Abstract

PCR is the best method for the detection of enteric viruses present at low concentrations in environmental samples. However, some organic and inorganic compounds present in these samples can interfere in the reaction. Many of these substances are cytotoxic, too. The ZP60S filter membranes used in addition to fluorpentane treatment are quite efficient for virus concentration and simultaneous elimination of cytotoxicity from environmental samples. In this study, both procedures were used to promote the elimination of reverse transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) inhibitors from sewage and sewage-polluted creek water. Samples were subjected separately to each of the following procedures: filtration through electropositive filter membranes (ZP60S), organic extraction with Vertrel XF, and filtration through ZP60S followed by organic extraction. Afterwards, aliquots were experimentally inoculated with rotavirus SA-11 RNA and subjected to RT-seminested PCR for amplification of the VP7 gene. Results showed that the ZP60S membranes efficiently eliminated the RT-PCR inhibitors from water samples. The sample processing method was also applied to 31 in natura sewage and creek water samples for detection of naturally occurring rotavirus. A duplex seminested PCR was used for the quick detection of couples of the four rotavirus genotypes (G1 to G4). Eight samples (25.8%) were positive, and rotavirus sequences were not detected in 23 (74.2%). Results were confirmed by direct immunoperoxidase method. In summary, the use of electropositive filter membrane is appropriate for the elimination of substances that can interfere with RT-PCR, obviating additional sample purification methods.

Contamination of drinking water, recreational water, superficial water, and sewage effluent with enteric viruses is a great public health problem in developed and developing countries. These viruses represent a health risk because most of them remain infectious in the environment for long periods of time and can be transmitted by the fecal-oral route through consumption of contaminated water and food and because just a few viral particles are enough to begin a infection (10, 11, 25, 26).

Routine control of enteric viruses in water reservoirs, especially rotavirus and hepatitis A virus, is not usually performed in most countries, mainly due to the lack of suitable, fast, and sensitive viral concentration and/or detection procedures.

The virus adsorption-elution technique, developed in the 1970s, is still the most promising method for concentration of enteric viruses from water (4, 29, 30, 35). Positively charged filter membranes were successfully used for rotavirus concentration from sewage (18, 31), surface water (1), and drinking water (9, 32, 33), but those viruses were present in environmental samples at very low concentrations, probably as a result of the dilution of sewage after mixing with natural waters.

This fact highlights several difficulties in the detection of such viruses by methods that are routinely applied for clinical diagnostic purposes. These methods are usually not sensitive enough to detect low virus levels in environmental samples (2, 5, 31). Furthermore, many of these viral agents cannot be cultivated in cell cultures (3, 7).

Since 1990, PCR has become the best alternative for the detection of enteric viruses in environmental samples (1, 6, 8, 34). However, organic and inorganic compounds can inhibit both reverse transcriptases and Taq polymerases used in these reactions (1); proteins and carbohydrates can bind to nucleotides and magnesium ions, making them unavailable to the polymerase (27, 28). Several different methods have been used for the removal of these inhibitors, such as spin column chromatography, extraction with guanidine thiocyanate, and extraction with solvents (27, 28). Although these methods were successfully applied to the detection of enteric viruses by reverse transcriptase (RT)-PCR in different types of samples, such as drinking water, surface water, and shellfish, PCR was inhibited when applied to sewage and other high-solid fecal wastes (28). Also, the introduction of an extra step into the processing of environmental samples can lead to a greater loss of virus nucleic acids (23).

Since 1988-1989, we have been using an efficient two-step method for the concentration of rotavirus and other enteric viruses present in sewage and creek water, consisting of filtration with Zeta Plus 60S filter membranes (ZP60S) and ultracentrifugation (18). Fluorocarbon (Freon TF), formerly used for sample detoxification (15, 18, 21, 22), was recently replaced by Vertrel XF (Du Pont), which causes no ozone depletion and is still very efficient for the elimination of cytotoxicity (20). Considering the fact that most of the PCR inhibitors present in environmental samples are cytotoxic, the aim of this study was to determine if procedures used for the elimination of cytotoxic substances are also efficient for reducing the presence of such inhibitors, making additional DNA and RNA purification methods unnecessary.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Water samples.

Raw domestic sewage and sewage-polluted creek water were collected at two different sites in the city of São Paulo: Sewage Pumping Station Edu Chaves (SPS Edu Chaves) and Pirajussara Creek. Samples were collected at each location from a depth of approximately 50 cm in sterile 4-liter containers and transported back to the lab at room temperature for processing. To minimize the effects of diurnal variations, all samples were collected at the same place between 8 and 9 a.m. on weekdays.

On three different occasions, a sample of 4.5 liters was collected at each site for the RT-PCR inhibitor elimination assays. A volume of 4.1 liters of each sample was autoclaved at 121°C for 75 min at 1 atm above normal to inactivate naturally occurring rotaviruses. The remaining 400 ml of each sample was stored at 4°C for a maximum of 18 h and used in all assays without autoclaving.

The most efficient sample purification procedure experimentally established at present was applied to 18 4-liter water samples collected at SPS Edu Chaves and 13 samples collected at Pirajussara Creek for the detection of naturally occurring rotavirus.

Cell cultures and viruses.

MA-104 cells (an established monkey kidney cell line) were grown in Eagle's minimum essential medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Cultilab, Campinas, Brazil), 100 U of penicillin G/ml, and 100 μg of streptomycin/ml.

Simian rotavirus, strain SA-11 (genogroup G3), was propagated in MA-104 cells, and the number of focus-forming units (FFU) per 50 μl was determined by the direct immunoperoxidase (DIP) method, as previously described (18).

Human rotavirus strains Wa (genogroup G1), DS-1 (genogroup G2), and ST-3 (genogroup G4) were also grown on MA-104 cells and used as positive controls for the duplex seminested PCR (snPCR).

Sample processing for elimination of RT-PCR inhibitors.

Two steps, filtration through electropositive membranes (ZP60S; AMF Cuno Division, Meriden, Conn.) and extraction with Vertrel XF (1,1,1,2,3,4,4,5,5,5,5,5-decafluoropentane, catalog no. 138495-42-8; Du Pont Fluoroproducts, Wilmington, Del.), routinely performed during virus concentration and purification from raw sewage and surface water (19), were tested to determine their efficacy in eliminating PCR inhibitors. Autoclaved and nonautoclaved sewage and creek water samples were subjected to the following procedures: Vertrel XF extraction (method 1), filtration through electropositive filter membranes (method 2), and filtration through electropositive filter membranes followed by Vertrel XF extraction (method 3). In method 1, 500-μl aliquots of water were mixed with Vertrel XF, vortexed for 5 min, and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at room temperature. The aqueous phase was transferred to another tube and treated as before. In method 2, microporous and positively charged membranes, Zeta Plus 60S, were rinsed with 10 ml of distilled water/cm2 prior to use (24). Then, 50-ml autoclaved and nonautoclaved water samples were filtrated through a 65-cm2 membrane. In method 3, 500-μl aliquots of ZP60S filtrated water samples were subjected to Vertrel XF treatment as described previously. Further, 500-μl aliquots of the processed water samples were seeded with 104 FFU of rotavirus strain SA-11. Afterwards, viral RNA was extracted with the Trizol reagent (catalog no. 15596-018; Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md.) as recommended by the manufacturer and directly used for reverse transcription. Unseeded water samples and water treated with 0.01% diethyl pyrocarbonate (catalog no. D-5758; Sigma) were used as negative controls, and rotavirus-infected tissue culture fluid (104 FFU/50 μl) was used as a positive control. All samples were assayed in triplicate in independent experiments. Separate areas were used for reagents, sample processing, and manipulation of PCR products to reduce the risks of sample contamination.

RT-PCR.

Enzymatic reactions were performed in triplicate using 0.2-ml thin-walled tubes in a Gene Amp PCR system 2400 (Perkin Elmer) with specific primers as described by Gouveia et al. (12, 13) with minor modifications. For reverse transcription, a 10-μl aliquot of RNA extracted from water samples and rotavirus-infected cell cultures were initially denatured at 99°C for 5 min in the presence of 100 pmol of the primers Beg9 and End9. The mixture was then supplemented with 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 40 mM KCl, 3.0 mM MgCl2, 50 mM dithiothreitol, 500 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus RT (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies), yielding a final volume of 20 μl. Therefore, PCR for the full-length amplification of the gene encoding the VP7 protein of SA-11 rotavirus was carried out in 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 5-μl aliquot of cDNA, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 50 mM KCl, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM deoxynucleoside triphosphates, 2.5 U of Taq polymerase (Gibco-BRL/Life Technologies), and 100 pmol of the primers Beg9 and End9. A second round of amplification was performed using 2.0 μl of the first amplification product as a template and the primer pair End9 and aET3, specific for amplification of rotavirus G3 sequences (snPCR). Diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water samples were included as negative controls. The cycling conditions were as follows: initial heat denaturation at 94°C for 2 min; 30 cycles of template denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, primer annealing at 53°C for 2 min, and sequence extension at 72°C for 2 min; final extension at 72°C for 7 min. Amplification products were detected by 2.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml) staining. The detection limits of PCR and snPCR were determined based on virus recovery assays performed as described previously (19). Tenfold serial dilutions of these virus concentrates were subsequently subjected to both enzymatic reactions.

Detection of naturally occurring rotavirus in raw sewage and creek water samples by RT-duplex snPCR.

A total of 18 raw sewage and 13 polluted creek water samples were subjected to the two-step concentration method (20) and detoxified by Vertrel XF. The presence of naturally occurring rotavirus was detected by reverse transcription followed by a first round of amplification using the primers Beg9 and End9 as described above. A duplex snPCR (RT-duplex snPCR) was standardized for the simultaneous detection of rotavirus genogroups G1-G2 and G3-G4. The primer End9 (200 pmol) was used in each reaction in conjunction with 100 pmol of the group-specific primers aBT1 (WA; G1) plus aCT2 (DS-1; G2) and aET3 (SA-11; G3) plus aDT4 (ST-3; G4). The conditions described above for snPCR were maintained.

Water samples that did not show amplification of naturally occurring rotavirus were inoculated with 5 μl of SA-11 RNA, corresponding to 103 FFU, and reamplified by RT-PCR and duplex snPCR to exclude the interference of unspecific inhibitors in the enzymatic reaction. Samples were also inoculated onto MA104 cell monolayers for rotavirus detection by the DIP method.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Before the introduction of PCR for virus detection in our studies, some of the commonly used sample purification methods were tested, but the results were not promising due to a great loss of virus particles and/or nucleic acids (data not shown). In view of the efficient elimination of cytotoxic substances present in environmental samples by the sample processing method adopted in our laboratory, tests were carried out to check the elimination of PCR inhibitors at each step.

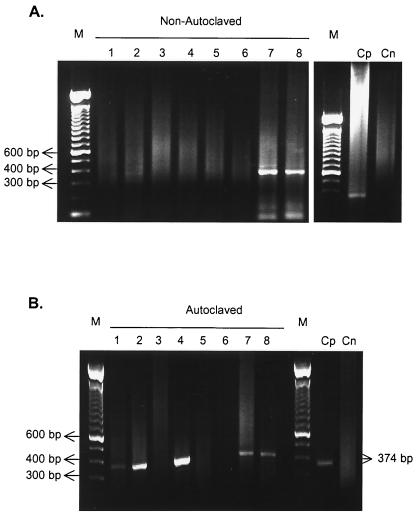

Autoclaved and nonautoclaved water samples were subjected to each method and then inoculated with rotavirus particles for RT-PCR amplification. The effect of RT-PCR inhibitors present in raw sewage was observed with the sample collected on 17 June 1998 before autoclaving (Table 1; Fig. 1A). The 374-bp fragment corresponding to the rotavirus gene was not amplified, even after Vertrel XF treatment only (Fig. 1A, lane 4). However, the fragment was detected in the samples purified by filtration through ZP60S filtration alone and ZP60S filtration in combination with Vertrel XF treatment (Fig. 1, lanes 7 and 8).

TABLE 1.

Results of RT-PCR inhibitor elimination assays performed with raw sewage and sewage-polluted creek water samples

| Sampling

|

Result of snPCR ofa:

|

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Date (mo/day/yr) | Autoclaving | In natura water

|

Water purified by:

|

||||||

| Vertrel XF

|

ZP60S filtration

|

ZP60S filtration + Vertrel XF

|

||||||||

| NS | S | NS | S | NS | S | NS | S | |||

| Creek | 1/27/98 | No | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Yes | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | ||

| 1/28/98 | No | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| Yes | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | ||

| 2/02/98 | No | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | |

| Yes | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | ||

| Sewage | 6/03/98 | No | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Yes | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | ||

| 6/17/98 | No | − | − | − | − | − | + | − | + | |

| Yes | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | ||

| 6/24/98 | No | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | |

| Yes | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + | ||

Rotavirus gene amplification. +, detected (absence of inhibitors); −, none detected. NS, samples were not seeded with rotavirus SA-11; S, samples were seeded with rotavirus SA-11.

FIG. 1.

Results of snPCR of in natura sewage water collected on 17 June 1998. Nonautoclaved (A) and autoclaved (B) samples were subjected to different purification methods. Lanes: 1, in natura water; 2, in natura water plus rotavirus; 3, water treated with Vertrel XF; 4, water treated with Vertrel XF plus rotavirus; 5, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes; 6, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes and treated with Vertrel XF; 7, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes plus rotavirus; 8, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes and treated with Vertrel XF plus rotavirus. Cp and Cn, positive and negative controls; M, molecular size marker (100-bp DNA ladder).

The other two in natura sewage samples, collected on 3 and 24 June 1998, did not show this inhibitory effect on RT-snPCR, and the seeded rotavirus could be detected in both samples before and after treatment by the three purification methods (Table 1).

On the other hand, genomic amplification of seeded rotaviruses were observed in all creek water samples, even in those that were not subjected to any treatment (Table 1; Fig. 2). However, filtration of some samples through ZP60S membranes minimized the smear and nonspecific products obtained after RT-PCR amplification. This result was not observed by using Vertrel XF only (Fig. 2). The use of Trizol did not improved the sample purification process (data not shown). The autoclaving of some samples, necessary for the virus recovery assays, contributed to the reduction of RT-snPCR inhibitors and smears in some cases (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4). Temperature influence on RT-PCR inhibitors should not be considered in this case, and to exclude this interference, nonautoclaved samples were pair tested. The results obtained by using ZP60S membranes contradict the reports by Kopecka et al. (16) and Abbaszadegan et al. (1). Both studies reported a high rate of inhibition of RT-PCR after concentration of surface water samples on electropositive filters. Recently, our group observed that the electropositive filter membranes (ZP60S) release cytotoxic residues during the sample filtration procedure, although this problem was overcome by rinsing the membrane with distilled water before use, eliminating the cytotoxic substances from the membrane matrix (24). Probably the PCR inhibitors, such as humic substances and other organic and inorganic compounds (1, 16), were eliminated, contributing to the good results obtained with our method.

FIG. 2.

Results of snPCR of in natura creek water collected on 28 January 1998. Nonautoclaved (A) and autoclaved (B) samples were subjected to different purification methods. Lanes: 1, in natura water; 2, in natura water plus rotavirus; 3, water treated with Vertrel XF; 4, water treated with Vertrel XF plus rotavirus; 5, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes; 6, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes and treated with Vertrel XF; 7, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes plus rotavirus; 8, water filtrated through ZP60S membranes and treated with Vertrel XF plus rotavirus. Cp and Cn, positive and negative controls; M, molecular size marker (100-bp DNA ladder).

It was possible to detect naturally occurring rotavirus in some autoclaved samples used in the RT-PCR inhibitor elimination assays (Table 1; Fig. 1A, lane 1). Despite previous studies which demonstrated that this exposure time is efficient for rotavirus inactivation (23), viral RNA probably resisted these autoclaving conditions (36). The hypothesis of cross-contamination was refuted due to the absence of rotavirus-specific fragments in the negative control samples.

The detection by RT-snPCR of rotaviruses experimentally seeded in raw sewage and polluted creek water samples (data not shown) indicated that the use of ZP60S in combination with Vertrel XF is a good method for obtaining highly purified virus concentrates from environmental samples, suitable for RT-PCR without the introduction of extra purification steps.

In order to test the feasibility of the concentration and purification method described above for the detection of rotaviruses present in sewage and creek water samples, RT-snPCR was performed. Specific primers for human genogroups G1 to G4 were used, because those are the most frequently associated with diarrhea cases in humans (13). The detection limit of the RT-PCR was 103 FFU, and that of the snPCR was 101 FFU. Multiplex snPCRs using G1 to G4 primers were tested for a quick detection of such rotaviruses but failed (data not shown). These results are in agreement with those of Tsai et al. (34), who have shown this limitation when one template is present at a higher concentration than the others.

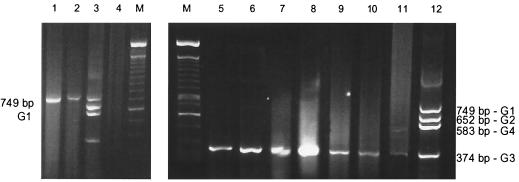

Thus, a duplex snPCR was standardized, and the combination of primer pairs aBT1-aCT2 and aET3-aDT4 was very efficient for the simultaneous detection of the genogroups G1-G2 and G3-G4, respectively. A mixture of the two products is shown in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Detection of naturally occurring rotavirus in sewage and creek water by the two-step concentration method and duplex snPCR. Lanes: 5, 6, 7, 9, and 11, sewage water samples; 2, 8, and 10, creek water samples; 1, positive control; 3 and 12, mixture of positive controls for rotavirus genogroups G1 to G4. M, molecular size marker (100-bp DNA ladder).

By using this method, naturally occurring rotaviruses were detected in 8 (25.8%) samples out of 31 examined (Fig. 3). Five (27.7%) sewage and three (23.1%) creek water samples were positive with primers for rotavirus groups G1 to G4. The presence of rotavirus in these samples was confirmed by the DIP method. However, six samples that were positive by the DIP method did not show amplification of rotavirus-specific fragments, probably because these rotaviruses belong to other genogroups, like G5 and G9, which are frequently involved in human gastroenteritis in Brazil (14, 17). The interference of RT-PCR inhibitors in those enzymatic reactions was excluded due to the amplification of viral RNA experimentally inoculated into them.

Rotavirus was not detected in 23 (74.2%) samples by both methods.

Despite the apparent low efficiency of RT-snPCR in comparison to the DIP method, used at present as a confirmatory test, it should be considered that many rotaviruses, especially those of human origin, are not cultivable in cells and that the choice of RT-PCR as a detection method is highly recommended.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant 97/3751-2 and a fellowship awarded to A. P. S. Queiroz (97/11308-1) by Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP).

We thank C. R. M. Barardi, M. L. B. O. Rácz, and V. Munford for human strains of rotavirus and for valuable assistance with the RT-PCR system, J. M. G. Candeias for providing the antirotavirus serum conjugate, and Beny Spira for critical review of the manuscript. We are grateful to Agustin Gonzales and collaborators (Companhia de Saneamento Básico do Estado de S. Paulo [SABESP]) for access to the SPS Edu Chaves facility.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbaszadegan M, Huber M S, Gerba C P, Pepper I L. Detection of enteroviruses in groundwater with the polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1318–1324. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1318-1324.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agbalika F, Wullenweber M, Prevot J. Preliminary evaluation of the ELISA as a tool for the detection of rotavirus in activated sewage sludge. Zentbl Bakteriol Hyg I. 1985;180:534–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allard A, Girones R, Juto R, Wadell G. Polymerase chain reaction for detection of adenoviruses in stool samples. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2659–2667. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.12.2659-2667.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clesceri L S, Greenberg A E, Eaton A D, editors. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 20th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dahling D R, Wright B A, Williams F P. Detection of viruses in environmental samples: suitability of commercial rotavirus and adenovirus test kits. J Virol Methods. 1993;45:137–147. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(93)90098-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubois E, Le Guyader F, Haugarreau L, Kopecka H, Cormier M, Pommepuy M. Molecular epidemiological survey of rotaviruses in sewage by reverse transcriptase seminested PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism assay. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1794–1800. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.1794-1800.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estes M K, Palmer E L, Obijeski J F. Rotavirus: a review. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1981;105:123–184. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-69159-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gajardo R, Bouchriti N, Pintó R M, Bosch A. Genotyping of rotaviruses isolated from sewage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:3460–3462. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.9.3460-3462.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gerba C P, Keswick B H, DuPont H L, Fields H A. Isolation of rotavirus and hepatitis A from drinking water. Monogr Virol. 1984;15:119–125. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerba C P, Rose J B, Haas C N, Crabtree K D. Waterborne rotavirus: a risk assessment. Water Res. 1996;30:2929–2940. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilgen M, Germann D, Luthy J, Hübner P H. Three-step isolation method for sensitive detection of enterovirus, rotavirus, hepatitis A virus, and small round structured viruses in water samples. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;37:189–199. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)00075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gouveia V. PCR detection of rotavirus. In: Persing D H, editor. Diagnostic molecular microbiology: principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. pp. 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gouveia V, Glass R I, Woods P, Taniguchi K, Clark H F, Forrester B, Fang Z Y. Polymerase chain reaction amplification and typing of rotavirus nucleic acid from stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:276–282. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.2.276-282.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gouveia V, Castro L, Timenetsky M C, Greenberg H, Santos N. Rotavirus serotype G5 associated with diarrhoea in Brazilian children. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1408–1409. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1408-1409.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hejkal T W, Gerba C P, Rao V C. Reduction of cytotoxicity in virus concentrates from environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:731–733. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.3.731-733.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kopecka H, Dubrou S, Prevot J, Marechal J, López-Pila J M. Detection of naturally occurring enteroviruses in waters by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction and hybridization. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1213–1219. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1213-1219.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leite J P G, Alfieri A A, Woods P A, Glass R I, Gentsch J R. Rotavirus G and P types circulating in Brazil: characterization by RT-PCR, probe hybridization, and sequence analysis. Arch Virol. 1996;141:2365–2374. doi: 10.1007/BF01718637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehnert D U, Stewien K E. Detection and distribution of rotavirus in raw sewage and creeks in São Paulo, Brazil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:140–143. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.1.140-143.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mehnert D U, Stewien K E, Hársi C M, Queiroz A P S, Candeias J M G, Candeias J A N. Detection of rotavirus in sewage and creek water: efficiency of the concentration method. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92:97–100. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02761997000100020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mendez I I, Hermann L L, Hazelton P R, Coombs K M. A comparative analysis of Freon substitutes in the purification of reovirus and calicivirus. J Virol Methods. 2000;90:59–67. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(00)00217-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mix T. The physical chemistry of membrane interactions. Dev Ind Microbiol. 1974;15:135–142. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Payment P, Ayache R, Trudel M. A survey of enteric viruses in domestic sewage. Can J Microbiol. 1983;29:111–119. doi: 10.1139/m83-018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Queiroz A P S. M.Sc. thesis. São Paulo, Brazil: University of São Paulo; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Queiroz A P S, Hársi C M, Santos F M, Candeias J M G, Monezi T A, Mehnert D U. Factors that can interfere in virus concentration by using Zeta Plus 60S filter membranes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2000;95:713–716. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762000000500018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose J B, Gerba P C. Assessing potential health risks from viruses and parasites in reclaimed water in Arizona and Florida, USA. Water Sci Technol. 1991;23:2091–2098. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiff G M, Stefanovic G M, Young B, Pennekamp J K. Minimum human infectious dose of enteric virus (Echovirus-12) in drinking water. Monogr Virol. 1984;15:222–228. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwabb K J, De Leon R, Sobsey M D. Concentration and purification of beef extract mock eluates from water samples for the detection of enteroviruses, hepatitis A and Norwalk virus by reverse transcription-PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:531–537. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.531-537.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shieh Y S C, Wait D, Tai L, Sobsey M D. Methods to remove inhibitors in sewage and other fecal wastes for enterovirus detection by the polymerase chain reaction. J Virol Methods. 1995;54:51–66. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(95)00025-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith E M, Gerba C P. Development of a method for detection of human rotavirus in water and sewage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;43:1440–1450. doi: 10.1128/aem.43.6.1440-1450.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sobsey M D, Jones B L. Concentration of poliovirus from tap water using positively charged microporous filters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1979;37:588–595. doi: 10.1128/aem.37.3.588-595.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Steinmann J. Detection of rotavirus in sewage. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:1043–1045. doi: 10.1128/aem.41.4.1043-1045.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toranzos G A, Gerba C P, Hansen G. Enteric viruses and coliphages in Latin America. Toxic Assess. 1988;3:491–510. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toranzos G A, Hansen G, Gerba C P. Occurrence of enteroviruses and rotaviruses in drinking water in Colombia. Water Res. 1986;18:109–114. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsai Y, Tran B, Sangermano L R, Palmer C J. Detection of poliovirus, hepatitis A virus and rotavirus from sewage and ocean water by triplex reverse transcriptase PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2400–2407. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2400-2407.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wallis C, Henderson M, Melnick J L. Enterovirus concentration on cellulose membranes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1972;23:476–480. doi: 10.1128/am.23.3.476-480.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watson J D, Hopkins N H, Roberts J W, Seitz K A, Weiner A M. The origins of life. In: Watson J D, Hopkins N H, Roberts J W, Seitz K A, Weiner A M, editors. Molecular biology of the gene. 4th ed. Menlo Park, Calif: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishers; 1988. pp. 1097–1161. [Google Scholar]