Abstract

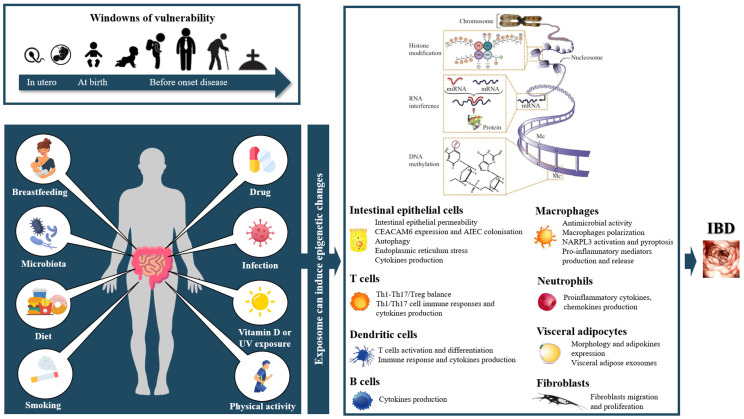

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract that encompass two main phenotypes, namely Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. These conditions occur in genetically predisposed individuals in response to environmental factors. Epigenetics, acting by DNA methylation, post-translational histones modifications or by non-coding RNAs, could explain how the exposome (or all environmental influences over the life course, from conception to death) could influence the gene expression to contribute to intestinal inflammation. We performed a scoping search using Medline to identify all the elements of the exposome that may play a role in intestinal inflammation through epigenetic modifications, as well as the underlying mechanisms. The environmental factors epigenetically influencing the occurrence of intestinal inflammation are the maternal lifestyle (mainly diet, the occurrence of infection during pregnancy and smoking); breastfeeding; microbiota; diet (including a low-fiber diet, high-fat diet and deficiency in micronutrients); smoking habits, vitamin D and drugs (e.g., IBD treatments, antibiotics and probiotics). Influenced by both microbiota and diet, short-chain fatty acids are gut microbiota-derived metabolites resulting from the anaerobic fermentation of non-digestible dietary fibers, playing an epigenetically mediated role in the integrity of the epithelial barrier and in the defense against invading microorganisms. Although the impact of some environmental factors has been identified, the exposome-induced epimutations in IBD remain a largely underexplored field. How these environmental exposures induce epigenetic modifications (in terms of duration, frequency and the timing at which they occur) and how other environmental factors associated with IBD modulate epigenetics deserve to be further investigated.

Keywords: inflammatory bowel disease, epigenetics, exposome

1. Introduction

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic relapsing-remitting inflammatory disorders of the gastrointestinal tract encompassing two main phenotypes: Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). The pathogenesis of IBD is not fully understood to date, but the most commonly accepted hypothesis is an inappropriate gut mucosal immune response towards the constituents of the gut microbiota, which cross an impaired epithelial barrier, in genetically predisposed individuals and under the influence of environmental factors [1]. Epidemiological studies (such as those carried out on monozygotic twins [2] and immigrants [3]), as well as the increase over time of the CD and UC incidence and prevalence (while the human gene pool is the same as before) [4], are all arguments that emphasize the importance of environmental factors in the occurrence of these inflammatory diseases. Epigenetics is a branch of life science that studies mechanisms regulating DNA-dependent processes (e.g., transcription, replication, recombination, repair, etc.) without primarily involving the nucleotide sequence of the DNA but, rather, the structure of how DNA is packed in the cell nucleus (chromatin structure), which can be inherited by daughter cells after cell division. Epigenetic mechanisms, including DNA methylation, post-translational histones modifications and non-coding ribonucleic acids (ncRNAs) [5], [6], regulating gene expression provide plausible explanations for the influence of the environment on gene expression profiles that favor intestinal inflammation [7]. Supporting this line of ideas, DNA methylation profiles observed in older monozygous twins with different environmental histories shows that epigenetic imprinting occurs mainly during crucial periods of development, whereas epigenomic changes can also occur day after day and accumulate over time in response to the exposome [8,9,10].

The term exposome has been proposed to encompass all environmental influences over the life course, from conception to death, that may influence disease emergence and clinical outcomes [11,12]. External environmental factors influencing the occurrence of IBD include the maternal lifestyle and in utero events [13], breastfeeding [14], diet [7], smoking habits [15,16], drugs [16,17,18], physical activity [16], stress [19], appendicectomy [16], vitamin D/UV exposure [16], infections [20] and hygiene [21]. While it is possible that these different factors directly induce epigenetic changes in the host, it is also possible that they influence the microbiome, an internal component of the exposome, and contribute to the occurrence of IBD through the exposome–microbiome–epigenome axis [22].

The impact of exposomes on the epigenetics in IBD has been poorly studied and is probably underestimated. This review aims to identify all the elements of the exposome that may play a role in intestinal inflammation through epigenetic modifications, as well as the underlying mechanisms that may contribute to IBD pathophysiology.

2. Epigenetics in IBD

Epigenetic mechanisms of gene expressions are involved in the intestinal epithelium homeostasis and in the development and differentiation of the immune cells, as well as in the modulation of responses generated by the immune system to defend against potential pathogens [23]. These epigenetic changes are reversible [24]. The genomic DNA in the eukaryotic cell nucleus is organized into chromatin. Chromatin consists of nucleic acids (genomic DNA and different types of RNAs); histone proteins (H2A, H2B, H3, H4 and H1) and non-histone chromatin-associated proteins [5,25,26]. Nucleosomes constitute the functional and structural units of chromatin. A nucleosome is built by around 146 bp of genomic DNA surrounding a histone octamer, which consists of two H2A–H2B dimers and one (H3–H4)2 tetramer [27,28]. In other words, chromatin is the physiological template for all DNA-dependent biological processes, including transcription. This fact increases the complexity of transcription regulation, since it implies that the chromatin structure has to be dynamic to grant or block access of transcription regulators to their respective binding elements on the DNA and to the transcription machinery to the genomic information in the nucleotide sequence. The epigenetic mechanisms of transcriptional regulation involve DNA methylation, histone modifications, nucleosome remodeling, interaction with the nuclear matrix and regulation via long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) and micro RNAs (miR) [26,29,30,31]. These mechanisms of transcription regulation establish cell-specific, heritable patterns of differential gene expression and silencing from the same genome and allow the cells to change these gene expression signatures in response to stimuli, such as changing conditions due to their environment [32,33].

DNA methylation in eukaryotes refers to the covalent transfer of a methyl group (-CH3) to the carbon atom at position 5 of cytosine forming 5-methylcytosine (5mC), most frequently at the dinucleotide sequence CG (mCG) [31,34,35,36,37]. DNA regions that are ≥200 bp long and show a CG:GC ratio ≥ 0.6 are defined as a CpG island [38]. The presence of DNA methylation prevents transcription factors from reaching gene promoters and generally leads to gene silencing [39,40]. DNA methylation in eukaryotes is catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs): DNMT1, which maintains DNA methylation patterns (during DNA replication and cell division), and DNMT3A/3B, which are responsible for de novo methylating DNMTs (during development or differentiation) [41,42,43]. These enzymes transfer methyl groups from S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAM) to the cytosine residues in DNA [44]. On the contrary, DNA demethylation is mediated by the ten-eleven translocation (TET) enzymes, which add a hydroxyl group onto the methyl group of 5mC to form 5hmC (5-hydroxymethyl cytosine) [45]. Compared to healthy subjects, IBD patients show DNA methylation changes both at the cell (mainly immune) level and at the tissue level [46,47,48,49,50,51,52]. These changes also differ between UC and CD patients and involve several loci responsible for the regulation of immune responses [46,47,48,49,50,51,52].

Another epigenetic mechanism of transcriptional regulation involves post-translational modifications of histone proteins (further referred to as histone modifications). Histone proteins (H1, H2A, H2B H3 and H4) are relatively small and basic proteins that are abundant in the cell nucleus and are an essential part of the nucleosome, as described above. Due to structural characteristics of the nucleosome, histone proteins can undergo post-translational modifications at their N-terminal tails, which include acetylation, methylation, phosphorylation, ubiquitination and sumoylation, among others [53,54,55,56]. While DNA methylation is relatively stable in somatic cells, histone modifications are more diverse and dynamic, changing rapidly during the course of the cell cycle [6,30,53,54]. Acetylation at specific amino acids of histones (e.g., histone 3 lysine 9 acetylation; H3K9Ac) is generally associated with active chromatin and is mediated by histone acetyltransferases (HAT) and removed by histone deacetylases (HDAC). Histone methylation also occurs at specific amino acids of histone proteins and can be associated with both the repression (e.g., H3 lysine 27 trimethylation; H3K27me3) and activation (e.g., H3 lysine 4 trimethylation; H3K4me3) of gene expressions. There is a variety of enzymes mediating histone methylation (histone methyltransferases; HMT) and histone demethylation [57,58]. Similarly, the reactions leading to other histone modifications are catalyzed by a broad spectrum of enzymes in a regulated manner. Several environmental agents induce changes in histone modifications, thereby leading to changes in gene expression signatures.

In addition to these mechanisms, epigenetic regulation can also involve ncRNA, which are RNAs not translated into proteins, including miRs and lncRNAs. If miRs have a length of 18–25 nucleotides, lncRNAs are over 200 bases long [59]. These nucleic acid molecules can regulate gene expressions by interfering with messenger RNA (mRNA) translations by degrading them or through interactions with protein complexes involved in the regulation of gene expression [59,60]. The ncRNAs are differentially expressed between the control and IBD subjects, and there is also a difference in expression between CD and UC patients [61,62,63]. In IBD, miRs are involved in the regulation of the intestinal mucosal barrier, T-cell differentiation, the Th17 signaling pathway and autophagy [63]. In UC patients, miR-21, miR-16 and let-7 expressions are significantly increased in inflamed mucosa, while miR-192, miR-375 and miR-422b expressions are significantly reduced [61]. In CD patients, miR-23b, miR-106 and miR-191 are significantly increased in the inflamed mucosa, while miR-19b and miR-629 expressions are significantly decreased [61].

All these epigenetic mechanisms contribute to the development, progression and maintenance of IBD. They are usually triggered by a range of environmental factors. Some authors have mentioned three critical periods during which the environment can favor the onset of the disease: (1) during the prenatal period (in response to the maternal lifestyle), (2) in the early postnatal period (during gut microbiota colonization) and (3) just before the disease onset [64]. This review aims to study the impact of the exposome on the epigenome in IBD.

3. Methods

To identify exposome elements that could impact the epigenetics of IBD, we performed a scoping search using Medline. We used the following Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms (‘epigenetics’ OR ‘epigenomics’ OR ‘DNA methylation’ OR ‘histone(s)’ OR ‘short noncoding RNA’ OR ‘long noncoding RNAs’ OR ‘microRNA’ OR ‘miR’ OR “miRNA”) AND (“Inflammatory bowel disease” OR “IBD” OR “intestinal inflammation” OR “Crohn’s disease” OR “ulcerative colitis” OR “colitis”). Secondary references of the retrieved articles were reviewed to identify publications not captured by the electronic search. We excluded articles not written in English and those related to colitis-associated cancer.

4. Results

4.1. Parental Exposition

Accumulating evidence has pointed out that in utero environmental exposure can influence the epigenetic programming of the offspring and have an impact on its fate, conditioning its health status or, on the contrary, its lifelong risk of inflammatory conditions [65,66,67,68]. This is explained by the fact that the occurrence of an epimutation in a stem cell during embryonic development is transmitted to all their daughter cells and affects many more cells than those occurring in adult stem and/or somatic cells during postnatal development [69]. These epigenetic changes can not only be transmitted during successive division but also are passed on from generation to generation, some authors mentioning a real transgenerational epigenetic inheritance [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80]. These prenatal environmental induced-epigenetic modifications could therefore contribute to the IBD epidemic not only by contributing to this condition but also by passing on modifications to subsequent generations, contributing to familial IBD predisposition, as illustrated by immigration studies [64,81,82,83,84,85].

There are few data on prenatal epigenetic plasticity in response to the environment in intestinal inflammation [64]. Some data suggest that this epigenomic reprogramming occurs in response to maternal diet modifications, and an excess of prenatal micronutrients (i.e., methyl donors routinely incorporated into prenatal supplements, such as folate, methionine, betaine and vitamin B12) in the maternal diet could confer an increased risk of colitis in the offspring [73]. The occurrence of maternal infection during pregnancy could also lead to the production of IL-6, known to induce epigenetic changes in fetal intestinal epithelial stem cells, which could induce long-lasting impacts on intestinal immune homeostasis and a predisposition toward inflammatory disorders [86]. In addition to diet and infections, maternal smoking during pregnancy could also have an impact on the risk of developing IBD [87]. A study of the impact of prenatal maternal smoking on the offspring’s DNA methylation has made it possible to highlight 69 differentially methylated CpGs in 36 genomic regions, among which four CpG sites were associated with an increased risk of IBD [87]. Maternal smoking induced persistent alterations in DNA methylation (rather, global hypomethylation [88,89,90,91,92]) but also miR dysregulation in the exposed offspring, changes that can be transmitted to the next generation [90,93,94,95,96,97,98]. Taken together, these data suggest that these maternal influences during prenatal development can induce epigenetic changes in the offspring, sometimes considered by some authors as the first step towards IBD development (by introducing a permanent change in the disease-relevant cell types) [64,99,100].

4.2. Microbiota

Occurring in this predisposing environment, a microorganism’s gut colonization during the first hours of life can be considered as the second step toward the occurrence of IBD [64,99,100]. Influenced by the mode of delivery, the presence or absence of breastfeeding and early environmental exposure, the early-life gut microbiota sets trajectories for health or IBD [101,102]. This newly formed microbiome will modulate until the age of 3 years to reach a globally largely similar taxonomic composition as in adults and will act as an epigenetic modulator, modifying the epimutations induced in the prenatal period. Breastfeeding and early bacterial colonization appear to play an important role in DNA methylation in intestinal epithelial stem cells and to condition the lifelong gut health [103].

The microbiome can induce epigenetic changes both in the intestinal epithelium and in immune cells (Table 1). Comparing the epigenomes of germ-free mice or antibiotic-treated mice to conventional mice, it appears that this microbiome can influence the host epigenetics through changes in DNA methylation, histone modifications and, also, through ncRNAs [104,105,106,107,108]. Species belonging to Firmicutes (especially Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Roseburia species [109]) and Bacteroides genera, known to be reduced in IBD [110], have an epigenetically mediated anti-inflammatory action (HDAC inhibition) via the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) (the role of these will be discussed in more detail below) [111]. The commensal flora can also affect the bioavailability of methyl groups through their production of folate and affects the host DNA methylation [112,113].

Table 1.

Impact of the microbiota on the epigenome in intestinal inflammation. AIEC, adherent-invasive Escherichia coli; CpG, cytosine–phosphate–guanine; DCs, dendritic cells; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; ETBF, Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis; HDAC, histone deacetylases; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; IL, interleukin; KO, knockout; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; lncRNAs, long non-coding RNAs; MAP, Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis; miR, micro-RNA; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; NOD2, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNBS, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid; UC, ulcerative colitis; WT, wild-type; ↑, increase; ↓ decrease.

| Germ | Activity | Epigenetic Mechanism | Tissue/Cells | Mechanism | Model | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commensal bacteria | ||||||

| Commensal bacteria | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-10a | DCs | Negatively regulates host miR-10a expression, which contribute to the intestinal homeostasis maintenance by targeting IL-12/IL-23p40 expression | C57BL/6 (B6) mice | Xue X, et al. (2011) [125] |

| Commensal flora | Proinflammatory activity | miR-107 | DCs and macrophages | Downregulates miR-107 expression, known to represses the expression of IL-23p19, thereby favouring IL-23 expression | IECs, lamina propria CD11c+ myeloid cells including dendritic cells and macrophages, and T cells; DSS-induced colitis in mice | Xue X, et al. (2014) [126] |

| Commensal bacteria | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-10a | DCs | Inhibits human DCs miR-10a expression, which downregulates mucosal inflammatory response through inhibition of IL-12/IL-23p40 and NOD2 expression, and blockade of Th1/Th17 cell immune responses | Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells | Wu W, et al. (2015) [127] |

| Commensal microbiome-dependent (Bacteroides acidifaciens and Lactobacillus johnsonii | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-21-5p | IECs | Commensal microbiome-dependent miR-21-5p expression in IECs regulates intestinal epithelial permeability via ADP Ribosylation Factor 4 (ARF4) | HT-29 and Caco-2 cells | Nakata K., et al. (2017) [128] |

| Cluster(s) | ||||||

| ↓ of Bacteroidetes and ↑ of protective Firmicutes and Clostridia | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-21 | Colonic mucosae | Leads to miR-21 reduction, known to influence the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation by causing propagation of a disrupted gut microbiota | WT and miR-21−/− mice | Johnston DGW, et al. (2018) [129] |

| Cluster enriched in Bacteroides fragilis | - | DNA methylation | Intestinal mucosa | Induces 33 and 19 significantly hyper-methylated or hypomethylated sites, including hyper-methylated signals in the gene body of Notch Receptor 4 (NOTCH4) | 50 CD; 80 UC; 31 controls | Ryan FJ, et al. (2020) [130] |

| Cluster enriched in Escherichia/Shigella/Klebsiella and Ruminococcus gnavus | Proinflammatory activity | DNA methylation | Intestinal mucosa | Larger number of differentially methylated CpG sites (131 hyper- and 475 hypomethylated), including hypomethylation in CCDC88B (recently correlated with risk of CD) and Transporter 2 (TAP2), involved in genetic heterogeneity of CD | ||

| Cluster enriched in B. vulgatus | - | DNA methylation | Intestinal mucosa | Induces 23 hyper- and 18 hypomethylated sites, significant hyper-methylation was observed in the gene body of DNA Damage Regulated Autophagy Modulator 1 (DRAM1) | ||

| Specific germ | ||||||

| Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC) | Proinflammatory activity | miR-30c and miR-130a | IECs | Upregulates levels of miR-30c and miR-130a in IECs (by activating NF-κB), reducing the levels of ATG5 and ATG16L1 and inhibiting autophagy, leading to increased numbers of intracellular AIEC and an increased inflammatory response | Cultured IECs and mouse enterocytes | Nguyen HT, et al. (2014) [115] |

| AIEC | Proinflammatory activity | let-7b | IECs | Instigates excessive mucosal immune response against gut microbiota via miR let-7b/TLR4 signaling pathway | WT and IL-10 KO mice; T84 cells | Guo Z, et al. (2018) [117] |

| AIEC | Proinflammatory activity | miR-30c and miR-130a | IECs | AIEC-infected IECs secretes exosomes that can transfer specific miRs (miR-30c and miR-130a) to recipient IECs, inhibiting autophagy-mediated clearance of intracellular AIEC | T84 cells | Larabi A, et al. (2020) [116] |

| Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) | Proinflammatory activity | miR-21 | Macrophages | MAP upregulates miR-21 in macrophages, a change that results in diminished macrophages clearance ability and favours pathogens survival within the cells | THP-1 cells | Mostoufi-Afshar S, et al. (2018) [119] |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-146a and miR-155 | DCs | Induces a significant downregulation of miR-146a expression, a negative regulator of immune response, and upupregulation of on miR-155 | Cultured DCs | Giahi L., et al. (2012) |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus | Anti-inflammatory activity | miRs | Colonic mucosae | L. acidophilus induce miRs expression | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Kim WK, et al. (2021) [131] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC1 inhibition | T cells | Inhibits HDAC1, promotes Foxp3 and blocks the IL-6/STAT3/IL-17 downstream pathway contributing to the maintain of Th17/Treg balance | IBD patients (n = 9) and healthy control (n = 6); DSS-induced colitis in mice | Zhou L, et al. (2018) [132] |

| Faecalibacterium prausnitzii | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC3 inhibition | T cells | Produces butyrate to decrease Th17 differentiation and attenuate colitis through inhibiting HDAC3 and c-Myc-related metabolism in T cells | IBD patients; TNBS-induced colitis in mice | Zhang M, et al. (2019) [133] |

| Trichinella spiralis | Anti-inflammatory activity | miRs | T cells | Extra-vesicles-derived miR are involved in the regulation of the host immune response, including inflammation, including increase of Th2 and Treg cells | TNBS-induced colitis in mice | Yang Y, et al. (2020) [134] |

| Enterotoxigenic Bacteroides fragilis (ETBF) | Proinflammatory activity | miR-149-3p | T cells | Downregulates miR-149-3p, which play a role in modulation of T-helper type 17 cell differentiation (with increased number of T-helper type 17 cell contributing to intestinal inflammation) | ETBF cells | Cao Y, et al. (2021) [135] |

| Bacterial component | ||||||

| Roseburia intestinalis-derived flagellin | Anti-inflammatory activity | lncRNA | IECs | Flagellin induces p38-stat1 activation, activated HIF1A-AS2 promotor, induced HIF1A-AS2 (a lncRNA) expression in gut epithelium in a dose- and time-dependent manner. HIF1A-AS2 inactivates NF-κB/Jnk pathway and thus inhibits inflammatory responses | DSS/Flagellin-challenged mice; Caco-2 cells | Quan Y, et al. (2018) [124] |

| Roseburia intestinalis-derived flagellin | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-223-3p | Macrophages | Flagellin inhibited activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and pyroptosis via miR-223-3p/NLRP3 signaling in macrophages | DSS-induced colitis model in C57Bl/6 mice and the LPS/ATP-induced THP-1 macrophages | Wu X, et al. (2020) [123] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac histone | Macrophages | Increases H3K4me1, H3K4me3, and H3K27ac histone marks, particularly in genes associated with an inflammatory response such as IL-12a and IL-18 | IL-10-deficient (Il10(−/−)) mice | Simon JM, et al. (2016) [136] |

| LPS and flagellin | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-146 | IECs | Stimulate miR-146a overexpression in IECs, induces immune tolerance, inhibiting cytokine production (MCP-1 and GROα/IL-8) | TNBS and DSS-induced colitis in mice | Anzola A, et al. (2018) [137] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | lncRNA H19 | IECs | Increases levels of H19 lncRNA in epithelial cells in the intestine. H19 lncRNA bound to p53 and miR (miR-34a and let-7) that inhibit cell proliferation (alters regeneration of the epithelium) | Intestinal tissues of UC patients and mice | Geng H, et al. (2018) [138] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | miR-19b | IECs | LPS significantly induces cell inflammatory injury, downregulated miR-19b expression and activates NF-κB and PI3K/AKT pathway | Caco2 cells | Qiao CX, et al. (2018) [120] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | lncRNA | Monocytes/macrophages | LPS promotes a downregulation of the lncRNA growth arrest-specific transcript 5 (GAS5), could mediate tissue damage by modulating the expression of matrix metalloproteinases | IBD patients (n = 25) | Lucafò M, et al. (2019) [139] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | miR-215 | Fibroblasts | LPS upregulates the expression of miR-215, increases oxidative stress in LPS-treated intestinal fibroblast by downregulating GDF11 (Growth differentiation factor 11) expression and activating the TLR4/NF-κB and JNK/p38 signaling pathways | CCD-18Co cells | Sun B, et al. (2020) [122] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | miR-506 and DNMT1 modification | IECs | LPS inhibits miR-506, leading to reduced expression of anion exchange protein 2 and inositol-1,4,5-trisphosphate-receptor but was accompanied by a substantial increase in DNMT1 and SPHK1 (sphingosine kinase 1) expression. The enhanced levels of kinase SPHK1 resulte in upregulation of bioactive sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) which led to further activation of S1P-dependent signaling pathways. The net effect of these responses is severe inflammation | Patients with PSC, PSC with concurrent UC (PSC + UC), UC alone, and healthy controls (n = 10 each); Caco2 cells | Kempinska-Podhorodecka A, et al. (2021) [140] |

| LPS | Proinflammatory activity | miR-497 | Macrophages | Reduces miR-497, promotes the activation of NF-κB pathway and the release of cytokines | IBD patients, mice with colitis and LPS-treated RAW264.7 cells | Zhang M, et al. (2021) [121] |

Some germs may also contribute to the occurrence of IBD through their epigenetic mechanisms. Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), commonly associated with CD [114], upregulates the levels of miR-30c and miR-130a in intestinal epithelial cells (IECs), which reduces the levels of ATG5 and ATG16L1 and inhibits autophagy, leading to increased numbers of intracellular AIEC and the inflammatory response [115]. In turn, AIEC-infected IECs secrete exosomes that can transfer these same miR to recipient IECs with the same consequences, promoting the invasion and proliferation of infected tissues [116]. In addition, AIEC triggers an excessive mucosal immune response against the gut microbiota via the let-7b/TLR4 miR signaling pathway [117]. Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP), also known to be associated with IBD [118], induces miR-21 expression in infected macrophages and decreases their ability to eliminate the bacteria, thus contributing to intestinal inflammation [119].

Microbial components such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and flagellin may also induce host epigenetic changes. LPS (a major component of the Gram-negative bacteria outer membrane) contributes to the development of intestinal inflammation by promoting the activation of NF-κB (nuclear factor-kappa B) pathways and the cytokines released by the downregulation of miR-19b, miR-497 and miR-215 in IECs [120], monocyte/macrophage cells [121] and fibroblast cells [122], respectively. LPS can also increase the level of H19 lncRNA in IECs that bind to miR (miR-34a and let-7), inhibiting cell proliferation and, thus, impairing the intestinal epithelial barrier [20]. In contrast, the flagellins of some bacteria—in particular, Roseburia intestinalis (found in a reduced abundance in IBD patients)—have rather epigenetically mediated anti-inflammatory actions [123,124]. Flagellin inhibits the activation of the NLRP3 (NOD-like receptor family, pyrin domain containing 3) inflammasome and proptosis in macrophages via miR-223-3p [123] and induces a lncRNA (HIF1A-AS2) that inactivates the NF-κB/Jnk (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) pathway [124].

Although the taxonomic composition of the microbiota is stable at year 3, its composition can be influenced by a range of other environmental factors (including dietary habits, smoking and drugs, as discussed below), which may be responsible for the third step towards the occurrence of IBD [64].

4.3. Gut Microbiota-Derived Metabolites

Influenced by both the microbiota and diet, SCFAs are gut microbiota-derived metabolites that result from the anaerobic fermentation of nondigestible dietary fibers (found in fruits and vegetables). Acetate, butyrate and propionate, the three principal SCFAs, exert an anti-inflammatory role and promote the integrity of the epithelial barrier functions partly via the epigenetic pathways (Table 2) [141,142]. Among the SCFAs, butyrate is the most studied one. By inhibiting, in a reversible way, HDACs [143,144], cells exposed to butyrate present higher acetylation at specific lysine residues in histones, resulting in increased transcription of genes in both intestinal epithelial and immune cells [145]. The inhibition of HDAC in cells contributes to the reduction of inflammation by (1) the induction of IκBα expression, with a subsequent inhibition of the NF-κB pathway, (2) the inhibition of the IFN-γ/STAT1 (signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling pathway and (3) the activation of the anti-inflammatory function of PPARγ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ) [145]. Butyrate also has more specific epigenetic actions on certain cell types. At the epithelial level, butyrate plays a role in the integrity of the epithelial barrier (by restoring tight junction proteins [146]) and the defense against the invading microorganisms (via a nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2)-dependent pathway or via autophagy [147]). Butyrate also has an effect on various immune cells, such as (1) monocytes/macrophages (in which it induces monocyte-to-macrophage differentiation, promotes their antimicrobial activity through inhibition of HDAC3 [148], reduces the production of their inflammatory mediators [149] and induces the polarization of M2 macrophages [150]); (2) T cells (promotes Treg [151] and inhibits Th17 cell development [151]); (3) neutrophils (in which HDAC inhibition leads to proinflammatory cytokine reduction [152]) and (4) dendritic cells (inhibit IL-12 [153]). The epigenetic role of propionate and acetate has been less studied. Propionate promotes epithelial cell migration and contributes to intestinal epithelial restitution, a complex process important for tissue regeneration in IBD [142].

Table 2.

Impact of the gut microbiota-derived metabolites on the epigenome in intestinal inflammation. CD, Crohn’s disease; CEBPB, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; HDAC, histone deacetylases; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IECs, intestinal epithelial cells; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; lncRNAs, long non-coding RNAs; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MCP-1, Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1; miR, micro-RNA; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NOD2, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis.

| Metabolite | Activity | Epigenetic Mechanism | Tissue/Cells | Mechanism | Model | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCFAs | ||||||

| SCFAs | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDACs inhibition | T cells | Inhibits HDACs in T cells and increases the acetylation of p70 S6 kinase and phosphorylation rS6, regulating the mTOR pathway required for generation of Th17 (T helper type 17), Th1, and IL-10(+) T cells | C57BL/6 mice; CD4+ T cells isolated from the spleen and lymph nodes | Park J, et al. (2015) [154] |

| SCFAs | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDACs inhibition | B cells | Upregulates regulatory B cells capable of producing IL-10 in a manner dependent on their HDAC inhibitory activity | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Zou F, et al. (2021) [155] |

| SCFAs | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-145 | IECs | Decreases the CEBPB expression, which could bind to the miR-145 promoter to inhibit its expression, thereby promoting the expression of DUSP6 (dual-specificity phosphatase 6) and thus prevents the development of intestinal inflammation | LPS-treated intestinal epithelial cells | Liu Q, et al. (2022) [156] |

| Butyrate | ||||||

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone acetylation | IECs | Butyrate, by inducing an increase in histone acetylation in the NOD2 promoter region, induces NOD2 upregulation, and impact the defence mechanism against the bacterial membrane component peptidoglycan by inducing IL-8 and GRO-alpha secretion | Caco-2 cell line | Leung CH, et al. (2009) [147] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | Dendritic cells | Butyrate has a role of HDACi on the epigenetic modification of gene expression, inhibits IL-12 and upregulates subunit IL-23p19 | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Berndt BE, et al. (2012) [153] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC1 inhibition | T cells | Butyrate inhibits HDAC1 activity to induce Fas promoter hyperacetylation and Fas upregulation in T cells and promote Fas-mediated apoptosis of T cells to eliminate the source of inflammation | BALB/c mice | Zimmerman MA, et al. (2012) [157] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | IECs | Butyrate may contribute to the restoration of the tight junction barrier in IBD by affecting the expression of claudin-2, occludin, cingulin, and zonula occludens proteins (ZO-1, ZO-2) via inhibition of histone deacetylase | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Plöger S, et al. (2012) [146] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone H3 acetylation | T cells | Butyrate enhances histone H3 acetylation in the promoter and conserves non-coding sequence regions of the Foxp3 locus, regulating the differentiation of Treg cells, ameliorating colitis | Germ-free and CRB-associated mice; OT-II (Ly5.2) transgenic CD4+ T cells | Furusawa Y, et al. (2013) [144] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | Macrophages | Butyrate reduces de production of proinflammatory mediators by macrophages including nitric oxide, IL-6, and IL-12, but did not affect levels of TNF-α or MCP-1 | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Chang PV, et al. (2014) [149] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | H3K9 acetylation | Macrophages | Butyrate activates STAT6-mediated transcription through H3K9 acetylation driving M2 macrophage polarization | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Ji J, et al. (2016) [150] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone H3 acetylation | Macrophages | Oral supplementation with butyrate attenuates experimental murine colitis by blocking NF-κB signaling and reverses histone acetylation | DSS-induced colitis in mice, IL-10−/− mice and RAW264.7 cells | Lee C, et al. (2017) [158] |

| Butyrate | Anti or proinflammatory activity depending on its concentration and immunological milieu | HDACs inhibition | T cells | Lower butyrate concentrations facilitates differentiation of Tregs in vitro and in vivo under steady-state conditions. In contrast, higher concentrations of butyrate induces expression of the transcription factor T-bet in all investigated T cell subsets resulting in IFN-γ-producing Tregs or conventional T cells. This effect was mediated by the inhibition of histone deacetylase activity | DSS-induced colitis in mice; CD4+ T cells | Kespohl M, et al. (2017) [159] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC3 inhibition | MonocyteMacrophage | Butyrate induces the monocyte to macrophage differentiation and promotes its antimicrobial activity and restricts bacterial translocation, through HDAC3 inhibition | Human monocytes isolated from leukocyte cones of healthy blood donors | Schulthess J, et al. (2019) [148] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | T cells | Butyrate promotes Th1 cell development by promoting IFN-γ and T-bet expression and inhibits Th17 cell development by suppressing IL-17, Rorα, and Rorγt expression and upregulate IL-10 production in Th1 and Th17 | CBir1 transgenic T cells; Rag1−/− mice | Chen L, et al. (2019) [151] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | Increase of histone acetylation | IECs | Butyrate induces HSF2 (Heat-shock transcription factor 2) expression epigenetically via increasing histone acetylation levels at the promoter region, enhancing autophagy in IECs | UC (n = 50) and healthy (n = 30) patients; DSS-induced colitis in mice; HT-29 cells | Zhang F, et al. (2020) [160] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | IECs | Butyrate induces SYNPO (Synaptopodin) in epithelial cell lines through mechanisms possibly involving histone deacetylase inhibition. SYNPO contributes by intestinal homeostasis by controlling intestinal permeability | Epithelial cell lines; DSS-induced colitis in mice | Wang RX, et al. (2020) [161] |

| Butyrate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | Neutrophils | Butyrate significantly inhibits IBD neutrophils to produce proinflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and calprotectins through HDAC inhibition | Peripheral neutrophils isolated from IBD patients and healthy donors; DSS-induced colitis in mice | Li G, et al. (2021) [152] |

| Propionate | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC1 inhibition | IECs | Propionate promotes intestinal epithelial cell migration by enhancing cell spreading and polarization, a function dependant of the inhibition of class I HDAC | Mouse small intestinal epithelial cells (MSIE) and human Caco-2 cells; DSS-induced colitis in mice | Bilotta AJ, et al. (2021) [142] |

| Caprylic acid (C8) and nonanoic acid (C9) (medium chain fatty acids) | Anti-inflammatory activity | Acetylation of histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) | IECs | Reduces bacterial translocation, enhances antibacterial activity, and attenuates the activity of the classical histone deacetylase pathway to facilitate the acetylation of histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) at the promoters pBD-1 and pBD-2, remarkably increases the secretion of porcine β-defensins 1 (pBD-1) and pBD-2 | Porcine jejunal epithelial cell line-J2 | Wang J, et al. (2018) [162] |

4.4. Diet

Next, compared to a low-fiber diet [163], impacting the level of these SCFAs [163], other diets have been shown to induce epigenetic changes related to IBD (Table 3). Regarding the literature, elements of the Western diet, characterized by a low-fiber, low-fruit, low-vegetable and deficiency in micronutrients, as well a high-fat diet, may be associated with epigenetic changes in IBD. The Western diet has been shown to lead to a decrease in miR-143/145a, miR-148a and miR-152 in colonocytes with a consequent increase in ADAM17 (a disintegrin and metalloprotease 17) expression protein and colitis aggravation [164]. A low or deficient methyl diet can also contribute to intestinal inflammation by reducing SIRT1 (sirtuin 1) expression (a histone deacetylase), contributing to endoplasmic reticulum stress [165] and demethylating HIF-1-responsive elements (HRE), which leads to the abnormal gut expression of CEACAM6 (CEA Cell Adhesion Molecule 6), favoring AIEC colonization and subsequent inflammation [166]. Finally, it was shown that a high-fat diet can change the miR profile of the visceral adipose exosomes (switching the exosomes from an anti-inflammatory to a proinflammatory phenotype with an increase of miR-155, for example), predisposing the intestine to inflammation via promoting macrophage M1 polarization [167].

Table 3.

Impact of the diet on the epigenome in intestinal inflammation. ADAM17, a disintegrin and metalloprotease-17; AIEC, Adherent-invasive Escherichia coli; CD, Crohn’s disease; CEACAM6, carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6; CREB, C-AMP response element-binding protein; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; HDAC, histone deacetylase; HMGB1, high mobility group box 1; HRE, HIF-1-responsive elements; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; ICAM, intercellular adhesion molecule; IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; miR, microRNA; MMP9, Matrix Metallopeptidase 9; PBMC, peripheral blood mononuclear cell; PTEN, phosphatase and tensin homolog; NF-κB, nuclear factor-kappa B; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 3; PECAM, Platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule; RECK, reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TGF, transforming growth factor; TNBS, 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis; VCAM, vascular cell adhesion molecule 1; WT, wild-type; ZO, zonula occludens.

| Food | Activity | Epigenetic Mechanism | Tissue/Cells | Mechanism | Model | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diet | ||||||

| Western diet | Proinflammatory activity | miR-143, miR-145A, miR-148a, miR-152 | IECs | Leads to a decrease in miR-143/145a, miR-148a and miR-152 in colonocytes with a consequent increase in ADAM17 expression protein (these miRs regulating ADAM17) and aggravates colitis. | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Dougherty U, et al. (2021) [164] |

| High fat diet | Proinflammatory activity | miR-155 | Visceral adipocytes | High fat diet changes the miR profile (among which miR-155) of the visceral adipose exosomes, switching the exosomes from anti-inflammatory to a proinflammatory phenotype. | Macrophages | Wei M, et al. (2020) [193] |

| High fat diet rich in n-6 linoleic acid | Proinflammatory activity | DNA methylation | Colonic mucosae | Epigenetically modifies farnesoid-X-receptor (FXR), leading to the activation of downstream factors that participate in bile acid homeostasis and epigenetically activates prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase-2 (Ptsg-2) coupled accumulation of c-JUN and proliferative cyclin D1(Ccnd1) and increase the risk of inflammation | C57BL/6J mice; Human colonic foetal cells | Romagnolo DF, et al. (2019) [194] |

| Methyl-deficient diet | Proinflammatory activity | Sirtuin 1 | IECs | Reduces sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) expression level and promotes greater acetylation of (heat shock factor protein 1) HSF1, in relation with a dramatic decrease of chaperones (binding immunoglobulin protein (BIP), heat shock protein (HSP)27 and HSP90) | DSS-induced colitis in mice; Caco-2 cells | Melhem H, et al. (2016) [165] |

| Low-methyl diet | Proinflammatory activity | DNA methylation | IECs | Low-methyl diet-dependent HRE demethylation led to abnormal gut expression of CEACAM6 (carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell adhesion molecule 6), favouring AIEC colonisation and subsequent inflammation | Transgenic mice; Caco-2, T-84 and sh-HIF1-α-T-84 cells | Denizot J, et al. (2015) [166] |

| Methyl-donnor supplemented diet (folate, B12 vitamin) | Anti-inflammatory activity | DNA methylation | IECs | Methyl-donor supplemented diet contributes to hypermethylation of CEACAM6 promoter in IECs, associated with a significant decrease in CEACAM6 expression contributing to less adherence of AIEC bacteria to the enterocytes | CEABAC10 mice | Gimier E, et al. (2020) [195] |

| Isolated food | ||||||

| Cow’s milk (commercial) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-21, miR-29b and miR-125b | Colonic mucosae | Extracellular vesicles (EVs) concentrated from commercial cow’s milk downregulates miR-21, miR-29b and miR-125b. MiR-125b was associated with a higher expression of the NF-κB inhibitor TNFAIP3 (A20) | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Benmoussa A, et al. (2019) [178] |

| Human milk derived exosomes | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-320, miR-375, and Let-7 and DNMT1 and DNMT3 | Colonic mucosae | MiR highly express in milk, such as miR-320, 375, and Let-7, were found to be more abundant in the colon of milk derived exosomes-treated mice compared with untreated mice. These miR downregulate their target genes, mainly DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) and DNMT3 | DSS-induced colitis in mice; PBMC | Reif S, et al. (2020) [179] |

| Dietary depletion of milk exosomes and their microRNA cargos | Proinflammatory activity | miR-200a-3p | Cecum mucosae | Elicits a depletion of miR-200a-3p and elevated intestinal inflammation and chemokine (C-X-C Motif) ligand 9 expression | Mdr1a−/− mice | Wu D, et al. (2019) [180] |

| Saccharin sodium, Stevioside, and Sucralose (three common sweeteners) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-15b | IECs | Upregulate the expression of E-cadherin through the miR-15b/RECK/MMP-9 axis to improve intestinal barrier integrity. Saccharin exerts the most pronounced effect, followed by Stevioside and Sucralose | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Zhang X, et al. (2022) [181] |

| Galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-19 | IECs | GOS increases of cell viability, the decrease of apoptosis, as well as the suppressed release of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-1β by upregulating miR-19b | Human colon epithelial FHC cells; Helicobacter hepaticus induced colitis in rats | Sun J, et al. (2019) [182] |

| Cinnamaldehyde (a major active compound from cinnamon) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-21 and miR-155 | Macrophages | Cinnamaldehyde inhibits NLRP3 inflammasome activation as well as miR-21 and miR-155 level in colon tissues and macrophage. The decrease in miR-21 and miR-155 suppresses levels of IL-1β and IL-6; | DSS-induced colitis in mice; macrophage cell line RAW264.7 and human monocytes U937 | Qu S, et al. (2018) [185] |

| Cinnamaldehyde | Anti-inflammatory activity | lncRNAs H19 | T cells | Cinnamaldehyde inhibits Th17 cell differentiation by regulating the expression of lncRNA H19 | DSS-induced colitis in mice and naïve CD4+ T cells | Qu SL, et al. (2021) [101] |

| Limonin (a triterpenoid extracted from citrus) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-124 | IECs | Downregulates p-STAT3/miR-214 signaling pathway and represses the productions of proinflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α and IL-6) | DSS-induced colitis in mice; cultured normal colonic epithelial cells | Liu S, et al. (2019) [186] |

| Edible ginger | Anti-inflammatory activity | Contained around 125 miRNAs | IECs | Increases the survival and proliferation of IECs, reduces the proinflammatory cytokines (such as TNF-α, IL-6 and IL-1β), and increases the anti-inflammatory cytokines (including IL-10 and IL-22) in colitis | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Zhang M, et al. (2016) [187] |

| Ginsenoside Rh2 (active ingredient of ginseng) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-124 | IECs | Inhibits IL-6-induced STAT3 phosphorylation and miR-214 expression (which is an inflammatory effector molecule acting through NF-κB-IL6 pathway) | DSS-induced colitis in mice; cultured normal colonic epithelial cells | Chen X, et al. (2021) [188] |

| Black raspberries (BRBs) | Anti-inflammatory activity | Demethylation the promoter of dkk3; correction of promoter hypermethylation of suppressor genes | Colonic mucosae | BRBs exert their anti-inflammatory effects is through decreasing NF-κB p65 expression leading to decrease of DNMT3B expression (but also histone deacetylases 1 and 2 (HDAC1 and HDAC2) and methyl-binding domain 2 or MBD2), which in turn reverse aberrant DNA methylation of tumor suppressor genes, e.g., dkk2, dkk3, in the Wnt pathway, resulting in their enhanced mRNA expression locally in colon and systematically in spleen and bone marrow and thus in decreased translocation of β-catenin to the nucleus prohibiting the activation of the pathway | DSS-induced colitis in mice; splenocytes and bone marrow cells | Wang LS, et al. (2013) [189] |

| Black raspberries | Anti-inflammatory activity | Demethylation | Colonic mucosae | BRBs decreas the methylation of wif1, sox17, and qki gene promoters and thus increase their mRNA expression (contributing to Wnt signaling) | Interleukin-10 knockout mice | Wang LS, et al. (2013) [190] |

| Mastiha | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | T cells | Plays a role in circulating levels of miR-155, a critical player in T helper-17 (Th17) differentiation and function | UC patients (n = 35) | Amerikanou C, et al. (2021) [196] |

| Isoliquiritigenin | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDACs inhibition | IECs | Suppresses acetylated HMGB1 release via the induction of HDAC activity, which is one of the critical mediators of inflammation, which is actively secreted from inflammatory cytokine-stimulated immune or non-immune cells | HT-29 cells | Chi JH, et al. (2017) [197] |

| Chronic ethanol exposure | Proinflammatory activity | miR-122a | IECs | Increases the intestinal miR-122a expression, which decreased occludin (OCLN) expression leading to increased intestinal permeability | HT-29 cells | Chen Y, et al. (2013) [191] |

| Chronic alcohol feeding (but not acute alcohol binge) | Proinflammatory activity | miR-155 | Intestinal tissue | Increases miR-155 in the small bowel, which is a modulator of cytokine and T-cell immune response in the gut, leading to intestinal TNFα, and NF-κB activation | WT-mice | Lippai D, et al. (2014) [192] |

| Polyphenol | ||||||

| Polyphenolic red wine extract | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-126 | Fibroblasts | Polyphenolic red wine extract downregulates miR-126, leading to downregulation of NF-kB, ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and PECAM-1 | CCD-18Co myofibroblasts cells | Angel-Morales G, et al. (2012) [198] |

| Polyphenolic extracts from cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-126 | Fibroblasts | Cowpea may exert their anti-inflammatory activities at least in part through induction of miR-126 that then downregulate VCAM-1 mRNA and protein expressions | CCD-18Co myofibroblasts cells | Ojwang LO, et al. (2015) [199] |

| Mango (Mangifera indica L.) polyphenolics | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-126 | Fibroblasts | Mango polyphenols attenuates inflammatory response by modulating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway at least in part through upregulation of miR-126 expression | CCD-18Co cells; DSS-induced colitis in rats | Kim H, et al. (2017) [200] |

| Baicalin (flavone) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-191a | IECs | Exerts a protective effect on IECs against TNF-α-induced injury, which is at least partly via inhibiting the expression of miR-191a, thus increasing ZO-1 expression | IEC-6 cells | Wang L, et al. (2017) [170] |

| Pomegranate (Punica granatum L.) polyphenolics | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-145 | Myofibroblasts | Pomegranate polyphenols attenuate colitis by modulating the miR-145/p70S6K/HIF1α axis | DSS-induced colitis in rats; CCD-18Co colon-myofibroblastic cells | Kim H, et al. (2017) [201] |

| Alpinetin, a flavonoid compound extracted from the seeds of Alpinia katsumadai Hayata | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-302 | T cells | Activates Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), promoting expression of miR-302, downregulating expression of DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT-1), reducing methylation level of Foxp3 promoter region, facilitating combination of CREB and promoter region of Foxp3, and upregulating the expression of Foxp3. Alpinetin ameliorates colitis in mice by recovering Th17/Treg balance. | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Lv Q, et al. (2018) [168] |

| Fortunellin, a citrus flavonoid | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-374a | IECs | Fortunellin targets miR-374a, which is a negative regulator of PTEN, known to induce cell apoptosis | TNBS-induced colitis in rats | Xiong Y, et al. (2018) [169] |

| Quercetin (flavonoid) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-369-3p | DCs | Quercetin-induced miR-369-3p which reduce C/EBP-β, TNF-α, and IL-6 production | LPS-stimulated DCs | Galleggiante V, et al. (2019) [171] |

| Resveratrol (a natural plant product) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-31, Let7a, miR-132 | T cells | Resveratrol decreases the expression of several miRs (miR-31, Let7a, miR-132) that targets cytokines and transcription factors involved in anti-inflammatory T cell responses (Foxp3 and TGF-β). MiR-31 regulates the expression of Foxp3 with increase of CD4+ Foxp3+ regulatory T cells (Tregs) | TNBS-induced colitis in mice | Alrafas HR, et al. (2020) [176] |

| Resveratrol (an anti-oxidant) | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDACs inhibition | T cells | Inhibits HDACs, increases anti-inflammatory CD4+ FOXP3+ (Tregs) and CD4+ IL10+ cells, and decreases proinflammatory Th1 and Th17 cells | AOM and DSS-induced colitis in mice | Alrafas HR, et al. (2020) [175] |

| Chlorogenic acid (found in the coffee) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | Macrophages | Downregulates miR-155 expression, inactivates the NF-κB/NLRP3 inflammasome pathway in macrophages and prevent colitis | DSS-induced colitis in mice; LPS/ATP-induced RAW264.7 cells | Zeng J, et al. (2020) [177] |

| Lonicerin (constituant of herb Lonicera japonica Thunb.) | Anti-inflammatory activity | H3K27me3 modification | Macrophages | Binds to enhancer of zeste homolog 2 (EZH2) histone methyltransferase, which mediate modification of H3K27me3 and promotes the expression of autophagy-related protein 5, which in turn leads to enhanced autophagy and accelerates autolysosome-mediated NLRP3 degradation | DSS-induced colitis in mice and isolated colonic macrophages and IECs; bone marrow-derived macrophages | Lv Q, et al. (2021) [174] |

| Pristimerin (Pris), which is a natural triterpenoid compound extracted from the Celastraceae plant | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | Colonic mucosae | Pris may reduce DSS-induced colitis in mice by inhibiting the expression of miR-155 | Blood and colon tissue of IBD patients; DSS-induced colitis in mice | Tian M, et al. (2021) [202] |

| Cardamonin is a naturally occurring chalcone (majorly from the Zingiberaceae family incluging a wide range of spices from India) | Anti-inflammatory activity | Modulation of miR expression | Macrophages | Cardamonin modulates miR expression, protects the mice from DSS-induced colitis, decreases the expression of iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-6, and inhibited NF-kB signaling which emphasizes the role of cardamonin as an anti-inflammatory molecule | RAW 264.7 Cells (monocyte/macrophage-like cells); DSS-induced colitis in mice | James S, et al. (2021) [172] |

| Berberine | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-103a-3p | IECs | Represses Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation via modulating the miR-103a-3p/Bromodomain-containing protein 4 axis, thereby refraining pyroptosis and reducing the intestinal mucosal barrier defect induced via colitis | DSS-induced colitis in mice; Caco-2 cells and human NCM460 cells | Zhao X, et al. (2022) [173] |

Polyphenols, found mainly in fruits and vegetables, are complex molecules produced by plants with antioxidant properties able to scavenge free radicals. Divided into flavonoids (such as alpinetin, fortunellin, baicalin, quercetin, berberine, cardamonin and lonicerin) [168,169,170,171,172,173,174] and non-flavonoids (such as resveratrol [175,176] and chlorogenic acid [177]), they reduce the risk of intestinal inflammation, mainly by modifying the miRs profile and inhibiting HDACs. Other foods have also been shown to influence host epigenetics and could potentially play a role in gut inflammation. Milk [178,179,180], common sweeteners [181], galacto-oligosaccharides [182], corn cobs [183], cinnamaldehyde (a major active compound from cinnamon) [184,185], limonin (a triterpenoid extracted from citrus) [186], ginger [187], ginseng [188] and black raspberries [189,190] have anti-inflammatory properties. In contrast, chronic alcohol exposure increases miR-122a and miR-155 expression in the intestine, which decreases occludins expression, leading to increased intestinal permeability and modulates cytokines and the T-cell immune response in the gut, leading to intestinal TNFα (tumor necrosis factor α) and NF-κB activation, respectively [191,192].

4.5. Smoking

Smoking habits are the single best-established environmental factor that influences the CD phenotype, behavior and response to therapy [203]. While nicotine is the most prominent component released during smoking (and therefore the best-studied), other chemical components could also induce epigenetic changes, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons; heavy metals (nickel, cadmium, chromium and arsenic); carbon monoxide and reactive oxygen species [203]. Well-studied in lung diseases (but never in IBD, to our knowledge), smoking-induced epigenetic modifications seem to be strongly associated with smoking habits, the dose and the duration of smoke exposure [204,205,206,207,208,209]. The methylation of certain genetic loci, post-translational modifications of histones and the level of expressed miR may be reversible after smoking cessation (after 5 years, according to some studies) [93,204,205,206,207,208,209,210]. In contrast to these reversible epigenetic changes, others remain unchanged even after 30 years of smoking cessation, explaining that epigenetic modifications induced by smoking exposition confer long-term risks of adverse health outcomes but could also be transmitted to the next generation [93,204,207,208,209,210,211]. The mechanisms by which tobacco may contribute to inflammation are multiple and involve changes in the enzymes involved in DNA methylation, post-transcriptional histone modifications and ncRNAs [65,93,203,212,213,214].

Regarding smoking-induced DNA methylation, a meta-analysis performed by Joehanes and colleagues highlighted various genome-wide association studies showing that smoking-induced genes differentially methylated are enriched for variants associated with smoking-related diseases, including IBD, CD and UC [210,215,216]. The findings suggest that changes in methylation of the BCL3, FKBP5, AHRR and GPR15 genes are involved in the mechanism by which smoking increases the risk of CD [217,218].

Concerning smoking-induced histone modifications, smoking also contributes to histone hyperacetylation (H4 histone in active smoking and H3 histones in ex-smokers) by upregulating HATs and downregulating SIRT 1–7 (which belong to the family of class III HDACs) [65,219,220,221,222,223,224,225,226,227]. This imbalance, in favor of histones acetylation, contributes to the increased transcription of proinflammatory genes, mainly controlled by NF-κβ [65,219,221,224,228,229,230,231,232], and the increase of expression of proinflammatory mediators (including IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6), contributing to chronic inflammation [228,229,233,234]. In a colitis model, Lo and colleagues showed that the reduction of SIRT2 could also be associated with a reduction of the M2-associated anti-inflammatory pathway [229]. The SIRT3 reduction is associated with less activation of the NALP3 inflammasome [235]. Cigarette smoke exposure upregulates the enzyme that catabolizes HMTs, leading to an increase of the H3 and H4 histone residue methylation [226], which may contribute to the proinflammatory cascade [236].

Smoking exposure also alters ncRNAs in a dose-and-time-dependent manner, high doses of and long-lasting exposure being necessary to induce irreversible ncRNA alterations, which may be involved in smoking-related diseases [237,238]. While there are no data on lncRNAs, the impact of smoking on miRs in IBD has been better studied. Interestingly, these IBD-induced epigenetic changes could partly explain why smoking is rather protective in UC, whereas it is an important risk factor in CD. Indeed, nicotine enhances the miR-124 expression, which targets and downregulates IL6R, resulting in a shifting Th1/Th2 balance toward Th1 (in peripheral blood lymphocytes and colon tissues), thereby protecting against Th2-type UC and worsening Th1-type CD [239]. This increase in miR-124 in epithelial cells, lymphocytes and macrophages in response to nicotine also results in the phosphorylation of STAT3, in a decreased production of IL-6 at the transcriptional level, and prevents the conversion of pro-TNF-α to TNF-α, which also explains the protective role of tobacco in the UC [240,241]. Tobacco also induces changes in several miRs that are functionally related to inflammation [65]. Among those highlighted in the IBDs are miR-21, miR-132, miR-195 and miR-223 [65]. MiR-21 (increased in the colon of IBD patients [242]) is known to increase the intestinal epithelial permeability (through an action on the tight junctions) [242,243,244] and plays a crucial role in T-cell differentiation, apoptosis and activation [242,245,246,247] and promotes the production of inflammatory cytokines (including TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-1β) by immune cells, contributing to tissue inflammation and IBD pathogenesis [248,249,250]. The overexpression of a miR-195 precursor lowered the cellular levels of the Smad7 protein, leading to a decrease in c-Jun and p65 expression, and might contribute to the protective effect of tobacco in UC [251]. Lastly, smoking also downregulates miR-200 [252], known to repress epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (or EMT), a process involved in intestinal fibrosis [242,252]. Consequently, the decrease of miR-200 in response to smoking could partly explain why smoking IBD patients are more likely to develop intestinal fibrosis (and fibrostenosis) [253,254,255].

4.6. Drugs

While the impact of NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and oral contraceptives [256,257], whose long-term consumption is known to be associated with IBD, on the epigenome of IBD patients has apparently not yet been investigated, other molecules have a known impact (Table 4). Several treatments used in IBD exert their anti-inflammatory action via epigenetic modifications, such as 5ASA [258,259], anti-TNF [125,127,260,261,262,263,264], exclusive enteral nutrition [265] and mesenchymal stem cells [266,267]. Antibiotics [268,269,270] and probiotics [271,272,273,274,275,276] can also reduce gut inflammation through various epigenetic mechanisms. Finally, a range of Chinese herbs have been shown to have an epigenetically mediated anti-inflammatory action in the gut [277,278,279,280,281,282,283,284,285,286,287].

Table 4.

Impact of drugs on epigenome in intestinal inflammation. 5-ASA, 5-aminosalicylic acid; CD, Crohn’s disease; circRNA, circular RNA; CpG, CpG, cytosine–phosphate–guanine; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; DNMT, DNA methyltransferase; DSS, dextran sulfate sodium; EEN, Exclusive enteral nutrition; EMT, epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition; EV, extracellular vesicle; HDAC, histone deacetylases; HPM, Herb-partitioned moxibustion; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IEC, intestinal epithelial cell; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; lncRNA, long non-coding RNA; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; miR, micro-RNA; MSC, mesenchymal stem cell; PPAR-γ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ; RNA, ribonucleic acid; SCFAs, short-chain fatty acids; SNIP1, Smad Nuclear Interacting Protein 1; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; TLR, toll-like receptor; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TNBS, 2,4,6-Trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid; UC, ulcerative colitis; VEGF, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor; ZO, zonula occludens.

| Drug | Activity | Epigenetic Mechanism | Tissue/Cells | Mechanism | Model | Author |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IBD medication | ||||||

| Mesalamine | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-206 | IECs and colonic tissues | Long-term treatment donw-regulates miR-206 which confer a protective effect in inducing and maintaining histologic remission | HT29 colon cells; UC patients (n = 10) | Minacapelli CD, et al. (2019) [258] |

| 5-ASA | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-125b, miR-150, miR-155, miR-346 and miR-506 | IECs | 5-ASA suppressed the levels of miR-125b, miR-150, miR-155, miR-346 and miR-506 in IECs and inhibition of these miR were associated with significant inductions of their target genes such as vitamin D receptor (VDR), suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS1), Forkhead box O (FOXO3a) and DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) | Caco-2 cells | Adamowicz M, et al. (2021) [259] |

| Infliximab | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-10a | DCs | Anti-TNF mAb treatment significantly promote miR-10a expression, whereas it markedly inhibited NOD2 and IL-12/IL-23p40 in the inflamed mucosa | Human monocyte-derived dendritic cells (DC); IBD patients | Wu W, et al. (2015) [127] |

| Infliximab | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-301a | T cells | Decreases miR-301a expression in IBD CD4+ T cells by decreasing Th17 cell differentiation through upregulation of SNIP1 | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC); inflamed mucosa of patients with IBD | He C, et al. (2016) [260] |

| Infliximab | Anti-inflammatory activity | lnc-ITSN1-2 | T cells | Lnc-ITSN1-2 promotes IBD CD4+ T cell activation, proliferation, and Th1/Th17 cell differentiation by serving as a competing endogenous RNA for IL-23R via sponging miR-125a | Intestinal mucosa from IBD patients (n = 6) and healthy controls (n = 6) | Nie J, et al. (2020) [261] |

| Infliximab | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-30 family | IECs | Decreases circRNA_103765 expression, which act as a molecular sponge to adsorb the miR-30 family and impair the negative regulation of Delta-like ligand 4 (DLL4) and protect human IECs from TNF-α-induced apoptosis | IBD patients; PBMCs | Ye Y, et al. (2021) [262] |

| Infliximab | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-146a and miR-146b | Serum and intestinal mucosae | Decreases miR-146a and miR-146b levels in serum. miR-146a probably promotes colitis through TLR4/MyD88/NF-κB signaling pathway | Serum of 19 IBD patients | Batra SK, et al. (2020) [263] |

| Infliximab (IFX) therapy and longer-term steroids (weeks) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-320a | Decreases miR-320a serum level. miR-320a could play a role in sensitization of the quiescent mucosa to environmental factors | Serum of 19 IBD patients | ||

| Anti-TNF and glucocorticoids | Anti-inflammatory activity | let-7c | let-7c serum level decreases, thus reduces M2 macrophage polarization (anti-inflammatory) and promote M1 (proinflammatory) polarization | Serum of 19 IBD patients | ||

| Anti-TNF | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-10a | DCs | Blockade TNF with anti-TNF mAb markedly enhances miR10a expression in the intestinal mucosa. miR-10a could block intestinal inflammation and reduce the differentiation Th1 and Th17 | C57BL/6 (B6) mice | Xue X, et al. (2011) [125] |

| Anti-TNF | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-378a-3p, miR-378c | Colonic mucosae | Increases levels of miR-378a-3p and miR-378c. Over-expression of miR-378a-3p decreased the levels of an IL-33 target sequence β-gal-reporter gene | Active UC patients (n = 24); inactive UC (n = 10); controls (n = 6); HEK293 cells | Dubois-Camacho K, et al. (2019) [264] |

| Enemas containing short chain fatty acids (SCFA) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone acetylation | IECs | SCFAs increase histone acetylation states and inhibit the production of proinflammatory substances, such as IL-8, by the intestinal epithelium | Caco-2 cells | Huang N, et al. (1997) [288] |

| N-(1-carbamoyl-2-phenylethyl) butyramide (FBA), a butyrate-releasing derivative | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone deacetylase-9 and H3 histone acetylation | Colonic mucosae | FBA, similar to its parental compound sodium butyrate, inhibited histone deacetylase-9 and restored H3 histone acetylation, exerting an anti-inflammatory effect through NF-κB inhibition and the upregulation of PPARγ | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Simeoli R, et al. (2017) [289] |

| Exclusive enteral nutrition (EEN) | Anti-inflammatory activity | hsa-miR-192-5p, hsa-miR-423-3p, hsa-miR-99a-5p, hsa-miR-124-3p, hsa-miR-301a-5p, hsa-miR-495-5p, and hsa-let-7b-5p | Intestinal mucosae | EEN induces mucosal miRNAs expression profile (altered expressions of hsa-miR-192-5p, hsa-miR-423-3p, hsa-miR-99a-5p, hsa-miR-124-3p, hsa-miR-301a-5p, hsa-miR-495-5p, and hsa-let-7b-5p) after EEN therapy was significantly changed compared with inflamed mucosa before treatment | CD patients (n = 30) | Guo Z, et al. (2016) [265] |

| ABX464 | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-124 | Immune cells | Upregulates miR-124 in human immune cells, which is a negative regulator of inflammation and was shown to target RNAs, such as STAT and TLR | Tazi J, et al. (2021) [290] | |

| MSCs | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-181a | IECs | MSC-derived exosomal miR-181a could alleviate colitis by promoting intestinal barrier function decreased (increasing level of Claudin-1, ZO-1, and IκB) | DSS-induced colitis in mice and induced human colonic epithelial cell (HCOEPIC) | Gu L, et al. (2021) [266] |

| MSCs | Anti-inflammatory activity | H3K27me3 | T cells | Extracellular vesicles from MSCs could inhibit the differentiation of Th17 cells by regulating H3K27me3 | TNBS-induced colitis in mice | Chen Q, et al. (2020) [291] |

| IFN-γ pretreated bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-125a and miR-125b | T cells | Increases the level of miR-125a and miR-125b of exosomes, which directly targeted on Stat3, to repress Th17 cell differentiation | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Yang R, et al. (2020) [267] |

| Vascular endothelial growth factor-C-treated adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-132 | Lymphatic endothelial cells | VEGF-C-treated ADSCs have a higher level of miR-132, which promotes lymphangiogenic response by directly targeting Smad-7 and regulating TGF-β/Smad signaling | Lymphatic endothelial cells (LECs) | Wang X, et al. (2018) [292] |

| Supplementation | ||||||

| Iron | Proinflammatory activity | TET1 induction; NRF2, NQ01, GPX2 demethylation | IECs and intestinal mucosae | Chronic iron exposure leads to induction of TET1 expression leading to demethylation of NRF2 (nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2) pathway targets (including NAD(P)H Quinone Dehydrogenase 1 (NQO1) and Glutathione peroxidase 2 (GPX2). NQO1 and GPX2 hypomethylation led to increased gene and protein expression, and could be a route by which cells overcome persistent and chronic oxidative stress | Caco-2 cells and wild-type C57BL/6 mice | Horniblow RD, et al. (2022) [293] |

| Antibiotics | ||||||

| Isotretinoin | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR | T cells | 3 miR overexpressed in naive T-cells and potentially downregulate 777 miR targets (cytoskeleton remodelling and the c-Jun N terminal kinase (JNK) signaling pathway) | Balb/c mice | Becker E, et al. (2016) [268] |

| Metronidazole | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR | 5 miR were significantly lower in naive T-cells resulting in the prediction of 340 potentially upregulated miR targets associated with IL-2 activation and signaling, cytoskeleton remodelling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal-transition (EMT). | |||

| Doxycycline | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-144-3p | Overexpression of miR-144-3p that resulted in the prediction of 493 potentially downregulated miR targets involved in protein kinase A (PKA), protein kinase B and nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) signaling pathways | |||

| Tetracyclines | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-150, miR-155, miR-375 and miR-146 | Colonic tissues | Reduce miR-150 and miR-155 expression, upregulate miR-375 and miR-142 | DSS-induced colitis in mice and bone marrow-derived macrophages | Garrido-Mesa J, et al. (2018) [269] |

| Antibiotics treatment | Anti-inflammatory activity | DNA demethylation | IECs | Suppresses aberrant DNA methylation of three marker CpG islands (Cbln4, Fosb, and Msx1) induced by chronic inflammation | AOM/DSS-induced colitis in mice | Hattori N, et al. (2019) [270] |

| Probiotics | ||||||

| Probiotic bacterium Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-203, miR-483-3p, miR-595 | IECs | Increases miR-203, miR-483-3p, miR-595 targeting tight junction (TJ) proteins; these miRNAs are involved in the regulation of barrier function by modulating the expression of regulatory and structural components of tight junctional complexes. | T84 cells | Veltman K, et al. (2012) [271] |

| Bifidobacterium longum | Anti-inflammatory activity | DNA demethylation | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells | B. Longum treatment significantly demethylates several CpG sites in Foxp3 promoter | TNBS-induced colitis in rat; spleen peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) cells was extracted | Zhang M, et al. (2017) [272] |

| Lactobacillus fermentum and Lactobacillus salivarius | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155, miR-223, miR-150 and miR-143 | Colonic tissues | They increase the expression of miR-155 and miR-223, and miR-150 and miR-143 for L. fermentum, involved in the immune response (restoration of Treg cell population and the Th1/Th2 cytokine balance) and in the intestinal barrier function | C57BL/6J mice | Rodríguez-Nogales A, et al. (2017) [273] |

| Saccharomyces boulardii | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 and miR-223; miR-143 and miR-375 | Colonic tissuess | Increasing the expression of miR-155 and miR-223, whereas decreasing the expression miR-143 and miR-375 | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Rodríguez-Nogales A, et al. (2018) [274] |

| Bifidobacterium bifidum ATCC 29521 | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-150, miR-155, miR-223 | Colonic mucosae | Restorates miR-150, miR-155, miR-223, upregulates anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, PPARγ, IL-6), tight junction proteins (such as ZO-1, MUC-2, Claudin-3, and E Cadherin-1) and downregulates inflammatory genes (TNF-α, IL-1β) | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Din AU, et al. (2020) [275] |

| Lactobacillus casei LH23 probiotic | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone H3K9 acetylation | Colonic tissues | Modulates the immune response and ameliorates colitis via suppressing JNK/p-38 signal pathways and enhancing histone H3K9 acetylation | DSS-induced colitis in mice; LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells | Liu M, et al. (2020) [294] |

| Lactic Acid-Producing Probiotic Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Anti-inflammatory activity | Histone H3K9 acetylation and histone H3K18 lactylation | Macrophages | Promotes histone H3K9 acetylation and histone H3K18 lactylation and attenuates intestinal inflammation via suppressing macrophage pyroptosis | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Sun S, et al. (2021) [276] |

| Other medication | ||||||

| Telmisartan (angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker and a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-receptor-γ agonist) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | Mesenteric adipocytes | Restorates the mesenteric adipose tissue adipocyte morphology and the expression of adipokines by suppressing the neurotensin/miR-155 pathway | IL-10(−)/(−) mice; cultured mesenteric adipose tissue from Crohn’s disease patients | Li Y, et al. (2015) [295] |

| Melatonine | Anti-inflammatory activity | Prevent DNA methylation | IECs | Prevents DNA demethylation, reduces NF-κB activation, decreases the levels of inflammatory mediators (including IL-6, IL-8, COX-2, and NO), and reduces increase in paracellular permeability, attenuating the inflammatory response | Caco-2 cells | Mannino G, et al. (2019) [296] |

| Morphine | Proinflammatory activity | Let7c-5p | Macrophages, DCs | Opioid treatment can disrupt gut immune homeostasis by inhibiting packaging of miR into EVs secreted by intestinal crypt cells (with a decreased amount of Let7c-5p) | C57BL/6J mice; organoid culture | Zhang Y, et al. (2021) [297] |

| Artesunate | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | Macrophages | Inhibits the expression of miR-155 to inhibit the NF-κB pathway | LPS-induced RAW264.7 cells; BALB/c mice model | Yang ZB, et al. (2021) [298] |

| Valproic acid treatment | Anti-inflammatory activity | HDAC inhibition | Intestinal tissue | Inhibits HDAC activity and increases H3K27ac levels and reduced expression of IL6, IL10, IL1B, and IL23 | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Felice C, et al. (2021) [299] |

| Tetrandrine | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-429 | IECs | Tetrandrine can attenuate the intestinal epithelial barrier defects in colitis through promoting occludin expression via the AhR/miR-429 pathway | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Chu Y, et al. (2021) [300] |

| Chinese medicine | ||||||

| Sinomenine, a pure alkaloid isolated in Chinese medicine | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | Colonic tissues | Downregulates the levels of miR-155 and several related inflammatory cytokines | TNBS-induced colitis in mice | Yu Q, et al. (2013) [277] |

| Tripterygium wilfordii Hook F (TWHF) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-155 | Ileocolonic anastomosis | Triptolide could suppress miR-155/SHIP-1 signaling pathway and attenuated expression of inflammatory cytokines after ileocaecal resection | IL-10(−/−) mice | Wu R, et al. (2013) [278] |

| Herb-partitioned moxibustion (HPM) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-147 and miR-205 | Colonic tissues | Upregulates the expression of miR-147 and miR-205 and then further regulate some of their target genes, thereby indirectly inhibiting the inflammatory signal pathways mediated by TLR, NF-κB, and so forth and decreasing the production of downstream inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, so as to alleviate intestinal inflammation in CD | Experimental CD rat models | Wei K, et al. (2015) [280] |

| Salvianolic acid B (Sal B) is isolated from the traditional Chinese medical herb Salvia miltiorrhiza | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-1 | IECs | Sal B restores barrier function by miR-1 activation and subsequent myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) inactivation | TNBS-induced rat colitis model | Xiong Y, et al. (2016) [281] |

| Herb-partitioned moxibustion (HPM) | Anti-inflammatory activity | miR-184 and miR-490-5p | Colonic tissue | HPM regulates miR-184 and miR-490-5p expression, act on the transcription of their target genes to regulate inflammatory signaling pathways, and attenuate inflammation and tissue injury in the colons of rats with DSS-induced UC | DSS-induced colitis in mice | Huang Y, et al. (2017) [282] |