. Only Ghelani (2021) provided a disclaimer that ‘preconceptions were minimized in the study design through asking open‐ended questions and using dispassionate probes which did not reflect researcher assumptions’.

3.7. Sampling

In 57 out of 103 studies (55%), researchers mentioned using a ‘purposive sampling’ method. Other researchers used snowball sampling (n = 5, 5%), convenience sampling (n = 5, 5%), criterion sampling (n = 3, 3%), maximum variation sampling (n = 2, 2%), or a combination of various sampling methods (purposive and snowball, n = 14, 14%; purposive and criterion, n = 1, 1%; purposive and convenience, n = 1, 1%, purposive and systematic random sampling, n = 1, 1%, purposive and maximum variation, n = 1, 1%, referral sampling, n = 1, 1%). Twelve studies did not explicitly state the sampling method used.

Overall, sample size ranged from four to 62, where focus group studies had a larger sample size range of 15–62, and studies with individual data collection methods had a sample size range of four to 43. Participant recruitment till data saturation was discussed in 77 studies.

3.8. Data collection

Data collection was primarily done through individual interviews (n = 89, 86%), where most were semi‐structured (n = 72, 70%) and some were open‐ended (n = 6, 6%), or unstructured (n = 6, 6%) interviews. The interview duration ranged from 15 to 153 min across 64 studies that reported them. Individual interviews were mainly conducted face‐to‐face (n = 49, 48%), through telephone calls (n = 9, 9%), online means (n = 4, 4%) or a combination of the above (n = 7, 7%). Twenty studies did not specify the mode of interview. Eight studies conducted focus groups which lasted between 60 and 150 min. Two focus groups were conducted face‐to‐face, two were conducted online, and four studies did not specify. Three studies had multiple data collection methods such as a combination of individual and dyadic interviews (Olander et al., 2021), or individual interviews and focus groups (Mathews & Anderson, 2021; Othman et al., 2021). Other online data collection methods included open‐ended questionnaires (Vignato et al., 2021), written narrative reflective inquiry (Schuler et al., 2021), written complaints documented in a report (Sundler et al., 2021), written descriptions and illustrative examples (Aldiabat et al., 2021) sent through email.

3.9. Data analysis

For data analysis, studies often adopted Colaizzi's (1978) seven‐step phenomenological approach (n = 55, 53%) or Giorgi and Giorgi's (2003) five‐step phenomenological approach (n = 14, 14%). However, one study used a modified Colaizzi's approach (Walker et al., 2021). Another study only followed four out of Giorgi's five‐step approach as its ‘overall aim was not to discover the structure of a phenomenon’ (von Essen, 2021). Hycner's and Moustaka's phenomenological methods were used in two studies (Makgahlela et al., 2021; Rygg et al., 2021). Thematic analysis procedures especially by Braun and Clark (2006), Sundler et al. (2019), Spielberg (1975) were also commonly used (n = 16, 16%). Other data analytical procedures used were content analysis (n = 3, 3%), constant comparative method (n = 3, 3%), framework analysis/approach (n = 2, 2%), discourse analysis (n = 1, 1%), Tsech's protocol of data analysis (n = 1, 1%) and Maltreud's (2012) systematic text condensation (n = 1, 1%). Only one study did not disclose their analysis strategy, but the data analysis process was detailed (Yildirim, 2021). Interpretive phenomenological approaches were described in two studies despite them stating having a descriptive phenomenological research design (Arikan Dönmez et al., 2021; Kurevakwesu, 2021).

Bracketing or reflexivity was taken into consideration only in 47 (46%) studies, mainly through reflective journaling or taking field notes. The process of ensuring the trustworthiness and credibility of research findings was described in 82 (80%) studies.

3.10. Presentation of findings

The research findings from all studies were presented in themes and subthemes accompanied with verbatim texts. The findings were described extensively and were consistent with their research objectives.

4. DISCUSSION

This review examined the characteristics and methodology consistency in nursing research with descriptive phenomenological design through the articles published in nursing journals between January 2021 and December 2021. The consolidation of studies revealed that most studies have characteristics that adhered to key features of the Husserlian phenomenology approach. However, inconsistencies between the stated research design and data analysis technique were observed in several studies.

4.1. Consistency of characteristics with descriptive phenomenology

In general, most studies adhered to the goal of descriptive phenomenological research, to ‘explore’ and ‘describe’ the generic ‘lived experiences’ of participants, answering to the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of a phenomenon of interest (Beck, 1994; Lopez & Willis, 2004). The term ‘lived experience’ remains unique to phenomenological studies and it is recommended for researchers to use this term in their research objective.

The majority of included studies did not report the use of another theoretical framework, adhering to Husserl's stance that no a priori theoretical or phenomenological framework should inform the phenomenological inquiry (Lopez & Willis, 2004). A few studies reported using other theories to guide their research methodology (i.e. inclusion criteria, interview guide, data analysis) or simply discuss their findings in relation to the theory. According to Husserl, the use of other theories to translate findings into accessible disciplinary knowledge is possible, however, these theories must be bracketed during the interview process (Willis et al., 2016). The bracketing of preconceptions derived from other theories was only reported by Ghelani (2021).

Most studies used a purposive sampling technique which was lauded by descriptive phenomenology researchers as it is crucial to select participants who have had rich experiences related to the phenomenon of interest and have the cognitive capacity and ability to self‐reflect and express oneself adequately either written or verbally (Groenewald, 2018; Kruger & Stones, 1981; Willis et al., 2016).

In this review, the sample size of included studies ranged from four to 62. Interestingly, there are no specific guidelines for sample size in descriptive phenomenological research yet. Creswell and Miller (2000) recommended between five and 25 participants for a phenomenological study, whereas Giorgi and Giorgi (2008) recommended at least three participants. Since the aim of a descriptive phenomenological approach is to explore in‐depth individual lived experiences of a phenomenon, the sample size should be determined by the quality and completeness of the information provided instead of the number of participants (Malterud et al., 2016; Todres, 2005). Therefore, sampling should continue until data saturation is reached, which was what 70% of the included studies had reported.

Phenomenological interviews either individually or in focus groups are the most common data collection method reported in 95% of included studies. In descriptive phenomenology, although face‐to‐face interview is preferred to elicit ‘rich first‐person accounts of experience’, various data collection tools such as written narrative, online interviews, research diaries, open‐ended interviews or open‐ended questionnaires can also be used (Elliott & Timulak, 2005; Marshall & Rossman, 2014; Morrow et al., 2015). Therefore, there is no specific guideline for the type of data collection method used.

In terms of data analysis, 73% of the studies adhered to established descriptive phenomenological approaches by Colaizzi (1978), Giorgi and Giorgi (2003), Moustakas (Moustakas, 1994) or Hycner (Groenewald, 2018; Hycner, 1985). The thematic analysis procedure for general qualitative studies by Braun and Clarke (2006), or more recently for descriptive phenomenological studies, by Sundler et al. (2019), was second most popular. Further research is needed to validate the appropriateness of other analytical methods such as discourse analysis and framework analysis in the context of descriptive phenomenology. The downside of not using a descriptive‐phenomenology‐specific analytical approach is the potential to neglect phenomenological reduction or bracketing, which is a key feature in descriptive phenomenology research. Startlingly, only less than half of the included studies reported bracketing. Although Merleau‐Ponty (1965) argued that a complete reduction or ‘pure’ bracketing can never be fully completed, it is still a necessary and important step to enhance rigour and to enable researchers to look beyond one's preconceptions and tap directly into the essence of a phenomenon (Matua & Van Der Wal, 2015).

4.2. Inconsistency in research design and analysis

Although most of the included studies explicitly stated having a descriptive phenomenological design, some studies provided vague statements with undertones of other qualitative designs, such as ‘descriptive qualitative study grounded in phenomenological approach’. Apart from the lack of clarity in the stated research design, some studies that reported using a descriptive phenomenology design ended up using an interpretive phenomenological analysis, discourse analysis or framework analysis, which are not congruent to a descriptive phenomenological design. Conversely, some studies reported having a descriptive qualitative research design but adopted Giorgi's or Colaizzi's descriptive phenomenological analysis method. These inconsistencies highlighted the confusion and potential knowledge gap of nurse researchers in utilizing a descriptive phenomenological approach, which necessitates more updated research and clear guidelines for descriptive phenomenological and qualitative studies in the nursing context.

Additionally, the justification of why a descriptive phenomenological approach was appropriate was lacking in half of the included studies. It is crucial for researchers to clarify and justify their choice of approach especially when examining participants' experiences, as this can easily be addressed with other qualitative approaches as well. The justification of research design and methodology could also enhance the rigour of the study as it allows others to evaluate for the choice for internal consistency, provides transparency of choices and context to the findings (Carter & Little, 2007).

A summary of practical implications to promote a standardized reporting of descriptive phenomenological method in nursing research is presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Summary of practical implications on the use of descriptive phenomenology method

| Key components | Practical implications |

|---|---|

| 1. Research objective |

|

| 2. Research design |

|

| 3. Use of theoretical frameworks |

|

| 4. Sampling procedure |

|

| 5. Data collection methods |

|

| 6. Data analysis |

|

| 7. Presentation of findings |

|

4.3. Limitations

Although this review was able to provide an updated overview of descriptive phenomenological methodology in nursing studies, a few limitations exist. First, the narrow inclusion of only studies written in English, the small number of databases searched and the identification of nursing journals through a research analytics tool might have limited potentially relevant nursing studies. Second, a single year limit was used due to overwhelming number of studies and to gather more updated evidence, but this may result in the omission of previous relevant studies and limit the transferability of the findings. Additionally, there was uncertainty in the inclusion of studies that were inferred as descriptive phenomenology based on the research description or data analytical methods, which may have affected the results. Lastly, our findings are highly reliant on what is reported in the published studies, therefore, the methodological data available may be limited by word limits, or specific journal specifications, leaving out certain characteristics that could affect our CASP appraisal.

5. CONCLUSION

This review examined the characteristics and methodological consistencies of descriptive phenomenological nursing studies published in the year 2021. Overall, the characteristics of the studies are mostly consistent with Husserl's phenomenology approach in terms of research objectives, the use of other theoretical frameworks, sampling and data collection methods. However, the findings revealed several inconsistencies between research design and data analysis techniques, the lack of design justification and the lack of mention of bracketing. Apart from the need for more research and standardized guidelines to clarify the various qualitative research methods, future nurse researchers are urged to provide more methodological details when publishing a descriptive phenomenological study, so that readers can examine the appropriateness of the method. We hope this scoping review will pave a path for more conscientious planning, conducting and reporting and in turn better understanding among nurse researchers while adopting a descriptive phenomenology research design.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Shefaly Shorey was involved in conceptualization, methodology and writing—reviewing and editing of the manuscript. Esperanza Debby Ng carried out investigation, data curation and writing—original draft of the manuscript.

PEER REVIEW

The peer review history for this article is available at https://publons.com/publon/10.1111/jan.15244.

Supporting information

Appendix

DataS 1

DataS 2

DataS 3

DataS 4

Shorey, S. & Ng, E. D. (2022). Examining characteristics of descriptive phenomenological nursing studies: A scoping review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 78, 1968–1979. 10.1111/jan.15244

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data available in article supplementary material

REFERENCES

- Al‐Busaidi, Z. Q. (2008). Qualitative research and its uses in health care. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 8(1), 11–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al Gilani, S. , Tingö, L. , Kihlgren, A. , & Schröder, A. (2021). Mental health as a prerequisite for functioning as optimally as possible in old age: A phenomenological approach. Nursing Open, 8(5), 2025–2034. 10.1002/nop2.698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aldiabat, K. M. , Alsrayheen, E. , Navenec, C.‐L. , Russell, C. , & Qadire, M. (2021). An enjoyable retirement: Lessons learned from retired nursing professors. Central European Journal of Nursing and Midwifery, 12(2), 315–324. 10.15452/cejnm.2021.12.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arikan Dönmez, A. , Kuru Alici, N. , & Borman, P. (2021, Jul). Lived experiences for supportive care needs of women with breast cancer‐related lymphedema: A phenomenological study. Clinical Nursing Research, 30(6), 799–808. 10.1177/1054773820958115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ashworth, P. (1996). Presuppose nothing! The suspension of assumptions in phenomenological psychological methodology. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 27(1), 1–25. https://go.exlibris.link/jMNFjKV1 [Google Scholar]

- Beck, C. T. (1994). Phenomenology: Its use in nursing research. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 31(6), 499–510. 10.1016/0020-7489(94)90060-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V. , & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, S. (2021). Patients' communication preferences around cancer symptom reporting during cancer treatment: A phenomenological study. Journal of the Advanced Practitioner in Oncology, 12, 364–372. 10.6004/jadpro.2021.12.4.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S. M. , & Little, M. (2007). Justifying knowledge, justifying method, taking action: Epistemologies, methodologies, and methods in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 17(10), 1316–1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarivate Analytics . (2021). 2021 Journal impact factor, Science Edition Clarivate Analytics, Web of Science Group, Boston Journal Citation Reports.

- Cohen, M. Z. (1987). A historical overview of the phenomenologic movement. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 19(1), 31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colazzi, P. (1978). Psychological research as the phenomenologist views it. In Vaile R. S. & King M. (Eds.), Existential phenomenological alternatives for psychology. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran, C. M. (2021). The lived experience of workplace reciprocity of emergency nurses in the mid‐Atlantic region of the U.S.: A descriptive phenomenological study. International Emergency Nursing, 58, 101044. 10.1016/j.ienj.2021.101044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. , & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory Into Practice, 39(3), 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) . (2019). CASP qualitative studies checklist, creative commons attribution [online]. https://ddec1‐0‐enctp.trendmicro.com:443/wis/clicktime/v1/query?url=https%3a%2f%2fcasp%2duk.b%2dcdn.net%2fwp%2dcontent%2fuploads%2f2018%2f03%2fCASP%2dQualitative%2dChecklist%2d2018%5ffillable%5fform.pdf&umid=11f5b933‐a6b7‐4dd8‐92a5‐a23958fc7822&auth=8d3ccd473d52f326e51c0f75cb32c9541898e5d5‐f263178f2a1a280b05e5162f165d3ab6e68f4697 [Google Scholar]

- Daudt, H. M. , van Mossel, C. , & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter‐professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(1), 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R. , & Timulak, L. (2005). Descriptive and interpretive approaches to qualitative research. A handbook of research methods for clinical and health psychology, 1(7), 147–159. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, M. (2021). Five threats to Phenomenology's distinctiveness. Qualitative Inquiry, 27(2), 276–282. 10.1177/1077800420912799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gearing, R. E. (2004). Bracketing in research: A typology. Qualitative Health Research, 14(10), 1429–1452. 10.1177/1049732304270394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, D. R. , Snyder, B. , Van Scoy, L. J. , Brignone, E. , Sinoway, L. , Sauder, C. , Murray, A. , Gladden, R. , Ramedani, S. , Ernharth, A. , Gupta, N. , Saran, S. , & Kraschnewski, J. (2021). Perceptions of diseases of despair by members of rural and urban high‐prevalence communities: A qualitative study. JAMA Network Open, 4(7), e2118134. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.18134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghelani, A. (2021). Motives for recreational cannabis use among mental health professionals. Journal of Substance Use, 26(3), 256–260. 10.1080/14659891.2020.1812124 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, A. , Shali, M. , Matourypour, P. , Salehi Morkani, E. , Salehpoor Emran, M. , & Nikbakht Nasrabadi, A. (2021). Explaining nurses' experience of stresses and coping mechanisms in coronavirus pandemic. Nursing Forum, 57, 18–25. 10.1111/nuf.12644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, A. P. , & Giorgi, B. M. (2003). The descriptive phenomenological psychological method. In Camic P. M., Rhodes J. E., & Yardley L. (Eds.), Qualitative research in psychology: Expanding perspectives in methodology and design (pp. 243–273). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Giorgi, A. P. , & Giorgi, B. (2008). Phenomenological psychology. In The SAGE handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 165–178). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, T. (2018). Reflection/commentary on a past article: “A phenomenological research design illustrated”. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 160940691877466. 10.1177/1609406918774662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heidegger, M. (1988). The basic problems of phenomenology (Vol. 478). Indiana University Press. [Google Scholar]

- HeydariKhayat, N. , Ashktorab, T. , & Rohani, C. (2021). Home care for burn survivors: A phenomenological study of lived experiences. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 40(3), 204–217. 10.1080/01621424.2020.1749206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hycner, R. H. (1985). Some guidelines for the phenomenological analysis of interview data. Human Studies, 8(3), 279–303. [Google Scholar]

- Ingersgaard, M. V. , Fridh, M. K. , Thorsteinsson, T. , Adamsen, L. , Schmiegelow, K. , & Bækgaard Larsen, H. (2021). A qualitative study of adolescent cancer survivors perspectives on social support from healthy peers – A RESPECT study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 77(4), 1911–1920. 10.1111/jan.14732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, S. B. , Eplov, L. F. , Mueser, K. T. , & Petersen, K. S. (2021). Participants' lived experience of pursuing personal goals in the illness management and Recovery program. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(4), 360–368. 10.1177/0020764020954471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerntorp, S. H. , Sivberg, B. , & Lundqvist, P. (2021). Fathers' lived experiences of caring for their preterm infant at the neonatal unit and in neonatal home care after the introduction of a parental support programme: A phenomenological study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(4), 1143–1151. 10.1111/scs.12930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H. , Sefcik, J. S. , & Bradway, C. (2017). Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(1), 23–42. 10.1002/nur.21768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koivisto, K. , Janhonen, S. , & Väisänen, L. (2002). Applying a phenomenological method of analysis derived from Giorgi to a psychiatric nursing study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 39(3), 258–265. 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, D. , & Stones, C. R. (1981). An introduction to phenomenological psychology. Duquesne University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kurevakwesu, W. (2021). COVID‐19 and mental health services delivery at Ingutsheni central Hospital in Zimbabwe: Lessons for psychiatric social work practice. International Social Work, 64(5), 702–715. 10.1177/00208728211031973 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long, H. A. , French, D. P. , & Brooks, J. M. (2020, 2020/09/01). Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences, 1(1), 31–42. 10.1177/2632084320947559 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, K. A. , & Willis, D. G. (2004). Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their Contributions to nursing knowledge. Qualitative Health Research, 14(5), 726–735. 10.1177/1049732304263638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C. , Lei, L. , Yu, Y. , & Luo, Y. (2021, Apr 15). The perceptions of patients, families, doctors, and nurses regarding malignant bone tumor disclosure in China: A qualitative study. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 32(6), 740–748. 10.1177/10436596211005532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macapagal, F. R. , Bonuel, R. , Rodriguez, H. , & McClellan, E. (2021, Aug 1). Experiences of patients using a fitness tracker to promote ambulation before a heart transplant. Critical Care Nurse, 41(4), e19–e27. 10.4037/ccn2021516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makgahlela, M. , Sodi, T. , Nkoana, S. , & Mokwena, J. (2021). Bereavement rituals and their related psychosocial functions in a northern Sotho community of South Africa. Death Studies, 45(2), 91–100. 10.1080/07481187.2019.1616852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. (2012). Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(8), 795–805. 10.1177/1403494812465030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud, K. , Siersma, V. D. , & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, C. , & Rossman, G. B. (2014). Designing qualitative research. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, G. , & Anderson, C. (2021). The lived experience of learning mindfulness as perceived by people living with Long‐term conditions: A community‐based, longitudinal phenomenological study. Qualitative Health Research, 31(7), 1209–1221. 10.1177/1049732321997130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matua, G. A. , & Van Der Wal, D. M. (2015). Differentiating between descriptive and interpretive phenomenological research approaches. Nurse Researcher, 22(6), 22–27. 10.7748/nr.22.6.22.e1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merleau‐Ponty, M. (1965). Phenomenology of perception. Translated by Colin Smith.

- Mohaupt, H. , Duckert, F. , & Askeland, I. R. (2021). How do memories of having been parented relate to the parenting‐experience of fathers in treatment for intimate partner violence? A phenomenological analysis. Journal of Family Violence, 36(4), 467–480. 10.1007/s10896-020-00210-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moi, A. L. , & Gjengedal, E. (2008). Life after burn injury: Striving for regained freedom. Qualitative Health Research, 18(12), 1621–1630. 10.1177/1049732308326652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran, D. (2002). Introduction to phenomenology. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow, R. , Rodriguez, A. , & King, N. (2015). Colaizzi's descriptive phenomenological method. The Psychologist, 28(8), 643–644. [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Neubauer, B. E. , Witkop, C. T. , & Varpio, L. (2019). How phenomenology can help us learn from the experiences of others. Perspectives on Medical Education, 8(2), 90–97. 10.1007/s40037-019-0509-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norlyk, A. , & Harder, I. (2010). What makes a phenomenological study phenomenological? An analysis of peer‐reviewed empirical nursing studies. Qualitative Health Research, 20(3), 420–431. 10.1177/1049732309357435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nuuyoma, V. , & Makhene, A. (2021). The use of clinical practice to facilitate community engagement in the Faculty of Health Science. Nurse Education in Practice, 54, 1–6. 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.103102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olander, A. , Bremer, A. , Sundler, A. J. , Hagiwara, M. A. , & Andersson, H. (2021). Assessment of patients with suspected sepsis in ambulance services: A qualitative interview study. BMC Emergency Medicine, 21(1), 1–9. 10.1186/s12873-021-00440-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Othman, E. H. , Khalaf, I. A. , Zeilani, R. , Nabolsi, M. , Majali, S. , Abdalrahim, M. , & Shamieh, O. (2021). Involvement of Jordanian patients and their families in decision making near end of life, challenges and recommendations. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 23(6), E20–E27. 10.1097/NJH.0000000000000792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratnawati, R. , & Rizaldi, D. A. (2021). Mental health officer behavioural in Mbah Jiwo's mental healthcare post on the recovery of people with mental disorder: A qualitative study. International Journal of Public Health & Clinical Sciences (IJPHCS), 8(4), 27–40. http://libproxy1.nus.edu.sg/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=152720262&site=ehost‐live [Google Scholar]

- Ravn Jakobsen, P. , Hermann, A. P. , Søendergaard, J. , Kock Wiil, U. , Myhre Jensen, C. , & Clemensen, J. (2021). The gap between women's needs when diagnosed with asymptomatic osteoporosis and what is provided by the healthcare system: A qualitative study. Chronic Illness, 17(1), 3–16. 10.1177/1742395318815958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiners, G. M. (2012). Understanding the differences between Husserl's (descriptive) and Heidegger's (interpretive) phenomenological research. Journal of Nursing & Care, 1(5), 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Russell, R. C. , & Aquino‐Russell, C. E. (2011). Living and working between two worlds: Using qualitative phenomenological findings to enhance understanding of lived experiences. In The role of expatriates in MNCs knowledge mobilization. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Rygg, L. Ø. , Brataas, H. V. , & Nordtug, B. (2021). Oncology nurses' lived experiences of video communication in follow‐up care of home‐living patients: A phenomenological study in rural Norway [article]. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 52, 101955. 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuler, M. S. , Letourneau, R. , Altmiller, G. , Deal, B. , Vottero, B. A. , Boyd, T. , Ebersole, N. W. , Flexner, R. , Jordan, J. , Jowell, V. , McQuiston, L. , Norris, T. , Risetter, M. J. , Szymanski, K. , & Walker, D. (2021). Leadership, teamwork, and collaboration: The lived experience of conducting multisite research focused on quality and safety education for nurses competencies in academia. Nursing Education Perspectives (Wolters Kluwer Health), 42(2), 74–80. 10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, C. , Dash, D. , Mowbray, F. , Klea, L. , & Costa, A. (2021). A qualitative study of home care client and caregiver experiences with a complex cardio‐respiratory management model. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s12877-021-02251-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyman, C. C. , & Ozcetin, Y. S. (2021). “I wish I could have my leg”: A qualitative study on the experiences of individuals with lower limb amputation. Clinical Nursing Research, 31(3), 509–518. 10.1177/10547738211047711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speziale, H. S. , & Carpenter, D. R. (2011). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (5th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. https://go.exlibris.link/t59MntXL [Google Scholar]

- Spiegelberg, H. (1975). Doing phenomenology: Essays on and in phenomenology. Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- Stubblefield, C. , & Murray, R. L. (2002). A phenomenological framework for psychiatric nursing research. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 16(4), 149–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J. C. , Rei, W. , Chang, M. Y. , & Sheu, S. J. (2021). Care and management of stillborn babies from the parents' perspective: A phenomenological study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31, 860–868. 10.1111/jocn.15936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundler, A. J. , Lindberg, E. , Nilsson, C. , & Palmér, L. (2019). Qualitative thematic analysis based on descriptive phenomenology. Nursing Open, 6(3), 733–739. 10.1002/nop2.275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundler, A. J. , Råberus, A. , Carlsson, G. , Nilsson, C. , & Darcy, L. (2021). ‘Are they really allowed to treat me like that?’ A qualitative study to explore the nature of formal patient complaints about mental healthcare services in Sweden. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 31(2), 348–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Todres, L. (2005). Clarifying the life‐world: Descriptive phenomenology. In Holloway I. (Ed.), Qualitative research in health care (pp. 104–124). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C. , Lillie, E. , Zarin, W. , O'Brien, K. K. , Colquhoun, H. , Levac, D. , … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA‐ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vignato, J. , Tatano Beck, C. , Conley, V. , Inman, M. , Patsais, M. , & Segre, L. S. (2021). The lived experience of pain and depression symptoms during pregnancy. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing, 46(4), 198–204. 10.1097/NMC.0000000000000724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Essen, E. (2021). Young adults' transition to a plant‐based diet as a psychosomatic process: A psychoanalytically informed perspective. Appetite, 157, 105003. 10.1016/j.appet.2020.105003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, S. L. , Crist, J. D. , Shea, K. , Holland, S. , & Cacchione, P. Z. (2021). The lived experience of persons with malignant pleural mesothelioma in the United States. Cancer Nursing, 44(2), E90–e98. 10.1097/ncc.0000000000000770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis, D. G. , Sullivan‐Bolyai, S. , Knafl, K. , & Cohen, M. Z. (2016). Distinguishing features and similarities between descriptive phenomenological and qualitative description research. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38(9), 1185–1204. 10.1177/0193945916645499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojnar, D. M. , & Swanson, K. M. (2007). Phenomenology: An exploration. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 25(3), 172–180. 10.1177/0898010106295172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate, R. L. , Ateah, C. , & Secco, L. (2008). Living in a world of our own: The experience of parents who have a child with autism. Qualitative Health Research, 18(8), 1075–1083. 10.1177/1049732308320112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodley, L. K. , & Lewallen, L. P. (2021). Forging unique paths: The lived experience of Hispanic/Latino Baccalaureate Nursing students. Journal of Nursing Education, 60(1), 13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim, D. J. G. (2021). Self‐Management of Chronic Diseases: A descriptive phenomenological study. Social Work in Public Health, 36(2), 300–310. 10.1080/19371918.2020.1859034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, D. (2003). Husserl's phenomenology. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix

DataS 1

DataS 2

DataS 3

DataS 4

Data Availability Statement

Data available in article supplementary material